Interleukin-6, Secreted by Human Ovarian Carcinoma Cells, Is a Potent Proangiogenic Cytokine (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2006 Aug 9.

Abstract

Angiogenesis, a key rate-limiting step in the growth and dissemination of malignant tumors, is regulated by the balance between positive and negative effectors. Recent studies indicate that the pleiotropic cytokine interleukin-6 (IL-6) may contribute to the vascularization of some tumors by disrupting the equilibrium between positive and negative angiogenic regulatory molecules. We determined whether IL-6 participates in the angiogenesis observed during the progression of ovarian carcinoma. We measured IL-6 production by human ovarian cancer cell lines in vitro and in vivo; not all cell lines secreted IL-6 in vitro, but when the cell lines were implanted into the peritoneal cavity of female nude mice, every line secreted IL-6. Most human ovarian carcinoma cell lines tested secreted significant levels of the soluble IL-6 receptor (sIL-6R). Endothelial cell lines established from the ovary and mesentery of female H-2K _b_-_ts_A58 mice were tested for response to IL-6. Both endothelial cell lines expressed the IL-6 receptor (IL-6R), and their stimulation with the exogenous ligand significantly enhanced cell migration and activated the downstream signaling molecule STAT3. Dual immunohistochemical staining for IL-6R and CD-31 revealed IL-6R expression on human endothelial cells within normal ovary and carcinoma specimens. Gelfoam sponges containing 0.4% agarose and IL-6 or bFGF and implanted into the subcutis of BALB/c mice were vascularized to the same extent. Collectively, the data indicate that ovarian tumor cells secreted IL-6, a highly angiogenic cytokine that supports progression of disease.

Keywords: Interleukin-6, endothelial cells, angiogenesis, ovarian cancer

INTRODUCTION

The progressive growth and dissemination of solid tumors is dependent on the process of angiogenesis (1, 2), which is regulated by the equilibrium between pro- and antiangiogenic molecules (3). An excess of proangiogenic regulators can lead to the activation of quiescent microvascular endothelial cells causing them to elaborate proteases, migrate towards the stimuli, undergo cell division, and form tube structures (4). The vascular structure these form brings nutrients and oxygen to the developing tumor. Understanding the cellular and molecular mechanisms that regulate angiogenesis in different organs is therefore essential for developing effective therapeutic interventions.

Interleukin-6 (IL-6) was originally identified as a B lymphocyte differentiation factor (5). It has since been recognized as critical mediator of physiologic processes such as hematopoiesis, platelet production, osteoclast activation, and production of acute-phase proteins (6). Several recent reports have implicated IL-6 as an important modulator of tumor progression (7, 8). The serum level of IL-6 is frequently elevated in women with ovarian carcinoma and is predictive of poor clinical outcome (9, 10); however, the exact role that IL-6 plays in this malignancy or whether IL-6 can regulate tumor angiogenesis has not been established. Previously, IL-6 has been shown to promote the release of vascular endothelial growth factor/vascular permeability factor (VEGF/VPF) from cervical cancer cells and glioblastoma cells (11). Transgenic mice engineered to overexpress IL-6 exhibit hypervascularization of the cerebellum (12), and IL-6 has been shown to stimulate the proliferation of cultured cerebral endothelial cells (13). Other studies support a role for IL-6 in the neovascularization that accompanies physiologic tissue remodeling. Mice deficient in IL-6 display reduced angiogenic responses in wound injury and have significantly prolonged wound healing times (14). Fluctuations in IL-6 gene expression have been correlated with the cyclic angiogenesis that occurs during maturation of the ovarian follicle (15).

These studies support the notion that IL-6 may be an important regulatory molecule in both physiologic and pathologic angiogenesis, but whether it plays a direct role in the process is still controversial. For example, some have suggested that endothelial cells do not express receptors for IL-6 (16), and others have reported that endothelial cell proliferation can be inhibited in response to IL-6 (17). Given the considerable functional and molecular heterogeneity that exists among endothelial cells from different anatomic regions (18, 19), the differences in results could be products of the variations in the organ microenvironment.

In the present report, we examined human ovarian tumors implanted orthotopically in the peritoneal cavity of female nude mice and found that ovarian carcinoma cells produce significant levels of IL-6 and express the sIL-6R. Moreover, the expression of the IL-6R was found on murine endothelial cells derived from the ovary and mesentery as well as on human blood vessels within clinical specimens of human ovarian carcinoma. We demonstrate that IL-6 elicited a significant angiogenic response from these microvascular endothelial cells. The identification of a novel IL-6 paracrine signaling network between ovarian tumor cells and microvascular endothelial cells may therefore have important implications for therapy directed against the vascular component of this neoplasm.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and Tumor Cell Lines

Female BALB/c and BALB/c athymic nude mice (Ncr-nu) were purchased from the National Cancer Institute-Frederick Cancer Research and Development Center (Frederick, MD). Female H-2K b _-ts_A58 mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). All mice were housed under pathogen-free conditions in facilities approved by the American Association of Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care and in accordance with current regulations and standards of the United States Department of Agriculture and National Institutes of Health. Mice utilized in this study were 8–10 weeks of age.

The human ovarian carcinoma cell line Hey-A8 was a gift from Dr. Gordon B. Mills (The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX). SKOV3.ip1 is a variant derived from SKOV3 cells (ATCC; Manassas, VA) that was established from the ascites fluid of nude mice following intraperitoneal injection of the parent line (20). OVCAR3 carcinoma cells were obtained from ATCC, and EG cells were obtained from Dr. Anil K. Sood (The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center). Cell lines were cultured as monolayers in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), vitamins, sodium pyruvate, L-glutamine, and nonessential amino acids (Life Technologies, Inc. Grand Island, NY).

Establishment of Ovarian, Mesenteric, and Dermal Microvascular Endothelial Cells

Tissue-specific endothelial cells were established as previously described (21). In brief, tissues (ovary, mesentery, and skin) were harvested from H-2K b _-ts_A58 female mice and subjected to mechanical and enzymatic (0.2% type IV collagenase; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) digestion. Tissue digests were resuspended in 10% FBS DMEM containing 10 units/ml of interferon-gamma (IFN-γ; Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), plated into T75 flasks, and incubated at 33°C in a mixture of 5% carbon dioxide and 95% oxygen. IFN-γ was added to augment the expression of the MHC H-2K b class I promoter, which regulates the level of large T-antigen protein in H-2K b _-ts_A58 mouse-derived cells (22). Cells were expanded and then prepared for flow cytometry by stimulating the primary cultures with 10 ng/ml of recombinant murine tumor necrosis factor-alpha (rmTNF-α; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) for 5 h and then labeling the endothelial cell fraction with 4 μg/ml of phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated rat anti-mouse E-selectin mAb and 2 μg/ml FITC-conjugated rat anti-mouse VCAM-1 mAb (both from Pharmingen, San Diego, CA). Cell staining was evaluated with a Beckman Epics Elite flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter, Miami, FL) equipped with an air-cooled argon ion laser. Dual positive cells were selected for expansion and then subjected to an additional sort, after which endothelial cell identity was confirmed by a rigorous characterization analysis as previously described (21). IFN-γ was removed from the supporting medium, and endothelial cells were expanded by growing in a 33°C incubator. Prior to analysis, endothelial cells were transferred to a 37°C environment for a period of at least 72 h, at which time the presence of the SV40 large T antigen is no longer detectable by Western analysis.

Tumor Cell Expression of IL-6 and sIL-6R

To evaluate the in vitro expression of IL-6 by human ovarian cancer cell lines, 2 × 105 cells were seeded into individual wells of a 6-well plate. Following a 24-h incubation, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and 1 ml of 10% FBS/DMEM was added to each well. After 48 h, tumor cell-conditioned medium was collected, centrifuged to pellet any detached cells, and tested for the presence of human IL-6 by ELISA (R&D Systems). To evaluate the expression of soluble IL-6R by human ovarian cancer cell lines, 1 × 105 cells were seeded into individual wells of a 24-well plate and incubated overnight. Cells were then washed with PBS, and 0.3 ml of 10% FBS/DMEM was added to each well. After 72 h, tumor cell-conditioned medium was collected, centrifuged to pellet any detached cells, and tested for the presence of the soluble IL-6R by ELISA (R&D Systems).

To evaluate tumor cell production of IL-6 in vivo, 1 × 106 Hey-A8 and 1 × 106 SKOV3.ip1 cells were injected into the peritoneal cavity of female nude mice. After 28 days, the mice were killed, and the tumors were harvested and then evaluated using immunohistochemical, ELISA, or Western analysis. Tumor sections intended for immunohistochemical evaluation were embedded in optimal cutting temperature medium (OCT; Miles Inc., Elkhart, IN), and 8-μm sections were mounted on positively charged slides (Fisher Scientific, Houston, TX). Sections were fixed by immersing slides in three acetone preparations for a period of 5 min each. Endogenous peroxidase was quenched by incubating sections in 0.3% hydrogen peroxide in PBS for 20 min followed by washing in PBS. Samples were blocked in 5% horse serum and 1% goat serum for 20 min at room temperature and incubated for 18 h at 4°C with a monoclonal antibody directed against human IL-6 (Biosource International, Inc., Camarillo, CA). Samples were washed in PBS and incubated with a peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (Jackson Research Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME); a positive reaction was visualized by incubating sections for 15 min with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine. Controls consisted of sections incubated with only secondary antibody. Sections were counterstained with Gill’s hemotoxylin and mounted using Universal Mount (Research Genetics, Huntsville, AL). Additional tumors, as well as normal mouse ovary and peritoneal tissue, were incubated in protein lysis buffer [20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 137 mM sodium chloride, 10% glycerol, 2 mM EDTA, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1% aprotinin, 20 μM leupeptin, and 0.15 units/ml aprotinin] on ice for 2 h with frequent agitation. Lysates were cleared by centrifugation, and protein content was quantified spectrophotometrically. Tumor protein (80 μg) resolved in 10% SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions was transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Membranes were blocked with 5% (wt/vol) nonfat dried milk in 0.1% Tween 20 (Sigma) in PBS for 1 h and then incubated overnight at 4°C with an anti-human IL-6 antibody (R&D Systems). Mouse anti-human IL-6 antibodies used did not cross-react with mouse IL-6 as confirmed by Western blot.

Immunodetection was performed using the corresponding secondary HRP-conjugated antibody, and HRP activity was detected using enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL; Amersham Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ). Some of the supernatants were also evaluated by ELISA (R&D Systems).

Detection of IL-6R on Endothelial Cells

Murine endothelial cells isolated from the ovary, mesentery, and skin were seeded into individual chambers of a two-chambered slide at a density of 1 × 105 cells per chamber and incubated for 48 h. Cells were fixed in acetone for 15 min, washed with PBS, and incubated in blocking solution for 20 min. The slides were incubated with a rabbit anti-mouse IL-6R antibody (Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA) overnight at 4ºC, rinsed 3 times with PBS, and then incubated with an Alexa 594 conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Control cells were incubated with only secondary antibodies. Immunofluorescence microscopy was performed using a Zeiss Axioplan fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss, Inc., Thornwood, NY), and images captured using an air-cooled charge-coupled device Hamamatsu C5810 camera (Hamamatsu Photonics K.K., Bridgewater, NJ) and Optimas software (Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD). The expression of IL-6R by murine microvascular endothelial cells was also evaluated by Western analysis as described above. Protein (50 μg) was separated by SDS-PAGE and blotted onto nitrocellulose. To detect IL-6R, membranes were incubated overnight at 4ºC with a 1:500 dilution of rabbit anti-mouse IL-6R antibodies (Santa Cruz) in blocking solution. BJAB cell lysates (Santa Cruz) served as a positive control. A 1:100 dilution of IL-6R blocking peptides (Santa Cruz) were used simultaneously with IL-6R antibodies to confirm the identity of the IL-6R band on the Western blot.

To evaluate expression of IL-6R on human endothelial cells, clinical specimens of ovarian carcinoma were embedded in OCT (Miles, Inc.), and 8-μm sections were mounted on positively charged slides (Fisher Scientific). Sections were fixed by immersing slides in three acetone preparations for a period of 5 min each. Sections were rinsed in PBS and incubated in blocking solution for 20 min. Slides were incubated for 18 h at 4ºC in a 1:20 dilution of mouse anti-human CD31 antibody (Dako Corporation, Carpinteria, CA), rinsed three times with PBS, and then incubated with anti-mouse Alexa 488 secondary antibody (1:500) (Molecular Probes). Slides were washed three times with PBS and then incubated in a 1:25 dilution of rabbit anti-human IL-6R (Santa Cruz) overnight at 4ºC. After being rinsed with PBS, slides were treated with a biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Biocare Medical, Walnut Creek, CA) for 30 min followed by a 30-min incubation with a 1:1000 dilution of Alexa-594-conjugated streptavadin (Molecular Probes). Primary antibodies were omitted in antibody control sections. Immunofluorescence microscopy was performed as described above. Endothelial cells were identified by red fluorescence, and IL-6R was identified by green fluorescence. Colocalization of endothelial cells and IL-6R (endothelial cells red + IL-6R green = yellow) was obtained by superimposing two images.

Functional Analysis of Microvascular Endothelial Cell IL-6R

To evaluate the functional status of IL-6R on microvascular endothelial cells, ovarian, and mesentery endothelial cells were stimulated with 100 ng/ml recombinant IL-6 (Biosource International, Inc.) for 5 min, 15 min, and 30 min. Cells were lysed, and 40 μg of protein was separated by SDS-PAGE. Rabbit anti-phospho-STAT3 (Tyr 705) antibodies (Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA), mouse anti-STAT3 antibodies (Cell Signaling), rabbit anti-phospho-MAPK (Cell Signaling) antibodies, and rabbit anti-MAPK antibodies (Cell Signaling) along with appropriate secondary antibodies were used to detect STAT3, phosphorylated STAT3, MAPK, and phosphorylated MAPK.

Cell Migration

To examine whether IL-6 induces endothelial cell migration, 24-well polycarbonate Transwell migration inserts (3.0 μm pore size; Fisher Scientific) were preincubated with serum-free DMEM for 2 h at 37°C. The medium was aspirated, and 700 μl of 1% FBS/DMEM containing various concentrations (50, 100, or 200 ng/ml) of IL-6 or bFGF was added to the lower compartment. Tissue-specific endothelial cells (3.5 × 104) in 1% FBS/DMEM were then added to each of the upper chambers and incubated at 37°C for 20 h. Cells in the upper compartment were removed mechanically by scraping. Cells that migrated to the underside of the membrane were stained and counted under a low power objective (40×). All assays were performed in triplicate, and experiments were repeated three times.

In Vivo Angiogenesis Assay

Sterile Gelfoam sponges (Pharmacia, Peapack, NJ) were cut into 5 × 5 × 7-mm sections and hydrated in PBS at 4ºC for 24 h. Excess PBS was removed from inserts by blotting onto sterile filter paper. A solution of 0.4% agarose (100 μl) containing either PBS, bFGF (1 μg/ml), IL-6 (1 μg/ml), or denatured IL-6 (1 μg/ml) was then added to each sponge. The sponges were incubated at room temperature for 1 h and then implanted subcutaneously into BALB/c mice as previously described (23). Two weeks later, sponges were harvested, embedded in OCT solution (Miles, Inc.), and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Ten-micrometer sections were transferred to positively charged slides.

Slides were fixed in cold acetone (5 min), acetone/chloroform [(1:1; v/v) (5 min)], and acetone (5 min), washed with PBS, and incubated for 20 min in blocking solution containing 5% normal horse serum and 1% normal goat serum in PBS. Samples were incubated for 18 h at 4°C in a 1:400 (v/v) dilution of rat monoclonal anti-mouse CD31 antibody (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) or anti-mouse VEGFR-1 antibody (Chemicon, Temecula, CA). Slides were washed 3 times with PBS and then incubated with Alexa 594-conjugated secondary antibody (Molecular Probes) for 1 h at room temperature. The microvascular density (MVD) of each insert was determined under immunofluorescence microscopy; we counted the number of structures labeling positive for CD31 in five random 0.159-mm2 fields at a magnification of 100× using Scion software (Scion Corporation, Frederick, MD).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis of results for cell migration and MVD were analyzed by Student’s _t_-test (two-tailed).

RESULTS

Expression of IL-6 and sIL-6R by Ovarian Tumor Cells

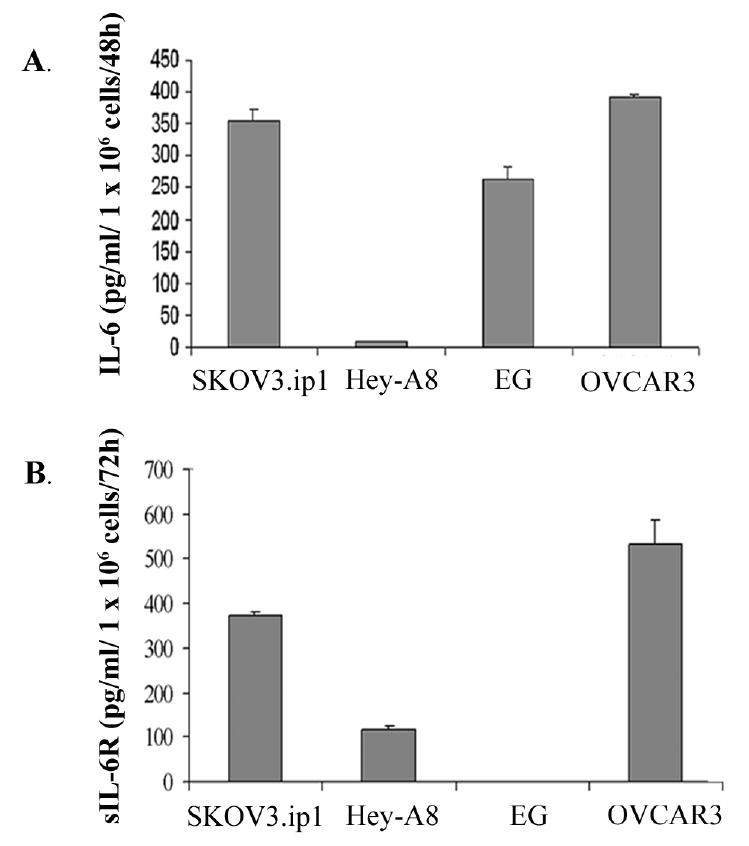

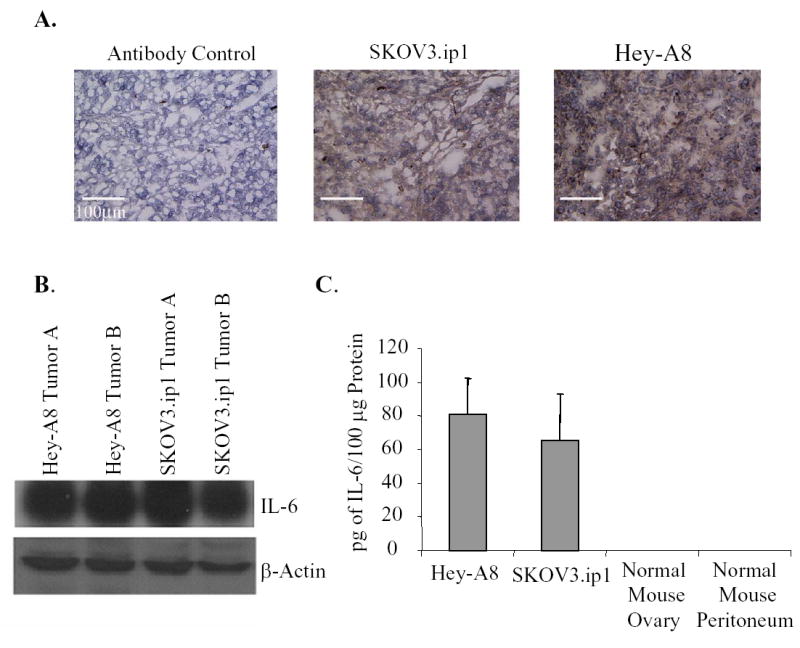

ELISA showed various levels of IL-6 expression among ovarian tumor cell lines growing in cell culture (Fig. 1A). The SKOV3.ip1, OVCAR3, and EG lines secreted high levels, but the Hey-A8 cells produced minimal amounts. sIL-6R expression also varied among the cultured cell lines: SKOV3.ip1, Hey-A8, and OVCAR-3 cells, but not EG cells, produced detectable levels (Fig. 1B). To determine whether the expression of IL-6 may be regulated by the tissue microenvironment, we implanted Hey-A8 and SKOV3.ip1 cells orthotopically into the peritoneal cavity of female mice. Unlike the case in vitro, both SKOV3.ip1 and Hey-A8 cells expressed IL-6 as determined by immunohistochemistry (Fig. 2A), Western blot (Fig. 2B), and ELISA (Fig. 2C). IL-6 was not detected in lysates prepared from normal mouse ovary and peritoneum, suggesting that the expression of IL-6 by tumor cells may be in response to factors present in the peritoneal microenvironment such as hypoxia or cytokines produced by host cells. Although IL-6 has been demonstrated to regulate VEGF expression in some cell lines (11), Hey-A8 cells that express high levels of IL-6 in vivo express minimal levels of VEGF. Furthermore, SKOV3.ip1 cells produce high levels of VEGF in vitro and in vivo. Incubation of SKOV3.ip1 cells with IL-6 neutralizing antibodies did not decrease VEGF production (data not shown), suggesting that in these two cell lines, VEGF production is independent of IL-6.

Fig. 1.

IL-6 and sIL-6R are expressed by human ovarian carcinoma cell lines in vitro. Tumor cell secretion of IL-6 (A) and sIL-6R (B) was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Values are the mean from duplicate experiments with error bars representing S.D.

Fig. 2.

Human ovarian carcinoma cell lines express IL-6 in vivo. While Hey-A8 cells secrete low levels of IL-6 in tissue culture conditions, both SKOV3.ip1 and Hey-A8 cells growing in the peritoneal cavity of female nude mice express IL-6 as determined by immunohistochemistry (A), Western analysis (B), and ELISA (C). Elisa data is graphed as mean ± S.D.

Expression of IL-6R on Tissue-Specific Microvascular Endothelial Cells

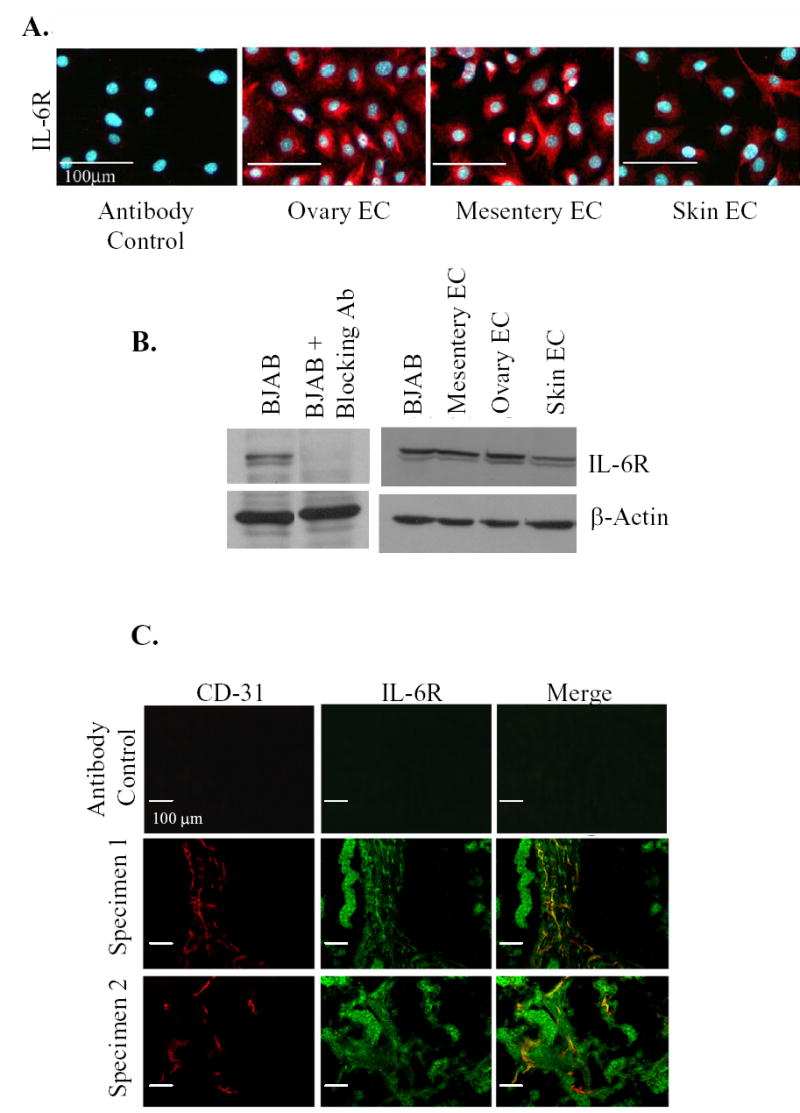

Both murine ovary and mesentery-derived microvascular endothelial cells expressed the receptor for IL-6 as determined by immunohistochemical evaluation (Fig. 3A) and Western blot analysis (Fig. 3B). Dermal-derived microvascular endothelial cells also expressed the IL-6R. Lysates from a mouse B-cell lymphoma cell line (BJAB) served as a positive control.

Fig. 3.

IL-6R is expressed on endothelial cells. Organ specific murine endothelial cells (ovary, mesentery, skin) express IL-6R as detected by immunohistochemistry (A) and Western analysis (B). (C) Fluorescent double-labelled immunohistochemistry of clinical human ovarian cancer specimens demonstrate IL-6R expression on tumor vasculature. Representative 100× images show immunohistochemistry for CD-31 (red), IL-6R (green), and the colocalization (yellow) of the IL-6R on endothelial cells.

IL-6R is Expressed on Endothelial Cells Within Normal Ovary and Human Ovarian Carcinoma Specimens

To determine whether the observed IL-6R expression by murine endothelial cells is consistent with the phenotype of the vasculature within human ovarian carcinomas, we evaluated 25 human ovarian cancer specimens and 3 normal ovaries. Figure 3C illustrates an example of the immunohistochemical analysis. IL-6R was expressed on both tumor-cell and tumor-associated endothelial cells (19/25 samples). IL-6R expression was also detected on endothelial cells from normal ovaries (2/3 samples).

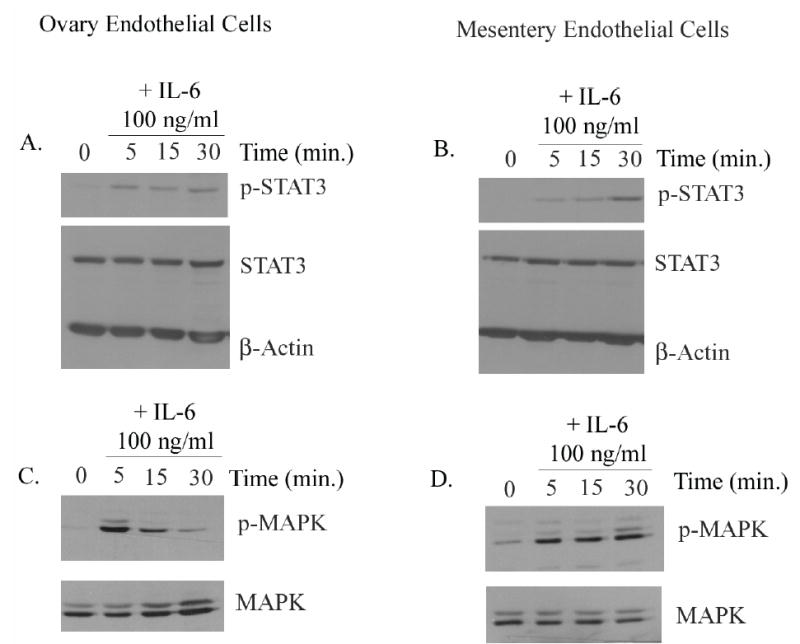

IL-6 Initiates Activation of Signal Transduction Pathways in Microvascular Endothelial cells

IL-6 exerts its biological effects by binding the non-signal-transducing IL-6R, thus activating the signal-transducing receptor gp130. The formation of an IL-6, IL-6R, and gp130 hexamer results in the phosphorylation of downstream signaling molecules such as signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 (STAT3), which then dimerizes, translocates to the nucleus, and functions as a transcription factor (24). To demonstrate that the IL-6R detected on endothelial cells is functional, endothelial cells were stimulated with 100 ng/ml of IL-6. The phosphorylation of downstream signaling molecules were then determined. Immunoblot analysis showed that IL-6 induced STAT3 phosphorylation in ovarian and mesentery endothelial cells (Fig. 4A,B). Phospho-STAT3 was detected as early as 5 min and for up to 30 min following the addition of IL-6 to the endothelial cells. Neutralizing antibodies against IL-6 or IL-6R blocked IL-6-induced STAT3 phosphorylation (data not shown). In addition to signaling via STAT3, IL-6/IL-6R/gp130 interactions have been shown to induce MAP kinase (mitogen-activated protein kinase) phosphorylation (25). Our Western analysis also indicated that stimulation of endothelial cells with IL-6 (100 ng/ml) induced transient phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK 1/2, p42/22, MAPK) (Fig. 4C,D). These data confirm that a functional IL-6R is expressed on endothelial cells.

Fig. 4.

IL-6 induces phosphorylation of STAT3 and MAPK in ovary and mesentery endothelial cells. Activation of STAT3 and MAPK was assessed by Western analysis. Endothelial cells derived from the ovary and mesentery were stimulated with IL-6 (100 ng/ml) for the indicated times, and total cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with phospho-specific anti-STAT3 and anti-MAPK antibodies. The addition of IL-6 resulted in enhanced phosphorylation of STAT3 and MAPK in ovarian (A,C) and mesentery (B,D) endothelial cells.

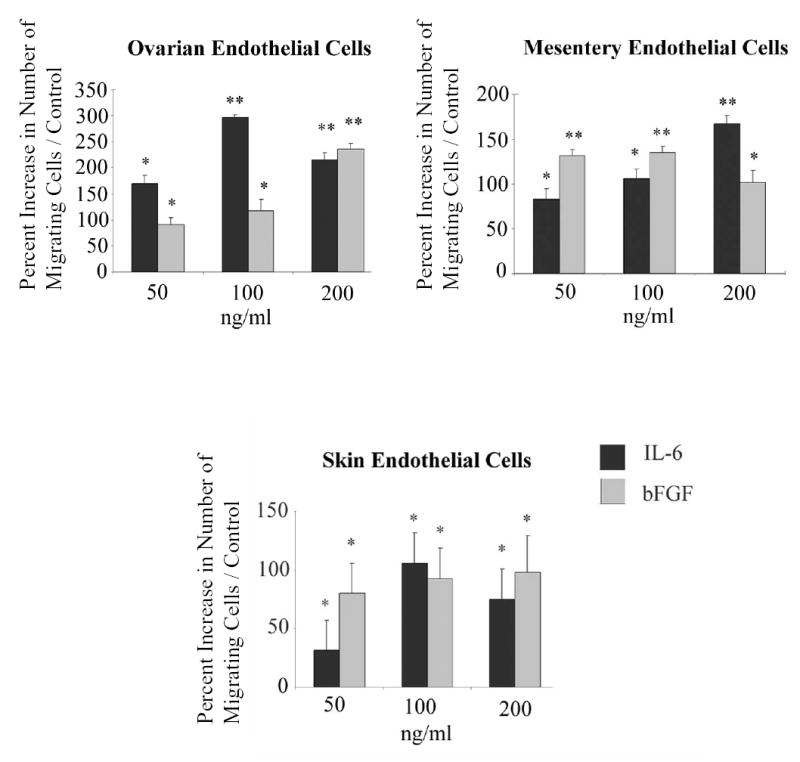

IL-6 Induces Migration of Ovarian and Mesentery Microvascular Endothelial Cells

To examine the chemotactic effects of IL-6 on ovarian, mesentery, and dermal endothelial cells, we stimulated cells with exogenous protein and measured their migration in a Boyden chamber assay. As shown in Figure 5, IL-6 significantly enhanced endothelial cell migration, reaching values essentially equivalent to that induced with bFGF. Denatured IL-6 had no effect on the migration of any cell line tested (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

IL-6 enhances endothelial cell migration in vitro. The ability of IL-6 to induce migration of endothelial cells was evaluated by Boyden chamber assay and quantified by bright field microscopy. For all three endothelial cell lines tested IL-6 significantly enhanced endothelial cell migration. Data shown is representative if three independent experiments performed in triplicate and is graphed as mean percent increase ± percent S.E. *P<0.05; **P<0.0001 versus control.

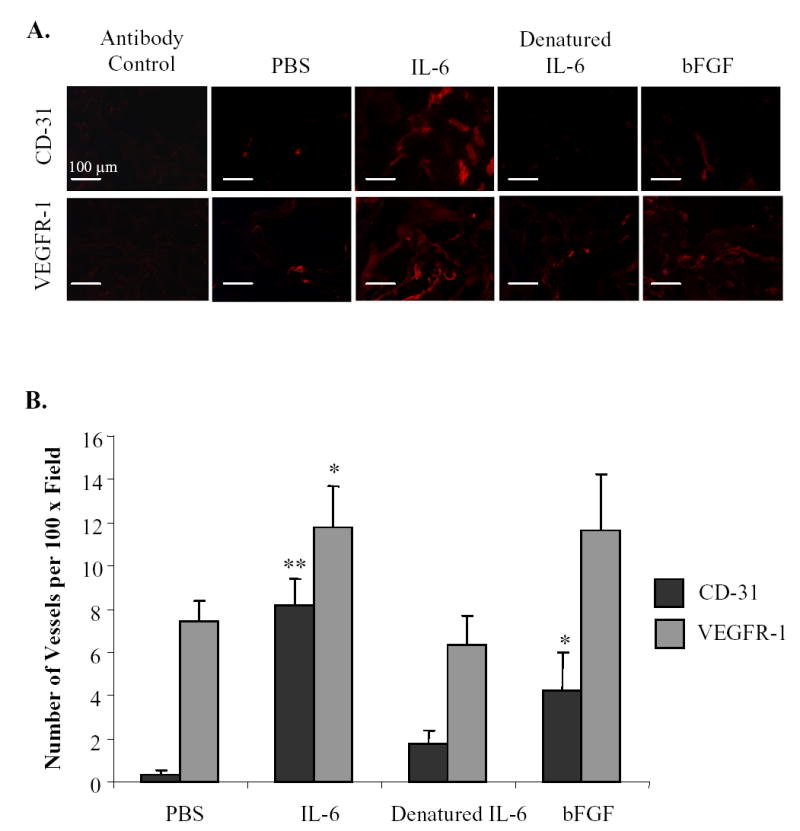

IL-6 Induces Angiogenesis In Vivo

To investigate the proangiogenic activity of IL-6 under in vivo conditions, we used the Gelfoam sponge assay (23) in which surgical hemostatic Gelfoam sponges containing 0.4% agarose and PBS, IL-6, heat-denatured IL-6, or bFGF were implanted into BALB/c mice. Because our results demonstrated that the effects of IL-6 on endothelial cells were not limited to the endothelial cells of the ovary and mesentery but also involved skin endothelial cells, and because the trauma of implanting sponges in the peritoneal cavity causes nonspecific angiogenesis, we implanted the sponges subcutaneously. After 2 wk, the Gelfoam sponges were harvested. Vessel density was determined by staining with antibodies against CD-31 and VEGFR-1. As shown in Figure 6, the Gelfoam sponges containing IL-6 had significantly (P<0.0001) more CD-31+ and VEGFR-1+ vessels than sponges containing PBS or denatured IL-6. The endothelial cells within the sponges were negative for VEGF-A (data not shown).

Fig. 6.

IL-6 induces angiogenesis in vivo. Surgical hemostatic gelfoam sponges containing PBS, IL-6, heat denatured IL-6, or bFGF were implanted subcutaneously into BALB/c mice. After two weeks, sponges were harvested, fixed, sectioned, and immunostained with antibodies against CD-31 and VEGFR-1 to determine microvessel density. (A) Representative images of immunohistochemistry. (B) Vessel density is graphed as mean ± S.E. *P<0.05; **P< 0.0001 versus control.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies have demonstrated that IL-6 can function as a regulator of ovarian tumor cell proliferation and migration (26, 27) and that IL-6 levels are significantly elevated in the serum of women with ovarian cancer and hence associated with poor prognosis (9, 10). We wished to determine whether IL-6 facilitates progression of this disease by stimulating angiogenesis. The results reported here provide new information regarding the role of IL-6 expression in ovarian carcinoma progression. First, ovarian tumor cells secreted significant quantities of IL-6 and sIL-6 receptor. Second, both murine and human tumor-associated microvascular endothelial cells residing in the peritoneum expressed IL-6 receptors. Third, the microvascular endothelial cell IL-6 receptor was functional and stimulation with IL-6 activated STAT3 and MAPK signaling and induced endothelial cell migration. Fourth, IL-6 was a potent inducer of the formation of new blood vessels in vivo.

All but one of the malignant ovarian tumor cell lines under study secreted measurable levels of sIL-6R, which is capable of binding its ligand and mediating signal transduction on cells that do not express membrane bound IL-6R. This process, referred to as trans-signaling, occurs when IL-6/sIL-6R complex binds the membrane-bound signal transducer gp130, which is ubiquitously expressed (28). Therefore, the soluble form of the IL-6R not only potentiates the effects of secreted IL-6 but also widens the range of cells affected by this cytokine. The observation that sIL-6R is expressed by ovarian tumor cells warrants further investigation to determine the significance to cancer progression.

Previous studies have indicated that endothelial cells lack receptors for IL-6 (16). However, we found that endothelial cells derived from organs relevant to the progression of ovarian carcinoma expressed IL-6R. This observation was consistent with our findings that the IL-6R is expressed on endothelial cells within clinical specimens of human ovarian carcinomas as well as on endothelial cells of the normal human ovary. Additionally, treatment of endothelial cells with IL-6 activated STAT3 and MAPK, signal transduction molecules known to regulate cellular processes including proliferation and migration. While we did not detect any significant increase in endothelial cell proliferation or VEGF production as a result of IL-6 stimulation (unpublished data), we did observe that IL-6 significantly enhances endothelial cell migration, a key step in the process of angiogenesis. We also observed that endothelial cells derived from the skin express IL-6R. Because IL-6 was capable of inducing a robust angiogenic response in the cutaneous microenvironment, it is possible that IL-6 also contributes to the vascularization of skin tumors. Our finding correlates with published reports that serum levels of IL-6 are elevated in patients with metastatic melanoma (29) and that overexpression of IL-6 in basal cell carcinoma is associated with enhanced angiogenesis and tumor growth (30). Additional evidence for the role of IL-6 in angiogenesis comes from a most recent report that a peptide specifically binding to the IL-6R can inhibit vessel formation and growth of tumors in the subcutis of SCID mice (31).

The identification of an angiogenic function of IL-6 in ovarian carcinoma may have important implications for therapies designed to target the tumor vasculature. It has been well established that tumor cells are heterogeneous and can produce a wide variety of proangiogenic molecules. Previous studies have revealed the importance of proangiogenic factors such as platelet-derived growth factor (32), VEGF/VPF (33), and IL-8 (34) in ovarian carcinoma. Because tumor cells secrete a variety of proangiogenic molecules, therapies targeting IL-6 in addition to other proangiogenic factors will likely be useful in the treatment of women with ovarian carcinoma.

Acknowledgments

We thank Rachel Tsan for technical assistance, Walter Pagel for critical editorial review, and Lola López for expert assistance with the preparation of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Grant support: This work was supported in part by Cancer Center Support Core grant CA16672 and SPORE in Prostate Cancer grant CA90270l and SPORE in Ovarian Cancer grant CA93639 from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Folkman J. What is the evidence that tumors are angiogenesis dependent? J Natl Cancer Inst. 1990;82:4–6. doi: 10.1093/jnci/82.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kumar R, Fidler IJ. Angiogenic Molecules and Cancer Metastasis. In Vivo. 1998;12:27–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanahan D, Folkman J. Patterns and emerging mechanisms of the angiogenic switch during tumorigenesis. Cell. 1996;86:353–64. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80108-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fidler IJ. Angiogenic heterogeneity: regulation of neoplastic angiogenesis by the organ microenvironment (Editorial) J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:1040–1. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.14.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirano T, Yasukawa K, Harada H, et al. Complementary DNA for a novel human interleukin (BSF-2) that induces B lymphocytes to produce immunoglobulin. Nature. 1986;324:73–6. doi: 10.1038/324073a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirano T. Interleukin 6 and its receptor: ten years later. Int Rev Immunol. 1998;16:249–84. doi: 10.3109/08830189809042997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salgado R, Junius S, Benoy I, et al. Circulating interleukin-6 predicts survival in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2003;103:642–6. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Culig Z, Bartsch G, Hobisch A. Interleukin-6 regulates androgen receptor activity and prostate cancer cell growth. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2002;197:231–8. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(02)00263-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Plante M, Rubin SC, Wong GY, Federici MG, Finstad CL, Gastl GA. Interleukin-6 level in serum and ascites as a prognostic factor in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer. 1994;73:1882–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940401)73:7<1882::aid-cncr2820730718>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tempfer C, Zeisler H, Sliutz G, Haeusler G, Hanzal E, Kainz C. Serum evaluation of interleukin 6 in ovarian cancer patients. Gynecol Oncol. 1997;66:27–30. doi: 10.1006/gyno.1997.4726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cohen T, Nahari D, Cerem LW, Neufeld G, Levi BZ. Interleukin 6 induces the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:736–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.2.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campbell IL, Abraham CR, Masliah E, et al. Neurologic disease induced in transgenic mice by cerebral overexpression of interleukin 6. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10061–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.21.10061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fee D, Grzybicki D, Dobbs M, et al. Interleukin 6 promotes vasculogenesis of murine brain microvessel endothelial cells. Cytokine. 2000;12:655–65. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1999.0599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin ZQ, Kondo T, Ishida Y, Takayasu T, Mukaida N. Essential involvement of IL-6 in the skin wound-healing process as evidenced by delayed wound healing in IL-6-deficient mice. J Leukoc Biol. 2003;73:713–21. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0802397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Motro B, Itin A, Sachs L, Keshet E. Pattern of interleukin 6 gene expression in vivo suggests a role for this cytokine in angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:3092–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.8.3092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Romano M, Sironi M, Toniatti C, et al. Role of IL-6 and its soluble receptor in induction of chemokines and leukocyte recruitment. Immunity. 1997;6:315–25. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80334-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hatzi E, Murphy C, Zoephel A, et al. N-myc oncogene overexpression downregulates IL-6; evidence that IL-6 inhibits angiogenesis and suppresses neuroblastoma tumor growth. Oncogene. 2002;21:3552–61. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerritsen ME. Functional heterogeneity of vascular endothelial cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 1987;36:2701–11. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(87)90252-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rajotte D, Arap W, Hagedorn M, Koivunen E, Pasqualini R, Ruoslahti E. Molecular heterogeneity of the vascular endothelium revealed by in vivo phage display. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:430–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI3008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu D, Wolf JK, Scanlon M, Price JE, Hung MC. Enhanced c-erbB-2/neu expression in human ovarian cancer cells correlates with more severe malignancy that can be suppressed by E1A. Cancer Res. 1993;53:891–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Langley RR, Ramirez KM, Tsan RZ, Van Arsdall M, Nilsson MB, Fidler IJ. Tissue-specific microvascular endothelial cell lines from H-2Kb-tsA58 mice for studies of angiogenesis and metastasis. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2971–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jat PS, Noble MD, Ataliotis P, et al. Direct derivation of conditionally immortal cell lines from an H-2Kb-tsA58 transgenic mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:5096–100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.12.5096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McCarty MF, Baker CH, Bucana CD, Fidler IJ. Quantitative and qualitative in vivo angiogenesis assay. Int J Oncol. 2002;21:5–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hirano T, Ishihara K, Hibi M. Roles of STAT3 in mediating the cell growth, differentiation and survival signals relayed through the IL-6 family of cytokine receptors. Oncogene. 2000;19:2548–56. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Daeipour M, Kumar G, Amaral MC, Nel AE. Recombinant IL-6 activates p42 and p44 mitogen-activated protein kinases in the IL-6 responsive B cell line, AF-10. J Immunol. 1993;150:4743–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Syed V, Ulinski G, Mok S, Ho S. Reproductive hormone-induced, STAT3-mediated interleukin 6 action in normal and malignant human ovarian surface epithelial cells. J Nat Cancer Inst. 2002;94:617–28. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.8.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Obata N, Tamakoshi K, Shibata K, Kikkawa F, Tomoda Y. Effects of interleukin-6 on in vitro cell attachment, migration, and invasion of human ovarian carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 1997;17:337–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kallen K. The role of transsignalling via the agonistic soluble IL-6 receptor in human diseases. Biochem Biophys Acta. 2002;1592:323–43. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4889(02)00325-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moretti S, Chiarugi A, Semplici F, et al. Serum imbalance of cytokines in melanoma patients. Melanoma Res. 2001;11:395–9. doi: 10.1097/00008390-200108000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jee SH, Shen SC, Chiu HC, Tsai WL, Kuo ML. Overexpression of interleukin-6 in human basal cell carcinoma cell lines increases anti-apoptotic activity and tumorigenic potency. Oncogene. 2001;20:198–208. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Su J, Kai K, Chen C, et al. A novel peptide specifically binding to interleukin-6 receptor (gp80) inhibits angiogenesis and tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2005;65:4827–35. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Apte SM, Fan D, Killion JJ, Fidler IJ. Targeting the platelet-derived growth factor receptor in antivascular therapy for human ovarian carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:897–908. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-1151-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu L, Yoneda J, Herrera C, Wood J, Killion JJ, Fidler IJ. Inhibition of malignant ascites and growth of human ovarian carcinoma by oral administration of a potent inhibitor of the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinases. Int J Oncol. 2000;16:445–54. doi: 10.3892/ijo.16.3.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu L, Fidler IJ. Interleukin 8: an autocrine growth factor for human ovarian cancer. Oncol Res. 2000;12:97–106. doi: 10.3727/096504001108747567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]