Altered p‐STAT3 (tyr705) expression is associated with histological grading and intratumour microvessel density in hepatocellular carcinoma (original) (raw)

Abstract

Background

Constitutive activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 at tyrosine residue 705 (p‐STAT3 (tyr705)) has been associated with many types of human cancers. However, its potential roles and biological effects in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) are not well established.

Aim

To explore whether an altered p‐STAT3 (tyr705) expression is associated with angiogenesis or proliferation and thereby plays a part in HCC development.

Methods

Paraffin‐wax‐embedded sections from 69 patients with HCC were collected in this study. Using a semiquantitative immunohistochemical staining method, the expression patterns of p‐STAT3 (tyr705) in both HCC lesions and the adjacent non‐tumorous liver parenchyma were analysed. The results obtained were further correlated with intratumour microvessel density (MVD), Ki‐67 expression, clinicopathological parameters and overall survival.

Results

A strong p‐STAT3 (tyr705) nuclear staining was observed in 49.3% of HCC lesions, but was reported only in 5.8% of the adjacent non‐tumorous liver parenchyma (p<0.001). The expression of p‐STAT3 (tyr705) in HCC lesions was significantly and positively correlated with the intratumour MVD (p = 0.002), but not with Ki‐67 expression. No significant correlation of p‐STAT3 (tyr705) was found in addition to histological grading (p = 0.019). Multivariate Cox regression analysis showed that p‐STAT3 (tyr705) expression was a significant predictor of overall survival for HCC (p = 0.036), although the Kaplan–Meier survival curves showed no significant difference between the high and low p‐STAT3 (tyr705) expression subgroups.

Conclusions

The results showed that p‐STAT3 (tyr705) expression was closely correlated with histological grading and intratumour MVD in HCC. Thus, the potential role of p‐STAT3 (tyr705) in HCC development may be through these correlations.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fifth most common malignancy in the world and is estimated to cause approximately half a million deaths annually.1 In Taiwan, HCC is a highly prevalent malignancy and now the foremost cause of death from malignancy in Taiwanese men.2 Although the underlying mechanisms of HCC development remain to be investigated, accumulating evidence has implicated that signal transducer and activator of transcription protein 3 (STAT3) may be involved in HCC development, directly or indirectly.3,4

Constitutively activated STAT3, through its phosphorylation at tyrosine residue 705, has been reported in many human cancers, including carcinomas of the breast, lung, prostate and ovary, and melanoma.5,6,7,8,9 Mostly, activated STAT3 participates in carcinogenesis through either promoting angiogenesis or stimulating cell proliferation.10,11,12 However, its potential clinical roles, and also its possible biological effects in HCC, remain mostly undetermined so far. Recently, activated STAT3 is shown in the progression of viral hepatitis and in the oncogenesis of the liver associated with hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV).13,14,15,16,17,18 In addition, STAT3 activity is increased in chemically ‐induced HCC.19 These results seem to implicate that activated STAT3 may play a crucial part in HCC development. However, intriguingly, activated STAT3 also participates in the normal regeneration/repair of hepatocytes, the protective process during liver injury and fibrosis, and also normal glucose homeostasis.20,21,22,23,24,25 Thus, exploring its potential clinical roles and analysing its possible biological effects in HCC will be an important issue.

In this study, we characterised the expression patterns of phosphorylated STAT3 at tyrosine residue 705 (p‐STAT3 (tyr705)) in HCC lesions as well as in the adjacent non‐tumorous liver parenchyma using immunohistochemistry, and delineated the possible role of p‐STAT3 (tyr705) expression in the tumorigenesis of HCC through analysing whether its expression was correlated with intratumour microvessel density (MVD), Ki‐67 expression, clinicopathological parameters and overall survival.

Materials and methods

Surgical specimens

In all, 174 surgically resected HCCs were obtained from the Department of Surgery, Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital, Kaohsiung, Taiwan, between January 1995 and December 2003. For the purposes of this study, 69 cases (52 men and 17 women; mean (SD) age 52.8 (12.36) years; range 30–82 years) that met the following criteria were identified: (1) curative hepatectomy; (2) absence of prior treatment, such as transarterial chemoembolisation and percutaneous ethanol injection therapy; and (3) no apparent distant metastases. All the patients were strictly followed up for a mean (SD) period of (32.6 (23.7) months (range 0.5–111.6 months). The specimens were routinely fixed in 10% buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin wax. Tumour size of study cases (range 0.5–14.0 cm; average 4.6 cm) was measured as the greatest dimension of the tumour by gross examination. An adequate number of tissue sections from each tumour (average 5 sections; range 3–14 sections depending on tumour diameter) with surrounding tissue were available for this study, and one tissue block per case that was representative of tumour grading, vascular proliferation and adjacent hepatitis grading was selected. For each tissue specimen, several 3 μm‐thick sections were cut. One section from each specimen was stained with H&E for conventional light microscopic analysis, and the histopathological diagnosis and tumour grading based on multiple blocks were confirmed by two independent pathologists (S‐FY and C‐YC).

Clinicopathological parameters including age, gender, serum α‐fetoprotein levels (⩽20 vs >20 ng/ml), recurrence (present or absent), hepatitis activity of the adjacent non‐tumorous liver parenchyma (necroinflammation and fibrosis), tumour size (⩽5 vs >5 cm), histological grading (well/moderately differentiated vs poorly differentiated), tumour stage (I/II vs III/IV) and vascular invasion (including vascular invasion and/or tumour thrombi in the portal or hepatic vein) were retrospectively recorded (tables 1 and 2). Histological grading and staging was according to the World Health Organization histological classification and the pathological tumour–node–metastases classification, respectively.26 The hepatitis activity of the adjacent non‐tumorous parenchyma that is as remote from the HCC as possible was evaluated based on multiple tissue blocks and scored by the Scheuer system accordingly.27

Table 1 Correlation of p‐STAT3 (tyr705) expression in hepatocellular carcinoma with clinicopathological parameters.

| Variables | n | p‐STAT3 (tyr705) | p Value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | ||

| Sex | 0.842 | ||

| Male | 52 | 14 | 38 |

| Female | 17 | 5 | 12 |

| Serum α‐fetoprotein (ng/ml) | 0.576 | ||

| ⩽20 | 26 | 8 | 18 |

| >20 | 33 | 8 | 25 |

| Undetermined | 10 | ||

| Recurrence | 0.519 | ||

| Present | 23 | 7 | 16 |

| Absent | 35 | 8 | 27 |

| Undetermined | 11 | ||

| Tumour size (cm) | 0.176 | ||

| ⩽5 | 45 | 10 | 35 |

| >5 | 24 | 9 | 15 |

| Histological grade | 0.019† | ||

| WD/MD | 61 | 14 | 47 |

| PD | 8 | 5 | 3 |

| Tumour stage | 0.643 | ||

| I/II | 50 | 13 | 37 |

| III/IV | 19 | 6 | 13 |

| Vascular invasion | 0.541 | ||

| Present | 22 | 5 | 17 |

| Absent | 47 | 14 | 33 |

Table 2 Correlation of p‐STAT3 (tyr705) expression in hepatocellular carcinoma with viral infection and the adjacent hepatitis activity.

| Variables | n | p‐STAT3 (tyr705) | p Value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low (%) | High (%) | ||

| Viral infection | 0.345 | ||

| HBV | 36 | 10 (14.5) | 26 (37.7) |

| HCV | 20 | 7 (10.1) | 13 (18.8) |

| HBV+HCV | 6 | 2 (2.9) | 4 (5.8) |

| No infection | 7 | 0 (0.0) | 7 (10.1) |

| Necroinflammation | 0.268 | ||

| Grade 1 | 3 | 0 (0.0) | 3 (4.3) |

| Grade 2 | 5 | 1 (1.4) | 4 (7.2) |

| Grade 3 | 5 | 3 (2.3) | 2 (7.2) |

| Grade 4 | 56 | 15 (21.7) | 41 (81.2) |

| Fibrosis | 0.772 | ||

| Stage 1 | 1 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.4) |

| Stage 2 | 10 | 7 (10.1) | 13 (18.8) |

| Stage 3 | 19 | 5 (7.2) | 14 (20.3) |

| Stage 4 | 29 | 7 (10.1) | 22 (31.9) |

Immunohistochemistry

Several 3 μm‐thick sections from representative tissue blocks were cut, deparaffinised with xylene rinse and rehydrated into distilled water through graded alcohol. Antigen retrieval was enhanced by autoclaving slides in sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 30 min. Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched by 30 min of incubation in a 0.3% hydrogen peroxide/methanol buffer. The slides were then incubated with primary mouse monoclonal anti‐p‐STAT3 (tyr705) antibody (Cell Signalling, Beverly, Massachusetts, USA) at a dilution of 1:200 overnight at 4°C. Slides were washed three times in phosphate buffer solution and further incubated with a biotinylated secondary antibody for 20 min at room temperature. Antigen–antibody complexes were detected by the avidin–biotin–peroxidase method using diaminobenzidine as a chromogenic substrate (Dako, California, USA). Finally, the slides were counterstained with haematoxylin and then examined by light microscopy. CD31 (1:30; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) and Ki‐67 (1:75, Dako) staining were assessed using purified anti‐human monoclonal antibodies according to the manufacturer. All of the immunostaining was performed on the same tissue block for each case.

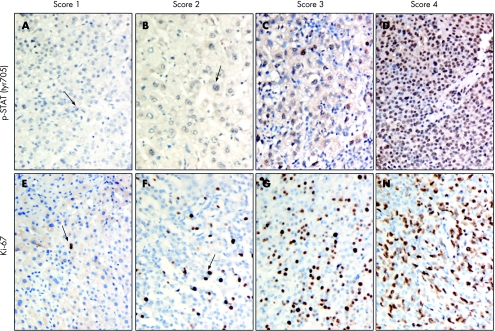

Evaluation of p‐STAT3 (tyr705), CD31 and Ki‐67 immunohistochemical staining

The results for nuclear p‐STAT3 (tyr705) staining were assigned by a combined score based on the proportion grade and intensity grade. The proportion grade represented the estimated fraction of nuclear staining‐positive tumour cells (proportion grade 1, ⩽25%; proportion grade 2, 26–50%; proportion grade 3, 51–75%; proportion grade 4, 76%). The intensity grade represented the estimated average nuclear staining intensity of positive tumour cells (intensity grade 1, minimal staining; intensity grade 2, weak staining; intensity grade 3, moderate staining; intensity grade 4, strong staining). The combined score was expressed as the sum of the proportion and intensity grades and then divided into four major scores: score 1, summed grades 1–2 (fig 1A); score 2, summed grades 3–4 (fig 1B); score 3, summed grades 5–6 (fig 1C); score 4, summed grades 7–8 (fig 1D). As for Ki‐67, the nuclear immunostaining results were also divided into four scores based on the proportion score: score 1, ⩽25% positive nuclear staining of tumour cells (fig 1E); score 2, 26–50% positive nuclear staining of tumour cells (fig 1F); score 3, 51–75% positive nuclear staining of tumour cells (fig 1G); score 4, ⩾76% positive nuclear staining of tumour cells (fig 1H). Notably, more than 1000 cells expressed in 3–4 different high‐power field (×400) areas with the highest degree of immunoreactivity in each representative section were analysed for each section. Sections of breast cancer tissue were used as positive controls for p‐STAT3 (tyr705) immunostaining, whereas sections of tonsil tissues known to be positive for Ki‐67 expression were included as positive controls for Ki‐67. Negative control was obtained by substituting the primary antibody with the immunoglobulin fraction of non‐immune mouse serum in each staining run (for p‐STAT3 (tyr705) and Ki‐67).

Figure 1 Scoring systems for phosphorylated signal transducer and activator of transcription protein 3 at tyrosine residue 705 (p‐STAT3 (tyr705; A–D) and Ki‐67 (E–H) immunostaining. The results for nuclear p‐STAT3 (tyr705) staining were assigned by a combined score based on the proportion grades and intensity grades. Arrows indicate the positive cells. Original magnification,×400.

Intratumour MVD, assessed by immunoreactive CD31, was determined according to Weidner.28 The immunostained sections were scanned at low magnification (×40) and the tumour area with the highest density of distinctly highlighted microvessels (“hot spot”) was selected. MVD was then determined in the hot spot by counting all vessels at a total magnification of ×200 (×20 objective and ×10 ocular, 0.94 mm2 per field), and the mean of counts for three fields was calculated. Large vessels with thick muscular walls were excluded from the counts, and vessel lumens were not necessary for a structure to be defined as a vessel. The immunostaining for p‐STAT3 (tyr705), Ki‐67 and MVD was determined separately for each specimen and estimated by two independent pathologists (S‐FY and C‐YC) without prior knowledge of each patient's clinical information. The rare cases with discordant scores were re‐evaluated and scored on the basis of consensual opinion.

Statistical analysis

Contingency table methods were used to analyse the correlation between p‐STAT3 (tyr705) and other variables. p‐STAT3 (tyr705) and Ki‐67 staining statuses were further classified as low expression (scores 1/2) or high expression (scores 3/4) before statistical evaluation. A MVD of 52.5 (overall mean value) was used as baseline to subgroup total HCC cases into high (⩾52.5) and low (<52.5) MVD subgroups, respectively. For staging and tumour dimensions, stage I/II and tumour size >5 cm were used as baseline, respectively. Significance was evaluated by t test, χ2 test and Fisher's exact test. Survival curves were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method, whereas the significance was determined by log rank test. Multivariate OR (odds ratio) was calculated using Cox proportional hazards regression. All calculations were performed using the SPSS V.10.0 statistical software package. A value of p <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Expression profiles of p‐STAT3 (tyr705), Ki‐67 and MVD in HCC lesions and in the adjacent non‐tumorous liver parenchyma

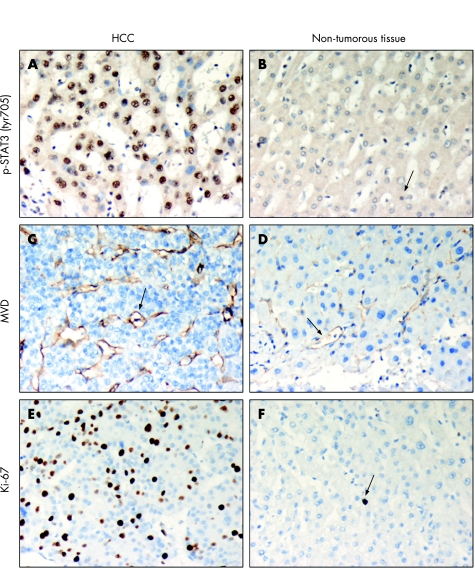

Table 3 summarises the expression levels of p‐STAT3 (tyr705) and Ki‐67 evaluated in 69 HCC cases. Immunohistochemical results showed that the p‐STAT3 (tyr705) staining was predominantly seen in the nucleus of hepatocytes, bile duct epithelium and leucocytes. Relatively low p‐STAT3 (tyr705) expression was detected in the parenchymal cells compared to with the hepatocytes. In addition, the HCC lesions exhibited a higher nuclear staining of p‐STAT3 (tyr705) than the adjacent non‐tumorous hepatocytes (fig 2A, B). A strong immunostaining (score 4) of p‐STAT3 (tyr705) was observed in 49.3% of HCC cases in contrast with a minimal nuclear immunostaining of p‐STAT3 (tyr705) (score 1) observed in 13.0% of HCC cases (table 3). By contrast, only 5.8% of the adjacent non‐tumorous liver parenchyma showed a strong p‐STAT3 (tyr705) nuclear staining, whereas 43.5% showed a minimal p‐STAT3 (tyr705) nuclear staining (table 3). Most importantly, the expression of p‐STAT3 (tyr705) in HCC lesions was significantly higher than that of the non‐tumorous liver tissues (table 3, p<0.001).

Table 3 Immunihistochemistry of p‐STAT3 (tyr705) and Ki‐67 expressions and microvessel density in hepatocellular carcinoma and the adjacent non‐tumorous liver parenchyma.

| HCC (n = 69), % | Non‐tumorous parenchyma (n = 69), % | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| p‐STAT3 (tyr705) | <0.001* | ||

| Score 1 | 9 (13.0) | 30 (43.5) | |

| Score 2 | 11 (15.9) | 25 (36.2) | |

| Score 3 | 15 (21.7) | 10 (14.5) | |

| Score 4 | 34 (49.3) | 4 (5.8) | |

| Ki‐67 | <0.001* | ||

| Score 1 | 37 (53.6) | 65 (94.3) | |

| Score 2 | 17 (24.6) | 1 (1.4) | |

| Score 3 | 11 (15.9) | 3 (4.3) | |

| Score 4 | 4 (5.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

| MVD | 53.43 (21.19) | 15.85 (13.05) | <0.001† |

Figure 2 Phosphorylated signal transducer and activator of transcription protein 3 at tyrosine residue 705 (p‐STAT3 (tyr705);A, B), CD31 (C, D) and Ki‐67 (E, F) immunostaining in tumour and the adjacent non‐tumorous liver parenchyma. The tumour cells (arrows) showed an intense nuclear staining of p‐STAT3 (tyr705) and Ki‐67, and a high microvessel density (MVD) determined by CD31staining, whereas the adjacent non‐tumorous tissue (triangles) showed relatively low p‐STAT3 (tyr705) and Ki‐67 staining as well as a low MVD. Original magnification ×400. HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma.

Distinct Ki‐67 staining was predominantly seen in the nuclei of the epithelial cells, such as hepatocytes and bile epithelial cells. The majority of tumour cells (53.6%) and the adjacent non‐tumorous cells (94.3%) revealed a very low Ki‐67 expression in our HCC cases (table 3, fig 2E, F). On the other hand, the mean (SD) intratumour MVD of the total HCC cases was 53.43 (21.19; range 15.0–104.67), whereas the mean (SD) MVD of the adjacent non‐tumorous parenchyma was 15.85 (13.05; range 1.3–90.0; table 3). There was a significant difference in either Ki‐67 expression or MVD between HCC and the non‐tumorous liver tissues (table 3, p<0.001 and <0.001, respectively).

Correlation of p‐STAT3 (tyr705) expression with Ki‐67 expression, MVD, clinicopathological parameters and overall survival in HCC

To explore the potential role of p‐STAT3 (tyr705) in HCC, the expression levels of p‐STAT3 (tyr705) in HCC lesions and in the non‐tumorous liver tissues were further correlated with Ki‐67 expression and MVD (table 4). Intriguingly, we found that the expression of p‐STAT3 (tyr705) was significantly and positively correlated with intratumour MVD (p = 0.002), but not with Ki‐67 expression, in HCC lesions (table 4). However, there was no significant correlation among p‐STAT3 (tyr705) expression, Ki‐67 expression and MVD in the non‐tumorous liver parenchyma (table 4).

Table 4 Correlation of p‐STAT3 (tyr705) expression of tumour (HCC) (p‐STAT3 (tyr705)t) and the adjacent non‐tumorous liver parenchyma (p‐STAT3 (tyr705)n) with microvessel density and Ki‐67 expression.

| p‐STAT3 (tyr705)t | p Value* | p‐STAT3 (tyr705)n | p Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Low | High | Low | |

| MVD | 0.002† | 0.611 | ||

| High | 31 | 4 | 0 | 1 |

| Low | 19 | 15 | 14 | 54 |

| Ki‐67 | 0.932 | 0.372 | ||

| High | 11 | 4 | 0 | 3 |

| Low | 39 | 15 | 14 | 52 |

We further compared the p‐STAT3 (tyr705) expression of HCC lesions between different patient subgroups according to various clinicopathological parameters (table 1). A significant correlation of p‐STAT3 (tyr705) was observed only with histological grading (p = 0.019). No significant correlation of p‐STAT3 (tyr705) was found with gender, serum α‐fetoprotein levels, recurrence, tumour size, tumour stage and vascular invasion (table 1), as well as with the viral infections (HBV and HCV), the grade of necroinflammation and the stage of fibrosis in the adjacent non‐tumorous liver parenchyma (table 2). The Kaplan–Meier survival curves showed that there was no significant difference between the high and low p‐STAT3 (tyr705) expression subgroup in HCC (data not shown). However, when a multivariate Cox proportional hazards model was constructed, we found that histological grading was the strongest predictor of overall survival for HCC (OR 43.57, 95% CI 2.50 to 762.21, p = 0.010; table 5). In addition, p‐STAT3 (tyr705) expression, intratumour MVD, Ki‐67 expression and gender were also the predictors of overall survival for HCC (table 5).

Table 5 COX regression analysis of hepatocellular carcinoma cases.

| Characteristics | OR (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| p‐STAT3 (tyr705) expresser (high/low) | 0.11 (0.13 to 0.86) | 0.036* |

| MVD (⩽52.5) | 17.77 (1.64 to 194.54) | 0.018* |

| Ki‐67 expresser (high/low) | 11.74 (1.34 to 102.87) | 0.026* |

| Age (⩽50 years) | 4.63 (0.92 to 23.36) | 0.064 |

| Gender (male/female) | 12.85 (1.09 to 151.24) | 0.042* |

| Serum α‐fetoprotein (⩽20 ng/ml) | 0.42 (0.10 to 1.80) | 0.240 |

| Recurrence | 3.18 (0.64 to 15.88) | 0.160 |

| Viral infection | 0.79 (0.25 to 2.54) | 0.697 |

| Necroinflammation | 17.85 (0.85 to 375.14) | 0.064 |

| Fibrosis | 2.37 (0.83 to 6.81) | 0.109 |

| Tumour size (⩽5 cm) | 1.56 (0.39 to 6.23) | 0.532 |

| Histological grade | 43.57 (2.50 to 762.21) | 0.010* |

| Vascular invasion | 1.27 (0.25 to 6.51) | 0.778 |

| Tumour stage | 1.66 (0.47 to 5.89) | 0.430 |

Discussion

In the present study, we found that the HCC lesions exhibited a significantly higher nuclear expression of p‐STAT3 (tyr705) over the adjacent non‐tumorous liver parenchyma (table 3, p<0.001), and an increased p‐STAT3 (tyr705) expression in HCC lesions was significantly correlated with an increased histological grading (table 1, p = 0.019). Consistent with Feng et al29 although they did not find such correlations, we found that an p‐STAT3 (tyr705) expression in HCC lesions might play roles in advanced HCC development. Notably, higher p‐STAT3 (tyr705) expressions have been found in many poorly differentiated carcinomas, such as head and neck cancer, ovarian carcinoma and cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma.30,31,32 On the other hand, although hepatocarcinogenesis is known to be associated with cirrhosis and viral hepatitis, in the present study, we found no significant correlation of tumorous p‐STAT3 (tyr705) expression with the stage of fibrosis and the grade of necroinflammation in the adjacent non‐tumorous liver parenchyma (table 2). Meanwhile, there was no significant correlation between tumorous p‐STAT3 (tyr705) expression and virus‐associated HCC, including HCV and HBV (table 2). Taken together, our results indicated that the tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT3 might play roles in HCC development. However, inflammation and fibrosis as well as viral infections might not directly influence the potential role of p‐STAT3 (tyr705) in HCC.

Take‐home messages

- A strong phosphorylated signal transducer and activator of transcription protein 3 at tyrosine residue 705 (p‐STAT3 (tyr705)) nuclear staining was significantly increased in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) lesions than in adjacent non‐tumorous liver parenchyma (49.3% vs 5.8%, p<0.001).

- Furthermore, the expression of p‐STAT3 (tyr705) in HCC lesions was significantly correlated with the intratumour microvessel density (MVD) and histological grading (p = 0.002 and 0.019, respectively).

- Although the Kaplan–Meier survival curves showed no significant association between p‐STAT3 (tyr705) expression and overall survival rate, multivariate Cox regression analysis showed that p‐STAT3 (tyr705) expression was a significant predictor of overall survival for HCC (p = 0.036). Our results indicated that p‐STAT3 (tyr705) expression was significantly correlated with histological grading and intratumour MVD in HCC.

- The potential role of p‐STAT3 (tyr705) in HCC development may be through these correlations.

Most importantly, we found that nuclear p‐STAT3 (tyr705) expression was significantly and positively correlated with intratumour MVD, but not with Ki‐67 expression, in HCC lesions (table 4; p = 0.002). This result points to the possibility that the possible involvement of p‐STAT3 (tyr705) in HCC may be through its association with the angiogenesis, but not the proliferation, of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Many studies have suggested that STAT3 could participate in oncogenesis through upregulation of genes encoding the inducers of angiogenesis, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).9,10,11 Altered STAT3 activation has been demonstrated in enhancing VEGF production and maintaining angiogenic phenotype in primary gastric cancer,33 breast cancer34 and ovarian cancer.35 Because the increased production of either VEGF or MVD has been closely associated with HCC,36,37,38 the positive correlation between an increased p‐STAT3 (tyr705) expression and intratumour MVD in HCC lesions may thus partly contribute to HCC development. However, the Kaplan–Meier survival curve showed no significant difference between the high and low p‐STAT3 (tyr705) expression groups in HCC (data not shown), implicating that the involvement of p‐STAT3 (tyr705) in HCC might be more complex and needs to be further investigated. Notably, p‐STAT3 (tyr705) expression was also a significant predictor for the overall survival of patients with HCC, in addition to gender, tumour grade, intratumour MVD and Ki‐67 expression (table 5).

In conclusion, our finding showed that an increased p‐STAT3 (tyr705) expression in HCC lesions was closely correlated with an increased histological grading and intratumour MVD in HCC. The potential role of p‐STAT3 (tyr705) in HCC needs to be further investigated, but its association with tumour angiogenesis and histological grading may contribute to its role in HCC development, at least in part.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by grants 93‐2314‐B‐037‐089 and 94‐2314‐B‐037‐041 from the National Science Council, ROC.

Abbreviations

HBV - hepatitis B virus

HCV - hepatitis C virus

HCC - hepatocellular carcinoma

MVD - microvessel density

p‐STAT3 (tyr705) - phosphorylated signal transducer and activator of transcription protein 3 at tyrosine residue 705

VEGF - vascular endothelial growth factor

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.El‐Serag H B. Hepatocellular carcinoma: an epidemiologic view. J Clin Gastroenterol 200235S72–S78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee W C, Jeng L B, Chen M F. Hepatectomy for hepatitis B‐, hepatitis C‐, and dual hepatitis B‐ and C‐related hepatocellular carcinoma in Taiwan. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 20007265–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gao B. Cytokines, STATs and liver disease. Cell Mol Immunol 2005292–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taub R. Hepatoprotection via the IL‐6/Stat3 pathway. J Clin Invest 2003112978–980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berclaz G, Altermatt H J, Rohrbach V.et al EGFR dependent expression of Stat3 (but not STAT1) in breast cancer. Int J Oncol 2001191155–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernandes A, Hamburger A W, Gerwin B I. Erb‐2 kinase is required for constitutive stat 3 activation in malignant human lung epithelial cells. Int J Cancer 199983564–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell C L, Jiang Z, Savarese D M.et al Increased expression of the interleukin‐11 receptor and evidence of Stat3 activation in prostate carcinoma. Am J Pathol 200115825–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang M, Page C, Reynolds R K.et al Constitutive activation of stat3 oncogene product in human ovarian carcinoma cells. Gynecol Oncol 20007967–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Niu G, Bowman T, Huang M.et al Roles of activated Src and Stat3 signaling in melanoma tumor cell growth. Oncogene 2002217001–7010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wei D, Le X, Zheng L.et al Stat3 activation regulates the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and human pancreatic cancer angiogenesis and metastasis. Oncogene 200322319–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haura E B, Turkson J, Jove R. Mechanisms of disease: insights into the emerging role of signal transducers and activators of transcription in cancer. Nat Clin Pract Oncol 20052315–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Calo V, Migliavacca M, Bazan V.et al STAT proteins: from normal control of cellular events to tumorigenesis. J Cell Physiol 2003197157–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Waris G, Huh K W, Siddiqui A. Mitochondrially associated hepatitis B virus X protein constitutively activates transcription factors STAT‐3 and NF‐kappa B via oxidative stress. Mol Cell Biol 2001217721–7730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Waris G, Siddiqui A. Regulatory mechanisms of viral hepatitis B and C. J Biosci 200328311–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoshida T, Hanada T, Tokuhisa T.et al Activation of STAT3 by the hepatitis C virus core protein leads to cellular transformation. J Exp Med 2002196641–653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gong G, Waris G, Tanveer R.et al Human hepatitis C virus NS5A protein alters intracellular calcium levels, induces oxidative stress, and activates STAT‐3 and NF‐kappa B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2001989599–9604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arbuthnot P, Capovilla A, Kew M. Putative role of hepatitis B virus X protein in hepatocarcinogenesis: effects on apoptosis, DNA repair, mitogen‐activated protein kinase and JAK/STAT pathways. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 200015357–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sarcar B, Ghosh A K, Steele R.et al Hepatitis C virus NS5A mediated STAT3 activation requires co‐operation of Jak1 kinase. Virology 200432251–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sanchez A, Nagy P, Thorgeirsson S S. STAT‐3 activity in chemically‐induced hepatocellular carcinoma. Eur J Cancer 2003392093–2098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cressman D E, Diamond R H, Taub R. Rapid activation of the Stat3 transcription complex in liver regeneration. Hepatology 1995211443–1449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cressman D E, Greenbaum L E, DeAngelis R A.et al Liver failure and defective hepatocyte regeneration in interleukin‐6‐deficient mice. Science 19962741379–1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klein C, Wustefeld T, Assmus U.et al The IL‐6‐gp130‐STAT3 pathway in hepatocytes triggers liver protection in T cell‐mediated liver injury. J Clin Invest 2005115860–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inoue H, Ogawa W, Ozaki M.et al Role of STAT‐3 in regulation of hepatic gluconeogenic genes and carbohydrate metabolism in vivo. Nat Med 200410168–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Streetz K L, Tacke F, Leifeld L.et al Interleukin 6/gp130‐dependent pathways are protective during chronic liver diseases. Hepatology 200338218–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li W, Liang X, Kellendonk C.et al STAT3 contributes to the mitogenic response of hepatocytes during liver regeneration. J Biol Chem 200227728411–28417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hamilton S R, Aaltonen L A. WHO classification of tumours. Pathology and genetics. tumours of the digestive system. In: Hirohashi S, Ishak KG, Kojiro M, et al, eds, Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lyon: IARC 2000159–180.

- 27.Scheuer P J, Davies S E, Dhillon A P. Histopathological aspects of viral hepatitis. J Viral Hepat 19963277–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weidner N. Intratumor microvessel density as a prognostic factor in cancer. Am J Pathol 19951479–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feng D Y, Zheng H, Tan Y.et al Effect of phosphorylation of MAPK and Stat3 and expression of c‐fos and c‐jun proteins on hepatocarcinogenesis and their clinical significance. World J Gastroenterol 2001733–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meinhold‐Heerlein I, Bauerschlag D, Hilpert F.et al Molecular and prognostic distinction between serous ovarian carcinomas of varying grade and malignant potential. Oncogene 2005241053–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arany I, Chen S H, Megyesi J K.et al Differentiation‐dependent expression of signal transducers and activators of transcription (STATs) might modify responses to growth factors in the cancers of the head and neck. Cancer Lett 200319983–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suiqing C, Min Z, Lirong C. Overexpression of phosphorylated‐STAT3 correlated with the invasion and metastasis of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. J Dermatol 200532354–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gong W, Wang L, Yao J C.et al Expression of activated signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 predicts expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in and angiogenic phenotype of human gastric cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2005111386–1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hsieh F C, Cheng G, Lin J. Evaluation of potential Stat3‐regulated genes in human breast cancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2005335292–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen H, Ye D, Xie X.et al VEGF, VEGFRs expressions and activated STATs in ovarian epithelial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 200494630–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang G W, Yang L Y, Lu W Q. Expression of hypoxia‐inducible factor 1alpha and vascular endothelial growth factor in hepatocellular carcinoma: impact on neovascularization and survival. World J Gastroenterol 2005111705–1708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sun X Y, Wu Z D, Liao X F.et al Tumor angiogenesis and its clinical significance in pediatric malignant liver tumor. World J Gastroenterol 200511741–743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Imura S, Miyake H, Izumi K.et al Correlation of vascular endothelial cell proliferation with microvessel density and expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Med Invest 200451202–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]