The WD40 protein Caf4p is a component of the mitochondrial fission machinery and recruits Dnm1p to mitochondria (original) (raw)

Abstract

The mitochondrial division machinery regulates mitochondrial dynamics and consists of Fis1p, Mdv1p, and Dnm1p. Mitochondrial division relies on the recruitment of the dynamin-related protein Dnm1p to mitochondria. Dnm1p recruitment depends on the mitochondrial outer membrane protein Fis1p. Mdv1p interacts with Fis1p and Dnm1p, but is thought to act at a late step during fission because Mdv1p is dispensable for Dnm1p localization. We identify the WD40 repeat protein Caf4p as a Fis1p-associated protein that localizes to mitochondria in a Fis1p-dependent manner. Caf4p interacts with each component of the fission apparatus: with Fis1p and Mdv1p through its NH2-terminal half and with Dnm1p through its COOH-terminal WD40 domain. We demonstrate that _mdv1_Δ yeast contain residual mitochondrial fission due to the redundant activity of Caf4p. Moreover, recruitment of Dnm1p to mitochondria is disrupted in _mdv1_Δ _caf4_Δ yeast, demonstrating that Mdv1p and Caf4p are molecular adaptors that recruit Dnm1p to mitochondrial fission sites. Our studies support a revised model for assembly of the mitochondrial fission apparatus.

Introduction

Mitochondria are dynamic organelles that undergo fusion and fission. These processes intermix the mitochondria within cells and control their morphology. In addition to controlling mitochondrial shape, recent studies have also implicated components of the fission machinery in regulation of programmed cell death (Frank et al., 2001; Fannjiang et al., 2004; Jagasia et al., 2005). Genetic approaches in Saccharomyces cerevisiae have identified DNM1, FIS1, and MDV1 as components of the mitochondrial fission pathway (Shaw and Nunnari, 2002). Dnm1p and its mammalian homologue Drp1 are members of the extensively studied dynamin family of large, oligomeric GTPases. Although the precise mechanism remains controversial, dynamins may couple GTP hydrolysis to a conformational constriction that causes membrane scission (Praefcke and McMahon, 2004). In yeast cells, Dnm1p dynamically localizes to dozens of puncta that are primarily associated with mitochondria (Otsuga et al., 1998; Bleazard et al., 1999; Sesaki and Jensen, 1999; Legesse-Miller et al., 2003). A subset of these puncta are sites of future fission.

The assembly of functional Dnm1p complexes on mitochondria is a critical issue in understanding the mechanism of mitochondrial fission. The mitochondrial outer membrane protein Fis1p is required for the formation of normal Dnm1p puncta on mitochondria. In _fis1_Δ cells, Dnm1p puncta are primarily cytosolic or form abnormally large aggregates on mitochondria (Fekkes et al., 2000; Mozdy et al., 2000; Tieu and Nunnari, 2000). Mdv1p interacts with Fis1p through its NH2-terminal half and with Dnm1p through its COOH-terminal WD40 domain. However, Mdv1p appears dispensable for Dnm1p assembly on mitochondria because _mdv1_Δ cells show little or no change in Dnm1p localization, even though mitochondrial fission is disrupted (Fekkes et al., 2000; Tieu and Nunnari, 2000; Tieu et al., 2002; Cerveny and Jensen, 2003). These observations have led to two important features of a recently proposed model for mitochondrial fission (Shaw and Nunnari, 2002; Tieu et al., 2002; Osteryoung and Nunnari, 2003). First, Fis1p acts to assemble and distribute Dnm1p on mitochondria in an Mdv1p-independent step. Second, Mdv1p acts downstream of Dnm1p localization to stimulate membrane scission. An alternative model proposes that Dnm1p marks the site of mitochondrial fission and recruits Fis1p and Mdv1p into an active fission complex (Cerveny and Jensen, 2003). Again, in this model Mdv1p functions downstream of Dnm1p localization.

Despite extensive efforts, however, there is no evidence that Fis1p can interact directly with Dnm1p. We speculated that there may be an additional component of the mitochondrial fission pathway required for the Fis1p-dependent assembly of Dnm1p puncta on mitochondria. Because a genome-wide screen for mitochondrial morphology mutants (Dimmer et al., 2002) did not yield obvious candidates, we used a biochemical approach to identify additional components of the mitochondrial fission machinery. Using immunopurification and mass spectrometry, we have identified the WD40 repeat protein Caf4p as a Fis1p-interacting protein. Caf4p localizes to mitochondria and associates with Fis1p, Mdv1p, and Dnm1p. Moreover, we show that _mdv1_Δ cells are only partially deficient in mitochondrial fission due to the redundant activity of Caf4p. Importantly, Caf4p mediates recruitment of Dnm1p puncta to mitochondria in _mdv1_Δ yeast. Inclusion of CAF4 significantly clarifies the current models for mitochondrial fission.

Results

Caf4p is associated with Fis1p

To identify Fis1p-associated proteins by multidimensional protein identification technology (MudPIT) (Link et al., 1999; Graumann et al., 2004), we constructed a yeast strain containing endogenous Fis1p with an NH2-terminal tandem affinity tag (Fig. 1 A). NH2-terminal tagging is necessary because FIS1 is nonfunctional when COOH-terminally tagged (unpublished data). We first designed a recombination cassette containing 9XMyc/TEV/URA3/TEV/His8 modules (Fig. 1 A). After targeted integration into the FIS1 locus, spontaneous and precise recombination between the flanking ∼50-bp tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease sites excises URA3. This strategy was used to generate a yeast strain (DCY1557) that expresses a functional Fis1p with an NH2-terminal 9XMyc/TEV/His8 tag (M9TH-Fis1p) from the endogenous locus.

Figure 1.

Construction of M 9 TH-FIS1 and Caf4p/Mdv1p alignment. (A) A 9xMyc-TEV-_URA3_-TEV-His8 cassette was PCR amplified with _FIS1_-targeting primers and integrated in-frame into the NH2 terminus of FIS1. Pop-out of the URA3 cassette by recombination between flanking TEV sites yielded M9TH-FIS1 under the control of the endogenous FIS1 promoter. UTR: untranslated region. (B) Schematic of Mdv1p and Caf4p. The NH2-terminal extension (NTE), coiled-coil, and WD40 regions are shown with percent identity. Overall identity is 37% and overall similarity is 57%.

Tandem affinity-purified M9TH-Fis1p was subjected to MudPIT analysis in two independent experiments (see Materials and methods). Fis1p was identified in both experiments (61.3% coverage, 14 unique peptides; 58.7% coverage, 9 unique peptides). Mdv1p, a previously identified member of the mitochondrial fission pathway and a known Fis1p-interacting protein, was also identified in both experiments (22.1% coverage, 12 unique peptides; 10.2% coverage, 5 unique peptides). These data confirmed that our MudPIT procedure could preserve and identify Fis1p complexes relevant to mitochondrial fission. Dnm1p was not observed in either dataset, in agreement with previous immunoprecipitation experiments (Mozdy et al., 2000). The complete datasets are presented in Table S1 (available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200503148/DC1).

Interestingly, peptides derived from the WD40 repeat protein Caf4p were identified in both Fis1p MudPIT experiments (24.4% coverage, 9 unique peptides; 8.5% coverage, 3 unique peptides). CAF4 (YKR036C) was first identified in a yeast two-hybrid screen for CCR4p-interacting proteins (Liu et al., 2001). CCR4p is a central component of the CCR4-NOT transcriptional regulator and cytosolic deadenylase complex (Denis and Chen, 2003). Caf4p is the nearest homologue of Mdv1p in S. cerevisiae (38% identity and 57% similarity), and the two proteins show extensive sequence identity throughout their lengths (Fig. 1 B). Both proteins share a unique NH2-terminal extension (NTE) (25.3% identity), a central coiled-coil (CC) domain (19% identity) and a COOH-terminal WD40 repeat domain (44.4% identity). The Caf4p CC scores significantly more weakly (∼0.3 probability) than the Mdv1p coiled coil (∼1.0 probability) in the MultiCoil prediction program (Wolf et al., 1997).

Caf4p interacts with components of the mitochondrial fission machinery

We sought independent confirmation of the physical interaction between Fis1p and Caf4p. For immunoprecipitation experiments, Caf4p-HA or Mdv1p-HA were expressed from their endogenous promoters in strains carrying chromosomal M3TH-FIS1 (3XMyc/TEV/His8-FIS1) and deleted for CAF4 or MDV1, respectively. When M3TH-Fis1p was immunoprecipitated, ∼5% of both Caf4p-HA and Mdv1p-HA coprecipitated (Fig. 2 A, lanes 7 and 10).

Figure 2.

Caf4p and Mdv1p coimmunoprecipitation experiments. (A) Yeast carrying the indicated HA- and Myc-tagged constructs were lysed and immunoprecipitated with an anti-Myc antibody. Total lysates (labeled “Lysate”) and immunoprecipitated samples (labeled “Myc IP”) were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Myc (9E10) and anti-HA (12CA5) antibodies as indicated. The expression constructs were: Caf4p wt (residues 1–659), Caf4p N (residues 1–274), Caf4p C (residues 275–659), Mdv1 wt (residues 1–714), Mdv1p N (residues 1–300), and Mdv1p C (residues 301–714). The yeast backgrounds were: (A) wild-type, lanes 1–6; _caf4_Δ M3TH-FIS1, lanes 7–9; _mdv1_Δ M3TH-FIS1, lanes 10–12; (B) wild-type, lanes 1–6; _caf4_Δ _MDV1_-HTM, lanes 7–9; _mdv1_Δ _CAF4_-HTM, lanes 10–12; _CAF4_-HTM, lanes 13–15; _MDV1_-HTM, lanes 16–18. (B) Yeast carrying the indicated HA- and Myc-tagged constructs were immunoprecipitated and analyzed as in A. Immunoprecipitated samples were loaded at 10 (A) and 20 (B) equivalents of the lysate samples. HA-tagged proteins in the lysate are marked with an asterisk. The HA-tagged Caf4p C polypeptide co-migrates with a background band in the total lysate blot probed with HA antibody.

Previous yeast two-hybrid analysis determined that the NTE/CC region of Mdv1p (residues 1–300) is responsible for its interaction with Fis1p (Tieu et al., 2002). We detected the same interaction by coimmunoprecipitation (Fig. 2 A, lane 11). Additionally, we found that the analogous region of Caf4p (residues 1–274) also interacted with Fis1p (Fig. 2 A, lane 8). A shorter Caf4p fragment lacking the majority of the predicted coiled coil (residues 1–250) interacted equally well with Fis1p (unpublished data). In contrast, Fis1p did not bind to the COOH-terminal regions of either Mdv1p or Caf4p (Fig. 2 A, lanes 9 and 12). These data suggest that both Caf4p and Mdv1p likely interact with Fis1p through a common mechanism involving the NTE domain.

We also used a yeast two-hybrid assay to analyze the interaction of Caf4p and Mdv1p with Fis1p and Dnm1p (Table I). Full-length Caf4p and an NTE/CC fragment of Caf4p interacted strongly with the cytosolic portion of Fis1p (residues 1–128), consistent with our immunoprecipitation data. Similar interactions were observed between Fis1p and both full-length Mdv1p and the NTE/CC region of Mdv1p, as has been previously reported (Tieu et al., 2002; Cerveny and Jensen, 2003). The WD40 domain of both Mdv1p and Caf4p interacted strongly with Dnm1p. However, full-length Mdv1p interacted more weakly and an interaction between full-length Caf4p and Dnm1p was not detected. These results suggest that the interaction of the WD40 domain with Dnm1p is regulated and may be inhibited by the NH2-terminal region of Caf4p and Mdv1p.

Table I. Caf4p and Mdv1p interact with Dnm1p and Fis1p in a yeast two-hybrid assay.

| Caf4p | Mdv1p | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fis1p | Dnm1p | wt | N | C | wt | N | C | ||

| Fis1p | − | − | + | + | − | + | + | − | |

| Dnm1p | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| Caf4p | wt | + | − | − | − | − | − | weak | − |

| N | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| C | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | |

| Mdv1p | wt | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | − |

| N | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | − | |

| C | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

We also detected homotypic and heterotypic interactions between Caf4p and Mdv1p. Approximately 5% of Caf4p-HA and Caf4p-N-HA (residues 1–274), but not Caf4-C-HA (residues 275–659), coimmunoprecipitate with full-length Caf4p-HTM (Fig. 2 B, lanes 13–15). A similar level of Mdv1p-HA and Mdv1p-N-HA (residues 1–300), but not Mdv1-C-HA (residues 301–714), coimmunoprecipitated with Mdv1p-HTM (Fig. 2 B, lanes 16–18). When Caf4p-HTM was precipitated, ∼1% of Mdv1p-HA and Mdv1p-N-HA, but not Mdv1p-C-HA, coprecipitated (Fig. 2 B, lanes 10–12). Similarly, when Mdv1p-HTM was precipitated, ∼1% of Caf4p-HA and Caf4p-N-HA, but not Caf4p-C-HA, coprecipitated (Fig. 2 B, lanes 7–9). Moreover, the NTE/CC regions of Caf4p and Mdv1p interact in the two-hybrid assay (Table I). Therefore, Caf4p interacts with all three members of the fission pathway, with the NH2-terminal region mediating interactions with Fis1p, Mdv1p, and homotypic interactions with Caf4p.

Caf4p is involved in mitochondrial division

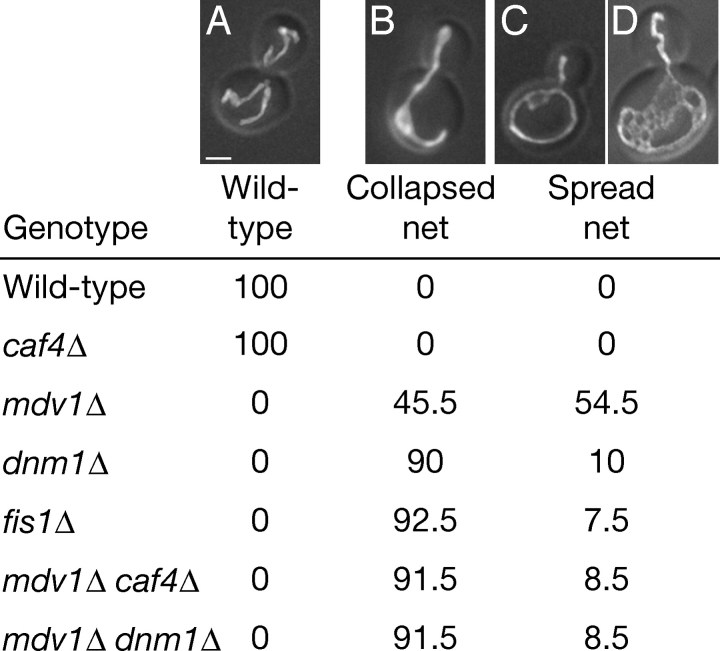

Given that Caf4p interacts with Fis1p, Mdv1p, and Dnm1p, we hypothesized that Caf4p, like Mdv1p, is a component of the mitochondrial division apparatus. _caf4_Δ yeast, however, display normal mitochondrial morphology, with tubular mitochondria evenly dispersed around the cell cortex (Fig. 3). Wild-type mitochondrial morphology was also observed at elevated temperatures and on carbon sources other than dextrose (glycerol or galactose; unpublished data). This observation is not surprising, given that CAF4 was not identified in a genome-wide screen of deletion strains for mitochondrial morphology mutants (Dimmer et al., 2002).

Figure 3.

CAF4 regulates mitochondrial morphology. Strains expressing mitochondrially targeted GFP were grown in YP dextrose to mid-log phase and fixed. The percentage of cells (n = 400) with mitochondria having wild-type (A), collapsed net (B), or spread net morphology (C and D) is tabulated. The spread net phenotype encompasses a distribution of morphologies ranging from simple structures containing one or two loops (C) to complexly fenestrated mitochondria with dozens of loops (D). For both wild-type and _caf4_Δ strains, the wild-type category includes 1% fragmented cells. Bar, 1 μm.

We next tested whether _caf4_Δ cells show synthetic defects in mitochondrial morphology when other components of the fission machinery are deleted. Yeast defective in mitochondrial fission display net-like mitochondrial morphology due to unopposed mitochondrial fusion (Bleazard et al., 1999; Sesaki and Jensen, 1999). These mitochondrial nets can have a spread morphology (Fig. 3, C and D), or they can collapse to one side of the cell (Fig. 3 B). Although FIS1, DNM1, and MDV1 are all involved in mitochondrial fission, we found that _mdv1_Δ cells have a distribution of mitochondrial profiles that can be readily distinguished from both _fis1_Δ and _dnm1_Δ cells (Fig. 3). In rich dextrose medium, almost all _fis1_Δ or _dnm1_Δ cells (93 and 90%, respectively) contain collapsed mitochondrial nets. In contrast, less than half of _mdv1_Δ cells contain collapsed nets, with the majority displaying a spread net morphology. The spread nets range in morphology from interconnected tubules with several loops (Fig. 3 C) to networks with complex fenestrations (Fig. 3 D). _mdv1_Δ _dnm1_Δ cells behave identically to _dnm1_Δ cells, with >90% collapsed nets in dextrose (Fig. 3). This observation indicates that the _dnm1_Δ collapsed net phenotype is epistatic to the _mdv1_Δ spread net phenotype. In rich galactose medium (unpublished data), a greater portion of all strains contain spread nets, but again _mdv1_Δ cells have a higher percentage of cells with spread nets (80%) compared with _fis1_Δ (45.5%), _dnm1_Δ (53%), or _mdv1_Δ_dnm1_Δ cells (40.5%). These results agree with a previous report that _mdv1_Δ cells have more spread nets compared with _dnm1_Δ cells in galactose medium (Cerveny et al., 2001). However, this study found that the _mdv1_Δ spread net phenotype is epistatic to the _dnm1_Δ collapsed net phenotype (Cerveny et al., 2001). The reason for this discrepancy is unclear, but we note the _mdv1_Δ morphology is most distinct in dextrose cultures.

Most interestingly, we found that _mdv1_Δ _caf4_Δ cells have mitochondrial net distributions indistinguishable from either _dnm1_Δ cells or _fis1_Δ cells. Deletion of CAF4 in _mdv1_Δ cells markedly shifts the distribution to one composed almost entirely of collapsed mitochondrial nets (>90% in dextrose, Fig. 3). Our results support a model in which partial reduction of mitochondrial fission results in predominantly spread mitochondrial nets, and complete loss of fission eventually results in collapse of the nets. That is, _mdv1_Δ cells retain residual mitochondrial fission, whereas _mdv1_Δ _caf4_Δ cells are devoid of fission, similar to _dnm1_Δ, _fis1_Δ, or _mdv1_Δ _dnm1_Δ cells. An analogous situation appears to exist in mammalian cells, in which weak Drp1 dominant-negative alleles cause the formation of spread nets, whereas strong dominant-negative alleles cause nets to collapse (Smirnova et al., 2001).

We tested this model by reanalyzing mitochondrial morphologies in the presence of latrunculin A, which disrupts the actin cytoskeleton. Disruption of the actin cytoskeleton leads to rapid fragmentation of the mitochondrial network due to ongoing mitochondrial fission (Boldogh et al., 1998; Jensen et al., 2000). Latrunculin A treatment rapidly resolves a fraction of collapsed nets into spread nets (Jensen et al., 2000; Cerveny et al., 2001), and allows a closer examination of the degree of connectivity in mitochondrial nets. Similarly, in mammalian cells, collapsed mitochondrial nets induced by overexpression of dominant-negative Drp1 can be spread by the microtubule-depolymerizing agent nocodazole (Smirnova et al., 2001). Both wild-type and _caf4_Δ yeast treated with latrunculin A show mitochondrial fragmentation (Fig. 4). 80% of _mdv1_Δ cells treated with latrunculin A contain partial mitochondrial nets (Fig. 4 E, partial net) that are less interconnected and have fewer fenestrations than the collapsed or spread nets that predominate in latrunculin A–treated _dnm1_Δ or _fis1_Δ cells. 95% of latrunculin A–treated _mdv1_Δ _caf4_Δ cells show either collapsed nets or highly fenestrated spread nets, a profile indistinguishable from that in _dnm1_Δ or _fis1_Δ cells (Fig. 4). Thus, after disruption of the actin cytoskeleton, _mdv1_Δ yeast display a distribution of mitochondrial morphologies that suggest an incomplete defect in mitochondrial fission. In contrast, _mdv1_Δ _caf4_Δ yeast have mitochondrial morphologies similar to that in _fis1_Δ and _dnm1_Δ yeast. We conclude that CAF4 mediates low levels of mitochondrial fission in _mdv1_Δ cells.

Figure 4.

CAF4 mediates residual fission in mdv1 Δ cells. Top: mid-log cultures grown in YP dextrose were treated for 60 min with 200 μM latrunculin A (+) or vehicle (−). For each strain, 200 cells were scored into the following phenotypic categories: wild-type (A), fragments and short tubules (B), collapsed net (C), spread net (D), or partial net (E). Numbers shown are percentages. The fragments and short tubules category encompasses a range of morphologies from completely fragmented (as shown in B) to a mixture of fragments and short tubules. (F–H) Still images from time-lapse movies showing fission events in _mdv1_Δ yeast treated with 200 μM latrunculin A. The boxed area in the first frame is magnified in the subsequent sequence of five images. Arrows indicate fission events. Mitochondria were visualized with the outer membrane marker OM45-GFP. Bars, 1 μm.

We next monitored the mitochondrial network in _mdv1_Δ cells by time-lapse microscopy to assess the levels of mitochondrial fission. In pilot experiments, we found that free mitochondrial ends produced by fission events in _mdv1_Δ cells were rapidly involved in fusion events, making unambiguous documentation of fission difficult. Because latrunculin A reduces the levels of fusion and thereby should prolong the presence of free mitochondrial ends, we monitored mitochondrial dynamics in latrunculin A–treated _mdv1_Δ cells carrying the outer membrane marker OM45-GFP. In 8 out of 10 _mdv1_Δ cells, we observed at least one fission event in a 30-min recording period (Fig. 4, F–H; Videos 1 and 2, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200503148/DC1). Due to the complexity and rapid rearrangements of the mitochondrial networks in these cells (see Videos 1 and 2), these numbers likely underestimate the actual levels of fission. In contrast, no fission events were observed in 8 _mdv1_Δ _caf4_Δ cells. We conclude that the ability of CAF4 to mediate mitochondrial fission events contributes significantly to the spread net morphology of _mdv1_Δ cells.

Mitochondrial fission is blocked by overexpression of Caf4p or Caf4p fragments

Because overexpression of Mdv1p or Mdv1p fragments inhibits mitochondrial fission (Cerveny and Jensen, 2003), we next tested the effects of Caf4p overproduction. Caf4p-HA under the control of the GalL promoter was expressed ∼20 times above endogenous levels in rich galactose medium (unpublished data). Spread mitochondrial nets formed in 23.5% of cells (Fig. 5 C). An additional 38% of cells had an intermediate phenotype that we termed “connected tubules,” consisting of a completely interconnected mitochondrial network in which no tubular ends were detected (Fig. 5 B). Overexpression of an NH2-terminal fragment that interacts with Fis1p (residues 1–250; unpublished data) had a similar effect (9% spread nets, 33% connected tubules; Fig. 5), suggesting that the formation of mitochondrial net-like structures may result from a dominant-negative effect on Fis1p function. A similar distribution of mitochondrial phenotypes resulted from 20-fold overproduction of Mdv1p-HA (7.5% spread nets and 24.5% interconnected tubules) and an Mdv1p-HA NH2-terminal fragment (5% spread nets and 39% interconnected tubules; unpublished data). These data confirm that Caf4p interacts with the mitochondrial fission apparatus.

Figure 5.

Caf4p overexpression blocks mitochondrial fission. Wild-type yeast (DCY1979) carrying the pRS416 GalL vector with no insert, full-length CAF4-HA, CAF4-HA N, or CAF4-HA C were grown in rich dextrose or galactose media for 180 min and fixed. Cells were scored into the following phenotypic categories: wild-type (A), connected tubules (B), or spread nets with tubules (C). Numbers shown are percentages (n = 200). Overexpression in galactose cultures was estimated to result in 20-fold greater expression than endogenous levels by Western blots of serially diluted lysates (not depicted). Bar, 1 μm.

Full bypass suppression of _fzo1_Δ requires loss of both MDV1 and CAF4

Yeast fission mutants are able to suppress the glycerol growth defect of cells deficient in mitochondrial fusion (Bleazard et al., 1999). Indeed, MDV1 was originally identified because of its ability to suppress the glycerol growth defect of strains carrying temperature-sensitive fzo1 or mgm1 alleles (Fekkes et al., 2000; Mozdy et al., 2000; Tieu and Nunnari, 2000; Cerveny et al., 2001). Deletion of MDV1 has previously been reported to suppress the glycerol growth defect of _fzo1_Δ cells less efficiently than deletion of DNM1 (Cerveny et al., 2001). To further test our hypothesis that _mdv1_Δ cells have only a partial loss of mitochondrial fission, we compared the efficiencies with which the _mdv1_Δ and _dnm1_Δ mutations suppress the glycerol growth defect of _fzo1_Δ cells. Diploids were sporulated, genotyped, and scored by serial dilution for their ability to grow on glycerol plates relative to dextrose plates (Fig. 6). As expected, all wild-type and no _fzo1_Δ spores grew on glycerol plates. Of 17 _mdv1_Δ _fzo1_Δ spores tested, 7 showed no detectable growth on glycerol and an additional 4 spores grew very poorly, with <1% cell survival on glycerol. Only 3 of the 6 remaining spores showed >20% survival on glycerol. More than half of _dnm1_Δ _fzo1_Δ spores grew robustly on glycerol plates, with between 20 and 50% cell survival. Most importantly, the triple mutant _mdv1_Δ _caf4_Δ _fzo1_Δ spores grew much more robustly than the _mdv1_Δ _fzo1_Δ spores, with all spores growing on glycerol and the majority between 20 and 50% cell survival. The markedly enhanced bypass suppression of _fzo1_Δ by _mdv1_Δ _caf4_Δ double mutations compared with the _mdv1_Δ mutation provides genetic evidence that _mdv1_Δ cells retain residual mitochondrial fission due to the activity of Caf4p.

Figure 6.

Suppression of the glycerol growth defect of fzo1 Δ cells. Individual spores of the indicated genotypes were assayed by serial dilution on YP glycerol and YP dextrose plates to determine the percent survival on glycerol-containing medium. Each point represents the viability of an individual spore. For clarity, spores showing 1% or less survival were plotted as 1%.

Caf4p localizes to mitochondria in a Fis1p-dependent manner

We next sought to determine the subcellular localization of Caf4p. Caf4p was detected in highly purified mitochondrial preparations (Sickmann et al., 2003), and a Caf4p-GFP fusion generated in a genome-wide analysis localizes to mitochondria (Huh et al., 2003). We confirmed the mitochondrial localization of Caf4p-GFP, but did not study it further because the GFP fusion protein was not functional when expressed from the CAF4 locus (unpublished data). We instead used immunofluorescence to localize Myc-tagged versions of Caf4p and Mdv1p (termed Caf4p-HTM and Mdv1p-HTM) that are expressed from the endogenous locus and are functional. Caf4p-HTM and Mdv1p-HTM showed clear mitochondrial localization (Fig. 7). When cells were grown in rich dextrose medium, both Caf4p-HTM and Mdv1p-HTM displayed a largely uniform mitochondrial distribution with occasional areas of increased intensity. In rich galactose medium, Caf4p-HTM and Mdv1p-HTM localize in a more punctate pattern on mitochondria (Fig. 7, M–R). Caf4p-HTM partially colocalizes with Dnm1-GFP puncta (Fig. 7, S–U). In _fis1_Δ cells grown in either dextrose or galactose media, both Caf4p-HTM and Mdv1p-HTM are found predominantly in the cytosol (Fig. 7, D–F and J–L). In some cells, however, low levels of residual localization to mitochondria could be discerned (e.g., Fig. 7, D–F). In fis1 mutant yeast, overexpressed GFP-Mdv1p is diffusely cytosolic but also retains some localization to mitochondria (Tieu and Nunnari, 2000; Tieu et al., 2002). Together, these data indicate that the normal mitochondrial localization of both Caf4p and Mdv1p depends largely on Fis1p, although some low levels of residual localization can occur in the absence of Fis1p.

Figure 7.

Mitochondrial localization of Caf4p and Mdv1p requires Fis1p. Immunofluorescence (red, middle panels) was used to localize Myc-tagged Caf4p (Caf4p-HTM; A–-F and M–U) and Mdv1p (Mdv1p-HTM; G–L and P–R) in wild-type (A–C, G–I, and M–U) and fis1Δ cells (D–F and J–L). Caf4p-HTM and Mdv1p-HTM are expressed from the endogenous loci and are functional. Mitochondria were labeled with mitochondrially targeted GFP (A–R, left, green). The majority of Dnm1p-GFP puncta colocalize with Caf4p-HTM (S–U). Overlays of the two signals are shown in the merged images (right). Note that both Caf4p and Mdv1p localize to mitochondria in wild-type cells, but are diffusely cytosolic in fis1Δ cells. Cells were grown in YP dextrose (A–L) or YP galactose (M–U). Representative maximum intensity projections of deconvolved z-stacks are shown. Bar, 1 μm. (V) Caf4p-HTM and Mdv1p-HTM were analyzed by subcellular fractionation. The total cell lysate (Total), high-speed supernatant (Cyto), and mitochondrial pellet (Mito) were analyzed by Western blot with an anti-Myc antibody in wild-type (left) and fis1Δ (right) yeast. PGK (3-phosphoglycerate kinase) is a cytosolic marker, and porin is a mitochondrial outer membrane marker.

We also evaluated the localization of Caf4p-HTM by subcellular fractionation. We found a significant portion of both Caf4p and Mdv1p in the mitochondrial pellet (Fig. 7 V). Mdv1p had previously been shown to be present in mitochondrial fractions (Fekkes et al., 2000; Tieu and Nunnari, 2000; Cerveny et al., 2001). However, in _fis1_Δ yeast both proteins behave as cytosolic proteins (Fig. 7 V). These data support our immunofluorescence studies and confirm that Mdv1p and Caf4p localize to mitochondria through their association with Fis1p.

Caf4p recruits Dnm1p-GFP to mitochondria

To understand the mechanism of mitochondrial fission, it is crucial to elucidate how Dnm1p is recruited to mitochondria. Given that Mdv1p associates with both Fis1p and Dnm1p, it is puzzling that Dnm1p assembly on mitochondria shows little or no dependence on Mdv1p (Fekkes et al., 2000; Mozdy et al., 2000; Tieu and Nunnari, 2000; Tieu et al., 2002; Cerveny and Jensen, 2003). With the identification of Caf4p as a component of the fission machinery, we reexamined this issue. We constructed a fully functional Dnm1p-GFP allele and analyzed its localization pattern using deconvolution microscopy (Table II). Similar to previous reports (Otsuga et al., 1998), Dnm1p-GFP is found predominantly in puncta associated with mitochondria (average 16.9 mitochondrial vs. 3.3 cytosolic puncta per cell) (Table II and Fig. 8, A–C). Deletion of CAF4 or MDV1 alone had little effect on this localization (15.4 mitochondrial vs. 5.2 cytosolic and 13.7 mitochondrial vs. 5.1 cytosolic per cell, respectively; Table II and Fig. 8, D–I). In all these strains, the Dnm1p puncta are relatively uniform in size and intensity.

Table II. Quantification of Dnm1-GFP puncta localization.

| Mitochondrial | Cytosolic | |

|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | 16.9 (± 5.5) | 3.3 (± 2.1) |

| _caf4_Δ | 15.4 (± 5.2) | 5.2 (± 2.6) |

| _mdv1_Δ | 13.7 (± 5.0) | 5.1 (± 3.0) |

| _fis1_Δ | 4.9 (± 2.7) | 9.6 (± 4.3) |

| _mdv1_Δ _caf4_Δ | 4.8 (± 2.5) | 10.4 (± 3.9) |

Figure 8.

Fis1p mediates Dnm1p-GFP localization through either Mdv1p or Caf4p. The localization of Dnm1p-GFP (middle, green) was compared to mito-DsRed (left, red) in yeast of the indicated genotype. Merged images are shown on the right. Representative maximum intensity projections of deconvolved z-stacks are shown.

In contrast, _fis1_Δ mutants showed dramatic defects, with the majority of the puncta now cytosolic (4.9 mitochondrial vs. 9.6 cytosolic) (Table II and Fig. 8, J–L). As has been previously noted, a small fraction of Dnm1p still localizes to mitochondria in _fis1_Δ cells (Tieu et al., 2002; Cerveny and Jensen, 2003), suggesting that Dnm1p may be recruited by a second pathway, perhaps through an intrinsic affinity for mitochondrial lipids or an unidentified mitochondrial binding partner. Importantly, a similar defect in Dnm1p localization was found in _mdv1_Δ _caf4_Δ cells (4.8 mitochondrial vs. 10.4 cytosolic per cell) (Table II and Fig. 8, M–O). In both _fis1_Δ and _mdv1_Δ _caf4_Δ cells, Dnm1p-GFP forms a few large aggregates and numerous less intense puncta. Similar results were obtained using immunofluorescence against a Dnm1p-HTM protein (unpublished data). These data clearly demonstrate that either Caf4p or Mdv1p is sufficient for effective recruitment of Dnm1p to mitochondria, and that Caf4p is essential for Mdv1p-independent recruitment of Dnm1p by Fis1p.

Discussion

CAF4 and MDV1 perform similar functions in mitochondrial fission

By applying affinity purification and mass spectrometry to Fis1p, we have identified Caf4p as a novel component of the mitochondrial fission machinery. Our biochemical and genetic characterization indicate that CAF4 functions in the same manner as MDV1 in mitochondrial fission. Biochemically, both proteins interact with Fis1p and Dnm1p. Caf4p and Mdv1p share a common domain architecture comprised of an NTE, a central CC, and a COOH-terminal WD40 repeat. The NH2-terminal regions mediate oligomerization and association with Fis1p, whereas the COOH-terminal WD40 regions mediate interactions with Dnm1p. In addition, both Caf4p and Mdv1p localize to mitochondria in a Fis1p-dependent manner.

Genetically, both MDV1 and CAF4 act positively in the mitochondrial fission pathway. _mdv1_Δ cells are dramatically compromised for mitochondrial fission, but a residual level of fission is mediated by CAF4. This residual fission activity is revealed by the observation that _mdv1_Δ yeast have a less severe mitochondrial morphology defect compared with _fis1_Δ or _dnm1_Δ yeast. In contrast, _mdv1_Δ _caf4_Δ yeast display predominantly collapsed mitochondrial nets, identical to those seen in _fis1_Δ and _dnm1_Δ cells. Time-lapse imaging of mitochondria in _mdv1_Δ cells indeed reveals a residual level of fission that is absent from _mdv1_Δ _caf4_Δ cells. These results directly support our conclusion that the morphology differences between _mdv1_Δ cells versus _mdv1_Δ _caf4_Δ, _fis1_Δ, and _dnm1_Δ cells are primarily due to differences in fission rates. It is also possible that the proposed role of Dnm1p in cortical distribution of mitochondria may contribute in part to the morphological differences (Otsuga et al., 1998). The _mdv1_Δ mutation acts as a weak suppressor of the glycerol growth defect in _fzo1_Δ cells. The _mdv1_Δ _caf4_Δ double mutation suppresses this phenotype much more efficiently. Based on these physical interaction and genetic data, we conclude that Caf4p likely acts in a similar manner to Mdv1p to promote mitochondrial fission.

Why are there two proteins that appear to perform similar and partially redundant roles in mitochondrial fission? This question is particularly intriguing because _caf4_Δ yeast have normal mitochondrial morphology, indicating that disruption of Caf4p does not cause a major loss of mitochondrial fission. First, CAF4 may play a more important role in mitochondrial fission under conditions not yet tested. Second, the presence of two proteins mediating interactions between Fis1p and Dnm1p would increase the ability of cells to accurately regulate the rate of mitochondrial fission. The heterotypic and homotypic interactions between Caf4p and Mdv1p may provide an additional layer of regulation. Finally, Caf4p may have an additional function in another pathway. Previous two-hybrid studies have implicated Caf4p in the CCR4-NOT complex, which is thought to be involved in regulation of transcription and/or mRNA processing (Liu et al., 2001).

A revised model for mitochondrial fission

The current models for mitochondrial fission propose that Mdv1p acts late in the fission pathway. One model proposes a two-step pathway in which Fis1p first recruits Dnm1p, in an Mdv1p-independent manner. Mdv1p then acts as a molecular adaptor at a post-recruitment step, along with Fis1p, to promote fission by Dnm1p (Shaw and Nunnari, 2002; Tieu et al., 2002; Osteryoung and Nunnari, 2003). A second model also proposes that Mdv1p acts after Dnm1p recruitment to organize an active fission complex (Cerveny and Jensen, 2003).

Our study reveals a new role for Mdv1p and Caf4p early in mitochondrial fission. Fis1p recruits Dnm1p to mitochondrial fission complexes through Mdv1p or Caf4p, which act as molecular adaptors. This revised model is strongly supported by our demonstration that Dnm1p recruitment in _mdv1_Δ yeast depends on Caf4p function. In the absence of both Mdv1p and Caf4p, Fis1p is unable to recruit Dnm1p.

Although Mdv1p and Caf4p clearly act early in the fission pathway, there is evidence that at least Mdv1p has a subsequent role in the activation of fission, as previously proposed (Shaw and Nunnari, 2002; Tieu et al., 2002; Cerveny and Jensen, 2003). In _caf4_Δ cells, Mdv1p recruits Dnm1p to fission complexes, and fission occurs at apparently normal levels. However, in _mdv1_Δ cells, Caf4p is similarly able to recruit Dnm1p to fission complexes, but mitochondrial fission is severely compromised. Therefore, Mdv1p and Caf4p can independently recruit Dnm1p, but complexes recruited by Mdv1p appear to be more highly active. These observations suggest that Dnm1p recruitment by itself is insufficient for fission to occur. Indeed, studies of Dnm1p dynamics indicates that most Dnm1p puncta do not result in fission (Legesse-Miller et al., 2003). Our identification of Caf4p as part of the fission machinery clarifies the early steps in mitochondrial fission. Future studies will need to define the additional steps beyond Dnm1p recruitment necessary for fission.

Materials and methods

Media and yeast genetic techniques

Yeast strains are listed in Table S1. Standard genetic techniques and yeast media were used. SC and YP media supplemented with either 2% dextrose, 3% glycerol, 2% raffinose, or 2% galactose were prepared as described previously (Guthrie and Fink, 1991). YJG12 and DCY1557 are in the w303 background. All other strains are in the S288C background. fis1::KanMX6, mdv1::KanMX6, caf4::KanMX6, and dnm1::KanMX6 are derived from the MATa deletion library (Open Biosystems).

Plasmid construction

The M9TH cassette was generated as follows. Primers Eg258 (see Table S3, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200503148/DC1) and Eg259 were used to amplify URA3 from pRS416 (Stratagene). Eg260 and Eg4, an FZO1 reverse primer, were used to amplify a TEV/His8 module from EG704 (pRS414 + 9XMyc/TEV/His8-FZO1). The 3′ end of the URA3 product overlaps by 18 bp with the 5′ end of the TEV/His8 product. This overlap allows them to anneal together and be amplified in a second PCR with the primers Eg258 and Eg4. The URA3/TEV/His8 product was cloned into pRS403 as an EcoRV/SalI fragment (which removes all FZO1 sequence), resulting in EG928. 9xMyc/TEV was amplified with Eg256 and Eg260 from EG704 and fused to the 5′ end of URA3 (Eg258/259 product) by mixing and amplifying with Eg256 and Eg259. The resulting product was cloned into EG928 as an EcoRV/EcoRI fragment, yielding EG940 (pRS403+9xMyc/TEV/URA3/TEV/His8). EG940 was converted to pRS403+3xMyc/TEV/URA3/TEV/His8 by digesting with Xba1, yielding EG957.

To construct HA-tagged versions of CAF4 and CAF4 fragments, CAF4 sequences were PCR amplified from _end3_Δ genomic DNA (Open Biosystems). First, the CAF4 3′ untranslated region (UTR) was amplified with the primers Eg313 and Eg314 and cloned as a KpnI/SalI fragment into pRS416, resulting in pRS416 + CAF4 3′ UTR. 3XHA was amplified with Eg327 and Eg328 and cloned as a SalI/XhoI fragment into the SalI site to generate pRS416 + 3XHA/CAF4 3′ UTR. The CAF4 5′ UTR was cloned as a SacI/SpeI fragment using Eg312 and Eg317, resulting in pRS416 + CAF4 5′ UTR/3XHA/3′ UTR. Full-length CAF4 was amplified with Eg316 and Eg315 and cloned as a SpeI/XhoI fragment into the SpeI/SalI sites, resulting in EG1041. CAF4 N (residues 1–274) and C (residues 275–659) were amplified with Eg316/Eg353 and Eg315/Eg352, respectively, and cloned as SpeI/XhoI fragments, resulting in EG1045 and EG1043. Four independent clones encoded glutamine at residue 110 and arginine at residue 111. Full-length CAF4-HA was able to complement _caf4_Δ in _caf4_Δ _mdv1_Δ yeast, indicating that it is functional.

To construct HA-tagged versions of MDV1 and MDV1 fragments, MDV1 sequences were amplified by PCR from _end3_Δ genomic DNA. First, the MDV1 3′ UTR was amplified with the primers Eg323 and Eg324 and cloned as a SacI/SalI fragment into pRS416. A 3XHA cassette was added as described for CAF4-HA, resulting in the plasmid pRS416 + 3XHA-MDV1 3′ UTR. The MDV1 5′ UTR was amplified with primers Eg320 and Eg322 and cloned as a SacII/SpeI fragment, resulting in pRS416 + MDV1 5′ UTR/3XHA/3′ UTR. Full-length MDV1 was amplified using primers Eg109 and Eg321 and cloned as a SpeI/XhoI fragment into the SpeI/SalI sites, resulting in EG1047. MDV1 N (residues 1–300) and C (residues 301–714) were amplified with Eg323/Eg326 and Eg321/325, respectively, and cloned as SpeI/XhoI fragments, resulting in EG1051 and EG1049. Full-length _MDV1_-HA complemented the mitochondrial morphology defects in _mdv1_Δ cells.

The galactose-inducible Caf4p expression vectors EG1133 (Caf4p-HA), EG1135 (Caf4p-HA, residues 251–659), and EG1136 (Caf4p-HA, residues 1–250) were generated by replacing the CAF4 5′ UTR in EG1041, EG1043, and EG1045 with a SacI/ClaI GalL promoter fragment from p413 GalL (Mumberg et al., 1994) containing a start codon inserted between the XbaI and EcoRI sites.

pRS403 + GPD/mito-GFP (EG686) was generated by first cloning the GPD promoter from p413 GPD (Mumberg et al., 1995) as a SacI (blunt)/SpeI fragment into the SmaI/SpeI sites of pRS403 (Stratagene), yielding EG128. Next, a HindIII (blunt)/NotI mito-GFP fragment from pYES-mtGFP (Westermann and Neupert, 2000) was inserted into EG128 linearized with SpeI (blunt)/NotI. pRS403 + GPD/mito-DsRed (EG823) was generated by subcloning DsRed into the BamHI and NotI sites of EG686, replacing GFP with DsRed. OM45 was PCR amplified with primers Eg151 and Eg154 and cloned as an XhoI/XbaI fragment with an XbaI/BamHI GFP fragment into the XhoI/BamHI sites of pRS416, yielding pRS416 + OM45-GFP (EG252).

Yeast strain construction

An M9TH-FIS1 strain was generated by amplifying the 9XMyc/TEV/URA3/TEV/His8 cassette from EG943 (pRS403-9XMyc/TEV/URA3/TEV/His8) with the _FIS1_-targeting primers Eg261 and Eg262 and transforming YJG12. _URA3_+ transformants were screened by PCR for correct integration (2 out of 8 positive), grown overnight in YPD to allow for loss of URA3, and plated on 5-FOA plates. Colonies were screened by Western blotting for expression of M9TH-Fis1p (9 out of 16 positive). This strain displayed wild-type morphology in 64% of cells and moderate defects in the remaining cells. The same strategy was used to generate M3TH-FIS1 from the pRS403-3XMyc/TEV/URA3/TEV/His8 template (EG957) for subsequent experiments in the S288C background. This strain (DCY2192) displayed wild-type morphology in 89% of cells and mild defects in the remaining cells. DCY2192 was crossed to _mdv1_Δ and _caf4_Δ strains (Open Biosystems MATa deletion library) and sporulated to generate M3TH-_FIS1 mdv1_Δ (DCY2302) and M3TH_-FIS1 caf4_Δ (DCY2305).

fzo1::HIS5 was generated by transformation with a HIS5 (Saccharomyces kluyveri) fragment amplified with the FZO1 targeting primers Eg9 and Eg10. mito-GFP was integrated to the leu2_Δ_0 locus by transformation with NarI-digested EG686 (pRS403 + GPD/mito-GFP). mito-DsRed was integrated to the leu2_Δ_0 locus by transformation with HpaI-digested EG823 (pRS403 + GPD/mito-DsRed). dnm1_Δ::HIS5_ was generated by transformation with a HIS5 (S. kluyveri) fragment amplified with the _DNM1_-targeting primers Eg57 and Eg58.

Chromosomal _CAF4_-HTM was generated by transformation of DCY1979 with a His8/2TEV/9XMyc/HIS5 cassette (Seol et al., 1999) amplified with the CAF4 targeting primers Eg284 and Eg285. Chromosomal _MDV1_-HTM was generated transformation with the same cassette amplified with MDV1 targeting primers Eg80 and Eg81. Both _CAF4-_HTM and _MDV1_-HTM are functional because 70% of _CAF4_-HTM _mdv1_Δ yeast display spread mitochondrial nets and 95% of _MDV1_-HTM yeast cells display wild-type mitochondrial morphology.

_DNM1_-GFP was generated by amplifying GFP/HIS5 from pKT128 (Sheff and Thorn, 2004) with Eg342 and Eg343. This product was transformed into DCY1626 (wild-type yeast with mito-DsRed) to generate DCY2370. DCY2370 was crossed to _fis1_Δ and _mdv1_Δ _caf4_Δ strains to generate DCY2404 (_DNM1_-GFP _fis1_Δ), DCY2414 (_DNM1-_GFP _caf4_Δ), DCY2417 (_DNM1_-GFP _mdv1_Δ), and DCY2418 (_DNM1_-GFP _mdv1_Δ _caf4_Δ).

Tandem affinity purification MudPIT

Pellets from 2-l cultures (OD600 ∼1.5) grown in YPD were prepared essentially as described previously for HPM tag Dual-Step affinity purification (Graumann et al., 2004), with the following modifications. Fungal protease inhibitors were used (Sigma-Aldrich) and lysates were cleared at 20 k_g_ for 15 min. Cleavage from 9E10 beads was performed with GST-TEV protease for 3 h at RT. The second affinity step was performed with 40 μl Magne-His beads (Promega). Samples were proteolytically digested and analyzed by multidimensional chromatography in-line with a Deca XP ion trap mass spectrometer (ThermoElectron) as described previously (Mayor et al., 2005). Samples were released stepwise from the strong cation exchanger phase of the triphasic capillary columns as reported previously (Graumann et al., 2004).

Immunoprecipitation

_CAF4_-HA (EG1041), _CAF4_-HA residues 1–274 (EG1043), and _CAF4_-HA residues 275–659 (EG1045) were expressed in strains DCY1979 (wild-type) and DCY2305 (M3TH-_FIS1 caf4_Δ). _MDV1-_HA (EG1047), _MDV1_-HA residues 1–300 (EG1049), and _MDV1_-HA residues 301–714 (EG1051) were expressed in DCY1979 or DCY2302 (M3TH_-FIS1 mdv1_Δ). Cultures were grown in selective SD media and harvested at OD600 ∼0.8. 20 OD600 units of cells were lysed with glass beads (40 s with a vortex mixer, 4 times) in 500 μl ice-cold lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 0.2% Triton X-100) in the presence of Fungal protease inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich). Lysates were cleared by centrifuging 5 min at 5 krpm and 15 min at 14 krpm. At this point, a total lysate sample was taken. 400 μl of cleared lysate was mixed with a 20-μl bead volume of 9E10-conjugated protein A–Sepharose beads (Sigma-Aldrich) for 90 min. Beads were washed four times with 1-ml washes of lysis buffer. Precipitate was eluted with 100 μl SDS buffer at 95°C for 5 min. SDS-PAGE Western blotting was performed with 9E10 hybridoma supernatant (anti-Myc) or 12CA5 ascites fluid (anti-HA).

Yeast two-hybrid assay

pGAD vectors were transformed into PJ69-4α. pGBDU vectors were transformed into PJ69-4a (James et al., 1996). Indicated vectors were mated on YPD plates using two transformants for each vector (totaling four matings per combination). Diploids were selected by replica plating to SD-leu-ura plates. Interactions were assayed by replica plating to SD-leu-ura-lys-ade and incubating for 4 d at 30°C.

Mitochondrial morphology analysis

Mitochondrially targeted GFP (mito-GFP) was used to monitor mitochondrial morphology. DCY1979 (wild-type), DCY1945 (_caf4_Δ), DCY1984 (_caf4_Δ _mdv1_Δ), DCY2009 (_fis1_Δ), DCY2128 (_mdv1_Δ), DCY2155 (_mdv1_Δ _dnm1_Δ), and DCY2312 (_dnm1_Δ) were grown overnight, diluted 1:20 into fresh medium, and grown for 4 h at 30°C. Cultures were fixed by adjusting cultures to 3.7% formaldehyde and incubated 10 min at 30°C. Cells were washed 4 times with 1 ml PBS and scored for mitochondrial morphology. For CAF4 overexpression studies, plasmids p416 GalL/_CAF4_-HA (EG1133), p416 GalL/_CAF4_-HA residues 251–659 (EG1135), or p416 GalL/_CAF4_-HA residues 1–250 (EG1137) were transformed into DCY1979. Cultures were grown overnight in selective SRaff and diluted 1:20 in fresh YPD or YPGal and grown 3 h at 30°C. Samples were taken for Western analysis and the remaining culture was fixed as described above.

For latrunculin A treatment, overnight YPD cultures were diluted 1:20 in fresh YPD and grown for 3 h. Cultures were then treated for 1 h at 30°C with 200 μM latrunculin A in or with an equivalent amount of vehicle (DMSO). Cultures were then fixed as described above.

For time-lapse imaging, overnight SGal cultures were diluted 1:20 in fresh YPGal and grown for 3 h. Cells were pelleted, resuspended in fresh media, and embedded in 1% low melting point agarose containing 200 μM latrunculin A.

Bypass suppression assay

DCY2002 and DCY2343 were sporulated and dissected onto YPD plates. Spores were picked, grown overnight in 3 ml YPD at 30°C, pelleted, and resuspended to OD600 ∼1.0 in YP. 3 μl of 1:5 serial dilutions were spotted on YPD and YPGlycerol and grown at 30°C for 2 and 4 d, respectively, to determine the fraction of cells that grow on glycerol. Genotypes were determined by PCR.

Differential centrifugation

Yeast strains _CAF4_-HTM (DCY2055), _CAF4_-HTM _fis1_Δ (DCY2094), _MDV1_-HTM (DCY2053), and _MDV1_-HTM _fis1_Δ (DCY2097) were grown in YPD and harvested at OD600 ∼1.2. 100 OD units of cells were spheroplasted with zymolyase and lysed in a small clearance Dounce homogenizer (0.6 M sorbitol and 10 mM Tris, pH 7.4). The lysate was spun twice at 2.9 krpm for 5 min. An aliquot of the second supernatant was saved as the total lysate sample. The second supernatant was spun at 10 krpm for 10 min, and an aliquot of the supernatant was saved as the cytosol sample. The pellet was resuspended and spun again at 10 krpm for 10 min. An aliquot of the final pellet was saved as the mitochondrial pellet. Equal cell equivalents were loaded for Western blot analysis. The difference in porin intensity between the total and mitochondrial fractions most likely results from fewer obscuring proteins in the mitochondrial fraction.

Imaging

Images were acquired on a microscope (Axiovert 200M; Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Inc.) using a 100× Plan-Apochromat, NA 1.4, oil-immersion objective. Z-stack images (between 0.1- and 0.2-μm intervals for still images and between 0.3- and 0.4-μm intervals for time-lapse images) were collected at RT with an ORCA-ER camera (Hamamatsu), controlled by AxioVision 4.2 software. Images were collected at either 30- or 40-s intervals for 30 min for time-lapse experiments. Iterative deconvolutions were performed with Axiovision 4.2 and maximum intensity projections were generated with AxioVision 4.2 for still images and Image J for time-lapse images. Fluorescent images in Figs. 3–5 were overlaid with differential interference contrast images (set at 50% opacity) in Adobe Photoshop CS.

Immunofluorescence

Cells were processed for immunofluorescence essentially as described previously (Guthrie and Fink, 1991) with the following modifications. Cultures were fixed for 15 min with 3.7% formaldehyde. Tween 20 (0.5%) was included in blocking buffer (PBS, 1% BSA) during a 15-min block step. Cells were stained with 9E10 hybridoma supernatant and a Cy3-conjugated anti–mouse secondary antibody. Washes after primary and secondary incubations were 5 min with blocking buffer, 5 min with blocking buffer containing 0.5% Tween 20, and two 5-min washes with blocking buffer. All incubations were performed at RT. GelMount (Biomeda) was used as mounting medium to preserve fluorescence.

Online supplemental material

Table S1 lists proteins identified in MudPIT experiments with M9TH-Fis1p. Table S2 shows yeast strains. Table S3 lists primer sequences. Videos 1 and 2 show mitochondrial fission in _mdv1_Δ yeast. Mitochondria were monitored by the mitochondrial outer membrane marker OM45-GFP. Arrows highlight a subset of fission events. Online supplemental material available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200503148/DC1.

Acknowledgments

We thank T.R. Suntoke, S.A. Detmer, and H. Chen for helpful comments on the manuscript; and L. Lytle for technical assistance. J. Copeland constructed some of the two-hybrid plasmids. We thank Dr. Ray Deshaies for stimulating discussions on mass spectrometry.

E.E. Griffin was supported by a National Institutes of Health training grant (NIH GM07616) and a Ferguson fellowship. MudPIT analysis was performed in the mass spectrometry facility of the laboratory of R.J. Deshaies (Investigator, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Caltech). This facility is supported by the Beckman Institute at Caltech and by a grant from the Department of Energy to R.J. Deshaies and B.J. Wold. J. Graumann is supported by R.J. Deshaies through Howard Hughes Medical Institute funds. D.C. Chan is a Bren Scholar and Beckman Young Investigator. This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (GM62967).

Abbreviations used in this paper: CC, coiled coil; MudPIT, multidimensional protein identification technology; NTE, NH2-terminal extension; TEV, tobacco etch virus; UTR, untranslated region.

References

- Bleazard, W., J.M. McCaffery, E.J. King, S. Bale, A. Mozdy, Q. Tieu, J. Nunnari, and J.M. Shaw. 1999. The dynamin-related GTPase Dnm1 regulates mitochondrial fission in yeast. Nat. Cell Biol. 1:298–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boldogh, I., N. Vojtov, S. Karmon, and L.A. Pon. 1998. Interaction between mitochondria and the actin cytoskeleton in budding yeast requires two integral mitochondrial outer membrane proteins, Mmm1p and Mdm10p. J. Cell Biol. 141:1371–1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerveny, K.L., and R.E. Jensen. 2003. The WD-repeats of Net2p interact with Dnm1p and Fis1p to regulate division of mitochondria. Mol. Biol. Cell. 14:4126–4139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerveny, K.L., J.M. McCaffery, and R.E. Jensen. 2001. Division of mitochondria requires a novel DMN1-interacting protein, Net2p. Mol. Biol. Cell. 12:309–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denis, C.L., and J. Chen. 2003. The CCR4-NOT complex plays diverse roles in mRNA metabolism. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 73:221–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimmer, K.S., S. Fritz, F. Fuchs, M. Messerschmitt, N. Weinbach, W. Neupert, and B. Westermann. 2002. Genetic basis of mitochondrial function and morphology in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell. 13:847–853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fannjiang, Y., W.-C. Cheng, S.J. Lee, B. Qi, J. Pevsner, J.M. McCaffery, R.B. Hill, G. Basanez, and J.M. Hardwick. 2004. Mitochondrial fission proteins regulate programmed cell death in yeast. Genes Dev. 18:2785–2797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fekkes, P., K.A. Shepard, and M.P. Yaffe. 2000. Gag3p, an outer membrane protein required for fission of mitochondrial tubules. J. Cell Biol. 151:333–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank, S., B. Gaume, E.S. Bergmann-Leitner, W.W. Leitner, E.G. Robert, F. Catez, C.L. Smith, and R.J. Youle. 2001. The role of dynamin-related protein 1, a mediator of mitochondrial fission, in apoptosis. Dev. Cell. 1:515–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graumann, J., L.A. Dunipace, J.H. Seol, W.H. McDonald, J.R. Yates III, B.J. Wold, and R.J. Deshaies. 2004. Applicability of tandem affinity purification MudPIT to pathway proteomics in yeast. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 3:226–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie, C., and G. Fink. 1991. Guide to Yeast Genetics and Molecular Biology. Academic Press, San Diego, CA. 933 pp.

- Huh, W.K., J.V. Falvo, L.C. Gerke, A.S. Carroll, R.W. Howson, J.S. Weissman, and E.K. O'Shea. 2003. Global analysis of protein localization in budding yeast. Nature. 425:686–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagasia, R., P. Grote, B. Westermann, and B. Conradt. 2005. DRP-1-mediated mitochondrial fragmentation during EGL-1-induced cell death in C. elegans. Nature. 433:754–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James, P., J. Halladay, and E.A. Craig. 1996. Genomic libraries and a host strain designed for highly efficient two-hybrid selection in yeast. Genetics. 144:1425–1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, R.E., A.E. Hobbs, K.L. Cerveny, and H. Sesaki. 2000. Yeast mitochondrial dynamics: fusion, division, segregation, and shape. Microsc. Res. Tech. 51:573–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legesse-Miller, A., R.H. Massol, and T. Kirchhausen. 2003. Constriction and Dnm1p recruitment are distinct processes in mitochondrial fission. Mol. Biol. Cell. 14:1953–1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link, A.J., J. Eng, D.M. Schieltz, E. Carmack, G.J. Mize, D.R. Morris, B.M. Garvik, and J.R. Yates III. 1999. Direct analysis of protein complexes using mass spectrometry. Nat. Biotechnol. 17:676–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.Y., Y.C. Chiang, J. Pan, J. Chen, C. Salvadore, D.C. Audino, V. Badarinarayana, V. Palaniswamy, B. Anderson, and C.L. Denis. 2001. Characterization of CAF4 and CAF16 reveals a functional connection between the CCR4-NOT complex and a subset of SRB proteins of the RNA polymerase II holoenzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 276:7541–7548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayor, T., J.R. Lipford, J. Graumann, G.T. Smith, and R.J. Deshaies. 2005. Analysis of polyubiquitin conjugates reveals that the rpn10 substrate receptor contributes to the turnover of multiple proteasome targets. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 4:741–751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozdy, A.D., J.M. McCaffery, and J.M. Shaw. 2000. Dnm1p GTPase-mediated mitochondrial fission is a multi-step process requiring the novel integral membrane component Fis1p. J. Cell Biol. 151:367–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumberg, D., R. Muller, and M. Funk. 1994. Regulatable promoters of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: comparison of transcriptional activity and their use for heterologous expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 22:5767–5768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumberg, D., R. Muller, and M. Funk. 1995. Yeast vectors for the controlled expression of heterologous proteins in different genetic backgrounds. Gene. 156:119–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osteryoung, K.W., and J. Nunnari. 2003. The division of endosymbiotic organelles. Science. 302:1698–1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsuga, D., B.R. Keegan, E. Brisch, J.W. Thatcher, G.J. Hermann, W. Bleazard, and J.M. Shaw. 1998. The dynamin-related GTPase, Dnm1p, controls mitochondrial morphology in yeast. J. Cell Biol. 143:333–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Praefcke, G.J., and H.T. McMahon. 2004. The dynamin superfamily: universal membrane tubulation and fission molecules? Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5:133–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seol, J.H., R.M. Feldman, W. Zachariae, A. Shevchenko, C.C. Correll, S. Lyapina, Y. Chi, M. Galova, J. Claypool, S. Sandmeyer, et al. 1999. Cdc53/cullin and the essential Hrt1 RING-H2 subunit of SCF define a ubiquitin ligase module that activates the E2 enzyme Cdc34. Genes Dev. 13:1614–1626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sesaki, H., and R.E. Jensen. 1999. Division versus fusion: Dnm1p and Fzo1p antagonistically regulate mitochondrial shape. J. Cell Biol. 147:699–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, J.M., and J. Nunnari. 2002. Mitochondrial dynamics and division in budding yeast. Trends Cell Biol. 12:178–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheff, M.A., and K.S. Thorn. 2004. Optimized cassettes for fluorescent protein tagging in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 21:661–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sickmann, A., J. Reinders, Y. Wagner, C. Joppich, R. Zahedi, H.E. Meyer, B. Schonfisch, I. Perschil, A. Chacinska, B. Guiard, et al. 2003. The proteome of Saccharomyces cerevisiae mitochondria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 100:13207–13212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smirnova, E., L. Griparic, D.L. Shurland, and A.M. van der Bliek. 2001. Dynamin-related protein Drp1 is required for mitochondrial division in mammalian cells. Mol. Biol. Cell. 12:2245–2256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tieu, Q., and J. Nunnari. 2000. Mdv1p is a WD repeat protein that interacts with the dynamin-related GTPase, Dnm1p, to trigger mitochondrial division. J. Cell Biol. 151:353–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tieu, Q., V. Okreglak, K. Naylor, and J. Nunnari. 2002. The WD repeat protein, Mdv1p, functions as a molecular adaptor by interacting with Dnm1p and Fis1p during mitochondrial fission. J. Cell Biol. 158:445–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermann, B., and W. Neupert. 2000. Mitochondria-targeted green fluorescent proteins: convenient tools for the study of organelle biogenesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 16:1421–1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, E., P.S. Kim, and B. Berger. 1997. MultiCoil: a program for predicting two- and three-stranded coiled coils. Protein Sci. 6:1179–1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]