In vivo fate analysis reveals the multipotent and self-renewal capacities of Sox2+ neural stem cells in the adult hippocampus (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2008 Dec 15.

Published in final edited form as: Cell Stem Cell. 2007 Dec 15;1(5):515–528. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.09.002

Summary

To characterize the properties of adult neural stem cells (NSCs), we generated and analyzed _Sox2_-GFP transgenic mice. _Sox2_-GFP cells in the subgranular zone (SGZ) express markers specific for progenitors, but they represent two morphologically distinct populations that differ in proliferation levels. Lentivirus- and retrovirus-mediated fate tracing studies showed that Sox2+ cells in the SGZ have potential to give rise to neurons and astrocytes, revealing their multipotency at the population as well as a single cell level. More interestingly, a subpopulation of Sox2+ cells gives rise to cells that retain Sox2, highlighting Sox2+ cells as a primary source for adult NSCs. In response to mitotic signals, increased proliferation of Sox2+ cells is coupled with the generation of Sox2+ NSCs as well as neuronal precursors. An asymmetric contribution of Sox2+ NSCs may play an important role in maintaining the constant size of the NSC pool and producing newly born neurons during adult neurogenesis.

Introduction

Neural stem cells (NSCs) are defined as cells that can self-renew (the capacity to proliferate to produce identical cells) and are multipotent (the potential to give rise to the major neural lineages, including neurons, astrocytes and/or oligodendrocytes) (Gage, 2000). During embryogenesis, NSCs are located in the ventricular zone of the neural tube, and they can give rise to all cell types needed for the formation of the central nervous system (CNS). Contrary to the earlier belief that neurogenesis occurs only during development, it has been shown that new neurons are continuously born from NSCs throughout adulthood (Kuhn et al., 1996; Lois and Alvarez-Buylla, 1993). This adult neurogenesis occurs in two restricted brain regions: the subgranular zone (SGZ) of the hippocampal dentate gyrus and the subventricular zone (SVZ) of the lateral ventricles.

The terms “self-renewal” and “multipotency” of adult NSCs have been broadly defined, based primarily upon the characterization of in vitro cultured NSCs (Reynolds and Weiss, 1992). Cells that had been prepared from the neurogenic zones or isolated prospectively by virtue of cell surface markers or GFP-expression driven by NSC-specific promoters were plated in the presence of growth factors and examined to determine whether they could expand to form neurospheres or mono-layered colonies (Kawaguchi et al., 2001; Ray and Gage, 2006; Rietze et al., 2001; Roy et al., 2000). The capacity to form secondary or tertiary neurospheres or attached colonies from the primary clones was defined as self-renewal. The differentiation potential of these cells upon withdrawal of growth factors or administration of inducing factors was used to demonstrate multipotency. However, direct evidence to support the existence of self-renewing and multipotent NSCs in vivo is very limited. Moreover, recent studies have raised the possibility that NSCs established with a systematic exposure to growth factors may not reflect the properties of in vivo NSCs but rather display acquired properties that are not evident in vivo (Gabay et al., 2003). Thus, to establish a precise relation between the proliferating cells in the neurogenic zones and the in vitro cultured cells that arise from them, it is essential to understand the properties of in vivo NSCs.

Sox2 is a SRY-related transcription factor encoding a high mobility group (HMG) DNA biding motif, and it is expressed in embryonic stem (ES) cells and neural epithelial cell during development (Avilion et al., 2003; Ferri et al., 2004; Zappone et al., 2000). Although genetic examination and analysis of in vitro cultured cells have implicated Sox2+ cells as NSCs (Bylund et al., 2003; Ferri et al., 2004; Graham et al., 2003), no direct in vivo data have demonstrated their self-renewal and multipotency in the adult brain.

Here, we hypothesized that Sox2+ cells represent NSCs in the adult hippocampus and tested whether they retain the multipotent and self-renewing properties at a single cell level. By using transgenic mice in which a GFP reporter gene was expressed under the control of Sox2 promoter (D'Amour and Gage, 2003), we showed that Sox2+ cells represent an undifferentiated, dividing cell population in the SGZ of adult dentate gyrus. Furthermore, our fate mapping and lineage tracing of Sox2+ cells revealed that Sox2+ cells are capable of producing differentiated neural cells as well as identical Sox2+ cells, demonstrating their self-renewing and multipotent NSC properties at a single cell level. We also examined the involvement of Sox2+ NSCs in enhanced neurogenesis, when animals were exposed to mitotic signals. The results provide evidence that increased proliferation of Sox2+ NSCs leads to the generation of neuronal precursors as well as the Sox2+ NSC population, but the size of Sox2+ NSC pool remains unchanged. The contribution of proliferation of the Sox2+ NSCs to the production of differentiated cells in addition to NSCs could be relevant to understanding how the self-renewal of NSCs is coupled with the generation of differentiated cells.

Results

Two morphologically distinct Sox2-GFP populations in the SGZ

We generated transgenic mouse lines harboring enhanced GFP under the control of murine Sox2 promoter (_Sox2_-GFP) and examined whether Sox2 promoter could drive GFP expression in the adult neurogenic zones. GFP-expressing (GFP+) cells were detected in the SGZ of the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus (Figure 1A) and the SVZ of the lateral ventricle (Figure S1) in 6-week-old _Sox2_-GFP mice. In situ hybridization using Sox2 antisense probe confirmed that the GFP expression recapitulated the endogenous Sox2 mRNA expression pattern in the adult brain (Figure 1B). These results show that 5.5kb Sox2 promoter is sufficient to mimic endogenous Sox2 expression and to label cells residing in the adult neurogenic zones. However, it is noteworthy that some GFP+ cells are also distributed throughout the brain, suggesting that Sox2 is expressed more widely in the adult brain than in the embryonic brain (Figure S2, data not shown) (Ferri et al., 2004).

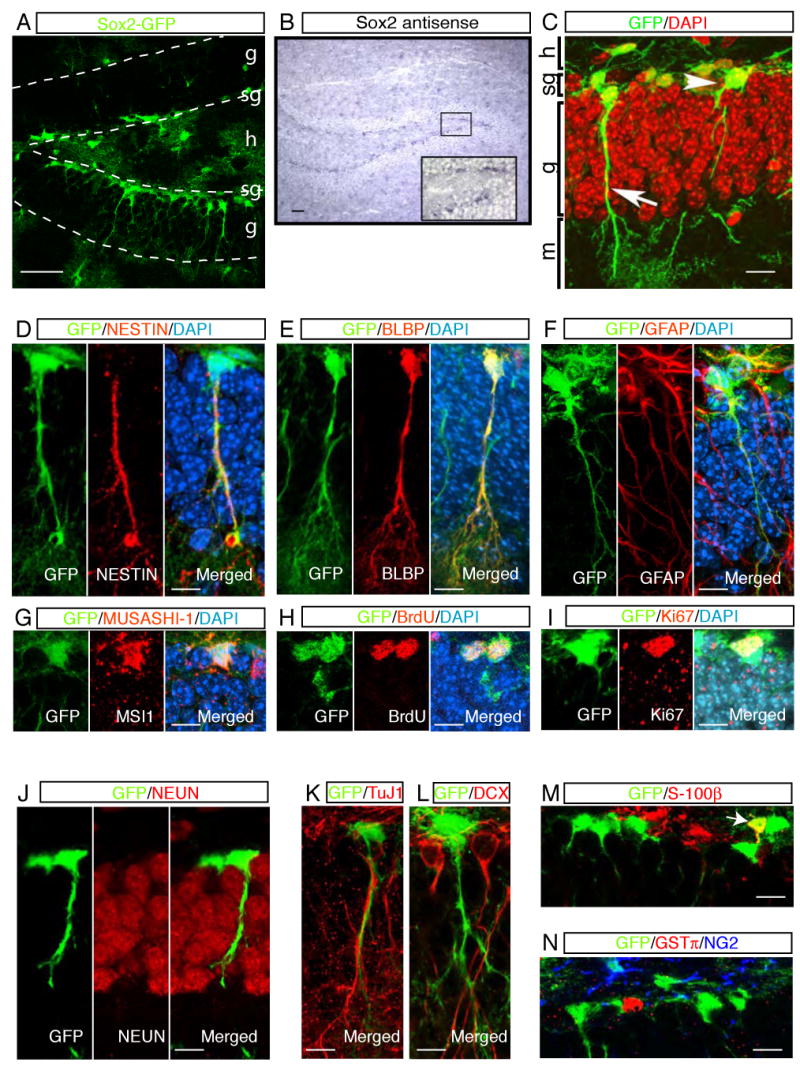

Figure 1. _Sox2_-GFP cells in the SGZ represent dividing and undifferentiated cell populations.

In _Sox2_-GFP transgenic mice, GFP expression in the SGZ (A) faithfully mimicked endogenous Sox2 mRNA in the adult hippocampus (B). A higher magnification view of in situ signal is displayed in the inset (B). Radial (arrow) and non-radial (arrowhead) _Sox2_-GFP cells were found in the SGZ (C). Radial _Sox2_-GFP cells showed co-localization with radial glial cell markers, including NESTIN (D), BLBP (E) and GFAP (F) in their processes. MUSASHI-1 was detected in _Sox2_-GFP cells in soma (G). Some _Sox2_-GFP cells were active in proliferation, displaying BrdU labeling (H) and co-expression with Ki67 (I). The majority of _Sox2_-GFP cells did not express the differentiated neuronal markers, such as NEUN (J), TuJ1 (K), and DCX (L). _Sox2_-GFP cells in the SGZ did not represent differentiated glial cells. Their co-localization with S-100β (M), GST-π, and NG2 (N) was not evident in the SGZ. Some GFP+ cells were co-stained with astrocyte marker, S-100β, in the hilus (M, arrow) or in the deep granular layer. Abbreviations in (A) and (C): g, granular layer; sg, subgranular zone; h, hilus; m, molecular layer. Scale bars: 50 μm (A and B), 10 μm (C to N).

The examination of GFP+ cells by confocal microscopy identified two morphologically distinct cell types in the adult SGZ. One population of GFP+ cells had their cell bodies in the SGZ and displayed a radial glia-like morphology, with a long process across the granular layer of the dentate gyrus (Figure 1C, arrow). This radial morphology is reminiscent of radial glial cells that generate the migrating neurons during embryonic CNS development (Anthony et al., 2004; Malatesta et al., 2003; Miyata et al., 2001; Noctor et al., 2001). In contrast to these radial _Sox2_-GFP cells, the second population of _Sox2_-GFP cells also had their cell bodies in the SGZ but they lacked radial processes. Some of these cells had short processes stretching parallel to the dentate gyrus (Figure 1C, arrowhead).

Sox2-GFP cells represent undifferentiated cell populations in the adult hippocampus

To identify the cell type of GFP+ cells, we first performed immunohistochemistry (IHC) with specific markers for radial glial cells and/or NSCs. _Sox2_-GFP cells co-localized with radial glial cell markers including NESTIN (Fukuda et al., 2003; Kronenberg et al., 2003; Mignone et al., 2004), GFAP(Seri et al., 2004) and BLBP (Anthony et al., 2004), particularly in their radial processes (Figure 1D, 1E and 1F). The examination of NESTIN and GFAP in the non-radial _Sox2_-GFP cells was not feasible, however, due to the lack of signal in the soma. All _Sox2_-GFP cells in the SGZ were co-labeled with MUSASHI-1, which is expressed in postnatal NSCs (Sakakibara and Okano, 1997) (Figure 1G).

IHC with BrdU (Figure 1H, Figure 2S) and Ki67 (Figure 1I) showed that a fraction of _Sox2_-GFP cells was proliferating in the adult SGZ (5.2± 2.67 % of total _Sox2_-GFP cells are positive for Ki67, mean ± s.e.m, n=5) and these cells corresponded to 23% of total Ki67+ cells. It is noteworthy that only non-radial, but not radial, _Sox2_-GFP cells were co-labeled with the cell proliferation markers. Thus, in our analysis, only non-radial _Sox2_-GFP cells are proliferating regularly.

DOUBLECORTIN (DCX), TuJ1, and NEUN were used to examine whether _Sox2_-GFP cells represented neuronal precursors, immature and mature neurons, respectively. Most of the _Sox2_-GFP cells did not co-localize with these markers, indicating that the GFP+ cells in the SGZ do not represent fully differentiated neurons (Figure 1J, 1K and 1L). A few GFP+ cells were co-localized with DCX (data not shown), but this co-localization always coincided with weaker expressions of GFP and DCX. This finding may reflect the transition from Sox2+ cells to immature DCX+ neurons. S-100β, an astrocyte marker, was not expressed in the _Sox2_-GFP cells in the SGZ (Fig. 1M). However, in rare cases, _Sox2_-GFP cells positive for S-100β were found deeper in the granular layer or hilus (Figure1M, arrow). Antisera against NG2 and GST-π were used to examine whether _Sox2_-GFP cells represented oligodendrocytes. However, _Sox2_-GFP cells did not co-localize with these markers (Figure 1N). These data collectively suggest that _Sox2_-GFP cells in the SGZ represent undifferentiated cells with a proliferation capacity, but not differentiated cells.

_Sox2_-GFP cells contain self-renewing, multipotent NSC properties in vitro

To examine whether hippocampal _Sox2_-GFP cells could be a source for in vitro NSCs, hippocampal cells were prepared from the transgenic mice and cultured in the presence of FGF2 and EGF (Figure 2A). When hippocampal cells were initially isolated, only 6% (6.1±2.6%, n=4) of total live cells were GFP+ cells. However, during 4 weeks in culture, _Sox2_-GFP cells expanded and represented approximately 70% of the total live cells (Figure 2A). In independent experiments, GFP+ cells were sorted by FACS directly from the hippocampus and cultured in bulk or clonally. In both cases, GFP+ cells propagated without losing GFP expression (100%, passage 10, 25 and 35, n=3 for each passage), and these in vitro expanded _Sox2_-GFP cells could be passaged at least 30 times, maintaining their capacity to give rise to neural lineages (see below).

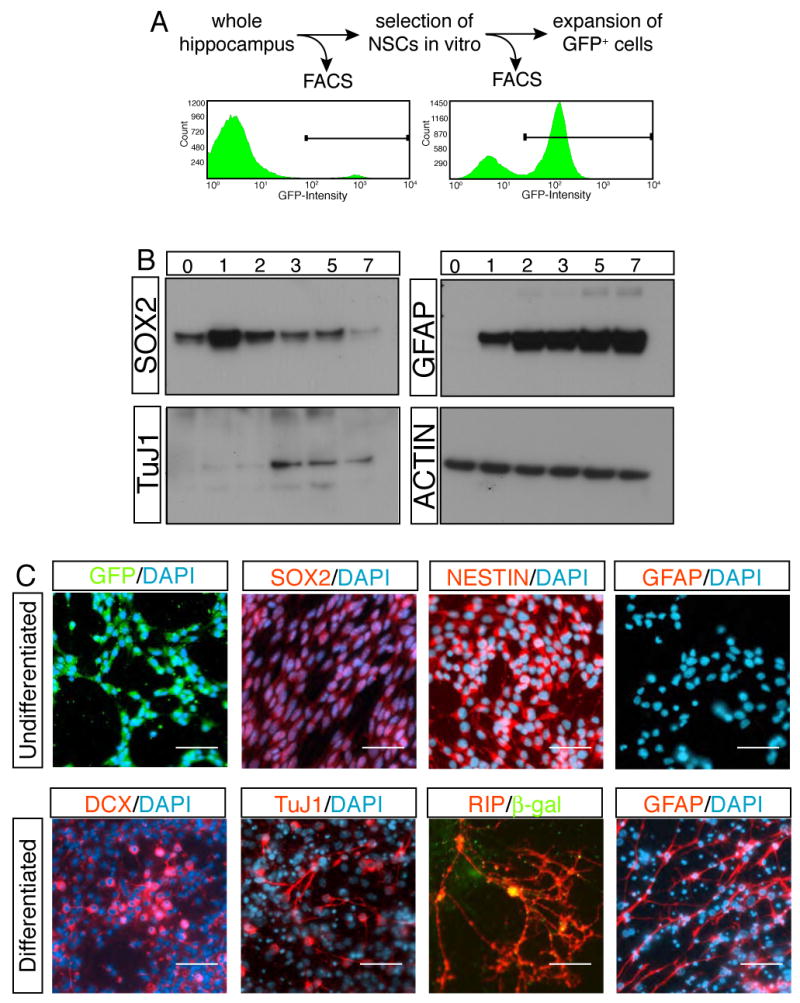

Figure 2. _Sox2_-GFP cells are the origin of in vitro NSCs.

The proliferation capacity of _Sox2_-GFP cells was measured by FACS analysis. _Sox2_-GFP cells, which comprised only 6% of the total hippocampus cells, survived and expanded, forming the majority of colonies in vitro (A). Western analysis showed the progress of differentiation in time course (B). The expressions of neuronal (TuJ1) and glial markers (GFAP) were associated with the down-regulation of SOX2. Immunocytochemistry revealed the differentiation of in vitro cultured _Sox2_-GFP cells to neural lineages (C). Note that co-culture paradigm with primary neurons was used for differentiation of _Sox2_-GFP cells to oligodendrocytes (RIP+ cells). Legends in (B); 0, one day after plating cells but still culturing in FGF2, EGF containing growth medium; 1-7, 1 to 7 days after substituting growth medium with Forskolin-containing differentiation medium. Scale bar: 50 μm.

The multipotency of _Sox2_-GFP cells was examined after they were differentiated into neural lineages. Under the growth condition, almost all _Sox2_-GFP cells expressed the NSC markers, NESTIN and SOX2 (Figure 2C), whereas differentiated neural cell-specific markers were not detected (Figure 2C, data not shown). In the presence of forskolin, _Sox2_-GFP cells differentiated into neurons positive for TuJ1, MAP2 (Figure 2C, data not shown) and DCX and into astrocytes positive for GFAP (Figure 2C). Oligodendrocyte differentiation was achieved by co-culture of _Sox2_-GFP cells with hippocampal neurons from P0 (postnatal day 0) rats (Song et al., 2002). _Sox2_-GFP cells were labeled with lentivirus carrying CMV-βgal reporter to distinguish them from the primary culture. Indeed, some βgal+ cells differentiated into RIP+ oligodendrocytes (Figure 2C), demonstrating that _Sox2_-GFP cells have the potential to give rise to all three major neural lineages.

The temporal progress of the differentiation of _Sox2_-GFP cells was monitored by Western blot. Consistent with immunostaining results, GFAP and TUJ1 were not expressed in the undifferentiated _Sox2_-GFP cells (Figure 2B). Upon differentiation, GFAP expression was immediately induced, followed by TuJ1 expression (Figure 2B). Interestingly, down-regulation of SOX2 coincided with TuJ1 induction but was not associated with initial GFAP expression (Bani-Yaghoub et al., 2006) (Figure 2B).

Sox2+ cells can give rise to neurons, astrocytes and Sox2+ cells in the SGZ

To trace the fate of Sox2+ cells in vivo, _Sox2_-Cre/GFP lentivirus was injected into the dentate gyrus of ROSA26-loxP-Stop-loxP-GFP reporter mice (Figure 3A) (Tashiro et al., 2006). The detailed information regarding the design of the lentiviral vector and the confirmation of viral specificity is described in the supplementary results (Figure 3S). The BrdU paradigm was also used to 1) follow only the daughter cells of targeted Sox2+ cells and 2) rule out the tracing fates of off-targeted, non-dividing neurons (Supplementary results, Figure 3S).

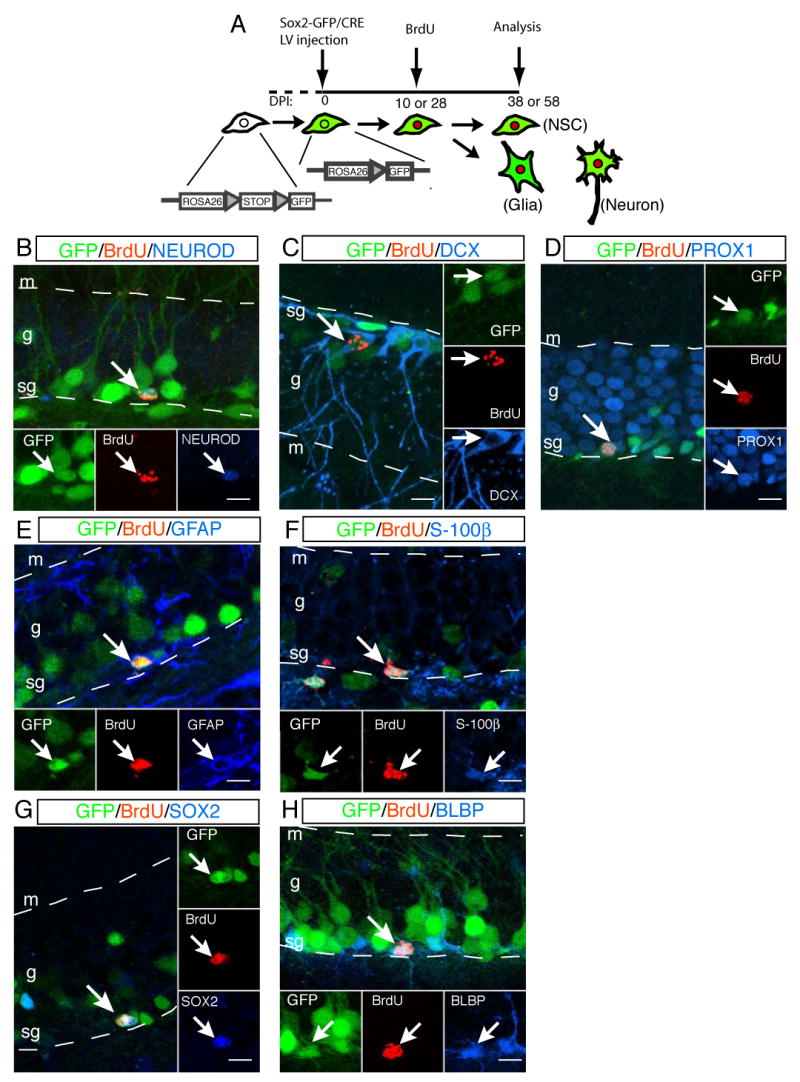

Figure 3. Sox2+ cells proliferate to produce differentiated neural lineages as well as undifferentiated cells.

A fate mapping is schematized in (A). Lentivirus containing _Sox2_-GFP/CRE was injected into the dentate gyrus of ROSA26-loxP-Stop-loxP-GFP reporter mice. Transduction of CRE recombinase deleted “STOP” codon to activate GFP-reporter expression (colored in green) in Sox2+ cells. The recombination in the genomic level allowed tracing of both targeted cells and their progeny. Ten or 28 days after virus injection, BrdU (colored in red) was administered to label newly born cells from the targeted cells (A). One month after BrdU injection, the fate of progeny was examined with cell-type specific markers. Sox2+ cells underwent cell proliferation and gave rise to neuronal precursors positive for NEUROD (B) or DCX (C) as well as PROX1+ granular neurons (D). GFAP+ (E) or S-100β+ (F) glial cells were also generated from Sox2+ cells. Sox2+ cells also have the potential to give rise to undifferentiated cells positive for SOX2 (G) or BLBP (H). Abbreviations: s, subgranular zone; g, granular layer; m, molecular layer. Scale bar: 10 μm.

The fate of the daughter cells of Sox2+ cells was examined with cell-type specific markers. Triple IHC clearly demonstrated that targeted Sox2+ cells (GFP+ reporter) proliferated (BrdU+) and subsequently gave rise to neurons (DCX, NEUROD or PROX1). The neuronal fates that we observed ranged from neuronal precursors positive for NEUROD (Figure 3B) or DCX (Figure 3C) to granular neurons positive for PROX1 (Figure 3D), CALBINDIN or NEUN (data not shown). The majority of Sox2+ cells gave rise to granular neurons within one month after birth (Table 1). In addition, some daughter cells of targeted Sox2+ cells differentiated to GFAP+ (Figure 3E) or S-100β+ (Figure 3F) astrocytes with a lower frequency (Table 1). The differentiation potential of Sox2+ cells to neurons (≈89%) and astrocytes (≈7%) that we observed is comparable to results from BrdU- or retrovirus-mediated fate mapping of dividing cells in the hippocampus (Steiner et al., 2004; van Praag et al., 2002).

Table 1. Differentiation potential of the Sox2+ NSC population.

The differentiation capacity of progeny of Sox2+ NSCs was examined with cell type-specific markers, and quantitative results were summarized. Note that the percentages of phenotype do not add up to 100% because IHC with these antibodies was performed individually.

| Cell Type Markers | (BrdU:GFP) | (BrdU:GFP:Marker) | (Percentage) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuron | DCXPROX1NEUN | 232736 | 42432 | 17.388.988.9 |

| Astrocyte | S-100βGFAP | 3241 | 34 | 6.19.8 |

| NSC | BLBPSOX2 | 5055 | 16 | 210.9 |

We next examined whether proliferation of Sox2+ cells was associated with generation of undifferentiated cells. Indeed, about 10% of the progeny derived from targeted Sox2+ cells maintained SOX2 expression (Figure 3G), and 2% of traced cells expressed the undifferentiated cell marker, BLBP (Figure 3H). These data collectively indicate that Sox2+ cells in the SGZ not only have the potential to give rise to neurons and astrocytes but can also serve as a source for new, undifferentiated cells.

Identification of multipotent Sox2+ NSCs in the adult hippocampus

While our fate mapping studies revealed the differentiation potentials of Sox2+ cells as a population, it was unclear whether a single Sox2+ cell retains multipotency in the adult dentate gyrus. Thus, we adapted retroviral-mediated labeling of Sox2+ cells to examine the lineage relation between Sox2+ cells and neural cell types derived from Sox2+ cells in the adult hippocampus (Seri et al., 2004).

_Sox2_-Cre/GFP retrovirus was generated to label dividing Sox2+cells exclusively and trace their fates clonally. First, we tested the specific retroviral transduction in Sox2+ cells by double IHC with GFP and SOX2 antibodies. The majority of targeted cells (GFP+) showed specific SOX2 expression when we analyzed them 7 days after retrovirus injection into the dentate gyri of C57BL6 mice (92% ± 1.7, mean ± s.e.m, n=3). Second, the serially diluted _Sox2_-Cre/GFP retrovirus was injected into the dentate gyri of C57BL/6 mice to titrate the concentration that would produce a small number of clusters. Then, we extrapolated the viral concentration that corresponded to generating approximately 10 clusters per hemisphere to minimize the mixture of progeny from different Sox2+cells.

We injected 0.5 μl of _Sox2_-Cre/GFP retrovirus (of ≈5×106 colony forming unit/μl) into both dentate gyri of ROSA26R reporter mice (R=GFP or β–GAL, n=54 hemispheres), and brains were examined 21 days after viral injection. To identify the composition of cell types in clusters, IHC with cell-type specific antibodies was performed.

This approach generated approximately 7 isolated clusters of cells per hemisphere that were likely to be derived from independent Sox2+ cells (Table 2, 6.7 ± 1.5, mean ± s.e.m, n=54). Among 363 clusters (GFP+ or β-GAL+ cells) we examined, 78% of clusters were single-cell clones consisting of a neuron (NeuN+, Figure 4A), an astrocyte (GFAP+, Figure 4B) or a Sox2+ cell, and 10% of them were multi-cell clusters of homogeneous populations containing two Sox2+cells (SOX2+, Figure 4C) or 2 neurons (NeuN+, Figure 4D) (Table 2). Since a retrovirus only transduces one of the two daughter cells of dividing cells, single cell clones are generated by the conversion of Sox2+ cells to downstream lineage.

Table 2. Lineage relationship between Sox2+ NSCs and other neural cell types derived from Sox2+ NSCs.

A: astrocyte, N: neuron, S: Sox2+ NSC, ND: undetermined.

| N only | A only | S only | S + N | N + A | UD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # of clusters | 269 (1) | 5 (1) | 9 (1) | 15 | 1 | 29 |

| (# of cells in cluster) | 32 (2) | 2 (2) | 1 (2) | |||

| 301 | 7 | 10 | 15 | 1 | 29 |

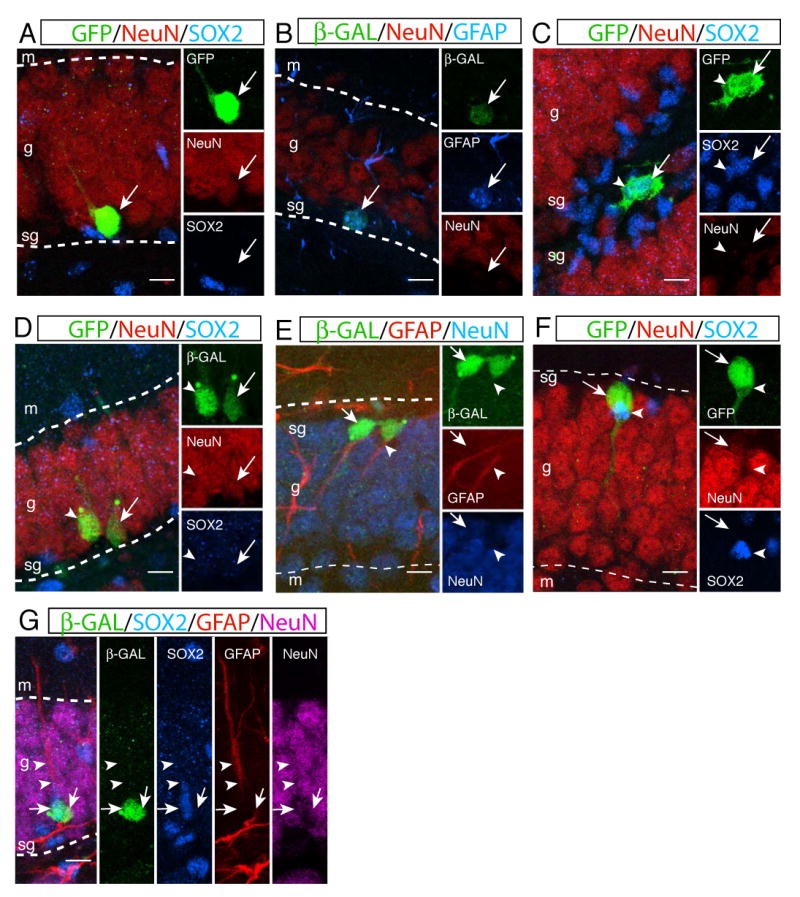

Figure 4. Lineage tracing of Sox2+ cells at a single cell level.

_Sox2_-GFP/Cre retrovirus was injected into the dentate gyrus of ROSA26R mice to activate a reporter (β-gal or GFP reporter), which was used to trace the fate of progeny of Sox2+ cells. The majority of clones were single-cell clusters showing that targeted Sox2+ cells (GFP+ or β-gal+ cells) became a neuron (A, NeuN+), an astrocyte (B, GFAP+) or a NSC. Sox2+ cells were able to give rise to multiple NSCs (C, SOX2+, arrow and arrowhead) or neurons (D, NeuN+, arrow and arrowhead) in the hippocampus. Multi-cell clusters containing heterogeneous cell populations were also identified. One clone showed Sox2+ NSC could give rise to one neuron (NeuN+, arrow) and one astrocyte (GFAP+, arrowhead) (E). Some clones contained a Sox2+ NSC (SOX2+, arrowhead) and a neuron (NeuN+, arrow) that were physically associated each other (F). Sox2+ NSC was able to give rise to a neuron (NeuN+, right arrow) and a Sox2+ NSC (SOX2+, left arrow) that has GFAP expression (two arrowheads) in the radial process (G). Abbreviations: s, subgranular zone; g, granular layer; m, molecular layer. Scale bar: 10 μm.

We were also able to identify some clusters containing mixed cell populations that were informative to examine the multipotency of Sox2+ cells at a single cell level. Fifteen clusters had a Sox2+ and a NeuN+ cell that were tightly associated each other, suggesting that a single Sox2+ cell is capable of giving rise to one NSC and one differentiated neuron (Figure 4F, Figure 4S). We also found one cluster that consisted of one NeuN+ and one GFAP+ (but SOX2-) cell, which supports the existence of Sox2+ NSCs that can give rise to both neurons and astrocytes (Figure 4E). Interestingly, one cluster contained a neuron (NeuN+) and a Sox2+ cell that also expressed GFAP in the radial process (Figure 4G, Figure 4S). These results clearly show that non-radial Sox2+ cells not only have the potential to produce differentiated neural lineages (multipotent) but also are capable of giving rise to both radial and non-radial Sox2+ cells (self-renewal) at a single cell level, providing the evidence that Sox2+ cells are indeed the self-renewing and multipotent NSCs in the SGZ.

Increased proliferation of Sox2+ NSCs is responsible for enhanced neurogenesis

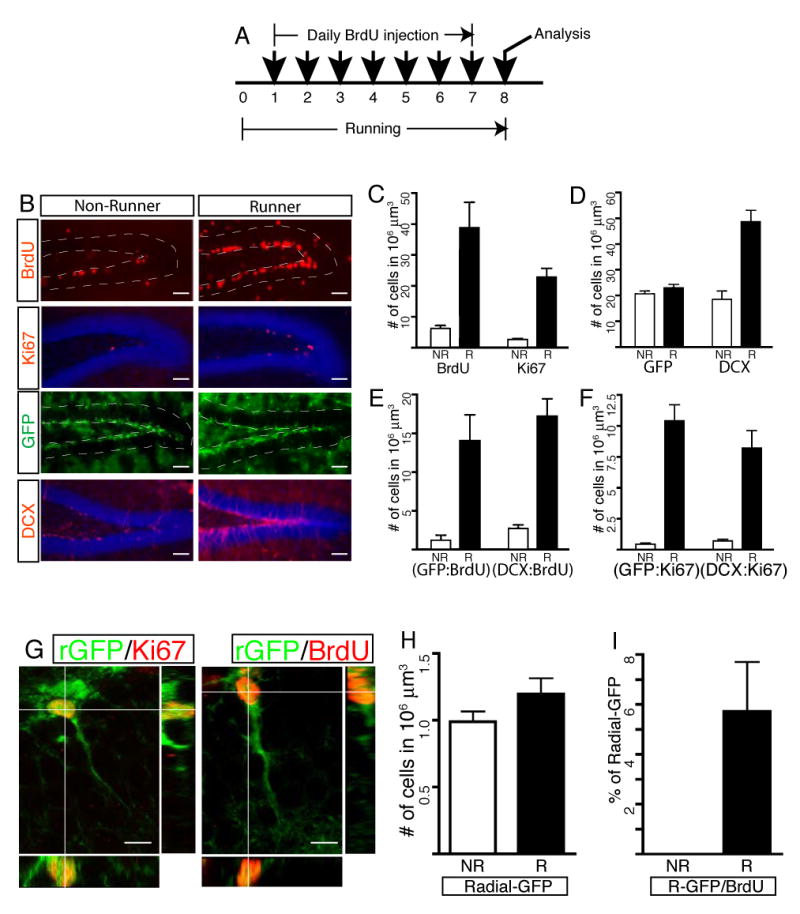

Mice with voluntary access to running wheels exhibited increased proliferation, subsequently leading to increased neurogenesis (van Praag et al., 1999). However, it is not clear which cell type(s) was (were) proliferating and/or giving rise to the new neurons. Hence, we tested the hypothesis that proliferation of Sox2+ NSCs is responsible for the increased neurogenesis in running mice (Figure 5A).

Figure 5. Increased proliferation of Sox2+ NSCs is indicative of enhanced neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus.

Transgenic mice were housed in running wheel cages for 7 days. During the running period, they received a daily BrdU injection to examine the proliferation effects of _Sox2_-GFP cells in the SGZ (A). Representative images with antibody staining used for quantitative analysis are displayed in (B). Total number of dividing cell population (BrdU and Ki67) significantly increased in running mice (C). While numbers of DCX+ precursors or immature neurons expanded, the number of _Sox2_-GFP cells remained unchanged (D) even after more newly born _Sox2_-GFP cells were generated (E). Increased numbers of Sox2+ NSCs and DCX+ precursors were in cell cycle, indicating that running affected those two cell types (F). When neurogenesis increased in running mice, radial _Sox2_-GFP cells proliferated, showing Ki67 expression and BrdU incorporation (G). However, the total number of radial _Sox2_-GFP did not increase significantly (H), although 6% of total radial GFP cells proliferated in running mice (I). Abbreviations in graphs: NR, non-runner; R, runner; rGFP, radial _Sox2_-GFP cells. Scale bars: 50 μm (B) or 10 μm (G).

Consistent with previous results (van Praag et al., 1999), the number of BrdU-positive cells increased in running mice (Figure 5B and 5C). While a few _Sox2_-GFP cells were labeled with BrdU in non-running mice, a much greater proportion of _Sox2_-GFP cells showed co-localization with BrdU in running mice (Figure 5E). Interestingly, however, the total number of _Sox2_-GFP cells did not change (Figure 5B and 5D, p=0.1724, n=7, unpaired t-test), even after the significant increase of BrdU-positive _Sox2_-GFP cells (Figure 5E, GFP/BrdU double). Since both dividing cells and their progeny can be labeled with BrdU in this accumulative injection paradigm, we used the cycling cell marker Ki67 to examine whether acutely dividing _Sox2_-GFP cell population also increased in running mice. The total number of the Ki67-positive dividing cell population increased (Figure 5B, and 5C), concomitant with an increase in actively proliferating _Sox2_-GFP cells (Figure 5F, GFP/Ki67 double) in the running mice.

Maintenance of a constant number of _Sox2_-GFP cells should be achieved by a mechanism that can account for increased neurogenesis in running mice. DCX has been shown to serve as a marker for neuronal precursors, and the number of DCX+ cells is positively correlated with the level of adult neurogenesis (Couillard-Despres et al., 2005). The number of DCX+ (Figure 5B and 5D) and DCX/BrdU double-positive cells (Figure 5E) increased significantly in runners, indicating that an increased number of DCX+ precursors was generated through the cell division in running mice. These observations collectively demonstrate that increased cycling of Sox2+ NSCs is associated with the production of new Sox2+ cells and the generation of committed neurons in running mice.

Between the two morphologically different _Sox2_-GFP populations, the non-radial cells accounted for the proliferation of _Sox2_-GFP cells in non-running mice (Figure 5I). In contrast with the earlier observation that no radial cells underwent cell proliferation in non-runners, cycling of radial _Sox2_-GFP cells was evident in running mice, showing expression of Ki67 or BrdU incorporation in the radial _Sox2_-GFP cells (Figure 5G and 5I). A small portion of radial _Sox2_-GFP cells proliferated (Figure 5G), but this did not affect the total number of radial _Sox2_-GFP cells in running mice (Figure 5H, p=0.1125, N=5).

Discussion

Sox2+ cells are authentic NSCs in the SGZ

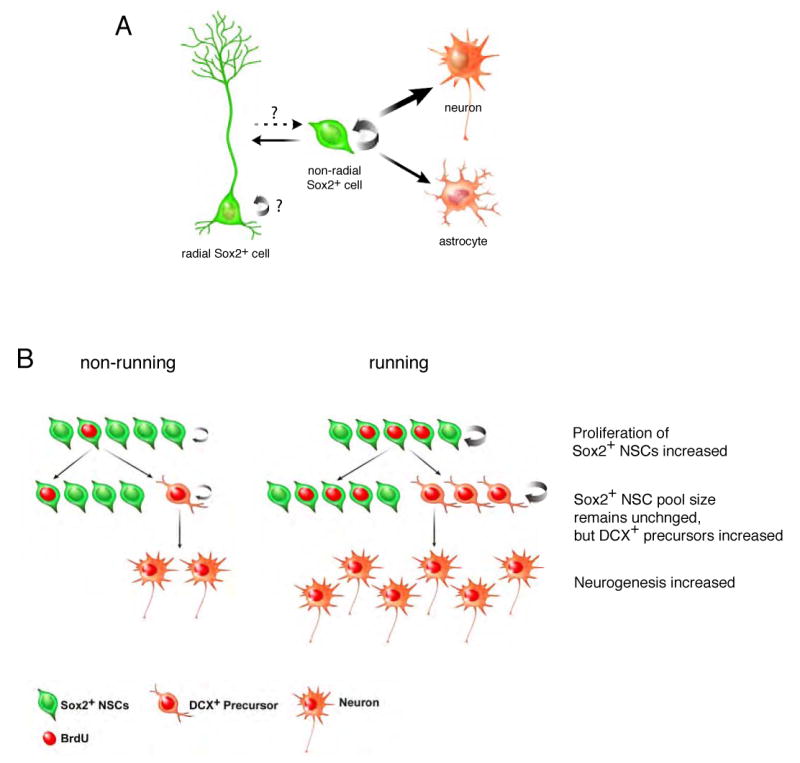

While the presence of adult NSCs has been suggested mainly by in vitro observations and/or by the expressions of putative NSC markers, their self-renewal and multipotent properties have not been clearly demonstrated in vivo. In the same context, Sox2 has been implicated in NSCs (Bylund et al., 2003; Ellis et al., 2004; Ferri et al., 2004; Graham et al., 2003; Taranova et al., 2006), but the question of whether Sox2+ cells in the SGZ possess the multipotent and self-renewing capacities has remained unsolved. To directly address this issue in vivo, we followed the fate of Sox2+ cell populations and traced the lineage of a single Sox2+ cell to understand the differentiation potentials of Sox2+ cells by modifying a lentivirus- and a retrovirus-mediated gene delivery system, respectively. The results from these experiments demonstrated that Sox2+ cells indeed contained the multipotent and self-renewing NSC properties at the population as well as a single cell level. Moreover, our study provided a clue to defining a lineage relationship between radial and non-radial Sox2+ NSCs, which led to our new model for adult neurogenesis (Figure 6A).

Figure 6. Contribution of Sox2+ NSCs to adult neurogenesis.

A. Non-radial Sox2+ NSCs have potentials to generate identical cells (SOX2+) and give rise to downstream neural cell types, suggesting that non-radial Sox2+ cells retain the self-renewing and multipotent NSCs. Sox2+ NSCs preferentially gave rise to neurons, presumably due to the influence of stronger neurogenic niche. Non-radial Sox2+ NSCs also have the potential to give rise to radial Sox2+ NSCs, suggesting that the equilibrium between radial and non-radial Sox2+ NSCs may have a significant role in the homeostatic control of adult neurogenesis. B. Sox2+ NSCs proliferated and generated increased numbers of newly born Sox2+ cells in response to mitotic signals (running induced). However, the increase in new Sox2+ cells did not contribute to expansion of the Sox2+ NSC pool; the total number of Sox2+ NSCs remained unchanged. Increased proliferation of Sox2+ NSCs was associated with the generation of new DCX+ precursors, which subsequently led to production of new neurons in the SGZ. Thus, population-wise, proliferation of Sox2+ NSCs was coupled with the generation of neuronal precursors as well as maintenance of NSCs. Note that asymmetric contribution is used to explain the generation of two different cell types but does not imply asymmetric division of individual cells.

Our lentivirus-mediated fate mapping studies revealed that Sox2+ cells in the SGZ retained the differentiation potentials to give rise to both neurons and astrocytes. Interestingly, a majority of newly born cells from Sox2+ cells became granular neurons (PROX1+), but astrocyte formation was limited. Since our fate analysis did not resolve the multipotency of a single Sox2+ cell, but rather traced the fates of Sox2+ cell populations, it raised two potential interpretations of our results. It is possible that Sox2+ cells are a mixture of lineage-committed progenitors (neuronal vs. astroglial), among which Sox2+ neuronal progenitors are predominant. Alternatively, our observation may reflect the possibility that Sox2+ cells represent NSCs that have a potential to produce both neurons and astrocytes but the hippocampal niche favors neuronal differentiation of Sox2+ NSCs. Results from our retrovirus-mediated lineage tracing in which we directly examined the lineage relation between a single Sox2+ cell and its progeny supported the latter case. While the majority of traced Sox2+ cells gave rise to single-cell clusters containing a neuron, an astrocyte, or a Sox2+ cell, some informative clusters consisting of mixed-cell populations were also identified. Fifteen clusters contained a Sox2+ cell and a differentiated neuron that were tightly associated with each other, consistent with our previous observation that Sox2+ cells are biased to produce neurons. Moreover, we also identified one cluster consisting of one neuron and one astrocyte. These results collectively demonstrated that the Sox2+ cells, at a single cell level, are truly multipotent NSCs that are capable of giving rise to heterogeneous cell types, but Sox2+ NSCs are more favorable for neuronal differentiation over astrocyte formation (Figure 6A).

Why is the acquisition of neuronal cell fate preferential in the adult hippocampus? We speculate that the environmental influence may be responsible for the predominant neuronal differentiation of Sox2+ NSCs. The homeostatic balance between maintenance of NSCs and their cell-fate choice upon differentiation is determined by the interactions between NSCs and the microenvironment referred as to a niche (reviewed in Palmer, 2002; Scadden, 2006). Although the molecular and cellular nature of the hippocampal niche has not been clearly defined, the hippocampal niche appears to promote NSCs to produce more neurons than astrocytes, as suggested from the analysis of Tlx mutant mice (Shi et al., 2004). An orphan receptor, Tlx, has been shown to have dual roles in adult neurogenesis. Tlx is required for proliferation NSCs. At the same time, Tlx is essential for maintenance of the neurogenic potential of NSCs by suppressing glial-specific gene expressions, as astrocyte formation evidently increased in Tlx deficient mice (Shi et al., 2004). Therefore, even if Sox2+ NSCs have potentials to give rise to both neurons and astrocytes, the hippocampal niche is likely to instruct Sox2+ NSCs to produce neurons preferentially.

Our fate tracing experiments also provided an important clue to understanding the self-renewal property of Sox2+ NSCs. Some progeny of Sox2+ NSCs clearly gave rise to undifferentiated cells by virtue of maintenance of SOX2 (≈10%) or BLBP (≈2%) expression. In an attempt to trace the lineage of a single Sox2+ cell, the identification of clusters in which one Sox2+ cell is tightly associated with one neuron further suggested that differentiation of Sox2+ NSC to the downstream lineages may be associated with the self-renewal of Sox2+ NSCs in the SGZ. Thus, both lentivirus-mediated fate mapping studies with BrdU paradigm and retrovirus-mediated lineage tracing analyses clearly demonstrated that proliferation of Sox2+ NSCs is coupled with the generation of new Sox2+ cells, reflecting the self-renewing potential of Sox2+ NSCs in the adult hippocampus.

Lineage relationship between radial and non-radial Sox2+ NSCs

The use of GFP as a reporter permitted not only the localization of Sox2+ cells but also a visualization of the morphology of labeled cells that was not possible with antibody staining. The analysis of transgenic mice identified two morphologically distinct _Sox2_-GFP cell populations in the SGZ: radial cells and non-radial cells. Radial _Sox2_-GFP cells are particularly intriguing because there is a hypothesis that radial glial cells may represent NSCs during development (Anthony et al., 2004; Malatesta et al., 2003; Miyata et al., 2001; Noctor et al., 2001) as well as in the adult brain (Fukuda et al., 2003; Kronenberg et al., 2003; Mignone et al., 2004; Seri et al., 2001). Among _Sox2_-GFP cells in the SGZ, 15% of the GFP-expressing cells have the unique radial morphology and show co-localization with radial glial cell markers, including NESTIN, GFAP and BLBP. Moreover, as demonstrated in the current study, these radial _Sox2_-GFP cells have the potential to proliferate by responding to physiological mitotic signals associated with running, suggesting that both radial and non-radial Sox2+ cells may represent NSC populations in the SGZ.

Seri et al. performed the fate mapping of Gfap+ cells in the SGZ and suggested that Gfap+ cells with a radial morphology are “authentic” NSCs (Seri et al., 2004). They further proposed that the hippocampal neurogenesis mediates a linear transition of radial NSCs to the neuroblasts with non-radial morphology. However, no definitive evidence for this lineage conversion of radial Gfap+ cells to non-radial cells as well as the self-renewal capacity of radial Gfap+ cells has been reported. In current study, however, we found that non-radial Sox2+cells are the major proliferating population and no radial Sox2+ cells are dividing in the sedentary mice, consistent with the observation that radial Nestin+ cells rarely divide in the SGZ (Kronenberg et al., 2003). As a consequence of our results, we cannot completely rule out the possibility that radial cells can be derived from non-radial cells, but with low frequency. In fact, when we traced a lineage of dividing Sox2+ NSCs, we identified one cluster containing a differentiated neuron and a Sox2+ cell that is also positive for GFAP in the radial process. This observation raised the possibility that non-radial Sox2+ cells (since retroviral transduction requires cell proliferation) can give rise to radial Sox2+ cells, leading to our new hypothesis: non-radial Sox2+ cells are multipotent and self-renewing NSCs that can give rise to radial Sox2+ cells, and quiescent radial Sox2+ cells may represent a reservoir of cells that can rarely divide. The equilibrium between non-radial Sox2 and radial Sox2+/Gfap+ cells, in particular, may have an important role in providing reserved, uncommitted cells that can only give rise to non-radial Sox2 cells in turn (Figure 6A). Additional evidence for the transition from radial to non-radial cells needs to confirm the latter portion of our hypothesis.

Proliferation of Sox2+ NSCs contributes to running-induced neurogenesis

Our study provided evidence for the positive correlation between proliferation levels of Sox2+ NSCs and neurogenesis. Since the robust neurogenic potential of Sox2+ NSCs was revealed by examining the fate of newly born cells that are derived from Sox2+ NSCs, our results clearly demonstrate that the proliferation level of Sox2+ NSCs is indicative of the generation of new neurons in the adult hippocampus.

To understand the role of Sox2+ NSCs in adult neurogenesis, a running paradigm was used to increase proliferation and neurogenesis in the hippocampus (van Praag et al., 1999). Our study revealed that an increased proportion of Sox2+ NSCs proliferated in response to mitotic signals in running mice. We then quantitatively examined how increased proliferation of Sox2+ NSCs potentially leads to enhanced neurogenesis by testing two hypotheses (reviewed in Morrison and Kimble, 2006). First, the increased proliferation of Sox2+ NSCs may lead to expansion of the size of the Sox2+ NSC pool. This model is reminiscent of the expansion of the stem cell population during brain development, in which stem cells undergo symmetric cell division prior to neurogenesis. If this is the case, the total number of Sox2+ NSCs will increase in running mice. Alternatively, the increased proliferation of Sox2+ NSCs is associated with the asymmetric contribution of daughter cells. This mechanism has a homeostatic advantage of maintaining NSCs and generating differentiated cells in a balanced manner. Our results favor the idea that the asymmetric contribution of daughter cells of Sox2+ NSCs, as a population, is an underlying mechanism explaining the increased neurogenesis in running mice (Figure 6B). Despite the fact that more Sox2+ NSCs are born through increased cell division (increased number of GFP/BrdU and GFP/Ki67 cells), the total number of Sox2+ NSCs does not change in running mice. This stable number of Sox2+ NSCs is, however, associated with an increase in newly born DCX+ neuronal precursors. These observations lead to our model that 1) Sox2+ NSCs are subject to proliferate in response to mitotic signals and 2) the production of both new Sox2+ NSCs and DCX+ precursors concomitantly increases while 3) the number of Sox2+ NSCs remains unchanged in running mice (Figure 6B).

The simplest mechanism to explain these observations is that mitotic signals associated with running increase the asymmetric cell division of Sox2+ NSCs, generating one Sox2+ NSC and one DCX+ precursor after cell division. Asymmetric cell division of NSCs is an attractive model because NSCs can accomplish self-renewal and generation of differentiated neurons at the same time. Moreover, asymmetric division may play a role in preventing Sox2+ NSCs from transforming into tumors, because disruption of asymmetric division of neuroblasts has been shown to cause expansion of neuroblasts, leading to tumor formation in the fly brain (Caussinus and Gonzalez, 2005). However, our current study cannot provide a sufficient resolution to determine the mechanisms for cell division of individual Sox2+ NSCs with respect to their differentiation potential. Identification of the factors that regulate the cell division mechanism in the SGZ is currently underway.

Experimental Procedures

Animal husbandry

Three transgenic mouse lines harboring enhanced GFP-reporter gene under the control of 5.5 kb of mouse Sox2 promoter (generously provided by Dr. Angie Rizzino, University of Nebraska, NE) were generated as previously described (D'Amour and Gage, 2003). Since all 3 lines showed consistent and comparable expression patterns within and between lines, 1 line (1F7) was chosen for the studies. All animals were maintained according to the NIH guidelines for animal care, and animal procedures were performed in accordance with protocols approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Salk Institute. Genotypes were determined by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of genomic DNA prepared from tail biopsies or yolk sacs. PCR condition and primer sequences are available upon request.

Lentivirus vector production and stereotaxic injection

Lentiviral vector-expressing GFP/CRE fusion protein under the control of Sox2 promoter was generated. 3.1 kb of Sox2 promoter consisting of a proximal promoter (2.7kb) and a distal neural enhancer (0.4 kb) was cloned to express GFP reporter and CRE recombinase fusion protein. This enhancer contains a sufficient cis-element that recapitulates endogenous Sox2 expression in CNS (Ferri et al., 2004; Zappone et al., 2000). Detailed information on the lentivirus backbone and virus production has been previously described (Consiglio et al., 2004). 1 μl of replication-incompetent lentivirus (60-100 ng of p24 value) was injected into the dentate gyrus of ROSA26 reporter mice (ROSA26R, R= β-gal or GFP, The Jackson Laboratory) to excise “stop signal” and subsequently activate β-galactosidase (β-gal) or GFP reporter gene expression. The stereotaxic coordinates are listed in mm from bregma: AP=-2, ML=+1.5, DV=-2. 10 or 28 days after the viral injection, mice received daily BrdU injection (100 mg/kg of body weight) for 7 days to label dividing population. The fates of Sox2+ cells that underwent proliferation during this time period were examined 4 weeks after the final BrdU injection by performing IHC with cell type-specific markers.

Retrovirus vector production and lineage tracing

The same Sox2-GFP/CRE construct used for lentivirus-mediated fate mapping was cloned into SmeI and PmeI sites of the Moloney leukemia virus backbone. The retroviral backbone and virus production procedures were previously described in detail (Zhao et al., 2006). 0.5 ul of retrovirus was injected into either C57BL/6 or ROSA26 reporter mice (ROSA26R, R= β-gal or GFP, The Jackson Laboratory) to determine the titer of virus or perform lineage tracing in the dentate gyrus, respectively. For lineage tracing, 27 ROSA26R mice whose ages ranged between 6-weeks and 3-months received the retrovirus in both hemispheres, and their dentate gyri were analyzed 21 days after the injection. The injection coordinate and specific IHC method are described above. The combinations of antibodies to identify cell types derived from Sox2+ NSCs are listed in the format of a primary antibody (a fluorophore conjugated to a secondary antibody). For the analysis of ROSA26 GFP reporter mice, chick α GFP (FITC), goat α SOX2 (Cy5), rabbit α S-100 β (AMCA) and mouse α NEUN (Cy3) were used. For the analysis of ROSA26 β-gal reporter mice, goat α β-gal (FITC), rabbit α SOX2 (Cy5), guinea pig α GFAP (AMCA) and mouse α NEUN (Cy3) were used. All images were taken by confocal microscope using narrow-band filters to detect specific signals.

Running experiment and quantification

Seven transgenic mice were individually housed in cages with voluntary access to running wheels. As controls, 7 wild-type littermates were housed in identical cages without running wheels. All mice received 100 mg/kg BrdU once a day during the running period and were sacrificed 24 hours after the final BrdU injection. Brain sections were prepared as described above. To count GFP-positive cells, every 12th section covering the entire rostro-caudal axis of the dentate gyrus was stained with GFP antibody. Both sides of the dentate gyrus were subject to count in a blind manner. The area of dentate gyrus was measured by stereology (Microbright Field, Inc.) and the volume was calculated by multiplying thickness. To count DCX-, Ki67-, and other double-positive cells, 4 sections at 440-μm intervals (every 12th section) containing dorsal hippocampus were selected from each animal and stained with respective antibodies. After staining, the entire dentate gyri were scanned with a confocal microscope and z-series images were collected. The number of singly or doubly stained cells was counted using Metamorph (Molecular Devices). Statistical analysis (unpaired t-test, two-tailed, p<0.05) was performed using Statview (SAS). All graphs were drawn in Prism (GraphPad).

FACS sorting and FACS analysis of _Sox2_-GFP cells

The content of _Sox2_-GFP cells in the hippocampal cells or in cultured cells was measured by fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS; Becton-Dickinson FACScan). Hippocampal cells from the adult _Sox2_-GFP transgenic mice were isolated as described above and only live cells were used for FACS analysis after staining with propidium iodide (Molecular Probe).

Supplementary Material

01

Supplementary Methods

Experimental procedures for IHC and ISH and in vitro experiments including preparation, culture and differentiation of _Sox2_-GFP NSCs were described in Supplementary Methods.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Gage lab members for critical reading and discussion and to Mary Lynn Gage for editorial support. A mouse Sox2 promoter was a generous gift from Dr. Angie Rizzino (University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE). We thank Dr. Okano Hideyuki (Keio University, Japan) and Dr. Nathaniel Heintz (Rockefeller University, New York, NY) for providing MUSASHI-1 and BLBP antibodies, respectively. H. S. is a recipient of ASPET-Merck fellowship. A.C. was recipient of a Telethon postdoctoral fellowship. This work was supported by the Pritzker Neurogenesis Consortium, the Lookout Fund, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), the US National Institutes of Health (NS-05050217 and NS-05052842) and National Institute of Aging (AG-020938) (F.H.G).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anthony TE, Klein C, Fishell G, Heintz N. Radial glia serve as neuronal progenitors in all regions of the central nervous system. Neuron. 2004;41:881–890. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00140-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avilion AA, Nicolis SK, Pevny LH, Perez L, Vivian N, Lovell-Badge R. Multipotent cell lineages in early mouse development depend on SOX2 function. Genes Dev. 2003;17:126–140. doi: 10.1101/gad.224503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bani-Yaghoub M, Tremblay RG, Lei JX, Zhang D, Zurakowski B, Sandhu JK, Smith B, Ribecco-Lutkiewicz M, Kennedy J, Walker PR, Sikorska M. Role of Sox2 in the development of the mouse neocortex. Dev Biol. 2006;295:52–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bylund M, Andersson E, Novitch BG, Muhr J. Vertebrate neurogenesis is counteracted by Sox1-3 activity. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:1162–1168. doi: 10.1038/nn1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caussinus E, Gonzalez C. Induction of tumor growth by altered stem-cell asymmetric division in Drosophila melanogaster. Nat Genet. 2005;37:1125–1129. doi: 10.1038/ng1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consiglio A, Gritti A, Dolcetta D, Follenzi A, Bordignon C, Gage FH, Vescovi AL, Naldini L. Robust in vivo gene transfer into adult mammalian neural stem cells by lentiviral vectors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:14835–14840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404180101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couillard-Despres S, Winner B, Schaubeck S, Aigner R, Vroemen M, Weidner N, Bogdahn U, Winkler J, Kuhn HG, Aigner L. Doublecortin expression levels in adult brain reflect neurogenesis. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:1–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03813.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amour KA, Gage FH. Genetic and functional differences between multipotent neural and pluripotent embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100 1:11866–11872. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834200100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis P, Fagan BM, Magness ST, Hutton S, Taranova O, Hayashi S, McMahon A, Rao M, Pevny L. SOX2, a persistent marker for multipotential neural stem cells derived from embryonic stem cells, the embryo or the adult. Dev Neurosci. 2004;26:148–165. doi: 10.1159/000082134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferri AL, Cavallaro M, Braida D, Di Cristofano A, Canta A, Vezzani A, Ottolenghi S, Pandolfi PP, Sala M, DeBiasi S, Nicolis SK. Sox2 deficiency causes neurodegeneration and impaired neurogenesis in the adult mouse brain. Development. 2004;131:3805–3819. doi: 10.1242/dev.01204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda S, Kato F, Tozuka Y, Yamaguchi M, Miyamoto Y, Hisatsune T. Two distinct subpopulations of nestin-positive cells in adult mouse dentate gyrus. J Neurosci. 2003;23:9357–9366. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-28-09357.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabay L, Lowell S, Rubin LL, Anderson DJ. Deregulation of dorsoventral patterning by FGF confers trilineage differentiation capacity on CNS stem cells in vitro. Neuron. 2003;40:485–499. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00637-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gage FH. Mammalian neural stem cells. Science. 2000;287:1433–1438. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5457.1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham V, Khudyakov J, Ellis P, Pevny L. SOX2 functions to maintain neural progenitor identity. Neuron. 2003;39:749–765. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00497-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawaguchi A, Miyata T, Sawamoto K, Takashita N, Murayama A, Akamatsu W, Ogawa M, Okabe M, Tano Y, Goldman SA, Okano H. Nestin-EGFP transgenic mice: visualization of the self-renewal and multipotency of CNS stem cells. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2001;17:259–273. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2000.0925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronenberg G, Reuter K, Steiner B, Brandt MD, Jessberger S, Yamaguchi M, Kempermann G. Subpopulations of proliferating cells of the adult hippocampus respond differently to physiologic neurogenic stimuli. J Comp Neurol. 2003;467:455–463. doi: 10.1002/cne.10945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn HG, Dickinson-Anson H, Gage FH. Neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of the adult rat: age-related decrease of neuronal progenitor proliferation. J Neurosci. 1996;16:2027–2033. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-06-02027.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lois C, Alvarez-Buylla A. Proliferating subventricular zone cells in the adult mammalian forebrain can differentiate into neurons and glia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:2074–2077. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.5.2074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malatesta P, Hack MA, Hartfuss E, Kettenmann H, Klinkert W, Kirchhoff F, Gotz M. Neuronal or glial progeny: regional differences in radial glia fate. Neuron. 2003;37:751–764. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00116-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mignone JL, Kukekov V, Chiang AS, Steindler D, Enikolopov G. Neural stem and progenitor cells in nestin-GFP transgenic mice. J Comp Neurol. 2004;469:311–324. doi: 10.1002/cne.10964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyata T, Kawaguchi A, Okano H, Ogawa M. Asymmetric inheritance of radial glial fibers by cortical neurons. Neuron. 2001;31:727–741. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00420-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison SJ, Kimble J. Asymmetric and symmetric stem-cell divisions in development and cancer. Nature. 2006;441:1068–1074. doi: 10.1038/nature04956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noctor SC, Flint AC, Weissman TA, Dammerman RS, Kriegstein AR. Neurons derived from radial glial cells establish radial units in neocortex. Nature. 2001;409:714–720. doi: 10.1038/35055553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer TD. Adult neurogenesis and the vascular Nietzsche. Neuron. 2002;34:856–858. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00738-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray J, Gage FH. Differential properties of adult rat and mouse brain-derived neural stem/progenitor cells. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2006;31:560–573. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds BA, Weiss S. Generation of neurons and astrocytes from isolated cells of the adult mammalian central nervous system. Science. 1992;255:1707–1710. doi: 10.1126/science.1553558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rietze RL, Valcanis H, Brooker GF, Thomas T, Voss AK, Bartlett PF. Purification of a pluripotent neural stem cell from the adult mouse brain. Nature. 2001;412:736–739. doi: 10.1038/35089085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy NS, Wang S, Jiang L, Kang J, Benraiss A, Harrison-Restelli C, Fraser RA, Couldwell WT, Kawaguchi A, Okano H, et al. In vitro neurogenesis by progenitor cells isolated from the adult human hippocampus. Nat Med. 2000;6:271–277. doi: 10.1038/73119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakakibara S, Okano H. Expression of neural RNA-binding proteins in the postnatal CNS: implications of their roles in neuronal and glial cell development. J Neurosci. 1997;17:8300–8312. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-21-08300.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scadden DT. The stem-cell niche as an entity of action. Nature. 2006;441:1075–1079. doi: 10.1038/nature04957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seri B, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Collado-Morente L, McEwen BS, Alvarez-Buylla A. Cell types, lineage, and architecture of the germinal zone in the adult dentate gyrus. J Comp Neurol. 2004;478:359–378. doi: 10.1002/cne.20288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seri B, Garcia-Verdugo JM, McEwen BS, Alvarez-Buylla A. Astrocytes give rise to new neurons in the adult mammalian hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2001;21:7153–7160. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-18-07153.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y, Chichung Lie D, Taupin P, Nakashima K, Ray J, Yu RT, Gage FH, Evans RM. Expression and function of orphan nuclear receptor TLX in adult neural stem cells. Nature. 2004;427:78–83. doi: 10.1038/nature02211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song H, Stevens CF, Gage FH. Astroglia induce neurogenesis from adult neural stem cells. Nature. 2002;417:39–44. doi: 10.1038/417039a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steiner B, Kronenberg G, Jessberger S, Brandt MD, Reuter K, Kempermann G. Differential regulation of gliogenesis in the context of adult hippocampal neurogenesis in mice. Glia. 2004;46:41–52. doi: 10.1002/glia.10337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taranova OV, Magness ST, Fagan BM, Wu Y, Surzenko N, Hutton SR, Pevny LH. SOX2 is a dose-dependent regulator of retinal neural progenitor competence. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1187–1202. doi: 10.1101/gad.1407906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashiro A, Sandler VM, Toni N, Zhao C, Gage FH. NMDA-receptor-mediated, cell-specific integration of new neurons in adult dentate gyrus. Nature. 2006;442:929–933. doi: 10.1038/nature05028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Praag H, Kempermann G, Gage FH. Running increases cell proliferation and neurogenesis in the adult mouse dentate gyrus. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:266–270. doi: 10.1038/6368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Praag H, Schinder AF, Christie BR, Toni N, Palmer TD, Gage FH. Functional neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus. Nature. 2002;415:1030–1034. doi: 10.1038/4151030a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zappone MV, Galli R, Catena R, Meani N, De Biasi S, Mattei E, Tiveron C, Vescovi AL, Lovell-Badge R, Ottolenghi S, Nicolis SK. Sox2 regulatory sequences direct expression of a (beta)-geo transgene to telencephalic neural stem cells and precursors of the mouse embryo, revealing regionalization of gene expression in CNS stem cells. Development. 2000;127:2367–2382. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.11.2367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C, Teng EM, Summers RG, Jr, Ming GL, Gage FH. Distinct morphological stages of dentate granule neuron maturation in the adult mouse hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2006;26:3–11. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3648-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

01

Supplementary Methods

Experimental procedures for IHC and ISH and in vitro experiments including preparation, culture and differentiation of _Sox2_-GFP NSCs were described in Supplementary Methods.