Lymphotoxin α/β and Tumor Necrosis Factor Are Required for Stromal Cell Expression of Homing Chemokines in B and T Cell Areas of the Spleen (original) (raw)

Abstract

Mice deficient in the cytokines tumor necrosis factor (TNF) or lymphotoxin (LT) α/β lack polarized B cell follicles in the spleen. Deficiency in CXC chemokine receptor 5 (CXCR5), a receptor for B lymphocyte chemoattractant (BLC), also causes loss of splenic follicles. Here we report that BLC expression by follicular stromal cells is defective in TNF-, TNF receptor 1 (TNFR1)-, LTα- and LTβ-deficient mice. Treatment of adult mice with antagonists of LTα1β2 also leads to decreased BLC expression. These findings indicate that LTα1β2 and TNF have a role upstream of BLC/CXCR5 in the process of follicle formation. In addition to disrupted follicles, LT-deficient animals have disorganized T zones. Expression of the T cell attractant, secondary lymphoid tissue chemokine (SLC), by T zone stromal cells is found to be markedly depressed in LTα-, and LTβ-deficient mice. Expression of the SLC-related chemokine, Epstein Barr virus–induced molecule 1 ligand chemokine (ELC), is also reduced. Exploring the basis for the reduced SLC expression led to identification of further disruptions in T zone stromal cells. Together these findings indicate that LTα1β2 and TNF are required for the development and function of B and T zone stromal cells that make chemokines necessary for lymphocyte compartmentalization in the spleen.

Keywords: lymphoid tissue, follicle, lymphocyte, follicular dendritic cell, dendritic cell

Genetic studies in mice have established that the cytokines TNF, lymphotoxin α (LTα),1 and LTβ, and the receptors TNFR1 and LTβR, are required for normal compartmentalization of lymphocytes in the spleen (1, 2). In TNF- and TNFR1-deficient mice, follicular dendritic cells (FDCs) are lacking and B cells fail to form follicular clusters, instead appearing in a ring at the T zone periphery (3–6). Mice deficient in LTα, which are deficient in membrane LTα1β2 heterotrimers and soluble LTα3 complexes (7), show a distinct phenotype that includes absence of lymph nodes and Peyer's patches, and loss of marginal zone cells, FDCs, and normal B/T segregation in white pulp cords of the spleen (6, 8–10). LTβ−/− mice, which cannot produce membrane forms of LT that bind LTβR but continue to express LTα, exhibit a similar phenotype except that some lymph nodes are retained and splenic architecture is somewhat less disturbed than in LTα−/− mice (11, 12; Korner, H., and J.D. Sedgwick, unpublished observations).

In parallel studies an understanding has begun to develop of the role played by chemokine receptors and chemokines in controlling cell movements within lymphoid tissues. Mice lacking CXCR5 (formerly Burkitt's lymphoma receptor 1 [BLR1]), a chemokine receptor expressed by mature B cells (13, 14), lack polarized follicles in the spleen and B cells appear as a ring at the boundary of the T zone (5). Recently, a CXCR5 ligand, termed B lymphocyte chemoattractant (BLC) or B cell attracting chemokine (BCA)-1 (15, 16), has been found constitutively expressed by stromal cells in lymphoid follicles and has been proposed to act as a B cell homing chemokine (15). Three other chemokines have been identified that are constitutively expressed in lymphoid tissues and that are efficacious attractants of resting lymphocytes: stromal cell–derived factor 1 (SDF1 [17–19]), secondary lymphoid tissue chemokine (SLC)/6Ckine (20–24), and EBV-induced molecule 1 ligand chemokine (ELC)/macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-3β (25–28). SDF1 is an efficacious attractant of mature lymphocytes (19), although its pattern of expression in lymphoid tissues is not well characterized. SLC and ELC are related chemokines that strongly attract naive T cells and more weakly attract B cells. SLC is expressed by high endothelial venules (HEVs) in lymph nodes and Peyer's patches and by stromal cells in the T zone of spleen, lymph nodes, and Peyer's patches (21, 22, 24), whereas ELC is expressed by T zone DCs (27). The strong chemotactic activity of SLC and ELC combined with their compartmentalized expression pattern has led to the suggestion that these molecules function in lymphocyte homing to the T zone of peripheral lymphoid tissues (21, 27).

The strikingly similar disruption of splenic B cell distribution in TNF- and CXCR5-deficient mice suggested that these molecules act in a common pathway to maintain follicular organization (29). The more severe splenic disruptions in LTα/β-deficient mice suggest LT may function upstream of molecules that help organize cells into both follicles and T zones. Here we report that expression of the CXCR5 ligand, BLC, is substantially reduced in TNF-, TNFR1-, LTα-, and LTβ-deficient mice. Expression of SLC and ELC is also reduced, whereas SDF1 is unaffected. Antagonism of LTα1β2 function in the adult by treatment with soluble LTβR-Ig or anti-LTβ antibody caused reductions in BLC and SLC expression. We also observed that in addition to defects in follicular stromal cells, the LT- and TNF-deficient mice had disruptions in T zone stromal cells. To identify which cell types may act as sources of the LTα/β and TNF required for upregulating BLC expression, mice lacking subpopulations of hematopoietic cells were studied. Mice deficient in B cells, which also lack follicular stromal cells, had reduced BLC expression, whereas T cell and marginal zone macrophage (MZM)-deficient mice were unaffected. These findings suggest that TNF and membrane LTα/β heterotrimer transmit signals required for the development and function of stromal cells that produce chemokines essential for normal organization of lymphoid tissue compartments.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

TNF−/−, TNF/LTα−/−, and LTα−/− mice were generated using C57BL/6 embryonic stem (ES) cells and maintained on a pure C57BL/6 background as described (6, 30). A further strain, generated by targeting of the LTβ gene in Bruce 4 C57BL/6 ES cells (31), was produced. The LTβ gene was disrupted by insertion of the neomycin cassette in reverse orientation in exon I, leading to complete gene inactivation and typical LTβ−/− phenotype (Korner, H., D.S. Riminton, F.A. Lemckert, and J.D. Sedgwick, manuscript in preparation). TNFR1−/− mice were generated using C57BL/6 ES cells and were maintained on a pure C57BL/6 background (32). C57BL/6 op/op, C57BL/6 BCR−/− (μMT), C57BL/6 TCR-β−/−δ−/−, and C57BL/6 recombination activating gene (RAG)-1−/− mice were obtained from The Jackson Labs. op/op mice are toothless and were fed powdered mouse chow moistened with water. Mice used for soluble LTβR-Ig (33) or anti-LTβ mAb (BB.F6 [34]) treatment were from a C57BL/6 colony maintained at the University of California San Francisco. Treatment was with 100 μg of fusion protein or 200 μg of antibody intraperitoneally once per week as described previously (35–37). As a control for the LTβR-Ig fusion protein, which contains human IgG1 hinge, CH2 and CH3 regions, mice were treated with a human LFA3-IgG1 hinge, CH2 and CH3 region fusion protein (100 μg/wk, i.p.) as in previous studies (35, 36). Human LFA3 does not bind to mouse CD2 (8). The control group for the hamster anti-LTβ mAb–treated mice were injected with hamster anti-KLH mAb (37).

Northern Blot Analysis.

10–15 μg of total RNA from mouse spleens was subjected to gel electrophoresis, transferred to Hybond N+ membranes (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech), and probed using randomly primed 32P-labeled mouse cDNA probes of the following types: BLC, bases 10–532 (15); SLC, bases 1–848 (21); ELC, bases 1–755 (27); and SDF1α, bases 30–370 (18). To control for loading and RNA integrity, membranes were reprobed with a mouse elongation factor 1α (EF-1α) probe. For quantitation, Northern blots were exposed to a phospho screen for 6 h to 3 d and images were developed using a Storm860 PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics). Data were analyzed using ImageQuant® software (Molecular Dynamics), and chemokine mRNA levels were corrected for RNA loaded by dividing the chemokine hybridization signal by the EF-1α signal for the same sample. Relative expression levels were calculated by dividing the corrected signal for each mutant or treated sample with the mean corrected signal for the wild-type or control treated samples, as appropriate, that were included on each of the Northern blots.

In Situ Hybridization.

For in situ hybridizations, frozen sections (6 μm) were treated as described (15). In brief, sections were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, washed in PBS, prehybridized for 1–3 h, and hybridized overnight at 60°C with sense or antisense digoxigenin-labeled riboprobes in hybridization solution. After washing at high stringency, sections were incubated with sheep antidigoxigenin antibody (Boehringer Mannheim) followed by alkaline phosphatase–coupled donkey anti–sheep antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) and developed with NBT (Bio-Rad) and BCIP (Sigma).

Immunohistochemistry.

Cryostat sections (6–7 μm) were fixed and stained as described previously (27) using the following mAbs: rat anti-B220 (RA3-6B2); rat anti-CD4 and -CD8 (Caltag); rat anti-CD35 (8C12; PharMingen); rat anti-MOMA1 (provided by Georg Kraal, Free University, Amsterdam, The Netherlands); and biotinylated mouse anti–BP-3 (38). Rat IgG antibodies were detected with goat anti–rat-conjugated horseradish peroxidase or alkaline phosphatase (Southern Biotechnology Associates) and biotinylated antibodies with avidin–alkaline phosphatase (Sigma Chemical Co.). Enzyme reactions were developed with conventional substrates for peroxidases (diaminobenzidine/H2O2 [_Sigma_]) and alkaline phosphatase (FAST RED/Naphthol AS-MX [_Sigma_] or NBT/BCIP). In some cases, sections were counterstained with hematoxylin (Fisher Scientific Co.). Sections were mounted in crystal mount (Biomeda Corp.) and viewed with a Leica DMRL microscope. Images were acquired on an Optronics MDEI850 cooled CCD video camera (Optronics Engineering) and were processed with Photoshop software (Adobe Systems, Inc.).

Results

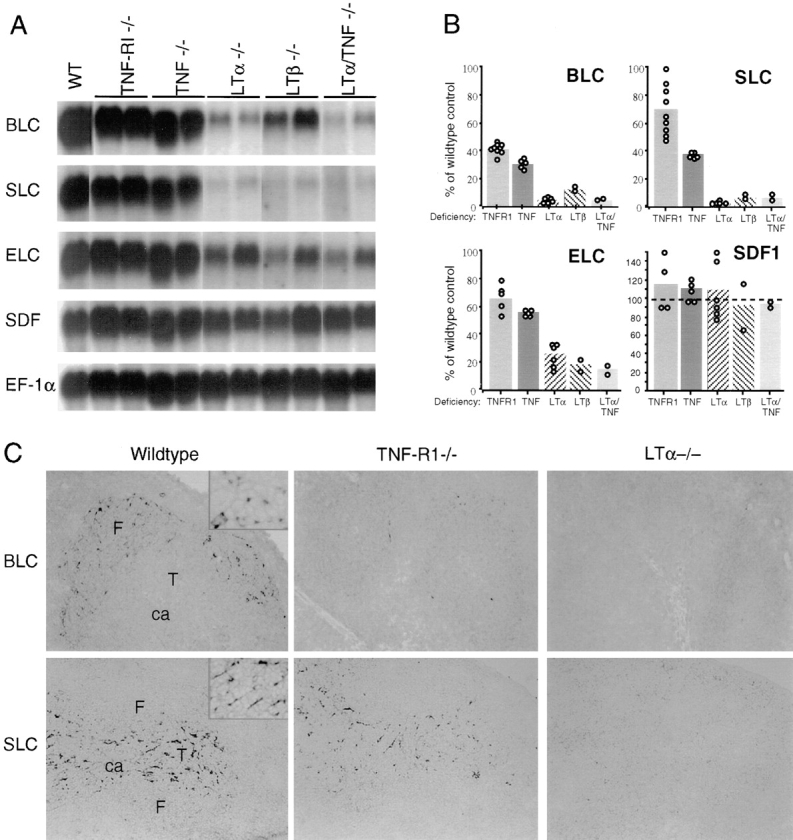

Reduced Chemokine Expression in TNFR1-, TNF-, LTα-, and LTβ-deficient Mice.

To explore whether TNF/TNFR1 and CXCR5 function in a common pathway of follicular organization, we measured CXCR5 expression in TNFR1- and TNF-deficient mice by flow cytometry. Splenic B cells from TNF- and TNFR1-deficient mice expressed levels of CXCR5 that were slightly elevated compared with wild-type controls (39; Ansel, K.M., and J.G. Cyster, data not shown). Increased CXCR5 expression seemed unlikely to account for the disrupted organization of B cells in TNF- or TNFR1-deficient animals, but could result from reduced expression of ligands that normally engage and downregulate CXCR5. Therefore, we tested whether TNF/TNFR1 regulated CXCR5 ligand expression by measuring BLC RNA levels in TNF- and TNFR1-deficient mouse spleens (Fig. 1, A and B). BLC expression was reduced approximately threefold in both types of mutant mice compared with wild-type littermates. In situ hybridization analysis of TNFR1-deficient spleen confirmed the reduced expression of BLC by follicular stromal cells (Fig. 1 C). Animals deficient in LTα or LTβ also lack follicles and follicular stromal cells, although the absence of MZMs and the severely disrupted B/T boundary make the splenic phenotype of these mice distinct. BLC expression was reduced even more severely in spleens from LTα- and LTβ-deficient animals than from TNF-deficient mice (Fig. 1, A and B), and the residual expression was too low to be detected in in situ hybridization analysis (Fig. 1 C). In mice deficient in both LTα and TNF, BLC expression was reduced to an extent similar to LTα single mutants (Fig. 1, A and B), consistent with the possibility that these cytokines function in a common pathway leading to BLC expression.

Figure 1.

Reduced expression of lymphoid tissue chemokines in TNF/TNFR1- and LTα/β-deficient mouse spleen. (A) Northern blot analysis of total RNA isolated from spleen tissue of the indicated mice and probed to detect expression of BLC, SLC, ELC, and SDF1. Hybridization to EF-1α was used to control for RNA loaded. For SDF1, the hybridization signals for SDF1α and SDF1β (reference 18) were similar and the signal for SDF1α is shown. WT, wild-type. (B) Relative chemokine mRNA levels as determined by PhosphorImager analysis of the Northern blot shown in A and additional blots, after correcting for differences in RNA loading from the corresponding EF-1α value. Data from individual mice are shown as open circles and means as shaded bars. (C) In situ hybridization analysis of BLC and SLC expression in spleen from wild-type, TNFR1-deficient, or LTα-deficient mice. Original magnification: ×10. ca, central arteriole; F, follicle; T, T zone. The insets in the BLC and SLC wild-type control panels are included to show the morphology of the chemokine-expressing stromal cells (original magnification: ×40).

Splenic T zone organization is also disrupted in the cytokine- and cytokine receptor–deficient animals, ranging from subtle changes in TNF- and TNFR1-deficient mice to almost complete loss of T zones in LTα, LTβ, and LTα/TNF double mutant mice. To determine whether LTα/β and TNF also functioned in a pathway leading to T zone chemokine expression, we measured the expression of SLC and ELC, related T cell attracting chemokines that are made in the T zone. We also measured expression of the more broadly distributed chemokine, SDF1, which is an efficacious attractant of both B and T cells. SLC was reduced in expression ∼2-fold in TNFR1- and TNF- deficient animals and >20-fold in LTα, LTβ, and LTα/ TNF double mutant animals (Fig. 1, A and B). By in situ hybridization analysis, the network of SLC expressing stromal cells remained visible in the TNFR1 mutant mice but could not be detected in LTα-deficient animals (Fig. 1 C). Expression of ELC was also reduced in all of the mutant strains, although less severely than SLC (Fig. 1, A and B). By contrast, SDF1 expression was not significantly reduced in any of the mutant animals (Fig. 1, A and B), indicating that the reductions in BLC, SLC, and ELC are physiologically relevant and not the result of an overall decrease in chemokine gene expression. It should be emphasized that the TNFR1 mutant and the four cytokine mutants used in this study (6, 30, 32; Korner, H., D.S. Riminton, F.A. Lemckert, and J.D. Sedgwick, unpublished) were all generated using C57BL/6 ES cells and maintained on a C57BL/6 background, making it unlikely that any of the differences we observed in chemokine expression are due to linked genetic differences. Therefore, these experiments demonstrate that TNF/TNFR1 and LTα/β are required for normal expression of BLC, SLC, and ELC in the spleen.

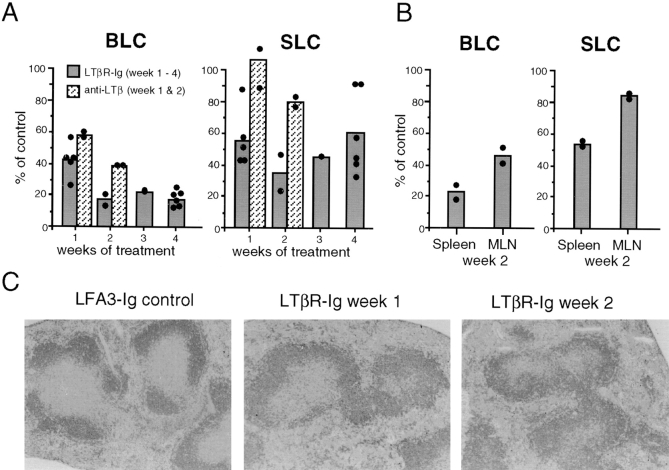

Treatment of Adult Mice with LTα/β Antagonists Diminishes Chemokine Expression.

To determine whether the requirement for LTα and LTβ in the expression of BLC and SLC was developmental or constitutive, we treated adult mice for various time periods with soluble LTβR-Ig fusion protein (8, 40), an antagonist of LTα1β2, and a related molecule, LIGHT (41). Control mice were treated for equal periods of time with an LFA3-Ig fusion protein (8). After 1 wk of LTβR-Ig treatment, splenic BLC expression was reduced twofold compared with the controls (Fig. 2 A). A further reduction in BLC expression occurred after 2 wk of treatment and did not become more severe after 3 or 4 wk of treatment (Fig. 2 A). 2 wk of treatment also lead to decreased BLC levels in mesenteric lymph nodes (Fig. 2 B). Expression of SLC was reduced in spleen and mesenteric lymph nodes of mice given LTβR-Ig, although the degree of inhibition was variable and less severe than the reduction in BLC (Fig. 2, A and B). To distinguish the possible contribution of LIGHT from that of LTα1β2, mice were treated for 1 or 2 wk with an anti-LTβ mAb that specifically blocks LTα/β heterotrimer function (37, 40). Analysis of splenic RNA showed that BLC and SLC expression were both reduced after 2 wk of anti-LTβ mAb treatment (Fig. 2 A). These results establish a key role for LTα1β2 in maintaining normal chemokine expression. Although the lesser effect of the antibody treatment compared with LTβR-Ig treatment (Fig. 2 A) suggests that LIGHT might also contribute, the results may equally be explained by the mAb causing less complete inhibition of LTα1β2 function, as has been observed in in vitro studies (40). To explore further the relationship noted in the mutant mice between chemokine deficiency and loss of follicular organization, spleen sections from LTβR-Ig–treated mice were stained for B cell markers as well as FDCs and marginal zone markers. As observed previously (36), expression of mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule (MAdCAM)-1 and FDC markers were reduced after 1 wk of treatment and were undetectable by 2 wk, whereas loss of the marginal metallophilic macrophage (MMM) marker MOMA1 was more gradual (data not shown). Changes in B cell follicular organization were also observed after 1 wk of treatment (Fig. 2 C) and were maximal after 2 wk of treatment (Fig. 2 C), paralleling the decrease in BLC expression. These results establish a constitutive requirement for LTα1β2 in maintaining normal levels of BLC and SLC. The more modest decrease in BLC and SLC expression in LTβR-Ig–treated mice compared with LTα−/− or LTβ−/− mice could reflect incomplete blocking of LTα1β2 function but is also consistent with a role for LTα1β2 in development that does not continue in the adult mouse.

Figure 2.

Decreased BLC expression in mice treated with LTα1β2 antagonists. (A) Relative chemokine mRNA levels as determined by Northern blot and PhosphorImager analysis of total spleen RNA from mice treated for the indicated time period with LTβR-Ig (100 μg/wk, i.p.) or hamster anti-LTβ mAb (200 μg/wk, i.p.). Control mice for the LTβR-Ig treatment were treated with equal doses of LFA3-Ig, and controls for the mAb treatment were given hamster anti-KLH mAb. Each sample was corrected for differences in RNA loading using the value obtained with an EF-1α probe. Chemokine expression as percentage of control was calculated by dividing the corrected value for each treated mouse with the mean corrected value for the controls at that time point. Data from individual mice are shown as filled circles and means as shaded bars. (B) Relative chemokine mRNA levels in spleen and mesenteric lymph nodes from animals treated for 2 wk with LTβR-Ig (100 μg/wk, i.p.). Calculations were made as in A. (C) Disrupted follicular organization in LTβR-Ig–treated mice. Spleen tissue from mice treated with LFA3-Ig for 2 wk or LTβR-Ig for 1 or 2 wk was sectioned and stained with B220 (dark gray) to detect B cells.

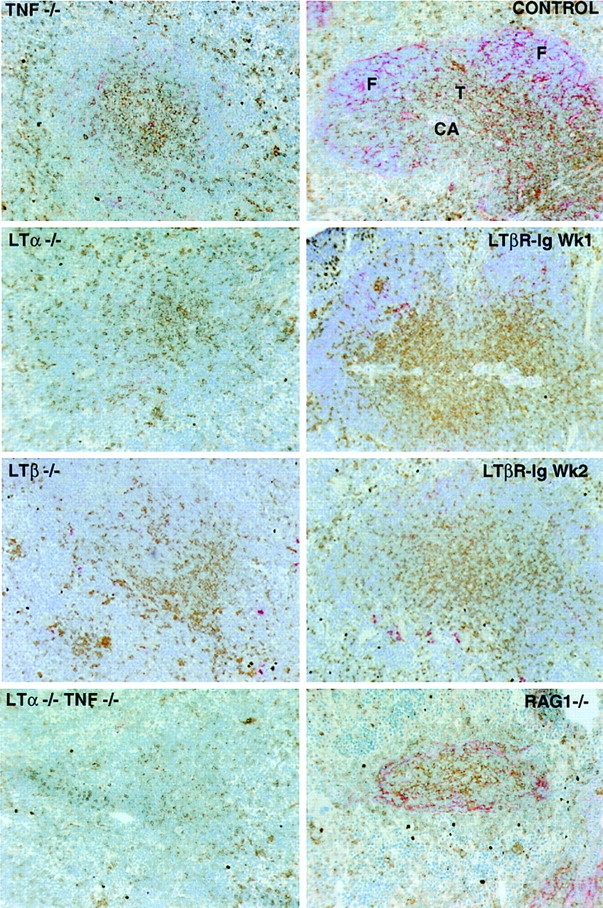

TNF- and LTα1β2-dependent Stromal Cells in Follicles and T Zone.

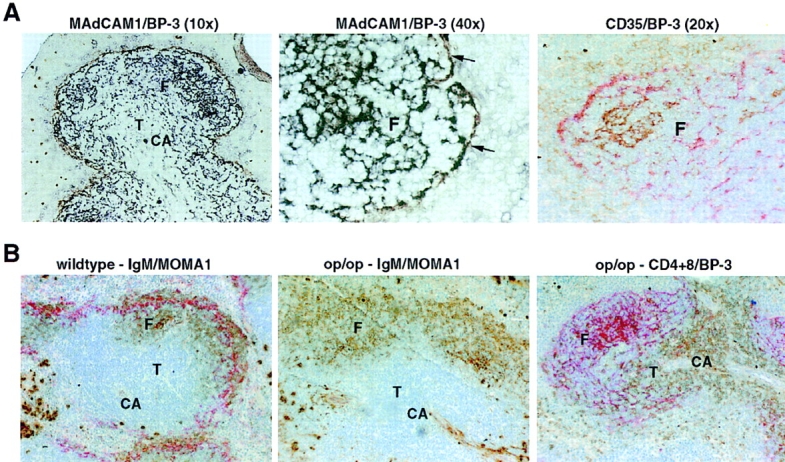

The above experiments demonstrated that TNF, LTα, and LTβ are required for normal expression of the chemokines BLC and SLC by stromal cells in the spleen. Several studies have established that the organization of FDCs is disrupted in TNF-, LTα-, and LTβ-deficient mice (1), indicating that the cell type normally producing BLC might be disrupted. However, disruption of FDC organization could not account for the decreased SLC expression, since FDCs do not extend into the T zone. To test whether changes in addition to reduced SLC expression could be detected in T zone stromal cells, we examined expression of BP-3, a marker for an extensive network of stromal cells in both the T zone and follicles (38, 42). Strikingly, the network of BP-3+ cells was greatly reduced in both the B and T zones of TNF- and TNFR1-deficient mice (Fig. 3, and data not shown) and was undetectable in LTα- and LTβ-deficient mice except for a small number of cells with altered morphology that were occasionally observed (Fig. 3). The disruption of BP-3–expressing stromal cells in both TNF- and LTα/β-deficient spleens appeared more severe than in lymphocyte-deficient (RAG-1−/−) spleens (Fig. 3). BP-3 expression in T zone and follicles was also markedly disrupted after 1 wk of treatment with LTβR-Ig or anti-LTβ antibody and was almost undetectable after 2 wk of treatment (Fig. 3, and data not shown). This period of treatment is also sufficient to disrupt staining for MAdCAM-1 and FDC markers (36, 43). To determine the relationship between BP-3–expressing cells in follicles and the cell types previously defined as TNF- and LTα and β–dependent, sections from wild-type mice were double stained for MAdCAM-1 or CR1 (CD35) and BP-3 (Fig. 4 A). BP-3–expressing cells in the outer follicle appeared to line the marginal sinus, and in some cases these cells costained for MAdCAM-1 (Fig. 4 A). Many of the BP-3+ cells located in the center of the follicle costained with CD35 (Fig. 4 A), whereas BP-3+ cells in other parts of the follicle, especially cells near the marginal sinus, were CD35-low or -negative (Fig. 4 A). Therefore, the BP-3– expressing stromal cell population includes T zone stromal cells (Fig. 3 and Fig. 4 A), FDCs, marginal sinus lining cells, and follicular stromal cells that are low or negative for FDC markers (Fig. 4 A). The severe disruption of BP-3 expression in the mutant mice, together with the reduced BLC and SLC expression and the loss of FDCs, indicates that TNF, LTα, and LTβ have a broad role in inducing and maintaining stromal cell integrity in T zones and B zones of lymphoid tissues.

Figure 3.

Disruption of BP-3 expression in follicles and T zone of TNF-, TNFR1-, LTα-, and LTβ-deficient mice and LTβR-Ig–treated mice. Spleen tissue from the indicated mutant mice or mice treated with soluble LTβR-Ig for 1–2 wk or from a wild-type control was sectioned and stained to detect T cells (combination of anti-CD4 and anti-CD8; brown) and BP-3 (red). The CD4 and CD8 staining in the RAG-1−/− spleen does not represent T cells, as there was no staining for CD3 (not shown). CA, central arteriole; F, follicle; T, T zone. Original magnification: ×10.

Figure 4.

Costaining of BP-3+ stromal cell subsets with MAdCAM-1 and CD35 (CR1) and normal follicular organization and BP-3 expression in op/op mice. (A) Spleen tissue from wild-type mice was sectioned and stained to detect MAdCAM-1 (brown) and BP-3 (black; left and center panels), or CD35 (brown) and BP-3 (red; right panel). Arrows in center panel indicate MAdCAM-1 and BP-3 double-stained cells. The faint brown CD35 staining corresponds to CD35high marginal zone B cells and CD35low follicular B cells. Original magnification: ×10, ×20, or ×40, as indicated. (B) Spleen tissue from wild-type (left) or op/op (center and right) mice was sectioned and stained to detect: IgM (brown) and MOMA1 (red; left and center), or CD4 and CD8 (brown) and BP-3 (red; right). Note the lack of MOMA1+ MMM staining in the op/op mutant. Original magnification: ×10. CA, central arteriole; F, follicle; T, T zone.

MZMs Are Not Required for BLC Production.

In addition to defects in FDCs, MAdCAM-1+ cells, and BP-3+ cells, LTα- and LTβ-deficient mice also lack MZMs and MMMs (1, 11, 12). To test the possibility that the deficiency in these macrophage populations in LTα−/− and LTβ−/− mice contributed to the greatly reduced BLC expression and loss of follicular organization, we characterized spleens from op/op mice, a strain that is deficient in MMMs and MZMs due to a mutation in the colony stimulating factor 1 gene (44, 45). Organization of B cell follicles appeared normal in op/op spleen (Fig. 4 B), and BLC expression was not reduced (Fig. 5). Expression of BP-3, MAdCAM-1, and CD35 was also not disrupted (Fig. 4 B, and data not shown). These findings demonstrate that MZMs and MMMs do not make a significant contribution to the constitutive production of BLC, and also establish that these cells are not required as a source of TNF or LTα1β2 to maintain BLC expression or follicular organization.

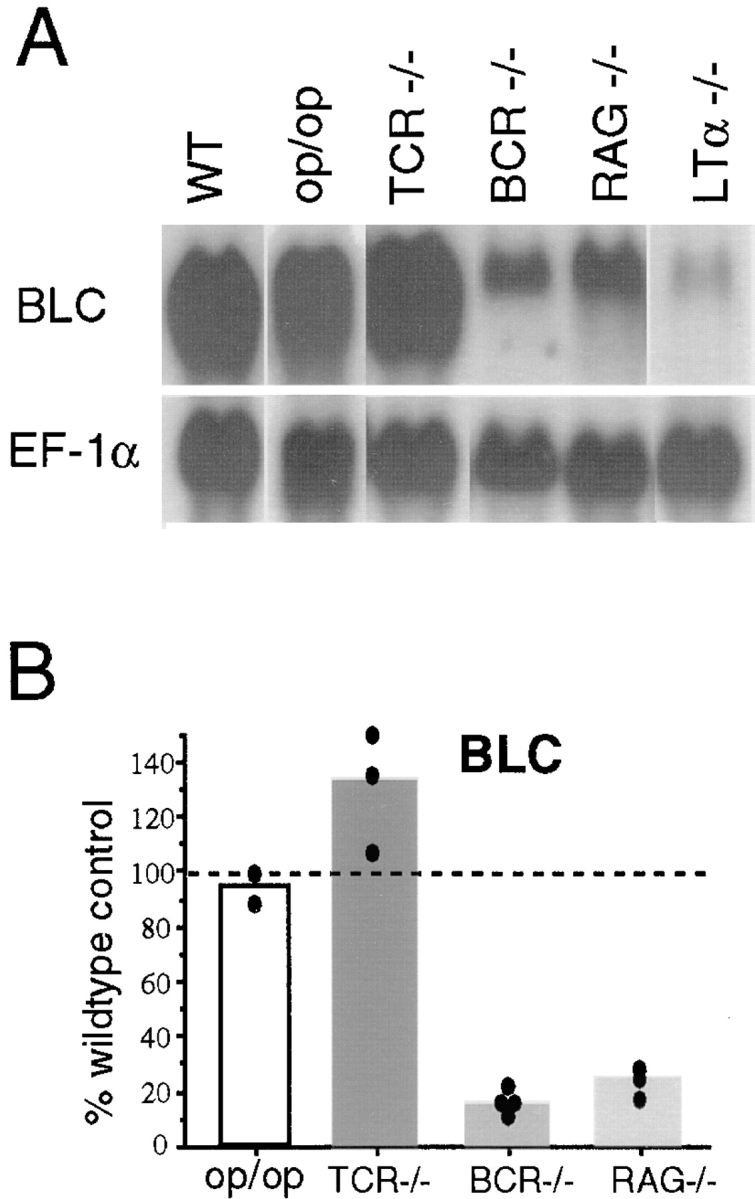

Figure 5.

MZM independence and B lymphocyte dependence of BLC expression. (A) Northern blot analysis of total RNA isolated from spleen tissue of op/op, TCR-β−/−δ−/− (TCR−/−), μMT (BCR−/−), and RAG-1−/− mice, probed to detect expression of BLC and EF-1α. (B) Relative chemokine mRNA levels as determined by PhosphorImager analysis of the Northern blot shown in A and additional blots, after correcting for differences in RNA loading from the corresponding EF-1α value.

Normal Expression of BLC Is Dependent on B Cells.

Re cent studies have demonstrated that B lymphocytes are an essential source of membrane LTα1β2 for establishing FDC networks and follicular organization (46, 47). However, mice congenitally deficient in LTα have a more severe disruption of lymphoid compartmentalization than mice lacking only in lymphocyte LTα expression, indicating that there is also a nonlymphocyte source of LTα (47, 48). To determine whether either or both sources of LTα were required for induction of BLC, chemokine expression levels in RAG-1−/−, B cell receptor (BCR)−/−, and TCR−/− mice were compared with levels in LTα−/− animals. BLC expression was reduced approximately fivefold in spleens from lymphocyte-deficient (RAG-1−/−) and B cell–deficient (μMT) mice, but were not reduced in T cell–deficient (TCR-β−/−δ−/−) mice (Fig. 5), demonstrating that B cells are important for induction of BLC expression, presumably providing LTα1β2 and possibly also TNF. However, BLC levels in RAG-1−/− and BCR−/− mice were not reduced to the extent of LTα−/− or LTβ−/− mice (Fig. 5, and see Fig. 1), indicating that some BLC expression in the spleen is induced by LTα/β-expressing cells other than B and T lymphocytes.

Discussion

These studies provide new insight into the mechanism by which TNF and LTα/β promote normal compartmentalization of lymphocytes in the white pulp cords of the spleen. The findings extend the previously defined requirement for TNF and LTα/β in the development and function of follicular stromal cells to also include stromal cells in the splenic T zone. The results demonstrate that a key function of the LTα/β- and TNF-dependent stromal cells is constitutive production of chemokines that strongly attract resting lymphocytes, and they suggest that these chemokines function with other properties of the stroma to compartmentalize cells into follicles and T zones.

The chemokine receptor CXCR5 is expressed by all mature B cells and is the only known receptor for BLC, an efficacious attractant of resting B cells (13, 15, 16). Since loss of CXCR5 is sufficient to disrupt organization of splenic follicles (5), it is reasonable to suggest that the greatly reduced expression of BLC in TNF-, TNFR1-, LTα-, and LTβ-deficient mice directly contributes to the disrupted organization of splenic follicles in these animals. Polarized follicles also fail to form in lymph nodes of TNF-deficient mice and in the nodes that develop under some conditions in LT-deficient mice (6, 11, 12, 37, 49). The finding that BLC expression is reduced in mesenteric lymph nodes of LTβR-Ig–treated mice indicates that LTα/β plays a role in directing BLC expression in lymph nodes. However, whether BLC is likely to contribute to the organization of B cells into lymph node follicles is presently unclear, since CXCR5 does not appear to be required (5).

SLC and ELC both stimulate cells through CCR7, a receptor expressed by T and B lymphocytes, and these chemokines are the most efficacious attractants of T cells so far described (21, 25, 27, 50). We propose that the severe reduction in T zone SLC expression in LTα/β-deficient mice directly contributes to the loss of normal T cell compartmentalization in these animals. Maturing DCs upregulate CCR7 and have been suggested to migrate to lymphoid tissues in response to CCR7 ligands (51), making it possible that the decrease in SLC also leads to reduced accumulation of mature DCs in the T zone. Consistent with this possibility, lymph nodes developing in mice with reduced LTα levels have threefold fewer DCs than controls (52), and we have observed a similar decrease in DC frequency in LTα-deficient mouse spleens (our unpublished observations). Reduced DC accumulation may be at least partially responsible for the decreased expression of ELC, a chemokine made by T zone DCs (27). The lowered ELC levels are likely to exacerbate the effect of SLC deficiency and contribute to the loss of T zone organization. TNF and TNFR1 are also required for maximal SLC and ELC expression. However, mice deficient in TNF or TNFR1 do continue to express significant amounts of SLC and ELC, and this is consistent with the relatively unaffected T zone organization in these mutant animals (3, 4, 6, 53). The generally greater reduction of chemokine expression in TNF-deficient compared with TNFR1-deficient mice should not be due to background gene effects, since all the animals were generated on the C57BL/6 background; a more likely possibility is that TNFR2 transmits some of the TNF signals necessary for chemokine expression. In support of this possibility is the finding that Langerhans cell migration to lymph nodes is depressed in TNFR2-deficient mice (54). Interestingly, during the analysis of several TNFR1-deficient mice that had been housed in a conventional animal facility, we found that whereas BLC and SLC levels remained depressed, ELC expression was equal to the wild-type controls (our unpublished observations). These observations are similar to other findings indicating that some of the nonredundant functions of TNF in the resting state can be overcome during an immune response (43).

The deficiency of FDCs in LT- and TNF-deficient mice has been well characterized (1). Ultrastructural studies have demonstrated that FDCs are part of a broader network of follicular stromal cells (55), and using the molecule BP-3 as a marker it has been possible to show that this more extensive stromal cell network is also LT and TNF dependent (see Fig. 3). Elegant bone marrow chimera and adoptive transfer experiments have established that FDC development requires TNFR1 and LTβR expression by the follicular stroma and cytokine (LT and TNF) expression by hematopoietic cells, in particular B cells (39, 46–48). The necessity for B cells in the maximal expression of BLC (see Fig. 5) is consistent with these results and suggests that a feedback loop exists which helps to keep the number of BLC producing follicular stromal cells in proportion to the number of B cells. The more depressed BLC expression in LTα- and LTβ-deficient mice than in B cell–deficient animals is also in agreement with studies showing that B cells cannot be the sole source of LTα/β for follicle formation (47, 48). Perhaps the LTα/β-expressing CD4+CD3− cells that enter lymphoid tissues early in development (56) induce stromal cells to express BLC. Requirements for development of T zone stromal cells have been less well characterized than for FDCs, but our results indicate they are similar in being TNF and LTα/β dependent. Experiments are ongoing to address whether T cells, B cells, or other cell types must express TNF or LTα/β for induction of normal SLC expression. At this stage, it has not been possible to determine whether LT and TNF work directly to induce chemokine expression or whether they function further upstream, inducing and maintaining the development and viability of chemokine-expressing stromal cells. Although treatment of adult mice with soluble LTβR-Ig leads within 1 wk to decreased expression of BLC and SLC, the treatment also leads to rapid disruption of stromal cells as defined by a variety of markers (36; and see Fig. 3). Future studies must define in more detail the subpopulations of LT- and TNF-dependent stromal cells that express BLC and SLC and characterize the signaling pathways that control chemokine expression.

The studies in this report have established a major role for LTα/β, and a lesser but significant role for TNF, in promoting the function of chemokine-expressing stromal cells in lymphoid areas of the spleen. Analysis of lymph nodes from LTβR-Ig–treated mice has provided initial evidence that LTα/β is also required for normal chemokine expression in lymph nodes. Given the requirement for LTα/β and TNF in normal organization of all peripheral lymphoid tissues, as well as the ability of ectopically expressed LTα to promote accumulation of B and T lymphocytes in lymphoid aggregates (57), it appears likely that LTα/β and TNF function broadly in regulating lymphoid tissue chemokine expression. Accumulation at nonlymphoid sites of cells in follicle- and T zone–like structures also typifies several human diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis and type I diabetes, and the possibility that locally produced LT and TNF induce the development of BLC- and SLC-expressing stromal cells deserves investigation.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jacques Peschon (Immunex Corp.) for generously providing TNFR1-deficient spleens and mice, and acknowledge the assistance of Elena Foulcher (Centenary Institute) for collection and preparation of tissues from the cytokine gene–targeted mice. We thank the Biogen LTβ project team for the LTβR-Ig.

Abbreviations used in this paper

BCR

B cell receptor

BLC

B lymphocyte chemoattractant

DC

dendritic cell

EBI-1

Epstein Barr virus–induced molecule 1

ELC

EBI-1 ligand chemokine

EF

elongation factor

ES

embryonic stem

FDC

follicular DC

LT

lymphotoxin

MAdCAM

mucosal addressin cell adhesion molecule

MMM

marginal metallophilic macrophage

MZM

marginal zone macrophage

RAG

recombination activating gene

SDF

stromal cell–derived factor

SLC

secondary lymphoid tissue chemokine

Footnotes

J.D. Sedgwick, H. Korner, and D.S. Riminton were supported by grants from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia and the National Multiple Sclerosis Society of Australia. J.G. Cyster is a Pew Scholar in the biomedical sciences. This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grant AI40098 to J.G. Cyster and by Howard Hughes Medical Institute grant 76296-549901 to the University of California San Francisco School of Medicine.

J.D. Sedgwick's present address is DNAX Research Institute, 901 California Ave., Palo Alto, CA 94304-1104.

References

- 1.Matsumoto M, Fu YX, Molina H, Chaplin DD. Lymphotoxin-alpha-deficient and TNF receptor-I- deficient mice define developmental and functional characteristics of germinal centers. Immunol Rev. 1997;156:137–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb00965.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Futterer A, Mink K, Luz A, Kosco-Vilbois MH, Pfeffer K. The lymphotoxin β receptor controls organogenesis and affinity maturation in peripheral lymphoid tissues. Immunity. 1998;9:59–70. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80588-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pasparakis M, Alexopoulou L, Episkopou V, Kollias G. Immune and inflammatory responses in TNF alpha–deficient mice: a critical requirement for TNF alpha in the formation of primary B cell follicles, follicular dendritic cell networks and germinal centers, and in the maturation of the humoral immune response. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1397–1411. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.4.1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neumann B, Machleidt T, Lifka A, Pfeffer K, Vestweber D, Mak TW, Holzmann B, Kronke M. Crucial role of 55-kilodalton TNF receptor in TNF-induced adhesion molecule expression and leukocyte organ infiltration. J Immunol. 1996;156:1587–1593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Forster R, Mattis AE, Kremmer E, Wolf E, Brem G, Lipp M. A putative chemokine receptor, BLR1, directs B cell migration to defined lymphoid organs and specific anatomic compartments of the spleen. Cell. 1996;87:1–20. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81798-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Korner H, Cook M, Riminton DS, Lemckert FA, Hoek RM, Ledermann B, Kontgen F, Fazekas de St. Groth B, Sedgwick JD. Distinct roles for lymphotoxin- alpha and tumor necrosis factor in organogenesis and spatial organization of lymphoid tissue. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:2600–2609. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830271020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ware CF, VanArsdale TL, Crowe PD, Browning JL. The ligands and receptors of the lymphotoxin system. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1995;198:175–218. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-79414-8_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rennert PD, Browning JL, Mebius R, Mackay F, Hochman PS. Surface lymphotoxin α/β complex is required for the development of peripheral lymphoid organs. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1999–2006. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.5.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ettinger R, Browning JL, Michie SA, van Ewijk W, McDevitt HO. Disrupted splenic architecture, but normal lymph node development in mice expressing a soluble lymphotoxin-beta receptor-IgG1 fusion protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13102–13107. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Togni PD, Goellner J, Ruddle NH, Streeter PR, Fick A, Mariathasan S, Smith SC, Carlson R, Shornick LP, Strauss-Schoenberger J, et al. Abnormal development of peripheral lymphoid organs in mice deficient in lymphotoxin. Science. 1994;264:703–707. doi: 10.1126/science.8171322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koni PA, Sacca R, Lawton P, Browning JL, Ruddle NH, Flavell RA. Distinct roles in lymphoid organogenesis for lymphotoxins alpha and beta revealed in lymphotoxin beta-deficient mice. Immunity. 1997;6:491–500. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80292-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alimzhanov MB, Kuprash DV, Kosco-Vilbois MH, Luz A, Turetskaya RL, Tarakhovsky A, Rajewsky K, Nedospasov SA, Pfeffer K. Abnormal development of secondary lymphoid tissues in lymphotoxin beta-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9302–9307. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.17.9302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forster R, Emrich T, Kremmer E, Lipp M. Expression of the G-protein-coupled receptor BLR1 defines mature, recirculating B cells and a subset of T-helper memory cells. Blood. 1994;84:830–840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmidt KN, Hsu CW, Griffin CT, Goodnow CC, Cyster JG. Spontaneous follicular exclusion of SHP1-deficient B cells is conditional on the presence of competitor wild-type B cells. J Exp Med. 1998;187:929–937. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.6.929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gunn MD, Ngo VN, Ansel KM, Ekland EH, Cyster JG, Williams LT. A B-cell homing chemokine made in lymphoid follicles activates Burkitt's lymphoma receptor-1. Nature. 1998;391:799–803. doi: 10.1038/35876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Legler DF, Loetscher M, Roos RS, Clark-Lewis I, Baggiolini M, Moser B. B cell–attracting chemokine 1, a human CXC chemokine expressed in lymphoid tissues, selectively attracts B lymphocytes via BLR1/CXCR5. J Exp Med. 1998;187:655–660. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.4.655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagasawa T, Kikutani H, Kishimoto T. Molecular cloning and structure of a pre-B-cell growth-stimulating factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:2305–2309. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.6.2305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tashiro K, Tada H, Heilker R, Shirozu M, Nakano T, Honjo T. Signal sequence trap: a cloning strategy for secreted proteins and type I membrane proteins. Science. 1993;261:600–603. doi: 10.1126/science.8342023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bleul CC, Fuhlbrigge RC, Casasnovas JM, Aiuti A, Springer TA. A highly efficacious lymphocyte chemoattractant, stromal cell–derived factor 1 (SDF-1) J Exp Med. 1996;184:1101–1109. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.3.1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nagira M, Imai T, Hieshima K, Kusuda J, Ridanpaa M, Takagi S, Nishimura M, Kakizaki M, Nomiyama H, Yoshie O. Molecular cloning of a novel human CC chemokine secondary lymphoid-tissue chemokine that is a potent chemoattractant for lymphocytes and mapped to chromosome 9p13. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:19518–19524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.31.19518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gunn MD, Tangemann K, Tam C, Cyster JG, Rosen S, Williams LT. A chemokine expressed in lymphoid high endothelial venules promotes the adhesion and chemotaxis of naive T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:258–263. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.1.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hedrick JA, Zlotnik A. Identification and characterization of a novel beta chemokine containing six conserved cysteines. J Immunol. 1997;159:1589–1593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hromas R, Kim CH, Klemsz M, Krathwohl M, Fife K, Cooper S, Schnizlein-Bick C, Broxmeyer HE. Isolation and characterization of Exodus-2, a novel C-C chemokine with a unique 37-amino acid carboxyl-terminal extension. J Immunol. 1997;159:2554–2558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanabe S, Lu Z, Luo Y, Quackenbush EJ, Berman MA, Collins-Racie LA, Mi S, Reilly C, Lo D, Jacobs KA, Dorf ME. Identification of a new mouse β-chemokine, thymus-derived chemotactic agent 4, with activity on T lymphocytes and mesangial cells. J Immunol. 1997;159:5671–5679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoshida R, Imai T, Hieshima K, Kusuda J, Baba M, Kitaura M, Nishimura M, Kakizaki M, Nomiyama H, Yoshie O. Molecular cloning of a novel human CC chemokine EBI1-ligand chemokine that is a specific functional ligand for EBI1, CCR7. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:13803–13809. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.21.13803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rossi DL, Vicari AP, Franz-Bacon K, McClanahan TK, Zlotnik A. Identification through bioinformatics of two new macrophage proinflammatory human chemokines: MIP-3α and MIP-3β. J Immunol. 1997;158:1033–1036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ngo VN, Tang LH, Cyster JG. EBI-1 ligand chemokine is expressed by dendritic cells in lymphoid tissues and strongly attracts naive T cells and activated B cells. J Exp Med. 1998;188:181–191. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.1.181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim CH, Pelus LM, White JR, Applebaum E, Johanson K, Broxmeyer HE. CK beta-11/macrophage inflammatory protein-3 beta/EBI1-ligand chemokine is an efficacious chemoattractant for T and B cells. J Immunol. 1998;160:2418–2424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goodnow CC, Cyster JG. Lymphocyte homing: the scent of a follicle. Curr Biol. 1997;7:R219–R222. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00105-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Riminton DS, Korner H, Strickland DH, Lemckert FA, Pollard JD, Sedgwick JD. Challenging cytokine redundancy: inflammatory cell movement and clinical course of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis are normal in lymphotoxin-deficient, but not tumor necrosis factor– deficient mice. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1517–1528. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.9.1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lemckert FA, Sedgwick JD, Korner H. Gene targeting in C57BL/6 ES cells. Successful germ line transmission using recipient BALB/c blastocysts developmentally matured in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:917–918. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.4.917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peschon JJ, Torrance DS, Stocking KL, Glaccum MB, Otten C, Willis CR, Charrier K, Morrissey PJ, Ware CB, Mohler KM. TNF receptor-deficient mice reveal divergent roles for p55 and p75 in several models of inflammation. J Immunol. 1998;160:943–952. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Force WR, Walter BN, Hession C, Tizard R, Kozak CA, Browning JL, Ware CF. Mouse lymphotoxin-β receptor. Molecular genetics, ligand binding, and expression. J Immunol. 1995;155:5280–5288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Browning JL, Sizing ID, Lawton P, Bourdon PR, Rennert PD, Majeau GR, Ambrose CM, Hession C, Miatkowski K, Griffiths DA, et al. Characterization of lymphotoxin-alpha beta complexes on the surface of mouse lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1997;159:3288–3298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rennert PD, Browning JL, Hochman PS. Selective disruption of lymphotoxin ligands reveals a novel set of mucosal lymph nodes and unique effects on lymph node cellular organization. Int Immunol. 1997;9:1627–1639. doi: 10.1093/intimm/9.11.1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mackay F, Majeau GR, Lawton P, Hochman PS, Browning JL. Lymphotoxin but not tumor necrosis factor functions to maintain splenic architecture and humoral responsiveness in adult mice. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:2033–2042. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rennert PD, James D, Mackay F, Browning JL, Hochman PS. Lymph node genesis is induced by signaling through the lymphotoxin β receptor. Immunity. 1998;9:71–79. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80589-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McNagny KM, Bucy RP, Cooper MD. Reticular cells in peripheral lymphoid tissues express the phosphatidylinositol-linked BP-3 antigen. Eur J Immunol. 1991;21:509–515. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830210238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cook MC, Korner H, Riminton DS, Lemckert FA, Hasbold J, Amesbury M, Hodgkin PD, Cyster JG, Sedgwick JD, Basten A. Generation of splenic follicle structure and B cell movement in tumor necrosis factor–deficient mice. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1503–1510. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.8.1503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mackay F, Bourdon PR, Griffiths DA, Lawton P, Zafari M, Sizing ID, Miatkowski K, Ngam-ek A, Benjamin CD, Hession C, et al. Cytotoxic activities of recombinant soluble murine lymphotoxin-alpha and lymphotoxin-alpha beta complexes. J Immunol. 1997;159:3299–3310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mauri DN, Ebner R, Montgomery RI, Kochel KD, Cheung TC, Yu GL, Ruben S, Murphy M, Eisenberg RJ, Cohen GH, et al. LIGHT, a new member of the TNF superfamily, and lymphotoxin alpha are ligands for herpesvirus entry mediator. Immunity. 1998;8:21–30. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80455-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dong C, Wang J, Neame P, Cooper MD. The murine BP-3 gene encodes a relative of the CD38/NAD glycohydrolase family. Int Immunol. 1994;6:1353–1360. doi: 10.1093/intimm/6.9.1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mackay F, Browning JL. Inhibition of follicular dendritic cell function in vivo. Nature. 1998;395:26–27. doi: 10.1038/25630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Witmer-Pack MD, Hughes DA, Schuler G, Lawson L, McWilliam A, Inaba K, Steinman RM, Gordon S. Identification of macrophages and dendritic cells in the osteopetrotic (op/op)mouse. J Cell Sci. 1993;104:1021–1029. doi: 10.1242/jcs.104.4.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cecchini MG, Dominguez MG, Mocci S, Wetterwald A, Felix R, Fleisch H, Chisholm O, Hofstetter W, Pollard JW, Stanley ER. Role of colony stimulating factor-1 in the establishment and regulation of tissue macrophages during postnatal development of the mouse. Development (Camb) 1994;120:1357–1372. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.6.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fu YX, Huang G, Wang Y, Chaplin DD. B lymphocytes induce the formation of follicular dendritic cell clusters in a lymphotoxin α–dependent fashion. J Exp Med. 1998;187:1009–1018. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.7.1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gonzalez M, Mackay F, Browning JL, Kosco-Vilbois MH, Noelle RJ. The sequential role of lymphotoxin and B cells in the development of splenic follicles. J Exp Med. 1998;187:997–1007. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.7.997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fu YX, Molina H, Matsumoto M, Huang G, Min J, Chaplin DD. Lymphotoxin-alpha (LTα) supports development of splenic follicular structure that is required for IgG responses. J Exp Med. 1997;185:2111–2120. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.12.2111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pasparakis M, Alexopoulou L, Grell M, Pfizenmaier K, Bluethmann H, Kollias G. Peyer's patch organogenesis is intact yet formation of B lymphocyte follicles is defective in peripheral lymphoid organs of mice deficient for tumor necrosis factor and its 55-kDa receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6319–6323. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yoshida R, Nagira M, Kitaura M, Imagawa N, Imai T, Yoshie O. Secondary lymphoid tissue chemokine is a functional ligand for the CC chemokine receptor CCR7. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:7118–7122. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.12.7118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dieu M-C, Vanbervliet B, Vicari A, Bridon J-M, Oldham E, Ait-Yahia S, Briere F, Zlotnik A, Lebecque S, Caux C. Selective recruitment of immature and mature dendritic cells by distinct chemokines expressed in different anatomic sites. J Exp Med. 1998;188:373–386. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.2.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sacca R, Turley S, Soong L, Mellman I, Ruddle NH. Transgenic expression of lymphotoxin restores lymph nodes to lymphotoxin-alpha-deficient mice. J Immunol. 1997;159:4252–4260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marino MW, Dunn A, Grail D, Inglese M, Noguchi Y, Richards E, Jungbluth A, Wada H, Moore M, Williamson B, et al. Characterization of tumor necrosis factor-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:8093–8098. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.15.8093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang B, Fujisawa H, Zhuang L, Kondo S, Shivji GM, Kim CS, Mak TW, Sauder DN. Depressed Langerhans cell migration and reduced contact hypersensitivity response in mice lacking TNF receptor p75. J Immunol. 1997;159:6148–6155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Heusermann U, Zurborn KH, Schroeder L, Stutte HJ. The origin of the dendritic reticulum cell. An experimental enzyme-histochemical and electron microscopic study on the rabbit spleen. Cell Tissue Res. 1980;209:279–294. doi: 10.1007/BF00237632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mebius RE, Rennert P, Weissman IL. Developing lymph nodes collect CD4+CD3− LTβ+ cells that can differentiate to APC, NK cells, and follicular cells but not T or B cells. Immunity. 1997;7:493–504. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80371-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kratz A, Campos-Neto A, Hanson MS, Ruddle NH. Chronic inflammation caused by lymphotoxin is lymphoid neogenesis. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1461–1472. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]