Role of p75 Neurotrophin Receptor in the Neurotoxicity by β-amyloid Peptides and Synergistic Effect of Inflammatory Cytokines (original) (raw)

Abstract

The neurodegenerative changes in Alzheimer's disease (AD) are elicited by the accumulation of β-amyloid peptides (Aβ), which damage neurons either directly by interacting with components of the cell surface to trigger cell death signaling or indirectly by activating astrocytes and microglia to produce inflammatory mediators. It has been recently proposed that the p75 neurotrophin receptor (p75NTR) is responsible for neuronal damage by interacting with Aβ. By using neuroblastoma cell clones lacking the expression of all neurotrophin receptors or engineered to express full-length or various truncated forms of p75NTR, we could show that p75NTR is involved in the direct signaling of cell death by Aβ via the function of its death domain. This signaling leads to the activation of caspases-8 and -3, the production of reactive oxygen intermediates and the induction of an oxidative stress. We also found that the direct and indirect (inflammatory) mechanisms of neuronal damage by Aβ could act synergistically. In fact, TNF-α and IL-1β, cytokines produced by Aβ-activated microglia, could potentiate the neurotoxic action of Aβ mediated by p75NTR signaling. Together, our results indicate that neurons expressing p75NTR, mostly if expressing also proinflammatory cytokine receptors, might be preferential targets of the cytotoxic action of Aβ in AD.

Keywords: p75NTR, cell death, human neuroblastoma cells, cytokines, Alzheimer's disease

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD)* is characterized by progressive loss of neurons, formation of fibrillary tangles within neurons, and numerous plaques in affected brain regions. According to the “β-amyloid cascade hypothesis,” the key pathogenetic event responsible for the degenerative changes in neurons is the excessive formation and/or accumulation of fibrillar β-amyloid peptides (Aβ), a set of 39–43 amino acid (aa) peptides derived from the cleavage by β- and γ-secretases of a membrane glycoprotein, named β-amyloid precursor protein (APP) (1–3). Aβ are neurotoxic in vitro_,_ and this cytotoxicity correlates with their β-sheet structure and fibrillar state (4–6). However recent findings have shown that not only fibrils, but even protofibrils and small soluble oligomers of Aβ can be neurotoxic (7).

Two main mechanisms have been postulated to be responsible for the neurotoxicity by Aβ: (i) Aβ may interact with components of cell membranes and thus injure neurons directly (4–8) and/or enhance the vulnerability of neurons by a variety of common insults, such as excitotoxicity, hypoglycemia, or peroxidative damage (9); (ii) Aβ may damage neurons indirectly by activating microglia and astrocytes to produce toxic and inflammatory mediators, such as nitric oxide (NO), cytokines, and reactive oxygen intermediates (ROI) (10–16).

The mechanisms by which Aβ interact with the cell surface remain to be clarified. Besides interacting with phospholipids of cellular plasmamembrane and forming selective cation channels and/or disrupting membrane integrity by virtue of their lipophilic nature (17–19), Aβ bind to a variety of cell surface receptors, such as scavenger receptors (13) and NH2-formylpeptide receptor 2 in microglia (20), advanced glycation end products receptors (RAGE) in neurons and microglia (21), serpin-enzyme complex receptor (22), α-7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (α7NAChR) (23), neurotrophin receptor p75 (p75NTR) (24–25), amyloid precursor protein (APP) (26) and a β-amyloid binding protein (BBP) containing a G protein-coupling module (27) in neurons. Some of these binding interactions (21, 23–27) have been correlated with the direct neurotoxicity of Aβ. The multiplicity of the receptors involved raises the problem of the specificity of their interactions with Aβ and active roles in signaling cell death.

p75NTR binds NGF and the other neurotrophins (28) and belongs to the family of death receptors (29, 30). In recent years, several groups have shown that p75NTR mediates both ligand-dependent and ligand-independent apoptosis (31–37) including that by Aβ (24, 25). Furthermore, the cholinergic neurons of the basal forebrain, which are early and severely affected in AD, express high levels of p75NTR, whereas the cholinergic neurons of the brainstem, which do not express p75NTR, remain undamaged (38– 40). However, despite the data showing that p75NTR binds Aβ (24, 25), it is not known whether this receptor directly partakes to the cell death signaling or functions as a cellular anchor for the interaction between Aβ and the cell membrane, an interaction that would allow for the toxic activity of Aβ independently of any p75NTR activation.

p75NTR is endowed with an independent signaling capacity (33, 41, 42). The cytoplasmic region of p75NTR contains a putative death domain (DD) and a juxtamembrane intracellular domain (JICD). The DD exhibits similarities and differences with respect to the DDs of TNFR and Fas (43–45), and these structural differences would result in different mechanisms of recruitment and signaling by the p75NTR DD with regard to the self association of receptor moieties and their interaction with other cytoplasmic factors (46–49). The JICD would be able to interact with cytoplasmic adaptor proteins and to signal cell death (46, 49–52). Notwithstanding these findings, the exact functions of the two regions of the intracellular domain of p75NTR remain to be understood.

In this work we have addressed two problems. On the basis of the previous findings by others that p75NTR is involved in the neurotoxicity by Aβ (24, 25) we have investigated the mechanism of this involvement. To this purpose, Aβ were tested for the neuronal toxicity on a SK-N-BE neuroblastoma cell line devoid of all neurotrophin receptors, and on several SK-N-BE derived cell clones either expressing the full-length or truncated forms of p75NTR. Our results were that p75NTR plays a direct role in cell death by Aβ through the signaling function of the DD, the activation of caspase-8 and oxidative stress. The second problem concerns the possibility of a synergistic cooperation between the direct and indirect (inflammatory) mechanisms of neuronal damage by Aβ. The results obtained indicate that this is the case because TNF-α and IL-1β, cytokines produced by Aβ-activated glial cells, could potentiate the p75NTR-mediated direct neurotoxic action of Aβ.

Materials and Methods

Aβ-Peptides.

Aβ(25–35), Aβ(1–40), Aβ(1–42), and Aβ(35–25) were from Bachem AG. Aβ(25–35) was dissolved at 1.5 mM in PBS, Aβ(1–40) at 1.5 mM in double-distilled water to be next diluted at 250 μM in PBS, and Aβ(1–42) at 500 μM in double-distilled water. Fibrillogenesis by Aβ(25–35) was rapid (minutes) at room temperature, whereas Aβ(1–40) and Aβ(1–42) required 5–6 d at 37°C. Aβ(35–25) was dissolved as Aβ(25–35), but did not form fibrils. Fibrillogenesis was monitored by thioflavine test (16) before the experiments. When Aβ were dissolved in DMSO they did not form fibrils and remain in solution.

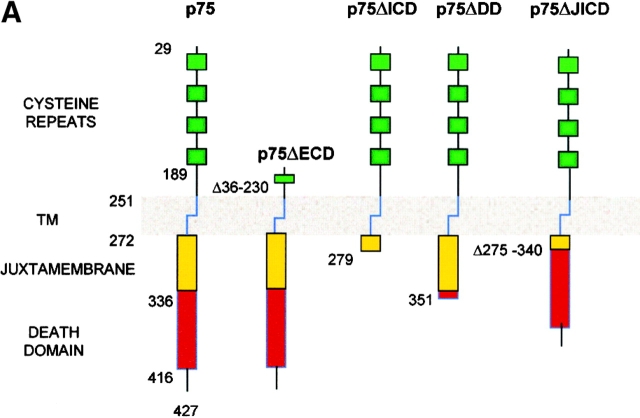

p75NTR and Tropomyosin-related Kinase A Constructs.

The construct encoding for the wild-type (wt) p75NTR (pCEP4_β_-p75) was generated by cloning the full-length human p75NTR cDNA into the PvuII site of the pCEP4_β_ mammalian expression vector which carries the hygro resistance gene (see Fig 1 A; Invitrogen). The p75_Δ_DD mutant, lacking aa from 352 to 427, was generated according to Hantzopoulos (53). The other deletion mutants p75_Δ_ECD, p75_Δ_ICD, and p75_Δ_JICD were obtained by PCR using specific primers and cloning the respective products into the pCEP4_β_ vector. Tropomyosin-related kinase (Trk)A expression plasmid was obtained by inserting the full-length cDNA encoding for the human TrkA receptor (54) into the episomal expression vector pCEP9_β_ which carries the neo resistance gene.

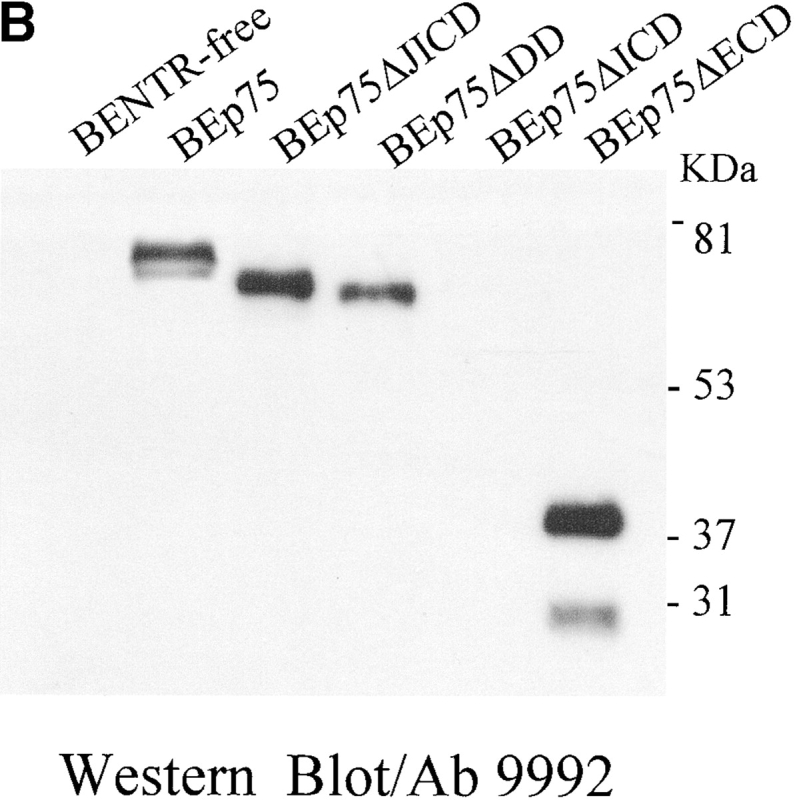

Figure 1.

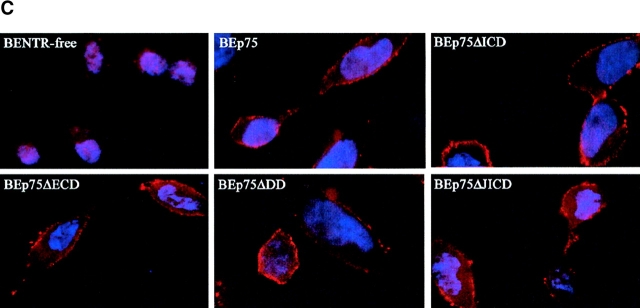

Expression of p75NTR in SK-N-BE neuroblastoma clones. (A) Schematic depiction of the full-length and truncated p75NTR proteins expressed in transfected SK-N-BE clones. Specifically, p75NTR, full-length receptor; p75ΔECD, p75 lacking the extracellular region (aa 36–230); p75ΔICD, p75 lacking the whole cytoplasmatic region (aa 280–427); p75ΔDD, p75 lacking the intracellular DD (aa 352–427); p75ΔJICD, p75 lacking the cytoplasmic JICD (aa 275–340). TM, transmembrane region. (B) p75NTR protein levels (Western blot analysis) in BENTR-free cell clones transfected with different constructs of p75NTR. (C) Localization of the p75NTR protein at the plasmamembrane by immunostaining with 9992 antiserum in BENTR-free, BEp75, BEp75ΔECD, BEp75ΔDD, and BEp75ΔJICD cell clones, and with mAb ME20.4 in BEp75ΔICD cell clones; the detection was performed by Cy3-conjugated anti–rabbit IgG or anti–mouse IgG; nuclei are blue-stained with DAPI.

Cell Clones.

The human neuroblastoma SK-N-BE cell line, which expresses neither p75NTR nor TrkA (BENTR-free) (34) was grown in RPMI 1640 medium (BioWhittaker) containing FBS (15% vol/vol; Life Technologies, Inc.), glutamine (2.0 mM), and gentamycin (50 μg/ml) and transfected by the liposome technique (Lipofectin Reagent; GIBCO BRL) (55) with 10 μg of each of the p75 constructs or with the TrkA codifying plasmid. As control BENTR-free cells were also transfected with the two empty vectors. Transfected cells were selected in complete medium containing either hygromycin (150 μg/ml) or G418 (300 μg/ml) (Roche Molecular Biochemicals). The antibiotic-resistant clones were characterized for expression of wt and mutated p75NTR proteins or the wt TrkA protein. The SK-N-BE derived cell clones generated were (see Fig. 1): (i) BEp75 expressing the full-length p75NTR; (ii) BEp75ΔECD lacking the four cysteine-rich repeats of the extracellular domain (aa 36–230); (iii) BEp75ΔICD lacking the whole intracellular region (aa 280–427); (iv) BEp75ΔDD, lacking the DD (aa 352–427); (v) BEp75ΔJICD missing the intracellular JICD (aa 275–340); and (vi) BETrkA expressing the full-length TrkA protein. BETrkA was further transfected with the plasmid encoding the full-length p75NTR and derived cell clones (BEp75TrkA) were selected with both hygromycin and G418.

Western Immunoblot and Immunocytochemistry Analysis.

Immunoblotting was used to test the cellular levels of the various forms of p75NTR and TrkA. Cells were lysed, fractioned by 8% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto nitrocellulose filters as described previously (34). Nitrocellulose filters were probed with one of the following antibodies: (i) anti-p75NTR 9992 polyclonal antiserum raised against the intracellular region (provided by M.V. Chao, New York University School of Medicine, New York, NY) (see Fig. 1 B); (ii) anti-TrkA rabbit polyclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.). The p75NTR and TrkA proteins were detected with a HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) and revealed by the ECL method (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). The expression level of p75NTR in BEp75 cell clones was 3–5-fold higher than in PC12 cells (34). The localization in the plasmamembrane of the various p75NTR and TrkA proteins was detected immunohistochemically using either the mAb ME20.4 (a gift from M.V. Chao) raised against the p75NTR extracellular domain or polyclonal antiserum 9992 (see Fig. 1 C) or anti-TrkA rabbit polyclonal antibody as described previously (34).

Experimental Protocol.

Cell clones were plated at 12,500 cells/cm2 for microscopic analysis and at 30,000 cells/cm2 for MTS assay. At the onset of the experimental treatments, the growth medium was replaced with a fresh complete RPMI 1640 medium containing 1% (vol/vol) FBS. Cultures were then exposed for various times to (i) Aβ peptides (1–42 or 1–40 or 25–35) in fibrillary state, (ii) human recombinant nerve growth factor-β (hrNGF-β) (Sigma-Aldrich), (iii) anti–human p75NTR mAb 8211 (Chemicon Int., Inc.) (56); or (iv) staurosporine (Calbiochem). In some instances, these treatments were also preceded by 2-h exposure to one of the following agents: Z-VAD-FMK (100 μM; Calbiochem), a nonspecific inhibitor of caspases; Z-IETD-FMK (20 μM; Calbiochem), a specific inhibitor of caspase-8; human recombinant TNF-α (10 ng/ml hrTNF-α) or 20 ng/ml IL-1β (PeproTech EC Ltd.); or 100 nM diphenyleneiodonium (DPI) (Sigma-Aldrich). All the experiments throughout the work were performed by using 20 μM Aβ(25–35) or 5 μM Aβ(1–40) and Aβ(1–42) since, on the basis of preliminary experiments, these concentrations correspond to those giving the maximal cytotoxicity in our experimental conditions. However, the cytotoxic effect of Aβ started to be detectable at a rather low concentration of Aβ (∼100 nM).

Assessment of Cell Damage and Viability.

Cell damage was analyzed by means of epifluorescence microscopy after staining the cells with a solution 1:1 (vol/vol) of acridine orange (AO; filter setting for FITC) and ethidium bromide (EB; filter setting for rhodamine) (both at 0.1 mg/ml in PBS; Molecular Probes), a procedure that reveals both apoptosis and necrosis (57). Annexin V-FITC binding test (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) evaluated by epifluorescence microscopy was also used for the detection of apoptosis in cells treated with NGF or mAb 8211, according to the manufacturer's procedure. This test was not suitable for cell treated with Aβ since these peptides interact with the complex Annexin V-FITC giving a diffuse fluorescence at the microscopic analysis. Cell viability was also assessed by using an MTS (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-5-[3-carboxymethoxyphenyl]-2-[4-sulfophenyl]-2H-tetrazolium, inner salt) assay kit (Promega).

Assay of Caspase Activity.

Cells were lysed in lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM NaH2PO4/Na2HPO4, 130 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 10 mM NaPPi). Cell lysates (30–50 μg protein) were incubated for 90 min at 37°C with 20 μM of fluorogenic substrate: caspase-3, Ac-DEVD-AMC or caspase-8, Z-IETD-AFC (both from BD PharMingen) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

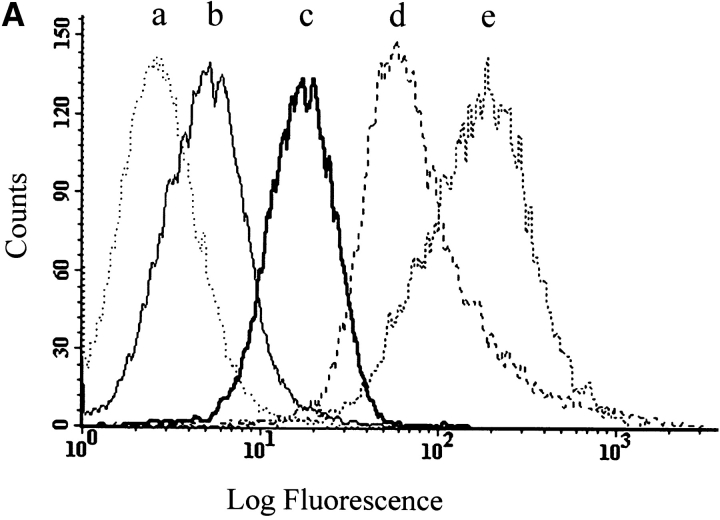

Expression of TNF and IL-1 Receptors.

BEp75 cell clones in suspension were first treated for 1 h at 4°C with primary mAb anti-TNFR55 H398 (donated by P. Scheurich, University of Stuttgart, Stuttgart Germany), mAb anti-TNFR75 utr-1 (Bachem; Peninsula Laboratories, Inc.) or mAb anti–IL-1RI (a gift from A. Mantovani, Istituto Mario Negri, Milano, Italy). After cell washing, the secondary biotin-conjugated IgG (Sigma-Aldrich) was added for 30 min at 4°C, followed by several washings and addition of 10 μl of streptavidin-phycoerythrin (Sigma-Aldrich). Cytofluorographic analysis was performed on a FACScan™ (Becton Dickinson) using CELLQuest™ software.

Statistical Analysis.

Multiple data points were compared by one-way ANOVA test with posthoc Dunnett multiple comparison test. The interaction between Aβ and TNF-α or IL-1β was determined by two-way ANOVA. All statistical tests were performed by SPSS 10 statistical package (SPSS, Inc.).

Results

Expression of p75NTR and the Cytotoxicity of Aβ.

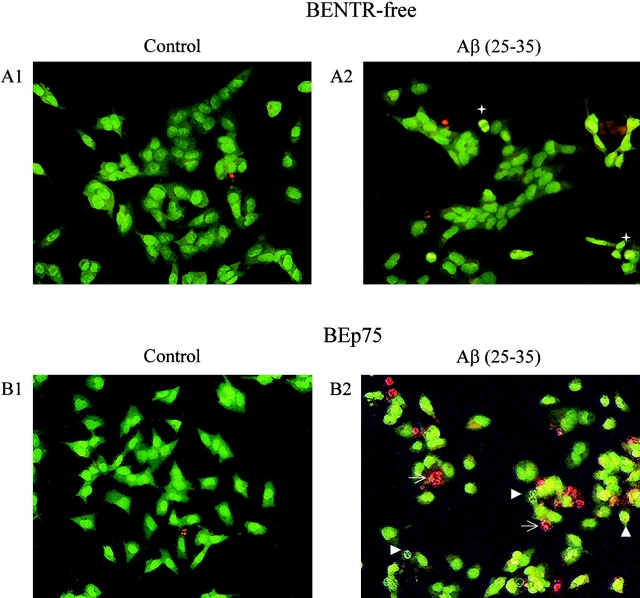

We first investigated the effect of these peptides on the BENTR-free cells (34), and on BEp75 (Fig. 1). Our results showed that Aβ(25–35), Aβ(1–40), and Aβ(1–42) were able to induce cell death in BEp75 cells, while being totally harmless for BENTR-free cells (Fig. 2 and Table I) or BENTR-free cells transfected with an empty pCEP4β vector (data not shown). The morphologic assessment (Fig. 2) of cell damage showed that, in our experimental conditions, Aβ induced cell death via both apoptosis and necrosis, as reported previously (24, 58, 59). Aβ were toxic only in a fibrillar state, as previously shown (4–6). Reverse order Aβ were harmless (not shown).

Figure 2.

Epifluorescence microscopic analysis of cell damage by Aβ. (A1) and (A2) BENTR-free cells, untreated and treated for 24 h with Aβ(25–35) (20 μM), respectively. (B1) and (B2) BEp75 cells, untreated and treated for 24 h with Aβ(25–35) (20 μM), respectively. A pale green nuclear fluorescence by AO identifies still normal cells. A dazzling yellow nuclear fluorescence by AO (arrowheads) reveals the progressive chromatin condensation, collapse, and marginalization proper of apoptosis. A vivid red fluorescence of chromatin remnants by EB (arrows) denotes cells, whose membrane integrity was lost as the death process shifted from apoptosis to necrosis. +, mitosis.

Table I.

Cell Death Induced by Aβ Peptides

| BENTR-free | BEp75 | BEp75TrkA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 h | 48 h | 24 h | 48 h | 24 h | 24 h | |

| Controls | 5.9 ± 2.6a(18) | 7.8 ± 2.6 (18) | 8.2 ± 2.2 (62) | 9.2 ± 2.4 (20) | 5.3 ± 2.5 (3) | 10.3 ± 2.1 (3) |

| Aβ(25–35) | 5.2 ± 2.6 (12) | 6.2 ± 2.8 (12) | 29.7 ± 4.5b(65) | 34.0 ± 4.8b (14) | 7.1 ± 3.1 (5) | 28.5 ± 6.3b (5) |

| Aβ(1–40) | 5.6 ± 2.3 (5) | 5.5 ± 2.8 (4) | 27.6 ± 2.3b (5) | 33.2 ± 6.2b (4) | ||

| Aβ(1–42) | 5.6 ± 1.6 (5) | 7.3 ± 1.8 (4) | 30.0 ± 2.5b (3) | 30.9 ± 2.2b (4) |

We also investigated the role of NGF receptor TrkA by examining the effect of Aβ on cell clones expressing TrkA only (BETrkA), or on cell clones expressing both TrkA and full-length p75NTR (BEp75TrkA). The results (Table I) show that BETrkA clones were insensitive to the toxic action by Aβ, whereas BEp75TrkA clones were sensitive to the action of Aβ to the same extent as were BEp75 clones.

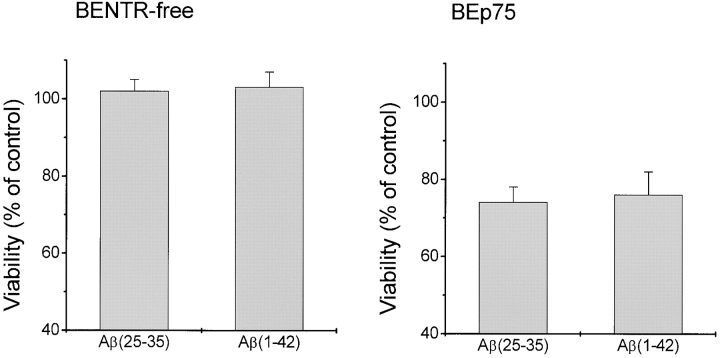

The cytotoxic effect of Aβ was further verified using MTS reduction test. The data in Fig. 3 show that the MTS assay gave results similar to those obtained by using the double-staining epifluorescence method.

Figure 3.

Cell death analysis by MTS assay. BENTR-free and BEp75 cells were treated with Aβ(25–35) (20 μM), or Aβ(1–42) (5.0 μM) for 48 h, then evaluated for cell viability as compared with untreated controls. Data are means ±SD of four experiments.

Signaling for Cell Death Induced by Aβ via p75NTR.

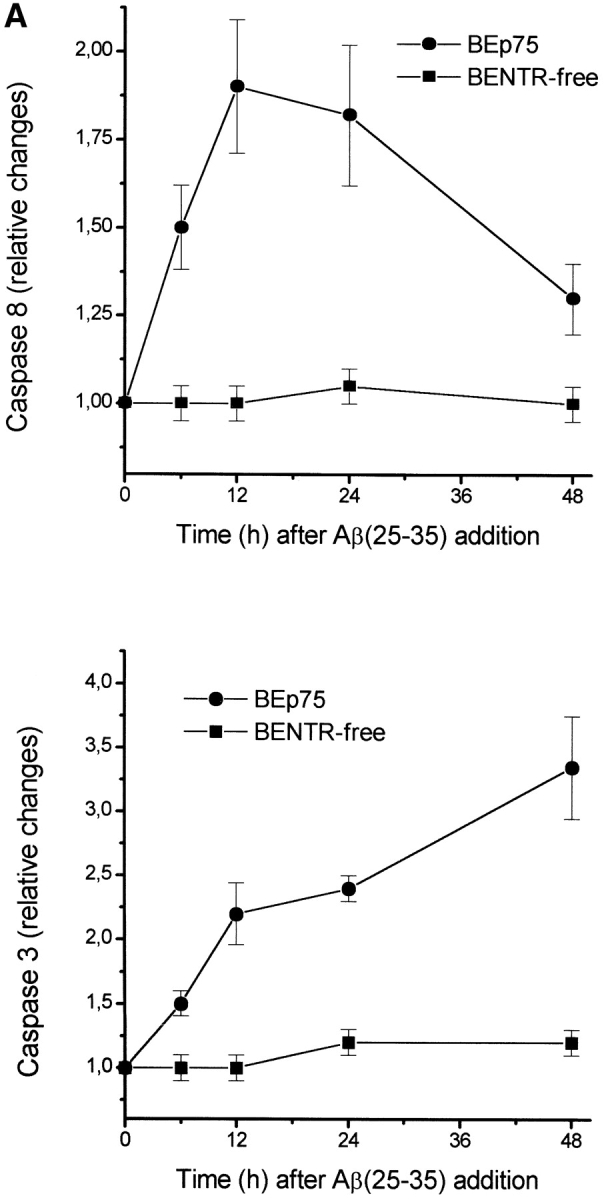

Our results show that the toxicity by Aβ was associated with the activation of both caspase-8 and caspase-3 in BEp75 cells (Fig. 4 A). A role for these caspases in Aβ-induced, p75NTR-mediated cell death was further supported by the finding (Fig. 4 B) that Aβ neurotoxicity was prevented by Z-VAD-FMK, a nonselective inhibitor of caspases, and by Z-IETD-FMK, a specific inhibitor of caspase-8. In the same experiments, the cell death induced by staurosporine, a well known protein kinase inhibitor that induces apoptosis, (Fig. 4 B) was prevented by the unspecific inhibitor of caspases, but could not be suppressed by the inhibitor of caspase-8. The cytotoxic effect by Aβ was also prevented by DPI (Fig. 4 B), an inhibitor of oxygen-free radicals forming NADPH oxidase and of other flavoprotein dehydrogenases (16) indicating that p75NTR-mediated cell death induced by Aβ was associated with the activation of ROI sources and oxidative stress.

Figure 4.

Metabolic features of cell death induced by Aβ. (A) Time course of the activation of caspases-8 and -3 as induced by a treatment with Aβ(25–35) (20 μM). Results shown are means ±SD of four experiments. (B) Effect of Z-VAD-FMK (100 μM), a nonspecific inhibitor of caspases, of Z-IETD-FMK (20 μM), a specific inhibitor of caspase-8, and of DPI (100 nM), an inhibitor of ROI-forming NADPH oxidase and other flavoprotein dehydrogenases, on the cytotoxic activity by Aβ(25–35) (20 μM), Aβ(1–42) (5.0 μM), NGF (10 nM), mAb 8211 (5.0 μg/ml), and staurosporine (200 nM) in BEp75 cells. Data are reported as means ±SD of three to four experiments (mAb 8211, two experiments).

The Extracellular Region of p75NTR Is Necessary for the Cytotoxic Effect.

Two mechanisms might be responsible for the role of p75NTR in the cytotoxicity by Aβ: (i) p75NTR is permissive for or potentiates the cytotoxicity by Aβ, as in the case of excitotoxicity (60); alternatively, (ii) p75NTR is directly involved in cell death after the binding of Aβ (25, 26). The validity of the latter mechanism is supported by the results obtained by using BEp75ΔECD cells expressing a p75NTR truncated in the extracellular region. In the mature receptor, this region is composed by four 40 aa cysteine-rich repeats, the second and the fourth are believed to be the binding sites for NGF and is linked to the membrane-spanning region by a 61 aa segment rich in proline, serine and threonine residues (61). Previous results showing that NGF could displace Aβ bound to p75NTR-transfected cells (24) or to neurons spontaneously expressing p75NTR only (25) led to the conclusion that Aβ bind to the extracellular region of p75NTR. The results show (Fig. 5) that BEp75ΔECD cells, expressing a p75NTR lacking the four cysteine repeats of the extracellular region (Fig. 1), were unaffected by the treatment with Aβ, indicating that Aβ interact with and require the extracellular region of p75NTR to exert their neurotoxic effect.

Figure 5.

Effect of Aβ and p75NTR agonists on cell death in neuroblastoma cell clones expressing different forms of p75NTR. BENTR-free cells lacking all the neurotrophin receptors and clones derived from them expressing the full length (BEp75) or differently truncated forms of p75NTR (compare with Fig. 1) were treated with Aβ(25–35) (20 μM), Aβ(1–42) (5.0 μM), NGF (10 nM), or mAb 8211 (5.0 μg/ml) and staurosporine (100 nM) for 24 h. The results of these experiments are reported as means ±SD of 5–10 experiments. In the case of BENTR-free cells and BEp75 cells the effects are also shown of a 2 h pretreatment with NGF (10 nM) or mAb 8211 (5.0 μg/ml) followed by Aβ(25–35) (20 μM). The results are reported as means ±SD of three or five experiments when the pretreatment was made with mAb 8211 or NGF, respectively.

Furthermore we treated BENTR-free, BEp75, or BEp75ΔECD cell clones with NGF or the mAb 8211, which interacts with the binding site of NGF (56). The results (Fig. 5) show that NGF or mAb 8211 induced cell death in BEp75, but not in BENTR-free or BEp75ΔECD clones. The morphological aspects of the cell damage examined by means of the double staining with AO and EB were similar to those by Aβ (Fig. 6 A). Furthermore the cells treated with NGF or mAb 8211 appeared Annexin V-positive indicating the presence of an apoptotic process (Fig. 6 B). The signals for cell death triggered by the binding of NGF or mAb 8211 to the extracellular region of p75NTR appear to be similar to those triggered by the binding of Aβ. In fact, also the cell death by NGF or mAb 8211 was inhibited by Z-VAD-FMK, a nonspecific inhibitor of caspases, by Z-IETD-FMK, the specific inhibitor of caspase-8, and by DPI, an inhibitor of ROI-forming NADPH oxidase and other flavin-dehydrogenases (Fig. 4 B).

Figure 6.

Epifluorescence microscopic analysis of cell damage by NGF and mAb 8211. BEp75 cells untreated and treated for 24 h with NGF (10 nM) or mAb 8211 (5.0 μg/ml) (A) stained with OA plus EB (for details see Fig. 2), or (B) with Annexin V-FITC plus propidium iodide. (C) Phase contrast images corresponding to those in B.

To clarify the relations between the mechanisms of p75NTR activation by Aβ, NGF or mAb 8211, we investigated the effect of Aβ in BEp75 cells, whose p75NTR receptor had been previously occupied by NGF or mAb 8211. The results (Fig. 5) show that Aβ, NGF, or mAb 8211 exerted cytotoxic activities of comparable magnitude when added each by itself, but when given serially — mAb 8211 or NGF first and Aβ next — their cytotoxic effects were neither additive nor synergistic. These findings suggest that Aβ, NGF, and mAb 8211 act via a similar mechanism by binding the same or closely related sequences of the extracellular region of p75NTR and thereby triggering an alike activation of the receptor.

Role of the Intracellular Region of p75NTR in the Cytotoxicity by Aβ, mAb 8211, and NGF.

The results so far presented, showing that Aβ are cytotoxic by binding to the extracellular region of p75NTR, raise the problem whether Aβ-binding activates p75NTR and triggers cell death via the receptor's intracellular region, or uses p75NTR as an anchor allowing the induction of cell damage via other mechanisms. To solve this problem, we investigated the effect of Aβ on BEp75ΔICD cell clones expressing a truncated p75NTR devoid of the entire intracellular region (Fig. 1). The results (Fig. 5) show that these cells were insensitive to the toxic effects of Aβ, NGF, or mAb 8211, indicating that p75NTR directly participates to the cell damage by these ligands via the signaling function of its intracellular region.

We next investigated the roles played in p75NTR-dependent cell death by the DD and the JICD domains. In spite of many studies (41, 46–52), the respective functions of these two domains remain unclear. We challenged with Aβ, mAb 8211, or NGF BEp75ΔDD cell clones expressing a truncated p75NTR devoid of the largest part of the DD (Fig. 1). The results (Fig. 5) show that these cells were insensitive to the toxic actions of Aβ, mAb 8211, or NGF, demonstrating that the ligand-induced p75NTR-mediated cell death does require the function of the DD. As a control, we found that staurosporine could induce cell death in all the cell clones expressing various truncated forms of p75NTR (Fig. 5), indicating that these clones remained susceptible to apoptogenic agents, whose activity is independent of p75NTR signaling. To understand the role of the juxtamembrane region, we treated BEp75ΔJICD cell clones expressing a truncated p75NTR lacking the whole JICD with Aβ, mAb 8211, or NGF (Fig. 1). The results (Fig. 5) show that these cells were sensitive to the cytotoxic effects of all three ligands, just as BEp75 cells were, indicating that the function of the JICD is not involved in the death signaling triggered by such agonists. Here it is worth noting that, in the absence of agonists, BEp75ΔJICD clones exhibited a far higher level of spontaneous mortality than did all the other clones we tested (Fig. 5).

TNF-α and IL-1β Synergize with the Aβ Neurotoxicity Mediated by p75NTR.

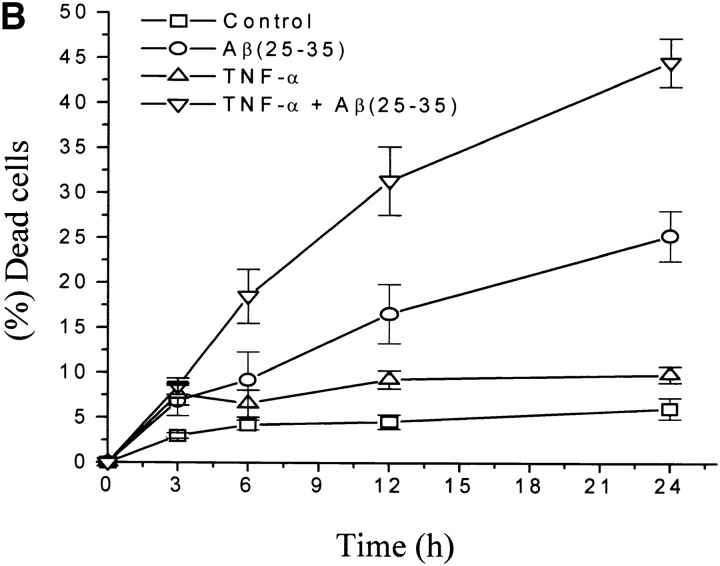

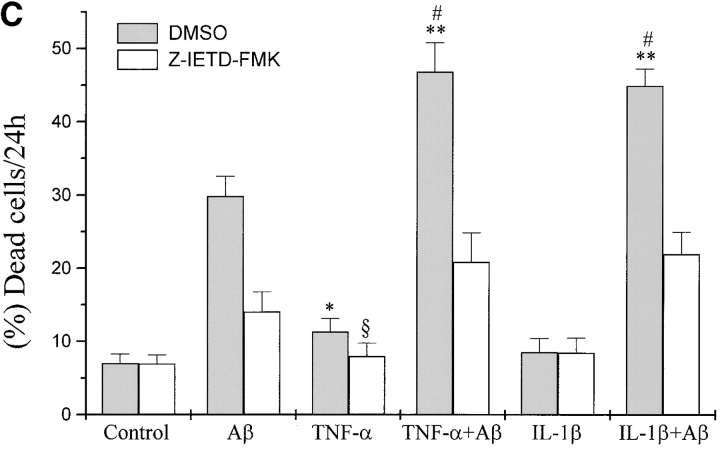

Several studies have reported that in AD, besides a direct effect of Aβ on neurons, cell damage is due also to an inflammatory reaction mainly correlated with the activation of microglia and astrocytes by Aβ to produce inflammatory mediators, including NO, ROI, IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (10–16). The role of TNF in brain injury and neurodegenerative diseases is still controversial (62–65). Since neurons within AD plaques are attacked by Aβ, TNF-α, and other cytokines, we investigated the effects of TNF-α on the Aβ-induced p75NTR-mediated neurotoxicity. For this purpose we pretreated with this cytokine and then with Aβ(25−35) BEp75 cell clones, which express TNF receptors (Fig. 7 A). The results show that (i) TNF-α by itself exerted a slight cytotoxic action and could synergistically potentiate the toxic effect by Aβ (Fig. 7 B); (ii) the effects of both TNF-α by itself and TNF-α plus Aβ were inhibited by the inhibitor of caspase-8, Z-IETD-FMK (20 μM; Fig. 7 C).

Figure 7.

Potentiation by TNF-α and IL-1β of the cytotoxic activity of Aβ. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of cell surface expression of TNF-α and IL-1β receptors: (a) fluorescence intensity of cells stained only with the secondary antibody; (b) with mAb utr-1 against TNFR75; (c) with mAb H398 against TNFR55; (d) with mAb 8211 against p75NTR as positive control; (e) with mAb against IL-1RI. (B) Synergistic effect of TNF-α on the cytotoxicity of Aβ(25–35) (20 μM). Data are means ±SD of three experiments. (C) Effect of IL-1β and TNF-α in the presence or absence of Z-IETD-FMK (20 μM). Data are means ±SD of 11 experiments in the absence and of three in the presence of Z-IETD-FMK with TNF-α with and without Aβ and of five experiments in the absence and three in the presence of Z-IETD-FMK with IL-1β with and without Aβ. TNF-α vs. control, *P < 0.05 (n = 11); **(Aβ[25–35] + TNF-α vs. Aβ[25 -35]), P < 0.001 (n = 11); (Aβ[25–35] + IL-1β vs. Aβ[25 -35]), P < 0.001 (n = 5); TNF-α + Z-IETD vs. TNF-α, § P < 0.05 (n = 3); #positive interaction (synergism) versus null interaction (additive effect) of the two factors, P < 0.001 (n = 11 for TNF-α and n = 5 for IL-1β).

To understand if the synergistic effect is specific of TNF-α we investigated the activity of IL-1β, another cytokine produced by microglia activated by Aβ. After assessing that BEp75NTR cells express the receptor IL-1Rl (Fig. 7 A) we treated the cell with this cytokine and then with Aβ (25–35). The results show (Fig. 7 C) that IL-1β did not exert by itself a cytotoxic action but synergistically potentiated Aβ. Again, even the effect of IL-1β plus Aβ was inhibited by the inhibitor of caspase-8, Z-IETD-FMK (20 μM).

Discussion

In this work, we addressed two problems, i.e., the role of p75NTR in the direct mechanism of cell damage by Aβ, and the possibility that the direct and the indirect (inflammatory) mechanisms of neuronal damage be correlated and, somehow, coworking.

I. The rationale of the first problem is based on the findings that Aβ-induced cell damage associates with the presence of p75NTR on the cell surface (24–25). We first confirmed (Table I) these findings by using an experimental model consisting in the treatment with Aβ of BENTR-free cell clones devoid of all the neurotrophin receptors and of BEp75 cell clones expressing full-length p75NTR.

Once we confirmed that p75NTR is necessary for the toxic action of Aβ, we tried to clarify the mechanism by which p75NTR works. Three findings demonstrate that the first step of this mechanism is the interaction of Aβ with the external region of this receptor. (i) Consistently with the previous findings by others (24, 25) that Aβ bind to p75NTR, BEp75ΔECD cells, which are devoid of the four cysteine-rich repeats of the extracellular region of the receptor, were insensitive to the cytotoxic action of Aβ; (ii) NGF and mAb 8211, which interacts with the region including the binding site of NGF, mimicked the cytotoxic effect of Aβ in BEp75 cells expressing the full-length p75NTR, but were harmless for BEp75ΔECD cells, whose p75NTR lacks the four cysteine-rich repeats; and (iii) the pretreatment of BEp75 cell clones with NGF or mAb 8211 did not elicit any additive toxic effect by Aβ, likely due to an hindrance to the binding of Aβ, as suggested by previous results showing that NGF displaced bound Aβ from p75NTR (25, 26).

We do not know what is the precise domain of the extracellular region of p75NTR responsible for the binding of Aβ. The fact that Aβ bind different and structurally unrelated receptors (13, 20–27) might suggest that such interactions occur in nonspecific ways (66) and that the binding of Aβ to p75NTR takes place in a manner differing from the recently described interaction between NGF and p75NTR (67). This raises the problem of whether the binding between fibrillar Aβ and p75NTR might activate this receptor or only permit the tethering of Aβ to the cell membrane and its subsequent toxic activity independently of any activation of p75NTR. The finding that BEp75ΔICD cells, retaining the extracellular binding region but lacking the whole intracellular region, were insensitive to the action of Aβ clearly demonstrates that, in our experimental model, cell death by Aβ requires the activation of p75NTR and its signaling via the intracellular region. The two main portions of the intracellular region are the DD and the JICD but the functions of these domains are not yet understood. Recently, various factors have been identified that interact with different sequences of the intracellular region of p75NTR and are thus potentially involved in signal transduction, i.e., TRAF family proteins, of which TRAF-2 interacts with the helical COOH-terminal region corresponding to the DD, and TRAF-4 and TRAF-6 interact with the JICD region (46, 50); FAP-1, which binds to the intracellular region at a COOH-terminal Ser-Pro-Val residue (47); NRIF, which interacts with two discrete sequences, the JICD and the DD (49); SC-1, a zinc finger protein (51), and NRAGE (52), both of which bind to the JICD region; and NADE (48), RhoA (68) and RIP2 (69) which bind to the DD. Some data indicate that the JICD region, but not the DD, is required for neuronal death in an experimental model, in which a ligand-independent kind of apoptosis is induced by an overexpressed p75NTR (41). We have investigated whether the JICD region were involved in cell death by Aβ, NGF, or mAb 8211, and our results show (Fig. 5) that this is not the case, because all the three agonists were toxic for BEp75ΔJICD cells expressing a JICD-devoid p75NTR. The reasons for the discrepancy between our results and those of others (41) remain to be investigated. The different experimental conditions, i.e., a ligand-independent apoptotic stimulus in p75NTR-overexpressing cells (41), and, as in our case, ligand-dependent apoptotic stimuli in cells overexpressing p75NTR along with the specific composition of p75NTR interactors within these cells, could be responsible for such a discrepancy. Interestingly, in 1% serum medium, BEp75ΔJICD cell clones, expressing a p75NTR devoid of most of the JICD, exhibited a spontaneous greater mortality than BEp75 cell clones. This indicates that, under our experimental conditions, the JICD is necessary for the optimal survival of BEp75 cells.

Regarding the role of the DD of p75NTR, our results show that this domain is necessary for the cell death induced by Aβ. In fact, BEp75ΔDD cell clones were insensitive to the cytotoxic effects by Aβ, NGF, or mAb 8211. These results agree with those showing that the DD of p75NTR is involved in ligand (NGF)-dependent p75NTR-mediated cell death via the binding (at aa 338–396) of the cell death executor protein NADE (48), and in cell death by serum withdrawal (70) or by p75NTR-induced expression (71).

In conclusion, on the basis of the previous results showing that Aβ bind to p75NTR (24, 25) and of those presented here, we propose that the mechanism of p75NTR-mediated cell death by Aβ occurs through a cascade of biochemical processes signaled by the receptor DD. Among these processes we have identified the oxidative stress (Fig. 4 B) and the activation of caspase-8 and -3 (Fig. 4 A), the former being the proteolytic enzyme mediating signal transduction downstream the death receptors family (72). Many studies have been performed on the role of caspases in neuronal cell death by Aβ and the results are not conclusive, because several caspases were found to be activated, i.e., caspase-2 (73), caspase-3 (74), caspase-8 (75, 76), caspase-12 (77), and caspases-2, -3, and -6 (78). Conversely, caspases-3, -6, and -9, but not caspase-8, were found to be activated during apoptosis by induction of p75NTR expression (71), and caspases-1, -2, -3, but not -8, in cell death by p75NTR–bound NGF (79). The reasons for such discrepancies remain unclear. In any case, the finding that the specific inhibition of caspase-8 prevented cell death by Aβ (Fig. 4 B) could indicate that in our experimental model caspase-8 acts upstream in the cell death signaling.

II. As previously mentioned, it has been suggested that in AD an inflammatory reaction, which does not involve the migration of blood cells, but only the local production of cytokines and other mediators by glial cells, contributes per se to tissue damage and to Aβ formation (14, 16, 65). Herein we have shown that this inflammatory reaction can cooperate with the direct mechanism of cytotoxicity by Aβ. In fact, TNF-α and IL-1β can synergistically potentiate the ability of Aβ to induce death in neuronal cells expressing the full-length p75NTR (Fig. 7). The finding that inflammatory mediators, produced by Aβ-activated microglia and astrocytes, were able to synergize with the p75NTR-mediated toxicity by Aβ is of relevance for the pathogenesis of neuronal damage in AD. In fact, the exposure of p75NTR-expressing neurons to Aβ fibrils and to TNF-α and/or IL-1β mimics the condition occurring in the brain of AD, in which both the direct and indirect mechanisms of cell damage are present and work concurrently. Thus, the death signals triggered by p75NTR could be a unifying pathway upon which converge the effects of both Aβ and inflammatory cytokines. It will be of interest to investigate if other cytokines produced by glial cells activated by Aβ (10–16) have a synergistic effect similar to TNF-α and IL-1β.

III. The findings that p75NTR is involved in neurotoxicity by Aβ raise some problems worth to be investigated, such as the type of interaction between p75NTR and Aβ, the structural changes of the receptor triggered by the bound Aβ corresponding to the assumption of an activated state, and the other mechanisms, besides those of the activation of caspases and oxidative stress, by which neuronal death is enacted (40, 80).

Another problem, relevant to the pathogenesis of neurodegeneration in AD, is the actual role of p75NTR in neuronal damage in vivo. The results of the in vitro experiments presented here and in other reports (24, 25), and the correlation between the expression of p75NTR and the vulnerability of the cholinergic neurons in the brain of AD patients (38, 39) are in keeping with an involvement of this receptor. However, one cannot underestimate the fact that Aβ can nonspecifically interact with several proteins (66), and that in vitro Aβ can induce cell death by interacting also with other receptors of neuronal surface, such as RAGE (21), α7NAChR (23), and APP (26), or with additional molecules, such as phospholipids and gangliosides (19). Furthermore, our finding that the activity of caspase-8 is stimulated by Aβ, supports the concept that Aβ activate a receptor-mediated, rather than a stress-mediated, cell death pathway. Thus, in AD, alongside with p75NTR, it is likely that also other receptors or interactors be involved, depending on their distribution and level of surface expression and on the types and functional states of the neurons characteristic of the brain regions where the extracellular formation of fibrillar aggregates can be favored. However, the results presented here indicate that neurons expressing p75NTR might be preferential targets of the toxic activity of Aβ, especially if they express also receptors of TNF or other cytokines.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Claudio Costantini for technical assistance.

This work was supported by grants from Progetto Sanità 1996-97, Fondazione Cariverona (to F. Rossi), Cofinanziamento Murst-Università (to F. Rossi and U. Armato), and the 5th Framework Program of the European Union grant no. QLRT-1999-00573 (to G. Della Valle).

Footnotes

*

Abbreviations used in this paper: α7NAChR, α-7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor; aa, amino acid; Aβ, β-amyloid peptide; AD, Alzheimer's disease; AO, acridine orange; APP, β-amyloid precursor protein; BBP, β-amyloid–binding protein; DD, death domain; DPI, diphenyleneiodonium; EB, ethidium bromide; JICD, juxtamembrane domain; NGF, nerve growth factor; NO, nitric oxide; p75NTR, neurotrophin receptor p75; RAGE, advanced glycation endproducts receptors; ROI, reactive oxygen intermediates; Trk, tropomyosin-related kinase.

References

- 1.Hardy, J., and D. Allsop. 1991. Amyloid deposition as the central event in the aetiology of Alzheimer's disease. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 12:383–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yankner, B.A., and M.M. Mesulam. 1991. β–amyloid and the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 325:1849–1857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Selkoe, D.J. 1999. Translating cell biology into therapeutic advances in Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 399:A23–A31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iversen, L.L., R.J. Mortishire-Smith, S.J. Pollack, and M.S. Shearman. 1995. The toxicity in vitro of β–amyloid protein. Biochem. J. 311:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pike, C.J., A.J. Walencewicz, C.G. Glabe, and C.W. Cotman. 1991. In vitro aging of β-amyloid protein causes peptide aggregation and neurotoxicity. Brain Res. 563:311–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lorenzo, A., and B.A. Yankner. 1994. β-amyloid neurotoxicity requires fibril formation and is inhibited by congo red. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 91:12243–12247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klein, W.L., G.A. Krafft, and C.E. Finch. 2001. Targeting small Aβ oligomers: the solution to an Alzheimer's disease conundrum? Trends Neurosci. 24:219–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yankner, B.A., L.K. Duffy, and D.A. Kirschner. 1990. Neurotrophic and neurotoxic effects of amyloid-β protein: reversal by tachykinin neuropeptides. Science. 250:279–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koh, J.Y., L.L. Yang, and C.W. Cotman. 1990. β–amyloid protein increases the vulnerability of cultured cortical neurons to excitotoxic damage. Brain Res. 533:315–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meda, L., M.A. Cassatella, G.I. Szendrei, L. Otvo, Jr., P. Baron, M. Villalba, D. Ferrari, and F. Rossi. 1995. Activation of microglial cells by β-amyloid protein and interferon-γ. Nature. 374:647–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goodwin, J.L., E. Uemura, and J.E. Cunnick. 1995. Microglial release of nitric oxide by the synergistic action of β-amyloid and IFN-γ. Brain Res. 692:207–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Klegeris, A., D.G. Walker, and P.L. McGeer. 1994. Activation of macrophages by Alzheimer β amyloid peptide. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 199:984–991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El Khoury, J., S.E. Hickman, C.A. Thomas, L. Cao, S.C. Silverstein, and J.D. Loike. 1996. Scavenger receptor-mediated adhesion of microglia to β-amyloid fibrils. Nature. 382:716–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGeer, P.L., and E.G. McGeer. 1995. The inflammatory response system of brain: implications for therapy of Alzheimer and other neurodegenerative diseases. Brain Res. Rev. 21:195–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eikelenboom, P., S.S. Zhan, W.A. van Gool, and D. Allsop. 1994. Inflammatory mechanisms in Alzheimer's disease. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 15:447–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Della Bianca, V., S. Dusi, E. Bianchini, I. Dal Pra, and F. Rossi. 1999. β-amyloid activates O2–forming NADPH oxidase in microglia, monocytes and neutrophils. A possible inflammatory mechanism of neuronal damage in Alzheimer's disease. J. Biol. Chem. 274:15493–15499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Durell, S.R., H.R. Guy, N. Arispe, E. Rojas, and H.B. Pollard. 1994. Theoretical models of the ion channel structure of amyloid β-protein. Biophys. J. 67:2137–2145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Terzi, E., G. Holzemann, and J. Seelig. 1995. Self-association of β-amyloid peptide (1-40) in solution and binding to lipid membrane. J. Mol. Biol. 252:633–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McLaurin, J., and A. Chakrabartty. 1996. Membrane disruption by Alzheimer β-amyloid peptides mediated through specific binding to either phospholipids or gangliosides. Implications for neurotoxicity. J. Biol. Chem. 271:26482–26489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tiffany, H.L., M.C. Lavigne, Y.H. Cui, J.M. Wang, T.L. Leto, J.L. Gao, and P.M. Murphy. 2001. Amyloid-β induces chemotaxis and oxidant stress by acting at formylpeptide receptor 2 (FPR2), a G protein-coupled receptor expressed in phagocytes and brain. J. Biol. Chem. 276:23645–23652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yan, S.D., X. Chen, J. Fu, M. Chen, H. Zhu, A. Roher, T. Slattery, L. Zhao, M. Nagashima, J. Morser, et al. 1996. RAGE and amyloid-β peptide neurotoxicity in Alzheimer's disease. Nature. 382:685–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boland, K., M. Behrens, D. Choi, K. Manias, and D.H. Perlmutter. 1996. The serpin-enzyme complex receptor recognizes soluble, non toxic amyloid-β peptide but not aggregated, cytotoxic amyloid-β peptide. J. Biol. Chem. 271:18032–18044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang, H.Y., D.H. Lee, M.R. D'Andrea, P.A. Peterson, R.P. Shank, and A.B. Reitz. 2000. β-amyloid(1-42) binds to α-7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor with high affinity. Implications for Alzheimer's disease pathology. J. Biol. Chem. 275:5626–5632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yaar, M., S. Zhai, P.F. Pilch, S.M. Doyle, P.B. Eisenhauer, R.E. Fine, and B.A. Gilchrest. 1997. Binding of β-amyloid to the p75 neurotrophin receptor induces apoptosis. A possible mechanism for Alzheimer's disease. J. Clin. Invest. 100:2333–2340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuner, P., R. Schubenel, and C. Hertel. 1998. β-amyloid binds to p75NTR and activates NF-κB in human neuroblastoma cells. J. Neurosci. Res. 54:798–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lorenzo, A., M. Yuan, Z. Zhang, P.A. Paganetti, C. Sturchler-Pierrat, M. Staufenbiel, J. Mautino, F.S. Vigo, B. Sommer, and B.A. Yankner. 2000. Amyloid β interacts with the amyloid precursor protein: a potential toxic mechanism in Alzheimer's disease. Nat. Neurosci. 3:460–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kajkowski, E.M., C.F. Lo, X. Ning, S. Walker, H.J. Sofia, W. Wang, W. Edris, P. Chanda, E. Wagner, S. Vile, et al. 2001. β-amyloid peptide-induced apoptosis regulated by a novel protein containing a G protein activation module. J. Biol. Chem. 276:18748–18756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chao, M.V., M.A. Bothwell, A.H. Ross, H. Koprowski, A.A. Lanahan, C.R. Buck, and A. Sehgal. 1986. Gene transfer and molecular cloning of the human NGF receptor. Science. 232:518–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith, C.A., T. Farrah, and R.G. Goodwin. 1994. The TNF receptor superfamily of cellular and viral proteins: activation, costimulation, and death. Cell. 76:959–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nagata, S. 1997. Apoptosis by death factor. Cell. 88:355–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Casaccia-Bonnefil, P., B.D. Carter, R.T. Dobrowsky, and M.V. Chao. 1996. Death of oligodendrocytes mediated by the interaction of nerve growth factor with its receptor p75. Nature. 383:716–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frade, J.M., A. Rodriguez-Tebar, and Y.A. Barde. 1996. Induction of cell death by endogenous nerve growth factor through its p75 receptor. Nature. 383:166–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dechant, G., and Y.A. Barde. 1997. Signalling through the neurotrophin receptor p75NTR. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 7:413–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bunone, G., A. Mariotti, A. Compagni, E. Morandi, and G. Della Valle. 1997. Induction of apoptosis by p75 neurotrophin receptor in human neuroblastoma cells. Oncogene. 14:1463–1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bredesen, D.E., and S. Rabizadeh. 1997. p75NTR and apoptosis: Trk-dependent and Trk-independent effects. Trends Neurosci. 20:287–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Friedman, W.J. 2000. Neurotrophins induce death of hippocampal neurons via the p75 receptor. J. Neurosci. 20:6340–6346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rabizadeh, S., C.M. Bitler, L.L. Butcher, and D.E. Bredesen. 1994. Expression of the low-affinity nerve growth factor receptor enhances β-amyloid peptide toxicity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 91:10703–10706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Woolf, N.J., R.W. Jacobs, and L.L. Butcher. 1989. The pontomesencephalo-tegmental cholinergic system does not degenerate in Alzheimer's disease. Neurosci. Lett. 96:277–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Woolf, N.J., E. Gould, and L.L. Butcher. 1989. Nerve growth factor receptor is associated with cholinergic neurons of the basal forebrain but not the pontomesencephalon. Neuroscience. 30:143–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Connor, B., and M. Dragunow. 1998. The role of neuronal growth factors in neurodegenerative disorders of the human brain. Brain Res. Rev. 27:1–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Coulson, E.J., K. Reid, and P.F. Bartlett. 1999. Signaling of neuronal cell death by the p75 neurotrophin receptor. Mol. Neurobiol. 20:29–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee, F.S., A.H. Kim, G. Khursigara, and M.V. Chao. 2001. The uniqueness of being a neutrotrophin receptor. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 11:281–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chapman, B.S. 1995. A region of p75 kDa neurotrophin receptor homologous to the death domains of TNFR-I and Fas. FEBS Lett. 374:216–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Feinstein, E., A. Kimchi, D. Wallach, M. Boldin, and E. Varfolomeev. 1995. The death domain: a module shared by proteins with diverse cellular functions. Trends Biochem. Sci. 20:342–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liepinsh, E., L.L. Ilag, G. Otting, and C.F. Ibanez. 1997. NMR structure of the death domain of the p75 neurotrophin receptor. EMBO J. 16:4999–5005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ye, X., P. Mehlen, S. Rabizadeh, T. VanArsdale, H. Zhang, H. Shin, J.J.L. Wang, E. Leo, J. Zapata, C.A. Hauser, et al. 1999. TRAF family proteins interact with the common neurotrophin receptor and modulate apoptosis induction. J. Biol. Chem. 274:30202–30208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Irie, S., T. Hachiya, S. Rabizadeh, W. Maruyama, J. Mukai, Y. Li, J.C. Reed, D.E. Bredesen, and T.-A. Sato. 1999. Functional interaction of Fas-associated phosphatase-1 (FAP-1) with p75NTR and their effect on NF-κB activation. FEBS Lett. 460:191–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mukai, J., T. Hachiya, S. Shoji-Hoshino, M.T. Kimura, D. Nadano, P. Suvanto, T. Hanaoka, Y. Li, S. Irie, L.A. Greene, and T.-A. Sato. 2000. NADE, a p75NTR-associated cell death executor, is involved in signal transduction mediated by the common neurotrophin receptor p75NTR. J. Biol. Chem. 275:17566–17570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Casademunt, E., B.D. Carter, I. Benzel, J.M. Frade, G. Dechant, and Y.-A. Barde. 1999. The zinc finger protein NRIF interacts with the neurotrophin receptor p75NTR and participates in programmed cell death. EMBO J. 18:6050–6061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Khursigara, G., J.R. Orlinick, and M.V. Chao. 1999. Association of the p75 neurotrophin receptor with TRAF6. J. Biol. Chem. 274:2597–2600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chittka, A., and M.V. Chao. 1999. Identification of a zinc finger protein whose subcellular distribution is regulated by serum and nerve growth factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96:10705–10710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Salehi, A.H., P.P. Roux, C.J. Kubu, C. Zeindler, A. Bhakar, L.-L. Tannis, J.M. Verdi, and P.A. Barker. 2000. NRAGE, a novel MAGE protein, interacts with the p75 neurotrophin receptor and facilitates nerve growth factor-dependent apoptosis. Neuron. 27:279–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hantzopoulos, P.A., C. Suri, D.J. Glass, M.P. Goldfarb, and G.D. Yancopoulos. 1994. The low affinity NGF receptor, p75, can collaborate with each of the Trks to potentiate functional responses to the neurotrophins. Neuron. 13:187–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Martin-Zanca, D., R. Oskam, G. Mitra, T. Copeland, and M. Barbacid. 1989. Molecular and biochemical characterization of the human Trk proto-oncogene. Mol. Cell. Biol. 9:24–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Felgner, P.L., T.R. Gadek, M. Holm, R. Roman, H.W. Chan, M. Wenz, J.P. Northrop, G.M. Ringold, and M. Danielsen. 1987. Lipofection: a highly efficient, lipid-mediated DNA-transfection procedure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 84:7413–7417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ross, A.H., P. Grob, M. Bothwell, D.E. Elder, C.S. Ernst, N. Marano, B.F. Ghrist, C.C. Slemp, M. Herlyn, B. Atkinson, and H. Koprowski. 1984. Characterization of nerve growth factor receptor in neural crest tumors using monoclonal antibodies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 81:6681–6685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Spector, D.L., D.D. Goldman, and L.A. Leinwald. 1998. Culture and Biochemical Analysis of Cells. Cell: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. pp. 15.6–15.7.

- 58.Behl, C., J.B. Davis, R. Lesley, and D. Schubert. 1994. Hydrogen peroxide mediates amyloid β protein toxicity. Cell. 77:817–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Suzuki, A. 1997. Amyloid β-protein induces necrotic cell death mediated by ICE cascade in PC12 cells. Exp. Cell Res. 234:507–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Oh, J.D., K. Chartisathian, T.N. Chase, and L.L. Butcher. 2000. Overexpression of neurotrophin receptor p75 contributes to the excitotoxin-induced cholinergic neuronal death in rat basal forebrain. Brain Res. 853:174–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Johnson, D., A. Lanahan, C.R. Buck, A. Sehgal, C. Morgan, E. Mercer, M. Bothwell, and M. Chao. 1986. Expression and structure of the human NGF receptor. Cell. 47:545–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cheng, B., S. Christakos, and M.P. Mattson. 1994. Tumor necrosis factors protect neurons against metabolic-excitotoxic insults and promotes maintenance of calcium homeostasis. Neuron. 12:139–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Barger, S.W., D. Horster, K. Furukawa, Y. Goodman, J. Krieglstein, and M.P. Mattson. 1995. Tumor necrosis factors α and β protect neurons against amyloid β-peptide toxicity: evidence for involvement of a κB-binding factor and attenuation of peroxide and Ca2+ accumulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 92:9328–9332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chao, C.C., and S. Hu. 1994. Tumor necrosis factor-α potentiates glutamate neurotoxicity in human fetal brain cell cultures. Dev. Neurosci. 16:172–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Blasko, I., T.L. Schmitt, E. Steiner, K. Trieb, and B. Grubeck-Loebenstein. 1997. Tumor necrosis factor α augments amyloid β protein (25-35) induced apoptosis in human cells. Neurosci. Lett. 238:17–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Konno, T. 2001. Amyloid-induced aggregation and precipitation of soluble proteins: an electrostatic contribution of the Alzheimer's β(25-35) amyloid fibril. Biochemistry. 40:2148–2154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shamovsky, I.L., G.M. Ross, R.J. Riopelle, and D.F. Weaver. 1999. The interaction of neurotrophins with the p75NTR common neurotrophin receptor: a comprehensive molecular modeling study. Protein Sci. 8:2223–2233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yamashita, T., K.L. Tucker, and Y.A. Barde. 1999. Neurotrophin binding to the p75 receptor modulates Rho activity and axonal outgrowth. Neuron. 24:585–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Khursigara, G., J. Bertin, H. Yano, H. Moffett, P.S. DiStefano, and M.V. Chao. 2001. A prosurvival function for the p75 receptor death domain mediated via the caspase recruitment domain receptor-interacting protein 2. J. Neurosci. 21:5854–5863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rabizadeh, S., X. Ye, S. Sperandio, J.J. Wang, H.M. Ellerby, L.M. Ellerby, C. Giza, R.L. Andrusiak, H. Frankowski, et al. 2000. Neurotrophin dependence domain. J. Mol. Neurosci. 15:215–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang, X., J.H. Bauer, Y. Li, Z. Shao, F.S. Zetoune, E. Cattaneo, and C. Vincenz. 2001. Characterization of a p75NTR apoptotic signaling pathway using a novel cellular model. J. Biol. Chem. 276:33812–33820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Strasser, A., L. O'Connor, and V.M. Dixit. 2000. Apoptosis signaling. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69:217–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Troy, C.M., S.A. Rabacchi, W.J. Friedman, T.F. Frappier, K. Brown, and M.L. Shelanski. 2000. Caspase-2 mediates neuronal cell death induced by β-amyloid. J. Neurosci. 20:1386–1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Harada, J., and M. Sugimoto. 1999. Activation of caspase-3 in β-amyloid-induced apoptosis of cultured rat cortical neurons. Brain Res. 842:311–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ivins, K.J., P.L. Thornton, T.T. Rohn, and C.W. Cotman. 1999. Neuronal apoptosis induced by β-amyloid is mediated by caspase-8. Neurobiol. Dis. 6:440–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Reilly, C.E. 2000. β-amyloid of Alzheimer's disease activates an apoptotic pathway via caspase-8. J. Neurol. 247:155–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nakagawa, T., H. Zhu, N. Morishima, E. Li, J. Xu, B.A. Yankner, and J. Yuan. 2000. Caspase-12 mediates endoplasmic-reticulum-specific apoptosis and cytotoxicity by amyloid-β. Nature. 403:98–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Allen, J.W., B.A. Eldadah, X. Huang, S.M. Knoblach, and A.I. Faden. 2001. Multiple caspases are involved in β-amyloid-induced neuronal apoptosis. J. Neurosci. Res. 65:45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gu, C., P. Casaccia-Bonnefil, A. Srinivasan, and M.V. Chao. 1999. Oligodendrocyte apoptosis mediated by caspase activation. J. Neurosci. 19:3043–3049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yuan, J., and B.A. Yankner. 2000. Apoptosis in the nervous system. Nature. 407:802–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]