Boosting antitumor responses of T lymphocytes infiltrating human prostate cancers (original) (raw)

Abstract

Immunotherapy may provide valid alternative therapy for patients with hormone-refractory metastatic prostate cancer. However, if the tumor environment exerts a suppressive action on antigen-specific tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL), immunotherapy will achieve little, if any, success. In this study, we analyzed the modulation of TIL responses by the tumor environment using collagen gel matrix–supported organ cultures of human prostate carcinomas. Our results indicate that human prostatic adenocarcinomas are infiltrated by terminally differentiated cytotoxic T lymphocytes that are, however, in an unresponsive status. We demonstrate the presence of high levels of nitrotyrosines in prostatic TIL, suggesting a local production of peroxynitrites. By inhibiting the activity of arginase and nitric oxide synthase, key enzymes of L-arginine metabolism that are highly expressed in malignant but not in normal prostates, reduced tyrosine nitration and restoration of TIL responsiveness to tumor were achieved. The metabolic control exerted by the tumor on TIL function was confirmed in a transgenic mouse prostate model, which exhibits similarities with human prostate cancer. These results identify a novel and dominant mechanism by which cancers induce immunosuppression in situ and suggest novel strategies for tumor immunotherapy.

Human tumors express antigens recognized by T and B lymphocytes, a recent discovery that has paved the way for the development of novel immunotherapeutic strategies targeting the immune effectors toward cancer-associated antigens (1, 2). Unfortunately, the many attempts to create a therapeutic cancer vaccine for human tumors have been unsuccessful. Although vaccination often succeeds in expanding circulating T lymphocytes recognizing the autologous tumor, only a limited number of clinically objective responses have been reported so far (3). T lymphocytes activated by vaccination acquire an antigen-experienced memory phenotype, and they are virtually competent to attack neoplastic cells (4, 5). Thus, inefficacy of active immunotherapy probably depends either on the inability of sufficient lymphocyte numbers to reach the site of cancer growth or on the countermeasures orchestrated by tumor cells. Tumor escape mechanisms are quite diversified; they include loss of antigen, HLA molecules, or key proteins of the antigen-processing machinery; local production of immunosuppressive molecules; recruitment and activation of suppressive myeloid cells; and loss of costimulatory molecules (6).

Among cancer patients undergoing active immunotherapy, those showing mixed responses are particularly intriguing (7). In clinical trials, in fact, some tumor nodules regress or disappear, whereas in the same patient others progress. The reasons for this heterogeneous response are not clear, but it was proposed that tumor nodules might have different permissive states toward the activity of anti-tumor lymphocytes (7). The interactions between lymphocytes, tumors, and tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells can create a number of functional events that range from full activation of specific immune responses to the induction of tolerance in tumor-specific T lymphocytes (8, 9). However, in general, the tumor microenvironment does not seem to be suitable for T lymphocyte functions, and, indeed, a number of reports indicate that tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL) are impaired in both signal transduction and effector systems (10). These findings have been obtained mostly in nonvaccinated tumor-bearing hosts, but it is reasonable to assume that the same constrains might apply to lymphocytes activated by active immunotherapy once they reach the tumor site.

The control of amino acid metabolism is emerging as a relevant immunoregulatory tool shared by different cell types of the immune system, which can also underlie the immune dysfunctions induced by tumors. The activation of the tryptophan-degrading enzyme indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase in dendritic cells, originally associated with peripheral tolerance and maternal tolerance toward the fetus, was recently shown to be involved in tumor immune evasion. In two different tumor models, systemic administration of a specific indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase inhibitor resulted in partial reversion of the tumor-induced immunosuppression (11, 12).

Tryptophan is not the only amino acid whose metabolism is increased in a tumor-conditioned microenvironment, and numerous reports suggest also a role for the activation of L-arginine (L-Arg) metabolizing enzymes during tumor growth and development. In tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells, L-Arg is metabolized by arginase I (ARG1), arginase II (ARG2), and by the inducible form of nitric oxide synthase (NOS2). Cytoplasmic ARG1 and mitochondrial ARG2 hydrolize L-Arg to urea and ornithine, the latter being converted to polyamines by ornithine decarboxylase (13). NOS2 oxidizes L-Arg to citrulline and nitric oxide (NO), a pleiotropic molecule important for ischemia, inflammation, angiogenesis, immune response, and cell growth and differentiation (14).

Increased ARG activity has long been detected in patients with colon, breast, lung, and prostate cancer (15), and it was proposed that this enzymatic activity sustained the high demand of polyamines necessary to tumor growth (16). However, ARG activity in macrophages infiltrating a mouse tumor was recently shown to impair antigen-specific T cell responses and the expression of the CD3 ζ chain (17). Increased production of NO within various human cancers may contribute to tumor development by favoring neoangiogenesis, tumor metastasis, and tumor-related immune suppression (18). It is commonly believed that ARG and NOS are competitively regulated by Th1 and Th2 cytokines and complex intracellular biochemical pathways, including negative feed-back loops and competition for the same substrate (13). However, simultaneous activation of ARG and NOS in myeloid cells licensed by the tumor can generate powerful inhibitory signals, eventually leading to apoptotic death of antigen-specific T lymphocytes (19, 20).

Evidence has been accumulating that ARG and NOS are overexpressed in prostate cancers as compared with hyperplasic prostate (21–23), with the intriguing observation that the tumor cells, rather than myeloid infiltrating cells, could be the main source of the enzymes. We investigated whether the alteration of L-Arg metabolism in tumor explants could be responsible for the induction of TIL dysfunctions. When small tumor samples are cultured in medium containing a combination of ARG- and NOS-specific inhibitors, TIL recover their functions, suggesting the presence of a predominant immunosuppressive mechanism based on the altered L-Arg metabolism in prostate cancer.

RESULTS

Phenotypic analysis of prostate tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

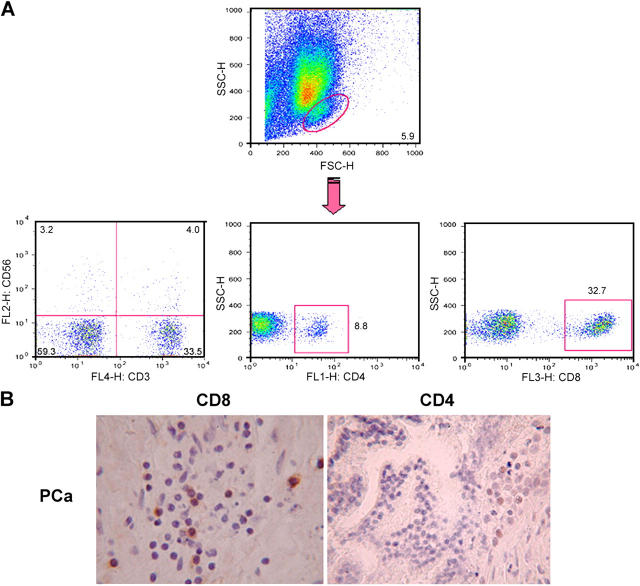

To characterize the phenotype of T lymphocytes infiltrating human prostate carcinoma (PCa), prostate samples obtained from untreated patients who underwent radical prostatectomy for PCa were analyzed by FACS (BD Biosciences) analysis and immunohistochemistry. Initial studies revealed that TIL infiltrating PCa samples were mainly CD8+ T lymphocytes (Fig. 1, A and B); therefore the following experiments were focused on CD8+ TIL.

Figure 1.

CD8**+** TIL infiltrate malignant prostate. (A) Single-cell suspensions obtained from 50 prostate samples were incubated with antibodies to various T cell markers and analyzed by flow cytometry. A representative experiment is reported. (B) Immunocytochemical detection of CD8+ or CD4+ TIL in PCa tissues (magnification, ×400).

CTL are one of the critical effector cells in antitumor immunity (24). T cell differentiation from naive to effector CTL can be analyzed through the expression of CCR7 and CD45RA molecules (25). In PCa samples, CD8+ TIL were either CCR7−CD45RA−CD62L− (effector memory phenotype) or CCR7−CD45RA+CD62L− (terminally differentiated CTL) (Table I). Consistent with their phenotype of terminally differentiated cytotoxic cells, CD8+ T lymphocytes infiltrating PCa expressed low levels of chemokine receptors; an exception was CCR5, which is known to be expressed in tissue-infiltrating lymphocytes. These cells contained perforin granules, indicating that activated and armed CTL are present within the tumor site (Table I). Interestingly, CD8 TIL expressed high levels of activatory NK receptors, such as p50.3, NKRP1A, NKG2D, and CD94 (Table I).

Table I.

Phenotypic analysis of CD8+ T cells infiltrating human PCa

| Antigen | Expression | No. of patientsanalyzed |

|---|---|---|

| T cell markers | ||

| CD5 | +++a | 4 |

| CD7 | +++ | 4 |

| CD11a | +++ | 4 |

| CD25 | − | 50 |

| CD26 | − | 4 |

| CD27 | − | 4 |

| CD28 | − | 25 |

| CD31 | − | 4 |

| CD45RA | + | 12 |

| CD62L | +/− | 12 |

| CD69 | + | 50 |

| CD137 | − | 50 |

| NK receptors | ||

| p50.3 | ++ | 4 |

| p58.1 | − | 4 |

| p58.2 | − | 4 |

| NKAT | − | 4 |

| NKB1 | − | 4 |

| NKG2A | ++ | 4 |

| NKG2C | − | 4 |

| NKG2D | ++ | 4 |

| NKRP1A | +++ | 4 |

| NKp30 | − | 4 |

| NKp44 | − | 4 |

| NKp46 | − | 4 |

| CD94 | ++ | 4 |

| Chemokine receptors | ||

| CCR4 | − | 4 |

| CCR5 | +++ | 4 |

| CCR6 | − | 4 |

| CCR7 | − | 12 |

| CXCR1 | − | 4 |

| CXCR2 | − | 4 |

| CXCR3 | ++ | 4 |

| CXCR4 | ++ | 4 |

| Functional marker | ||

| Perforin | +++ | 12 |

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte activation in prostate carcinoma organ cultures

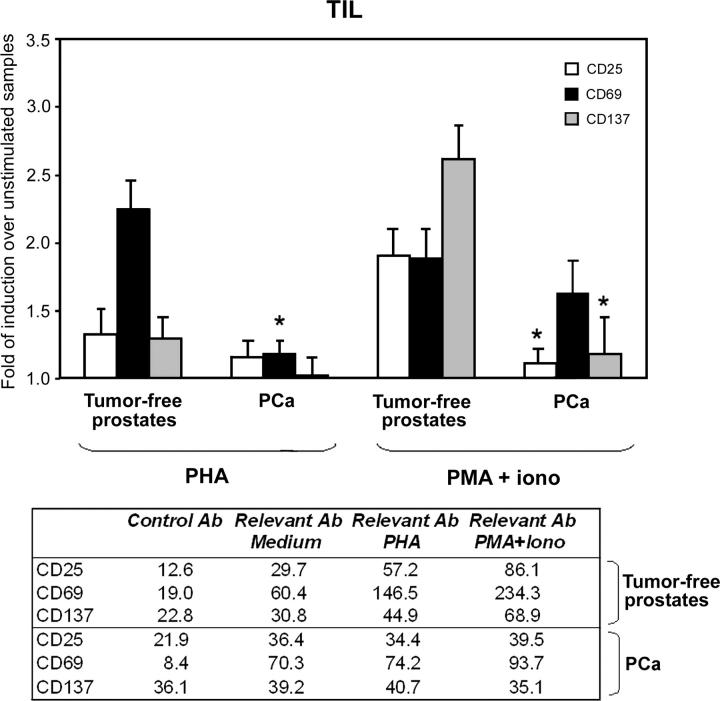

Several studies have documented signaling defects in TIL, and it has been proposed that the tumor itself, or host cells present in the tumor environment, directly inhibits TIL activation (26, 27). To study the effect of prostate tumor environment on T lymphocyte activation, TIL were stimulated in situ, using collagen gel matrix–supported organ cultures of PCa and tumor-free prostates (obtained from patients who underwent radical prostatectomy for bladder cancer). The advantage of using PCa organ cultures is that the tumor microenvironment remains intact during the experiment. Thus, all the factors that may affect TIL function, such as cell–cell interactions, cell–matrix interactions, and interstitial fluid within this three-dimensional milieu, are preserved (28). We found that, although CD8+ T lymphocytes in tumor-free samples responded to the stimuli provided (i.e., PHA or PMA plus ionomycin), as shown by up-regulation of activation markers, CD8+ TIL from PCa samples were totally unresponsive to stimulation (Fig. 2). TIL responsiveness was not restored by the addition of IL-2 to the culture medium (unpublished data). In contrast, peripheral blood CD8+ T cells obtained from PCa patients or healthy donors were similar in responsiveness to the provided stimuli (Fig. 3), thus excluding the possibility that the PCa patients analyzed were immunodepressed. Taken together, these data suggest that the PCa environment is immunosuppressive for CD8+ T cells.

Figure 2.

TIL in PCa organ cultures are unresponsive. PCa (n = 20) and tumor-free prostate (n = 10) samples were cultured for 48 h in the presence or in the absence of PHA (1 μg/ml) or PMA (50 ng/ml) plus ionomycin (0.5 μg/ml). After enzymatic digestion, the single-cell suspensions obtained from prostate were incubated with antibodies to CD8 plus antibodies to CD25, CD69, and CD137. Flow cytometric analyses were gated on CD8+ lymphocytes. Similar results were obtained when prostate samples were cultured in the presence of IL-2 (100 U/ml). Results are expressed as fold of induction above the mean fluorescence intensity of unstimulated samples, which was taken as 1. *, P < 0.05 compared with tumor-free prostate samples. Mean fluorescence intensity values from a representative experiment are shown in the accompanying table.

Figure 3.

PBL of PCa patients have normal responses to stimuli. PBL from healthy donors (n = 10) or from the same PCa patients whose prostate samples were analyzed as described in Fig. 2 (n = 20) were cultured for 48 h in the presence or in the absence of PHA (1 μg/ml) or PMA (50 ng/ml) plus ionomycin (0.5 μg/ml). Cells were incubated with antibodies to CD8 plus antibodies to CD25, CD69, and CD137. Flow cytometric analyses were gated on CD8+ lymphocytes. Similar results were obtained when all CD3+ T cells were analyzed. Results are expressed as fold of induction above the mean fluorescence intensity of unstimulated samples, which was taken as 1.

Arginine and nitric oxide synthase mediate prostate carcinoma immunosuppression

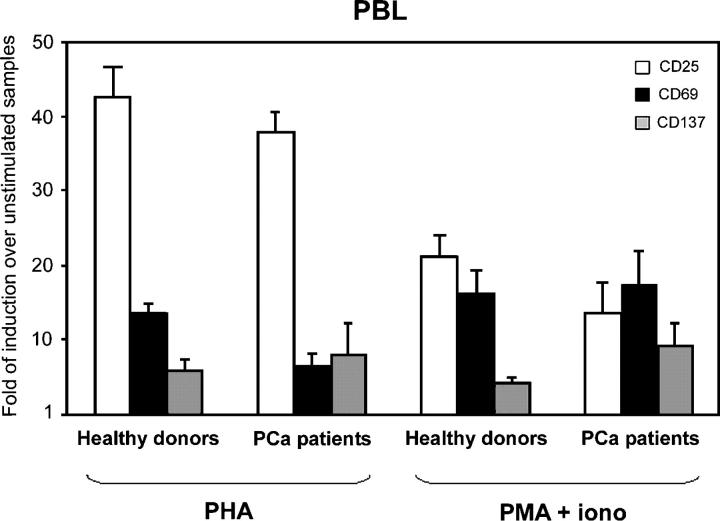

It has been proposed that alterations of L-Arg metabolism in the tumor environment could impair T cell functions (20). NOS2 is expressed in the prostate of various species, including humans. Up-regulated NOS2 expression was demonstrated in PCa and was shown to be predictive of poor survival (23). Together with the enzyme diamine oxidase, ARG controls polyamine metabolism in prostatic tissue. Experimental evidence indicates that ARG activity is elevated in PCa tissues as compared with benign prostatic hyperplasia, suggesting that this enzyme might play a role in the PCa progression (21). In the light of these data, tumor-free and PCa samples were subjected to immunohistochemical analyses for NOS2 and ARG2. We found that the expression of both enzymes was highly up-regulated in the tumor tissues (Fig. 4). This finding prompted us to investigate whether the two enzymes might be involved in the selective T cell unresponsiveness that we observed in PCa. Tumor tissue cultures were incubated for 4 d in the presence or in the absence of specific inhibitors of NOS (l-NMMA) and ARG (NOHA); then CD8+ T cell phenotype was analyzed. In 64% of the patients analyzed (n = 33), CD8+ T cells infiltrating tumor tissue cultures treated with l-NMMA and NOHA spontaneously up-regulated the expression of the early-activation markers CD25, CD69, and CD137 (Fig. 5 A). Up-regulation of activation markers was not the result of a direct effect of l-NMMA and NOHA on TIL, because the expression of the same molecules in CD8+ T cells infiltrating tumor-free prostates treated with the same protocol did not change (unpublished data). Moreover, if the treatment with NOS and ARG inhibitors was prolonged for 7 d, the number of viable CD8+ T cells in PCa organ cultures was significantly higher than in untreated tumors (0.70 ± 0.29% vs. 0.22 ± 0.08% of the gated, live cells recovered after tumor dissociation), indicating that treatment with NOS and ARG inhibitors prevents T cell death in the tumor samples (Fig. 5 B). It is important to note that, in every experiment, each prostate sample was divided in two parts; one part was cultured with inhibitors and the other in normal medium. Only samples from the same patient were compared. Thus, the different phenotypes of TIL in treated or untreated samples can ascribed only to the inhibitor's effects, not to individual variability among the samples. When the two enzymes were not used in combination (i.e., when only NOS or only ARG activity was inhibited), TIL phenotype remained unmodified, indicating that both pathways must be blocked to reverse T cell inhibition (unpublished data).

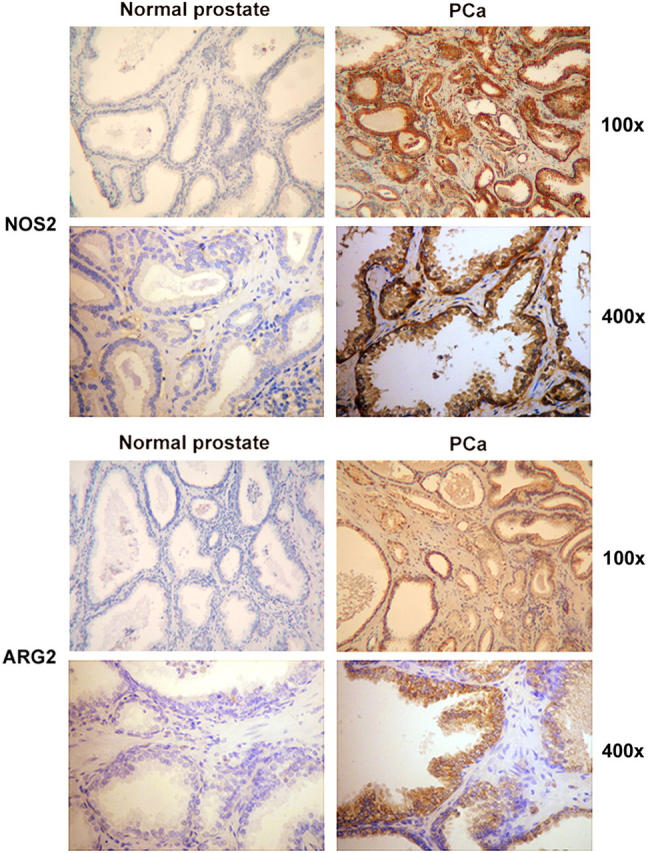

Figure 4.

Higher expression of NOS2 and ARG2 in PCa tissues than in tumor-free prostatic tissues. Immunohistochemical detection of NOS2 and ARG2 in control (n = 2) and malignant prostatic tissues (n = 4).

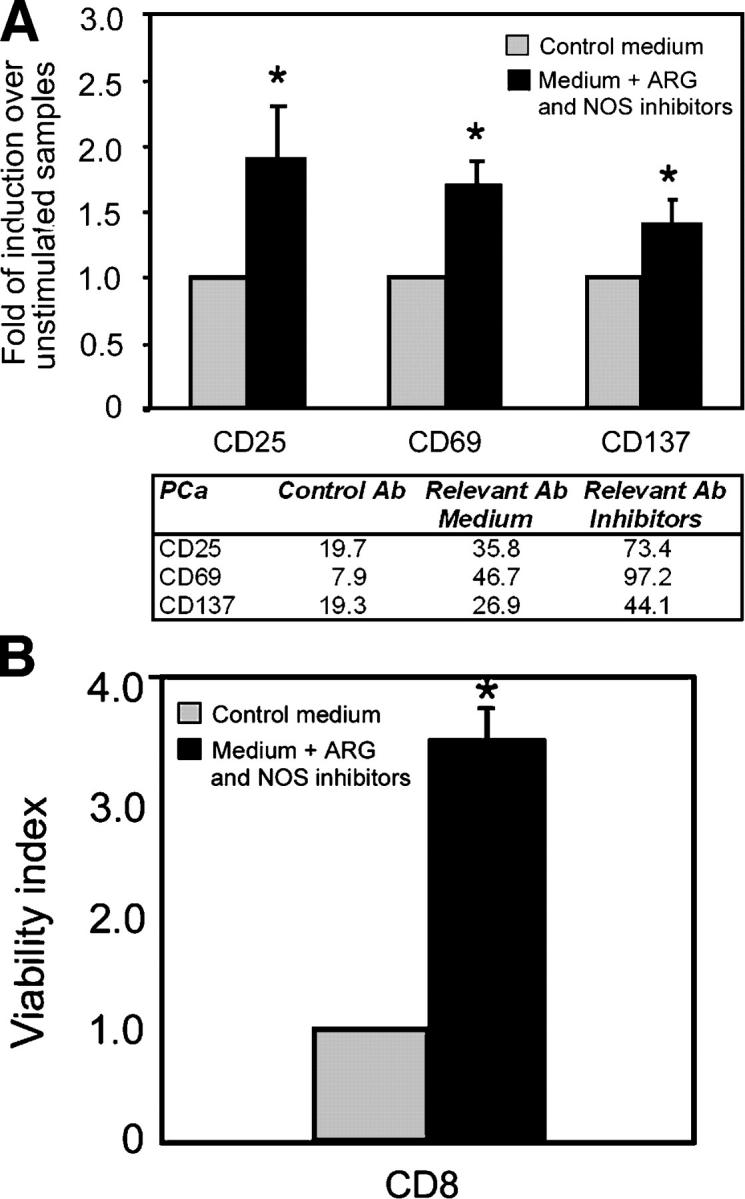

Figure 5.

ARG2 and NOS2 mediate PCa immunosuppression. PCa tissues were cultured 4 d in the presence or in the absence of NOS (l-NMMA; 0.5 mM) plus ARG (NOHA, 0.5 mM) inhibitors. (A) After 4 d of culture, the PCa tissues (n = 33) were digested, and the cell suspensions obtained were incubated with antibodies to CD8 plus antibodies to CD25, CD69, and CD137. Flow cytometric analyses were gated on CD8+ lymphocytes. Results are expressed as fold of induction above the mean fluorescence intensity of untreated samples of the same patient, which was taken as 1 . *, P < 0.05 compared with untreated samples. Mean fluorescence intensity values from a representative experiment are shown in the accompanying table. (B) After 7 d of culture, the PCa tissues (n = 21) were digested, and the cell suspensions obtained were incubated with antibodies to CD8 plus propidium iodide (PI). Data are presented as viability index over untreated tumor cultures of the same patients (number of CD8+ PI− cells in treated samples/number of CD8+ PI− cells in untreated samples).

Arginine and nitric oxide synthase activities induce tyrosine nitration in tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

We then tried to investigate the downstream events of ARG- and NOS-mediated immunosuppression in PCa. It has been proposed that under conditions of low L-Arg concentrations caused by enhanced ARG activity, NOS generates O2 − that reacts with NO to generate peroxynitrites (ONOO−) that, in turn, cause protein tyrosine nitration and inhibit activation-induced protein tyrosine phosphorylation (29, 30). To test this hypothesis, we analyzed PCa samples, precultured in the presence or in the absence of l-NMMA and NOHA, for nitrotyrosine expression. PCa tissues contained several cells highly positive for nitrotyrosine staining (Fig. 6 A). Interestingly, in PCa samples cultured in the presence of ARG and NOS inhibitors, the number of nitrotyrosine-expressing cells was considerably decreased (Fig. 6 A), indicating that protein nitration is not permanent and that possible denitration mechanisms might exist within the tissue (31, 32).

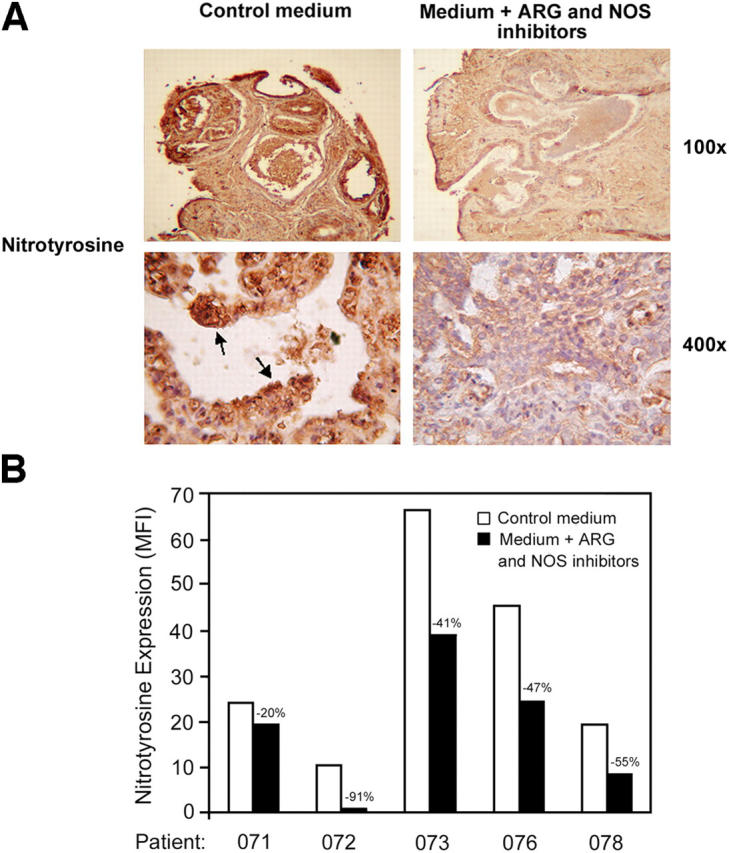

Figure 6.

ARG and NOS inhibitors reduce the level of nitrotyrosines in PCa tissues and in TIL. PCa samples (n = 6) were cultured 4 d in the presence or in the absence of NOS (l-NMMA; 0.5 mM) plus ARG (NOHA; 0.5 mM) inhibitors. (A) Immunohistochemical detection of nitrotyrosines in treated or untreated samples. Arrows indicate highly positive cells present only in untreated PCa tissues. (B) Flow cytometric analysis for nitrotyrosine expression in CD8+ cells infiltrating treated or untreated PCa samples.

To associate T cell dysfunctions with nitrotyrosine generation, it was essential to show the presence of nitrotyrosines in CD8+ TIL. Therefore, PCa samples were analyzed for nitrotyrosine expression by flow cytometric analyses. Nitrotyrosines were present in PCa TIL, and treatment with ARG and NOS inhibitors reduced their expression (Fig. 6 B), indicating that in PCa the enhanced activity of the enzymes ARG and NOS generates peroxynitrite responsible for tyrosine nitration and in situ immunosuppression of TIL.

Arginine and nitric oxide synthase inhibitors restore local tumor recognition by tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

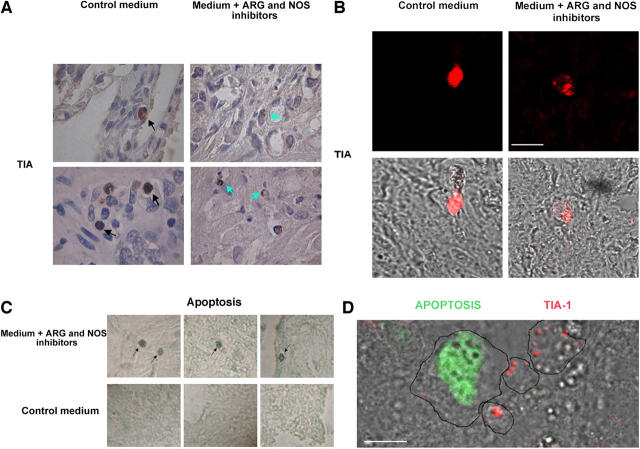

Frey and collaborators have shown that murine CD8+ TIL do contain cytolytic granules, but these granules are diffused in the cytoplasm and do not polarize in response to T cell stimulation (33). Moreover, they showed that recovery of lytic function, after isolation and culture of TIL, correlated with the capacity of TIL to mobilize and polarize cytotoxic granules. We decided to analyze the subcellular localization of cytolytic granules in CTL infiltrating PCa samples untreated or incubated for 4 d with ARG and NOS inhibitors. A cytotoxic granule–associated protein, TIA-1, was used as a specific granule marker (34, 35). Immunohistochemical and immunofluorescence analysis revealed that lytic granules were evenly distributed in the cytoplasm of CD8+ T cells present in PCa samples, suggesting that CTL do not engage productive contacts or are unable to organize a mature immunological synapse inside the tumor (Fig. 7, A and B). However, when PCa samples were precultured with l-NMMA and NOHA, the subcellular distribution of CTL lytic granules seemed to be polarized in a restricted region of the cytoplasm, suggesting that functional immunological synapses between CTL and target cells were organized (Fig. 7, A and B). TIA-1+ cells present in PCa samples, treated or untreated with ARG and NOS inhibitors, from three different patients were counted. We found that tumor tissues preincubated or not with l-NMMA and NOHA had comparable numbers of TIA-1+ cells. However, polarized granules were expressed by less than 10% of the positive cells in untreated tumors, whereas more than 90% of TIA-1+ cells displayed a polarized phenotype in tumors incubated with ARG and NOS inhibitors.

Figure 7.

ARG and NOS inhibitors restore CTL lytic function. (A) Immunohistochemical detection of TIA-1 in PCa samples (n = 10) cultured 4 d in the presence or in the absence of NOS (l-NMMA; 0.5 mM) plus ARG (NOHA; 0.5 mM) inhibitors. The pictures show that in untreated tumor samples cytotoxic granules are evenly distributed in the cytoplasm of CTL (black arrow). In contrast, in tumor samples cultured with inhibitors, CTL cytotoxic granules appear polarized in a confined region of the cell (green arrow: magnification, ×1,000). In each experimental condition, 500 TIA-1+ cells were analyzed. In untreated samples, we counted 23 TIA-1+ cells showing a polarized phenotype (4.6%), whereas in samples cultured in the presence of ARG and NOS inhibitors we counted 461 polarized cells (92.2%). (B) Similar results were obtained by immunofluorescence analysis of TIA-1+ cells. Bar, 10 μm. (C) Immunohistochemical detection of apoptosis by TUNEL assay in PCa samples (n = 10) cultured 4 d in the presence or in the absence of NOS (l-NMMA; 0.5 mM) plus ARG (NOHA; 0.5 mM) inhibitors. Apoptotic cells are indicated (black arrow). In untreated tissues, apoptotic cells were always less than two/sample, whereas in inhibitor-treated tissues we counted >20 apoptotic cells per sample (magnification, ×600). (D) Immunofluorescence analysis of TIA-1+ cells and apoptosis. PCa samples (n = 10) cultured 4 d in the presence of NOS (l-NMMA; 0.5 mM) plus ARG (NOHA; 0.5 mM) inhibitors stained for TIA-1 (red) and subsequently for DNA fragmentation by TUNEL assay (green). Samples were analyzed by confocal microscopy. Bar, 10 μm. Cell margins were drawn to facilitate the readers.

Polarization and release of CTL lytic granules result in killing of the target cell. Thus, we analyzed PCa tissue cultures, preincubated or not with ARG and NOS inhibitors, for the presence of apoptotic cells. Apoptosis was almost undetectable in untreated tumor tissue cultures (less than two apoptotic cells/sample), but more than 20 isolated apoptotic cells per sample were present in tissues incubated with l-NMMA and NOHA, suggesting that selective killing had occurred (Fig. 7 C). The possibility that the inhibitors used directly induce cell death can be ruled out because (a) few and isolated apoptotic cells were present in the tissues, and (b) the number of apoptotic cells correlated with the number of TIA-1+ cells.

To clarify the identity of the apoptotic cells and the role of cytotoxic T cells in mediating the observed apoptosis in tumor samples treated with NOS and ARG inhibitors, we performed a double staining for TIA-1 and apoptosis (Fig. 7 D). The results indicate that apoptotic cells are not lymphocytes but are surrounded by TIA-1+ cells, thus strengthening evidence for the role of CTL in mediating apoptosis inside the tumor.

Taken together, these data indicate that CTL infiltrating human prostate cancer are potentially able to kill tumor cells and that their in situ lytic function can be restored by inhibiting ARG2 and NOS2.

Arginine and nitric oxide synthase inhibitors restore antitumor activity in prostate carcinoma cultures of transgenic adenocarcinoma mouse prostate mice

We were not able to recover enough human T lymphocytes from PCa organ cultures to perform functional studies. We therefore decided to use a mouse model very close to the human pathology: the transgenic adenocarcinoma mouse prostate (TRAMP) mouse. These mice are transgenic for the SV40 large-antigen (Tag) oncogene under the control of the rat probasin regulatory element and express Tag at puberty. In the following weeks, TRAMP mice progressively develop spontaneous prostatic hyperplasia, adenocarcinoma, and lymph node and lung metastases, closely mimicking progression of human PCa (36). Another interesting analogy with human tumors directly concerns the scope of our studies: the invading, but not the normal, epithelium overexpresses both ARG and NOS (unpublished data). At 22–24 wk of age, prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and well-differentiated carcinoma comprised the majority of the pathology in TRAMP mice, but the tumor appearance was variable, ranging from microscopic tumors evidenced only histologically to macroscopically visible nodules in the pelvis where the individual mouse prostate lobes were indistinguishable (36). The first type of tumors was infiltrated by a sizeable number of CD8+ T lymphocytes (12.66 ± 1.09% of the gated, live cells recovered after tumor dissociation) with the phenotype of memory/effector cells, as assessed by the expression of CD62L, CD44, and CD25 (Fig. 8 A). In large tumors, the percentage of CD8+ T lymphocytes declined dramatically (0.15 ± 0.01% of gated cells), and these lymphocytes had almost completely lost the expression of CD25, the α chain of the IL-2 receptor (Fig. 8 A). Large tumors were then enzymatically dissociated, pooled, and cultured in the presence of high doses of IL-2 to expand TIL. Equivalent numbers of the same cellular preparation were cultured in the presence of the ARG and NOS inhibitors used in previous experiments, low doses of IL-2, or a combination of inhibitors and low IL-2 concentration. After 3 wk, TIL were recovered and tested for their ability to recognize different targets by releasing IFN-γ (Fig. 8 B). No TIL were recovered in cultures incubated only with the inhibitors (unpublished data), an expected result in the absence of IL-2 driving the expansion of the activated T lymphocytes. High-dose IL-2 allowed the highest cell recovery (3.48 × 106; 464-fold expansion), but TIL had a very high background IFN-γ release, which did not allow discriminating any tumor-specific recognition. Low-dose IL-2 combined with the ARG and NOS inhibitors allowed recovery of an intermediate number of TIL (2.56 × 106; 341-fold expansion) that recognized the autologous tumor, the syngeneic prostate cancer cell line TRAMP C1, and the SV40-infected fibroblast but not normal splenocytes or tumors of different histology (MBL-2 and B16 tumors), suggesting the expansion of tumor-specific and possibly SV40-restricted effectors. Low-dose IL-2 alone supported a lower expansion (138-fold; 1.24 × 106 total cells) of TIL that only partially recognized the autologous tumor and SV40+ fibroblasts but not TRAMP C1 cells (Fig. 8 B). These data confirm the relevance of ARG and NOS in restraining tumor-specific lymphocytes in PCa and suggest that the lymphocyte repertoire generated by altering the local L-Arg metabolism in the presence of IL-2 might be different from that obtained by the simple IL-2–driven activation.

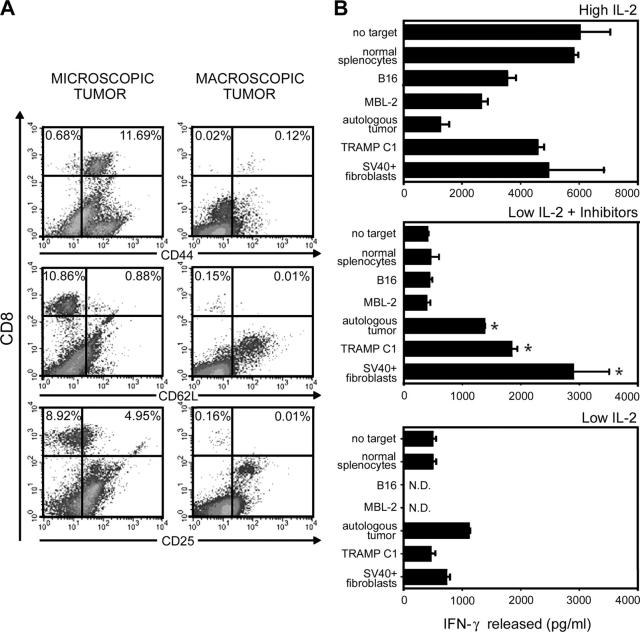

Figure 8.

ARG and NOS inhibitors are essential to restore full tumor recognition by TIL. (A) Single-cell suspensions obtained from three or four pooled prostate samples from TRAMP mice with small (left) and large (right) tumors, were incubated with antibodies to various T cell markers and analyzed by flow cytometry. A representative experiment is reported. (B) PCa large nodules from three TRAMP mice were enzymatically digested and, after removal of dead cells, were cultured in complete medium alone (to obtain the autologous tumor), in the presence of 100 IU/ml IL-2 (high IL-2), 10 IU/ml IL-2 (low IL-2), 0.5 mM l-NMMA plus 0.5 mM NOHA (inhibitors), or a combination of inhibitors and low-dose IL-2 (low IL-2 plus inhibitors). TIL recovered after 3 wk were used as effectors against a panel of target cells to evaluate the release of IFN-γ after 24-h coincubation. The percentage of CD8+ T lymphocytes in different preparations was greater than 80%. Data are from triplicate wells ± SE. The experiment was repeated twice and, although the cell recovery differed, results of the IFN-γ release assay were comparable. *, P < 0.05 compared with TIL cultured in low IL-2 alone.

DISCUSSION

A long-term clinical follow-up of more than 300 patients with prostate adenocarcinomas (PCa) showed a significant correlation between the TIL density and prognosis (37). Absent or weak TIL were found to be signs of increased tumor progression risk and poor prognosis. However, a major limit of similar epidemiological studies (38) is that lymphocytic infiltration is present in benign hyperplasia as well, leaving unanswered the question whether TIL represent a lymphocytic nonspecific inflammation or a true, evolving tumor-specific immune response. In many melanomas, it has been conclusively shown that TIL are directed against either melanocyte differentiation antigens or mutated proteins, and they can be expanded ex vivo to exert antitumor activity after adoptive transfer to the patient (39). In the case of prostate cancer, there are few reports. However, peptide-pulsed autologous DC were able to stimulate prostate TIL and induce recognition of an HLA-A2-restricted epitope of the antigen parathyroid hormone-related protein, suggesting that TIL separated from their surrounding environment possess full antigen responsiveness (40). In some cases TIL from PCa, isolated and kept in culture in the presence of IL-2 for at least 14 d, were capable of killing tumor cells via perforin-dependent and -independent pathways only when tumor cells were previously treated with chemotherapeutic drugs (41).

Many of these studies, however, suffer from the limitation that T lymphocytes are activated after repeated in vitro stimulations in a disrupted tumor environment. Within the tumor site, tumor-specific lymphocytes are sensitive to any changes in the microenvironment, and these changes can condition their function and activation state. Most solid tumors are characterized by lymphocyte infiltration, but TIL frequently are unable to kill autologous tumor cells, indicating that they are in an anergic/tolerant state (26, 27, 42, 43). The data presented here provide new insight into the biology of T lymphocytes infiltrating human PCa. TIL within PCa are mainly CD8+ T lymphocytes with an antigen-experienced, terminally differentiated phenotype. However, they remain in a dormant state that is not altered by cytokines affecting T lymphocyte proliferation such as IL-2. Unlike normally responsive lymphocytes in tumor-free prostates and peripheral blood, TIL are not activated locally by powerful signals acting either on TCR or downstream signaling pathways. The steady-state regulation of the dormant state is dependent on the enhanced intratumoral metabolism of the amino acid L-Arg, because the simple addition of ARG- and NOS-specific inhibitors was sufficient to rouse these CTL, activate them, and start a number of events leading to cytolytic granule polarization and killing of cognate targets. These data were confirmed and extended in TRAMP mice, allowing us to evaluate the tumor-specific reactivity of TIL rescued from the dormant state by the ARG and NOS inhibitor and expanded by low doses of IL-2.

Our findings suggest that the L-Arg–metabolizing enzymes are up-regulated in prostate cancer cells rather than in tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells such as macrophages, although we cannot rule out the contribution of these latter cells. In line with our results, it is known that several tumor cell lines express high levels of ARG and that inhibition of arginase activity often abolishes in vitro cell growth (15). Our data, together with the recent literature, suggest that intratumoral arginase induction might be beneficial for the tumor through different pathways, i.e., supporting tumor growth and development by providing polyamines and suppressing antitumor immune response by negatively affecting TIL.

NOS activity has been detected in many human tumors, including prostate cancer, although its function is unclear (18, 23). NO stimulates angiogenesis, thus enhancing tumor growth and invasiveness (44). Moreover, NO induced an enhanced expression of the DNA-dependent protein-kinase catalytic subunit, DNA-PKcs, that should protect tumor cells from the damaging activity of NO and other DNA-damaging agents, such as X-ray radiation, Adriamycin, bleomycin, and cisplatin (45).

Depletion of cytosolic L-Arg content by ARG might trigger the generation of superoxide (O2 -) from the NOS2 reductase domain (46, 47). The reductase domain of NOS2 generates O2 − that reacts immediately with NO generated by the oxygenase domain. The chemical byproducts of this reaction are ONOO−, highly reactive oxidizing agents that nitrate protein-associate tyrosines and damage different biological targets (48). Cell membranes offer no significant barrier to diffusion of peroxynitrites from different compartments, within or between cells, at a rate that is faster than the known decomposition pathways of these moieties (49). This lack of a barrier indicates that, whenever O2 − and NO are generated from the same or different cells in a microenvironment, they will immediately associate, and the resulting ONOO− will diffuse freely through cell membranes.

A number of lines of evidence indicate that peroxynitrites are quite toxic for lymphocytes: they can prime T lymphocytes to undergo apoptotic cell death through different pathways involving inhibition of protein tyrosine phosphorylation via nitration of tyrosine residues (29, 30) or by nitration of the protein voltage-dependent anion channel, a component of mitochondrial permeability transition pore (50). Nitrotyrosine, a marker of peroxynitrite activity in tissues, is found in thymic extracts and thymic sections colocalized with apoptotic cells, suggesting that peroxynitrites are also involved in thymic apoptosis in vivo (29). Staining for nitrotyrosine in PCa tissue sections gave a diffuse pattern with some hot spots in the TIL. Whether T lymphocytes are more prone to the effect of ONOO− and their decomposition by-products or instead activate additional intracellular pathways for nitrotyrosine generation is not known. Indeed, recent data suggest that protein nitration can be considered a cellular signaling mechanism, because it is specific and reversible (51–53). Although the biochemical pathway responsible for tyrosine denitration is not known, our results indicate that CTL posses a mechanism capable of eliminating nitrotyrosines and rescuing T cell functions.

As in previous mouse studies, inhibition of both ARG and NOS was crucial to rescue T cell functions. We are currently investigating the mechanism for such synergy. However, in addition to having a synergistic activity in peroxynitrite generation, ARG and NOS can exert independent inhibitory activities on T lymphocytes, as shown in different tumor models. ARG depletes L-Arg in local microenvironments, leading to loss of the CD3 ζ chain in T lymphocytes and their functional paralysis after antigen recognition (17), whereas NO blocks the signaling through the IL-2 receptors of T lymphocytes by impeding phosphorylation of the intracellular signaling proteins STAT5, Akt, and Erk (20).

A number of studies have proposed that cancers induce immunosuppression by inhibiting CD3 ζ chain expression in T lymphocytes (for review see reference 54). We analyzed the expression of CD3 ζ chain in both PBL and TIL from PCa patients, but we were unable to demonstrate its down-regulation (unpublished data). Moreover, PBL from PCa patients responded normally to all the stimuli we provided, indicating that no evident signaling defects were present. In contrast, TIL from PCa patients were unresponsive even when stimulated with PMA plus ionomycin, stimuli that by-pass TCR signaling. Altogether, these data indicate that in PCa the ARG2 activity does not induce immunosuppression through CD3 ζ down-regulation.

Although it seems that the number of TIL in the tumor might correlate with prognosis (37, 38, 55), it is suggested that TIL are functionally deficient and that this deficiency is transient and attributable to the tumor environment because, on purification from tumor cells, tumor-specific killing can be detected (33, 56, 57). CTL kill their target cell by polarized secretion of their lytic granules at the immunological synapse (58, 59). Polarization and secretion of lytic granules are triggered by recognition of MHC class I–peptide complexes on the target cell through the T cell receptor (60). Therefore, our results showing that inhibition of ARG and NOS activities in the tumor results in spontaneous polarization of cytotoxic granules in TIL indicate that CD8+ T cells infiltrating prostate cancer are terminally differentiated cytotoxic T cells that are in contact with the target cell but are unable to kill because they are narcotized by the tumor environment. However, even inside the tumor, CTL activity can be restored pharmaceutically.

Based on our findings, drugs controlling ARG and NOS might be useful in aiding immunotherapeutic approaches for the treatment of cancer by creating a favorable tumor environment for the T lymphocyte effector program. Molecules are being developed to create novel isozyme-specific inhibitors for both NO synthases and arginases (61, 62), but more must be done to enhance selectivity. ARG1 is found at highest concentrations in the mammalian liver where it carries out the final cytosolic step of the urea cycle, a process that allows the disposal of nitrogenous waste. Arginase inhibitors might thus cause hyperammonemia and interfere with hepatic urea cycle. Moreover, some activities of inhibitors are not predictable. For example, the effect of Nω-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester, considered a selective NOS2 antagonist, requires reconsideration, because it can also inhibit arginase both in vivo and in vitro (63). Thus, the identification of the specific biochemical pathways responsible for immunosuppression, such as the protein nitration described here, may allow the development of more specific and less toxic immunoprotective molecules.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Prostate specimens.

This study was examined and approved by the Ethics Committee of the local Health and Social Services (Azienda Ospedaliera, Padova) in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki.

Prostate cancer specimens from 79 patients (aged 52–76 yr) who had undergone radical prostatectomy were obtained from the Department of Urology, Hospital of the University of Padova. None of these patients had received preoperative antitumor therapy. Benign prostates were obtained from patients who had undergone radical prostatectomy for bladder cancer (n = 18). Immediately after the surgery, the prostate specimens were divided and sent to the laboratory. Diagnosis was performed by a team of surgical pathologists at the Hospital.

Isolation of T cells from peripheral blood and tumor.

After removing necrotic areas and fat, 100–120-mm3 tumor specimens were washed in PBS and minced into small pieces using bistouries. From this tumor material 104–105 TIL were obtained after 2-h digestion at 37°C using a mixture of enzymes dissolved in RPMI 1640 medium (collagenase type IV, 1 mg/ml; deoxyribonuclease, 30 U/ml; and hyaluronidase, 0.1 mg/ml; all from Sigma-Aldrich). The resulting cell suspension was passed over a 30-μm filter, washed in RPMI 1640 medium (GIBCO BRL), and prepared for immunocytometric analysis.

PBL from both healthy donors and patients were isolated from heparinized blood by centrifugation on Ficoll gradient (Ficoll-Paque PLUS, Amersham Biosciences). PBL were cultured (37°C, 5% CO2) in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS, 1% l-glutamine, and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (all obtained from GIBCO BRL).

Prostate organ cultures.

Immediately after surgery, 100–120-mm3 tumor sections were brought to the laboratory. After removal of necrotic tissues, prostate samples were cut in 2–3-mm3 pieces and placed on presoaked collagen sponges (Johnson & Johnson) in complete RPMI 1640 medium (RPMI 1640 with 10% FCS, 1% l-glutamine, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 1% nonessential amino acids, and 1% sodium pyruvate).

Cultures were placed in six-well plates, and 3 ml of medium was added to each well to reach the upper part of the gel without submerging the prostate samples. Cultures were incubated at 37°C, in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2.

In some experiments, phytohemagglutinin (1 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) or phorbol myristate-acetate (50 ng/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) plus ionomycin (0.5 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich), with or without IL-2 (100 IU/ml; Chiron Corp.), were added to the cultures. In other experiments, _N_-hydroxy-l-arginine (0.5 mM; Cayman Chemical) and l-NMMA (0.5 mM; Cayman Chemical) were added to the cultures.

Monoclonal antibodies and flow cytometry.

The following panel of commercially available directly conjugated mAbs was included in this study: CD3, CD4, CD5, CD7, CD8, CD25, CD26, CD28, CD45RA, CD45RO, CD56, CD62L, CCR4, CXCR4, CCR5, CCR6, NKAT, NKB1, CD94, and antiperforin obtained from BD Biosciences; CD27 and CD31 obtained from Caltag Laboratories; CXCR3 and CCR7 obtained from R&D Systems; CD137 obtained from Ancell Corporation; NKp30, NKp44, NKp46, p50.3, p58.1, p58.2, NKG2A, and CD161 obtained from Immunotech; and mAb antinitrotyrosine obtained from Upstate Biotechnology. Intracellular markers (nitrotyrosine and perforin) were stained in cells previously fixed and permeabilized with a Fix and Perm kit (Caltag Laboratories) according to the manufacturer's manual.

The expression of these antigens on TIL and PBL was assessed by flow cytometry analysis (FACS-Calibur or FACS Canto; Becton Dickinson) using direct or indirect immunofluorescence assay combining up to six fluorescences (FITC, PE, PE-Cy5, PE-Cy7, APC, and APC-Cy7). A gate on CD8+ cells was defined for each sample, and dead cells were gated out based on their scatter properties and propidium iodide (25 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) incorporation. For the staining of mouse TIL, the following antibodies were used: rat anti–mouse CD8-Tri-color (0.1 μg/106 cells; clone CTCD8α, Caltag Laboratories); hamster anti–mouse CD3-FITC (1 μg/106 cells; clone 145-2C11, Caltag Laboratories); FITC- or BIOTIN-labeled rat anti–mouse CD62L, CD25, CD44 (BD Biosciences); and isotype-matched controls (Caltag Laboratories). Data were processed using CELLQUEST (Becton Dickinson) or FlowJo (Tree Star, Inc.).

Cell lines.

B16, a melanoma cell line of C57BL/6 (H-2b) provided by N. Restifo (Surgery Branch, National Institutes of Health), MBL2 (H-2b) a Moloney virus-induced lymphoma, and C57SV fibroblasts (H-2b SV40-transformed fibroblasts) provided by P.L. Lollini (Istituto di Cancerologia, Bologna, Italy) were maintained in DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine, 10 mM Hepes, 20 μM 2-ME, 150 U/ml streptomycin, 200 U/ml penicillin, and 10% heat-inactivated FCS (Invitrogen). TRAMP-C1, a cell line established from a primary tumor in the prostate of a PB-Tag C57BL/6 (TRAMP) mouse, was provided by N.M. Greenberg (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas). This cell line was maintained in DMEM high glucose (Invitrogen) supplemented with 2 mM l-glutamine, 10 mM Hepes, 20 μM 2-ME, 150 U/ml streptomycin, 200 U/ml penicillin, 10−8 DHT (Sigma-Aldrich), 5 μg/ml insulin (Sigma-Aldrich), and 5% heat-inactivated FCS (Invitrogen).

Mice.

6–8-wk-old male C57BL/6 (H-2b) mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories. TRAMP mice, a gift from N.M. Greenberg, were bred in our facility and used for experiment at age 22–24 wk. Procedures involving animals and their care were in conformity with institutional guidelines that comply with national and international laws and policies.

Mouse tumor-infiltrating leukocyte generation.

Tumor prostates were surgically removed from TRAMP mice. Enzyme medium (DNase, 300 U/ml, + hyaluronidase, 0.1%, + collagenase, 1%) was used for the dissociation of tumor biopsies to single-cell suspensions. After Ficoll centrifugation, these suspensions were cultured for TIL outgrowth. In brief, 0.5 × 106 cells were cultured in 24-well plates in 2 ml of DMEM/10% FCS with IL-2 and/or enzyme inhibitors, as specified in Results. Cultures were maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2, and 1 ml of exhausted medium was replaced every 4 d. When used as target cells, normal splenocytes were derived from the spleen of C57BL/6 mice.

ELISA.

Mouse TIL (105 cells) from 3-wk cultures were coincubated for 24 h with an equal number of target cells. The supernatant was then harvested and tested for released IFN-γ in a sandwich ELISA assay (Endogen), following the manufacture's instructions. Data were derived from triplicate wells.

Immunohistochemistry.

4-μm tissue sections were cut from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue blocks. After deparaffination, antigen retrieval was performed by microwave heating according to the manufacturer's instructions. For TIA-1 staining, tissue sections were heated in 10 mM buffered citrate, pH 6.0 (UCS Diagnostics), 750 W for 15 min. Slides were cooled at room temperature for 30 min. Sections were incubated with the primary antibodies (anti-CD4, clone 1F6, 1:40 dilution, Novo Castra; anti-CD8, clone C/144B, dilution 1:50, DakoCytomation; anti-iNOS1, dilution 1:50, Lab Vision Corporation; anti-ARG2, clone H-64, dilution 1:200, Santa Cruz Biotechnology; Inc.; anti-TIA1, clone 2G9, dilution 1:100, Immunotech; antinitrotyrosine, dilution 1:200, Upstate Biotechnology) at 37°C for 1 h. Binding antibodies were detected using biotinylated secondary antibody and avidin-conjugated horseradish peroxidase (Ultra-tek HRP antipolyvalent SCY, TECK Laboratories). Peroxidase activity was visualized with diaminobenzidine as a chromogen. Counterstaining with light hematoxylin for 1 min was performed to visualize nuclei. Substitution of the primary antibody with PBS served as negative control.

TUNEL assay.

DNA fragmentation associated with apoptosis was detected in 4-μm prostate sections by TUNEL staining, using the ApopTag kit (S7110-kit, Oncor International) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Sections were counterstained with methyl green 0.1%.

Immunofluorescence.

4-μm paraffin sections were cut and mounted on xilane-coated slides and heated in a microwave 750 W for 20 min in acetate buffer. Tissue sections were incubated with anti-TIA1 (1:250; Immunotech) for 1 h at room temperature, then washed with PBS and incubated with a Texas red–conjugated anti–mouse IgG1 (1:1,000; Calbiochem).

After washing in PBS, slides were mounted in 2.5% 1,4-diazobicyclo[2.2.2]octane (DABCO, Fluka), 90% glycerol, 10% PBS and were examined using a confocal microscope (Bio-Rad Laboratories) with 60-magnification objective lenses (Nikon). In the case of double staining, after PBS washing sections were stained for DNA fragmentation, according to manufacturer's guidelines (Oncogene Research Products Fluorescein-FragEL DNA Fragmentation detection kit). The negative control was generated substituting PBS for anti-TIA-1 and TdT enzyme. Confocal microscope was performed with a PerkinElmer Ultra View. Images were analyzed using the Photoshop 7.0 program (Adobe Systems, Inc.)

Statistical analysis.

Results are expressed as mean ± SE. Statistical analysis was performed using Student's t test (Microsoft Office software; Microsoft Corporation). P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. M. Gardiman and Dr. G. Basso for critical discussion of our data and to Dr. A. Gugliucci and Dr. M. Mancini for the prostate culture protocols.

This work has been supported by grants from the Italian Ministry of Health (Ricerca finalizzata), Unindustria Treviso, U.S. Army (contract no. DAMD17-03-1-0032), and Italian Association for Cancer Research (AIRC) to A. Viola and from FIRB-MIUR (contract no. RBAU01935A), MIUR-CNR Progetto Strategico Oncologia, and the Italian Ministry of Health (Ricerca finalizzata) to V. Bronte.

The authors have no conflicting financial interests.

Abbreviations used: ARG, arginase; L-Arg, L-arginine; L-NMMA, _N_-monomethyl- L-arginine; NO, nitric oxide; NOHA, _N_-hydroxy-L-arginine; NOS, nitric oxide synthase; PCa, prostate carcinoma; TIA-1, T cell intracellular antigen 1; TIL, tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes; TRAMP, transgenic adenocarcinoma mouse prostate.

References

- 1.Finn, O.J. 2003. Cancer vaccines: between the idea and the reality. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3:630–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Der Bruggen, P., Y. Zhang, P. Chaux, V. Stroobant, C. Panichelli, E.S. Schultz, J. Chapiro, B.J. Van Den Eynde, F. Brasseur, and T. Boon. 2002. Tumor-specific shared antigenic peptides recognized by human T cells. Immunol. Rev. 188:51–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosenberg, S.A., J.C. Yang, and N.P. Restifo. 2004. Cancer immunotherapy: moving beyond current vaccines. Nat. Med. 10:909–915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coulie, P.G., and P. van der Bruggen. 2003. T-cell responses of vaccinated cancer patients. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 15:131–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parmiani, G., C. Castelli, P. Dalerba, R. Mortarini, L. Rivoltini, F.M. Marincola, and A. Anichini. 2002. Cancer immunotherapy with peptide-based vaccines: what have we achieved? Where are we going? J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 94:805–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marincola, F.M., E.M. Jaffee, D.J. Hicklin, and S. Ferrone. 2000. Escape of human solid tumors from T-cell recognition: molecular mechanisms and functional significance. Adv. Immunol. 74:181–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang, E., L.D. Miller, G.A. Ohnmacht, S. Mocellin, A. Perez-Diez, D. Petersen, Y. Zhao, R. Simon, J.I. Powell, E. Asaki, et al. 2002. Prospective molecular profiling of melanoma metastases suggests classifiers of immune responsiveness. Cancer Res. 62:3581–3586. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vakkila, J., and M.T. Lotze. 2004. Inflammation and necrosis promote tumour growth. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4:641–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mantovani, A., S. Sozzani, M. Locati, P. Allavena, and A. Sica. 2002. Macrophage polarization: tumor-associated macrophages as a paradigm for polarized M2 mononuclear phagocytes. Trends Immunol. 23:549–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whiteside, T.L. 1999. Signaling defects in T lymphocytes of patients with malignancy. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 48:346–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Munn, D.H., M.D. Sharma, D. Hou, B. Baban, J.R. Lee, S.J. Antonia, J.L. Messina, P. Chandler, P.A. Koni, and A.L. Mellor. 2004. Expression of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase by plasmacytoid dendritic cells in tumor-draining lymph nodes. J. Clin. Invest. 114:280–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uyttenhove, C., L. Pilotte, I. Theate, V. Stroobant, D. Colau, N. Parmentier, T. Boon, and B.J. Van den Eynde. 2003. Evidence for a tumoral immune resistance mechanism based on tryptophan degradation by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Nat. Med. 9:1269–1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu, G., and S.M. Morris Jr. 1998. Arginine metabolism: nitric oxide and beyond. Biochem. J. 336:1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bogdan, C. 2001. Nitric oxide and the immune response. Nat. Immunol. 2:907–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cederbaum, S.D., H. Yu, W.W. Grody, R.M. Kern, P. Yoo, and R.K. Iyer. 2004. Arginases I and II: do their functions overlap? Mol. Genet. Metab. 81:S38–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang, C.I., J.C. Liao, and L. Kuo. 2001. Macrophage arginase promotes tumor cell growth and suppresses nitric oxide-mediated tumor cytotoxicity. Cancer Res. 61:1100–1106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodriguez, P.C., D.G. Quiceno, J. Zabaleta, B. Ortiz, A.H. Zea, M.B. Piazuelo, A. Delgado, P. Correa, J. Brayer, E.M. Sotomayor, et al. 2004. Arginase I production in the tumor microenvironment by mature myeloid cells inhibits T-cell receptor expression and antigen-specific T-cell responses. Cancer Res. 64:5839–5849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu, W., L.Z. Liu, M. Loizidou, M. Ahmed, and I.G. Charles. 2002. The role of nitric oxide in cancer. Cell Res. 12:311–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bronte, V., P. Serafini, C. De Santo, I. Marigo, V. Tosello, A. Mazzoni, D.M. Segal, C. Staib, M. Lowel, G. Sutter, et al. 2003. IL-4-induced arginase 1 suppresses alloreactive T cells in tumor-bearing mice. J. Immunol. 170:270–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bronte, V., P. Serafini, A. Mazzoni, D.M. Segal, and P. Zanovello. 2003. L-arginine metabolism in myeloid cells controls T-lymphocyte functions. Trends Immunol. 24:302–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keskinege, A., S. Elgun, and E. Yilmaz. 2001. Possible implications of arginase and diamine oxidase in prostatic carcinoma. Cancer Detect. Prev. 25:76–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aaltoma, S.H., P.K. Lipponen, and V.M. Kosma. 2001. Inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression and its prognostic value in prostate cancer. Anticancer Res. 21:3101–3106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang, J., M. Torbenson, Q. Wang, J.Y. Ro, and M. Becich. 2003. Expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase in paired neoplastic and non-neoplastic primary prostate cell cultures and prostatectomy specimen. Urol. Oncol. 21:117–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Armstrong, A.C., D. Eaton, and J.C. Ewing. 2001. Science, medicine, and the future: cellular immunotherapy for cancer. BMJ. 323:1289–1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sallusto, F., D. Lenig, R. Forster, M. Lipp, and A. Lanzavecchia. 1999. Two subsets of memory T lymphocytes with distinct homing potentials and effector functions. Nature. 401:708–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Radoja, S., and A.B. Frey. 2000. Cancer-induced defective cytotoxic T lymphocyte effector function: another mechanism how antigenic tumors escape immune-mediated killing. Mol. Med. 6:465–479. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gorelik, L., and R.A. Flavell. 2001. Immune-mediated eradication of tumors through the blockade of transforming growth factor-beta signaling in T cells. Nat. Med. 7:1118–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Varani, J., M.K. Dame, K. Wojno, L. Schuger, and K.J. Johnson. 1999. Characteristics of nonmalignant and malignant human prostate in organ culture. Lab. Invest. 79:723–731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moulian, N., F. Truffault, Y.M. Gaudry-Talarmain, A. Serraf, and S. Berrih-Aknin. 2001. In vivo and in vitro apoptosis of human thymocytes are associated with nitrotyrosine formation. Blood. 97:3521–3530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brito, C., M. Naviliat, A.C. Tiscornia, F. Vuillier, G. Gualco, G. Dighiero, R. Radi, and A.M. Cayota. 1999. Peroxynitrite inhibits T lymphocyte activation and proliferation by promoting impairment of tyrosine phosphorylation and peroxynitrite-driven apoptotic death. J. Immunol. 162:3356–3366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koeck, T., X. Fu, S.L. Hazen, J.W. Crabb, D.J. Stuehr, and K.S. Aulak. 2004. Rapid and selective oxygen-regulated protein tyrosine denitration and nitration in mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 279:27257–27262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aulak, K.S., T. Koeck, J.W. Crabb, and D.J. Stuehr. 2004. Dynamics of protein nitration in cells and mitochondria. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 286:H30–H38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Radoja, S., M. Saio, D. Schaer, M. Koneru, S. Vukmanovic, and A.B. Frey. 2001. CD8(+) tumor-infiltrating T cells are deficient in perforin-mediated cytolytic activity due to defective microtubule-organizing center mobilization and lytic granule exocytosis. J. Immunol. 167:5042–5051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tian, Q., M. Streuli, H. Saito, S.F. Schlossman, and P. Anderson. 1991. A polyadenylate binding protein localized to the granules of cytolytic lymphocytes induces DNA fragmentation in target cells. Cell. 67:629–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meehan, S.M., R.T. McCluskey, M. Pascual, F.I. Preffer, P. Anderson, S.F. Schlossman, and R.B. Colvin. 1997. Cytotoxicity and apoptosis in human renal allografts: identification, distribution, and quantitation of cells with a cytotoxic granule protein GMP-17 (TIA-1) and cells with fragmented nuclear DNA. Lab. Invest. 76:639–649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaplan-Lefko, P.J., T.M. Chen, M.M. Ittmann, R.J. Barrios, G.E. Ayala, W.J. Huss, L.A. Maddison, B.A. Foster, and N.M. Greenberg. 2003. Pathobiology of autochthonous prostate cancer in a pre-clinical transgenic mouse model. Prostate. 55:219–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vesalainen, S., P. Lipponen, M. Talja, and K. Syrjanen. 1994. Histological grade, perineural infiltration, tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes and apoptosis as determinants of long-term prognosis in prostatic adenocarcinoma. Eur. J. Cancer. 30:1797–1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang, L., J.R. Conejo-Garcia, D. Katsaros, P.A. Gimotty, M. Massobrio, G. Regnani, A. Makrigiannakis, H. Gray, K. Schlienger, M.N. Liebman, et al. 2003. Intratumoral T cells, recurrence, and survival in epithelial ovarian cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 348:203–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dudley, M.E., and S.A. Rosenberg. 2003. Adoptive-cell-transfer therapy for the treatment of patients with cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 3:666–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Correale, P., L. Micheli, M.T. Vecchio, M. Sabatino, R. Petrioli, D. Pozzessere, S. Marsili, G. Giorgi, L. Lozzi, P. Neri, and G. Francini. 2001. A parathyroid-hormone-related-protein (PTH-rP)-specific cytotoxic T cell response induced by in vitro stimulation of tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes derived from prostate cancer metastases, with epitope peptide-loaded autologous dendritic cells and low-dose IL-2. Br. J. Cancer. 85:1722–1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Frost, P., R. Caliliw, A. Belldegrun, and B. Bonavida. 2003. Immunosensitization of resistant human tumor cells to cytotoxicity by tumor infiltrating lymphocytes. Int. J. Oncol. 22:431–437. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Whiteside, T.L. 1998. Immune cells in the tumor microenvironment. Mechanisms responsible for functional and signaling defects. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 451:167–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zippelius, A., P. Batard, V. Rubio-Godoy, G. Bioley, D. Lienard, F. Lejeune, D. Rimoldi, P. Guillaume, M. Meidenbauer, A. Mackensen, et al. 2004. Effector function of human tumor-specific CD8 T cells in melanoma lesions: a state of local functional tolerance. Cancer Res. 64:2865–2873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jenkins, D.C., I.G. Charles, L.L. Thomsen, D.W. Moss, L.S. Holmes, S.A. Baylis, P. Rhodes, K. Westmore, P.C. Emson, and S. Moncada. 1995. Roles of nitric oxide in tumor growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 92:4392–4396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu, W., L. Liu, G.C. Smith, and G. Charles. 2000. Nitric oxide upregulates expression of DNA-PKcs to protect cells from DNA-damaging anti-tumour agents. Nat. Cell Biol. 2:339–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xia, Y., and J.L. Zweier. 1997. Superoxide and peroxynitrite generation from inducible nitric oxide synthase in macrophages. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 94:6954–6958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xia, Y., L.J. Roman, B.S. Masters, and J.L. Zweier. 1998. Inducible nitric-oxide synthase generates superoxide from the reductase domain. J. Biol. Chem. 273:22635–22639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Groves, J.T. 1999. Peroxynitrite: reactive, invasive and enigmatic. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 3:226–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marla, S.S., J. Lee, and J.T. Groves. 1997. Peroxynitrite rapidly permeates phospholipid membranes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 94:14243–14248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aulak, K.S., M. Miyagi, L. Yan, K.A. West, D. Massillon, J.W. Crabb, and D.J. Stuehr. 2001. Proteomic method identifies proteins nitrated in vivo during inflammatory challenge. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:12056–12061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ischiropoulos, H. 2003. Biological selectivity and functional aspects of protein tyrosine nitration. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 305:776–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schopfer, F.J., P.R. Baker, and B.A. Freeman. 2003. NO-dependent protein nitration: a cell signaling event or an oxidative inflammatory response? Trends Biochem. Sci. 28:646–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kuo, W.N., R.N. Kanadia, V.P. Shanbhag, and R. Toro. 1999. Denitration of peroxynitrite-treated proteins by ‘protein nitratases’ from rat brain and heart. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 201:11–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Baniyash, M. 2004. TCR zeta-chain downregulation: curtailing an excessive inflammatory immune response. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 4:675–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kondratiev, S., E. Sabo, E. Yakirevich, O. Lavie, and M.B. Resnick. 2004. Intratumoral CD8+ T lymphocytes as a prognostic factor of survival in endometrial carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 10:4450–4456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yannelli, J.R., C. Hyatt, S. McConnell, K. Hines, L. Jacknin, L. Parker, M. Sanders, and S.A. Rosenberg. 1996. Growth of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes from human solid cancers: summary of a 5-year experience. Int. J. Cancer. 65:413–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Radoja, S., M. Saio, and A.B. Frey. 2001. CD8+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are primed for Fas-mediated activation-induced cell death but are not apoptotic in situ. J. Immunol. 166:6074–6083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lieberman, J. 2003. The ABCs of granule-mediated cytotoxicity: new weapons in the arsenal. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 3:361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Trambas, C.M., and G.M. Griffiths. 2003. Delivering the kiss of death. Nat. Immunol. 4:399–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Takayama, H., and M.V. Sitkovsky. 1987. Antigen receptor-regulated exocytosis in cytotoxic T lymphocytes. J. Exp. Med. 166:725–743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vallance, P., and J. Leiper. 2002. Blocking NO synthesis: how, where and why? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 1:939–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Colleluori, D.M., and D.E. Ash. 2001. Classical and slow-binding inhibitors of human type II arginase. Biochemistry. 40:9356–9362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Reisser, D., N. Onier-Cherix, and J.F. Jeannin. 2002. Arginase activity is inhibited by L-NAME, both in vitro and in vivo. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 17:267–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]