The Dawn of Human Matrilineal Diversity (original) (raw)

Abstract

The quest to explain demographic history during the early part of human evolution has been limited because of the scarce paleoanthropological record from the Middle Stone Age. To shed light on the structure of the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) phylogeny at the dawn of Homo sapiens, we constructed a matrilineal tree composed of 624 complete mtDNA genomes from sub-Saharan Hg L lineages. We paid particular attention to the Khoi and San (Khoisan) people of South Africa because they are considered to be a unique relic of hunter-gatherer lifestyle and to carry paternal and maternal lineages belonging to the deepest clades known among modern humans. Both the tree phylogeny and coalescence calculations suggest that Khoisan matrilineal ancestry diverged from the rest of the human mtDNA pool 90,000–150,000 years before present (ybp) and that at least five additional, currently extant maternal lineages existed during this period in parallel. Furthermore, we estimate that a minimum of 40 other evolutionarily successful lineages flourished in sub-Saharan Africa during the period of modern human dispersal out of Africa approximately 60,000–70,000 ybp. Only much later, at the beginning of the Late Stone Age, about 40,000 ybp, did introgression of additional lineages occur into the Khoisan mtDNA pool. This process was further accelerated during the recent Bantu expansions. Our results suggest that the early settlement of humans in Africa was already matrilineally structured and involved small, separately evolving isolated populations.

Introduction

Current genetic data support the hypothesis of a predominantly single origin for anatomically modern humans.1,2 The phylogeny of the maternally inherited mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) has played a pivotal role in this model by anchoring our most recent maternal common ancestor to sub-Saharan Africa and suggesting a single dispersal wave out of that continent which populated the rest of the world much later.3–5 However, despite its importance as the cradle of humanity and the main location of anatomically modern humans for most of their existence, the initial Homo sapiens population dynamics and dispersal routes remain poorly understood.6,7 The potential to use present-day genetic patterns to detect the existence, or lack thereof, of matrilineal genetic structure among early Homo sapiens populations in sub-Saharan Africa is therefore of particular interest.

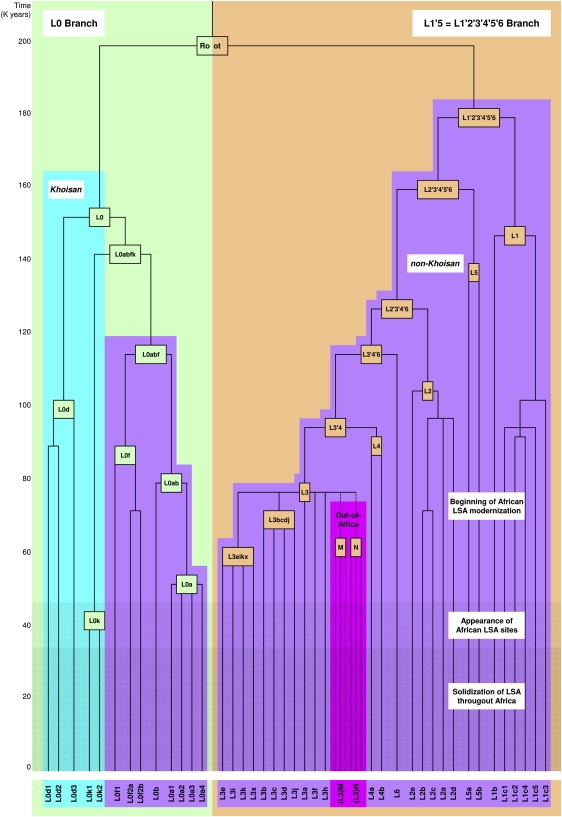

The human mtDNA phylogeny can be collapsed into two daughter branches, L0 and L1′2′3′4′5′6 (L1′5),5 located on opposite sides of its root (Figure 1).8,9 The L1′5 branch is far more widespread and has given rise to almost every mtDNA lineage found today, with two clades on this branch, (L3)M and (L3)N, forming the bulk of worldwide non-African genetic diversity and marking the out-of-Africa dispersal 50,000–65,000 years before present (ybp)4 (Figure 1). Current models, predating the recognition of L0 as sister to L1′5,9,10 suggest that the contemporary sub-Saharan mtDNA gene pool is the result of an early expansion of modern humans from their homeland, often suggested to be East Africa, to most of the African continent by exclusively L1 Hg clades, before being overwhelmed by a later expansion wave of L2 and L3 clades dated to 60,000–80,000 ybp.11,12 A more recent geographically restricted enrichment of the African maternal gene pool was shown to have occurred during the early Upper Paleolithic, when populations carrying mtDNA clades M1 and U6 arrived to north and northeast Africa from Eurasia, hardly penetrating the sub-Saharan portion of the continent, except Ethiopia.13,14 Therefore, the current sub-Saharan mtDNA gene pool is overwhelmingly a rich mix of L0 and L1′5 clades, found at varying frequencies throughout the continent.15

Figure 1.

Simplified Human mtDNA Phylogeny

The L0 and L1′5 branches are highlighted in light green and tan, respectively. The branches are made up of haplogroups L0–L6 which, in their turn, are divided into clades. Khoisan and non-Khoisan clades are shown in blue and purple, respectively. Clades involved in the African exodus are shown in pink. A time scale is given on the left. Approximate time periods for the beginning of African LSA modernization, appearance of African LSA sites, and solidization of LSA throughout Africa are shown by increasing colors densities. For a more detailed phylogeny, see Figure S1.

This entangled pattern of mtDNA variation gives an initial impression of lack of internal maternal genetic structure within the continent. Alternatively, it might indicate the elimination of such an early structure because of massive demographic shifts within the continent, the most dominant of which was certainly the recent Bantu expansions and spread of agriculturist style of living.15 However, some L(xM,N) clades do show significant phylogeographic structure in Africa, such as the localization of L1c1a to central Africa16 or the localization of L0d and L0k (previously L1d and L1k) to the Khoisan people,17–20 in which they account for over 60% of the contemporary mtDNA gene pool. Early studies based on mtDNA control region variation have suggested that Khoisan divergence dates to an early stage in the history of modern humans,18 whereas their anthropological and linguistic features show closer affinities to each other than to those of other populations in Africa.21,22 Their distinctiveness is also supported by phylogenetic studies of the male-specific Y chromosome that indicate that the most basal branch of the Y phylogeny is now common among the Khoisan but is rare or absent in other populations.18

To better understand the reason for the high prevalence of two basal mtDNA lineages L0d and L0k within Khoisan, and the possible implications that this pattern might have on our understanding of early maternal genetic structure within Homo sapiens populations, we studied, at the level of complete mtDNA sequences, the variation of 624 Hg L(xM,N) mtDNA genomes. Our findings enable the identification of different phylogenetic origins for L0d and L0k lineages versus all other contemporary mtDNA lineages found within the Khoisan and support a demographic model with extensive maternal genetic structure during the early evolutionary history of Homo sapiens. This maternal structure is likely the result of ancient population splits and movements and is not consistent with a homogenous distribution of modern humans throughout sub-Saharan Africa.

Material and Methods

Sampling

Table S1 available online details the information for each of the 624 samples included in this study. We evaluated all 315 Hg L(xM,N) complete mtDNA sequences reported in the literature.5,8–10,16,23–25 Next, we identified all Hg L(xM,N) samples in all population sample collections available in Haifa (D.M.B.), Family Tree DNA (D.M.B.), Johannesburg (H.S. and H.M.), National Geographic Society (R.S.W. and J.B.S.), Paris (L.Q.M.), Porto (L.P.), Rome (R.S.), and Tartu (E.M. and R.V.) and chose 309 for complete mtDNA sequencing. Samples were chosen to include the widest possible range of Hg L(xM,N) internal variation on the basis of the previously available sequence analysis of the mtDNA control region and are, therefore, biased toward rare variants. In addition, we attempted to focus on branches (e.g., L0d, L0k), populations (e.g., Khoisan), and geographic regions (e.g., Chad) for which the current data were scant. Last, we preferred to sequence variants that the current literature suggested to be rare or anecdotal in any given geographic region (e.g., L0k in the Near East). All samples reported herein were derived from blood, buccal swab, or blood cell samples that were collected with informed consent according to procedures approved by the Institutional Human Subjects Review Committees in their respective locations.

Complete mtDNA Sequencing

DNA was amplified with 18 primers to yield nine overlapping fragments as previously reported.26 After purification, the nine fragments were sequenced by means of 56 internal primers to obtain the complete mtDNA genome. Sequencing was performed on a 3730xl DNA Analyzer (Applied Biosystems), and the resulting sequences were analyzed with the Sequencher software (Gene Codes Corporation). Mutations were scored relative to the revised Cambridge Reference Sequence (rCRS).27 The 309 Hg L(xM,N) complete mtDNA sequences reported herein have been submitted to GenBank (accession numbers EU092658–EU092966). Sample quality control was assured as follows:

- After the primary polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of the nine fragments, DNA handling and distribution to the 56 sequencing reactions was aided by the Beckman Coulter Biomek FX liquid handler to minimize the chance for human pipetting errors.

- All 56 sequencing reactions of each sample were attempted simultaneously in the same sequencing run and included resequencing of the control region to assure that the correct sample was chosen. Therefore, most observed polymorphisms were determined by at least two sequences. However, in a minority of the cases only one sequence is available because of various technical reasons, usually related to the amount and quality of the DNA available.

- Any fragment that failed the first sequencing attempt or any ambiguous base call was tested by additional and independent PCR and sequencing reactions. In these cases, the first hypervariable segment was again resequenced to assure that the correct sample was chosen.

- All sequences were aligned by the software Sequencher (Gene Codes Corporation), and all positions with a Phred score less than 30 were directly inspected by an operator.28,29 All positions that differed from the rCRS were recorded electronically to minimize typographic errors.

- Any sample that showed a deviation from the expected evolutionary hierarchy as suggested by the established Hg L(xM,N) phylogeny was highlighted and resequenced when a lab error was suspected.

- Any comments and remarks raised by external investigators after release of the data will be addressed by reobservation of the original sequences for accuracy. After that, any unresolved result will be further examined by resequencing and, if necessary, immediately corrected by publication of an erratum.

Nomenclature

The term African Hg L(xM,N) is used to describe all mtDNA Haplogroups but (L3)M and (L3)N. We reserve the term branch to describe the two evolving sides of the root and have labeled them L0 and L1′2′3′4′5′6 (L1′5).5 The two major branches each composed of one to several haplogroups.30 Note that the L0 branch is made of the L0 Hg alone, whereas the L1′5 branch includes haplogroups L1–L6. Haplogroups are composed of clades (e.g., L0d and L0k), which in their turn are composed of lineages, which represent an evolving set of closely related haplotypes. The term haplotype describes the entire combination of substitutions retrieved from the complete sequence in any given sample and therefore indicates the tips of the phylogeny, whether a singleton or not. Numbers 1–16569 refer to the position of the substitution in the rCRS.27 We followed the consensus nomenclature scheme31 when possible. In many cases, we labeled previously unreported deep branches (e.g., L1c1c), understanding that these designations are meant to facilitate reading and future literature comparison and are prospective candidates of clades to be fully defined in the future, provided common ancestral substitution motifs could be identified in complete mtDNA sequences of other samples. Nomenclature within Hg L(xM,N) has been the subject of some ambiguity because of the relabeling of some of the clades. The clades L0d, L0f, L0k, and L5 were previously labeled L1d, L1f, L1k, and L1e, respectively. We followed the designation in5,8,15,32 for the definitions of the major branches with a single exception. We have eliminated the label L7 coined in5 and revert back to the original label L4a as suggested in13 because of the following: (1) A large number of samples (17) suggest position 16362 to be at the root of both clades, (2) both clades share similar distribution in East Africa and in southern West Eurasia, and (3) coalescence ages and the observed subclade-type architecture appear to be similar. We have not used the label L1c5 suggested by33 because our complete mtDNA-based analysis indicates it to be L1c1a1, as suggested by.15 To avoid confusion, we have skipped this label and moved from L1c4 to L1c6. We added labeling for previously unlabeled bifurcations if they became relevant for our discussion.

The term Khoisan is used in reference to two major ethnic groups of Southern Africa, the Khoi and San, though several other names exist for either one or both of these groups, such as the Khoi, Khoe, Khoi-San, and Khoe-San.

African Hg L Phylogeny

We generated a maximum-parsimony tree of 624 complete mtDNA sequences belonging to Hg L(xM,N) (Figure S1). The tree was rooted according to8 and includes 309 samples reported herein and 315 previously reported samples: 21 sequences from,23 six from,10 five from,34 ten from,9 93 from,24 126 from,8 23 from,5 four from,25 and 27 from.16 The genotyping information from5,34 included herein corrects several inaccuracies that were identified during the establishment of the phylogeny. Sequence data from35 were not incorporated into our summary tree because we counted at least 25 missing root-defining substitutions in some of the reported complete mtDNA sequences. Until the reason(s) for such substantial differences can be identified, we preferred to omit this published database. Mutations are shown on the branches. Transitions are labeled in capital letters (e.g., 10420G). Transversions are labeled in lowercase letters (e.g., 2836a). Sequencing alignment always prefers 3′ gap placement for indels. Deletions are indicated by a “d” after the deleted nucleotide position (e.g., 15944d). Insertions are indicated by a dot followed by the number and type of inserted nucleotide(s) (e.g., 5899.1C). In cases where an insertion was expected according to the phylogeny but a reversion of the insertion was observed, we denoted it as in the following example: sample L263, 5899.1Cd. Underlined nucleotide positions occur at least twice in the tree. An exclamation mark (!) at the end of a labeled position denotes a reversion to the ancestral state in the relative pathway to the rCRS. Sample names are denoted by the letter L followed by a serial number. The contemporary country in which the sample was collected (if known) is marked below the serial number, and the background is colored to grossly divide the samples into the Near East, Southwest Asia, the Mediterranean, Europe, and South, North, West, East, and sub-Saharan Africa as denoted in the color index at the upper-left corner of the figure. The ethnicity (if known) of the individual who donated the sample is further marked below. When the country from which the sample was collected is unknown, the gross geographic region is inferred from the ethnicity information. The information included herein from8 includes information from the coding region alone (435–16023) and is denoted by the letter p at the end of the serial number.

The tree was first drawn by hand, and its branches were validated by networks constructed with the program Network 4.2.0.1. We have applied the reduced median algorithm (r = 2), followed by the median-joining algorithm (epsilon = 2) as described at the Fluxus Engineering website. The hypervariable indels at positions 309, 315, and 16189 were excluded from the phylogeny. The information of the reported samples is presented in Table S1. Some caveats and possible genotyping or reading errors that might affect the accuracy of the phylogeny are detailed herein:

- Many lineages throughout the phylogeny assemble samples from8 that do not contain the control-region information and samples for which the control-region information is available. In these lineages, we assume that the former contain the control-region haplotypes of the latter. For example, sub-Hg L0d1b contains five samples. However, the control-region information available for only two of them is placed at the root of this subhaplogroup.

- The phylogeny assembles control and coding-region polymorphisms. Our efforts to follow parsimony principles to label some of the most mutable control-region positions should best be treated as heuristic and not as such representing real evolutionary meaning. For example, position 143 under sub-Hg L2a1 is likely not following the real coalescence flow for this position within this subhaplogroup.

- Position 9755 was suggested by8 to be at the root of L1′2′3′4′5′6 when compared with inserts of mtDNA retrieved from human genomic sequence and the consensus sequence of three chimpanzee mtDNA genomes. However, the more parsimonious solution inferred from our extended database for the topological placement of the 9755 substitution suggests its occurrence at the root of the chimpanzee tree and at the root human L0d1′2 and L0ab clades. One less transition event is then needed to explain the current occurrence of position 9755 among humans and chimpanzees. The final location of this position may be further revised as additional knowledge accumulates.

- We acknowledge that we have no way to accurately count the number of C insertions in positions known to contain polymorphisms of this kind. Thus, the number of C insertions in positions 573, 5899, and 16189 suggested for some of the samples cannot be held as a firm number. Therefore, all samples containing a poly C stretch at position 573 and 5899 are labeled as having one C insertion (e.g., 5899.1C).

- The phylogeny contains reticulations that cannot be resolved without homoplasy or back mutation.

- L366—The sample information is missing in the region 15380–540.

- L026—Six coding-region and one control-region back mutations of higher hierarchic branching positions are suggested.10

- L071—Two coding-region back mutations of higher hierarchic branching positions are suggested.24

- L002—Three coding-region back mutations of higher hierarchic branching positions are suggested.23

- L025—Six coding-region back mutations of higher hierarchic branching positions are suggested.10

- L248—Two coding-region back mutations of higher hierarchic branching positions are suggested.8

- L029 and L159—The insertions denoted as 8288.6C and 8276.6C might represent the same polymorphism.8,34

- L039—Three coding-region back mutations of higher hierarchic branching positions are suggested.9

- L080—Two coding-region back mutations of higher hierarchic branching positions are suggested.24

- L351—Two coding-region and three control-region back mutations of higher hierarchic branching positions are suggested in this study. A sequencing error was not found. Note that the sample represents a deep split, L1c1, that is first reported herein.

- Many samples reported by24 contain the polymorphism 317.1C. We operate under the understanding that this is the polymorphism usually labeled 315.1C, which is restricted from the analysis herein.

- L071, L083, L133, and L135—These four samples reported by24 contain the polymorphism 317.1A. We operate under the understanding that this is the polymorphism usually labeled 316A.

- L018—The sample was originally reported to harbor polymorphisms 16187C! and 16188.1C.23 According to the phylogeny, polymorphism 16187T is expected.

- L004—The sample was originally reported to harbor polymorphisms 16192.1T.23 According to the phylogeny, polymorphism 16192T is expected and is shown as such herein.

- L125—The sample was originally reported to harbor polymorphisms 960C and 965.1C.24 According to the phylogeny, polymorphism 961C is expected and is shown as such herein.

- L083, L133, and L134—The samples were originally reported to harbor the polymorphism 2157.1A. They are shown herein as 2156.1A.

- L067—The sample was originally reported to harbor deletions and insertions in the region of the 9 bp repeat in position 828024 that are not concordant with a complete 9 bp deletion or insertion. We rejected the original report because L067 sister lineage demonstrates a 9 bp deletion.

- L097 and L126—The samples show alternating reports for transversions and transitions for positions 16114 and 16215,24 which were assumed to represent a typographic mistake.

- We deviated from the parsimony principles for position 64T at the root of L0a2a and L0a2b.

- We deviated from the parsimony principles for position 95c at the root of L0a2c and L0a2d.

- We deviated from the parsimony principles for position 198T at the root of L1c2 and L1c4.

Age Estimates

For age estimation of ancestral nodes in our phylogenetic tree, we applied PAML36 to the coding-region polymorphisms of our samples, excluding indels, and by using the HKY85 substitution model. Each tip node of the phylogenetic tree was counted as one event if shared by a few samples. We eliminated from the coalescence analysis samples L025, L026, and L039, in which we observed three or more coding-region back mutations at haplogroup-defining positions. We used the rate of 5138 years per coding-region single-nucleotide polymorphism9 to translate the age estimates in mutations into ages in years. It is worth noting that age estimates in years should be cautiously interpreted because the actual mutation rate in years per mutation remains an open debate in the literature.8,37 The maximum-likelihood estimate of the transition to transversion rate on the basis of our data was 19.91, with a standard error of 1.02. It is important to consider the meaning of the age estimates given herein. Each estimate is a time to the most recent common ancestor of a set of mtDNA molecules. Thus the age of the L0d clade, defined by the available sequences, is 101,589 ± 10,318 ybp, but it started to diverge from its sister clade, L0abfk, 143,654 ± 11,111 ybp. Mutations defining the L0d clade could have occurred at any time between these two dates.

Hypothesis Testing of the Time of Isolation of the Khoisan

Our goal here was to evaluate whether it is likely that the phylogenetic restriction of Khoisan to lineages in L0d and L0k could result from an isolation event starting from a single, homogeneous Homo sapiens population at different points in time. Given a time X (say, 100,000 ybp), we consider three elements:

- •

Y—The number of lineages extant at time X with surviving offspring (at 100,000 ybp we get Y = 14—see Figure S1) - •

Z—The number of Khoisan ancestral lineages within Y (at 100,000 ybp we get Z = 3, the lineages L0d1, L0d2, L0k) - •

L—A measure of the localization of Khoisan ancestors in the coalescent phylogenetic tree of the Y lineages. We measure localization by the number of links in the tree that have to be cut to isolate the Khoisan lineages from all other lineages. At 100,000 ybp we get L = 2 (because cutting the link to L0abf and the link between the root and L0 isolates the three Khoisan lineages from the rest of the tree).

We then perform a permutation test to assess whether a random selection of Z lineages out of Y (given the phylogenetic tree of the Y lineages) is likely to have created an isolation measure smaller than or equal to L. In other words, we count how many groups of Z lineages can be isolated from the rest of the tree by cutting L links or less and then divide this number by the total number of groups of Z lineages (which is choosing Z out of Y). For the example of 100,000 ybp, the seven triplets that can be isolated from the rest of the tree by cutting at most two links are the following:

- •

L0ab + L0f + L0k (by cutting of a single link leading to the L0abfk ancestor) - •

L0k + L0d1 + L0d2 (the actual Khoisan lineages) - •

L1b + L1c3 + L1c124 (by cutting of a single link leading to the L1 ancestor) - •

L2abcd + L2e + L34 (by cutting of the link to L6 and the link leading to the L2-6 ancestor) - •

L2abcd + L2e + L6 (by cutting of the link to L34 and the link leading to the L2-6 ancestor) - •

L2abcd + L34 + L6 (by cutting of the link to L2e and the link leading to the L2-6 ancestor) - •

L2e + L34 + L6 (by cutting the link to L2abcd and the link leading to the L2-6 ancestor)

This gives a permutation test p value of 7/(14 choose 3) = 0.019 to the event that an isolation of three lineages by drift would lead to this level of phylogenetic localization. We applied this test to the phylogenetic tree at various time points (Table 1). As can be seen, the isolation-and-drift hypothesis can be rejected for times later than 100,000 ybp, with p values of 0.019 and 0.0016 for 100,000 and 90,000 ybp, respectively. For later dates, the p values decrease dramatically further.

Table 1.

Estimated Odds for the Occurrence of L0d and L0k Clades in Khoisan by Drift

| X (Time ybp) | Y (Number of Lineages) | Z (Number of Khoisan Lineages) | L (Localization Measure)a | p Value | p Value Corrected by FDRa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 144,000 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 0.24 | 0.24 |

| 120,000 | 9 | 2 | 2 | 0.17 | 0.24 |

| 100,000 | 14 | 3 | 2 | 0.019 | 0.057 |

| 90,000 | 22 | 4 | 2 | 0.0016 | 0.0065 |

| 80,000 | 24 | 4 | 2 | 0.0012 | 0.0061 |

In analyzing the results in Table 1, we may want to take into account the issues of multiple comparisons and false discovery rate (FDR).38 First, we observe that our testing procedure can be considered sequential, because the hypothesis we are testing is that the isolation occurred at or after time X. So, as soon as we reject the hypothesis for time X, we are implicitly rejecting the hypothesis for all later times. Thus, we can reject the hypothesis that the isolation happened at 144,000 ybp or later at significance level 0.24 (in which case our second model of an early split must be correct). For the 100,000 ybp test, the p value of 0.019 implies that we would reject the hypothesis of isolation at or after this date at a significance level of 0.019 × 3 = 0.057 or higher (3 is the FDR correction factor, in this case identical to a Bonferroni correction), after a multiple-comparison correction. For the 90,000 ybp test, the result is significant at level 0.0016 × 4 = 0.0065 or higher. It should be noted that, because the hypotheses we are testing are positively correlated (relating to the evolution of one tree over time), the FDR correction we perform here is overly conservative.39

Results

Allocating the Khoisan mtDNA Lineages within the African Hg L Phylogeny

The contemporary composition of the Khoisan mtDNA gene pool shows that over 60% of Khoisan carry either L0d or L0k lineages, whereas the remaining 40% are a mixture of various non-L0d or L0k lineages found in sub-Saharan Africa.17–20 To survey contemporary Khoisan mtDNA diversity, we generated a maximum-parsimony tree composed of 309 previously unreported and 315 previously reported5,8–10,16,23,25,34,40 complete Hg L(xM,N) mtDNA genomes from populations located throughout the Hg L(xM,N) geographic range of distribution (Table S1) and including 38 Khoisan samples. In this instance, the detailed Hg L(xM,N) phylogeny served as a magnifying background for the accurate positioning of the 38 Khoisan mtDNA genomes. This in turn allowed us to focus on branches in which Khoisan and non-Khoisan samples were found in close phylogenetic proximity, in an attempt to understand the temporal origin and timing of their introduction into the Khoisan. To capture as many different lineages as possible within the Khoisan, sample selection was enriched for rare variants, both within and outside of the L0d and L0k clades. Given the reported structure of the Khoisan mtDNA gene pool17,18 it is likely that the 38 Khoisan complete mtDNA sequences cover most variation within Khoisan L0d and L0k clades but may incompletely represent Khoisan non-L0d and L0k clades.

Revealing the Remote and Recent Maternal Ancestors of Contemporary Khoisan

The observation of L0d and L0k lineages in non-Khoisan populations,13 as well as of various non-L0d or L0k lineages among Khoisan,15 implies that the correct interpretation of the Khoisan mtDNA gene pool depends on our ability to understand the phylogenetic origin, rather than just the frequencies,17,18 of the various lineages. L0d is represented by 30 samples, of which 20 are from the Khoisan, and L0k comprises seven samples, of which six are from the Khoisan and the other is from Yemen. Each of the ten non-Khoisan L0d samples was compared with its topologically closest Khoisan neighbor, and this yielded an average coalescence time estimate of 13,000 ybp, with the greatest time depth at 33,000 ± 9,000 ybp (Table 2, Figure S1). The single L0k Yemenite sample coalesced with the Khoisan L0k samples at 40,000 ± 9,000 ybp (Table 2, Figure S1). Similarly, all Khoisan sequences not belonging to L0d or L0k haplotypes were also assessed to determine coalescence age estimates with their nearest non-Khoisan topological neighbors. The L0abf clade and the L1′5 branch included one and 11 Khoisan samples, respectively, whose average coalescence with their respective closest topological non-Khoisan neighbors was 7,000 ybp, with the largest estimated age at 39,000 ± 6,000 ybp (Table 2). The observation of higher frequency and greater internal variation of L0d and L0k lineages within the Khoisan (Table 2, Figure S1) clearly points to this group as the initial source of these two haplogroups in non-Khoisan, whereas the higher frequency and internal variation of L1′5 lineages in non-Khoisan suggests that their presence in the Khoisan is the result of recent gene flow from elsewhere.

Table 2.

Coalescence Estimates for Nearest Neighboring Khoisan and Non-Khoisan Types

| Haplogroup | Khoisan (Sample ID) | Non-Khoisan (Sample ID) | Coalescence ± Standard Error (ybp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| L0d1aa | L490 | L219, L524 | 18,254 ± 6,349 |

| L0d1ba | L500 | L220 | 16,667 ± 6,349 |

| L0d1c1a | L226, L488 | L521 | 0 ± 2,600 |

| L226, L488 | L520 | 2,381 ± 2,381 | |

| L0d2aa | L492, L035, L505, L498 | L334 | 8,730 ± 3,175 |

| L035, L505, L498 | L215 | 6,349 ± 2,381 | |

| L0d2ca | L503, L504 | L209, L342 | 20,635 ± 5,556 |

| L0d3a | L501 | L583 | 33,334 ± 8,730 |

| L0ka | L496, L018, L019, L506, L513, L15 | L441 | 39,683 ± 8,730 |

| L0a1b1 | L519 | L125 | 1,587 ± 794 |

| L1b1a | L512 | L129 | 0 ± 2,600 |

| L1b1a4 | L038 | L128, L349 | 5,556 ± 2,381 |

| L1c1a1a1b | L042 | L268, L272, L276 | 3,968 ± 2,381 |

| L1c1d | L494 | L277 | 7,143 ± 4,762 |

| L2b1 | L514 | L033 | 0 ± 2,600 |

| L2a2b | L041 | L238, L243 | 3,175 ± 2,381 |

| L2a1f | L227 | L324, L571, L214, L581, L339 | 7,937 ± 3,968 |

| L4b2a2 | L211, L497 | L428, L616, L386, L603 | 38,890 ± 5,556 |

| L3e1b | L507 | L536 | 0 ± 2,600 |

| L3f1b1 | L518 | L116, L118, L330 | 9,524 ± 2,381 |

Taken together, the complete mtDNA coalescence analysis reveals two independent sources for the contemporary Khoisan mtDNA gene pool. The lesser of these appears to be the result of recent introgression from a variety of haplogroups existing elsewhere in Africa. Even the oldest age estimates for these exogenous lineages postdate the onset of the Late Stone Age (LSA) (Table 2) and the apparent increase in modern human migration associated with that period,3,15 and the majority of these lineages are concordant with the very recent (3000–5000 ybp) expansion of Bantu-speaking peoples from western Africa.41 When these apparently recent introgression events are eliminated, this finding suggests that apart from extinct clades, the mtDNA gene pool of the Middle Stone Age (MSA) Khoisan ancestors was probably limited to the clades L0d and L0k.

Dating the Khoisan Division and Isolation

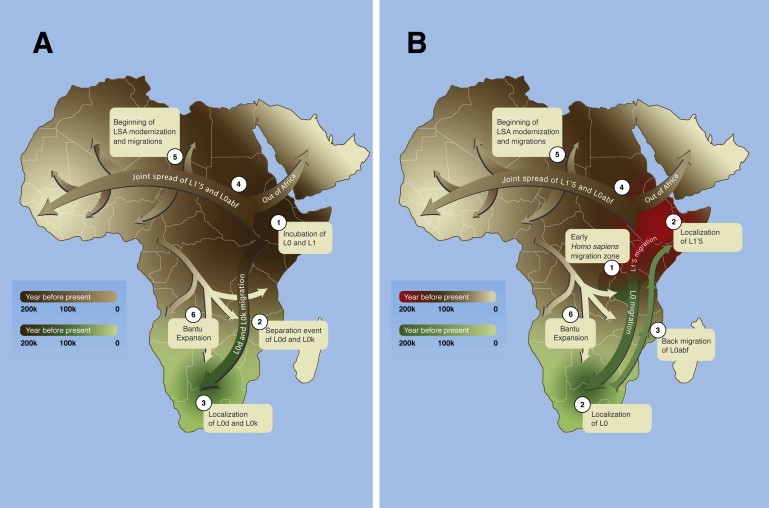

The concomitant occurrence of the two adjacent basal mtDNA clades, L0d and L0k, within the Khoisan demands an explanation. In the following, we compare two alternative hypotheses (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Maternal Gene Flow within Africa

The gradual maternal movements suggested by the first (A) and second (B) hypotheses are denoted by the ascending numerical labels. A gradient colorization system is used to illustrate the timing of the events. The temporal direction and timing of the arrows and expansion waves are general and should not be treated as firm migratory paths.

(A) An initial prolonged colonization (brown) by anatomically modern humans (1) is followed by a dispersal wave (green) of a fracture of the population (2) and the localization of L0d and L0k to southern Africa (3).

(B) An early Homo sapiens division in a hypothetical migration zone (1) resulted in two separately evolving populations (2) and the localization of L0 (green) in southern Africa and L1′5 (red) in eastern Africa. A subsequent dispersal event of the L0abf subset from the southern population and its mergence with the eastern population (brown) is suggested (3), resulting in the former population composed only of L0d and L0k and the latter composed of L1′5 and L0abf.

Later dispersal waves from the eastern African population parallels the beginning of African LSA approximately 70,000 ybp (4). Rapid migrations during the LSA (5) brought descendants of the eastern African population into repeated contact with the southern population, peaking during the Bantu expansion (6).

The first hypothesis has been previously explained as the existence of a single ancestral MSA Homo sapiens population probably existing in eastern or southern Africa.6,11,13,42 According to this hypothesis, both L0 and L1′5 clades would have coevolved within it, and the localization of L0d and L0k to the southern part of Africa is then considered the result of a population split followed by drift. This could result from a migration followed by isolation (Figure 2A) and would thus reveal the footprint of an early spread of the ancestral population across sub-Saharan Africa.12 In the context of this hypothesis, one must consider the likelihood that from a population rich in a joint variety of L0 and L1′5 lineages, only the two basal and topologically adjacent L0 clades, L0d and L0k, would be enriched by drift within the Khoisan while becoming extinct in all non-Khoisan. The lower time limit of such a separation can be inferred from the likelihood that it occurred based on the composition of L0 and L1′5 clades at different time frames within and outside Khoisan because we evaluated it by our hypothesis testing of the time of isolation of the Khoisan. On the basis of our hypothesis testing of the time of isolation of the Khoisan, we conclude that it is unlikely that the genetic composition of modern Khoisan stemmed from a putative homogeneous L0 and L1′5 source population later than 90,000 ybp (p = 0.0065) (Table 1). An upper time limit for the underlying drifting event can be inferred from the first time L0d and L0k existed together, corresponding to the L0abfk split around 140,000 ybp (Figure S1). Naturally, this hypothesis cannot be extended to time periods earlier than the L0abfk split and the emergence of the L0k clade (Figure 1).

Here, we propose an alternative hypothesis, which suggests that the deepest L0-L1′5 split observed in the human mtDNA tree might represent both a phylogenetic and an ancient Homo sapiens population split into two small populations. This division, occurring in an unknown early Homo sapiens migratory zone, is dated by our coalescence estimates to 140,000–210,000 ybp (Figure S1) and was possibly generated by drift due to the small population sizes of that period.6,11,13,42 This hypothesis therefore suggests the localization of these early L0 and L1′5 mtDNA branches to populations located in southern and eastern Africa, respectively (Figure 2B). The presence of L0d and L0k within the contemporary Khoisan may therefore result from their independent evolution within the early southern L0 population rather than occurring as a matter of chance. The observation of L0abf lineages found throughout the L1′5 range would then be explained by a dispersal event circa 144,000 ybp (L0abfk split, Figure 1) where the successful integration of a subset of L0 lineages into the L1′5 population was likely due to favorable environmental conditions in eastern Africa compared with those in southern Africa.

Discussion

Khoisan: The First Division

The phylogenetic analysis of complete mtDNA sequences found among contemporary Khoisan suggests that their division from other modern humans occurred not later than 90,000 ybp and therefore reveals strong evidence for the existence of maternal structure early in the history of Homo sapiens. This hypothesis closely parallels the pattern seen earlier in the fossil hominine record, where the “bushy” tree43 shows clear evidence of population divergence during the evolution of our ancestors over millions of years.44 With this information, we further attempted to track the possible mechanisms that shaped the foundation and evolution of Khoisan ancestors. Although it is impossible to validate empirically the two suggested hypothesis (or even more complex intermediate scenarios) on the basis of the genetic data alone, three important points deserve mention.

First, our results highlight the L0abfk split about 133,000–155,000 ybp (Figure 1) as marking a key point in Homo sapiens matrilineal population structuring. Though the archeological record from this period is too poor to reliably identify reasons for the split(s), recent studies show that the sporadic settlements of Homo sapiens in northwest Africa, the Near East, Chad, and southern Africa45–47 may have been caused by stressful climatic fluctuations known to have occurred throughout the MSA.47,48 Archeological evidence reveals the early existence of Homo sapiens in southern Africa (70,000 ybp),46 and studies of the mtDNA in contemporary populations demonstrate convincingly that very deep (50,000–60,000 ybp) autochthonous mtDNA lineages can survive locally both in isolated habitats49 and open surroundings.4 Although it is tempting to link these early southern African settlements to ancestors of the Khoisan, our data cannot prove it, nor can they suggest the cradle of Homo sapiens to be southern or eastern Africa.

Second, it is evident that since the L0abfk split, the expansion dynamics of the L0d and L0k clades and that of the L0abf and L1′5 clades have proceeded in the most uneven ways, with one localizing to southern Africa and giving rise to the matrilineal ancestry of the present-day Khoisan and the other spreading to all corners of the world and giving rise to all present-day non-Khoisan populations, including non-Africans.

Third, it seems that these southern and eastern populations remained isolated from each other, at least maternally, for an extremely long period of between 50,000 and 100,000 years until the development of LSA technologies47 which, coupled with more favorable environmental conditions, may have allowed behaviorally modern Homo sapiens to expand its range.6 This apparent sign of maternal isolation and structure in the early settlement dynamics of Africa implies the formation of small, independent human communities rather than a uniform early spread of anatomically modern humans as previously suggested.11,12

Early Maternal Genetic Structure among Modern Humans

The proposed matrilineal sequestration of African MSA mtDNA into isolated populations does not seem to be restricted to Khoisan. A recent study showed that ancestors of contemporary Pygmies diverged from an ancestral Central African population no more than 70,000 ybp and that isolation was breached throughout the LSA.16 Moreover, this matrilineal sequestration pattern also offers a simple explanation to the surprising finding that of the more than 40 mtDNA lineages in Africa at the time modern humans left Africa3 (Figure S1), only two of the variants, (L3)M and (L3)N,4 gave rise to the entire wealth of mtDNA diversity outside of Africa.5,8 Different approaches were taken in the attempt to estimate the sub-Saharan Homo sapiens population size in different time frames.7 The understanding of the minimum number of existing maternal lineages in different time periods, as far as can be estimated from their survival to the present day, might benefit our understanding of the magnitude of Homo sapiens expansion in these periods and shed light on the frequency of the loss of mtDNA lineages in long time periods.

In summary, the study of extant genetic variation in African populations with complete mtDNA sequences provides an insight into past Homo sapiens demographics, suggesting that small groups of early humans remained in geographic and genetic isolation until migrations during the LSA. Studies of additional genomic regions, particularly of unlinked autosomal regions with their greater effective population size, may reveal additional details about these early demographic events from a genome-wide perspective.

Supplemental Data

One figure and one table are available at http://www.ajhg.org/.

Supplemental Data

Figure S1. African Hg L Phylogeny

Table S1. Source, Demography, and Genotyping Parameters of the 624 Complete mtDNA Sequences

Web Resources

The URLs for data presented herein are as follows:

- GenBank, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Genbank/

- Fluxus Engineering, http://www.fluxus-engineering.com

Accession Numbers

The 309 Hg L(xM,N) complete mtDNA sequences reported herein have been submitted to GenBank under accession numbers EU092658–EU092966.

Acknowledgments

We thank all individuals that have voluntarily donated their DNA sample to the study. We also thank Ryan Sprissler and Heather M. Issar from the Arizona Research Labs, University of Arizona, and Concetta Bormans and Michal Bronstein from the Genomics Research Center, Family Tree DNA, for excellent laboratory services. This study was supported by National Geographic Society, IBM, the Waitt Family Foundation, the Seaver Family Foundation, Family Tree DNA, and Arizona Research Labs. R.V. is grateful to Swedish Collegium of Advanced Studies for fellowship during the final preparation of the manuscript. S.R. is partially supported by European Union grant MIRG-CT-2007-208019. C.T.S. is supported by The Wellcome Trust. Instituto de Patologia e Imunologia Molecular da Universidade do Porto (IPATIMUP) (L.P.) is supported by Programa Operacional Ciência, Tecnologia e Inovação (POCTI) and Quadro Comunitário de Apoio III.

The Genographic Consortium includes the following: Theodore G. Schurr, Department of Anthropology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104-6398, USA; Fabricio R. Santos, Departamento de Biologia Geral, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais 31270-010, Brazil; Lluis Quintana-Murci, Unit of Human Evolutionary Genetics, CNRS URA3012, Institut Pasteur, Institut Pasteur, 75724 Paris, France; Jaume Bertranpetit, Evolutionary Biology Unit, Department of Experimental and Health Sciences, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona 08003, Catalonia, Spain; David Comas, Evolutionary Biology Unit, Department of Experimental and Health Sciences, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona 08003, Catalonia, Spain; Chris Tyler-Smith, The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Wellcome Trust Genome Campus, Hinxton, Cambs CB10 1SA, UK; Elena Balanovska, Research Centre for Medical Genetics, Russian Academy of Medical Sciences, Moscow 115478, Russia; Oleg Balanovsky, Research Centre for Medical Genetics, Russian Academy of Medical Sciences, Moscow 115478, Russia; Doron M. Behar, Molecular Medicine Laboratory, Rambam Health Care Campus, Haifa 31096, Israel and Genomics Research Center, Family Tree DNA, Houston, TX 77008, USA; R. John Mitchell, Department of Genetics, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Victoria, 3086, Australia; Li Jin, Fudan University, Shanghai, China; Himla Soodyall, Division of Human Genetics, National Health Laboratory Service, Johannesburg, 2000, South Africa; Ramasamy Pitchappan, Department of Immunology, Madurai Kamaraj University, Madurai 625021 Tamil Nadu, India; Alan Cooper, Division of Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Adelaide, South Australia 5005, Australia; Ajay K. Royyuru, Computational Biology Center, IBM T.J. Watson Research Center, Yorktown Heights, NY 10598, USA; Saharon Rosset, Department of Statistics and Operations Research, School of Mathematical Sciences, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv 69978, Israel and Data Analytics Research Group, IBM T.J. Watson Research Center, Yorktown Heights, NY 10598, USA; Laxmi Parida, Computational Biology Center, IBM T.J. Watson Research Center, Yorktown Heights, NY 10598, USA; Jason Blue-Smith, Mission Programs, National Geographic Society, Washington, D.C. 20036, USA; David Soria Hernanz, Mission Programs, National Geographic Society, Washington, D.C. 20036, USA; and R. Spencer Wells, Mission Programs, National Geographic Society, Washington, D.C. 20036, USA.

References

- 1.Cann R.L., Stoneking M., Wilson A.C. Mitochondrial DNA and human evolution. Nature. 1987;325:31–36. doi: 10.1038/325031a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Underhill P.A., Kivisild T. Use of Y chromosome and mitochondrial DNA population structure in tracing human migrations. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2007;41:539–564. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.41.110306.130407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mellars P. Going east: New genetic and archaeological perspectives on the modern human colonization of Eurasia. Science. 2006;313:796–800. doi: 10.1126/science.1128402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Macaulay V., Hill C., Achilli A., Rengo C., Clarke D., Meehan W., Blackburn J., Semino O., Scozzari R., Cruciani F. Single, rapid coastal settlement of Asia revealed by analysis of complete mitochondrial genomes. Science. 2005;308:1034–1036. doi: 10.1126/science.1109792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Torroni A., Achilli A., Macaulay V., Richards M., Bandelt H.J. Harvesting the fruit of the human mtDNA tree. Trends Genet. 2006;22:339–345. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mellars P. Why did modern human populations disperse from Africa ca. 60,000 years ago? A new model. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:9381–9386. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510792103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hawks J., Wang E.T., Cochran G.M., Harpending H.C., Moyzis R.K. Recent acceleration of human adaptive evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:20753–20758. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707650104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kivisild T., Shen P., Wall D.P., Do B., Sung R., Davis K., Passarino G., Underhill P.A., Scharfe C., Torroni A. The role of selection in the evolution of human mitochondrial genomes. Genetics. 2006;172:373–387. doi: 10.1534/genetics.105.043901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mishmar D., Ruiz-Pesini E., Golik P., Macaulay V., Clark A.G., Hosseini S., Brandon M., Easley K., Chen E., Brown M.D. Natural selection shaped regional mtDNA variation in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:171–176. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0136972100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maca-Meyer N., Gonzalez A.M., Larruga J.M., Flores C., Cabrera V.M. Major genomic mitochondrial lineages delineate early human expansions. BMC Genet. 2001;2:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-2-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Forster P. Ice Ages and the mitochondrial DNA chronology of human dispersals: A review. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2004;359:255–264. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2003.1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Watson E., Forster P., Richards M., Bandelt H.J. Mitochondrial footprints of human expansions in Africa. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1997;61:691–704. doi: 10.1086/515503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kivisild T., Reidla M., Metspalu E., Rosa A., Brehm A., Pennarun E., Parik J., Geberhiwot T., Usanga E., Villems R. Ethiopian mitochondrial DNA heritage: Tracking gene flow across and around the gate of tears. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2004;75:752–770. doi: 10.1086/425161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olivieri A., Achilli A., Pala M., Battaglia V., Fornarino S., Al-Zahery N., Scozzari R., Cruciani F., Behar D.M., Dugoujon J.M. The mtDNA legacy of the Levantine early Upper Palaeolithic in Africa. Science. 2006;314:1767–1770. doi: 10.1126/science.1135566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salas A., Richards M., De la Fe T., Lareu M.V., Sobrino B., Sanchez-Diz P., Macaulay V., Carracedo A. The making of the African mtDNA landscape. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2002;71:1082–1111. doi: 10.1086/344348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quintana-Murci L., Quach H., Harmant C., Luca F., Massonnet B., Patin E., Sica L., Mouguiama-Daouda P., Comas D., Tzur S. Maternal traces of deep common ancestry and asymmetric gene flow between Pygmy hunter-gatherers and Bantu-speaking farmers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:1596–1601. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711467105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen Y.S., Olckers A., Schurr T.G., Kogelnik A.M., Huoponen K., Wallace D.C. mtDNA variation in the South African Kung and Khwe-and their genetic relationships to other African populations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2000;66:1362–1383. doi: 10.1086/302848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knight A., Underhill P.A., Mortensen H.M., Zhivotovsky L.A., Lin A.A., Henn B.M., Louis D., Ruhlen M., Mountain J.L. African Y chromosome and mtDNA divergence provides insight into the history of click languages. Curr. Biol. 2003;13:464–473. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00130-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tishkoff S.A., Gonder M.K., Henn B.M., Mortensen H., Knight A., Gignoux C., Fernandopulle N., Lema G., Nyambo T.B., Ramakrishnan U. History of click-speaking populations of Africa inferred from mtDNA and Y chromosome genetic variation. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2007;24:2180–2195. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vigilant L., Stoneking M., Harpending H., Hawkes K., Wilson A.C. African populations and the evolution of human mitochondrial DNA. Science. 1991;253:1503–1507. doi: 10.1126/science.1840702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barnard A. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1992. Hunters and Herders of Southern Africa: A Comparative Ethnography of the Khoisan Peoples. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guldemann T. Mouton de Gruyter; Berlin: 2007. Quotative Indexes in African Languages: A Synchronic and Diachronic Survey. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ingman M., Kaessmann H., Paabo S., Gyllensten U. Mitochondrial genome variation and the origin of modern humans. Nature. 2000;408:708–713. doi: 10.1038/35047064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howell N., Elson J.L., Turnbull D.M., Herrnstadt C. African laplogroup L mtDNA sequences show violations of clock-like evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2004;21:1843–1854. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Behar D.M., Metspalu A., Kivisild T., Rosset S., Tzur S., Hadid Y., Yodkovsky G., Rosengarten D., Pereira L., Amorim A. Counting the founders: The matrilineal genetic ancestry of the Jewish Diaspora. PLoS ONE. 2008 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002062. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taylor R.W., Taylor G.A., Durham S.E., Turnbull D.M. The determination of complete human mitochondrial DNA sequences in single cells: Implications for the study of somatic mitochondrial DNA point mutations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29 doi: 10.1093/nar/29.15.e74. E74–E74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andrews R.M., Kubacka I., Chinnery P.F., Lightowlers R.N., Turnbull D.M., Howell N. Reanalysis and revision of the Cambridge reference sequence for human mitochondrial DNA. Nat. Genet. 1999;23:147. doi: 10.1038/13779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ewing B., Green P. Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. II. Error probabilities. Genome Res. 1998;8:186–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ewing B., Hillier L., Wendl M.C., Green P. Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. I. Accuracy assessment. Genome Res. 1998;8:175–185. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.3.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Torroni A., Sukernik R.I., Schurr T.G., Starikorskaya Y.B., Cabell M.F., Crawford M.H., Comuzzie A.G., Wallace D.C. mtDNA variation of aboriginal Siberians reveals distinct genetic affinities with Native Americans. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1993;53:591–608. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Richards M.B., Macaulay V.A., Bandelt H.J., Sykes B.C. Phylogeography of mitochondrial DNA in western Europe. Ann. Hum. Genet. 1998;62:241–260. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-1809.1998.6230241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Salas A., Richards M., Lareu M.V., Scozzari R., Coppa A., Torroni A., Macaulay V., Carracedo A. The African diaspora: Mitochondrial DNA and the Atlantic slave trade. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2004;74:454–465. doi: 10.1086/382194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Batini C., Coia V., Battaggia C., Rocha J., Pilkington M.M., Spedini G., Comas D., Destro-Bisol G., Calafell F. Phylogeography of the human mitochondrial L1c haplogroup: Genetic signatures of the prehistory of Central Africa. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2007;43:635–644. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2006.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Torroni A., Rengo C., Guida V., Cruciani F., Sellitto D., Coppa A., Calderon F.L., Simionati B., Valle G., Richards M. Do the four clades of the mtDNA haplogroup L2 evolve at different rates? Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2001;69:1348–1356. doi: 10.1086/324511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gonder M.K., Mortensen H.M., Reed F.A., de Sousa A., Tishkoff S.A. Whole-mtDNA genome sequence analysis of ancient African lineages. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2007;24:757–768. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang Z. PAML: A program package for phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 1997;13:555–556. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/13.5.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bandelt H.-J., Kong Q.-P., Richards M., Macaulay V. Estimation of mutation rates and coalescence times: Some caveats. In: Bandelt H.-J., Macaulay V., Richards M., editors. Human Mitochondrial DNA and the Evolution of Homo sapiens. Springer; Berlin: 2006. pp. 47–90. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Benjamini Y., Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. [Ser A] 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benjamini Y., Yekutieli D. The control of the false discovery rate in multiple testing under dependency. Ann. Statist. 2001;29:1165–1188. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Howell N., Elson J.L., Turnbull D.M., Herrnstadt C. African Haplogroup L mtDNA sequences show violations of clock-like evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2004;21:1843–1854. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oliver R. The problem of the Bantu expansion. J. Afr. Hist. 1966;7:361–376. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Manica A., Amos W., Balloux F., Hanihara T. The effect of ancient population bottlenecks on human phenotypic variation. Nature. 2007;448:346–348. doi: 10.1038/nature05951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leakey M.G., Spoor F., Brown F.H., Gathogo P.N., Kiarie C., Leakey L.N., McDougall I. New hominin genus from eastern Africa shows diverse middle Pliocene lineages. Nature. 2001;410:433–440. doi: 10.1038/35068500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Klein R. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1999. The Human Career. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bouzouggar A., Barton N., Vanhaeren M., d'Errico F., Collcutt S., Higham T., Hodge E., Parfitt S., Rhodes E., Schwenninger J.L. 82,000-year-old shell beads from North Africa and implications for the origins of modern human behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:9964–9969. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703877104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Henshilwood C.S., d'Errico F., Yates R., Jacobs Z., Tribolo C., Duller G.A., Mercier N., Sealy J.C., Valladas H., Watts I. Emergence of modern human behavior: Middle Stone Age engravings from South Africa. Science. 2002;295:1278–1280. doi: 10.1126/science.1067575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Walter R.C., Buffler R.T., Bruggemann J.H., Guillaume M.M., Berhe S.M., Negassi B., Libsekal Y., Cheng H., Edwards R.L., von Cosel R. Early human occupation of the Red Sea coast of Eritrea during the last interglacial. Nature. 2000;405:65–69. doi: 10.1038/35011048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cohen A.S., Stone J.R., Beuning K.R., Park L.E., Reinthal P.N., Dettman D., Scholz C.A., Johnson T.C., King J.W., Talbot M.R. Ecological consequences of early Late Pleistocene megadroughts in tropical Africa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:16422–16427. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703873104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thangaraj K., Chaubey G., Kivisild T., Reddy A.G., Singh V.K., Rasalkar A.A., Singh L. Reconstructing the origin of Andaman Islanders. Science. 2005;308:996. doi: 10.1126/science.1109987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. African Hg L Phylogeny

Table S1. Source, Demography, and Genotyping Parameters of the 624 Complete mtDNA Sequences