Inactivation of clathrin heavy chain inhibits synaptic recycling but allows bulk membrane uptake (original) (raw)

Abstract

Synaptic vesicle reformation depends on clathrin, an abundant protein that polymerizes around newly forming vesicles. However, how clathrin is involved in synaptic recycling in vivo remains unresolved. We test clathrin function during synaptic endocytosis using clathrin heavy chain (chc) mutants combined with chc photoinactivation to circumvent early embryonic lethality associated with chc mutations in multicellular organisms. Acute inactivation of chc at stimulated synapses leads to substantial membrane internalization visualized by live dye uptake and electron microscopy. However, chc-inactivated membrane cannot recycle and participate in vesicle release, resulting in a dramatic defect in neurotransmission maintenance during intense synaptic activity. Furthermore, inactivation of chc in the context of other endocytic mutations results in membrane uptake. Our data not only indicate that chc is critical for synaptic vesicle recycling but they also show that in the absence of the protein, bulk retrieval mediates massive synaptic membrane internalization.

Introduction

During intense activity, neurons can release massive amounts of neurotransmitters. To ensure continuous neuronal communication, new vesicles are efficiently recycled at the synapse. Although vesicles may be internalized by various mechanisms (He and Wu, 2007), the majority of synaptic vesicles appear to recycle through a pathway involving clathrin (Pearse, 1976; Verstreken et al., 2002; Granseth et al., 2006). Despite the importance of clathrin-mediated endocytosis in synaptic vesicle recycling, the molecular mechanisms by which vesicles form during this process remain under intense investigation.

In clathrin-mediated endocytosis, several proteins and lipids cooperate to bend the membrane and pinch of new vesicles. High resolution microscopic analyses indicate that clathrin heavy chain (chc) lines these invaginating membranes, suggesting an important role for the protein in vesicle retrieval (Heuser, 1980; Ehrlich et al., 2004). The function of chc in synaptic vesicle retrieval has been largely inferred from in vitro studies (Kirchhausen, 2000). Indeed, chc can polymerize in pentagonal and hexagonal structures of various curvature, even in the absence of membranes or adaptors (Ungewickell and Branton, 1981; Pearse and Robinson, 1984). Furthermore, chc has been shown to interact with a cohort of proteins implicated in endocytosis (Jung and Haucke, 2007). Although some interactions may be weak, chc polymers have been proposed to serve as scaffolding interaction hubs, regulating the concerted binding of endocytic proteins or even providing driving force during vesicle formation (Hinrichsen et al., 2006; Schmid et al., 2006).

Despite the abundance of in vitro studies, the mechanisms of membrane recycling in the absence of chc in neurons are much less clear. RNAi-mediated knockdown of chc in hippocampal neurons results in defective synaptic vesicle recycling, as gauged by altered fluorescence dynamics of the vesicle-associated synaptopHluorin. This probe is a pH-sensitive GFP reporting the balance between vesicle fusion and vesicle reacidification after endocytosis (Miesenbock et al., 1998). Unlike controls, stimulated neurons with reduced chc levels do not quench the synaptopHluorin GFP signal efficiently, suggesting that chc is involved in recycling at a step before acidification of newly internalized membranes (Granseth et al., 2006). However, how chc aids in the endocytosis of synaptic vesicles and why vesicle recycling is stalled in neurons with reduced chc levels remains unresolved.

Chc can combine with clathrin light chain (clc) to form stable triskelia that can polymerize at the membrane. Although the role of clc in cellular function has been analyzed in several studies (Moskowitz et al., 2003; Newpher et al., 2006; Heerssen et al., 2008), chc and clc are not constitutively bound (Girard et al., 2005) and specific partners for each of the proteins have been described (Legendre-Guillemin et al., 2002; Xiao et al., 2006). Aside from a role for clc in vesicle recycling, recent studies in yeast and mammalian cell lines indicate a role for clc in stimulation of actin assembly and localization of various proteins (Newpher et al., 2006). Hence, despite the notion that chc and clc can bind, some of their functions may be divergent.

In this paper, using genetic analyses, we study endocytosis in the absence of chc and investigate the synaptic function of chc, the major component of the synaptic vesicle coat (Kirchhausen, 2000). Although chc mutants in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Dictyostelium discoideum point to a role for the protein in cellular viability (Payne et al., 1987; Lemmon et al., 1990; Ruscetti et al., 1994), loss of chc in multicellular organisms such as fruit flies leads to early lethality, precluding a detailed analysis of synaptic function in these mutants (Bazinet et al., 1993). We have therefore used pharmacology and acute fluorescein-assisted light inactivation (FALI; Marek and Davis, 2002) of chc expressed under endogenous control, circumventing early lethality and developmental defects associated with _chc_-null mutants. Surprisingly, loss of chc function does not block synaptic membrane uptake but allows massive internalization of membranes as gauged by live dye uptake and EM. However, this membrane cannot participate in a new round of release. As a consequence, although loss of chc function does not affect neurotransmission during low frequency stimulation, mutants fail to maintain neurotransmitter release during intense activity. Collectively, our data indicate that chc is critical for synaptic recycling and that in the absence of chc, a form of bulk membrane retrieval mediates synaptic membrane uptake.

Results

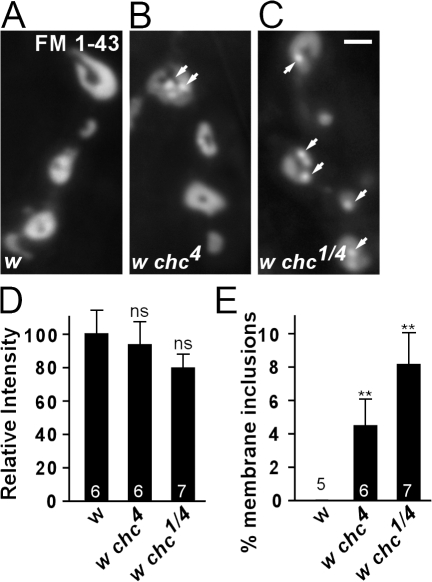

Synaptic membrane is internalized in chc mutants

To evaluate the function of chc in synaptic vesicle endocytosis in multicellular organisms, we used Drosophila melanogaster chc mutants (chc1 and chc4). The synapses of these mutants have not yet been studied in detail (Bazinet et al., 1993). Although _chc1_-null mutants die as embryos, chc4 homozygous or chc1/chc4 trans-heterozygous hypomorphic mutants survive until the pupal stage. The lethal phase of chc hypomorphic mutant animals allows us to assess endocytosis at the third instar neuromuscular junction (NMJ), a model synapse. To measure synaptic vesicle formation in hypomorphic chc mutants, we induced exo- and endocytosis by stimulating controls and mutants for 10 min with 90 mM KCl in the presence of FM 1-43, a dye which, upon nerve stimulation, becomes internalized in newly formed vesicles (Betz and Bewick, 1992; Verstreken et al., 2008). If chc is required as a scaffolding surface during vesicle formation, we expect loss of chc function to yield less membrane uptake. Conversely, if chc polymers are permissive for synaptic vesicle formation and, in the absence of chc function, another form of membrane recycling takes over, FM 1-43 dye uptake is not expected to be blocked. Interestingly, controls and hypomorphic chc mutants stimulated in the presence of FM 1-43 both internalize dye (Fig. 1, A–D). Also, shorter stimulation periods (1 min) show a similar amount of dye internalized in controls and mutants, indicating that decreased chc function does not reduce membrane uptake. However, although in control boutons internalized FM 1-43 distributes in a typical doughnut-like shape (Ramaswami et al., 1994), in chc4 and chc1/chc4 animals FM 1-43 additionally often concentrates in subsynaptic structures (Fig. 1 E). This defect in FM 1-43 labeling in chc mutants is not because of major morphological defects, such as a reduction in bouton size or addition of satellite boutons at the NMJ, as determined by immunohistochemistry (Fig. S1, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200804162/DC1). Hence, our data indicate that membrane uptake during stimulation is not blocked in hypomorphic chc mutants.

Figure 1.

Synaptic membrane internalization in chc hypomorphic mutants. (A–C) FM 1-43 labeling of endocytosed membrane at the NMJ of D. melanogaster third instar larvae. The motor neurons of w control (A), w chc4 (B), and w chc1/w chc4 (C) female larvae were stimulated for 10 min with 90 mM KCl. Labeling is visible in NMJ boutons of both mutants and controls. However, in clathrin mutants, aberrant membranous structures not seen in controls are observed (arrows). Bar, 2.5 μm. (D and E) Quantification of the FM 1-43 labeling intensity (D) and membrane inclusion surface area (E), both normalized to total bouton surface area. The total amount of membrane internalized in chc mutants and controls is not significantly different (P = 0.55, ANOVA). However, membrane inclusions, which are not observed in controls, occupy 4–8% of the bouton surface area in chc mutants (P = 0.043, ANOVA). The number of animals tested is indicated in the bar graphs and error bars indicate SEM. t test: **, P < 0.01.

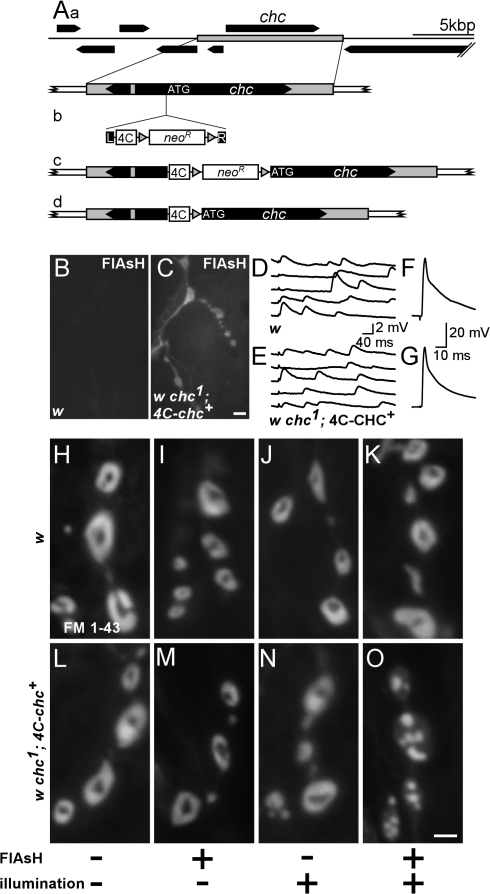

Photoinactivation of chc allows formation of abnormal membrane inclusions upon stimulation

Our studies of chc partial loss-of-function mutants provide insight into the function of this protein at the synapse. Nevertheless, an analysis of chc-null mutants or severe hypomorphic mutants is required to scrutinize the full effect of chc on endocytosis. Because lingering maternal component in embryonic lethal chc1 mutants and the small size of embryonic NMJs complicates such analyses, we used the strong neuronal GAL 4 driver nsybGal4 (gift from B. Dickson, Research Institute of Molecular Pathology, Vienna, Austria) to express high levels of chc RNAi in the larval nervous system in an attempt to create third instar larvae with reduced chc levels at the synapse. However, Western blotting only revealed a marginal decrease of chc levels, precluding analysis of chc function using this tool (unpublished data).

To acutely inactivate the chc protein in synaptic boutons, we resorted to FALI (4′,5′-bis(1,3,2-dithioarsolan-2-yl)fluorescein [FlAsH]–FALI; Marek and Davis, 2002; Tour et al., 2003), a technique previously used to specifically and acutely inactivate synaptotagmin I (sytI) and clc at the D. melanogaster NMJ (Marek and Davis, 2002; Heerssen et al., 2008). Expression of tagged proteins in D. melanogaster can be achieved with the UAS–GAL4 system, resulting in high cellular levels of the target protein. However, to avoid using overexpression of a tagged chc protein, we cloned the full-length chc gene, including its endogenous promoter, by recombineering mediated gap repair into P(acman) (Fig. 2 A, a; Venken et al., 2006). To engineer a FLAG-Tetracysteine tag (4C) either 5′ or 3′ of the chc ORF, we used an additional recombineering step involving positive selection followed by Cre-mediated cassette removal (Fig. 2 A, b–d; Venken et al., 2008). When present in the fly genome, this 4C-chc construct is expressed as gauged by Western blotting using anti-Flag antibodies. Furthermore, addition of the membrane-permeable FlAsH reagent (Griffin et al., 1998), which tightly binds the 4C tag in vivo (Marek and Davis, 2002), shows fluorescence concentrated at third instar NMJ boutons and lower levels in the muscle, which is in line with the endogenous localization of chc (Fig. 2, B and C; Zhang et al., 1998). w chc1 flies that express N-terminally tagged chc (4C-chc+), but not the C-terminally tagged chc, are fully viable and do not demonstrate behavioral defects. In addition, the morphology of their third instar larval NMJs is indistinguishable from controls, postsynaptic receptors are clustered normally, and neurotransmitter release in response to low and high frequency nerve stimulation, whether 4C-chc+ is bound to FlAsH or not, is similar to controls (Fig. 2, D–G; and Fig. S2, available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200804162/DC1). These results indicate that 4C-chc+ can fully compensate for the chc1 mutation and confirm earlier results that the chc1 mutation only affects the chc gene (Bazinet et al., 1993).

Figure 2.

Photoinactivation of chc protein reveals uncontrolled membrane uptake upon stimulation. (A) Creation of a genetic rescue construct encoding chc fused with an N-terminal FLAG-tetracysteine tag (4C), 4C-chc+. (a) Gap-repaired genomic rescue fragment including the chc gene. (b) PCR product containing left (L) and right (R) homology arms, the 4C tag, and LoxP site (gray triangles) flanked Kan marker. (c) A correct recombination event followed by _Cre_-mediated removal of the Kan marker results in a 4C-tagged chc, leaving an in-frame LoxP site as linker. (B and C) Expression of 4C-chc+. w control and w chc1; 4C-chc+ third instar larval dissections were treated with the membrane-permeable dye FlAsH, and unbound FlAsH was washed away. Labeling in boutons and muscle was only detected in animals containing the 4C tag. Bar, 5 μm. (D–G) EJPs recorded from muscle 6 in HL3 with 0.25 mM calcium (D and E) and in 2 mM calcium (F and G) in both w control and w chc1; 4C-chc+ larvae. EJPs from both genotypes are not different. (H–O) Photoinactivation of chc protein by FlAsH-FALI results in aberrant membrane internalizations. w control (H–K) and w chc1; 4C-chc+ (L–O) animals were treated (+) or not treated (−) with FlAsH and/or illuminated with 500 nm epifluorescent light for 10 min (+) or not (−), as indicated at the bottom. After treatment, motor neurons were stimulated with 90 mM KCl for 10 min in the presence of FM 1-43. Excess dye was washed away and boutons were imaged. Note abnormal membranous structures in w chc1; 4C-chc+ animals where chc was inactivated using FlAsH-FALI only. Bar, 2.5 μm.

To test chc function in endocytosis, we first incubated controls and w chc1; 4C-chc+ NMJs in FlAsH reagent, washed unbound FlAsH away with wash buffer, and illuminated the NMJs with 500 ± 12 nm of epifluorescent light, effectively inactivating the chc protein. To induce exo- and endocytosis, we then stimulated the synapses for 10 min with 90 mM KCl in the presence of FM 1-43. w controls with or without FlAsH and with or without illumination show normal uptake and distribution of the dye (Fig. 2, H–K). Likewise, w chc1; 4C-chc+ animals either treated with FlAsH (Fig. 2 M) or illuminated for 10 min (Fig. 2 N) show normal uptake and distribution of the dye. However, when, before FM 1-43 labeling, w chc1; 4C-chc+ animals are treated with FlAsH and are illuminated to photoinactivate chc (FlAsH-FALI), we still observe massive dye uptake that appears to distribute in subboutonic membranous structures (Fig. 2 O). Quantification of dye labeling intensity in synapses with photoinactivated chc compared with each of the control conditions does not show a statistically significant difference, indicating similar amounts of membrane uptake (analysis of variance [ANOVA]: P < 0.05; _n_ > 4 per condition). In addition, when we use different stimulation paradigms (e.g., 2 or 3 min of 90 mM KCl or 10 min of 10-Hz nerve stimulation), we observe FM 1-43 dye uptake into abnormal membranous structures upon FlAsH-FALI of chc, indicating that the observed membrane internalization is not a function of a specific stimulation protocol (Kuromi and Kidokoro, 2005). These phenotypes are also not an artifact of FlAsH-FALI, as photoinactivation of 4C-SytI shows less FM 1-43 dye uptake and no membranous structures similar to those observed in the chc loss-of-function synapses when subjected to the same labeling and stimulation protocol (Marek and Davis, 2002). Hence, FlAsH-FALI of chc specifically inactivates chc function, and the data indicate that loss of chc does not block membrane internalization at the D. melanogaster NMJ.

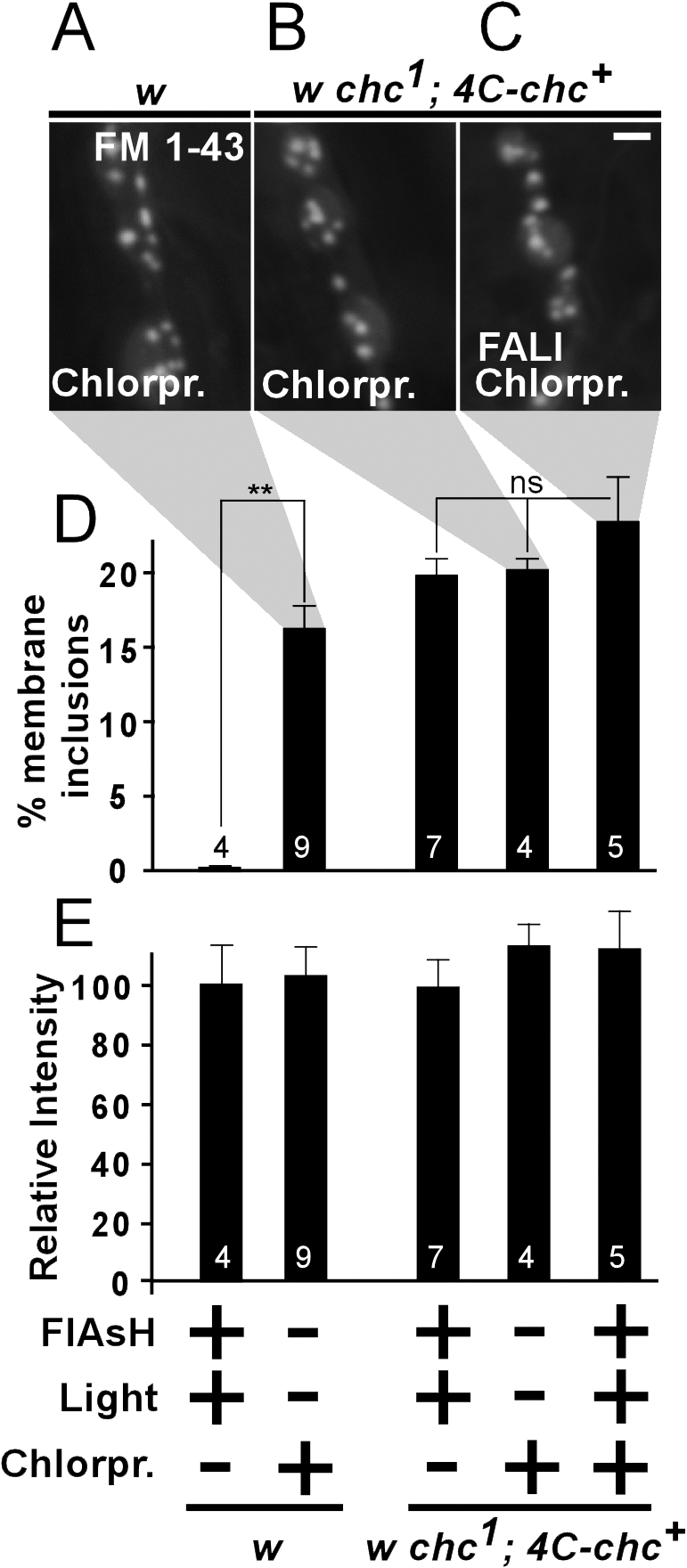

Chlorpromazine treatment phenocopies photoinactivation of chc

To corroborate these results, we used chlorpromazine, a widely used membrane-permeable compound which inhibits chc (Wang et al., 1993; Blanchard et al., 2006; Kanerva et al., 2007). Dissected larvae were incubated for 30 min in 50 μM chlorpromazine (in Schneider's medium) and were then stimulated using 90 mM KCl in the presence of FM 1-43. Interestingly, the defects in dye uptake in these animals are very reminiscent of those observed in w chc1; 4C-chc+ synapses where chc was inactivated using FlAsH-FALI (Fig. 3, A, B, D, and E). In fact, quantitative analysis of FM 1-43 uptake in w chc1; 4C-chc+ synapses that underwent FlAsH-FALI of chc or control synapses treated with chlorpromazine do not show a statistical difference in membrane uptake (Fig. 3 E) and size of the membranous structures internalized (Fig. 3 D). These data indicate that both photoinactivation of chc and chlorpromazine are effective at inhibiting chc function and further substantiate the idea that loss of chc function does not block membrane internalization.

Figure 3.

Both chemical inhibition and photoinactivation of chc protein show aberrant membrane inclusions that are quantitatively similar. (A–C) FM 1-43 dye uptake (10 min of 90 mM KCl) in synaptic boutons after chlorpromazine treatment on w control (A) and w chc1; 4C-chc+ (B) animals, as well as on chlorpromazine-treated w chc1; 4C-chc+ where chc was also inactivated using FlAsH-FALI (C). Aberrant FM 1-43–labeled membrane inclusions are clearly visible in all conditions. Bar, 2.5 μm. (D and E) Quantification of membrane inclusion surface normalized to total bouton surface (D) and relative FM 1-43 labeling intensity compared with w controls (E) in different conditions (FlAsH-treated and illuminated, chlorpromazine-treated, or both). Membrane inclusion phenotypes of double-treated animals are not significantly different than phenotypes in animals where chc was inactivated with either chlorpromazine or with FlAsH-FALI (P = 0.22, ANOVA). Furthermore, labeling intensity between the different conditions is not statistically different and is also not different from w controls that were not FlAsH treated or illuminated (w treated with FlAsH and illuminated, 100 ± 14%; w not FlAsH treated or illuminated, 105 ± 11%; Fig. 2 H; P = 0.9, ANOVA). The number of animals tested is indicated in the bars and error bars indicate SEM. ANOVA: **, P < 0.0001.

To determine if FlAsH-FALI of chc in w chc1; 4C-chc+ animals leads to severe inactivation of chc function, we used chlorpromazine in combination with FlAsH-FALI. If photoinactivation of chc is complete, the additional chlorpromazine treatment should not exacerbate the observed defects. We therefore treated w chc1; 4C-chc+ animals with chlorpromazine and subjected the animals to FlAsH-FALI of chc (Fig. 3 C). Next, NMJs were stimulated in FM 1-43 and imaged. Quantification of FM 1-43–marked membranous structures in w chc1; 4C-chc+ that underwent FlAsH-FALI and were treated with chlorpromazine is not significantly different from chc photoinactivation alone, suggesting that FlAsH-FALI of chc in w chc1; 4C-chc+ creates NMJ synapses with no or almost no functional chc, as gauged by FM 1-43 dye uptake (Fig. 3, C and D).

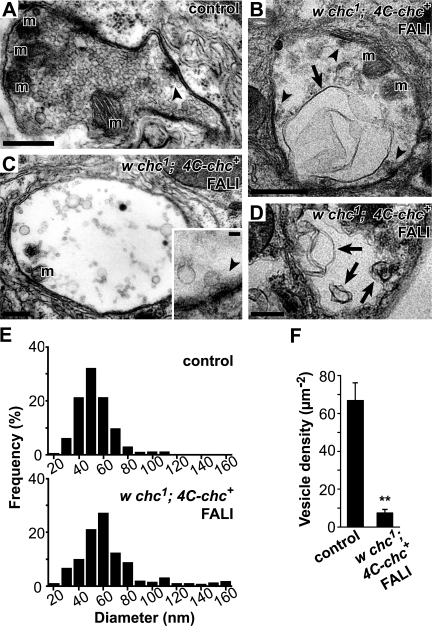

Synapses with photoinactivated chc show dramatic ultrastructural defects

To further characterize the nature of the membrane internalized upon photoinactivation of chc we performed EM on synaptic boutons. Motor neurons of w chc1; 4C-chc+ larvae that did or did not (controls) undergo FlAsH-FALI of chc were stimulated for 10 min with 90 mM KCl and were subsequently processed for EM. Notably, synaptic boutons with photoinactivated chc are almost devoid of synaptic vesicles and show giant membrane invaginations, with some measuring up to >1 μm in cross section (Fig. 4, A–D). Compared with controls, we also note a decrease in vesicle number per area (chc, 7.7 ± 4.7% of controls) and an increase in vesicle size in NMJs where chc was photoinactivated. The remaining round or oval-shaped vesicles in these boutons clearly show heterogeneity in size and a population of larger vesicles and cisternae is readily observed (Fig. 4, E and F). In contrast to these membrane morphology defects, other boutonic features, including active zones, mitochondria, and subsynaptic reticulum, are present in both control and synapses where chc was inactivated by FlAsH-FALI (Fig. 4). We also observe very similar ultrastructural defects in synapses that underwent acute FlAsH-FALI of chc when we use different fixation protocols before preparation for EM (see Materials and methods), arguing against fixation artifacts causing the defects. Hence, consistent with the FM 1-43 dye uptake studies, inactivation of chc in stimulated NMJs leads to the formation of large membrane sheets and cisternae and a concomitant reduction in synaptic vesicle number.

Figure 4.

Photoinactivation of chc causes massive membrane invaginations and a dramatic reduction in vesicle density. (A–D) Electron micrographs of synaptic bouton cross sections (muscles 6 and 7). (A) w chc1; 4C-chc+ control bouton stimulated with 90 mM KCl for 10 min but not incubated in FlAsH. (B–D) Images from stimulated w chc1; 4C-chc+ boutons where chc was inactivated using FlAsH-FALI. Note massive membrane invaginations, cisternae, and larger vesicles in boutons lacking functional chc (arrows) not observed in controls. Dense bodies (arrowheads and inset) in synapses where chc was inactivated consistently show clustered vesicles. m, mitochondria. A and C, conventional EM; B, inset, and D, high voltage EM. Bars: (A–D) 0.6 μm; (inset) 0.1 μm. (E) Histograms presenting the vesicle diameter in control (top) and synapses with photoinactivated chc (bottom). Cisternae and larger vesicles are readily observed when chc is inactivated. (F) Vesicle density in boutons of controls and with photoinactivated chc. Round or oval-shaped vesicles were included for quantification. Error bars indicate SEM. n, at least seven boutons per condition from different animals. t test: **, P < 0.001.

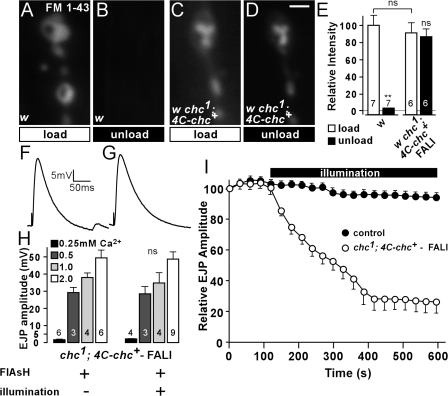

Membranes internalized in the absence of chc function fail to recycle efficiently

Loss of chc function does not block membrane internalization. However, recycling of this membrane to release sites may be inhibited in the absence of functional chc. To determine if acute loss of chc blocks membrane recycling, we used FlAsH-FALI of chc in w chc1; 4C-chc+ animals. Synapses where chc was inactivated were stimulated for 10 min in the presence of FM 1-43 to induce membrane uptake (“load”). After a 10-min wash, synapses were then stimulated again in the absence of FM 1-43 for 10 min with 90 mM KCl to induce unloading of the FM 1-43 dye (“unload”). As shown in Fig. 5 (A and C), both controls and animals where chc is photoinactivated take up dye after stimulation. However, unlike controls, a second stimulation of the synapses where chc was photoinactivated in the absence of FM 1-43 does not lead to significant unloading of the dye (Fig. 5, B and D). These data suggest that the membrane internalized in the absence of chc cannot participate in a new round of release.

Figure 5.

Acute loss of chc function by photoinactivation inhibits synaptic vesicle recycling but not neurotransmitter release. (A–D) FM 1-43 loading (10 min of 90 mM KCl; A and C) and unloading (10 min of 90 mM KCl; B and D) at the third instar NMJ in w control (A and B) and w chc1; 4C-chc+, where chc was inactivated using FlAsH-FALI (C and D). While unloading of FM 1-43–labeled vesicles using KCl stimulation in controls is efficient, labeled membrane in synapses where chc was photoinactivated is largely retained and cannot be released upon stimulation. Bar, 2.5 μm. (E) Quantification of FM 1-43 labeling intensity after loading and unloading of FM 1-43 (A–D). The number of animals tested is indicated in the bars and error bars indicate SEM. ANOVA: P = 0.67; **, P < 0.0001. (F and G) Sample EJPs recorded in 0.5 mM of extracellular calcium in w chc1; 4C-chc+ animals incubated in FlAsH, without illumination (F) and with illumination to inactivate chc (G). (H) Quantification of EJP amplitudes recorded in 0.25, 0.5, 1, and 2 mM of extracellular calcium in w chc1; 4C-chc+ animals incubated in FlAsH, without illumination and with illumination to photoinactivate chc. No difference in EJP amplitude before and after illumination was observed for each of the tested calcium concentrations. The number of animals tested is indicated in the bars and error bars indicate SEM (t test). (I) Relative EJP amplitude measured during 10 min of 10-Hz nerve stimulation in w control and w chc1; 4C-chc+ animals incubated in FlAsH reagent. Control data is pooled from w, w incubated in FlAsH, and not treated w chc1; 4C-chc+ animals (at least three animals each). All genotypes and conditions were first stimulated for 2 min while recording EJPs before illumination. EJP amplitudes were binned per 30 s and normalized to the mean amplitude of the first 10 EJPs. Note a reduction in relative EJP amplitude in w chc1; 4C-chc+, where chc is acutely inactivated by FlAsH-FALI. Error bars indicate SEM.

If membrane recycling is disrupted in chc mutants, neurotransmitter release upon mild stimulation may not be affected, whereas during intense stimulation, as more and more unreleasable membrane is internalized, neurotransmission should progressively fail. To determine the effect of loss of chc function on neurotransmitter release, we recorded excitatory junctional potentials (EJPs) from w chc1; 4C-chc+ animals during low frequency stimulation and compared the amplitude of the EJPs before and after FlAsH-FALI of chc. As shown in Fig. 5 (F and G), the EJP amplitudes of recordings made in 0.5 mM Ca2+ before and after FlAsH-FALI are not significantly different. We also did not observe a difference in EJP amplitude when recordings were made in higher (1 and 2 mM) or lower (0.25 mM) extracellular calcium concentrations (Ca2+), indicating that loss of chc does not directly influence vesicle fusion (Fig. 5 H).

To assess neurotransmission during intense activity, we stimulated controls and w chc1; 4C-chc+ animals where chc is photoinactivated at 10 Hz in 2 mM Ca2+. Controls with or without FlAsH and with or without illumination maintain neurotransmitter release well and only decline to ∼85–90% of the initial EJP amplitude (Fig. 5 I, solid circles, pooled control data). Likewise, w chc1; 4C-chc+ animals treated with FlAsH maintain release well during 10 Hz stimulation as long as the preparations are not illuminated with 500 nm of epifluorescent light and chc is not photoinactivated (Fig. 5 I, open circles, first 2 min). In contrast, EJPs in D. melanogaster dynamin mutants (shits1), which block all vesicle recycling at the restrictive temperature, would have already declined >60% after 2 min of 10 Hz stimulation at 32°C (Delgado et al., 2000; Verstreken et al., 2002). Hence, FlAsH treatment of w chc1; 4C-chc+ without photoinactivation does not affect vesicle recycling. Interestingly, when chc is acutely photoinactivated by illuminating FlAsH-treated w chc1; 4C-chc+ animals with 500 nm of light, EJPs do gradually decline and eventually drop to a mean amplitude of <25% of the initial value. Approximately 50% of the recordings even reached zero (Fig. 5 I, open circles). These data indicate that photoinactivation of chc leads to a dramatic but specific effect on vesicle recycling, corroborating our earlier findings.

Inactivation of chc in other endocytic mutants allows membrane internalization upon stimulation

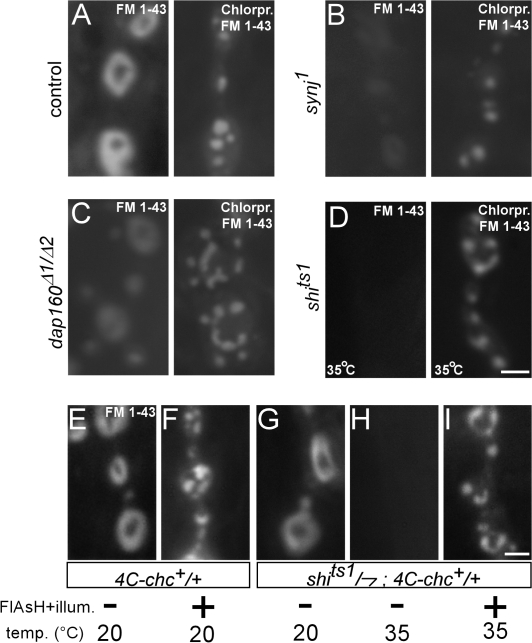

Our data indicate that in the absence of chc function, a form of bulk endocytosis persists. Interestingly, bulk retrieval was also observed in heavily stimulated synapses with high endocytic demand (Marxen et al., 1999; Holt et al., 2003; Teng et al., 2007) and in stimulated dynamin 1 mouse knockout neurons (Hayashi et al., 2008). To understand the mechanism of membrane retrieval in synapses that lack chc function better, we chemically inhibited chc in several endocytic mutants that are linked to dynamin function, including synaptojanin (synj), dap160, eps15, and shibire, and we stimulated synapses with 90 mM KCl in the presence of FM 1-43. Synj is a phosphoinositide phosphatase believed to couple dynamin-mediated vesicle fission to uncoating (Cremona et al., 1999; Harris et al., 2000; Verstreken et al., 2003; Hayashi et al., 2008), Dap160 and Esp15 maintain high dynamin concentrations at the synapse (Koh et al., 2004, 2007; Marie et al., 2004), and shibirets is a temperature-sensitive dynamin mutant that is thought to lock the protein in an inactive state at high temperature blocking membrane uptake (van der Bliek et al., 1993; Kitamoto, 2002). Interestingly, although FM 1-43 labeling is significantly reduced or blocked in synj, eps15, dap160, and shi mutants (Fig. 6, A–D, left), additional inhibition of chc in these mutants reveals membrane internalization upon stimulation of the neurons in the presence of FM 1-43 (Fig. 6, A–D, right; and not depicted). Hence, bulk membrane retrieval can occur in several endocytic mutants upon inactivation of chc.

Figure 6.

Inactivation of chc in other endocytic mutants linked to dynamin function. (A–D) KCl-induced FM 1-43 labeling of synaptic boutons of w control (A) and several endocytic mutants (synj1 [B], dap160Δ1/dap160Δ2 [C], and shits1 [D]), not treated (left) and treated (right) with chlorpromazine to inactivate chc. Animals were stimulated with 90 mM KCl in FM 1-43 for 10 min. Experiments with shits1 and CS controls (not depicted) were done at 32°C. Bar, 2.5 μm. (E and F) FlAsH-FALI of chc in +; 4C-chc+ dominantly inactivates chc. FM 1-43 labeling of +/Y; 4C-chc+/+ (obtained from crossing 4C-chc+ males to CS virgins) using 3 min of 90-mM KCl stimulation either without (E) or with (F) FlAsH-FALI of chc. Note the membrane inclusions in animals where chc was inactivated using FlAsH-FALI. (G–I) Acute double mutant shi and chc NMJs show aberrant membrane internalizations. (G and H) FM 1-43 dye uptake (3 min of 90 mM KCl) in synaptic boutons of control shits1/Y; 4C-chc+/+ animals, labeled at 20°C (G) or at 32°C (H) without FlAsH-FALI of chc. Note that the shi mutation at the restrictive temperature blocks membrane internalization. However, FM 1-43 labeling of shits1/Y; 4C-chc+/+ animals where dynamin is inactivated at high temperature (32°C) and chc is photoinactivated using FlAsH-FALI reveals clear membrane internalization (I). Bar, 2.5 μm.

To corroborate these data, we also acutely blocked chc function using photoinactivation in shits1 mutants at the restrictive temperature. First, we tested inactivation of chc using FlAsH-FALI in +/+; 4C-chc+/+. Although wild-type chc is still present in these animals, FM 1-43 labeling in +/+; 4C-chc+/+ where chc is photoinactivated shows clear membrane internalizations, indicating that FlAsH-FALI of chc in 4C-chc+ can dominantly inhibit chc function (Fig. 6, E and F). We then used FlAsH-FALI of chc in shits1/Y; 4C-chc+/+ larvae kept at the restrictive temperature to lock dynamin and stimulated synapses in the presence of FM 1-43. Although not illuminated shits1/Y; 4C-chc+/+ synapses at the restrictive temperature do not show significant FM 1-43 dye uptake upon KCl stimulation, additional photoinactivation of chc shows clear membrane internalizations (Fig. 6, G–I). In fact, within one FlAsH-treated shits1/Y; 4C-chc+/+ animal kept at the restrictive temperature, FM 1-43 dye uptake is only observed in the illuminated area, whereas synapses in neighboring segments, where only dynamin is locked using the shits1 mutation, fail to internalize significant amounts of dye. Together, these data suggest that a form of bulk retrieval can mediate membrane uptake in shi synapses when chc is inactivated.

Discussion

Chc is critical for vesicle recycling

Inhibition of chc function through a variety of approaches has been achieved in cell culture, resulting in defects in clathrin-dependent receptor-mediated endocytosis (Doxsey et al., 1987; Liu et al., 1998; Moskowitz et al., 2003). However, most of these studies did not probe into the function of chc during vesicle formation, nor did they address the role of chc during synaptic vesicle endocytosis. In this work, we inactivated chc using three independent approaches, chc hypomorphic mutants, pharmacological inhibition of chc, and FlAsH-FALI of natively expressed chc, and studied the effects on synaptic vesicle recycling.

Our work expands on our understanding of chc function in endocytosis of synaptic vesicles in two ways. First, our data indicate the critical role of chc in synaptic recycling. Synapses that lack chc function show a progressive decline in synaptic transmission during intense activity and membrane that is internalized during neuronal stimulation cannot be released in a second round of stimulation. Ultrastructural data indicates that small vesicles fail to be formed in synapses lacking functional chc, indicating a role for chc to resolve synaptic membrane into functional vesicles. Second, our data also suggest that in the absence of chc, another form of membrane internalization, not observed in controls, takes over. Indeed, we find that loss of chc function does not block membrane uptake as gauged by fluorescent FM 1-43 dye uptake. In addition, ultrastructural studies show massive membrane folds and cisternae in synapses that underwent FlAsH-FALI of chc. Collectively, our data suggest a role for chc in maintaining synaptic membrane integrity during stimulation, preventing massive bulk membrane retrieval. Interestingly, reminiscent of the large vacuoles and cisternae, we observe loss-of-function synapses in chc. Similar structures can also be seen in strongly stimulated synapses of different organisms or in D. melanogaster temperature-sensitive shi mutants that are shifted back to low temperature after endocytic blockade at high temperature (Koenig and Ikeda, 1989; Marxen et al., 1999; de Lange et al., 2003; Holt et al., 2003; Teng et al., 2007). We surmise that under such conditions, vesicle fusion rate exceeds endocytic capacity and clathrin demand may be higher than supply, resulting in bulk membrane uptake. Our work not only highlights the central role of chc in vesicle recycling and in the creation of small-diameter fusion-competent vesicles but also suggests that in the absence of chc function, a form of bulk endocytosis mediates the retrieval of synaptic membrane.

The observation that bulk retrieval takes over in the absence of chc function is consistent with loss-of-function studies of clc and α-adaptin, two other components of the endocytic coat. In nonneuronal TRVb cells, cross-linking most of the clc proteins did not inhibit membrane uptake (Moskowitz et al., 2003), and recent data on inactivation of clc in neurons indicates internalization of membranous structures upon stimulation (Heerssen et al., 2008). Similarly, in embryonic lethal α-adaptin mutants, where chc polymers fail to be efficiently linked to the synaptic membrane, a dramatic depletion in vesicle number and large membrane invaginations can be observed (Gonzalez-Gaitan and Jackle, 1997). Thus, the data suggest that in the absence of functional clathrin coats, membrane internalizes by bulk retrieval; however, the formation of small synaptic vesicles from these endocytic structures appears inhibited during a time period (>15 min; Fig. 5) that would normally be sufficiently long to repopulate the entire vesicle pool at wild-type D. melanogaster NMJs (Koenig and Ikeda, 1983; Kuromi and Kidokoro, 2005). In this context, it is interesting to note that stimulated dynamin 1 knockout neurons also show large endocytic membranes, which is consistent with the presence of bulk retrieval in these mutants (Hayashi et al., 2008). Interestingly, we observed bulk membrane retrieval in other endocytic mutants linked to dynamin function (synj) or controlling dynamin function (dap160, eps15, and shi) upon inactivation of chc. The bulk uptake in these double mutant animals is reminiscent of that observed in mouse dynamin 1 knockouts and that in fly clathrin mutant synapses and suggests an intriguing possibility where clathrin may coordinate with dynamin to form synaptic vesicles. In the absence of this function, bulk endocytosis appears to then mediate membrane retrieval.

Mechanisms of recycling

Although it is well established that synaptic vesicles recycle by clathrin-mediated endocytosis, recovery by alternative routes, including direct closure of the fusion pore, remains controversial. At the D. melanogaster NMJ, endophilin (endo) knockouts dramatically impair clathrin-mediated endocytosis; however, some neurotransmission endures during intense stimulation (Verstreken et al., 2002, 2003; Dickman et al., 2005). These data are consistent with either the presence of an alternative mode of vesicle recycling or with the persistence of low levels of clathrin-mediated endocytosis in endo mutants. Interestingly, removal of an additional component involved in clathrin-mediated endocytosis, synj, does not exacerbate the endo recycling defect (Schuske et al., 2003; Verstreken et al., 2003). Thus, these data suggest that endo mutants block most clathrin-mediated recycling and indicate that an Endo- and Synj-independent recycling mechanism can maintain the neurotransmitter release observed in these mutants.

Our work on chc, as well as recent data on clc, now allows us to further scrutinize the mechanisms of vesicle recycling at the D. melanogaster NMJ (Heerssen et al., 2008). FlAsH-FALI of 4C-clc leads to a complete block in synaptic transmission during high frequency stimulation, indicating that this condition blocks all vesicle recycling. However, our data indicates that photoinactivation of endogenously expressed 4C-chc only blocks transmission in 50% of the recordings, suggesting that some synapses may retain low levels of clathrin-independent recycling and that clc and chc may have partially divergent functions (Newpher et al., 2006; Heerssen et al., 2008). Although we cannot exclude the possibility that in our studies some functional chc remains at the synapse after FlAsH-FALI, we used very similar inactivation conditions to those that lead to complete inactivation of clc (Heerssen et al., 2008). Furthermore, FlAsH-FALI of chc and chemical inhibition of chc, or both together, does not show a quantitative difference in membrane uptake during stimulation, indicating that our protocols lead to severe, if not complete, inhibition of chc function. In addition, we did not overexpress 4C-chc but expressed it under native control in _chc1_-null mutants, ideally controlling protein levels and avoiding overexpression artifacts. Finally, EM of stimulated synapses where chc was acutely inactivated consistently show persistent active zone-associated synaptic vesicles. Some of these vesicles are similar in size to those observed in controls, and these vesicles are well positioned to participate in alternative recycling mechanisms. Hence, we believe that although our data clearly support a critical role for clathrin-mediated endocytosis in the recycling of synaptic vesicles in D. melanogaster, this work does not exclude the possibility that alternative synaptic vesicle recycling routes operate at the larval NMJ.

Materials and methods

Fly genetics and molecular biology

All fly stocks were kept on standard maize meal and molasses medium at room temperature. However, to collect third instar larvae, we reared embryos on grape juice plates and cultured them at 25°C with fresh yeast paste. Genotypes of controls and experimental samples are indicated in the figure legends. w chc1 and w chc4 flies (Bazinet et al., 1993) were obtained from the Bloomington stock center. UAS-4C-sytI transgenic flies were provided by G. Davis (University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA), and 4C-SytI was expressed in the nervous system using elav-Gal4.

The 4C-chc and chc-4C constructs were obtained using recombineering. First, the chc gene (CG9012) and the nearby 5′ located gene CG32582 were retrieved from BACR25C18 in the _attB_-P(acman)-ApR vector (obtained from H. Bellen, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX) using gap repair as previously described (Venken et al., 2006). CG32582 was included because it is located very close to the 5′ end of the chc gene and we wanted to ensure that all chc regulatory sequences were present. Primers for left and right homology arms were chc-LA-AscI-F (agg cgc gcc TAA TGA ATG AAG GAG TCG TCC)/chc-LA-BamHI-R (cgc gga tcc CCT CCT ACG CTC CCT CGC) and chc-RA-BamHI-F (cgc gga tcc TAC AGC GGC CGC GAC ATG G)/chc-RA-PacI-R (acc tta att aaA AAT TTA GAA ACT CAC AGA TAG C), respectively. Correct recombination events were isolated by colony PCR and verified by restriction enzyme fingerprinting and DNA sequencing. Second, an N- or C-terminal FLAG-4C tag was added to this construct using recombineering with a PCR fragment that includes a FLAG-4C tag (a peptide fusion between a FLAG peptide and an optimized FlAsH binding tetracysteine tag (Martin et al., 2005) and a floxed kanamycin marker (Kan), all flanked by 50-bp left and right homology arms included in the PCR primers (Fig. 2 A). The Kan marker was removed using cre recombinase expressing EL350 bacteria (Lee et al., 2001; Venken et al., 2008). Correct recombination events were isolated by colony PCR and confirmed by DNA sequencing. Constructs were injected in Δ2-3 P transposase–expressing flies, and transformants were mapped to chromosomes using standard procedures. To test if this construct produces functional chc protein, we generated w chc1; 4C-chc+ animals that survive and do not show obvious behavioral phenotypes. The 4C-chc+ insertion is located on chromosome 3.

FlAsH-FALI of chc and visualization of FlAsH fluorescence

To load the 4C tag with FlAsH reagent (Invitrogen), w and w chc1; 4C-chc+ third instar larvae were dissected in HL3 (110 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 10 mM NaHCO3, 5 mM Hepes, 30 mM sucrose, 5 mM trehalose, and 10 mM MgCl2, pH 7.2; Stewart et al., 1994). Subsequently, these larvae were treated with 1 μM (final concentration) FlAsH for 10 min while gently shaking in the dark. Unbound FlAsH was washed away by rinsing the preparations with Bal buffer (Invitrogen) diluted in HL3. Finally, samples were washed three times with HL3. Photoinactivation of chc was performed on synapses localized in segments A3 or A4 by illuminating the NMJs in a hemisegment with epifluorescent 500 ± 12-nm (Intensilight C-HGFI; Nikon) band pass–filtered light (excitation filter, 500/24; dichroic mirror, 520) for 10 min (or less depending on the protocol) through a 40× 0.8 NA water immersion lens installed on a fluorescent microscope (Eclipse F1; Nikon). Analyses of chc-inactivated synapses were performed on muscle 6 and 7.

To visualize FlAsH fluorescence, preparations were loaded with FlAsH as described in the previous paragraph and samples were imaged using epifluorescent light (Intensilight C-HGFI ) filtered using the 500/24 excitation filter and the 520 dichroic mirror, and emission was detected using the 542/27 nm filter. Images were taken as described for FM 1-43.

FM 1-43 dye labeling

Third instar larvae were dissected in HL3. Synaptic boutons were labeled with 4 μM FM 1-43 (Invitrogen) by stimulating motor neurons in HL-3 with 90 mM KCl (25 mM NaCl, 90 mM KCl, 10 mM NaHCO3, 5 mM Hepes, 30 mM sucrose, 5 mM trehalose, 10 mM MgCl2, and 1.5 mM CaCl2, pH 7.2) for 10 min (or less), as previously described (Ramaswami et al., 1994; Verstreken et al., 2008) or labeled using 10 min of 10-Hz nerve stimulation in HL-3 with 2 mM CaCl2 as previously described (Verstreken et al., 2008).

Chemical inactivation of clathrin using chlorpromazine (Sigma-Aldrich) was adapted from (Wang et al., 1993). Third instar larvae were dissected in Schneider's medium (Sigma-Aldrich) and subsequently incubated for 30 min in 50 μM chlorpromazine final concentration (in Schneider's).

Preparations were viewed with a 40× 0.8 NA water immersion lens installed on a fluorescent microscope (Eclipse F1), and 12-bit images were captured with a cooled charge-coupled device camera (DS-2MBWc; Nikon) and stored on a PC using NIS elements AR 2.30 software (Nikon). Images were taken at 20°C and processed with Photoshop 7 (Adobe).

Quantification of FM 1-43 fluorescence was performed as previously described (Verstreken et al., 2008). Membrane inclusion area versus boutonic area was quantified using automatic and manual thresholding in Amira 2.2 (Visage Imaging), NIS elements AR 2.30 (Nikon), and ImageJ (National Institutes of Health). In any case, data were quantified blindly.

Electrophysiology

Recordings from third instar NMJs were performed in HL3 with CaCl2 as indicated. Sharp (20–40 MΩ) electrodes were inserted in muscle 6 (segment A2 or A3) to measure membrane potential, and motor neurons were stimulated at an ∼2× threshold using a suction electrode. Measurements were amplified with a multiclamp 7B amplifier (MDS Analytical Technologies), digitized, and stored on a PC using Clampex 10 (MDS Analytical Technologies). Data were quantified using Clampfit 10 (MDS Analytical Technologies).

Electron microscopy

w chc1; 4C-chc+ third instar larvae were dissected in HL3 and chc was inactivated using FlAsH-FALI. Controls were the same genotype not treated with FlAsH. Preparations were subsequently stimulated in 90 mM KCl in HL3 and fixed in fresh 4% PFA and 1% glutaraldehyde in 1 mM MgCl2 and 0.1 M Na-cacodylate buffer, pH 7.2, for 2 h at room temperature. Muscles 6 and 7 of FlAsH-FALI treated segments (A2 and A3 or similar control segments) were then trimmed and subsequently fixed in the same fix solution overnight at 4°C (Torroja et al., 1999). Samples were washed in 0.1 M Na-cacodylate buffer, osmicated in fresh 1% OsO4 in 0.1 M Na-cacodylate for 2 h on ice, and then washed in ice cold water. Next, the tissue was stained en bloc with 2% uranyl acetate for 2 h and embedded in Agar100. Horizontal ultrathin sections (70 nm, up to 200 nm) were further contrast-stained on the grids with 4% uranyl acetate and lead citrate. Synaptic boutons were examined and photographed (4K-20Kx) using a transmission electron microscope at 80 or 200 kV (902A [Carl Zeiss, Inc.] or JEM-2100 [JEOL], respectively). Bouton area and vesicle diameters were measured using ImageJ. Images were processed using Photoshop 7.

We also used alternative fixation procedures yielding very similar results. In a first approach, primary fixation conditions were 0.5% PFA and 3% glutaraldehyde for 4 h at room temperature. After trimming, preparations were further fixed overnight at 4°C. After fixation, preparations were in 2% OsO4 in water for 30 min at room temperature. In an alternative approach, we used 0.5% PFA and 3% glutaraldehyde for 2 h at room temperature for primary fixation and, after trimming, preparations were further fixed overnight at 4°C. Final postfixation was in 2% OsO4 in water for 1 h at 4°C.

Immunohistochemistry

Dissected third instar larvae were fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde for 20 min and washed with 0.4% Triton X-100 in PBS. Subsequently, dissected larvae were labeled with the following antibodies: anti-HRP rabbit pAb (1:1,000; Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories), anti-Dlg mouse mAb (1:50; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank; 4F3), and anti-GluRIII/C (1:200; Marrus et al., 2004). In unpublished data, we also used anti–α-adaptin (gift from M. Gonzalez-Gaitan, Cambridge University, Cambridge, England, UK) and anti-Eps15 (gift from K. O'Kane, Cambridge University, Cambridge, England, UK). Alexa-conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) were used at 1:500. Images were captured with a confocal microscope (DMRXA; Leica) using laser light of 488- and 543-nm wavelength through a 63× 1.32 NA oil immersion lens and processed with ImageJ and Photoshop 7. Images were taken at 20°C from synapses on muscle 6 and 7.

Statistics

The statistical significance of differences between a set of two groups was evaluated using a t test. To evaluate the statistical significance of differences between more than two groups, one-way ANOVA was used for normal distributions at P = 0.05.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows that hypomorphic chc mutants do not show obvious morphological defects at their NMJs. These NMJs also do not show increased satellite boutons, a defect which is observed in some other endocytic mutants. Fig. S2 demonstrates normal NMJ morphology in _chc_-null mutants that harbor a chc+ rescue construct tagged with a tetracysteine tag. In addition, the figure also shows quantification of neurotransmitter release recorded from these animals. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.200804162/DC1.

Supplementary Material

[ Supplemental Material Index]

Acknowledgments

We thank Ralf Heinrich and Margret Winkler (Georg-August University, Goettingen, Germany) and Mieke Van Brabant and Pieter Baatsen (Center for Human Genetics, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven EM Core facility) for the use of their electron microscopes. We thank Bassem Hassan, Willem Annaert, and Patrick Callaerts for discussions and the members of the Verstreken, Hassan, and Callaerts laboratories for valuable input. We are indebted to Hugo Bellen and Koen Venken for invaluable help with designing the recombineering strategies used in this work. We thank Hugo Bellen, Graeme Davis, Barry Dickson, Marcos Gonzalez-Gaitan, and Cahir O'Kane, the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center, the Drosophila genomics resource center, and the Vienna Drosophila RNAi center for reagents and Jiekun Yan for embryo injections.

This research was supported by the research fund of the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, VIB (Flemish Institute for Biotechnology), and a Marie Curie Excellence Grant (MEXT-CT-2006-042267).

J. Kasprowicz and S. Kuenen contributed equally to this paper.

Abbreviations used in this paper: ANOVA, analysis of variance; Chc, clathrin heavy chain; Clc, clathrin light chain; EJP, excitatory junctional potential; Endo, endophilin; FALI, fluorescein-assisted light inactivation; FlAsH, 4′,5′-bis(1,3,2-dithioarsolan-2-yl)fluorescein; Kan, kanamycin; NMJ, neuromuscular junction; Synj, synaptojanin; sytI, synaptotagmin I.

References

- Bazinet, C., A.L. Katzen, M. Morgan, A.P. Mahowald, and S.K. Lemmon. 1993. The Drosophila clathrin heavy chain gene: clathrin function is essential in a multicellular organism. Genetics. 134:1119–1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betz, W.J., and G.S. Bewick. 1992. Optical analysis of synaptic vesicle recycling at the frog neuromuscular junction. Science. 255:200–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard, E., S. Belouzard, L. Goueslain, T. Wakita, J. Dubuisson, C. Wychowski, and Y. Rouille. 2006. Hepatitis C virus entry depends on clathrin-mediated endocytosis. J. Virol. 80:6964–6972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cremona, O., G. Di Paolo, M.R. Wenk, A. Luthi, W.T. Kim, K. Takei, L. Daniell, Y. Nemoto, S.B. Shears, R.A. Flavell, et al. 1999. Essential role of phosphoinositide metabolism in synaptic vesicle recycling. Cell. 99:179–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lange, R.P., A.D. de Roos, and J.G. Borst. 2003. Two modes of vesicle recycling in the rat calyx of Held. J. Neurosci. 23:10164–10173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, R., C. Maureira, C. Oliva, Y. Kidokoro, and P. Labarca. 2000. Size of vesicle pools, rates of mobilization, and recycling at neuromuscular synapses of a Drosophila mutant, shibire. Neuron. 28:941–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickman, D.K., J.A. Horne, I.A. Meinertzhagen, and T.L. Schwarz. 2005. A slowed classical pathway rather than kiss-and-run mediates endocytosis at synapses lacking synaptojanin and endophilin. Cell. 123:521–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doxsey, S.J., F.M. Brodsky, G.S. Blank, and A. Helenius. 1987. Inhibition of endocytosis by anti-clathrin antibodies. Cell. 50:453–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich, M., W. Boll, A. Van Oijen, R. Hariharan, K. Chandran, M.L. Nibert, and T. Kirchhausen. 2004. Endocytosis by random initiation and stabilization of clathrin-coated pits. Cell. 118:591–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard, M., P.D. Allaire, P.S. McPherson, and F. Blondeau. 2005. Non-stoichiometric relationship between clathrin heavy and light chains revealed by quantitative comparative proteomics of clathrin-coated vesicles from brain and liver. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 4:1145–1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Gaitan, M., and H. Jackle. 1997. Role of Drosophila alpha-adaptin in presynaptic vesicle recycling. Cell. 88:767–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granseth, B., B. Odermatt, S.J. Royle, and L. Lagnado. 2006. Clathrin-mediated endocytosis is the dominant mechanism of vesicle retrieval at hippocampal synapses. Neuron. 51:773–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, B.A., S.R. Adams, and R.Y. Tsien. 1998. Specific covalent labeling of recombinant protein molecules inside live cells. Science. 281:269–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris, T.W., E. Hartwieg, H.R. Horvitz, and E.M. Jorgensen. 2000. Mutations in synaptojanin disrupt synaptic vesicle recycling. J. Cell Biol. 150:589–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi, M., A. Raimondi, E. O'Toole, S. Paradise, C. Collesi, O. Cremona, S.M. Ferguson, and P. De Camilli. 2008. Cell- and stimulus-dependent heterogeneity of synaptic vesicle endocytic recycling mechanisms revealed by studies of dynamin 1-null neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 105:2175–2180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, L., and L.G. Wu. 2007. The debate on the kiss-and-run fusion at synapses. Trends Neurosci. 30:447–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heerssen, H., R.D. Fetter, and G.W. Davis. 2008. Clathrin dependence of synaptic-vesicle formation at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction. Curr. Biol. 18:401–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuser, J. 1980. Three-dimensional visualization of coated vesicle formation in fibroblasts. J. Cell Biol. 84:560–583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinrichsen, L., A. Meyerholz, S. Groos, and E.J. Ungewickell. 2006. Bending a membrane: how clathrin affects budding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 103:8715–8720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt, M., A. Cooke, M.M. Wu, and L. Lagnado. 2003. Bulk membrane retrieval in the synaptic terminal of retinal bipolar cells. J. Neurosci. 23:1329–1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung, N., and V. Haucke. 2007. Clathrin-mediated endocytosis at synapses. Traffic. 8:1129–1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanerva, A., M. Raki, T. Ranki, M. Sarkioja, J. Koponen, R.A. Desmond, A. Helin, U.H. Stenman, H. Isoniemi, K. Hockerstedt, et al. 2007. Chlorpromazine and apigenin reduce adenovirus replication and decrease replication associated toxicity. J. Gene Med. 9:3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchhausen, T. 2000. Clathrin. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69:699–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamoto, T. 2002. Targeted expression of temperature-sensitive dynamin to study neural mechanisms of complex behavior in Drosophila. J. Neurogenet. 16:205–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig, J.H., and K. Ikeda. 1983. Evidence for a presynaptic blockage of transmission in a temperature-sensitive mutant of Drosophila. J. Neurobiol. 14:411–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig, J.H., and K. Ikeda. 1989. Disappearance and reformation of synaptic vesicle membrane upon transmitter release observed under reversible blockage of membrane retrieval. J. Neurosci. 9:3844–3860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh, T.W., P. Verstreken, and H.J. Bellen. 2004. Dap160/intersectin acts as a stabilizing scaffold required for synaptic development and vesicle endocytosis. Neuron. 43:193–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh, T.W., V.I. Korolchuk, Y.P. Wairkar, W. Jiao, E. Evergren, H. Pan, Y. Zhou, K.J. Venken, O. Shupliakov, I.M. Robinson, et al. 2007. Eps15 and Dap160 control synaptic vesicle membrane retrieval and synapse development. J. Cell Biol. 178:309–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuromi, H., and Y. Kidokoro. 2005. Exocytosis and endocytosis of synaptic vesicles and functional roles of vesicle pools: lessons from the Drosophila neuromuscular junction. Neuroscientist. 11:138–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E.C., D. Yu, J. Martinez de Velasco, L. Tessarollo, D.A. Swing, D.L. Court, N.A. Jenkins, and N.G. Copeland. 2001. A highly efficient _Escherichia coli_-based chromosome engineering system adapted for recombinogenic targeting and subcloning of BAC DNA. Genomics. 73:56–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legendre-Guillemin, V., M. Metzler, M. Charbonneau, L. Gan, V. Chopra, J. Philie, M.R. Hayden, and P.S. McPherson. 2002. HIP1 and HIP12 display differential binding to F-actin, AP2, and clathrin. Identification of a novel interaction with clathrin light chain. J. Biol. Chem. 277:19897–19904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemmon, S.K., C. Freund, K. Conley, and E.W. Jones. 1990. Genetic instability of clathrin-deficient strains of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 124:27–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.H., M.S. Marks, and F.M. Brodsky. 1998. A dominant-negative clathrin mutant differentially affects trafficking of molecules with distinct sorting motifs in the class II major histocompatibility complex (MHC) pathway. J. Cell Biol. 140:1023–1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marek, K.W., and G.W. Davis. 2002. Transgenically encoded protein photoinactivation (FlAsH-FALI): acute inactivation of synaptotagmin I. Neuron. 36:805–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marie, B., S.T. Sweeney, K.E. Poskanzer, J. Roos, R.B. Kelly, and G.W. Davis. 2004. Dap160/intersectin scaffolds the periactive zone to achieve high-fidelity endocytosis and normal synaptic growth. Neuron. 43:207–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrus, S.B., S.L. Portman, M.J. Allen, K.G. Moffat, and A. DiAntonio. 2004. Differential localization of glutamate receptor subunits at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction. J. Neurosci. 24:1406–1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, B.R., B.N. Giepmans, S.R. Adams, and R.Y. Tsien. 2005. Mammalian cell-based optimization of the biarsenical-binding tetracysteine motif for improved fluorescence and affinity. Nat. Biotechnol. 23:1308–1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marxen, M., W. Volknandt, and H. Zimmermann. 1999. Endocytic vacuoles formed following a short pulse of K+ -stimulation contain a plethora of presynaptic membrane proteins. Neuroscience. 94:985–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miesenbock, G., D.A. De Angelis, and J.E. Rothman. 1998. Visualizing secretion and synaptic transmission with pH-sensitive green fluorescent proteins. Nature. 394:192–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskowitz, H.S., J. Heuser, T.E. McGraw, and T.A. Ryan. 2003. Targeted chemical disruption of clathrin function in living cells. Mol. Biol. Cell. 14:4437–4447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newpher, T.M., F.Z. Idrissi, M.I. Geli, and S.K. Lemmon. 2006. Novel function of clathrin light chain in promoting endocytic vesicle formation. Mol. Biol. Cell. 17:4343–4352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne, G.S., T.B. Hasson, M.S. Hasson, and R. Schekman. 1987. Genetic and biochemical characterization of clathrin-deficient Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 7:3888–3898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearse, B.M. 1976. Clathrin: a unique protein associated with intracellular transfer of membrane by coated vesicles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 73:1255–1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearse, B.M., and M.S. Robinson. 1984. Purification and properties of 100-kd proteins from coated vesicles and their reconstitution with clathrin. EMBO J. 3:1951–1957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramaswami, M., K.S. Krishnan, and R.B. Kelly. 1994. Intermediates in synaptic vesicle recycling revealed by optical imaging of Drosophila neuromuscular junctions. Neuron. 13:363–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruscetti, T., J.A. Cardelli, M.L. Niswonger, and T.J. O'Halloran. 1994. Clathrin heavy chain functions in sorting and secretion of lysosomal enzymes in Dictyostelium discoideum. J. Cell Biol. 126:343–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid, E.M., M.G. Ford, A. Burtey, G.J. Praefcke, S.Y. Peak-Chew, I.G. Mills, A. Benmerah, and H.T. McMahon. 2006. Role of the AP2 beta-appendage hub in recruiting partners for clathrin-coated vesicle assembly. PLoS Biol. 4:e262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuske, K.R., J.E. Richmond, D.S. Matthies, W.S. Davis, S. Runz, D.A. Rube, A.M. van der Bliek, and E.M. Jorgensen. 2003. Endophilin is required for synaptic vesicle endocytosis by localizing synaptojanin. Neuron. 40:749–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, B.A., H.L. Atwood, J.J. Renger, J. Wang, and C.F. Wu. 1994. Improved stability of Drosophila larval neuromuscular preparations in haemolymph-like physiological solutions. J. Comp. Physiol. [A]. 175:179–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng, H., M.Y. Lin, and R.S. Wilkinson. 2007. Macroendocytosis and endosome processing in snake motor boutons. J. Physiol. 582:243–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torroja, L., M. Packard, M. Gorczyca, K. White, and V. Budnik. 1999. The Drosophila beta-amyloid precursor protein homolog promotes synapse differentiation at the neuromuscular junction. J. Neurosci. 19:7793–7803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tour, O., R.M. Meijer, D.A. Zacharias, S.R. Adams, and R.Y. Tsien. 2003. Genetically targeted chromophore-assisted light inactivation. Nat. Biotechnol. 21:1505–1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungewickell, E., and D. Branton. 1981. Assembly units of clathrin coats. Nature. 289:420–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Bliek, A.M., T.E. Redelmeier, H. Damke, E.J. Tisdale, E.M. Meyerowitz, and S.L. Schmid. 1993. Mutations in human dynamin block an intermediate stage in coated vesicle formation. J. Cell Biol. 122:553–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venken, K.J., Y. He, R.A. Hoskins, and H.J. Bellen. 2006. P[acman]: a BAC transgenic platform for targeted insertion of large DNA fragments in D. melanogaster. Science. 314:1747–1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venken, K.J.T., J. Kasprowicz, S. Kuenen, J. Yan, B.A. Hassan, and P. Verstreken. 2008. Recombineering-mediated tagging of Drosophila genomic constructs for in vivo localization and acute protein inactivation. Nucleic Acids Res. 10.1093/nar/gkn486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Verstreken, P., O. Kjaerulff, T.E. Lloyd, R. Atkinson, Y. Zhou, I.A. Meinertzhagen, and H.J. Bellen. 2002. Endophilin mutations block clathrin-mediated endocytosis but not neurotransmitter release. Cell. 109:101–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verstreken, P., T.W. Koh, K.L. Schulze, R.G. Zhai, P.R. Hiesinger, Y. Zhou, S.Q. Mehta, Y. Cao, J. Roos, and H.J. Bellen. 2003. Synaptojanin is recruited by endophilin to promote synaptic vesicle uncoating. Neuron. 40:733–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verstreken, P., T. Ohyama, and H.J. Bellen. 2008. FM1-43 Labeling of synaptic vesicle pools at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction. In Exocytosis and Endocytosis (Methods in Molecular Biology). I.I. Ivanov, editor. Humana Press, New York. 349–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.H., K.G. Rothberg, and R.G. Anderson. 1993. Mis-assembly of clathrin lattices on endosomes reveals a regulatory switch for coated pit formation. J. Cell Biol. 123:1107–1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, J., R. Dai, L. Negyessy, and C. Bergson. 2006. Calcyon, a novel partner of clathrin light chain, stimulates clathrin-mediated endocytosis. J. Biol. Chem. 281:15182–15193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B., Y.H. Koh, R.B. Beckstead, V. Budnik, B. Ganetzky, and H.J. Bellen. 1998. Synaptic vesicle size and number are regulated by a clathrin adaptor protein required for endocytosis. Neuron. 21:1465–1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

[ Supplemental Material Index]