Control of chromosome stability by the β-TrCP–REST–Mad2 axis (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2009 Jul 9.

Published in final edited form as: Nature. 2008 Mar 20;452(7185):365–369. doi: 10.1038/nature06641

Abstract

REST/NRSF (repressor-element-1-silencing transcription factor/neuron-restrictive silencing factor) negatively regulates the transcription of genes containing RE1 sites1,2. REST is expressed in non-neuronal cells and stem/progenitor neuronal cells, in which it inhibits the expression of neuron-specific genes. Overexpression of REST is frequently found in human medulloblastomas and neuroblastomas3–7, in which it is thought to maintain the stem character of tumour cells. Neural stem cells forced to express REST and c-Myc fail to differentiate and give rise to tumours in the mouse cerebellum3. Expression of a splice variant of REST that lacks the carboxy terminus has been associated with neuronal tumours and small-cell lung carcinomas8–10, and a frameshift mutant (REST-FS), which is also truncated at the C terminus, has oncogenic properties11. Here we show, by using an unbiased screen, that REST is an interactor of the F-box protein β-TrCP. REST is degraded by means of the ubiquitin ligase SCF β-TrCP during the G2 phase of the cell cycle to allow transcriptional derepression of Mad2, an essential component of the spindle assembly checkpoint. The expression in cultured cells of a stable REST mutant, which is unable to bind β-TrCP, inhibited Mad2 expression and resulted in a phenotype analogous to that observed in Mad2+/− cells. In particular, we observed defects that were consistent with faulty activation of the spindle checkpoint, such as shortened mitosis, premature sister-chromatid separation, chromosome bridges and mis-segregation in anaphase, tetraploidy, and faster mitotic slippage in the presence of a spindle inhibitor. An indistinguishable phenotype was observed by expressing the oncogenic REST-FS mutant11, which does not bind β-TrCP. Thus, SCF β-TrCP-dependent degradation of REST during G2 permits the optimal activation of the spindle checkpoint, and consequently it is required for the fidelity of mitosis. The high levels of REST or its truncated variants found in certain human tumours may contribute to cellular transformation by promoting genomic instability.

F-box proteins are the substrate-recognition subunits of SCF (SKP1–CUL1–F-box protein) ubiquitin ligases, providing specificity to ubiquitin conjugation reactions12,13. Mammals express two paralogues of the F-box protein β-TrCP (β-TrCP1 and β-TrCP2) that are biochemically indistinguishable; we shall therefore use β-TrCP to refer to both, unless otherwise specified.

To identify substrates of the SCF β-TrCP ubiquitin ligase, we used an immunoaffinity/enzymatic assay followed by mass spectrometry analysis14,15. In two independent purifications, peptides corresponding to REST were identified. The interaction between REST and β-TrCP suggested that SCF β-TrCP is the ubiquitin ligase targeting REST for degradation. To investigate the specificity of this binding, we screened 16 F-box proteins as well as two related proteins, CDH1 and CDC20. β-TrCP1 and β-TrCP2 were the only proteins that immunoprecipitated together with endogenous REST (Fig. 1a and data not shown). Interaction between endogenous β-TrCP1 and REST was also observed (Supplementary Fig. 1a).

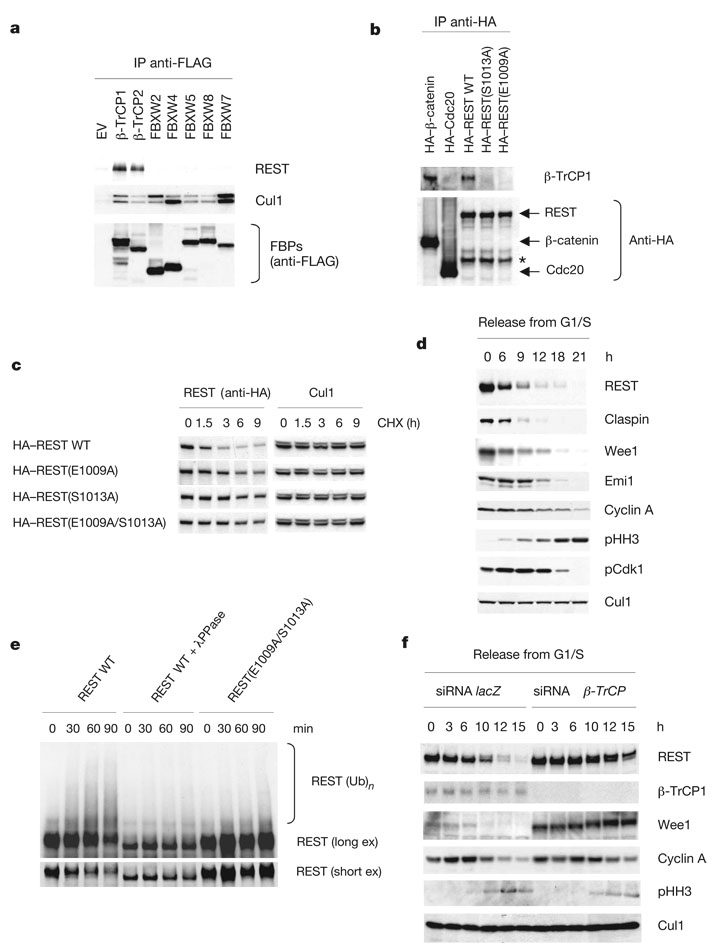

Figure 1. REST is targeted for degradation by SCFβ-TrCP during G2.

a, HEK-293T cells were transfected with empty vector (EV) or the indicated FLAG-tagged F-box protein constructs (FBPs). Cell extracts were immunoprecipitated (IP) with anti-FLAG resin, and immunocomplexes were probed for the indicated proteins. b, The indicated HA-tagged proteins were expressed in HEK-293T cells. Cell extracts were subjected to immunoprecipitation with anti-HA resin followed by immunoblotting. The asterisk indicates a non-specific band. WT, wild type. c, The indicated HA-tagged proteins were expressed in HEK-293T. At 24 h after transfection, cells were treated with cycloheximide (CHX). Cells were collected and proteins were analysed by immunoblotting with an anti-HA antibody (left panels) to detect REST or with an anti-Cul1 antibody (right panels) to show loading normalization. d, HeLa cells were synchronized by a double-thymidine block and released into nocodazole-containing medium. Cells were collected at the indicated times, lysed and immunoblotted. e, β-TrCP-mediated REST ubiquitination is dependent on phosphorylation. HeLa cells were infected with lentiviruses expressing HA-tagged wild-type REST or HA-tagged REST (E1009/S1013A), synchronized in prometaphase and incubated with MG132 during the last 3 h before lysis. Cell extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA resin. Immunoprecipitates were incubated with either λ-protein phosphatase (λPPase) or enzyme buffer before ubiquitination/degradation assays (at 30 °C for the indicated times) in the presence of in vitro transcribed/translated β-TrCP. The bracket marks a ladder of bands corresponding to polyubiquitinated REST detected by immunoblotting. ex, exposure. f, HeLa cells were transfected twice with short interfering RNA (siRNA) molecules to a non-relevant mRNA (lacZ) or to β-TrCP mRNA and then synchronized and analysed as in d.

Most proteins recognized by β-TrCP contain a DSGXXS degron in which the serine residues are phosphorylated, allowing binding to β-TrCP16. REST has a similar motif at the C terminus in which the first serine residue is replaced by glutamic acid, in an analogous manner to other known β-TrCP substrates (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Supplementary Fig. 3 shows that this sequence fits with low energy into the three-dimensional structural space of the β-TrCP substrate-binding surface, similarly to a phospho-peptide corresponding to the degron of β-catenin, a well-characterized substrate of β-TrCP17.

We generated a number of human REST mutants (all with haemagglutinin epitope (HA) tags), in which Glu 1009 and/or Ser 1013 were mutated to Ala (Supplementary Fig. 2b), expressed them in HEK-293T cells, and immunoprecipitated them with anti-HA resin. Whereas wild-type REST efficiently immunoprecipitated endogenous β-TrCP1, the REST(E1009A), REST(S1013A) and REST (E1009A/S1013A) mutants did not (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 1b), showing that Glu 1009 and Ser 1013 are required for binding to β-TrCP. Accordingly, in comparison with wild-type REST, the half-lives of REST mutants were increased in HEK-293T cells (Fig. 1c).

Because SCFβ-TrCP mediates the ubiquitination of several proteins in specific phases of the cell cycle12,15,18–20, we analysed the expression of REST during the cell cycle. When HeLa cells were released from a G1/S block, REST protein levels decreased in G2, at a time when the levels of cyclin A and Emi1, which are both degraded in early mitosis, were still elevated (Fig. 1d). Similar oscillations in REST expression were observed with different synchronization methods and cell types, including HCT116, U-2OS and human diploid IMR-90 fibroblasts (Supplementary Fig. 4a, b and data not shown). The proteasome inhibitor MG132 prevented the disappearance of REST in HeLa and HCT116 cells arrested in prometaphase by a spindle poison (Supplementary Fig. 5a), showing that REST degradation is mediated by the proteasome and that this degradation persists during spindle checkpoint activation. Accordingly, in contrast with wild-type REST, REST(E1009A/S1013A) is stable in prometaphase cells (Supplementary Fig. 6a, b).

MG132-treated prometaphase cells accumulated phosphorylated REST (Supplementary Fig. 5b). Moreover, REST, but not REST (E1009A/S1013A), immunopurified from prometaphase cells was ubiquitinated in vitro in the presence of β-TrCP (but not FBXW8) (Fig. 1e and Supplementary Fig. 5c). Finally, incubation with λ-phosphatase completely inhibited the ubiquitination of wild-type REST (Fig. 1e). These findings indicate that REST phosphorylation is necessary for its ubiquitination.

To further test whether β-TrCP regulates the stability of REST, we used a double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) oligonucleotide that efficiently targets both β-TrCP1 and β-TrCP2 (refs 14, 15, 18) to decrease their expression in HeLa cells. β-TrCP knockdown inhibited the G2-specific degradation of REST (Fig. 1f). Moreover, phosphorylated REST accumulated after β-TrCP silencing (Supplementary Fig. 5b).

Together, the above results demonstrate that β-TrCP-mediated degradation of REST starts in G2, and this event requires the DEGXXS degron in the REST C terminus.

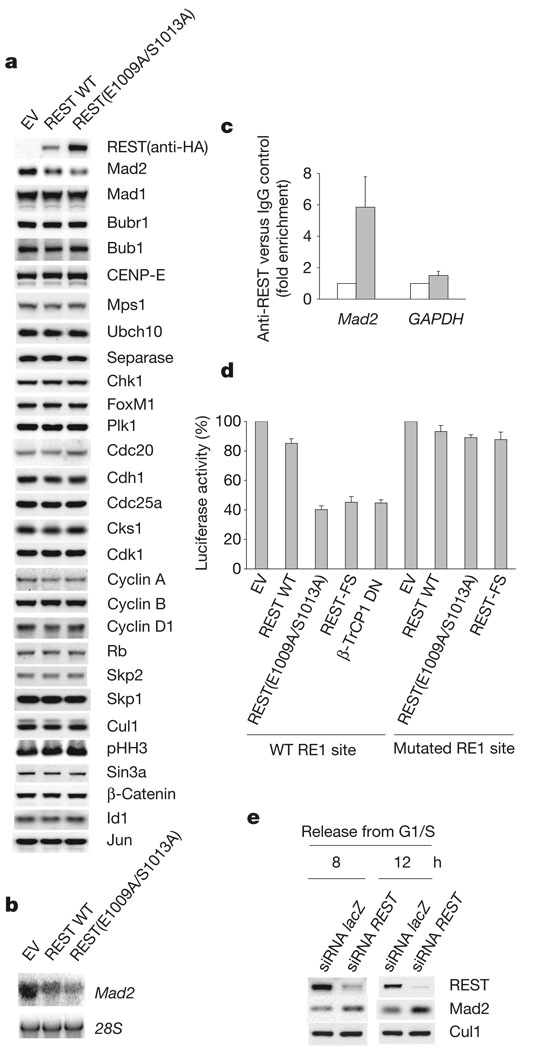

Because REST is a transcriptional repressor, we proposed that its degradation in G2 might be necessary to derepress genes involved in mitosis. We therefore analysed the expression of proteins regulating mitosis and/or cell proliferation in U-2OS cells expressing either wild-type REST or REST(E1009A/S1013A). Prometaphase U-2OS cells showed higher levels of REST(E1009A/S1013A) than wild-type REST(Fig. 2a) as a result of its stabilization (Supplementary Fig. 6a, b). Of the 37 proteins analysed, only the levels of Mad2 were altered in cells expressing REST(E1009A/S1013A) (Fig. 2a, and data not shown). Lower levels of Mad2 were also observed when the stable REST mutant was expressed in IMR-90 fibroblasts (Supplementary Fig. 7) and NIH 3T3 cells (data not shown). Mad2 is a crucial component of the spindle checkpoint, inhibiting the anaphase-promoting complex to prevent sister-chromatid separation until microtubules radiating from the spindle poles have been attached to all kinetochores21. Northern blot analysis showed downregulation of Mad2 mRNA in REST(E1009A/S1013A)-expressing cells (Fig. 2b). Analysis of the Mad2 genomic sequence showed several putative RE1 sites. Chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis confirmed in vivo binding of endogenous REST to the Mad2 promoter (Fig. 2c). In addition, a human Mad2 genomic fragment containing an RE1 site (position 26–46 relative to the transcription start site), but not one containing a deletion in the RE1 site, conferred REST responsiveness to a luciferase reporter after the transient transfection of U-2OS or a IMR-90 cells (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 8). Dominant-negative β-TrCP22, which stabilizes endogenous REST (data not shown), inhibited the activity of the Mad2 promoter-driven luciferase reporter (Fig. 2d). Importantly, depletion of REST in G2 IMR-90 cells induced an increase in Mad2 levels (Fig. 2e).

Figure 2. Mad2 is a transcriptional target of REST.

a, U-2OS cells were infected either with an empty lentivirus (EV) or with lentiviruses expressing HA-tagged wild-type REST or HA-tagged REST(E1009/S1013A). After treatment with nocodazole for 15 h, mitotic cells were harvested and analysed by immunoblotting for the indicated proteins. b, Mad2 mRNA was assessed by northern blotting in U-2OS cells treated as in a. c, Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay with an anti-REST antibody (filled columns) in U-2OS cells. Quantitative real-time PCR amplifications were performed with primers surrounding the RE1 site in the Mad2 promoter. The value given for the amount of PCR product present from ChIP with control IgG (open columns) was set as 1. GAPDH primers were used as a negative control. d, U-2OS cells were transfected with an empty vector (EV), HA-tagged REST proteins or a dominant-negative β-TrCP1 mutant (FLAG–β-TrCP1 DN) together with a luciferase reporter linked to a Mad2 genomic fragment containing either a wild-type (WT) or a mutated RE1 site. Prometaphase cells were collected and the relative luciferase signal was quantified. The value given for luciferase activity in EV-transfected cells was set at 100%. e, IMR-90 cells were transfected twice with siRNA molecules to a non-relevant mRNA (lacZ) or to REST mRNA and synchronized in G2 by release from an aphidicolin block for the indicated durations30. Cells were then lysed and immunoblotted. Where present, error bars represent s.d. (n = 3).

These results indicate that Mad2 is a direct and physiologically relevant transcriptional target of REST. Consistent with this notion, Mad2 expression (both at the mRNA and protein level) is inversely proportional to REST protein levels during the progression of cells through G2 (Supplementary Fig. 4b, c).

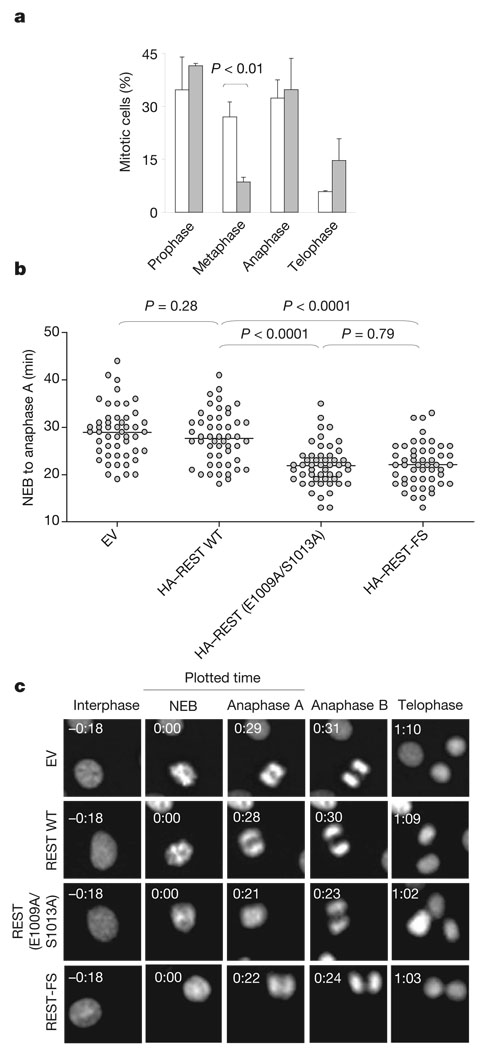

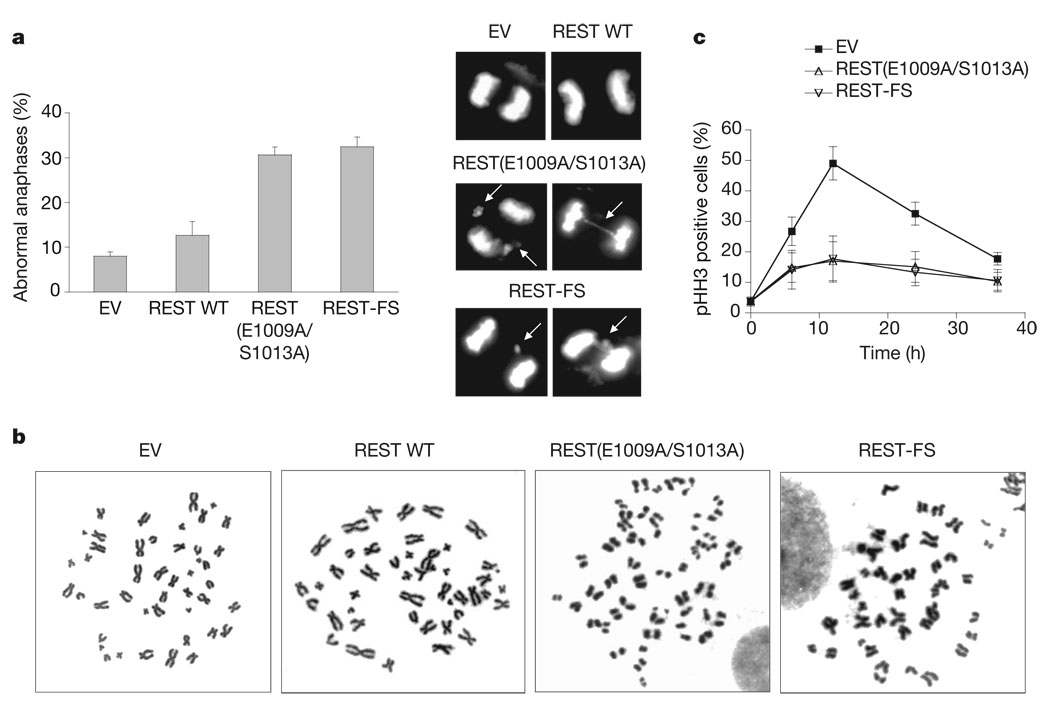

Deletion of a single Mad2 allele in mouse embryonic fibroblasts or human HCT116 cancer cells results in a defective mitotic checkpoint 23. To study whether failure to degrade REST in G2 also affects the spindle checkpoint, we analysed HCT116 cells (which have a relatively stable karyotype) expressing HA-tagged wild-type REST or HA-tagged REST(E1009A/S1013A). As expected, wild-type REST was degraded in G2, whereas REST(E1009A/S1013A) was stable in G2 (Supplementary Fig. 9). Cells expressing REST (E1009A/S1013A) showed a decreased percentage of metaphases (Fig. 3a). Because this effect might have been due to a faster progression through metaphase, we analysed mitotic progression by time-lapse microscopy. The average time from nuclear envelope breakdown to anaphase onset was decreased in cells expressing REST (E1009A/S1013A) in comparison with control cells (Fig. 3b, c and Supplementary Fig. 10). Moreover, expression of the stable REST mutant increased the number of lagging chromosomes and chromosome bridges in anaphase (Fig. 4a) and the appearance of tetraploidy (11/61 versus 0/61 in control cells), as scored in metaphase spreads from two different experiments. More than 8% of cells expressing the stable REST mutant (6/71) displayed prematurely separated sister chromatids, in contrast with 1.4% (1/71) in control cells (Fig. 4b). Finally, cells expressing the stable REST mutant showed a decrease in the mitotic index in the presence of a spindle poison, despite the fact that they entered into mitosis with normal kinetics (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 11), suggesting an increased rate of mitotic slippage and adaptation to the spindle checkpoint.

Figure 3. Failure to degrade REST causes defects in the mitotic checkpoint.

a, HCT116 cells were infected either with an empty lentivirus (EV, open columns) or with a lentivirus expressing REST(E1009/S1013A) (filled columns). At 48 h after infection, cells were fixed and stained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole and an anti-α-tubulin antibody to reveal DNA and the mitotic spindle, respectively. Error bars represent s.d. (n = 3). b, NIH 3T3 cells stably transfected with enhanced green fluorescent protein-labelled histone H2B were infected with an empty lentivirus or with lentiviruses expressing the indicated HA-tagged proteins. The average time from nuclear envelope breakdown (NEB) to anaphase onset was measured by time-lapse microscopy. Each symbol in the scatter plot represents a single cell. c, Representative fluorescence videomicroscopy series from b; numbers in the top left are times (h:min).

Figure 4. Expression of a stable REST mutant or oncogenic REST-FS leads to chromosomal instability.

a, Left: percentage of aberrant anaphases in HCT116 cells infected as in Fig. 3b. Right: representative pictures. Arrows point to lagging chromosomes and chromosome bridges. b, Premature sister-chromatid separation in cells expressing stable REST. Panels show representative metaphase spreads in HCT116 cells infected as in Fig. 3b. c, Nocodazole was added for the indicated durations to HCT116 cells infected as in Fig. 3b. Cells were stained with an anti-phospho-HH3 (pHH3) antibody to quantify their mitotic index. Where present, error bars represent s.d. (n = 3).

These phenotypes indicate that in cells expressing the stable REST mutant, anaphase proceeds faster and in the absence of complete and accurate chromosome–microtubule attachment. Premature anaphase and chromosome aberrations are hallmarks of the defective spindle checkpoint observed in Mad2+/− cells23.

We predicted that REST-FS, an oncogenic frame-shift mutant from a colon cancer cell line11, would be stabilized because it lacks the β-TrCP degron. Indeed, we found that REST-FS did not bind β-TrCP and was stable in G2 HCT116 cells (Supplementary Figs 1b and 12a). Expression of REST-FS in U-2OS cells caused a decrease in Mad2 mRNA and Mad2 protein (Supplementary Fig. 12b, c) and a decrease in the activity of a Mad2 promoter-driven luciferase reporter (Fig. 2d), similarly to the expression of REST(E1009A/S1013A). Finally, the mitotic phenotypes induced by the expression of REST-FS (Fig 3b, c and Fig 4) were indistinguishable from those caused by REST(E1009A/S1013A).

We show here that β-TrCP-mediated degradation of REST in G2 is necessary for the optimal expression of Mad2. Failure to degrade REST produces a deficient spindle checkpoint and consequent chromosome instability. REST is expressed in non-neuronal cells and stem/progenitor neural cells, in which it inhibits neuronal differentiation by blocking the expression of neuron-specific genes2,24. The transition from embryonic stem cell to stem/progenitor neuronal cell requires the proteasome-mediated degradation of REST24. Our study suggests that REST proteolysis must be accurately controlled to avoid subjecting neuronal tissues to cancer risk. In fact, increased levels of REST resulting from overproduction and/or C-terminal truncations, as observed in human neuronal tumours3–7,10, would both inhibit differentiation and generate chromosomal instability, two mechanisms that contribute to tumour development. Although REST has oncogenic properties in neuronal cells, the reduction of REST expression in certain non-neuronal tumours suggests a tumour suppressor role for REST and a function in the neuroendocrine phenotype in some of these lesions11,25. C-terminally truncated REST variants are also observed in non-neuronal tumours8–11. Our study suggests that these stable REST variants may contribute to cell transformation by promoting aneuploidy26 and genetic instability in both neuronal and non-neuronal tissues.

METHODS SUMMARY

Biochemical methods

Extract preparation, immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting were as described previously14,15,18.

Transient transfections and lentivirus-mediated gene transfer

HEK-293T cells were transfected by using calcium phosphate. U-2OS cells were transfected with the use of FuGENE-6 reagent (Roche). For lentivirus-mediated gene transfer, HEK-293T cells were co-transfected with pTRIP-PGK together with packaging vectors. At 48 h after transfection, virus-containing medium was collected and supplemented with 8 µg ml−1 Polybrene (Sigma). Cells were then infected with the viral supernatant for 6 h.

Transcription analyses

RNA was extracted by using the RNeasy Kit (Qiagen). cDNA synthesis was performed with Superscript III (Invitrogen). Quantitative real-time PCR analysis was performed in accordance with standard procedures, using SYBR Green mix (Bio-Rad). Mad2 primer sequences were reported previously27. Control ARPP P0 primers sequences were 5′-GCACTGGAAGTCCAACTACTTC-3′ and 5′-TGAGGTCCTCCTTGGTGAACAC-3′. Northern blotting was performed as described28. 32P-labelled human full-length Mad2 complementary DNA was used as a probe to detect Mad2 mRNA. For luciferase assays, U-2OS cells were transfected in a 4:2:1 ratio with HA-tagged REST constructs, luciferase reporter plasmid (pGL3-Mad2)27 and pCMV-β-galactosidase. Luciferase activity was measured with the Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega), and relative luciferase activities were normalized to lacZ.

Chromatin immunoprecipitations

Chromatin immunoprecipitations were conducted as described previously29. Mad2 primer sequences were as reported previously27. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) primer sequences were 5′-TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTA-3′ and 5′-ACCACAGTCCATGCCATCAC-3′.

Full Methods and any associated references are available in the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

METHODS

Cell culture, synchronization and drug treatments

U-2OS, HCT116, HEK-293T, HeLa and IMR-90 cells were grown, synchronized and treated with drugs as described previously14,15,18.

Purification of β-TrCP interactors

An immunoaffinity/enzymatic assay that enriches for ubiquitinated substrates of F-box proteins, followed by mass spectrometry analysis, was described previously14,15.

Antibodies

Anti-Mad2 and anti-REST antibodies were provided by H. Yu and by G. Mandel, respectively. Commercially available antibodies were as follows: anti-REST-C (Upstate 07-579), anti-Mad2 (BD 610679), anti-Cul1 (Zymed 32-2400), anti-phospho-histone H3 (anti-pHH3; Upstate 06-570), anti-M2 FLAG (Sigma F3165), anti-Cdk1 phosphorylated on Tyr 15 (pCdk1; Santa Cruz sc-7989-R), anti-phospho MPM2 (Upstate 05-368), and anti-α-Tubulin (Zymed 32-2500). All additional antibodies used here were described previously14,15,18.

Vectors

Human REST cDNA was provided by G. Mandel and N. Ballas and subcloned into pcDNA3.1. REST mutants were generated using the QuickChange Site-directed Mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). Enhanced green fluorescent protein-labelled histone H2B cloned into pEGFP-N1 was provided by I. Sanchez. For lentivirus production, both wild-type REST and REST mutants were subcloned into the lentivirus vector pTRIP, which was provided by D. Levy.

Gene silencing by small interfering RNA

siRNA for β-TrCP was described previously14,15,18. A 21-nucleotide siRNA duplex corresponding to a non-relevant gene (lacZ) was used as control.

Indirect immunofluorescence

Cells were plated and cultured on chambered glass tissue-culture slides (BD Falcon) with complete medium. Cells were washed in PBS, fixed and permeabilized in 100% methanol at −20 °C for 10 min and then incubated with the primary antibodies for 1 h at 25 °C in 0.5% Tween 20 in PBS (0.5% TBST). Slides were washed three times in 0.5% TBST for 5 min and incubated with secondary antibodies diluted 1:1,000. 4,6-Diamidino-2-phenylindole (Molecular Probes) was included to reveal nuclei. Slides were washed in PBS and subsequently mounted with Aqua Poly/Mount (Polysciences). Images were acquired with a Nikon Eclipse E800 fluorescence deconvolution microscope.

Live cell imaging

Live cell imaging was performed as described previously27.

Chromosome analysis

Chromosome analysis of cells in metaphase was performed as described23.

In vitro ubiquitination/degradation assay

HA-tagged wild-type REST or HA-tagged REST(E1009/S1013A) were immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibody from HeLa cells infected with lentiviruses expressing HA-tagged wild-type REST or HA-tagged REST(E1009/S1013A), treated with nocodazole for 15 h and with MG132 for the last 3 h. Immunoprecipitates were incubated with either λ phosphatase or phosphatase buffer for 1 h at 30 °C. In vitro ubiquitination/degradation assays were performed by adding to agarose beads 10 µl containing 50mM Tris-HCl pH 7.6, 5mM MgCl2, 0.6mM dithiothreitol, 2mM ATP, 1.5 ng µl−1 E1 (Boston Biochem), 10 ng µl−1 Ubc3, 10 ng µl−1 Ubc5, 2.5 µg µl−1 ubiquitin (Sigma), 1 µM ubiquitin aldehyde and 2 µl of unlabelled in vitro transcribed/translated β-TrCP1 or FBXW8. The reactions were then incubated at 30 °C for the indicated durations and analysed by immunoblotting with an anti-HA antibody.

Interaction models

All-atom models of all peptides were derived from the PDB structure of β-TrCP bound to β-catenin (PDB: 1p22) using a stochastic global optimization in internal coordinates with pseudo-brownian and collective probability-biased random moves as implemented in the ICM 3.0 program (Molsoft; ICM software manual, Version 3.0, 2004). The energy function used to calculate the interaction energy of phosphoserine and mutations with β-TrCP uses ECEPP/3 force-field parameters31:

in which _E_hb is an original ECEPP/3 energy function. The electrostatics term _E_el was calculated by using the boundary element method with ECEPP/3 atomic charges and an internal dielectric constant of 4.0 (ref. 32). The same energy function was used to assess 54 crystallographically resolved phosphoserines containing only one contacting arginine and bound at protein interaction sites from the Protein Data Bank. The mean and one standard deviation of the range of energy values is shown by the vertical green line in Supplementary Fig. 3.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank V. D’Angiolella, S. Ge, L. Gnatovskiy, J. Staveroski and N. E. Sherman for their contributions to this work; P. Jallepalli and J. Skaar for suggestions and/or critically reading the manuscript; S. Elledge and T. Westbrook for communicating results before publication; and the T. C. Hsu Molecular Cytogenics Core. M.P. is grateful to T. M. Thor for continuous support. D.G. is grateful to R. Dolce and L. Guardavaccaro. This work was supported by an Emerald Foundation grant to D.G., a fellowship from Provincia di Benevento to D.G., American–Italian Cancer Foundation fellowships to D.G., N.V.D. and A.P., and grants from the National Institutes of Health to S.C. and M.P.

Footnotes

References

- 1.Ballas N, Mandel G. The many faces of REST oversee epigenetic programming of neuronal genes. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2005;15:500–506. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ooi L, Wood IC. Chromatin crosstalk in development and disease: lessons from REST. Nature Rev. Genet. 2007;8:544–554. doi: 10.1038/nrg2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Su X, et al. Abnormal expression of REST/NRSF and Myc in neural stem/progenitor cells causes cerebellar tumors by blocking neuronal differentiation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006;26:1666–1678. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.5.1666-1678.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fuller GN, et al. Many human medulloblastoma tumors overexpress repressor element-1 silencing transcription (REST)/neuron-restrictive silencer factor, which can be functionally countered by REST-VP16. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2005;4:343–349. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-04-0228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Higashino K, Narita T, Taga T, Ohta S, Takeuchi Y. Malignant rhabdoid tumor shows a unique neural differentiation as distinct from neuroblastoma. Cancer Sci. 2003;94:37–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2003.tb01349.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lawinger P, et al. The neuronal repressor REST/NRSF is an essential regulator in medulloblastoma cells. Nature Med. 2000;6:826–831. doi: 10.1038/77565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nishimura E, Sasaki K, Maruyama K, Tsukada T, Yamaguchi K. Decrease in neuron-restrictive silencer factor (NRSF) mRNA levels during differentiation of cultured neuroblastoma cells. Neurosci. Lett. 1996;211:101–104. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(96)12722-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gurrola-Diaz C, Lacroix J, Dihlmann S, Becker CM, von Knebel Doeberitz M. Reduced expression of the neuron restrictive silencer factor permits transcription of glycine receptor α1 subunit in small-cell lung cancer cells. Oncogene. 2003;22:5636–5645. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neumann SB, et al. Relaxation of glycine receptor and onconeural gene transcription control in NRSF deficient small cell lung cancer cell lines. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 2004;120:173–181. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2003.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coulson JM, Edgson JL, Woll PJ, Quinn JP. A splice variant of the neuron-restrictive silencer factor repressor is expressed in small cell lung cancer: a potential role in derepression of neuroendocrine genes and a useful clinical marker. Cancer Res. 2000;60:1840–1844. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Westbrook TF, et al. A genetic screen for candidate tumor suppressors identifies REST. Cell. 2005;121:837–848. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guardavaccaro D, Pagano M. Stabilizers and destabilizers controlling cell cycle oscillators. Mol. Cell. 2006;22:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jin J, et al. Systematic analysis and nomenclature of mammalian F-box proteins. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2573–2580. doi: 10.1101/gad.1255304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dorrello NV, et al. S6K1- and βTRCP-mediated degradation of PDCD4 promotes protein translation and cell growth. Science. 2006;314:467–471. doi: 10.1126/science.1130276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peschiaroli A, et al. SCFβTrCP-mediated degradation of Claspin regulates recovery from the DNA replication checkpoint response. Mol. Cell. 2006;23:319–329. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cardozo T, Pagano M. The SCF ubiquitin ligase: insights into a molecular machine. Nature Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004;5:739–751. doi: 10.1038/nrm1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu G, et al. Structure of a β-TrCP1-Skp1-β-catenin complex: destruction motif binding and lysine specificity of the SCFβ-TrCP1 ubiquitin ligase. Mol. Cell. 2003;11:1445–1456. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00234-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guardavaccaro D, et al. Control of meiotic and mitotic progression by the F box protein β-Trcp1 in vivo. Dev. Cell. 2003;4:799–812. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00154-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Busino L, et al. Degradation of Cdc25A by β-TrCP during S phase and in response to DNA damage. Nature. 2003;426:87–91. doi: 10.1038/nature02082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watanabe N, et al. Ubiquitination of somatic Wee1 by SCFβTrcp is required for mitosis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:4419–4424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307700101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nasmyth K. How do so few control so many? Cell. 2005;120:739–746. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Latres E, Chiaur J, Pagano M. The human F box protein β-Trcp associates with the Cul1/Skp1 complex and regulates the stability of β-catenin. Oncogene. 1999;18:849–854. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Michel LS, et al. MAD2 haplo-insufficiency causes premature anaphase and chromosome instability in mammalian cells. Nature. 2001;409:355–359. doi: 10.1038/35053094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ballas N, Grunseich C, Lu DD, Speh JC, Mandel G. REST and its corepressors mediate plasticity of neuronal gene chromatin throughout neurogenesis. Cell. 2005;121:645–657. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Majumder S. REST in good times and bad: roles in tumor suppressor and oncogenic activities. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:1929–1935. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.17.2982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pellman D. Aneuploidy and cancer. Nature. 2007;446:38–39. doi: 10.1038/446038a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hernando E, et al. Rb inactivation promotes genomic instability by uncoupling cell cycle progression from mitotic control. Nature. 2004;430:797–802. doi: 10.1038/nature02820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kudo Y, et al. Role of F-box protein βTrcp1 in mammary gland development and tumorigenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:8184–8194. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.18.8184-8194.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Busino L, et al. SCFFbxl3 controls the oscillation of the circadian clock by directing the degradation of cryptochrome proteins. Science. 2007;316:900–904. doi: 10.1126/science.1141194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Amador V, Ge S, Santamaria P, Guardavaccaro D, Pagano M. APC/CCdc20 controls the ubiquitin-mediated degradation of p21 in prometaphase. Mol. Cell. 2000;27:462–473. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nemethy G, et al. Energy parameters in polypeptides. 10. Improved geometric parameters and nonbonded interactions for use in the ECEPP/3 algorithm with application to proline-containing peptides. J. Phys. Chem. 1992;96:6472–6484. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Totrov M, Abagyan R. Rapid boundary element solvation electrostatics calculations in folding simulations: successful folding of a 23-residue peptide. Biopolymers. 2001;60:124–133. doi: 10.1002/1097-0282(2001)60:2<124::AID-BIP1008>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.