A sensitized mutagenesis screen identifies Gli3 as a modifier of Sox10 neurocristopathy (original) (raw)

Abstract

Haploinsufficiency for the transcription factor SOX10 is associated with the pigmentary deficiencies of Waardenburg syndrome (WS) and is modeled in Sox10 haploinsufficient mice (Sox10 LacZ/+). As genetic background affects WS severity in both humans and mice, we established an N_-ethyl-N_-nitrosourea (ENU) mutagenesis screen to identify modifiers that increase the phenotypic severity of Sox10 LacZ/+ mice. Analysis of 230 pedigrees identified three modifiers, named modifier of Sox10 neurocristopathies (Mos1, Mos2 and Mos3). Linkage analysis confirmed their locations on mouse chromosomes 13, 4 and 3, respectively, within regions distinct from previously identified WS loci. Positional candidate analysis of Mos1 identified a truncation mutation in a hedgehog(HH)-signaling mediator, GLI-Kruppel family member 3 (Gli3). Complementation tests using a second allele of Gli3 (Gli3 Xt-J) confirmed that a null mutation of Gli3 causes the increased hypopigmentation in Sox10 LacZ/+;Gli3 Mos1/+ double heterozygotes. Early melanoblast markers (Mitf, Sox10, Dct, and Si) are reduced in Gli3 Mos1/Mos1 embryos, indicating that loss of GLI3 signaling disrupts melanoblast specification. In contrast, mice expressing only the GLI3 repressor have normal melanoblast specification, indicating that the full-length GLI3 activator is not required for specification of neural crest to the melanocyte lineage. This study demonstrates the feasibility of sensitized screens to identify disease modifier loci and implicates GLI3 and other HH signaling components as modifiers of human neurocristopathies.

INTRODUCTION

Waardenburg syndrome (WS) describes a specific group of neurocristopathies whose phenotypes are primarily caused by melanocyte deficiencies. The features of WS include skin hypopigmentation (leukoderma), pigmentation defects of the choroid and iris, and deafness from loss of inner ear melanocytes. The presence of additional phenotypic anomalies results in four clinically distinct WS types that have been associated with mutations in at least six genes essential for the development of the neural crest (NC), a population of pluripotent cells that differentiates into many functionally diverse cell types. The identified WS genes include paired box gene 3 (PAX3), microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF), snail homolog 2 (SNAI2), endothelin-3 (EDN3), endothelin B receptor (EDNRB), and Sry-like HMG box 10 (SOX10) (1–9). In particular, mutations in SOX10 have been identified in type II WS (WS2) and type IV WS (WS4), which combine features of WS with absence of enteric neurons (aganglionosis) that is characteristic of Hirschsprung disease (HSCR; OMIM 142623).

Sox10 is an HMG-box containing transcription factor that is expressed during embryonic development in pre-migratory NC and in a subset of migrating NC cells including those that give rise to the glial and melanocyte lineages (reviewed in 10). The melanocyte precursor cells, melanoblasts, express Mitf as they migrate along a dorso-lateral route away from the neural tube. Further differentiation is marked by the subsequent expression of the melanosomal protein silver (Si, also known as Pmel17) and the melanogenic enzyme dopachrome tautomerase (Dct) as melanoblasts proceed along their route to the ectoderm where a subset of these colonize the basal epidermis and hair follicles and are readily visible as terminally differentiated melanocytes due to their pigment production (reviewed in 11). Because of its role in multiple NC lineages, Sox10 is essential for development, and mice carrying heterozygous Sox10 mutations have NC defects resembling those of WS4, including hypopigmentation and aganglionic megacolon (9,12,13). Similar to humans with WS, the mouse models of WS (14) show phenotypic variability among individuals with the same mutation. Together with WS patients where no mutation has been identified, this phenotypic complexity suggests that additional WS loci remain to be discovered. Mice with Sox10 mutations offer a unique tool to identify these additional WS loci and explain their mode of action.

In this study we designed a sensitized ENU modifier screen to identify loci that increase the NC defects, specifically white spotting (hypopigmentation), associated with Sox10 haploinsufficiency. We identified three Sox10 modifier loci that did not map to known WS loci. At one locus, Mos1, a truncation mutation in the transcription factor GLI-Kruppel family member 3 (Gli3) was responsible for increased hypopigmentation when present in combination with Sox10 haploinsufficiency. Mos1 homozygous embryos show a defect in melanoblast specification, a phenotype that is not recapitulated in embryos expressing a C-terminally truncated form of GLI3 that acts as a repressor. This suggests that the full-length form of GLI3 that acts as a transcriptional activator is not required for melanoblast development. This study demonstrates the feasibility of this sensitized ENU screen to identify modifier loci of Sox10, reveals a role for Gli3 in melanocyte development, and implicates GLI3 and other hedgehog (HH) signaling components as modifiers of WS.

RESULTS

A sensitized mutagenesis screen to identify modifiers of SOX10

A breeding strategy was designed to identify ENU-induced mutations that modify the severity of hypopigmentation in Sox10 LacZ/+ mice (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1). BALB/cJ male mice were given 3-weekly ENU injections, allowed to recover fertility, and then mated with C57BL/6J females to generate first generation (G1) offspring. G1 males were subsequently mated with Sox10 tm1Weg/+ heterozygous females (13), herein referred to as Sox10 LacZ/+, because they contain a targeted disruption of the endogenous Sox10 locus that drives expression of a β-galactosidase reporter gene from the Sox10 promoter and predisposes the mice to NC defects. Second generation (G2) offspring were then examined for increased severity of neurocristopathies in Sox10 LacZ/+ mice, as measured by increased hypopigmentation.

Incorporation of two different inbred strains in this screen made efficient mapping of the BALB/cJ mutagenized allele possible in subsequent crosses to C57BL/6J. Since genetic background could affect the hypopigmentation of the Sox10 LacZ/+ animals, we performed a control-cross in which non-ENU-treated BALB/cJ males were substituted for the ENU-treated BALB/cJ males. For these and all subsequent crosses, the extent of ventral hypopigmentation was scored according to a standardized scale (0–4), with 0 representing no hypopigmentation and 4 representing the most severe ventral hypopigmentation (Supplementary Material, Fig. S2). The control-cross demonstrated minimal variation in hypopigmentation among Sox10 LacZ/+ G2 offspring on a BALB/cJ; C57BL/6J mixed genetic background. The control G2 offspring (N = 111) received ventral hypopigmentation scores of 0 (79%) or 1 (21%) and dorsal hypopigmentation was never observed. These results showed that genetic background effects from allelic variance between BALB/cJ and C57BL6/J would not interfere with identification of novel, ENU-induced gene mutations affecting pigmentation.

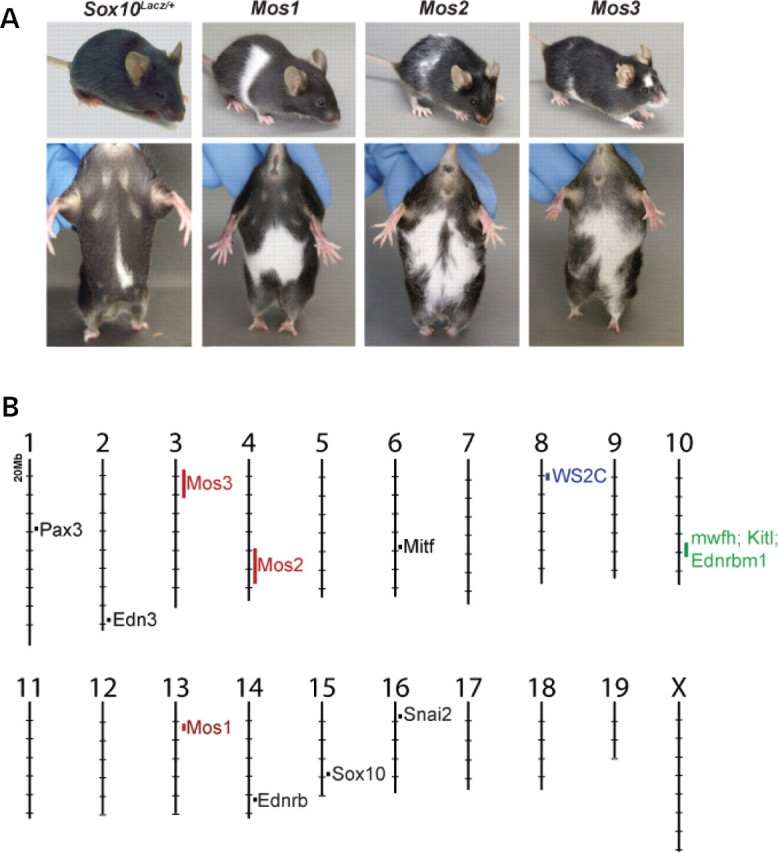

In total, 230 G1 male offspring were generated and at least three litters of G2 offspring from each G1 male were screened for increased hypopigmentation. Seven G1 pedigrees produced one or more Sox10 LacZ/+ G2 offspring with increased ventral hypopigmentation (score >2) accompanied by dorsal hypopigmentation, neither of which was observed in the control cross. In three of these seven G1 pedigrees the observed phenotype was reproducible in subsequent generations, indicating a heritable, mendelian phenotype. These three loci were named modifier of Sox10 1, 2 and 3 (Mos1, Mos2, and Mos3) (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

(A) Three hypopigmentation phenotypes, Mos1, Mos2, and Mos3, were identified in an ENU screen that increase the severity of hypopigmentation in Sox10 LacZ/+ mice. Sox10 LacZ/+;Mos1/+ double heterozygote, Mos2/+ heterozygotes, and Sox10 LacZ/+;Mos3/+ double heterozygote individuals are shown after several generations of outcrossing to C57BL/6J. (B) The murine genomic locations of Mos1, 2, 3 map independently from previously identified WS loci. The locations of Mos1, Mos2, and Mos3 (red) are indicated on the mouse physical map relative to the locations of cloned WS genes (black), a regions of conserved synteny for a human WS modifier (WS2C in blue) (61), and a modifier of mouse Sox10 white forelock hypopigmentation (mwfh in green) (62) which overlaps modifiers of mouse Ednrb S hypopigmentation (Kitl and Ednrbm1 in green) (63).

Mos1, Mos2 and Mos3 do not map to previously known WS loci

To determine if Mos1, 2, and 3 are due to mutations in genes previously attributed to WS, we mapped these loci. In each pedigree, linkage analysis using a whole genome SNP or SSLP panel was used to test for BALB/cJ alleles that associated with the dominant increase in Sox10 LacZ/+ hypopigmentation. For mapping Mos1, nine mice were used for an initial genome scan (six affected Sox10 LacZ/+;Mos1/+ mice plus three obligate Mos1/+ heterozygous carriers). Genotyping of 220 SNPs with distinct alleles in C57BL/6J and BALB/cJ identified a 20 Mb region of proximal mouse Chr 13 where all nine animals had inherited the BALB/cJ allele from the affected founder animal, providing evidence for linkage to markers in this region (0/9 recombinant; P < 0.01).

A similar mapping strategy was used to localize Mos2 and Mos3 to Chrs 4 and 3, respectively. For Mos2, we detected linkage to Chr 4 in a genome scan utilizing 91 SSLP markers to genotype eight affected animals. Subsequent genotyping of affected animals (N = 31) in this region localized Mos2 to 35 Mb region of Chr 4 flanked by markers D4Mit9 (1/31 recombinant; P < 0.0001) and D4Mit203 (8/31 recombinant; P < 0.01). For Mos3, genotyping 408 informative SNPs in five affected animals revealed weak linkage to two regions of the genome. Subsequent genotyping of SSLPs spanning those regions in additional affected animals (N = 32) confirmed linkage to a 20 Mb region of Chr 3 flanked by markers D3Mit178 (2/32 recombinant; P < 0.001) and D3Mit65 (3/32 recombinant; P < 0.0001). The genomic locations of Mos1, Mos2 and Mos3 did not overlap with orthologs of WS genes (Fig. 1B), suggesting they are potentially novel WS modifier loci.

Mos1 increases the severity of hypopigmentation in Sox10 Lacz/+ mice

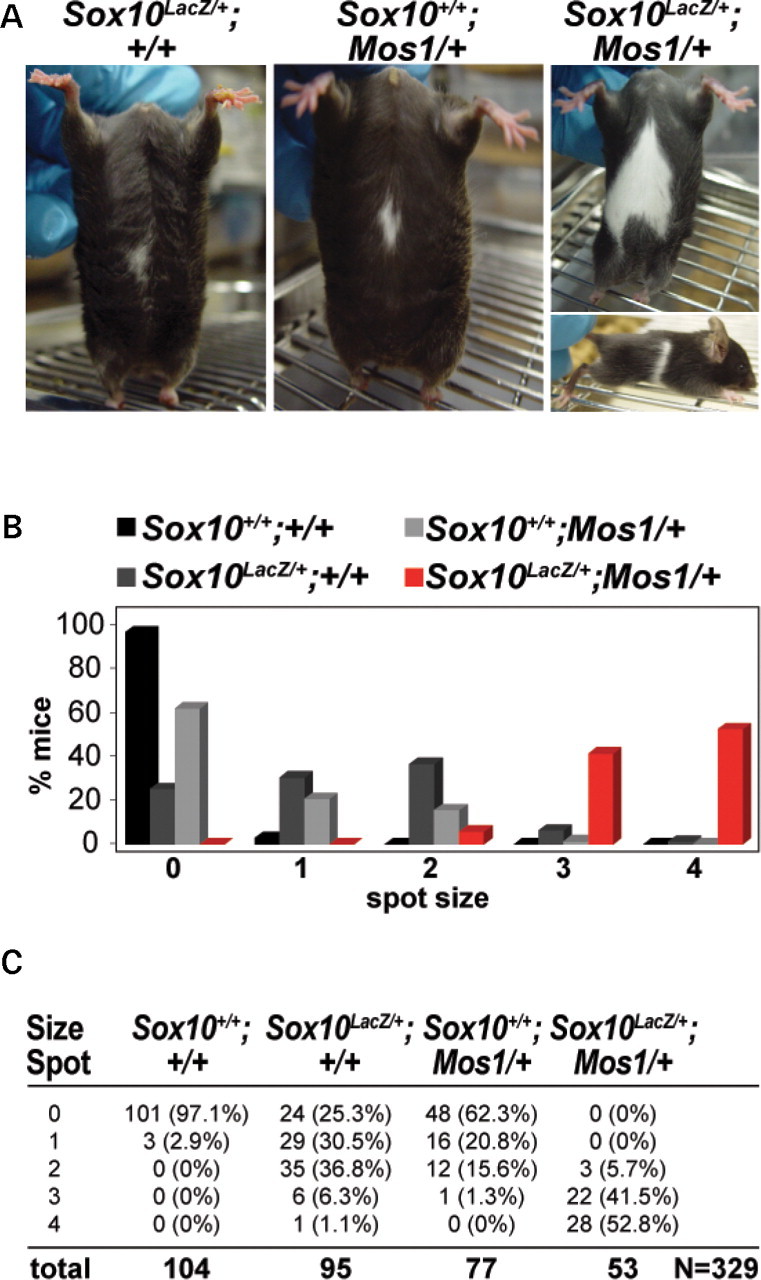

Sox10 LacZ/+;Mos1/+ affected mice exhibited severe ventral hypopigmentation that often extended onto the dorsal surface forming a belt in the lumbar region (Fig. 2A). To confirm that Mos1 exacerbated the NC defects in Sox10 LacZ/+ mice, the penetrance and expressivity of Mos1 alone and in conjunction with Sox10 LacZ/+ was analyzed after breeding the Mos1/+ founder onto a C57BL/6J background (Fig. 2B and C). Analysis of G3 and G4 offspring showed that with respect to hypopigmentation, Mos1 alone acts as a semidominant mutation that is not fully penetrant. A portion (37.7%) of heterozygous Mos1/+ mice exhibited ventral hypopigmentation ranging in size from 1 to 3 (Fig. 2). Double heterozygous Sox10 LacZ/+;Mos1/+ mice exhibited a significant, synergistic increase in hypopigmentation compared with either single heterozygous Mos1/+ or single heterozygous Sox10 LacZ/+ mice (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2). Unlike the majority (75.8%) of Sox10 LacZ/+ heterozygotes, minimal hypopigmentation (0–1) was not seen in any double heterozygous mice. Ventral hypopigmentation that extended over the dorsal surface to form a belt was seen in 17% of Sox10 LacZ/+;Mos1/+ mice, but was never observed in Mos1/+ mice or in Sox10 LacZ/+ mice. These results indicate that the ENU-induced mutation Mos1 enhances the melanocyte defects of Sox10 LacZ/+ mice, acting in synergy with Sox10 haploinsufficiency to produce more severe NC abnormalities.

Figure 2.

Mos1 increases hypopigmentation in Sox10 LacZ heterozygous mice. (A) Heterozygous Sox10 LacZ/+ mice display a small region of ventral hypopigmentation (left) similar to that observed in heterozygous Mos1/+ mice (middle). Double heterozygous Sox10 LacZ/+; Mos1/+ mice exhibit extensive hypopigmentation that frequently extends dorsally as a partial belt (right). (B, C) Quantitative data for the extent of ventral hypopigmentation in each of four genotype classes including wild-type (Sox10+/+;Mos1/+), Sox10 LacZ heterozygotes (Sox10 LacZ/+;Mos1+/+), Mos1 heterozygotes (Sox10+/+;Mos1/+), and Sox10;Mos1 double heterozygotes (Sox10 LacZ/+;Mos1/+). (B) shows a graphical representation of the data, and (C) shows the total numbers and percentages within each genotype/phenotype class (total N = 329).

Mos1 is a novel, nonsense mutation of Gli3

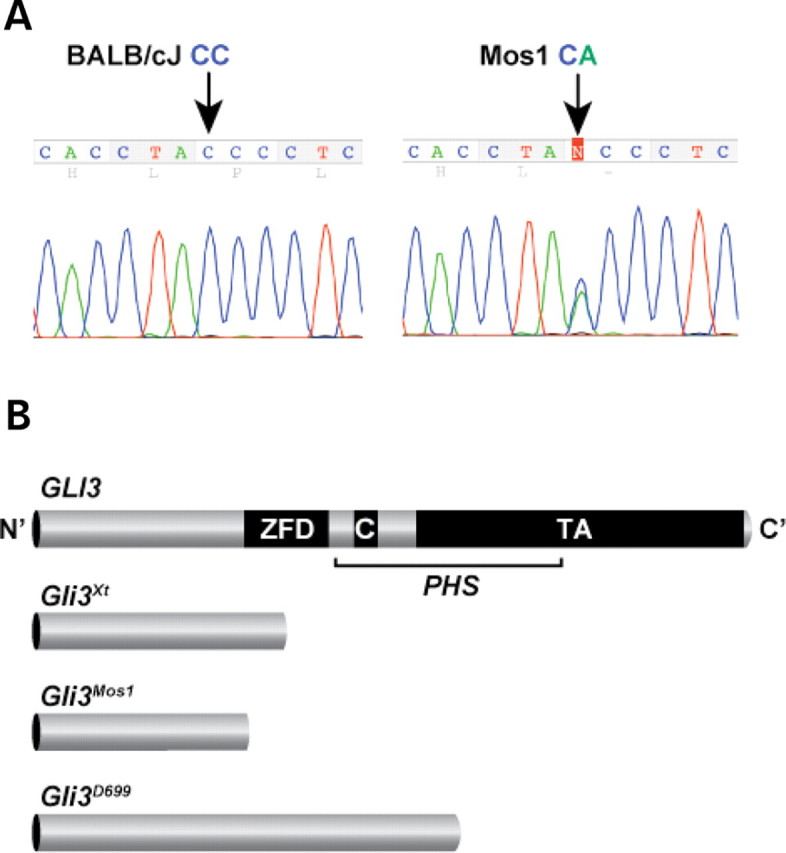

Because 95% (84/88) of Mos1/+ animals had limb defects resembling the semidominant polydactyly previously identified in Extratoes (Gli3 Xt) (15,16), a classic mouse mutant located on Chr 13, we assessed if the Gli3 transcription factor was mutated in Mos1 animals. Genomic DNA from an affected Mos1/+ mouse was analyzed by direct sequencing of all coding exons and intron/exon junctions of Gli3 and compared with sequences of BALB/cJ and C57BL6/J control samples. A single sequence variation was identified in which Mos1 DNA differed from the parental DNA at a single nucleotide in exon 8 (Fig. 3A). The Mos1 allele carried a nucleotide substitution (1148C>A) predicted to replace Tyr350 with a stop codon (Tyr350Stop; Y350X). Using a real-time PCR genotyping assay, we confirmed that this mutation was not detected in BALB/cJ or C57BL/6J control DNAs and consistently segregated with the Mos1 phenotype in 100% of animals tested (N = 130). The location of the Gli3 Mos1 nonsense mutation is upstream of the zinc-finger binding domain, suggesting it would disrupt both the activator and repressor forms of GLI3 (Fig. 3B). This is supported by comparison with two other Gli3 mouse alleles, Gli3 Xt-J and Gli3 D699, and to published human GLI3 mutations in Pallister-Hall syndrome (PHS, OMIM 146510) (17) and Greig cephalopolysyndactyly syndrome (GCPS, OMIM 175700) (18). Comparison shows that Gli3 Mos1 is most similar to Gli3 Xt-J and to GCPS patients with deletions, translocations and point mutations within or upstream of the zinc-finger binding domain (19). Therefore, we propose that Gli3 Mos1 acts as a loss of function allele.

Figure 3.

A nucleotide substitution in Mos1 lies in the N-terminal region of the Gli3 coding sequence. (A) Sequencing of BALB/cJ control and Mos1 heterozygote genomic DNA reveals a C to A substitution at nucleotide position 1148 (arrows) resulting in a nonsense mutation at codon 350 (Tyr350Stop) in the Mos1 allele. The heterozygous Mos1 trace shown contains both C (wild-type sequence of BALB/cJ) and A (mutant sequence of Mos1) at position 1148. (B) Graphic representation of full-length GLI3 protein and 3 truncated proteins resulting from mutant mouse alleles of Gli3. The zinc finger domain (ZFD) (34) and proteolytic cleavage site (C) (26) are indicated along with a region of the protein important for transactivation (TA) that spans several fragments independently shown to function in transactivation (64–66). While the Gli3 Xt-J allele results in a truncated protein that lacks the full ZFD and is a loss of function allele, Gli3 D699 retains the ZFD, and thus functions as a transcriptional repressor. Mutations in the middle third of the human GLI3 gene (bracketed) are predicted to produce truncated functional repressor proteins causing Pallister-Hall syndrome (PHS). The location of the Mos1 mutation would result in a truncated protein lacking the ZFD, and is predicted to be a loss of function allele similar to Gli3 Xt-J, and also to human Greig cephalopolysyndactyly, which is caused by mutations in the human gene that fall outside the bracketed PHS region (19).

Analysis of Gli3 Xt-J confirms that Mos1 phenotypes result from mutation of Gli3

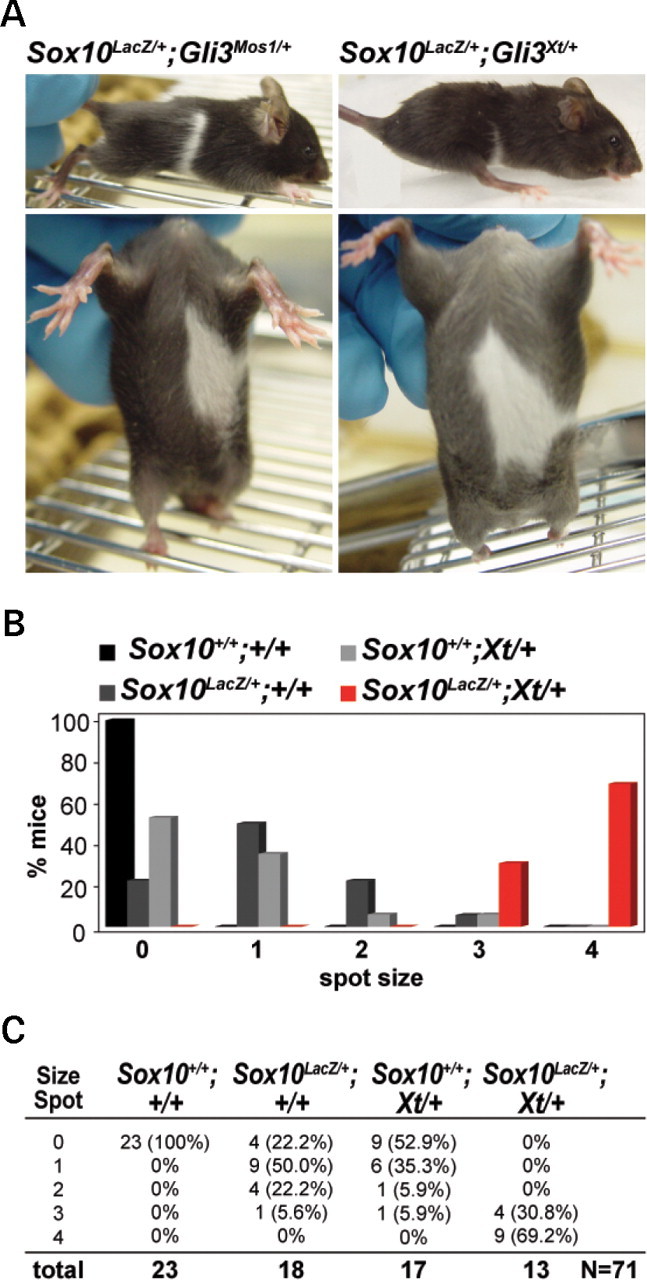

The Gli3 Xt-J allele of Extratoes is a deletion that results in phenotypes similar to those in human GLI3-associated disorders, including craniofacial defects, brain abnormalities and polydactyly (20). Gli3 Xt-J/Xt-J homozygotes die in utero or at birth with gross polydactyly, multiple craniofacial defects, and exencephaly while Gli3 Xt-J heterozygotes are viable but exhibit an enlarged interfrontal bone and preaxial polydactyly. To determine whether the ENU-induced mutation in Gli3 causes the Mos1 phenotype, several analyses were performed to compare the Mos1 phenotype with the Gli3 Xt-J phenotype. First, to examine if Gli3 Mos1/Mos1 homozygotes show embryonic lethality similar to that reported for Gli3 Xt-J/Xt-J, Gli3 Mos1/+ mutant mice were intercrossed and genotype classes were examined at weaning. Of 24 progeny recovered at weaning, no homozygotes were identified, indicating that the Gli3 Mos1 mutation is lethal in homozygotes (0/24 offspring; P < 0.005). Next, allelism was assessed by genotyping the viable offspring from a complementation cross between mice heterozygous for each allele (Gli3 Mos1/+ X Gli3 Xt-J/+). Gli3 Mos1/Gli3 Xt-J compound heterozygotes were never observed at weaning (0/32 offspring; P < 0.01), confirming that Gli3 Mos1 and Gli3 Xt-J are allelic. Finally, heterozygous Gli3 Xt-J/+ mice were mated with Sox10 LacZ/+ mice, and offspring of each genotype class was analyzed for hypopigmentation. Similar to Sox10 LacZ/+;Gli3 Mos1/+ mice, Sox10 LacZ/+;Gli3 Xt-J/+ double heterozygous mice showed a significant increase in the penetrance and severity of hypopigmentation compared with Gli3 Xt-J/+ or Sox10 LacZ/+ heterozygous animals (Fig. 4). Taken together these results show that Gli3 is functionally disrupted in Mos1 mice causing the increased hypopigmentation observed in Sox10 LacZ/+;Gli3 Mos1/+ mice.

Figure 4.

The Gli3 Xt-J allele increases hypopigmentation in Sox10 LacZ heterozygous mice similar to the ENU mutation Mos1, showing that Mos1 is a Gli3 allelic variant. (A) Double heterozygous Sox10 LacZ/+;Gli3 Xt-J/+ mice show enhanced ventral and dorsal hypopigmentation (right) very similar to Sox10 LacZ/+;Mos1/+ mice (left). (B, C) Representative data for ventral hypopigmentation phenotypes for each four genotype classes including wild-type (Sox10+/+;Gli3 +/+), Sox10 LacZ heterozygous mutants (Sox10 LacZ/+;Gli3 +/+), Gli3 Xt-J heterozygous mutants (Sox10+/+;Gli3 Xt-J/+), and double heterozygotes (Sox10 LacZ/+;Gli3 Xt-J/+). (B) Shows a graphical representation of the data, and (C) shows the total numbers and percentages within each genotype/phenotype class (total N = 71).

Gli3 deficiency disrupts development of Sox10 _LacZ_-expressing cells

To further assess the effects of the Gli3 Mos1 mutation as a modifier of NC defects, Sox10 LacZ/+;Gli3 Mos1/+ mice were crossed to either Sox10 LacZ/+;Gli3 Mos1/+ or Gli3 Mos1/+ mice, and embryos were collected for morphological and histological analyses. At E11.5, we observed craniofacial anomalies including microphthalmia and malformation of the diencephalon and mesencephalon in Sox10 LacZ/+;Gli3 Mos1/Mos1 embryos (Fig. 5). These phenotypes are consistent with those in Sox10 LacZ/+ ;Gli3 Xt-J/Xt-J embryos and what has been previously described for Gli3 Xt-J/Xt-J embryos (15). The patterning of the Sox10 LacZ_-expressing dorsal root ganglia (DRG), sympathetic ganglia and cranial ganglia, visualized by LacZ staining, appeared unaffected in Sox10 LacZ/+;Gli3_ Mos1/Mos1 embryos as compared with Sox10 LacZ/+ control embryos (Fig. 5). In contrast, there was a striking reduction in the number of Sox10 LacZ -expressing melanoblasts within the medial lateral trunk of Sox10 LacZ/+;Gli3 Mos1/Mos1 embryos (Fig. 5D–I). Notably, in regions lacking Sox10 _LacZ_-expressing melanoblasts, there were ectopically located Sox10 LacZ_-expressing cells positioned dorsal to the DRG that were larger than Sox10 LacZ_-expressing melanoblasts (Fig. 5E and H, arrowheads). Sox10 LacZ/+;Gli3 Xt-J/Xt-J mutant embryos also exhibited reduced Sox10 _LacZ_-expressing melanoblasts and large ectopic Sox10 _LacZ_-expressing cells in their trunks, confirming that these phenotypes resulted from GLI3 deficiency (Fig. 5F and I).

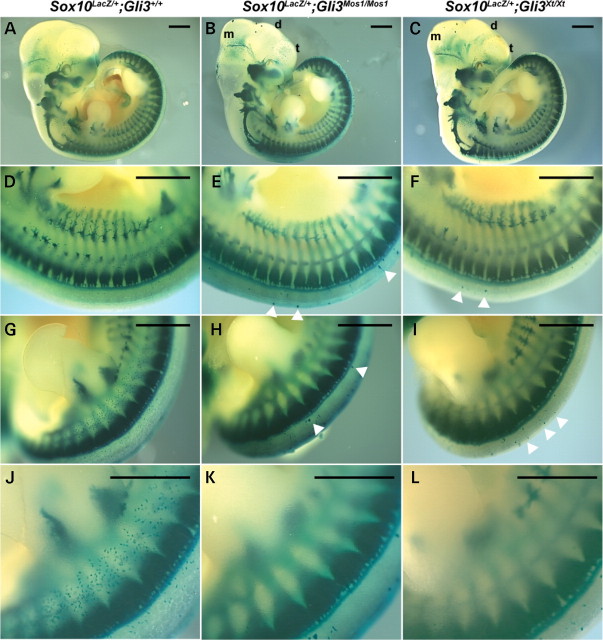

Figure 5.

Sox10 LacZ expression in Gli3 Mos1/Mos1 embryos reveals reduced melanoblasts and ectopic Sox10 LacZ_-expressing cells. Sox10 LacZ/+;Gli3 +/+ (A, D, G, J), Sox10 LacZ/+;Gli3 Mos1/Mos1 (B, E, H, K), and Sox10 LacZ/+;Gli3 Xt-J/Xt-J (C, F, I, L) embryos at E11.5 after X-gal staining. Shown are lateral (A –C) views of E11.5 embryos and the corresponding trunk (D–F) and hind limb regions (G–L). Microphthalmia, as well as malformation of the mesencephalon (m), diencephalon (d) and telencephalon (t) are visible in Sox10 LacZ/+;Gli3_Mos1/Mos1 (B) and Sox10 LacZ/+;Gli3_Xt-J/Xt-J_ embryos (C). The Sox10 LacZ_-expressing sympathetic, cranial and DRG appeared unaffected in Sox10 LacZ/+;Gli3_Mos1/Mos1 (B) and Sox10 LacZ/+;Gli3_Xt-J/Xt-J_ (C) embryos as compared with Sox10 Lacz/+ control embryos (A). Ectopic Sox10 LacZ_-expressing cells adjacent to the neural tube in Sox10 LacZ/+;Gli3_Mos1/Mos1 (E, Hbold>) and Sox10 LacZ/+;Gli3_Xt-J/Xt-J_ (F, I) embryos are indicated by arrowheads. The number of Sox10 LacZ_-expressing melanoblasts was reduced in Sox10 LacZ/+ ;Gli3 Mos1/Mos1 (E, H, K) and Sox10 LacZ/+;Gli3_Xt-J/Xt-J (F, I, L) embryos within the medial lateral trunk region as compared with Sox10 Lacz/+ control embryos (D, G, J).

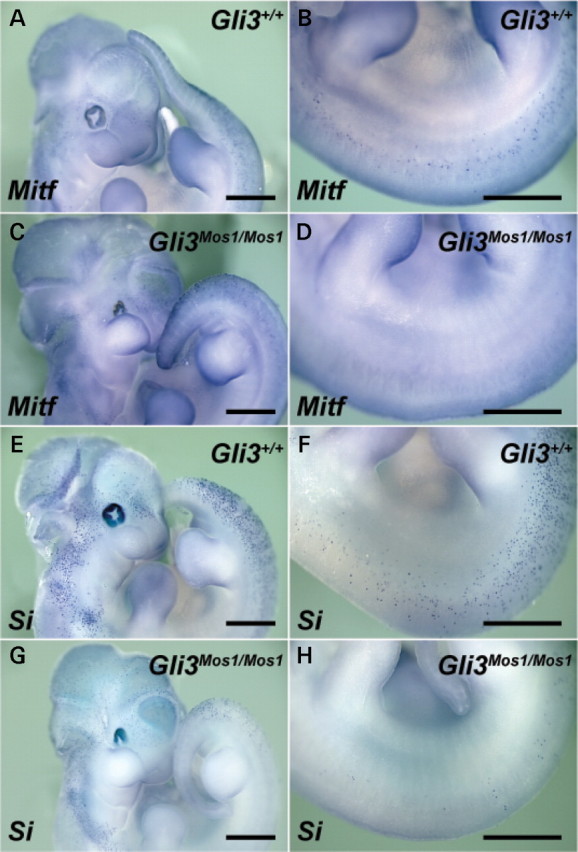

Mos1 mutant embryos show dramatic reduction in early stage melanoblasts

To further investigate the reduction in melanoblasts observed in the mid-trunk of Sox10 LacZ/+ ;Gli3 Mos1/Mos1 mutants, we next evaluated expression of the early melanoblast markers Mitf and Si in homozygous Gli3 Mos1/Mos1 embryos (Fig. 6). In E11.5 wild-type embryos, numerous melanoblasts were present in the head, cervical region, tail and trunk. As was observed with Sox10 LacZ expression, _Mitf_- and _Si_-positive melanoblasts were reduced in number in the mid-trunk of mutant Gli3 Mos1/Mos1 embryos compared with wild-type embryos (Fig. 6). These data demonstrate that GLI3 deficiency alone disrupts normal trunk melanoblast specification. No ectopic expression was observed for Mitf or Si, suggesting that the ectopic _Sox10_-positive cells in Sox10 LacZ/+ ; Gli3 Mos1/Mos1 embryos (Fig. 5) were not specified melanoblasts, but instead represent other SOX10-expressing NC derivatives, potentially melanoblast precursors.

Figure 6.

GLI3 deficiency disrupts melanocyte specification in the trunk. Shown are lateral views of E11.5 embryos after whole-mount in situ hybridizations of wild-type (A, B, E, F) and Gli3 Mos1/Mos1 (C, D, G, H) embryos with probes specific for the melanoblast markers Mitf (A–D), and Si (E–H). Gli3 Mos1/Mos1 embryos show Mitf and Si expression patterns similar to wild-type embryos in the head and in cervical and tail regions (A, C, E, G). However, in the trunk region between forelimb and hind limb, Gli3 Mos1/Mos1 embryos show very few melanoblasts (D, H) as compared with wild-type embryos (B, F).

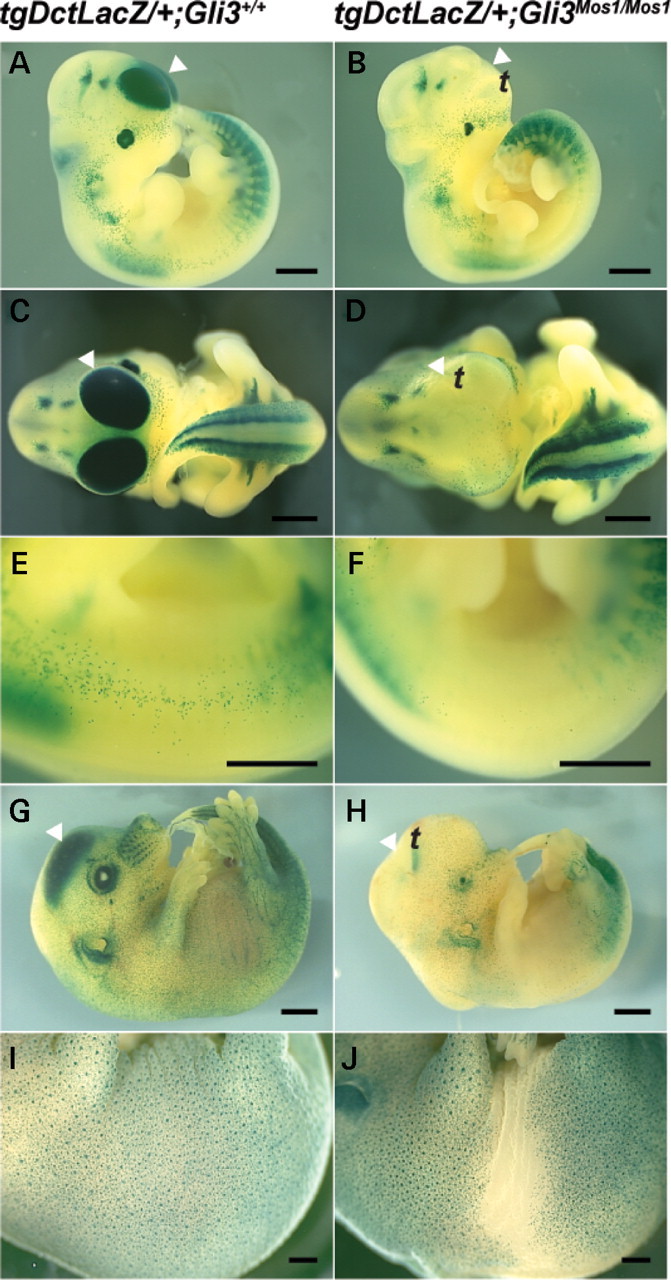

To determine if the melanoblast deficiency in GLI3-deficient embryos persists beyond E11.5, the effect of the Gli3 Mos mutation on the melanoblast lineage was examined at multiple developmental stages. For this the Tg(Dct-LacZ) line of transgenic mice was used in which the Dct promoter drives expression of LacZ in melanoblasts, caudal embryonic DRG, and the telencephalon (21–23). As with other melanoblast markers, the Gli3 Mos1/Mos1;Tg(Dct-LacZ) embryos demonstrated a severe reduction in melanoblast numbers in the mid-trunk region, throughout the ventral and dorsal surfaces at E11.5 (Fig. 7). This deficiency persisted through E14.0 and E16.0, at which time Gli3 Mos1/Mos1;Tg(Dct-LacZ) embryos presented with a large ventral region devoid of melanoblasts that extended around the lumbar trunk area (Fig. 7G–J). Heterozygous Gli3 Mos1/+;Tg(Dct-LacZ) embryos were less severely affected than their homozygous littermates and at E16.0 exhibited a small ventral region devoid of melanoblasts (data not shown), consistent with the appearance of a small white spot of ventral hypopigmentation in a subset of heterozygous animals (Fig. 2A).

Figure 7.

Tg (Dct-LacZ) expression reveals reduction of melanoblasts in Gli3 Mos1/Mos1 embryos. Lateral (A, B, E–J) or frontal (C, D) views of Gli3+/+;Tg(Dct-LacZ) (A, C, E, G, I) and Gli3_Mos1/Mos1_;Tg(Dct-LacZ) (B, D, F, H, J), embryos after X-gal staining. The trunk region extending from the ventral to the dorsal surface of Gli3 Mos1/Mos1 embryos shows a severe reduction of melanoblast numbers at E11.5 (B, F) and E14.0 (H) compared with Gli3 +/+;Tg (Dct-LacZ) embryos at E11.5 (A, E), and E14.0 (G). Lateral view of E16.0 Gli3_Mos1/Mos1_; Tg(Dct-LacZ) embryo (J) shows a reduction of melanoblast numbers of the ventral and lumbar trunk regions compared with Gli3 +/+;Tg(Dct-LacZ) E16.0 embryos (I). Arrowheads (A–D, G and H) point toward Tg(Dct-LacZ) expressing cells of the telencephalon (t). A complete absence of Tg(Dct-LacZ) expression was noted in the telencephalon (t) of Gli3 Mos1/Mos1;Tg(Dct-LacZ) embryos at E11.5 (B, D) and E14.0 (H) compared with Gli3 +/+;Tg(Dct-LacZ) embryos (A, C at E11.5; G at E14.0).

In addition to melanoblasts, LacZ is expressed in the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), DRG, and telencephalon of Tg(Dct-LacZ) embryos. In Mos1 mutant embryos, we did not observe any changes in the Tg(Dct-LacZ) expression in the RPE or DRG, but Tg(Dct-LacZ) expression was absent in the telencephalon of Gli3 Mos1/Mos1;Tg(Dct-LacZ) embryos in comparison with Gli3 +/+;Tg(Dct-LacZ) embryos at E11.5, E14.0 and E16.0 (Fig. 7, E16.0 data not shown). The loss of Tg(Dct-LacZ) expression in the telencephalon is not due to altered Sox10 expression in Gli3 Mos1/Mos1;Tg(Dct-LacZ) embryos, as Sox10 LacZ/LacZ;Tg(Dct-LacZ) embryos, which lack any functional SOX10, retain expression of Tg(Dct-LacZ) in the telencephalon (data not shown). The loss of the normal dorsal Tg(Dct-LacZ) expression in the Gli3 Mos1/Mos1;Tg(Dct-LacZ) telencephalon is consistent with the ventralization of the telencephalon previously reported in Gli3 mutants (24,25).

GLI3 deficiency does not prevent melanocyte differentiation

As Gli3 deficiency results in lethality, it was not clear whether GLI3 is required for the end stages of melanocyte differentiation such as melanin pigment production. To address this, NC cultures grown from E9.5 wild-type, Gli3 Mos1/+ (N = 3), and Gli3 Mos1/Mos1 (N = 3) embryos were grown in media supportive of melanocyte differentiation for 14 days. These cultures can be highly variable, however, it was clear that regardless of the genotype, all cultures generated large numbers of differentiated, highly pigmented melanocytes indicating that NC derived from Gli3 Mos1/+ and Gli3 Mos1/Mos1 embryos can produce fully differentiated melanocytes (Supplementary Material, Fig. S3). Additionally, skin was isolated from Gli3 Mos1/Mos1 embryos and grafted onto nude mice. Skin grafts from both wild-type (N = 2) and Gli3 Mos1/Mos1 embryos (N = 3) produced pigmented hairs indicating that GLI3-deficient melanoblasts are able to terminally differentiate, enter hair follicles and produce pigmented hairs (Supplementary Material, Fig. S3).

GLI3 repressor is sufficient for melanoblast specification

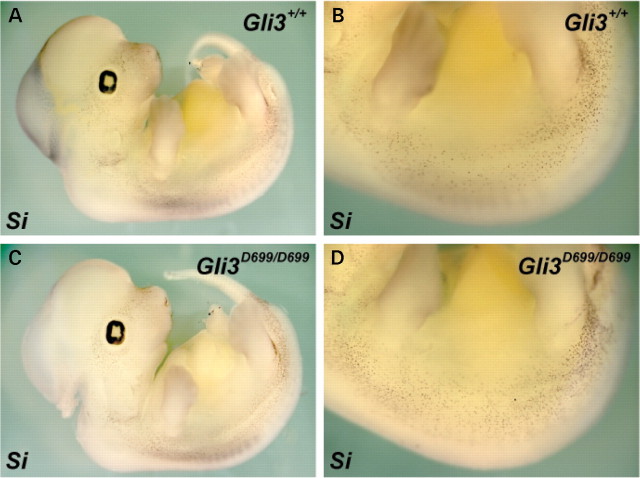

Because GLI3 can act as either a transcriptional activator or repressor in response to HH signaling (26), we sought to determine which GLI3 function was active during melanoblast development and therefore responsible for the modulation of the Sox10 haploinsufficiency defects. Our data strongly suggests that Gli3 Mos1 is a null allele predicted to lack both the GLI3 activator and the GLI3 repressor. Therefore, we used Gli3 D699 (Gli3 tm1Urt) mice that express a C-terminally truncated form of GLI3 that acts only as a transcriptional repressor (27), and analyzed Gli3 +/+, Gli3 D699/+ and Gli3 D699/D699 embryos for Si expression at E12.5. Unlike the severe reduction in melanoblasts in the trunk of Gli3 Mos1/Mos1 embryos (Fig. 6 D and H), melanoblast numbers in Gli3 D699/D699 homozygote embryos (N = 4) appeared grossly normal compared with Gli3 D699/+ heterozygote (N = 2) and Gli3 +/+ wild-type embryos (N = 2) (Fig. 8). The normal melanoblast specification in Gli3 D699/D699 embryos suggests that the GLI3 repressor promotes melanoblast specification in the absence of full-length GLI3 activator.

Figure 8.

GLI3 repressor is sufficient for melanoblast specification in the trunk. Shown are lateral views of E11.5 embryos after whole-mount in situ hybridizations of wild-type (A, B) and Gli3 D699/D699 (C, D) embryos with probes specific for the melanoblast marker Si. Gli3 D699/D699 embryos show Si expression patterns similar to wild-type embryos. We did not observe a drastic reduction in trunk melanoblasts as was observed in Gli3 Mos1/Mos1 embryos (Fig. 6) that lack both GLI3 activator and repressor function.

DISCUSSION

In Sox10 haploinsufficient mice and other disease models, quantitative trait loci (QTL) analysis has been a successful approach to map a number of loci that modify the severity of disease traits, however, identification and confirmation of the causative sequence variation is labor intensive and has only been completed for a small number of mapped QTLs (28). Additionally, recent data suggest that variation among the classical inbred strains is limited and not evenly distributed throughout the genome (29), thus leaving large regions of the genome without the sequence diversity needed to be screened using current QTL methodologies. One way to increase the repertoire of genetic variation that can be tested for modifier effects is to introduce genome wide mutations into genetic crosses where the phenotype of interest has been well characterized, thus allowing potential modifier effects for every locus in the genome to be screened. Historically, this type of mutagenesis screen to identify enhancers and suppressors of phenotypes has been extremely successful in lower model organisms (30) and more recently applied in mice to identify factors involved in selective biological processes (31,32). Indeed, these mutagenesis screens have some distinct advantages over QTL analysis for the identification of specific sequence variations that modify a phenotype of interest (33) including the relative ease with which the causative sequence variation can be identified.

In this paper, we present a sensitized mutagenesis screen to identify candidate genes for human neurocristopathies. Using this dominant screen we identified three loci that increased the severity of neurocristopathy in Sox10 haploinsufficient mice and have mapped these loci to regions not previously attributed to known WS loci. By including Sox10 haploinsufficiency in the screen, we can identify mutations with no heterozygote phenotype on their own, which otherwise could only be detected with an additional generation of breeding (∼10 weeks in mice) that is required for a traditional three-generation recessive screen. In addition, our screen retains mutations that could be missed in a three-generation recessive screen due to embryonic lethality, which was in fact observed for all 3 of the loci reported here. The use of two different inbred strains in the screen eliminated the outcrossing required to map loci, thus allowing us to quickly determine if our phenotypes are caused by mutations in novel loci or represent mutations in previously identified NC development and disease genes.

One of the pedigrees identified in our ENU screen, Mos1, showed semidominant hypopigmentation and polydactyly and resulted in homozygous embryonic lethality. The extent of hypopigmentation was significantly increased in Mos1/+; Sox10 LacZ/+ double heterozygotes compared with mice carrying heterozygous mutations in either single gene suggesting a synergistic interaction between the two loci. Subsequent linkage and candidate gene analysis identified a causative point mutation in Gli3. We showed that a previously published null allele of Gli3, Gli3 Xt-J, had similar effects on pigmentation and survival. Additionally, a complementation test done by intercrossing Gli3 Xt-J/+ and Gli3 Mos1/+ mice failed to produce any viable compound heterozygous mice carrying both mutations, thus providing strong evidence that the stop mutation identified in Gli3 Mos1 results in a functionally null allele that is responsible for the hypopigmentation in the Mos1 mice. Double heterozygous mice carrying mutations in both Sox10 and Gli3 show a significant increase in hypopigmentation compared with the Sox10 LacZ/+ heterozygous mice. In particular, double heterozygous Sox10 LacZ/+;Gli3 Mos1/+ mice exhibit extensive ventral hypopigmentation that can extend over the dorsal surface to form a belt. Using Mitf, Si, Dct LacZ and Sox10 LacZ expression analysis, we showed that Gli3 deficiency results in a vast reduction of melanoblasts in the trunk.

Gli3 is a member of the GLI family of C2H2-type zinc finger transcription factors whose members are vertebrate homologs of the Drosophila Cubitus interruptus (Ci) gene (34). GLI family members mediate the final stages of HH signaling and their regulation of HH target genes plays an important role during embryogenesis (reviewed in 35). The timing and location of Gli3 expression in the dorsal neural tube overlaps with where NC cells form (20,36), consistent with a role for GLI3 in specification of NC derivatives. However, the reduction in melanoblast specification in Gli3 Mos1/Mos1 embryos is unlikely to result from an overall reduction of NC, since DRG and sympathetic ganglia appear relatively normal in these regions. Our observation that GLI3 deficiency does not impair later stages of melanocyte differentiation is consistent with an early role for GLI3 during specification of the melanocyte lineage. Interestingly, melanoblast specification outside the trunk region of Gli3 Mos1/Mos1 embryos was not noticeably reduced. This embryonic phenotype is consistent with the phenotype in Sox10 LacZ/+ ; Gli3 Mos1/+ adult animals where hypopigmentation is limited to the trunk. This region-specific effect on melanoblast specification could be reflective of normal, wild-type melanoblast distribution, where lower melanoblast numbers are seen in the mid-trunk region (21,22,37). Alternatively, there could be independent pathways that compensate for the loss of GLI3 in regions outside the trunk. Collectively, our data provides strong evidence supporting a role for Gli3 in early specification of the melanocyte lineage.

During development, GLI3 can act as either a transcriptional activator or repressor, and HH signaling regulates this dual activator/repressor function. In the presence of HH, full-length GLI3 activates target genes, while in the absence of HH, posttranslational cleavage of the C-terminus of GLI3 produces an N-terminal form of GLI3 that acts as a repressor (26) (reviewed in 38 and 39). Given that the NC is induced at the dorsal neural tube in a region with low HH activity, we predict that the GLI3 repressor would be the main GLI3 protein product involved in melanoblast specification. In support of this hypothesis, Gli3 D699/D699 mutant embryos, which specifically express only the C-terminally truncated GLI3 repressor (27), had normal numbers of trunk melanoblasts. These results show that the repressor form of GLI3 promotes melanoblast specification, and suggest that a low level of HH signaling is required for normal melanoblast specification.

The precise mechanism through which the GLI3 repressor acts to facilitate melanoblast specification remains to be determined. Because Sox10 interacts with a number of genes during melanocyte development, including Mitf (40–43) and components of the wingless-related MMTV integration site (Wnt) signaling pathway (44,45), the genetic interaction we observe between Gli3 and Sox10 mutants could be mediated through these other pathways rather than a direct interaction with Sox10. Recent work reveals that canonical Wnt signaling may directly activate Gli3, thereby helping to establish dorsal ventral patterning within the spinal cord (46). Interestingly, the GLI3 repressor has been shown to inhibit canonical Wnt signaling by physically interacting with and antagonizing active forms of β-catenin (47). Thus, Gli3 appears to be both a target of and a regulator of canonical Wnt signaling. The careful balance of HH and Wnt signaling was shown to affect neuronal subtypes within the developing spinal cord (46) suggesting that perhaps interactions between the HH and Wnt signaling cascades could also play a role in melanocyte progenitor cell fate. Wnt signaling is known to influence the proliferation and specification of melanocyte precursors (48–52), and it is possible that loss of GLI3 repressor in Gli3 Mos1/Mos1 mutants perturbs the balance of HH and Wnt signaling, resulting in a ventralization of cell fate that affects the melanocyte lineage.

As a well-established downstream target and mediator of Wnt signaling (53–55), Mitf provides an intriguing direct target for GLI3 repression within the melanocyte lineage. However, a preliminary search for GLI3 binding sites did not identify any highly conserved GLI3 binding sites within the Mitf promoter suggesting that the GLI3 repressor acts indirectly to regulate Mitf expression. While it is likely that GLI3 interacts with a number of target genes during NC lineage specification, Foxd3 is a promising candidate for a GLI3 target and we hypothesize that this binding could indirectly regulate Mitf expression. Fox genes have been implicated in mediating HH signaling in craniofacial NC derivatives (56) and the zebrafish foxd3 directly binds the mitfa promoter, thereby repressing transcription and inhibiting _mitfa_-positive melanoblast specification (57). Therefore it is possible that in Gli3 Mos1/Mos1 mutants, Foxd3 expression is deregulated, thus disrupting melanoblast specification. While significant future work remains to determine the mechanism through which the GLI3 repressor affects melanoblast specification, our findings clearly implicate GLI3 as a participant in these networks and uncover a new role for GLI3 in the melanocyte lineage.

In conclusion, we have identified three loci that act as modifiers for _Sox10_-dependent melanocyte defects, increasing both penetrance and severity of the defects in Sox10 LacZ/+ heterozygous mice. We have shown that one of these loci is a mutation in Gli3 and have demonstrated the phenotype caused by a reduction in normal Gli3 gene dosage is significantly exacerbated by a reduction in Sox10 gene dosage (Sox10 LacZ/+ mice), suggesting that the two genes cooperate, directly or indirectly, during specification of the melanocyte lineage. These data highlight the role of Gli3 signaling in melanocyte development, and predict the importance of future studies investigating the role of GLI3 and/or SOX10 in other human disorders that combine digit and melanocyte defects.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mouse husbandry

BALB/cJ and C57BL/6J inbred mouse strains were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Engineered mice with a LacZ cassette replacing the endogenous Sox10 locus (Sox10 LacZ or Sox10 tmWeg) (13) were obtained on a mixed genetic background and maintained at NHGRI by crossing to C57BL/6J. The Gli3 Xt-J mice that carry a spontaneous mutation in Gli3 were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (stock B6.C3-Gli3 Xt-J/J) and maintained at NIH by crossing to C57BL/6J. Gli3 tm1Urt, herein referred to as Gli3 D699 mice, were provided by Ulrich Ruther (27). All other mice described in the ENU screen and embryology studies were bred and housed in an NHGRI animal facility according to NIH guidelines. For genotyping, genomic DNA was prepared from tail biopsies or yolk sacs using a PUREGENE DNA purification kit (Gentra Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA) according to the manufacturers instructions. Noon on the day of vaginal plug observation was designated E0.5 for timed pregnancies.

ENU injections

ENU was prepared and injections carried out as previously described (58). Briefly, _N_-ethyl-_N_-nitrosourea (ENU) (Sigma; St. Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved at 100 mg/ml in 95% ethanol and then diluted to 5 mg/ml in a sterile phosphate/citrate buffer (0.1 M dibasic sodium phosphate, 0.05 M sodium citrate, pH 5.0). A spectrophotometer reading at a wavelength of 398 nm was used to confirm the ENU concentration, and BALB/cJ male mice were given weekly intraperitoneal injections of 0.1 mg/g of body weight for three consecutive weeks. Mice were allowed to recover for 8 weeks post-injection and loss of fertility was confirmed by mating with C57BL/6J females. Five males that lost and subsequently regained fertility (G0) were bred to C57BL/6J females beginning at 12 weeks post-injection. In total, 230 resulting first generation progeny (G1) were crossed to Sox10 LacZ/+ mice and all subsequent offspring (G2) were observed at weaning for hypopigmentation that extended beyond the ventral surface.

Quantitation of hypopigmentation

To quantitate the extent of ventral hypopigmentation in Sox10 LacZ/+ mice in G2 mice bred from non-mutagenized BALB/cJ males, the ventral surface of mice was photographed and the area of hypopigmentation was quantitated as a proportion of the total ventral surface area. Analysis was performed using the public domain NIH Image software developed at the U.S. National Institutes of Health and freely available (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/nih-image). Once the extent of hypopigmentation was shown to be consistent in the G2s from the BALB/cJ and C57BL/6J mixed genetic background, all mice bred for this study were assigned a numerical score of 0–4,with 1 representing the smallest spots of visible hypopigmentation, to quantitatively represent the extent of ventral hypopigmentation observed.

Genetic mapping and sequencing

All three Mos loci were mapped using only affected animals for analysis. For the full genome scans, affected Mos1 and Mos3 mice were genotyped on the Illumina platform for SNPs polymorphic between the BALB/cJ and C57BL/6J parental strains used in this study (Brigham Women’s Hospital, Harvard University). Affected Mos2 mice were genotyped at polymorphic SSLP markers (CIDR, The Johns Hopkins University). A standard χ2 test was used to analyze backcross data for linkage (59) using the number of recombination events per number of meiotic opportunities for each marker. For Mos1, the linkage to Chr 13 was consistent with data from a previous genome scan where suggestive but not significant linkage to proximal Chr 13 was detected with fewer markers (91 SSLP markers).

Sequencing of Gli3 was carried out using standard techniques to PCR amplify each exon and surrounding splice sites from genomic DNA for sequence analysis (Harvard Partners Healthcare Center for Genetics and Genomics, Harvard Medical School). The sequence of an affected Mos1/+ heterozygote was compared with the sequence of the parental inbred strains to identify a single nucleotide change on the ENU-treated BALB/cJ chromosome.

Genotyping

Taqman® MGB probes (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) were designed across the Gli3 Mos1 mutation (1148C>A) specific for the wild-type BALB/cJ allele (VIC-CTTCACCTACCCCTCC) and the ENU induced mutant allele (FAM-CTTCACCTAACCCTCC). PCR reactions were carried out in 1X Taqman® Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) containing 900 nM of each primer (TCCACAGCCCTGCATTGAG and AGGATCTGTTGATGCATGTGAAGAG), and 200 nM of each allele-specific probe. Cycling conditions were 2 min at 50°C, 10 min at 95°C followed by 40 cycles of 92°C for 15 s, 60°C for 1 min. Relative quantitation of the two alleles was determined in an end-point assay.

Genotyping of the _Gli3_D699 colony knock-in allele was confirmed by Thymidine kinase (TK) positive PCR amplification with TkFOR GATGCGGCGGTGGTAATGAC and TkREV TGTGTCTGTCCTCCGGAAGG primers amplifying a 295 bp PCR product. Presence of the wild-type Gli3 allele for the Gli3 D699 colony was detected using primers Gli3-int13for: GGCCCAAACATCTACCAACACATA and Gli3-int14rev: CTGGCCACACTGAAAGGAAAAGAA, amplifying a 541 bp product. Genotype determination for Gli3 Xt-J colony was performed using primers XtJ580F: TACCCCAGCAGGAGACTCAGATTAG and XtJ580R: AAACCCGTGGCTCAGGACAAG, amplifying a 590 bp Xt allele and primers C3F: GGCCCAAACATCTACCAACACATAG and C3R: GTTGGCTGCTGCATGAAGACTGAC, amplifying a 193 bp wild-type allele.

Sox10 LacZ and Tg(Dct-LacZ) genotyping was performed by PCR amplification of the LacZ cassette as previously reported (23).

Beta-galactosidase staining

Embryos from timed pregnancies were stained for beta-galactosidase activity using standard methods. Briefly, embryos were fixed (1× PBS, 1% formaldehyde, 0.2% glutaraldehyde, 0.02% NP40) on ice for 2 h followed by three 15 min, room temperature washes (1× PBS, 2 mm MgCl2, 0.02% NP40). Staining (1× PBS, 12 mm K-Ferricyanide, 12 mm K-Ferrocyanide, 0.002% NP40, 4 mm MgCl2, and 320µg/ml 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-b-D-galactopyranoside in N,_N_-dimethyl formamide) was carried out overnight at 37°C followed by two 30 min, room temperature washes (1× PBS, 0.2% NP40). Embryos were transferred to a final fixative solution (4% formaldehyde, 10% methanol, 100 mm sodium phosphate) for analysis and storage.

Whole-mount in situ hybridization

Mouse embryos were fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Reverse-transcribed digoxigenin-conjugated probes were made from linearized plasmids. In situ hybridizations were performed by using published protocols (60) with the following modifications. After probe hybridization, Ribonuclease A digestion was omitted, and Tris-buffered saline was used in place of PBS. BM-purple substrate (Roche, Molecular Biochemicals) was used in place of 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate/nitroblue tetrazolium. Mitf and Si cDNA containing plasmids (G370008D06Rik and G370069C13Rik, respectively) were first digested with Kpn1 and then transcribed with T3 polymerase to generate DIG-labeled in situ probes.

Skin grafting

Skin grafting was performed according to standard procedures. Briefly, skin was grafted from late gestation embryos (approximately E16.5) onto 8–10 weeks old immune-compromised recipient mice (Albino Swiss Nude from Taconic; NTac:NIHS-Foxn1 nu/nu). Full-thickness skin grafts (∼1 cm in diameter) were removed aseptically from the dorsum of euthanized embryos and placed onto a similar sized dorsal skin excision made in the nu/nu recipient mice. The grafts were sutured into place and treated with triple antibiotic ointment three times per day for the first week following surgery. The grafts were allowed to grow until hair was apparent (3–4 weeks after initial surgery). Surgery and euthanasia protocols were performed in accordance with NHGRI ACUC guidelines.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary Material is available at HMG Online.

[Supplementary Data]

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Andrew Salinger and Monica Justice (Baylor College of Medicine) provided assistance establishing our ENU injection protocol. Michael Wegner (Friedrich-Alexander University of Erlangen and Nuremberg, Erlangen, Germany) provided Sox10 LacZ mice and Ulrich Ruther (Heinrich-Heine University, Düsseldorf, Germany) and Matthew Kelley (NIDCD, NIH) provided Gli3 D699 mice. Genotyping services used for mapping were provided by David Beier and Jennifer Moran (Brigham Women’s Hospital, Harvard University), MaryPat Jones (NHGRI Genomics Core), and the Center for Inherited Disease Research (CIDR). Leslie Biesecker, Yingzi Yang, Doris Wu, and members of the Pavan laboratory provided helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript. Julia Fekecs provided graphic assistance.

Conflict of Interest statement. The authors have no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baldwin C.T., Hoth C.F., Amos J.A., da-Silva E.O., Milunsky A. An exonic mutation in the HuP2 paired domain gene causes Waardenburg’s syndrome. Nature. 1992;355:637–638. doi: 10.1038/355637a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bondurand N., Dastot-Le Moal F., Stanchina L., Collot N., Baral V., Marlin S., Attie-Bitach T., Giurgea I., Skopinski L., Reardon W., et al. Deletions at the SOX10 gene locus cause Waardenburg syndrome types 2 and 4. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;81:1169–1185. doi: 10.1086/522090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tassabehji M., Read A.P., Newton V.E., Harris R., Balling R., Gruss P., Strachan T. Waardenburg’s syndrome patients have mutations in the human homologue of the Pax-3 paired box gene. Nature. 1992;355:635–636. doi: 10.1038/355635a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tassabehji M., Newton V.E., Read A.P. Waardenburg syndrome type 2 caused by mutations in the human microphthalmia (MITF) gene. Nat. Genet. 1994;8:251–255. doi: 10.1038/ng1194-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanchez-Martin M., Rodriguez-Garcia A., Perez-Losada J., Sagrera A., Read A.P., Sanchez-Garcia I. SLUG (SNAI2) deletions in patients with Waardenburg disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2002;11:3231–3236. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.25.3231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Puffenberger E.G., Hosoda K., Washington S.S., Nakao K., deWit D., Yanagisawa M., Chakravart A. A missense mutation of the endothelin-B receptor gene in multigenic Hirschsprung’s disease. Cell. 1994;79:1257–1266. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hofstra R.M., Osinga J., Tan-Sindhunata G., Wu Y., Kamsteeg E.J., Stulp R.P., van Ravenswaaij-Arts C., Majoor-Krakauer D., Angrist M., Chakravarti A., et al. A homozygous mutation in the EDN3 gene associated with a combined Waardenburg type 2 and Hirschsprung phenotype (Shah-Waardenburg syndrome) Nat. Genet. 1996;12:445–447. doi: 10.1038/ng0496-445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edery P., Attie T., Amiel J., Pelet A., Eng C., Hofstra R.M., Martelli H., Bidaud C., Munnich A., Lyonnet S. Mutation of the endothelin-3 gene in the Waardenburg-Hirschsprung disease (Shah-Waardenburg syndrome) Nat. Genet. 1996;12:442–444. doi: 10.1038/ng0496-442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pingault V., Bondurand N., Kuhlbrodt K., Goerich D.E., Prehu M.O., Puliti A., Herbarth B., Hermans-Borgmeyer I., Legius E., Matthijs G., et al. SOX10 mutations in patients with Waardenburg-Hirschsprung disease. Nat. Genet. 1998;18:171–173. doi: 10.1038/ng0298-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mollaaghababa R., Pavan W.J. The importance of having your SOX on: role of SOX10 in the development of neural crest-derived melanocytes and glia. Oncogene. 2003;22:3024–3034. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silver D.L., Hou L., Pavan W.J. The genetic regulation of pigment cell development. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2006;589:155–169. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-46954-6_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Southard-Smith E.M., Kos L., Pavan W.J. Sox10 mutation disrupts neural crest development in Dom Hirschsprung mouse model. Nat. Genet. 1998;18:60–64. doi: 10.1038/ng0198-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Britsch S., Goerich D.E., Riethmacher D., Peirano R.I., Rossner M., Nave K.A., Birchmeier C., Wegner M. The transcription factor Sox10 is a key regulator of peripheral glial development. Genes Dev. 2001;15:66–78. doi: 10.1101/gad.186601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tachibana M., Kobayashi Y., Matsushima Y. Mouse models for four types of Waardenburg syndrome. Pigment Cell Res. 2003;16:448–454. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0749.2003.00066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson D.R. Extra-toes: anew mutant gene causing multiple abnormalities in the mouse. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 1967;17:543–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dickie M.M. Presumed recurrences of mutations. Mouse News Lett. 1967;36:60. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kang S., Graham J.M., Jr, Olney A.H., Biesecker L.G. GLI3 frameshift mutations cause autosomal dominant Pallister-Hall syndrome. Nat. Genet. 1997;15:266–268. doi: 10.1038/ng0397-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vortkamp A., Gessler M., Grzeschik K.H. GLI3 zinc-finger gene interrupted by translocations in Greig syndrome families. Nature. 1991;352:539–540. doi: 10.1038/352539a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnston J.J., Olivos-Glander I., Killoran C., Elson E., Turner J.T., Peters K.F., Abbott M.H., Aughton D.J., Aylsworth A.S., Bamshad M.J., et al. Molecular and clinical analyses of Greig cephalopolysyndactyly and Pallister-Hall syndromes: robust phenotype prediction from the type and position of GLI3 mutations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2005;76:609–622. doi: 10.1086/429346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hui C.C., Joyner A.L. A mouse model of Greig cephalopolysyndactyly syndrome: the extra-toesJ mutation contains an intragenic deletion of the Gli3 gene. Nat. Genet. 1993;3:241–246. doi: 10.1038/ng0393-241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pavan W.J., Tilghman S.M. Piebald lethal (sl) acts early to disrupt the development of neural crest-derived melanocytes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:7159–7163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.7159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mackenzie M.A., Jordan S.A., Budd P.S., Jackson I.J. Activation of the receptor tyrosine kinase Kit is required for the proliferation of melanoblasts in the mouse embryo. Dev. Biol. 1997;192:99–107. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hakami R.M., Hou L., Baxter L.L., Loftus S.K., Southard-Smith E.M., Incao A., Cheng J., Pavan W.J. Genetic evidence does not support direct regulation of EDNRB by SOX10 in migratory neural crest and the melanocyte lineage. Mech. Dev. 2006;123:124–134. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rash B.G., Grove E.A. Patterning the dorsal telencephalon: a role for sonic hedgehog? J. Neurosci. 2007;27:11595–11603. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3204-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jiao Z., Zhang Z.G., Hornyak T.J., Hozeska A., Zhang R.L., Wang Y., Wang L., Roberts C., Strickland F.M., Chopp M. Dopachrome tautomerase (Dct) regulates neural progenitor cell proliferation. Dev. Biol. 2006;296:396–408. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang B., Fallon J.F., Beachy P.A. Hedgehog-regulated processing of Gli3 produces an anterior/posterior repressor gradient in the developing vertebrate limb. Cell. 2000;100:423–434. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80678-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bose J., Grotewold L., Ruther U. Pallister-Hall syndrome phenotype in mice mutant for Gli3. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2002;11:1129–1135. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.9.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Flint J., Valdar W., Shifman S., Mott R. Strategies for mapping and cloning quantitative trait genes in rodents. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2005;6:271–286. doi: 10.1038/nrg1576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang H., Bell T.A., Churchill G.A., Pardo-Manuel de Villena F. On the subspecific origin of the laboratory mouse. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:1100–1107. doi: 10.1038/ng2087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.St Johnston D. The art and design of genetic screens: Drosophila melanogaster. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2002;3:176–188. doi: 10.1038/nrg751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carpinelli M.R., Hilton D.J., Metcalf D., Antonchuk J.L., Hyland C.D., Mifsud S.L., Di Rago L., Hilton A.A., Willson T.A., Roberts A.W., et al. Suppressor screen in Mpl−/− mice: c-Myb mutation causes supraphysiological production of platelets in the absence of thrombopoietin signaling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:6553–6558. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401496101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Speca D.J., Rabbee N., Chihara D., Speed T.P., Peterson A.S. A genetic screen for behavioral mutations that perturb dopaminergic homeostasis in mice. Genes Brain. Behav. 2006;5:19–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2005.00127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nadeau J.H., Frankel W.N. The roads from phenotypic variation to gene discovery: mutagenesis versus QTLs. Nat. Genet. 2000;25:381–384. doi: 10.1038/78051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ruppert J.M., Vogelstein B., Arheden K., Kinzler K.W. GLI3 encodes a 190-kilodalton protein with multiple regions of GLI similarity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1990;10:5408–5415. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.10.5408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ruiz i Altaba A. Gli proteins and Hedgehog signaling: development and cancer. Trends Genet. 1999;15:418–425. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01840-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee J., Platt K.A., Censullo P., Ruiz i Altaba A. Gli1 is a target of sonic hedgehog that induces ventral neural tube development. Development. 1997;124:2537–2552. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.13.2537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Silver D., Hou L., Somerville R., Young M., Apte S., Pavan W. The secreted metalloprotease ADAMTS20 is required for melanoblast survival. PLoS Genet. 2008;4 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000003. e1000003 doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ruiz i Altaba A., Nguyen V., Palma V. The emergent design of the neural tube: prepattern, SHH morphogen and GLI code. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2003;13:513–521. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2003.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Biesecker L.G. What you can learn from one gene: GLI3. J. Med. Genet. 2006;43:465–469. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.029181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Potterf S.B., Furumura M., Dunn K.J., Arnheiter H., Pavan W.J. Transcription factor hierarchy in Waardenburg syndrome: regulation of MITF expression by SOX10 and PAX3. Hum. Genet. 2000;107:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s004390000328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee M., Goodall J., Verastegui C., Ballotti R., Goding C.R. Direct regulation of the Microphthalmia promoter by Sox10 links Waardenburg-Shah syndrome (WS4)-associated hypopigmentation and deafness to WS2. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:37978–37983. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003816200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bondurand N., Pingault V., Goerich D.E., Lemort N., Sock E., Le Caignec C., Wegner M., Goossens M. Interaction among SOX10, PAX3 and MITF, three genes altered in Waardenburg syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2000;9:1907–1917. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.13.1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Verastegui C., Bille K., Ortonne J.P., Ballotti R. Regulation of the microphthalmia-associated transcription factor gene by the Waardenburg syndrome type 4 gene, SOX10. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:30757–30760. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000445200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Werner T., Hammer A., Wahlbuhl M., Bosl M.R., Wegner M. Multiple conserved regulatory elements with overlapping functions determine Sox10 expression in mouse embryogenesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:6526–6538. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aoki Y., Saint-Germain N., Gyda M., Magner-Fink E., Lee Y.H., Credidio C., Saint-Jeannet J.P. Sox10 regulates the development of neural crest-derived melanocytes in Xenopus. Dev. Biol. 2003;259:19–33. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00161-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Alvarez-Medina R., Cayuso J., Okubo T., Takada S., Marti E. Wnt canonical pathway restricts graded Shh/Gli patterning activity through the regulation of Gli3 expression. Development. 2008;135:237–247. doi: 10.1242/dev.012054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ulloa F., Itasaki N., Briscoe J. Inhibitory Gli3 activity negatively regulates Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Curr. Biol. 2007;17:545–550. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.01.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dunn K.J., Brady M., Ochsenbauer-Jambor C., Snyder S., Incao A., Pavan W.J. WNT1 and WNT3a promote expansion of melanocytes through distinct modes of action. Pigment Cell Res. 2005;18:167–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.2005.00226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hari L., Brault V., Kleber M., Lee H.Y., Ille F., Leimeroth R., Paratore C., Suter U., Kemler R., Sommer L. Lineage-specific requirements of beta-catenin in neural crest development. J. Cell. Biol. 2002;159:867–880. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200209039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jin E.J., Erickson C.A., Takada S., Burrus L.W. Wnt and BMP signaling govern lineage segregation of melanocytes in the avian embryo. Dev. Biol. 2001;233:22–37. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Takeda K., Yasumoto K., Takada R., Takada S., Watanabe K., Udono T., Saito H., Takahashi K., Shibahara S. Induction of melanocyte-specific microphthalmia-associated transcription factor by Wnt-3a. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:14013–14016. doi: 10.1074/jbc.c000113200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dorsky R.I., Moon R.T., Raible D.W. Control of neural crest cell fate by the Wnt signalling pathway. Nature. 1998;396:370–373. doi: 10.1038/24620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dorsky R.I., Raible D.W., Moon R.T. Direct regulation of nacre, a zebrafish MITF homolog required for pigment cell formation, by the Wnt pathway. Genes Dev. 2000;14:158–162. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Saito H., Yasumoto K., Takeda K., Takahashi K., Yamamoto H., Shibahara S. Microphthalmia-associated transcription factor in the Wnt signaling pathway. Pigment Cell Res. 2003;16:261–265. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0749.2003.00039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dorsky R.I., Moon R.T., Raible D.W. Environmental signals and cell fate specification in premigratory neural crest. Bioessays. 2000;22:708–716. doi: 10.1002/1521-1878(200008)22:8<708::AID-BIES4>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jeong J., Mao J., Tenzen T., Kottmann A.H., McMahon A.P. Hedgehog signaling in the neural crest cells regulates the patterning and growth of facial primordia. Genes Dev. 2004;18:937–951. doi: 10.1101/gad.1190304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ignatius M.S., Moose H.E., El-Hodiri H.M., Henion P.D. Colgate/hdac1 repression of foxd3 expression is required to permit mitfa-dependent melanogenesis. Dev. Biol. 2007;313:568–583. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.10.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Justice M. Mutagenesis of the mouse germline. In: Jackson I.J., Abbott C.M., editors. Mouse Genetics and Transgenics: A Practical Approach. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 185–214. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Silver L. Mouse Genetics: Concepts and Applications. UK: Oxford University Press; 1995. Classical linkage analysis and mapping panels. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wilkinson D.G., Nieto M.A. In: Methods in Enzymology: Guide to Techniques in Mouse Development. Wassarman P., DePamphilis M., editors. San Diego: Academic; 1993. pp. 361–373. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Selicorni A., Guerneri S., Ratti A., Pizzuti A. Cytogenetic mapping of a novel locus for type II Waardenburg syndrome. Hum. Genet. 2002;110:64–67. doi: 10.1007/s00439-001-0643-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Southard-Smith E.M., Angrist M., Ellison J.S., Agarwala R., Baxevanis A.D., Chakravarti A., Pavan W.J. The Sox10(Dom) mouse: modeling the genetic variation of Waardenburg-Shah (WS4) syndrome. Genome Res. 1999;9:215–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rhim H., Dunn K.J., Aronzon A., Mac S., Cheng M., Lamoreux M.L., Tilghman S.M., Pavan W.J. Spatially restricted hypopigmentation associated with an Ednrbs-modifying locus on mouse chromosome 10. Genome Res. 2000;10:17–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dai P., Akimaru H., Tanaka Y., Maekawa T., Nakafuku M., Ishii S. Sonic Hedgehog-induced activation of the Gli1 promoter is mediated by GLI3. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:8143–8152. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.12.8143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kalff-Suske M., Wild A., Topp J., Wessling M., Jacobsen E.M., Bornholdt D., Engel H., Heuer H., Aalfs C.M., Ausems M.G., et al. Point mutations throughout the GLI3 gene cause Greig cephalopolysyndactyly syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1999;8:1769–1777. doi: 10.1093/hmg/8.9.1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhou H., Kim S., Ishii S., Boyer T.G. Mediator modulates Gli3-dependent Sonic hedgehog signaling. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006;26:8667–8682. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00443-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

[Supplementary Data]