Clinical importance of aspirin and clopidogrel resistance (original) (raw)

Abstract

Aspirin and clopidogrel are important components of medical therapy for patients with acute coronary syndromes, for those who received coronary artery stents and in the secondary prevention of ischaemic stroke. Despite their use, a significant number of patients experience recurrent adverse ischaemic events. Interindividual variability of platelet aggregation in response to these antiplatelet agents may be an explanation for some of these recurrent events, and small trials have linked “aspirin and/or clopidogrel resistance”, as measured by platelet function tests, to adverse events. We systematically reviewed all available evidence on the prevalence of aspirin/clopidogrel resistance, their possible risk factors and their association with clinical outcomes. We also identified articles showing possible treatments. After analyzing the data on different laboratory methods, we found that aspirin/clopidogrel resistance seems to be associated with poor clinical outcomes and there is currently no standardized or widely accepted definition of clopidogrel resistance. Therefore, we conclude that specific treatment recommendations are not established for patients who exhibit high platelet reactivity during aspirin/clopidogrel therapy or who have poor platelet inhibition by clopidogrel.

Keywords: Aspirin, Clopidogrel, Antiplatelet agent, Aspirin resistance, Clopidogrel resistance, Cardiovascular outcome, Platelet aggregation

INTRODUCTION

Platelets adhere to sites of vascular injury. Atherosclerotic lesions are associated with impaired endothelial function and hence are susceptible to platelet and leukocyte adhesion. Indeed, patients with atherosclerosis have enhanced baseline platelet activation, which is reflected by corresponding increases in urinary thromboxane (TX) metabolite excretion[1-3]. It should be hoted, however, that endothelial disruption is not a prerequisite for platelet adhesion. Initially, platelets tether to the vessel wall via membrane integrins and selectins. Subsequent rolling and firm adhesion have been demonstrated by intravital microscopy in experimental models of microvascular injury. Shear stress augments adhesion receptor engagement and platelet activation (so-called “outside-in” signaling). This in turn triggers release or generation of soluble platelet activators such as TX, adenosine diphosphate (ADP), and thrombin. A layer of activated platelets forms and attracts other platelets and leukocytes. This is followed by either stable thrombus formation or rapid resolution.

Activated platelets release inflammatory and mitogenic proteins that promote leukocyte chemoattraction, vascular inflammation and further modify the endothelial phenotype[2]. Indeed, there is growing evidence that platelet adhesion is involved in the earliest development of atherosclerotic lesions. On activation, the most densely expressed platelet, integrin IIbβ3 [glycoprotein (GP) IIb/IIIa], undergoes conformational change, binds soluble fibrinogen and von Willebrand factor and facilitates platelet aggregate formation. Notably, GP IIb/IIIa gradually loses its binding capacity when platelets are stimulated by ADP alone. However, more potent agonists, such as thrombin, induce persistent fibrinogen binding. The cycle of initiation, propagation, and perpetuation of platelet activation creates the platelet mass that forms a nidus for coagulation. Fibrin generation and release of secondary platelet agonists propagate this process. Secondary agonists continuously activate integrins and importantly may be required to prevent disassembly of the early platelet aggregate. Six soluble ADP, TXA2, soluble CD40 ligand, and the product of growth arrest specific gene 6 are prominent in these paracrine signaling pathways[3].

Oral antiplatelet drugs are a cornerstone of modern pharmacotherapy in cardiovascular atherothrombotic diseases. The efficacy of acetylsalicylic acid (ASA, aspirin) and clopidogrel in decreasing the risk of adverse events in vascular disease patients has been well established in the past 20 years. Despite chronic oral antiplatelet therapy, a number of atherothrombotic events continue to occur. In recent years, a number of reports in the literature have shown possible relationships between residual platelet activity, as measured with a variety of laboratory tests, and clinical outcomes, raising the possibility that ‘resistance’ to oral antiplatelet drugs may underlie many such adverse events. The aim of our review was to collect articles showing the definition, detection, risk factors and clinical consequences of aspirin and clopidogrel resistance.

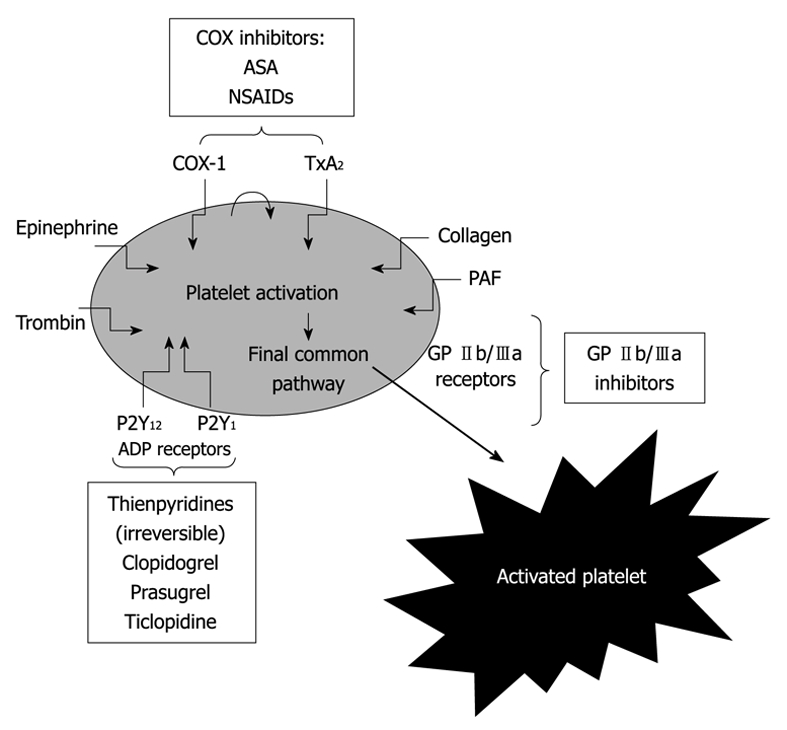

The effect of aspirin is mediated by the irreversible inactivation of cyclooxygenase (COX-1), leading to the prevention of thromboxane A2 generation from arachidonic acid. Following oral administration, aspirin is effective as an antiplatelet agent within 60 min. COX-1 is rapidly resynthesized by nucleated cells, such as endothelial cells, and therefore the effect of aspirin on nucleated cells lasts only for a relatively short time[4-8]. In contrast, the effect of aspirin on platelets (anucleate cells) lasts for the life of the platelets (7-10 d)[9] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Pathways of platelet activation and mechanism of action of antiplatelet agents[2]. COX: Cyclooxygenase; GP: Glycoprotein; TxA2: Thromboxane A2; ASA: Acetylsalicylic acid; NSAIDs: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PAF: Platelet-activating factor.

Clopidogrel, an ADP-receptor antagonist, is a prodrug requiring oxidation by the hepatic cytochrome P450 (CYP450) to generate an active metabolite[10]. Only a small proportion of clopidogrel undergoes metabolism by CYP450; it is mostly hydrolyzed by esterases to an inactive carboxylic acid derivative that accounts for 85% of clopidogrel-related circulating compounds. CYP3A4 and CYP3A5 are the enzymes responsible for the oxidation of the thiophene ring of clopidogrel to 2-Oxo-clopidogrel, which is further oxidized, resulting in the opening of the thiophene ring and the formation of both a carboxyl and a thiol group[10]. The latter forms a disulfide bridge with the two extracellular cysteine residues located on the ADP P2Y12 receptor expressed on the platelet surface and causes an irreversible blockade of ADP binding for the platelet’s life span[11]. Inhibition of platelet function is consistent with time-dependent, cumulative inhibition of platelet aggregation on repeated daily dosing and with slow recovery of platelet function on drug withdrawal (Figure 1).

LABORATORY ANTIPLATELET RESISTANCE

The definition of resistance

An exact definition of “resistance” to antiplatelet therapy on the basis of physiology does not exist. However, there is a significant prevalence of variable responses to dual antiplatelet regimens similar to different responses to anti-hypertensive therapy or statin therapy. Therefore, it is imperative to understand this variable response or hyporesponsiveness to aspirin and clopidogrel in some patients. A clear definition of this response should be established and, based on this, one may then be able to categorize patients as a responders, hyporesponders, nonresponders, or resistant and thus manage their therapeutic regimen accordingly[9-12].

Laboratory detection

Thromboxane A2 production: Serum thromboxane B2 (TxB2) reflects the total capacity of platelets to synthesize TxA2, which is the most specific test to measure the pharmacological effects of aspirin[10,11].

The urinary levels of TxB2 metabolite, 11-dehydro-TxB2, represent a time-integrated index of TxA2 biosynthesis in vivo. Because it is not formed in the kidney, detection of this TxA2 metabolite in the urine reflects systemic TxA2 formation, although about 30% of the urinary metabolite derives from extra-platelet sources. Therefore, the method is not highly specific for monitoring the effects of aspirin on platelet COX-1[13,14].

Optical aggregometry: The historical “gold standard” is turbidometric platelet aggregometry, which measures platelet coaggregation in platelet-rich plasma[4,10]. Samples are exposed to an agonist, such as collagen, epinephrine, ADP or arachidonic acid, and the increase in light transmittance resulting from platelet-platelet aggregation is measured. Its disadvantages include the large sample volumes required, long processing times and complex sample preparation[11,13,15]. Its advantages are that it can be used to monitor ASA, thienopyridines and platelet GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor therapy[15].

Platelet function analyzer-100 system: The platelet function analyzer (PFA-100) measures in vitro the cessation of high-shear blood flow by the platelet plug. It is a simple, rapid, point-of-care, whole blood method that requires low sample volumes and no sample preparation. Its disadvantages are that it is dependent on the Von Willebrand factor and hematocrit levels and that it requires pipetting[10-12,15].

Kotzailias et al[16] indicated that the current PFA-100 cartridges are not sufficiently sensitive to detect clopidogrel-induced platelet inhibition in stroke patients. A recent consensus paper concluded that this method is not recommended for monitoring of thienopyridines[15]. On the other hand, Marcucci et al[17] showed that this method (combined with optical aggregometry) can be useful in the detection of residual platelet activity, which was associated with worsening cardiovascular outcomes in 367 consecutive adult patients admitted to hospital, including 200 patients on dual antiplatelet agents (group A) and 167 on dual antiplatelet agents plus GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors (group B), with a diagnosis of ST-segment elevation acute MI.

Impedance aggregometry: Impedance aggregometry measures the change in electrical impedance between two electrodes when platelets are aggregated by an agonist. The method is similar to light or optical aggregometry except that it can be done in whole blood, thus obviating the need for preparation of a platelet suspension. Impedance aggregometry can also be done in thrombocytopenic patients[15].

Ultegra RPFA-ASA: The Ultegra RPFA-ASA (Accumetrics, San Diego, CA, USA) is a simple, rapid, point-of-care method that has several other advantages: required sample volumes are small, it uses whole blood and no pipetting is required[15]. If aspirin/clopidogrel produces the expected antiplatelet effect, fibrinogen-coated beads will not agglutinate and light transmission will not increase.

Thromboelastogram platelet mapping system: The thromboelastogram platelet mapping system measures platelet contribution to clot strength. It is a point-of-care method that uses whole blood to assess platelet clot formation and clot-lysis data. It is able to monitor all 3 classes of antiplatelet therapies. However, it requires pipetting and has undergone only limited study[10-12,15].

Vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein phosphorylation: Vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (VASP) phosphorylation measures activation-dependent platelet signaling. Its advantages include small required sample volumes, the use of whole blood, stability (allowing samples to be shipped to a remote laboratory) and dependency on the P2Y12 receptor, which is the site of action for clopidogrel. Its disadvantages are that it requires complex sample preparation, flow cytometry and experienced technicians[12,15].

Activation-dependent changes on the platelet surface: Other methods assess activation-dependent changes on the platelet surface. These tests include measurement of levels of platelet surface P-selectin, activated GP IIb/IIIa and leukocyte-platelet aggregation. Their advantages include the small sample volumes required and the use of whole blood; disadvantages include complex sample preparation, the requirement for flow cytometry and experienced operators and lack of commercial availability[12,15].

Comparism of methods

In a study by Lordkipanidzé et al[18], 201 patients with stable coronary artery disease receiving daily aspirin therapy (≥ 80 mg) were recruited. They found that platelet function tests (light transmission aggregometry, whole blood aggregometry, PFA-100 system, VerifyNowAspirin and urinary 11-dehydro-TxB2 concentrations) were not equally effective in measuring aspirin’s antiplatelet effect and correlated poorly amongst themselves. Their results have been confirmed by other studies[19-21].

On the other hand, a recent study based on healthy volunteers found high concordance (> 90%) between the examined assays (light transmission aggregometry, PFA-100, VerifyNow, and urinary 11-dehydro-TxB2)[22].

The assessment of platelet function inhibition by clopidogrel is also highly test-specific. Lordkipanidzé et al[23] examined 116 patients with stable coronary artery disease requiring diagnostic angiography. Agreement between assays (light transmission aggregometry (ADP 5 and 20 mmol/L as the agonist), whole-blood aggregometry (ADP 5 and 20 mmol/L), PFA-100 (Collagen-ADP cartridge) and VerifyNow P2Y12) to identify patients with insufficient inhibition of platelet aggregation by clopidogrel was also low. Their result was in concordance with other studies[24,25].

The broad use of statins, angiotensin receptor blockers and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors may be, in part, responsible for the lack of agreement[26]. Our previous results showed the effect of different cardiovascular drugs on the laboratory efficacy of aspirin and clopidogrel[27,28].

How to define antiplatelet resistance?

Based on the recent position paper of the Working Group on antiplatelet drugs resistance appointed by the Section of Cardiovascular Interventions of the Polish Cardiac Society, endorsed by the Working Group on Thrombosis of the European Society of Cardiology, the term ‘laboratory resistance’ to oral antiplatelet agents should be reserved for situations when the expected effect from an oral antiplatelet drug cannot be obtained due to changes in the target enzyme or receptor (pharmacodynamic ‘resistance’). Such situations can be ascertained with a good approximation in vitro.

For the assessment of ASA-specific effects, the proposed test is the use of aggregation induced by arachidonic acid and of TXB2 concentrations in serum (or in the supernatant after aggregation). For further evaluation, the in vitro addition of ASA can be performed before aggregation or the preparation of serum to exclude pharmacokinetic ‘resistance’.

For the assessment of a clopidogrel-specific effect, the proposed test is aggregation induced with ADP or VASP phosphorylation. For further evaluations, the in vitro addition of the active metabolite of the P2Y12 receptor antagonist can be performed before such tests to exclude pharmacokinetic ‘resistance’.

In the case of abnormal results from non-specific tests, one should only use the term ‘elevated platelet reactivity despite treatment’. To detect the reason for this, more specific tests for a given drug should be used[29]. On the other hand, no specific method or agonist dose was mentioned in the detection of this phenomenon[12].

CLINICAL IMPORTANCE OF ANTIPLATELET RESISTANCE

Aspirin resistance

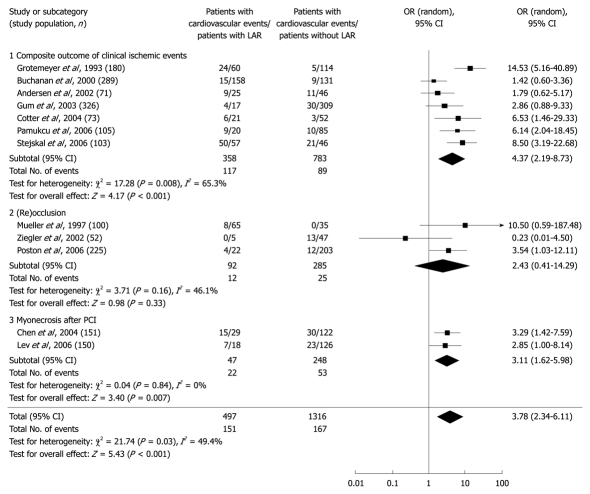

Despite lacking a definition of resistance and the association of platelet function tests, aspirin resistance seems to be associated with worsening clinical outcome. Based on a recent meta-analysis, the prevalence of laboratory aspirin resistance ranged from 5% to 65%. In the 12 studies eligible for pooling, comprising 1813 patients, the mean prevalence of laboratory aspirin resistance was 27%. The pooled odds ratio of all cardiovascular outcomes was 3.8 (95% CI: 2.3-6.1) for laboratory aspirin resistance. This systematic review and meta-analysis showed that patients biochemically identified as having laboratory aspirin resistance were more likely to also have “clinical resistance” to aspirin because they exhibited significantly higher risks of recurrent cardiovascular events compared with patients who were identified as (laboratory) aspirin sensitive[30] (Figure 2). This result was confirmed by another meta-analysis considering 20 studies totalling 2930 patients with cardiovascular disease. Overall, 810 patients (28%) were classified as aspirin resistant. A cardiovascular related event occurred in 41% of patients (OR 3.85, 95% CI: 3.08-4.80), death in 5.7% (OR 5.99, 95% CI: 2.28-15.72) and an acute coronary syndrome in 39.4% (OR 4.06, 95% CI: 2.96-5.56). Therefore, patients who were resistant to aspirin were at a greater risk of clinically important cardiovascular morbidity long term compared to patients who were sensitive to aspirin. This result was confirmed by other studies[31-33]. Interestingly, aspirin resistant patients did not benefit from other antiplatelet treatment[31].

Figure 2.

The clinical importance of aspirin resistance[30].

Clopidogrel resistance

We found only one meta-analysis focusing on clopidogrel resistance[12,32]. The authors identified 25 eligible studies that included a total of 3688 patients. Mean prevalence of clopidogrel nonresponsiveness was 21% (95% CI: 17%-25%) and was inversely correlated with time between clopidogrel loading and determination of nonresponsiveness and loading dose. The pooled odds ratio of cardiovascular outcomes was 8.0 (95% CI: 3.4-19.0). Therefore, laboratory clopidogrel nonresponsiveness could be found in approximately 1 in 5 patients undergoing PCI. Patients who were ex vivo labeled nonresponsive were likely to be also “clinically nonresponsive”, as they exhibited increased risks of worsened cardiovascular outcomes (Figure 3). Their results indicated that use of a 600-mg clopidogrel loading dose would reduce these risks, which needed to be confirmed in large prospective studies[34].

Figure 3.

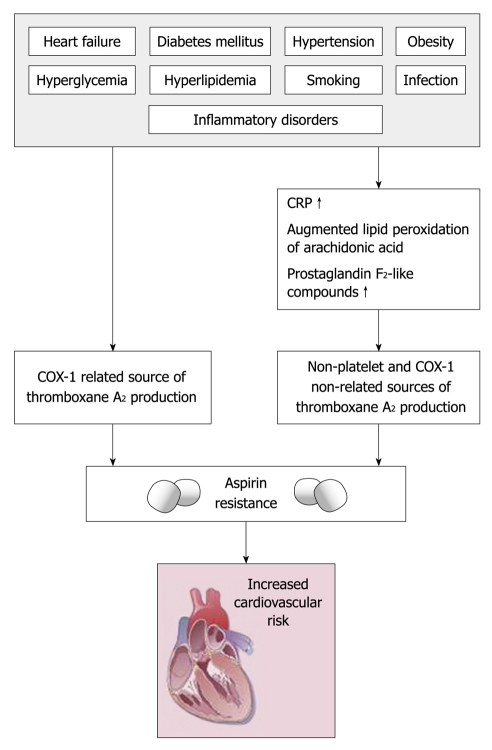

The possible background of aspirin resistance[38]. COX: Cyclooxygenase.

Very recently a comparison of platelet function tests in predicting clinical outcomes in patients undergoing coronary stent implantation was published to evaluate the capability of multiple platelet function tests to predict clinical outcomes. It was a prospective, observational, single-center cohort study of 1069 consecutive patients taking clopidogrel undergoing elective coronary stent implantation between December 2005 and December 2007. On-treatment platelet reactivity was measured in parallel by light transmittance aggregometry, VerifyNow P2Y12 and Plateletworks assays and the IMPACT-R and PFA-100 system (with the Dade PFA collagen/ADP cartridge and Innovance PFA P2Y). Cut-off values for high on-treatment platelet reactivity were established by receiver operating characteristic curve analysis. Of the platelet function tests assessed, only light transmittance aggregometry, VerifyNow, and Plateletworks were significantly associated with the primary end point. However, the predictive accuracy of these tests was only modest. None of the tests provided accurate prognostic information to identify low-risk patients at higher risk of bleeding following stent implantation[35].

RISK FACTORS OF ANTIPLATELET RESISTANCE

Aspirin resistance

Based on a number of large trials and meta-analyses, low doses of aspirin (75 to 150 mg/d) are comparatively safe and sufficient to inhibit platelet COX-1 and are as effective in preventing vascular events as higher aspirin doses (500 to 1500 mg/d)[4]. In some patients, the failure to suppress platelet COX-1 may be due to an inadequate dosage and reduced bioavailability of aspirin. In some cases, this may well relate to poor patient adherence (compliance), concurrent administration of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g. ibuprofen and indomethacin) and COX-2 inhibitors (which may compete with aspirin for platelet COX-1) or even a reduced absorption (or increased metabolism) of aspirin[36-38]. Such concerns have been highlighted in a recent meta-analysis of 6 studies focusing either on nonadherence or premature discontinuation of aspirin in over 50 000 patients at high risk of coronary artery disease, where a 3-fold increased risk of cardiac events (OR 3.14, 95% CI: 1.75-5.61, P = 0.0001) was related to nonadherence or the unjustified withdrawal of aspirin[39].

Age, weight and intake of proton pump inhibitors may also reduce the bioavailability of low-dose aspirin, mainly due to increased inactivation of ASA by gastrointestinal mucosal esterases and reduced absorption of active ASA[38]. Although low-dose aspirin may potentially be a cause of apparent aspirin resistance through reduced absorption, the use of higher doses of aspirin seems unjustifiable and is outweighed by an increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding[40]. However, in conditions accompanied by increased platelet turnover (e.g. acute coronary syndromes, coronary artery bypass grafting and other surgical procedures, acute or chronic infection and inflammation), a temporary increase of aspirin dose seems reasonable, albeit unproven[38]. Circumstantial evidence for this claim is available as aspirin resistance (as defined by PFA-100) and is twice as common in acute coronary syndromes complicated by pneumonia compared with those cases without infectious complications (90% vs 46%)[41]. In addition, there appears to be an independent association between CRP and aspirin resistance in these patients. Thus, in conditions that are associated with both infection and inflammation, nonplatelet sources of TxA2 production (e.g. monocytes, macrophages and endothelial cells) and up-regulation of the COX-2 enzyme coupled with increased levels of F2-isoprostanes may lead to uncontrolled thromboxane synthesis. Such COX-1-independent mechanisms are especially relevant to patients with diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, smoking and heart failure; all of which are associated with augmented lipid peroxidation of arachidonic acid and consequent overproduction of isoprostanes[38,42-49] (Figure 3).

In our recent work, 599 patients with chronic cardio- and cerebrovascular diseases (355 men, mean age 64 ± 11 years; 244 women, mean age 63 ± 10 years) who were taking aspirin 100-325 mg/d were examined[28]. Compared with aspirin-resistant patients, patients who demonstrated effective aspirin inhibition had a significantly lower plasma fibrinogen level (3.3 g/L vs 3.8 g/L, P < 0.05) and significantly lower RBC aggregation values (24.3 vs 28.2, P < 0.01). In addition, significantly more patients with effective aspirin inhibition were hypertensive (80% vs 62%, P < 0.05). Patients who had effective platelet aggregation were significantly more likely to be taking beta-adrenoceptor antagonists (75% vs 55%, P < 0.05) and ACE inhibitors (70% vs 50%, P < 0.05), whereas patients with ineffective platelet aggregation were significantly more likely to be taking HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) (52% vs 38%, P < 0.05). Use of statins remained an independent predictor of aspirin resistance even after adjustment for risk factors and medication use (OR 5.92, 95% CI: 1.83-16.9, P < 0.001). The importance of impaired hemorheological parameters in the development of aspirin resistance was confirmed by another study conducted by our workgroup and it was also confirmed by independent studies[50,51]. One potential explanation is when plasma fibrinogen levels increase red blood cells adhere and release ADP, which is a potential agonist of platelet aggregation. On the other hand, the aggregated red blood cells migrate in the center of blood flow, displacing other cells (platelets) in small vessels, so they can easily contact the endothelium. Furthermore, platelets from aspirin-resistant patients appeared to be more sensitive and activable by ADP. This hypersensitivity could provide a possible explanation for the so-called aspirin resistance, and this could justify therapeutic improvement with alternative antiplatelet agents[52].

Individual differences in the rate of platelet activation and reactivity markedly influence normal hemostasis and the pathological outcome of thrombosis. Such individual variability is largely determined by environmental and genetic factors. These are known to either hamper platelets' responses to agonists, and thereby mimic the pharmacological modulation of platelet function, or mask the therapy effect and sensitize platelets. We recently reviewed the possible role of different polymorphisms in the development of aspirin resistance, which may affect the efficacy of antiplatelet therapy. Variation in the way patients respond to aspirin may, in part, reflect heterogeneity in COX-1, COX-2, GP Ib α, GP Ia/IIa, GP IIb/IIIa, UGT1A6*2, P2Y(1), and P2Y(12) genotypes. On the other hand, very recently within 31 studies, 50 polymorphisms in 11 genes were investigated in 2834 subjects. The PlA1/A2 polymorphism in the GP IIIa platelet receptor was the most frequently investigated, with 19 studies in 1389 subjects. The PlA1/A2 variant was significantly associated with aspirin resistance when measured in healthy subjects (OR 2.36, 95% CI: 1.24-4.49, P = 0.009). Combining genetic data from all studies (comprising both healthy subjects and those with cardiovascular disease) reduced the observed effect size (OR 1.14, 95% CI: 0.84-1.54, P = 0.40). Moreover, the observed effect of a PlA1/A2 genotype varied depending on the methodology used for determining aspirin sensitivity/resistance. No significant association was found with aspirin resistance in four other investigated polymorphisms in the COX-1, GP Ia, P2Y1 or P2Y12 genes[53]. The lack of association among aspirin resistance and different gene haplotypes were confirmed by recently published studies[54,55].

Clopidogrel resistance

Clopidogrel is a prodrug that is metabolized by CYP450 into an active metabolite, which irreversibly inhibits binding of ADP to the P2Y12 receptor on the platelet[56,57]. Increased body mass index, hemoglobin A1c, C-peptide levels, and von Willebrand factor were significant factors of clopidogrel resistance[58]. Matetzky et al[59] reported that smokers were more likely to be responders. Gurbel et al[60] reported that patients with longer stents were more likely to be resistant to clopidogrel; however, Angiolillo et al[61] did not find a correlation between stent length and nonresponsiveness. Lev et al[62] found that 50% of their aspirin-resistant study participants were also resistant to clopidogrel. In their study, patients with dual drug resistance were more likely women (67.7% vs 26.9%, P = 0.02) with an elevated body mass index (33.8 ± 7.9 kg/m2 vs 29.7 ± 5 kg/m2, P = 0.03) than those with dual drug sensitivity. In our previous study, 157 patients with chronic cardio- and cerebrovascular diseases (83 males, mean age 61 ± 11 years, 74 females, 63 ± 13 years) taking 75 mg clopidogrel daily (not combined with aspirin) were included. Compared with clopidogrel-resistant patients [35 patients (22%)], patients who demonstrated effective clopidogrel inhibition had a significantly lower body mass index (26.1 kg/m2 vs 28.8 kg/m2, P < 0.05). Patients with ineffective platelet aggregation were significantly more likely to be taking benzodiazepines (25% vs 10%) and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (28% vs 12%, P < 0.05). After an adjustment to the risk factors and medications BMI (OR 2.62, 95% CI: 1.71-3.6, P < 0.01), benzodiazepines (OR 5.83, 95% CI: 2.53-7.1, P < 0.05) and SSRIs (OR 5.22, 95% CI: 2.46-6.83, P < 0.05) remained independently associated with clopidogrel resistance[27].

Concurrent medication use may interfere with the ability of clopidogrel to decrease platelet reactivity. Gurbel et al[60] reported that high doses of calcium-channel blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors possibly contribute to a decreased response to clopidogrel. Studies that have evaluated clopidogrel resistance and statins have not been uniformly reproducible either. Atorvastatin is the most frequently studied statin in clopidogrel trials. Lau et al[63] showed that atorvastatin promoted clopidogrel resistance at 10 mg, 20 mg and 40 mg (P = 0.027, P = 0.002 and P = 0.001, respectively). On the other hand, Mitsios et al[64] reported that daily doses of 10 mg of atorvastatin did not result in a decreased clopidogrel response over a 5-wk period. In the same study, clopidogrel significantly attenuated platelet aggregation in 3 different concentrations of ADP in the presence of no statin, atorvastatin, or pravastatin (P < 0.01, P < 0.01, and P < 0.02 at 2 μmol, 5 μmol, and 10 μmol of ADP, respectively). Also, Müller et al[65] reported that antiplatelet activity was not reduced in patients who were given a 600 mg loading dose of clopidogrel and 1 of these statins: atorvastatin, fluvastatin, lovastatin, pravastatin, simvastatin or cerivastatin. There is some evidence supporting a possible pharmacokinetic interaction between statins and the anti-platelet drug clopidogrel. In particular, it has been suggested that this interaction is more likely with lipophilic statins, which share the same CYP450 metabolizing isoenzyme (Table 1[66-72]). However, discordance between ex vivo data, which points in favour of an interaction, and the majority of clinical studies, which failed to detect a clinically relevant effect, has to be acknowledged[72].

Table 1.

The role of clopidogrel and statin interaction based on recent clinical trials

| Study | Sample size | Comparison | Primary end point | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CREDO substudy[66] | 1159 | Post hoc analysis categorizing baseline statin use to those predominantly metabolized by CYP3A4 or not | 1 yr composite endpoint of death, myocardial infarction and stroke | No detrimental effect |

| GRACE[67] | 15 693 | Four groups: group I received aspirin alone, group II aspirin and clopidogrel, group III aspirin and statin and group IV aspirin, clopidogrel and statin | 6 mo mortality adjusted for baseline characteristics, in-hospital medications and procedures, re-hosp and revascularization | No detrimental effect |

| MITRA plus[68] | 2086 | Two groups: group I received atorvastatin and clopidogrel, group II other statins (both lipophilic and non-lipophilic) and clopidogrel | Long-term mortality | No detrimental effect |

| Mukherjee et al[69] | 1651 | Two groups: group I received CYP3A4 statin plus clopidogrel, group II received non-CYP3A4 statin plus clopidogrel | In-hospital and 6 mo mortality | No detrimental effect |

| Brophy et al[70] | 2927 | Two groups: group I received clopidogrel and atorvastatin, group II clopidogrel alone | 30-d rates of adverse cardiovascular events (composite of death, myocardial infarction, unstable angina, stroke or transient ischaemic attack and repeat revascularization procedures) | Worse outcome associated with statins |

| CHARISMA substudy[71] | 10 078 | Post hoc analysis categorizing baseline statin use to those predominantly metabolized by CYP3A4 or not | Composite of myocardial infarction, stroke or cardiovascular death at median follow-up of 28 mo | No detrimental effect |

Lau et al[73] reiterated the contribution of CYP3A4 activity to the phenomenon of clopidogrel resistance. A significant inverse correlation was observed between platelet aggregation and CYP3A4 activity as measured by the erythromycin breath test in healthy volunteers. The investigators also demonstrated that by enhancing CYP3A4 activity with rifampin in 10 healthy volunteers, 3 initial non-responders (platelet inhibition < 10%) and one low responder (platelet inhibition between 10% to 29%) to clopidogrel exhibited enhanced platelet inhibition that met the definition of a clopidogrel responder (platelet inhibition > 30%). This was in concordance with our results and later articles[27,74].

Proton pump inhibitors are among the competitive inhibitors of CYP450 2C19, the other major isoenzyme involved in the activation of clopidogrel. In a prospective, randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled study involving patients undergoing elective coronary artery stenting who received clopidogrel, co-administration of the proton pump inhibitor omeprazole was associated with decreased CYP450 2C19-dependent inhibition of platelet aggregation (i.e. a decreased platelet inhibitory effect of clopidogrel)[75]. Juurlink et al[76], using a population-based nested case-control study design, reported on their investigation of the potential association of a CYP450 2C19-dependent drug-drug interaction between clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors and the risk of readmission to hospital because of myocardial infarction among patients 66 years or older who received clopidogrel therapy following hospital discharge after acute myocardial infarction. Patients who experienced reinfarction within 90 d after discharge were more likely than event-free patients in the control group to have received concomitant therapy with clopidogrel and proton pump inhibitors. The authors estimated that, compared with no treatment, CYP450 2C19-inhibiting proton pump inhibitors were collectively associated with a 40% relative increase in the risk of recurrent myocardial infarction. An exception was the proton pump inhibitor pantoprazole, which did not show the above associations[76,77]. On the other hand, recent trials and meta-analysis could not confirm their findings[77-79]. At this point, concomitant therapy with a CYP450 2C19-inhibiting proton pump inhibitor and clopidogrel should be administered when there is a sound clinical indication. For example, patients taking clopidogrel and warfarin therapy who require a proton pump inhibitor may need to avoid pantoprazole, since warfarin is metabolized primarily by CYP450 2C9. Alternatively, treatment strategies may be considered that use drugs not dependent on the CYP450 2C19 isoenzyme, such as pantoprazole and H2-receptor antagonists[80].

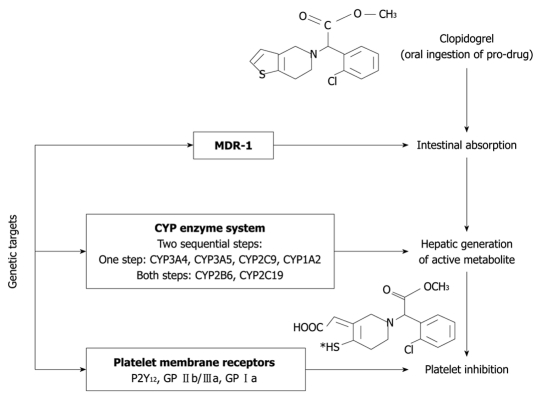

Variation in the way patients respond to clopidogrel may in part reflect heterogeneity in GP IIb/IIIa, P2Y1, P2Y12, CYP2C9, CYP3A4 and CYP3A5 genotypes[11,81,82] (Figure 4). The very recently conducted FAST-MI study (French Registry of Acute ST-Elevation and Non-ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction study) and the TRITON-TIMI 38 study (Trial to Assess Improvement in Therapeutic Outcomes by Optimizing Platelet Inhibition with Prasugrel-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 38) demonstrated a greater than 3-fold increase in the risk of adverse cardiovascular events among patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention who were homozygous or heterozygous for any of the CYP2C19 alleles known to result in a nonfunctional protein (CYP2C19*2, *3, *4 and *5), as compared with patients who had the wild-type CYP2C19*1 allele[83,84].

Figure 4.

Possible genetical background of clopidogrel resistance[82]. GP: Glycoprotein.

TREATMENT OF ANTIPLATELET RESISTANCE

Possible treatment of aspirin resistance

There are only few studies examining the possible treatment of aspirin resistance[10,11]. Epidemiological studies suggest that Mediterranean diets are associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease. It has been proposed that resveratrol is one of the most important dietary constituents involved in vasculoprotection. Stef et al[85] in an in vitro study including 50 high-risk cardiac patients showed that resveratrol effectively inhibited collagen- and epinephrine-induced aggregation of platelets from aspirin resistant patients, which may contribute to its cardioprotective effects in this population.

In the last decade, numerous studies have revealed a central role for NAD(P)H oxidases in cardiovascular pathophysiology[86]. Importantly, there is increasing evidence that NAD(P)H oxidase(s) play an important role in platelet aggregation[85]. In another in vitro study Stef et al[86] also showed that inhibition of NAD(P)H oxidase effectively suppressed collagen and epinephrine-induced aggregation of platelets from aspirin-resistant patients, which may represent a novel pharmacological target for cardioprotection in high-risk cardiac patients.

Aprotinin, a drug effective in limiting blood loss in patients undergoing surgery, was first approved in the United States in 1993 for use in high-risk patients needing coronary artery surgery. Aspirin is the only drug proven to reduce saphenous vein graft failure, but aspirin resistance (ASA-R) frequently occurs after off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting (OPCAB). Poston et al[87] proposed that thrombin production during OPCAB stimulates this acquired ASA-R. They found that ASA-R is a common post-OPCAB event whose frequency may be reduced by intraoperative use of aprotinin, possibly via TF and thrombin suppression. Improved perioperative PLT function after OPCAB may also inadvertently enhance the clinical relevance of these potential antithrombotic effects.

A previous in vitro study showed the association between increased platelet response to ADP and aspirin resistance[88]. Eikelboom et al[89] raised the possibility that the clinical benefits of adding clopidogrel to aspirin may be greatest in patients whose platelets are least inhibited by aspirin. In another study, the addition of clopidogrel to aspirin provided greater inhibition of platelets and could overcome aspirin resistance[90]. Pamukcu et al[91,92] found an association between aspirin resistance and poor clinical outcome in AICS patients and also showed that the prevalence of major acute cardiac events in patients who were on clopidogrel treatment for 12 mo. Poor clinical outcomes were significantly lower compared to those who were on a clopidogrel treatment for the first 6 mo. In another study, aspirin resistance was also associated with worsening clinical outcomes, but the poor outcomes increased just after cessation of clopidogrel therapy. On the other hand, in their meta-analysis, Krasopoulos et al[31] showed that concomitant therapy with clopidogrel or tirofiban (an inhibitor of platelet GP IIb/IIIa), or both, provided no benefit to those patients identified as aspirin resistant. Further studies are needed to clarify their findings.

Very recently, Tirnaksiz et al[93] suggested a possible effect of atorvastatin therapy on aspirin resistance and it was confirmed by another study[94].

Biondi-Zoccai et al[39] undertook a systematic review to appraise the hazards inherent to aspirin withdrawal or non-compliance in subjects at risk for or with CAD. They concluded that non-compliance or withdrawal of aspirin treatment has ominous prognostic implication in subjects with or at moderate-to-high risk for CAD.

Possible treatment of clopidogrel resistance

The American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions guidelines state that “in patients in whom stent thrombosis may be catastrophic or lethal”. platelet aggregation studies may be considered and the dose of clopidogrel increased to 150 mg/d if less than 50% inhibition of platelet aggregation is demonstrated.’’ This is a Class IIb, level C recommendation, indicating that there is disagreement over whether the intervention is considered beneficial, and that the recommendation reflects only consensus opinion, not data from randomized clinical trials. Finally, the method to assess platelet inhibition is not described[15,95]. We collected articles examining the possible association between laboratory and clinical clopidogrel resistance based on different platelet function assays (Tables 2, 3 and 4)[59,62,96-108].

Table 2.

Clinical studies based on optical aggregometry

| Study | Method | Patient population | Dosage | Adjunct antiplatelet therapy | No. of patients (clopidogrel sensitive/clopidogrel resistant) | Outcome measures | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geisler et al[96] | Optical aggregometry | PCI | 600 mg | No | 363 (341/22) | Cardiovascular event within a 3-mo follow-up | Low responder had a significantly higher risk of major cardiovascular events (22.7 vs 5.6%, OR, 4.9, 95% CI: 1.66–14.96, P = 0.004) |

| Buonamici et al[97] | Optical aggregometry | PCI | Loading dose of clopidogrel followed by 75 mg daily | GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor, 325 mg aspirin | 804 (699/105) | Stent thrombosis during a 6-mo follow-up | The predictors of stent thrombosis was: nonresponsiveness to clopidogrel (HR 3.08, 95% CI: 1.32-7.16, P = 0.009) |

| Müller et al[98] | Optical aggregometry | PCI | 600 mg loading dose followed by 75 mg daily | 100 mg aspirin | 105 (90/15) | Their data showed that 5 patients who developed a stent thrombosis were non-responders | |

| Wenaweser et al[99] | Optical aggregometry | PCI | 300 mg loading dose followed by 75 mg daily | 100 mg aspirin | 82 (60/21) | Presence of stent thrombosis | Combined ASA and clopidogrel resistance was more prevalent in patients with stent thrombosis (52%) compared with controls (38%, P = NS) and volunteers (11%, P < 0.05) |

| Soffer et al[100] | Optical aggregometry | PCI | 450 mg clopidogrel before the procedure | 325 mg aspirin | 72 (divided into two groups based on angina classification) | Angina class | In multivariate analysis, higher angina class was independently associated with lower inhibition of platelet aggregation (P = 0.018) |

| Buonamici et al[97] | Optical aggregometry | PCI | 600 mg loading dose followed by 75 mg daily | GP IIb/IIIa inhibitor, 325 mg aspirin | 804 (699/105) | Stent thrombosis | The incidence of stent thrombosis was 8.6% in nonresponders and 2.3% in responders (P < 0.001) |

Table 3.

Clinical studies based on optical aggregometry combined with another method

| Study | Method | Patient population | Dosage | Adjunct antiplatelet therapy | No. of patients (clopidogrel sensitive/clopidogrel resistant) | Outcome measures | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lev et al[62] | Optical aggregometry, RPFA | Elective PCI | 300 mg clopidogrel followed by 75 mg daily | No | 150 (114/36) | Markers of myonecrosis | Myonecrosis occurred more frequently in clopidogrel-resistant vs clopidogrel-sensitive patients (32.4% vs 17.3%, P = 0.06) |

| Bliden et al[101] | Optical aggregometry, TEG | PCI | Previously 75 mg daily, 300-600 mg loading dose followed by 75 mg daily | 325 mg | 100 | Cardiovascular event/revascularisation | Patients receiving chronic clopidogrel therapy who exhibit high on-treatment ADP-induced platelet aggregation are at increased risk for postprocedural ischemic events |

| Gurbel et al[102] | Optical aggregometry, TEG | PCI | 300-600 mg loading dose followed by 75 mg daily | 325 mg aspirin | 192 (154 patients without and 38 patients with ischaemic events) | Cardiovascular outcome/revascularisation | Posttreatment ADP-induced aggregation by LTA (63% ± 12% vs 56% ± 15%, P = 0.02) was significantly higher) in patients with events (n = 38) |

| Matetzky et al[59] | Optical aggregometry, cone and platelet analyzer | PCI | 300 mg clopidogrel followed by 75 mg daily | 300 mg of aspirin followed by 200 mg/d | 60 (patients were stratified into 4 quartiles) | Cardiovascular event | Whereas 40% of patients in the first quartile sustained a recurrent cardiovascular event, only 1 patient (6.7%) in the second quartile and none in the third and fourth quartiles suffered a cardiovascular event (P = 0.007) |

Table 4.

Clinical studies based on optical aggregometry combined with activation-dependent changes on the platelet surface or with vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein phosphorylation

| Study | Method | Patient population | Dosage | Adjunct antiplatelet therapy | No. of patients (clopidogrel sensitive/clopidogrel resistant) | Outcome measures | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bonello et al[103] | VASP phosphorylation | PCI | 300 mg loading dose followed by 75 mg daily | 100 mg aspirin | 144 patients were divided into quintiles according to PRI | Cardiovascular events | Patients in quintile 1 of VASP analysis had a significantly lower risk of MACE as compared with those among the four higher quintiles (0 vs 21, P < 0.01) |

| Barragan et al[104] | VASP phosphorylation | PCI | Ticlopidin or clopidogrel | 250 mg aspirin | 36 (20 healthy volunteers and 16 stented patients) | Presence of stent thrombosis | VASP phosphorylation analysis may be useful for the detection of coronary SAT |

| Serebruany et al[105] | Optical aggregometry, and whole blood flow cytometry | AICS or ischaemic stroke | 75 mg | 81-325 mg aspirin | 359 (359/0) | Lack of nonresponse | |

| Gurbel et al[106] | Optical aggregometry, GP IIb/IIIa receptor, VASP phosphorylation | PCI | 300-600 mg loading dose followed by 75 mg daily | No information | 120 (20 patients with stent thrombosis and 120 patients without stent thrombosis | Stent thrombosis | The SAT patients had significantly higher mean platelet reactivity than those without SAT by all measurements |

| Cuisset et al[107] | Optical aggregometry, P-selectin | NSTEMI followed by PCI | 300-600 mg loading dose followed by 75 mg daily | 160 mg aspirin | 106 (94 patients without and 12 with cardiovascular event) | Cardiovascular event | Low responders to dual antiplatelet therapy had increased risk of recurrent CV events |

| Cuisset et al[108] | Optical aggregometry, P-selectin | NSTEMI followed by PCI | 300-600 mg loading dose followed by 75 mg daily | 160 mg aspirin | 392 (146 patients with 300 mg loading dose clopidogrel and 300 patients with 600 mg loading dose of clopidogrel) | Cardiovascular event | The ADP-induced platelet aggregation and expression of P-selectin were significantly lower in patients receiving 600 mg than in those receiving 300 mg. During the 1-mo follow-up, 18 CV events (12%) occurred in the 300-mg group vs 7 (5%) in the 600-mg group (P = 0.02); this difference was not affected by adjustment for conventional CV risk factors (P = 0.035) |

Bonello et al[109] concluded from a prospective, randomized, multicenter study that clopidogrel resistance was defined as a VASP index of more than 50% after a 600-mg loading dose. Patients with clopidogrel resistance undergoing coronary stenting were randomized to a control group or to the VASP-guided group, in which patients received additional bolus clopidogrel to decrease the VASP index below 50%. A total of 162 patients were included. The control (n = 84) and VASP-guided groups (n = 78) had similar demographic, clinical and biological characteristics. In the VASP-guided group, dose adjustment was efficient in 67 patients (86%) and VASP index was significantly decreased (from 69.3 ± 10 to 37.6 ± 13.8, P < 0.001). Eight major adverse cardiac events (5%) were recorded during the 1-mo follow-up, with a significantly lower rate in the VASP-guided group compared with the control group (0% vs 10%, P = 0.007). There was no difference in the rate of major and minor bleeding (5% vs 4%, P = 1). This was the first study to suggest that adjusting the clopidogrel loading dose according to platelet monitoring using the VASP index is safe and may significantly improve the clinical outcome after PCI in patients with clopidogrel resistance despite a first 600 mg loading dose.

A total of 119 patients undergoing PCI were blindly randomized in a 2:1 fashion to receive clopidogrel loading 600 mg on the table immediately before PCI and 75 mg 2 times per day for 1 mo (high-dose group) vs standard dosing (300 mg loading and 75 mg/d; low-dose group)[110]. Platelet aggregation was measured using light transmission aggregometry at baseline, 4 h and 30 d. The composite of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction and target vessel revascularization was studied at 30 d in addition to major and minor bleeding. Baseline characteristics and baseline platelet aggregation were similar in the 2 groups. Percent inhibitions of platelet activity were 41% and 27% in the high-dose group vs 19% and 10% in the low-dose group at 4 h and 30 d (P = 0.046 and 0.047, respectively). Composite clinical end points were 10.3% in the high-dose group and 23.8% in the low-dose group (P = 0.04). No difference was noted in major or minor bleeding. In conclusion, a higher loading and maintenance dose of clopidogrel in patients undergoing PCI resulted in superior platelet inhibition and decreased cardiovascular events without increasing bleeding complications.

On the other hand, the use of a 150 mg maintenance dose of clopidogrel in patients with type 2 diabetes with < 50% platelet inhibition was associated with enhanced antiplatelet effects, however, the antiplatelet effects achieved were nonuniform, and a considerable number of patients persisted with inadequate platelet inhibition[111].

Ticlopidine could be an alternative agent in the treatment of clopidogrel resistance as previous studies have suggested[112,113]. A recent case report presented three patients with acute stent thrombosis showing biological non-responsiveness to clopidogrel, despite overdosing to 150 mg/d and a sufficient duration of the treatment. Platelet P2Y12 inhibition was finally obtained with a standard regimen of ticlopidine. The effects of possible poor compliance would appear limited because each patient was his/her own control and was under surveillance in hospital[114]. This replacement should of course be subject to hematological monitoring in order to avoid any serious neutropenia.

Wolak et al[115] studied 1519 consecutive patients who underwent 2020 stent implantations and were discharged on dual antiplatelet regimens of either aspirin and ticlopidine or aspirin and clopidogrel given for up to 4 wk. Thrombotic stent occlusion (TSO) was defined as ST elevation myocardial infarction in the stented artery territory associated with angiographic demonstration of complete stent occlusion. Mortality follow up was obtained for all patients by linkage to the Population Register. Follow up duration was 12 mo. TSO occurred in 37 stents at a median of 29 d post procedure. Of these cases, six occurred in the ticlopidine group (0.7%) and 31 in the clopidogrel group (2.8%, P < 0.01). The median time to TSO was 34 d and 28 d in ticlopidine and clopidogrel treated patients, respectively (P < 0.01). After controlling for multiple demographic, clinical and angiographic variables clopidogrel (vs ticlopidine) treatment remained the sole predictor of TSO (OR 5.4, 95% CI: 1.2-24.1, P = 0.028). Of even more concern, clopidogrel treatment was associated with an increased risk of 1 year mortality (OR 1.8, 95% CI: 1.2-2.8).

Newer drugs may overcome the limitations of current antiplatelet drugs. Prasugrel is a third-generation thienopyridine that is not as dependent as clopidogrel on biotransformation to an active metabolite. In preclinical studies, it was shown to have greater potency and achieve more rapid platelet inhibition than clopidogrel when given orally[116]. The JUMBO-TIMI trial found prasugrel to have a comparable safety profile to clopidogrel[117]. However, the recent TRITON TIMI-38 trial found that prasugrel reduced ischemic events in an ACS population undergoing PCI, at the cost of increased major bleeding. Those assigned to clopidogrel received a 300 mg loading dose immediately before or during PCI, whereas 600 mg is now more commonly used clinically as it may be more effective. Although this raised the question of dose equivalence, platelet function analysis in PRINCIPLE-TIMI 44 has shown that the dose of prasugrel used in TRITON leads to greater platelet inhibition than clopidogrel at the higher loading and maintenance doses[118]. Subgroup analysis of TRITON suggested prasugrel may have the greatest benefit over clopidogrel in the highest-risk patients, such as those with diabetes.

Based on very recent trials, among persons treated with clopidogrel, carriers of a reduced-function CYP2C19 allele had significantly lower levels of the active metabolite of clopidogrel, diminished platelet inhibition and a higher rate of major adverse cardiovascular events, including stent thrombosis, than did noncarriers[83,84]. On the other hand, common functional CYP genetic variants do not affect active drug metabolite levels, inhibition of platelet aggregation, or clinical cardiovascular event rates in persons treated with prasugrel. These pharmacogenetic findings are in contrast to observations with clopidogrel, which may explain, in part, the different pharmacological and clinical responses to the two medications[119].

Ticagrelor is an oral, reversible, direct-acting inhibitor of the ADP receptor P2Y12 that has a more rapid onset and more pronounced platelet inhibition than clopidogrel[120]. In patients who have an acute coronary syndrome with or without ST-segment elevation, treatment with ticagrelor as compared with clopidogrel significantly reduced the rate of death from vascular causes, myocardial infarction or stroke without an increase in the rate of overall major bleeding but with an increase in the rate of non-procedure-related bleeding[121].

In a very recent trial, ticagrelor therapy overcame nonresponsiveness to clopidogrel, and its antiplatelet effect is the same in responders and nonresponders. Nearly all clopidogrel nonresponders and responders treated with ticagrelor had platelet reactivity below the cut off points associated with ischemic risk[122].

CONCLUSION

We previously reviewed the possible clinical importance of aspirin and clopidogrel resistance in some aspects[10,11]. The current review is an updated article of the topic (containing the possible risk factors of this phenomenon) including the clinical consequences of clopidogrel resistance.

In its broadest sense, resistance refers to the continued occurrence of ischaemic events despite adequate antiplatelet therapy and compliance. The lack of a standard definition of resistance, as well as the lack of a standard diagnostic modality, has hampered the field in identifying and treating this clinical entity. Attempts have been made to develop a more meaningful definition with the goal of correlating laboratory tests with clinical outcomes, but there is no current definition that unifies the biochemical and clinical expression of failed treatment.

On the other hand, despite the presence of statistical heterogeneity among studies, likely reflecting methodological differences, almost all included studies have suggested a positive association between the risk of cardiovascular events and laboratory antiplatelet nonresponsiveness.

The optimal treatment of resistance is also unclear. These results suggest that a new era of individualized antiplatelet therapy may arise with routine measurements of platelet activity in the same way that cholesterol, blood pressure and blood sugar are followed, thus improving care for millions of people.

Footnotes

Supported by The University of Pecs (PTE AOK KA-34039-16/2009)

Peer reviewers: Pietro A Modesti, MD, PhD, Professor of Internal Medicine, Department Critical Care Medicine, University of Florence, Viale Morgagni 85, 50124 Florence, Italy; Stephen Wildhirt, MD, PhD, Associate Clinical Professor of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Department of Cardiothoracic- and Vascular Surgery, Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, Langenbeckstrasse 1, 55131 Mainz, Germany; Arshad Ali, MD, FACC, FSCAI, MRCP, Associate Medical Director, Kentucky Heart Foundation, Kings Dauhters Medical Center, Suite 10, Ashland, KY 41101, United States

S- Editor Cheng JX L- Editor Lutze M E- Editor Zheng XM

References

- 1.Reilly IA, Doran JB, Smith B, FitzGerald GA. Increased thromboxane biosynthesis in a human preparation of platelet activation: biochemical and functional consequences of selective inhibition of thromboxane synthase. Circulation. 1986;73:1300–1309. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.73.6.1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cola C, Brugaletta S, Martín Yuste V, Campos B, Angiolillo DJ, Sabaté M. Diabetes mellitus: a prothrombotic state implications for outcomes after coronary revascularization. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2009;5:101–119. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.s4248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maree AO, Fitzgerald DJ. Variable platelet response to aspirin and clopidogrel in atherothrombotic disease. Circulation. 2007;115:2196–2207. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.675991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hankey GJ, Eikelboom JW. Aspirin resistance. Lancet. 2006;367:606–617. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nieswandt B, Watson SP. Platelet-collagen interaction: is GPVI the central receptor? Blood. 2003;102:449–461. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-12-3882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gawaz M. Role of platelets in coronary thrombosis and reperfusion of ischemic myocardium. Cardiovasc Res. 2004;61:498–511. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Andrews RK, Gardiner EE, Shen Y, Berndt MC. Platelet interactions in thrombosis. IUBMB Life. 2004;56:13–18. doi: 10.1080/15216540310001649831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Awtry EH, Loscalzo J. Aspirin. Circulation. 2000;101:1206–1218. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.10.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma RK, Reddy HK, Singh VN, Sharma R, Voelker DJ, Bhatt G. Aspirin and clopidogrel hyporesponsiveness and nonresponsiveness in patients with coronary artery stenting. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2009;5:965–972. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.s6787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pusch G, Feher G, Kotai K, Tibold A, Gasztonyi B, Feher A, Papp E, Lupkovics G, Szapary L. Aspirin resistance: focus on clinical endpoints. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2008;52:475–484. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e31818eee5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feher G, Feher A, Pusch G, Lupkovics G, Szapary L, Papp E. The genetics of antiplatelet drug resistance. Clin Genet. 2009;75:1–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2008.01105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feher G, Pusch G, Szapary L. Optical aggregometry and aspirin resistance. Acta Neurol Scand. 2009;119:139; author reply 140. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2008.01067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cattaneo M. Aspirin and clopidogrel: efficacy, safety, and the issue of drug resistance. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:1980–1987. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000145980.39477.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eikelboom JW, Hirsh J, Weitz JI, Johnston M, Yi Q, Yusuf S. Aspirin-resistant thromboxane biosynthesis and the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, or cardiovascular death in patients at high risk for cardiovascular events. Circulation. 2002;105:1650–1655. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000013777.21160.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Braunwald E, Angiolillo D, Bates E, Berger PB, Bhatt D, Cannon CP, Furman MI, Gurbel P, Michelson AD, Peterson E, et al. Assessing the current role of platelet function testing. Clin Cardiol. 2008;31:I10–I16. doi: 10.1002/clc.20361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kotzailias N, Elwischger K, Sycha T, Rinner W, Quehenberger P, Auff E, Müller C. Clopidogrel-induced platelet inhibition cannot be detected by the platelet function analyzer-100 system in stroke patients. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2007;16:199–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marcucci R, Paniccia R, Antonucci E, Poli S, Gori AM, Valente S, Giglioli C, Lazzeri C, Prisco D, Abbate R, et al. Residual platelet reactivity is an independent predictor of myocardial injury in acute myocardial infarction patients on antiaggregant therapy. Thromb Haemost. 2007;98:844–851. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lordkipanidzé M, Pharand C, Schampaert E, Turgeon J, Palisaitis DA, Diodati JG. A comparison of six major platelet function tests to determine the prevalence of aspirin resistance in patients with stable coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:1702–1708. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gurbel PA, Bliden KP, DiChiara J, Newcomer J, Weng W, Neerchal NK, Gesheff T, Chaganti SK, Etherington A, Tantry US. Evaluation of dose-related effects of aspirin on platelet function: results from the Aspirin-Induced Platelet Effect (ASPECT) study. Circulation. 2007;115:3156–3164. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.675587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harrison P, Segal H, Silver L, Syed A, Cuthbertson FC, Rothwell PM. Lack of reproducibility of assessment of aspirin responsiveness by optical aggregometry and two platelet function tests. Platelets. 2008;19:119–124. doi: 10.1080/09537100701771736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chakroun T, Addad F, Abderazek F, Ben-Farhat M, Hamdi S, Gamra H, Hassine M, Ben-Hamda K, Samama MM, Elalamy I. Screening for aspirin resistance in stable coronary artery patients by three different tests. Thromb Res. 2007;121:413–418. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2007.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karon BS, Wockenfus A, Scott R, Hartman SJ, McConnell JP, Santrach PJ, Jaffe AS. Aspirin responsiveness in healthy volunteers measured with multiple assay platforms. Clin Chem. 2008;54:1060–1065. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.101014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lordkipanidzé M, Pharand C, Nguyen TA, Schampaert E, Palisaitis DA, Diodati JG. Comparison of four tests to assess inhibition of platelet function by clopidogrel in stable coronary artery disease patients. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2877–2885. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dyszkiewicz-Korpanty A, Olteanu H, Frenkel EP, Sarode R. Clopidogrel anti-platelet effect: an evaluation by optical aggregometry, impedance aggregometry, and the platelet function analyzer (PFA-100) Platelets. 2007;18:491–496. doi: 10.1080/09537100701280654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Velik-Salchner C, Maier S, Innerhofer P, Streif W, Klingler A, Kolbitsch C, Fries D. Point-of-care whole blood impedance aggregometry versus classical light transmission aggregometry for detecting aspirin and clopidogrel: the results of a pilot study. Anesth Analg. 2008;107:1798–1806. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e31818524c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malinin AI, Ong S, Makarov LM, Petukhova EY, Serebruany VL. Platelet inhibition beyond conventional antiplatelet agents: expanding role of angiotensin receptor blockers, statins and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60:993–1002. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2006.01063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feher G, Koltai K, Alkonyi B, Papp E, Keszthelyi Z, Kesmarky G, Toth K. Clopidogrel resistance: role of body mass and concomitant medications. Int J Cardiol. 2007;120:188–192. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2006.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feher G, Koltai K, Papp E, Alkonyi B, Solyom A, Kenyeres P, Kesmarky G, Czopf L, Toth K. Aspirin resistance: possible roles of cardiovascular risk factors, previous disease history, concomitant medications and haemorrheological variables. Drugs Aging. 2006;23:559–567. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200623070-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuliczkowski W, Witkowski A, Polonski L, Watala C, Filipiak K, Budaj A, Golanski J, Sitkiewicz D, Pregowski J, Gorski J, et al. Interindividual variability in the response to oral antiplatelet drugs: a position paper of the Working Group on antiplatelet drugs resistance appointed by the Section of Cardiovascular Interventions of the Polish Cardiac Society, endorsed by the Working Group on Thrombosis of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2009;30:426–435. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Snoep JD, Hovens MM, Eikenboom JC, van der Bom JG, Huisman MV. Association of laboratory-defined aspirin resistance with a higher risk of recurrent cardiovascular events: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1593–1599. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.15.1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Krasopoulos G, Brister SJ, Beattie WS, Buchanan MR. Aspirin "resistance" and risk of cardiovascular morbidity: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2008;336:195–198. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39430.529549.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sofi F, Marcucci R, Gori AM, Abbate R, Gensini GF. Residual platelet reactivity on aspirin therapy and recurrent cardiovascular events--a meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2008;128:166–171. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Crescente M, Di Castelnuovo A, Iacoviello L, de Gaetano G, Cerletti C. PFA-100 closure time to predict cardiovascular events in aspirin-treated cardiovascular patients: a meta-analysis of 19 studies comprising 3,003 patients. Thromb Haemost. 2008;99:1129–1131. doi: 10.1160/TH08-03-0130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Snoep JD, Hovens MM, Eikenboom JC, van der Bom JG, Jukema JW, Huisman MV. Clopidogrel nonresponsiveness in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention with stenting: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am Heart J. 2007;154:221–231. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Breet NJ, van Werkum JW, Bouman HJ, Kelder JC, Ruven HJ, Bal ET, Deneer VH, Harmsze AM, van der Heyden JA, Rensing BJ, et al. Comparison of platelet function tests in predicting clinical outcome in patients undergoing coronary stent implantation. JAMA. 2010;303:754–762. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.FitzGerald GA. Parsing an enigma: the pharmacodynamics of aspirin resistance. Lancet. 2003;361:542–544. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12560-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schwartz KA. Aspirin resistance: a review of diagnostic methodology, mechanisms, and clinical utility. Adv Clin Chem. 2006;42:81–110. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2423(06)42003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gasparyan AY, Watson T, Lip GY. The role of aspirin in cardiovascular prevention: implications of aspirin resistance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:1829–1843. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.11.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Biondi-Zoccai GG, Lotrionte M, Agostoni P, Abbate A, Fusaro M, Burzotta F, Testa L, Sheiban I, Sangiorgi G. A systematic review and meta-analysis on the hazards of discontinuing or not adhering to aspirin among 50,279 patients at risk for coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2667–2674. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Campbell CL, Smyth S, Montalescot G, Steinhubl SR. Aspirin dose for the prevention of cardiovascular disease: a systematic review. JAMA. 2007;297:2018–2024. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.18.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Modica A, Karlsson F, Mooe T. Platelet aggregation and aspirin non-responsiveness increase when an acute coronary syndrome is complicated by an infection. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:507–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ferroni P, Basili S, Falco A, Davì G. Platelet activation in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Thromb Haemost. 2004;2:1282–1291. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.00836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Anfossi G, Trovati M. Pathophysiology of platelet resistance to anti-aggregating agents in insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes: implications for anti-aggregating therapy. Cardiovasc Hematol Agents Med Chem. 2006;4:111–128. doi: 10.2174/187152506776369908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Watala C. Blood platelet reactivity and its pharmacological modulation in (people with) diabetes mellitus. Curr Pharm Des. 2005;11:2331–2365. doi: 10.2174/1381612054367337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Davi G, Alessandrini P, Mezzetti A, Minotti G, Bucciarelli T, Costantini F, Cipollone F, Bon GB, Ciabattoni G, Patrono C. In vivo formation of 8-Epi-prostaglandin F2 alpha is increased in hypercholesterolemia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:3230–3235. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.11.3230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reilly M, Delanty N, Lawson JA, FitzGerald GA. Modulation of oxidant stress in vivo in chronic cigarette smokers. Circulation. 1996;94:19–25. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Polidori MC, Praticó D, Savino K, Rokach J, Stahl W, Mecocci P. Increased F2 isoprostane plasma levels in patients with congestive heart failure are correlated with antioxidant status and disease severity. J Card Fail. 2004;10:334–338. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.White M, Ducharme A, Ibrahim R, Whittom L, Lavoie J, Guertin MC, Racine N, He Y, Yao G, Rouleau JL, et al. Increased systemic inflammation and oxidative stress in patients with worsening congestive heart failure: improvement after short-term inotropic support. Clin Sci (Lond) 2006;110:483–489. doi: 10.1042/CS20050317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chung I, Lip GY. Platelets and heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2623–2631. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Feher G, Koltai K, Kesmarky G, Toth K. Hemorheological background of acetylsalicylic acid resistance. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2008;38:143–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cecchi E, Marcucci R, Paniccia R, Bandinelli B, Valente S, Giglioli C, Lazzeri C, Gensini GF, Abbate R, Mannini L. Effect of blood hematocrit and erythrocyte deformability on adenosine 5'-diphosphate platelet reactivity in patients with acute coronary syndromes on dual antiplatelet therapy. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:764–768. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Szapary L, Bagoly E, Kover F, Feher G, Pozsgai E, Koltai K, Hanto K, Komoly S, Doczi T, Toth K. The effect of carotid stenting on rheological parameters, free radical production and platelet aggregation. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2009;43:209–217. doi: 10.3233/CH-2009-1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Goodman T, Ferro A, Sharma P. Pharmacogenetics of aspirin resistance: a comprehensive systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;66:222–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2008.03183.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kunicki TJ, Williams SA, Nugent DJ, Harrison P, Segal HC, Syed A, Rothwell PM. Lack of association between aspirin responsiveness and seven candidate gene haplotypes in patients with symptomatic vascular disease. Thromb Haemost. 2009;101:123–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pamukcu B, Oflaz H, Onur I, Hancer V, Yavuz S, Nisanci Y. Impact of genetic polymorphisms on platelet function and aspirin resistance. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2010;21:53–56. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0b013e328332ef66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Labarthe B, Théroux P, Angioï M, Ghitescu M. Matching the evaluation of the clinical efficacy of clopidogrel to platelet function tests relevant to the biological properties of the drug. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;46:638–645. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ferguson AD, Dokainish H, Lakkis N. Aspirin and clopidogrel response variability: review of the published literature. Tex Heart Inst J. 2008;35:313–320. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lepäntalo A, Virtanen KS, Heikkilä J, Wartiovaara U, Lassila R. Limited early antiplatelet effect of 300 mg clopidogrel in patients with aspirin therapy undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:476–483. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2003.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Matetzky S, Shenkman B, Guetta V, Shechter M, Bienart R, Goldenberg I, Novikov I, Pres H, Savion N, Varon D, et al. Clopidogrel resistance is associated with increased risk of recurrent atherothrombotic events in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2004;109:3171–3175. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000130846.46168.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gurbel PA, Bliden KP, Hiatt BL, O'Connor CM. Clopidogrel for coronary stenting: response variability, drug resistance, and the effect of pretreatment platelet reactivity. Circulation. 2003;107:2908–2913. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000072771.11429.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Angiolillo DJ, Fernandez-Ortiz A, Bernardo E, Ramírez C, Barrera-Ramirez C, Sabaté M, Hernández R, Moreno R, Escaned J, Alfonso F, et al. Identification of low responders to a 300-mg clopidogrel loading dose in patients undergoing coronary stenting. Thromb Res. 2005;115:101–108. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lev EI, Patel RT, Maresh KJ, Guthikonda S, Granada J, DeLao T, Bray PF, Kleiman NS. Aspirin and clopidogrel drug response in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: the role of dual drug resistance. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lau WC, Waskell LA, Watkins PB, Neer CJ, Horowitz K, Hopp AS, Tait AR, Carville DG, Guyer KE, Bates ER. Atorvastatin reduces the ability of clopidogrel to inhibit platelet aggregation: a new drug-drug interaction. Circulation. 2003;107:32–37. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000047060.60595.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mitsios JV, Papathanasiou AI, Rodis FI, Elisaf M, Goudevenos JA, Tselepis AD. Atorvastatin does not affect the antiplatelet potency of clopidogrel when it is administered concomitantly for 5 weeks in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2004;109:1335–1338. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000124581.18191.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Müller I, Besta F, Schulz C, Li Z, Massberg S, Gawaz M. Effects of statins on platelet inhibition by a high loading dose of clopidogrel. Circulation. 2003;108:2195–2197. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000099507.32936.C0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Saw J, Steinhubl SR, Berger PB, Kereiakes DJ, Serebruany VL, Brennan D, Topol EJ. Lack of adverse clopidogrel-atorvastatin clinical interaction from secondary analysis of a randomized, placebo-controlled clopidogrel trial. Circulation. 2003;108:921–924. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000088780.57432.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lim MJ, Spencer FA, Gore JM, Dabbous OH, Agnelli G, Kline-Rogers EM, Dibenedetto D, Eagle KA, Mehta RH. Impact of combined pharmacologic treatment with clopidogrel and a statin on outcomes of patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes: perspectives from a large multinational registry. Eur Heart J. 2005;26:1063–1069. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wienbergen H, Gitt AK, Schiele R, Juenger C, Heer T, Meisenzahl C, Limbourg P, Bossaller C, Senges J. Comparison of clinical benefits of clopidogrel therapy in patients with acute coronary syndromes taking atorvastatin versus other statin therapies. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92:285–288. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(03)00626-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mukherjee D, Kline-Rogers E, Fang J, Munir K, Eagle KA. Lack of clopidogrel-CYP3A4 statin interaction in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Heart. 2005;91:23–26. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2004.035014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Brophy JM, Babapulle MN, Costa V, Rinfret S. A pharmacoepidemiology study of the interaction between atorvastatin and clopidogrel after percutaneous coronary intervention. Am Heart J. 2006;152:263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Saw J, Brennan DM, Steinhubl SR, Bhatt DL, Mak KH, Fox K, Topol EJ. Lack of evidence of a clopidogrel-statin interaction in the CHARISMA trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:291–295. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.01.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bhindi R, Ormerod O, Newton J, Banning AP, Testa L. Interaction between statins and clopidogrel: is there anything clinically relevant? QJM. 2008;101:915–925. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcn089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lau WC, Gurbel PA, Watkins PB, Neer CJ, Hopp AS, Carville DG, Guyer KE, Tait AR, Bates ER. Contribution of hepatic cytochrome P450 3A4 metabolic activity to the phenomenon of clopidogrel resistance. Circulation. 2004;109:166–171. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000112378.09325.F9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Srinivasan M, Smith D. Drug interaction with anti-mycobacterial treatment as a cause of clopidogrel resistance. Postgrad Med J. 2008;84:217–219. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2007.065193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gilard M, Arnaud B, Cornily JC, Le Gal G, Lacut K, Le Calvez G, Mansourati J, Mottier D, Abgrall JF, Boschat J. Influence of omeprazole on the antiplatelet action of clopidogrel associated with aspirin: the randomized, double-blind OCLA (Omeprazole CLopidogrel Aspirin) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:256–260. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.06.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Juurlink DN, Gomes T, Ko DT, Szmitko PE, Austin PC, Tu JV, Henry DA, Kopp A, Mamdani MM. A population-based study of the drug interaction between proton pump inhibitors and clopidogrel. CMAJ. 2009;180:713–718. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.082001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ray WA, Murray KT, Griffin MR, Chung CP, Smalley WE, Hall K, Daugherty JR, Kaltenbach LA, Stein CM. Outcomes with concurrent use of clopidogrel and proton-pump inhibitors: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:337–345. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-152-6-201003160-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kwok CS, Loke YK. Meta-analysis: the effects of proton pump inhibitors on cardiovascular events and mortality in patients receiving clopidogrel. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:810–823. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.O'Donoghue ML, Braunwald E, Antman EM, Murphy SA, Bates ER, Rozenman Y, Michelson AD, Hautvast RW, Ver Lee PN, Close SL, et al. Pharmacodynamic effect and clinical efficacy of clopidogrel and prasugrel with or without a proton-pump inhibitor: an analysis of two randomised trials. Lancet. 2009;374:989–997. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61525-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lau WC, Gurbel PA. The drug-drug interaction between proton pump inhibitors and clopidogrel. CMAJ. 2009;180:699–700. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Papp E, Havasi V, Bene J, Komlosi K, Talian G, Feher G, Horvath B, Szapary L, Toth K, Melegh B. Does glycoprotein IIIa gene (Pl(A)) polymorphism influence clopidogrel resistance? : a study in older patients. Drugs Aging. 2007;24:345–350. doi: 10.2165/00002512-200724040-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Marín F, González-Conejero R, Capranzano P, Bass TA, Roldán V, Angiolillo DJ. Pharmacogenetics in cardiovascular antithrombotic therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1041–1057. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.04.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mega JL, Close SL, Wiviott SD, Shen L, Hockett RD, Brandt JT, Walker JR, Antman EM, Macias W, Braunwald E, et al. Cytochrome p-450 polymorphisms and response to clopidogrel. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:354–362. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0809171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]