Epithelial cell proliferation in the developing zebrafish intestine is regulated by the Wnt pathway and microbial signaling via Myd88 (original) (raw)

Abstract

Rates of cell proliferation in the vertebrate intestinal epithelium are modulated by intrinsic signaling pathways and extrinsic cues. Here, we report that epithelial cell proliferation in the developing zebrafish intestine is stimulated both by the presence of the resident microbiota and by activation of Wnt signaling. We find that the response to microbial proliferation-promoting signals requires Myd88 but not TNF receptor, implicating host innate immune pathways but not inflammation in the establishment of homeostasis in the developing intestinal epithelium. We show that loss of axin1, a component of the β-catenin destruction complex, results in greater than WT levels of intestinal epithelial cell proliferation. Compared with conventionally reared axin1 mutants, germ-free axin1 mutants exhibit decreased intestinal epithelial cell proliferation, whereas monoassociation with the resident intestinal bacterium Aeromonas veronii results in elevated epithelial cell proliferation. Disruption of β-catenin signaling by deletion of the β-catenin coactivator tcf4 partially decreases the proliferation-promoting capacity of A. veronii. We show that numbers of intestinal epithelial cells with cytoplasmic β-catenin are reduced in the absence of the microbiota in both WT and axin1 mutants and elevated in animals’ monoassociated A. veronii. Collectively, these data demonstrate that resident intestinal bacteria enhance the stability of β-catenin in intestinal epithelial cells and promote cell proliferation in the developing vertebrate intestine.

Keywords: axin1, β-catenin, germ-free, intestinal epithelial cell, microbiota

The vertebrate intestinal epithelium is one of the most rapidly renewing tissues in the body. Perturbation of normal tissue homeostasis attributable to genetic lesions or environmental insults, such as infection with bacterial pathogens, can lead to hyperproliferative diseases of the intestinal tract (1). The regulation of intestinal epithelial cell proliferation has been studied extensively in the context of colorectal cancer (CRC), which has revealed canonical Wnt signaling as a key regulator of cell division and differentiation (2). Another contributing factor to rates of intestinal epithelial cell proliferation is the associated microbial community, as indicated by the paucity of proliferating cells in the intestines of germ-free (GF) rodents and zebrafish (3–5). However, the mechanisms underlying microbiota-induced cell proliferation are poorly understood.

Evidence for the role of Wnt signaling in intestinal homeostasis comes from mutations that perturb this genetic pathway. Canonical Wnt signaling is modulated by the levels of β-catenin protein; when abundant, β-catenin protein accumulates in the cytoplasm and translocates into the nucleus, where it interacts with coactivators, such as the intestine-specific transcription factor Tcf4, to turn on transcription of proproliferative target genes, including c-myc and sox9 (6, 7). In the absence of endogenous Wnt ligands, β-catenin levels are kept low by the activity of the cytoplasmic destruction complex, composed of Apc, Axin, and GSK-3, which target β-catenin for destruction by the proteosome. Constitutive activation of Wnt signaling, such as in the case of genetic loss of the β-catenin destruction complex, results in unchecked intestinal cell proliferation. This is seen in ApcMin/+ mutant mice in which clonal loss of heterozygosity of the WT Apc gene results in adenoma formation (8). These animals display a similar phenotype to human patients with familial adenomatous polyposis coli, who develop thousands of colonic polyps as a result of clonal loss of APC function. Conversely, when Wnt signaling is attenuated in transgenic adult mice overexpressing the Wnt receptor inhibitor Dkk-1 (9, 10) or in neonates lacking Tcf4 (7, 11), the small intestine is depleted of proliferating cells that normally replenish the intestinal epithelium.

Similar analyses in zebrafish have shown that Wnt signaling regulates cell proliferation in the adult zebrafish intestine; however its function in the larval intestine during the period of establishment of the gut microbiota has not been determined (12). Zebrafish heterozygous for the apcmrc mutation, which contains a premature stop codon in the apc gene, spontaneously develop intestinal neoplasia as adults (13), but apcmrc/mrc homozygotes die before 96 h postfertilization (hpf), before maturation of the larval gut, which begins to function in nutrient uptake at 5 d postfertilization (dpf) (14, 15). Conversely, zebrafish homozygous for the null mutation tcf4exl exhibit a loss of proliferative compartments within the intestinal epithelium, but this defect is only reported to be apparent in young adult zebrafish at 5 wk of age (16). An earlier role for tcf4 in the intestine is suggested by the finding that removal of tcf4 in the apcmrc/mrc mutant rescues expression of the intestinal marker ifabp at 72 hpf but not the early larval lethality (17). Collectively, these results demonstrate that appropriate levels of Wnt signaling are crucial for the maintenance of intestinal epithelial renewal in the adult intestine, but they do not explain how intestinal epithelial renewal rates are established during larval development. This is a crucial period in zebrafish development, analogous to the postnatal period in mammals, when the digestive tract is first colonized by microbes that influence the organ's maturation (18).

One mechanism by which animals perceive the presence of microbes is through the innate immune Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling pathway (19). TLRs were initially studied for their role in perceiving pathogens and activating host protective inflammatory responses. However, there is growing evidence for the critical role that TLR signaling plays in host perception of indigenous beneficial microbes (20), which typically do not elicit a strong inflammatory response. Myd88 functions as a key adaptor protein downstream of the majority of TLRs; when perturbed, it interferes with TLR signaling in mammals. The zebrafish genome has duplicated tlr genes but only a single copy of myd88 (21, 22). We and others have shown that Myd88 functions in zebrafish to modulate innate immune responses to microbes and microbial-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs), such as LPS (23–25). Notably, LPS sensing in zebrafish differs mechanistically from that in mammals and does not involve a Tlr4–MD2 complex (26).

Possible combinatorial effects of microbial and Wnt signaling on intestinal epithelial homeostasis are suggested by the observation that ApcMin/+ mice develop 50% fewer small intestinal adenomas when reared GF than when reared under conventional conditions (27). Similarly, deletion of Myd88 in ApcMin/+ mice results in fewer adenomas than in ApcMin/+ controls (28). We set out to investigate how the microbiota and Wnt signaling affect proliferation of the developing vertebrate intestinal epithelium. We used a gnotobiotic zebrafish model, which allowed us to manipulate readily both the presence and composition of the microbiota and the genetic makeup of the host. The overall development, tissue organization, and physiology of the teleost and mammalian intestines are highly similar (12, 14, 15). In this study, we made use of the axin1tm213 mutant that contains a missense mutation in the Gsk3-binding domain of Axin1 (29, 30), which disrupts the function of the β-catenin destruction complex. Homozygous axin1 mutants are viable through 8 dpf, allowing analysis of the effects of excessive Wnt signaling on the larval intestine. We report that cell proliferation in the larval zebrafish intestine is increased both by the presence of the microbiota and by up-regulation of Wnt signaling in an axin1 mutant. We demonstrate that myd88 is required for perception of the microbial signals that promote intestinal cell proliferation. We show that a dominant member of zebrafish gut microbiota, Aeromonas veronii, secretes proproliferative signals and that zebrafish with a mutation in the β-catenin coactivator Tcf4 have a decreased proliferative response to monoassociation with A. veronii. Finally, we show that GF larvae have reduced numbers of intestinal epithelial cells with cytoplasmic β-catenin and that A. veronii monoassociation is sufficient to promote the accumulation of cytoplasmic β-catenin in the intestinal epithelium, demonstrating that resident intestinal bacteria enhance Wnt pathway activity and elevate rates of epithelial renewal in the developing vertebrate intestine.

Results

Zebrafish Intestinal Epithelial Cell Proliferation Is Stimulated by the Microbiota.

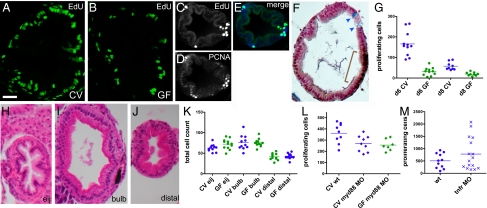

To investigate the influence of microbes on zebrafish intestinal cell proliferation, we exposed larvae to the nucleotide analogues BrdU and 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) and quantified S-phase nuclei in 30 serial sections in the intestinal bulb (Fig. 1 A and B). The absolute numbers of labeled cells varied with the different nucleotide analogues and even between trials, but the relative levels of cell proliferation between treatment groups were reproducible between trials. The spatial distribution of S-phase cells within the larval intestinal epithelium was sporadic, with some bias toward the bases of the emerging epithelial folds (Fig. 1_C_), as described (14, 15). We observed enrichment of proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) in the same cells that were labeled with EdU (Fig. 1 C_–_E), confirming that these were proliferating cells. We observed no PCNA staining in terminally differentiated goblet cells, which were visualized with Alcian blue staining (Fig. 1_F_), suggesting that zebrafish intestinal epithelial cells undergo proliferation before committing to a particular cell fate, similar to mammalian intestinal epithelial cells.

Fig. 1.

Microbes induce epithelial cell proliferation in the zebrafish larval intestine via Myd88 and not inflammation. Transverse sections of the intestinal bulb of 6-dpf larvae reared CV (A) or GF (B) labeled with EdU to reveal S-phase cells are shown. A transverse section of the distal intestine shows colocalization of EdU-labeled (C) and PCNA-labeled (D) cells (E, merge). (F) Distinct cell populations are stained with Alcian blue, marking differentiated goblet cells (arrowheads), and anti-PCNA, marking mitotic cells (brown bracket). (G) Total numbers of S-phase cells over 30 serial sections in the intestinal bulb of individual 6-dpf larvae are represented for the treatment groups and genotypes indicated. Here and in subsequent figures, the genotype and microbial exposure of each larva are indicated by the shape and color of the data point, respectively. Significantly fewer BrdU-labeled cells were found in 6- and 8-dpf larvae reared GF vs. CV (P < 0.001). H&E sections of 8-dpf GF intestines at three locations within the intestinal tract are shown: the esophageal intestinal junction (H, eij), defined as position 0; the bulb, 30 sections caudal to the junction (I); and the distal intestine, 60 sections caudal to the junction (J). (K) There was no significant difference between total intestinal epithelial cell counts at the three positions described above in 8-dpf CV vs. GF larvae. (L) Significantly fewer EdU-labeled cells were found in CV or GF myd88 MO vs. CV WT (wt) (P < 0.05). (M) There was no significant difference in the numbers of EdU-labeled cells between CV vs. GF myd88 MO or between wt vs. tnfr MO. (Scale bars: A and B, 15 μM; C_–_F and H_–_J, 25 μM.)

In conventionally reared (CV) larvae with normal microbiota, we observed a decrease in the number of dividing cells between 6 and 8 dpf (Fig. 1_G_), similar to other reports of proliferation patterns in the developing zebrafish intestine (14, 15, 31). In larvae reared GF, the intestinal epithelia exhibited significantly fewer dividing cells than in CV controls at both 6 and 8 dpf (Fig. 1_G_). This observation was consistent with previous analyses of cell proliferation in the 6-dpf GF zebrafish intestine (4, 32).

To determine whether these differences in cell proliferation resulted in an increase in intestinal cells in CV vs. GF animals, we scored the total number of epithelial cells in single H&E-stained tissue sections from three defined locations along the intestine (Fig. 1 H_–_J). We observed no significant differences in the total numbers of intestinal epithelial cells in CV and GF 8-dpf intestines at any of the three anatomical locations (Fig. 1_K_). The larval intestinal epithelium contains very few apoptotic cells (14), and there is no difference in the number of these cells between GV vs. CV larvae (4). Because fewer cells are dividing in GF vs. CV animals but the total numbers of cells in the two are similar, we infer that intestinal epithelial cells must undergo a slower rate of turnover in the absence of microbes.

Myd88 Is Required for Intestinal Epithelial Cell Proliferation in Response to Microbial Signals.

The TLRs are key sensors of MAMPs produced by both pathogenic and beneficial microbes. In mammals, Myd88 functions as a common downstream adaptor of the TLRs, and thus is a good target for disrupting TLR signaling. To test whether Myd88 functions in reception of the microbial cell proliferation-promoting signal in the zebrafish intestine, we examined cell proliferation levels in the intestinal epithelia of myd88 morpholino (MO)-injected animals. We observed significantly fewer proliferating cells in the myd88 MO-treated animals as compared with their WT siblings (Fig. 1_L_). Next, we compared intestinal epithelial cell proliferation in myd88 MO-injected larvae that were reared in the absence of the microbiota. If Myd88 function were required for the perception of the microbial signals that promote intestinal cell proliferation, in the absence of Myd88, the rate of cell proliferation should be the same irrespective of the presence or absence of the microbiota. Consistent with this prediction, we observed that the levels of cell proliferation in CV and GF myd88 MO-injected larvae were indistinguishable (Fig. 1_L_).

We have shown that on colonization of the zebrafish intestine, the microbiota elicit an influx of neutrophils into the intestinal epithelium by means of a Myd88-dependent mechanism (23). We wondered whether a mild inflammatory response to the microbiota, similar in mechanism but smaller in scale to the hypertrophic response of the epithelium to pathogen infection or injury (1), could produce the increased intestinal cell proliferation observed in the colonized larval intestine. Inhibition of TNF receptor with a pair of tnfr MOs efficiently blocked neutrophil influx in CV larvae (23). However, this treatment had no effect on the number of proliferating cells in the intestinal epithelium (Fig. 1_M_), suggesting that the microbiota-induced cell proliferation in the developing intestine is mechanistically distinct from pathological hypertrophy, which is known to require Myd88 function (33–35).

Wnt Signaling Promotes Cell Proliferation in the Zebrafish Larval Intestine.

Canonical Wnt signaling is a key pathway regulating the balance between proliferating and differentiated cells in the mammalian intestine (2). We sought to establish whether Wnt signaling functions in the larval zebrafish intestine to establish rates of epithelial proliferation during the period when the gut is first colonized by microbes. We therefore examined whether components of the Wnt signaling pathway are expressed in the larval intestine and whether they respond to known inducers of Wnt signaling.

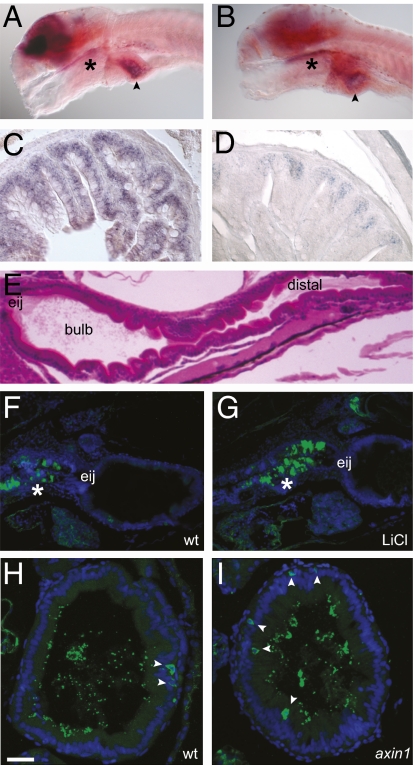

In situ hybridization against the β-catenin cofactor gene, tcf4, revealed strong expression within the brain and modest expression in the intestinal bulb in 6-dpf larvae (Fig. 2_A_). Low-level intestinal and brain expression of the Wnt target gene sox9b was also detected in larvae (Fig. 2_B_). We were unable to detect expression of the other Wnt target genes c-myc, axin2, cdx1a, or nt-1 by in situ hybridization in the larval intestine or the GFP product of the Wnt reporter topD line (36) by immunohistochemistry, but we were able to amplify these mRNAs from dissected larval intestines by RT-PCR (Fig. S1 A and B). In adult intestines, tcf4 was expressed throughout the villi (Fig. 2_C_) and sox9b was localized to the base of the villi (Fig. 2_D_) in the region where cell proliferation becomes restricted in adults.

Fig. 2.

Wnt signaling occurs in the larval zebrafish intestine. (A) In situ hybridization with a tcf4 probe reveals strong brain expression as well as signal in the pharynx (*) and intestinal bulb (arrowhead) in a 6-dpf larva. (B) In situ hybridization with a sox9b probe reveals expression in the brain, pharynx (*), and intestinal bulb (arrowhead) of a 6-dpf larva. Sections of adult proximal intestine displaying expression of tcf4 (C) and sox9b (D) are shown. (E) H&E sagittal section of a 5-dpf larva showing the location of the esophageal intestinal junction (eij), bulb, and distal intestine. Sagittal sections of 6-dpf untreated (F) and LiCl-treated (G) larvae show β-catenin expression (green) in the pharynx and esophagus (*). Nuclei are stained with DAPI (blue). Transverse sections through the intestinal bulb of 6-dpf WT (wt) (H) and axin1 mutant (I) larvae show scattered cells with cytoplasmic β-catenin staining (green, arrowheads). Luminal microbes cross-react with the anti-β-catenin antisera. Nuclei are stained with Torpo (blue). (Scale bars: A and B, 100 μM; C and D, 25 μM; E_–_G, 50 μM; H and I, 15 μM.)

We also examined expression of the Wnt pathway transducer β-catenin in the larval intestine. The zebrafish genome contains two β-catenin genes (37), which encode highly similar proteins that are recognized by polyclonal antisera raised against the human protein (38). Using these antisera, we detected strong cytoplasmic β-catenin expression in a subset of pharyngeal and esophageal cells (Fig. 2 F and G) and in a few scattered cells along the length of the intestine (Fig. 2 H and I). The antisera also cross-reacted with luminal intestinal microbes (Fig. 2 H and I), but these were easily distinguished from intestinal epithelial cells by their shape and location.

We next asked whether we could detect changes in levels of Wnt pathway components in response to modulators of Wnt signaling. First, we treated zebrafish larvae with LiCl, an inhibitor of β-catenin destruction complex member GSK-3 (39). Larvae exposed to 75 mM LiCl from 3 dpf exhibited stronger pharyngeal β-catenin staining at 6 dpf than untreated controls (Fig. 2 F and G). Second, we analyzed β-catenin distribution in the intestines of homozygous 6-dpf axin1tm213 mutants. We noted that relative to their WT siblings, the axin1 mutants had more cells with cytoplasmic β-catenin distributed along the length of their intestines (Fig. 2 H and I). We were also able to measure a modest 2-fold increase in transcript level of the Wnt target gene c-myc in intestines of axin1 8-dpf mutant larvae relative to WT siblings (Fig. S1_C_). Collectively, these data provide support for a functional Wnt pathway in the larval intestinal epithelium that is up-regulated in axin1tm213 mutants, but they suggest that the level of Wnt signaling in this tissue is low compared with that in other tissues, such as the brain.

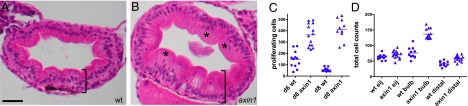

We next performed functional studies in the axin1 mutant to test whether Wnt signaling regulates cell proliferation in the larval intestine. We noted that in live 6-dpf axin1 animals, the intestines appeared larger and the tissue thicker and more convoluted (Fig. S1 D and E). H&E-stained sections of 8-dpf axin1 intestines revealed epithelial hypertrophy and regions of disordered epithelia (Fig. 3_B_), in contrast to the orderly alignment of cells in the intestinal epithelia of WT siblings (Fig. 3_A_). On quantification, we found that at both 6 and 8 dpf, axin1 mutant larvae had significantly more proliferating cells than WT siblings (Fig. 3_C_). We quantified an increase in the total number of intestinal epithelial cells in the axin1 mutant 8-dpf larvae, most notably in the intestinal bulb (Fig. 3_D_). The elevated intestinal epithelial cells in the axin1 mutant (1.8-fold more than in WT in the intestinal bulb) could not account for the increased number of S-phase cells in these animals (7-fold more than in WT in the intestinal bulb), confirming that rates of intestinal epithelial cell proliferation were elevated in the axin1 mutant.

Fig. 3.

Up-regulation of Wnt signaling causes intestinal hyperplasia. (A) H&E-stained section of an 8-dpf WT (wt) intestinal bulb shows an orderly array of cells in the intestinal epithelium. (B) An 8-dpf axin1 mutant intestine is thicker (bracket) and has more disorganized epithelial cells (*). (C) At both 6 and 8 dpf, axin1 mutants have significantly more BrdU-labeled cells within the intestinal epithelium than wt (P < 0.0001). (D) At 8 dpf, axin1 mutant intestines have significantly more epithelial cells in the bulb and distal intestine vs. wt (P < 0.0001). (Scale bar: A and B, 25 μM.)

Microbial Signals and Axin1 Loss Promote Cell Proliferation Combinatorially.

We had so far shown that both the presence of microbes and activation of Wnt signaling through impairment of the β-catenin destruction complex increased cell proliferation in the intestinal epithelium. We next asked whether the microbiota induced cell proliferation by promoting Wnt signaling upstream of the β-catenin destruction complex. If this were the case, we would expect _axin1_-deficient animals, which experience constitutive Wnt signaling, to be insensitive to microbial signals, and thus to exhibit similar levels of intestinal epithelial cell proliferation in the presence or absence of microbes. However, when we quantified cell proliferation in 6-dpf GF axin1 larvae, we observed significantly fewer dividing nuclei than in CV axin1 siblings (Fig. 4_A_). These observations suggest that the microbial signals promoting cell proliferation do so through a pathway that functions in parallel to or downstream of Axin1.

Fig. 4.

Combinatorial effects of microbial and Wnt signaling on intestinal epithelial cell proliferation. (A_–_F) S-phase intestinal epithelial cells were quantified in 30 serial sections in the intestinal bulb of individual larvae as in Fig. 1. To label S-phase nuclei, the experiments in A and D used BrdU and the experiments in B, C, E, and F used EdU. All experiments were performed with 6-dpf larvae except the experiment in D, which was performed with 8-dpf larvae. (A) CV axin1 had significantly more proliferating intestinal cells than CV WT (wt), GF wt, and GF axin1 (P < 0.0001). GF axin1 had significantly more proliferating cells than GF wt (P < 0.01). (B) axin1 had significantly more proliferating cells than wt, myd88 MO, and axin1 myd88 MO (P < 0.001). axin1 myd88 MO had significantly more proliferating cells than myd88 MO (P < 0.001). (C) Exposure of GF larvae from 3 to 6 dpf to 30 μg/mL LPS caused no change in cell proliferation relative to untreated GF larvae. (D) Monoassociation of GF larvae with A. veronii (AMA) or treatment with 500 ng/mL A. veronii CFS induced a significant increase in intestinal cell proliferation relative to GF (P < 0.0001). (E) axin1 mutants monoassociated with A. veronii had significantly more proliferating cells than CV axin1 (P < 0.0001). (F) tcf4 mutants had significantly fewer dividing intestinal cells than wt siblings when reared GF (P < 0.01) and when monoassociated with A. veronii (P < 0.0001). Intestinal epithelial cells with cytoplasmic β-catenin were quantified in 30 serial sections in the intestinal bulb of 6-dpf larvae. (G and H) CV wt larvae had significantly more β-catenin-positive cells than GF wt larvae (P < 0.05). (G) CV axin1 had significantly more β-catenin-positive cells than GF axin1 (P < 0.05). (H) A. veronii monoassociated larvae had significantly more β-catenin-positive cells than CV animals (P < 0.0001).

If Myd88 functions to transduce the signals from the microbiota that promote intestinal epithelial cell proliferation, we would predict that an axin1 mutant lacking myd88 would resemble an axin1 mutant reared under GF conditions. Similar to our observations in GF axin1 mutants, we observed a significant decrease of cell proliferation in the intestinal epithelia of axin1 mutants injected with the myd88 MO, with levels that resembled those of CV WT controls (Fig. 4_B_). These data are consistent with the model that Myd88 transduces the microbial signals that promote intestinal epithelial cell proliferation in parallel to or downstream of Axin1.

Secreted Bacterial Signals Modulate Levels of Intestinal Epithelial Cell Proliferation.

We next wanted to explore the nature of the microbial signals that promote intestinal cell proliferation. Because we had shown that Myd88 is required for this response, we wondered whether any TLR ligand could induce this response. We have shown previously that LPS induces certain Myd88-mediated responses when administered to zebrafish larvae in their water, including toxicity (at 50 μg/mL or higher) and induction of intestinal alkaline phosphatase activity (at 3 and 30 μg/mL) (23). We tested whether purified LPS that was competent to elicit these responses (Fig. S2 A and B) was sufficient to stimulate intestinal proliferation when added to GF larvae at the sublethal dose of 30 μg/mL. We found that exposure to 30 μg/mL LPS caused no increase in the number of proliferating cells in the intestinal epithelia of GF larvae (Fig. 4_C_). Having ruled out a generic MAMP as the intestinal epithelial cell proliferation-promoting factor, we sought to establish whether specific members of the zebrafish gut microbiota possessed this activity.

The complexity of the zebrafish microbiota is similar to that of mammals, but the community is dominated by Gram-negative Gamma-Proteobacteria (4, 32). Previously, we had found that monoassociation with a strain of A. veronii biovar sobria, a member of the dominant genera of the zebrafish microbiota, was sufficient to reverse multiple GF traits (40). We therefore tested whether A. veronii monoassociation could induce cell proliferation in GF animals, using two different experimental time courses: inoculation of GF larvae at 4 dpf and assaying at 6 dpf or inoculation at 6 dpf and assaying at 8 dpf. At both end points, monoassociation with A. veronii was sufficient to stimulate intestinal epithelial cell proliferation significantly (Fig. 4 D and F).

We proceeded to characterize the _A. veronii_-associated cell proliferation promoting activity by testing whether it was secreted or required the presence of the bacteria. We generated A. veronii cell-free supernatant (CFS) by centrifugation and filtration and further purified it using a concentrator with a molecular mass cutoff of 10 kDa, which reduced the toxicity of the solution when administered to fish [likely by removing toxic LPS (23)]. A. veronii CFS, when added back to GF larvae at 6 dpf, was sufficient to increase intestinal cell proliferation at 8 dpf (Fig. 4_D_). As with the A. veronii monoassociations, the levels of intestinal epithelium cell proliferation in CFS-treated larvae were sometimes slightly higher than those found in CV larvae (Fig. 4_D_).

We used the simplified A. veronii monoassociation model to investigate the relation between bacterial and Wnt signaling further. We reasoned that if A. veronii monoassociation stimulated cell proliferation independent of inhibition of Axin1, the effects of bacterial inoculation and axin1 deficiency should be combinatorial. Indeed, when we monoassociated axin1 mutants with A. veronii, we observed levels of intestinal epithelial cell proliferation that significantly exceeded those of the CV axin1 mutants (Fig. 4_E_), consistent with our other evidence suggesting that microbiota signals promote cell proliferation in parallel to or downstream of Axin1.

To address whether bacterial signals promote proliferation through components of the Wnt pathway downstream of Axin1, we made use of the zebrafish tcf4exl null mutant (16). Previous characterization of this mutant had revealed no impairment in intestinal epithelial cell proliferation before 5 wk postfertilization. When we carefully analyzed cell proliferation in these mutants at 6 dpf, we observed a slight but statistically significant decrease relative to WT siblings (Fig. 4_F_), demonstrating that canonical Wnt signaling is required for normal levels of cell proliferation in the larval intestine. We reasoned that if A. veronii monoassociation promotes intestinal cell proliferation upstream of Tcf4, the proliferative response should be blocked in _A. veronii_-monoassociated tcf4 mutants. We observed that the proliferative response to A. veronii was partly decreased in the tcf4 mutants (Fig. 4_F_; 1.8-fold increase over GF) as compared with the WT response (2.4-fold increase over GF), suggesting that Tcf4 function is partially required for transduction of the A. veronii proliferation-promoting signal.

Resident Bacteria Promote β-Catenin Stability in Intestinal Epithelial Cells.

To look for direct evidence of Wnt signaling regulation by the microbiota, we quantified intestinal epithelial cells with cytoplasmic β-catenin in the same region of the intestinal bulb in which we had quantified S-phase nuclei. Consistent with the role of Axin1 in the β-catenin destruction complex, we observed significantly more cells with cytoplasmic β-catenin in axin1 mutant vs. WT intestinal epithelia (Fig. 4_G_). When WT animals were reared GF, their intestinal epithelia contained significantly fewer cells with cytoplasmic β-catenin than CV siblings (Fig. 4 G and H), indicating that the presence of the microbiota stabilized β-catenin in the intestinal epithelium. This observation also held true in axin1 mutants, in which the number of cells with cytoplasmic β-catenin was significantly reduced in the absence vs. presence of the microbiota (Fig. 4_G_). Finally, we quantified β-catenin-positive cells in the intestinal epithelia of larvae colonized solely with A. veronii. We found that monoassociation with A. veronii was sufficient to increase numbers of intestinal epithelial cells with cytoplasmic β-catenin to levels significantly higher than those observed in GF or CV animals (Fig. 4_H_), demonstrating that a resident intestinal bacterium is capable of stabilizing β-catenin in intestinal epithelial cells.

Discussion

When the vertebrate intestine is first colonized by microbes at birth or hatching, this tissue is still undergoing maturation and establishment of adult patterns of tissue renewal. Studies in GF zebrafish clearly demonstrated a role for the microbiota in stimulating rates of intestinal cell proliferation during this period of development (4). We can speculate on why microbes elicit an increase in intestinal epithelial renewal. From the host's perspective, increased cell turnover may be beneficial as a mechanism to purge epithelial cells exposed to increased concentrations of harmful chemicals, such as reactive oxygen species, associated with microbial colonization. From the microbes’ perspective, stimulating cell turnover would increase the numbers of host cells shed into the lumen and the availability of host-derived glycans that can serve as nutrient sources for the microbial community (41).

We report here that Myd88, an adaptor for the TLR family of innate immune receptors, is required for the normal proliferative response to the microbiota in the developing zebrafish intestine. In mice, adult Myd88 mutants have normal or slightly elevated numbers of proliferating intestinal epithelial cells in the absence of injury (33, 34), but the effect of Myd88 signaling on rates of intestinal epithelial proliferation has not yet been characterized in neonates (42). The mechanisms underlying intestinal epithelial cell proliferation during normal development are likely to be different from those operating in the proliferative response to injury in the adult intestine. Intestinal epithelial cell proliferation in adult mice in response to the toxin dextran sodium sulfate (DSS) or Citrobacter rodentia infection occurs with a robust induction of proinflammatory cytokines, which is blunted in the absence of Myd88 (35, 43). Furthermore, blocking TNF signaling attenuates tumor formation in a murine model of DSS-induced colitis-associated CRC (44).

In contrast to the described role of Myd88 in promoting inflammation-associated hypertrophy in the intestines of adult mice, we found no correlation between signals that induce inflammation and cell proliferation in the developing zebrafish intestine. LPS, which is sufficient to protect against DSS toxicity associated with a defective proliferative response in the sterilized mouse intestine (35), and which induces inflammatory responses in the zebrafish intestine (23), did not induce epithelial cell proliferation. Furthermore, we found that inhibition of inflammatory responses with TNF receptor MOs had no effect on cell proliferation in the larval intestine.

We provide evidence that Wnt signaling is both necessary and sufficient to promote cell proliferation in the larval zebrafish intestine, using the tfc4 and axin1 mutants, respectively. Given the importance of Wnt signaling in regulating cell renewal in this tissue, we asked whether microbial signals could increase cell proliferation by up-regulating Wnt signaling. We addressed the interactions between microbial and Wnt signaling in intestinal epithelial renewal by manipulating both host genetics and microbial associations. These tests were imperfect because of the complexity of the microbial signals and the limitations of Wnt pathway mutants (the axin1tm213 allele may have some residual activity because the phenotype is temperature-sensitive, and the tcf4exl mutant larvae may have some maternal gene product that could explain the mild proliferation defect at this stage). Nonetheless, our data support the model that the microbiota promote intestinal epithelial cell proliferation, in part, by up-regulating Wnt signaling downstream of Axin1 and upstream of Tcf4. The proliferative effects of the axin1 mutation were combinatorial with the presence or absence and the composition of the microbiota, suggesting that the proliferative signals from the microbiota act in parallel to or downstream of Axin1. The proliferative response to A. veronii monoassociation was considerably reduced in the tcf4 mutant, indicating that the signals from microbiota may act partly through Tcf4 to promote intestinal epithelial proliferation.

To gain mechanistic insight into the interaction between the microbiota and the Wnt signaling pathway, we quantified intestinal epithelial cells with cytoplasmic β-catenin. Cytoplasmic accumulation of β-catenin is indicative of active Wnt signaling. Loss of the β-catenin destruction complex component, Axin1, resulted in elevated numbers of intestinal epithelial cells with cytoplasmic β-catenin. Most intestinal epithelial cells in the axin1 mutant still displayed low levels of β-catenin, indicating that other factors prevent the accumulation of β-catenin in these cells. Consistent with our observation that the presence of the microbiota and the loss of axin1 acted combinatorially to promote intestinal epithelial cell proliferation, we observed that these factors both contribute to β-catenin levels in the intestine, with significantly fewer β-catenin-positive cells in GF vs. CV axin1 mutants. Furthermore, we demonstrated that colonization of the GF intestine with A. veronii was sufficient to stabilize β-catenin to higher than CV levels. Our observation that loss of the β-catenin coactivator Tcf4 partially blocks the proproliferative activity of A. veronii is consistent with the model that A. veronii induces intestinal epithelial cell proliferation by increasing the stability of β-catenin in these cells.

One possible mechanism for microbial signaling through the Wnt pathway could involve a Myd88-dependent up-regulation of prostaglandin E2, a molecule that has been shown to stimulate Wnt signaling and promote stem cell regeneration in a number of larval zebrafish tissues through phosphorylation-based regulation of β-catenin stability (45). Another possible mechanism could involve microbial induction of reactive oxygen species, which have been shown to promote Wnt signaling through inhibition of β-catenin ubiquitination (46). Additionally, gastrointestinal bacteria may produce specific effector molecules that activate Wnt signaling, as has been shown for the CagA protein of Helicobacter pylori (47). All these mechanisms stimulate Wnt signaling downstream of Axin1 and upstream of Tcf4, similar to the zebrafish microbiota-associated signals we describe here.

We do not know the chemical nature of the microbial signals that promote cell proliferation in the zebrafish larval intestine, but our experiments shed some light on their properties. We showed that LPS exposure is not sufficient to stimulate intestinal cell proliferation and that _A. veronii_-secreted factors greater than 10 kDa stimulate proliferation in the intestine. We hypothesize that members of the microbiota produce multiple proproliferative factors at various concentrations and with various potencies. Indeed, Rawls et al. (32) observed differences in the extent to which individual bacteria could induce intestinal cell proliferation in monoassociations. Different assemblages of gut microbes would therefore have different proliferative capacities. Notably, colonization of axin1 mutants with a monoculture of A. veronii elicited significantly more cell proliferation than colonization with complex microbiota. In humans, the majority of spontaneous and hereditary mutations associated with CRC impair the β-catenin destruction complex (48). Our data suggest that although an individual's genetic Wnt status clearly plays an important role in determining CRC risk, the individual's microbiota and innate immune system function will likely contribute to the risk for intestinal epithelial hyperproliferation. Proinflammatory microbes are likely to contribute to the development of colitis-associated CRC (49). Our data suggest that members of the microbiota also influence rates of intestinal epithelial cell proliferation independent of inflammation via direct modulation of β-catenin signaling.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

All experiments with zebrafish were performed using protocols approved by the University of Oregon Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and following standard protocols (50). WT (Ab/Tu) zebrafish were reared at 28 °C. The axin1tm213 mutant line was reared at 30 °C; at that temperature, the eye development defect was fully penetrant among the homozygotes (29). The tcf4exl mutant line (16) was kindly provided by Tatyana Piotrowski (University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah). Progeny from tcf4exl/+ parents were euthanized at 6 dpf, and tail tissue posterior to the vent was removed for genotyping. Genotyping was carried out by PCR as described (16). GF embryos were derived and maintained as previously described (40). All larvae were starved through the duration of the experiments.

Brdu and EdU Labeling and Quantification of Proliferating Cells.

Larvae were immersed in 200 μg/mL BrdU (B-5002; Sigma) and 20 μg/mL 5′-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine (F-0503; Sigma) or 100 μg/mL EdU (A10044; Invitrogen) for 16 h before termination of the experiment. Larvae were fixed in BT fixative (4% paraformaldehyde, 0.15 mM CaCl2, 4% sucrose in 0.1 M PO4 buffer) (50) for 4 h at room temperature with gentle shaking, immediately processed for paraffin embedding, and cut into 7-μm sections. To detect BrdU, sections were deparaffinized and tissue-denatured in 2 M warm HCl for 20 min, neutralized in 0.1 mM sodium borate for 10 min, and rinsed in PBS/0.5% Triton X-100 (PBSt). Tissue was blocked for 1 h at room temperature in 10% (vol/vol) normal goat serum in PBSt and soaked in anti-BrdU (1:150, 11170376001 mouse monoclonal; Roche) overnight at 4 °C. Slides were then rinsed in PBSt, incubated in secondary goat-anti-mouse 488 (1:500; Molecular Probes) for 2 h, rinsed again, and mounted in Vectashield (Vector). For EdU detection, slides were processed according to the Click-iT EdU Cell Proliferation Assay Kit (C35002; Molecular Probes).

BrdU- or EdU-labeled nuclei within the intestinal epithelium were counted over 30 serial 7-μm sections beginning at the esophageal-intestinal junction and proceeding caudally into the bulb. Analysis of this extended region was necessary because of the stochastic patterns of cell proliferation. The absolute numbers of labeled cells varied between trials and the type and batches of nucleotide analogues. For example, fewer labeled cells were observed with BrdU vs. EdU treatment, likely because of less efficient incorporation of the nucleotide into cells and less efficient detection of the antigen. Despite these differences in the absolute numbers of labeled cells, the proportional trends of proliferating cells between treatments and genotypes were consistent and reproducible between trials.

LPS Treatment.

Filter-sterilized LPS (Escherichia coli serotype 0111:B4, product no. 62325; Sigma) solution was injected into flasks of 3-dpf GF larvae to a final concentration of 30 μg/mL, and cell proliferation was quantified at 6 dpf by labeling S-phase nuclei with EdU as above.

H&E Staining and Cell Counts.

Larvae were fixed overnight in Dietrich's fixative, processed for paraffin sectioning, cut into 7-μM sections, and stained according to standard protocols (51). The total number of epithelial cells was quantified in a single section at the location of the esophageal-intestinal junction, 30 sections caudal in the bulb, and 60 sections caudal in the distal intestine.

Immunohistochemistry and in Situ Hybridization.

Larvae were fixed overnight in BT, processed for paraffin embedding, and cut into 7-μM sections. Following deparaffinization, antigen retrieval was performed by boiling in 0.1 M sodium citrate for 1 or 20 min (for detection of PCNA and β-catenin, respectively) and cooling to room temperature for 30 min. Slides were blocked in 10% (vol/vol) normal goat serum in PBSt for 1 h and then exposed to anti-β-catenin (1:1,000, C2206 rabbit polyclonal; Sigma) or anti-PCNA (1:5,000 for immunofluorescence or 1:20,000 for colorimetric detection, P8825 mouse monoclonal; Sigma) overnight at 4 °C. Antibodies were detected with appropriate fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes) as above. To visualize proliferating and goblet cells, anti-PCNA was detected with HRP-conjugated secondary using a Vectastain ABC kit (Vector Laboratories) and subsequently stained with Alcian blue solution (pH 2.5) for 90 min, counterstained with nuclear fast red (Vector Laboratories) for 10 min, dehydrated in 95% (vol/vol) alcohol, cleared in xylene, and mounted in Permount (Fisher Scientific). Intestinal epithelial cells with cytoplasmic β-catenin were quantified in 30 serial sections caudal from the esophageal-intestinal junction.

In situ hybridization on larvae was performed as described (50), with the addition of a 20-min soak in proteinase K (2 μg/mL) followed by a 20-min postfixation. In situ hybridization on adult cryosectioned tissue was performed as described (52). RNA probes included sox9b (53) and tcf4 (54).

Microscopy.

Samples were imaged on a Nikon Eclipse TE 2000-V inverted microscope equipped with a Photometrics Coolsnap camera. Confocal images were captured using a Nikon D-Eclipse C1 microscope. Images were manipulated in Adobe Photoshop.

Monoassociations and CFS Preparation.

Cultures of A. veronii biovar sobria strain HM21R (55) were grown at 30 °C for 17 h on a rotary shaker at 170 rpm. Flasks of GF larvae were inoculated with 105 to 106 cfu/mL culture on 4 or 6 dpf, and the experiment was terminated on 6 or 8 dpf, respectively. Monoassociation experiments were deemed successful when dissected homogenized intestines yielded an average of 103 cfu on tryptic soy agar plates.

A. veronii cultures prepared as above were spun at 5,600 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was passed through a 0.22-μM filter (Corning) on ice. CFS was concentrated through an Amicon Ultra-15 spin concentrator to remove small products, which were toxic to the fish. Protein concentration was determined by Bradford assay. All CFS exposures were performed using 500 ng/mL total protein, corresponding to ≈108 A. veronii cells/mL.

MO Injections.

Splice-blocking MOs targeting myd88 and tnfr were used as described (23). MO-injected larvae exhibited good survival, developed a swim bladder, and were grossly similar to their control siblings. Efficacy of the MO was assessed by RT-PCR and, in the case of the tnfr MO, by the ability to inhibit influx of myeloid peroxidase-positive neutrophils into the intestines (23).

Statistical Analysis.

Student's unpaired t tests were performed with GraphPad Prism software.

Supplementary Material

Supporting Information

Acknowledgments

We thank Rose Gaudreau and the staff of the University of Oregon Zebrafish Facility for excellent fish husbandry; Poh Kheng Loi for histology services; Zac Stevens, Ye Yang, and Bailey McCracken for their contributions to the project; Ruth Bremiller and Adriana Rodriguez for assistance with in situ hybridizations; Hans Clevers (Hubrecht Institute, Utrecht, The Netherlands) and Tatyana Piotrowski (University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah) for providing the tcf4 zebrafish line; Richard Dorsky and Katrina Baden for helpful discussions; and Judith Eisen and Tory Herman for critical reading of the manuscript. This research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 DK075549 and a Burroughs Wellcome Fund Investigator in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease Award (to K.G.) and a National Institutes of Health National Research Service Award fellowship (to S.E.C.). National Institutes of Health Grant HD22486 provided support for the Oregon Zebrafish Facility.

Footnotes

This paper results from the Arthur M. Sackler Colloquium of the National Academy of Sciences, “Microbes and Health,” held November 2–3, 2009, at the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Center of the National Academies of Sciences and Engineering in Irvine, CA. The complete program and audio files of most presentations are available on the NAS Web site at http://www.nasonline.org/SACKLER_Microbes_and_Health.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

References

- 1.Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 2010;140:883–899. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Flier LG, Clevers H. Stem cells, self-renewal, and differentiation in the intestinal epithelium. Annu Rev Physiol. 2009;71:241–260. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.010908.163145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abrams GD, Bauer H, Sprinz H. Influence of the normal flora on mucosal morphology and cellular renewal in the ileum. A comparison of germ-free and conventional mice. Lab Invest. 1963;12:355–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rawls JF, Samuel BS, Gordon JI. Gnotobiotic zebrafish reveal evolutionarily conserved responses to the gut microbiota. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:4596–4601. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400706101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uribe A, Alam M, Johansson O, Midtvedt T, Theodorsson E. Microflora modulates endocrine cells in the gastrointestinal mucosa of the rat. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:1259–1269. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90526-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blache P, et al. SOX9 is an intestine crypt transcription factor, is regulated by the Wnt pathway, and represses the CDX2 and MUC2 genes. J Cell Biol. 2004;166:37–47. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200311021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van de Wetering M, et al. The beta-catenin/TCF-4 complex imposes a crypt progenitor phenotype on colorectal cancer cells. Cell. 2002;111:241–250. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Su LK, et al. Multiple intestinal neoplasia caused by a mutation in the murine homolog of the APC gene. Science. 1992;256:668–670. doi: 10.1126/science.1350108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuhnert F, et al. Essential requirement for Wnt signaling in proliferation of adult small intestine and colon revealed by adenoviral expression of Dickkopf-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:266–271. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2536800100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pinto D, Gregorieff A, Begthel H, Clevers H. Canonical Wnt signals are essential for homeostasis of the intestinal epithelium. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1709–1713. doi: 10.1101/gad.267103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Korinek V, et al. Depletion of epithelial stem-cell compartments in the small intestine of mice lacking Tcf-4. Nat Genet. 1998;19:379–383. doi: 10.1038/1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Faro A, Boj SF, Clevers H. Fishing for intestinal cancer models: Unraveling gastrointestinal homeostasis and tumorigenesis in zebrafish. Zebrafish. 2009;6:361–376. doi: 10.1089/zeb.2009.0617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haramis AP, et al. Adenomatous polyposis coli-deficient zebrafish are susceptible to digestive tract neoplasia. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:444–449. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ng AN, et al. Formation of the digestive system in zebrafish: III. Intestinal epithelium morphogenesis. Dev Biol. 2005;286:114–135. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wallace KN, Akhter S, Smith EM, Lorent K, Pack M. Intestinal growth and differentiation in zebrafish. Mech Dev. 2005;122:157–173. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Muncan V, et al. T-cell factor 4 (Tcf7l2) maintains proliferative compartments in zebrafish intestine. EMBO Rep. 2007;8:966–973. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7401071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Faro A, et al. T-cell factor 4 (tcf7l2) is the main effector of Wnt signaling during zebrafish intestine organogenesis. Zebrafish. 2009;6:59–68. doi: 10.1089/zeb.2009.0580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheesman SE, Guillemin K. We know you are in there: Conversing with the indigenous gut microbiota. Res Microbiol. 2007;158:2–9. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2006.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abreu MT. Toll-like receptor signalling in the intestinal epithelium: How bacterial recognition shapes intestinal function. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:131–144. doi: 10.1038/nri2707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rakoff-Nahoum S, Medzhitov R. Innate immune recognition of the indigenous microbial flora. Mucosal Immunol. 2008;1(Suppl 1):S10–S14. doi: 10.1038/mi.2008.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jault C, Pichon L, Chluba J. Toll-like receptor gene family and TIR-domain adapters in Danio rerio. Mol Immunol. 2004;40:759–771. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meijer AH, et al. Expression analysis of the Toll-like receptor and TIR domain adaptor families of zebrafish. Mol Immunol. 2004;40:773–783. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bates JM, Akerlund J, Mittge E, Guillemin K. Intestinal alkaline phosphatase detoxifies lipopolysaccharide and prevents inflammation in zebrafish in response to the gut microbiota. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;2:371–382. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van der Sar AM, et al. MyD88 innate immune function in a zebrafish embryo infection model. Infect Immun. 2006;74:2436–2441. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.4.2436-2441.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hall C, et al. Transgenic zebrafish reporter lines reveal conserved Toll-like receptor signaling potential in embryonic myeloid leukocytes and adult immune cell lineages. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;85:751–765. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0708405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sullivan C, et al. The gene history of zebrafish tlr4a and tlr4b is predictive of their divergent functions. J Immunol. 2009;183:5896–5908. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dove WF, et al. Intestinal neoplasia in the ApcMin mouse: independence from the microbial and natural killer (beige locus) status. Cancer Res. 1997;57:812–814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rakoff-Nahoum S, Medzhitov R. Regulation of spontaneous intestinal tumorigenesis through the adaptor protein MyD88. Science. 2007;317:124–127. doi: 10.1126/science.1140488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heisenberg CP, et al. A mutation in the Gsk3-binding domain of zebrafish Masterblind/Axin1 leads to a fate transformation of telencephalon and eyes to diencephalon. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1427–1434. doi: 10.1101/gad.194301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van de Water S, et al. Ectopic Wnt signal determines the eyeless phenotype of zebrafish masterblind mutant. Development. 2001;128:3877–3888. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.20.3877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crosnier C, et al. Delta-Notch signalling controls commitment to a secretory fate in the zebrafish intestine. Development. 2005;132:1093–1104. doi: 10.1242/dev.01644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rawls JF, Mahowald MA, Ley RE, Gordon JI. Reciprocal gut microbiota transplants from zebrafish and mice to germ-free recipients reveal host habitat selection. Cell. 2006;127:423–433. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.08.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gibson DL, et al. MyD88 signalling plays a critical role in host defence by controlling pathogen burden and promoting epithelial cell homeostasis during Citrobacter rodentium-induced colitis. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:618–631. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pull SL, Doherty JM, Mills JC, Gordon JI, Stappenbeck TS. Activated macrophages are an adaptive element of the colonic epithelial progenitor niche necessary for regenerative responses to injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:99–104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405979102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rakoff-Nahoum S, Paglino J, Eslami-Varzaneh F, Edberg S, Medzhitov R. Recognition of commensal microflora by toll-like receptors is required for intestinal homeostasis. Cell. 2004;118:229–241. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dorsky RI, Sheldahl LC, Moon RT. A transgenic Lef1/beta-catenin-dependent reporter is expressed in spatially restricted domains throughout zebrafish development. Dev Biol. 2002;241:229–237. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bellipanni G, et al. Essential and opposing roles of zebrafish beta-catenins in the formation of dorsal axial structures and neurectoderm. Development. 2006;133:1299–1309. doi: 10.1242/dev.02295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trinh LA, Stainier DY. Fibronectin regulates epithelial organization during myocardial migration in zebrafish. Dev Cell. 2004;6:371–382. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00063-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klein PS, Melton DA. A molecular mechanism for the effect of lithium on development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8455–8459. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bates JM, et al. Distinct signals from the microbiota promote different aspects of zebrafish gut differentiation. Dev Biol. 2006;297:374–386. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sonnenburg JL, Angenent LT, Gordon JI. Getting a grip on things: How do communities of bacterial symbionts become established in our intestine? Nat Immunol. 2004;5:569–573. doi: 10.1038/ni1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Iiyama R, et al. Normal development of the gut-associated lymphoid tissue except Peyer's patch in MyD88-deficient mice. Scand J Immunol. 2003;58:620–627. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2003.01346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lebeis SL, Bommarius B, Parkos CA, Sherman MA, Kalman D. TLR signaling mediated by MyD88 is required for a protective innate immune response by neutrophils to Citrobacter rodentium. J Immunol. 2007;179:566–577. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.1.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Popivanova BK, et al. Blocking TNF-alpha in mice reduces colorectal carcinogenesis associated with chronic colitis. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:560–570. doi: 10.1172/JCI32453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goessling W, et al. Genetic interaction of PGE2 and Wnt signaling regulates developmental specification of stem cells and regeneration. Cell. 2009;136:1136–1147. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kumar A, et al. Commensal bacteria modulate cullin-dependent signaling via generation of reactive oxygen species. EMBO J. 2007;26:4457–4466. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Franco AT, et al. Activation of beta-catenin by carcinogenic Helicobacter pylori. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:10646–10651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504927102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fodde R, Brabletz T. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in cancer stemness and malignant behavior. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2007;19:150–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hope ME, Hold GL, Kain R, El-Omar EM. Sporadic colorectal cancer—Role of the commensal microbiota. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2005;244:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Westerfield M. The Zebrafish Book. 4th Ed. Eugene, OR: Univ of Oregon Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mohideen MA, et al. Histology-based screen for zebrafish mutants with abnormal cell differentiation. Dev Dyn. 2003;228:414–423. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rodríguez-Marí A, et al. Characterization and expression pattern of zebrafish Anti-Müllerian hormone (Amh) relative to sox9a, sox9b, and cyp19a1a, during gonad development. Gene Expr Patterns. 2005;5:655–667. doi: 10.1016/j.modgep.2005.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yan YL, et al. A pair of Sox: Distinct and overlapping functions of zebrafish sox9 co-orthologs in craniofacial and pectoral fin development. Development. 2005;132:1069–1083. doi: 10.1242/dev.01674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Young RM, Reyes AE, Allende ML. Expression and splice variant analysis of the zebrafish tcf4 transcription factor. Mech Dev. 2002;117:269–273. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00180-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Graf J. Symbiosis of Aeromonas veronii biovar sobria and Hirudo medicinalis, the medicinal leech: A novel model for digestive tract associations. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1–7. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.1.1-7.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information