Robertson's Mutator transposons in A. thaliana are regulated by the chromatin-remodeling gene Decrease in DNA Methylation (DDM1) (original) (raw)

Abstract

Robertson's Mutator transposable elements in maize undergo cycles of activity and then inactivity that correlate with changes in cytosine methylation. _Mutator_-like elements are present in the Arabidopsis genome but are heavily methylated and inactive. These elements become demethylated and active in the chromatin-remodeling mutant ddm1 (D ecrease in D NA M ethylation), which leads to loss of heterochromatic DNA methylation. Thus, DNA transposons in plants appear to be regulated by chromatin remodeling. In inbred ddm1 strains, transposed elements may account, in part, for mutant phenotypes unlinked to ddm1. Gene silencing and paramutation are also regulated by DDM1, providing support for the proposition that epigenetic silencing is related to transposon regulation.

Keywords: Transposable element, heterochromatin, epigenetic, DDM1

Transposable elements are widespread constituents of all eukaryotic genomes. Discovered first in maize, transposons and retrotransposons occupy 50%–80% of this genome and frequently reach copy numbers of several thousand (SanMiguel et al. 1998; Fedoroff 1999). Most DNA transposons are no longer active and require an autonomous element in trans to transpose. In maize, _cis_-acting transposon regulatory mechanisms are thought to include DNA methylation. Transposase promoter sequences from McClintock's Activator and Suppressor-Mutator transposons, for example, are hypomethylated in the active state, although the rest of the element is methylated constitutively (Banks et al. 1988; Fedoroff 1999). In vitro, transposon DNA binds more efficiently to transposase when hemimethylated than when unmethylated or fully methylated, possibly because this marks recently replicated transposons in vivo (Kunze and Starlinger 1989). For these and other reasons, we have proposed that DNA methylation is a fundamental property of transposons that differentiates them from the remainder of the genome (Martienssen 1998; Rabinowicz et al. 1999).

Robertson's Mutator transposons in maize fall into six categories, which share highly similar 200-bp terminal inverted repeats (TIRs; Bennetzen 1996). The autonomous MuDR element in maize encodes two genes, mudrA and mudrB. The mudrA gene encodes the MURA transposase, the mudrB gene encodes a subsidiary protein (MURB) that is not essential for somatic excision in maize (Lisch et al. 1999; Raizada and Walbot 2000). Two alternatively spliced forms of MURA, 736 and 823 amino acids (aa) in length, are found in maize (Hershberger et al. 1995). The 823 aa MURA protein can effectively bind to a conserved region in the element TIRs (Benito and Walbot 1997) and therefore probably functions as transposase. Nonautonomous elements, further designated as _Mu_-elements, with intact inverted repeats are also mobilized by MURA, which binds to methylated, as well as unmethylated, motifs within the TIRs (Benito and Walbot 1997). Except for sharing similarity between TIRs, Mu elements are unrelated to MuDR and do not encode functional transposase. Both types of elements, MuDR and Mu, are heavily methylated in inbred strains of maize. In Mutator strains, which show a high degree of transposon activity, the TIRs of Mu elements such as Mu1 and Mu2, as well as the TIRs of MuDR, are hypomethylated. Because demethylation of TIRs in MuDR elements leads to high levels of transposase gene expression, it is thought that they contain the the transposase promoter (Chandler and Walbot 1986; Chomet et al. 1991; Martienssen and Baron 1994; Hershberger et al. 1995; Bennetzen 1996). Autonomous elements can spontaneously lose activity during development, a process accompanied by methylation of TIRs. This results in plants mosaic for cells containing methylated and unmethylated elements (Martienssen et al. 1990; Martienssen and Baron 1994).

The maize and Arabidopsis genomes differ in their organization. Transposable elements in maize (especially retroelements) are the primary constituent of intergenic DNA, outnumbering genes at least four to one (SanMiguel et al. 1998). In contrast, genes outnumber transposons by five to one in Arabidopsis, and most transposons are confined to pericentromeric heterochromatin (Lin et al. 1999; Mayer et al. 1999). Recently, an interstitial region of heterochromatin resembling a maize chromomere, or knob, has been completely sequenced (Consortium 2000). The knob was found to be composed of DNA transposons (15%), retrotransposons (35%), and other repeats (21%); the remaining 29% was composed of largely silent genes. Thus, the knob region more closely resembles the maize genome than the remainder of the Arabidopsis genome. Transposons and repeats were found to be heavily methylated within the knob as they are in maize.

We set out to investigate transposon methylation in plants by isolating mutants with decreased DNA methylation (ddm) in Arabidopsis (Vongs et al. 1993). DDM1 is required for methylation of tandem repeats at the centromere and at the nucleolar organizer (Vongs et al. 1993), as well as at the heterochromatic knob (Consortium 2000). This gene encodes a SWI2/SNF2 chromatin-remodeling factor (Jeddeloh et al. 1999), and loss-of-function ddm1 mutations lead to immediate loss of DNA methylation from heterochromatin and gradual loss from euchromatin over successive generations of inbreeding (Kakutani et al. 1999). Here, we examine the impact of ddm1 on transposon activity.

Mutator-like elements are widespread constituents of the Arabidopsis genome

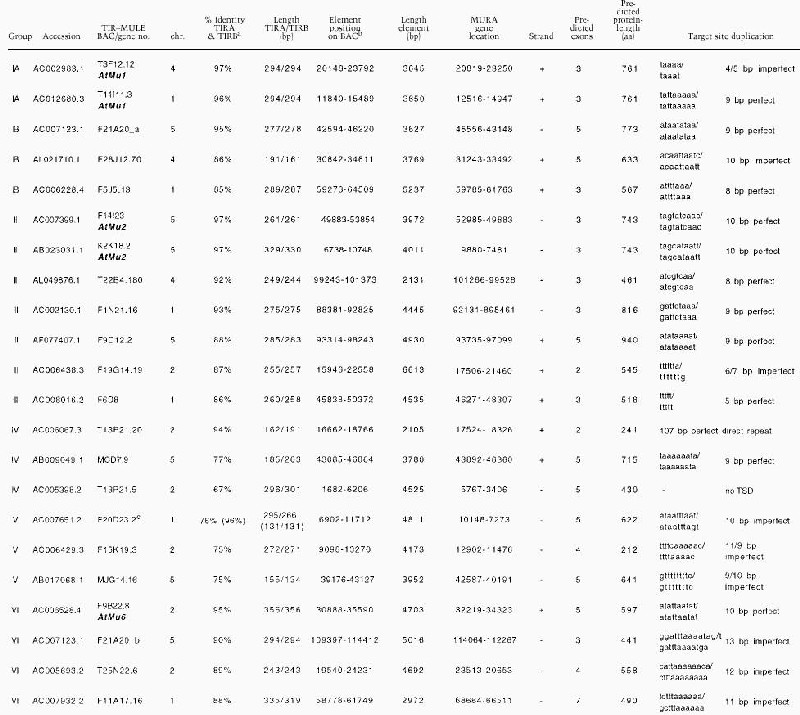

We performed text queries and sequence-similarity searches of the Arabidopsis genome to catalog all ORFs related to the MURA transposase of MuDR from maize. More than 200 individual ORFs were found in 90 Mb of completed sequence. We narrowed our search further to elements structurally related to MUDR with long TIRs and harboring intact transposase genes that might still be able to transpose. Therefore, we analyzed the flanking regions of all mined sequences with homology to the mudrA gene in order to identify TIR-sequences. Only 22 ORFs encoding a putative MURA transposase were flanked by long TIRs, as is the case with MuDR in maize (Table 1A). Unlike maize MuDR elements, none of the _Arabidopsis Mutator_-like elements encode a protein resembling MURB.

Table 1A.

Summary of TIR–MULEs in Arabidopsis.

In a recent study, 108 _Mutator_-like elements were identified in 17.2 Mb of finished Arabidopsis sequence (Le et al. 2000). These investigators coined the term MULE (_Mutator_-like element) to describe genes with homology to the mudrA transposase gene and related repeats and refer to _Mutator_-like elements with long TIRs as TIR-MULEs (http://soave.bio.mcgill.ca/clonebase/). We have adopted this nomenclature, although only 4 of the 22 TIR-MULEs we identified can be found in their study (T3F12.12 [_AtMu1_] = MULE16, gi2443899; F28J12.70 = MULE3, gi2832639; F1N21.16 = MULE24A; F9D12.2 = MULE24B, gi3319339). We have named individual elements (AtMu1, AtMu2, etc.) which are capable of transcription or transposition, consistent with the practice in maize, snapdragon, and other plants. Because we were only interested in identifying putatively intact transposons, ∼200 MULEs in which no TIRs could be identified were not considered further, and we did not search for _Mu_-like elements with homology only to TIR sequences.

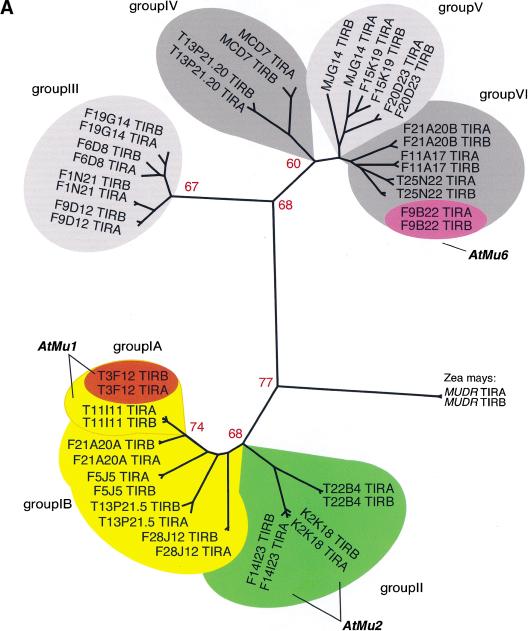

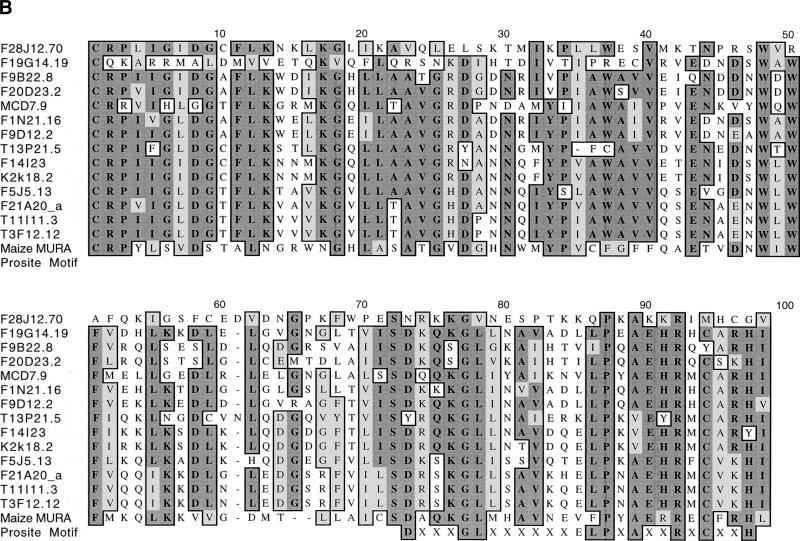

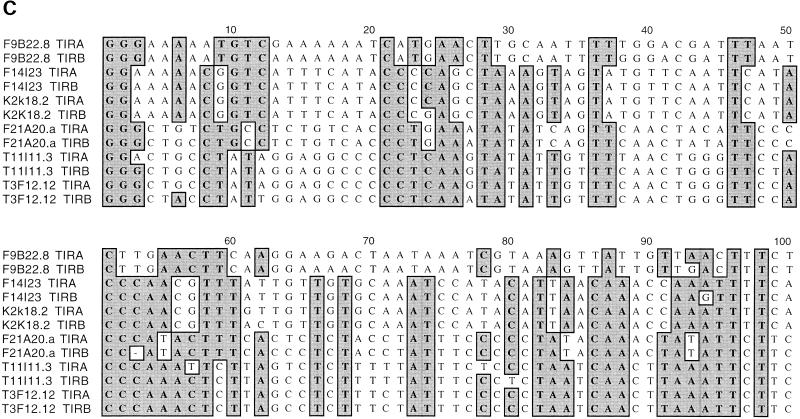

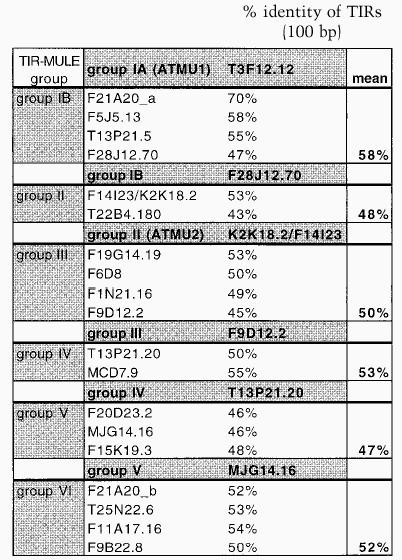

Analysis of TIR and transposase homologies

Cluster analysis of the inverted repeats (Fig. 1A, Table 1B) and of the transposase genes (Fig. 1B) showed that the Arabidopsis TIR-MULEs fell into six groups. The individual elements were single-copy, except that two copies of the AtMu1 element were found on chromosomes 1 (T11I11.3) and 4 (T3F12.12, together designated as subgroup IA), two copies of AtMu2 were found on chromosome 5 (F14I23, K2K18.2; group II), and element F20D23.2 (group V) has four copies in the Columbia genome (data not shown). Both elements of the AtMu1 class (T3F12.12, T11I11.3) and both of the AtMu2 class (F14I23, K2K18.2) share 98% sequence identity on the nucleotide and amino acid level. Bacterial and maize mudrA genes share a 25-aa signature sequence [D-x(3)-G-(LIVMF)-x(6)-(STAV)-(LIVMFYW)-(PT)-x-(STAV)-x(2)(QR)-x-C-x(2)-H] found in a highly conserved 130-aa domain (Eisen et al. 1994). The AtMu1 (T3F12.12, T11I11.3) and AtMu2 (K2K18.2, F14I23) elements differ from this signature at a single-residue—E instead of V at position 13 of the motif (Fig. 1B). Because those elements most likely encode functional transposase (see results below), we propose an extended consensus pattern [D-x(3)-G-(LIVMF)-x(6)-(_E_STAV)-(LIVMFYW)-(PT)-x-(STAV)x(2)-(QR)-x-C-x(2)-H]. The predicted AtMu1 transposase has 36% similarity and 25% identity to the MURA transposase from maize. The remaining TIR-MULEs might be defective as a result of mutations in the conserved region of MURA or because they encode truncated transposase proteins (Fig. 1B, Table 1A).

Figure 1.

Analysis of _Mutator_-like elements with long terminal inverted repeats (TIR-MULEs) in Arabidopsis. (A) Unrooted distance tree of the 22 TIR-MULEs identified in this study (Table 1A,B) based on terminal inverted repeat (TIR) sequences. _Mutator_-like elements with TIRs (TIR-MULEs) have been grouped by similiarty according to the cluster analysis. Elements that transpose in ddm1 strains are highlighted in red (AtMu1) and purple (AtMu6). Bootstrap values are indicated at nodes. Subgroups IA and IB (yellow) and group II (green) contain elements which are transcribed in ddm1 mutants (see Table 2). (B) Alignment of a 97-aa conserved region of the Arabidopsis MURA-like transposases with the maize MURA protein. Identical amino acids are boxed in dark grey, similar in light grey. Identical amino acids from the PROSITE signature pattern are shown below the corresponding sequence. (C) Alignment of TIR sequences of transcribed elements. Identical nucleotides are boxed in grey (TIRA, 5′ TIR; TIRB, 3′TIR).

Table 1B.

Comparison of TIRs between related TIR–MULE groups

The right and left TIR sequences of the TIR-MULEs vary in length (130 bp–356 bp) and show varying degrees of conservation. In pairwise comparisons, all TIRs—with one exception (MJG14.16)—are more closely related to each other than to any other TIR of another element (Fig. 1A). TIRA of the element MJG14.16 is more closely related to the TIRs of F15K19.3 than to its own TIRB (Fig. 1A). TIRs of individual elements share a minimum sequence identity from 67% (T13P21.5) to 97%. (Table 1A). The most conserved TIRs, with 96%–97% sequence identity, are those of the AtMu1 (T3F12.12, T11I11.3) and AtMu2 (F14I23, K2K18.2; Fig. 1C). All TIR-MULEs start or end with 1–4 G nucleotides. Figure 1C shows an alignment of the first 100 bp of TIRs of those TIR-MULEs that are transcribed and show the highest sequence similarity between both TIRs.

No significant similarity to the MURA transposase-binding site in maize predicted by Benito and Walbot (1997) could be identified in any of the TIR-MULE sequences. According to the cluster analysis of multiple-sequence alignments, the TIR-MULEs can be classified in two main lineages: one class comprising groups I–II, the other class containing groups III–VI (Fig. 1A). Elements belonging to neighboring groups share ∼50% sequence identity (Table 1B). Assuming that highly conserved pairs of TIRs are an essential requirement for transposase binding and, hence, transposition, elements with a low level of sequence identity in their TIR sequences might no longer be transactivated and therefore are probably nonfunctional. For that reason and the observed divergence between TIR-groups, the tree very likely does not reflect an evolution of different functional groups of elements but rather different stages of degeneration. We, therefore, cannot derive a meaningful consensus sequence from multiple-sequence alignments of all TIRs in order to determine conserved MURA-binding sites. Experimental analysis of TIR sequences of elements still capable of transposition, however, will undoubtedly reveal motifs important for MURA binding. Nearly all of the TIR-MULEs (20 of 22) were inserted between short direct repeats, which varied between 8 bp and 13 bp (Table 1A). Five of the TIR-MULEs were flanked by perfect 9-bp repeats (Table 1A), similar to the 9-bp target-site duplications (TSD) found in maize. One element (T13P21.20) was flanked by identical 107 bp repeats on either side. Imperfect TSDs may have resulted from local rearrangement following transposition (Taylor and Walbot 1985; Das and Martienssen 1995) or random mutation after the transposition event.

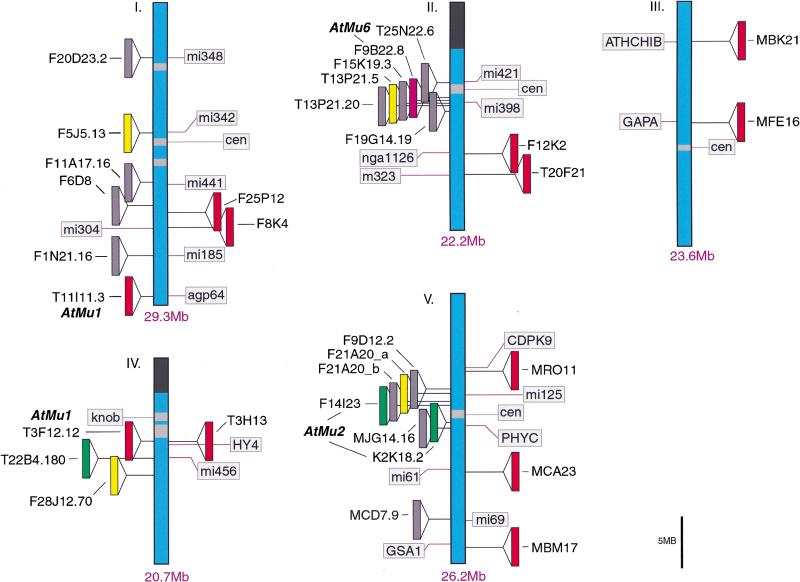

The locations of each of the TIR-MULEs are shown in Figure 2. Six TIR-MULEs are distributed along chromosome I. On chromosomes 2, 4, and 5, 13 out of 16 TIR-MULEs were found within 2 Mb of the centromeric repeats. On chromosome 4, one copy of AtMu1 was found where pericentromeric heterochromatin has been cytologically defined (Fransz et al. 2000). This bias toward heterochromatin was even more pronounced among non-TIR elements (Consortium 2000).

Figure 2.

Genomic locations of TIR-MULE transposons. Potentially intact elements with TIRs in the Columbia ecotype are shown to the left of each chromosome. Transposed AtMu1 elements in ddm1 strains are shown on the right (Table 3). Genetic markers and map positions, as well as pericentromeric (light grey) and nucleolar (dark grey) heterochromatin, are shown. TIR-MULE subfamilies are color-coded as in Fig. 1A.

MULEs are regulated by DDM1

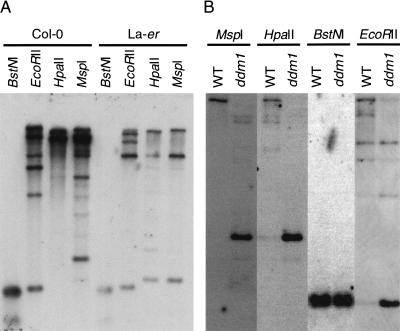

For further analysis, at least one representative element from each group was selected that had either long or well conserved TIRs (85%–97% sequence identity over at least 130 bp) or encoded potentially full-length transposase (743–773 aa). TIR-MULE F15K19.3, however, has only 75% sequence identity between TIRs and encodes very likely a truncated protein of 212 aa. In total, we tested 12 elements: two from group IA (T3F12.12, T11I11.3), two from group IB (F21A20_a, F5J5.13), three from group II (F14I23, K2K18.2, T22B4.180), one from group III (F9D12.2), one from group IV (T13P21.20), two from group V (F20D23.2, F15k19.3), and one from group VI (F9B22.8; Tables 1A, 2). DNA gel blots indicated that all elements were partially methylated at _Hpa_II and _Eco_RII restriction sites in the Columbia and Landsberg ecotypes (Fig. 3; data not shown). Overexposure of these blots indicated that AtMu1 was less methylated in Landsberg erecta (Fig. 3A). In both Columbia and Landsberg background, all 12 elements were hypomethylated in ddm1 mutants (Fig. 3B; data not shown). Hypomethylation was apparent in pooled F3 seedlings from self-pollinated homozygous mutants in the F2 generation and did not change further in subsequent generations. Thus, TIR-MULEs are a primary target of DDM1.

Figure 3.

Mutator transposons are methylated in Arabidopsis. DNA gel blot analysis of Arabidopsis DNA from (A) wild-type Landsberg erecta (La-er) and Columbia strains (Col-0) and (B) wild-type and ddm1 mutant plants (cv. Columbia) digested with _Eco_RII, _Bst_NI, _Hpa_II, and _Msp_I. The blots were hybridized with probe 2 from AtMu1 (Fig. 4A).

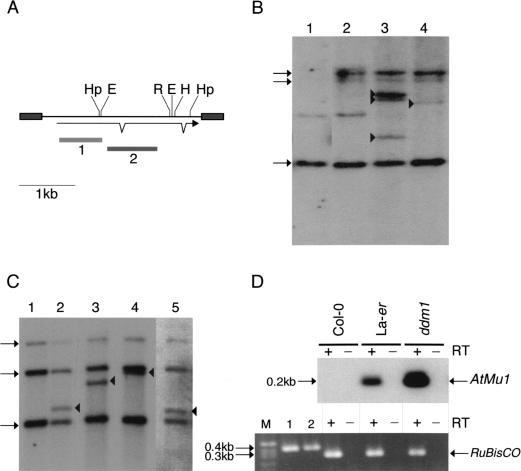

Transcription of TIR-MULE transposase genes was examined by RT–PCR. In wild-type Columbia plants, no transcripts could be detected for any of the elements. In ddm1 mutant plants, both copies of AtMu1 (Fig. 4A), both copies of the group II element AtMu2, and one other group IB element (F21A20_a) were transcribed (Fig. 4D; Table 2; data not shown). Bona fide transcription was confirmed by sequencing the RT–PCR products from AtMu1 and showing accurate splicing (see Materials and Methods). Interestingly, although only one AtMu1 element (T3F12.12) was present in Landsberg erecta (Fig. 4B), it was transcribed in _DDM1_+ plants (Fig. 4D). The same was true of AtMu2, which is located near the centromere of chromosome 5 (Table 2). Thus, Landsberg erecta and Columbia differ in the regulation of TIR-MULE transcripts.

Figure 4.

Mutator transposons are activated in ddm1 mutants.(A) AtMu1 has 295 bp TIRs (grey boxes) and encodes three exons; probes 1 and 2 are indicated below. Restriction enzyme sites for _Hpa_II (Hp), _Hin_dIII (H), _Eco_RI (R), and _Eco_RII (E) are shown. (B) DNA gel blot analysis of pooled wild-type and _ddm1_-mutant seedlings. DNA was digested with _Eco_RI and hybridized with probe 2. New bands (arrowheads) represent transposition of AtMu1. The preexisting elements T11I11.3, F21A20_a, and T3F12.12 are indicated by arrows on the left. The faint band in lanes 1 and 2 is partially methylated T3F12.12. Lane 1, Landsberg erecta (Ler); lane 2, Columbia wild-type (Col-0); lane 3, Columbia ddm1; lane 4, Landsberg erecta ddm1. (C) DNA gel blot analysis of individual Columbia ddm1 plants using _Hin_dIII and probe 1. New bands (arrowheads) are transposed AtMu1. (D) RT–PCR analysis (+) of transcripts using AtMu1 primers (top panel) and control RuBisCO primers (bottom panel). Alternate lanes (−) are mock reactions in the absence of reverse transcriptase. RuBisCO lanes 1 and 2 were amplified using Col-0 and Ler genomic DNA.

Table 2.

Methylation, transcription, and transposition of selected TIR–MULEs in Arabidopsis.

| TIR–MULE | chr. | Copy number | Methylation | Transcription | Transposition events | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Col-0 | La-er | Col WT | Col ddm1 | Col WT | Ler WT | Col ddm1 | Col WT | Ler WT | Col ddm1 | Ler ddm1 | ||

| T3F12.12/ T11I1.3 AtMu1 | 4, 1 | 2 | 1 | + | − | − | + | + | 0/88 | 1/122 | 11/85 | 6/36 |

| F21A20_a | 5 | 1 | 0 | + | − | − | − | + | 0/62 | N.D. | 0/50 | N.D. |

| F14I23/K2K18.2 AtMu2 | 5 | 2 | 2 | + | − | − | + | + | N.D. | N.D. | 0/35 | N.D. |

| T22B4.180 | 4 | 1 | 0 | +/− | − | − | − | − | N.D. | N.D. | 0/26 | N.D. |

| T13P21.20 | 2 | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | − | − | N.D. | N.D. | 0/35 | N.D. |

| F20D23.2 | 1 | 4 | 2 | +/− | − | − | − | − | N.D. | N.D. | 0/26 | N.D. |

| F5J5.13 | 1 | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | − | − | N.D. | N.D. | 0/26 | N.D. |

| F15K19.3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | + | − | − | − | − | N.D. | N.D. | 0/26 | N.D. |

| F9B22.8 AtMu6 | 2 | 1 | N.D. | + | +/− | +a | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | 1/54 | N.D. |

| F9D12.2 | 5 | 1 | N.D. | + | − | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | 0/40 | N.D. |

None of the other transposase genes tested by PCR was transcribed by this assay. Expressed sequence tags (AC701558554 and H7A1T7) were found corresponding to a group-VI element (F9B22.8, AtMu6) located near the centromere of chromosome 2, which was not tested by RT–PCR (Table 2). In pairwise comparisons, all the transcribed elements share at least 95% similarity between both TIRs (Table 1A). Because multiple elements are transcribed, it is not possible to assign any one element as the source of functional transposase in ddm1 mutants.

DNA gel blots revealed that AtMu1 was stable in >80 individual wild-type plants from Columbia (Table 2). Thirteen percent of individual ddm1 plants had novel AtMu1 bands suggestive of transpositions (Fig. 4B,C). These bands were not found in parental Columbia DNA (Fig. 4B,C). In Landsberg, rare transpositions (1%) were detected in wild-type plants (consistent with transcription in this ecotype) but were much more frequent (16%) in ddm1 mutants (Table 2). These frequencies of transposition are comparable to rates found for individual _Mu_-elements in minimal Robertson's _Mutator-_lines in maize, which are equivalent to those described here (Lisch et al. 1995). In more active maize lines with multiple elements, transposition frequencies are 2–5 times higher, and Mu elements are also found as extrachromosomal circles (Sundaresan and Freeling 1987). We tested for such circles in Arabidopsis by DNA gel blot analysis of undigested Arabidopsis DNA but failed to detect them (data not shown). One possibility is that circular forms are transposition intermediates that require the MURB that is only found in maize. Alternatively, low copy number may prohibit detection.

In plants that did have transposed elements, no evidence of germinal excision was observed, either by Southern blotting or PCR among 25 progeny carrying the transposed element (data not shown). This suggests that germinal insertions occur without germinal excision, just as they do in maize. Further experiments using selectable assays for germinal excision are needed to make this conclusion more robust. The AtMu6 element F9B22.8 was transcribed but transposed only rarely in ddm1 mutants (Table 2). The transposase gene in this case is lacking the first 190 amino acids and may be nonfunctional, suggesting that this element is activated in trans.

Flanking sequences were amplified from 10 AtMu1 transpositions by adapter-ligation PCR (AIMS) and sequenced to determine their location in the genome. Insertions were verified by DNA gel blot analysis of progeny plants using the flanking sequence (data not shown) and AtMu1 as probes (Fig. 4). Amplification with element-specific primers and primers from either side of the AtMu1 insertion site, followed by sequencing of the PCR products, confirmed the location of insertions. In all cases examined, it was the AtMu1 element on chromosome 4 (T3F12.12) that had transposed. For eight of these sequences, the insertion site could be mapped to the nucleotide, and they all generated 9-bp insertion-site duplications (Table 3). One transposition integrated between T3H13.5 (HY4) and T3H13.6, only 176 kbp distal from the AtMu1 copy on chromosome 4. The other transpositions were unlinked to the parental AtMu1 element. Consistent with these results, Mutator elements in maize do not preferentially transpose to linked sites (Lisch et al. 1995). In this small sample, there were no biases against integration within repeats, promoters, or retrotransposons. None of the transpositions disrupted predicted coding regions, but integration of 6 out of 10 AtMu1 elements within 200 bp–1500 bp upstream of predicted start codons indicated possible promoter disruption (Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of transposed AtMul elements and insertion sites in ddm1 mutant plants.

| _ddm1_-line | Ecotype | Generation | chr. | Gene nearest to insertion | Accession | Orientation of TIR–MULE | Comments | Target site duplication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4853/7 | Col-0 | F3 | 1 | F25P12.97 | AC009323.4 | 5′-3′ | hypothetical protein, 222bp upstream | ttaaatctt (9bp) |

| 4853/155 | Col-0 | F3 | 2 | T20F21.11 | AC006068.3 | 3′-5′ | AP2 domain transcription factor 317bp downstream | aagtttttc (9bp) |

| 4853/48 | Col-0 | F3 | 2 | F12K2.19 | AC006233.3 | 3′-5′ | unknown protein, 774bp upstream | ttatttaaa (9bp) |

| 4855/4 | Col-0 | F5 | 4 | T3H13.5 | AF128396.1 | 3′-5′ | retrotransposon 2524bp from HY4 | aatttatta (9bp) |

| 4853/6 | Col-0 | F3 | 5 | MBM17.4 | AB019227.1 | 3′-5′ | protein kinase, 414bp upstream | aagattctt (9bp) |

| 4853/154b | Col-0 | F3 | 5 | MRO11.11 | AB005244.2 | 3′-5′ | unknown protein 290bp upstream | aagtatcaa (9bp) |

| 4220/11b | Col-0 | F6 | 5 | MCA23.3 | AB016886.1 | N.D. | GTPase activating protein | N.D.a |

| 4574/21 | La-er | F3 | 1 | F8K4.9 | AC004392.1 | 5′-3′ | hypothetical protein 800bp upstream | agtattatt (9bp) |

| 4575/21 | La-er | F4 | 3 | MBK21.21 | AB024033.1 | 5′-3′ | putative auxin-regulated protein 1423bp upstream | ttttttttt (9bp) |

| 204/7b | La-er | F5 | 3 | MFE16.2 | AB028611.1 | N.D. | Unknown protein, downstream | N.D.a |

Role of transposons in epigenetic regulation and genome organization

DDM1 is required for silencing of methylated and repeated genes in Arabidopsis (Jeddeloh et al. 1998, 1999; Paszkowski and Mittelsten Scheid 1998), which may resemble cryptic heterochromatin (Consortium 2000). For example, DDM1 mediates silencing of the PAI2 locus by an inverted duplication at the unlinked PAI1 locus (Bender and Fink 1995; Jeddeloh et al. 1998). This type of allele-specific gene silencing resembles paramutation in maize (Brink et al. 1968; Kermicle 1996; Martienssen 1996), which may involve transposons and repeats because of their influence on the expression of neighboring genes (McClintock 1965; Martienssen et al. 1990; Barkan and Martienssen 1991; Martienssen 1996; Matzke and Matzke 1998).

Repeated transgenes encoding tobacco retrotransposons also undergo silencing in Arabidopsis, and like other silent transgenes, this silencing can be reversed in ddm1 mutants (Hirochika et al. 2000). Importantly, however, only 1 of 20 endogenous retrotransposons (Tar17) was found to be transcribed in ddm1 mutants, and it does not transpose at all (Hirochika et al. 2000). In a similar study, a truncated Athila transcript was induced in ddm1 mutants, but it did not transpose and no other retrotransposons were affected (Steimer et al. 2000). Therefore, we conclude that DDM1 has little effect on retrotransposons in Arabidopsis. In the mouse, IAP (Intracisternal A Particle) retroelements are transcribed in DNA methyltransferase (dnmt1) mutants, but transposition has not been assessed (Walsh and Bestor 1999). Nearby genes can be regulated by IAP elements (Morgan et al. 1999) suggesting that retrotransposons may mediate some of the effects of demethylation (Martienssen and Richards 1995).

We have shown that TIR-MULEs in Arabidopsis are quiescent and do not transpose in the Arabidopsis strain Columbia. Quiescence is correlated with DNA methylation and a lack of transcription, although nearly identical copies of some elements may have transposed in the recent past. In contrast, TIR-MULEs are transcribed at low levels and transpose occasionally in Landsberg erecta, in which they have lower levels of DNA methylation. In loss-of-function ddm1 mutants, transposon methylation was eliminated in both strains and AtMu1 was activated resulting in high levels (10%–20% per generation) of transposition. Given the predicted function and phenotype of DDM1, chromatin remodeling and DNA methylation are therefore likely required for transcriptional, as well as transpositional, repression of potentially active autonomous elements. Other TIR-MULEs appear to be defective and incapable of activation.

Interestingly, Tar17, Athila, AtMu1, and AtMu2 are all located in pericentromeric heterochromatin, within a few hundred kilobase of centromeric satellite repeats, and are all transcriptionally activated in ddm1 mutants. Therefore, some feature of heterochromatin that depends on chromatin remodeling may be responsible for transposon regulation. McClintock (1951) first noted that heterochromatin underwent the same types of rearrangement as those induced by transposons. Dotted, one of the first transposons to be discovered in maize by Rhoades, was mapped to the heterochromatic knob on chromosome 9S (McClintock 1951). Dotted and other elements were activated by heterochromatic changes during the breakage-fusion-bridge (BFB) cycle (McClintock 1951, 1984), and activation of heterochromatic transposons might account for genome instability in these plants (McClintock 1951). Recently, mutations in the human homolog of DDM1, the X-linked alpha-thalassemia gene ATRX, were shown to cause heterochromatic demethylation in a parallel manner (Gibbons et al. 2000). It will be interesting to see if human transposons are activated in these patients.

The mutator phenotype observed in ddm1 lines (Kakutani et al. 1996) may be caused in part by transposition of TIR-MULEs into or near genes, but this transposon group is unlikely to account for the high frequency with which certain mutations arise in independent ddm1 lines. When maize Mutator elements are inserted into promoters and introns, methylation can promote gene expression, suppressing the original mutant phenotype (Barkan and Martienssen 1991; Bennetzen 1996; Settles et al. 2001). Pre-existing insertions of MULEs, therefore, would be expected to repress nearby genes in ddm1, resulting in a high frequency of epimutations at specific loci (Martienssen 1998). This model leads us to speculate on the difference between the maize and Arabidopsis genomes. Maize may be defective in certain components of the chromatin-remodeling complex that normally represses transposon activity (Martienssen and Henikoff 1999). For example, active Mutator lines may have trans-acting mutations, similar to ddm1, that result in the coordinate repression of multiple genes (Martienssen 1998). These mutations might influence other transposons also, consistent with the recovery of Suppressor-Mutator insertions in Robertson's Mutator strains in maize (Chandler et al. 1989; E. Vollbrecht and R.A. Martienssen, unpubl.). Insertional mutations are expected to display extensive polymorphism in different genetic backgrounds, depending on the pattern of transposon insertion. Inbreeding would exacerbate these effects as observed for ddm1 (Kakutani et al. 1996), whereas mutations in different strains would complement each other, resulting in hybrid vigor (Martienssen 1998).

Material and methods

Plant material

The ddm1-2 mutation which was used in this study was identified in the Columbia ecotype (Vongs et al. 1993). Homozygous seed (var. Columbia) were obtained by self-pollinating heterozygotes that had been backcrossed for at least eight generations (E. Richards, Washington University). Individual progeny were genotyped by DNA blot analysis (Vongs et al. 1993) and a homozygous mutant selected for self-pollination. Heterozygotes were backcrossed for six generations into Landsberg erecta and genotyped by progeny testing before selecting the next backcross. The plants were self-pollinated to obtain homozygotes, and individual F3 to F6 progeny were examined for DNA methylation and transposition.

Informatics

GenBank and TAIR (http://www.arabidopsis.org/blast) databases were searched, most recently in December 1999, using the key words Mutator, MuDR, and MuRA. The predicted _AtMu1 mudrA_-like transposase T3F12.12 was used to perform TBLASTN (BLOSUM62) and PSI-BLAST (BLOSUM45) searches of plant sequences with two rounds of iteration (Altschul et al. 1997). Gene models of unannotated _Mutator_-like elements were predicted with Genscan (http://CCR-081.mit.edu/GENSCAN.html). TIRs were located by aligning 4 kb of either side of the presumed coding sequence with BLAST2 (Tatusova and Madden 1999). Conserved 100-bp regions from the TIRs of each element were aligned using PILEUP (GCG 10.0, Madison, WI). Distance trees (GrowTree) used the UPGMA and the Tamura algorithms for correction. Parsimony trees were constructed heuristically using PAUP*4.0.0d55 and the maize MuDR element at waxy (Accession no. M76978) as the outgroup.TreeViewPPC Version 1.6.2 (Page 1996) was obtained at http://taxonomy.zoology.gla.ac.uk/rod/rod.html. CLUSTALW analysis of a conserved 98-aa domain from the MURA transposase (Fig. 1B) was performed using MacVector6.5.1 (Oxford Molecular Group) and the BLOSUM30 matrix.

DNA and RNA analysis

Seedling, leaf, or inflorescence DNA was purified and subjected to DNA gel blot analysis as described by Vongs et al. (1993). Hybridization probes specific for AtMu1 elements were obtained by amplifying parts of the MuRA gene using the following primers: probe 1, 5′-GTCGAGTACAATGGGGGTAAC-3′ and 5′- CAACAGACCCTGGGTTTTGAG-3′; probe 2, 5′-CC GAGAACTGGTTGTGGTTT-3′ and 5′-TGGTGGCTGTCTC ATAGCTG-3′.

RNA was isolated from pooled F4 or F5 20-d seedlings using Trizol reagent (Life Technologies) and DNAse treated with RQ1 DNAse according to the manufacturer. RT–PCR was performed using the OneStep RT–PCR Kit (Qiagen). RNA quality and concentration were determined by gel analysis and absorbance; 2μg of total RNA was reverse transcribed and then dilutions of the resulting cDNA were amplified using control primers for the RuBisCO gene to ensure even loading. RT–PCR was performed using primers from each of the AtMu exons. For AtMu1 these primers were T3F12.12: 5′-CCGAGAACTGGTTGTGGTTT-3′, 5′-GCTCTTGCTTTGGTGATGGT-3′ (spanning intron 1), 5′-CAAGAGCTGTGGTGAAGCTG-3′, 5′-TGCTTGAGAAG GTTGTGTGATG-3′ (spanning intron 2); T11I11.3: 5′-CGCAC CACCAGAACCTATTT-3′, 5′-CTTGAGAAGGTTGTGTGAT A-3′; T11I11.3 nested: 5′-GAAGCTGGGCATAACGCATT AG-3′, 5′-TCCTTCTTAGAGTTCTTCTCATC-3′. Other primer sequences are available on request. PCR products were directly sequenced using dye terminators on ABI Prism 377 sequencers. The sequences of the RT–PCR products are shown below. Exon borders correspond to the predicted splice sites of AtMu1.

Exon borders 1 and 2: Ler WT, 5′-TCTTTCAGACCGCT CAAAG/GGTCTTCTGAGTGCTGTT-3′; ddm1(Col), 5′-TCT ATCAGATCGCTCAAAG/GGTCTTCTGAGTGCTGTT-3′. Exon borders 2 and 3: Ler WT, 5′-GAATGATGGCAATGAT GAG/ATTGAAAAGAAGGCTAAG-3′; ddm1(Col), 5′-GAAT GATGGCAATGATGAG/ATTGAAAAGAAGGCTAAG-3′. (The splice-site junction is marked with a slash. Exon borders are underlined.)

RT–PCR products were transferred to Nylon N+-membranes (Amersham) and hybridized with genomic probes obtained with the same primer pairs as used for RT–PCR.

Amplification of flanking sequences

Insertion sites were amplified using a modification of the AIMS technique (Frey et al. 1998) and using the following adapter oligonucleotides and primers: Adapter-upper, 5′-GA CTCATGCTTACCTAGTCCAGTTGACAGTACCATATG-3′; Adapter-lower, 5′-ATTGGAGTCTGGTATACAT-3′ (phosphorylated at the 5′ end). Adapter primer 1 (AD-AIMS1), 5′-GACTCATGCTTACCTAGTCCAG-3′; Adapter primer 2 (ADAIMS2), 5′-GACTCATGCTTACCTAGTCCAGTTG-3′. AtMu1 specific primers: AtMu1_TIR150, 5′-GCTTGATTAATGTTG GTTAATTAC-3′ (primer binds both TIRs); AtMu1_TIRA1, 5′GGGTGGAACCCAGTTGAAACAATATAC-3′; AtMu1_TIRA2, 5′-TTGAAACAATATACTTGAGGGGGG-3′; AtMu1_TIRB1, 5′-GGGTGGAACCCAGTTGAAACAATATAT-3′; AtMu1_TIRB2, 5′-TTGAAACAATATATTTGAGGGGGC-3′, (primers bind either TIRA or TIRB). Upper and lower adapters were denatured and annealed in equimolar amounts at room temperature for >4 h. Genomic DNA (100–300 ng) was cut with _Bfa_I and ligated with 50 pmole reconstituted adapter for 1 h at room temperature and 2 h at 37°C. The ligation was purified with spin columns (Qiagen) and one-tenth of the purified reaction was subjected to the PCR, using AD-AIMS1 and the specific AtMu primers and using the same cycling conditions as for secondary TAIL PCR (Liu et al. 1995), except that the buffer was supplemented with 3% DMSO. Annealing temperature was varied according to the primer 64°C (AtMu1_TIRA1/AtMu1_TIRB1) or 55°C (AtMu1_TIR150). Products were gel purified or diluted 1/100 before reamplification with the second primer pair, using 35 cycles and a 60°C annealing temperature.

Acknowledgments

We thank Eric Richards for helpful advice and for seed; Lehka Das for the Landsberg backcrosses; Lawrence Parnell, Kristin Schutz, Lei Hoon See, and W. Richard McCombie for sequence analysis; Monika Frey and Cornelia Stettner for the AIMS protocol prior to publication; and the anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the Department of Energy (DE-FG02–91ER20047) and the National Science Foundation.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Note added in proof

While this manuscript was under review, a computational analysis of some of the _Mutator_-like elements in the Arabidopsis genome was published (Yu et al. 2000).

Footnotes

E-MAIL martiens@cshl.org; FAX (516) 367-8369.

Article and publication are at www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.193701.

References

- Altschul SF, Madden TL, Schaffer AA, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman DJ. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: A new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banks JA, Masson P, Fedoroff N. Molecular mechanisms in the developmental regulation of the maize Suppressor-mutator transposable element. Genes & Dev. 1988;2:1364–1380. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.11.1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkan A, Martienssen RA. Inactivation of maize transposon Mu suppresses a mutant phenotype by activating an outward-reading promoter near the end of Mu1. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1991;88:3502–3506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.8.3502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender J, Fink GR. Epigenetic control of an endogenous gene family is revealed by a novel blue fluorescent mutant of Arabidopsis. Cell. 1995;83:725–734. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90185-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benito MI, Walbot V. Characterization of the maize Mutator transposable element MURA transposase as a DNA-binding protein. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:5165–5175. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.9.5165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennetzen J. The Mutator transposable element system of maize. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1996;204:195–229. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-79795-8_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brink RA, Styles ED, Axtell JD. Paramutation: Directed genetic change. Paramutation occurs in somatic cells and heritably alters the functional state of a locus. Science. 1968;159:161–170. doi: 10.1126/science.159.3811.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler VL, Walbot V. DNA modification of a maize transposable element correlates with loss of activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1986;83:1767–1771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.6.1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler VL, Radicella JP, Robbins TP, Chen J, Turks D. Two regulatory genes of the maize anthocyanin pathway are homologous: Isolation of B utilizing R genomic sequences. Plant Cell. 1989;1:1175–1183. doi: 10.1105/tpc.1.12.1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomet P, Lisch D, Hardeman KJ, Chandler VL, Freeling M. Identification of a regulatory transposon that controls the Mutator transposable element system in maize. Genetics. 1991;129:261–270. doi: 10.1093/genetics/129.1.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consortium, C.W.P.A.S. (The Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Washington University Genome Sequencing Center, and PE Biosystems Arabidopsis Sequencing Consortium) The complete sequence of a heterochromatic island from a higher eukaryote. Cell. 2000;100:377–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das L, Martienssen R. Site-selected transposon mutagenesis at the hcf106 locus in maize. Plant Cell. 1995;7:287–294. doi: 10.1105/tpc.7.3.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen JA, Benito MI, Walbot V. Sequence similarity of putative transposases links the maize Mutator autonomous element and a group of bacterial insertion sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:2634–2636. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.13.2634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedoroff NV. The suppressor-mutator element and the evolutionary riddle of transposons. Genes Cells. 1999;4:11–19. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1999.00233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fransz PF, Armstrong S, de Jong JH, Parnell LD, van Drunen C, Dean C, Zabel P, Bisseling T, Jones GH. Integrated cytogenetic map of chromosome arm 4S of A. thaliana: Structural organization of heterochromatic knob and centromere region. Cell. 2000;100:367–376. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80672-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey M, Stettner C, Gierl A. A general method for gene isolation in tagging approaches: Amplification of insertion mutagenised sites (AIMS) Plant J. 1998;13:717–721. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons RJ, McDowell TL, Raman S, O'Rourke DM, Garrick D, Ayyub H, Higgs DR. Mutations in ATRX, encoding a SWI/SNF-like protein, cause diverse changes in the pattern of DNA methylation. Nat Genet. 2000;24:368–371. doi: 10.1038/74191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershberger RJ, Benito MI, Hardeman KJ, Warren C, Chandler VL, Walbot V. Characterization of the major transcripts encoded by the regulatory MuDR transposable element of maize. Genetics. 1995;140:1087–1098. doi: 10.1093/genetics/140.3.1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirochika H, Okamoto H, Kakutani T. Silencing of retrotransposons in Arabidopsis and reactivation by the ddm1 mutation. Plant Cell. 2000;12:357–369. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.3.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeddeloh JA, Bender J, Richards EJ. The DNA methylation locus DDM1 is required for maintenance of gene silencing in Arabidopsis. Genes & Dev. 1998;12:1714–1725. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.11.1714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeddeloh JA, Stokes TL, Richards EJ. Maintenance of genomic methylation requires a SWI2/SNF2-like protein. Nat Genet. 1999;22:94–97. doi: 10.1038/8803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakutani T, Jeddeloh JA, Flowers SK, Munakata K, Richards EJ. Developmental abnormalities and epimutations associated with DNA hypomethylation mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1996;93:12406–12411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.22.12406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakutani T, Munakata K, Richards EJ, Hirochika H. Meiotically and mitotically stable inheritance of DNA hypomethylation induced by ddm1 mutation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics. 1999;151:831–838. doi: 10.1093/genetics/151.2.831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kermicle JL. Epigenetic silencing and activation of a maize r gene. In: Russo VEA, et al., editors. Epigenetic mechanisms of gene regulation. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1996. pp. 267–289. [Google Scholar]

- Kunze R, Starlinger P. The putative transposase of transposable element Ac from Zea mays L. interacts with subterminal sequences of Ac. EMBO J. 1989;8:3177–3185. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08476.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le QH, Wright S, Yu Z, Bureau T. Transposon diversity in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2000;97:7376–7381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.13.7376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X, Kaul S, Rounsley S, Shea TP, Benito MI, Town CD, Fujii CY, Mason T, Bowman CL, Barnstead M, et al. Sequence and analysis of chromosome 2 of the plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature. 1999;402:761–768. doi: 10.1038/45471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisch D, Chomet P, Freeling M. Genetic characterization of the Mutator system in maize: Behavior and regulation of Mu transposons in a minimal line. Genetics. 1995;139:1777–1796. doi: 10.1093/genetics/139.4.1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisch D, Girard L, Donlin M, Freeling M. Functional analysis of deletion derivatives of the maize transposon MuDR delineates roles for the MURA and MURB proteins. Genetics. 1999;151:331–341. doi: 10.1093/genetics/151.1.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YG, Mitsukawa N, Oosumi T, Whittier RF. Efficient isolation and mapping of Arabidopsis thaliana T-DNA insert junctions by thermal asymmetric interlaced PCR. Plant J. 1995;8:457–463. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1995.08030457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martienssen R. Epigenetic phenomena: Paramutation and gene silencing in plants. Curr Biol. 1996;6:810–813. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00601-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— Chromosomal imprinting in plants. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1998;8:240–244. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(98)80147-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martienssen R, Baron A. Coordinate suppression of mutations caused by Robertson's Mutator transposons in maize. Genetics. 1994;136:1157–1170. doi: 10.1093/genetics/136.3.1157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martienssen RA, Richards EJ. DNA methylation in eukaryotes. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1995;5:234–242. doi: 10.1016/0959-437x(95)80014-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martienssen R, Henikoff S. The House & Garden guide to chromatin remodelling. Nat Genet. 1999;22:6–7. doi: 10.1038/8708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martienssen R, Barkan A, Taylor WC, Freeling M. Somatically heritable switches in the DNA modification of Mu transposable elements monitored with a suppressible mutant in maize. Genes & Dev. 1990;4:331–343. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.3.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matzke AJ, Matzke MA. Position effects and epigenetic silencing of plant transgenes. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 1998;1:142–148. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(98)80016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer K, Schuller C, Wambutt R, Murphy G, Volckaert G, Pohl T, Dusterhoft A, Stiekema W, Entian KD, Terryn N, et al. Sequence and analysis of chromosome 4 of the plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature. 1999;402:769–777. doi: 10.1038/47134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClintock B. Chromosome organization and genic expression. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1951;16:13–47. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1951.016.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ————— The control of gene action in maize. Brookhaven Symp Biol. 1965;18:162–184. [Google Scholar]

- ————— The significance of responses of the genome to challenge. Science. 1984;226:792–801. doi: 10.1126/science.15739260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan HD, Sutherland HG, Martin DI, Whitelaw E. Epigenetic inheritance at the agouti locus in the mouse. Nat Genet. 1999;23:314–318. doi: 10.1038/15490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page RD. TreeView: An application to display phylogenetic trees on personal computers. Comput Appl Biosci. 1996;12:357–358. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/12.4.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paszkowski J, Mittelsten Scheid O. Plant genes: The genetics of epigenetics. Curr Biol. 1998;8:206–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabinowicz P, Schutz K, Dedhia N, Yordan C, Parnell L, Stein L, McCombie W, Martienssen R. Differential methylation of genes and retrotransposons allows shotgun sequencing of the maize genome. Nat Genet. 1999;23:305–308. doi: 10.1038/15479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raizada MN, Walbot V. The late developmental pattern of Mu transposon excision is conferred by a cauliflower mosaic virus 35S-driven MURA cDNA in transgenic maize. Plant Cell. 2000;12:5–21. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SanMiguel P, Gaut BS, Tikhonov A, Nakajima Y, Bennetzen JL. The paleontology of intergene retrotransposons of maize. Nat Genet. 1998;20:43–45. doi: 10.1038/1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Settles AM, Baron A, Barkan A, Martienssen RA. Duplication and suppression of chloroplast protein translocation genes in maize. Genetics. 2001;157:349–360. doi: 10.1093/genetics/157.1.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steimer A, Amedeo P, Afsar K, Fransz P, Scheid OM, Paszkowski J. Endogenous targets of transcriptional gene silencing in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2000;12:1165–1178. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.7.1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundaresan V, Freeling M. An extrachromosomal form of the Mu transposons of maize. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1987;84:4924–4928. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.14.4924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatusova TA, Madden TL. BLAST 2 Sequences, a new tool for comparing protein and nucleotide sequences. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;174:247–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor LP, Walbot V. A deletion adjacent to the maize transposable element Mu-1 accompanies loss of Adh1 expression. EMBO J. 1985;4:869–876. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03712.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vongs A, Kakutani T, Martienssen RA, Richards EJ. Arabidopsis thaliana DNA methylation mutants. Science. 1993;260:1926–1928. doi: 10.1126/science.8316832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh CP, Bestor TH. Cytosine methylation and mammalian development. Genes & Dev. 1999;13:26–34. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.1.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Z, Wright SI, Bureau TE. Mutator-like elements in Arabidopsis thaliana: Structure, diversity and evolution. Genetics. 2000;156:2019–2031. doi: 10.1093/genetics/156.4.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]