Amphiphysin is necessary for organization of the excitation–contraction coupling machinery of muscles, but not for synaptic vesicle endocytosis in Drosophila (original) (raw)

Abstract

Amphiphysins 1 and 2 are enriched in the mammalian brain and are proposed to recruit dynamin to sites of endocytosis. Shorter amphiphysin 2 splice variants are also found ubiquitously, with an enrichment in skeletal muscle. At the Drosophila larval neuromuscular junction, amphiphysin is localized postsynaptically and amphiphysin mutants have no major defects in neurotransmission; they are also viable, but flightless. Like mammalian amphiphysin 2 in muscles, Drosophila amphiphysin does not bind clathrin, but can tubulate lipids and is localized on T-tubules. Amphiphysin mutants have a novel phenotype, a severely disorganized T-tubule/sarcoplasmic reticulum system. We therefore propose that muscle amphiphysin is not involved in clathrin-mediated endocytosis, but in the structural organization of the membrane-bound compartments of the excitation–contraction coupling machinery of muscles.

Keywords: Dynamin, DLG, indirect flight muscles, T-tubules, ryanodine receptor, myopathy

Clathrin-mediated endocytosis is a process by which cells retrieve proteins from the plasma membrane into vesicles. It is also a major mechanism for retrieval of synaptic vesicle components after exocytosis. During this process, areas of membrane containing proteins to be endocytosed are folded inward to form a pit; the pit then closes up, generating a vesicle that breaks off from the membrane. Dynamin is essential for the scission of these nascent vesicles, providing the mechanical force, and considerable evidence suggests that amphiphysin is essential for the recruitment of dynamin to its site of action (Takei et al. 1999; Vallis et al. 1999).

Two amphiphysin genes (1 and 2) are found in mammals (Lichte et al. 1992; Ramjaun et al. 1997; Wigge et al. 1997a). Amphiphysin 1 is highly brain-enriched, as are the larger splice variants of amphiphysin 2. The N terminus of amphiphysin is capable of oligomerization (Wigge et al. 1997a; Ramjaun et al. 1999) and of tubulating lipids, either alone or cooperatively with dynamin (Takei et al. 1999). The central region harbors AP2- and clathrin-binding motifs (Dell Angelica et al. 1998; Owen et al. 1998; ter Haar et al. 2000), although in some amphiphysin 2 splice variants, these motifs are absent. Amphiphysins also possess a C-terminal SH3 domain whose major binding partners are the endocytic proteins dynamin and synaptojanin (David et al. 1996; McPherson et al. 1996; Ramjaun et al. 1997).

An endocytic function for amphiphysin is further suggested by the results of dominant-negative overexpression experiments. For example, expression of the central region of amphiphysin 1 blocks endocytosis (Slepnev et al. 1998, 2000). In addition, overexpression in lamprey synapses of the SH3 domain leads to the accumulation of coated pits and a reduction in neurotransmitter release in response to high-frequency stimulation (Shupliakov et al. 1997). Expression of the SH3 domain in cultured mammalian cells also impairs endocytosis, and this impairment is rescued by coexpression of dynamin (Wigge et al. 1997b).

Alternative functions for amphiphysin have also been proposed. For instance, a splice form of amphiphysin 2 that possesses a nuclear localization signal inhibits malignant cell transformation by myc (Sakamuro et al. 1996). The two yeast amphiphysin homologs, Rvs161p and Rvs167p, have many proposed functions, including actin localization (Munn et al. 1995). Amphiphysin 2 splice variants that lack the clathrin-binding region are highly expressed in muscles and are likely to be localized on T-tubules, where their role is undetermined (Butler et al. 1997).

We have studied the function of amphiphysin in Drosophila by disrupting the only gene for this protein. Surprisingly, flies lacking amphiphysin are viable and have little or no detectable defect in synaptic vesicle endocytosis. However, they are flightless and have severe structural defects in the excitation–contraction coupling machinery of muscles. This indicates a novel role for amphiphysin in muscle function.

Results

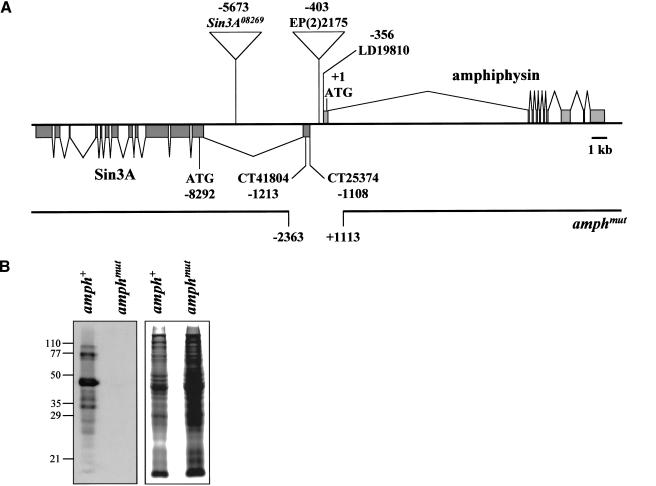

Generation of null mutations in the Drosophila amphiphysin gene

Comparison of amphiphysin cDNA and EST sequences with genomic sequence allowed us to define the amphiphysin transcription unit (Fig. 1A). The gene contains 10 exons and occupies ∼17.5 kb of DNA. A homozygous viable P insertion, EP(2)2175, lies 47 bp upstream of the amphiphysin cDNA, LD19810 (Liao et al. 2000; Razzaq et al. 2000). This insertion was mobilized to generate a number of imprecise excisions; one of these, amph26 (hereafter referred to as amphmut), had a deletion of the first exon including the beginning of the coding region, and part of the first intron of the amphiphysin gene (Fig. 1A). A precise excision that left the amphiphysin genomic region intact, amph+1 (hereafter referred to as amph+), was also recovered and used as a wild-type control in subsequent experiments. Western blots detected a number of related amphiphysin proteins in amph+ flies, perhaps generated by alternative transcripts, or by physiological or artifactual protein degradation. All of these were absent in amphmut homozygotes (Fig. 1B), and we therefore conclude that amphmut is a null allele of the amphiphysin gene.

Figure 1.

Generation of a Drosophila amphiphysin mutant. (A) Structure and mutagenesis of the amphiphysin gene. The intron/exon structure of the amph and Sin3A genes is shown, together with the positions of their start codons, two predicted transcription start sites of Sin3A, and the insertion site of _P_-element EP(2)2175. The breakpoints of the amphmut excision are shown; it also contains an insertion of sequence TTTTATCAAAATTT at the deletion site. The approximate position of the P insertion in Sin3A08269 is also shown; the locations of the lesions in the other Sin3A alleles are unknown at this level of resolution. All coordinates are given relative to the first nucleotide of the amphiphysin coding region (Razzaq et al. 2000). (B) A Western blot of amph+ and amphmut homozygous flies probed with an antibody against Drosophila amphiphysin (left panel). Numbers indicate molecular masses in kilodaltons. A Coomassie-stained duplicate gel (right panel) allows comparison of protein loading.

Unexpectedly, in light of the proposed central role for amphiphysin in endocytosis, amphmut flies were viable and fertile both when homozygous, and when transheterozygous with a deficiency Df(2R)vg-C, which deletes the amphiphysin genomic region. They also showed no obvious external defects in eye, bristle, or wing pattern that might result from the interference with endocytic mechanisms involved in wingless, EGF receptor, TGF-β/decapentaplegic, or Notch signaling (Vieira et al. 1996; Seugnet et al. 1997; Entchev et al. 2000; Dubois et al. 2001). Adult mutants were, however, flightless and generally sluggish when homozygous, or when transheterozygous with Df(2R)vg-C. EP(2)2175 homozygotes, amph+ homozygotes, and amph+/Df(2R)vg-C heterozygotes all showed no mutant phenotype.

In addition to a deletion of the 5′ end of the amph gene, amphmut also had a deletion of part of the first exon of the adjacent gene Sin3A, but left its coding region intact (Fig. 1A). We could detect no impaired function of Sin3A by amphmut. First, loss of Sin3A is homozygous lethal (Pennetta and Pauli 1998), whereas amphmut is homozygous viable. Second, crosses between amphmut and four different Sin3A mutant alleles showed complementation for the flightless and sluggish phenotypes.

The distribution of amphiphysin protein is not consistent with a role in synaptic vesicle endocytosis

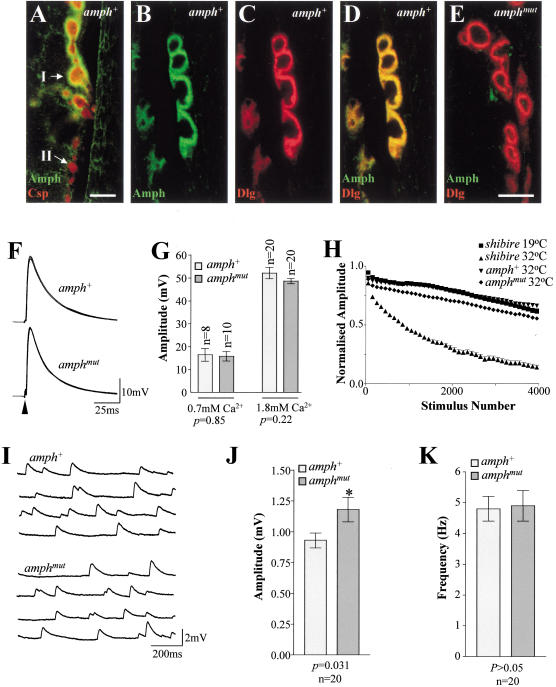

Vertebrate amphiphysins 1 and 2 are soluble proteins that are associated in vivo with synaptic vesicles (Lichte et al. 1992; Wigge et al. 1997a). Double staining for amphiphysin and either a synaptic vesicle marker (cysteine string protein, CSP; see Mastrogiacomo et al. 1994; Estes et al. 1996) or a marker that is essentially postsynaptic using optical microscopy (Discs-large, DLG; Lahey et al. 1994) showed that amphiphysin was detectable only postsynaptically at the larval neuromuscular junction (NMJ; Fig. 2A–D). Amphiphysin was found only around type I boutons, where its distribution overlapped with that of DLG, a membrane-associated guanylate kinase (MAGUK) that is responsible for clustering ion channels and cell adhesion molecules (Dimitratos et al. 1999). No amphiphysin was detected around type II boutons (Fig. 2A), which lack DLG protein postsynaptically (Lahey et al. 1994; Woods et al. 1997). Although we cannot rule out low levels of presynaptic amphiphysin, or its presence on the presynaptic plasma membrane of type I boutons (indistinguishable from the postsynaptic compartment by optical microscopy), its absence from type II boutons and from the vesicle-containing cytosolic region of type I boutons suggests that it is unlikely to be required for synaptic vesicle recycling. No amphiphysin staining was found postsynaptically at amphmut larval NMJs (Fig. 2E). However, postsynaptic structure, visualized by DLG staining, was intact in amphmut larvae, showing that amphiphysin was not required for the gross structural organization of the postsynaptic NMJ.

Figure 2.

Amphiphysin is localized postsynaptically at the Drosophila larval NMJ and is not necessary for synaptic vesicle recycling. (A) Double labeling of a homozygous amph+ NMJ on larval body wall muscle 12 for cysteine string protein (CSP, presynaptic, red) and amphiphysin (Amph, green). Only the postsynaptic compartments of the larger type I boutons (I) have detectable amphiphysin staining; the smaller type II boutons (II) do not. Labeling of homozygous amph+ type I boutons on larval body wall muscle 7 for amphiphysin (B), the mainly postsynaptic marker DLG (C), and both proteins (D). (E) Double labeling of homozygous amphmut type I boutons on larval body wall muscle 7 for DLG (red) and amphiphysin (green). Bars, A and B–E, 5 μm. (F) Five representative traces showing excitatory junction potentials (EJPs) evoked by 1 Hz stimulation, recorded from muscle 6 in third instar larvae from wild-type (amph+1 /Df(2R)vg-C; labeled amph+) and mutant (amph26/Df(2R)vg-C; labeled amphmut) lines. Loss of amphiphysin has no effect on either the time course (F) or the amplitude (G) of the responses observed. (H) High frequency stimulation (20 Hz) of the motoneurone led only to a slow rate of rundown in the evoked response recorded from amphmut homozygotes and amph+ homozygotes at 32°C,and from shibirets1 larvae at the permissive temperature (19°C). In contrast, there was a very rapid and extensive rundown in the EJP amplitude recorded from shibirets1 larvae at the restrictive temperature (32°C). (I) Four representative traces of recordings of spontaneous neurotransmitter release (mEJPs) are shown from wild-type and mutant animals. There was a small (but significant; P = 0.03) increase in amplitude of the mEJPs recorded from mutant muscles (J), but the frequency of these events was not altered (K).

Amphiphysin mutants have no major defects in synaptic transmission at the NMJ

Mutations affecting endocytic proteins have pronounced effects on synaptic transmission in flies. For example, mutations in both lap (AP180) and stoned show reduced excitatory junction potential (EJP) amplitudes, increased variance in EJP size, and increased numbers of failures (Stimson et al. 1998; Zhang et al. 1998; Fergestad et al. 1999). In contrast, EJP amplitude was unaffected in amphmut larvae (Fig. 2F,G), and failures in synaptic transmission were never observed. High frequency stimulation results in a progressive rundown in EJPs in stoned and shibire mutants, owing to failure to replenish the vesicle pool by endocytosis (Fergestad et al. 1999; Li and Schwarz 1999; Delgado et al. 2000; also see Fig. 2H). In all lines tested, there is an apparent initial rapid decrease in the EJP amplitude during high frequency stimulation, caused by a depletion of the synaptic vesicle pool during the first few stimulations (Delgado et al. 2000), and by a failure of the muscle to return to its resting membrane potential during the interpulse period of 50 msec. However, shibirets1 (at the permissive temperature), amph+, and amphmut larvae showed only a continuing slow decrease in EJP amplitude, in contrast to the much faster and more pronounced decrease observed in shibirets mutants at their restrictive temperature (Fig. 2H). Compared with amph+ and shibirets (at the permissive temperature), amphmut larvae had a larger initial drop in EJP amplitude, but the continued decline phase appeared similar in all these genotypes. Although we cannot rule out a mild defect in vesicle recycling, the subtle electrophysiological changes seen in amphmut larvae could also be explained by small changes in postsynaptic excitability (e.g., receptor or channel numbers or differences in desensitization). Nevertheless, because amphmut larvae clearly show a much milder phenotype than that of shibirets larvae at their restrictive temperature, amphiphysin cannot be an absolute requirement for synaptic vesicle recycling at the NMJ.

The amph mutants also showed a small increase in amplitude of miniature excitatory junction potentials (mEJPs; Fig. 2I,J), but no significant effect on mEJP frequency (Fig. 2K). Given the localization of amphiphysin at the postsynaptic NMJ of wild-type larvae, the increased mEJP amplitude in the mutant may reflect subtle changes in the postsynaptic physiology of the NMJ.

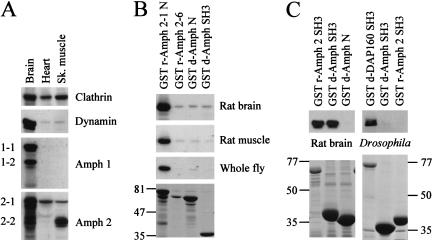

Protein interactions of Drosophila amphiphysin and vertebrate amphiphysin 2

In Drosophila, amphiphysin exhibits strong postsynaptic expression, whereas in mammalian tissue, it is highly enriched in the brain (Fig. 3A) and found presynaptically (Lichte et al. 1992; Wigge et al. 1997a). However, one or more splice forms of mammalian amphiphysin 2 that lack a consensus clathrin-binding motif are also highly expressed in skeletal muscle (Fig. 3A; Butler et al. 1997; Wechsler-Reya et al. 1997; see Materials and Methods) and are similar to the amphiphysin splice form (Amph 2-6) cloned from kidney (Wigge et al. 1997a).

Figure 3.

Rat tissue distribution and protein-binding partners for amphiphysin. (A) Western blots showing protein distribution of clathrin, dynamin, and amphiphysins 1 and 2 in brain, heart, and skeletal muscle tissue from rat. Splice forms of amphiphysin are indicated on the left. Amphiphysins 1 and 2 were highly enriched in brain, although amphiphysin 2 was also detected in other tissues, with one or more lower molecular weight species enriched in muscle. Antibodies used were Clathrin (Sigma monoclonal), Dynamin I/II (Transduction monoclonal), Amphiphysin 1 (Transduction monoclonal), and Amphiphysin 2 (Ra 1.2 polyclonal). (B) Clathrin binding to amphiphysin. GST constructs of amphiphysin were used in pull-down experiments from rat brain and muscle extracts, and from whole Drosophila extract. The N terminus of rat amphiphysin 2 (GST r-Amph 2-1 N) interacts with clathrin in rat brain, rat skeletal muscle, and Drosophila extracts. Rat amphiphysin 2-6 (GST r-Amph 2-6) and the N terminus of Drosophila amphiphysin (GST d-Amph N), both of which lack consensus sequences for clathrin binding, were also probed. The residual band detected in rat brain and muscle tissues is nonspecific as it is also seen with the Drosophila amphiphysin SH3 domain (GST d-Amph SH3; negative control). Blots (top three panels) were probed with the X22 monoclonal antibody, which detects both the muscle and brain forms of clathrin (Liu et al. 2001). A Coomassie-stained duplicate gel (bottom panel) shows each GST fusion protein after binding to whole fly extract; identical aliquots of fusion proteins were used for binding to rat extracts. The major band in each lane is the GST fusion protein, and the other bands are a mixture of its degradation products and of its binding partners. Numbers indicate molecular masses in kilodaltons. (C) Dynamin binding to SH3 domains of amphiphysins. Rat brain dynamin (detected with a dynamin I monoclonal antibody, top left panel) bound to the SH3 domains from both rat amphiphysin 2 (GST r-Amph2) and Drosophila amphiphysin (GST d-Amph SH3). GST d-Amph N was used as a negative control for binding. In Drosophila extract, the interaction of the SH3 domains with dynamin (detected with an antibody against Drosophila dynamin, top right panel) was barely visible in comparison with the DAP160 SH3a,b,c,d domain (GST d-DAP160 SH3, positive control) which has previously been shown to interact strongly with Drosophila dynamin (Roos and Kelly 1998). Upon higher exposures, weak dynamin binding to both GST d-Amph and GST r-Amph 2 SH3 domains was detectable. Coomassie-stained duplicate gels (bottom panels) show each GST fusion protein after binding to extracts. The major band in each lane is the GST fusion protein, and the other bands are a mixture of its degradation products and of its binding partners. Numbers indicate molecular masses in kilodaltons.

Using pull-down assays, we tested the binding of glutathione-S-transferase (GST) fusions of the N- and C-terminal domains of Drosophila amphiphysin and rat amphiphysin 2-1 (Amph 2-1), as well as that of whole rat Amph 2-6, to rat brain, rat muscle, and whole Drosophila protein extracts (Fig. 3B,C). The N terminus of the brain-enriched form, Amph 2-1, has a clathrin-binding consensus sequence and binds clathrin (Fig. 3B). Amph 2-6 and Drosophila amphiphysin lack this sequence, failed to bind clathrin (Fig. 3B), and are therefore unlikely to participate in clathrin-mediated endocytosis. The SH3 domains of rat amphiphysin 2 and Drosophila amphiphysin bound to rat brain dynamin, but not to Drosophila dynamin (Fig. 3C). The latter is probably a consequence of the lack of conservation of the consensus amphiphysin SH3-binding motif (PxRPxR; see Owen et al. 1998) in Drosophila dynamin. In contrast, the SH3 domains of DAP160 (Roos and Kelly 1998), the Drosophila intersectin homolog, bound strongly to Drosophila dynamin (Fig. 3C). The failure of Drosophila amphiphysin to interact significantly with Drosophila dynamin also argues against an endocytic role in Drosophila.

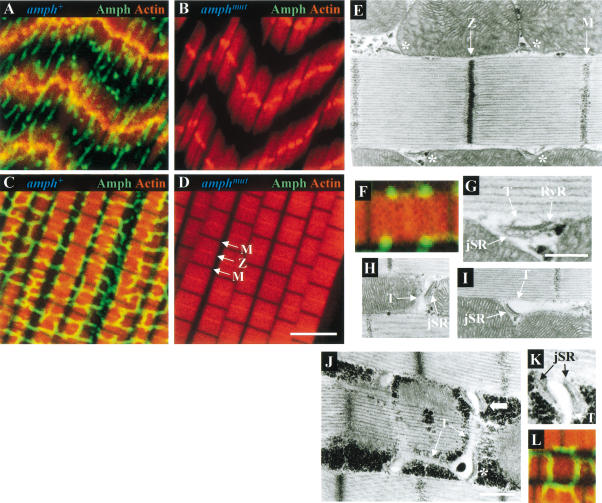

Amphiphysin is localized on muscle T-tubules

Amphiphysin expression was not limited to the neuromuscular junction and was also found throughout larval body wall and adult thoracic muscles, localized on a reticular network (Fig. 4A,C). A similar network in larval body wall muscles has previously been shown using antibodies against DLG (Thomas et al. 2000).

Figure 4.

Amphiphysin is found on muscle T-tubules. Confocal sections of amphiphysin (Amph, green) and actin (red) double labeling in larval body wall muscles (A,B) and adult IFMs (C,D), from amph+ (A,C) and amphmut (B,D) homozygotes. In panel D, the locations of the M and Z lines are indicated. (E,G_–_K) Electron micrographs of amph+ IFM longitudinal sections. (E) Longitudinal section through the center of a myofibril with dyads (asterisks) associated along each side of the myofibril at a region midway between the M and Z lines. (F) Amphiphysin (green) and actin (red) double labeling of a sarcomere similar to that of panel E. (G) Higher magnification of a dyad from panel E showing the electron-lucent T-tubule and electron-dense jSR compartments, and the RyR-containing density on the face of the jSR cisterna. Longitudinal sections through the peripheral surface of a myofibril showing the T-tubular compartments of dyads extending as tranverse (H) or longitudinal (I) projections away from the adjoining jSR. (J) Longitudinal section grazing along the peripheral surface of a myofibril showing both transverse and longitudinal T-tubular projections extending from a dyad (asterisk) and a triad (broad arrow). (K) Higher magnification of the triad in panel G showing the translucent T-tubule compartment flanked on either side by two jSR compartments. (L) Amphiphysin (green) and actin (red) double labeling of a section along the top of a sarcomere, similar to that of panel J. Bar in D (for panels A_–_D), 5 μm; bar in G (for panels G and K), 250 nm; bar in J (for panels E, H_–_J), 500 nm. All IFMs shown are dorsolongitudinal IFMs.

Amphiphysin distribution was analyzed in most detail in indirect flight muscles (IFMs; Fig. 4C), highly specialized muscles that can contract at up to 300 Hz (Crossley 1978). In IFMs, amphiphysin is found on an extensive network of transverse and longitudinal projections that ramify around and between myofibrils. These transverse projections overlie sarcomeres periodically at positions midway between the M and Z lines (see Fig. 4D for positions of the latter), at which myosin and actin filaments, respectively, are anchored. The positions of transverse projections coincide with the locations of junctions formed by close apposition of the T-system to the junctional sarcoplasmic reticulum (jSR). These T–jSR junctions play a vital role in excitation–contraction coupling, in which depolarization of the sarcolemma activates a voltage sensor between the T-tubule and the underlying ryanodine receptors (RyRs) on the jSR surface, thus leading to calcium release from the jSR and to muscle contraction.

Ultrastructural studies of IFMs of the Dipteran Phormia regina have established that they possess mainly dyadic T–jSR junctions (Smith 1961). Consistent with the observations of Shafiq (1964), we found that Drosophila IFMs also have dyadic junctions; these were generally localized alongside the sarcomere, midway between the M and Z lines (Fig. 4E). As in Phormia, the jSR component of the dyad is electron-dense, and the T-tubule electron-lucent (Fig. 4G; Block et al. 1988). In longitudinal sections along the peripheral surface of a myofibril, the lumina of the T-system were frequently seen to extend from dyads as transverse and longitudinal tubular processes that coursed between individual myofibrils and mitochondria (Fig. 4H,I). Classic triadic T–SR junctions consisting of two jSR cisternae flanking a single T-tubule were also seen occasionally (Fig. 4J,K). Again in agreement with previous ultrastructural observations in Phormia (Smith 1961; Smith and Sacktor 1970), the only compartments seen to extend into longitudinal and transverse projections belonged to the T-system (Fig. 4J). In contrast, sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) was only found as jSR at dyadic junctions. A network of free SR, which should be visible as an extensive, fenestrated tubular network extending longitudinally along myofibrils, was either very sparse or absent from these muscles, a finding again consistent with previous observations (Smith 1961; Shafiq 1964; Smith and Sacktor 1970; Crossley 1978). We therefore conclude that the reticular amphiphysin staining in IFMs seen using immunofluoresence is the extensive T-system observed at the ultrastructural level. This localization is consistent with the reported presence of vertebrate amphiphysin 2 on the surface of skeletal muscle T-tubules (Butler et al. 1997).

Excitation–contraction coupling machinery of amph mutants is severely disorganized

The flightless phenotype of amph mutants, and localization of amphiphysin at T-tubules, suggested a defect in muscle structure or function. Muscles of amphmut homozygotes had no detectable amphiphysin (Fig. 4B,D). Despite this, mutant IFM structure was similar to that of wild type, although larval body wall muscles did display slightly looser packing of myofibrils.

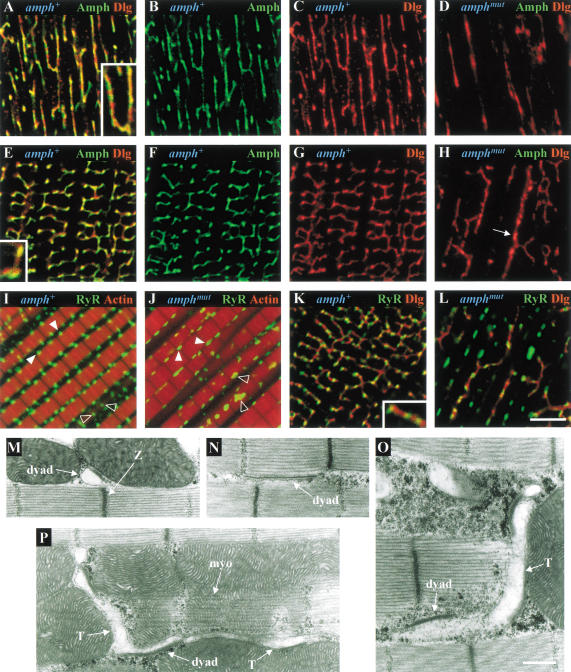

In light of the similarity of the DLG staining of larval body wall muscles (Thomas et al. 2000) to that of amphiphysin (Fig. 4A), we compared the localization of both proteins in these muscles and in IFMs. There was substantial, but incomplete, overlap of the two proteins within the T-system (Fig. 5A–C,E–G), suggesting that DLG is also localized on T-tubules. Double labeling with antibodies to RyR and DLG (Fig. 5K) showed that the DLG-containing T-tubular network ran between, but did not colocalize with, RyR-containing jSR compartments that appeared as regular puncta alongside myofibrils, approximately midway between the M and Z lines (Fig. 5I,K).

Figure 5.

Organization of the excitation–contraction coupling machinery of muscles is disrupted in amphiphysin mutants. Confocal sections showing amphiphysin (Amph, green) and Discs-large (DLG, red) labeling in larval body wall muscles (A_–_D) and adult IFMs (E_–_H) from amph+ (A_–_C,E_–_G) and amphmut (D,H) homozygotes. Arrow in panel H indicates a longitudinal mutant T-tubule with increased diameter. Double staining of homozygous amph+ (I) and amphmut (J) IFMs for Ryanodine receptor (RyR, green) and actin (red). Here, closed arrowheads indicate dyads located in longitudinal sections through the center of a myofibril, and open arrowheads indicate dyads situated in longitudinal sections through the peripheral surface of myofibrils. Double staining of homozygous amph+ (K) and amphmut (L) IFMs for RyR (green) and DLG (red). Bar in L (panels A_–_L), 5 μm. Insets in panels A, E, and K are magnified further by a factor of 1.8. (M_–_P) Electron micrographs of longitudinal sections through homozygous amphmut IFMs. Longitudinal sections through the center of a myofibril showing (M) a dyad mislocalized to the Z band, and (N) an elongated dyad extending half the length of the sarcomere, identified by the RyR-containing density on the surface of the jSR. Longitudinal sections through the peripheral surface of a myofibril showing elongated dyads extending into (O) a transverse or (P) transverse and longitudinal T-tubule projections that have greater than normal diameters. The myofibril (myo) is highlighted in panel P. Bar in O (for panels M_–_P), 500 nm. All IFMs shown are dorsolongitudinal IFMs.

In amphmut muscles, DLG staining showed that loss of amphiphysin resulted in severe disorganization and reduction of the T-system (Fig. 5D,H,L). In amphmut IFMs, many transverse elements of the T-system were lost, and the remainder were predominantly longitudinal, and sometimes broader (Fig. 5H). Dyad junctions (visualized with antibody against RyR) were still apparent, but distributed irregularly, and occupied only 42% of the cell volume fraction they occupied in wild-type IFMs. They were often larger than in wild type, sometimes extending over half the length of a sarcomere (Fig. 5J,L). Only a sparse T-system was seen between expanded and mislocalized jSR compartments (Fig. 5L).

Electron microscopy of amphmut IFMs broadly supported the conclusions drawn from confocal analysis. Thin sections of IFMs confirmed that the gross structure of mutant muscles was equivalent to wild type. Although dyads were still observed, they were no longer regularly distributed along the length of the sarcomere (Fig. 5M). The increased size of dyads seen using RyR staining (Fig. 5J,L) was corroborated by the elongated T–jSR dyads often seen in thin sections (Fig. 5N). In agreement with the confocal observations, mutant T-tubules often had larger diameters (cf. Fig. 4H,I,J with Fig. 5O,P). The reduction and mislocalization of the T/SR components suggests that amphmut flightlessness may be a consequence of a defect in excitation–contraction coupling.

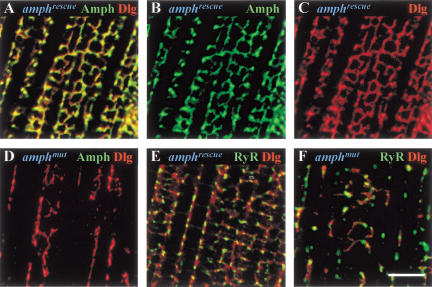

Several lines of evidence indicate that the T-tubule defect is caused by loss of amphiphysin. First, the phenotype of transheterozygotes of amphmut over the deficiency Df(2R)vg-C, assessed by actin and RyR staining of IFMs, was identical to that of amphmut homozygotes (data not shown). Second, RyR distribution in _amphmut/Sin3A_− IFMs was indistinguishable from wild type for all four Sin3A alleles tested (data not shown), showing that the phenotypes observed in muscles were not caused by impairment of Sin3A function. Third, we achieved substantial rescue of the amphmut T-tubule phenotype by driving expression of the amphiphysin cDNA, LD19810, under control of a heat-shock-inducible GAL4 gene. Here we refer to amphmut individuals that can express this cDNA as amphrescue individuals (for details of genotypes and heat shock induction, see Materials and Methods). In contrast to amphmut flies, which were flightless and possessed a disrupted T–SR system (Fig. 6D,F), almost all amphrescue individuals could fly, and they exhibited varying degrees of recovery of the T-system (Fig. 6A–C,E). All showed amphiphysin staining in a reticular pattern around individual myofibrils, which colocalized mostly with that of DLG. Although some flies had almost complete rescue of the T–SR defects (Fig. 6), many individuals had only partial rescue, in which the degree of amphiphysin branching and its ordered spacing midway between the M and Z lines was highly variable (data not shown). Interestingly, even when rescue of T-system morphology was only partial, most individuals could still fly, suggesting that the precisely ordered spacing of the T-system is not absolutely essential for flight.

Figure 6.

Expression of an amphiphysin cDNA rescues disruption of the T–SR system in amphiphysin mutants. Confocal sections of amphiphysin (Amph, green) and Discs-large (DLG, red) double-labeling (A_–_D), and of Ryanodine-receptor (RyR, green) and Discs-large (DLG, red) double-labeling (E,F), in IFMs of amphmut flies that express cDNA LD19810 under control of an hs-GAL4 construct (amphrescue, A_–_C,E) and amphmut control flies (D,F) that do not express this cDNA (for details of genotypes, see Materials and Methods). Bar, 5 μm. All individuals were raised at 25°C and subjected to a daily heat shock of 37°C for 30 min throughout development.

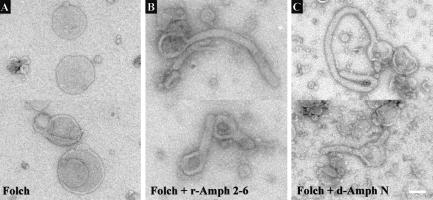

Tubulation abilities of Drosophila amphiphysin and rat amphiphysin 2

As the N terminus of rat amphiphysin 1 has the ability to tubulate lipids in vitro (Takei et al. 1999), we tested whether rat Amph 2-6 and Drosophila amphiphysin also had this ability. Both full-length Amph 2-6 and the Drosophila amphiphysin N-terminal domain readily promoted the formation of tubular projections from the surface of liposomes within the time necessary for their preparation for electron microscopy (Fig. 7). The amphiphysin protein forms the scaffold for these lipid projections. The diameters of the T-tubules in IFM electron micrographs (Fig. 4H–J) are, on average, wider than the projections generated in vitro from Folch lipids (Fig. 7B,C). This difference may be a consequence of the diameter in vivo being governed by different lipid contents, as well as by additional proteins present in T-tubule projections, such as DLG. In conclusion, both rat Amph 2-6 and Drosophila amphiphysin have the potential to initiate tubule extensions of lipid membranes similar to those seen within the reticular T-tubule network of muscles.

Figure 7.

Tubulation of liposomes by rat-Amph 2-6 and a Drosophila amphiphysin N-terminal domain. Folch liposomes show tubule protrusions in the presence of amphiphysin proteins. Undecorated Folch liposomes (A) were partially tubulated by addition of either (B) full-length vertebrate Amph 2-6 or (C) an N-terminal Drosophila amphiphysin domain (d-Amph N). Tubule protrusions formed by full-length vertebrate Amph 2-6 had wider apparent diameters than those of d-Amph N owing to the use of full-length Amph 2-6 protein, in contrast to just the N-terminal domain of Drosophila amphiphysin. Bar, 100 nm.

Discussion

Drosophila amphiphysin has no essential role in synaptic vesicle endocytosis

Taken together, our results suggest that amphiphysin has no essential role in clathrin-mediated endocytosis in Drosophila. First, Drosophila amphiphysin lacks motifs for binding to clathrin, fails to bind either vertebrate or Drosophila clathrin, and does not interact strongly with Drosophila dynamin. Second, at the larval NMJ, the protein is not detected on or around synaptic vesicles, and amph mutants have little if any discernible defect in synaptic transmission even during prolonged stimulation, suggesting that synaptic vesicle recycling is largely if not entirely intact. Third, amph mutants were viable and fertile, suggesting no gross impairment of endocytosis in nonneuronal cells. The lack of endocytic mutant phenotypes is unlikely to be owing to gene redundancy as only one amphiphysin gene is known in the Drosophila genome.

In contrast to Drosophila, vertebrate amphiphysin is localized on or around synaptic vesicles and binds to multiple endocytic proteins, and dominant-negative forms produce severe endocytic phenotypes. These results provide evidence that vertebrate amphiphysin plays an important role in endocytosis, cooperating with dynamin in the vesicle scission step. Our results do not contradict an endocytic function for vertebrate amphiphysin, but rather suggest that this function is less highly conserved than that of dynamin. In Drosophila nerve terminals, alternative proteins like Dap160, which binds Drosophila dynamin and other endocytic proteins, could fulfill functions such as dynamin recruitment that are proposed to be mediated by amphiphysin in vertebrates.

Mutations affecting the yeast amphiphysin homologs Rvs161p and Rvs167p cause defects in both endocytosis and the actin cytoskeleton (Munn et al. 1995). However, interpretation of the role of these gene products in endocytosis is complicated first by their effects on the actin cytoskeleton, as actin mutations also have endocytic defects (Munn et al. 1995), and second by the fact that clathrin and dynamin have not been reported as binding partners of Rvs161p or Rvs167p (Bon et al. 2000). Alternatively, lipid tubulation properties of the N-terminal domain of amphiphysin might represent a more ancient function of amphiphysin than its interactions with clathrin and dynamin, as this domain is conserved in yeast, Caenorhabditis, Drosophila, and mammalian amphiphysins. This function may have been adapted to both endocytic and nonendocytic roles. Indeed, amphiphysin may also have nonendocytic roles in vertebrates; the properties of Drosophila amphiphysin are similar to those of a muscle-specific splice variant of vertebrate amphiphysin 2, which also lacks a clathrin-binding site and is probably localized on T-tubules (Butler et al. 1997).

Role of amphiphysin in T-tubule organization

Comparison of the reticular localization of amphiphysin seen using confocal microscopy, with electron microscopy of the T–SR system, suggests that Drosophila amphiphysin is localized on muscle T-tubules. As vertebrate amphiphysin 2 is also found on muscle T-tubules, this suggests a conserved function for amphiphysin on these invaginations of the plasma membrane. Indeed, in flies that lack amphiphysin, T–SR junctions and T-tubule projections were greatly reduced in number and generally mislocalized, and remaining T–SR junctions were often larger than normal. Therefore, amphiphysin is essential for organization and normal morphology of the T-system.

We can envisage a number of ways in which amphiphysin might achieve this. First, the N-terminal portion of amphiphysin can tubulate lipids, and such an activity might contribute to T-tubule formation or stabilization. Although some T-tubules can still form even in the absence of amphiphysin, the reduction in transverse elements of the T-system means that amphiphysin might play a role in tubule branching, either alone or in cooperation with other proteins. Second, amphiphysin might have a cytoskeletal role in anchoring transverse T-tubules close to the myofibril, approximately midway between the Z-line and the M-line. The yeast amphiphysin homologs interact with a number of components of the actin cytoskeleton (Bon et al. 2000), and similar interactions of amphiphysin could account for both the regular positioning of the transverse elements of the T-system in wild-type flies and the slightly looser arrangement of myofibrils in larval body wall muscles in the mutant. Third, the altered organization of T-tubules and T–SR junctions suggests that amphiphysin plays a role in organizing the protein components of T-tubules. Vertebrate T-tubules contain several cell adhesion and associated cytoskeletal proteins (Tuvia et al. 1999) and have subdomains that are defined by the presence of different membrane proteins (Scriven et al. 2000). Surprisingly, we also detected DLG protein on T-tubules (Fig. 5) in domains that partially overlap with those of amphiphysin expression. DLG and its vertebrate homologs, such as PSD-95, play an important role in localizing channels and cell adhesion proteins at synapses (Dimitratos et al. 1999), and it could play an analogous role in T-tubules. These models of amphiphysin function are not mutually exclusive. Testing them will involve addressing questions such as the interactions that localize T-tubules to the middle of the M–Z interval, the binding partners of the SH3 domain of Drosophila amphiphysin if they do not include dynamin, and the contribution of other proteins to morphology of the T-system. One protein of potential relevance might have been caveolin, as the initial stages of vertebrate T-tubule formation may be analogous to caveola formation, and caveolin 3 is found on vertebrate T-tubules (Carozzi et al. 2000). However, we can detect no caveolin homolog in the Drosophila genome.

Implications for muscle function and pathology

A predicted consequence of disrupted T-system would be altered spatial and temporal dynamics of calcium flux in the cytoplasm. Elevations in calcium concentration following muscle depolarization are first seen at discrete regions before the calcium gradients dissipate (Monck et al. 1994), and alterations in calcium dynamics might reduce the extent, speed, and synchronization of muscle contraction. Although this would not entirely block muscle contraction, it would probably interfere with the rapid coordinated cycles of contraction and relaxation of IFMs.

Given the localization of vertebrate amphiphysin 2 on T-tubules (Butler et al. 1997), mutations in human amphiphysin 2 might be implicated in myopathies that are associated with defects in excitation–contraction coupling. Experimentally induced congestive heart failure can lead to a disorganization and reduction in number of T-tubules in cardiac myocytes (He et al. 2001). Furthermore, the human conditions of malignant hyperthermia and central core disease have been linked to mutations affecting other components of excitation–contraction coupling, RyR or the L-type calcium channel (MacLennan 2000). It is possible that myopathies that map to other loci might involve amphiphysin. The phenotypes of mice deficient in amphiphysin 2 should help clarify this question.

In conclusion, our results shed new light on the role of amphiphysin within a broader physiological and phylogenetic context. The use of Drosophila as a model organism offers not only the advantage of powerful genetics and functional analysis, but allows novel nonendocytic roles of amphiphysin to be studied in a situation where they are not masked by its endocytic functions.

Materials and methods

Genetics

Excisions of EP(2)2175 were generated (O'Kane 1998) by crossing to a stock carrying the transposase insertion P{ry+, Δ2-3}99B (Robertson et al. 1988). Progeny of individuals that had lost the w+ marker were used to make stocks that were screened for excisions by PCR and sequencing. The reverted excision site of amph+1 homozygotes was verified using primers 5′-GCGCGC TGCGTCTGG-3′ (−1232 to −1218) and 5′-CCAAACAATATC GGCCCCACAC-3′ (−182 to −203). The amph26 excision in homozygous flies was characterized using primers 5′-CACCAAA GGGTACATTGAGCTGCC-3′ (−2510 to −2486) and 5′-GCAT CCGCAAGATGCTGTGTG-3′ (1470 to 1450). All primers are numbered relative to the first nucleotide of the amph coding sequence. For complementation tests, amph26 homozygotes were crossed to Sin3A_−/CyO_ mutant stocks, and non-curly progeny were assessed for amph26 mutant phenotypes. The four Sin3A mutant alleles used were Sin3Ae64, Sin3Axe374 (Neufeld et al. 1998), Sin3Ak05415 (Pennetta and Pauli 1998), and Sin3Ak08269 (Liao et al. 2000), the latter two each harboring a _P_-insertion in the first intron of Sin3A. Transheterozygous amph+ and amphmut larvae were generated by crossing amph+1 and amph26 homozygotes, respectively, to Df(2R)vg-C/CyO, Ubi-mycGFP flies (flies carrying plasmid pUGH constructed by Jan Qiu [Brandeis University, Waltham, MA], mobilized onto CyO by Paolo d'Avino [University of Cambridge, UK]) and selecting the non-GFP-expressing larval progeny.

For rescue of mutant phenotypes, expression of cDNA LD19810 (Razzaq et al. 2000), which had been cloned into the GAL4-dependent expression vector pUAST (Brand and Perrimon 1993) and inserted on chromosome 3, was driven by a heat-shock-inducible GAL4 insertion, hs-GAL4 (a kind gift of T.L. Schwarz, Harvard University, Boston, MA). Flies heterozygous for amphmut and carrying either LD19810 or hs-GAL4 over a third chromosome balancer were mated to each other, to generate homozygous amphmut progeny that carried either both LD19810 and hs-GAL4 (amphrescue individuals, which could express amphiphysin), or only one of these constructs (effectively amphmut). The latter were used as nonexpressing controls in the rescue experiments. All progeny were raised at 25°C throughout development and given daily heat shocks for 30 min at 37°C. Rescue and control flies were then assessed for flight ability (by observing whether they flew away when walking in an open space) and T-system integrity.

Confocal markers and antibodies

A rabbit antibody, Ra29, raised against the Drosophila amphiphysin SH3 domain (residues 525–602), was used for all experiments, except those in Figure 5A–D, at 1:500 dilution. Rabbit anti-Drosophila amphiphysin antibody 9906 (raised against residues 523–602 of the Drosophila amphiphysin SH3 domain and affinity-purified) was used at 1:250 for Figure 5A–D, and gave the same results as Ra29 in all immunomicroscopy. Monoclonal mouse anti-CSP (Reichmuth et al. 1995) was used at 1:250, polyclonal guinea pig anti-DLG (Woods et al. 1997) at 1:500, anti-RyR (Seok et al. 1992) at 1:20, and Texas-Red phalloidin (Molecular Probes) at 1:150 dilution.

Immunocytochemistry

Third instar larval dissections (Atwood et al. 1993) and thoracic dissections of IFMs (Peckham et al. 1990) were performed as described. Tissues were dissected directly in fixative (4% formaldehyde in PBS: 10 mM phosphate buffer, 2.7 mM KCl, 137 mM NaCl at pH 7.4) for 20 min. All subsequent washes and incubations were performed in blocking buffer (0.3% Triton X-100, 0.1% bovine serum albumin, 2% donkey serum in PBS). Samples were blocked in four changes of buffer for 30 min each, then incubated at 4°C overnight in primary antibody. Samples were washed, incubated in donkey secondary antibody (Jackson laboratories, 1:250) for 60 min, washed, mounted in Vectashield (Vector Laboratories), and visualized using a Bio-Rad Radiance confocal microscope. To estimate the volume fraction of muscle cells occupied by RyR immunoreactivity, a quadratic lattice was overlaid on 10 randomly selected fields of view from 5 wild-type and 5 mutant IFMs, and the number of points landing on immunoreactive elements was divided by the total number of points on the IFM.

Ultrastructural analysis

Adult IFMs were prepared essentially as in O'Donnell and Bernstein (1988), with modifications taken from Forbes et al. (1977). Adults aged 3–5 d were dissected in buffer (5 mM HEPES, 128 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 4 mM MgCl2, 36 mM sucrose at pH 7.2), and the half-thoraces were immediately transferred into fixative (0.1 M sodium phosphate, 3% paraformaldehyde, 2% glutaraldehyde, 2 mM sodium EGTA, 0.1 M sucrose at pH 7.2) and incubated at 4°C overnight on a blood mixer. After 60 min in wash buffer (0.1 M sodium cacodylate, 0.1 M sucrose at pH 7.2), samples were postfixed at room temperature for 60 min in 1% osmium tetroxide in wash buffer supplemented with 0.8% potassium ferrocyanide. Following a further 60 min in wash buffer, samples were dehydrated through a graded acetone series and then embedded in Spurr resin.

Electrophysiology

Wandering third instar larvae were dissected in HL3 (Stewart et al. 1994) containing 1.8 mM CaCl2 unless otherwise stated. Nerves innervating the body muscle walls were cut near the ventral ganglion and stimulated using a suction electrode and isolated pulse stimulator Digitimer DS2A (constant current modification), with a current double that needed to initiate a compound response. All recordings were made intracellularly in muscle cell 6, abdominal segment 2 or 3, at ambient room temperature (∼26°C), using microelectrodes filled with 3 M KCl that had tip resistances of 20–30 MΩ. In 1.8 mM extracellular Ca2+, resting membrane potentials were −71.4 ± 1.6 mV (n = 20) and −73.5 ± 1.4 mV (n = 20; P > 0.05) for amph+ and amphmut larvae, respectively. Data were acquired using an Axopatch 200B amplifier, filtered at 1 kHz, and digitized at 10 kHz before being stored and analyzed with locally written software (Labview 5.0, National Instruments) and acquired with an AT-MIO-16X DAQ board (National Instruments), or using pClamp8.02 and a Digidata 1320A DAQ board (Axon). Histograms were constructed by averaging 50 separate events stimulated at 1 Hz from an individual muscle cell and then calculating the mean response from at least 8 larvae per line. In the rundown experiment, temperatures were regulated using a TC-10 temperature controlled stage (Dagan); the permissive temperature used for shibirets1 recordings was 19°C, and the restrictive temperature was 32°C. To facilitate comparisons of data between different cells in the rundown experiment, the first 10 events in a train were averaged and all events were normalized to this value. A mean of normalized evoked responses was made for every 100 stimulations applied to each larva. Spontaneous release events were recorded for 120 sec prior to any electrical stimulation, the first 150 individual nonoverlapping events were measured for each cell, and means from 20 individuals were then averaged to generate the histograms. Mini frequencies were calculated for the full recording period.

Protein expression and binding studies

Domains of amphiphysin were expressed as N- or C-terminal GST fusions, expressed in BL-21(DE3) bacteria, and purified on glutathione agarose beads (Sigma). The constructs used were rat-Amph 2-1 N (residues 1–422), rat-Amph 2-6, _Drosophila_-Amph N (residues 1–357), _Drosophila_-Amph SH3 (residues 525–602), rat-Amph 2 SH3 (residues 494–588 of Amph 2-1), and _Drosophila_-DAP160 SH3a,b,c,d (Roos and Kelly 1998). The rat amphiphysin splice variants are described in Wigge et al. (1997a). The cloned rat-Amph 2–6 is either identical, or very similar, to the splice form(s) of Amph 2 expressed in muscle. This was determined by comparing the mobilities of the expressed and endogenous proteins on PAGE, and also by sequencing of PCR products from a muscle cDNA library. The muscle form was missing amino acids 336–483, which contain the clathrin-binding motif. Amphiphysin constructs (20 μg of each) were used for affinity interaction experiments (Owen et al. 1998) with tissue extracts (at ∼1 mg/mL) prepared by homogenization in PBS supplemented with 0.1% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA, and 1:1000 dilution of protease inhibitor cocktail Set III (Calbiochem). Following SDS-PAGE and transfer onto nitrocellulose, binding partners were assessed by immunoblotting.

Liposome preparation

Liposomes were prepared as described in Stowell et al. (1999). Folch fraction I lipids (Sigma) were suspended at 1 mg/mL in 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4) and extruded through a 0.1-μm filter. Amphiphysin was added to ∼0.1 mg/mL, and lipid binding was terminated after 5 min by applying 10 μL to a carbon-coated 350-mesh grid, which was then blotted and stained with 0.5% uranyl acetate (Stowell et al. 1999).

Acknowledgments

We thank Janet Powell of the University of Cambridge Multi-Imaging Centre for EM preparations, and Chris Huang for helpful insights into muscle structure. We also thank Frances Brodsky, Erich Buchner, Gerhard Meissner, Jack Roos, and Dan Woods for antibodies; Reg Kelly and Jack Roos for the GST-Dap160 construct; and Daniel Pauli, Paolo d'Avino, the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center, and the Berkeley Drosophila Genome Project for fly stocks. We are grateful to Chris Doe for support of A. Zelhof's work, and to Kathryn Lilley for facilitating completion of this study. The Cambridge Multi-Imaging Center was established with Wellcome Trust grant 039398/Z/93/Z. I.M.R. is an MRC Career Development Award Fellow. This work was supported by Wellcome Trust grant 052625 to N.J.G., A.P.J., and C.J.O'K.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

E-MAIL c.okane@gen.cam.ac.uk; FAX 44-1223-333992.

Article and publication are at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.207801.

References

- Atwood H, Govind C, Wu C. Differential ultrastructure of synaptic terminals on ventral longitudinal abdominal muscles in Drosophila larvae. J Neurobiol. 1993;24:1008–1024. doi: 10.1002/neu.480240803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block B, Leung A, Campbell K, Franzini-Armstrong C. Structural evidence for direct interaction between molecular components of the transverse tubule/sarcoplasmic reticulum junction in skeletal muscle. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:2587–2600. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.6.2587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bon E, Recordon-Navarro P, Durrens P. A network of proteins around Rvs167p and Rvs161p, two proteins related to the yeast actin cytoskeleton. Yeast. 2000;16:1229–1241. doi: 10.1002/1097-0061(20000930)16:13<1229::AID-YEA618>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand AH, Perrimon N. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development. 1993;118:401–415. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.2.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler MH, David C, Ochoa G-C, Freyberg Z, Daniell L, Grabs D, Cremona O, De Camilli P. Amphiphysin II (SH3; BIN1), a member of the Amphiphysin/Rvs family, is concentrated in the cortical cytomatrix of axon initial segments and nodes of Ranvier in brain and around T-tubules in skeletal muscle. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:1355–1367. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.6.1355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carozzi A, Ikonen E, Lindsay M, Parton R. Role of cholesterol in developing T-tubules. Analogous mechanisms of T-tubule and caveolae biogenesis. Traffic. 2000;1:326–341. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2000.010406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crossley A. Morphology and development of the Drosophila muscular system. In: Ashburner M, Wright T, editors. The genetics and biology of Drosophila. 2B. San Francisco, CA: Academic Press; 1978. pp. 499–560. [Google Scholar]

- David C, McPherson PS, Mundigl O, de Camilli P. A role of amphiphysin in synaptic vesicle endocytosis suggested by its binding to dynamin in nerve terminals. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1996;93:331–335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado R, Maureira C, Oliva C, Kidokoro Y, Labarca P. Size of vesicle pools, rates of mobilization and recycling at neuromuscular synapses of a Drosophila mutant, shibire. Neuron. 2000;28:941–953. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00165-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dell Angelica E, Klumperman J, Stoorvogel W, Bonifacio J. Association of the AP3 adaptor complex with clathrin. Science. 1998;280:431–434. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5362.431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitratos SD, Woods DF, Stathakis DG, Bryant PJ. Signaling pathways are focused at specialized regions of the plasma membrane by scaffolding proteins of the MAGUK family. BioEssays. 1999;21:912–921. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199911)21:11<912::AID-BIES3>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois L, Lecourtois M, Alexandre C, Hirst E, Vincent J-P. Regulated endocytic routing modulates wingless signaling in Drosophila embryos. Cell. 2001;105:613–624. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00375-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Entchev EV, Schwabedissen A, González-Gaitán M. Gradient formation of the TGF-β homolog Dpp. Cell. 2000;103:981–991. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00200-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estes PS, Roos J, van der Bliek A, Kelly RB, Krishnan KS, Ramaswami M. Traffic of dynamin within individual Drosophila synaptic boutons relative to compartment-specific markers. J Neurosci. 1996;16:5443–5456. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-17-05443.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergestad T, Davis WS, Broadie K. The stoned proteins regulate synaptic vesicle recycling in the presynaptic terminal. J Neurosci. 1999;19:5847–5860. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-14-05847.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes MS, Plantholt BA, Sperelakis N. Cytochemical staining procedures for sarcotubular systems of muscle: Modifications and applications. J Ultrastruc Res. 1977;60:306–327. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5320(77)80016-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J, Conklin M, Foell J, Wolff M, Haworth R, Coronado R, Kamp T. Reduction in density of transverse tubules and L-type calcium channels in canine tachycardia-induced heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 2001;49:298–307. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00256-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey T, Gorczyca M, Jia X, Budnik V. The Drosophila tumor suppressor gene Dlg is required for normal synaptic bouton structure. Neuron. 1994;13:823–825. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90249-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Schwarz TL. Genetic evidence for an equilibrium between docked and undocked vesicles. Phil Trans R Soc (London) B Biol Sci. 1999;354:299–306. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1999.0381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao G-C, Rehm EJ, Rubin GM. Insertion site preferences of the P transposable element in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2000;97:3347–3351. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050017397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichte B, Veh RW, Meyer HE, Kilimann MW. Amphiphysin, a novel protein associated with synaptic vesicles. EMBO J. 1992;11:2521–2530. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05317.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu SH, Towler MC, Chen E, Chen C-Y, Song W, Apodaca G, Brodsky FM. A novel clathrin homolog that co-distributes with cytoskeletal components functions in the trans-Golgi network. EMBO J. 2001;20:272–284. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.1.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLennan D. Ca2+ signalling and muscle disease. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:5291–5297. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastrogiacomo A, Parsons SM, Zampighi GA, Jenden DJ, Umbach JA, Gundersen CB. Cysteine string proteins: A potential link between synaptic vesicles and presynaptic Ca2+ channels. Science. 1994;263:981–982. doi: 10.1126/science.7906056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson PS, Garcia EP, Slepnev VI, David C, Zhang X, Grabs D, Sossin WS, Bauerfeind R, Nemoto Y, De Camilli P. A presynaptic inositol-5-phosphatase. Nature. 1996;379:353–357. doi: 10.1038/379353a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monck J, Robinson I, Escobar A, Vergar J, Fernandez JM. Pulsed laser imaging of rapid Ca2+ gradients in excitable cells. Biophys J. 1994;67:505–514. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80554-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munn AL, Stevenson BJ, Geli MI, Riezman H. end5, end6 and end7: Mutations that cause actin delocalisation and block the internalisation step of endocytosis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell. 1995;6:1721–1742. doi: 10.1091/mbc.6.12.1721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neufeld TP, Tang AH, Rubin GM. A genetic screen to identify components of the sina signaling pathway in Drosophila eye development. Genetics. 1998;148:277–286. doi: 10.1093/genetics/148.1.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell PT, Bernstein SI. Molecular and ultrastructural defects in a Drosophila myosin heavy-chain mutant. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:2601–2612. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.6.2601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Kane CJ. Enhancer traps. In: Roberts DB, editor. Drosophila: A practical approach. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 1998. pp. 131–178. [Google Scholar]

- Owen DJ, Wigge P, Vallis Y, Moore JDA, Evans PR, McMahon HT. Crystal structure of the amphiphysin-2 SH3 domain and its role in the prevention of dynamin ring formation. EMBO J. 1998;17:5273–5285. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.18.5273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peckham M, Molloy J, Sparrow J. Physiological properties of the dorsal longitudinal flight muscle and the tergal depressor of the trochanter muscle of Drosophila melanogaster. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1990;11:203–215. doi: 10.1007/BF01843574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennetta G, Pauli D. The Drosophila Sin3 gene encodes a widely distributed transcription factor essential for embryonic viability. Dev Genes Evol. 1998;208:531–536. doi: 10.1007/s004270050212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramjaun AR, Micheva KD, Bouchelet I, McPherson PS. Identification and characterisation of a nerve terminal-enriched amphiphysin isoform. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:16700–16706. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.26.16700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramjaun AR, Philie J, de Heuvel E, McPherson PS. The N terminus of amphiphysin II mediates dimerization and plasma membrane targeting. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:19785–19791. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.28.19785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razzaq A, Su Y, Mehren JE, Mizuguchi K, Jackson AP, Gay NJ, O'Kane CJ. Characterisation of the gene for Drosophila amphiphysin. Gene. 2000;241:167–174. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00451-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichmuth C, Becker S, Benz M, Debel K, Reisch D, Heimbeck G, Hofbauer A, Klagges B, Pflugfelder GO, Buchner E. The sap47 gene of Drosophila melanogaster codes for a novel conserved neuronal protein associated with synaptic terminals. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1995;32:45–54. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(95)00058-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson HM, Preston CR, Phillis RW, Johnson-Schlitz DM, Benz WK, Engels WR. A stable genomic source of P element transposase in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1988;118:461–470. doi: 10.1093/genetics/118.3.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos J, Kelly RB. Dap160, a neural-specific Eps15 homology and multiple SH3 domain-containing protein that interacts with Drosophila dynamin. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:19108–19119. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.30.19108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamuro D, Elliott K, Wechsler-Reya R, Prendergast G. BIN1 is a novel MYC interacting protein with features of a tumour suppressor. Nat Genet. 1996;14:66–77. doi: 10.1038/ng0996-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scriven D, Dan P, Moore E. Distribution of proteins implicated in the excitation–contraction coupling in cardiac myocytes. Biophys J. 2000;79:2682–2691. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76506-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seok J, Xu L, Kramarcy N, Sealock R, Meissner G. The 30-S lobster skeletal muscle Ca2+ release channel (ryanodine receptor) has functional properties distinct from the mammalian channel proteins. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:15893–15901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seugnet L, Simpson P, Haenlin M. Requirement for dynamin during Notch signaling in Drosophila neurogenesis. Dev Biol. 1997;192:585–598. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafiq S. An electron microscopical study of the innervation and sarcoplasmic reticulum of the fibrillar flight muscle of Drosophila melanogaster. Quart J Micro Sci. 1964;105:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Shupliakov O, Löw P, Grabs D, Gad H, Chen H, David C, Takei K, De Camilli P, Brodin L. Synaptic vesicle endocytosis impaired by disruption of dynamin–SH3 domain interactions. Science. 1997;276:259–263. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5310.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slepnev VI, Ochoa G-C, Butler MH, Grabs D, De Camilli P. Role of phosphorylation in regulation of the assembly of endocytic coat complexes. Science. 1998;281:821–824. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5378.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slepnev VI, Ochoa GC, Butler MH, De Camilli P. Tandem arrangement of the clathrin and AP-2 binding domains in amphiphysin I and disruption of clathrin coat function by amphiphysin fragments comprising these sites. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:17583–17589. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M910430199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith D. The structure of insect fibrillar muscle. J Biophys Biochem Cyt (Suppl) 1961;10:123–158. doi: 10.1083/jcb.10.4.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DS, Sacktor B. Disposition of membranes and the entry of haemolymph-borne ferritin in flight muscle fibres of the fly Phormia regina. Tissue and Cell. 1970;2:355–374. doi: 10.1016/s0040-8166(70)80025-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart B, Atwood H, Renger J, Wang J, Wu C. Improved stability of Drosophila larval neuromuscular preparations in haemolymph-like physiological solutions. J Comp Physiol A. 1994;175:179–191. doi: 10.1007/BF00215114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stimson DT, Estes P, Smith M, Kelly LE, Ramaswami M. A product of the Drosophila stoned locus regulates neurotransmitter release. J Neurosci. 1998;18:9638–9649. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-23-09638.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stowell MHB, Marks B, Wigge P, McMahon HT. Nucleotide-dependent conformational changes in dynamin: Evidence for a mechanochemical molecular spring. Nature Cell Biol. 1999;1:27–32. doi: 10.1038/8997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takei K, Slepnev VI, Haucke V, De Camilli P. Functional partnership between amphiphysin and dynamin in clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:33–39. doi: 10.1038/9004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ter Haar E, Harrison S, Kirchhausen T. Peptide-in-groove interactions link target proteins to the β-propeller of clathrin. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2000;97:1096–1100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas U, Ebitsch S, Gorczyca M, Koh Y, Hough C, Woods D, Gundelfinger E, Budnik V. Synaptic targeting and localization of Discs-large in a stepwise process controlled by different domains of the protein. Curr Biol. 2000;10:1108–1117. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00696-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuvia S, Buhusi M, Davis L, Reedy M, Bennett V. Ankyrin-B is required for intracellular sorting of structurally diverse Ca2+ homeostasis proteins. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:995–1007. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.5.995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallis Y, Wigge P, Marks B, Evans PR, McMahon HT. Importance of the pleckstrin homology domain of dynamin in clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Curr Biol. 1999;9:257–260. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80114-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira AV, Lamaze C, Schmid SL. Control of EGF receptor signaling via clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Science. 1996;274:2086–2089. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5295.2086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler-Reya R, Sakamuro D, Zhang J, Duhadaway J, Prendergast GC. Structural analysis of the human BIN1 gene. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:31453–31458. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigge P, Köhler K, Vallis Y, Doyle CA, Owen D, Hunt SP, McMahon HT. Amphiphysin heterodimers: Potential role in clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Mol Biol Cell. 1997a;8:2003–2015. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.10.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigge P, Vallis Y, McMahon HT. Inhibition of receptor-mediated endocytosis by the amphiphysin SH3 domain. Curr Biol. 1997b;7:554–560. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00254-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods D, Wu J, Bryant P. Localization of proteins to the apico-lateral junctions of Drosophila epithelia. Dev Genet. 1997;20:111–118. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6408(1997)20:2<111::AID-DVG4>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Koh YH, Beckstead RB, Budnik V, Ganetzky B, Bellen HJ. Synaptic vesicle size and number are regulated by a clathrin adaptor protein required for endocytosis. Neuron. 1998;21:1465–1475. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80664-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]