Loss of the Drosophila cell polarity regulator Scribbled promotes epithelial tissue overgrowth and cooperation with oncogenic Ras-Raf through impaired Hippo pathway signaling (original) (raw)

Abstract

Background

Epithelial neoplasias are associated with alterations in cell polarity and excessive cell proliferation, yet how these neoplastic properties are related to one another is still poorly understood. The study of Drosophila genes that function as neoplastic tumor suppressors by regulating both of these properties has significant potential to clarify this relationship.

Results

Here we show in Drosophila that loss of Scribbled (Scrib), a cell polarity regulator and neoplastic tumor suppressor, results in impaired Hippo pathway signaling in the epithelial tissues of both the eye and wing imaginal disc. scrib mutant tissue overgrowth, but not the loss of cell polarity, is dependent upon defective Hippo signaling and can be rescued by knockdown of either the TEAD/TEF family transcription factor Scalloped or the transcriptional coactivator Yorkie in the eye disc, or reducing levels of Yorkie in the wing disc. Furthermore, loss of Scrib sensitizes tissue to transformation by oncogenic Ras-Raf signaling, and Yorkie-Scalloped activity is required to promote this cooperative tumor overgrowth. The inhibition of Hippo signaling in scrib mutant eye disc clones is not dependent upon JNK activity, but can be significantly rescued by reducing aPKC kinase activity, and ectopic aPKC activity is sufficient to impair Hippo signaling in the eye disc, even when JNK signaling is blocked. In contrast, warts mutant overgrowth does not require aPKC activity. Moreover, reducing endogenous levels of aPKC or increasing Scrib or Lethal giant larvae levels does not promote increased Hippo signaling, suggesting that aPKC activity is not normally rate limiting for Hippo pathway activity. Epistasis experiments suggest that Hippo pathway inhibition in scrib mutants occurs, at least in part, downstream or in parallel to both the Expanded and Fat arms of Hippo pathway regulation.

Conclusions

Loss of Scrib promotes Yorkie/Scalloped-dependent epithelial tissue overgrowth, and this is also important for driving cooperative tumor overgrowth with oncogenic Ras-Raf signaling. Whether this is also the case in human cancers now warrants investigation since the cell polarity function of Scrib and its capacity to restrain oncogene-mediated transformation, as well as the tissue growth control function of the Hippo pathway, are conserved in mammals.

Background

Drosophila has long been recognized as an important model organism for elucidating oncogenic and tumor suppressor pathways [reviewed in [1]]. Traditionally two distinct classes of tumor suppressor mutants have been described, the loss of which cause either hyperplastic or neoplastic overgrowth [reviewed in [2]]. Hyperplastic overgrowth is characterized by excessive cell proliferation that is eventually restrained by terminal differentiation, while neoplastic overgrowth exhibits impaired differentiation, defects in cell polarity and the propensity to invade and metastasize.

Over recent years, a large number of hyperplastic tumor suppressor mutants have been united into a single pathway, the Hippo pathway [reviewed in [3]]. Core components of the Hippo pathway include the serine-threonine kinases Hippo (Hpo) and Warts (Wts), and their adaptor proteins, Salvador (Sav) and Mob-As-Tumor-Suppressor (Mats). Hpo phosphorylates and activates Wts, and Wts phosphorylates and thereby inactivates the transcription co-factor Yorkie (Yki). Loss of Hippo pathway components leads to reduced phosphorylation of Yki and its translocation to the nucleus where it binds to its DNA binding partner, Scalloped (Sd), and promotes expression of proteins involved in cell proliferation (Cyclin E; CycE), cell growth (Myc) and cell survival (Drosophila Inhibitor of Apoptosis 1; DIAP1) [4-11]. It is the dual role of the Hippo pathway in regulating both cell proliferation and survival functions that makes its loss such a potent driver of tissue overgrowth. The pathway is regulated through input from upstream components including Merlin and Expanded (Ex), and the transmembrane proteins Fat (Ft) and Dachsous (Ds) [12-19]. It is proposed that the primary function of the Hippo pathway is to incorporate positional cues within an epithelial field to dictate the ultimate size of organ development [20]. The pathway is highly conserved and also functions to restrain organ size in mammals. Furthermore, increasing evidence links Hippo pathway deregulation to tumorigenesis [reviewed in [21]].

In contrast to the hyperplastic Hippo pathway mutants, mutants that result in neoplastic overgrowth are characterized by alterations in cell polarity and a failure to terminally differentiate. Neoplastic mutants include the junctional scaffolding genes that regulate cell polarity, scrib, discs large (dlg) and lethal giant larvae (lgl), as well as mutants within the endocytic pathway including avalanche (avl), tumor suppressor protein 101 (TSG101) and Rab5 [reviewed in [22]]. The loss of apico-basal cell polarity and overgrowth phenotypes of a number of these mutants, including scrib, lgl, avl and TSG101 are dependent upon atypical protein kinase C (aPKC) activity, since mutant phenotypes can be rescued by reducing atypical protein kinase C function [23-25]. Direct and mutual antagonism between the junctional tumor suppressors and aPKC has been demonstrated by the ability of aPKC to associate with and phosphorylate Lgl, thereby releasing Lgl from the cell cortex and thus potentially inhibiting Lgl function [26], and the ability of Lgl to inhibit aPKC-dependent phosphorylation of other key targets [27]. Like the Hippo pathway, mammalian homologues of the Drosophila neoplastic tumor suppressors, as well as aPKC, are increasingly implicated as important players in human cancers [reviewed in [28]].

It is now becoming apparent that these two formerly separate classes of hyperplastic and neoplastic tumor regulators are interconnected. Indeed, wts mutants were originally identified based upon mutant cell morphology [29], and this is now known to be a phenotype associated with other Hippo pathway mutants and due to Yki-dependent upregulation of the apical cell polarity determinant Crumbs (Crb) and apical hypertrophy [30,31]. Crb itself acts to regulate Hippo signaling by binding to Ex [32], and either excessive Crb activity or loss of Crb results in deregulation of Ex and an impairment to Hippo signaling resulting in tissue overgrowth [32-35]. The neoplastic tumor suppressors scrib, dlg and lgl also interact with the Hippo pathway. dlg, lgl or scrib mutant follicle cells surrounding the female ovary have elevated levels of Yki targets Cyclin E and DIAP1, and exhibit strong genetic interactions with wts [36]. Furthermore, loss of lgl has been shown to impair Hippo signaling in the eye disc in an aPKC signaling-dependent manner [35]. Indeed in the wing disc both the loss of lgl or ectopic aPKC activity promotes Yki activity through an upregulation of Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) signaling [37]. Whether scrib regulates the Hippo pathway in the eye or wing disc is not yet clear. In contrast to lgl, reduced levels of Scrib in the eye disc to levels where apico-basal cell polarity is only mildly affected does not impair Hippo signaling [35], although prior studies with null alleles have demonstrated both aPKC-dependent proliferation as well as ectopic JNK signaling in scrib mutant eye disc clones [38]. Furthermore, whilst homozygous scrib mutant wing disc overgrowth is reduced in response to limiting Yki levels [35], it has not been determined if Hippo signaling is impaired in this tissue and whether the genetic interaction with yki reflects a general sensitivity of scrib mutant tissue to limiting levels of survival/proliferation functions. Clarifying the relationship between scrib and the Hippo pathway is therefore required.

In this study, we show that loss of scrib promotes eye and wing disc epithelial tissue overgrowth, as well as cooperative neoplastic overgrowth with oncogenic Ras-Raf signaling, through impaired Hippo pathway signaling. Significantly, despite JNK signaling being activated in the absence of scrib, the Hippo pathway remains impaired even when JNK is blocked. In contrast, Hippo pathway deregulation in scrib mutants is dependent upon aPKC signaling, and ectopic activation of aPKC is sufficient to downregulate the Hippo pathway independent of JNK signaling. As both the Scribble cell polarity module and the Hippo pathway are conserved in mammals, and loss of apico-basal cell polarity is a hallmark of mammalian epithelial neoplasias, it is likely that our results have significant implications for human tumorigenesis.

Results

scrib mutant eye disc cells exhibit impaired Hippo pathway signaling, and this does not require JNK signaling

We have previously reported that scrib mutant clones of tissue in the eye disc exhibit ectopic CycE expression and excessive cell proliferation, although this is restrained through JNK-dependent apoptosis [39]. If JNK signaling is blocked in scrib mutant clones by expressing a dominant negative version of Drosophila JNK, bsk (bskDN), apoptosis is prevented and mutant cells are observed to ectopically proliferate posterior to the morphogenetic furrow (MF) resulting in clonal overgrowth [38]. The ectopic cell proliferation in scrib mutant clones expressing bskDN is similar to mutants in the Hippo pathway, and therefore to determine if the Hippo pathway is impaired by the loss of scrib, we examined known targets of Hippo-mediated repression in scrib mutant eye disc clones. Targets examined included protein levels of DIAP1 [40], and expression of the enhancer traps for four-jointed (fj-lacZ) and ex (ex-lacZ), both of which are known to function as readouts of impaired Hippo signaling [17,41].

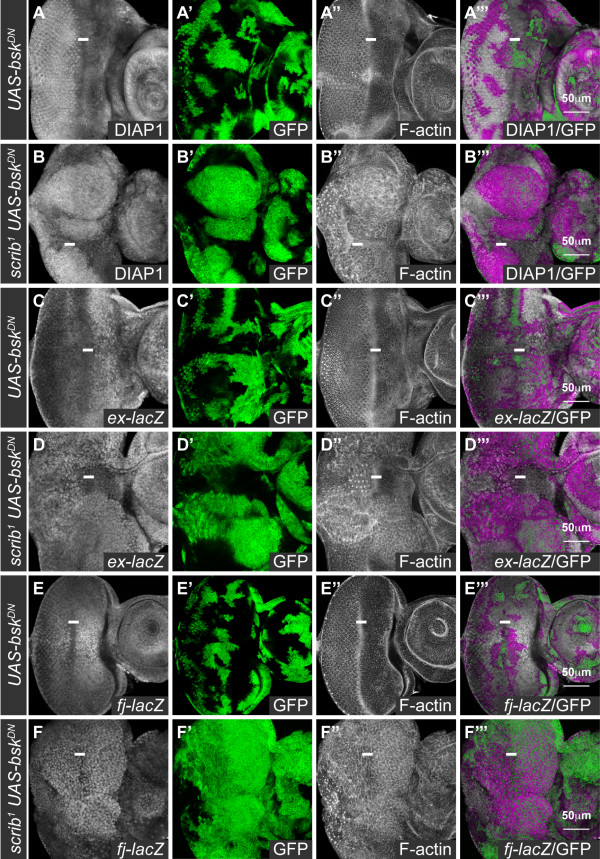

The expression of Hippo pathway reporters in scrib mutant eye disc clones were variable, possibly due to the activation of JNK-dependent cell death pathways. However DIAP1 levels were noticeably upregulated in some mutant clones, and both the ex-lacZ and fj-lacZ reporters were also consistently upregulated in the absence of scrib, indicating that the Hippo pathway was being impaired (see additional file 1). As we had previously shown that scrib mutant cells continue to ectopically proliferate in the eye disc even when JNK signaling is blocked [38], it seemed likely that this impairment to Hippo signaling would not depend upon JNK activation. However, a previous report has highlighted the role that JNK signaling can play in promoting Hippo pathway impairment [37], and therefore we also examined the expression of the reporters in scrib mutant clones in which JNK signaling was blocked by the expression of bskDN. Significantly, whilst the expression of bskDN alone in eye disc clones did not noticeably affect levels of DIAP1, ex-lacZ or fj-lacZ (Figure 1A, C, E), scrib mutant clones expressing bskDN had strikingly increased levels of DIAP1, as well as ex-lacZ and fj-lacZ expression (Figure 1B, D, F). Thus, Hippo pathway signaling was perturbed in both scrib mutant clones and scrib mutant clones expressing bskDN.

Figure 1.

scrib mutant cells expressing bskDN in the eye disc have impaired Hippo pathway signaling. Confocal sections through 3rd instar larval eye/antennal discs (A-F), posterior to the left in this and all subsequent figures. _bskDN_-expressing clones (A, C, E), and scrib1 clones expressing bskDN (B, D, F) were generated with ey-FLP and are positively marked by GFP expression (green, or magenta in the merges). Grayscale is DIAP1 (A-B), β-GAL (C-F), and F-actin to show tissue morphology (A-F). A white bar indicates the location of the morphogenetic furrow (MF) where cells are G1-phase arrested. (A, B) DIAP1 is expressed throughout the larval eye/antennal disc, and levels of the protein increase posterior to the MF in the differentiating portion of the eye disc. _bskDN_-expressing clones exhibit normal levels of DIAP1 (A), however, levels of DIAP1 are increased in scrib1 clones expressing bskDN (B). (C-F) ex-lacZ is expressed throughout the eye/antennal disc and is higher anterior to the MF in the eye disc; and fj-lacZ is expressed in a gradient in the eye disc with highest levels in the anterior centre, decreasing in levels along the dorsal, ventral and posterior axes. The expression of bskDN does not alter ex-lacZ (C) or fj-lacZ (E) expression, however, scrib1 clones expressing bskDN show elevated expression levels of ex-lacZ (D; note particularly clones of tissue posterior to the MF) and fj-lacZ (F).

The bskDN transgene is highly effective at blocking JNK signaling since it completely abrogates both the ectopic expression of the JNK pathway reporter, msn-lacZ, and the JNK pathway target, Paxillin, in scrib mutant clones [38]. However, to confirm that JNK signaling was not required for Hippo pathway impairment, we also knocked down bsk expression in scrib mutant cells using a bskRNAi transgene. Like the expression of bskDN in scrib mutant clones, this resulted in pupal lethality and in the formation of larger clones of scrib mutant tissue in the eye disc, suggesting that cells were no longer dying. Significantly, examination of BrdU incorporation indicated that mutant cells ectopically proliferated posterior to the MF, and also exhibited ectopic fj-lacZ expression (see additional file 2). Thus, whilst we do not rule out JNK-dependent effects upon the Hippo pathway in scrib mutants, our data indicates that the Hippo pathway is impaired in scrib mutant eye disc clones even when JNK signaling is blocked.

Ectopic cell proliferation, but not the loss of apico-basal cell polarity in scrib mutant cells posterior to the MF, is Yki and Sd-dependent

Hippo pathway mutant defects are Yki and Sd-dependent. Loss of Yki phosphorylation results in nuclear translocation and, through association with the DNA binding protein Sd, transcriptional activation of targets including DIAP1 and CycE. Removing Yki function can rescue Hippo pathway mutant overgrowth, however, Yki is also required for normal cell proliferation in the eye disc [7]. In contrast, Sd is largely dispensable for normal eye disc growth and proliferation and specifically mediates Hippo pathway mutant overgrowth [4,5]. Therefore, to determine if the ectopic cell proliferation and altered cell morphology of scrib mutant cells were due to loss of Hippo pathway signaling we utilized RNAi-mediated knockdown of sd function in scrib mutant eye disc clones to look for rescue of the mutant phenotype.

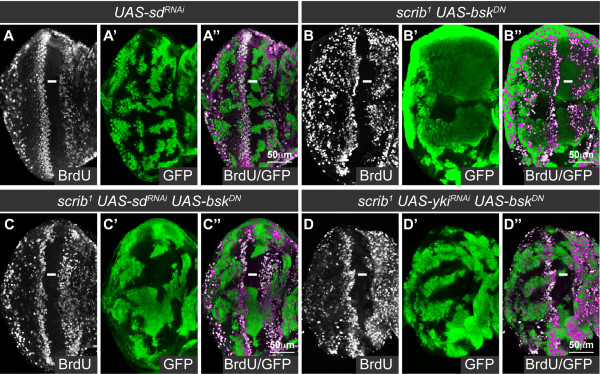

Expression of sdRNAi in otherwise wild type clones of tissue produced no discernible effect on cell viability or proliferation in larval discs (Figure 2A) and in adult eyes (data not shown). However, consistent with previous reports, when sdRNAi was expressed in wtsX1 mutant clones it completely abrogated the hyperplasia of the mutant tissue thus confirming the efficacy of sd knockdown (see additional file 3). To determine if sdRNAi could also rescue the ectopic cell proliferation in scrib mutant eye disc clones, we coexpressed sdRNAi with bskDN in scrib mutant eye disc clones. Examination of BrdU incorporation showed that although scrib mutant clones expressing bskDN exhibited ectopic BrdU incorporation posterior to the MF (Figure 2B), the coexpression of sdRNAi in the mutant tissue significantly reduced proliferation in the mutant tissue posterior to the MF (Figure 2C). Reducing sd function also efficiently abrogated the ectopic fj-lacZ expression in scrib mutant eye disc clones, thereby confirming that the rescue to proliferation correlated with a normalization in Hippo pathway reporter expression (see additional file 4). Furthermore, knockdown of yki with RNAi in scrib mutant clones expressing bskDN also significantly reduced the ectopic BrdU incorporation in scrib mutant cells posterior to the MF (Figure 2D), thus demonstrating that both Sd and Yki activity were required to drive ectopic cell proliferation.

Figure 2.

Sd and Yki are required for the ectopic cell proliferation in scrib mutant eye disc clones. Mutant eye/antennal disc clones were generated with ey-FLP and are positively marked by GFP expression (green, or magenta in the merges). Grayscale is BrdU. A white bar indicates the location of the MF. (A-D) RNAi-mediated knockdown of sd in clones does not alter the normal pattern of BrdU incorporation in the eye/antennal disc (A), whilst scrib1 clones expressing bskDN are large and ectopically proliferate posterior to the MF (B). Knockdown of sd in scrib1 clones expressing bskDN reduces the ectopic cell proliferation in the mutant clones posterior to the MF (C), and a similar rescue is shown by knockdown of yki (D).

To determine if the rescue in cell proliferation was accompanied by a restoration in mutant cell morphology, we also examined the eye disc epithelium in cross section with F-actin staining. Normally the Elav-expressing photoreceptor cells are apically localized within the pseudo-stratified columnar epithelium (Figure 3A), however, in scrib mutant clones, cells are often extruded basally and Elav-positive nuclei are aberrantly localized basally within the epithelium [38]. In scrib mutants (data not shown), or in scrib mutants protected from cell death by the expression of bskDN, knockdown of sd function with sdRNAi failed to restore normal cell morphology to the mutant tissue (Figure 3B, C). Furthermore, this did not reflect a Sd-independent activity of impaired Hippo signaling since halving the gene dosage of yki, the direct target of Hippo-mediated repression, or knockdown of yki with RNAi, also failed to restore normal cell morphology to the mutant tissue (data not shown). Thus, although scrib mutant cells ectopically proliferate due to downregulation of Hippo signaling, impaired Hippo signaling is not necessary for mediating the apico-basal cell polarity defects in scrib mutant tissue.

Figure 3.

Sd is not required for the cell morphology defects in scrib mutant clones. Cross sections of larval eye discs. Mutant clones (A-C) were generated with ey-FLP and are positively marked by GFP expression (green, or magenta and yellow in the merges). Grayscale is Elav and red is F-actin. A white bar indicates the location of the MF. (A-C) Control eye disc clones, generated using a wild type chromosome with a Flippase recognition target (FRT), show the columnar epithelial structure of the eye disc, with the apically localized nuclei of the developing photoreceptor cells marked by Elav (A). In contrast, scrib1 clones expressing bskDN show a disorganized epithelial structure resulting in Elav positive photoreceptor cell nuclei being mislocalized basally within the epithelium (B). Knockdown of sd in scrib1 clones expressing bskDN does not rescue the mutant cell morphology defects (C).

scrib mutant wing disc tissue overgrows through impaired Hippo signaling

To determine if loss of scrib could also impair Hippo signaling in other epithelial imaginal tissues, we examined the larval wing disc. Using en-GAL4 to direct RNAi-mediated knockdown of scrib in the posterior half of the wing disc, we observed a decrease in Scrib protein levels and alterations in cell morphology (see additional file 5). Significantly, this was accompanied by an increase in the expression of ex-lacZ throughout the posterior half of the wing disc and fj-lacZ in the wing pouch region (Figure 4A, B), thus confirming that loss of scrib impairs Hippo signaling in the wing disc.

Figure 4.

scrib mutant wing disc tissue overgrows through impaired Hippo signaling. Confocal sections through 3rd instar larval wing discs (A-H), posterior to the left. en-GAL4 driven expression of transgenes in the posterior half of the discs (A-D) is marked by GFP expression (green, or magenta in the merges). Grayscale is β-GAL (A-D) or F-actin (E-H). (A-D) en-GAL4 driven expression of scribRNAi in the posterior half of the wing disc increases ex-lacZ (A), fj-lacZ (B) and msn-lacZ (C) expression. Coexpression of bskDN with scribRNAi does not rescue the increased expression of fj-lacZ (D). (E-H) scrib1/scrib3 transheterozygous mutant wing discs over grow and become increasingly disorganized (E). Halving the gene dosage of yki dramatically reduces the size of homozygous scrib mutant wing discs (F). In contrast, neither halving the gene dosage of Ras85D (G) or bsk (H) reduces homozygous scrib mutant wing disc overgrowth.

Loss of lgl in the wing disc also impairs Hippo signaling, and this has been shown to depend upon JNK signaling [37]. Indeed, as in the eye disc [38,39], loss of scrib in the wing disc similarly led to the ectopic expression of the JNK pathway reporter msn-lacZ (Figure 4C). However, surprisingly, blocking JNK with the expression of bskDN failed to normalize fj-lacZ expression (Figure 4D), indicating that loss of scrib in the wing disc also results in an impairment of Hippo pathway signaling that cannot be rescued by inhibiting JNK.

Having established that Hippo signaling was perturbed by scrib knockdown in the wing disc, we next wished to confirm that this was important for driving scrib mutant tissue overgrowth. Trans-heterozygous scrib1 over scrib3 larvae fail to pupate and form giant overgrown larvae, and whilst the eye discs do not noticeably overgrow and are reduced in size presumably due to increased cell death, the wing discs over-proliferate and become highly folded and irregular in appearance (Figure 4E). To determine if wing disc overgrowth in scrib mutants was dependent upon impaired Hippo signaling we could not remove Sd function, as was done in the eye disc, since Sd is required for normal wing disc growth through association with the wing determination factor Vestigial [42,43]. Therefore, we utilized a yki null allele, ykiB5, to halve the gene dosage of yki in a scrib1/scrib3 mutant background. Consistent with previous reports [35], although giant larvae were still formed throughout an extended larval phase of development, wing disc overgrowth was dramatically reduced, resulting in significantly smaller wing discs with disorganized morphology (Figure 4F). In contrast, halving the dosage of Ras85D, a gene also essential for cell growth, proliferation and viability, did not significantly reduce wing tumor size in scrib1/scrib3 larvae (Figure 4G), thus implicating a key role for Yki in promoting tumor overgrowth. Furthermore, halving the gene dosage of bsk similarly failed to rescue the overgrown phenotype of the wing discs (Figure 4H), indicating that Bsk levels, unlike Yki levels, are not rate limiting for tumor overgrowth. Thus, loss of scrib in the wing disc promotes tissue overgrowth through downregulation of Hippo pathway signaling, and, as in the eye disc, this is likely to be, at least in part, independent of JNK.

Ras and Raf-driven neoplastic overgrowth of s_crib_ mutants is also Sd and Yki-dependent

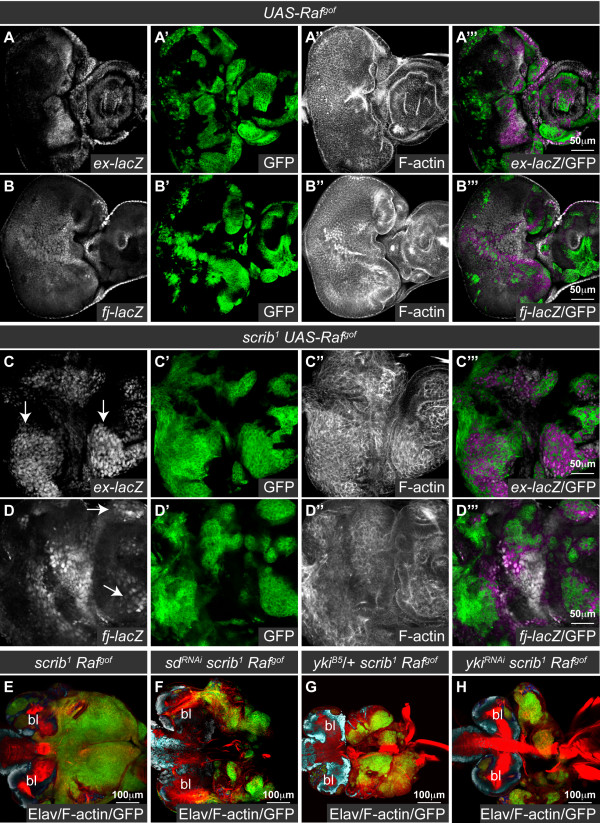

Loss of scrib also promotes tumorigenesis in cooperation with oncogenic Ras signaling [reviewed in [28]]. In a "two hit" Drosophila tumorigenesis model we have previously shown that although scrib mutant eye clones die via JNK-mediated apoptosis, if RasACT or its downstream effector, Rafgof, is expressed in the mutant clones, cell death is prevented and massive and invasive tumors develop throughout an extended larval stage [39]. To determine if downregulation of Hippo pathway signaling is also an important mediator of these overgrowths we examined the expression of the Hippo pathway reporters, ex-lacZ and fj-lacZ, in scrib- + Rafgof tumors.

The expression of ex-lacZ and fj-lacZ was predominantly unperturbed by _Rafgof_-expression alone (Figure 5A, B), however, as was observed by the loss of scrib, in scrib- + Rafgof tumors both ex-lacZ and fj-lacZ expression levels were elevated (Figure 5C, D). These data thus indicated that Hippo signaling remained impaired in the tumor and could therefore be contributing to tumor growth. To determine what role the loss of Hippo signaling played in promoting tumorigenesis, we reduced Sd activity by expressing sdRNAi in scrib- + Rafgof tumors. Examination of tumors at day 5, suggested that knockdown of sd exerted a mild effect on reducing tumor growth (data not shown), however, pupation was not restored and the tumors continued to grow throughout an extended larval phase of development. By day 8, however, _sdRNAi_-expressing tumors were significantly reduced in size compared to scrib- + Rafgof controls (Figure 5E, F), thus highlighting a role for reduced Hippo pathway signaling in promoting tumor overgrowth. To further confirm the importance of impaired Hippo signaling in scrib- + Rafgof tumorigenesis, we also halved the gene dosage of yki in the tumor background, and knocked down yki function within the tumor using a ykiRNAi transgene [5]. Consistent with the effects of sdRNAi, both methods of limiting yki function were unable to restore pupation or prevent tumor overgrowth throughout an extended larval phase of development, however, they significantly reduced tumor size (Figure 5G, H). Similar reductions in tumor overgrowth were observed when ykiRNAi was expressed in scrib- + RasACT tumors (see additional file 6). Despite the reduction in tumor overgrowth, however, knockdown of yki was unable to prevent tumor cells from adopting an invasive morphology and appearing to move between the brain lobes, as has been previously described [38], indicating that the tumor cells retained invasive capabilities (see additional file 6). Thus, similar to homozygous scrib mutants, impaired Hippo signaling promotes Ras-driven cooperative tumor overgrowth, although Yki-Sd activity is not critically rate limiting for the failure of the tumor-bearing larvae to pupate, or for the invasive nature of the tumors.

Figure 5.

Impaired Hippo pathway signaling promotes scrib1 + Rafgof neoplastic tumor overgrowth. Confocal sections through larval eye/antennal discs at day 5 (A-D) and eye/antennal discs still attached to the brain lobes (bl) at day 8 after egg laying (E-H). Mutant clones were generated with ey-FLP and are positively marked by GFP expression (green, or, in the merges, magenta in A-D and yellow in E-H). Grayscale is β-GAL (A-D), F-actin (A-D) or Elav (E-H). Red is F-actin (E-H). (A, B) Expression of Rafgof does not alter the normal pattern of ex-lacZ (A) or fj-lacZ (B) expression in the eye disc. (C-D) scrib1 + Rafgof tumors ectopically express ex-lacZ (C; arrows) and fj-lacZ (D; arrows) within the eye disc. (E-H) scrib1 + Rafgof tumors overgrow and fuse with the brain lobes throughout an extended larval stage of development (E). Knockdown of sd (F), halving the gene dosage of yki (G) or expression of ykiRNAi (H) reduces scrib1 + Rafgof tumor overgrowth.

The scrib mutant defects in Hippo signaling are aPKC-dependent, and aPKC signaling is sufficient to impair Hippo signaling even when JNK signaling is blocked

We have shown how loss of scrib impairs Hippo signaling to promote tissue overgrowth in scrib mutant eye disc clones, in homozygous scrib mutant wing discs and in cooperation with oncogenic Ras-Raf signaling. As we have also demonstrated that the impaired Hippo signaling in scrib mutants could not be rescued by reducing JNK activity, we next sought to determine what other pathways downstream of scrib could be responsible for influencing Hippo signaling. Previous work in the eye disc had shown that the increased cell proliferation posterior to the MF and alterations in cell morphology in scrib mutant clones could both be rescued by the expression of a membrane-tethered, kinase-dead (dominant negative) form of aPKC (aPKCCAAXDN), although this was not sufficient to rescue the mutant cells from JNK-dependent cell death [38]. Therefore to determine if the scrib mutant defects in Hippo pathway activity were aPKC-dependent, we examined ex-lacZ and fj-lacZ in scrib mutant clones expressing aPKCCAAXDN, that were also protected from apoptosis by the coexpression of bskDN. Strikingly, whilst the coexpression of aPKCCAAXDN and bskDN in otherwise wild type clones did not alter the normal levels of ex-lacZ and fj-lacZ expression (Figure 6A, C), when both transgenes were expressed in scrib mutant tissue, the ectopic expression of these reporters was significantly abrogated (Figure 6B, D).

Figure 6.

aPKC signaling is required for the impaired Hippo pathway signaling in scrib mutants. Larval eye/antennal discs with ey-FLP induced mutant clones marked by GFP expression (green, or magenta in the merges). Grayscale is β-GAL. A white bar indicates the location of the MF. (A-D) Coexpression of aPKCCAAXDN and bskDN in clones does not alter ex-lacZ (A) or fj-lacZ (C) expression, but when aPKCCAAXDN and bskDN are coexpressed in scrib1 clones, the normal pattern of ex-lacZ (B) and fj-lacZ (D) expression is restored (compared with scrib1 clones expressing bskDN alone in Figure 1).

Consistent with the scrib mutant defects in Hippo signaling being aPKC-dependent, ectopic activation of aPKC has been shown to be sufficient to impair Hippo signaling [35,37]. This has been linked to a capacity for aPKC to activate JNK [37], however, we have previously shown that although the expression of a truncated activated allele of aPKC (aPKCΔN) in eye disc clones induces JNK-dependent cell death, if JNK signaling is blocked, ectopic cell proliferation still ensues [38]. Indeed, the Hippo pathway reporters fj-lacZ and ex-lacZ were ectopically expressed in aPKCΔN and bskDN coexpressing eye disc clones (Figure 7A-D). Thus, aPKC signaling is not only required, but is also sufficient to impair the Hippo pathway in eye disc clones in a manner that is not dependent upon JNK activity.

Figure 7.

Ectopic aPKC signaling impairs Hippo pathway signaling even when JNK signaling is blocked. Larval eye/antennal discs with ey-FLP induced mutant clones marked by GFP expression (green, or magenta in the merges). Grayscale is β-GAL and F-actin. A white bar indicates the location of the MF. Apical (A, C) and basal (B, D) confocal sections are shown. (A-D) Coexpression of aPKCΔN with bskDN in clones results in large masses of tissue extruded basally from the epithelium which ectopically express ex-lacZ (A, B; arrows) and fj-lacZ (C, D; arrows).

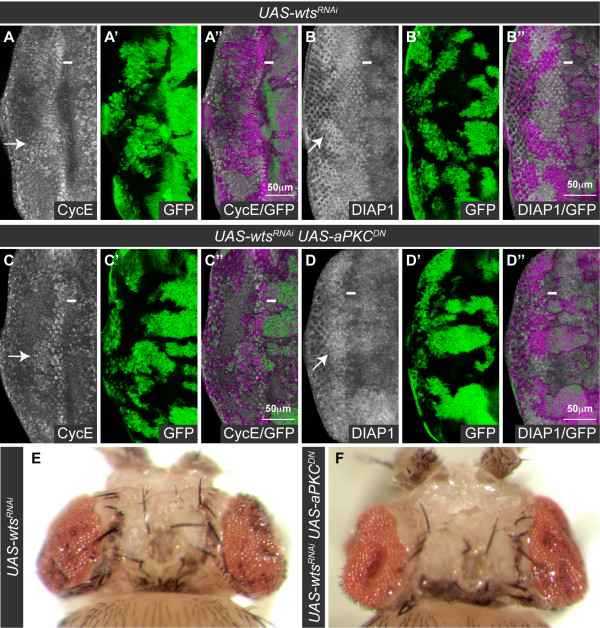

The Scrib-aPKC polarity module is not a core component of the Hippo pathway

Having demonstrated that scrib mutants showed an aPKC-dependent impairment to Hippo signaling, we next wanted to determine if aPKC signaling was also important for promoting tissue overgrowth in core Hippo pathway mutants such as wts that are known to upregulate aPKC protein levels [30,31]. However, although _wtsRNAi_-expressing clones ectopically express CycE and DIAP1 and overgrow (Figure 8A, B), similar to scrib mutant clones, coexpression of aPKCCAAXDN in wtsRNAi clones neither prevented the ectopic expression of CycE or DIAP1 (Figure 8C, D), nor suppressed the resulting overgrown adult eye phenotype (Figure 8E, F). Consistent with this, knockdown of aPKC by RNAi (to levels at which the protein was significantly reduced; see additional file 7), or overexpression of scrib or lgl was insufficient to restrain _wtsRNAi_-mediated overgrowth (see additional file 8). Similar conclusions were obtained with analyzing the more upstream Hippo pathway component, ft. Neither aPKCCAAXDN overexpression (see additional file 9), nor the overexpression of a constitutively active allele of lgl, lgl3A (data not shown), could prevent the ectopic expression of CycE in _ftRNAi_-expressing clones. Thus, aPKC signaling is not required to promote either wts or ft mutant tissue overgrowth.

Figure 8.

wts mutant overgrowth is independent of aPKC signaling. Larval eye discs (A-D) with ey-FLP induced mutant clones (green, or magenta in the merges) and dorsal views of adult mosaic flies (E, F). Grayscale is CycE (A, C) and DIAP1 (B, D). A white bar indicates the location of the MF. (A-F) Expression of wtsRNAi in eye disc clones results in upregulation of CycE (A) and DIAP1 (B) posterior to the MF (example clones highlighted with arrows), resulting in adult flies eclosing with overgrown eyes (E). Coexpression of aPKCCAAXDN with wtsRNAi does not prevent upregulation of CycE (C) and DIAP1 (D) in mutant clones (example clones highlighted with arrows), and adult flies still eclose with overgrown eyes (F).

Although these data indicated that aPKC signaling was not important for wts or ft mutant overgrowth, it was still possible that under normal conditions, when Hippo pathway activity functions to inhibit tissue overgrowth, endogenous levels of Hippo pathway activity could be susceptible to an aPKC-mediated restraint. However, knockdown of aPKC by RNAi in both the eye disc and the wing disc did not decrease DIAP1 levels (data not shown) or reduce fj-lacZ or ex-lacZ expression, as would be expected upon hyper-activation of the Hippo pathway (see additional file 10). Furthermore, overexpression of scrib or lgl in the wing disc was also insufficient to increase Hippo pathway activation and reduce fj-lacZ or ex-lacZ expression (see additional file 10). We thus conclude that during normal tissue growth, endogenous levels of aPKC activity are not required to critically restrain Hippo pathway activity, and nor are the overexpression of scrib or lgl sufficient to ectopically activate the pathway. Thus the aPKC-Scrib polarity module does not function as a core component of the Hippo pathway, and is only likely to impinge upon Hippo signaling during specific developmental or pathological contexts.

Loss of scrib impairs Hippo pathway signaling downstream, or in parallel to, expanded and fat

To gain insight into how aPKC-dependent deregulation of the Hippo pathway occurs in scrib mutants we carried out overexpression and epistasis experiments with different Hippo pathway components. Upstream regulation of Hippo signaling occurs through at least two transmembrane proteins, Ft and Crb [reviewed in [44]]. Crb acts through Ex [32-34], and Ft acts through both Ex [14,15,19] and the unconventional myosin Dachs (D) [12]. The overexpression of ex can promote ectopic Hippo signaling, and when expressed in otherwise wild type clones can restrain clonal growth in a Hpo and Wts-dependent manner [13,17,41]. Significantly, the overexpression of ex in scrib mutant eye disc clones also restrained clonal growth, and this was the case even if JNK-mediated apoptosis of the clonal tissue was prevented (Figure 9A-F). Indeed, scrib clones expressing bskDN result in pupal lethality, but the coexpression of ex was sufficient to rescue some flies to adult viability (data not shown). This indicated that in the absence of scrib, Ex was still capable of inducing Hippo pathway activation, and suggested that the Hippo pathway was affected in scrib mutants upstream or in parallel to Ex. However, despite the reduced clonal growth of scrib mutant cells expressing ex and bskDN, the mutant clones were still larger than _ex_-expressing clones alone, and the mutant tissue could still clearly be seen to ectopically express CycE posterior to the MF (Figure 9G, H). This suggested that the overexpression of ex was not able to fully inhibit Yki activation in scrib mutants and that the loss of scrib can, at least in part, impair Hippo pathway signaling downstream of, or in parallel to, ex.

Figure 9.

Loss of scrib impairs Hippo pathway signaling in parallel to expanded and fat. Larval eye/antennal disc clones generated with ey-FLP and marked by GFP expression (A-H), and wing disc clones generated by hs-FLP and marked by the absence of GFP (I, J). Green is GFP (or magenta in the merges). Grayscale is F-actin (A-F), CycE (G, H) and β-GAL (I, J). A white bar indicates the location of the MF in the eye disc (A-H), and a dashed white line marks the location of the Z-stacks shown below the wing discs (I, J). (A-C) scrib1 clones (B) are reduced in size compared to control clones (A), but expressing bskDN in the scrib1 clones dramatically increases clone size (C). (D-F) Overexpression of ex in otherwise wild type clones reduces clonal tissue size (D), and when ex is expressed in scrib1 (E), or scrib1 clones expressing bskDN (F), clonal tissue size is also greatly reduced. (G, H) Overexpression of ex in scrib1 clones expressing bskDN does not prevent ectopic expression of CycE in basally located mutant clones posterior to the MF (H, highlighted with arrow), as compared to control clones (G). (I, J) scrib1 clones generated in the wing disc (arrows) in either a transheterozygous d 1/d _GC13_mutant background (I) or homozygous ftfd exe1 (J) mutant background show increased ex-lacZ compared to the surrounding tissue.

Ft can act in parallel to Ex, and indeed the overexpression of ex in ft mutant clones is unable to restrain ft mutant tissue overgrowth [16]. We therefore next determined if impaired Ft signaling could be responsible for downregulating the Hippo pathway in scrib mutants. To do this we generated scrib clones in a d mutant animal background, since Ft acts through inhibiting D and loss of d fully abrogates ft mutant overgrowth [12] (see Figure 10). Interestingly, however, even in the absence of d we could still detect upregulation of the Hippo pathway reporter ex-lacZ in scrib mutant clones (Figure 9I), suggesting that loss of scrib also impaired Hippo signaling downstream of, or in parallel to, Ft-D. As it was possible that in fact both the Ft and Ex arms of Hippo pathway regulation were impaired in scrib mutants we next generated scrib clones in a ft ex double mutant animal background. Significantly, ex-lacZ expression was once again hyper-activated in scrib clones when compared to the basal level of pathway deregulation observed in the tissue surrounding the mutant clones that was mutant for ft and ex alone (Figure 9J). Thus, together with the ex overexpression analysis showing a degree of Hippo pathway impairment that could not be blocked by increasing Ex levels, the data is consistent with the loss of scrib impairing Hippo pathway signaling downstream, or in parallel to, both Ft and Ex (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Model for how the loss of scrib affects Hippo pathway signaling. In an epithelial cell, the core Hippo pathway components Hpo (H), Wts (W), Sav (S) and Mats (M) inhibit the activity of Yki, which acts to regulate transcription through its DNA binding partner, Sd. Extracellular regulation of the pathway occurs through the two transmembrane proteins, Crb acting through Ex, and Ft, acting through both Ex and D. Ex can also directly bind to and inhibit Yki. Loss of scrib in the eye disc is associated with aPKC-dependent inhibition of the Hippo pathway. Although JNK signaling is activated by either the loss of scrib, or ectopic aPKC activity, JNK is not required for Hippo pathway inhibition. In the wing disc, loss of scrib is also associated with JNK activation, and although JNK signaling has been shown to be sufficient to downregulate the Hippo pathway in the wing disc [37], Hippo pathway signaling remains impaired in scrib mutants even when JNK is blocked. Epistasis experiments suggest that pathway inhibition in scrib mutants occurs, at least in part, downstream or in parallel to Ex and Ft, and could impact upon either the core components (H/S/M/W) or upon Yki activity itself.

Discussion

Tumorigenesis may be considered as an abnormality in organogenesis and tissue regeneration, during which tissue growth is not restrained by signals that would normally function to restrict organ size. The Hippo pathway is a potent force in restraining organ overgrowth, and it is therefore logical that such a control mechanism would be perturbed during the unrestrained overgrowth of neoplasias. Indeed, in this study we show that loss of the neoplastic tumor suppressor scrib promotes tissue overgrowth through downregulation of the Hippo pathway. Furthermore, loss of scrib sensitizes cells to neoplastic transformation by RasACT/Rafgof, and reduced Hippo signaling cooperates with Ras-Raf to promote tumor overgrowth. Thus, impaired Hippo signaling is clearly a key force in driving scrib mutant tissue overgrowth. It is pertinent to note, however, that whilst knockdown of yki was able to completely abrogate the overgrowth of wts mutant clones (see additional file 3), it was not able to fully rescue tumor overgrowth of _scrib_- + RasACT tumors throughout an extended larval stage of development. Thus, other deregulated pathways in scrib mutants are likely to also be important for promoting tumor overgrowth. Indeed, knockdown of yki also failed to rescue the loss of apico-basal cell polarity in scrib mutants, the capacity of _scrib_- + RasACT tumor cells to invade, and the failure of the _scrib_- + RasACT tumor-bearing larvae to pupate. Although we cannot exclude the possibility that further reducing Yki activity would more effectively rescue these tumor phenotypes, the data indicate that Yki levels are not critically rate limiting for the polarity and invasive properties of scrib mutant cells.

How does scrib regulate the Hippo pathway?

The impairment to Hippo signaling in scrib mutants was significantly rescued by reducing aPKC activity. As loss of scrib is also associated with aPKC-dependent apico-basal cell polarity defects, it initially seemed probable that the Hippo pathway might be affected in scrib mutants through the deregulation of apically localized Hippo pathway receptors. Indeed, in zebrafish Scrib binds to, and functionally cooperates with, Ft [45]; and as this interaction could be conserved in Drosophila [45] very direct points of intersection between Scrib and the upstream regulators of Hippo signaling can be envisaged. Our work does not rule out this possibility, and in fact, some of our data suggest that Hippo signaling is perturbed upstream of ex since ex overexpression significantly restrained scrib mutant tissue overgrowth. However, this interpretation is complicated by Ex's capacity to directly bind to, and sequester Yki activity [46]. In fact, even ex overexpression was not sufficient to block ectopic CycE expression in scrib mutant clones, and epistasis experiments confirm that the deregulated Hippo signaling in scrib mutants is at least partially epistatic to both ex and ft, and thus downstream of two known transmembrane proteins that regulate the pathway, Crb and Ft (Figure 10). Nevertheless, despite the evidence placing scrib downstream of these proteins, there is likely to be a close relationship between Scrib's role as a cell polarity regulator and impaired Hippo signaling. Indeed, a number of recent reports indicating that increased levels of F-actin are sufficient to inhibit Hippo pathway activity [47,48] are also suggestive, since the aPKC-dependent loss of apico-basal cell polarity in scrib mutants is often associated with F-actin accumulations (data not shown). Thus, it is possible that a number of mechanisms, including receptor mislocalization and F-actin accumulation, might be operative in driving Hippo pathway impairment when apico-basal cell polarity is disrupted in scrib mutants. Interestingly, however, lgl mutant eye disc clones are not associated with the severe alterations in cell morphology characteristic of scrib mutant cells, yet the impairment to Hippo signaling in lgl mutant clones is also dependent upon aPKC activity [35]. Furthermore, Ex and Ft localization were unaffected in the absence of lgl, whilst both Hpo and Ras-associated domain family protein (RASSF) were co-mislocalized, consistent with the Hippo pathway being impaired downstream of Ft and Ex [35]. Whether a common aPKC-dependent mechanism of Hippo pathway inhibition is operative in both lgl and scrib mutant eye discs will require further investigation. We note, however, that this regulation is not likely to reflect a core, rate limiting role for Scrib-Lgl in promoting, or aPKC in repressing, Hippo pathway activity since neither overexpressing Scrib or Lgl, nor knockdown of aPKC, led to significant Hippo pathway activation. Furthermore, even though the expression of an activated form of aPKC could induce the expression of Hippo pathway reporters, and thus downregulate the pathway, neither the overexpression of a wild type, membrane-tethered aPKC in eye disc clones (data not shown), nor clones of hypomorphic scrib alleles [35, and data not shown], consistently increased DIAP1 or CycE levels. The ability of cells to accommodate such wide fluctuations in Scrib, Lgl and aPKC activity suggests that aPKC-dependent Hippo pathway inhibition may only occur during specific developmental or pathological contexts during which, for instance, a threshold level is reached whereby either compromised Scrib-Lgl activity can no longer correctly localize or restrain aPKC-mediated inhibition of the pathway, or increased aPKC levels can no longer be restrained by normal levels of Scrib-Lgl. Alternative models placing Scrib-Lgl downstream of aPKC, and thus involving an aPKC-mediated impairment to Hippo pathway signaling through inhibition of Scrib-Lgl function, also remain possible and need to be considered.

The role of JNK in Hippo pathway regulation, and differences between loss of scrib and lgl in the wing disc

A recent report indicates that the impaired Hippo pathway signaling in lgl mutant wing discs is dependent upon JNK signaling, and that ectopic aPKC signaling in the wing disc also acts through JNK to promote Yki activity [37]. In the eye disc, however, we show that Hippo pathway impairment in scrib mutants, as well as upon ectopic activation of aPKC signaling, cannot be rescued by blocking JNK, and this is also likely to be the case for lgl mutants [49]. Furthermore, in scrib mutant wing discs, although we demonstrate that JNK signaling is ectopically activated upon scrib knockdown, we also show that Hippo pathway impairment in the wing occurs, at least in part, even when JNK signaling is blocked. Why loss of scrib, unlike loss of lgl in the wing disc, does not require JNK activation to impair Hippo signaling is not yet clear. In lgl mutants, the cell polarity defects in the wing disc are also JNK-dependent [37], and while we did not analyze cell polarity markers upon scrib knockdown in the wing, one possibility is that loss of scrib is associated with JNK-independent cell polarity defects that impact upon the Hippo pathway in a similar manner to the eye disc. Certainly loss of scrib is notable for eliciting much stronger cell morphology defects in the eye disc than loss of lgl [39,50]. As the cell morphology defects in scrib mutant eye disc clones are aPKC-dependent [38], it will be important to determine what role aPKC signaling plays in the scrib mutant wing disc phenotypes.

Although our data indicates that JNK is not required for Hippo pathway impairment in scrib mutants, it does not rule out the possibility that JNK signaling still contributes to enhance Hippo pathway deregulation. Furthermore, clearly JNK plays many other important roles in neoplastic progression, including roles in promoting invasion and a failure to pupate. Indeed, the role of JNK in neoplasia is proving to be complex, since in some contexts it functions as an oncogene to promote neoplasia, whilst in different contexts it acts as a tumor suppressor through the induction of apoptosis [38,39,51-53]. Its effects upon Hippo pathway regulation may therefore also be context dependent. In fact, the activation of Hippo pathway reporters in scrib mutant clones in the eye disc (in which JNK is known to be activated) were often variable, some cells clearly showing ectopic expression of DIAP1, ex-lacZ and fj-lacZ, whilst other mutant cells did not upregulate these reporters. Non-cell autonomous effects, with increased expression in wild type cells surrounding mutant clones, were also sometimes observed (data not shown), consistent with the involvement of the Hippo pathway in regenerative proliferation around dying tissue [54]. Much of this variability appeared to be reduced when JNK signaling was blocked in the mutant clones, and whilst the rescue of some non-cell autonomous effects would be consistent with the role that JNK can play in promoting non-cell autonomous compensatory proliferation through Yki activity [37], it also remains possible that JNK may act in opposite ways to downregulate DIAP1 or other reporters in mutant cells destined to die. Further analysis will be required to decipher how cellular context defines the dual functions of JNK as tumor suppressor or oncogene, and how this is related to Hippo pathway regulation.

Emerging cross talk between the Hippo pathway and regulators of tissue architecture

Extensive cross talk is beginning to emerge between the Hippo pathway and regulators of cell morphology. Genes involved in controlling epithelial apico-basal cell polarity and levels of F-actin can impact upon Hippo pathway signaling, but reciprocally impaired Hippo signaling can affect cell morphology pathways. Loss of wts is capable of eliciting neoplastic overgrowth [55], and Hippo pathway mutants induce apical hypertrophy with increased levels of apical cell determinants such as Crb, aPKC [30,31], and F-actin [48], although, interestingly, despite the potential for increased Crb, aPKC and F-actin to promote tissue hyperplasia, the overgrowth in Hippo pathway mutants is independent of the apical hypertrophy [30,31]. This is consistent with our own work demonstrating that wts and ft mutant tissue overgrowth was independent of aPKC signaling. Furthermore, the interrelationship between Hippo and apico-basal cell polarity pathways is not confined to traditional apico-basal epithelial polarity regulators such as Scrib and aPKC, since the Hippo pathway components ft, fj and ds also participate in planar cell polarity pathways [reviewed in [56]], as do scrib [57], lgl [58] and aPKC [59,60]. The emerging picture is therefore one of a complex network of interactions whereby multiple components regulating cellular architecture are employed by cells to read their position within a morphogenetic field and respond with appropriate Hippo-pathway regulated tissue growth.

Conclusions

In summary, this work demonstrates that loss of scrib results in epithelial tissue overgrowth in both the eye and wing discs through downregulation of the Hippo pathway. Thus Scrib joins an increasing number of epithelial apico-basal cell polarity regulators that have links with Hippo pathway control. Whether these connections are operative in mammals is not yet clear, however, both the Hippo organ size control and Scribble cell polarity function are highly conserved. Loss of Hippo pathway signaling or ectopic activation of the Yki or Sd homologues, (YAP and TEAD family proteins respectively), is emerging as a powerful oncogenic force [reviewed in [21]]. Similarly, the mammalian Scrib module is increasingly implicated in tumorigenesis [reviewed in [28]], and mammalian Scrib can restrain tissue transformation by oncogenic Ras [61], and Myc [62]. Mammalian Scrib also functions within planar cell polarity pathways [63], and although links with the Hippo pathway have not yet been described, the connection is likely to be conserved since studies in the zebrafish indicate that zScrib binds to zFat1 and also promotes Hippo pathway activation [44]. The uniting of these two powerful tumor suppressor pathways clearly has important implications for human carcinogenesis. Loss of apico-basal cell polarity is considered to be a critical hallmark of neoplastic transformation, and it will be important to determine if in mammalian cancer this is also associated with defective Hippo signaling and subsequent tumor overgrowth.

Methods

Drosophila stocks

The following Drosophila stocks were used: ey-FLP1, UAS-mCD8-GFP;;Tub-GAL4, FRT82B, Tub-GAL80 [64]; y, w, hs-FLP; FRT82B, Ubi-GFP; en-GAL4; UAS-DaPKCΔN [26]; UAS-DaPKCCAAXDN [65]; UAS- aPKCRNAi (VDRC #2907); bsk2 [66]; UAS-bskDN [67]; UAS-bskRNAi (NIG #5680R-1); d1 [68]; dGC13 [12]; exe1 [69]; ex697 (ex-lacZ in all figures except Figure 9J which is exe1) [69]; UAS-ex [70]; ftfd [71]; UAS-ftRNAi (VDRC #9396); fj-lacZ [72]; UAS-lgl5.1 [26]; UAS-lgl3A [26]; UAS-phlgof (UAS-Rafgof) [73]; Ras85De1b [74]; UAS-dRas1V12 [75]; UAS-scrib19.2 [38]; FRT82B, scrib1 [76]; scrib3 [77]; UAS-scribRNAi (VDRC #27424); UAS-sdRNAi (NIG #8544R-2); wtsX1 [78]; UAS-wtsRNAi (NIG #12072R-1); ykiB5 [7]; UAS-ykiRNAi [5].

Mosaic analysis

Clonal analysis utilized either MARCM (mosaic analysis with repressible cell marker) [79] with FRT82B and _ey_-FLP1 to induce clones and mCD8-GFP expression to mark mutant tissue, or for negatively marked scrib1 clones, hs-FLP with FRT82B, Ubi-GFP. All fly crosses were carried out at 25°C and grown on standard fly media. Heat shock clones were induced by a temperature shift to 37°C for 15 minutes, and discs were harvested at 64 hours after clone induction. For the examination of scrib1 clones in a d mutant background, hs-FLP induced FRT82B, scrib1 clones were generated in a d1/dGC13, ex697, FRT40A mutant background. For the examination of scrib1 clones in a ft ex double mutant background, hs-FLP induced FRT82B, scrib1 clones were generated in a ftfd, exe1, FRT40A homozygous mutant background.

Immunohistochemistry

Imaginal discs were dissected in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) from either wandering 3rd instar larvae or from staged lays of larvae for genotypes which failed to pupate and entered an extended larval stage of development. Tissues were fixed in 4% formaldehyde in PBS, and blocked in 2% goat serum in PBT (PBS 0.1% Triton X-100). For the detection of S phase cells, a 1 h BrdU pulse at 25°C was followed by fixation, immuno-detection of GFP, further fixation, acid treatment and immuno-detection of the BrdU epitope. Primary antibodies were incubated with the samples in block overnight at 4°C, and were used at the following concentrations; mouse anti-β-galactosidase (Rockland) at 1 in 400, mouse anti-Elav (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank) at 1 in 20, rat anti-Cyclin E (Helen McNeill) at 1 in 400, mouse anti-DIAP1 (Bruce Hay) at 1 in 100, rabbit anti-GFP (Invitrogen) at 1 in 1000, mouse anti-BrdU (Becton-Dickinson) at 1 in 50. Secondary antibodies used were; anti-mouse/rat Alexa647 (Invitrogen) and anti-rabbit Alexa488 (Invitrogen) at 1 in 400. F-actin was detected with phalloidin-tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate (TRITC; Sigma, 0.3 μM) at 1 in 1000. Samples were mounted in 80% glycerol.

Microscopy and image processing

All samples were analyzed by confocal microscopy on an Olympus FV1000 microscope. Single optical sections were selected in Flouroview® software before being processed in Adobe Photoshop®CS2 and assembled into figures in Adobe Illustrator®CS2.

List of Abbreviations

aPKC: atypical protein kinase C; BrdU: bromodeoxyuridine; BSA: bovine serum albumin; bsk: basket; crb: crumbs; cycE: cyclin E; d: dachs; DIAP1: Drosophila inhibitor of apoptosis 1; dlg: discs large; DN: dominant negative; ds: dachsous; ey: eyeless; ex: expanded; fj: four-jointed; FRT: flippase recognition target; hpo: hippo; JNK: Jun N-terminal kinase; lgl: lethal giant larvae; MARCM: mosaic analysis with repressible marker; MF: morphogenetic furrow; PBS: phosphate-buffered saline; sav: salvador; scrib: scribbled; sd: scalloped; wts: warts; yki: yorkie.

Authors' contributions

KD carried out experiments for Figure 5 and Additional file 2 and 7, interpreted data and contributed editorial guidance. FAG carried out epistasis experiments for Figure 9, interpreted data and contributed editorial guidance. HER interpreted data and contributed editorial guidance. AMB conceived of the study, designed and carried out all other experiments, interpreted data, and wrote the paper. All authors read and approved of the final manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Additional file 1

scrib mutant cells in the eye disc exhibit impaired Hippo pathway signaling. Confocal sections through 3rd instar larval eye/antennal discs (A-F), posterior to the left. Control clones generated using a wild type chromosome with a Flippase recognition target (FRT) (A, C, E) and scrib1 clones (B, D, F) were generated with ey-FLP and are positively marked by GFP expression (green, or magenta in the merges). Grayscale is DIAP1 (A-B), β-GAL (C-F), and F-actin (A-F). A white bar indicates the location of the MF. (A-B) Compared to control clones (A), DIAP1 levels in scrib1 clones (B) are variable, low in some cells (arrowhead) and higher in others (arrow). (C-F) In scrib1 clones, ex-lacZ is ectopically expressed in some clones (D; arrow), but not in all mutant cells (D; arrowhead), and fj-lacZ expression is similarly upregulated in some (F; arrow), but not all, mutant clones.

Additional file 2

scrib mutant cells expressing bskRNAi have impaired Hippo pathway signaling. Larval eye/antennal discs with clones marked by GFP expression (green, or magenta in the merges). Grayscale is BrdU (A), β-Gal (B) and F-actin (B). A white bar indicates the location of the MF. (A, B) scrib1 clones expressing bskRNAi exhibit ectopic BrdU incorporation posterior to the MF (A), similar to scrib1 cells expressing bskDN (see Figure 2B), and ectopic expression of fj-lacZ within the mutant tissue (B; arrow).

Additional file 3

Knockdown of sd and yki rescues wts mutant overgrowth. Larval eye/antennal discs (A-D) with clones marked by GFP expression (green, or magenta in the merges), and dorsal views of adult mosaic flies (E, F). Grayscale is BrdU (A, B) and β-Gal (C, D). A white bar indicates the location of the MF. (A, B) wtsX1 mutant clones ectopically proliferate posterior to the MF (A), however, expression of sdRNAi in wtsX1 mutant clones restores the normal pattern of cell proliferation (B). (C, D) The ectopic expression of fj-lacZ in wtsX1 mutant clones (C) is reduced, although not completely normalized, by sdRNAi expression in the mutant clones (D; compare to C in which the expression extends to the edges of the disc). (E, F) Expressing sdRNAi in wtsX1 mutant clones rescues _wtsX1_-mediated pupal lethality, and adult flies eclose with normal sized, although slightly roughened, adult eyes (E). The expression of ykiRNAi in wtsX1 mutant eye disc clones (F) produces a similar rescue of eye disc overgrowth and adult fly viability as sdRNAi.

Additional file 4

Knockdown of sd normalizes fj-lacZ expression in scrib mutant clones. Larval eye/antennal disc clones marked by GFP (green, or magenta in the merges). The location of the MF is indicated by a white bar. Grayscale is β-Gal. (A-C) Expression of sdRNAi in clones does not alter the normal pattern of fj-lacZ expression (A), but when sdRNAi is expressed in scrib1 clones (B), or scrib1 clones expressing bskDN (C), it prevents ectopic fj-lacZ expression in the mutant tissue (compare to Figure 1F).

Additional file 5

Expression of scribRNAi reduces Scrib protein levels. Confocal section through a 3rd instar larval wing disc. en-GAL4 driven expression of scribRNAi in the posterior half of the disc is marked by GFP expression (green, or magenta in the merges). Grayscale is Scrib and F-actin. (A) en-GAL4 driven expression of scribRNAi greatly reduces Scrib protein levels and results in abnormalities in tissue morphology, as observed by F-actin.

Additional file 6

Knockdown of yki reduces Ras-driven tumor overgrowth, although tumor cells retain invasive capabilities. Pairs of larval eye/antennal discs attached to the brain lobes at day 10, with mutant tissue generated by ey-FLP and marked by GFP expression (green, or yellow in the merges). Red is F-actin. (A-C) scrib1 + RasACT tumors are massively overgrown and fused together (A), but knockdown of yki within the tumors significantly restrains tumor overgrowth (B), although tumor cells are still observed moving between the brain lobes (arrows) indicating that they retain invasive capabilities (C).

Additional file 7

Expression of aPKCRNAi reduces aPKC protein levels. Larval eye/antennal disc with mutant tissue generated by ey-FLP and marked by GFP expression (green, or magenta in the merges). Grayscale is aPKC and F-actin. (A) Expression of aPKCRNAi in clones greatly reduces aPKC protein levels, although tissue morphology, as observed by F-actin, remains relatively unperturbed.

Additional file 8

Ectopic cell proliferation in wtsRNAi clones is rescued by sd knockdown, but not by decreasing aPKC or increasing Lgl-Scrib levels. Dorsal views of adult mosaic flies (A, B, D-F), and larvae eye disc clones (C) generated by ey-FLP and marked by GFP (green, or magenta in the merges) and CycE (grayscale). A white bar indicates the location of the MF. (A-B) Expression of sdRNAi with wtsRNAi rescues the _wtsRNAi_-dependent overgrown adult eye phenotype (A), but knockdown of aPKC does not rescue wts mutant overgrowth (B; see Figure 8E for a comparison of _wtsRNAi_-expressing adult flies). (C, D) Expression of an allele of lgl that can't be inactivated by aPKC phosphorylation (lgl3A) neither prevents ectopic CycE expression posterior to the MF (C; arrow), nor rescues the overgrown adult eye phenotype (D) of _wtsRNAi_-expressing clones. (E-F) Overexpression of wild type versions of lgl (E) or scrib (F) do not rescue the wtsRNAi overgrown adult eye phenotype.

Additional file 9

Ectopic cell proliferation in _ftRNAi_-expressing clones cannot be rescued by aPKCDN expression. Larval eye discs with GFP-expressing mutant clones (green, or magenta in the merges) induced by ey-FLP. Grayscale is CycE, and the MF is indicated by a white bar. (A, B) _ftRNAi_-expressing clones ectopically express CycE posterior to the MF (A; arrow), and this is not blocked by the coexpression of aPKCCAAXDN (B; arrow).

Additional file 10

Endogenous aPKC signaling does not limit Hippo pathway activity. Larval eye discs (A, B) with ey-FLP induced clones, and wing discs (C-F) with en-GAL4 driven expression of transgenes (green, or magenta in the merges). Grayscale is β-GAL (A-F), and F-actin (A, B). A white bar indicates the location of the MF in the eye discs. (A-D) Expression of aPKCRNAi in eye disc clones or in the wing disc does not reduce ex-lacZ (A, C) or fj-lacZ (B, D) expression, in fact ex-lacZ expression in the wing disc is slightly elevated. (E, F) The normal pattern of fj-lacZ expression in the wing disc is not altered by overexpression of wild type versions of scrib (E) or lgl (F).

Contributor Information

Karen Doggett, Email: karen.doggett@ludwig.edu.au.

Felix A Grusche, Email: Felix.Grusche@petermac.org.

Helena E Richardson, Email: helena.richardson@petermac.org.

Anthony M Brumby, Email: tony.brumby@petermac.org.

Acknowledgements

We thank Linda Parsons, Kieran Harvey and Patrick Humbert for helpful discussions, Greg Leong for technical help with the initial experiments looking at DIAP1 levels in scrib mutants, Barry Dickson for supplying the scribRNAi transgenic flies, and D. Bilder, S. Campuzano, K. Harvey, B. Hay, J. Jiang, J. Knoblich, H. McNeill, J. Treisman, the Bloomington Stock Centre, the Vienna Drosophila RNAi Centre (VDRC), the National Institute of Genetics (NIG) Fly Stock Centre and the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank for contributing fly stocks and/or reagents. This work was supported by grants from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) to AMB (NHMRC Grant#350396 and Grant#509051) and HER (NHMRC Senior research Fellowship B and NHMRC Grants). FG was the recipient of a Melbourne International Research scholarship and Melbourne International Fee Remission Scholarship from the University of Melbourne. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- Brumby AM, Richardson HE. Using Drosophila melanogaster to map human cancer pathways. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:626–39. doi: 10.1038/nrc1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariharan IK, Bilder D. Regulation of imaginal disc growth by tumor-suppressor genes in Drosophila. Annu Rev Genet. 2006;40:335–61. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.39.073003.100738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey K, Tapon N. The Salvador-Warts-Hippo pathway - an emerging tumor-suppressor network. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:182–91. doi: 10.1038/nrc2070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S, Liu Y, Zheng Y, Dong J, Pan D. The TEAD/TEF family protein Scalloped mediates transcriptional output of the Hippo growth-regulatory pathway. Dev Cell. 2008;14:388–98. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Ren F, Zhang Q, Chen Y, Wang B, Jiang J. The TEAD/TEF family of transcription factor Scalloped mediates Hippo signaling in organ size control. Dev Cell. 2008;14:377–87. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goulev Y, Fauny JD, Gonzalez-Marti B, Flagiello D, Silber J, Zider A. SCALLOPED interacts with YORKIE, the nuclear effector of the hippo tumor-suppressor pathway in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2008;18:435–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Wu S, Barrera J, Matthews K, Pan D. The Hippo signaling pathway coordinately regulates cell proliferation and apoptosis by inactivating Yorkie, the Drosophila Homolog of YAP. Cell. 2005;122:421–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong J, Feldmann G, Huang J, Wu S, Zhang N, Comerford SA, Gayyed MF, Anders RA, Maitra A, Pan D. Elucidation of a universal size-control mechanism in Drosophila and mammals. Cell. 2007;130:1120–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh H, Irvine KD. In vivo regulation of Yorkie phosphorylation and localization. Development. 2008;135:1081–8. doi: 10.1242/dev.015255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neto-Silva RM, de Beco S, Johnston LA. Evidence for a growth-stabilizing regulatory feedback mechanism between Myc and Yorkie, the Drosophila homolog of Yap. Dev Cell. 2010;19:507–20. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziosi M, Baena-Lopez LA, Grifoni D, Froldi F, Pession A, Garoia F, Trotta V, Bellosta P, Cavicchi S, Pession A. dMyc functions downstream of Yorkie to promote the supercompetitive behavior of hippo pathway mutant cells. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001140. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao Y, Rauskolb C, Cho E, Hu WL, Hayter H, Minihan G, Katz FN, Irvine KD. Dachs: an unconventional myosin that functions downstream of Fat to regulate growth, affinity and gene expression in Drosophila. Development. 2006;133:2539–51. doi: 10.1242/dev.02427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler DM, Baker NE. Expanded and fat regulate growth and differentiation in the Drosophila eye through multiple signaling pathways. Dev Biol. 2007;305:187–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willecke M, Hamaratoglu F, Kango-Singh M, Udan R, Chen CL, Tao C, Zhang X, Halder G. The fat cadherin acts through the hippo tumor-suppressor pathway to regulate tissue size. Curr Biol. 2006;16:2090–100. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva E, Tsatskis Y, Gardano L, Tapon N, McNeill H. The tumor-suppressor gene fat controls tissue growth upstream of expanded in the hippo signaling pathway. Curr Biol. 2006;16:2081–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y, Irvine KD. Fat and expanded act in parallel to regulate growth through warts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:20362–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706722105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamaratoglu F, Willecke M, Kango-Singh M, Nolo R, Hyun E, Tao C, Jafar-Nejad H, Halder G. The tumor-suppressor genes NF2/Merlin and Expanded act through Hippo signaling to regulate cell proliferation and apoptosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:27–36. doi: 10.1038/ncb1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellock BJ, Buff E, White K, Hariharan IK. The Drosophila tumor suppressors Expanded and Merlin differentially regulate cell cycle exit, apoptosis, and Wingless signaling. Dev Biol. 2007;304:102–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett FC, Harvey KF. Fat cadherin modulates organ size in Drosophila via the Salvador/Warts/Hippo signaling pathway. Curr Biol. 2006;16:2101–10. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogulja D, Rauskolb C, Irvine KD. Morphogen control of wing growth through the Fat signaling pathway. Dev Cell. 2008;15:309–21. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao B, Lei QY, Guan KL. The Hippo-YAP pathway: new connections between regulation of organ size and cancer. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2008;20:638–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaccari T, Bilder D. At the crossroads of polarity, proliferation and apoptosis: The use of Drosophila to unravel the multifaceted role of endocytosis in tumor suppression. Mol Oncol. 2009;3:354–65. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2009.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu H, Bilder D. Endocytic control of epithelial polarity and proliferation in Drosophila. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:1232–9. doi: 10.1038/ncb1324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls MM, Albertson R, Shih HP, Lee CY, Doe CQ. Drosophila aPKC regulates cell polarity and cell proliferation in neuroblasts and epithelia. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:1089–98. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200306079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert MM, Robinson BS, Moberg KH. Functional interactions between the erupted/tsg101 growth suppressor gene and the DaPKC and rbf1 genes in Drosophila imaginal disc tumors. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7039. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betschinger J, Mechtler K, Knoblich JA. The Par complex directs asymmetric cell division by phosphorylating the cytoskeletal protein Lgl. Nature. 2003;422:326–30. doi: 10.1038/nature01486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirtz-Peitz F, Nishimura T, Knoblich JA. Linking cell cycle to asymmetric division: Aurora-A phosphorylates the Par complex to regulate Numb localization. Cell. 2008;135:161–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humbert PO, Grzeschik NA, Brumby AM, Galea R, Elsum I, Richardson HE. Control of tumorigenesis by the Scribble/Dlg/Lgl polarity module. Oncogene. 2008;27:6888–907. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Justice RW, Zilian O, Woods DF, Noll M, Bryant PJ. The Drosophila tumor suppressor gene warts encodes a homolog of human myotonic dystrophy kinase and is required for the control of cell shape and proliferation. Genes Dev. 1995;9:534–46. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.5.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamaratoglu F, Gajewski K, Sansores-Garcia L, Morrison C, Tao C, Halder G. The Hippo tumor-suppressor pathway regulates apical-domain size in parallel to tissue growth. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:2351–9. doi: 10.1242/jcs.046482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genevet A, Polesello C, Blight K, Robertson F, Collinson LM, Pichaud F, Tapon N. The Hippo pathway regulates apical-domain size independently of its growth-control function. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:2360–70. doi: 10.1242/jcs.041806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling C, Zheng Y, Yin F, Yu J, Huang J, Hong Y, Wu S, Pan D. The apical transmembrane protein Crumbs functions as a tumor suppressor that regulates Hippo signaling by binding to Expanded. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:10532–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004279107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CL, Gajewski KM, Hamaratoglu F, Bossuyt W, Sansores-Garcia L, Tao C, Halder G. The apical-basal cell polarity determinant Crumbs regulates Hippo signaling in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA . 2010;107:15810–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004060107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson BS, Huang J, Hong Y, Moberg KH. Crumbs regulates Salvador/Warts/Hippo signaling in Drosophila via the FERM-domain protein Expanded. Curr Biol. 2010;20:582–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzeschik NA, Parsons LM, Allott ML, Harvey KF, Richardson HE. Lgl, aPKC, and Crumbs regulate the Salvador/Warts/Hippo pathway through two distinct mechanisms. Curr Biol. 2010;20:573–81. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao M, Szafranski P, Hall CA, Goode S. Basolateral junctions utilize warts signaling to control epithelial-mesenchymal transition and proliferation crucial for migration and invasion of Drosophila ovarian epithelial cells. Genetics. 2008;178:1947–71. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.086983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun G, Irvine KD. Regulation of Hippo signaling by Jun kinase signaling during compensatory cell proliferation and regeneration, and in neoplastic tumors. Dev Biol. 2011;350:139–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.11.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leong GR, Goulding KR, Amin N, Richardson HE, Brumby AM. Scribble mutants promote aPKC and JNK-dependent epithelial neoplasia independently of Crumbs. BMC Biol. 2009;7:62. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-7-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumby AM, Richardson HE. scribble mutants cooperate with oncogenic Ras or Notch to cause neoplastic overgrowth in Drosophila. Embo J. 2003;22:5769–79. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tapon N, Harvey KF, Bell DW, Wahrer DC, Schiripo TA, Haber DA, Hariharan IK. salvador Promotes both cell cycle exit and apoptosis in Drosophila and is mutated in human cancer cell lines. Cell. 2002;110:467–78. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00824-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho E, Feng Y, Rauskolb C, Maitra S, Fehon R, Irvine KD. Delineation of a Fat tumor suppressor pathway. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1142–50. doi: 10.1038/ng1887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halder G, Polaczyk P, Kraus ME, Hudson A, Kim J, Laughon A, Carroll S. The Vestigial and Scalloped proteins act together to directly regulate wing-specific gene expression in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3900–9. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.24.3900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmonds AJ, Liu X, Soanes KH, Krause HM, Irvine KD, Bell JB. Molecular interactions between Vestigial and Scalloped promote wing formation in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3815–20. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.24.3815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grusche FA, Richardson HE, Harvey KF. Upstream regulation of the hippo size control pathway. Curr Biol. 2010;20:R574–82. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skouloudaki K, Puetz M, Simons M, Courbard JR, Boehlke C, Hartleben B, Engel C, Moeller MJ, Englert C, Bollig F. et al. Scribble participates in Hippo signaling and is required for normal zebrafish pronephros development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:8579–84. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811691106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badouel C, Gardano L, Amin N, Garg A, Rosenfeld R, Le Bihan T, McNeill H. The FERM-domain protein Expanded regulates Hippo pathway activity via direct interactions with the transcriptional activator Yorkie. Dev Cell. 2009;16:411–20. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansores-Garcia L, Bossuyt W, Wada K, Yonemura S, Tao C, Sasaki H, Halder G. Modulating F-actin organization induces organ growth by affecting the Hippo pathway. Embo J. 2011;30:2325–35. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez BG, Gaspar P, Bras-Pereira C, Jezowska B, Rebelo SR, Janody F. Actin-Capping Protein and the Hippo pathway regulate F-actin and tissue growth in Drosophila. Development. 2011;138:2337–46. doi: 10.1242/dev.063545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzeschik NA, Parsons LM, Richardson HE. Lgl, the SWH pathway and tumorigenesis: It's a matter of context & competition! Cell Cycle. 2010;9:3202–12. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.16.12633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grzeschik NA, Amin N, Secombe J, Brumby AM, Richardson HE. Abnormalities in cell proliferation and apico-basal cell polarity are separable in Drosophila lgl mutant clones in the developing eye. Dev Biol. 2007;311:106–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igaki T, Pagliarini RA, Xu T. Loss of cell polarity drives tumor growth and invasion through JNK activation in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1139–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlirova M, Bohmann D. JNK- and Fos-regulated Mmp1 expression cooperates with Ras to induce invasive tumors in Drosophila. Embo J. 2006;25:5294–304. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumby AM, Goulding KR, Schlosser T, Loi S, Galea R, Khoo P, Bolden JE, Aigaki T, Humbert PO, Richardson HE. Identification of novel Ras-cooperating oncogenes in Drosophila melanogaster: a RhoGEF/Rho-family/JNK pathway is a central driver of tumorigenesis. Genetics. 2011;188:105–25. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.127910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grusche FA, Degoutin JL, Richardson HE, Harvey KF. The Salvador/Warts/Hippo pathway controls regenerative tissue growth in Drosophila melanogaster. Dev Biol. 2011;350:255–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menut L, Vaccari T, Dionne H, Hill J, Wu G, Bilder D. A mosaic genetic screen for Drosophila neoplastic tumor suppressor genes based on defective pupation. Genetics. 2007;177:1667–77. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.078360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifert JR, Mlodzik M. Frizzled/PCP signaling: a conserved mechanism regulating cell polarity and directed motility. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:126–38. doi: 10.1038/nrg2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courbard JR, Djiane A, Wu J, Mlodzik M. The apical/basal-polarity determinant Scribble cooperates with the PCP core factor Stbm/Vang and functions as one of its effectors. Dev Biol. 2009;333:67–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dollar GL, Weber U, Mlodzik M, Sokol SY. Regulation of Lethal giant larvae by Dishevelled. Nature. 2005;437:1376–80. doi: 10.1038/nature04116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djiane A, Yogev S, Mlodzik M. The apical determinants aPKC and dPatj regulate Frizzled-dependent planar cell polarity in the Drosophila eye. Cell. 2005;121:621–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]