RYBP Represses Endogenous Retroviruses and Preimplantation- and Germ Line-Specific Genes in Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells (original) (raw)

Abstract

Polycomb repressive complexes (PRCs) are important chromatin regulators of embryonic stem (ES) cell function. RYBP binds Polycomb H2A monoubiquitin ligases Ring1A and Ring1B and has been suggested to assist PRC localization to their targets. Moreover, constitutive inactivation of RYBP precludes ES cell formation. Using ES cells conditionally deficient in RYBP, we found that RYBP is not required for maintenance of the ES cell state, although mutant cells differentiate abnormally. Genome-wide chromatin association studies showed RYBP binding to promoters of Polycomb targets, although its presence is dispensable for gene repression. We discovered, using Eed-knockout (KO) ES cells, that RYBP binding to promoters was independent of H3K27me3. However, recruiting of PRC1 subunits Ring1B and Mel18 to their targets was not altered in the absence of RYBP. In contrast, we have found that RYBP efficiently represses endogenous retroviruses (murine endogenous retrovirus [MuERV] class) and preimplantation (including zygotic genome activation stage)- and germ line-specific genes. These observations support a selective repressor activity for RYBP that is dispensable for Polycomb function in the ES cell state. Also, they suggest a role for RYBP in epigenetic resetting during preimplantation development through repression of germ line genes and PcG targets before formation of pluripotent epiblast cells.

INTRODUCTION

Embryonic stem (ES) cells originate from a transient population of uncommitted cells in the inner cell mass of the preimplantation blastocyst (44), soon after epigenetic reprogramming of the fertilized egg (35). ES cells are uniquely endowed with the ability to undergo orderly differentiation to a variety of cell lineages (36). Self-renewal of such a pluripotent state is achieved through the robust activity of an interconnected set of transcription factors (pluripotency network) that uses chromatin modifiers to define an ES cell-specific epigenetic landscape (64).

While not strictly required for ES cell self-renewal, Polycomb group (PcG) proteins are indispensable for execution of genetic programs that coordinate commitment and differentiation to other cell states (5, 9, 12, 24, 26, 39). PcG transcriptional roles depend, at least in part, on histone-modifying activities characteristic of the two major types of Polycomb repressive complexes (PRCs): PRC2, which trimethylates lysine 27 of histone H3 (H3K27me3), and PRC1, which monoubiquitylates lysine 119 of histone H2A (H2AK119Ub1) (49, 51). Although the precise roles of these modifications are still not fully understood, they correlate with a singular transcriptional state of promoters by which they are silent but poised for prompt activation (10, 12, 30, 34, 53). PRC2 and PRC1 appear as assemblies of some heterogeneity, around the catalytic component and other core subunits essential for their stability and optimal histone modification. Histone monoubiquitylation relies on RING finger E3 ligases Ring1A and Ring1B (11, 59). Biochemical analysis shows that, in addition to PRC1 complexes, Ring1A and Ring1B appear as components of other H2A monoubiquitylating complexes, often containing Ring and YY1 binding protein (RYBP) (16, 47, 54).

RYBP was identified as a direct interactor with Ring1A (14). It acts as transcriptional repressor in reporter assays, both in tissue culture cells and in the fly Drosophila melanogaster (2, 14). RYBP, or its paralog Yaf2, does not form part of the canonical PRC1 complex (27), perhaps because of the mutually exclusive association of either RYBP or PRC1 chromobox subunits with Ring1 proteins (61). Germ line inactivation of RYBP interferes with embryonic development that arrests at early stages around gastrulation (41). RYBP associates in vitro with YY1, a transcription factor whose DNA binding domain is conserved in Drosophila PcG homologs Polyhomeotic (Pho) and Pho-l (6, 7, 14). The potential to associate with a DNA binding protein underlies a proposed role as recruiter of PcG complexes to their targets. However, despite some evidence for such an activity (62, 63), chromatin association studies in ES cells failed to show YY1 colocalization with PcG targets (33). Importantly, in ES cells RYBP is also part of protein complexes containing core transcription factors of the pluripotent network (Pou5f1/Oct4) (57, 60), and ES cell lines cannot be established from RYBP-deficient early embryos (41).

Here, we have studied RYBP function in ES cells by using conditionally deficient RYBP cells. We found that ES cell maintenance is largely independent of RYBP, although it acts as a repressor of germ line-specific genes and loci typically expressed in preimplantation development, such as murine endogenous retroviruses (MuERVs) and genes expressed at the zygotic gene activation (ZGA) stage. In contrast, repression of PcG target genes was found to be modest and silencing of developmental regulators was mostly independent of RYBP. Chromatin association studies in wild-type and mutant ES cells suggest a role in resetting of the epigenetic landscape during preimplantation development.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

ES cell culture and differentiation.

_RYBP_-floxed ES cell lines 10 and 15 were derived from blastocysts generated in crosses between mice homozygous for a floxed RYBP allele. Males also carried a Rosa26::CreERT2 gene for inducible deletion of RYBP sequences. Gene targeting details will be described in a future work (M. Vidal and H. Koseki, unpublished data). RYBP inactivation was carried out by adding to the cultures 4′-hydroxytamoxifen (4′-OHT) at 0.8 μM (Sigma-Aldrich). Control cells received ethanol (EtOH). After 18 h, cells received fresh medium. _Ring1A_−/− _Ring1B_fl/fl Rosa26::CreERT2 (Ring1A/B conditional-double-knockout [dKO]), _Eed_-KO, _Dnmt1_-KO, and Dnmt1/3a/3b (triple-knockout [TKO]) ES cells were described previously (12, 55). ES cells were cultured using standard conditions on mitotically inactivated mouse embryo fibroblasts. To initiate differentiation to embryo bodies, 200 ES cells previously cultured for 4 days (+d4) after EtOH or 4′-OHT treatment were grown in hanging drops in medium without leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) for 4 days. Four days later, cell aggregates in the drops were combined and grown in bulk for the indicated times.

Proliferation and apoptosis assays.

Proliferation rates were estimated using cultures that received 5-bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU; 10 μM; Becton Dickinson); after 20 min, cells were trypsinized, fixed, permeabilized, and stained using a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) BrdU Flow kit (Becton Dickinson). Growth curves were obtained from counts of viable cells in triplicate 6-cm dishes cultures at the indicated days. TUNEL (terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling) assessment of apoptosis was done by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) after staining with the In Situ Cell Death Detection alkaline phosphatase (AP) kit (Roche Diagnostics).

ES cell immunofluorescence and histochemistry.

Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA), permeabilized, and incubated with anti-RYBP (1:500) (14), anti-Oct3/4 (1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc.; clone C-10), and anti-SSEA1 antibodies (1:400; mouse ascitic fluid; clone MC-480; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank). Following incubation with fluorophore-coupled secondary antibodies, cell nuclei were stained with 4′,6-diamino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Alkaline phosphatase was visualized using a histochemistry detection kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

Yaf2 knockdown (KD).

Lentiviral particles were produced in 293T cells by using a calcium-phosphate coprecipitation method with envelope and packaging plasmids and pLKO lentiviral vectors expressing Yaf2 small hairpin RNA (shRNA) (TRCN0000095206 and TRCN0000095204) or control shRNA (RNAi Consortium; distributed by Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). ES cells were cultured with supernatant containing lentiviral particles for 16 h in the presence of Polybrene (4 μg/ml). On the next day, fresh medium was added, and on the following day, puromycin selection (1.1 μg/ml) was applied. Four days later, cells were harvested.

Gene expression microarray analysis and quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (RT-qPCR).

Total RNA was extracted using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and purified with Qiagen RNeasy separation columns (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). For microarray analysis, first-strand cDNA was synthesized and hybridized to Affymetrix GeneChip Mouse Genome 430 2.0 arrays (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). The signal intensities (CEL format) of probe sets in each chip were processed using open source program R (http://www.r-project.org/) with bioinformatics package Bioconductor (http://www.bioconductor.org/). After microarray scans, retrieved signals were normalized using a quantile normalization algorithm and signals corresponding to present intensity were aggregated for each gene. Expression changes per each gene between two experiments were estimated from the geometric mean of intensity ratios of probes assigned to the gene. Normalization and calculation of expression change were performed using our in-house program written in Python. Results were statistically evaluated using methods suitable for data types. Statistical evaluation of skewness of gene distribution was performed using hypergeometric distribution for contingency tables. Gaussian distributions sharing the same variances were compared using the t test. Distributions that did not fit t test conditions were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test.

For RT-qPCR, total RNA was reverse transcribed using a SuperScript Vilo cDNA synthesis kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). A qPCR analysis was performed in triplicate using 150 ng cDNA per reaction mixture and SYBR Green-based mixes in Stratagene's Mx3005P thermal cycler. Gene expression data were analyzed with MxPro ET software (Agilent Technologies). β-Actin expression was used for normalization. Sequences of primer pairs for qPCR are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material.

Western blotting.

Membranes were incubated with anti-RYBP (14), anti-Lsd1 (Abcam; ab17721), and antitubulin (Sigma; clone B-5-1-2) diluted in Tris-buffered saline–0.05% Tween 20 (TBST) followed by washes and subsequent incubation with horseradish peroxidase-coupled anti-IgG antibodies (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) in TBST. Membrane-bound antibodies were detected using chemiluminescence (SuperSignal; Pierce, Thermo Fisher Scientific).

ChIP-qPCR and ChIP-on-chip experiments.

Chromatin of wild-type and mutant ES cells was cross-linked using 1% formaldehyde–phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), resuspended in RIPA buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, 140 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS, 0.1% deoxycholic acid) containing protease inhibitors, and sonicated into 0.5- to 1.0-kb fragments using a Bioruptor sonicating device (Diagenode, Belgium). Immunoprecipitation was carried out with antibodies to RYBP, Ring1B, or Mel18 (Santa Cruz; H-115) as described previously (12). Anti-RYBP antibody performance in chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis was validated by the large differences between amounts of DNA immunoprecipitated from chromatin of wild-type and RYBP-KO ES cells. Quantification of immunoprecipitated DNA was done after DNA purification and qPCR using SYBR green, with each PCR performed in triplicate. Primers are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Enrichment (fraction of input DNA immunoprecipitated) was calculated from the threshold cycle (Δ_C_T) values for each sample relative to input chromatin. Nonspecific rabbit (RYBP and Mel18) or mouse (Ring1B) IgG was used as a negative control.

For ChIP-on-chip analysis, immunoprecipitated and input DNA were labeled and hybridized to the Mouse Promoter ChIP-on-chip microarray set (G4490A; Agilent, Palo Alto, CA) according to the Agilent mammalian ChIP-on-chip protocol (v.9.0). Immunoprecipitated DNA with specific or control antibodies was subjected to T7 RNA polymerase-based amplification as described previously (56), labeled, and hybridized. Scanned images were quantified with Agilent Feature Extraction software under standard conditions and after normalization compared to identify enriched regions. Signals that could not be distinguished from background (P value, ≥10−7) and without enriched probes around them (500 bp) were discarded to reduce noise. The most enriched sequences represent a gene index, and the distributions of these indices were approximated to fit two Gaussian distributions using the EM algorithm. As lower enrichment distributions correspond to control signals and upper enrichment distributions correspond to specific antibody-bound sequences, we took the mean (μ) and standard deviation (SD) of lower distribution to define background signals and genes with indices ≥μ + 2 SDs were scored as bound genes.

DNA methylation analysis.

A bisulfite genomic sequencing approach was used according to the manufacturer's instructions (EpiTect Bisulfite kit; Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Bisulfite-treated DNA was used in PCRs to amplify regions of interest using primers shown in Table S1 in the supplemental material, cloned using TOPO TA cloning, and sequenced as previously described (50).

CGI definition and promoter DNA methylation.

The CpG island (CGI) was defined by two criteria, GC composition and the ratio of the observed CG dinucleotide frequency to the expected frequency (O/E ratio). GC composition and O/E ratio are calculated using a 200- to 500-bp window. A 250-bp sliding window was used to define whether a nucleotide is inside or outside CGI from kb −4 to kb +4 of the transcription start site (TSS). CGI length was given by the number of bases inside each thus-defined CGI. DNA methylation status was obtained by aggregation of methylated or unmethylated cytosines detected using reduced representation of bisulfite sequencing (RRBS) (32). Sequences were downloaded, and ratios of methylated CpG dinucleotide around TSSs (kb −4 to +4) were calculated.

Microarray data accession number.

Complete ChIP-chip and gene expression data are available from the Gene Expression Omnibus (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) under accession number GSE32294.

RESULTS

RYBP-deficient ES cells.

Attempts to generate ES cells from constitutively RYBP-deficient embryos resulting from intercrosses of RYBP+/− mice have been reported to be unsuccessful (41). Therefore, we generated a mouse line bearing a floxed RYBP gene (RYBPfl) that could be inactivated in the presence of 4′-OHT-inducible Cre recombinase expressed from a Rosa26::CreERT2 gene. Gene deletion removes most coding potential (amino acids 54 to 226), leaving only a short N-terminal region encoded by exons located 56 kb upstream of deleted sequences (Fig. 1A; see also Fig. S1A in the supplemental material). Mutant cells could be propagated in culture without morphological signals of differentiation, and their proliferation rate, estimated from BrdU incorporation, was similar to that of wild-type cells (Fig. 1C). In addition, 4′-OHT-treated ES cells (_RYBP_-KO) maintained levels of Oct4, SSEA1, and alkaline phosphatase activity, markers of pluripotent, undifferentiated cells, similar to those of EtOH-treated cells (wild type, Fig. 1D). We observed a transient decrease in cell accumulation soon after 4′-OHT treatment (see Fig. S1B) likely related to the presence of floating, TUNEL-positive cells (see Fig. S1C). The developmental potential of _RYBP_−/− ES cells was analyzed by measuring gene expression during differentiation as embryo bodies formed from mutant and wild-type cells. The data showed that while expression of pluripotency genes Oct4 and Nanog was commonly downregulated, differentiation-driven activation of lineage-specific genes differed between cells expressing and those lacking RYBP (Fig. 1E). Together, the data suggest that RYBP is not essential to the maintenance of the undifferentiated state of ES cells but that its activity is required for proper differentiation.

Fig 1.

RYBP-deficient ES cells. (A and B) Western blot of cell extracts and phase-contrast images from cultures after 4 days of ethanol (EtOH) or hydroxytamoxifen (4′-OHT) treatment. (C) BrdU incorporation during a 20-min pulse in cells grown for different times after treatments (4 or 12 days [+d4 or +d12, respectively]). (D) Expression of stem cell markers in ethanol-treated (wild-type) or 4′-OHT-treated (_RYBP_-KO) ES cells identified by immunofluorescence (Oct4 and SSEA1) or immunohistochemistry (alkaline phosphatase [AP]). RYBP immunofluorescence was included as a control of gene inactivation. (E) Deregulated differentiation of _RYBP_-mutant ES cells. Time course (days in x axis) gene expression analysis by RT-qPCR of mRNAs encoding cell lineage markers; error bars are SDs of relative mRNA levels indicated in the y axis.

RYBP represses preimplantation and germ line-specific genes.

We investigated RYBP control of gene expression in ES cells using microarray analysis of RNA isolated from RYBPf/f ES cells cultured for 4 or 12 days after EtOH or 4′-OHT treatment (+d4 and +d12, respectively). Compared to control cells, 288 and 505 genes were found upregulated (false discovery rate [FDR] α = 0.05; fold change, ≥2) in +d4 and +d12 mutant ES cells, respectively. Downregulated transcripts (fold change, ≤0.5), however, were encoded by smaller gene sets, 47 and 83 genes for +d4 and +d12 cells, respectively, suggesting that RYBP acts as a transcriptional repressor.

Maximum changes in expression levels corresponded to genes expressed at preimplantation stages and at the zygotic gene activation (ZGA) developmental stage (2-cell embryo) in particular (18). Among them were genes encoding members of protein families such as DUF1438 (Tcstv1, Tcstv3, AF067061, AF067063, D13Ertd608e, and LOC100038935), E1f1a (Eif1a, EG666806/Gm8300, and 100039042/Gm2016), and Zscan4 and also retrogenes such as Zfp352, Tdpoz1, and others. Another significant group of upregulated transcripts was encoded by germ line-specific genes such as Dazl, Mael, Ddx4, and Mov10l1 and members of the Pramel family of genes (Pramel3 and Pramel4). Figure 2A illustrates upregulation of these two groups of RYBP targets in +d4 cells. A reduced subset of PcG targets was also upregulated (some examples appear in Fig. 2A). Interestingly, those marking the core of developmental regulators (i.e., Ring1B bound, enriched in both H3K27me3 and H2AK119Ub1) are poorly represented (17% versus 40% in Ring1-deficient ES cells for ≥2-fold-changed genes and 13% and 48% for ≥4-fold-changed genes, respectively) (Fig. 2C). Further support for this conclusion comes from the frequency of promoter structures within upregulated genes (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material) showing statistical correlation with short (100- to 700-bp) but not with long (>2-kb) CpG islands (CGIs), characteristic of PcG-repressed developmental regulators (22). Validation of transcriptome alterations in RYBP-mutant ES cells by RT-qPCR is shown in Fig. 2B.

Fig 2.

Gene expression alterations in RYBP-deficient ES cells. (A) Microarray analysis of preimplantation- and germ line-specific genes upregulated in _RYBP_-KO cells shortly (4 days) after 4′-OHT treatment. Polycomb targets include a random set of core targets (Ring1B bound and H3K27me3 and H2AK119Ub1 marked). Mean values, deduced from fluorescence intensities, and SDs of duplicate experiments with each of two independent ES cell lines. (B) RT-qPCR values of gene expression changes validating results from microarray analysis indicated as means and SDs of four to six experiments. Bars filled in black, dark gray, or light gray correspond to preimplantation- and germ line-specific genes and Polycomb targets, respectively. (C) Comparison of genes upregulated in RYBP-deficient and Ring1A- and Ring1B-deficient ES cells 4 days after 4′-OHT treatment. Absolute number of genes (within bars) and relative number (in parentheses) of upregulated genes corresponding to chromatin categories defined by H3 and H2A marks and Ring1B binding, as indicated. Note the underrepresentation of core PcG targets in _RYBP_-mutant ES cells. Numbers in italics correspond to values when gene expression changes in +d12 _RYBP_-KO ES cells are considered.

Since the overall impact of RYBP on regulation of PcG targets was smaller than anticipated, we wished to evaluate the possibility of functional compensation of RYBP deficiency by its paralog Yaf2. We used a knockdown (KD) approach on conditionally RYBP-deficient ES cells expressing control or Yaf2 small hairpin RNAs followed by gene expression analysis using Affymetrix microarrays. This allowed us to generate _Yaf2_-KD ES and _RYBP_-KO ES cells (single mutants) and also _Yaf2_-KD _RYBP_-KO ES cells (double mutant) when 4′-OHT was given to cells infected with Yaf2 shRNA-expressing lentiviral particles. Comparing expression changes of PcG targets in single mutant cells with those in cells with concurrent inactivation of RYBP and Yaf2, we observed no synergistic effects such as would be expected for a putative compensation of RYBP deficiency by Yaf2 (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Thus, in ES cells, RYBP actively represses preimplantation- and germ line-specific genes whereas it shows a moderate silencing activity on a specific set of PcG targets.

RYBP-specific silencing of MuERV-family endogenous retroviruses.

Many of the preimplantation-specific genes upregulated in RYBP-deficient ES cells are repressed by the histone demethylase Lsd1/Kdm1a (28). _Lsd1_−/− ES cells also derepress a subset of endogenous retroviruses. Therefore, we asked whether RYBP would also act as a repressor of repetitive sequences and used RT-qPCR to test for expression of long terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposons in +d4 cells treated with 4′-OHT or EtOH. We found extensive derepression of MuERV transcripts (Fig. 3A) but not of MusD or intracisternal A particle (IAP) mRNAs. MuERV transcripts spanned the entire transcriptional unit, as detected with primers specific for both 5′ and 3′ LTRs and the Gag-encoding region (Fig. 3C). As some of the preimplantation-specific genes upregulated in _Lsd1_-mutant ES cells have their transcripts initiated within cryptic nearby LTRs (28), we tested such a possibility for three of these genes commonly derepressed in _RYBP_- and _Lsd1_-KO ES cells. Using forward primers complementary to LTR sequences 5′ to Zfp352, Tcstv3, and Ubtfl1, together with reverse primers complementary to protein-coding sequences, we identified by RT-qPCR highly upregulated transcripts (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material), suggesting that, at least in some cases, cryptic LTRs are also active in RYBP-deficient ES cells.

Fig 3.

RYBP represses endogenous retroviruses. (A) Upregulation of MuERV mRNAs among those encoded by LTR-retroelements measured by RT-qPCR of ES cells after 4 days of 4′-OHT treatment. (B and C) Schematic representation of MuERV retroelements and expression. RT-qPCR expression analysis of indicated regions. LTR, long terminal repeat; Gag, Pro-pol, and dUTPase, gene region encoding a Gag-Pro dUTPase polyprotein; PBS, primer binding site; PPT, polypurine tract. Means and SDs of three experiments are shown. (D) Lsd1 levels in wild-type and _RYBP_-mutant ES cells.

The remarkable overlap between derepressed genes in _RYBP_−/− and _Lsd1_−/− ES cells prompted us to ask about a possible Lsd1 destabilization in _RYBP_-mutant ES cells and about upregulation as an indirect consequence of RYBP inactivation. Figure 3D is a Western blot showing decreasing levels of RYBP with time after 4′-OH treatment without decreases in Lsd1 signals, thus supporting an autonomous role for RYBP repression of retrotransposons and preimplantation-specific and other genes in ES cells.

RYBP association with chromatin.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by identification of isolated DNA using hybridization to Agilent microarrays (ChIP-chip) was used to determine RYBP association with promoters. We found 239 genes bound by RYBP. This gene set was particularly enriched in H3K27me3-marked promoters (3- to 4-fold above expected frequency of K4me3− K27me3+ and K4me3+ K27me3+ [bivalent] genes). Promoters enriched in H2K119Ub1 nucleosomes were still further overrepresented within RYBP-bound genes (>7-fold above expected frequency [Fig. 4A]). Many of these genomic regions correspond, precisely, to PcG targets, although they remained transcriptionally unaffected by RYBP deletion. As expected, analysis of associated CGIs showed that the fraction of long, CpG-dense CGIs was particularly overrepresented among RYBP-bound genes (Fig. 4B), further supporting the notion of stable association of RYBP with PcG-modified genomic regions.

Fig 4.

RYBP association with chromatin. (A and B) Distribution of RYBP-bound promoters according to histone marks and CGI length. In panel B, the fraction of total CGI promoters in each category (defined by CGI length) is indicated. The data showed preferential association with those marked with H3K27me3 (K4− K27+, P = 4.4 × 10−48; K4+ K27+, P = 8.1 × 10−15) and long CGIs. Note the enrichment in promoters bearing H2AK119Ub1 marks (H2AUb1+, P = 1.7 × 10−43); this subset of K4+ K27+ promoters corresponds to core PcG targets. (C) Distinctive Ring1B and RYBP enrichment around transcription start sites (TSSs) (denoted by arrows) depending on their response to RYBP inactivation, showing a relatively higher RYBP density on promoters upregulated in RYBP-deficient ES cells. (D) ChIP-qPCR assay of RYBP and Ring1B enrichment including promoters of preimplantation-specific genes repressed in an RYBP-dependent manner that are not included in the microarray. (E) RYBP association with genomic regions of LTR-retrotransposons using ChIP-qPCR. IgG was used as a control for nonspecific binding. Means and SDs of two or three experiments indicated.

Relative RYBP and Ring1B enrichment (as intensities of hybridization signals) showed distinct patterns depending on the transcriptional responses to the absence of RYBP. In general, genes upregulated in RYBP-deficient ES cells showed decreased enrichment in Ring1B and RYBP compared to those showing unaltered expression. In particular, Ring1B density was reduced in comparison to that of RYBP. Thus, although quantitative estimations of an RYBP-to-Ring1B ratio cannot be determined (different antibodies), the data are consistent with RYBP-repressed promoters containing a relatively higher RYBP content (Fig. 4C). ChIP-qPCR validation of RYBP and Ring1B binding to genes upregulated and not upregulated in _RYBP_−/− ES cells is shown in Fig. 4D. This does not imply a unique repressive role for RYBP, since Ring1A- and Ring1B-double-deficient ES cells also upregulate Ddx4, Mael, and Dazl. Interestingly, their expression was unchanged in Mel18-Bmi1-double-deficient ES cells (see Fig. S5A in the supplemental material), suggesting a silencing function unrelated to PRC1. Together, the data show that no clear transcriptional outcome can be deduced only from the presence of RYBP. Instead, distinct chromatin structures, perhaps determined by the nature of associated RYBP complexes, correlate with RYBP repression. Similarly, we found RYBP specifically associated with LTR-proximal regions of MusD, IAP, and MuERV retroelements (Fig. 4E), despite the fact that only MuERVs are silenced in an RYBP-dependent manner. We conclude that both RYBP complex(es) and chromatin context dictate RYBP-dependent transcriptional activity, essential for repression in some cases (preimplantation- and germ line-specific genes and MuERVs) but dispensable in others (H2AK19Ub1-PcG targets).

H3K27me3-independent association of RYBP with chromatin.

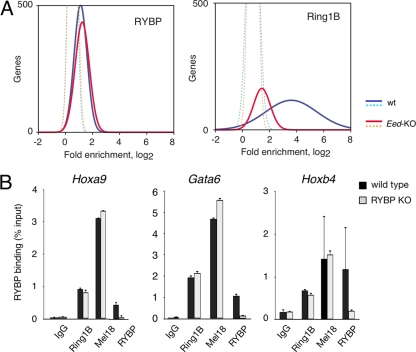

H3K27me3 recognition by chromatin readers promotes both its maintenance through cell division and PRC1 recruiting (8, 17, 23, 29). Binding of PRC2 core subunit Eed to H3K27me3 nucleosomes is essential for mark propagation, and Eed-deficient ES cells are almost devoid of H3K27me3. _Eed_-mutant cells fail to recruit PRC1 (25). Frequent RYBP-H3K27me3 colocalization led us to ask whether RYBP binding would be affected in the absence of the histone mark. ChIP-chip studies on _Eed_−/− ES cells identified 432 RYBP-bound genes, most of which had been identified in wild-type cells (common promoter enrichment, 26.4-fold; P = 7.69 × 10−192). Moreover, quantitative comparison of RYBP enrichment between wild-type and _Eed_-mutant ES cells showed almost-superimposed distributions (Fig. 5A), consistent with RYBP binding genomic regions in an H3K27me3-independent fashion. In contrast, Ring1B enrichment in _Eed_−/− cells differed dramatically from that of wild-type cells (Fig. 5A), indicating, as expected, a substantial dependence on H3K27me3 nucleosomes.

Fig 5.

RYBP binds genomic regions in an H3K27me3-independent manner but does not contribute to PRC1 recruiting. (A) Distribution of hybridization intensity signals of coimmunoprecipitated DNA in wild-type (wt) and Eed-deficient ES cells compared to those of control antibodies (dotted lines). RYBP-bound plots showed no differences between wild-type and _Eed_-KO ES cells (left), whereas Ring1B enrichment in mutant cells dramatically decreased. The results indicate distinct responses to histone modification so that RYBP binding to promoters, but not Ring1B, is essentially independent of H3K27me3 marks. (B) PRC1 recruiting to targets is independent of RYBP. ChIP-qPCR analysis of Ring1B and Mel18 (PRC1 subunits) localization to the indicated PcG targets in wild-type and RYBP-deficient ES cells, showing little or no variation with changes in RYBP levels. RYBP binding was used as a control of RYBP depletion in mutant cells. Means and SDs of two experiments shown.

Since RYBP is able to bind genomic regions independently of H3K27me3, we asked whether it would participate in Ring1B recruiting to PcG targets. We used ChIP-qPCR to assay for binding of PRC1 subunits Ring1B and Mel18 to PcG targets Gata6, Hoxa9, and Hoxb4 in RYBP-deficient and wild-type ES cells. We found that Ring1B and Mel18 enrichments at these regions were similar in the two cell types, whereas that of RYBP decreased, as expected, in RYBP-mutant cells (Fig. 5B). We conclude that Ring1B and Mel18 recruitment to targets is independent of RYBP. Furthermore, we found Ring1B association with chromatin of LTR-retrotransposons also to be independent of RYBP (see Fig. S5B in the supplemental material).

RYBP and DNA methylation.

DNA-methylated germ line-specific genes and members of the Rhox cluster of homeobox genes are, as in _RYBP_-mutant ES cells, derepressed in cells deficient in DNA methyltransferases (13, 38). Indeed, the average expression of DNA-hypermethylated genes is higher in _RYBP_−/− ES cells than in wild-type cells (see Fig. S6A in the supplemental material). In agreement with this observation, genes upregulated in _RYBP_-mutant ES cells and in _Dnmt1_−/− ES cells overlapped significantly (Fig. S6B) and, to a lesser extent, overlapped with those upregulated in TKO ES cells lacking all three DNA methyltransferases (Fig. S6C), suggesting a link between RYBP and DNA methylation repressive pathways. Therefore, although much of RYBP localized to unmethylated genes, we asked whether RYBP binding would be affected in cells lacking Dnmt1. We performed ChIP-chip analysis on _Dnmt1_−/− ES cells and identified a total of 344 RYBP-bound genes overlapping, in part, the set of promoters bound in wild-type cells (common promoter enrichment, 14.3-fold; P = 5.86 × 10−57). Interestingly, RYBP enrichment for all genes examined in _Dnmt1_-KO ES cells tended to be CGI restricted, whereas that in wild-type cells was also found in regions adjacent to CGIs and in inter-CGI regions. Examples of both methylated and unmethylated genes are shown in Fig. 6A. These results make it unlikely that the altered RYBP binding in _Dnmt1_-mutant cells is related to DNA methylation status. Therefore, we asked whether upregulation of methylated genes in _RYBP_-mutant cells would be accompanied by DNA methylation changes. The content in methylated cytosines was determined by sequencing bisulfite-treated genomic DNA. The results (Fig. 6B) showed that, following RYBP inactivation, the promoter-proximal CGI of some genes (Mael and Rhox6) underwent modest DNA demethylation, whereas other genes (Dazl and Ddx4) showed no differences from wild-type ES cells. On the other hand, LTR-retroelements remained methylated in RYBP-deficient ES cells, regardless of their derepressed (MuERV) or unchanged (IAP and MusD) status (see Fig. S7 in the supplemental material). Together, the results suggest that RYBP and DNA methylation act as parallel repressive pathways.

Fig 6.

RYBP binding to chromatin in Dnmt1-deficient ES cells and effects of RYBP depletion on DNA methylation. (A) Enrichment profiles of RYBP bound to methylated promoters (Mael, Dazl, Mov10l1, and Ddx4, upregulated in _RYBP_-KO ES cells) and unmethylated promoters (Lef1, Bmp6, and Hmx3, not affected by RYBP deletion). Red sectors indicate CGI locations, and TSSs are depicted by arrows. RYBP enrichment in _Dnmt1_-mutant cells colocalized closely with CGI regions regardless of promoter class. (B) Methylation patterns of CGI promoters upregulated in RYBP-mutant ES cells. Cartoons delineate locations of CGIs relative to TSSs (arrows). CpG nucleotides are shown by black (methylated) or white (unmethylated) circles. Methylation extent is given as percentage of methylated CpG and shows little or no variation between wild-type (wt) and RYBP-deficient ES cells.

DISCUSSION

RYBP and ES cell state.

By using conditionally mutant ES cells, we have shown that RYBP is largely dispensable for ES cell self-renewal. As ES cells cannot be established from constitutively RYBP-deficient blastocysts (41), it is tempting to suggest that RYBP is required for the generation of the ES cell state but not after it has been attained. In addition, RYBP is required for orderly, coordinated ES cell differentiation, although inactivation of the pluripotency network takes place in RYBP-deficient ES cells. These alterations, however, are not unexpected given the developmental abnormalities of _RYBP_−/− embryos and are also observed with other epigenetic regulators, which typically are unnecessary for maintenance of pluripotent ES cells but are required for their appropriate differentiation (9, 39, 55).

RYBP as an element of repressive strategies for a variety of loci.

The apparently small effects on undifferentiated mutant ES cells, however, are accompanied by prompt upregulation of about 300 genes. The group that showed the highest response to RYBP inactivation contained endogenous retroviruses and preimplantation-stage genes, of which some may use promoters from nearby LTRs (21, 28), perhaps making them part of the same altered repressive pathway. Another group of RYBP-repressed targets is that of germ line genes, whereas, surprisingly, RYBP contribution to silencing of PcG targets is rather modest.

Repression of LTR-retroelements in ES cells uses distinctive chromatin modifiers: class I (murine leukemia virus [MLV]) and class II (IAP and MusD) elements, but not class III elements (MuERVs), use histone methyltransferase Setdb1 (21, 31). In contrast, MuERV silencing depends on Lsd1 (28) and, as we show here, on RYBP. These alternative repressive pathways may underlie different developmental expression patterns by which MuERV transcript accumulation peaks at the 2- to 4-cell stage, before that of IAP or MusD transcripts (40). Lsd1 complexes contain histone deacetylases (HDACs), and indeed, MuERV silencing is abrogated by HDAC inhibitors (28). RYBP was not among subunits of Lsd1 complexes isolated in ES cells (28). It may be that repression of these targets uses both Lsd1- and RYPB-mediated activities and that when either of them is defective, repression is lost. Thus, a multiplicity of nonredundant players is at play in MuERV repression in ES cells, including Kap1, which also participates in silencing class II retroelements (45). A thorough biochemical characterization of complexes containing these players is due in order to understand their apparently independent workings.

Among RYBP-repressed genes, a subset including germ line-specific genes is also upregulated in ES cells defective in DNA methylation machinery (13, 21, 38). If, as it is believed, partial/total loss of DNA methylation underlies derepression of these targets, then the absence of changes in DNA methylation that we observed in _RYBP_-mutant ES cells implies that RYBP and DNA methylation-mediated repression would act in parallel. RYBP repression of methylated genes would be yet another example of complex regulatory strategies used in ES cells to silence DNA-methylated targets which appear responsive to perturbations in more than one epigenetic regulator (19, 21). Further evidence of the multiplicity of epigenetic inputs in the regulation of RYBP targets is their derepression in _Eed_-KO ES cells (see Fig. S8 in the supplemental material), supporting transcriptional control through nonredundant, parallel silencing mechanisms.

Given its association with Ring1B, the limited effect of RYBP on repression of PcG targets was unanticipated. The subset of these targets encoding developmental regulators with promoters enriched in H2A-monoubiquitylated nucleosomes is particularly insensitive to RYBP deficiency. We show that this is not due to compensation by its paralog Yaf2, an observation in line with previous reports showing distinctive functions for the two paralogs (48, 52). Moreover, in _RYBP_-mutant ES cells, these promoters remain associated with PRC1 subunits. The data support a critical role for canonical Polycomb complexes in the maintenance of the silenced state of developmental regulators and argue against a central role for RYBP collaborating with PcG in the maintenance of the ES cell state. While it cannot be ruled out that the minimal Ring1B association with targets in _Eed_-KO ES cells depends precisely on RYBP, it is clear that when Eed is present, RYBP is dispensable for stable association of PRC1 subunits with targets. Therefore, RYBP function at these sites may relate to dynamic fine-tuning of the activity of complex(es) with little, direct impact on transcriptional repression.

RYBP association with chromatin.

RYBP colocalizes extensively with H3K27me3- and H3K119Ub1-marked nucleosomes on long CGI promoters repressed independently of RYBP. Moreover, RYBP density at these loci is higher than that at other loci, including retroelements and preimplantation- and germ line-specific genes, whose repression is RYBP dependent. Promoters with decreased RYBP enrichment tend to locate near short CGIs or in regions of low CpG density. Thus, differences in RYBP association with chromatin correlate with distinctive chromatin structure at these genomic regions, suggesting different recruiting mechanisms, possibly forming part of different complexes. At first glance, RYBP complexes might exclude H3K27me3 readers, the chromobox proteins (3), due to their mutually exclusive association with Ring1 proteins (61). However, the stoichiometry of these complexes is not well established, and if as current evidence shows, PcG complexes contain more than one Ring1 protein, the coexistence of RYBP and chromobox proteins in some of the complexes would be feasible. RYBP reportedly binds H2AK119Ub1 (1), thereby providing an alternative recruiting possibility. However, given that H2A deubiquitylation precedes mitosis (20), a previous step of PRC1 or PRC1-related association would appear necessary. Importantly, our finding that RYBP binds genomic regions with no or very low H3K27me3 (_Eed_-KO ES cells) suggests additional possibilities for association, although it is not clear to what extent RYBP binding to genomic regions occurs independently of H3K27me3 readers in wild-type cells. Obviously, YY1, the RYBP interactor able to bind DNA, might act as a recruiter. Current evidence, however, is not consistent with this possibility, given the poor overlap between YY1-bound loci and PcG targets (33). Indeed, RYBP-bound genes or the genes derepressed in _RYBP_-mutant ES cells distinguish statistically independent sets from those of genes bound by YY1 (see Fig. S9 in the supplemental material). In contrast, another RYBP interactor, the YY1 paralog Rex1/Zfp42, has been found to associate with some PcG targets (15), making it worthwhile to explore as a candidate for RYBP recruitment. Our ChIP data clearly associate RYBP with CGI regions, particularly in cells lacking Dnmt1. Given that in ES cells only some of these CGIs are methylated while most are not (PcG targets), it is unlikely that alterations of RYBP-binding-pattern _Dnmt1_-KO ES cells relate to DNA methylation. In this regard, our previous observation of the ability of RYBP to associate nonspecifically with DNA (37) may be pertinent in assisting, guided by DNA binding proteins, RYBP localization to genomic regions.

A possible role for RYBP in preimplantation development.

The fact that promoters activated very early in development, such as those of MuERVs and ZGA genes, are repressed in ES cells in an RYBP-dependent manner makes it conceivable that RYBP also plays a similar repressive function at later preimplantation stages. Kap1 and Lsd1 repressions of LTR-retrotransposons in morulae and blastocysts are examples (28, 45).

Such a hypothetical role during preimplantation development may not be restricted to only endogenous retroviruses and ZGA genes. It may also include germ line-specific genes or even PcG targets, making RYBP a possible player in resetting the epigenetic landscape that follows postfertilization erasing of histone marks and DNA methylation (35, 58). Germ line genes are a major set of loci that undergo DNA methylation during embryo development (4). Although ES cells are DNA hypermethylated (42), pluripotent cells in the blastocyst acquire DNA methylation during the transition to epiblast cells in the postimplantation embryo (4). This modification seems to occur on genes previously silent, as part of a swapping of repressive pathways like that observed for repetitive elements (46). In this scenario, RYBP might participate in the priming of such an initial silent state. Likewise, for PcG targets, although Ezh2 and Ring1B are expressed during preimplantation development (43), it might be possible that RYBP-mediated silencing would mark sites for subsequent PRC2 and PRC1 localization and repression. RYBP function here would be dependent on its ability to bind long CGI regions in an H3K27me3-independent manner. RYBP would serve a seeding function whereby, once RYBP-assisted PRC1-PRC2 localization takes place, PcG self-sustained maintenance would make it dispensable, much as occurs in ES cells.

In summary, we have shown that RYBP is largely dispensable for maintenance of undifferentiated ES cells but necessary for faithful execution of their developmental potential. We have also found that RYBP acts as a transcriptional repressor of endogenous retroviruses (MuERVs) and preimplantation- and germ line-specific genes and that, while its contribution to PcG targeting and repression is rather modest, its ability to bind CGI regions in an H3K27me3-independent manner suggests a role during epigenetic landscape resetting at very early developmental stages.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Neil Brockdorff (Oxford University, United Kingdom) for providing _Eed_-KO ES cells, Masaki Okano (RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology, Japan) for making available _Dnmt1_-KO and TKO ES cells, and M. Iida for derivation of _RYBP_-mutant ES cells from mouse embryos.

M.R.-T. and C.S. were recipients of Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación and Comunidad de Madrid fellowships, respectively. This work was supported by grants SAF2007-65957-C02-01 and BFU2010-18146 (Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación) and by the Fundación Ramón Areces (M.V.)

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 23 January 2012

REFERENCES

- 1.Arrigoni R, et al. 2006. The Polycomb-associated protein Rybp is a ubiquitin binding protein. FEBS Lett. 580:6233–6241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bejarano F, González I, Vidal M, Busturia A. 2005. The Drosophila RYBP gene functions as a Polycomb-dependent transcriptional repressor. Mech. Dev. 122:1118–1129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernstein E, et al. 2006. Mouse polycomb proteins bind differentially to methylated histone H3 and RNA and are enriched in facultative heterochromatin. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26:2560–2569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borgel J, et al. 2010. Targets and dynamics of promoter DNA methylation during early mouse development. Nat. Genet. 42:1093–1100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyer LA, et al. 2006. Polycomb complexes repress developmental regulators in murine embryonic stem cells. Nature 441:349–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown JL, Mucci D, Whiteley M, Dirksen ML, Kassis JA. 1998. The Drosophila Polycomb group gene pleiohomeotic encodes a DNA binding protein with homology to the transcription factor YY1. Mol. Cell 1:1057–1064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown JL, Fritsch C, Mueller J, Kassis JA. 2003. The Drosophila pho-like gene encodes a YY1-related DNA binding protein that is redundant with pleiohomeotic in homeotic gene silencing. Development 130:285–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cao R, Zhang Y. 2004. The functions of E(Z)/EZH2-mediated methylation of lysine 27 in histone H3. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 14:155–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chamberlain SJ, Yee D, Magnuson T. 2008. Polycomb repressive complex 2 is dispensable for maintenance of embryonic stem cell pluripotency. Stem Cells 26:1496–1505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christophersen NS, Helin K. 2010. Epigenetic control of embryonic stem cell fate. J. Exp. Med. 207:2287–2295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Napoles M, et al. 2004. Polycomb group proteins Ring1A/B link ubiquitylation of histone H2A to heritable gene silencing and X inactivation. Dev. Cell 7:663–676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Endoh M, et al. 2008. Polycomb group proteins Ring1A/B are functionally linked to the core transcriptional regulatory circuitry to maintain ES cell identity. Development 135:1513–1524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fouse SD, et al. 2008. Promoter CpG methylation contributes to ES cell gene regulation in parallel with Oct4/Nanog, PcG complex, and histone H3 K4/K27 trimethylation. Cell Stem Cell 2:160–169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.García E, Marcos-Gutiérrez C, del Mar Lorente M, Moreno JC, Vidal M. 1999. RYBP, a new repressor protein that interacts with components of the mammalian Polycomb complex, and with the transcription factor YY1. EMBO J. 18:3404–3418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garcia-Tuñon I, et al. 2011. Association of Rex-1 to target genes supports its interaction with Polycomb function. Stem Cell Res. 7:1–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gearhart MD, Corcoran CM, Wamstad JA, Bardwell VJ. 2006. Polycomb group and SCF ubiquitin ligases are found in a novel BCOR complex that is recruited to BCL6 targets. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26:6880–6889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hansen K, et al. 2008. A model for transmission of the H3K27me3 epigenetic mark. Nat. Cell Biol. 10:1291–1300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He K, Zhao H, Wang Q, Pan Y. 2010. A comparative genome analysis of gene expression reveals different regulatory mechanisms between mouse and human embryo pre-implantation development. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 8:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hutnick LK, Huang X, Loo T-C, Ma Z, Fan G. 2010. Repression of retrotransposal elements in mouse embryonic stem cells is primarily mediated by a DNA methylation-independent mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 285:21082–21091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joo H-Y, et al. 2007. Regulation of cell cycle progression and gene expression by H2A deubiquitination. Nature 449:1068–1072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karimi MM, et al. 2011. DNA methylation and SETDB1/H3K9me3 regulate predominantly distinct sets of genes, retroelements, and chimeric transcripts in mESCs. Cell Stem Cell 8:676–687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ku M, et al. 2008. Genomewide analysis of PRC1 and PRC2 occupancy identifies two classes of bivalent domains. PLoS Genet. 4:e1000242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee MG, et al. 2007. Demethylation of H3K27 regulates polycomb recruitment and H2A ubiquitination. Science 318:447–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee TI, et al. 2006. Control of developmental regulators by Polycomb in human embryonic stem cells. Cell 125:301–313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leeb M, et al. 2010. Polycomb complexes act redundantly to repress genomic repeats and genes. Genes Dev. 24:265–276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leeb M, Wutz A. 2007. Ring1B is crucial for the regulation of developmental control genes and PRC1 proteins but not X inactivation in embryonic cells. J. Cell Biol. 178:219–229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levine SS, et al. 2002. The core of the polycomb repressive complex is compositionally and functionally conserved in flies and humans. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:6070–6078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Macfarlan TS, et al. 2011. Endogenous retroviruses and neighboring genes are coordinately repressed by LSD1/KDM1A. Genes Dev. 25:594–607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Margueron R, et al. 2009. Role of the polycomb protein EED in the propagation of repressive histone marks. Nature 461:762–767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Margueron R, Reinberg D. 2011. The Polycomb complex PRC2 and its mark in life. Nature 469:343–349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsui T, et al. 2010. Proviral silencing in embryonic stem cells requires the histone methyltransferase ESET. Nature 464:927–932 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meissner A, et al. 2008. Genome-scale DNA methylation maps of pluripotent and differentiated cells. Nature 454:766–771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mendenhall EM, et al. 2010. GC-rich sequence elements recruit PRC2 in mammalian ES cells. PLoS Genet. 6:e1001244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mohn F, et al. 2008. Lineage-specific Polycomb targets and de novo DNA methylation define restriction and potential of neuronal progenitors. Mol. Cell 30:755–766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morgan HD, Santos F, Green K, Dean W, Reik W. 2005. Epigenetic reprogramming in mammals. Hum. Mol. Genet. 14(Spec. No. 1):R47–R58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murry CE, Keller G. 2008. Differentiation of embryonic stem cells to clinically relevant populations: lessons from embryonic development. Cell 132:661–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neira J, et al. 2009. The transcriptional repressor RYBP is a natively unfolded protein which folds upon binding to DNA. Biochemistry 48:1348–1360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oda M, et al. 2006. DNA methylation regulates long-range gene silencing of an X-linked homeobox gene cluster in a lineage-specific manner. Genes Dev. 20:3382–3394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pasini D, Bracken AP, Hansen JB, Capillo M, Helin K. 2007. The polycomb group protein Suz12 is required for embryonic stem cell differentiation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 27:3769–3779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peaston AE, et al. 2004. Retrotransposons regulate host genes in mouse oocytes and preimplantation embryos. Dev. Cell 7:597–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pirity MK, Locker J, Schreiber-Agus N. 2005. Rybp/DEDAF is required for early postimplantation and for central nervous system development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25:7193–7202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Popp C, et al. 2010. Genome-wide erasure of DNA methylation in mouse primordial germ cells is affected by AID deficiency. Nature 463:1101–1105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Puschendorf M, et al. 2008. PRC1 and Suv39h specify parental asymmetry at constitutive heterochromatin in early mouse embryos. Nat. Genet. 40:411–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rossant J. 2008. Stem cells and early lineage development. Cell 132:527–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rowe HM, et al. 2010. KAP1 controls endogenous retroviruses in embryonic stem cells. Nature 463:237–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rowe HM, Trono D. 2011. Dynamic control of endogenous retroviruses during development. Virology 411:273–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sánchez C, et al. 2007. Proteomics analysis of Ring1B/Rnf2 interactors identifies a novel complex with the Fbxl10/Jhdm1B histone demethylase and the Bcl6 interacting corepressor. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 6:820–834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sawa C, et al. 2002. YEAF1/RYBP and YAF-2 are functionally distinct members of a cofactor family for the YY1 and E4TF1/hGABP transcription factors. J. Biol. Chem. 277:22484–22490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schwartz YB, Pirrotta V. 2008. Polycomb complexes and epigenetic states. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 20:266–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sharif J, et al. 2007. The SRA protein Np95 mediates epigenetic inheritance by recruiting Dnmt1 to methylated DNA. Nature 450:908–912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Simon J, Kingston R. 2009. Mechanisms of Polycomb gene silencing: knowns and unknowns. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10:697–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stanton SE, McReynolds LJ, Evans T, Schreiber-Agus N. 2006. Yaf2 inhibits caspase 8-mediated apoptosis and regulates cell survival during zebrafish embryogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 281:28782–28793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stock J, et al. 2007. Ring1-mediated ubiquitination of H2A restrains poised RNA polymerase II at bivalent genes in mouse ES cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 9:1428–1435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Trimarchi JM, Fairchild B, Wen J, Lees JA. 2001. The E2F6 transcription factor is a component of the mammalian Bmi1-containing polycomb complex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:1519–1524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tsumura A, et al. 2006. Maintenance of self-renewal ability of mouse embryonic stem cells in the absence of DNA methyltransferases Dnmt1, Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b. Genes Cells 11:805–814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.van Bakel H, et al. 2008. Improved genome-wide localization by ChIP-chip using double-round T7 RNA polymerase-based amplification. Nucleic Acids Res. 36:e21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van den Berg DLC, et al. 2010. An Oct4-centered protein interaction network in embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 6:369–381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vastenhouw NL, et al. 2010. Chromatin signature of embryonic pluripotency is established during genome activation. Nature 464:922–926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang H, et al. 2004. Role of histone H2A ubiquitination in Polycomb silencing. Nature 431:873–878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang J, et al. 2006. A protein interaction network for pluripotency of embryonic stem cells. Nature 444:364–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang R, et al. 2010. Polycomb group targeting through different binding partners of RING1B C-terminal domain. Structure 18:966–975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wilkinson F, Pratt H, Atchison ML. 2010. PcG recruitment by the YY1 REPO domain can be mediated by Yaf2. J. Cell. Biochem. 109:478–486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Woo CJ, Kharchenko PV, Daheron L, Park PJ, Kingston RE. 2010. A region of the human HOXD cluster that confers polycomb-group responsiveness. Cell 140:99–110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Young RA. 2011. Control of the embryonic stem cell state. Cell 144:940–954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material