Remarkably similar antigen receptors among a subset of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (original) (raw)

Abstract

Studies of B cell antigen receptors (BCRs) expressed by leukemic lymphocytes from patients with B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL) suggest that B lymphocytes with some level of BCR structural restriction become transformed. While analyzing rearranged VHDJH and VLJL genes of 25 non–IgM-producing B-CLL cases, we found five IgG+ cases that display strikingly similar BCRs (use of the same H- and L-chain V gene segments with unique, shared heavy chain third complementarity-determining region [HCDR3] and light chain third complementarity-determining region [LCDR3] motifs). These H- and L-chain characteristics were not identified in other B-CLL cases or in normal B lymphocytes whose sequences are available in the public databases. Three-dimensional modeling studies suggest that these BCRs could bind the same antigenic epitope. The structural features of the B-CLL BCRs resemble those of mAb’s reactive with carbohydrate determinants of bacterial capsules or viral coats and with certain autoantigens. These findings suggest that the B lymphocytes that gave rise to these IgG+ B-CLL cells were selected for this unique BCR structure. This selection could have occurred because the precursors of the B-CLL cells were chosen for their antigen-binding capabilities by antigen(s) of restricted nature and structure, or because the precursors derived from a B cell subpopulation with limited BCR heterogeneity, or both.

Introduction

B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL), a monoclonal expansion of mature CD5-expressing B lymphocytes, is a heterogeneous disease that affects primarily individuals over 50 years of age (1). Even though B-CLL is the most common leukemia in the Western hemisphere (2), the events that select out an individual normal B cell clone and usher it toward leukemic transformation remain unknown. Genetic abnormalities probably exist in these cells and represent important inducers; however, no single unifying molecular genetic defect or combination of defects has yet been identified (3).

Studies of the characteristics of the B cell antigen receptors (BCRs) expressed by B-CLL cells imply that precursor B lymphocyte clones that eventually become leukemic exhibit varying degrees of BCR structural similarity (4). This restriction in BCR structure suggests that either the precursors of the leukemic B lymphocytes were selected by specific antigens that have affinity for these BCRs, or they were garnered from a B cell subpopulation with restricted BCR structural heterogeneity.

In the present study, we analyzed the rearranged VHDJH and VLJL genes of a cohort of 25 B-CLL patients whose leukemic cells express isotype-switched Ig. Our results reveal that a substantial subset of IgG+ cases (∼20%) display strikingly similar Ig V region gene features. These include the use of the same H- and L-chain V gene segments, which are combined in unique ways and exhibit little somatic diversification despite their Ig class–switched nature. These findings are compelling evidence that selection of a specific BCR structure is an important component promoting the development of B-CLL. Preliminary abbreviated reports of these findings have appeared previously (5, 6).

Methods

CLL patients and samples.

The Institutional Review Board of North Shore University Hospital (Manhasset, New York) and Long Island Jewish Medical Center (New Hyde Park, New York) approved these studies. From a cohort of 237 patients with clinical and laboratory features of B-CLL, 25 patients with expansions of CD5+/CD19+ B cells expressing surface membrane IgG or IgA were chosen and analyzed. All of the patients with surface membrane IgM+ cells were obtained randomly; some of the IgG+ cases were provided by others because of their surface membrane phenotype and therefore were not randomly acquired. Some patients and the V gene sequences of their leukemic cells were described previously (5–9). PBMCs from these patients, obtained from heparinized blood by density gradient centrifugation (Ficoll-Paque; Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, New Jersey, USA), were used after thawing samples that had been cryopreserved with a programmable cell-freezing machine (CryoMed, Inc., Mt. Clemens, Michigan, USA).

Isolation of DNA.

T lymphocytes were purified from PBMCs by negative selection using the Pan T cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, California, USA), and DNA was isolated from these cells with the DNeasy Tissue Kit (QIAGEN Inc., Valencia, California, USA).

Preparation of RNA and synthesis of cDNA.

Total RNA was isolated from PBMCs using Ultraspec RNA (Biotecx Laboratories Inc., Houston, Texas, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA (1 μg) was reverse-transcribed to cDNA using 200 U of Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, California, USA), 1 U of RNase inhibitor (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany), and 20 pmol of oligo dT primer (total volume of 20 μl). These reactants were incubated at 42°C for 1 hour, heated at 65°C for 10 minutes to stop the reactions, and then diluted to a final volume of 100 μl.

PCR conditions for IgV gene DNA sequencing.

To determine the IgVH gene family used by various B-CLL cells, cDNA (2 μl) was amplified using sense framework region 1 (FR1) primers specific for the various IgVH gene families in conjunction with an appropriate antisense IgCH primer (10). Reactions were carried out in 50 μl using 20 pmol of each primer and cycled with a 9600 GeneAmp System (Perkin-Elmer Cetus, Emeryville, California, USA).

The DNA sequence of the B-CLL IgVH gene was determined by re-amplifying the original cDNA (2 μl) using the appropriate IgVH family leader and IgCH primers defined above (10). PCR products were sequenced directly after purification with Wizard PCR Preps (Promega Corp., Madison, Wisconsin, USA) using an automated sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California, USA). In some instances where mutations were detected, an independent PCR product was generated and either sequenced directly or cloned into TA vector (Invitrogen Corp.), processed using Wizard minipreps (Promega Corp.), and then sequenced using M13 forward and reverse primers.

To determine IgVL gene sequences, cDNA (2 μl) was amplified using the leader primers listed in Supplemental Table 1 (supplemental material available at http://www.jci.org/cgi/content/full/113/7/1008/DC1). For the Vλ families I, III, and IV, a mixture of primers was used. To amplify Vλ families II and X, both forward primers were used in a common reaction, since they cross-prime. Reactions were carried out in a 50-μl volume using 20 pmol of each primer, 200 μM dNTPs, 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 1.25 U of Taq Gold (Perkin-Elmer), and cycled with a 9600 GeneAmp System as follows: denaturation at 94°C for 45 seconds, annealing at 62°C for 30 seconds, and extension at 72°C for 45 seconds. After 35 cycles, extension was continued at 72°C for an additional 10 minutes. IgVL PCR products were sequenced in the same manner as IgVH PCR products.

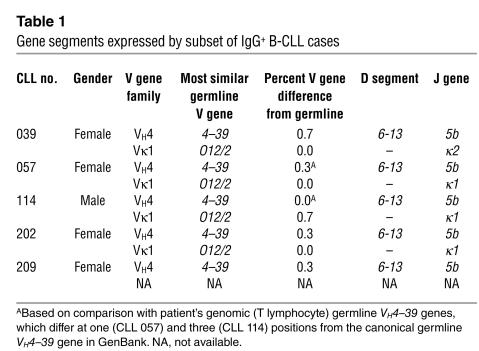

Table 1.

Gene segments expressed by subset of IgG+ B-CLL cases

To identify potential polymorphisms in the germline VH4–39 gene, PCR was performed on DNA from autologous T cells of two patients (nos. 057 and 114) using VH4–39 CDR2-specific gene primers (forward: 5′-GGTGGCGGCTCCCAGATG-3′; reverse: 5′-TCACACTCACCTCCCCTCAC-3′). PCR products were cloned and sequenced using the TOPO TA cloning kit (Invitrogen Corp.).

Analyses of VH, D, and JH sequences.

DNA sequences were compared with those in the V BASE sequence directory (11) using MacVector software, version 6.0 (Accelrys, San Diego, California, USA) as previously described (8). Amino acid sequences were compared with those in GenBank by means of a BLAST search using the tblastn algorithm.

Analyses of heavy chain complementarity region 3 and light chain complementarity region 3 rearrangements.

Heavy chain third complementarity-determining region (HCDR3) length was determined according to Kabat and Wu (12) by counting the number of amino acids between position H94 at the 3′ end of FR3 (usually two amino acids downstream of the conserved cysteine) and position H102 at the beginning of FR4 (a conserved tryptophan in all JH segments). Light chain third complementarity-determining region (LCDR3) length was determined by counting amino acids beginning at position L89 (preceded by a conserved cysteine) to position L97 (followed by a conserved Phe-Gly pair). Hypervariable loops were defined according to Chothia and Lesk (13); in particular, the third hypervariable loop of the H chain (H3) spans the amino acids 92–104, in the Kabat et al. numbering scheme (14).

Antibody modeling.

Three-dimensional models of the V domains of the Ig’s were constructed using the canonical structure model (14) as implemented in the web antibody modeling (WAM) algorithm (15). Models were analyzed using the molecular graphics package Insight II (16).

Results

Identification of five IgG-expressing B-CLL cases with remarkably similar BCR.

While determining cDNA sequences of VHDJH and VLJL rearrangements expressed in 25 isotype-switched B-CLL samples (23 IgG+ and 2 IgA+, see Supplemental Table 2), we identified five IgG-expressing cases with remarkably similar BCRs. These cases (CLL nos. 039, 057, 114, 202, and 209) expressed the same VH [4–39], D [6–13], and JH (5b) gene segments (Table 1). For the four cases in which L-chain data were obtained (additional sample on CLL no. 209 was not available because the patient died in an automobile accident), all used the VκO12/2 gene (Table 1). In cases 057, 114, and 202, this VL gene recombined with the Jκ1 gene segment; in case no. 039, the VκO12/2 gene was associated with Jκ2. However, the expressed L chains of these four cases, including CLL no. 039, were virtually identical at the amino acid level (see below).

These five patients had several clinical similarities. The subset comprised primarily women with a 1:4 male/female ratio (Table 1), which differs from that in the other isotype-switched cases in this cohort (14:6; see Supplemental Table 2) and in B-CLL cases in general (∼2:1 [refs. 1, 2]). Moreover, the patients experienced aggressive clinical courses complicated by severe recurrent infections (no. 039), Richter’s transformation (no. 057), or the occurrence of second solid tumors (nos. 114 and 202). There was no familial or consistent ethnic relationship among these cases, and the patients originated from different parts of the world (two from the United States, one from Italy, one from the Caribbean region, and one from Japan).

The majority of the other 20 isotype-switched cases used either a VH3 family gene (50%) or a VH4 family gene (35%; see Supplemental Table 2). All of these VH4-expressing cases used the VH4–34 gene. One case (CLL no. 097) used the VLO12/2 gene, although this Vκ gene was mutated and was paired with a mutated VH3–73 gene. Thirteen of the remaining 20 cases expressed Vκ, and six expressed Vλ genes, with no apparent VL segment biases. All of the Vγ-expressing cases used a VH3 gene; among these, only Jλ2 was used.

Ig V gene mutation status.

Although the leukemic cells of these five cases synthesized IgG, their VH and VL genes showed minimal deviation from the germline gene sequence (VH: 0.3–0.7%, and VL 0.0–0.7%; Table 1). In contrast, among the other 20 isotype-switched patients, only four (nos. 040, 097, 158, and 185) expressed both VH and VL genes that differed by 1.0% or less from the germline counterparts (Supplemental Table 2).

To determine if some of these nucleotide differences represented allelic polymorphisms, we sequenced the VH segments from the genomic (T cell) DNA of two patients (nos. 057 and 114; see Supplemental Figure 3). The germline VH4–39 gene sequence for patient no. 057 exhibited one difference from the canonical germline VH4–39 deposited in GenBank, and the germline gene of patient 114 differed at three positions from the GenBank sequence. These findings indicate that some of the nucleotide differences we detected were allelic polymorphisms (Supplemental Figure 3), whereas others were real somatic mutations. A recent communication suggests that most of the Ig VH sequence differences detected in “unmutated” B-CLL cells are somatically attained (17). A lack of somatic mutations in VH4–39 genes from patients with predominantly IgM+ B-CLL has been reported previously (8, 18). Supplemental Figure 1, A and B, compares the VH and VL genes of the leukemic cells with the GenBank germline counterpart.

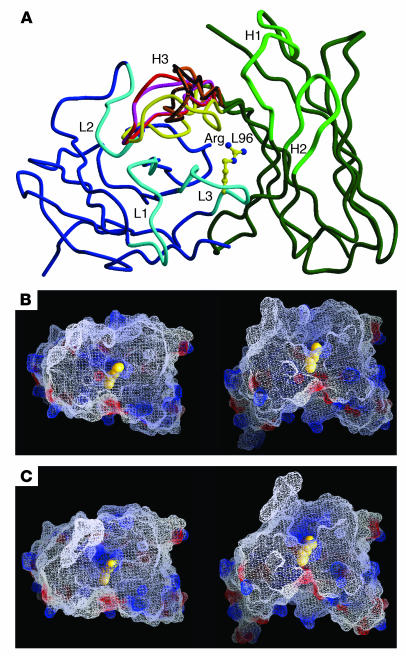

Figure 3.

C-alpha trace of the structural models produced by WAM. (A) Overlay of main chains of the five CLL three-dimensional structures. For CLL no. 209, the consensus L-chain amino acid sequence was added for WAM analysis. B-CLL L chains are shown in blue color (hypervariable loops L1, L2, and L3 in light blue), and H chains are shown in green color (hypervariable loops H1, and H2 in light green). The different H3 loop structures are color-coded, as noted by the lime green, red, black, purple, and dark green lines in the H3 area. Figure was prepared with MOLSCRIPT (91), and Raster3D (92). (B and C) Electrostatic and molecular surface representation of the structure of CLL no. 039 as a model representative of the B-CLL cases of nonbulged conformation (nos. 039 and 114; B) and of the CLL no. 057 as a model of the cases of bulged conformation (nos. 057, 202, and 209; C). Negative surface potentials are indicated in red, positive surface potentials in blue, and neutral potentials in white. The arginine L96 side chain is shown in yellow CPK representation. The structures are shown from a top view (left panels) and from a side view, corresponding to an approximately 70° rotation relative to the top view (right panels). Figures were prepared with GRASP (93). Arg L96; arginine L96 side chain.

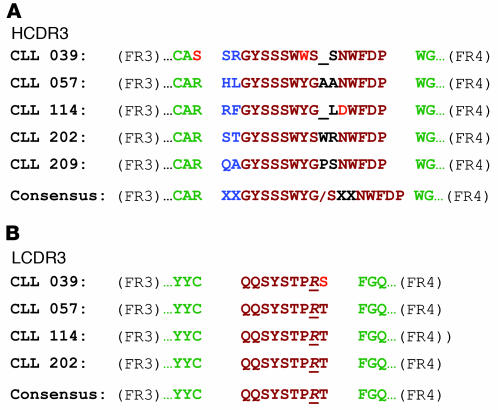

Figure 1.

Amino acid sequences of HCDR3 and LCDR3 of IgG+ B-CLL cases. Amino acid sequences are shown flanked by the 3′ end of FR3 and the 5′ end of FR4. A consensus sequence is shown for each. Color code: identical amino acids are in brown, chemically similar amino acids in blue, unrelated amino acids in black, and differences within areas of identity or similarity in red. (A) HCDR3. The consensus sequence consists of two hydrophilic amino acids (blue), seven amino acids that represent a portion of the germline D6–13 gene segment (brown), a glycine or serine (both with small side chains; brown), one to two variable amino acids, and five amino acids from the 5′ portion of the germline JH5b segment. (B) LCDR3. The LCDR3 sequences of all cases are identical, except for a difference in the last amino acid in CLL no. 039, due to the use of the Jκ2 segment. In each case, an arginine occurs at the Vκ-Jκ junction (underlined and in italics).

Protein sequences of IgVH and IgVL.

Since most of the nucleotide differences in VH and VL were silent, the deduced VH and VL protein sequences of the five IgG+ cases were virtually identical to that predicted from their germline genes (Supplemental Figure 2, A and B). For VH, there were only two amino acid changes among the five cases. CLL no. 057 exhibited a Pro → Thr change at position H63, and no. 039 displayed an Arg → Ser change at position H96; these isolated changes occurred in FR3. The VL protein sequences were also virtually identical; only CLL no. 114 showed a Gln → Arg change at position L3 in FR1.

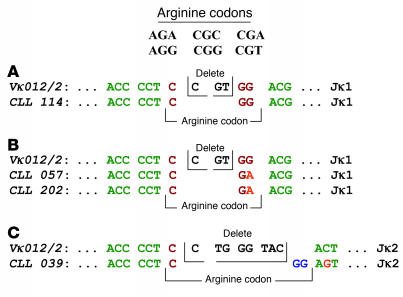

Figure 2.

Different mechanisms generate an arginine at the VL-JL junctions. The codons for arginine are listed. Color code: identical nucleotides of the arginine codon are in brown, nucleotides deleted are in black, nucleotides probably resulting from nontemplated nucleotide addition are in dark blue, and differences within areas of identity or similarity in red. (A and B) An appropriate codon results from coding end trimming and recombination of the two germline Vκ and Jκ1 segments. (C) The arginine codon develops via a more complex combinatorial process, requiring the trimming of one nucleotide from the 3′ end of VL, the deletion of seven nucleotides from the 5′ end of Jκ2, and the nontemplated insertion of two G nucleotides.

HCDR3 structure.

Figure 1A aligns the HCDR3 protein sequences for these five IgG-expressing cases. HCDR3 lengths were very similar (16–17 amino acids). These lengths are longer than most normal B cells (19) and many B-CLL cells (8, 20). The HCDR3 sequences of the five cases were very similar, exhibiting a consensus sequence (XXGYSSSWYG/SX(X)NWFDP; Figure 1A) consisting of two N-terminal hydrophilic amino acids, seven invariant amino acids that represent a portion of the D6–13 gene segment read in the hydrophilic reading frame, a glycine or serine that are similar in their small side chains, one to two variable amino acid(s) that lack chemical similarity, and five amino acids corresponding to the 5′ portion of the JH5b segment.

LCDR3 structure.

The LCDR3 sequences of all cases were identical (Figure 1B), except for a difference in the last amino acid in CLL no. 039; this difference results from the use of the Jκ2 segment in this instance. In each case, an arginine (R) was located at the Vκ-Jκ junction (position L96). In CLL no. 114 (Figure 2A), CGG, one of the six possibilities that code for arginine, resulted from coding end trimming and recombination of the Vκ and Jκ germline segments. For cases no. 057 and 202 (Figure 2B), the codon CGA yielded the arginine via a process similar to that for CLL no. 114. However, for CLL no. 039, which used the Jκ2 gene segment (Figure 2C), the combinatorial process that led to the arginine at the Vκ-Jκ junction was more complex. This required the trimming of one nucleotide from the 3′ end of VL and the deletion of seven nucleotides from the 5′ end of Jκ2, along with the nontemplated insertion of two G nucleotides, to generate an arginine codon (CGG).

Lack of similar rearranged Ig V genes in other human B cells.

We searched GenBank for VHDJH rearrangements with significant amino acid similarity to the consensus protein sequences of these five B-CLL cases. Only one very similar rearrangement was found, and this was from a lymphoplasmacytoid immunocytoma (GenBank entry no. Y09249 [ref. 21]); however, the corresponding L chain in this case was of the λ isotype (GenBank entry no. Y09250 [ref. 22]).

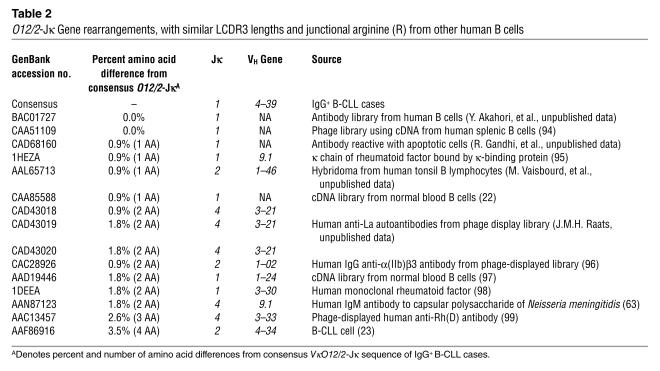

We also searched for rearranged _VκO12/2_-Jκ L chains of the same LCDR3 length that have an arginine at the VL-JL junction. Because the V region of an L chain comprises only two gene segments and because six codons can yield an arginine, the likelihood of identifying rearrangements with similar structure is higher than that for a rearranged VHDJH. BLAST search revealed 15 close matches (100% to 96.5% similarity) to the _VκO12/2_-Jκ consensus amino acid sequence of the five IgG+ B-CLL cases (Table 2). For 11 of these 15 cases, the companion VHDJH segments were available; none of these was VH4–39. Of the _VκO12/2_-Jκ cases with known companion VHDJH segments, eight were of defined antigen specificity. Remarkably, of these eight cases, seven were from autoreactive mAb’s (anti-IgG, anti-RhD, anti-La, anti-αIIbβ3 integrin, and antiapoptotic cells); the other bound the capsular polysaccharide of Neisseria meningitidis (Table 2). One of the _VκO12/2_-Jκ rearrangements of unknown specificity was from a B-CLL clone (GenBank entry no. AF228327); however, this was paired with a VH4–34 gene (GenBank entry no. AF196469 [ref. 23]).

Table 2.

_O12/2_-Jκ Gene rearrangements, with similar LCDR3 lengths and junctional arginine (R) from other human B cells

We next searched the Kabat, et al. database (14) and identified 2,950 mAb’s for which both H and L Ig V genes were known. Among these, we found 199 with an arginine at L96. There was no statistically significant correlation between the presence of an arginine at the VL-JL junction and a specific, unique antigenic reactivity. However, there was a striking enrichment (102/199) for antibodies that react with structures that serve as autoantigens in several autoimmune settings; examples are double-stranded (ds) and single-stranded (ss) DNA, IgG, and thyroid constituents. This was consistent with the autoreactivity identified in the _VκO12/2_-Jκ VL-JL listed in Table 2.

Three-dimensional models of the B-CLL BCR.

We used the canonical structure method (13) as implemented in the WAM algorithm to build models for the V domains, and then analyzed these structures to deduce characteristics of the antigen-binding sites (Figure 3). The canonical structure model requires that the main chain conformation of the hypervariable loops depend solely on length and on the nature of a few specific residues. Antibody specificity is therefore determined by the nature of exposed side chains mounted on the main chain of the hypervariable loops, which in turn is determined by their canonical structure.

In the four available B-CLL L chains (case nos. 039, 057, 114, and 202), the L1 loop is six residues long and contains a conserved isoleucine at position 29. In all known antibody structures, six-residue L1 loops are stabilized by contact of the side chain of this amino acid with residues 2, 25, 33, and 71 (13). These contacts determine the main chain structure of the loop. Each of these five residues is hydrophobic and conserved in the four B-CLL rearranged L chains. Since the exposed amino acids of the loop are also conserved, the contribution of this loop to the antigen-binding site would be virtually identical for all four antibodies. The L2 loop has the same conformation in all known V region structures (13). Since there are no substitutions in the exposed side chains of these cases, the contribution of this loop to the binding site is expected to be the same for all the proteins. Similarly, since the backbone structure of the L3 loop depends on its length and the nature of the residues at positions 90 and 95, which are all identical in the B-CLL sequences, this loop should have the same conformation and solvent-exposed surface in all four cases.

The H1 loop has a conserved hydrophobic residue in position 29 and a conserved glycine in position 26. The former establishes stabilizing interactions with residues 34, 72, and 77. Each of these five residues is conserved among the VH sequences of the five B-CLL cases. Consistent with these observations, the WAM prediction server produces identical models in this region for the five antibodies. The H2 conformation has been shown to depend only on its length and on the residue at position 71 (24); both of these features are conserved in the five B-CLL sequences.

One cannot infer as clear a sequence–structure relationship for H3, since this loop is the most variable in length and sequence. The conformation of H3 is mainly determined by the presence or absence of a β bulge within its structure, in the region closer to the FR. The presence of a β bulge is in turn determined by the amino acid sequence of the loop (25). Based on our modeling analyses, the H3 loop is predicted not to be bulged in CLL nos. 039 and 114 and bulged at residue H101 in CLL nos. 057, 202, and 209. The creation of the bulge in the latter cases implies that residue H101m of the nonbulged loops is in a position equivalent to that of residue H101 of the bulged loops. Thus, the tip of the loop probably contains the same number of residues (n = 14) in all cases, and the residues in the bulged cases can maintain a relationship in space similar to that of the non-bulged cases.

Discussion

In this study we describe five IgG-expressing B-CLL cases with remarkably similar BCRs. These receptors consist of the same VH, D, JH, and VL, JL gene segments, except for a different Jκ segment in one instance. Despite this difference, all BCRs have identical LCDR3s and very similar HCDR3s, each with unique sequence and junctional motifs. This BCR restriction could be the consequence of either random transformation of a subpopulation of B cells with very limited antigen receptor heterogeneity — determined genetically or by antigen selection; or specific transformation of B cells that were selected by antigen from a BCR-restricted or BCR-heterogeneous subpopulation; or both. Whatever the cause, our findings support the concept that B-CLL develops from a limited set of B lymphocytes of defined BCR structure and imply that selection of B cells with such structures represents an important promoting influence in the evolution of the leukemic cells.

Composition, motifs, and three-dimensional structure models.

Developing B lymphocytes do not use all germline IgV gene segments with the same frequency, and biases in gene segment rearrangement do occur (26–29). Nevertheless, considering combinatorial diversity, imprecise joining, nucleotide insertion and deletion, and somatic hypermutation, the probability of finding selectively in one disease, by chance alone, five cell clones with such highly similar rearranged H- and L-chain V region pairs is extremely low. The probability that specific VH, D, and JH genes would be used in the same VHDJH rearrangement is 1 in 7,128 (1/44 × 1/27 × 1/6); for a specific VL and JL gene pair the probability is 1/230 (1/46 × 1/5) or 1/252 (1/36 × 1/7) for a κ versus a λ rearrangement, respectively. Only 1 in 1,639,440 B cells would be predicted to randomly express the same VH, D, JH, Vκ, and Jκ segments in its BCR. These calculations use the number of germline V segments in IgBLAST and assume that κ genes rearrange before λ genes.

Considering these estimations, the frequency at which this BCR occurs in our IgG+ B-CLL cases is extraordinary (∼20%). Although this percentage will need confirmation, the frequency of such unique IgG+ cases is very similar to that identified when we first reported on Ig V gene diversification and apparent antigen selection in a smaller number of isotype-switched B-CLL cases (7). This structure was not seen in our IgM+ B-CLL cohort (>175 cases for which both the rearranged VHDJH and VLJL are known) or in GenBank, indicating that this BCR is not overexpressed among IgM+ B-CLL cases or in the normal circulating B cell repertoire. We cannot rule out that its frequency increases with age or that it exists among certain distinct noncirculating subpopulations of B cells, although a recent study suggests that the former may be unlikely (30).

Notwithstanding the present limitations of antibody modeling, primarily with respect to the H3 loop, we can reliably conclude that most of the binding site is identical among these IgG+ B-CLL cases. Five of the six H and L loops have the same main chain conformation and differ, in only one case, by a conservative Ser → Thr side chain change at position 97 of the L chain. However, this residue does not contact antigen in any known structure (Veronica Morea, personal communication). The H3 loops are also quite similar among the five antibodies, although three are longer by one residue (Figure 1). Since these loops contain a bulge (i.e., they have one residue that is extruded from the regular β structure), the residues at the central region of the loop, which are more relevant for antigen binding, can maintain the same relationship in space in all five cases. Therefore, the antigen-binding surfaces of these antibodies are probably very similar, and they likely bind the same antigenic epitope. Nevertheless since some amino acid differences do exist at the VH-D and D-JH junctions, this remains conjecture.

Restricted IgV gene structural features of antibodies with defined antigenic reactivities.

Normal and neoplastic B cells of known antigen specificity can display restricted V (D), J segment use, either at both H and L chain loci or individually at either locus. Murine mAb’s reactive with β-(1, 6)-D-galactan (31), α(1 → 6) dextran (32, 33), phosphorylcholine (34), dextrans and fructofurans (35), and phosphatidylcholine (36–38) pair very restricted and characteristic VHDJH and VLJL gene segments. Human antibodies that exhibit individual H- or L-chain restrictions include mAb’s specific for the capsular polysaccharides of Haemophilus influenzae type b (39–41) and Streptococcus pneumoniae (42, 43) (individual VH3 genes for both), monoclonal cold agglutinins with anti-I specificity (exclusively VH4–34 [refs. 44–46]), and monoclonal rheumatoid factors with IgG reactivity (VH1–69 [refs. 47–51]). Murine anti-arsonate (52–54) and anti–bacterial polysaccharide mAb’s (55) frequently use specific individual Vκ and Jκ genes.

In addition, mAb’s reactive with carbohydrates (30, 32, 40, 56), autoantigens (57, 58), and haptens (52–54) often have characteristic VL-JL junctional residues. Human anti–H. influenzae mAb’s that use the VκA2 gene segment contain an arginine at position L96, although chain recombination experiments suggest that it is not essential for antigen binding (40, 56). Murine mAb’s reactive with arsonate (Ars), dsDNA, and β-(1, 6)-D-galactan exhibit an arginine or an isoleucine at position L96, respectively. These junctional amino acids are essential for binding to Ars (53), but not to β-(1, 6)-D-galactan (59).

Nature of the antigen that could have selected these BCRs.

Our findings suggest that the B lymphocytes that gave rise to these IgG+ B-CLL cells were selected for a unique BCR structure. If this selection involved antigen binding and triggering through the BCR, the antigen(s) would most likely have been of restricted nature and structure. Although the identity of such an antigen is unknown, we can infer certain features based on our data.

First, the diverse geographic origins of our patients suggests that the putative structure would probably be distributed worldwide. Second, the epitope would appear to select out and drive B cells to undergo an isotype class switch, since we found this BCR only in non-IgM-expressing B-CLL cells. Third, this selection and drive would not frequently lead to clonal expansion of normal B cells, since we could not identify this BCR in B lymphocytes from normal individuals deposited in GenBank. Fourth, the presence of a positively charged center to the antigen-binding pocket, provided by the side chain of arginine L96, and surrounded by an aromatic area and a ridge of polar residues, would imply that a negatively charged or electron-rich group exists in the epitope interactive with these BCRs (Figure 3). This, however, is not a necessity (41, 53, 59). Of the 199 completely sequenced antibodies with an arginine at L96 (14), we found that about 50% react with autoantigens. This is consistent with the association with autoreactivity in the _VκO12/2_-Jκ rearrangements listed in Table 2. Autoantigens can be negatively charged molecules (e.g., DNA), and their reactivity with positively charged residues in the CDRs of autoantibodies is enhanced as the number of these latter residues increases (58, 60). Finally, in light of the comparisons with antibodies of known specificities, the epitope could be a carbohydrate that is restricted to a unique molecule or shared by several molecules, an autoantigen that is shared by all individuals or polymorphic among populations, or a carbohydrate determinant of an autoantigen. The possibility that two classes of antigens can bind to the same binding site also should not be ruled out (61).

It is of interest that several relationships exist between carbohydrate reactivity and autoreactivity. Autoantibodies can react with carbohydrates (62–65) and can confer protection against infection with encapsulated bacteria (66, 67). In addition, antipneumococcal polysaccharide antibodies can convert to anti-dsDNA reactivity after minimal amino acid changes in the Ig V region (68). In this regard, it is known that the BCRs of B-CLL clones can be autoreactive (69, 70) and can express cross-reactive idiotypes of dsDNA antibodies (71).

Importance of B cell precursors with constrained BCR structural diversity in the development and progression of B-CLL.

Irrespective of the nature of the antigen(s) possibly involved in these cases, these five IgG+ clones are extraordinary examples of the principle that B-CLL progenitors are selected for certain limited BCR structures (4). Similar evidence for BCR restriction, possibly attained by antigen or superantigen selection, can be found among the IgM-expressing cases that use a VH3–21 gene with a restricted Vλ partner (72, 73), and probably in those cases that use an unmutated VH1–69 gene with a characteristic HCDR3 (8, 20).

Although the expression of BCRs of class-switched isotype often suggest involvement in T cell–dependent responses, the lack of significant numbers of IgV gene mutations in B lymphocytes is unusual for T cell–mediated differentiation and classical germinal center (GC) passage, unless one invokes the possibilities that the germline sequence is preferred for antigen binding or that secondary rearrangements occurred at both the H- and L-chain loci. However, the lack of IgV gene mutations and the occurrence of a limited degree of isotype class switching also occur during B cell clonal expansion in the absence of T cell help and in response to T-independent antigens (74). Previous studies suggest that antigen-stimulated B cells that participate in a GC reaction lead to B cell lymphoproliferative disorders such as follicular cell lymphoma and Burkitt’s lymphoma (75). Nevertheless, B cells that follow a different pathway of B cell activation — that is, one not involving a classical GC reaction (76, 77) — could develop into B-CLL cells in certain instances. The marginal zone is considered a possible site for such nonclassical GC reactions (74) and the development of B-CLL from marginal zone B cells has been suggested (4). This suggestion is intriguing because the marginal zone is enriched in B cells that react with carbohydrates (74) and autoantigens (78–80), and its Ig V gene repertoire, at least in rodents, is highly restricted (81, 82). This receptor restriction apparently occurs early in life and is based on BCR composition, specificity, and signal-transducing capacity (81).

Finally, since these and other B-CLL clones express BCRs with restricted antigen-binding sites, antigen drive could promote intraclonal evolution leading to accumulation of deleterious DNA mutations by members of the leukemic clone and subsequently to a more aggressive clinical course. Repetitive engagement of the BCRs by either autoantigens or foreign antigens, possibly from microorganisms that are encountered during intermittent or persistent infections, could elicit such effects. In this regard, the cases that have the most convincing molecular evidence for BCR restriction and antigen or superantigen selection (i.e., these IgG+ cases and those expressing VH3–21 and VH1–69) experience more aggressive clinical courses with shortened mean survival times (72, 83, 84). In addition, ongoing B cell activation and differentiation can occur in B-CLL cells (10, 85–88) and may be initiated or augmented by BCR-mediated signal transduction that is preserved more often in those cases with the worst clinical outcomes (89, 90).

Supplementary Material

Supplemental data

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the valuable discussions and suggestions of Martin Weigert (Princeton University) and Michael Potter (National Cancer Institute). These studies were supported in part by RO1 grants from the National Cancer Institute (CA 81554 and CA 87956), General Clinical Research Center grant (M01 RR018535) from the NIH/NCRR, the Joseph Eletto Leukemia Research Fund, the Jean Walton Fund for Lymphoma and Myeloma Research, the Peter Jay Sharp Foundation, and Associazone Italiana Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC).

Footnotes

See the related Commentary beginning on page 952.

Fabio Ghiotto’s present address is: Dipartimento di Medicina Sperimentale, Sezione di Anatomia Umana, Università di Genova, Genoa, Italy.

Angelo Valetto’s present address is: Divisione di Citogenetica e Genetica Molecolare, Azienda Ospedaliera Pisana Santa Chiara, Pisa, Italy.

Shiori Hashimoto’s present address is: Department of Neurology, Neurological Institute, Tokyo Women’s Medical University, Tokyo, Japan.

Mariella Dono’s present address is: Division of Medical Oncology C, Istituto Nazionale per la Ricerca sul Cancro, Genoa, Italy.

Nonstandard abbreviations used: arsonate (Ars); B cell antigen receptor (BCR); B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (B-CLL); double-stranded DNA (dsDNA); framework region (FR); germinal center (GC); heavy chain third complementarity-determining region (HCDR3); light chain third complementarity-determining region (LCDR3); single-stranded DNA (ssDNA); web antibody modeling (WAM).

Conflict of interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Rai, K.R., and Patel, D.V. 1995. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia. In Hematology: basic principles and practice. R. Hoffman, E. Benz, S. Shattil, B. Furie, H. Cohen, and L. Silberstein, editors. Churchill Livingstone, New York. 1308–1321.

- 2.Rozman C, Montserrat E. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995;333:1052–1057. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199510193331606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oscier DG. Cytogenetic and molecular abnormalities in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Blood Rev. 1994;8:88–97. doi: 10.1016/s0268-960x(05)80013-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiorazzi N, Ferrarini M. B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia: lessons learned from studies of the B cell antigen receptor. Ann. Rev. Immunol. 2003;21:841–894. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Valetto A, et al. A subset of IgG+ B-CLL cells expresses virtually identical antigens receptors that bind similar peptides. Blood. 1998;92:431a. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chiorazzi, N., and Ferrarini, M. 2001. Immunoglobulin variable region gene characteristics and surface membrane phenotype define B-CLL subgroups with distinct clinical courses. In Chronic lymphoid leukemia, 2nd Ed. B.D. Cheson, editor. Marcel Dekker, New York. 81–109.

- 7.Hashimoto S, et al. Somatic diversification and selection of immunoglobulin heavy and light chain variable region genes in IgG+ CD5+ chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells. J. Exp. Med. 1995;181:1507–1517. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.4.1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fais F, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells express restricted sets of mutated and unmutated antigen receptors. J. Clin. Invest. 1998;102:1515–1525. doi: 10.1172/JCI3009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ikematsu W, et al. Surface phenotype and Ig heavy-chain gene usage in chronic B-cell leukemias: expression of myelomonocytic surface markers in CD5– chronic B-cell leukemia. Blood. 1994;83:2602–2610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fais F, et al. Examples of in vivo isotype class switching in IgM+ chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells. J. Clin. Invest. 1996;98:1659–1666. doi: 10.1172/JCI118961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tomlinson, I., Williams, S., Corbett, S., Cox, J., and Winter, G. 1996. V BASE sequence directory. MRC Centre for Protein Engineering, Cambridge, United Kingdom. http://www.mrc-cpe.cam.ac.uk/vbase-ok.php?menu=901.

- 12.Kabat, E.A., Wu, T.T., Perry, H.M., Gottesman, K.S., and Foeller, C. 1991. Sequences of proteins of immunological interest. Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, Washington, DC.

- 13.Chothia C, Lesk AM. Canonical structures for the hypervariable regions of immunoglobulins. J. Mol. Biol. 1987;196:901–917. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90412-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson G, Wu TT. Kabat database and its applications: 30 years after the first variability plot. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:214–218. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Web Antibody Modelling. http://www.bath.ac.uk/cpad/.

- 16.Dayringer HE, Tramontano A, Sprang SR, Fletterick RJ. Interactive program for visualization and modeling of protein, nucleic acid and small molecules. J. Mol. Graph. 1986;4:82–87. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davis ZA, Orchard JA, Corcoran MM, Oscier DG. Divergence from the germ-line sequence in unmutated chronic lymphocytic leukemia is due to somatic mutation rather than polymorphisms. Blood. 2003;102:3075. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schroeder HW, Jr, Dighiero G. The pathogenesis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: analysis of the antibody repertoire. Immunol. Today. 1994;15:288–294. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(94)90009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brezinschek HP, et al. Analysis of the human VH gene repertoire. Differential effects of selection and somatic hypermutation on human peripheral CD5(+)/IgM+ and CD5(–)/IgM+ B cells. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;99:2488–2501. doi: 10.1172/JCI119433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson TA, Rassenti LZ, Kipps TJ. Ig VH1 genes expressed in B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia exhibit distinctive molecular features. J. Immunol. 1997;158:235–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Terness P, et al. Idiotypic vaccine for treatment of human B-cell lymphoma. Construction of IgG variable regions from single malignant B cells. Hum. Immunol. 1997;56:17–27. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(97)00145-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Welschof M, et al. Amino acid sequence based PCR primers for amplification of rearranged human heavy and light chain immunoglobulin variable region genes. J. Immunol. Methods. 1995;179:203–214. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(94)00286-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maloum K, et al. Expression of unmutated VH genes is a detrimental prognostic factor in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2000;96:377–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tramontano A, Chothia C, Lesk AM. Framework residue 71 is a major determinant of the position and conformation of the second hypervariable region in the VH domains of immunoglobulins. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;215:175–182. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80102-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morea V, Tramontano A, Rustici M, Chothia C, Lesk AM. Conformations of the third hypervariable region in the VH domain of immunoglobulins. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;275:269–294. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Albesiano E, et al. Multiple examples of identical heavy and light chain Ig rearrangements support a primary role for antigen in the development of B-CLL. Blood. 2003;102:664a. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tobin, G., et al. 2003. Restricted VH, D and JH gene usage and homologous CDR3s in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). Blood. In press.

- 28.Feeney AJ. Predominance of VH-D-JH junctions occurring at sites of short sequence homology results in limited junctional diversity in neonatal antibodies. J. Immunol. 1992;149:222–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gu H, Forster I, Rajewsky K. Sequence homologies, N sequence insertion and JH gene utilization in VHDJH joining: implications for the joining mechanism and the ontogenetic timing of Ly1 B cell and B-CLL progenitor generation. EMBO J. 1990;9:2133–2140. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07382.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Potter KN, et al. Features of the overexpressed V1-69 genes in the unmutated subset of chronic lymphocytic leukemia are distinct from those in the healthy elderly repertoire. Blood. 2003;101:3082–3084. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-08-2432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rudikoff S. Antibodies to beta(1, 6)-D-galactan: proteins, idiotypes and genes. Immunol. Rev. 1988;105:97–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1988.tb00768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sikder SK, Akolkar PN, Kaladas PM, Morrison SL, Kabat EA. Sequences of variable regions of hybridoma antibodies to alpha (1——6) dextran in BALB/c and C57BL/6 mice. J. Immunol. 1985;135:4215–4221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang DN, et al. Two families of monoclonal antibodies to alpha(1——6)dextran, VH19.1.2 and VH9.14.7, show distinct patterns of J kappa and JH minigene usage and amino acid substitutions in CDR3. J. Immunol. 1990;145:3002–3010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perlmutter RM, et al. The generation of diversity in phosphorylcholine-binding antibodies. Adv. Immunol. 1984;35:1–37. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60572-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Potter M. Antigen-binding myeloma proteins of mice. Adv. Immunol. 1977;25:141–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pennell CA, Arnold LW, Haughton G, Clarke SH. Restricted Ig variable region gene expression among Ly-1+ B cell lymphomas. J. Immunol. 1988;141:2788–2796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hardy RR, Carmack CE, Li YS, Hayakawa K. Distinctive developmental origins and specificities of murine CD5+ B cells. Immunol. Rev. 1994;137:91–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1994.tb00660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seidl KJ, et al. Frequent occurrence of identical heavy and light chain Ig rearrangements. Int. Immunol. 1997;9:689–702. doi: 10.1093/intimm/9.5.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Insel RA, Adderson EE, Carroll WL. The repertoire of human antibody to the Haemophilus influenzae type b capsular polysaccharide. Int. Rev. Immunol. 1992;9:25–43. doi: 10.3109/08830189209061781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scott MG, Zachau HG, Nahm MH. The human antibody V region repertoire to the type B capsular polysaccharide of Haemophilus influenzae. Int. Rev. Immunol. 1992;9:45–55. doi: 10.3109/08830189209061782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lucas AH, Moulton KD, Reason DC. Role of kappa II-A2 light chain CDR-3 junctional residues in human antibody binding to the Haemophilus influenzae type b polysaccharide. J. Immunol. 1998;161:3776–3780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun Y, et al. Repertoire of human antibodies against the polysaccharide capsule of Streptococcus pneumoniae serotype 6B. Infect. Immun. 1999;67:1172–1179. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.3.1172-1179.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou J, Lottenbach KR, Barenkamp SJ, Lucas AH, Reason DC. Recurrent variable region gene usage and somatic mutation in the human antibody response to the capsular polysaccharide of Streptococcus pneumoniae type 23F. Infect. Immun. 2002;70:4083–4091. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.8.4083-4091.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pascual V, et al. VH restriction among human cold agglutinins. The VH4-21 gene segment is required to encode anti-I and anti-i specificities. J. Immunol. 1992;149:2337–2344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thompson KM, et al. Human monoclonal antibodies against blood group antigens preferentially express a VH4-21 variable region gene-associated epitope. Scand. J. Immunol. 1991;34:509–518. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1991.tb01574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Silberstein LE, George A, Durdik JM, Kipps TJ. The V4-34 encoded anti-i autoantibodies recognize a large subset of human and mouse B-cells. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 1996;22:126–138. doi: 10.1006/bcmd.1996.0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Silverman GJ, et al. Idiotypic and subgroup analysis of human monoclonal rheumatoid factors. Implications for structural and genetic basis of autoantibodies in humans. J. Clin. Invest. 1988;82:469–475. doi: 10.1172/JCI113620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Silverman GJ, Schrohenloher RE, Accavitti MA, Koopman WJ, Carson DA. Structural characterization of the second major cross-reactive idiotype group of human rheumatoid factors. Association with the VH4 gene family. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:1347–1360. doi: 10.1002/art.1780330907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Martin T, et al. Salivary gland lymphomas in patients with Sjogren’s syndrome may frequently develop from rheumatoid factor B cells. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:908–916. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200004)43:4<908::AID-ANR24>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mariette X. Lymphomas complicating Sjogren’s syndrome and hepatitis C virus infection may share a common pathogenesis: chronic stimulation of rheumatoid factor B cells. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2001;60:1007–1010. doi: 10.1136/ard.60.11.1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.De Re V, et al. Salivary gland B cell lymphoproliferative disorders in Sjogren’s syndrome present a restricted use of antigen receptor gene segments similar to those used by hepatitis C virus-associated non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. Eur. J. Immunol. 2002;32:903–910. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200203)32:3<903::AID-IMMU903>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Milner EC, Capra JD. VH families in the antibody response to p-azophenylarsonate: correlation between serology and amino acid sequence. J. Immunol. 1982;129:193–199. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jeske DJ, Jarvis J, Milstein C, Capra JD. Junctional diversity is essential to antibody activity. J. Immunol. 1984;133:1090–1092. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sanz I, Capra J. VK and JK gene segments of A/J Ars-A antibodies: somatic recombination generates the essential arginine at the junction of the variable and joining regions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1987;84:1085–1089. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.4.1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Casadevall A, Scharff MD. The mouse antibody response to infection with Cryptococcus neoformans: VH and VL usage in polysaccharide binding antibodies. J. Exp. Med. 1991;174:151–160. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.1.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Scott MG, et al. Clonal characterization of the human IgG antibody repertoire to Haemophilus influenzae type b polysaccharide. III. A single VKII gene and one of several JK genes are joined by an invariant arginine to form the most common L chain V region. J. Immunol. 1989;143:4110–4116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ibrahim SM, Weigert M, Basu C, Erikson J, Radic MZ. Light chain contribution to specificity in anti-DNA antibodies. J. Immunol. 1995;155:3223–3233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Radic MZ, et al. Residues that mediate DNA binding of autoimmune antibodies. J. Immunol. 1993;150:4966–4977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rudikoff S, Rao DN, Glaudemans CP, Potter M. kappa Chain joining segments and structural diversity of antibody combining sites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1980;77:4270–4274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.7.4270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen C, et al. Deletion and editing of B cells that express antibodies to DNA. J. Immunol. 1994;152:1970–1982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.James LC, Roversi P, Tawfik DS. Antibody multispecificity mediated by conformational diversity. Science. 2003;299:1362–1367. doi: 10.1126/science.1079731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Merlini G, Farhangi M, Osserman EF. Monoclonal immunoglobulins with antibody activity in myeloma, macroglobulinemia and related plasma cell dyscrasias. Semin. Oncol. 1986;13:350–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Azmi FH, Lucas AH, Spiegelberg HL, Granoff DM. Human immunoglobulin M paraproteins cross-reactive with Neisseria meningitidis group B polysaccharide and fetal brain. Infect. Immun. 1995;63:1906–1913. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.1906-1913.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Adderson EE, Shikhman AR, Ward KE, Cunningham MW. Molecular analysis of polyreactive monoclonal antibodies from rheumatic carditis: human anti-N-acetylglucosamine/anti-myosin antibody V region genes. J. Immunol. 1998;161:2020–2031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Diaw L, et al. Restricted immunoglobulin variable region (Ig V) gene expression accompanies secondary rearrangements of light chain Ig V genes in mouse plasmacytomas. J. Exp. Med. 1999;190:1405–1416. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.10.1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Briles DE, et al. Antiphosphocholine antibodies found in normal mouse serum are protective against intravenous infection with type 3 streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Exp. Med. 1981;153:694–705. doi: 10.1084/jem.153.3.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ochsenbein AF, et al. Control of early viral and bacterial distribution and disease by natural antibodies. Science. 1999;286:2156–2159. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5447.2156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Diamond B, Scharff MD. Somatic mutation of the T15 heavy chain gives rise to an antibody with autoantibody specificity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1984;81:5841–5844. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.18.5841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sthoeger ZM, et al. Production of autoantibodies by CD5-expressing B lymphocytes from patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J. Exp. Med. 1989;169:255–268. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.1.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Borche L, Lim A, Binet JL, Dighiero G. Evidence that chronic lymphocytic leukemia B lymphocytes are frequently committed to production of natural autoantibodies. Blood. 1990;76:562–569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wakai M, et al. IgG+, CD5+ human chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells. Production of IgG antibodies that exhibit diminished autoreactivity and IgG subclass skewing. Autoimmunity. 1994;19:39–48. doi: 10.3109/08916939409008007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tobin G, et al. Somatically mutated Ig V(H)3-21 genes characterize a new subset of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2002;99:2262–2264. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.6.2262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tobin G, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemias utilizing the VH3-21 gene display highly restricted V{lambda}2-14 gene use and homologous CDR3s: implicating recognition of a common antigen epitope. Blood. 2003;101:4952–4957. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Martin F, Kearney JF. Marginal-zone B cells. Positive selection from newly formed to marginal zone B cells depends on the rate of clonal production, CD19, and btk. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2002;2:323–335. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kuppers R, Dalla-Favera R. Mechanisms of chromosomal translocations in B cell lymphomas. Oncogene. 2001;20:5580–5594. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Weller S, et al. CD40-CD40L independent Ig gene hypermutation suggests a second B cell diversification pathway in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001;98:1166–1170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.3.1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.William J, Euler C, Christensen S, Shlomchik MJ. Evolution of autoantibody responses via somatic hypermutation outside of germinal centers. Science. 2002;297:2066–2070. doi: 10.1126/science.1073924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chen X, Martin F, Forbush KA, Perlmutter RM, Kearney JF. Evidence for selection of a population of multi-reactive B cells into the splenic marginal zone. Int. Immunol. 1997;9:27–41. doi: 10.1093/intimm/9.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bendelac A, Bonneville M, Kearney JF. Autoreactivity by design: innate B and T lymphocytes. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2001;1:177–186. doi: 10.1038/35105052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Li Y, Li H, Weigert M. Autoreactive B cells in the marginal zone that express dual receptors. J. Exp. Med. 2002;195:181–188. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Martin F, Kearney JF. Positive selection from newly formed to marginal zone B cells depends on the rate of clonal production, CD19, and btk. Immunity. 2000;12:39–49. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dammers PM, Visser A, Popa ER, Nieuwenhuis P, Kroese FG. Most marginal zone B cells in rat express germline encoded Ig VH genes and are ligand selected. J. Immunol. 2000;165:6156–6169. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.11.6156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Damle RN, et al. Ig V gene mutation status and CD38 expression as novel prognostic indicators in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 1999;94:1840–1847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hamblin TJ, Davis Z, Gardiner A, Oscier DG, Stevenson FK. Unmutated Ig VH genes are associated with a more aggressive form of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 1999;94:1848–1854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Fu SM, Chiorazzi N, Kunkel HG, Halper JP, Harris SR. Induction of in vitro differentiation and immunoglobulin synthesis of human leukemic B lymphocytes. J. Exp. Med. 1978;148:1570–1578. doi: 10.1084/jem.148.6.1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Totterman TH, Nilsson K, Sundstrom C. Phorbol ester-induced differentiation of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia cells. Nature. 1980;288:176–178. doi: 10.1038/288176a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rubartelli A, Sitia R, Zicca A, Grossi CE, Ferrarini M. Differentiation of chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells: correlation between the synthesis and secretion of immunoglobulins and the ultrastructure of the malignant cells. Blood. 1983;62:495–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gurrieri C, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells undergo somatic hypermutation and intraclonal immunoglobulin VHDJH gene diversification. J. Exp. Med. 2002;196:629–639. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zupo S, et al. CD38 expression distinguishes two groups of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemias with different responses to anti-IgM antibodies and propensity to apoptosis. Blood. 1996;88:1365–1374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lanham S, et al. Differential signaling via surface IgM is associated with VH gene mutational status and CD38 expression in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2003;101:1087–1093. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kraulis PJ. MOLSCRIPT: a program to produce both detailed and schematic plots of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1991;24:946–950. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Merritt EA, Murphy MEP. Raster3D Version 2.0: a program for photorealistic molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D. 1994;50:869–873. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994006396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Nicholls A, Sharp KA, Honig B. Protein folding and association: insights from the interfacial and thermodynamic properties of hydrocarbons. Proteins. 1991;11:281–296. doi: 10.1002/prot.340110407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Klein R, Jaenichen R, Zachau HG. Expressed human immunoglobulin kappa genes and their hypermutation. Eur. J. Immunol. 1993;23:3248–3262. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830231231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Graille M, et al. Complex between Peptostreptococcus magnus protein L and a human antibody reveals structural convergence in the interaction modes of Fab binding proteins. Structure. 2001;9:679–687. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(01)00630-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Jacobin MJ, et al. Human IgG monoclonal anti-alpha(IIb)beta(3)-binding fragments derived from immunized donors using phage display. J. Immunol. 2002;168:2035–2045. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.4.2035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.de Wildt RM, Hoet RMA, van Venrooij WJ, Tomlinson IM, Winter G. Analysis of heavy and light chain pairings indicates that receptor editing shapes the human antibody repertoire. J. Mol. Biol. 1999;285:895–901. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Brown CM, Plater-Zyberk C, Mageed RA, Jefferis R, Maini RN. Analysis of immunoglobulins secreted by hybridomas derived from rheumatoid synovia. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1990;80:366–372. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1990.tb03294.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Chang TY, Siegel DL. Genetic and immunological properties of phage-displayed human anti-Rh(D) antibodies: implications for Rh(D) epitope topology. Blood. 1998;91:3066–3078. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental data