Immune Interactions with Pathogenic and Commensal Fungi: A Two-Way Street (original) (raw)

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2016 May 12.

Abstract

We are exposed to a wide spectrum of fungi including innocuous environmental organisms, opportunistic pathogens, commensal organisms, and fungi that can actively and explicitly cause disease. Much less is understood about effective host immunity to fungi than is generally known about immunity to bacterial and viral pathogens. Innate and adaptive arms of the immune system are required for effective host defense against Candida, Aspergillus, Cryptococcus, and others, with specific elements of the host response regulating specific types of fungal infections (e.g., mucocutaneous versus systemic). Here we will review themes and controversies that are currently shaping investigation of antifungal immunity (primarily to Candida and Aspergillus) and will also examine the emerging field of the role of fungi in the gut microbiome.

Introduction

Although it is widely accepted that fungi are ubiquitous in our environment and have huge impacts on plant and animal life, the biomedical importance of fungi is often not widely appreciated. Our lungs are constantly exposed to airborne spores of common molds such as Aspergillus and Fusarium, which generally do not lead to infectious outcomes. Also, our mucosal surfaces are colonized with commensal yeasts, including Candida and Malassezia species. Superficial fungal infections such as athlete’s foot and ringworm are common and affect nearly 25% of the global population annually (Havlickova et al., 2008). Aspergillus and Fusarium are major causes of blinding corneal ulcers worldwide, and in contrast to most other fungal infections, occur in immune-competent individuals (Thomas and Kaliamurthy, 2013). Invasive fungal diseases (e.g., candidiasis, pneumocystis, cryptococcosis, mucomycosis) affect more than 2 million people annually and in some cases can have mortality rates that exceed 50% (reviewed in Brown et al., 2012). Further, in U.S. hospitals, nearly 10% of nosocomial infections are fungal, exceeded only by staphylococci and enterococci (Pfaller and Diekema, 2010). Altogether, it is estimated that fungal infections kill more people worldwide than tuberculosis or malaria (Brown et al., 2012). An understanding of the mechanisms of host immunity to fungi will be important for development of new and more effective approaches to preventing and treating fungal diseases. In addition to immunity to pathogenic fungi, studies are emerging that demonstrate a role for commensal fungi as an integral component of the microbiome (the mycobiome). In this review, we explore recent advances in anti-fungal immunity, primarily in innate immune responses. Conversely, we will also examine the previously neglected role of commensal fungi on the outcome of other diseases. Given space limitations, we will focus most of the review on responses to the most intensively reported pathogenic yeasts (Candida) and molds (Aspergillus).

Immunogenetics of Antifungal Host Defense

The mammalian immune response to infection is highly diverse and has evolved mechanisms tailored to best fight the type of infection that is present. Fungi are ubiquitous in our environment, so nearly all aspects of host immunity can be implicated in antifungal host defense at one level or another. As such, an examination of human genetic variants and mutations associated with susceptibility to fungal infections provides a useful approach to identifying the types of immunity that are most strongly associated with effective host defense, and which most deserve a closer experimental examination of mechanisms. We also refer the reader to several excellent reviews on this topic (Lanternier et al., 2013a; Lionakis, 2012; Smeekens et al., 2013).

Susceptibility to fungal infections is associated with mutations in phagocytic and cellular immunity as shown in Table 1. For example, genetic defects in proteins comprising the NADPH oxidase complex resulting in impaired reactive oxygen production, or mutations resulting in neutropenia, are well-known risk factors for fungal infection and indicate a central role for neutrophils in anti-fungal immunity (Falcone and Holland, 2012). Additional examples of immune responses that are currently intense areas of ongoing research are highlighted below. Although the reported genetic associations rarely point to humoral immunity, antibodies can provide protection from fungal infections, and the reader is directed to a recent review of this topic (Casadevall and Pirofski, 2012).

Table 1.

Human Genetic Associations with Immunity to Fungi

| Gene(s) | Result | Fungi Involved | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| CYBA, CYBB, NCF1, NCF2, NCF4 | **Chronic Granulomatous Disease.**Defect in reactive oxygen production by theNADPH oxidase that is important for killing offungi by neutrophils. Increased susceptibilityto invasive fungal disease. | Aspergillus spp. in the lungs (esp.A. fumigatus, A. nidulans, A. flavus).Lung infection with other opportunisticfilamentous fungi (e.g., Geosmithia argillacea).Candida spp. | (Falcone and Holland, 2012; Liese et al., 2000) |

| IL2RG, RAG1, RAG2, ADA | **Severe-Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID).**Loss of T cells and sometimes B cells.Susceptibility to a broad spectrum of pathogens,but especially common chronic mucocutaneouscandidiasis (CMC). | Candida spp. (e.g., C. albicans,C. parapsilosis)Pneumocystis spp. (e.g., P. jirovecii) | (Lanternier et al., 2013a) |

| DOCK8, STAT3 | **Hyper Immunoglobulin E syndrome.**Defective T cell activation, including Th17 cellactivation, due to impaired immunologicalsynapse (DOCK8) or differentiation (STAT3).Susceptibility to a broad spectrum of pathogens,but especially common chronic mucocutaneouscandidiasis (CMC). | Candida spp. of mucosal surfaces_Aspergillus_ spp. and _Scedosporium_spp. in the lungs | (Engelhardt et al., 2009;Holland et al., 2007;Minegishi et al., 2007) |

| AIRE | Autoimmune polyendocrinopathy syndrome **type 1 (APS-1).**Autoantibodies toward IL-17A, IL-17F, and IL-22,autoreactive T cells due to loss of tolerance.Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis (CMC) | Candida spp. (e.g., C. albicans,C. parapsilosis) | (Nagamine et al., 1997) |

| UNC119, MAGT1, RAG1 | **Idiopathic CD4 Lymphopenia.**Low T cell counts and susceptibility to diversemucosal and systemic fungal infections. | Cryptococcus Candida spp. Pneumocystis spp. (e.g., P. jirovecii)Histoplasma | (Ahmad et al., 2013;Walker and Warnatz, 2006) |

| RORC | RORγ or RORγt loss of function. CMC togetherwith susceptibility to mycobacterial infection. | Candida spp. | (Okada et al., 2015) |

| STAT1 | Defective IL-17, IL-22, andIFN-γ production. Common CMC. | Candida spp. | (Puel et al., 2012) |

| CLEC7A, CARD9 | Impaired IL-1β, IL-22, and IL-17 production.Impaired phagocytosis of yeasts (Dectin-1).Reduced Th17 responses. CMC, onychomycosis,deep dermatophytosis, and invasive disease. | Candida spp. | (Ferwerda et al., 2009;Glocker et al., 2009;Lanternier et al., 2013b) |

| IL17RA, IL17F | Impaired IL-17 axis and impaired responses toIL-17RA. Common CMC. | Candida spp. | (Puel et al., 2011) |

| MBL2 | Decreased mannose-binding lectin (MBL)concentrations. Recurrent vulvovaginalcandidiasis (RVVC).Chronic necrotizing pulmonary aspergillosis(CNPA). | Candida spp.Aspergillus spp. | (Babula et al., 2003;Crosdale et al., 2001) |

| IL12RB1 | Abolished responses to IL-12 and IL-23.Common CMC. | Candida spp. | (Ouederni et al., 2014) |

| IL22 | Increased IL-22 production. Resistance tovulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) and recurrentvulvovaginal candidiasis (RVVC). | C. albicans, C. glabrata | (De Luca et al., 2013) |

| IDO1 | Increased IDO1 expression. Resistance tovulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) and recurrentvulvovaginal candidiasis (RVVC). | C. albicans, C. glabrata | (De Luca et al., 2013) |

| PTX3 | Decreased expression of long pentraxin 3 andincreased susceptibility to fungal infection. | Aspergillus spp. in the lungs of stemcell transplant patients. | (Cunha et al., 2014) |

| IL1B, NLRP3 | Reduced fungal-induced IL-1β production.Recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis orsusceptibility to pulmonary aspergillosis. | C. albicans, Aspergillus | (Lev-Sagie et al., 2009;Sainz et al., 2008) |

HIV patients are at increased risk for developing fungal infections such as oral candidiasis and Pneumocystis (Lanternier et al., 2013a). Similarly, severe-combined immunodeficiency is associated with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis (CMC), and T cell deficiencies (e.g., idiopathic CD4+ lymphocytopenia) are associated with meningoencephalitis caused by Cryptococcus and to interstitial pneumonia due to infection with Pneumocystis (Lanternier et al., 2013a). Table 1 also illustrates that genetic defects or variants in the T cell signaling proteins (especially those mediating interleukin-17 [IL-17] and IL-22) have been linked to fungal infections. Thus T cells are undoubtedly essential for host defense against diverse fungi.

In a recent study, patients with combined susceptibility to CMC and mycobacteria have been discovered to have loss-of-function mutations in the RORC transcription factor (Okada et al., 2015). These patients lack functional RORγ or RORγt. Among the phenotypes associated with this loss is a deficiency in lymphoid tissue inducer (LTi) cells, type 3 innate lymphoid cells (ILC3), and subsets of αβ T cells utilizing specific Vα T cell receptor segments. RORγt is essential for IL-17 production by lymphoid cells, and T cells from these patients are deficient in IL-17 production. As discussed below, RORγt is also important for IL-17 production by neutrophils, and it will be interesting to see whether these patients also have defects in neutrophil responses to infection.

Lectins have long been associated with susceptibility to fungal infections. For example, low expression of the soluble lectin mannose-binding-lectin (MBL), first recognized in the 1960s, disrupts the ability of serum to opsonize yeast (Miller et al., 1968), and MBL2 polymorphisms resulting in reduced MBL expression are associated with increased risk for vulvovaginal candidiasis and pulmonary aspergillosis (Babula et al., 2003; Crosdale et al., 2001; Garred et al., 2006). More recently, polymorphisms reducing expression of the soluble lectin pentraxin 3, which can bind to Aspergillus fumigatus, have been have been linked to increased incidence of aspergillosis in patients undergoing stem-cell transplantation (Cunha et al., 2014).

Multiple studies have linked expression of the C-type lectin receptor (CLR) Dectin-1 with susceptibility to mucosal infection with Candida. Dectin-1 is expressed on myeloid cells and recognizes fungal β-glucan, which triggers phagocytosis and production of inflammatory cytokines. Netea and co-workers have identified a polymorphism (premature stop codon) in the gene for Dectin-1 that is associated with mucocutaneous fungal infections (Ferwerda et al., 2009) and Candida colonization in transplant patients (Plantinga et al., 2009). Similarly, mutations in the CARD9 signaling adaptor molecule, downstream of Dectin-1 and other C-type lectins, are associated with increased susceptibility to invasive Candida infections, especially if patients have a history of oral infections (Drewniak et al., 2013; Glocker et al., 2009). Patients with CARD9 deficiency have decreased numbers of T helper 17 (Th17) cells and impaired activation of neutrophils to kill fungi due to reduced fungal-stimulated cytokine and chemokine production. Together, the data strongly implicate the C-type lectin axis as particularly important in host defense against fungi.

Genetic variations in Toll-like receptors (TLRs) that are clearly linked to susceptibility to fungal infections have been difficult to identify in otherwise healthy individuals. TLR1 variants are associated with increased risk for candidemia (Plantinga et al., 2012). Also, polymorphisms in TLR1, TLR4, and TLR6 have been linked to aspergillosis in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant patients (Skevaki et al., 2015).

Secretion of the inflammatory cytokine IL-1β requires production of pro-IL-1β followed by proteolytic cleavage to the mature form by “inflammasome” complexes, including those utilizing NLRP3 and NLRC4 (Netea et al., 2015). Mutations in intron 4 of the NLRP3 inflammasome gene are linked to women with vulvar vestibulitis syndrome and recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis and are associated with reduced production of IL-1β in response to C. albicans (Lev-Sagie et al., 2009). Similarly, polymorphisms in the gene IL1B but not IL1A or IL1R1 are associated with increased risk for invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (Sainz et al., 2008).

Whole-genome analysis has identified multiple genes associated with increased susceptibility to fungal infections, including genes associated with leukocyte migration, extracellular matrix formation, and epidermal maintenance and wound healing (Abdel-Rahman and Preuett, 2012). In a recent study using an “Immunochip” array with more than 100,000 SNPs, Netea and co-workers have found that polymorphisms in both CD58 (lymphocyte function-associated antigen 3 on T cells) and in the T cell activation RhoGTPase-activating protein (TAGAP) are associated with a 19-fold increased susceptibility to candidemia (Kumar et al., 2014). These genes are also associated with autoimmune and auto-inflammatory disease, including Crohn’s disease. We anticipate that the list of genes associated with fungal infection will increase as a result of this technology and will identify additional mechanisms of anti-fungal host defenses.

Overall, these natural mutations in humans provide a strong rationale for further investigation of the roles of specific types of innate immunity (different phagocyte subsets and pattern-recognition receptors) and adaptive immunity (especially Th17 cell related) in controlling fungal infections.

C-Type Lectin Receptors

The roles of TLRs, Nod-like receptors (NLR), and RIG-I receptors in fungal infections have been reviewed recently (Drummond and Brown, 2013; Sancho and Reis e Sousa, 2012) and will not be discussed here. Brown and colleagues categorize C-type lectin receptors (CLRs) into the Dectin-1 and Dectin-2 clusters based on their locations on mouse chromosome 6 and human chromosome 12 (Dambuza and Brown, 2015; Drummond and Brown, 2013). These and other excellent reviews describe the members of each group and discuss signal transduction pathways (Sancho and Reis e Sousa, 2012); therefore in the current review, we will provide an overview and focus on recent and sometimes controversial findings.

The family of CLRs was originally defined by their carbohydrate-recognition domains (CRDs), although some have since been shown to bind ligands other than carbohydrates, including mycobacterial antigens (reviewed by Drummond and Brown, 2013, who term these type I and type II CLRs). Dectin-1 (CLEC7a) was the first CLR to be characterized and was found to recognize β-glucan on the cell wall of most species of fungi (Brown and Gordon, 2001). Dectin-1 is required for a protective immune response to yeast and mold infections, including Aspergillus fumigatus lung and corneal infections, oral candidiasis, and coccidiomycosis (Hise et al., 2009; Leal et al., 2010; Viriyakosol et al., 2013; Werner et al., 2009). However, the first reports of the role of Dectin-1 in systemic candidiasis in mice have been conflicting, with one group reporting a protective role for Dectin-1 and a second group showing that Dectin-1 has no role during Candida albicans infection (Saijo et al., 2007; Taylor et al., 2007). This difference was found to be strain dependent, with the latter group using a strain of Candida having more cell surface chitin and thus less exposed cell wall β-glucan (Marakalala et al., 2013). Although several TLRs are implicated in protection from fungi, how these responses relate to CLR activity has been unclear. A recent study has used chimeric mice to show that CARD9-dependent protective responses to A. fumigatus lung infection are dependent on myeloid cells, whereas the required MyD88 adaptor molecule-dependent response is mediated by IL-1R1 activation on pulmonary epithelial cells and not TLRs (Jhingran et al., 2015).

As alluded to above, fungal recognition by Dectin-1 is dependent on exposure of cell wall β-glucan at the cell surface, which can vary among different types of fungi and different morphological forms of fungi. In addition to variation among strains of Candida, β-glucan exposure is different between yeast and filamentous forms of the organism (Gantner et al., 2005; Kashem et al., 2015). Dectin-1 is not activated by dormant Aspergillus conidia, which do not express β-glucan on the cell surface; however, after germination, β-glucan is exposed on the cell wall surface and can then be detected by Dectin-1 (Gersuk et al., 2006; Hohl et al., 2005; Steele et al., 2005). Genetic deletion of the RodA hydrophobin that covers the conidial surface results in exposure of underlying cell wall β-glucan and allows activation of Dectin-1 by conidia. In vivo, this results in an accelerated innate response and more rapid fungal clearance (Aimanianda et al., 2009; Carrion et al., 2013).

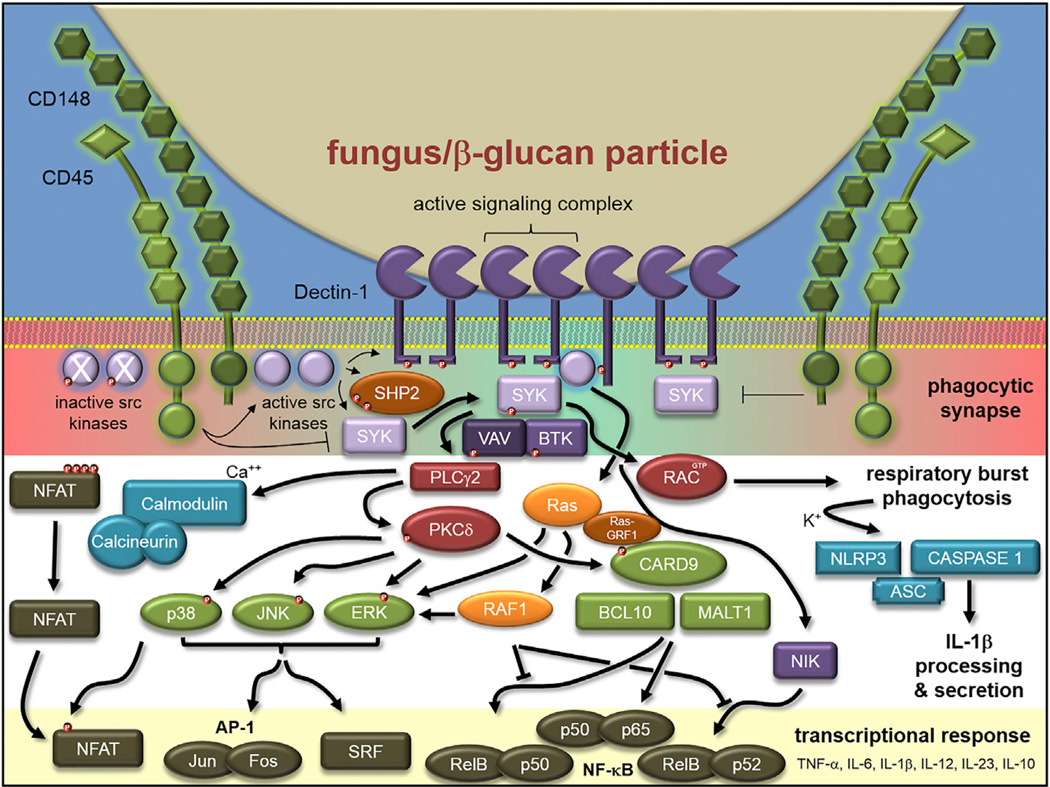

Signaling by Dectin-1 has been more widely studied than signaling by other CLRs and has been extensively reviewed (Figure 1; Drummond and Brown, 2013; Geijtenbeek and Gringhuis, 2009; Sancho and Reis e Sousa, 2012). Clustering of the Dectin-1 receptor occurs after stimulation with aggregated or particulate β-glucan, whereas soluble forms of β-glucan such as laminarin do not activate the receptor (Goodridge et al., 2011). Receptor clustering results in formation of a “phagocytic synapse” in which the inhibitory tyrosine phosphatases CD45 and CD148 are excluded, permitting sustained signaling and recruitment of additional signaling components including spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk). Dectin-1 has a small intracellular tail with a motif resembling an “immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif” (ITAM), which activates the cells by canonical Syk-dependent pathway through phospholipase C gamma (PLCγ) and phosphatidyl inositol 3′OH kinase (PI3K), resulting in formation of the CARD9-BCL10-MALT1 trimer and activation of NF-κB through the IKK complex (Figure 1). Syk activation of PLCγ also results in Ca2+ influx, and calcineurin-mediated activation of the NFAT transcription factor, whereas the Syk-independent pathway involves Raf-1 kinase-induced p65 phosphorylation that favors IL-12 p40 production and a Th1 cell-associated phenotype (Gringhuis et al., 2009). Dectin-1 activation directs phagocytosis, activation of the NADPH oxidase, and production of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines.

Figure 1. Dectin-1 Signaling Pathways.

Dectin-1 binds to β-glucan exposed at the surface of fungal cell walls. Clustering of Dectin-1 receptors and the exclusion of inhibitory protein phosphatases (CD45 and CD148) allows for sustained phosphorylation of the intracellular stalk of Dectin-1 that has a hemi-ITAM motif. Subsequent recruitment and phosphorylation of Syk induces signaling through the Syk-dependent, Raf-1-dependent, and NFAT pathways leading to activation of cellular responses that include phagocytosis, respiratory burst, and production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Red dots indicate phosphorylation. Diagram based on Goodridge et al. (2011).

Although Syk is recruited to the ITAM site of Dectin-1 in this pathway, an unresolved question relates to the intracellular region of this receptor, which has only one tyrosine in this motif (Tyr14-X-X-Leu, termed a hemi-ITAM), whereas Syk activation requires two tyrosine residues. A recent study provides a potential solution by demonstrating that the SHP-2 phosphatase promotes Dectin-1-mediated Syk phosphorylation (Figure 1; Deng et al., 2015). Although the phosphatase activity of SHP-2 has been well characterized, the study shows that SHP-2 has a cryptic ITAM site, which is important for optimal Dectin-1 phosphorylation and signaling. SHP-2 is also required for controlling systemic candidiasis (Deng et al., 2015).

Dectin-2 related CLRs are also clustered on human chromosome 12 and mouse chromosome 6, although in the telomeric region compared with the Dectin-1 cluster, which is in the centromeric region (reviewed by Dambuza and Brown, 2015). In contrast to Dectin-1, receptors in the Dectin-2 complex lack an intracellular tail; these CLRs interact with the Fc receptor common γ chain (FcRγ), and signaling is initiated through the ITAM region of FcRγ. To date, evidence indicates that signaling by CLRs in the Dectin-2 cluster is through the canonical pathway, which is dependent on Syk, activation of the CARD9-BCL10-MALT1 axis, and translocation of NF-κB to the nucleus.

Dectin-2 (CLEC6A in human, Clec4n in mice) has been shown to recognize α-mannans, although the precise ligand has not yet been defined (McGreal et al., 2006; Sato et al., 2006). _Clec4n_−/− mice are more susceptible to C. albicans and C. glabrata infections (Ifrim et al., 2014; Saijo et al., 2010). Dectin-2 mediates plasmacytoid dendritic cell contact with Aspergillus fumigatus hyphae and is required for anti-hyphal activity, possibly via formation of extracellular traps (Loures et al., 2015). Dectin-2 on macrophages also recognizes Aspergillus fumigatus hyphae and contributes to fungal clearance in vivo (Carrion et al., 2013). In contrast, the absence of Dectin-2 had no effect on clearance of Coccidiomycoses infection, even though Dectin-2 is expressed in the lungs of infected mice (Viriyakosol et al., 2014).

Macrophage-inducible C-type lectin (Mincle, also called Clec4e, ClecSf9) and macrophage C-type lectin (MCL, also called Dectin-3, Clec4d, ClecSf8) were originally shown to recognize mycobacterial glycolipids rather than fungi. Macrophage and dendritic cell responses to the mycobacterial cord factor trehalose-6,6-dimycolate (TDM) funnel through the canonical Syk-CARD9-BCL10-MALT1 pathway (Werninghaus et al., 2009), which has subsequently been shown to require Mincle (Ishikawa et al., 2009; Schoenen et al., 2010). However, Mincle is not expressed on resting macrophages. It is induced upon activation, and its surface expression is promoted by constitutively expressed MCL, which is also required for responses to TDM (Miyake et al., 2013, 2015).

With regards to fungi, a screen of 50 pathogenic fungi using Mincle reporter cells found only that Malassezia species were recognized, and infection of _Clec4e_−/− mice revealed that immune responses to Malassezia were impaired (Yamasaki et al., 2009). Malassezia are normal skin commensals, although they can contribute to the inflammatory response associated with atopic disease and psoriasis. Dectin-2 is also important in the host response to Malassezia, although the two CLRs recognize distinct ligands (Ishikawa et al., 2013). Mincle recognizes a hydrophobic glycero-glycolipid, whereas Dectin-2 recognizes a hydrophilic, mannobiose-rich glycoprotein.

Mincle has also been implicated in recognition of Fonsecaea pedrosoi, a fungus that causes the chronic skin disease chromoblastomycosis, and Mincle deficiency is associated with impaired activation of murine macrophages (de Sousa et al., 2011). The fungus is poorly recognized by TLRs, leading the authors to hypothesize that disease is promoted by the lack of CLR-TLR co-stimulation. In support of this, de Sousa et al. (2011) have found that activating TLRs during F. pedrosoi infection in mice resulted in Mincle- and TLR-dependent clearance of the fungus. A pilot study in humans suggests that this is a promising approach to treatment of chromoblastomycosis (de Sousa et al., 2014). In contrast to this interpretation, Wevers et al. (2014) has observed that Mincle signaling in response to Fonsecaea monophora inhibits TLR- and Dectin-1-dependent IL-12 production in human dendritic cells through a mechanism requiring an E3 ligase that degrades the IRF1 transcription factor required for IL-12 transcription. This observation suggests that Mincle signaling might be exploited by the organism to impair development of protective Th1-cell-mediated responses. However, a more recent study has shown that Th1-cell-mediated responses are not affected by Mincle deletion (Wüthrich et al., 2015); these investigators also showed that Th17-cell-associated responses to F. pedrosoi are dependent on Dectin-2, but not Mincle. Given that Mincle, Dectin-1, and Dectin-2 all activate the Syk-CARD9-Bcl1-Malt1 pathway, it is not clear why the receptors appear to signal differently or even antagonistically to each other. Detailed analysis of CLR signaling pathways is clearly required to understand these apparently conflicting findings.

An additional controversy in this field are the reports that _Clec4d_−/− mice show no apparent phenotype when infected with Candida albicans in one study but were found to be highly susceptible to C. albicans in another (Graham et al., 2012; Zhu et al., 2013). The latter finding might be more consistent with the identification of yeast α-mannan as a ligand for this CLR (Zhu et al., 2013). The difference between these studies might be due to the inoculum, with a lower infectious dose resulting in increased susceptibility of the _Clec4d_−/− mice. Alternatively, as was eventually shown for Dectin-1, the difference might be dependent on the C. albicans strains used in the two studies. Other CLR family members, including CLEC1, CLEC2, and CLEC9A, are reviewed elsewhere (Hardison and Brown, 2012; Kerscher et al., 2013; Sancho and Reis e Sousa, 2012), although these CLRs are not currently implicated in fungal recognition.

MCL expressed on the surface of RAW264 macrophages was initially reported to be monomeric, did not immunoprecipitate with FcRγ, and did not recruit Syk upon stimulation (Graham et al., 2012). Another study found that MCL interacts with FcRγ in rat myeloid cells but not in transfected non-myeloid cells, suggesting that the interaction is indirect (Lobato-Pascual et al., 2013a). However, subsequent studies have shown that MCL-FcRγ interaction and signaling requires Mincle and formation of MCL-Mincle heterodimers (Lobato-Pascual et al., 2013b). The indirect interaction of FcRγ with MCL is supported by the finding that MCL lacks the canonical motif (a positively charged amino acid in the transmembrane region) to bind adaptor molecules, and the authors conclude that rat Mincle and MCL form covalent, disulfide-linked heterodimers at the cell surface.

In contrast, Miyake and co-workers have shown by co-transfection studies that MCL can interact with FcRγ in the absence of Mincle (Miyake et al., 2013). The investigators have shown by site-specific mutagenesis that FcRγ binding is dependent on the hydrophilic nature of threonine 38, corresponding to the charged arginine at this site in Mincle. These findings remain consistent with Mincle (MCL) heterodimer formation and enhanced MCL-FcRγ signaling; however, whether the interaction is direct or indirect might await the crystal structure of the heterodimer together with FcRγ.

Lin and colleagues have shown that MCL (referred to as Dectin-3) induces expression of Mincle after stimulation with TDM and that this is dependent on NF-κB (Zhao et al., 2014). This finding could indicate that MCL interacts sufficiently with FcRγ to allow signaling, and the group has found no evidence for MCL heterodimerization with Mincle. The group did, however, show that MCL forms heterodimers with Dectin-2 in transfected RAW264 cells and in bone-marrow-derived macrophages, resulting in enhanced responses to α-mannan and C. albicans hyphae (Zhu et al., 2013). This study used transfected HEK cells and re-natured proteins to show that although MCL and Dectin-2 could form homodimers, heterodimer formation facilitated higher sensitivity to α-mannan and induced stronger signaling.

Taken together, even though there is disagreement in the literature, evidence that MCL forms heterodimers with other CLRs to enhance signaling is compelling. It is also consistent with the theme set by other pathogen-recognition molecules that form heterodimers such as TLR2-TLR1 and TLR2-TLR6, resulting in differential recognition of bacterial glycolipids (Pandey et al., 2015). Whether heterodimer formation results in recognition of additional fungal cell wall or other components or increased sensitivity to known targets has yet to be determined.

Role of CLRs in Adaptive Immunity

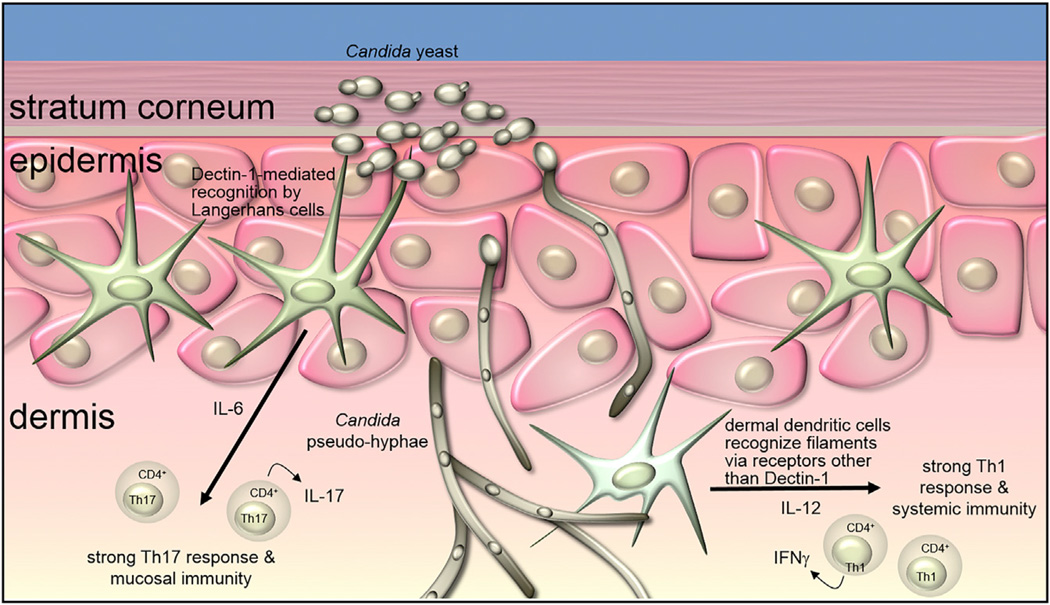

Dendritic cell populations have an important role in activating and instructing the adaptive immune response during fungal infections. The role depends on the receptors engaged, the immune cells involved, and the morphological form of the fungus. An example of this comes from recent work on the immune response to skin infection with Candida albicans. The skin is home to at least three types of dendritic cells, including Langerhans cells in the epidermis and CD11b− and CD11b+ dendritic cells in the underlying dermis. After infection with C. albicans, the yeast and pseudo-hyphal forms are present in the epidermis. Yeast are recognized by Dectin-1 on Langerhans cells, which triggers IL-6 production and polarization of a predominantly Th17 cell-mediated response that promotes protection from further skin infection (Figure 2; Kashem et al., 2015). Pseudo-hyphae, which have a cell wall composition that is distinct from yeast, penetrate into the deeper layers of the dermis. This form is not recognized by Dectin-1 (Gantner et al., 2005), and thus dendritic cells in the dermis engage Candida without significant involvement of Dectin-1, leading to polarization of a predominantly Th1 cell response and protection from systemic, but not mucosal, infection (Kashem et al., 2015). The role for Dectin-1 is supported by the observation that the Th17-cell-mediated response can be restored by direct injection of β-glucan into the dermis (Kashem et al., 2015). Strain differences have been reported to affect how different innate immune receptors engage C. albicans yeast and hyphae, and it will be interesting to see whether this model holds up generally.

Figure 2. Distinct T Cell Responses Based on Dendritic Cell Recognition of Candida Yeast Versus Pseudo-hyphae.

β-glucan exposed on the surface of Candida yeast in the epidermis is recognized by Dectin-1 on Langerhans cells, inducing production of IL-6 and the generation of a Th17-dominated adaptive immune response that is effective against reinfection of the skin. In contrast, Candida pseudo-hyphae penetrated into the deeper layers of the skin. These filaments expose little or no β-glucan and are recognized by dendritic cells in the dermis by receptors other than Dectin-1. This recognition translates into a more Th1 cell-dominated response that is effective against systemic infection with Candida. Diagram based on Kashem et al. (2015).

Dendritic cells are important for innate and adaptive responses to systemic Candida infection. Dectin-2 is important for dendritic cell production of IL-1β and IL-23 in response to C. albicans, and Dectin-2-deficient mice have an impaired ability to induce Th17 cell development during systemic Candida infection (Robinson et al., 2009; Saijo et al., 2010). Dendritic cells also play an unexpectedly important role prior to development of T cell responses. As noted above, Syk is generally required for signaling by C-type lectins, and mice lacking Syk in CD11c+ dendritic cells exhibit impaired IL-23 production during systemic candidiasis (Whitney et al., 2014). This Dectin-2- and Syk-mediated IL-23 secretion is necessary to stimulate NK cells to produce GMCSF, which is required to activate neutrophils to kill Candida.

Key Cytokines Involved in Antifungal Immunity

Although fungal infections result in immune responses that are associated with multiple cytokines, mutations affecting IL-1β or IL-17A are associated with increased susceptibility to infection, primarily by reducing activation of resident cells to produce CXC chemokines, which recruit neutrophils to the site of infection. These cytokines are also non-redundant in murine models of fungal disease and are the subjects of intense investigation.

_Il1b_−/− mice are highly susceptible to infection with yeast and filamentous fungi, and although there are multiple situations in which IL-1β cleavage is inflammasome independent as described in a recent review (Netea et al., 2015), mice deficient in inflammasome proteins NLRP3, NLRC4, ASC, or caspase-1 have an impaired ability to control Candida infections (Gross et al., 2009; Hise et al., 2009; Tomalka et al., 2011). Adoptive transfer studies in oral candidiasis have shown that NLRP3 primarily functions in myeloid cells, whereas NLRC4 activity is required in stromal cells. Control of Paracoccidiodes braziliensis in the lungs also requires NLRP3 and caspase-1, although infection is regulated more by IL-18 (also processed by inflammasomes) than by IL-1β (Ketelut-Carneiro et al., 2015).

In the canonical inflammasome pathway, caspase-1 cleaves the pro-form of IL-1β (reviewed in Netea et al., 2015); however, there is also a non-canonical, caspase-8 pathway that cleaves IL-1β in response to C. albicans in dendritic cells (Ganesan et al., 2014; Gringhuis et al., 2012). Gringhuis et al. (2012) reported that in human dendritic cells, caspase-8 activation is triggered by Dectin-1 and signals through Syk to form the BCL10-CARD9-Malt1 scaffold followed by production of pro-IL-1β; however, instead of forming the NLRP3 inflammasome, these investigators present evidence that caspase-8 and ASC are recruited to the BCL10-CARD9-Malt1 scaffold, where caspase-8 cleaves pro-IL-1β. In a second study, Ganesan et al. (2014) have shown that _C. albicans_-infected _Casp8_−/−_Ripk3_−/− mice and stimulated bone-marrow-derived dendritic cells produced less mature IL-1β than _Ripk3_−/− mice (_Casp8_−/− mice are embryonic lethal), thereby also showing a role for caspase-8 in production of IL-1β. However, these investigators reported that IL-1β processing was also dependent on NLRP3 and caspase-1. Other studies have shown a role for caspase-8 in IL-1β cleavage in the context of the NLRP3 inflammasome, most recently by Antonopoulos et al. (2015), who show that caspase-8 can mediate IL-1β cleavage and pyroptotic cell death in dendritic cells. The role for caspase-8 in the NLRP3 inflammasome and the BCL10-CARD9-Malt1-ASC scaffold is consistent with the exposed pyridine (PYR) domains on ASC that can bind the PYR domains of caspase-8; however, the molecular interactions between ASC and this scaffold have yet to be identified. In another non-canonical pathway, Aspergillus has been reported to induce formation of a hybrid NLRP3 with the AIM2 inflammasome, which recognizes double-stranded DNA (Karki et al., 2015). Although the basis for formation of this hybrid inflammasome is not clear, both caspase-1 and caspase-8 are required to cleave IL-1β and IL-18 and to clear the growing fungi in vitro in a mouse model of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (Karki et al., 2015).

These findings demonstrate the complexity of inflammasome regulation and hint at potential targets for therapy. To this end, injection of IL-37, an IL-1 family member with anti-inflammatory activity, inhibits the severity of Aspergillus infection of cystic fibrosis mice by blocking NLRP3 activity and neutrophil infiltration to infected lungs (Moretti et al., 2014). It is also worth noting that all the in vitro studies cited above examine inflammasomes in macrophages and dendritic cells. However, although it is understood that neutrophils use serine proteases to cleave pro-IL-1β (Netea et al., 2015), there is a growing body of work showing that neutrophils express and utilize the NLRP3 and NLRC4 inflammasomes to cleave IL-1β. In contrast to many reports focused on other myeloid cells, activation of caspase-1 does not result in apoptosis of neutrophils in bacterial infections (Chen et al., 2014; Cho et al., 2012; Karmakar et al., 2015). Given that these cells are generally the first cells recruited to infected tissues and infiltrate in large numbers, these findings have implications for understanding the development and maintenance of the inflammatory response to fungal infections.

Mice with deletions in either IL17a or IL17ra receptor are more susceptible to mucosal (oropharyngeal) and systemic candidiasis (Conti and Gaffen, 2015; Conti et al., 2009; Huang et al., 2004; Saijo et al., 2010). IL-17 is also important in murine models of C. albicans corneal infections, pulmonary aspergillosis and histoplasmosis (Deepe and Gibbons, 2009; Werner et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2013), and protective immunity in corneal infections with Aspergillus or Fusarium after systemic immunization (Taylor et al., 2014a). Similarly, re-challenge of tongues in the oropharyngeal candidiasis model results in increased Th17 cells in draining lymph nodes and enhanced fungal clearance (Hernández-Santos et al., 2013). IL-17 acts primarily on non-hematopoietic cells such as fibroblasts and epithelial cells that constitutively express the IL-17RA and IL-17RC heterodimeric receptor to promote recruitment of monocytes and neutrophils to sites of inflammation. IL-17 receptor signaling involves recruitment of the Act1 adaptor molecule and activation of canonical NF-κB pathway leading to transcription of CXC chemokines, which are important for recruitment of neutrophils to sites of infection, and CCL20, which recruits CCR6-expressing Th17- and IL-17-producing γδ T cells (Gaffen et al., 2014).

A recent review discusses the cytokine requirements for generating Th17- and other IL-17-producing lymphoid cells (Gaffen et al., 2014). In brief, development of IL-17-producing lymphoid cells is dependent on coordinated activity of IL-1 (α or β), IL-6, IL-23, and transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), although the precise roles of these cytokines in development of human Th17 cells have yet to be determined. The major transcription factor for Il17a in lymphoid cells is RORγt, as shown by the fact that inhibition or deletion results in impaired formation of IL-17-producing cells. The Th17 cell lineage also depends on the functions of STAT3, IRF4, BATF, and JUNB, with the latter two factors governing accessibility of RORγt to the promoter regions of Th17-cell-associated genes including Il21 and Il22 (Gaffen et al., 2014). These cytokine and transcriptional activities are required for Th0 cells to express IL-23 receptors and RORγt and to develop into fully functional Th17 cells, which are a major source of IL-17 in the Candida and Aspergillus infections described above.

The source of IL-17 at early time points (within 1–2 days of fungal infection) is controversial. In contrast to CD4+ T cells, lymphoid cells involved in innate immunity, including γδ T cells, iNKT cells, and innate lymphoid cells (ILC3), constitutively express IL-23 receptors and RORγt and are activated by cytokines and pathogen-recognition molecules (Cua and Tato, 2010; Sutton et al., 2012). Gaffen and co-workers have reported that γδ T cells and natural (n)Th17 cells are the early source of IL-17 during Candida infection of the tongue, with no role for innate lymphoid cells (nTh17 express TCR, CD3, and CD4). They have shown that _Rag1_−/− and other mice that do not express TCR have no IL-17 cells in infected tongues (Conti et al., 2014). In contrast, LeibundGut-Landmann and coworkers have shown that IL-17 production in _Tcrd_−/−, _Cd1d_−/−, or MHC Class II-deficient mice was unaffected during Candida infection, whereas tongues from infected _Rag1_−/− mice depleted of CD90+ ILCs have reduced IL-17 and impaired fungal clearance (Gladiator et al., 2013). Both groups reported a non-redundant role for IL-23 (Hernández-Santos et al., 2013), but the issue of which population of lymphoid cells is regulated has yet to be resolved.

Neutrophils have been reported as a source of IL-17 in addition to Th17 cells in pulmonary aspergillosis and histoplasmosis (Werner et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2013). Neutrophils are also an important source of IL-17 in infected tissues prior to recruitment of Th17 cells in Aspergillus and Fusarium corneal infections (Aspergillus and Fusarium species are important causes of corneal ulcers in the USA and worldwide). However, IL-17-producing neutrophils are only detected in mice that have been immunized prior to infection (Taylor et al., 2014a). Although neutrophils infiltrate _Candida_-infected tongues, IL-17-producing neutrophils are not detected in single-challenged animals. Th17 cells are elevated in draining nodes after re-challenge (Hernández-Santos et al., 2013), although the source of IL-17 in infected tongues was not examined.

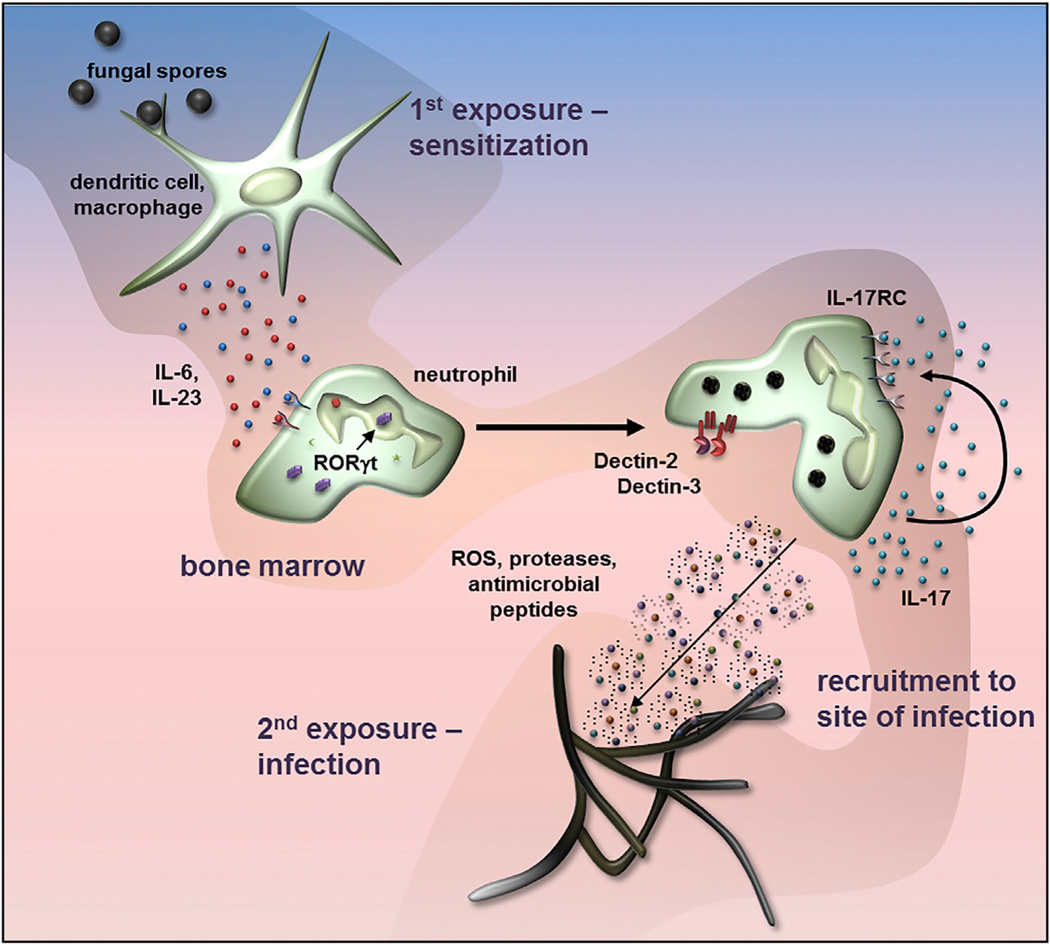

Taylor and co-workers have subsequently demonstrated that IL-17-producing neutrophils are generated in the bone marrow 72 hr after sensitization with killed, swollen conidia, and was independent of CD4+ and other lymphoid cells (Figure 3) (Taylor et al., 2014b). This study also has shown that Il17 expression is dependent on IL-6 and IL-23, but not IL-1β or TGF-β in highly purified bone marrow and human peripheral blood neutrophils. Similar to innate lymphoid cells, a sub-population of human and murine neutrophils constitutively expresses IL-23R and RORγt, and after cytokine stimulation, RORγt migrates from the cytoplasm to the nucleus and is required for Il17a gene expression. Wu et al. has also shown that IL-23 induces Il17a expression in isolated peritoneal neutrophils (Wu et al., 2013).

Figure 3. Autocrine Activity of Neutrophil IL-17 in Fungal Infections.

Exposure of macrophages and dendritic cells to germinating spores or yeast induces production of IL-6 and IL-23, which activate a sub-population of bone marrow neutrophils that constitutively express IL-6 and IL-23 receptors on the cell surface and the RORγt transcription factor in the cytoplasm. RORγt translocates to the nucleus to initiate IL-17 gene expression. IL-6 and IL-23 also induce expression of cell surface IL-17RC, and as IL-17RA is constitutively expressed, neutrophils can be activated by autocrine or paracrine IL-17. These activated neutrophils also express Dectin-2 and Dectin-3 (MCL), and subsequent exposure to hyphae results in increased production of reactive oxygen species that promotes fungal killing. Diagram based on Taylor et al. (2014b).

IL-6 and IL-23 stimulate expression of the IL-17RC receptor in neutrophils, and as they constitutively express IL-17RA, these cells respond to autocrine or paracrine IL-17 by producing higher amounts of ROS than unstimulated neutrophils. They consequently exhibit increased fungal killing in vitro and in an adoptive transfer model of fungal keratitis (Taylor et al., 2014b). This neutrophil population also expresses Dectin-2, which, when incubated with Aspergillus, leads to increased IL-17RC expression. IL-17-producing neutrophils are detected in the peripheral blood of corneal ulcer patients and healthy individuals who are exposed to high numbers of airborne spores (Karthikeyan et al., 2015).

Overall, the observation that neutrophils both produce and respond to IL-17 adds to the paradigm that IL-17 regulation of neutrophils is indirect (lymphoid cell-derived IL-17 activates receptors on epithelial cell to produce CXC chemokines). Given these findings, it seems likely that IL-17-producing neutrophils would be detected in other fungal infections where IL-6 and IL-23 are elevated.

Effector Mechanisms in Fungal Infections

Neutrophil depletion studies clearly demonstrate that these cells have an essential role in fungal killing (Huppler et al., 2014; Taylor et al., 2014a). Mediators include NADPH oxidase-derived reactive oxygen species and anti-microbial peptides such as calprotectin, which mediates killing of Candida and Aspergillus, primarily by sequestering zinc and manganese (Clark et al., 2016; Urban et al., 2009). Neutrophils also release proteolytic enzymes including elastase and gelatinase, which alter tissue structure to prevent dissemination but can also cause collateral tissue damage. Release of these mediators frequently occurs in the context of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), which are generated following elastase translocation to the nucleus, chromatin de-condensation and release of nuclear DNA and histones (for an excellent review on NETs, see Brinkmann and Zychlinsky, 2012). Fungi trigger NET formation and can be killed by NETs; however, this appears to be in response to larger hyphae rather than individual yeasts, which are phagocytosed (Branzk et al., 2014). These investigators also reported that blockade of Dectin-1 and phagocytosis results in increased NET formation by enabling elastase to translocate to the nucleus.

Although commonly associated with allergy, Th2 cell-mediated responses, and protection from multicellular parasites, eosinophils might play an important role in host defense against some fungi. Mice lacking the transcription factor GATA1 are specifically deficient in eosinophils, and Lilly et al. recently has observed that these animals are highly susceptible to acute Aspergillus infection in the lung (Lilly et al., 2014). When infected, these mice do not have any defect in recruitment of neutrophils, macrophages, or dendritic cells to the lungs, suggesting that eosinophils play a non-redundant role in host defense. Although the authors have observed that eosinophils and eosinophil extracts (likely granule contents) can kill Aspergillus, it is not clear how this relates to the essential role for eosinophils relative to other phagocytes that can engage the fungus. A similar role for eosinophils has been reported for longer-term Pneumocystis murina infection of the mouse lung (Eddens et al., 2015), but whether eosinophils are important for effective anti-fungal host defense at other sites is currently unknown.

Natural killer (NK) cells are cytotoxic lymphocytes primarily implicated in viral infections and anti-tumor immunity. However, NK cells also recognize fungi, and the NKp30 activating receptor mediates NK cell recognition and antimicrobial activity against C. neoformans and C. albicans by inducing perforin degranulation (Li et al., 2013). These investigators also have shown reduced NKp30 expression in HIV-infected individuals, resulting in less perforin release and impaired killing of C. neoformans.

Inflammatory monocytes are circulating CCR2+ monocytes that are rapidly recruited to sites of infection and produce inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Espinosa et al. have observed that specific depletion of inflammatory monocytes causes mice to become susceptible to lung infection with Aspergillus fumigatus (Espinosa et al., 2014). These inflammatory monocytes, and a population of monocyte-derived dendritic cells, are not required for orchestrating neutrophil recruitment as might have been expected, but are necessary for activating neutrophils for killing, and for killing fungi themselves by production of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. These effects appear to be mediated, at least in part, through a role for inflammatory monocytes as regulators of IL-1α and CXCL1 expression (Caffrey et al., 2015). Inflammatory monocytes are also critical for host defense against systemic Candida infection where the cells are necessary for early protection of the kidneys and brain (Ngo et al., 2014).

Although epithelial cells generally do not express CLRs and do not directly respond to fungi, they express functional receptors for a number of cytokines including IL-17A. IL-17 activation of epithelial cells induces IL-8 and other neutrophil chemokines, but also stimulates production of anti-microbial peptides such as beta defensins, which contribute to fungal killing without input from neutrophils (Trautwein-Weidner et al., 2015).

When myeloid phagocytes contact fungi, they produce inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, produce reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, degranulate where applicable, and internalize the organisms via phagocytosis where possible. Fungi in phagosomes are killed by reactive oxygen species and proteolytic enzymes, and antigens are harvested for instruction of the adaptive immune response. The nature of the phagocytic process is directed by the types of receptors engaged. Dectin-1 is the primary non-opsonic receptor for phagocytosis of fungi (it is currently not clear to what extent other C-type lectin receptors can trigger phagocytosis). The machinery involved in autophagy (e.g., LC3, Atg5) also associates with traditional phagosomes formed by activating Dectin-1, but not with phagosomes containing latex beads (Ma et al., 2012; Tam et al., 2014). This phenomenon termed “LC3-associated phagocytosis” is likely involved in determining the activity of the phagosomal compartment (Martinez et al., 2011; Sanjuan et al., 2007). Indeed, LC3-associated phagosomes acquire LAMP-1, a lysosomal marker, faster than phagosomes without LC3, MHCII-restricted antigens are processed more efficiently from LC3-associated phagosomes, and Candida are killed more efficiently when LC3 is present (Ma et al., 2012; Tam et al., 2014). LC3 likely promotes phagosome maturation in part through the recruitment of the membrane trafficking regulator FYCO1 (Ma et al., 2014). In related work, at least one report has suggested that Candida strains that largely obscure the β-glucan layer recognized by Dectin-1 are internalized by macrophages, but the phagosomes containing these organisms mature more slowly than if the yeast are manipulated to expose more β-glucan (Bain et al., 2014). The consequences of these processes on infection or development of lasting protective immunity have not yet been evaluated.

The Effect of the Fungal Microbiome on Immunity and Disease

The role of commensal fungi on health and disease is an emerging area of interest. Just as bacterial communities are widely reported to inhabit niches in the gut, mouth, skin, and lungs and to influence immune responses, so too do fungi. Studies on the “microbiome” typically do not include fungi, and are thereby missing potentially important contributors. Recent studies have begun to characterize the mycobiome and examine its effect on immunity and inflammation.

The first culture-independent high-throughput rDNA sequencing- based study to evaluate the oral mycobiome identified > 80 genera of fungi and found that Candida and Cladosporium were the most abundant in healthy individuals (Ghannoum et al., 2010). A subsequent oral mycobiome study by this group showed that HIV patients had a higher frequency of C. albicans compared with uninfected individuals, which is consistent with the increased prevalence of oral Candida (and other) infections in HIV patients. Further analysis suggested that Candida and Pichia species are antagonistic in this environment, with Pichia limiting Candida growth, an observation they confirmed using a murine model of oral candidiasis (Mukherjee et al., 2014). A subsequent analysis of these data has identified similar, but not identical fungi (Dupuy et al., 2014). However, as fungal nomenclature and rDNA taxonomy are often conflicting, and tools and approaches for fungal rDNA sequence analysis are still being developed, data from fungal mycobiome studies should be interpreted cautiously and subject to careful verification.

Fungi are normal commensals of the mammalian intestines, although how they interact with the immune system under normal physiological conditions has yet to be determined. The mouse gut is home to several common fungi including Candida, Saccharomyces, and Cladosporium species, and > 50 less-common genera (Dollive et al., 2013; Iliev et al., 2012). Fungal populations in the mouse gut have been observed to be variable over several months, whereas the intestinal bacterial community remains relatively stable (Dollive et al., 2013). How these findings affect the host response in the gut is not yet known. However, Iliev et al. have reported that a polymorphism in the human gene for Dectin-1 correlates with disease severity in ulcerative colitis patients and that DSS-induced colitis is more severe in _Candida_-colonized mice lacking Dectin-1 (Iliev et al., 2012). Further, a recent study has shown that Dectin-1 is important in driving and maintaining CD4+ T cell responses following intestinal challenge with Candida (Drummond et al., 2015). Therefore intestinal inflammatory diseases might be influenced by the mycobiome in the gut.

Whether Dectin-1 influences colonization of the gut with fungi such as Candida is not yet clear. The presence of a defective allele of Dectin-1 has been found in one patient cohort to be associated with intestinal colonization with Candida, at least in allogeneic stem cell transplant patients (van der Velden et al., 2013). However, the presence of Dectin-1 (as well as IL-1β and IL-17) does not influence intestinal C. albicans colonization in a mouse model (Vautier et al., 2015; Vautier et al., 2012). In the gut, C. albicans exists in a morphological state (GUT, gastrointestinally induced transition) that is distinct from the common yeast or hyphal forms (Pande et al., 2013), although how this form interacts with the host immune response has yet to be determined.

Systemic C. albicans infections are thought to derive from commensal populations in the intestines (Miranda et al., 2009). Although not understood, intestinal Candida likely modulate the host response systemically either through immune cell interactions in the gut or by production of fungal metabolites. Oral antibiotics kill gut bacteria, resulting in greatly elevated numbers of Candida in the intestines, which has been shown to promote lung inflammation in a murine model of allergy (Noverr et al., 2005; Noverr et al., 2004). Candida species (as well as many other fungi) can convert host arachidonic acid into prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), a potent immunomodulator (Noverr et al., 2001). One study suggests that the PGE2 generated by yeast enzymes reaches the lungs and influences lung macrophages (Kim et al., 2014). Whether diverse types of fungi other than Candida in the gut impact infection and immunity in similar ways has yet to be explored.

The skin is home to a commensal population of fungi dominated by lipid-dependent fungi of the Malassezia genus (Findley et al., 2013; Roth and James, 1988). Malassezia are also associated with several diseases such as seborrheic dermatitis, tinea versicolor, folliculitis, atopic dermatitis, and scalp conditions such as dandruff. Although Dectin-2 and Mincle recognize Malassezia, it is not known if the host immune system interacts with commensal Malassezia. Patients exhibiting skin disease as a result of mutations in STAT3, DOCK8, or WASL (Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome) had increased fungal diversity and numbers of Candida and Aspergillus species in the skin (Oh et al., 2013). A related study reports that non-Malassezia fungal microbiota diversity is increased in patients with atopic dermatitis, including increases in Candida, Cryptococcus, and Cladosporium species (Zhang et al., 2011). Therefore, changes in the skin mycobiome increase the potential for colonization with pathogenic fungi.

Concluding Remarks

In this review, we have focused on recent advances on the effects of the host response on pathogenic fungi, and conversely, the effect of resident fungi on the host response. Given that these are rapidly developing areas of research, it is not surprising that there are unresolved issues and conflicting data. In highlighting these points, we also acknowledge that many of these areas of interest also have implications for other microbial infections and for autoimmune disease. As noted, CLRs and CLR signaling are also important in mycobacterial disease, and IL-17 is a pro-inflammatory cytokine that is implicated in several autoimmune disease, including psoriasis, where IL-17 is being targeted for therapy. Similarly, an improved understating of regulation of inflammasome activity and IL-1β secretion will likely have implications for the multiple diseases in which these mediators have been implicated. Finally, continuing studies on the role of the mycobiome, not only on IBD but on other microbial infections and autoimmune diseases, will lead to an increased understanding of the importance of this group of organisms in health and in disease.

REFERENCES

- Abdel-Rahman SM, Preuett BL. Genetic predictors of susceptibility to cutaneous fungal infections: a pilot genome wide association study to refine a candidate gene search. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2012;67:147–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad DS, Esmadi M, Steinmann WC. Idiopathic CD4 Lymphocytopenia: Spectrum of opportunistic infections, malignancies, and autoimmune diseases. Avicenna J. Med. 2013;3:37–47. doi: 10.4103/2231-0770.114121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aimanianda V, Bayry J, Bozza S, Kniemeyer O, Perruccio K, Elluru SR, Clavaud C, Paris S, Brakhage AA, Kaveri SV, et al. Surface hydrophobin prevents immune recognition of airborne fungal spores. Nature. 2009;460:1117–1121. doi: 10.1038/nature08264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonopoulos C, Russo HM, El Sanadi C, Martin BN, Li X, Kaiser WJ, Mocarski ES, Dubyak GR. Caspase-8 as an Effector and Regulator of NLRP3 Inflammasome Signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:20167–20184. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.652321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babula O, Lazdane G, Kroica J, Ledger WJ, Witkin SS. Relation between recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis, vaginal concentrations of mannose-binding lectin, and a mannose-binding lectin gene polymorphism in Latvian women. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2003;37:733–737. doi: 10.1086/377234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bain JM, Louw J, Lewis LE, Okai B, Walls CA, Ballou ER, Walker LA, Reid D, Munro CA, Brown AJ, et al. Candida albicans hypha formation and mannan masking of β-glucan inhibit macrophage phagosome maturation. MBio. 2014;5:e01874. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01874-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branzk N, Lubojemska A, Hardison SE, Wang Q, Gutierrez MG, Brown GD, Papayannopoulos V. Neutrophils sense microbe size and selectively release neutrophil extracellular traps in response to large pathogens. Nat. Immunol. 2014;15:1017–1025. doi: 10.1038/ni.2987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinkmann V, Zychlinsky A. Neutrophil extracellular traps: is immunity the second function of chromatin? J. Cell Biol. 2012;198:773–783. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201203170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GD, Gordon S. Immune recognition. A new receptor for beta-glucans. Nature. 2001;413:36–37. doi: 10.1038/35092620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GD, Denning DW, Gow NA, Levitz SM, Netea MG, White TC. Hidden killers: human fungal infections. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012;4:165rv13. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caffrey AK, Lehmann MM, Zickovich JM, Espinosa V, Shepardson KM, Watschke CP, Hilmer KM, Thammahong A, Barker BM, Rivera A, et al. IL-1α signaling is critical for leukocyte recruitment after pulmonary Aspergillus fumigatus challenge. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1004625. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrion SdeJ, Leal SM, Jr, Ghannoum MA, Aimanianda V, Latgé JP, Pearlman E. The RodA hydrophobin on Aspergillus fumigatus spores masks dectin-1- and dectin-2-dependent responses and enhances fungal survival in vivo. J. Immunol. 2013;191:2581–2588. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casadevall A, Pirofski LA. Immunoglobulins in defense, pathogenesis, and therapy of fungal diseases. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;11:447–456. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen KW, Groß CJ, Sotomayor FV, Stacey KJ, Tschopp J, Sweet MJ, Schroder K. The neutrophil NLRC4 inflammasome selectively promotes IL-1β maturation without pyroptosis during acute Salmonella challenge. Cell Rep. 2014;8:570–582. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark HL, Jhingran A, Sun Y, Vareechon C, Jesus Carrion Sd, Skaar EP, Chazin WJ, Calera JA, Hohl TM, Pearlman E. Zinc and Manganese Chelation by Neutrophil S100A8/A9 (Calprotectin) Limits Extracellular Aspergillus fumigatus Hyphal Growth and Corneal Infection. J. Immunol. 2016 doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1502037. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho JS, Guo Y, Ramos RI, Hebroni F, Plaisier SB, Xuan C, Granick JL, Matsushima H, Takashima A, Iwakura Y, et al. Neutrophil-derived IL-1β is sufficient for abscess formation in immunity against Staphylococcus aureus in mice. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1003047. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti HR, Gaffen SL. IL-17-Mediated Immunity to the Opportunistic Fungal Pathogen Candida albicans. J. Immunol. 2015;195:780–788. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti HR, Shen F, Nayyar N, Stocum E, Sun JN, Lindemann MJ, Ho AW, Hai JH, Yu JJ, Jung JW, et al. Th17 cells and IL-17 receptor signaling are essential for mucosal host defense against oral candidiasis. J. Exp. Med. 2009;206:299–311. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conti HR, Peterson AC, Brane L, Huppler AR, Hernández-Santos N, Whibley N, Garg AV, Simpson-Abelson MR, Gibson GA, Mamo AJ, et al. Oral-resident natural Th17 cells and γδ T cells control opportunistic Candida albicans infections. J. Exp. Med. 2014;211:2075–2084. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosdale DJ, Poulton KV, Ollier WE, Thomson W, Denning DW. Mannose-binding lectin gene polymorphisms as a susceptibility factor for chronic necrotizing pulmonary aspergillosis. J. Infect. Dis. 2001;184:653–656. doi: 10.1086/322791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cua DJ, Tato CM. Innate IL-17-producing cells: the sentinels of the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2010;10:479–489. doi: 10.1038/nri2800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha C, Aversa F, Lacerda JF, Busca A, Kurzai O, Grube M, Löffler J, Maertens JA, Bell AS, Inforzato A, et al. Genetic PTX3 deficiency and aspergillosis in stem-cell transplantation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;370:421–432. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dambuza IM, Brown GD. C-type lectins in immunity: recent developments. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2015;32:21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2014.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Luca A, Carvalho A, Cunha C, Iannitti RG, Pitzurra L, Giovannini G, Mencacci A, Bartolommei L, Moretti S, Massi-Benedetti C, et al. IL-22 and IDO1 affect immunity and tolerance to murine and human vaginal candidiasis. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003486. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Sousa MG, Reid DM, Schweighoffer E, Tybulewicz V, Ruland J, Langhorne J, Yamasaki S, Taylor PR, Almeida SR, Brown GD. Restoration of pattern recognition receptor costimulation to treat chromoblastomycosis, a chronic fungal infection of the skin. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;9:436–443. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Sousa MG, Belda W, Jr, Spina R, Lota PR, Valente NS, Brown GD, Criado PR, Benard G. Topical application of imiquimod as a treatment for chromoblastomycosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014;58:1734–1737. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deepe GS, Jr, Gibbons RS. Interleukins 17 and 23 influence the host response to Histoplasma capsulatum. J. Infect. Dis. 2009;200:142–151. doi: 10.1086/599333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Z, Ma S, Zhou H, Zang A, Fang Y, Li T, Shi H, Liu M, Du M, Taylor PR, et al. Tyrosine phosphatase SHP-2 mediates C-type lectin receptor-induced activation of the kinase Syk and anti-fungal TH17 responses. Nat. Immunol. 2015;16:642–652. doi: 10.1038/ni.3155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dollive S, Chen YY, Grunberg S, Bittinger K, Hoffmann C, Vandivier L, Cuff C, Lewis JD, Wu GD, Bushman FD. Fungi of the murine gut: episodic variation and proliferation during antibiotic treatment. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e71806. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drewniak A, Gazendam RP, Tool AT, van Houdt M, Jansen MH, van Hamme JL, van Leeuwen EM, Roos D, Scalais E, de Beaufort C, et al. Invasive fungal infection and impaired neutrophil killing in human CARD9 deficiency. Blood. 2013;121:2385–2392. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-08-450551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond RA, Brown GD. Signalling C-type lectins in antimicrobial immunity. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003417. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond RA, Dambuza IM, Vautier S, Taylor JA, Reid DM, Bain CC, Underhill DM, Masopust D, Kaplan DH, Brown GD. CD4(+) T-cell survival in the GI tract requires dectin-1 during fungal infection. Mucosal Immunol. 2015 doi: 10.1038/mi.2015.79. Published online September 9, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/mi.2015.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupuy AK, David MS, Li L, Heider TN, Peterson JD, Montano EA, Dongari-Bagtzoglou A, Diaz PI, Strausbaugh LD. Redefining the human oral mycobiome with improved practices in amplicon-based taxonomy: discovery of Malassezia as a prominent commensal. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e90899. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eddens T, Elsegeiny W, Nelson MP, Horne W, Campfield BT, Steele C, Kolls JK. Eosinophils Contribute to Early Clearance of Pneumocystis murina Infection. J. Immunol. 2015;195:185–193. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1403162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelhardt KR, McGhee S, Winkler S, Sassi A, Woellner C, Lopez-Herrera G, Chen A, Kim HS, Lloret MG, Schulze I, et al. Large deletions and point mutations involving the dedicator of cytokinesis 8 (DOCK8) in the autosomal-recessive form of hyper-IgE syndrome. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2009;124:1289–1302.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa V, Jhingran A, Dutta O, Kasahara S, Donnelly R, Du P, Rosenfeld J, Leiner I, Chen CC, Ron Y, et al. Inflammatory monocytes orchestrate innate antifungal immunity in the lung. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1003940. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falcone EL, Holland SM. Invasive fungal infection in chronic granulomatous disease: insights into pathogenesis and management. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 2012;25:658–669. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e328358b0a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferwerda B, Ferwerda G, Plantinga TS, Willment JA, van Spriel AB, Venselaar H, Elbers CC, Johnson MD, Cambi A, Huysamen C, et al. Human dectin-1 deficiency and mucocutaneous fungal infections. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:1760–1767. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0901053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findley K, Oh J, Yang J, Conlan S, Deming C, Meyer JA, Schoenfeld D, Nomicos E, Park M, Kong HH, Segre JA NIH Intramural Sequencing Center Comparative Sequencing Program. Topographic diversity of fungal and bacterial communities in human skin. Nature. 2013;498:367–370. doi: 10.1038/nature12171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaffen SL, Jain R, Garg AV, Cua DJ. The IL-23-IL-17 immune axis: from mechanisms to therapeutic testing. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2014;14:585–600. doi: 10.1038/nri3707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesan S, Rathinam VA, Bossaller L, Army K, Kaiser WJ, Mocarski ES, Dillon CP, Green DR, Mayadas TN, Levitz SM, et al. Caspase-8 modulates dectin-1 and complement receptor 3-driven IL-1β production in response to β-glucans and the fungal pathogen, Candida albicans. J. Immunol. 2014;193:2519–2530. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1400276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gantner BN, Simmons RM, Underhill DM. Dectin-1 mediates macrophage recognition of Candida albicans yeast but not filaments. EMBO J. 2005;24:1277–1286. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garred P, Larsen F, Seyfarth J, Fujita R, Madsen HO. Mannose-binding lectin and its genetic variants. Genes Immun. 2006;7:85–94. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geijtenbeek TB, Gringhuis SI. Signalling through C-type lectin receptors: shaping immune responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2009;9:465–479. doi: 10.1038/nri2569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gersuk GM, Underhill DM, Zhu L, Marr KA. Dectin-1 and TLRs permit macrophages to distinguish between different Aspergillus fumigatus cellular states. J. Immunol. 2006;176:3717–3724. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.6.3717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghannoum MA, Jurevic RJ, Mukherjee PK, Cui F, Sikaroodi M, Naqvi A, Gillevet PM. Characterization of the oral fungal microbiome (mycobiome) in healthy individuals. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000713. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladiator A, Wangler N, Trautwein-Weidner K, LeibundGut-Landmann S. Cutting edge: IL-17-secreting innate lymphoid cells are essential for host defense against fungal infection. J. Immunol. 2013;190:521–525. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glocker EO, Hennigs A, Nabavi M, Schäffer AA, Woellner C, Salzer U, Pfeifer D, Veelken H, Warnatz K, Tahami F, et al. A homozygous CARD9 mutation in a family with susceptibility to fungal infections. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;361:1727–1735. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodridge HS, Reyes CN, Becker CA, Katsumoto TR, Ma J, Wolf AJ, Bose N, Chan AS, Magee AS, Danielson ME, et al. Activation of the innate immune receptor Dectin-1 upon formation of a ‘phagocytic synapse’. Nature. 2011;472:471–475. doi: 10.1038/nature10071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham LM, Gupta V, Schafer G, Reid DM, Kimberg M, Dennehy KM, Hornsell WG, Guler R, Campanero-Rhodes MA, Palma AS, et al. The C-type lectin receptor CLECSF8 (CLEC4D) is expressed by myeloid cells and triggers cellular activation through Syk kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:25964–25974. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.384164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gringhuis SI, den Dunnen J, Litjens M, van der Vlist M, Wevers B, Bruijns SC, Geijtenbeek TB. Dectin-1 directs T helper cell differentiation by controlling noncanonical NF-kappaB activation through Raf-1 and Syk. Nat. Immunol. 2009;10:203–213. doi: 10.1038/ni.1692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gringhuis SI, Kaptein TM, Wevers BA, Theelen B, van der Vlist M, Boekhout T, Geijtenbeek TB. Dectin-1 is an extracellular pathogen sensor for the induction and processing of IL-1β via a noncanonical caspase-8 inflammasome. Nat. Immunol. 2012;13:246–254. doi: 10.1038/ni.2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross O, Poeck H, Bscheider M, Dostert C, Hannesschläger N, Endres S, Hartmann G, Tardivel A, Schweighoffer E, Tybulewicz V, et al. Syk kinase signalling couples to the Nlrp3 inflammasome for anti-fungal host defence. Nature. 2009;459:433–436. doi: 10.1038/nature07965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardison SE, Brown GD. C-type lectin receptors orchestrate antifungal immunity. Nat. Immunol. 2012;13:817–822. doi: 10.1038/ni.2369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havlickova B, Czaika VA, Friedrich M. Epidemiological trends in skin mycoses worldwide. Mycoses. 2008;51(Suppl 4):2–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2008.01606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Santos N, Huppler AR, Peterson AC, Khader SA, McKenna KC, Gaffen SL. Th17 cells confer long-term adaptive immunity to oral mucosal Candida albicans infections. Mucosal Immunol. 2013;6:900–910. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hise AG, Tomalka J, Ganesan S, Patel K, Hall BA, Brown GD, Fitzgerald KA. An essential role for the NLRP3 inflammasome in host defense against the human fungal pathogen Candida albicans. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:487–497. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohl TM, Van Epps HL, Rivera A, Morgan LA, Chen PL, Feldmesser M, Pamer EG. Aspergillus fumigatus triggers inflammatory responses by stage-specific beta-glucan display. PLoS Pathog. 2005;1:e30. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0010030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland SM, DeLeo FR, Elloumi HZ, Hsu AP, Uzel G, Brodsky N, Freeman AF, Demidowich A, Davis J, Turner ML, et al. STAT3 mutations in the hyper-IgE syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007;357:1608–1619. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W, Na L, Fidel PL, Schwarzenberger P. Requirement of interleukin-17A for systemic anti-Candida albicans host defense in mice. J. Infect. Dis. 2004;190:624–631. doi: 10.1086/422329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huppler AR, Conti HR, Hernández-Santos N, Darville T, Biswas PS, Gaffen SL. Role of neutrophils in IL-17-dependent immunity to mucosal candidiasis. J. Immunol. 2014;192:1745–1752. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ifrim DC, Bain JM, Reid DM, Oosting M, Verschueren I, Gow NA, van Krieken JH, Brown GD, Kullberg BJ, Joosten LA, et al. Role of Dectin-2 for host defense against systemic infection with Candida glabrata. Infect. Immun. 2014;82:1064–1073. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01189-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iliev ID, Funari VA, Taylor KD, Nguyen Q, Reyes CN, Strom SP, Brown J, Becker CA, Fleshner PR, Dubinsky M, et al. Interactions between commensal fungi and the C-type lectin receptor Dectin-1 influence colitis. Science. 2012;336:1314–1317. doi: 10.1126/science.1221789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa E, Ishikawa T, Morita YS, Toyonaga K, Yamada H, Takeuchi O, Kinoshita T, Akira S, Yoshikai Y, Yamasaki S. Direct recognition of the mycobacterial glycolipid, trehalose dimycolate, by C-type lectin Mincle. J. Exp. Med. 2009;206:2879–2888. doi: 10.1084/jem.20091750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishikawa T, Itoh F, Yoshida S, Saijo S, Matsuzawa T, Gonoi T, Saito T, Okawa Y, Shibata N, Miyamoto T, Yamasaki S. Identification of distinct ligands for the C-type lectin receptors Mincle and Dectin-2 in the pathogenic fungus Malassezia. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;13:477–488. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jhingran A, Kasahara S, Shepardson KM, Junecko BA, Heung LJ, Kumasaka DK, Knoblaugh SE, Lin X, Kazmierczak BI, Reinhart TA, et al. Compartment-specific and sequential role of MyD88 and CARD9 in chemokine induction and innate defense during respiratory fungal infection. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1004589. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karki R, Man SM, Malireddi RK, Gurung P, Vogel P, Lamkanfi M, Kanneganti TD. Concerted activation of the AIM2 and NLRP3 inflammasomes orchestrates host protection against Aspergillus infection. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17:357–368. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmakar M, Katsnelson M, Malak HA, Greene NG, Howell SJ, Hise AG, Camilli A, Kadioglu A, Dubyak GR, Pearlman E. Neutrophil IL-1β processing induced by pneumolysin is mediated by the NLRP3/ASC inflammasome and caspase-1 activation and is dependent on K+ efflux. J. Immunol. 2015;194:1763–1775. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karthikeyan RS, Vareechon C, Prajna NV, Dharmalingam K, Pearlman E, Lalitha P. Interleukin 17 expression in peripheral blood neutrophils from fungal keratitis patients and healthy cohorts in southern India. J. Infect. Dis. 2015;211:130–134. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashem SW, Igyártó BZ, Gerami-Nejad M, Kumamoto Y, Mohammed J, Jarrett E, Drummond RA, Zurawski SM, Zurawski G, Berman J, et al. Candida albicans morphology and dendritic cell subsets determine T helper cell differentiation. Immunity. 2015;42:356–366. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerscher B, Willment JA, Brown GD. The Dectin-2 family of C-type lectin-like receptors: an update. Int. Immunol. 2013;25:271–277. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxt006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketelut-Carneiro N, Silva GK, Rocha FA, Milanezi CM, Cavalcanti-Neto FF, Zamboni DS, Silva JS. IL-18 triggered by the Nlrp3 inflammasome induces host innate resistance in a pulmonary model of fungal infection. J. Immunol. 2015;194:4507–4517. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim YG, Udayanga KG, Totsuka N, Weinberg JB, Núñez G, Shibuya A. Gut dysbiosis promotes M2 macrophage polarization and allergic airway inflammation via fungi-induced PGE2. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V, Cheng SC, Johnson MD, Smeekens SP, Wojtowicz A, Giamarellos-Bourboulis E, Karjalainen J, Franke L, Withoff S, Plantinga TS, et al. Immunochip SNP array identifies novel genetic variants conferring susceptibility to candidaemia. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:4675. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanternier F, Cypowyj S, Picard C, Bustamante J, Lortholary O, Casanova JL, Puel A. Primary immunodeficiencies underlying fungal infections. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2013a;25:736–747. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanternier F, Pathan S, Vincent QB, Liu L, Cypowyj S, Prando C, Migaud M, Taibi L, Ammar-Khodja A, Boudghene Stambouli O, et al. Deep dermatophytosis and inherited CARD9 deficiency. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013b;369:1704–1714. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1208487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leal SM, Jr, Cowden S, Hsia YC, Ghannoum MA, Momany M, Pearlman E. Distinct roles for Dectin-1 and TLR4 in the pathogenesis of Aspergillus fumigatus keratitis. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000976. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]