Catechol-O-Methyltransferase Genotype and Dopamine Regulation in the Human Brain (original) (raw)

Abstract

A functional polymorphism in the gene for catechol-_O_-methyltransferase (COMT) has been shown to affect executive cognition and the physiology of the prefrontal cortex in humans, probably by affecting prefrontal dopamine signaling. The COMT valine allele, associated with relatively poor prefrontal function, is also a gene that may increase risk for schizophrenia. Although poor performance on executive cognitive tasks and abnormal prefrontal function are characteristics of schizophrenia, so is psychosis, which has been related to excessive presynaptic dopamine activity in the striatum. Studies in animals have shown that diminished prefrontal dopamine neurotransmission leads to upregulation of striatal dopamine activity. We measured tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) mRNA in mesencephalic dopamine neurons in human brain and found that the COMT valine allele is also associated with increased TH gene expression, especially in neuronal populations that project to the striatum. This indicates that COMT genotype is a heritable aspect of dopamine regulation and it further explicates the mechanism by which the COMT valine allele increases susceptibility for psychosis.

Keywords: catechol-_O_-methyltransferase, dopamine, tyrosine hydroxylase, human, genotype, midbrain, psychosis, schizophrenia

Introduction

Dopamine (DA) neurotransmission has been shown in both human and nonhuman primates to be critical for cognitive functions subserved by the prefrontal cortex (PFC), such as executive cognition and working memory (Sawaguchi and Goldman-Rakic, 1994; Williams and Goldman-Rakic, 1995). DA levels in the PFC are determined by DA biosynthesis and release and by the rate of diffusion, reuptake, and degradation. Breakdown may be particularly relevant to DA inactivation in the PFC in view of recent evidence that the DA transporter (DAT) is rarely expressed within synapses in this region (Lewis et al., 2001) and exerts minimal influence on DA flux (Mazei et al., 2002; Moron et al., 2002). Catechol-_O_-methyltransferase (COMT) is an important enzyme involved in the breakdown of DA and converts DA to 3-methoxytyramine and the DA metabolite dihydroxyphenylacetic acid to homovanilic acid (Boulton and Eisenhofer, 1998).

The human COMT gene contains a common functional polymorphism [a valine (val) substitution for methionine (met)] at the 158/108 locus in the peptide sequence. The met allele results in a heat-labile protein with a fourfold reduction in enzymatic activity (Mannisto and Kaakkola, 1999). Studies in peripheral blood and in liver indicate that this functional polymorphism accounts for most of the human variation in peripheral COMT activity. Therefore, COMT genotype might also contribute to differences in prefrontal function between individuals. Consistent with this prediction, Egan et al. (2001) reported in a large sample of subjects (n = 465) that COMT genotype is associated with variations in executive cognition and with PFC physiological activity during working memory, functions for which DA levels in the PFC are known to be important. As expected, met/met individuals had the best performance on executive cognition tasks, val/val individuals had the worst, and val/met individuals were intermediate. The effect of COMT genotype on cognitive function related to prefrontal cortex has been confirmed by other groups (Rosa et al., 2002; Malhotra et al., 2002; Bilder et al., 2003). The predicted effect of COMT genotype on prefrontal cortical physiology was demonstrated using functional magnetic resonance imagining during a working memory task (Egan et al., 2001). These findings, in conjunction with evidence of a regionally specific effect of COMT on PFC DA flux and on memory found in COMT knock-out mice (Gogos et al., 1998; Kneavel et al., 2000; Huotari et al., 2002), support the notion that COMT genotype affects DA neurotransmission in the PFC.

In addition to its role in normal cognition, DA neurotransmission in PFC has been implicated in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia (Weinberger, 1987; Weinberger et al., 1988; Akil et al., 1999). Patients with schizophrenia exhibit deficits in cognitive tasks that are dependent on the function of the PFC (Weinberger et al., 1986; Park and Holzman, 1992; Carter et al., 1998) and show abnormalities of prefrontal physiology during performance of such tasks (Weinberger et al., 1986, 1988; Carter et al., 1998; Callicott et al., 2000; Barch et al., 2001). Moreover, these functional abnormalities have been related to measures of cortical dopamine activity in vivo(Weinberger et al., 1988; Daniel et al., 1991; Okubo et al., 1997;Abi-Dargham et al., 2002), and evidence of abnormal dopaminergic innervation of PFC has been found in postmortem brains of patients with schizophrenia (Akil et al., 1999). Consistent with this evidence, inheritance of the val allele has been found in some family-based association studies to slightly increase risk for schizophrenia (Li et al., 1996, 2000; Kunugi et al., 1997; Egan et al., 2001), implicating COMT as a susceptibility gene for schizophrenia.

The mechanism by which inheritance of the COMT val allele increases risk for schizophrenia may be related to its impact on prefrontal DA levels and prefrontal function. However, DA neurotransmission in PFC has also been shown in experimental animals to affect subcortical DA activity, which is implicated in both the psychotic symptoms of schizophrenia (Carlsson, 1995; Grace, 2000; Laruelle, 2000) and the therapeutic response to anti-dopaminergic drugs (Deutch, 1993; Kinon and Lieberman, 1996). DA flux in PFC modulates the activity of excitatory cortical neurons that project both directly and indirectly to mesencephalic DA neurons (Haber and Fudge, 1997; Lu et al., 1997;Carr and Sesack, 2000). Recent evidence in the rodent indicates that, whereas prefrontal neurons make direct contacts with DA neurons that project back to PFC, prefrontal projections do not contact directly DA neurons projecting to the striatum. This has led to speculation that prefrontal neurons tonically inhibit striatal DA projections perhaps via GABA intermediates in the striatum or in the brainstem (Carr and Sesack, 2000; Carlsson, 2001). Under experimental conditions in animals, reduced DA signaling in the PFC leads to increased responsivity of subcortically projecting midbrain DA neurons to stimuli such as stress (Deutch, 1993, Kolachana et al., 1995; Harden et al., 1998). The notion that overactive populations of mesencephalic dopamine neurons might be a “downstream” effect of an abnormality in prefrontal function has been proposed as an explanation for the coexistence of both cortical and subcortical dopaminergic abnormalities in schizophrenia (Weinberger, 1987; Weinberger et al., 1988; Deutch 1993, Grace, 2000). Therefore, to the extent that COMT genotype affects prefrontal function, it may contribute risk for schizophrenia not only because of its biological effects at the level of PFC but also because of indirect downstream effects on DA regulation.

Because of this evidence that DA levels in the PFC and in the striatum may be inversely related, we hypothesized that inheritance of the val allele would affect the homeostasis of mesencephalic DA neurons in the normal human brain in a predictable direction. Thus, compared with the met allele, the val allele, which is likely associated with relatively diminished prefrontal DA signaling, would result in relatively increased disinhibition of mesencephalic DA activity, particularly in neuronal populations projecting to the striatum. To test this hypothesis, we compared mRNA levels of TH, the rate-limiting enzyme for dopamine biosynthesis, in dopamine neurons of postmortem human brain specimens from normal subjects with the val/val genotype and those with the val/met genotype.

Materials and Methods

Characteristics of subjects. Human brain specimens were obtained, during the course of routine autopsy, through the Office of the Medical Examiners of the District of Columbia with the informed consent of the next of kin. Twenty-three normal controls were included in this study. Ten cases with val/val genotype (seven males and three females) were compared with 13 cases of val/met genotypes (eight males and five females). All cases in the val/val group were African American compared with 10 African Americans and three Caucasians in the val/met group. Mean postmortem interval (PMI) is comparable between the two groups (31.0 ± 15.5 for val/val and 33.8 ± 17.5 for val/met), as is mean age (40.9 ± 14.9 for val/val and 49.9 ± 7.5 for val/met) and mean pH (6.42 ± 0.23 for val/val and 6.39 ± 022 for val/met). Clinical records were reviewed by two board-certified psychiatrists, and collateral information was obtained, whenever possible, from telephone interviews with surviving relatives of the deceased. Blood and/or brain toxicology screens were obtained in each case. We excluded subjects with known history of neurological disorders, psychiatric disorders, or substance abuse and all cases with prolonged agonal state. Each case was examined macroscopically and microscopically by an experienced neuropathologist. We also excluded cases with significant neuropathological abnormalities or cases that met criteria for Alzheimer's disease. Approximately 35% of all cases initially considered normal controls were eventually excluded from this study for these reasons. The collection of human brain specimens was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Institute of Mental Health Intramural Research Program.

Tissue specimens. In each case, the midbrain was cut into 1–2 cm blocks in a plane perpendicular to its long axis. Tissue blocks were frozen immediately in a mixture of dry ice and isopentane, cryostat sectioned at 14 μm, thaw mounted onto gelatin-coated microscope slides, then dried and stored at −80°C. Every 50th section was stained for Nissl substance with thionin. Anatomical levels corresponding to Figure 57 in the Atlas of the Human Brainstem by Paxinos and Huang (Paxinos, 1995) were identified in each case using Nissl-stained sections and TH immunocytochemistry. Regional boundaries of the DA cell groups within the midbrain were determined according to McRitchie and Halliday (1995). Five cell groups were identified: the substantia nigra pars lateralis (SNL), the dorsal and ventral tiers of the pars compacta (SND and SNV respectively), the paranigral nucleus (PN), and the ventral tegmental area (VTA). These nuclei were chosen because they could be reliably identified at this anatomical level. pH measures were conducted in each case using 500 mg of tissue homogenate from the cerebellum and a 420A Orion pH meter with a highly-sensitive glass pH SURE-FLOW electrode by Orion.

In situ hybridization. Tissue sections 14-μm-thick were hybridized with 35S-labeled riboprobes for TH, for the DAT, and for the house-keeping gene cyclophilin. We used a 545-bp-long riboprobe for human TH (Uhl et al., 1994) and a 350 bp riboprobe for human DAT (Joh et al., 1998). _In situ_hybridization for TH and DAT was performed as described previously (Little et al., 1998). Two to four tissue sections from each subject at the chosen anatomical level were included. To control for between-experiment variations, tissue sections from all subjects were always processed in the same experiment. Cyclophilin _in situ_hybridization was conducted using35S-labeled riboprobe for human cyclophilin 103 bp cDNA from exons 1 and 2 of the human gene (Ambion, Austin, TX) and the Whitfield method (Whitfield et al., 1990). After overnight hybridization at 60°C in humidified chambers, slides were placed in x-ray cassettes along with14C standards (American Radiolabeled Chemicals St. Louis, MO) and apposed to Kodak BioMax MR autoradiographic film (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY) for 4–20 d.

Quantitative analysis. Hybridization was quantified by measuring the optical density of the x-ray film with NIH Image software version 1.61. All quantitative analyses were conducted blind to genotype. We sampled five DA cell groups from each side (SNL, SND, SNV, PN, and the VTA). An area of 1.76 mm2 in each cell group was sampled selecting the region of highest density (Fig.1). Thus, from 20–40 measurements were taken from each case for TH and for DAT. The results from all sections and both sides were averaged to produce five mean measures (one for each cell group) per subject. Mean values from each cell group and a total (sum) of means of all five were used for statistical analyses. The data were analyzed using COMT genotype (two) by cell group (five) ANOVA on optical density measures of mean mRNA levels. In addition, ANCOVA including age, gender, pH, and PMI as individual covariates were also conducted. Post hoc analyses were performed when appropriate using the Tukey's honest significant difference test.

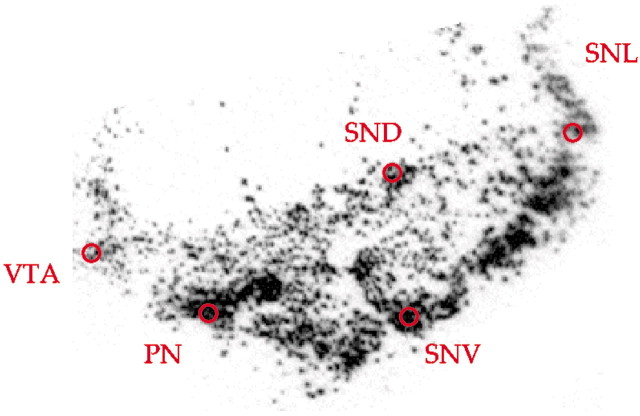

Fig. 1.

Illustration of the sampling procedure. Red circles indicate an area of 1.76 mm2 sampled in each of the five cell groups selecting the region of highest density.

Genetic analysis. Frozen tissue samples were collected from the cerebellum of all cases. DNA was extracted using standard methods. COMT val108/158met genotype was determined as a restriction fragment length polymorphism after PCR amplification and digestion with N1aIII as described previously (Egan et al., 2001). Of twenty-four brains originally genotyped, only one had a met/met genotype, which is not surprising considering the allele frequencies of the study population (Palmatier et al., 1999). This brain was excluded from additional analysis.

Results

We found a main effect of COMT genotype on TH mRNA levels expressed as a summed measure in all five of the mesencephalic DA cell groups (F = 5.63; df = 1, 22; p = 0.02; effect size = 0.9 d), and, as predicted, val/val cases had significantly greater expression than val/met cases (41.8% increase) (Fig. 2).

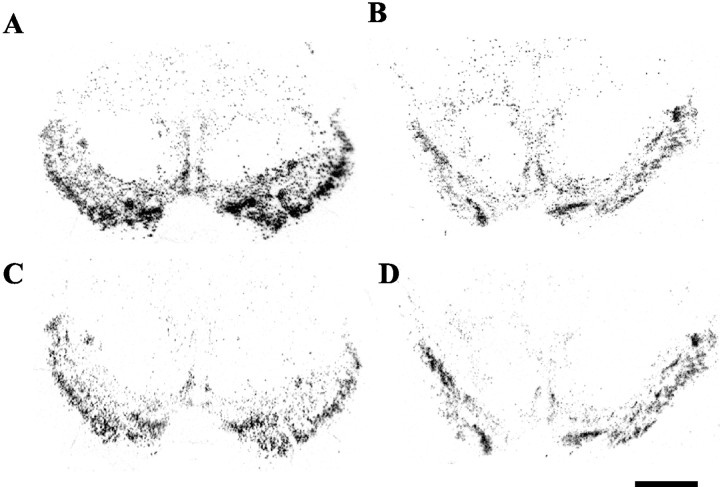

Fig. 2.

Autoradiograms of midbrain tissue sections after_in situ_ hybridization with radiolabeled riboprobes for TH (A, B) or DAT (C,D) mRNA in two matched cases with val/met (case 1193,A, C) or val/val (case 1111, B,D) genotypes, respectively. Scale bar, 1 mm

In an analysis of individual cell groups, significant main effects of genotype were found in the SNV (71.6% increase; F = 16.6; df = 1, 22; p = 0.0005) (Fig.3) and the SND (47.6% increase;F = 4.51; df = 1, 22; p = 0.04). None of the other cell groups showed significant differences, and covarying for factors such as age, gender, pH, or postmortem interval did not affect these results (all F values <2.18; all_p_ values >0.15).

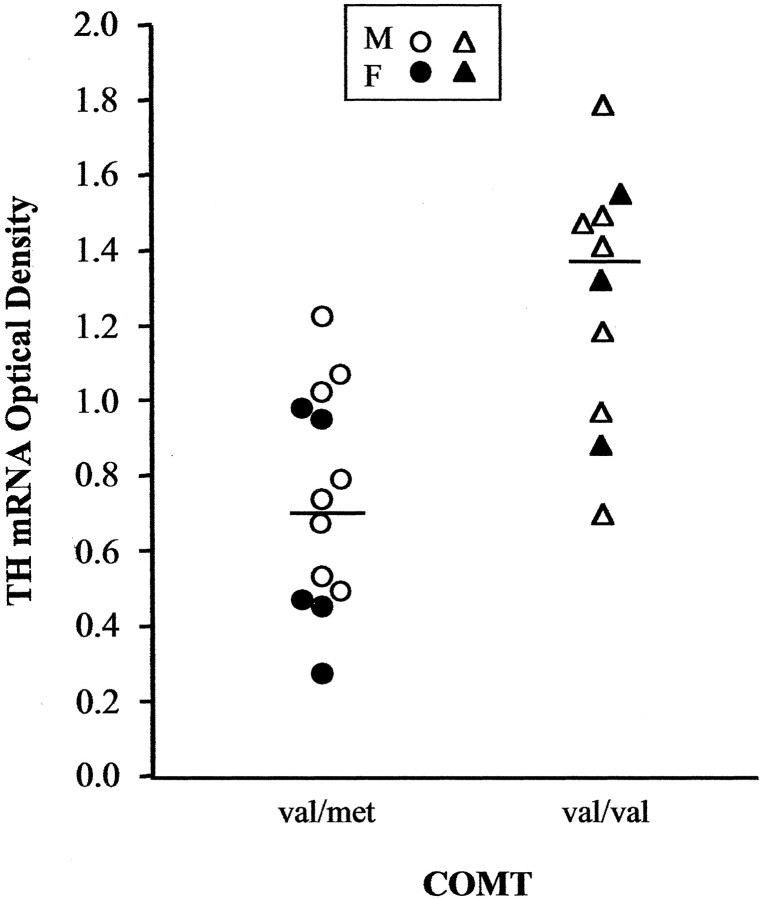

Fig. 3.

Comparisons of mean optical density, reflecting TH mRNA levels, between subjects with val/met (circles) and val/val (triangles) genotypes in the SNV. Each_symbol_ indicates the mean value for one male or female subject (open and filled symbols, respectively), and horizontal lines indicate group means.

In contrast with the TH data, mRNA expression of the DAT, another marker of DA neurons, and cyclophilin, a constitutively expressed protein unrelated to DA metabolism, did not differ between the two COMT genotypes. Differential modification of DAT and of TH mRNA levels in human mesencephalon has also been reported in Parkinson's disease and Alzheimer's disease, which has been interpreted to suggest that TH expression is a more sensitive measure of the DA metabolic activity (Joyce et al., 1997).

Discussion

We found that COMT val158met genotype affects TH gene expression in mesencephalic DA neurons and presumably dopamine biosynthesis in these neurons. COMT is found in low abundance in DA neurons and may only be expressed in specific subpopulations (Lundstrom et al., 1995). Kastner et al. (1994) found that DA neurons in the human VTA and the SNL are weakly immunoreactive for COMT protein, whereas DA neurons in other cell groups that project to the striatum show no COMT expression. In contrast, COMT is expressed in striatal and cortical neurons that receive DA projections. These findings are consistent with pharmacological evidence that the degradation of DA by COMT at most DA synapses takes place at the postsynaptic neuron (Karoum et al., 1993). This means that the effect of COMT genotype on TH gene expression in the mesencephalon is not likely to be a local effect but more likely to be a manifestation of feedback from nondopaminergic to DA neurons.

Several lines of evidence suggest that the effects of COMT genotype on mesencephalic DA function are downstream manifestations of direct effects of COMT on prefrontal cortical neurons. First, in COMT knock-out mice, DA levels in the striatum are not altered, but DA levels in the PFC are increased under certain conditions, and heterozygote knock-outs are intermediate between homozygote knock-outs and wild-type animals (Gogos et al., 1998; Huotari et al., 2002). Importantly, changes in norepinephrine levels are not found in these animals (Gogos et al., 1998; Huotari et al., 2002). This indicates that COMT activity has a relatively selective impact on prefrontal cortical DA signaling and supports speculation that inheritance of the COMT val allele would lead to a relative increase in DA levels in this region. The effect of COMT on DA in the PFC is consistent with low abundance of prefrontal DA transporter (Lewis et al., 2001) and the small effect of DAT function on prefrontal cortical DA levels (Mazei et al., 2002;Moron et al., 2002). Second, 6-hydroxy-DA lesions of the PFC, which destroy DA terminals, have been shown to alter baseline firing of mesencephalic DA neurons and their response to stress (Deutch 1993;Harden et al., 1998), and DA blockade in PFC leads to increased release of DA in striatal terminals (Roberts et al., 1994; Kolachana et al., 1995). Third, abnormal prefrontal function in humans has been linked to upregulated presynaptic striatal dopamine activity. For example, levels of prefrontal cortical _N_-acetyl aspartate, an intracellular neurochemical marker of neuronal integrity assayed _in vivo_with proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, correlate inversely with amphetamine-stimulated striatal DA release in humans (Bertolino et al., 2000). In addition, abnormal prefrontal regional cerebral blood flow during an executive cognition task correlates inversely with f-18fluorodopa uptake in the striatum (Meyer-Lindenberg et al., 2002). Although regions other than the PFC, such as the hippocampus, affect subcortical DA (Floresco et al., 2001), in clinical studies, only PFC _N_-acetyl aspartate levels predicted the responsiveness of subcortical DA to amphetamine challenge (Bertolino et al., 2000), and only prefrontal cortical function is affected by COMT genotype (Egan et al., 2002). These convergent findings implicate PFC projections as mediators of the downstream effect of COMT genotype on TH gene expression in mesencephalic DA neurons.

Whereas TH gene expression has been shown to be dependent on the activity of dopamine neurons (Nagatsu, 1995; Kumer and Vrana, 1996;Tank et al., 1998), DAT expression is not (Hoffman et al., 1998; Heinz et al., 1999). Thus, the differential effect of COMT genotype on gene expression of TH and the DAT in the mesencephalon may reflect alterations in the activity of DA neurons, although this cannot be established in postmortem tissue.

We observed the greatest genotype effects on TH mRNA levels in the ventral tier of the SN and no apparent effects in the VTA, the PN, or the SNL. Although we cannot rule out the possibility that our study design is not sensitive enough to detect small effects in these structures, this intriguing finding may be explained by the pattern of connectivity between prefrontal cortex and mesencephalic DA neurons. The ventral tier of the SN compacta in the nonhuman primate projects primarily to the striatum and amygdala (Haber and Fudge, 1997), suggesting that the effects of COMT genotype on TH regulation are greatest in cell groups that do not project back to the PFC. In the rodent, DA neurons that project to the cortex receive direct prefrontal cortical inputs, whereas those projecting to the striatum do not (Carr and Sesack, 2000). It has been suggested that indirect inputs from prefrontal cortex to DA cell groups that project to the striatum provide tonic inhibition of these cells via GABA intermediates, possibly in striatum and elsewhere in the brainstem (Carlsson, 2001). Thus, relatively decreased DA levels in PFC (presumably related to greater val allele load, may lead to reduced signal-to-noise ratio in assemblies of prefrontal pyramidal neurons (Henze et al., 2000; Seamans et al., 2001). These neurons may then be expected to exert less coherent corticofugal feedback and, thus, less inhibition of DA neurons projecting to the striatum (for a schematic representation, see Fig.4). Our data are consistent with these predicted effects. Of course, the validity of this interpretation depends on the confirmation of the role of GABAergic neurons in this hypothesized circuit. It is also interesting to note that the absence of upregulation in the neuronal populations innervating the cortex would mean that the COMT val effect on DA signaling in the prefrontal cortex is not effectively compensated.

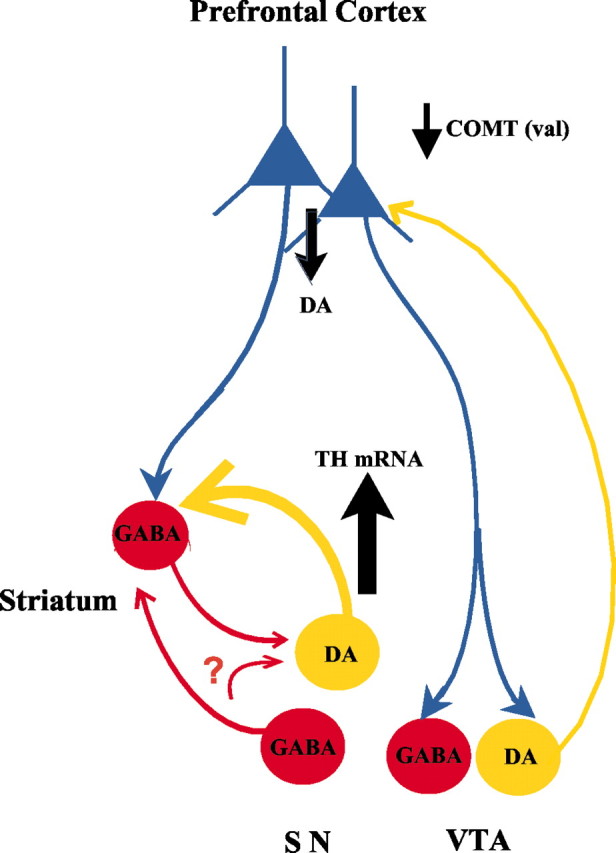

Fig. 4.

Diagram illustrating elements of the circuitry and their putative involvement in the effects of COMT genotype on DA levels in prefrontal cortex and TH gene expression in the brainstem. Relative to val/met, the val/val genotype of the COMT enzyme leads to reduced DA levels in the PFC. It is speculated that indirect PFC projections via GABA neurons in the striatum or mesencephalon lead to increased gene expression of TH mRNA in DA cell groups projecting subcortically. The_question mark_ is to indicate that some of the GABA projections remain to be confirmed. Sources of anatomical information include the following: Lewis (1992), Deutch (1993),Murase et al. (1993), Williams and Goldman-Rakic (1995), Haber and Fudge (1997), Carr and Sesack (2000),Chiba et al. (2001), and Seamans et al. (2001).

Our finding that COMT genotype is a heritable factor in DA modulation may further clarify the mechanism by which the COMT val allele may increase risk for schizophrenia and possibly other psychotic states. Several lines of evidence suggest that a cortical hypo-dopaminergic state is accompanied by a subcortical hyper-dopaminergic state in schizophrenia, thereby contributing to cognitive and psychotic symptoms, respectively (Weinberger, 1987;Weinberger et al., 1988; Grace, 2000). Such reciprocal relationships between cortical and subcortical DA systems have been demonstrated repeatedly in animal experiments (Pycock et al., 1980; Finlay and Zigmond, 1997; Lipska and Weinberger, 1998). Increased responsivity of striatal dopaminergic terminals to amphetamine in schizophrenic patients has also been found (Abi-Dargham et al., 1998; Laruelle, 2000), as has other evidence of presynaptic upregulation of DA metabolism (Hietala et al., 1999; Abi-Dargham et al., 2000;Meyer-Lindenberg et al., 2002). To the extent that schizophrenia involves both abnormalities in prefrontal dopamine signaling and in nigrostriatal dopamine activity, the COMT val allele appears to contribute risk to each of these elements of the disorder and in the specific directions associated with the illness. The reciprocal effects of COMT genotype on DA signaling in the prefrontal cortex and on TH gene expression in the SN implicates a mechanism by which inheritance of COMT val increases risk for schizophrenia and possibly other psychotic disorders.

Finally, it should be emphasized that the effects we observed are in normal human brain. As such, these effects by themselves are compatible with the range of normal brain function. They appear to represent genetically determined variations in prefrontal function and DA neuronal regulation, which, for the val allele, slightly bias humans toward the expression of two biological phenomena associated with schizophrenia: abnormal prefrontal function and upregulated striatal DA activity. It is presumably the interaction of these COMT val effects with other biological processes (both genetic and environmental) from which the clinical disorder emerges.

Footnotes

We thank Dr. Mary Herman for her neuropathology expertise and her efforts in procuring brain specimen. We also thank Juraj Cervenak, Yeva Snitkovsky, Shannon O'Connor, and Christopher Keczkemethy for technical assistance.

Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. Mayada Akil, 10 Center Drive, 4N306, MSC1385, Bethesda, MD 20892. E-mail: akilm@intra.nimh.nih.gov.

References

- 1.Abi-Dargham A, Gil R, Krystal J, Baldwin RM, Seibyl JP, Bowers M, van Dyck CH, Charney DS, Innis RB, Laruelle M. Increased striatal dopamine transmission in schizophrenia: confirmation in a second cohort. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:761–767. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.6.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abi-Dargham A, Rodenhiser J, Printz D, Zea-Ponce Y, Gil R, Kegeles LS, Weiss R, Cooper TB, Mann JJ, Van Heertum RL, Gorman JM, Laruelle M. From the cover: increased baseline occupancy of D2 receptors by dopamine in schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:8104–8109. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.14.8104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abi-Dargham A, Mawlawi O, Lombardo I, Gil R, Martinez D, Huang Y, Hwang DR, Keilp J, Kochan L, Van Heertum R, Gorman JM, Laruelle M. Prefrontal dopamine D1 receptors and working memory in schizophrenia. J Neurosci. 2002;22:3708–3719. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-09-03708.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akil M, Pierri J, Whitehead R, Edgar C, Mohila C, Sampson A, Lewis D. Lamina-specific alterations in the dopamine innervation of the prefrontal cortex in schizophrenic subjects. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1580–1589. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.10.1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barch DM, Carter CS, Braver TS, Sabb FW, MacDonald A, III, Noll DC, Cohen JD. Selective deficits in prefrontal cortex function in medication-naive patients with schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:280–288. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.3.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bertolino A, Breier A, Callicott JH, Adler C, Mattay VS, Shapiro M, Frank JA, Pickar D, Weinberger DR. The relationship between dorsolateral prefrontal neuronal N-acetylaspartate and evoked release of striatal dopamine in schizophrenia. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2000;22:125–132. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(99)00096-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bilder RM, Volavka J, Czobor P, Malhotra AK, Kennedy JL, Ni X, Goldman RS, Hoptman MJ, Sheitman B, Lindenmayer JP, Citrome L, McEvoy JP, Kunz M, Chakos M, Cooper TB, Lieberman JA. Neurocognitive correlates of the COMT Val158Met polymorphism in chronic schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;52:701–707. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01416-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boulton AA, Eisenhofer G. Catecholamine metabolism. From molecular understanding to clinical diagnosis and treatment. Overview. Adv Pharmacol. 1998;42:273–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Callicott JH, Bertolino A, Mattay VS, Langheim FJ, Duyn J, Coppola R, Goldberg TE, Weinberger DR. Physiological dysfunction of the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia revisited. Cereb Cortex. 2000;10:1078–1092. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.11.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carlsson A. Neurocircuitries and neurotransmitter interactions in schizophrenia. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1995;10 [Suppl 3]:21–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carlsson A. A paradigm shift in brain research. Science. 2001;294:1021–1024. doi: 10.1126/science.1066969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carr DB, Sesack SR. Projections from the rat prefrontal cortex to the ventral tegmental area: target specificity in the synaptic associations with mesoaccumbens and mesocortical neurons. J Neurosci. 2000;20:3864–3873. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-10-03864.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carter CS, Perlstein W, Ganguli R, Brar J, Mintun M, Cohen JD. Functional hypofrontality and working memory dysfunction in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:1285–1287. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.9.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chiba T, Kayahara T, Nakano K. Efferent projections of infralimbic and prelimbic areas of the medial prefrontal cortex in the Japanese monkey, Macacca fuscata. Brain Res. 2001;888:83–101. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)03013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daniel DG, Weinberger DR, Jones DW, Zigun JR, Coppola R, Handel S, Bigelow LB, Goldberg TE, Berman KF, Kleinman JE. The effect of amphetamine on regional cerebral blood flow during cognitive activation in schizophrenia. J Neurosci. 1991;11:1907–1917. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-07-01907.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deutch AY. Prefrontal cortical dopamine systems and the elaboration of functional corticostriatal circuits: implications for schizophrenia and Parkinson's disease. J Neural Transm Gen Sect. 1993;91:197–221. doi: 10.1007/BF01245232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Egan MF, Goldberg TE, Kolachana BS, Callicott JH, Mazzanti CM, Straub RE, Goldman D, Weinberger DR. Effect of COMT Val108/158 Met genotype on frontal lobe function and risk for schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:6917–6922. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111134598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Egan M, Goldman D, Weinberger D. The human genome: mutations. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:12. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Finlay JM, Zigmond MJ. The effects of stress on central dopaminergic neurons: possible clinical implications. Neurochem Res. 1997;22:1387–1394. doi: 10.1023/a:1022075324164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Floresco SB, Todd CL, Grace AA. Glutamatergic afferents from the hippocampus to the nucleus accumbens regulate activity of ventral tegmental area dopamine neurons. J Neurosci. 2001;21:4915–4922. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-13-04915.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gogos JA, Morgan M, Luine V, Santha M, Ogawa S, Pfaff D, Karayiorgou M. Catechol-O-methyltransferase-deficient mice exhibit sexually dimorphic changes in catecholamine levels and behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9991–9996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.17.9991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grace A. Gating of information flow within the limbic system and the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. Brain Res Rev. 2000;31:330–341. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(99)00049-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haber SN, Fudge JL. The primate substantia nigra and VTA: integrative circuitry and function. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 1997;11:323–342. doi: 10.1615/critrevneurobiol.v11.i4.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harden DG, King D, Finlay JM, Grace AA. Depletion of dopamine in the prefrontal cortex decreases the basal electrophysiological activity of mesolimbic dopamine neurons. Brain Res. 1998;794:96–102. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00219-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heinz A, Saunders RC, Kolachana BS, Jones DW, Gorey JG, Bachevalier J, Weinberger DR. Striatal dopamine receptors and transporters in monkeys with neonatal temporal limbic damage. Synapse. 1999;32:71–79. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199905)32:2<71::AID-SYN1>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henze DA, Gonzalez-Burgos GR, Urban NN, Lewis DA, Barrionuevo G. Dopamine increases excitability of pyramidal neurons in primate prefrontal cortex. J Neurophysiol. 2000;84:2799–2809. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.84.6.2799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hietala J, Syvalahti E, Vilkman H, Vuorio K, Rakkolainen V, Bergman J, Haaparanta M, Solin O, Kuoppamaki M, Eronen E, Ruotsalainen U, Salokangas RK. Depressive symptoms and presynaptic dopamine function in neuroleptic-naive schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 1999;35:41–50. doi: 10.1016/s0920-9964(98)00113-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoffman BJ, Hansson SR, Mezey E, Palkovits M. Localization and dynamic regulation of biogenic amine transporters in the mammalian central nervous system. Front Neuroendocrinol. 1998;19:187–231. doi: 10.1006/frne.1998.0168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huotari M, Gogos JA, Karayiorgou M, Koponen O, Forsberg M, Raasmaja A, Hyttinen J, Mannisto PT. Brain catecholamine metabolism in catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT)-deficient mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;15:246–256. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Joh TH, Son JH, Tinti C, Conti B, Kim SJ, Cho S. Unique and cell-type-specific tyrosine hydroxylase gene expression. Adv Pharmacol. 1998;42:33–36. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(08)60688-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Joyce JN, Smutzer G, Whitty CJ, Myers A, Bannon MJ. Differential modification of dopamine transporter and tyrosine hydroxylase mRNAs in midbrain of subjects with Parkinson's, Alzheimer's with parkinsonism, and Alzheimer's disease. Mov Disord. 1997;12:885–897. doi: 10.1002/mds.870120609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karoum F, Chrapusta SJ, Egan MF, Wyatt RJ. Absence of 6-hydroxydopamine in the rat brain after treatment with stimulants and other dopaminergic agents: a mass fragmentographic study. J Neurochem. 1993;61:1369–1375. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1993.tb13630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kastner A, Anglade P, Bounaix C, Damier P, Javoy-Agid F, Bromet N, Agid Y, Hirsch EC. Immunohistochemical study of catechol-O-methyltransferase in the human mesostriatal system. Neuroscience. 1994;62:449–457. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90379-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kinon BJ, Lieberman JA. Mechanisms of action of atypical antipsychotic drugs: a critical analysis. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1996;124:2–34. doi: 10.1007/BF02245602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kneavel M, Gogos J, Karayiorgou K, Luine V. Interaction of COMT gene deletion and environment on cognition. Soc Neurosci Abstr. 2000;26:571.20. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kolachana BS, Saunders RC, Weinberger DR. Augmentation of prefrontal cortical monoaminergic activity inhibits dopamine release in the caudate nucleus: an in vivo neurochemical assessment in the rhesus monkey. Neuroscience. 1995;69:859–868. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00246-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kumer SC, Vrana KE. Intricate regulation of tyrosine hydroxylase activity and gene expression. J Neurochem. 1996;67:443–462. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.67020443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kunugi H, Vallada HP, Sham PC, Hoda F, Arranz MJ, Li T, Nanko S, Murray RM, McGuffin P, Owen M, Gill M, Collier DA. Catechol-O-methyltransferase polymorphisms and schizophrenia: a transmission disequilibrium study in multiply affected families. Psychiatr Genet. 1997;7:97–101. doi: 10.1097/00041444-199723000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laruelle M. The role of endogenous sensitization in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia: implications from recent brain imaging studies. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2000;31:371–384. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(99)00054-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lewis DA. The catecholaminergic innervation of primate prefrontal cortex. J Neural Transm Suppl. 1992;36:179–200. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-9211-5_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lewis DA, Melchitzky DS, Sesack SR, Whitehead RE, Auh S, Sampson A. Dopamine transporter immunoreactivity in monkey cerebral cortex: regional, laminar, and ultrastructural localization. J Comp Neurol. 2001;432:119–136. doi: 10.1002/cne.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li T, Sham PC, Vallada H, Xie T, Tang X, Murray RM, Liu X, Collier DA. Preferential transmission of the high activity allele of COMT in schizophrenia. Psychiatr Genet. 1996;6:131–133. doi: 10.1097/00041444-199623000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li T, Ball D, Zhao J, Murray RM, Liu X, Sham PC, Collier DA. Family-based linkage disequilibrium mapping using SNP marker haplotypes: application to a potential locus for schizophrenia at chromosome 22q11. Mol Psychiatry. 2000;5:77–84. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4000638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lipska BK, Weinberger DR. Prefrontal cortical and hippocampal modulation of dopamine-mediated effects. Adv Pharmacol. 1998;42:806–809. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(08)60869-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Little K, McLaughlin D, Zhang L, McFinton P, Dalack G, Cook E, Cassin B, Watson S. Brain dopamine transporter messenger RNA and binding sites in cocaine users. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:793–799. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.9.793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lu XY, Churchill L, Kalivas PW. Expression of D1 receptor mRNA in projections from the forebrain to the ventral tegmental area. Synapse. 1997;25:205–214. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199702)25:2<205::AID-SYN11>3.0.CO;2-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lundstrom K, Tenhunen J, Tilgmann C, Karhunen T, Panula P, Ulmanen I. Cloning, expression and structure of catechol-O-methyltransferase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1251:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(95)00071-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Malhotra AK, Kestler LJ, Mazzanti C, Bates JA, Goldberg T, Goldman D. A functional polymorphism in the COMT gene and performance on a test of prefrontal cognition. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:652–654. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.4.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mannisto PT, Kaakkola S. Catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT): biochemistry, molecular biology, pharmacology, and clinical efficacy of the new selective COMT inhibitors. Pharmacol Rev. 1999;51:593–628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mazei MS, Pluto CP, Kirkbride B, Pehek EA. Effects of catecholamine uptake blockers in the caudate-putamen and subregions of the medial prefrontal cortex of the rat. Brain Res. 2002;936:58–67. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02542-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McRitchie D, Halliday G. Calbindin D28k-containing neurons are restricted to the medial substantia nigra in humans. Neuroscience. 1995;65:87–91. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00483-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meyer-Lindenberg A, Miletich RS, Kohn PD, Esposito G, Carson RE, Quarantelli M, Weinberger DR, Berman KF. Reduced prefrontal activity predicts exaggerated striatal dopaminergic function in schizophrenia. Nat Neurosci. 2002;5:267–271. doi: 10.1038/nn804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moron JA, Brockington A, Wise RA, Rocha BA, Hope BT. Dopamine uptake through the norepinephrine transporter in brain regions with low levels of the dopamine transporter: evidence from knock-out mouse lines. J Neurosci. 2002;22:389–395. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-02-00389.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Murase S, Grenhoff J, Chouvet G, Gonon FG, Svensson TH. Prefrontal cortex regulates burst firing and transmitter release in rat mesolimbic dopamine neurons studied in vivo. Neurosci Lett. 1993;157:53–56. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(93)90641-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nagatsu T. Tyrosine hydroxylase: human isoforms, structure and regulation in physiology and pathology. Essays Biochem. 1995;30:15–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Okubo Y, Suhara T, Suzuki K, Kobayashi K, Inoue O, Terasaki O, Someya Y, Sassa T, Sudo Y, Matsushima E, Iyo M, Tateno Y, Toru M. Decreased prefrontal dopamine D1 receptors in schizophrenia revealed by PET. Nature. 1997;385:634–636. doi: 10.1038/385634a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Palmatier MA, Kang AM, Kidd KK. Global variation in the frequencies of functionally different catechol-O-methyltransferase alleles. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;46:557–567. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Park S, Holzman PS. Schizophrenics show spatial working memory deficits. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:975–982. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1992.01820120063009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Paxinos G. Atlas of the human brainstem. Academic; San Diego: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pycock C, Kerwin R, Carter C. Effect of lesion of cortical dopamine terminals on subcortical dopamine receptors in rats. Nature. 1980;286:74–76. doi: 10.1038/286074a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Roberts AC, De Salvia MA, Wilkinson LS, Collins P, Muir JL, Everitt BJ, Robbins TW. 6-Hydroxydopamine lesions of the prefrontal cortex in monkeys enhance performance on an analog of the Wisconsin Card Sort Test: possible interactions with subcortical dopamine. J Neurosci. 1994;14:2531–2544. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-05-02531.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rosa A, Zarzuela A, Cuesta M, Peralta V, Martinez-Larrea A, Serrano F, Fananas L. New evidence for association between COMT gene and prefrontal neurocognitive functions in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res [Suppl] 2002;53:69. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.6.1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sawaguchi T, Goldman-Rakic PS. The role of D1-dopamine receptor in working memory: local injections of dopamine antagonists into the prefrontal cortex of rhesus monkeys performing an occulomotor delayed-response task. J Neurophysiol. 1994;71:515–528. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.71.2.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Seamans JK, Gorelova N, Durstewitz D, Yang CR. Bidirectional dopamine modulation of GABAergic inhibition in prefrontal cortical pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci. 2001;21:3628–3638. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-10-03628.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tank AW, Piech KM, Osterhout CA, Sun B, Sterling C. Regulation of tyrosine hydroxylase gene expression by transsynaptic mechanisms and cell-cell contact. Adv Pharmacol. 1998;42:25–29. doi: 10.1016/s1054-3589(08)60686-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Uhl GR, Walther D, Mash D, Faucheux B, Javoy-Agid F. Dopamine transporter messenger RNA in Parkinson's disease and control substantia nigra neurons. Ann Neurol. 1994;35:494–498. doi: 10.1002/ana.410350421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Weinberger DR. Implications of normal brain development for the pathogenesis of schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44:660–669. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800190080012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Weinberger DR, Berman KF, Zec RF. Physiologic dysfunction of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia. I. Regional cerebral blood flow evidence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986;43:114–124. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800020020004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Weinberger DR, Berman KF, Illowsky BP. Physiological dysfunction of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia. III. A new cohort and evidence for a monoaminergic mechanism. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45:609–615. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800310013001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Whitfield HJ, Jr, Brady LS, Smith MA, Mamalaki E, Fox RJ, Herkenham M. Optimization of cRNA probe in situ hybridization methodology for localization of glucocorticoid receptor mRNA in rat brain: a detailed protocol. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 1990;10:145–157. doi: 10.1007/BF00733641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Williams GV, Goldman-Rakic PS. Modulation of memory fields by dopamine D1 receptors in prefrontal cortex. Nature. 1995;376:572–575. doi: 10.1038/376572a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]