Transcription Factor Hepatocyte Nuclear Factor 6 Regulates Pancreatic Endocrine Cell Differentiation and Controls Expression of the Proendocrine Gene ngn3 (original) (raw)

Abstract

Hepatocyte nuclear factor 6 (HNF-6) is the prototype of a new class of cut homeodomain transcription factors. During mouse development, HNF-6 is expressed in the epithelial cells that are precursors of the exocrine and endocrine pancreatic cells. We have investigated the role of HNF-6 in pancreas differentiation by inactivating its gene in the mouse. In _hnf6_−/− embryos, the exocrine pancreas appeared to be normal but endocrine cell differentiation was impaired. The expression of neurogenin 3 (Ngn-3), a transcription factor that is essential for determination of endocrine cell precursors, was almost abolished. Consistent with this, we demonstrated that HNF-6 binds to and stimulates the ngn3 gene promoter. At birth, only a few endocrine cells were found and the islets of Langerhans were missing. Later, the number of endocrine cells increased and islets appeared. However, the architecture of the islets was perturbed, and their β cells were deficient in glucose transporter 2 expression. Adult _hnf6_−/− mice were diabetic. Taken together, our data demonstrate that HNF-6 controls pancreatic endocrine differentiation at the precursor stage and identify HNF-6 as the first positive regulator of the proendocrine gene ngn3 in the pancreas. They also suggest that HNF-6 is a candidate gene for diabetes mellitus in humans.

The pancreas contains exocrine cells that produce digestive enzymes, ducts through which these enzymes transit to the gut, and endocrine cells, organized in islets of Langerhans, that produce insulin, glucagon, somatostatin, and pancreatic polypeptide (PP). The pancreas arises from the primitive gut epithelium as a dorsal bud and a ventral bud, which later fuse to form a single organ (reviewed in reference 29). The pancreatic epithelium, surrounded by mesenchyme, then proliferates and branches into multiple evaginations. During the initial stage of pancreas development (embryonic day 9.5 [e9.5] to approximately e14.5 in the mouse), the pancreatic epithelium consists mainly of cells that are the precursors of the acinar, ductal, and endocrine cells (29). Starting at e9.5, early glucagon-expressing cells are found in the epithelium. Around e12, glucagon cells are found both within the epithelium and in small clusters that are distinct from the epithelium. The fate of these clusters is unknown. Starting around e14.5 to e15, a wave of differentiation is associated with an increase in the synthesis of digestive enzymes and hormones, ultimately resulting in the formation of the acini, ducts, and islets of Langerhans around e18 to e19. The insulin-expressing cells (β cells) are then in the core of the islets, and the cells expressing glucagon (α cells), somatostatin (δ cells), and PP are located at their periphery (reviewed in references 29 and 32).

A number of transcription factors are involved in endocrine pancreas development (reviewed in references 8 and 25). They belong to the class of basic helix-loop-helix factors (Ngn-3, NeuroD/Beta2, and Hes-1) or are homeoproteins of the LIM (Isl-1), paired-box (Pax-4 and Pax-6), Antennapedia (Hb9 and Pdx-1; also known as IPF-1, IDX-1, STF-1, IUF-1, and GSF), or NK-2 (Nkx2.2) class. Targeted disruption of the genes coding for these transcription factors indicated that they are required for pancreatic morphogenesis and/or for the differentiation of one or several pancreatic endocrine cell types (1, 2, 10, 13, 17, 18, 23, 24, 26, 31, 33–36). The temporal and cellular expression profiles of these factors and the results of gene disruption experiments led to the proposal that pancreatic endocrine cell differentiation relies on the activation of a cascade of transcription factors (8, 16). Moreover, it was proposed recently that pancreatic endocrine cell differentiation is controlled by a lateral specification mechanism involving the Notch signaling pathway, in which Ngn-3 is the earliest marker of endocrine cell precursors (3, 10, 17).

We isolated previously a cDNA coding for the transcription factor hepatocyte nuclear factor 6 (HNF-6) (22). HNF-6 belongs to the new ONECUT class of cut homeodomain proteins, whose members contain a single cut domain and a divergent homeodomain (21, 22). In the mouse embryo, hnf6 is expressed in several tissues, including the epithelial cells of the pancreas, starting at the onset of its development (20, 30). During formation of the acini, ducts, and islets, the expression of hnf6 becomes restricted to the acini and ductal cells (20, 30). Transient transfection experiments have identified target genes for HNF-6. These include _hnf3_β, which is coexpressed with hnf6 in the developing pancreatic epithelium (20, 30). Since the expression of Pdx-1, a factor whose absence leads to pancreatic agenesis (18), is controlled by HNF-3β (36) and since HNF-3β expression is stimulated by HNF-6, it has been proposed that HNF-6 is a key component of the pancreatic transcription factor cascade (11). To investigate the role of HNF-6 in pancreatic cell differentiation, we inactivated its gene by homologous recombination in the mouse.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of targeting vector and generation of knockout mice.

The targeting construct was made by subcloning hnf6 gene fragments from a strain 129 mouse genomic library in the pPNT vector. R1 embryonic stem (ES) cells (a gift from A. Nagy) derived from blastocysts of mouse strain 129 were electroporated with the linearized construct and were selected with G418 and ganciclovir. Independent ES clones containing an inactivated hnf6 allele were aggregated with Swiss strain morula-stage embryos as described previously (6), and the embryos were transferred into pseudopregnant Swiss foster mothers. Two chimeric males from independent clones were test bred with Swiss mice for germ line transmission. Heterozygous offspring was intercrossed to generate _hnf6_−/− progeny. The progeny derived from each of these two males displayed the same phenotype. The phenotype of the hnf6+/− mice was normal. These mice were therefore used as controls together with wild-type littermates.

Immunohistochemistry.

Dissected pancreas, fixed in Bouin's solution or in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline, was embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 5 μm, and immunostained. Primary antibodies were mouse antiinsulin (Novo BioLabs clone HUI-018), mouse antiglucagon (Novo BioLabs clone GLU-001), rabbit anti-islet amyloid polypeptide, rabbit anti-glucose transporter 2 (Glut-2) (Chemicon AB1342 or gift from B. Thorens), rabbit anti-Pdx-1, mouse antisomatostatin (Novo BioLabs clone SOM-018), rabbit anti-PP (Lilly), rabbit anti-Pax-6, mouse anti-Isl-1, and rabbit anti-Nkx6.1. Primary antibodies were detected by immunoperoxidase using biotinylated sheep anti-rabbit or anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (Boehringer Mannheim/Roche), a streptavidin-peroxidase conjugate (Boehringer Mannheim/Roche), and DAB+ (Dako). For immunofluorescence, primary antibodies were detected with secondary antibodies coupled to Texas red or Cy-2 (Jackson Immunochemicals).

In situ hybridization.

Nonradioactive in situ cohybridization with RNA antisense probes labeled with digoxigenin-UTP or fluorescein-UTP was performed as described in reference 9. The Ngn-3 probe is 0.75 kb long and encompasses the entire Ngn-3 coding sequence (7). The HNF-6 probe spans nucleotides 1214 to 1607 of the mouse HNF-6 cDNA (nucleotide numbering as in GenBank accession no. U95945).

Multiplex RT-PCR analysis.

Multiplex reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR), which allows coamplification of several cDNAs from total RNA, was performed as described elsewhere (15). Amplification products were quantified using a PhosphorImager, and relative mRNA concentrations were calculated as ratios to the coamplified internal standard. Primer sequences were 5′-TGGCGCCTCATCCCTTGGATG-3′ and 5′-CAGTCACCCACTTCTGCTTCG-3′ (Ngn-3), 5′-CTGGTTCCCTGAGGGTTTCAA-3′ and 5′-GGAACTTCTTGGTCTCCAGGT-3′ (Notch-1), 5′-CAACATGGGCCGCTGTCCTC-3′ and 5′-CACATCTGCTTGGCAGTTGATC-3′ (Notch-2), 5′-GCAGCTGTGAACAACGTGGAG-3′ and 5′-AACCGCACAATGTCCTGGTGC-3′ (Notch-3), 5′-TCAACACGACACCGGACAAACC-3′ and 5′-GGTACTTCCCCAACACGCTCG-3′ (Hes-1), 5′-ACCCTTCACCAATGACTCCTATG-3′ and 5′-ATGATGACTGCAGCAAATCGC-3′ (TATA binding protein [TBP]), and 5′-GACCTGCAGAGCTCCAATCAAC-3′ and 5′-CACGACCCTCAGTACCAAAGGG-3′ (glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase [G6PDH]), 5′-CAGCACCTCACGCCCACCTC-3′ and 5′-CTTCCCATGTTCTTGCTCTTTCC-3′ (HNF-6).

Cloning of the mouse ngn3 gene promoter.

A 7.0-kb-long genomic _Xba_I-_Xho_I fragment was cloned in pBluescript (10), and a 5.1-kb region from 4.95 kb upstream to 0.15 kb downstream of the ATG initiator codon was sequenced using Li-Cor 4000L and Beckman CEQ 2000 automated DNA sequencers.

Transfections.

Rat-1 fibroblasts were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. Cells (3 × 105) grown in serum-free DMEM on 60-mm-diameter dishes were cotransfected by lipofection using DOTAP and 3 μg of a reporter vector containing the ngn3 gene promoter cloned upstream of the firefly luciferase gene, 1.5 μg of the pECE-HNF6α expression vector, and 500 ng of pRL138 plasmid coding for Renilla luciferase as internal control. After 5 h, the medium was replaced by DMEM plus 10% fetal calf serum and further incubated for 40 h before measuring luciferase activities with a Dual-Luciferase kit (Promega). Luciferase activities were measured with a TD-20/20 Luminometer (Promega) and expressed as the ratio of reporter activity (firefly luciferase) to internal control activity (Renilla luciferase). pECE-HNF6α and pRL138 have been described elsewhere (21, 22). The ngn3 promoter reporter vector p3957ngn3-luc contains a 3,957-bp-long _Bstu_I-_Bstu_I genomic fragment (from −4573 to −617 relative to the ATG initiator codon) cloned in the _Sma_I site of pGL3 basic (Promega).

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA).

Recombinant HNF-6 was in vitro transcribed and translated using a wheat germ extract (TNT expression system; Promega). Five microliters of the reaction mix was incubated on ice for 20 min in a final volume of 20 μl containing 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.6), 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EGTA, 50 mM KCl, 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, 3 μg of poly(dI-dC), and the 32P-labeled probe (30,000 cpm). The samples were loaded on a 6% acrylamide gel (acrylamide/bisacrylamide ratio of 29:1) in 0.25× Tris-borate-EDTA buffer and electrophoresed at 200 V. The sense-strand sequences of the double-stranded oligonucleotide probes, derived from the mouse ngn3 gene, were 5′-CTTCCCGATAGCATCCATAGTGGGGCGGGG-3′ (proximal site) and 5′-GCTCAGTGCCAAATCCATGTGTCAGCTTCT-3′ (distal site) (the HNF-6 binding consensus is underlined).

Glucose, insulin, and glucagon measurements.

Blood glucose (tail vein) was measured using an Elite glucometer (Bayer). Insulin and glucagon levels were measured by radioimmunoassay on 25 μl of plasma using the sensitive rat insulin radioimmunoassay and glucagon radioimmunoassay pancreas-specific kits (Linco).

RESULTS

Targeted disruption of the hnf6 gene and generation of HNF-6 knockout mice.

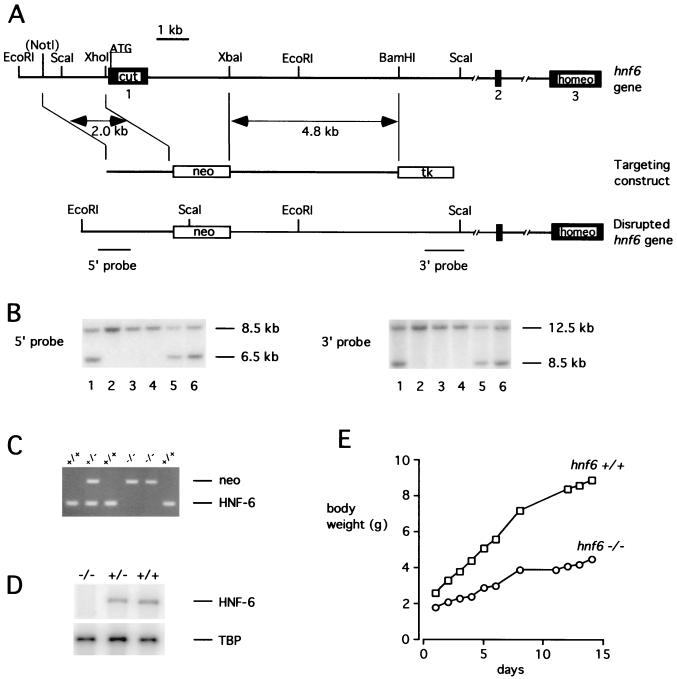

We inactivated the hnf6 gene in the mouse by homologous recombination (Fig. 1). A neomycin resistance gene (neo) cassette was used to replace the proximal promoter region and the first exon. This exon codes for a region of the protein that is essential for DNA binding and transcriptional activity (21). The strategy for disrupting the hnf6 gene is shown in Fig. 1A. The recombinant ES clones were identified by Southern blotting using probes located 5′ and 3′ from the recombination site (Fig. 1B). The resulting transgenic mice were genotyped by PCR as in Fig. 1C. Lack of hnf6 expression in _hnf6_−/− pancreas was confirmed by RT-PCR (Fig. 1D). hnf6+/− mice were phenotypically normal. Cross-breeding of these mice produced _hnf6_−/− offspring at the frequency of 22% (83/376). The _hnf6_−/− mice were growth retarded at birth and showed a reduced growth rate (Fig. 1E). Seventy-five percent of them died between postnatal day 1 (P1) and P10, probably as a result of liver failure. The surviving mice reached adulthood.

FIG. 1.

Targeted disruption of the hnf6 gene and generation of _hnf6_−/− mice. (A) Scheme of the hnf6 gene, targeting construct, and product of homologous recombination. The three exons are shown as black boxes. Cut and homeo refer to the cut domain and homeodomain; neo and tk refer to the neomycin resistance and thymidine kinase genes. The _Not_I site derived from the polylinker of a genomic phage clone. (B) Southern blot analysis of DNA isolated from six ES cell clones resistant to G418 and ganciclovir. Correct homologous recombination at the 5′ end was confirmed by hybridization of _Eco_RI-digested DNA with the 5′ probe. This probe detected an 8.5-kb wild-type and a 6.5-kb recombinant fragment. Correct homologous recombination at the 3′ end was confirmed by hybridization of _Sca_I-digested DNA with the 3′ probe, which detected a 12.5-kb wild-type and an 8.5-kb recombinant fragment. (C) PCR genotyping of tail DNA. Primer pairs amplifying sequences neo (5′-CTGTGCTCGACGTTGTCACTG-3′ and 5′-GATCCCCTCAGAAGAACTCGT-3′) and of exon 1 of the hnf6 gene (5′-CAGCACCTCACGCCCACCTC-3′ and 5′-CAGCCACTTCCACATCCTCCG-3′) were added simultaneously in the PCR. (D) Multiplex RT-PCR analysis of total RNA from e14.5 pancreas with primers located in exons 1 and 3 of the hnf6 gene and with sequences of TBP as internal control. hnf6 mRNA was undetectable in _hnf6_−/− pancreas, and the ratio of HNF-6 to TBP amplification products in hnf6+/− mice was 52% of that in hnf6+/+ mice. (E) Weight gain curve of a representative _hnf6_−/− mouse shows a reduced growth rate compared to a wild-type littermate.

Defective endocrine cell differentiation in HNF-6 knockout mice.

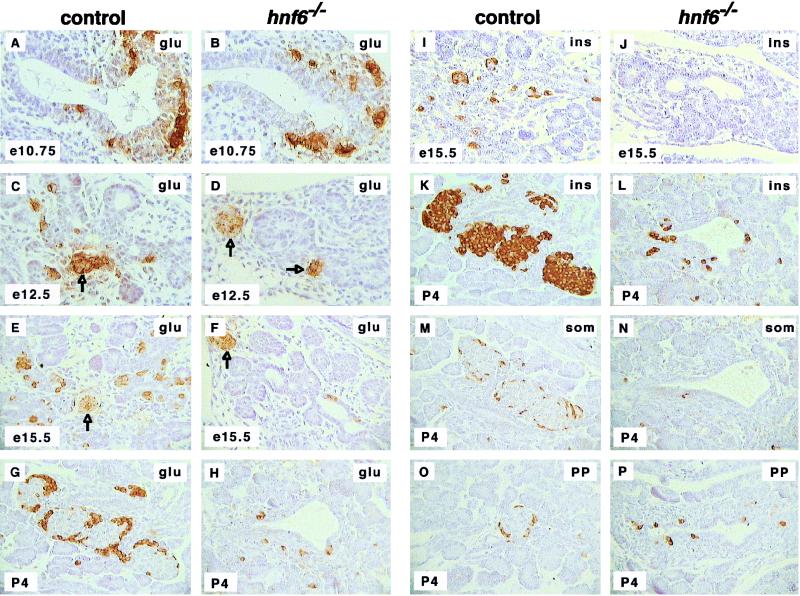

To analyze the pancreas of _hnf6_−/− mice, we first performed histological and immunohistochemical examinations on embryos at various stages of development. Exocrine tissue was histologically normal. In keeping with this, the expression of the exocrine marker p48 (19) was normal at e14.5 (not shown). In contrast, endocrine development was severely inhibited in all embryos. Indeed, the number of glucagon-expressing cells was reduced by 85% in _hnf6_−/− embryos compared to control embryos at e12.5 and e15.5 (Fig. 2C to F). This reduction involved the glucagon-expressing cells found interspersed in the epithelium. However, glucagon expression was normal at e10.75 (Fig. 2A and B), and the number of clusters of early glucagon cells was normal at e12.5 and e15.5 (arrows in Fig. 2C to F). No insulin was found at e15.5 in _hnf6_−/− embryos, in contrast to control animals, in which insulin-expressing cells were found scattered throughout the epithelium (Fig. 2I and J). At P4, _hnf6_−/− animals showed a markedly reduced number of α cells (Fig. 2G and H), β cells (Fig. 2K and L), δ cells (Fig. 2M and N), and PP cells (Fig. 2O and P). These four cell types were scattered within, and in the vicinity of, pancreatic ducts, instead of being clustered in typical islets as in control littermates.

FIG. 2.

Defective endocrine cell differentiation and islet morphogenesis in _hnf6_−/− mice. In _hnf6_−/− mice, the number of glucagon (glu)-expressing cells was normal at e10.75 (A and B) but was reduced at e12.5, e15.5, and P4 (C to H). However, the number of clusters of early glucagon-expressing cells was normal at e12.5 and e15.5 (arrows in panels C to F). In _hnf6_−/− mice, there was a reduced number of insulin (ins)-expressing cells at e15.5 and P4 (I to L), of somatostatin (som)-expressing cells at P4 (M and N), and of PP-expressing cells at P4 (O and P). At P4, hormone-producing cells were found near pancreatic ducts in _hnf6_−/− mice, instead of being organized in islets as in control littermates (G, H, and K to P). Original magnifications: ×400 (A to D, I, and J) and ×312.5 (E to H and K to P).

In _hnf6_−/− mice, the endocrine cells became organized in islets only 2 to 3 weeks after birth. The architecture of the islets was abnormal, as they showed no mantle of α cells around the core of β cells at 5 weeks (Fig. 3A and B) and at 10 weeks many α cells were found throughout the islets, instead of being located at their periphery (not shown). The differentiation state of islet cells in 5-week-old _hnf6_−/− mice was investigated by monitoring the coexpression of hormonal and metabolic markers. Glut-2, which in wild-type mice is expressed in β cells, was undetectable by immunofluorescence in most of the _hnf6_−/− mice. In the _hnf6_−/− mice in which some Glut-2 could be visualized, its expression was markedly reduced (Fig. 3C and D). Unlike in control mice, IAPP (amylin) was absent from several insulin-positive cells (Fig. 3E and F).

FIG. 3.

Formation of abnormal islets of Langerhans in _hnf6_−/− mice. (A and B) At 5 weeks (5W), islets of Langerhans were detected in _hnf6_−/− mice, but their architecture was perturbed and no mantle of glucagon (glu)-expressing cells (green) was seen around the insulin (ins)-expressing cells (red). (C and D) Glut-2 expression was low and could be detected only in some _hnf6_−/− mice (glucagon, red; Glut-2, green). A few glucagon-expressing cells were found in the epithelium lining the cysts (arrows in panel D). (E and F) Insulin (red) and IAPP (green) were coexpressed in control and _hnf6_−/− mice, but insulin-positive, IAPP-negative cells were found in _hnf6_−/− mice. The epithelium of the cysts showed a few cells that express hormones (arrows in panels B, D, and F). (G) Section through a duct in a control animal showed the expected absence of pdx1 expression. (H) The epithelium of a cyst showed pdx1 expression in _hnf6_−/− mice. (I and J) Similarly to what is observed during regeneration after pancreatectomy, insulin- or glucagon-expressing cells were detected near ducts in _hnf6_−/− mice. Panels A to F and G to H are from 5- and 10-week-old animals, respectively. Original magnifications: ×200 (A to F), ×640 (G and H), and ×500 (I and J).

We conclude that in _hnf6_−/− mice, (i) endocrine pancreas development is severely inhibited; (ii) the appearance of the islets of Langerhans is delayed; (iii) when the islets form, they display a perturbed architecture and contain cells that have not reached full maturity.

Analysis of differentiation markers in _hnf6_−/− mice.

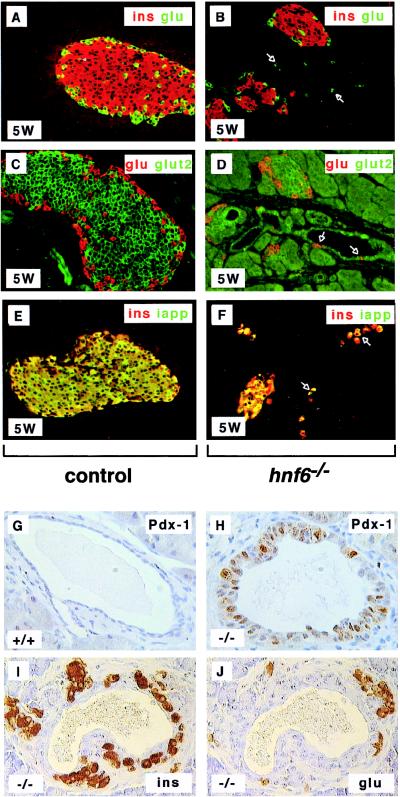

To explore how endocrine pancreas development is perturbed in _hnf6_−/− embryos, we analyzed by immunohistochemistry the expression of pancreatic transcription factors at various stages of development. Pdx-1 and Nkx6.1 are markers of the early pancreatic epithelium. Their expression indicates that endodermal cells have been specified to a pancreatic fate (27). Isl-1 and Pax-6 are expressed in postmitotic cells that have started to differentiate into either one of the four endocrine cell types (1, 8, 31, 34).

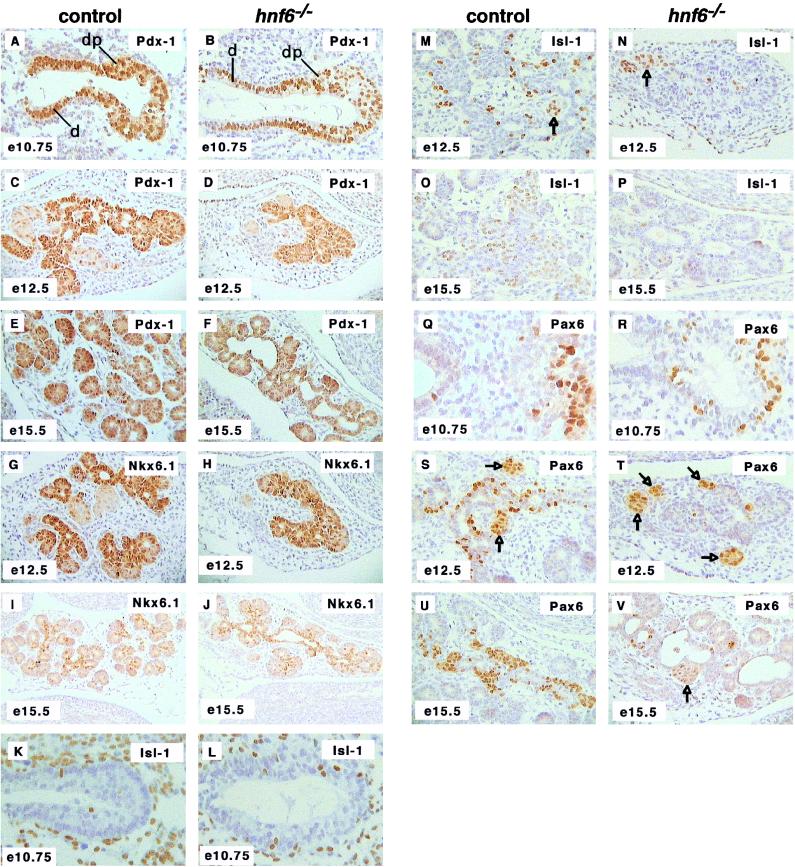

The expression of pdx1 and of nkx6.1 was normal at e10.75, e12.5, and e15.5 (Fig. 4A to J). Cells expressing isl1 and pax6 were found in normal numbers at e10.75 (Fig. 4K, L, Q, and R) but in much lower numbers at e12.5 and e15.5 in _hnf6_−/− embryos than in control embryos (Fig. 4M to P and S to V). In line with the normal expression of glucagon in the early glucagon cell clusters (Fig. 2D and F), the expression of isl1 and pax6 was detected at normal levels in these cell clusters (arrows in Fig. 4M, N, S, T, and V).

FIG. 4.

Expression of differentiation markers in the pancreas of _hnf6_−/− embryos. Expression of the early pancreatic epithelium markers Pdx-1 (A to F) and Nkx6.1 (G to J) was normal at e10.75, e12.5, and e15.5. Cells expressing the endocrine markers isl1 and pax6 were found in normal numbers at e10.75 (K, L, Q, and R) but in markedly reduced numbers at e12.5 and e15.5 (M to P and S to V). The expression of isl1 and of pax6 was normal in the clusters of early glucagon-expressing cells (arrows in panels M, N, S, T, and V). At e15.5, the pancreatic epithelium of _hnf6_−/− embryos displayed cystic structures delineated by _pdx1_- and _nkx6.1_-expressing cells (F and J). d, duodenum; dp, dorsal pancreas. Original magnifications: ×312.5 (B, C, D, G, H, U, and V), ×200 (I and J), ×640 (K, L, Q, and R), ×400 (A, E, F, M to P, S, and T).

Starting around e15, the pancreas of _hnf6_−/− embryos showed cystic structures. These were delineated by cells that had characteristics of the early pancreatic epithelium, as they all expressed pdx1 and nkx6.1 (Fig. 4F and J). Within the epithelium lining the cysts, a few cells expressed the endocrine markers isl1 and pax6 (Fig. 4P and V). After birth, the cysts developed as enlarged ducts or as large cavities (up to 2 cm). Their epithelium expressed pdx1 (Fig. 3H), contrary to normal ductal cells (Fig. 3G). Insulin- or glucagon-expressing cells were then detected within, or in close association with, the epithelium lining the cysts (Fig. 3B, D, and F) or the pancreatic ducts (Fig. 3I and J). Insulin-negative, Glut-2-positive cells were also seen in the epithelium lining the cysts at 5 weeks (data not shown), which is interesting since glut2 is expressed not only in mature β cells but also in the undifferentiated pancreatic epithelium (28).

We conclude from these experiments that in the absence of HNF-6, the pancreatic epithelium is specified. However, this epithelium fails to give rise, between e10.75 and e12.5, to the expected pool of _isl1_- and _pax6_-expressing cells. Instead, this epithelium generates cystic structures delineated by _pdx1_- and _nkx6.1_-expressing cells.

Reduced expression of the proendocrine gene ngn3 in _hnf6_−/− embryos.

A lateral specification mechanism is involved in pancreatic endocrine cell differentiation (3). In this mechanism, the proendocrine gene ngn3, which is the earliest marker of endocrine cell precursors, plays a dual role. First, Ngn-3 is essential for endocrine differentiation (3, 10). Second, it is proposed that Ngn-3 stimulates the synthesis of Notch ligands, which activate the Notch pathway in neighboring Notch-expressing cells. This increases the expression of hes1, which decreases that of ngn3 and consequently inhibits endocrine differentiation.

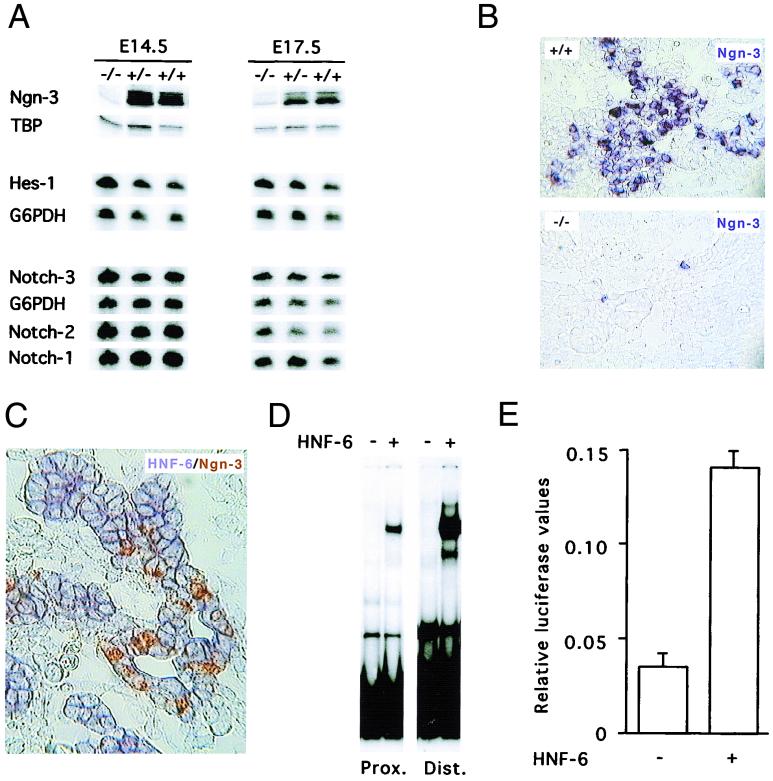

To determine how HNF-6 controls endocrine differentiation, we measured the expression of genes involved in the pancreatic Notch signaling pathway. We microdissected out the pancreas of e14.5 and e17.5 embryos and measured mRNA contents by RT-PCR (Fig. 5A). Our results showed that notch-1, -2, and -3 as well as hes1 were expressed at similar levels in control and _hnf6_−/− embryos. In contrast, the mRNA coded by ngn3 was nearly undetectable in _hnf6_−/− embryos. Consistent with this, in situ hybridization experiments showed that the number of _ngn3_-positive cells was strongly reduced in e14.5 _hnf6_−/− embryos compared to wild-type embryos (Fig. 5B). In the few _ngn3_-positive cells, labeling was weaker than in wild-type embryos. These observations suggested that HNF-6 controls directly or indirectly the expression of the ngn3 gene. We therefore determined by in situ cohybridization if ngn3 and hnf6 are coexpressed in the pancreatic epithelium of normal embryos during development. The results showed that hnf6 is expressed throughout the pancreatic epithelium and that the _ngn3_-positive cells coexpress hnf6 (Fig. 5C and data not shown). To investigate whether HNF-6 can directly control transcription of the ngn3 gene, we searched for HNF-6 binding sites in the ngn3 promoter. As no information on this promoter was available, we cloned a fragment of the mouse ngn3 gene (10) and sequenced 4.95 kb upstream of the coding region. We identified a TATA box consensus and found two nucleotide sequences that match (21) the HNF-6 DNA-binding consensus 5′-(A/T/G)(A/T)(A/G)TC(A/C)ATN(A/T/G)-3′. These are located 453 bp (5′-GCATCCATAG-3′) and 3,187 bp (5′-AAATCCATGT-3′) upstream of the TATA box. In EMSA, each of these sites bound in vitro-synthesized HNF-6 (Fig. 5D). The difference in the intensity of the retarded complexes generated with the two probes indicated that the distal site binds HNF-6 with higher affinity than the proximal one. To test if HNF-6 can stimulate transcription from the ngn3 gene promoter, transient transfection experiments were then performed with a 3,957-bp-long ngn3 gene fragment containing the two HNF-6 sites cloned upstream of the luciferase gene. The results showed that this ngn3 gene fragment displays promoter activity and that cotransfection of an HNF-6 expression vector stimulates this activity fourfold (Fig. 5E).

FIG. 5.

HNF-6 controls expression of the ngn3 gene. (A) Multiplex semiquantitative RT-PCR experiments were performed on total RNA extracted from microdissected pancreas from hnf6+/+, hnf6+/−, and _hnf6_−/− embryos at e14.5 and e17.5. The expression of ngn3 was downregulated in _hnf6_−/− embryos, and that of notch-1, -2, and -3 and of hes1 was unaffected, compared to wild-type and heterozygous embryos. G6PDH mRNA or TBP mRNA was coamplified as internal control. (B) In situ hybridization on sections of e14.5 embryos showed that a digoxigenin-labeled ngn3 probe detected fewer _ngn3_-positive cells in the pancreas of _hnf6_−/− embryos than in wild-type embryos. (C) In situ cohybridization with fluorescein-labeled ngn3 (brown staining) and digoxigenin-labeled hnf6 (blue staining) probes on a section of a e14.5 wild-type pancreas showed that _ngn3_-positive cells coexpress hnf6. (D) EMSA show that in vitro-translated HNF-6 binds to two sites of the ngn3 gene promoter. A retarded band was observed when either the proximal (Prox.) or the distal (Dist.) site was used as a probe in the presence of HNF-6-programmed wheat germ extracts but not with unprogrammed extracts. (E) HNF-6 stimulates the ngn3 gene promoter. Rat-1 cells were transiently cotransfected with a firefly luciferase reporter plasmid containing 3,957 bp of ngn3 promoter sequence and an internal control plasmid coding for Renilla luciferase, in the presence or absence of HNF-6 expression vector, as indicated (mean ± standard error of the mean, n = 4).

We conclude from this set of experiments that hnf6 and ngn3 are coexpressed in the pancreatic epithelium, that HNF-6 can stimulate ngn3 gene expression, and that inactivation of the hnf6 gene drastically reduces expression of the ngn3 gene in the endocrine cell precursors.

Perturbed glucose homeostasis in _hnf6_−/− mice.

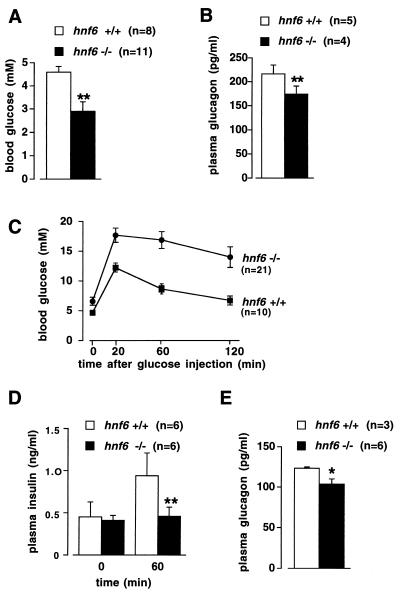

The reduction in the number of endocrine cells and the absence of islets of Langerhans at birth prompted us to determine how glycemia is controlled in the postnatal period. Blood glucose, glucagon, and insulin levels were measured in 4-day-old mice. The mice were starved for 4 h to standardize for the feeding status. Figure 6A shows that blood glucose levels were significantly lower in _hnf6_−/− mice than in their wild-type littermates. In _hnf6_−/− mice the insulin levels were below the threshold sensitivity of the assay (<0.05 ng/ml; n = 4), in contrast to the wild-type mice, for which a value of 0.46 ± 0.04 ng/ml (n = 3) was found. Glucagon levels were reduced by approximately 20% in the _hnf6_−/− mice compared to wild-type mice (Fig. 6B). We interpreted the data as follows. Low insulinemia in _hnf6_−/− mice is consistent with the fasting state of the animals and with the low number of β cells in the pancreas (Fig. 2K and L). Low glucagonemia is consistent with the low number of pancreatic α cells (Fig. 2G and H). The apparent discrepancy in _hnf6_−/− mice between a strong reduction in pancreatic α cell number and a mildly reduced blood glucagon level can be explained by the fasting state, which stimulates glucagon secretion. In these mice, however, glucagon secretion is not sufficient to ensure normal glucagonemia and normoglycemia. We conclude that glucose homeostasis is perturbed in newborn _hnf6_−/− mice, at least in part as a consequence of inappropriate insulinemia and glucagonemia.

FIG. 6.

Perturbed glucose homeostasis in _hnf6_−/− mice. (A and B) Four-day-old mice were starved for 4 h, and blood glucose and plasma glucagon levels were measured. The _hnf6_−/− mice showed hypoglycemia and slightly reduced glucagonemia compared to wild-type mice. (C and D) Ten-week-old mice were fasted overnight and injected intraperitoneally with glucose (0.2 g/ml; 2 g/kg of body weight). Blood glucose levels were measured at the times indicated and showed that the _hnf6_−/− mice were glucose intolerant (C). Glucose intolerance in _hnf6_−/− mice was associated with absence of insulin response. Plasma insulin levels were measured before and 60 min after the injection of glucose for the tolerance tests (D). (E) Plasma glucagon levels were measured in 10-week-old mice after overnight fasting. The data showed slightly reduced glucagonemia in _hnf6_−/− mice compared to wild-type animals. ∗, P < 0.05; ∗∗, P < 0.01.

Five- to ten-week-old _hnf6_−/− mice had islets of Langerhans, but the morphology of the islets was abnormal (Fig. 3). To further investigate glucose homeostasis in adult _hnf6_−/− mice, we performed glucose tolerance tests on 10-week-old animals. hnf6+/− mice showed normal fasting glycemia and normal blood glucose response curves (data not shown). In contrast, _hnf6_−/− mice exhibited elevated fasting glycemia and were glucose intolerant (Fig. 6C). The perturbed glucose response curve was, at least in part, a consequence of insufficient glucose-induced insulin response, as shown by the low levels of insulin 1 h after glucose injection (Fig. 6D). In addition, glucagonemia, measured after an overnight fasting period, was slightly lower than in the wild-type mice. We conclude that lack of HNF-6 results in diabetes.

DISCUSSION

In the present work we addressed the question of the role of the ONECUT transcription factor HNF-6 in pancreatic cell differentiation. The early, specified, pancreatic epithelium contains precursors of the exocrine and endocrine cells (29), and it expresses pdx1, nkx6.1, and hnf6. Our results show that HNF-6 is dispensable for reaching this specified state. Indeed, expression of pdx1 and nkx6.1 was normal at the initiation of pancreas development (e10.75) in the _hnf6_−/− embryos. Further differentiation of the pancreatic epithelium into exocrine pancreatic cells was unaffected in _hnf6_−/− embryos. In contrast, the number of the four endocrine cell types was reduced and the islets of Langerhans were absent at birth, indicating that HNF-6 is involved in endocrine cell differentiation.

Ngn-3 was recently characterized as a proendocrine factor, since its expression is required for endocrine determination (3) and its absence in _ngn3_−/− mice results in lack of pancreatic endocrine cells (10). In wild-type embryos, ngn3 expression starts around e9.5, peaks around e13.5 to e15.5, and disappears postnatally. It is proposed (3, 17) that expression of ngn3 induces both endocrine differentiation and the synthesis of Notch ligands. Binding of Notch ligands to receptors of neighboring cells would stimulate in these cells the synthesis of Hes-1, a factor that represses ngn3 expression. In _hnf6_−/− embryos, the concentration of Ngn-3 mRNA was very low at e14.5 to e17.5. This was not a consequence of increased hes1 gene expression, since the levels of Hes-1 mRNA were normal. Instead, our observations suggested that HNF-6 stimulates ngn3 expression and that absence of HNF-6 results in reduced ngn3 gene activation. Indeed, we showed that HNF-6 can bind to and activate the ngn3 promoter. Given the known requirement of Ngn-3 for endocrine differentiation, it is not surprising that the ngn3 deficiency seen in _hnf6_−/− embryos is associated with impaired endocrine differentiation. To explain the pancreatic endocrine phenotype of the _hnf6_−/− embryos, we propose that the absence of HNF-6 leads, in most cells, to a reduction of ngn3 gene expression below the threshold required to induce endocrine differentiation. In a few cells, ngn3 expression would be above the threshold, consistent with the known cell-to-cell variation in transcriptional response of a particular gene (5). In these cells, endocrine differentiation would be initiated and allowed to proceed along the next steps characterized by expression of differentiation markers such as Pax-6 and Isl-1. The low number of cells that express these markers at e12.5 and e15.5 would therefore reflect the reduction in the number of precursor cells that have entered the endocrine differentiation pathway.

From our in situ hybridization experiments, we conclude that all cells of the pancreatic epithelium at e14.5 express hnf6 but only a fraction express ngn3. This raises the question as to how ngn3 gene activation by HNF-6 is restricted to a subpopulation of HNF-6-expressing cells. The uniform distribution of hnf6 expression throughout the epithelium may suggest that HNF-6 acts as an accessory protein for a cell-type-restricted transcription factor with which it would cooperate to activate the ngn3 gene promoter. Alternatively, the activity of HNF-6 could be modulated by cell-type-specific mechanisms.

According to the lateral specification model (see above), hes1 is activated by Notch and represses endocrine differentiation (3, 17). However, the broad expression of hes1 in the pancreatic epithelium, including in cells that are not in contact with differentiating endocrine cells, suggested that the role of hes1 is not restricted to lateral specification (17). Our data on _hnf6_−/− mice further support this interpretation. Indeed, according to the lateral specification model, one would expect reduced expression of ngn3 to be associated with reduced expression of hes1. This was not the case in the _hnf6_−/− mice. Our data therefore clearly point to the existence of Ngn-3-independent mechanisms of hes1 gene activation.

After birth, the number of endocrine cells increased in the pancreas of _hnf6_−/− mice. These cells were observed near enlarged ducts and near cysts. They were most likely at the origin of the islets formed postnatally in the _hnf6_−/− mice. Endocrine cells located near ducts have been observed in rats during pancreas regeneration after partial pancreatectomy (4). The presence of endocrine cells within the cystic epithelium of _hnf6_−/− mice suggests that it retained some differentiation potential. However, most of the cells lining the cysts expressed pdx1 and glut2, but not insulin, suggesting that these cells had failed to complete differentiation. No expression of ngn3 was detected by RT-PCR or by in situ hybridization in the pancreas of _hnf6_−/− mice after birth (data not shown). Other factors of the ONECUT class have been identified in humans (14), and their expression in the pancreas should be analyzed to determine if they may participate in the control of pancreatic development.

HNF-6 stimulates _hnf3_β (20, 30) and HNF-3β stimulates pdx1 in the pancreas (36). This suggested that HNF-6 could control indirectly pdx1 gene expression. Our data would dismiss this hypothesis since expression of pdx1, as shown here, and of _hnf3_β (data not shown) was unaffected in _hnf6_−/− embryos. However, we cannot exclude that a HNF-6→HNF-3β→Pdx-1 cascade functions in wild-type embryos and that, in the absence of HNF-6, activation of the _hnf3_β gene is compensated for by other factors.

Glucose homeostasis was perturbed in _hnf6_−/− mice. At birth, their insulinemia was very low, consistent with the low number of pancreatic β cells. Contrary to what has been observed in knockout mice that have few or no β cells (10, 18, 24, 31, 33), the newborn _hnf6_−/− mice were hypoglycemic both in the fasted (Fig. 6) and in the fed (data not shown) state. Blood glucose levels depend on the balance between intestinal glucose transport, glucose consumption, and hepatic gluconeogenesis. Understanding the mechanisms by which newborn _hnf6_−/− mice control glucose homeostasis therefore requires characterization of these parameters. The fact that fasted newborn _hnf6_−/− mice did survive rules out hypoglycemia as a cause of the high mortality rate (75%) seen between P1 and P10. It is more likely that these mice die from liver failure. Indeed, work in progress in our laboratory suggests that _hnf6_−/− mice have a variable liver phenotype characterized by abnormal biliary differentiation and liver necrosis.

The pancreatic phenotype in newborn animals is transient. Five- to ten-week-old mice had islets of Langerhans, but they became diabetic. They had normal levels of pancreatic glucokinase mRNA (data not shown). However, full differentiation was not reached since islet morphology was abnormal and since IAPP was not expressed in several β cells. Moreover, the glucose transporter Glut-2 was barely detectable in the β cells of _hnf6_−/− mice. This may, at least in part, explain their diabetic phenotype. Indeed, Glut-2-deficient mice have diabetes because of a decreased glucose-induced insulin response (12), as seen here in the _hnf6_−/− mice. We conclude from our work that HNF6 is a candidate gene for diabetes mellitus in humans.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank L. Hue, J. C. Henquin, and J. Rahier for discussions and C. Bouzin, S. Fierens, V. Lannoy, L. Maisin, Y. Peignois, E. Gils, T. Vancoetsem, and K. Wijnens for help. Anti-Pax-6 and anti-Glut-2 antibodies were from S. Saule and B. Thorens, respectively. The monoclonal antibodies against Isl-1 and Nkx2.2, developed by T. Jessel, were obtained from the DSHB developed under the auspices of NICHM and maintained at the University of Iowa.

This work was supported by grants from the Belgian State Program on Interuniversity Poles of Attraction, the D.G. Higher Education and Scientific Research of the French Community of Belgium, the Fund for Scientific Medical Research, and the National Fund for Scientific Research (Belgium). O.D.M. and J.J. were supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Juvenile Diabetes Foundation. G.G. and F.G. were supported by a grant from the Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer, by funds from the Institut National de la Recherche Scientifique, from the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, and from the Hôpital Universitaire de Strasbourg. F.P.L. is Senior Research Associate of the National Fund for Scientific Research (Belgium).

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahlgren U, Pfaff S L, Jessell T M, Edlund T, Edlund H. Independent requirement for Isl1 in formation of pancreatic mesenchyme and islet cells. Nature. 1997;385:257–260. doi: 10.1038/385257a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahlgren U, Jonsson J, Jonsson L, Simu K, Edlund H. β-Cell-specific inactivation of the mouse Ipf1/Pdx1 gene results in loss of the β-cell phenotype and maturity onset diabetes. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1673–1768. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.12.1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Apelqvist A, Li H, Sommer L, Beatus P, Anderson D J, Honjo T, Hrabe de Angelis M, Lendahl U, Edlund H. Notch signalling controls pancreatic cell differentiation. Nature. 1999;400:877–881. doi: 10.1038/23716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonner-Weir S, Baxter L A, Schuppin G T, Smith F E. A second pathway for regeneration of adult exocrine and endocrine pancreas. Diabetes. 1993;42:1715–1720. doi: 10.2337/diab.42.12.1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boyd K E, Farnham P J. Coexamination of site-specific transcription factor binding and promoter activity in living cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:8393–8399. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.12.8393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carmeliet P, Ferreira V, Breier G, Pollefeyt S, Kieckens L, Gertsenstein M, Fahrig M, Vandenhoeck A, Harpal K, Eberhardt C, Declercq C, Pawling J, Moons L, Collen D, Risau W, Nagy A. Abnormal blood vessel development and lethality in embryos lacking a single VEGF allele. Nature. 1996;380:435–439. doi: 10.1038/380435a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cau E, Gradwohl G, Fode C, Guillemot F. Mash1 activates a cascade of bHLH regulators in olfactory neuron progenitors. Development. 1997;124:1611–1621. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.8.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edlund H. Transcribing pancreas. Diabetes. 1998;47:1817–1823. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.12.1817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fode C, Ma Q, Casarosa S, Ang S-L, Anderson D J, Guillemot F. A role for neural determination genes in specifying the dorsoventral identity of telencephalic neurons. Genes Dev. 2000;14:67–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gradwohl G, Dierich A, LeMeur M, Guillemot F. Neurogenin3 is required for the development of the four endocrine cell lineages of the pancreas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1607–1611. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.4.1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Groop L, Lehto M. Molecular and physiological basis for maturity onset diabetes of youth. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes. 1999;6:157–162. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guillam M T, Hümmler E, Schaerer E, Wu J-Y, Birnbaum M J, Beermann F, Schmidt A, Dériaz N, Thorens B. Early diabetes and abnormal postnatal pancreatic islet development in mice lacking Glut-2. Nat Genet. 1997;17:327–330. doi: 10.1038/ng1197-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harrison K A, Thaler J, Pfaff S L, Gu H, Kehrl J H. Pancreas dorsal lobe agenesis and abnormal islets of Langerhans in Hlxb9-deficient mice. Nat Genet. 1999;23:71–75. doi: 10.1038/12674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacquemin P, Lannoy V J, Rousseau G G, Lemaigre F P. OC-2, a novel mammalian member of the ONECUT class of homeodomain transcription factors whose function in liver partially overlaps with that of HNF-6. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:2665–2671. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.5.2665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jensen J, Serup P, Karlsen C, Funder Nielsen T, Madsen O D. mRNA profiling of rat islet tumors reveals Nkx6.1 as a β-cell-specific homeodomain transcription factor. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:18749–18758. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.31.18749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jensen J, Heller R S, Funder-Nielsen T, Pedersen E E, Lindsell C, Weinmaster G, Madsen O D, Serup P. Independent development of pancreatic α- and β-cells from neurogenin3-expressing precursors. A role for the Notch pathway in repression of premature differentiation. Diabetes. 2000;49:163–176. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jensen J, Pedersen E E, Galante P, Hald J, Heller R S, Ishibashi M, Kageyama R, Guillemot F, Serup P, Madsen O D. Control of endodermal endocrine development by hes-1. Nat Genet. 2000;24:36–44. doi: 10.1038/71657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jonsson J, Carlsson L, Edlund T, Edlund H. Insulin-promoter-factor 1 is required for pancreas development in mice. Nature. 1994;371:606–609. doi: 10.1038/371606a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krapp A, Knöfler M, Ledermann B, Bürki K, Berney C, Zoerkler N, Hagenbüchle O, Wellauer P. The bHLH protein PTF1-p48 is essential for the formation of the exocrine and the correct spatial organization of the endocrine pancreas. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3752–3763. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.23.3752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Landry C, Clotman F, Hioki T, Oda H, Picard J J, Lemaigre F P, Rousseau G G. HNF-6 is expressed in endoderm derivatives and nervous system of the mouse embryo and participates to the cross-regulatory network of liver-enriched transcription factors. Dev Biol. 1997;192:247–257. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lannoy V J, Bürglin T R, Rousseau G G, Lemaigre F P. Isoforms of HNF-6 differ in DNA-binding properties, contain a bifunctional homeodomain and define the new ONECUT class of homeodomain proteins. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13552–13562. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.22.13552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lemaigre F P, Durviaux S M, Truong O, Lannoy V J, Hsuan J J, Rousseau G G. Hepatocyte nuclear factor-6, a transcription factor that contains a novel type of homeodomain and a single cut domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9460–9464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li H, Jessell T M, Edlund H. Selective agenesis of the dorsal pancreas in mice lacking homeobox gene Hlxb9. Nat Genet. 1999;23:67–70. doi: 10.1038/12669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Naya F J, Huang H P, Qiu Y, Mutoh H, DeMayo F J, Leiter A B, Tsai M-J. Diabetes, defective pancreatic morphogenesis, and abnormal enteroendocrine differentiation in BETA2/NeuroD-deficient mice. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2323–2334. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.18.2323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nielsen J H, Serup P. Molecular basis for islet development, growth, and regeneration. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes. 1998;5:97–107. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Offield M F, Jetton T L, Labosky P A, Ray M, Stein R W, Magnuson M A, Hogan B L M, Wright C V E. PDX-1 is required for pancreatic outgrowth and differentiation of the rostral duodenum. Development. 1996;122:983–995. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.3.983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Øster A, Jensen J, Serup P, Galante P, Madsen O D, Larsson L-I. Rat endocrine pancreatic development in relation to two homeobox gene products (Pdx1 and Nkx6.1) J Histochem Cytochem. 1998;46:707–715. doi: 10.1177/002215549804600602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pang K, Mukonoweshuro C, Wong G G. Beta cells arise from glucose transporter type 2 (Glut2)-expressing epithelial cells of the developing rat pancreas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:9559–9563. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.20.9559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pictet R L, Rutter W J. Development of the endocrine pancreas. In: Steiner D, Freinkel N, editors. Handbook of physiology: the endocrine pancreas. Baltimore, Md: Williams & Wilkins; 1972. pp. 25–66. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rausa F, Samadani U, Ye H, Lim L, Fletcher C F, Jenkins N A, Copeland N G, Costa R H. The cut-homeodomain transcriptional activator HNF-6 is coexpressed with its target gene HNF-3β in the developing murine liver and pancreas. Dev Biol. 1997;192:228–246. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sander M, Neubüser A, Kalamaras J, Ee H C, Martin G R, German M S. Genetic analysis reveals that Pax6 is required for normal transcription of pancreatic hormone genes and islet development. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1662–1673. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.13.1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Slack J M W. Developmental biology of the pancreas. Development. 1995;121:1569–1580. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.6.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sosa-Pineda B, Chowdury K, Torres M, Oliver G, Gruss P. The Pax4 gene is essential for differentiation of insulin-producing β cells in the mammalian pancreas. Nature. 1997;386:399–402. doi: 10.1038/386399a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.St-Onge L, Sosa-Pineda B, Chowdury K, Gruss P. Pax6 is required for the differentiation of glucagon-producing α-cells in mouse pancreas. Nature. 1997;387:406–409. doi: 10.1038/387406a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sussel L, Kalamaras J, Hartigan-O'Connor D J, Meneses J J, Pedersen R A, Pedersen J L R, German M S. Mice lacking the homeodomain transcription factor Nkx2.2 have diabetes due to arrested differentiation of pancreatic β cells. Development. 1998;125:2213–2221. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.12.2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu K L, Gannon M, Peshavaria M, Offield M F, Henderson E, Ray M, Marks A, Gamer L W, Wright C V E, Stein R. Hepatocyte nuclear factor 3β is involved in pancreatic β-cell-specific transcription of the pdx1 gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6002–6013. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.10.6002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]