Global Prevalence of Chronic Kidney Disease – A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (original) (raw)

Abstract

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a global health burden with a high economic cost to health systems and is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD). All stages of CKD are associated with increased risks of cardiovascular morbidity, premature mortality, and/or decreased quality of life. CKD is usually asymptomatic until later stages and accurate prevalence data are lacking. Thus we sought to determine the prevalence of CKD globally, by stage, geographical location, gender and age. A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies estimating CKD prevalence in general populations was conducted through literature searches in 8 databases. We assessed pooled data using a random effects model. Of 5,842 potential articles, 100 studies of diverse quality were included, comprising 6,908,440 patients. Global mean(95%CI) CKD prevalence of 5 stages 13·4%(11·7–15·1%), and stages 3–5 was 10·6%(9·2–12·2%). Weighting by study quality did not affect prevalence estimates. CKD prevalence by stage was Stage-1 (eGFR>90+ACR>30): 3·5% (2·8–4·2%); Stage-2 (eGFR 60–89+ACR>30): 3·9% (2·7–5·3%); Stage-3 (eGFR 30–59): 7·6% (6·4–8·9%); Stage-4 = (eGFR 29–15): 0·4% (0·3–0·5%); and Stage-5 (eGFR<15): 0·1% (0·1–0·1%). CKD has a high global prevalence with a consistent estimated global CKD prevalence of between 11 to 13% with the majority stage 3. Future research should evaluate intervention strategies deliverable at scale to delay the progression of CKD and improve CVD outcomes.

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is associated with age-related renal function decline accelerated in hypertension, diabetes, obesity and primary renal disorders. [1] Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the primary cause of morbidity and mortality where CKD is regarded as an accelerator of CVD risk and an independent risk factor for CVD events. [2] There is a graded inverse relationship between CVD risk and glomerular filtration rate (GFR) that is independent of age, sex and other risk factors. [3–6] Decreased renal function is a predictor of hospitalisation [1, 2], cognitive dysfunction [7] and poor quality of life. [8, 9] The healthcare burden is highest in early stages due to increased prevalence, affecting around 35% of those over 70 years. [10]

CKD is defined by indicators of kidney damage—imaging or proteinuria (commonly using albumin to creatinine ratio, ACR)—and decreased renal function (below thresholds of GFR estimated from serum creatinine concentration). [11, 12] Current recommendations by Kidney Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI) and National Institute for Health Excellence (NICE) [11, 12] are to use serum creatinine concentration to estimate GFR (eGFR) and transform it using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation. [13] CKD-EPI replaces the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) equation [14] as a more accurate predictor of clinical risk [15] and both these equations correct for selected non-renal influences (age, race, gender).

CKD can be classified into five stages using KDOQI [11] guidelines using thresholds of eGFR within the CKD range and/or evidence of structural renal changes e.g. proteinuria. NICE have suggested that stage 3 be subdivided into 3a and 3b reflecting increasing CVD risk. [12] The largest stage of CKD, with over 90% of cases, has been estimated from a UK retrospective lab audit study to be CKD stage 3 with 84% stage 3a (GFR of 45 to 59 ml/min/1·73m2) and 16% stage 3b GFR of 30 to 44 ml/min/1·73m2. [16]

Changes over time in CKD prevalence are contentious. Data from the American National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey demonstrate that in the period 1999 to 2004 the prevalence of CKD stages 1 to 4 increased significantly when compared to the survey period 1988 to 1994 (13·1 versus 10·0%). [4, 17, 18] While this high (and rising 4,) prevalence is in part due to the ageing population, it is also associated with increases in hypertension and diabetes mellitus[1]. However, conversely a UK manuscript published in 2014 examined nationally representative cross-sectional studies within the UK and found that the prevalence estimates reported declined over time. [19]

CKD is recognised as having changed from a subspecialty issue to a global health concern. [20] The authors, therefore, sought to determine the global prevalence of CKD according to KDOQI criteria in published observational studies in the adult general population, by a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Materials and Methods

Search strategy and selection criteria

The protocol has been published (PROSPERO: CRD42014009184) and conducted in accordance with the Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines [21]. Search strategy was discussed with a librarian for optimum inclusion sensitivity. An early consensus panel on the search results expanded the criteria to include additional general populations not identified originally (e.g. laboratory based large population studies). The librarian performed iterative searches using the following repositories for published observational studies: Medline/PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, the Cochrane Register for Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), LILACS, SciELO, clinicaltrials.gov, WHO ICTRP. They used the Cochrane Collaboration’s Highly Sensitive Search Strategy to optimize results. [22] The search strategy for clinicaltrials.gov was Condition = (“kidney disease” OR “kidney failure” OR “kidney insufficiency” OR “kidney function” OR “kidney dysfunction” OR “renal disease” OR “renal failure” OR “renal insufficiency” OR “renal function” OR “renal dysfunction”) AND Outcome = prevalence. The reference lists of other systematic reviews on prevalence of CKD were searched for potentially relevant articles. All databases were searched from inception to the 1st September 2014.

Study selection and data extraction

Original peer-reviewed publications were selected by two authors (NH, SF) if they included: a >500 people, conducted from year 2000+, used MDRD/CKD-EPI formula, reported CKD prevalence using KDOQI criteria and were in the general population (even if limited—e.g. aged >65). Studies were excluded if they had no criteria for diagnosis of CKD, did not include prevalence, were in a specialist restricted population (e.g. acute hospital patient cohort, nursing home), were an audit of existing results already included or if there was a more recent updated study. Translations were sought for non-English articles.

Data extraction was with standardised forms by two independent reviewers (NH, SF) disagreement was resolved by adjudicator (DL). Data included quality assessment, prevalence of CKD, method used to calculate eGFR, study setting: year, country, the population, gender split, age, and so on. Authors of relevant articles were contacted to provide additional information whenever necessary and references of selected articles were hand searched for additional articles. The KDOQI definition of CKD stages was used [11] and the method, calibration and traceability of the creatinine assessment extracted.

Statistical analysis and quality assessment

CKD prevalence was defined by the studies as being calculated for Stages 1 to 5 (eGFR & ACR) or Stages 3 to 5 (eGFR alone). 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) were calculated for each prevalence value. Meta-analyses were performed in Stata version 14. A procedure for pooling proportions in the meta-analysis of multiple studies study was used and the results displayed in a forest plot. The 95%CI’s are based on score(Wilson) procedures [23]. Heterogeneity was quantified using the I-squared measure, The I2 heterogeneity was categorised as follows: <25% low, 25 to 50% moderate and >50% high [24]. A Freeman-Tukey Double Arcsine Transformation [25] was used to stabilise the variance prior to calculation of the pooled estimates. Random effects models were selected for the meta-analyses with the assumption that CKD prevalence by country would be variable.

Subgroup analysis was undertaken by country, geographic region, age and gender. Geographic regions were defined based on the geographic proximity of the country the studies occurred in and the possible similarity in the ethnicity of the populations. Meta-regression was weighted by number of subjects unless otherwise specified [24]. Random effects meta-regressions using aggregate level data for CKD prevalence, study year, participant characteristics and co-morbidities were performed.

Methodological quality was assessed by one reviewer (NH) defined as adherence to STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology Statement) recommendations. [26] The STROBE 22-point checklist was used to score each manuscript, items that had subdivision recommendations scored a point for each. Serum creatinine reporting quality was assessed by two reviews (NH & SF)—traceability of assay, number of measurements per patient, assay method used, and calibration of assay. A combined quality score was generated from methodological quality- as measured by STROBE adherence- and serum creatinine reporting quality. The weighting was arbitrarily chosen to be two-thirds STROBE adherence and one-third creatinine reporting. To assess bias, quality was used to weight CKD prevalence values in a meta-analysis.

Sensitivity analyses were undertaken to investigate the individual study influence and of limited populations (high altitude, single site of recruitment in rural area, single site of recruitment in urban area, laboratory audit, age by decile, or age restricted), studies that used age adjusted prevalence and using only high quality studies—quality score threshold of 56% (mean quality). Further sensitivity analyses were undertaken using studies that examined IDMS traceable creatinine only, studies that used double measuring of creatinine, studies that achieved two or more of the serum creatinine reporting quality items, and studies that used different eGFR equations (CKD-EPI or MDRD).

Results

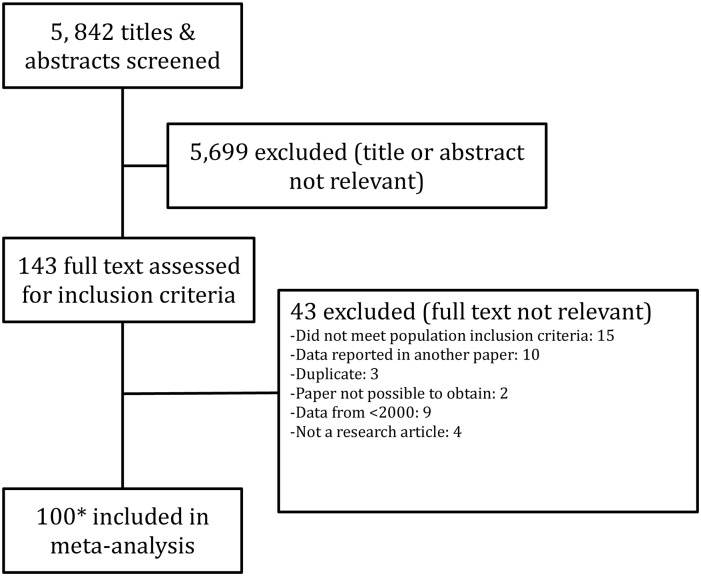

The search yielded 5,842 articles after duplicates had been removed and 143 articles were assessed relevant for the review by title and abstract. Forty-three were excluded on full manuscript assessment. A detailed review and data extraction was conducted on 100 manuscripts (covering 112 populations), Fig 1. No additional studies were identified by examining reference lists. All studies that were included were published after the introduction of the KDOQI 2002 CKD definition guidelines [11].

Fig 1. Systematic review flow diagram of manuscripts screened, excluded and included in meta-analysis.

*112 Populations from 100 manuscripts as some manuscripts reported on more than one population or split their populations prior to analysis.

China had the highest number of population samples with seventeen. [27–43] Numbers of participants ranged from 778 in a USA cohort [44] to 1,120,295 in a USA laboratory audit [2]. The S1 Appendix Study Table details the relevant details of all studies and populations.

Prevalence

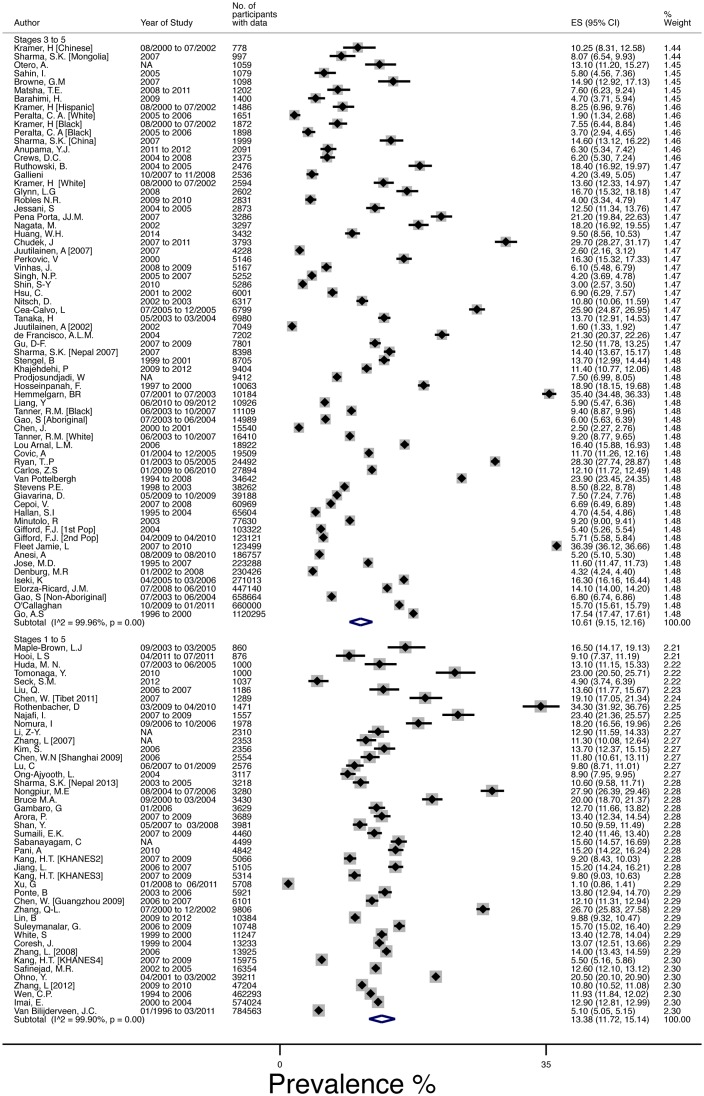

The mean(95%CI) global prevalence of CKD was 13·4%(11·7–15·1%), I2 = 99.9%, for the forty-four populations that measured prevalence by all 5 stages (1 to 5) [4, 28, 29, 32, 33, 35–38, 40–43, 45–73], and 10·6%(9·2–12·2%),I2 = 100%, in the sixty-eight populations [2, 10, 27, 30, 31, 34, 39, 44, 74–123] measuring Stages 3 to 5, Fig 2.

Fig 2. Meta Analysis of CKD prevalence using random effects model, weighted by standard error of the mean estimates.

Studies are ordered by number of participants and split by whether the report 3 stages of CKD (“Three”) or five stages of CKD (“Five”).

CKD prevalence breakdown was provided in seventy-four populations. [2, 4, 10, 27–29, 32, 35, 37–43, 46, 47, 50–56, 60, 63, 65–71, 73–84, 86–91, 98–102, 106–111, 113, 116, 118, 121, 122] The 1 to 5 stages mean CKD prevalence was higher (13·4% vs. 11·0%). The breakdown by stage using all available data was Stage-1 (eGFR>90+ACR>30): 3·5%(2·8–4·2%); Stage-2 (eGFR 60–89+ACR>30): 3·9%(2·7–5·3%); Stage-3 (eGFR 30–59): 7·6%(6·4–8·9%); Stage-4 = (eGFR 29–15): 0·4%(0·3–0·5%); and Stage-5 (eGFR<15): 0·1%(0·1–0·1%). Separate reporting of Stage 3a/3b was not possible due to lack of reporting. Sensitivity analyses determined that no individual study or group of studies (limited populations—i.e. laboratory audits, age restricted, single site recruitment—, age adjusted prevalence, etc.) were suspected of excess influence on the prevalence estimates. Further, there was no difference between studies that reported using the higher quality IDMS traceable assay and those that did not.

Effect of Age, Hypertension, BMI, Obesity, Diabetes, Smoking

Univariate meta-regressions of CKD prevalence and covariates were undertaken. Mean population age, given in 94 of 112 populations, was significantly associated (β = 0·4%, p<0·001, R2 = 25·5), as was prevalence of diabetes (n = 82, β = 0·16%, p = 0·006, R2 = 8·0), prevalence of hypertension (n = 75, β = 0·15%, p = 0·002, R2 = 11·4) but not average BMI or prevalence of obesity. Smoking (n = 60) was negatively associated with CKD prevalence (an increase of smoking status was associated with a decreased prevalence of CKD (β = -0·14 p = 0·07, R2 = 4·2).

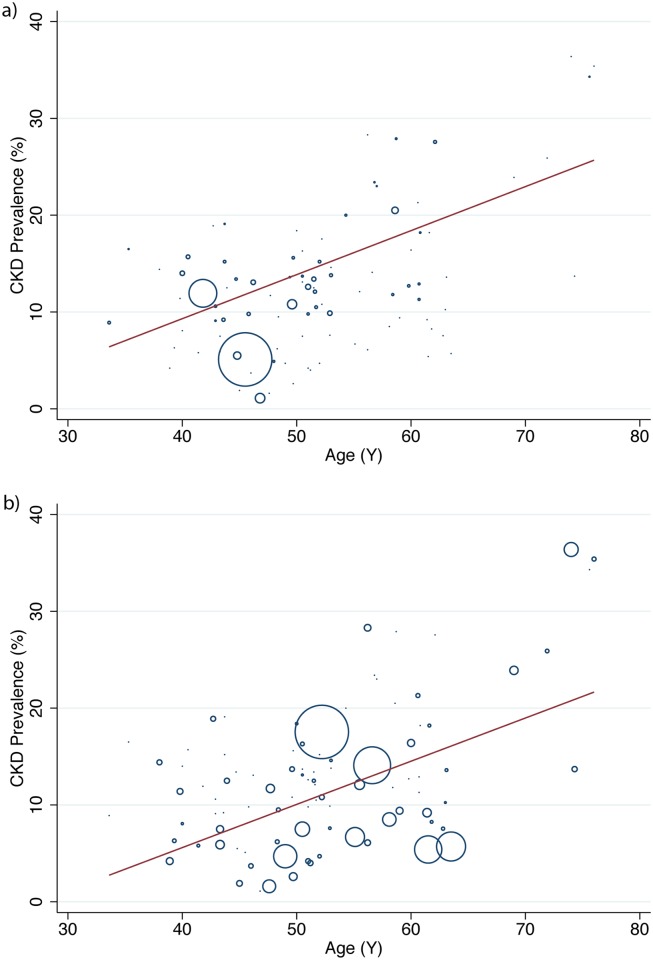

Prevalence of CKD increased with age, Fig 3. To determine an estimated prevalence for each age the sample population was divided by mean age into deciles. Studies measuring 5 stages of CKD mean(95%CI) were—30s: 13·7%(10·8, 16·6%), 40s: 12·0%(9·9, 14·1%), 50s: 16·0%(13·5, 18·4%), 60s: 27·6%(26·7, 28·5%), 70s: 34·3%(31·9, 36·7%). Studies measuring stages 3 to 5–30s: 8·9%(4·7, 13·1%), 40s: 8·7%(6·9, 10·5%), 50s: 12·2%(9·8, 14·5%), 60s: 11·3%(8·1, 14·5%), 70s: 27·9%(16·40, 39·3%).

Fig 3. Meta Regression of CKD Prevalence and mean sample population age (a) Studies reporting stages 1 to 5 (b) Studies reporting stages 3 to 5.

Each circle represents a study prevalence estimate with the size denoting the precision of the estimate.

There were no significant differences in prevalence between groups of studies that adjusted for age compared to those that did not. Further, a sensitivity test found that older age restricted populations did not significantly change the estimated pooled prevalence for CKD, Stages 3 to 5 mean (95%CI) 10·2%(8·4–12·0%) vs. 10·6%(9·2–12·2%) and stages 1 to 5 mean (95%CI) 11·5%(9·3–13·9%) vs. 11·4%(9·4–13·1%). A sensitivity analysis examining glomerular filtration estimating equation was planned but only 12 studies used the CKD-EPI equation making the analysis unfeasible.

Geography

CKD prevalence by geographical grouping was examined, Table 1. Geographical areas with more than one study were pooled using random effects models.

Table 1. Mean prevalence of CKD split by geographical region with 95% Confidence Intervals.

| Stage 1 to 5 | Stages 3 to 5 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N* | Prevalence (%) | N* | Prevalence (%) | |

| S Africa, Senegal, Congo | 5,497 | 8.66 (1.31, 16.01) | 1,202 | 7.60 (6.10, 9.10) |

| India, Bangladesh | 1,000 | 13.10 (11.01, 15.19) | 12,752 | 6.76 (3.68, 9.85) |

| Iran | 17,911 | 17.95 (7.37, 28.53) | 20,867 | 11.68 (4.51, 18.84) |

| Chile | 0 | NONE | 27,894 | 12.10 (11.72, 12.48) |

| China, Taiwan, Mongolia | 570,187 | 13.18 (12.07, 14.30) | 62,062 | 10.06 (6.63, 13.49) |

| Japan, S Korea, Oceania | 654,832 | 13.74 (10.75, 16.72) | 298,000 | 11.73 (5.36, 18.10) |

| Australia | 12,107 | 14.71 (11.71, 17.71) | 896,941 | 8.14 (4.48, 11.79) |

| USA, Canada | 20,352 | 15.45 (11.71, 19.20) | 1,319,003 | 14.44 (8.52, 20.36) |

| Europe | 821,902 | 18.38 (11.57, 25.20) | 2,169,183 | 11.86 (9.93, 13.79) |

Gender

Fifty-one studies reported sex-specific prevalence of CKD. [27–29, 32, 37–39, 44, 46, 48, 50, 52–55, 57, 58, 61, 64, 68–71, 78, 79, 82, 83, 85, 87, 92–94, 98, 100–103, 105, 106, 108, 110, 115, 119] Male mean (95%CI) CKD prevalence, for studies that defined 5 stages of CKD, was 12·8%(10·8–11·9%) and for studies that used stages 3 to 5 it was 8·1%(6·3–10·2%). Female CKD prevalence for studies that defined CKD by stages 1 to 5 was 14·6%(12·7–16·7%) and for studies that used stages 3 to 5 it was 12·1%(10·6–13·8%). Thirty-eight studies [27–29, 32, 37–39, 44, 46, 50, 55, 64, 69–71, 78, 79, 83, 85, 87, 92, 98, 100–103, 105, 106, 108, 110, 115, 119] reported that CKD was more prevalent in women than in men with the pattern reversed in thirteen studies. [39, 44, 48, 52–54, 57, 58, 61, 68, 82, 93, 94]

Quality

The methodological quality of studies ranged from 32·1% [31] to 92·9%. [4, 68] No study complied completely with the STROBE guidelines and the mean(SD) quality was 69·6(12·5)%.

Quality of serum creatinine measurement was assessed. Two studies scored 100%- four methods. [115, 122] Thirty-six studies scored 0% [30–32, 34, 39, 40, 48, 49, 52, 57–60, 62, 64, 71, 72, 74, 76, 81, 82, 85, 87, 89, 92, 95, 102, 103, 105, 106, 109, 113, 116, 117], thirty-five studies scored 25%-one method-[2, 28, 29, 33, 35–38, 41, 43, 47, 51, 53, 61, 65, 67–70, 75, 77–79, 83, 84, 97–100, 108, 110, 114, 121], twenty-seven scored 50%-two methods-[4, 27, 42, 44, 46, 50, 54–56, 66, 74, 80, 88, 90, 101, 104, 107, 111, 112, 118, 119, 123] and ten scored 75%-three methods. [10, 45, 63, 73, 86, 91, 93, 94, 96, 120]

Sensitivity analyses determined no difference in the prevalence estimate of CKD when using only high quality studies, studies that used double measures of creatinine only or studies that had two or more factors for the measurement of creatinine.

Discussion

CKD prevalence Stages 1 to 5 was 13·4% and 10·6% in stages 3 to 5. This systematic review is the first meta-analysis of CKD prevalence globally and provides a comprehensive overview of the current literature. These estimates indicate that CKD may be more common than diabetes, which has an estimated prevalence of 8·2%. [124] However, the reported prevalence of CKD varied widely amongst the studies and had high heterogeneity.

CKD was more prevalent in women than in men. Two-thirds of studies -that reported gender-specific CKD prevalence- determined higher prevalence in women. Women, in general, have less muscle mass than men and muscle mass is a major determinant of serum creatinine concentration. However, the GFR estimation equations adjust for gender differences, using a correction factor for women. These findings add to the existing literature that recognise a gender-specific difference between CKD prevalence. [125–127]However, these data cannot answer why this may occur. We can speculate that this finding may be partially explained by selection bias inherent within the studies due to a different age demographic for the two sexes. Alternatively it may be due to complex factors in the disease pathology that are not captured within the studies. Or that there is in fact more renal disease in men but the eGFR equations preferentially identify renal disease in women in the stage 3 zones.

Studies that were outliers in terms of reported results were of interest. Smoking was found to be negatively associated with CKD prevalence but this finding was negated when a single outlier was removed. The outlier [120] was a study in which smoking was defined as >100 cigarettes ever and thus 69·1% were smokers. A Spanish study [106] (n: 7202, Quality: 52%, CKD: 21·3%) reported 66.7% hypertension prevalence within the population compared with a global mean (from all other studies) of 31·1%. Hypertension was not defined any differently. Further, 31.5% of their sample population had diabetes and 31.1% were obese. The population was reported as unrestricted older population but although it was older than other studies (mean age 60·6yrs) these rates of co-morbidity are unexpected and were not explained. A number of studies had very high prevalence of CKD (>30%) the highest of these was a Canadian study (n: 123,499, Quality: 52%, CKD: 36·4%), a laboratory audit of patients over 65 years. The prevalence observed may be due to selection bias as the mean age of this cohort was 74 years, with 23% diabetes in the sample population, two factors associated with renal decline.

The geographical stratification of results revealed that developed areas such as Europe, USA, Canada and Australia had higher rates of CKD prevalence in comparison to areas where economies are growing such as sub Saharan Africa, India etc. With the exception of Iran that had similar high level of CKD prevalence possibly due dietary risks, high BMI, high systolic BP and co-morbid conditions within the country [128]. Although percentage prevalence was higher in more developed areas projected worldwide population changes will increase the absolute numbers of people in developing countries where the populations of elderly are increasing. This increase will exacerbate the double burden of dealing with communicable and non communicable disease in a developing economy[129].

Serum creatinine measurement bias was inherent in the majority of the studies. Serum creatinine concentrations are highly variable within individuals, up to 21% within a 2-week period. [130] NICE guidelines advise two measures of eGFR 3-months apart and within the last 12-months to minimise intra-individual variation. Not all countries have such guidelines only 5 manuscripts reported this in study design. Jaffe creatinine assay was the main method used but it is known to systematically overestimate serum creatinine to varying degrees. [131] Thirty-seven of the studied populations reported that they calibrated directly to the laboratory to minimize assay bias effect and twenty-seven studies used a minimally biased traceably assay (IDMS). A comparison of these studies to the remainder found no significant difference in prevalence estimates. A third of the studies (n = 36) made no mention of measures, traceability, or calibrations. It is further known that the MDRD equation systematically overestimates CKD in the general population [13] and the prevalence rates calculated may be lower. Estimated GFR is accepted as the most useful index of kidney function in health and disease, but an uncorrected, untraceable single measure inherently introduces noise and outliers into the dataset. This latter point has been very recently clarified as an epidemiological study in Morocco found that up to 30% of patients initially classified as CKD 3a using the MDRD formula had improved renal function over 12 months and therefore would not have a CKD diagnosis[132].

Estimation of GFR from serum creatinine is the clinical standard worldwide and the CKD the KDOQI diagnostic criteria[11] guidelines emphasise the importance of estimation of GFR rather than use of serum creatinine concentration. However, the 2002 KDOQI guidelines that the included studies reference have stimulated controversies and questions. In particular, there have been concerns that use of its definition of CKD has caused excessive false identification of CKD and that its staging system was not sufficiently informative about prognosis. A new KDIGO guideline was published in 2013 [133] that sought to address this with the splitting of the stage 3 category to emphasise the risks of mortality and other outcomes vary greatly between these groups and have further and further sub-stratified by the inclusion of urinary albuminuria. There is a limitation in our study in that unfortunately the analysis of stages 3a and 3b was not possible due to lack of reporting and studies using the previous KDOQI guidelines so no conclusions about whether the patients really have ‘disease’ rather than normal variation due to aging could be drawn.

Observational studies are individually subject to bias and residual confounding from unspecified sources but it is difficult to quantify how much bias and/or confounding. One study may report an effect size adjusted for several possible confounders; others may report the crude prevalence. The authors have sought to address this limitation by using STROBE quality weighting and creatinine quality factors and participant per study-weighted rates. Ideally future research should report the crude and adjusted rates based on multiple measures over time.

This systematic review and meta-analysis significantly extends existing systematic reviews in a number of ways. The search strategy allowed the detection of a large number of additional studies that had not been considered in previous systematic reviews. It increased the number of reference databases searched. The reviewers undertook to screen non-English publications through the use of translations. The studies included used the same definitions of CKD and used broadly comparable definitions for severity markers or related conditions (albuminuria, hypertension, diabetes and obesity). However, there are limitations due to the heterogeneity that arises from differences in age and sex distributions, use of creatinine assays, different sampling frames, inclusion criteria of general population based studies, and time period of the study. A proportion of the variation across studies may not be due to real differences in CKD prevalence. However, the authors did seek to provide a robust assessment of the quality and use this to determine a weighted global prevalence of CKD in the meta-analysis. The prevalence rates calculated highlight the likely numbers of people with CKD that may be of relevance to health care providers and national health programs with finite resources with which to address this epidemic.

CKD constitutes a major cost burden to healthcare systems worldwide. The high prevalence and the extensive existing evidence that intervention is effective in reducing CVD events demonstrates a need for national initiatives that will slow the progression to end stage renal disease and reduce CVD-related events in CKD patients.

This comprehensive meta-analysis of observational studies confirms that CKD has a high prevalence. Using CKD prevalence weighted by quality, using ‘High’ quality studies only and using studies weighted by number of participants consistently estimated a global CKD prevalence of between 11 to 13%. Future research should evaluate intervention strategies deliverable at scale to delay the progression of CKD and improve CVD outcomes. Evaluation of the roles of these interventions and the associated costs needs to be undertaken. CKD prevalence studies should report more detail on disease definitions and population demographics and state unadjusted as well as adjusted findings.

Supporting Information

S1 Appendix. Study Table—Summary descriptions of included studies (n = 100) and the populations (n = 112) within those studies.

(DOCX)

S2 Appendix. PRISMA Checklist—Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses checklist.

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Ms. Nia Roberts for her extensive assistance in conducting the search and Dr Yaling Yang for her translation of a Chinese language manuscript. Systematic Review Registration: PROSPERO CRD42014009184.

Data Availability

All data are from Dryad (datadryad.org); the DOI number is doi:10.5061/dryad.3s7rd.

Funding Statement

NH is funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Oxford Biomedical Research Centre based at Oxford University Hospitals NHS Trust and University of Oxford. FDRH is part funded as Director of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) School for Primary Care Research (SPCR), Theme Leader in the NIHR Oxford Biomedical Research Centre (BRC), and Director of the NIHR Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) Oxford. DSL is part funded by the NIHR Oxford Diagnostic Evidence Co-operative and NIHR Oxford BRC. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Gansevoort RT, Correa-Rotter R, Hemmelgarn BR, Jafar TH, Heerspink HJ, Mann JF, et al. Chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular risk: epidemiology, mechanisms, and prevention. Lancet. 2013. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60595-4 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY. Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. The New England journal of medicine. 2004;351(13):1296–305. Epub 2004/09/24. 10.1056/NEJMoa041031 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matsushita K, van der Velde M, Astor BC, Woodward M, Levey AS, de Jong PE, et al. Association of estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in general population cohorts: a collaborative meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375(9731):2073–81. Epub 2010/05/21. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60674-5 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coresh J, Selvin E, Stevens LA, Manzi J, Kusek JW, Eggers P, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA. 2007;298(17):2038–47. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abramson JL, Jurkovitz CT, Vaccarino V, Weintraub WS, McClellan W. Chronic kidney disease, anemia, and incident stroke in a middle-aged, community-based population: the ARIC Study. Kidney Int. 2003;64(2):610–5. Epub 2003/07/09. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00109.x . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Biesen W, De Bacquer D, Verbeke F, Delanghe J, Lameire N, Vanholder R. The glomerular filtration rate in an apparently healthy population and its relation with cardiovascular mortality during 10 years. European heart journal. 2007;28(4):478–83. Epub 2007/01/16. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl455 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Etgen T, Chonchol M, Forstl H, Sander D. Chronic Kidney Disease and Cognitive Impairment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. American journal of nephrology. 2012;35(5):474–82. Epub 2012/05/05. 10.1159/000338135 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perlman RL, Finkelstein FO, Liu L, Roys E, Kiser M, Eisele G, et al. Quality of life in chronic kidney disease (CKD): a cross-sectional analysis in the Renal Research Institute-CKD study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;45(4):658–66. Epub 2005/04/05. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chin HJ, Song YR, Lee JJ, Lee SB, Kim KW, Na KY, et al. Moderately decreased renal function negatively affects the health-related quality of life among the elderly Korean population: a population-based study. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation: official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association—European Renal Association. 2008;23(9):2810–7. Epub 2008/03/29. 10.1093/ndt/gfn132 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Callaghan CA, Shine B, Lasserson DS. Chronic kidney disease: a large-scale population-based study of the effects of introducing the CKD-EPI formula for eGFR reporting. BMJ open. 2011;1(2):e000308 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.KDOQI KDOQI. Chronic Kidney Disease: Evaluation, Classification, and Stratification2002. Available: http://www.kidney.org/professionals/kdoqi/guidelines_commentaries.cfm.

- 12.NICE NIfCE. CG73 Chronic kidney disease: full guideline: 2008; 2008. [6th June 2012]. The published full clinical guideline on Chronic kidney disease including recommendations and methods used.]. Available: http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG73/Guidance/pdf/English.

- 13.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(9):604–12. Epub 2009/05/06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130(6):461–70. Epub 1999/03/13. 199903160–00002 [pii]. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsushita K, Tonelli M, Lloyd A, Levey AS, Coresh J, Hemmelgarn BR. Clinical risk implications of the CKD Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equation compared with the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) Study equation for estimated GFR. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60(2):241–9. Epub 2012/05/09. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.03.016 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Lusignan S, Tomson C, Harris K, Van Vlymen J, Gallagher H. UK Prevalence of Chronic Kidney Disease for the Adult Population Is 6.76% Based on Two Creatinine Readings [Erratum]. Nephron Clinical practice. 2012;120:c107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coresh J, Byrd-Holt D, Astor BC, Briggs JP, Eggers PW, Lacher DA, et al. Chronic kidney disease awareness, prevalence, and trends among U.S. adults, 1999 to 2000. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(1):180–8. Epub 2004/11/26. 10.1681/ASN.2004070539 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coresh J, Astor BC, Greene T, Eknoyan G, Levey AS. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease and decreased kidney function in the adult US population: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2003;41(1):1–12. 10.1053/Ajkd.2003.50007 ISI:000180161100001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aitken GR, Roderick PJ, Fraser S, Mindell JS, O'Donoghue D, Day J, et al. Change in prevalence of chronic kidney disease in England over time: comparison of nationally representative cross-sectional surveys from 2003 to 2010. BMJ open. 2014;4(9):e005480 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eckardt KU, Coresh J, Devuyst O, Johnson RJ, Kottgen A, Levey AS, et al. Evolving importance of kidney disease: from subspecialty to global health burden. Lancet. 2013;382(9887):158–69. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60439-0 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008–12. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Higgins JP, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions: Wiley-Blackwell; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Newcombe RG. Two-sided confidence intervals for the single proportion: comparison of seven methods. Statistics in medicine. 1998;17(8):857–72. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freeman MF, Tukey JW. Transformations related to the angular and the square root. Annals of Mathematical Statistics. 1950;(21):607–11. [Google Scholar]

- 26.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Epidemiology. 2007;18(6):800–4. Epub 2007/12/01. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen J, Wildman RP, Gu D, Kusek JW, Spruill M, Reynolds K, et al. Prevalence of decreased kidney function in Chinese adults aged 35 to 74 years. Kidney International. 2005;68(6):2837–45. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen W, Chen W, Wang H, Dong X, Liu Q, Mao H, et al. Prevalence and risk factors associated with chronic kidney disease in an adult population from southern China. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2009;24(4):1205–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen N, Wang W, Huang Y, Shen P, Pei D, Yu H, et al. Community-based study on CKD subjects and the associated risk factors. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2009;24(7):2117–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gu D-F, Shi Y-L, Chen Y-M, Liu H-M, Ding Y-N, Liu X-Y, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease and prediabetes and associated risk factors: a community-based screening in Zhuhai, Southern China. Chinese Medical Journal. 2013;126(7):1213–9. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang WH, Tang L, Cai Y, Gong TJ, Jiang LN, Lu GY, et al. Epidemiology investigation and analysis of relevant factors of adult chronic kidney disease in Yuzhong District, Chongqing. [Chinese]. Journal of Shanghai Jiaotong University (Medical Science). 2014;34(5):725–30. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiang L, Liang Y, Qiu B, Wang F, Duan X, Yang X, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in a rural Chinese adult population: the Handan Eye Study. Nephron. 2010;114(4):c295–302. 10.1159/000276582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Z-Y, Xu G-B, Xia T-A, Wang H-Y. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in a middle and old-aged population of Beijing. Clinica Chimica Acta. 2006;366(1–2):209–15. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liang Y. Analysis of the prevalence rate and correlative risk factors of chronic kidney disease in physical checkups of adults in Henan area. Asia-Pacific Journal of Public Health. 2013;25(4 Suppl):15S–21S. 10.1177/1010539513495270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin B, Shao L, Luo Q, Ou-yang L, Zhou F, Du B, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease and its association with metabolic diseases: a cross-sectional survey in Zhejiang province, Eastern China. BMC nephrology. 2014;15(1):36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu Q, Li Z, Wang H, Chen X, Dong X, Mao H, et al. High prevalence and associated risk factors for impaired renal function and urinary abnormalities in a rural adult population from southern China. PLoS ONE [Electronic Resource]. 2012;7(10):e47100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lu C, Zhao H, Xu G, Yue H, Liu W, Zhu K, et al. Prevalence and risk factors associated with chronic kidney disease in a Uygur adult population from Urumqi. Journal of Huazhong University of Science and Technology. 2010;Medical Sciences. 30(5):604–10. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shan Y, Zhang Q, Liu Z, Hu X, Liu D. Prevalence and risk factors associated with chronic kidney disease in adults over 40 years: A population study from Central China. Nephrology. 2010;15(3):354–61. 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2009.01249.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sharma SK, Zou H, Togtokh A, Ene-Iordache B, Carminati S, Remuzzi A, et al. Burden of CKD, proteinuria, and cardiovascular risk among Chinese, Mongolian, and Nepalese participants in the International Society of Nephrology screening programs. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;56(5):915–27. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.06.022 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu G, Chen Z, Zhang H, Gong N, Wang Y. [Chronic kidney disease in 5 708 people receiving physical examination]. Zhong Nan da Xue Xue Bao. 2014;Yi Xue Ban = Journal of Central South University. Medical Sciences. 39(4):408–15. 10.3969/j.issn.1672-7347.2014.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang L, Zuo L, Xu G, Wang F, Wang M, Wang S, et al. Community-based screening for chronic kidney disease among populations older than 40 years in Beijing. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2007;22(4):1093–9. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang L, Wang F, Wang L, Wang W, Liu B, Liu J, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in China: a cross-sectional survey.[Erratum appears in Lancet. 2012 Aug 18;380(9842):650]. Lancet. 2012;379(9818):815–22. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60033-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang L, Zhang P, Wang F, Zuo L, Zhou Y, Shi Y, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with CKD: a population study from Beijing. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2008;51(3):373–84. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kramer H, Palmas W, Kestenbaum B, Cushman M, Allison M, Astor B, et al. Chronic kidney disease prevalence estimates among racial/ethnic groups: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Clinical Journal of The American Society of Nephrology: CJASN. 2008;3(5):1391–7. 10.2215/CJN.04160907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maple-Brown LJ, Cunningham J, Hodge AM, Weeramanthri T, Dunbar T, Lawton PD, et al. High rates of albuminuria but not of low eGFR in urban indigenous Australians: the DRUID study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:346 10.1186/1471-2458-11-346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.White SL, Polkinghorne KR, Atkins RC, Chadban SJ. Comparison of the prevalence and mortality risk of CKD in Australia using the CKD Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) and Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) Study GFR estimating equations: the AusDiab (Australian Diabetes, Obesity and Lifestyle) Study. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2010;55(4):660–70. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huda MN, Alam KS, Harun Ur R. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease and its association with risk factors in disadvantageous population. International journal of nephrology. 2012;2012:267329 10.1155/2012/267329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Arora P, Vasa P, Brenner D, Iglar K, McFarlane P, Morrison H, et al. Prevalence estimates of chronic kidney disease in Canada: results of a nationally representative survey. CMAJ Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2013;185(9):E417–23. 10.1503/cmaj.120833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sumaili EK, Krzesinski J-M, Cohen EP, Nseka NM. [Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease in the Democratic Republic of Congo: review of cross-sectional studies from Kinshasa, the capital]. Nephrologie et Therapeutique. 2010;6(4):232–9. 10.1016/j.nephro.2010.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rothenbacher D, Klenk J, Denkinger M, Karakas M, Nikolaus T, Peter R, et al. Prevalence and determinants of chronic kidney disease in community-dwelling elderly by various estimating equations. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:343 10.1186/1471-2458-12-343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang Q-L, Koenig W, Raum E, Stegmaier C, Brenner H, Rothenbacher D. Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease: results from a population of older adults in Germany. Preventive Medicine. 2009;48(2):122–7. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Najafi I, Shakeri R, Islami F, Malekzadeh F, Salahi R, Yapan-Gharavi M, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease and its associated risk factors: the first report from Iran using both microalbuminuria and urine sediment. Archives of Iranian Medicine. 2012;15(2):70–5. doi: 012152/AIM.003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Safarinejad MR. The epidemiology of adult chronic kidney disease in a population-based study in Iran: prevalence and associated risk factors. Journal of nephrology. 2009;22(1):99–108. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gambaro G, Yabarek T, Graziani MS, Gemelli A, Abaterusso C, Frigo AC, et al. Prevalence of CKD in northeastern Italy: results of the INCIPE study and comparison with NHANES. Clinical Journal of The American Society of Nephrology: CJASN. 2010;5(11):1946–53. 10.2215/CJN.02400310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pani A, Bragg-Gresham J, Masala M, Piras D, Atzeni A, Pilia MG, et al. Prevalence of CKD and Its Relationship to eGFR-Related Genetic Loci and Clinical Risk Factors in the SardiNIA Study Cohort. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2014;25(7):1533–44. 10.1681/ASN.2013060591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Imai E, Horio M, Watanabe T, Iseki K, Yamagata K, Hara S, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the Japanese general population. Clinical and experimental nephrology. 2009;13(6):621–30. 10.1007/s10157-009-0199-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nomura I, Kato J, Kitamura K. Association between body mass index and chronic kidney disease: a population-based, cross-sectional study of a Japanese community. Vascular Health & Risk Management. 2009;5(1):315–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ohno Y, Ishimura E, Naganuma T, Kondo K, Fukushima W, Mui K, et al. Prevalence of and factors associated with chronic kidney disease in Japanese subjects, who have no known chronic disease, undergoing an annual health checkup. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2012;27:ii395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sharma SK, Dhakal S, Thapa L, Ghimire A, Tamrakar R, Chaudhary S, et al. Community-based screening for chronic kidney disease, hypertension and diabetes in dharan. Journal of the Nepal Medical Association. 2013;52(5):205–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.van Blijderveen JC, Straus SM, Zietse R, Stricker BH, Sturkenboom MC, Verhamme KM. A population-based study on the prevalence and incidence of chronic kidney disease in the Netherlands. International Urology & Nephrology. 2014;46(3):583–92. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Seck SM, Doupa D, Gueye L, Ba I. Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology in Northern Senegal: a Cross-sectional Study. Iranian journal of Kidney Diseases. 2014;8(4):286–91. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nongpiur ME, Wong TY, Sabanayagam C, Lim S-C, Tai ES, Aung T. Chronic kidney disease and intraocular pressure: the Singapore Malay Eye Study. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(3):477–83. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.07.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sabanayagam C, Lim SC, Wong TY, Lee J, Shankar A, Tai ES. Ethnic disparities in prevalence and impact of risk factors of chronic kidney disease. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2010;25(8):2564–70. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kang H-T, Lee J, Linton JA, Park B-J, Lee Y-J. Trends in the prevalence of chronic kidney disease in Korean adults: the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey from 1998 to 2009. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2013;28(4):927–36. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kim S, Lim CS, Han DC, Kim GS, Chin HJ, Kim S-J, et al. The prevalence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and the associated factors to CKD in urban Korea: a population-based cross-sectional epidemiologic study. Journal of Korean medical science. 2009;24 Suppl:S11–21. 10.3346/jkms.2009.24.S1.S11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ponte B, Pruijm M, Marques-Vidal P, Martin P-Y, Burnier M, Paccaud F, et al. Determinants and burden of chronic kidney disease in the population-based CoLaus study: a cross-sectional analysis. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2013;28(9):2329–39. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tomonaga Y, Risch L, Szucs TD, Ambuehl PM. The prevalence of chronic kidney disease in a primary care setting: a swiss cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE [Electronic Resource]. 2013;8(7):e67848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wen CP, Cheng TYD, Tsai MK, Chang YC, Chan HT, Tsai SP, et al. All-cause mortality attributable to chronic kidney disease: a prospective cohort study based on 462 293 adults in Taiwan. Lancet. 2008;371(9631):2173–82. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60952-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ong-Ajyooth L, Vareesangthip K, Khonputsa P, Aekplakorn W. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in Thai adults: a national health survey. BMC nephrology. 2009;10:35 10.1186/1471-2369-10-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chen W, Liu Q, Wang H, Chen W, Johnson RJ, Dong X, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of chronic kidney disease: a population study in the Tibetan population. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2011;26(5):1592–9. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Suleymanlar G, Utas C, Arinsoy T, Ates K, Altun B, Altiparmak MR, et al. A population-based survey of Chronic REnal Disease In Turkey—the CREDIT study. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2011;26(6):1862–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bruce MA, Beech BM, Crook ED, Sims M, Griffith DM, Simpson SL, et al. Sex, weight status, and chronic kidney disease among African Americans: the Jackson Heart Study. Journal of Investigative Medicine. 2013;61(4):701–7. 10.231/JIM.0b013e3182880bf5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hooi LS, Ong LM, Ahmad G, Bavanandan S, Ahmad NA, Naidu BM, et al. A population-based study measuring the prevalence of chronic kidney disease among adults in West Malaysia. Kidney International. 2013;84(5):1034–40. 10.1038/ki.2013.220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Gao S, Manns BJ, Culleton BF, Tonelli M, Quan H, Crowshoe L, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease and survival among aboriginal people. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2007;18(11):2953–9. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Van Pottelbergh G, Bartholomeeusen S, Buntinx F, Degryse J. The prevalence of chronic kidney disease in a Flemish primary care morbidity register. Age & Ageing. 2012;41(2):231–3. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fleet JL, Dixon SN, Shariff SZ, Quinn RR, Nash DM, Harel Z, et al. Detecting chronic kidney disease in population-based administrative databases using an algorithm of hospital encounter and physician claim codes. BMC nephrology. 2013;14:81 10.1186/1471-2369-14-81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hemmelgarn BR, Zhang J, Manns BJ, Tonelli M, Larsen E, Ghali WA, et al. Progression of kidney dysfunction in the community-dwelling elderly. Kidney International. 2006;69(12):2155–61. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Carlos ZS, Hans MO, Maritza FO. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in subjects consulting in urban primary care clinics Prevalencia de enfermedad renal cronica en centros urbanos de atencion primaria. Revista Medica de Chile. 2011;139(9):1176–84. doi: /S0034-98872011000900010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Juutilainen A, Kastarinen H, Antikainen R, Peltonen M, Salomaa V, Tuomilehto J, et al. Trends in estimated kidney function: the FINRISK surveys. European Journal of Epidemiology. 2012;27(4):305–13. 10.1007/s10654-012-9652-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Stengel B, Metzger M, Froissart M, Rainfray M, Berr C, Tzourio C, et al. Epidemiology and prognostic significance of chronic kidney disease in the elderly—the Three-City prospective cohort study. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2011;26(10):3286–95. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Anupama YJ, Uma G. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease among adults in a rural community in South India: Results from the kidney disease screening (KIDS) project. Indian Journal of Nephrology. 2014;24(4):214–21. 10.4103/0971-4065.132990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Gallieni M, Ene-Iordache B, Aiello A, Tucci B, Sala V, Brahmochary Mandal SK, et al. Hypertension and kidney function in an adult population of West Bengal, India: role of body weight, waist circumference, proteinuria and rural area living. Nephrology. 2013;18(12):798–807. 10.1111/nep.12142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Singh NP, Ingle GK, Saini VK, Jami A, Beniwal P, Lal M, et al. Prevalence of low glomerular filtration rate, proteinuria and associated risk factors in North India using Cockcroft-Gault and Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation: an observational, cross-sectional study. BMC nephrology. 2009;10:4 10.1186/1471-2369-10-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Prodjosudjadi W, Suhardjono, Suwitra K, Pranawa, Widiana IGR, Loekman JS, et al. Detection and prevention of chronic kidney disease in Indonesia: initial community screening. Nephrology. 2009;14(7):669–74. 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2009.01137.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Barahimi H, Najafi I, Esmaeilian R, Rajaee F, Amini M, Ganji MR. Distribution of albuminuria and low GFR, Shahreza, Iran. Iranian Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2011;5:26–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hosseinpanah F, Kasraei F, Nassiri AA, Azizi F. High prevalence of chronic kidney disease in Iran: a large population-based study. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:44 10.1186/1471-2458-9-44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Khajehdehi P, Malekmakan L, Pakfetrat M, Roozbeh J, Sayadi M. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease and its contributing risk factors in southern iran: A cross-sectional adult population-based study. Iranian Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2014;8(2):109–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Browne GM, Eustace JA, Fitzgerald AP, Lutomski JE, Perry IJ. Prevalence of diminished kidney function in a representative sample of middle and older age adults in the Irish population. BMC nephrology. 2012;13:144 10.1186/1471-2369-13-144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Glynn LG, Anderson J, Reddan D, Murphy AW. Chronic kidney disease in general practice: prevalence, diagnosis, and standards of care. Irish Medical Journal. 2009;102(9):285–8. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Anesi A, Casati M, Farina M, Tornesello AL, Baroni D, Pittalis S. Changing from the MDRD to the CKD-EPI equation: Impact on the reclassification of chronic kidney disease stages. [Italian] Passaggio dalla formula MDRD alla CKD-EPI: impatto sulla riclassificazione in stadi della malattia renale cronica. Rivista Italiana della Medicina di Laboratorio. 2012;8(1):45–53. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Giavarina D, Cruz DN, Soffiati G, Ronco C. Comparison of estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) using the MDRD and CKD-EPI equations for CKD screening in a large population. Clinical Nephrology. 2010;74(5):358–63. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Minutolo R, De Nicola L, Mazzaglia G, Postorino M, Cricelli C, Mantovani LG, et al. Detection and awareness of moderate to advanced CKD by primary care practitioners: a cross-sectional study from Italy. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2008;52(3):444–53. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Iseki K, Horio M, Imai E, Matsuo S, Yamagata K. Geographic difference in the prevalence of chronic kidney disease among Japanese screened subjects: Ibaraki versus Okinawa. Clinical & Experimental Nephrology. 2009;13(1):44–9. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Nagata M, Ninomiya T, Doi Y, Yonemoto K, Kubo M, Hata J, et al. Trends in the prevalence of chronic kidney disease and its risk factors in a general Japanese population: the Hisayama Study.[Erratum appears in Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010 Dec;25(12):4123–4]. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2010;25(8):2557–64. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tanaka H, Shiohira Y, Uezu Y, Higa A, Iseki K. Metabolic syndrome and chronic kidney disease in Okinawa, Japan. Kidney International. 2006;69(2):369–74. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Hallan SI, Dahl K, Oien CM, Grootendorst DC, Aasberg A, Holmen J, et al. Screening strategies for chronic kidney disease in the general population: follow-up of cross sectional health survey. BMJ. 2006;333(7577):1047 10.1136/bmj.39001.657755.BE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Jessani S, Bux R, Jafar TH. Prevalence, determinants, and management of chronic kidney disease in Karachi, Pakistan—a community based cross-sectional study. BMC nephrology. 2014;15:90 10.1186/1471-2369-15-90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Chudek J, Wieczorowska-Tobis K, Zejda J, Broczek K, Skalska A, Zdrojewski T, et al. The prevalence of chronic kidney disease and its relation to socioeconomic conditions in an elderly Polish population: results from the national population-based study PolSenior. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2014;29(5):1073–82. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Rutkowski B, Krol E. Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease in central and eastern europe. Blood Purification. 2008;26(4):381–5. 10.1159/000137275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Vinhas J, Gardete-Correia L, Boavida JM, Raposo JF, Mesquita A, Fona MC, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease and associated risk factors, and risk of end-stage renal disease: Data from the PREVADIAB study. Nephron—Clinical Practice. 2011;119(1):c35–c40. 10.1159/000324218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Covic A, Schiller A, Constantinescu O, Bredetean V, Mihaescu A, Olariu N, et al. [Stage 3–5 chronic kidney disease—what is the real prevalence in Romania?]. Revista Medico-Chirurgicala a Societatii de Medici Si Naturalisti Din Iasi. 2008;112(4):922–31. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Cepoi V, Onofriescu M, Segall L, Covic A. The prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the general population in Romania: a study on 60,000 persons. International Urology & Nephrology. 2012;44(1):213–20. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Matsha TE, Yako YY, Rensburg MA, Hassan MS, Kengne AP, Erasmus RT. Chronic kidney diseases in mixed ancestry south African populations: prevalence, determinants and concordance between kidney function estimators. BMC nephrology. 2013;14:75 10.1186/1471-2369-14-75 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Shin S-Y, Kwon M-J, Park H, Woo H-Y. Comparison of chronic kidney disease prevalence examined by the chronic kidney disease epidemiology collaboration equation with that by the modification of diet in renal disease equation in korean adult population. Journal of Clinical Laboratory Analysis. 2014;28(4):320–7. 10.1002/jcla.21688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Cea-Calvo L, Redon J, Marti-Canales JC, Lozano JV, Llisterri JL, Fernandez-Perez C, et al. [Prevalence of low glomerular filtration rate in the elderly population of Spain. The PREV-ICTUS study]. Medicina clinica. 2007;129(18):681–7. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.de Francisco ALM, De la Cruz JJ, Cases A, de la Figuera M, Egocheaga MI, Gorriz JI, et al. [Prevalence of kidney insufficiency in primary care population in Spain: EROCAP study]. Nefrologia. 2007;27(3):300–12. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Elorza-Ricart JM, Tovillas-Moran FJ, Oliveras-Puig A, Galceran JM, Fina F, Dalfo-Baque A. A comparative, cross-sectional study of the CKD-EPI and MDRD-4 equations from the Primary Care computerized clinical history of Barcelona. [Spanish] Estudio transversal comparativo de las formulas CKD-EPI y MDRD-4 a partir de la historia clinica informatizada de Atencion Primaria de Barcelona. Hipertension y Riesgo Vascular. 2012;29(4):118–29. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lou Arnal LM, Campos Gutierrez B, Boned Juliani B, Turon Calzada JM, Gimeno Orna JA. [Estimation of glomerular filtration rate in primary care: prevalence of chronic kidney disease and impact on referral to nephrology]. Nefrologia. 2008;28(3):329–32. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Otero A, de Francisco A, Gayoso P, Garcia F, Group ES. Prevalence of chronic renal disease in Spain: results of the EPIRCE study. Nefrologia. 2010;30(1):78–86. 10.3265/Nefrologia.pre2009.Dic.5732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Pena Porta JM, Blasco Oliete M, de Vera Floristan CV. [Occult renal disease and drug prescription in primary care]. Atencion Primaria. 2009;41(11):600–6. 10.1016/j.aprim.2008.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Robles NR, Felix FJ, Fernandez-Berges D, Perez-Castan JF, Zaro MJ, Lozano L, et al. Cross-sectional survey of the prevalence of reduced estimated glomerular filtration rate, albuminuria and cardiovascular risk in a native Spanish population. Journal of nephrology. 2013;26(4):675–82. 10.5301/jn.5000221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Nitsch D, Felber Dietrich D, von Eckardstein A, Gaspoz J-M, Downs SH, Leuenberger P, et al. Prevalence of renal impairment and its association with cardiovascular risk factors in a general population: results of the Swiss SAPALDIA study. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2006;21(4):935–44. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hsu C-C, Hwang S-J, Wen C-P, Chang H-Y, Chen T, Shiu R-S, et al. High prevalence and low awareness of CKD in Taiwan: a study on the relationship between serum creatinine and awareness from a nationally representative survey. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2006;48(5):727–38. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Perkovic V, Cass A, Patel AA, Suriyawongpaisal P, Barzi F, Chadban S, et al. High prevalence of chronic kidney disease in Thailand. Kidney International. 2008;73(4):473–9. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Jose MD, Otahal P, Kirkland G, Blizzard L. Chronic kidney disease in Tasmania. Nephrology. 2009;14(8):743–9. 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2009.01198.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Sahin I, Yildirim B, Cetin I, Etikan I, Ozturk B, Ozyurt H, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the Black Sea Region, Turkey, and investigation of the related factors with chronic kidney disease. Renal failure. 2009;31(10):920–7. 10.3109/08860220903219265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Denburg MR, Haynes K, Shults J, Lewis JD, Leonard MB. Validation of The Health Improvement Network (THIN) database for epidemiologic studies of chronic kidney disease. Pharmacoepidemiology & Drug Safety. 2011;20(11):1138–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Gifford FJ, Methven S, Boag DE, Spalding EM, Macgregor MS. Chronic kidney disease prevalence and secular trends in a UK population: the impact of MDRD and CKD-EPI formulae. Qjm. 2011;104(12):1045–53. 10.1093/qjmed/hcr122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Stevens PE, O'Donoghue DJ, de Lusignan S, Van Vlymen J, Klebe B, Middleton R, et al. Chronic kidney disease management in the United Kingdom: NEOERICA project results. Kidney International. 2007;72(1):92–9. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Crews DC, Charles RF, Evans MK, Zonderman AB, Powe NR. Poverty, race, and CKD in a racially and socioeconomically diverse urban population. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2010;55(6):992–1000. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.12.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Peralta CA, Lin F, Shlipak MG, Siscovick D, Lewis C, Jacobs DR Jr., et al. Race differences in prevalence of chronic kidney disease among young adults using creatinine-based glomerular filtration rate-estimating equations. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 2010;25(12):3934–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Ryan TP, Sloand JA, Winters PC, Corsetti JP, Fisher SG. Chronic kidney disease prevalence and rate of diagnosis. American Journal of Medicine. 2007;120(11):981–6. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Tanner RM, Gutierrez OM, Judd S, McClellan W, Bowling CB, Bradbury BD, et al. Geographic variation in CKD prevalence and ESRD incidence in the United States: results from the reasons for geographic and racial differences in stroke (REGARDS) study. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2013;61(3):395–403. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.10.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.IDF IDF. IDF Diabetes Atlas. 6th ed2013.

- 125.Eriksen BO, Ingebretsen OC. The progression of chronic kidney disease: a 10-year population-based study of the effects of gender and age. Kidney Int. 2006;69(2):375–82. Epub 2006/01/13. 10.1038/sj.ki.5000058 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Carrero JJ. Gender differences in chronic kidney disease: underpinnings and therapeutic implications. Kidney & blood pressure research. 2010;33(5):383–92. 10.1159/000320389 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Neugarten J, Acharya A, Silbiger SR. Effect of gender on the progression of nondiabetic renal disease: a meta-analysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11(2):319–29. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Global Burden of Disease Study C. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015;386(9995):743–800. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60692-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Boutayeb A. The double burden of communicable and non-communicable diseases in developing countries. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2006;100(3):191–9. 10.1016/j.trstmh.2005.07.021 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Coresh J, Astor BC, McQuillan G, Kusek J, Greene T, Van Lente F, et al. Calibration and random variation of the serum creatinine assay as critical elements of using equations to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39(5):920–9. Epub 2002/04/30. 10.1053/ajkd.2002.32765 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Perrone RD, Madias NE, Levey AS. Serum creatinine as an index of renal function: New insights into old concepts. Clinical chemistry. 1992;38(10):1933–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Benghanem Gharbi M, Elseviers M, Zamd M, Belghiti Alaoui A, Benahadi N, Trabelssi el H, et al. Chronic kidney disease, hypertension, diabetes, and obesity in the adult population of Morocco: how to avoid "over"- and "under"-diagnosis of CKD. Kidney Int. 2016;89(6):1363–71. 10.1016/j.kint.2016.02.019 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.KDOQI KDOQI. Chronic Kidney Disease: Evaluation, Classification, and Stratification2012. Available: http://www.kidney.org/professionals/kdoqi/guidelines_commentaries.cfm.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

S1 Appendix. Study Table—Summary descriptions of included studies (n = 100) and the populations (n = 112) within those studies.

(DOCX)

S2 Appendix. PRISMA Checklist—Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses checklist.

(DOC)

Data Availability Statement

All data are from Dryad (datadryad.org); the DOI number is doi:10.5061/dryad.3s7rd.