The Masses (original) (raw)

Sections

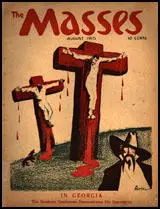

The Masses was founded in New York in 1911 by Piet Vlag. Another important financial backer was Amos Pinchot, a wealthy lawyer who supported a wide variety of progressive causes. Early members of the team included Art Young, Louis Untermeyer and John Sloan.

Organised like a co-operative, artists and writers who contributed to the journal shared in its management. According to Barbara Gelb: "After about a year and a half the Masses floundered and its tiny staff of contributors, which included the artist, John Sloan, the cartoonist, Art Young, and the poet, Louis Untermeyer, held an emergency session to rescue it. It was Young's idea to ask Max Eastman, a twenty-nine-year-old Columbia professor who had recently been dismissed for his radical views, to take over the editorship of the Masses." In 1912 Max Eastman, a Marxist, agreed to become editor of the journal.

In his first editorial, Eastman argued: "This magazine is owned and published cooperatively by its editors. It has no no dividends to pay, and nobody is trying to make money out of it. A revolutionary and not a reform magazine: a magazine with a sense of humour and no respect for the respectable: frank, arrogant, impertinent, searching for true causes: a magazine directed against rigidity and dogma wherever it is found: printing what is too naked or true for a money-making press: a magazine whose final policy is to do as it pleases and conciliate nobody, not even its readers."

Art Young later recalled: "I think we have the true religion. If only the crusade would take on more converts. But faith, like the faith they talk about in the churches, is ours and the goal is not unlike theirs, in that we want the same objectives but want it here on earth and not in the sky when we die."

Floyd Dell was appointed as Eastman's assistant: "Max Eastman was a tall, handsome, poetic, lazy-looking fellow... I was paid twenty-five dollars a week for helping Max Eastman get out the magazine.... At the monthly editorial meetings, where the literary editors were usually ranged on one side of all questions and the artists on the other. The squabbles between literary and art editors were usually over the question of intelligibility and propaganda versus artistic freedom; some of the artists held a smouldering grudge against the literary editors, and believed that Max Eastman and I were infringing the true freedom of art by putting jokes or titles under their pictures. John Sloan and Art Young were the only ones of the artists who were verbally quite articulate; but fat, genial Art Young sided with the literary editors usually; and John Sloan, a very vigorous and combative personality, spoke up strongly for the artists."

Over the next few years The Masses published articles and poems written by people such as John Reed, Sherwood Anderson, Crystal Eastman, Hubert Harrison, Inez Milholland, Mary Heaton Vorse, Louis Untermeyer, Randolf Bourne, Dorothy Day, Arturo Giovannitti, Michael Gold, Helen Keller, William English Walling, Anna Strunsky, Carl Sandburg, Upton Sinclair, Amy Lowell, Mabel Dodge, Floyd Dell and Louise Bryant.

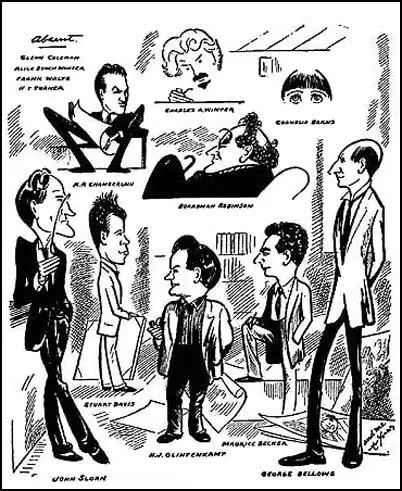

The Masses also published the work of important artists including John Sloan, Robert Henri, Alice Beach Winter, Mary Ellen Sigsbee, Cornelia Barns, Reginald Marsh, Rockwell Kent, Art Young, Boardman Robinson, Robert Minor, Lydia Gibson, K. R. Chamberlain, Stuart Davis, Hugo Gellert, George Bellows and Maurice Becker.

Albert Parry has argued in his book, Garrets and Pretenders: A History of Bohemianism in America (1933): "But then, was the magazine really for the masses? It was not. It was by the radical petit bourgeois for the liberal petit bourgeois. Yet, though the working classes almost never read the Masses, the magazine did, in the long run, help the working classes."

In 1913 Art Young and Max Eastman were charged with criminal libel after the publication of a cartoon, Poisoned at the Source. Floyd Dell later explained what happened: "The Masses decided to look into the case (a strike in West Virginia). It decided that if this thing were true, it ought to be stated without delicacy. The result was a paragraph warmly charging the Associated Press with having suppressed and colored the news of the strike in favour of the employers. Accompanying the paragraph was a cartoon presenting the same charge in a graphic form. Upon the basis of this cartoon and paragraph, William Rand, an attorney for the Associated Press, brought John Doe proceedings against the Masses." After the case was dismissed in the Municipal Court of New York City, Rand successfully approached the District Attorney and both men were arrested. Associated Press eventually dropped the case. However, after a year, the company decided to drop the law suit.

William L. O'Neill, the author of Echoes of Revolt: The Masses 1911-1917 (1966) has pointed out: "Art Young had that singular contempt for the pretensions of the press which only long and intimate associations produces. As a professional cartoonist he knew whereof he drew, and the scorn he lavished on the Associated Press was only part, as this drawing indicated, of the utter distaste he felt for the brothel economics of the industry as a whole."

Max Eastman believed that the First World War had been caused by the imperialist competitive system. Eastman and journalists such as John Reed who reported the conflict for The Masses, argued that the USA should remain neutral. Most of those involved with the journal agreed with this view but there was a small minority, including William Walling and Upton Sinclair, who wanted the USA to join the Allies against the Central Powers. When Sinclair failed to convince his fellow members he resigned from the Socialist Party and ceased to contribute to The Masses .

After the USA declared war on the Central Powers in 1917, The Masses came under government pressure to change its policy. When it refused to do this, the journal lost its mailing privileges. In July, 1917, it was claimed by the authorities that articles by Floyd Dell and Max Eastman and cartoons by Art Young, Boardman Robinson and Henry J. Glintenkamp had violated the Espionage Act. Under this act it was an offence to publish material that undermined the war effort. One of the journals main writers, Randolph Bourne, commented: "I feel very much secluded from the world, very much out of touch with my times. The magazines I write for die violent deaths, and all my thoughts are unprintable."

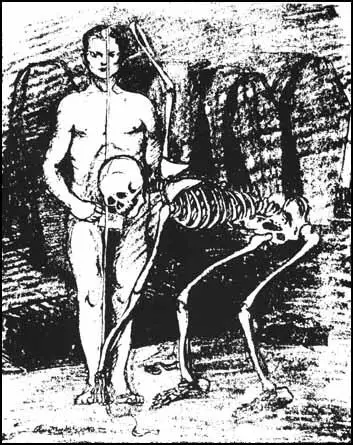

Henry J. Glintenkamp, Conscription (1917)

Henry J. Glintenkamp fled the country for Mexico but the others stood trial in April, 1918. Floyd Dell argued in court: "There are some laws that the individual feels he cannot obey, and he will suffer any punishment, even that of death, rather than recognize them as having authority over him. This fundamental stubbornness of the free soul, against which all the powers of the state are helpless, constitutes a conscious objection, whatever its sources may be in political or social opinion." The legal action that followed forced The Masses to cease publication. After three days of deliberation, the jury failed to agree on the guilt of Dell and his fellow defendants.

Art Young, The Cartoonists (1917)

The second trial was held in January 1919. John Reed, who had recently returned from Russia, was also arrested and charged with the original defendants. Dell wrote in his autobiography, Homecoming (1933): "While we waited, I began to ponder for myself the question which the jury had retired to decide. Were we innocent or guilty? We certainly hadn't conspired to do anything. But what had we tried to do? Defiantly tell the truth. For what purpose? To keep some truth alive in a world full of lies. And what was the good of that? I don't know. But I was glad I had taken part in that act of defiant truth-telling." This time eight of the twelve jurors voted for acquittal. As the First World War was now over, it was decided not to take them to court for a third time.

John Reed argued that Max Eastman was the most important factor in the acquittal: "The one great factor in our victory was Max Eastman's three-hour summing up. Standing there, with the attitude and attributes of intellectual eminence, young, good-looking, he was the typical champion of ideals - ideals which he made to seem the ideals of every real American.... Max boldly took up the Russian question, and made it part of our defense. The jury was held tense by his eloquence; the Judge listened with all his energy. In the courtroom there was utter silence. After it was all over the District Attorney himself congratulated Max."

Primary Sources

(1) Barbara Gelb, So Short a Time (1973)

Early in 1913 he (John Reed) began contributing pieces to the newly reorganized, barely solvent, but-to Reed-totally felicitous magazine, the Masses. It was a Socialist monthly. Housed in a red brick building on Greenwich Avenue, the magazine had been launched at the beginning of 1911 as a forum for anti-capitalist literature by an idealistic but impratical Dutchman named Piet Vlag. After about a year and a half the Masses floundered and its tiny staff of contributors, which included the artist, John Sloan, the cartoonist, Art Young, and the poet, Louis Untermeyer, held an emergency session to rescue it.

It was Young's idea to ask Max Eastman, a twenty-nine-year-old Columbia professor who had recently been dismissed for his radical views, to take over the editorship of the Masses. Eastman, whose first love was poetry, accepted somewhat reluctantly. There was to be no salary, at least not until the magazine got back on its feet, and the argument of future success and glory was not convincing.

Nevertheless, Eastman accepted. The son of two Congregational ministers from upstate New York, Eastman had been raised in an atmosphere of liberal-mindedness; having a mother who was the first woman to be ordained a Congregational minister in New York State, Eastman found himself perfectly at home in sympathy with the suffragists and other social reform movements of the day.

He regarded his acceptance of the editorship of the Masses as a gamble. As it turned out, it gave him his first influential platform. During the next few years he achieved a reputation as one of the leading American intellectuals and radicals. He was also, like so many of the radicals of that period, a romantic.

Boyishly handsome, he was married at this time to an aspiring actress named Ida Rauh, one of several wives and a clutch of mistresses who floated through his life.

By December 1912, Eastman had been able to persuade a wealthy woman, who knew nothing of Socialism, to back the Masses, and it was launched on its controversial career...

Eastman asked a recent arrival in Greenwich Village, Floyd Dell, to be his associate editor. Dell, who was the same age as Reed, came from a small town in Illinois and had worked on newspapers in Chicago. He had been a Socialist since he was fourteen, and his ambition was to write novels, though he had tried his hand at playwriting. He was tall and slender, with a broad forehead and pointed chin, and wore long sideburns.

The absence of salary increased rather than diminished the fervor and esprit de corps that ruled the small circle of Masses editors and contributors. Editorial meetings were lively and uninhibited, and seldom confined to business. Reed was often there, holding forth on his pet theory of the moment and his articles ran side by side with the contributions of Carl Sandburg, Sherwood Anderson, Bertrand Russell, Maxim Gorky, and Vachel Lindsay.

(2) Max Eastman, policy of The Masses (December, 1912)

This magazine is owned and published cooperatively by its editors. It has no no dividends to pay, and nobody is trying to make money out of it. A revolutionary and not a reform magazine: a magazine with a sense of humour and no respect for the respectable: frank, arrogant, impertinent, searching for true causes: a magazine directed against rigidity and dogma wherever it is found: printing what is too naked or true for a money-making press: a magazine whose final policy is to do as it pleases and conciliate nobody, not even its readers...

We do not enter the field of any Socialist or other magazine now published, or to be published. We shall have no further part in the factional disputes within the Socialist party; we are opposed to the dogmatic spirit which creates and sustains these disputes. Our appeal will be to the masses, both Socialist and non-Socialist, with entertainment, education, and the livelier kinds of propaganda.

(3) John Sloan, Gist of Art (1939)

The night the first copy of The Masses (under Max Eastman's editorship) came out, I sold seventy-eight copies. It was at a Suffrage parade. I went up to people, sometimes got on the running board of a car, saying, "Buy it. It will be worth ten dollars some day."

(4) Floyd Dell, Homecoming (1933)

I was taken to the office of that magazine, and there I met Max Eastman, the editor, and John Reed. Max Eastman was a tall, handsome, poetic, lazy-looking fellow; Jack Reed a large, infantile, round-faced, energetic youth. The magazine had been started by a group of Socialist artists and writers; it had run out of money, and stopped; then they had read in the papers something that Max Eastman, a professor of philosophy in Columbia University, had said; he was evidently a Socialist, and they wrote a letter and asked the professor of philosophy if he would like to edit their magazine. He quit his professorial job, raised some money, and now the magazine was going again.

Now as it happened, when the magazine had stopped, the business manager, an enterprising Dutchman named Piet Vlag, had taken its moribund remains to Chicago, and had there united it with a Socialist and Feminist magazine published in Chicago by Josephine Conger-Kaneko. I had been at a meeting where the merger was made, and I had been made an editor of The Masses; but that had all been illegal, and I didn't mention it to Max Eastman or Jack Reed. But when they asked if I had any stories, and I asked them how long, and they said about six hundred words, I said I hadn't any of that length but would write them one; and the next day I wrote a story of that length called A Perfectly Good Cat; the magazine didn't pay for anything, but it was a great honor to have the privilege of contributing to it; the story, when published, was to evoke more letters of protest from shocked contributors, including Upton Sinclair, than anything The Masses had ever published up to that time. That Smart Set story and that Masses story would seem very tame now; but readers were easily shocked in those days...

I was paid twenty-five dollars a week for helping Max Eastman get out the magazine. My job on The Masses was to read manuscripts, bring the best of them to editorial meetings to be voted on, send back what we couldn't use, read proof, and "make up" the magazine - all duties with which I was familiar; and also to help plan political cartoons and persuade the artists to draw them. I could submit my stories and poems anonymously to the editorial meetings, hear them discussed, and print them if they were accepted.

At the monthly editorial meetings, where the literary editors were usually ranged on one side of all questions and the artists on the other. The squabbles between literary and art editors were usually over the question of intelligibility and propaganda versus artistic freedom; some of the artists held a smouldering grudge against the literary editors, and believed that Max Eastman and I were infringing the true freedom of art by putting jokes or titles under their pictures. John Sloan and Art Young were the only ones of the artists who were verbally quite articulate; but fat, genial Art Young sided with the literary editors usually; and John Sloan, a very vigorous and combative personality, spoke up strongly for the artists.

Nobody gained a penny out of the things published in the magazine; it was an honour to get into its pages, an honour conferred by vote at the meetings. Max Eastman and I did get salaries for editorial work; but that was regarded as dirty work, which ought to be paid for. We were actually a little republic in which, as artists, we worked for the approval of our fellows, not for money.

(5) At the beginning of the First World War, the editor of The Masses, Max Eastman, wrote an article entitled The War of Lies (October, 1914)

Food is as important to armies as ammunition - but more important than either is an unfailing supply of lies. You simply cannot murder your enemy in the most efficient manner if you know he is in every essential the same kind of a man as yourself.

Governments have tried to lay up a sufficient stock of lies before the war start, but always in vain. The progress of popular intelligence scraps such lies almost as fast as they are manufactured. The only safe way is to produce an entirely new stock in the panic days immediately before the war, when the people have no time or inclination to think, and are cut off from all communication with the other side. After the war starts, of course, the industry may be indefinitely continued.

This should be bourne in mind in reading tales of the barbarous atrocity of soldiers, now on one side and now on the other.

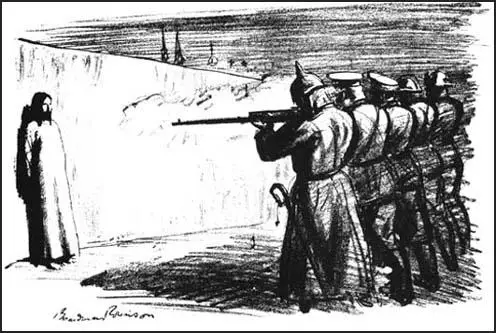

Boardman Robinson, The Deserter, The Masses (July, 1916)

(6) John Reed, The Masses (September, 1914)

No recent words have seemed to me so ludicrously condescending as the Kaiser's speech to his people when he said that in this supreme crisis he freely forgave all those who had ever opposed him. I am ashamed that in this day in a civilized country any one can speak such archaic nonsense as that speech contained.

More nauseating than the crack-brained bombast of the Kaiser is the editorial chorus in America which pretends to believe - would have us believe - that the White and Spotless Knight of Modern Democracy is marching against the Unspeakably Vile Monster of Medieval Militarism.

What has democracy to do in alliance with Nicholas, the Tsar? It is Liberalism which is marching from the Petersburg of Father Gapon, from the Odessa of Progroms? Are our editors naive enough to believe this?

We, who are Socialists, must hope - we may even expect - that out of this horror of bloodshed and dire destruction will come far-reaching social changes - and a long step forward towards our goal of peace among men. But we must not be duped by this editorial buncombe about Liberalism going forth to Holy War against Tyranny. This is not our war.

(7) Max Eastman, Love and Revolution (1964)

A regular contributor to The Masses was Boardman Robinson, then and perhaps permanently regarded as one of America's greatest artists. "His masterly drawings had the breathlike delicacy as well as the power of the old Masters," in the judgment of a fellow artist, Reginald Marsh. Surprisingly as it may seem, he actually introduced into America the idea, as old as Daumier, that cartoons should have the values of art as well as of meaning.

He was big, burly, bluff, sea-captain sort of character, with dancing blue eyes under bushy red brows, a red beard, and a boisterous way of "blowing in" as though out of a storm, instead of merely entering, a place of habitation. Everybody called him Mike, and I guess it must have been in memory of Michelangelo, whose fury and rapture his powerful and meaningful drawings did recall.

When Mike blew in with a picture of a white-clad, saintly Jesus standing against a stone wall facing the rifles of a brutish firing squad - "The Deserter"- I felt that number (The Masses, July, 1916) deserved a place in the history of art.

(8) John Reed, The Masses (March 1915)

The French Army has not been fighting well. But it has been fighting, and the slaughter is appalling. There remains no effective reserve in France; and the available youth of the nation down to seventeen years of age is under arms. For my part, all other considerations aside, I should not care to live half-frozen in a trench, up to my middle in water, for three or four months, because someone in authority said I ought to shoot Germans. But if I were a Frenchman I should do it, because I would have been accustomed to the idea by my compulsory military service.

I could fill pages of horrors that civilized Europe is inflicted upon itself. I could describe to you the quiet, dark, saddened streets of Paris, where every ten feet you are confronted with some miserable wreck of a human being, or a madman who lost his reason in the trenches being led around by his wife.

I could tell you of the big hospital in Berlin full of German soldiers who went crazy from merely hearing the cries of the thirty thousand Russians drowning in the swamps of East Prussia after the battle of Tannenburg. Or of the numbness and incalculable demoralization among men in the trenches. Or of holes torn in bodies with jagged pieces of melanite shells, of sounds that make people deaf, of gases that destroy eyesight, of wounded men dying day by day and hour by hour within forty yards of twenty thousand human beings, who won't stop killing each other long enough to gather them up.

(9) Floyd Dell, Homecoming (1933)

The Masses was presently indicted for criminal libel at the complaint of the Associated Press, for saying that it suppressed the news in the Colorado strike; the case was afterwards dropped. The magazine, among other news, told of Frank Tannenbaum's being arrested for leading homeless men into a New York church to sleep. Jack Reed was sending vigorous, realistically beautiful short stories to us from Mexico. I was thrilled when John Sloan drew a picture of a girl being beaten by the matron of a reformatory, to illustrate my story, The Beating. Among The Masses' literary editors, Louis Untermeyer, who had written about poetry for the Friday Review, was a friend already; we were interested in the same things, and lunched together frequently to discuss the universe. At the monthly editorial meetings, where the literary editors were usually ranged on one side of all questions and the artists on the other, I saw Horatio Winslow, Mary Heaton Vorse, William English Walling, Howard Brubaker; and Art Young, John Sloan, Charles A. and Alice Beach Winter, H. J. Turner, Maurice Becker, George Bellows, Cornelia Barns, Stuart Davis, Glenn O. Coleman, K. R. Chamberlain. The squabbles between literary and art editors were usually over the question of intelligibility and propaganda versus artistic freedom; some of the artists held a smouldering grudge against the literary editors, and believed that Max Eastman and I were infringing the true freedom of art by putting jokes or titles under their pictures. John Sloan and Art Young were the only ones of the artists who were verbally quite articulate; but fat, genial Art Young sided with the literary editors usually; and John Sloan, a very vigorous and combative personality, who was himself hotly propagandist and felt no desire to be unintelligible, spoke up strongly for the artists who lacked parliamentary ability, and defended the extreme artistic-freedom point of view in their behalf. I, who had tried to get up a rebellion against Max Eastman when I first came on the magazine, over some high-handed proceeding of his, had soon become his faithful lieutenant in a practical dictatorship. Once the artists rebelled and took the magazine away from us; but, as they did nothing toward getting out the next issue, Max and I got some proxies from absentee stockholders and took the magazine back. It stood for fun, truth, beauty, realism, freedom, peace, feminism, revolution.

I hardly realized at the time the nature of the problem The Masses group was trying to solve-co-operation between artists, men of genius, egotists inevitably and rightfully, proud, sensitive, hurt by the world, each of them the head and center of some group, large or small, of admirers or devotees; now it seems to me an extraordinary triumph that so much good-humored and effective co-operation was possible between them. Nobody gained a penny out of the things published in the magazine; it was an honor to get into its pages, an honor conferred by vote at the meetings. Max Eastman and I did get salaries for editorial work; but that was regarded as dirty work, which ought to be paid for. We were actually a little republic in which, as artists, we worked for the approval of our fellows, not for money. I think that the practical success of the experiment - it never made money, always had to be subsidized, and the success to which I refer is its enthusiastic continuance under these conditions - was due chiefly to Max Eastman's tact and eloquence; he could talk anybody into doing anything.

(10) Upton Sinclair, letter of resignation from the Socialist Party (September, 1917)

I have lived in Germany and know its language and literature, and the spirit and ideals of its rulers. Having given many years to a study of American capitalism. I am not blind to the defects of my own country; but, in spite of these defects, I assert that the difference between the ruling class of Germany and that of America is the difference between the seventeenth century and the twentieth.

No question can be settled by force, my pacifist friends all say. And this in a country in which a civil war was fought and the question of slavery and secession settled! I can speak with especial certainty of this question, because all my ancestors were Southerners and fought on the rebel side; I myself am living testimony to the fact that force can and does settle questions - when it is used with intelligence.

In the same way I say if Germany be allowed to win this war - then we in America shall have to drop every other activity and devote the next twenty or thirty years to preparing for a last-ditch defence of the democratic principle.

(11) The Masses (September, 1917)

The Post Office was represented by Assistant District Attorney Barnes. He explained that the Department construed the Espionage Act as giving it power to exclude from the mails anything which might interfere with the successful conduct of the war.

Four cartoons and four pieces of text in the August issue were specified as violations of the law. The cartoons were Boardman Robinson's Making the World Safe for Democracy, H. J. Glintenkamp's Liberty Bell and the conscription cartoons, and one by Art Young on Congress and Big Business. The conscription cartoon was considered by the Department "the worst thing in the magazine". The text objected to was A Question, an editorial by Max Eastman; A Tribute, a poem by Josephine Bell; a paragraph in an article on Conscientious Objectors; and an editorial, Friends of American Freedom.

(12) Floyd Dell, Homecoming (1933)

The Masses harassed by the post-office authorities, was suppressed in October, 1917, by the Government, and its editors were indicted, myself among them, under the so-called Espionage Act, which was being used not against German spies but against American Socialists, Pacifists, and anti-war radicals. Sentences of twenty years were being served out to all who dared say this was not a war to end war, or that the Allied loans would never be paid. But the courts would probably not get around to us until next year; and we immediately made plans to start another magazine, The Liberator, and tell more truth; we would stand on the pre-war Wilsonian program, and call for a negotiated peace.

(13) In his autobiography Floyd Dell explained his thoughts on being charged with breaking the Espionage Act.

While we waited, I began to ponder for myself the question which the jury had retired to decide. Were we innocent or guilty? We certainly hadn't 'conspired' to do anything. But what had we tried to do? Defiantly tell the truth. For what purpose? To keep some truth alive in a world full of lies. And what was the good of that? I don't know. But I was glad I had taken part in that act of defiant truth-telling.

Rumours began to perculate. "Six to six." Next morning the debate in the jury-room grew fiercer, noisier. At noon the jury came in, hot, weary, angry, limp, and exhausted. They had fought the case amongst themselves for eleven vehement hours. And they could not agree upon a verdict.

But the judge refused to discharge them; and they went back, after further instructions, with grim determination on their faces.

At eleven o'clock the jurors reported continued disagreement, but were sent back. The next noon, hopelessly deadlocked, the jury was discharged, with all our thanks. And so we were free.

(14) Barbara Gelb, So Short a Time (1973)

Art Young was in Eastman's view, the hero of the trial. Young, at fifty-two, was a nationally famous political cartoonist, who had been the Washington correspondent for the Metropolitan until 1917, and a contributor to Life, The Saturday Evening Post, and Collier's, in addition to the Masses. A member of the Socialist Party, he was a crusader for women's suffrage, labor unions, and racial equality.

One of the prosecution's pieces of evidence was a cartoon Young had drawn, showing a capitalist, an editor, a politician, and a minister dancing a war dance, while the devil directed the orchestra; it was captioned, "Having Their Fling." The prosecutor asked him what he meant by the picture.

"Meant? What do you mean by meant? You have the picture in front of you."

"What did you intend to do when you drew this picture, Mr. Young?"

"Intend to do? I intended to draw a picture." "For what purpose?"

"Why, to make people think-to make them laugh-to express my feelings. It isn't fair to ask an artist to go into the metaphysics of his art."

"Had you intended to obstruct recruiting and enlistment by such pictures?"

"There isn't anything in there about recruiting and enlistment is there? I don't believe in war, that's all, and I said so."

After hearing the bulk of the testimony, Judge Hand dismissed the part of the indictment that accused the Masses of conspiring to cause mutiny and refusal of duty in the armed forces; the only charge for the jury to weigh was that of a "conspiracy" to obstruct the draft.

In summing up, Hillquit said, in part: "Constitutional rights are not a gift. They are a conquest by this nation, as they were a conquest by the English nation. They can never be taken away, and if taken away, and if given back after the war, they will never again have the same potent vivifying force as expressing the democratic soul of a nation. They will be a gift to be given, to be taken."

The prosecuting attorney, Earl Barnes, was "sincerely convinced" that the Masses staff should go to jail, Eastman recalled. Yet he seemed equally sincere in his reluctance to send them there, and in his summation to the jury, made numerous complimentary references to the individual talents of the defendants.

(15) John Reed, The Liberator (January, 1919)

How inevitably, how clearly in all these cases, the issue narrows down to the Class Struggle! District Attorney Barnes' opening address to the jury implied one chief crime - that of plotting the overthrow of the United States Government by revolution; in other words, the crime of being, in the words of Mr. Barnes, 'Bolsheveeka,' addicted to what he called 'Syndickalism.' An immortal definition of the Socialist conception which he made to the jury remains in my mind.

These people believe that there are three classes - the capitalists, who own all the natural resources of the country; the bourgeoisie, who have got a little land or a little property under the system; and the proletariat, which consists of all those who want to take away the property of the capitalists and the bourgeoisie.

We were described as men without a country, who wanted to break down all boundaries. The jury was asked what it thought of people who called respectable American businessmen "bourgeoisie."

In no European country could a prosecuting attorney have displayed such ignorance of Socialism, or relied so confidently upon the ignorance of a jury.

I was not present at the first Masses trial. In prospect, it did not seem to me very serious; but when I sat in that gloomy, dark-paneled court-room and the bailiff with the brown wig beat the table and cried harshly, "Stand up!" and the judge climbed to his seat, and it was announced, in the same harsh, menacing tone, "The Federal Court for the Soµthern District of New York is now open." I felt as if we were in the clutches of a relentless machinery, which would go on and grind and grind....

I think we all felt tranquil, and ready to go to prison if need be. At any rate, we were not going to dissemble what we believed. This had its effect on the jury, and on the Judge.... When Seymour Stedman boldly claimed for us, and for all Socialists, the right of idealistic prophesy, and repudiated the capitalist system with its terrible inequalities, a new but perfectly logical and consistent point of view was presented. The jury was composed of a majority of honest, rather simple men, the background of whose consciousness must have contained memories of the Declaration of Independence, the Rights of Man, Magna Charta. They could not easily, even in war time, repudiate these things; especially when all the defendants were so palpably members of the dominant race.

Two weeks later I saw in that same court the trial of some Russian boys and girls on similar charges. They did not have a chance; they were foreigners. An official of the District Attorney's office was explaining to me why the Judge had been so severe upon these Russians, while our Judge in the Masses case had been so lenient.

"You are Americans," he said. "You looked like Americans. And then, too, you had a New York Judge. You can't convict an American for sedition before a New York Judge. If you'd had Judge Clayton, for example, it would have been equivalent to being tried in the Middle West, or in any other Federal Court outside of New York. You would have been soaked."

It has been said that the disagreement of the jury in this second Masses case is a victory for free speech and for international Socialism. In a way this is true. International Socialism was argued in court, thanks to the curiosity and the fair-mindedness of Judge Manton.

Free speech was vindicated by the charge of Judge Manton, who ruled that anyone in this country could say that the war was not for democracy, that it was an imperialist war, that the Government of the United States was hypocritical - in fact, that any American had the right to criticize his government or its policies, so long as he did not intend to discourage recruiting and enlistment or cause mutiny and disobedience in the armed forces of the United States.

But the one great factor in our victory was Max Eastman's three-hour summing up. Standing there, with the attitude and attributes of intellectual eminence, young, good-looking, he was the typical champion of ideals - ideals which he made to seem the ideals of every real American.... Max boldly took up the Russian question, and made it part of our defense. The jury was held tense by his eloquence; the Judge listened with all his energy. In the courtroom there was utter silence. After it was all over the District Attorney himself congratulated Max.

(16) Floyd Dell, Homecoming (1933)

All this discussion of our various opinions on almost every conceivable political topic had extended the trial into its second week. On the ninth day, the attorneys for both sides summed up. The district attorney most surprisingly paid us all compliments in asking the jury to convict us. "These men," he said, "are men of extraordinary intelligence." And me in particular he characterized thus: "Dell, a trained journalist, a writer of exquisite English, keenly ironical, bitingly sarcastic." Thank you, Mr. Barnes! "And so, gentlemen of the jury," he concluded, "I confidently expect you to bring in a verdict of guilty against each and every one of the defendants."

The jury, being duly charged, retired late that afternoon. And we awaited the verdict. We thought a good deal about those jurors as we walked up and down the corridors, smoking and talking with our friends, through the long hours that passed so slowly thereafter. A defendant cannot sit for days in the same room with twelve jurymen without getting to some extent acquainted with them, and feeling that they are for or against him...

But rgat, after all, was mere guessing. How could we be sure that the man we thought most hostile might not turn out to be our best friend? - perhaps our only friend! And of those who were for us, how could we be certain that they had the courage to hold out? Some friend experienced in the ways of juries would take our arm and whisper: "Expect anything." From behind the heavy door of the jury-room came sounds of excited argument....

Art Young took me aside and asked me quietly: "Floyd, when you were a little boy did you ever read any books about the Nihilists?" "Yes," I said. "And did you think that maybe some day you might have to go to prison for something you believed?" "Yes," I said. "Then it's all right," said Art Young, "no matter what happens." And I was glad to know that Art Young was spiritually ready to go to prison.

I realized that I had never been more serene and at ease in my whole life than during the nine days of this trial. I had been curiously happy. It might be unreasonable, but it was so. And one who is being psychoanalyzed is not surprised to find his emotions unreasonable.

While we waited, I began to ponder for myself the question which the jury had retired to decide. Were we innocent or guilty? We certainly hadn't "conspired" to do anything. But what had we tried to do? Defiantly tell the truth. For what purpose? To keep some truth alive in a world full of lies. And what was the good of that? I didn't know. But I was glad I had taken part in that act of defiant truth-telling. The jury could be heard noisily arguing about us - or about something.

After dinner we returned, with a few friends, and bivouacked in the dim corridor, waiting. Late that night the judge was sent for, and we went eagerly into the court-room. The jury filed in. Had they brought in a verdict? No; they desired further instructions.

The judge then repeated a definition of "conspiracy" which no one but a lawyer would pretend to understand, and the jury went back. And already the inevitable rumors began to percolate. "Six to six."

Six to six! The struggle of contending views of life had ceased in the court-room, and been taken up by the jury. Other protagonists and antagonists, whose exact identity was unknown to us, were fighting the thing out in that little room. The debate had not ended, it had merely changed its place and personnel.... And then we remembered that our fate was involved in that debate; and we felt a warm rush of emotion, of gratitude toward these unknown defenders who had made our cause their own.

Next morning the debate in the jury-room grew fiercer, noisier. At noon the jury came in, hot, weary, angry, limp, and exhausted. They had fought the case amongst themselves for eleven vehement hours. And they could not agree upon a verdict.

But the judge refused to discharge them; and they went back, after further instructions, with grim determination on their faces.

And again we wandered about the corridors-all day; and returned in the evening to camp outside the court-room... Then, in the unlighted windows of the skyscraper opposite, we discovered a dim and ghostly reflection of the interior of the jury-room. Men were standing up and sitting down, four and five at a time. A vote? Someone raised his arm. Someone strode across the room. Someone took off his coat. I stood at our window and watched... and then went away. I had waited for twenty-nine hours. I could wonder no more. The whole thing seemed as dim and unreal as that ghostly reflection in the window. I thought about stars and flowers and ideas and my sweetheart...

At eleven o'clock the jurors reported continued disagreement, but were sent back.

The next noon, hopelessly deadlocked, the jury was discharged, with all our thanks. And so we were free.

(17) Max Eastman, Love and Revolution (1964)

There was one big difference between the Masses and the Liberator; in the latter we abandoned the pretense of being a co-operative. Crystal Eastman and I owned the Liberator, fifty-one shares of it, and we raised enough money so that we could pay solid sums for contributions.

The list of contributing editors, largely brought over from the Masses, reads as follows: Cornelia Barns, Howard Brubaker, Hugo Gellert, Arturo Giovannitti, Charles T. Hallinan, Helen Keller, Ellen La Motte, Robert Minor, John Reed, Boardman Robinson, Louis Untermeyer, Charles Wood, Art Young.

Later Claude McKay, the Negro poet, became an associate editor. At a New Year's party in 1921, we elected Michael Gold and William Gropper to the staff - two opposite poles of a magnet: Gropper as instinctively comic an artist as ever touched pen to paper, and Gold almost equally gifted with pathos and tears.

Student Activities

American Artists and the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Käthe Kollwitz: German Artist in the First World War (Answer Commentary)

Walter Tull: Britain's First Black Officer (Answer Commentary)