Lord Kitchener (original) (raw)

Sections

- Governor-General

- Battle of Omdurman

- Boer War

- Scorched Earth Policy

- Concentration Camps

- First World War

- Primary Sources

Horatio Kitchener, the third child and second son of Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Horatio Kitchener (1805–1894), was born near Ballylongford, County Kerry, Ireland, on 24th June 1850. According to Keith Neilson: "His father was an unpopular, tenant-evicting, improving landowner, a domestic martinet, and an eccentric who used newspapers instead of blankets in bed."

Kitchener's mother suffered from tuberculosis and the family moved to Switzerland in 1864. Kitchener attended an English boarding-school at Renaz. Teased about his strange Irish accent, he devoted himself to his books, and became fluent in French and German. In 1867 he moved to Cambridge to complete his secondary education. He wanted to study at the Royal Military Academy. He took the examination in January 1868, passing twenty-eighth out of fifty-six. Kitchener was not a very talented student but on 4th January, 1871, he was commissioned into the Royal Engineers. He spent the next two years at the School of Military Engineering in Chatham.

Kitchener came to the attention of Brigadier-General George Richards Graves of the War Office staff and was appointed as his aide-de-camp in 1873. The following year he was seconded to the Palestine Exploration Fund (PEF). Kitchener was a talented linguist and learnt Arabic during this period. He was also respected as a skilled negotiator with local people.

In 1878 he was seconded to the Foreign Office and given the task of mapping Cyprus. In June 1879 he was appointed military vice-consul, to Kastamonu Province in Turkey. In March 1880 he returned to Cyprus at the request of the new high commissioner, Robert Biddulph, and for the next two years continued his survey.

Kitchener secured a posting to Egypt early in 1883, at the same time as being promoted captain. In March 1884 General Charles George Gordon was under siege in Khartoum. The British public called for action but it was not until November that the Khartoum Relief Expedition under the leadership of Field Marshal Garnet Wolseley began. Kitchener was an intelligence officer on the mission and he continually pressed Wolseley to push forward more rapidly. By the time they reached the city Gordon was dead.

Keith Neilson has pointed out: "Despite the expedition's failure to save Gordon, Kitchener emerged with credit and some fame. Promoted brevet lieutenant-colonel in June 1885, he resigned his Egyptian commission and returned to England, where his fame had been spread by the press and his father. The press had a crucial role in creating the Kitchener legend. Kitchener used his new status as a social lion to make many connections which later proved useful."

Governor-General

In 1886 Kitchener was appointed as governor-general of the eastern Sudan. Most of his time was spent dealing with Osman Digna, a major slave trader and a follower of of the Muhammad Ahmad. During a skirmish in January 1888 Kitchener was shot in the jaw. He returned to England on leave, where Lord Salisbury, the prime minister, arranged for him to be adjutant-general of the Egyptian Army, a post he took up in September 1888. He was given the additional position of inspector-general of police in the autumn of 1889.

Kitchener was made commander-in-chief of the Egyptian Army on 13th April 1892. Keith Neilson has argued: "This offended many who believed he owed his appointment more to his assiduous cultivation of the powerful than to his abilities. Such a view was reinforced by his tour of country houses when on leave in England, and by the prominent persons, including the prince of Wales, who stayed with him in Egypt. Kitchener however immediately set about reforming the Egyptian army, gathering around him a cadre of eager young officers... The fact that Kitchener surrounded himself with similar groups throughout his career, and never married, led to speculations that he was a homosexual."

In 1897 Major General Kitchener decided to attempt the reconquest of the Sudan. Kitchener applied to London for a group of special service officers to participate in his largely Egyptian force. George Henderson suggested that Douglas Haig should be sent to serve under Kitchener. It was during this period that the two men became friends.

Battle of Omdurman

Kitchener's army took Abu Hamed on 7th August, 1897. Later that month they occupied Berber. He had to halt his advance until he received reinforcements. A new campaign began with the capture of Atbara on 8th April, 1898. They reached the Mahdist capital, Omdurman, four months later. The Battle of Omdurman began on 2nd September. Kitchener commanded a force of 8,000 British regulars and a mixed force of 17,000 Sudanese and Egyptian troops. Abdullah al-Taashi, the successor to Muhammad Ahmad, had around 50,000 men at his disposal.

The battle began in the early morning. The British artillery opened fire, inflicting severe casualties on the Ansar forces before they even came within range of the Maxim guns. The frontal attack ended quickly, with around 4,000 Ansar casualties. It has been claimed that none of the attackers got closer than 50m to the British trenches. Later that day Kitchener was able to take control of Omdurman.

Winston Churchill wrote: "Thus ended the Battle of Omdurman - the most signal triumph ever gained by the arms of science over barbarians. Within the space of five hours the strongest and best-armed savage army yet arrayed against a modern European Power had been destroyed and dispersed, with hardly any difficulty, comparatively small risk, and insignificant loss to the victors."

Paul Halsall has pointed out: "The Dervish Army, approximately 52,000 strong, suffered losses of 20,000 dead, 22,000 wounded, and some 5,000 taken prisoner - an unbelievable 90% casualty rate! By contrast, the Anglo-Egyptian Army, some 23,000 strong, suffered losses of 48 dead, and 382 wounded - an equally unbelievable 2% casualty rate, thus showing the superiority of modern firepower!"

Kitchener had returned home to England to a mixed welcome. As Keith Neilson explained: "As he rose Kitchener provoked continued resentment and criticism. Anti-imperialists hated his imperial victories and triumphs. Some British officers were jealous of his success, and for varied reasons there was among senior officers much suspicion of him... Despite radicals' and others' criticism of Kitchener's behaviour, particularly his desecration of the Mahdi's tomb at Omdurman and his taking of the latter's skull, the British public lionized the sirdar... and he was frequently mobbed when he appeared in public."

Boer War

Kitchener served as governor-general of Sudan from 19th January to 18th December 1899. However, on the outbreak of the Boer War he was sent to South Africa, where he was chief of staff to the commander-in-chief, Field Marshal Frederick Roberts. Kitchener was in charge of the forces at Paardeberg. Lieutenant General Thomas Kelly-Kenny, commanding the British 6th Division, wanted to lay siege and bombard the force led by Piet Cronjé into surrender. Lieutenant General Herbert Kitchener overruled Kelly-Kenny and ordered the infantry and mounted troops into a series of uncoordinated frontal assaults against the entrenched Boers. Armed with the modern weapons the Sudanese had wholly lacked, the British were shot down in large numbers. It is thought that not a single British soldier got within 200 yards of the Boer lines. During the attack 24 officers and 279 men were killed and 59 officers and 847 men wounded.

After this disaster it was decided to return to the strategy first suggested by Lieutenant General Kelly-Kenny. While Paardeberg was besieged Roberts sent Kitchener to repair the railway system in the Orange Free State. In June 1900, Kitchener was sent to Pretoria to deal with Christian De Wet. For the next two months Kitchener pursued the Boer guerrillas. As Keith Neilson points out: "To deal with the Boers' guerrilla tactics, Kitchener used two complementary methods. The first was to divide the country up into a grid by building a series of blockhouses and barbed-wire fences, and by instituting drives along these grids using columns of mounted troops. It was owing to the rugged terrain and the Boers' familiarity with the countryside that this policy was not initially successful. Kitchener's second method was resource denial, achieved by destroying Boer farms and - continuing and intensifying the process begun under Roberts - gathering the occupants, mostly women and children, into forty-six 'refugee' or ‘concentration’ camps where they could not aid the commandos."

Scorched Earth Policy

In October 1900, Emily Hobhouse formed the Relief Fund for South African Women and Children. An organisation set up: "To feed, clothe, harbour and save women and children - Boer, English and other - who were left destitute and ragged as a result of the destruction of property, the eviction of families or other incidents resulting from the military operations". Except for members of the Society of Friends, very few people were willing to contribute to this fund.

Hobhouse arrived in South Africa on 27th December, 1900. After meeting Alfred Milner, she gained permission to visit the concentration camps that had been established by the British Army. However, Lord Kitchener objected to this decision and she was now told she could only go to Bloemfontein.

Hobhouse left Cape Town on 22nd January, 1901, and arrived at Bloemfontein two days later. There were at the time eighteen hundred people in the camp. Emily discovered "that there was a scarcity of essential provision and that the accommodation was wholly inadequate." When she complained about the lack of soap she was told, "soap is an article of luxury". She nevertheless succeeded ultimately to have it listed as a necessity, together with straw and kettles in which to boil the drinking water. Over the next few weeks Emily visited several camps to the south of Bloemfontein, including Norvalspont, Aliwal North, Springfontein, Kimberley and Orange River. She was also allowed to visit Mafeking. Everywhere she directed the attention of the authorities to the inadequate sanitary accommodation and inadequate rations.

Concentration Camps

Hobhouse argued that Kitchener’s "Scorched Earth" policy included the systematic destruction of crops and slaughtering of livestock, the burning down of homesteads and farms, and the poisoning of wells and salting of fields - to prevent the Boers from resupplying from a home base. Civilians were then forcibly moved into the concentration camps. Although this tactic had been used by Spain (Ten Years' War) and the United States (Philippine-American War), it was the first time that a whole nation had been systematically targeted.

Hobhouse decided that she had to return to England in an effort to persuade the Marquess of Salisbury and his government to bring an end to the British Army's scorched earth and concentration camp policy. David Lloyd George and Charles Trevelyan took up the case in the House of Commons and accused the government of "a policy of extermination" directed against the Boer population. William St John Fremantle Brodrick, the Secretary of State for War argued that the interned Boers were "contented and comfortable" and stated that everything possible was being done to ensure satisfactory conditions in the camps.

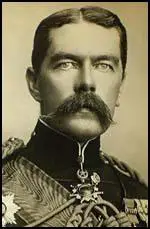

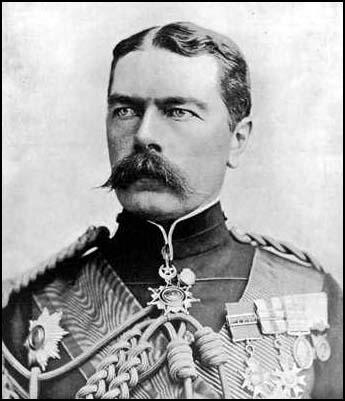

Lord Kitchener

In August, 1901, the British government established a commission headed by Millicent Fawcett to visit South Africa. While the Fawcett Commission was carrying out the investigation, the government published its own report. According to the New York Times: “The War Office has issued a four-hundred-page Blue Book of the official reports from medical and other officers on the conditions in the concentration camps in South Africa. The general drift of the report attributes the high mortality in these camps to the dirty habits of the Boers, their ignorance and prejudices, their recourse to quackery, and their suspicious avoidance of the British hospitals and doctors.”

The Fawcett Commission confirmed almost everything that Emily Hobhouse had reported. After the war a report concluded that 27,927 Boers had died of starvation, disease and exposure in the concentration camps. In all, about one in four of the Boer inmates, mostly children, died. However, the South African historian, Stephen Burridge Spies argues in Methods of Barbarism: Roberts and Kitchener and Civilians in the Boer Republics (1977) that this is an under-estimate of those who died in the camps.

After the Boer War was brought to an end by the signing of the Peace Treaty of Vereeniging, Kitchener became commander-in-chief in India (1902-09) and military governor of Egypt (1911-14). J. B. Priestley met Kitchener at this time: "I had a close view, finding him older and greyer than the familiar pictures of him. The image I retained was of a rather bloated purplish face and glaring but somehow jellied eyes."

First World War

On the outbreak of the First World War, the Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith, appointed Kitchener as Secretary of War. Kitchener, he first member of the military to hold the post, was given the task of recruiting a large army to fight Germany. A.J.P. Taylor has pointed out: "He startled his colleagues at the first cabinet meeting which he attended by announcing that the war would last three years, not three months, and that Great Britain would have to put an army of millions into the field. Regarding the Territorial Army with undeserved contempt, he proposed to raise a New Army of seventy divisions and, when Asquith ruled out compulsion as politically impossible, agreed to do so by voluntary recruiting."

Kitchener asked for an initial one hundred thousand - 175,000 men volunteered in the single week ending 5th September. With the help of a war poster that featured Kitchener and the words: "Join Your Country's Army", 750,000 had enlisted by the end of September. Thereafter the average ran at 125,000 men a month until June 1915 when numbers joining up began to slow down.

According to his biographer, Keith Neilson: "Kitchener brought to his new office both strengths and weaknesses. He had waged two wars in which he had dealt with all aspects of warfare, including both command and logistics. He was used to being in charge of large enterprises, he was not afraid to take responsibility and make decisions, and he enjoyed public confidence. However, he had no experience of modern European war, almost no knowledge of the British army at home, and a limited understanding of the War Office. Perhaps most importantly, he had no experience of working in a cabinet. Nevertheless in the opening stage of the war he, Asquith, and Churchill formed a dominant triumvirate in the cabinet." Arthur Conan Doyle complained: "Kitchener grew very arrogant. He had flashes of genius but was usually stupid. He could not see any use in Munitions. He was against tanks. He was against Welsh and Irish divisions. But he was a great force in recruiting."

Kitchener told Asquith that he expected the war to last at least three years with millions of casualties. He argued that the British Army must concentrate its efforts on the Western Front. However, after coming under considerable pressure from Winston Churchill, he First Lord of the Admiralty, he did agree to support the Gallipoli campaign in February 1915. By the time Kitchener withdrew the troops from the the area in January, 1916, Allied casualties totaled over 250,000 men.

The Gallipoli disaster damaged Kitchener's reputation as a military strategist. Kitchener also came under attack for a shortage of military supplies. Lord Kitchener offered to resign but Herbert Asquith decided to keep him as his Secretary of War. Lord Northcliffe attacked Kitchener in the Daily Mail: "Lord Kitchener has starved the army in France of high-explosive shells. The admitted fact is that Lord Kitchener ordered the wrong kind of shell - the same kind of shell which he used largely against the Boers in 1900. He persisted in sending shrapnel - a useless weapon in trench warfare. He was warned repeatedly that the kind of shell required was a violently explosive bomb which would dynamite its way through the German trenches and entanglements and enable our brave men to advance in safety. This kind of shell our poor soldiers have had has caused the death of thousands of them."

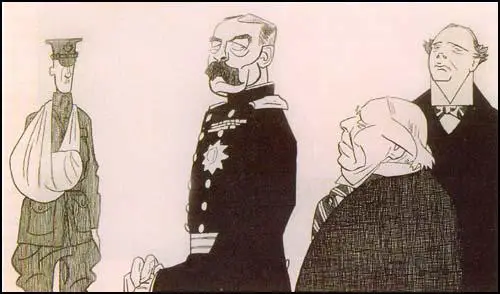

Lord Kitchener telling Herbert Asquith and Winston Churchill that things are not as

bad as they look. Cartoon from the German magazine, Simplicissimus (May, 1915)

The journalist, Charles Repington, had a more positive view of Kitchener but was still critical of his role in the war: "The services which he rendered in the early days of the war cannot be forgotten. They transcend those of all the lesser men who were his colleagues, some few of whom envied his popularity. His old manner of working alone did not consort with the needs of this huge syndicalism, modern war. The thing was too big. He made many mistakes. He was not a good Cabinet man. His methods did not suit a democracy. But there he was, towering above the others in character as in inches, by far the most popular man in the country to the end, and a firm rock which stood out amidst the raging tempest."

In the spring of 1916 Herbert Asquith decided to send Kitchener to Russia in an attempt to rally the country in its fight against Germany. On 5th June 1916, Horatio Kitchener was drowned when the HMS Hampshire on which he was traveling to Russia, was struck a mine off the Orkneys. C. P. Scott, the editor of the Manchester Guardian, remarked: "he could not have done better than to have gone down, as he was a great impediment lately".

Primary Sources

(1) Winston Churchill, The River War: An Historical Account of The Reconquest of the Soudan (1899)

After the failure of the attack from Kerreri the whole Anglo-Egyptian army advanced westward, in a line of bayonets and artillery nearly two miles long, and drove the Dervishes before them into the deserts, so that they could by no means rally or re-form. The Egyptian cavalry, who had returned along the river, formed line on the right of the infantry in readiness to pursue. At half-past eleven Sir H. Kitchener shut up his glasses, and, remarking that he thought the enemy had been given "a good dusting," gave the order for the brigades to resume their interrupted march on Omdurman - a movement which was possible, now that the forces in the plain were beaten. The Brigadiers thereupon stopped the firing, massed their commands in convenient formations, and turned again towards the south and the city. The Lincolnshire Regiment remained detached as a rearguard.

Meanwhile the great Dervish army, which had advanced at sunrise in hope and courage, fled in utter rout, pursued by the Egyptian cavalry, harried by the 21st Lancers, and leaving more than 9,000 warriors dead and even greater numbers wounded behind them.

Thus ended the Battle of Omdurman - the most signal triumph ever gained by the arms of science over barbarians. Within the space of five hours the strongest and best-armed savage army yet arrayed against a modern European Power had been destroyed and dispersed, with hardly any difficulty, comparatively small risk, and insignificant loss to the victors.

(2) Arthur Conan Doyle, The British Campaigns in Europe: 1914-1918 (1928)

Kitchener grew very arrogant. He had flashes of genius but was usually stupid. He could not see any use in Munitions. He was against tanks. He was against Welsh and Irish divisions. But he was a great force in recruiting. Asquith said of him, "he is not a great man. He is a great poster."

(3) In his book Margin Released, J. B. Priestley described meeting Lord Kitchener in 1915.

I had a close view, finding him older and greyer than the familiar pictures of him. The image I retained was of a rather bloated purplish face and glaring but somehow jellied eyes. A year later, when we heard he had been drowned, I felt no grief, for it did not seem to me that a man had lost his life: I saw only a heavy shape, its face now an idol's going down and down into the northern sea. yet it was he - and he alone - who had raised us new soldiers out of the ground.

(4) Lord Northcliffe, Daily Mail (21st May, 1915)

Lord Kitchener has starved the army in France of high-explosive shells. The admitted fact is that Lord Kitchener ordered the wrong kind of shell - the same kind of shell which he used largely against the Boers in 1900. He persisted in sending shrapnel - a useless weapon in trench warfare. He was warned repeatedly that the kind of shell required was a violently explosive bomb which would dynamite its way through the German trenches and entanglements and enable our brave men to advance in safety. This kind of shell our poor soldiers have had has caused the death of thousands of them.

(5) Charles Repington, diary entry (9th June, 1916)

The torpedoing or mining of the Hampshire, and the drowning of nearly every one on board, including Lord Kitchener, O'Beirne, and FitzGerald, is a great tragedy. They were on their way to Russia, and were blown up off the Orkneys. The news came while many of our friends were selling at a bazaar in the Caledonian Market, and the women of the East End shed tears at the news. We hoped against hope, but no doubt now remains. A great figure gone. The services which he rendered in the early days of the war cannot be forgotten. They transcend those of all the lesser men who were his colleagues, some few of whom envied his popularity. His old manner of working alone did not consort with the needs of this huge syndicalism, modern war. The thing was too big. He made many mistakes. He was not a good Cabinet man. His methods did not suit a democracy. But there he was, towering above the others in character as in inches, by far the most popular man in the country to the end, and a firm rock which stood out amidst the raging tempest.