Alexei Rykov (original) (raw)

Alexei Rykov, the son of peasants, was born in 1881. He joined the Social Democratic Labour Party (SDLP) at the age of 20 and supported the Bolsheviks after the split with the Mensheviks in 1903. Rykov worked as a Bolshevik agent in Moscow and St. Petersburg and played an active role in the 1905 Revolution.

Rykov resented the dictatorial style of Vladimir Lenin and in 1910 he broke with the Bolsheviks. He became a leading member of the Moscow Soviet and called for a left-wing coalition to be formed in Russia.

In September, 1917, Rykov was invited to join the Bolshevik Central Committee and the Petrograd Soviet.Later that month Lenin sent a message to the Bolshevik Central Committee via Ivar Smilga. "Without losing a single moment, organize the staff of the insurrectionary detachments; designate the forces; move the loyal regiments to the most important points; surround the Alexandrinsky Theater (i.e., the Democratic Conference); occupy the Peter-Paul fortress; arrest the general staff and the government; move against the military cadets, the Savage Division, etc., such detachments as will die rather than allow the enemy to move to the center of the city; we must mobilize the armed workers, call them to a last desperate battle, occupy at once the telegraph and telephone stations, place our staff of the uprising at the central telephone station, connect it by wire with all the factories, the regiments, the points of armed fighting, etc."

Joseph Stalin read the message to the Central Committee. Nickolai Bukharin later recalled: "We gathered and - I remember as though it were just now - began the session. Our tactics at the time were comparatively clear: the development of mass agitation and propaganda, the course toward armed insurrection, which could be expected from one day to the next. The letter read as follows: 'You will be traitors and good-for-nothings if you don't send the whole (Democratic Conference Bolshevik) group to the factories and mills, surround the Democratic Conference and arrest all those disgusting people!' The letter was written very forcefully and threatened us with every punishment. We all gasped. No one had yet put the question so sharply. No one knew what to do. Everyone was at a loss for a while. Then we deliberated and came to a decision. Perhaps this was the only time in the history of our party when the Central Committee unanimously decided to burn a letter of Comrade Lenin's. This instance was not publicized at the time." It was proposed that the Central Committee should reject Lenin's plan for insurrection, but this step was turned down. Eventually it was decided to postpone any decision on the matter.

Leon Trotsky was the main figure to argue for an insurrection whereas Rykov, Lev Kamenev, Gregory Zinoviev, Alexei Rykov and Victor Nogin led the resistance to the idea. They argued that an early action was likely to result in the Bolsheviks being destroyed as a political force. As Robert V. Daniels, the author of Red October: The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 (1967) has explained why Zinoviev felt strongly about the need to wait: "The experience of the summer (the July Days) had brought him to the conclusion that any attempt at an uprising would end as disastrously as the Paris Commune of 1871; revolution was was inevitable, he wrote at the time of the Kornilov crisis, but the party's task for the time being was to restrain the masses from rising to the provocations of the bourgeoisie."

Rykov was appointed to the Military Revolutionary Committee in Moscow. The Bolsheviks set up their headquarters in the Smolny Institute. The former girls' convent school also housed the Petrograd Soviet. Under pressure from the nobility and industrialists, Alexander Kerensky was persuaded to take decisive action. On 22nd October he ordered the arrest of the Military Revolutionary Committee. The next day he closed down the Bolshevik newspapers and cut off the telephones to the Smolny Institute.

At a secret meeting of the Bolshevik Central Committee on 23rd October 1917, attended by Lenin, Gregory Zinoviev, Lev Kamenev, Alexandra Kollontai, Joseph Stalin, Leon Trotsky, Yakov Sverdlov, Moisei Uritsky, Felix Dzerzhinsky, Andrey Bubnov and Grigori Sokolnikov, Lenin insisted that the Bolsheviks should take action before the elections for the Constituent Assembly. "The international situation is such that we must make a start. The indifference of the masses may be explained by the fact that they are tired of words and resolutions. The majority is with us now. Politically things are quite ripe for the change of power. The agrarian disorders point to the same thing. It is clear that heroic measures will be necessary to stop this movement, if it can be stopped at all. The political situation therefore makes our plan timely. We must now begin thinking of the technical side of the undertaking. That is the main thing now. But most of us, like the Mensheviks and the Socialist Revolutionaries, are still inclined to regard the systematic preparation for an armed uprising as a sin. To wait for the Constituent Assembly, which will surely be against us, is nonsensical because that will only make our task more difficult."

A long and bitter discussion followed Lenin's summons to insurrection. Trotsky claimed that Lenin's proposal for immediate revolt met with very little enthusiasm: "The debate was stormy, disorderly, chaotic. The question now was no longer only the insurrection as such; the discussion spread to fundamentals, to the basic goals of the Party, the Soviets; were they necessary? What for? Could they be dispensed with? The most striking thing was the fact that people began to deny the possibility of the insurrection at the given moment; the opponents even reached the point in their arguments where they denied the importance of a Soviet Government."

Rykov, Victor Nogin, Gregory Zinoviev, Lev Kamenev and David Riazanov were the main opponents of insurrection. Lenin, backed up by Leon Trotsky, insisted that the Bolsheviks should attempt to gain power. In the early hours of the morning Lenin finally won his victory. Trotsky claimed: "I do not remember the proportion of the votes, but I know that 5 or 6 were against it. There were many more votes in favour, probably about 9, but I do not vouch for the figures."

On the evening of 24th October, 1917, orders were given for the Bolsheviks began to occupy the railway stations, the telephone exchange and the State Bank. The following day the Red Guards surrounded the Winter Palace. Inside was most of the country's Cabinet, although Kerensky had managed to escape from the city.

Despite his differences with Vladimir Lenin, Rykov was appointed Commissar of the Interior (1917-18), Chairman of the Supreme Council of National Economy (1918-20) and Deputy Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars (1921-24) and Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars (1924-29).

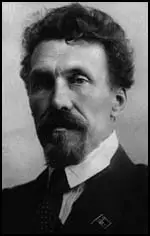

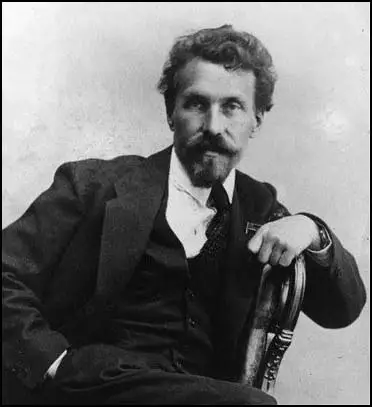

Alexei Rykov

In 1925 Joseph Stalin switched his support from Lev Kamenev and Gregory Zinoviev to Nickolai Bukharin and now began advocating the economic policies of Rykov and Bukharin. The historian, Isaac Deutscher, the author of Stalin (1949) has pointed out: "Tactical reasons compelled him to join hands with the spokesmen of the right, on whose vote in the Politburo he was dependent. He also felt a closer affinity with the men of the new right than with his former partners. Bukharin, Rykov, and Tomsky accepted his socialism in one country, while Zinoviev and Kamenev denounced it. Bukharin may justly be regarded as the co-author of the doctrine. He supplied the theoretical arguments for it and he gave it that scholarly polish which it lacked in Stalin's more or less crude version."

Stalin wanted an expansion of the New Economic Policy that had been introduced several years earlier. Farmers were allowed to sell food on the open market and were allowed to employ people to work for them. Those farmers who expanded the size of their farms became known as kulaks. Bukharin believed the NEP offered a framework for the country's more peaceful and evolutionary "transition to socialism". He disregarded traditional party hostility to kulaks and called on them to "enrich themselves".

When Leon Trotsky, Lev Kamenev and Gregory Zinoviev eventually began attacking his policies, Joseph Stalin argued they were creating disunity in the party and managed to have them expelled from the Central Committee. The belief that the party would split into two opposing factions was a strong fear amongst active communists in the Soviet Union. They were convinced that if this happened, western countries would take advantage of the situation and invade the Soviet Union. Stalin claimed that there was a danger that the party would split into two opposing factions. If this happened, western countries would take advantage of the situation and invade the Soviet Union. On 14th November 1927, the Central Committee decided to expel Trotsky and Zinoviev from the party. This decision was ratified by the Fifteenth Party Congress in December. The Congress also announced the removal of another 75 oppositionists, including Kamenev. Rykov supported these moves.

In December 1927 it was reported to Joseph Stalin that the Soviet Union faced a severe shortfall in grain supplies. On 6th January, 1928, Stalin sent out a secret directive threatening to sack local party leaders who failed to apply "tough punishments" to those guilty of "grain hoarding". During that winter Stalin began attacking kulaks for not supplying enough food for industrial workers. He also advocated the setting up of collective farms. The proposal involved small farmers joining forces to form large-scale units. In this way, it was argued, they would be in a position to afford the latest machinery. Stalin believed this policy would lead to increased production. However, the peasants liked farming their own land and were reluctant to form themselves into state collectives.

Stalin was furious that the peasants were putting their own welfare before that of the Soviet Union. Local communist officials were given instructions to confiscate kulaks property. This land was then used to form new collective farms. There were two types of collective farms in the 1920s. The sovkhoz (land was owned by the state and the workers were hired like industrial workers) and the kolkhoz (small farms where the land was rented from the state but with an agreement to deliver a fixed quota of the harvest to the government).

Stalin blamed Rykov and Nickolai Bukharin and the New Economic Policy for the failures in agriculture. Bukharin feared that he would be removed from power and made overtures to Lev Kamenev to prevent this. "The disagreements between us and Stalin are many times more serious than the ones we had with you. We (those of the right of the party) wanted Kamenev and Zinoviev restored to the Politburo." This placed Rykov and Bukharin in great danger as Stalin's agents were listening to his telephone conversations.

In the spring of 1928, Joseph Stalin began dismissing local officials who were known to supporters of Bukharin. At the same time, Stalin made speeches attacking the kulaks for not supplying enough food for the industrial workers. Bukharin was furious and sought help from Rykov and Maihail Tomsky, in an effort to combat Stalin. Edvard Radzinsky, the author of Stalin (1996), has pointed out: "In spring 1928 Bukharin mobilized his supporters, Rykov, then head of government, and the Trades Union leader Tomsky, and they all wrote notes to the Politburo about the threat to the alliance between the proletariat and the peasantry, naturally invoking Lenin. Stalin did not intend to annihilate Bukharin just yet. He was making a 180-degree turn, and needed Bukharin to explain it from the standpoint of Marxism."

In meetings of the Politburo, Bukharin was joined by Rykov and Tomsky in opposing Stalin's agricultural policy. However, Mikhail Kalinin and Kliment Voroshilov, after initially supporting Bukharin, backed down under pressure from Stalin. At these meetings Stalin argued that the kulaks were a class that needed to be destroyed: "The advance toward socialism inevitably leads to resistance on the part of the exploiting classes... When class war is waged there has to be terror. If class war is intensified - the terror must also be intensified." Stalin called Bukharin to his office and suggested a deal: "You and I are the Himalayas - all the others are nonentities. Let's reach an understanding." However, Bukharin refused to back-down, but agreed to refrain from making speeches or writing articles on this subject in fear of being accused of dividing the party.

In July, 1928, Bukharin went to see Lev Kamenev. He told him that he now realized that Joseph Stalin had played one group off against the other to gain complete power for himself: "He is an unprincipled intriguer who subordinates everything to his appetite for power. At any given moment he will change his theories in order to get rid of someone," Bukharin told Kamenev. He went on to claim that Stalin would eventually destroy the communist revolution. "Our disagreements with Stalin are far, far, more serious than those we have with you," he argued and suggested that they should join forces to end Stalin's dictatorship of the party.

In November, 1929, Rykov and Nickolai Bukharin, were removed from the Politburo. Stalin now decided to declare war on the kulaks. The following month he made a speech where he argued: "Now we have the opportunity to carry out a resolute offensive against the kulaks, break their resistance, eliminate them as a class and replace their production with the production of kolkhozes and sovkhozes… Now dekulakisation is being undertaken by the masses of the poor and middling peasant masses themselves, who are realising total collectivisation. Now dekulakisation in the areas of total collectivisation is not just a simple administrative measure. Now dekulakisation is an integral part of the creation and development of collective farms. When the head is cut off, no one wastes tears on the hair."

In 1938 Rykov Nikolay Bukharin, Genrikh Yagoda, Nikolai Krestinsky and Christian Rakovsky were arrested and accused of being involved with Leon Trotsky in a plot against Joseph Stalin. Found guilty Alexei Rykov was executed on 15th March, 1938.

Primary Sources

(1) Robert V. Daniels, Red October: The Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 (1967)

On the 21st, for the first time since the Kornilov affair, the old lines of cleavage reappeared in the Bolshevik Central Committee when some of the members proposed that the party stage a walkout from the Democratic Conference. The cautious wing won a majority and rejected the proposal. Action also had to be taken on the decision by the conference to convoke a provisional legislative body, to be known as the "Council of the Republic." (More familiarly termed the "Pre-Parliament," the Council of the Republic convened October 7, and it was still in session when the Provisional Government was overthrown on October 25.) On the question whether to participate in the Pre-Parliament the Central Committee split almost evenly. Rykov reported for the Bolshevik moderates, and Trotsky for the bolder group. Trotsky prevailed by a vote of 9 to 8 to boycott the Pre-Parliament altogether, but because of the evenness of the division the Committee then decided to refer the whole question to the gathering of Bolshevik members of the Democratic Conference which was scheduled to meet later the same day.

Trotsky and Rykov again presented their respective cases to this larger assemblage. Trotsky was supported, interestingly enough, by Stalin, while Rykov was backed by Kamenev. This time, with the preponderance of less venturesome provincial delegates, the vote went to the opponents of boycotting the Pre-Parliament, by a count of 77 to 50. Nogin expressed the relief of the cautious Bolsheviks: boycotting the Pre-Parliament would be an "invitation to insurrection" that he was not ready to contemplate. A lesser Bolshevik named Zhukov confided to the Mensheviks, "We haven't forgotten the July Days and won't commit any new stupidity." Lenin, now in Vyborg, Finland, was increasingly disturbed at the temporizing of the Petrograd leadership, with one exception that came to his attention: "Trotsky was for the boycott: Bravo, Comrade Trotskyl" Otherwise, "At the top of our party we note vacillations that may become ruinous."

(2) Isaac Deutscher, Stalin (1949)

Tactical reasons compelled him to join hands with the spokesmen of the right, on whose vote in the Politburo he was dependent. He also felt a closer affinity with the men of the new right than with his former partners. Bukharin, Rykov, and Tomsky accepted his socialism in one country, while Zinoviev and Kamenev denounced it. Bukharin may justly be regarded as the co-author of the doctrine. He supplied the theoretical arguments for it and he gave it that scholarly polish which it lacked in Stalin's more or less crude version."

(3) Edvard Radzinsky, Stalin (1996)

In spring 1928 Bukharin mobilized his supporters, Rykov, then head of government, and the Trades Union leader Tomsky, and they all wrote notes to the Politburo about the threat to the alliance between the proletariat and the peasantry, naturally invoking Lenin. Stalin did not intend to annihilate Bukharin just yet. He was making a 180-degree turn, and needed Bukharin to explain it from the standpoint of Marxism.