Cuxhaven (original) (raw)

Home - Search - Browse - Alphabetic Index: 0- 1- 2- 3- 4- 5- 6- 7- 8- 9

A- B- C- D- E- F- G- H- I- J- K- L- M- N- O- P- Q- R- S- T- U- V- W- X- Y- Z

Cuxhaven

As the only site in Germany with an unrestricted over-water firing sector over the North Sea, Cuxhaven was once touted as 'the Cape Canaveral of Germany'. Primarily known to space historians for the three post-war V-2 launches under project Backfire, it played an important role in the nascent post-World War II German rocketry. A nearly completely unknown series of scientific sounding rocket launches were made from the area in 1957-1964 before the launch site was closed on (purportedly) safety and (actually) military grounds.

First Launch: 1945-10-02. Last Launch: 1963-12-05. Number: 14 . Location: Niedersachsen. Longitude: 8.59 deg. Latitude: 53.85 deg. Apogee: 5.00 km (3.10 mi).

The dunes of nearby Altenwalde were first used for military purposes in 1896 for German army maneuvers. In 1912 the German Navy installed concrete emplacements for test of high-caliber naval guns. During World War I coast artillery was installed for the protection of the Reich against invasion.

Cuxhaven first became involved in rocketry in 1933 when Gerhard Zucker came to town with his operational rocket. The amazing recoverable cruise missile was 5 m long, had a thrust of 360 kg and a takeoff mass of 200 kg. It was the prototype of rockets that were supposedly capable of cruising out 400 km from their launch point at an altitude of 1000 m and a speed of 1000 m/s. They could then return after having delivered a bomb payload or having taken reconnaissance photographs. Zucker proposed a more modest demonstration, a delivery of rocket mail from the coast at Duhnen to the island of Schaernhorst, 15 km away. After being stuck in a ditch while being taken out to the field for a February launch attempt, the big day finally came on 9 April 1933. A huge crowd of 5000 local folk, officials, and camera teams from Fox Movietone gathered to witness the great event. After staggering 15 m into the air, the great torpedo came crashing down. Zucker nevertheless sold postal 'covers' from the flight to gullible philatelists, and went on to take his fraud elsewhere.

Local rocket enthusiast Hugo Woerdemann was, like so many others, inspired by Fritz Lang's Frau im Mond . When Richard Tiling came to Cuxhaven in the summer of 1934 to conduct flight experiments, Wordemann assisted and had his first taste of practical rocketry. Tiling, together with his brother Reinhold, were early German rocket pioneers. Reinhold had launched Germany's first postal rocket from Duemmer See on 15 April 1931. In 1933 he and his assistants died horribly after an explosion and fire in their workshop, but his brother carried on his work. Woerdemann went on to pursue rocketry at the Technical Hochschule in Dresden. He eventually wound up in Peenemuende, specializing in V-2 radio guidance, instrumentation, and telemetry.

The second world war brought rocketry to Cuxhaven again. Altenwalde was reactivated, various parts of it and the adjacent peninsula at first being used for flak batteries, radio intercept stations, coastal defenses, and a hand gunnery range. Following the heavy bombing of Peenemuende by the allies on 17 August 1943 it was decided to disperse the research facilities. In early 1944 a detachment of researchers set up launch ramps for V-1 cruise missiles and continued development of the missile from the site. In 1945, as the allied armies approached, V-2 rockets and their equipment were abandoned in nearby Liebnau near Nieburg an der Weser.

Cuxhaven was in the British zone after the fall of Germany. A decision was made by the British military to fully document the V-2 rocket system before the knowledge was lost. In the absence of formal German documentation, it was decided to force German rocket troops to demonstrate V-2 handling and firing procedures by actually preparing and launching some rockets. Altenwalde was chosen as the testing site. The British utilized the hangars and other facilities of the former German Navy Artillery Range for handling, logistics and preparation of the missiles. Field Marshal Montgomery took a special interest in the proceedings, and the author Eric Ambler left a fairly complete description in his memoirs.

By late summer 1945 some two hundred Peenemuende scientists, 200 V-2 firing troops, and 600 ordinary POWs were transported to Cuxhaven. Upon arrival, they were split into two groups and interrogated. The information given by each group was then compared to ensure inaccuracies and deceptions were eliminated. However finding the test rockets proved difficult. The Americans had already raided the V-2 factory at Nordhausen and shipped everything usable to New Mexico. The British were able to only come up with enough parts to assemble 8 rockets for testing. However several key perishable components and firing vehicles were still missing. In a huge enterprise search teams fanned out over the occupied territories, trying to beat American and Russian competitors. 400 railway cars and 70 Lancaster bomber flights brought to Cuxhaven 250,000 parts and 60 specialized vehicles. The hardest items to locate were usable batteries to operate the guidance gyro platforms. Tail units could not be located anywhere and the Americans finally agreed to bring back a few from the United States. A new concrete launch pad was poured and an enormous tower built from prefabricated military bridge elements. 2,500 British troops assisted in completing site construction.

On October 1, the first V-2 launch attempt failed due to a faulty igniter. Three success firings followed. The final launch, on October 15, was witnessed by a unique crowd of British, American, and Russian rocket engineers.

In 1948-1950 the allies demilitarized the peninsula. The massive concrete emplacements were broken up for use in roads. A 160 metric ton crane was demolished, and the train tracks crisscrossing the area were torn out for scrap. 24 families moved into the old barracks and the various military buildings were declared to be an industrial park.

Meanwhile the old German enthusiasm was stirring. Rudolf Nebel was one of the few German rocket pioneers who did not leave the country to work for one of the conquering powers. Despite the allied prohibition on aerospace research, Nebel, together with engineers Karl Poggensee and Albert Puellenberg, began renewed German work on rockets for peaceful purposes. They participated in the first meetings of the new International Astronautical Federation in Paris in 1950 and London in 1951. Nebel gave a lecture on rocketry and space travel in Cuxhaven on 6 April 1951. Local naval engineer Hermann Geveke, inspired by the talk, began pushing Cuxhaven as the ideal location for a future German spaceport. In an 8 June 1951 interview he declared that Cuxhaven could be the future 'Gateway to Space'. He noted the location on the coast allowed an unrestricted 45 degree firing sector over the North Sea. He argued that far from scaring away potential beach resort guests, the rocket launches would provide a tremendous tourist attraction.

In 1952 the Allied powers lifted the aerospace research ban. Karl Poggensee conducted the first of 40 launches of small rockets of 50 kgf from a farmer's field in Hespenbuscher Heide near Wildeshaven in August 1952. These reached altitudes of 250-6000 m over the next few years.

On 21 September 1952 Friedrich Staats founded the German Rocket Society (Deutsche Raketengesellschaft, DRG). The twelve founding members grew to 1300 in 14 countries by 1963. (We shall refer to this organization as the DRG. In fact, it was founded as the German Society for Rocket Technology 'Arbeitsgemeinschaft f�r Raketentechnik' (DAFRA), became the DRG in January 1958, changed its name again in 1962 to the 'Hermann-Oberth-Gesellschaft' (HOG), and finally merged into the current 'Deutsche Gesellschaft fuer Luft- und Raumfahrt - Lilienthal - Oberth e.V'. (DLGR) in 1993).

The DRG began experimental work on civilian rockets almost immediately, using the farmstead at Hespenbuscher Heide for flight tests. As a practical matter it was decided to develop small 'oil spray' rocket, a hand-launched projectile that would spray oil to calm waters during naval rescues. This rocket had a range of 300 m, and flew at an altitude of 10-20 m over the water, dispersing 1000 cc of light oil over an area of 10,000 square meters. Canted fins assured stability and even dispersal of the oil. After three years of development, the rocket was tested by the German rescue services, but a production contract was never received.

The first DRG test stand for larger motors was set up in December 1955 in Bremen. It was clear that the farmstead at Hespenbuscher Heide was not adequate for tests of larger rockets. The DRG needed a facility with government clearances to reach outer space. In January 1957 Geveke finally convinced the Cuxhaven city government to designate the mouth of the Elbe as an official Rocket Research Centre. Surviving coastal bunkers at Sahlenburg were converted into an explosive material dump and electrical switching station. Launches of over 100 rockets, ranging from student models to sounding rockets ascending to over 100 km, took place from Cuxhaven beginning on 24 August 1957.

In parallel with this peaceful work the remilitarization of Germany and the area had begun. The allied prohibition on German military development was lifted in 1955 and in 1956 the Heinrich-Wilhelm-Kopf barracks were built on the grounds of the old Altenwalde military base to accommodate the 47th Panzer battalion. The military reservation was again to be used for military exercises.

In early 1960 Berthold Seliger became a member of the DRG. Seliger was able to obtain contracts from both the Max Planck Institute (for rocket launches carrying stratospheric probes) and from Waffen und Luftruestung (for military test launches). His firm conducted launches that reached 120 km altitude by 1963.

Although no member of the DRG had ever even been injured in a rocket experiment, they found themselves banned from further experiments on June 6, 1964. Officially the reason was the death of a boy in a rocket experiment in Braunlage a few weeks before -- an experiment conducted by the same charlatan Gerhard Zucker, who had inaugurated rocketry at Cuxhaven 31 years earlier! Others believe that the real motivation was to clear the facility for further launches of Seliger's military rockets. However there is no record that Seliger did in fact conduct further launches. By the mid-1960's the German government decided that any German missile development would only be done by major aerospace firms and only in collaboration with other NATO countries. The restricted military area still exists at Cuxhaven, but the former rocket firing grounds are now a protected national park.

Many thanks to Harald Lutz for obtaining and providing the source materials telling the story of this 'forgotten' piece of space history...

Family: Suborbital Launch Site. People: Seliger. Country: Germany. Launch Vehicles: V-2, Zucker Rocket, Mohr Rocket, Kumulus, Cirrus I, Cirrus II, Seliger 1, Seliger 2, Seliger 3. Agency: British Army. Bibliography: 556, 557, 561.

Photo Gallery

|

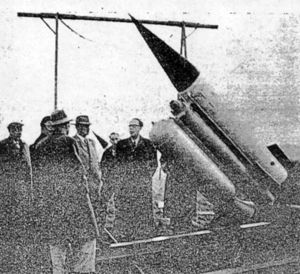

Zucker RocketZucker Rocket at Cuxhaven, April 1933Credit: Via Harald Lutz |

|---|

|

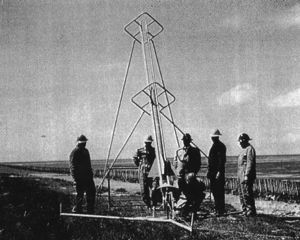

Hespenbuscher HeideLaunch from Hespenbuscher Heide, 1952Credit: Via Harald Lutz |

|---|

|

CuxhavenLocation of CuxhavenCredit: © Mark Wade |

|---|

|

German EnthusiastsThe emergence and reemergence of German rocketry - Von Braun and Nebel, 1933 and DRG Members, 1958Credit: Via Harald Lutz |

|---|

|

Mohr RocketMohr's 5000 kgf rocketCredit: Via Harald Lutz |

|---|

|

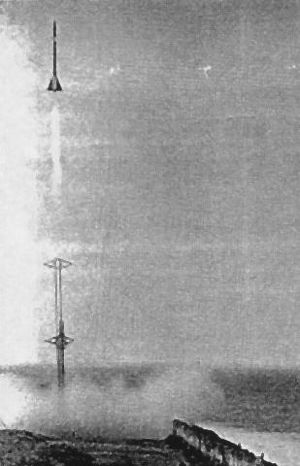

Mohr RocketMohr's Rocket, launch of 15 September 1958Credit: Via Harald Lutz |

|---|

|

Mohr RocketMohr's 7800 kgf rocketCredit: Via Harald Lutz |

|---|

|

KumulusKumulus launch preparations at Cuxhaven, 28 May 1961Credit: Via Harald Lutz |

|---|

|

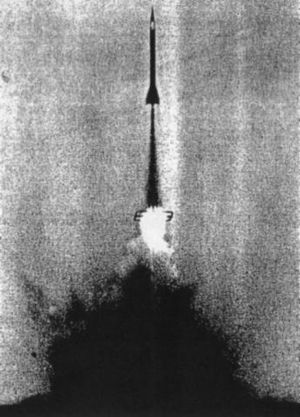

Kumulus LaunchKumulus launch to 15 kmCredit: Via Harald Lutz |

|---|

|

Cirrus II LaunchCirrus II First LaunchCredit: Via Harald Lutz |

|---|

|

Seliger and RocketSeliger examines one of his rocketsCredit: Via Harald Lutz |

|---|

|

Seliger RockerLaunch of Seliger Single Stage RocketCredit: Via Harald Lutz |

|---|

|

Seliger RocketLaunch of Seliger Three Stage RocketCredit: Via Harald Lutz |

|---|

1933 April - . Launch Site: Cuxhaven. Launch Vehicle: Zucker Rocket.

- Zucker rocket launched at Cuxhaven - . Nation: Germany. Related Persons: Zucker. Apogee: 0.0150 km (0.0093 mi).

Zucker's amazing 'operational rocket'. was supposedly a recoverable cruise missile, 5 m long, with a thrust of 360 kg and a takeoff mass of 200 kg. In actuality the missile was only an enormous hull equipped with eight powder rockets. Zucker showed up in Cuxhaven on the German North Sea coast in the winter of 1933, ready for a long-range demonstration (15 km, from the coast to Neuhaven Island). After being stuck in a ditch while being taken out to the field for a February launch attempt, the great day finally came in April 1933. A huge crowd of local folk and officials gathered to witness the event. After staggering 15 m into the air, the torpedo came crashing down.

1945 October 1 - . 13:43 GMT - . Launch Site: Cuxhaven. Launch Complex: Cuxhaven. Launch Vehicle: V-2.

- Project Backfire first attempted V-2 launch. - . Nation: UK. Attempted launch of a V-2 from Altenwalde by German technicians under British direction in order to document launch procedures. The launch was aborted on the pad and a different missile was selected for the next attempt..

1945 October 2 - . 13:43 GMT - . Launch Site: Cuxhaven. Launch Vehicle: V-2.

- Backfire 1 test - . Nation: UK. Agency: WO. Apogee: 90 km (55 mi). Launch of V-2 from Altenwalde by German technicians under British direction in order to document launch procedures. The launch was successful and the missile reached an altitude of 90 km..

1945 October 4 - . 13:15 GMT - . Launch Site: Cuxhaven. Launch Vehicle: V-2. FAILURE: Partial failure.

- Backfire 2 test - . Nation: UK. Agency: WO. Apogee: 20 km (12 mi). Partial failure; the rocket only reached 20 km altitude..

1945 October 15 - . 14:06 GMT - . Launch Site: Cuxhaven. Launch Vehicle: V-2.

- Backfire 3 test - . Nation: UK. Agency: WO. Apogee: 90 km (55 mi).

Third and final launch in Project Backfire, with allied observors. Glushko, Sokolov, Pobedonostsev; Korolev and Gaidukov kept outside fence; Von Karman, Merrill, Seifert, Pickering from US. The launch was successful and the missile reached an altitude of 90 km.

1957 August 24 - . Launch Site: Cuxhaven. Launch Complex: Cuxhaven. Launch Vehicle: Mohr Rocket.

- First launches from Spaceport Cuxhaven - . Nation: Germany.

Cuxhaven saw its first use as the 'Gateway to Space'. The DRG (German Rocket Society)'s 'Rocket Flight Day' started out with 7 firings of the 'oilspray' rocket to ranges of 100 to 300 m. The terrible weather served to demonstrate their function admirably. This was followed by a launch to 100 to 2000 m altitude of several small model rockets. This was followed by delta-winged rocket built by Koschmieder, which reached 3000 m and was recovered by parachute. Next was a prototype 20 kg meteorological rocket using a new solid propellant developed by Deutsche Dynamit AG. This produced 1500 kgf and reached Mach 1.5. The rocket rose to 4000 m but the recovery parachute deployed early and the meteorological instruments were not recovered. Finally a test of the first of Ernst Mohr's big rockets was planned. The rocket had 50 kg of propellant, produced 5 tonnes thrust, and was to have reached Mach 1.5 at burnout and an altitude of 20,000 m. However the launch was cancelled due to bad weather.

1958 June 8 - . Launch Site: Cuxhaven. Launch Complex: Cuxhaven. Launch Vehicle: Mohr Rocket.

- Mohr Rocket launch attempts - . Nation: Germany.

First attempt to launch Ernst Morhr's larege meteorological rocket. The rocket had a total mass of 150 kg, consisting of 75 kg propellant, 60 kg structure, and 15 kg payload. The motor produced 7800 kgf for 2 seconds. The rocket was 30 cm in diameter, 1.7 m long, and had a payload dart 56 mm in diameter and 1.25 m long. Three attempts were made to launch. Two hung up on the launcher, and the third was unstable after launch and crashed near the launcher.

1958 September 14 - . Launch Site: Cuxhaven. Launch Complex: Cuxhaven. Launch Vehicle: Mohr Rocket.

- Mohr Rocket reaches 50 km altitude - . Nation: Germany.

Three launches were made from Arensch, including two successful launches of the prototype of the large meteorological rocket developed by Ernst Mohr of Wuppertall. The launches were witnessed by Vice-President Ross. The redesigned Mohr rockets were 2.5 m long, 30 cm in diameter, had a total mass of 80 kg and produced 7.8 tonnes thrust. Cutoff velocity was 1200 m/s at 1200 m altitude. The payload dart then separated and coasted up to 50 km altitude. It was later planned to install meteorological instruments on these rockets.

1959 May 16 - . Launch Site: Cuxhaven. Launch Complex: Cuxhaven.

- First DRG Rocket Mail - . Nation: Germany.

First launches from Arensch to Berensch of DRG (German Rocket Society) 'postcard rockets'. 100 would be launched in the next two years. Ten launches were made carrying 5000 postcards. The subsonic 5 kg rockets were 2 m long, produced 50 kgf thrust, were recovered under three or four parachutes, and had an average accuracy of 130 m over a 3 km range.

1959 November 1 - . Launch Site: Cuxhaven. Launch Complex: Cuxhaven. LV Family: Cirrus. Launch Vehicle: Kumulus.

- First Kumulus launch - . Nation: Germany.

The first launch of a Kumulus rocket is made to 15 km altitude carrying a radio-transmitter built by Professor Max Ehmert of the Max Planck Institute. The rocket had a mass of 30.3 kg, produced 508 kgf, and reached 700 m/s. However due to the batteries becoming too cold during launch preparations, the transmitter did not function and the rocket could not be tracked.

11-12 February 1961 - . Launch Site: Cuxhaven. Launch Complex: Cuxhaven. LV Family: Cirrus. Launch Vehicle: Kumulus.

- Kumulus rocket reaches 19.75 km - . Nation: Germany.

The DRG (German Rocket Society) launched four MVR-I rockets on Saturday and two on Sunday. The Saturday launches were tracked to an altitude of 15 km and impacted 15 to 30 km from the launch point in the North Sea. The rockets were 18 cm in diameter, 2 m long, and had a mass of 24 kg. One of the Sunday launches reached 19,750 m altitude with a meteorological payload built by the Max Planck Institute. The rocket had a thrust of 508 kgf and weighted 19.9 kg. German television covered the launches.

1961 May 24 - . Launch Site: Cuxhaven. Launch Complex: Cuxhaven.

- Rocket mail in Vienna - . Nation: Austria. The DRG (German Rocket Society) launched twelve of their small mail rockets from Vienna (Wien-Aspern) with 5000 postcards aboard..

1961 May 28 - . Launch Site: Cuxhaven. Launch Complex: Cuxhaven.

- Rocket mail delivered to Neuwerk - . Nation: Germany.

The DRG (German Rocket Society) launched a 40 kg rocket over a range of 14 km to the island of Neuwerk. The missile had a thrust of 508 kgf and took 30 seconds to cover the distance. 5000 postcards were carried. This fulfilled a 28 year old plan for such a rocket flight.

1961 June 25 - . Launch Site: Cuxhaven. Launch Complex: Cuxhaven.

- Rocket mail delivered to Scharhoern - . Nation: Germany.

The DRG (German Rocket Society) launches two 3-m long, 51.9 kg, 600 kgf thrust Kumulus rockets from Arensch over the sea 18 km to the flats of the island of Scharhoern. The trip was made in 28 seconds at a top speed of 850 m/s with a payload of 5000 postcards weighing 15 kg.

1961 September 16 - . Launch Site: Cuxhaven. Launch Complex: Cuxhaven. LV Family: Cirrus. Launch Vehicle: Kumulus.

- Cirrus rocket reaches 50 km altitude - . Nation: Germany.

The first Cirrus rockets are launched. Cirrus I, a two stage rocket, with each stage providing 508 kgf, reached a velocity of 750 m/s (Mach 2.5) and 35 km altitude. Cirrus II, 4.155 m long, with a thrust of 1.8 tonnes, reached 1000 m/s and an altitude of 50 km. Kumulus I and II took biological specimens aloft. Each Kumulus had a mass of 28 kg, was 3 m long, produced 508 kgf, and reached 750 m/s, Mach 2.0. Kumulus I carried the Mexican salamander Lotte to an altitude of 12 km. Lotte landed safely in the Cuxhaven flats. Kumulus II took the goldfish Max to an altitude of 15 km, but Max, enclosed in a plexiglass globe, made a hard landing.

1961 September 16 - . Launch Site: Cuxhaven. LV Family: Cirrus. Launch Vehicle: Cirrus II.

1961 September 16 - . Launch Site: Cuxhaven. LV Family: Cirrus. Launch Vehicle: Cirrus I.

1962 September 9 - . Launch Site: Cuxhaven. Launch Complex: Cuxhaven.

- Rocket mail at Cuxhaven - . Nation: Germany. The DRG (German Rocket Society) made postal launches from spaceport Cuxhaven..

1962 November 19 - . Launch Site: Cuxhaven. Launch Complex: Cuxhaven. Launch Vehicle: Seliger.

- Seliger rocket reaches 40 km - . Nation: Germany. Related Persons: Seliger. Berthold Seliger made the first launches of his rockets from Cuxhaven. Three 3.4 m long, single stage rockets reached altitudes of 40 km. The on-board transmitters were tracked by the Bochum Observatory..

1962 November 19 - . Launch Site: Cuxhaven. Launch Vehicle: Seliger 1.

1962 November 19 - . Launch Site: Cuxhaven. Launch Vehicle: Seliger 1.

1962 November 19 - . Launch Site: Cuxhaven. Launch Vehicle: Seliger 1.

1963 January 13 - . Launch Site: Cuxhaven. Launch Complex: Cuxhaven.

- DRG launches at Cuxhaven - . Nation: Germany. The DRG (German Rocket Society) launched three model rockets but they fell in the flats and were not recovered..

1963 February 7 - . Launch Site: Cuxhaven. Launch Complex: Cuxhaven. Launch Vehicle: Seliger.

- Seliger rockets reach 80 km. - . Nation: Germany. Related Persons: Seliger.

Seliger launched three rockets. The 3.4 m long single stage version reached an altitude of 52 km, and the 6.0 m long two stage version reached 80 km. Each stage had a thrust of 5000 kgf. Bochum Observatory tracked the radio transmitters of the payloads during their ascent. The wreckage of the missiles was found on the flats. Seliger announced plans to launch a three-stage rocket to 150 km altitude.

1963 February 7 - . Launch Site: Cuxhaven. Launch Vehicle: Seliger 1.

1963 February 7 - . Launch Site: Cuxhaven. LV Family: Seliger 1. Launch Vehicle: Seliger 2.

1963 February 7 - . Launch Site: Cuxhaven. LV Family: Seliger 1. Launch Vehicle: Seliger 2.

1963 May 2 - . Launch Site: Cuxhaven. Launch Complex: Cuxhaven. Launch Vehicle: Seliger.

- Seliger rocket reaches 120 km altitude. - . Nation: Germany. Related Persons: Seliger.

Seliger launched his 12.8 m long, three-stage rocket at an attempt to reach an altitude of 150 km. The effects of his contracts with the military were apparent. The 74th Panzer batallion at Altenwalde provided security, field communications, two jeeps as command posts, and a helicopter to search for the missile after the flight. The first launch of the day was that of a single-stage rocket to 50 km altitude. The mission was to measure high altitude winds and test the new parachute recovery system. The payload was successfully recovered in Wernerwald. Preparation of the three stage rocket took three hours, leading up to the planned 16:00 launch time. The 6 m long rocket lifted off at 16:03 but only reached an altitude of 120 km.

1963 May 2 - . Launch Site: Cuxhaven. Launch Vehicle: Seliger 1.

1963 May 2 - . 15:03 GMT - . Launch Site: Cuxhaven. LV Family: Seliger 1. Launch Vehicle: Seliger 3.

1963 December 5 - . Launch Site: Cuxhaven. Launch Complex: Cuxhaven. Launch Vehicle: Seliger.

- First Cuxhaven military launches - . Nation: Germany. Related Persons: Seliger.

The first military launches were made from Cuxhaven since the Backfire V-2 launches of 1945. Seliger, under contract to Waffen und Luftruestung AG (Weapons and Air Development Inc) of Hamburg launched a test rocket. The altitude was restricted to 30 km by a new regulation of the Lower Saxony Economy and Trade Ministry.

1963 December 5 - . Launch Site: Cuxhaven. Launch Vehicle: Seliger 1.

1964 March 22 - . Launch Site: Cuxhaven. Launch Complex: Cuxhaven.

- DRG launches at Cuxhaven - . Nation: Germany. The DRG (German Rocket Society) conducted a series of ten student model rocket test launches. Some of these tested a new airbrake mechanism for recovery of the rocket in lieu of a parachute..

1964 June 6 - . Launch Site: Cuxhaven. Launch Complex: Cuxhaven.

- Further use of Cuxhaven for rocket launches banned. - . Nation: Germany. Related Persons: Zucker.

The DRG (German Rocket Society) planned a new series of rocket launches but found further launches throughout the Germany due to a new regulation prohibiting such launches over 100 m altitude. This rule was enacted when a student was killed at Braunlage in Lower Saxony during a rocket experiment by Gerhard Zucker.

Home - Search - Browse - Alphabetic Index: 0- 1- 2- 3- 4- 5- 6- 7- 8- 9

A- B- C- D- E- F- G- H- I- J- K- L- M- N- O- P- Q- R- S- T- U- V- W- X- Y- Z

© 1997-2019 Mark Wade - Contact

© / Conditions for Use