Anton Rubinstein (Composer, Arranger) - Short Biography (original) (raw)

Recordings/Discussions

- Introduction

- Cantatas

- Other Vocal Works

- Instrumental Works

- Piano Transcriptions

- Other Arrangements

- Performers Vocal

- Performers Instrumental

- General Topics

- Articles

- Bach & Other Composers

- Books

- Movies

Background Information

- J.S. Bach Biography

- Lutheran Church Year

- Readings from Bible

- Texts & Translations

- Scores

- Music

- References

- Commentaries

- BWV & BWV Anh Lists

- Chorale Texts

- Chorale Melodies

- Guide to Bach Tour

- Bach Festivals & Series

- Arts & Memorabilia

- The Face of Bach

- Terms & Abbreviations

Performer Bios

Poet/Composer Bios

Additional Information

- Order of Discussion

- Schedule of Concerts

- TNT's J.S. Bach Pages

- Links to Other Sites

- Search Works/Movements

- Search BCW

- Sitemap

- What's New?

- New & Upcoming Recordings

- Join Mailing Lists/Contribute

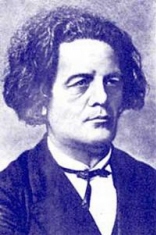

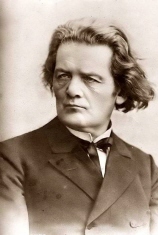

| Anton Rubinstein (Composer, Arranger) | |

|---|---|

| Born: November 16 or 28, 1829 - Vikhvatinï [Wechwotynetz, Volhynia], Ukraine [Podoliya] Died: November 8 or 20, 1894 - Peterhof [now Petrodvorets) | |

| The Russian pianist, composer, conductor and teacher, Anton Grigorýevich [Gregor] Rubinstein [Rubinshteyn], was the brother of Nikolay Rubinstein. He was one of the greatest pianists of the 19th century, his playing was compared with Franz Liszt. He was also an influential, if controversial figure in Russian musical circles, and an exceptionally prolific composer. | |

| Life | |

| After early piano lessons from his mother, at the age of 7 Anton Rubinstein went to a piano teacher named A.I. Villoing He gave his first public concert in 1839 and between 1840 and l843 Villoing took him on an extended tour of Europe. Child virtuosos were at that time fashionable, he gave concerts in Pans, where he met Frédéric Chopin and Franz Liszt, Holland, where he had what was to prove a fruitful meeting with members of the Russian imperial family, and London, where he was received by Queen Victoria They then travelled by way of Norway and Sweden to Germany, visiting Prussia, Saxony and Austria, as well as many of the smaller German sovereignties After a short stay in Russia, the Rubinsteins settled in Berlin and remained there between 1844 and 1846. Anton received counterpoint and harmony lessons from Siegfried Dehn, whose teaching had been valuable for Glinka some years earlier, he also saw much of Felix Mendelssohn and Meyerbeer who, like the Rubinstein's, were of Jewish extraction His father died in 1846, and the family returned to Russia, but Anton spent the next two years in Vienna in great poverty, seeking out a living by giving piano lessons. On his return to Russia in winter 1848-1849, the Grand Duchess Yelena Pavlovna, sister in law of Nicholas, and formerly the Princess of Saxe-Altenhurg, took the urbane and amusing young man under her wing. He not only had an apartment in one of her palaces, but soon became what he jestingly called her 'musical stoker' and played at her soirees, often m the presence of the tsar and his immediate family.Anton Rubinstein's professional concert career began in 1854, when he toured Europe with enormous success. In winter 1856-1857 he stayed with the grand duchess in Nice, and it was during that time that they made sweeping plans for the improvement of musical education in Russia. In 1859 they founded the Russian Musical Society, whose concerts were conducted by Rubinstein, and in 1862 the St Petersburg Conservatory. Rubinstein was its director until 1867, when he resigned from both posts and made another triumphant tour through most of Europe. From 1871 to 1872 he was conductor of the Philharmonic Concerts in Vienna, one of his concerts, on December 11, 1871, included a performance of the first part of F. Liszt's Christus (with Bruckner playing the organ part) in the. presence of the composer. In 1872-1873 he toured the USA with Wieniawski, and for the next 15 years he was one of the most sought after pianists m the world. He also built up a considerable reputation as a conductor. In 1887 he again undertook the direction of the St Petersburg Conservatory and in 1889 his jubilee was lavishly celebrated. At his death he was an almost legendary figure as a pianist, and the Rubinstein legend continued well into the 20th century.When Anton Rubinstein and the Grand Duchess Yelena Pavlovna founded the Russian Musical Society (1859) and the St Petersburg Conservatory (1862), there were only a handful of notable Russian composers, the most important, besides Dargomïzhsky, being Balakirev and his nationalist circle which included Mussorgsky, Borodin and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov (Glinka had died in 1857). Balakirev was also a fine pianist, but there were few native.Russian instrumentalists and the orchestra of the Russian Musical Society consisted mainly of German musicians. By writing an article in the periodical Vek (1861, No. 1), which inveighed against Russian musical amateurism, Rubinstein was endeavoring to argue the case in educated circles for his conservatory; however, he succeeded in alienating Balakirev's group and their staunch advocate Vladimir Stasov, who replied in virulent terms that the establishment of a conservatory would result in 'volumes of worthless compositions'.Rubinstein had previously offended Glinka by writing an article against nationalism in music, alleging that the Russian national elements in his operas were unsuccessful {Blotter für Theater, Musik und Kunst, xxix, xxxiii, xxxvii, 1855). The nationalist composers were thus at daggers drawn with Rubinstein. Nevertheless, with the help of Anton, Nikolay Rubinstein founded the Moscow Conservatory, and by the end of the century Anton's vision of conservatories (and opera houses) all over Russia was to be realized, producing instrumentalists and singers of a higher quality than he could ever have foreseen. This greatly enhanced the social status of musicians, and when Anton resumed the directorship of the St Petersburg Conservatory in 1887 he again became a pre-eminent figure in Russian musical education, whose far-reaching ideas were to be the basis of music as it is still taught in Russia. Tchaikovsky was one of his earliest students.However, Anton Rubinstein's principal claim to international fame was as a pianist. As a young man he had admired F. Liszt, studying carefully his mannerisms on the concert platform. This admiration continued throughout the older man's life, and like F. Liszt's, Rubinstein's recitals were tremendous occasions. He was always very nervous beforehand, and his interpretations were not totally preordained; there was always an element of surprise. Such was his magnetism that he held his audiences in thrall, and they in turn formed an integral part of his music-making. Hanslick wrote ecstatically of Rubinstein's rendering of F. Chopin's Sonata No.2 in Bb minor, averring that there were no sentimental fluctuations of pace in his rubatos, nor was there any affectation in his playing, though its power was 'elemental'. Even Balakirev wrote to Tchaikovsky that 'he played exquisitely a Beethoven sonata (in C major) [the _Waldstein_] and pieces by F. Chopin'.Anton Rubinstein's stamina was astonishing. On his tour of the USA with Wieniawski he gave no less than 215 recitals between September 10, 1872 and May 24, 1873; the proceeds of the tour 'laid the foundations of my prosperity', he wrote in his autobiography. His repertory was enormous, as is shown by the series of seven 'historical' recitals given on a tour of Europe and Russia in the 1885-1886 season, ranging from Byrd, Bull, François Couperin and Rameau in the first recital to contemporary Russian composers in the last, with a selection of the music of most of the major composers, including Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach and Weber, in between. | |

| Work | |

| Anton Rubinstein composed assiduously during all periods of his life. He was able, and willing, to dash off for publication half a dozen songs or an album of piano pieces with all too fluent ease in the knowledge that his reputation would ensure a gratifying financial reward for the effort involved. But only the Melody in F, Op. 3 no.1 for solo piano achieved lasting popularity (testified to by the 12 pages of arrangements of this piece, for various instrumental and vocal combinations, in the catalogue of the British Library). Some of the songs achieve a certain distinction, and in his chamber music a movement here or there (such as the Scherzo from the String Quartet no.3) sometimes rises above the commonplace. But bhere and in his numerous attempts at large-scale works, there are, too often, signs of haste. As Paderewski was later to remark, 'He had not the necessary concentration of patience for a composer'. For example, good ideas in the Symphony no.2 ('Ocean') are developed in a trivial manner and this and other similar works reveal his fatal facility as a note-spinner. He was prone to indulge in grandiloquent clichés at moments of climax, preceded by over-lengthy rising sequences which were subsequently imitated by Tchaikovsky in his less inspired pieces.Together with an uninhibited use of the diminished 7th chord, these characteristics are lavishly displayed in all four piano sonatas. Only the second-movement Allegretto con moto, a charming little march-scherzo, from the Third Piano Sonata, Rubinstein's own favorite, is altogether free from padding and very considerable reliance upon Felix Mendelssohn and Robert Schumann; an instance of F. Chopin's influence is to be found in the scherzo of the Fourth Sonata, in which the rhythm is directly taken from the scherzo of F. Chopin's Bb minor sonata.His greatest success as a composer came in a brief middle period which started with the Fourth Piano Concerto in D minor (1864) and finished with the opera Demon ('The Demon', 1871, first performed in January 1875). Between these works are sandwiched two important orchestral works, Don Quixote, which Tchaikovsky thought was 'very interesting and well done' although 'episodic' in construction, and Ivan IV Grozniy, 'a wonderful piece' in Tchaikovsky's opinion; Tchaikovsky arranged both works for piano duet. Ivan IV Grozniy was given its first performance on 2/14 November 1869 by none other than Balakirev, who greatly admired it;Borodin commented that 'the music is good; you just cannot recognize that it is Rubinstein. There is nothing that is Mendelssohnian, nothing as he used to write formerly'. In this powerful, imaginative and perceptive evocation of Ivan's complicated personality, Rubinstein dexterously incorporates a number of contrasting themes into an atypically unconventional variant of sonata form, with a slow, magisterial, fully integrated introduction; the inevitable sequences and diminished 7ths are for once used effectively and convincingly. Nor does he indulge in bombastic orchestration: the scoring is for a standard orchestra with double woodwind plus piccolo, normal brass (including tuba), and only timpani in the percussion section. Ivan IV Grozniy did not achieve the huge success of Demon or the Fourth Piano Concerto, both of which retain a precarious foothold in the repertory today. Together with its predecessors, the Fourth Concerto (the full score of which was published in 1872 in a revised and improved version) greatly influenced Tchaikovsky's piano concertos, particularly the first (1874-1875), and the superb finale, with its introduction and scintillating principal subject, is the basis of very similar material at the beginning of the finale of Balakirev's Piano Concerto in Es major; this finale was written down after Balakirev's death in 1910 by his collaborator and friend Sergey Lyapunov, who had heard Balakirev play it many times. The first movement of Balakirev's concerto had been written, partially under the influence of Rubinstein's Second Concerto, in the 1860's.In the decade or so after 1875, Demon (The Demon'), with a libretto based on a well known Lermontov narrative poem, received no less than 100 performances, by the end of the century, with the exception of Glinka's A Life for the Tsar, it had outstripped in popularity all other operas, including those of Meyerbeer to which it is partially indebted Tchaikovsky considered that, in spire of 'much padding'. Demon contained 'lovely things', and it certainly influenced his opera Yergeny Onegin, which, like Demon is an opera in Three Acts, Seven Scenes' The delicate style of the Russian chamber romance which epitomizes the portrayal of Rubinstein's Tamara is echoed in Tchaikovsky's portrayal of Tat'yana In scene 3, Rubinstein's 'orientalisms' are as satisfactory as those employed in the later Symphony no 5 in G minor and the opera Kupets Kalashnikov ('The Merchant Kalashnikov') are unconvincing The part of the Demon himself is one of the finest in Russian opera, and was a favorite role of Chaliapin.The rest or Rubinstein's last output consists of other operas including Die Maccabaër, popular both in Germany and in Russia, sacred operas, six symphonies, including No. 2 (The Ocean), which he dedicated to F. Liszt, and with which he tinkered over a period of 29 years, finishing up with seven rather than the original four movements, violin and cello concertos, innumerable songs, chamber music including violin, viola and cello sonatas and, besides the piano sonatas, many other piano pieces. | |

|

|

| More Pictures | |

| Source: Mostly Maurice Abravanel WebsiteContributed by Aryeh Oron (July 2007) | |

| Anton Rubinstein: Short Biography | Piano Transcriptions: Works | Recordings |

| Links to other Sites | |

| Rubinstein Anton (Maurice Abravanel) Anton Rubinstein Biography (Naxos) Public Domain Music - Biographies: Anton G Rubinstein Anton Rubinstein (Marius van Paassen) | Anton Rubinstein (Wikipedia) [English] Anton Grigorjewitsch Rubinstein (Wikipedia) [German] Anton Rubinstein (Encyclopaedia Britannica) Anton Rubinstein (NNDB) |

| Bibliography | |

| Catherine Drinker Bowen: Free Artist (New York: Random House, 1939) David Brown: Tchaikovsky: The Early Years, 1840-1875 (New York: W.W. Norton & Comoany Inc., 1978) David Brown: Tchaikovsky: The Years of Wandering, 1878-1885 (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 1986) James Francis Cooke: Great Pianists on Piano Playing (Philadelphia: Theo Presser Co., 1913) Reginald R. Gerig: Great Pianists and Their Techniques (Newton, Abbot, David & Charles, 1976) Hanson and Hanson: Tchaikovsky: The Man Behind the Music (New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1965) Anthony Holden: Tchaikovsky: A Biography (New York: Random House, 1995) Barrie Martyn: Rachmaninov: Composer, Pianist, Conductor {Aldershot, England: Scolar Press, 1990) Alexander Poznansky: Tchaikovsky: The Quest for the Inner Man (New York, Schirmer Books, 1991) Oscar von Riesemann: Rachmaninoff's Recollections (London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd, 1934) Harvey Sachs: Virtuoso (New York: Thames and Hudson, 1982) Harold C. Schonberg: The Great Pianists (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1987, 1963) |