Russian manned space program strategy in 2010s (original) (raw)

Searching for details:

The author of this page will appreciate comments, corrections and imagery related to the subject. Please contact Anatoly Zak.

Related pages:

Cooperation with China on the lunar base

TsSKB Progress' super-heavy launchers

Russian airlock for Deep Space Gateway

Russian human space flight in the 2010s

A broad look at strategies and directions of the Russian piloted space program from 2010 to 2020.

Previous chapter: Russian space program during 2010s

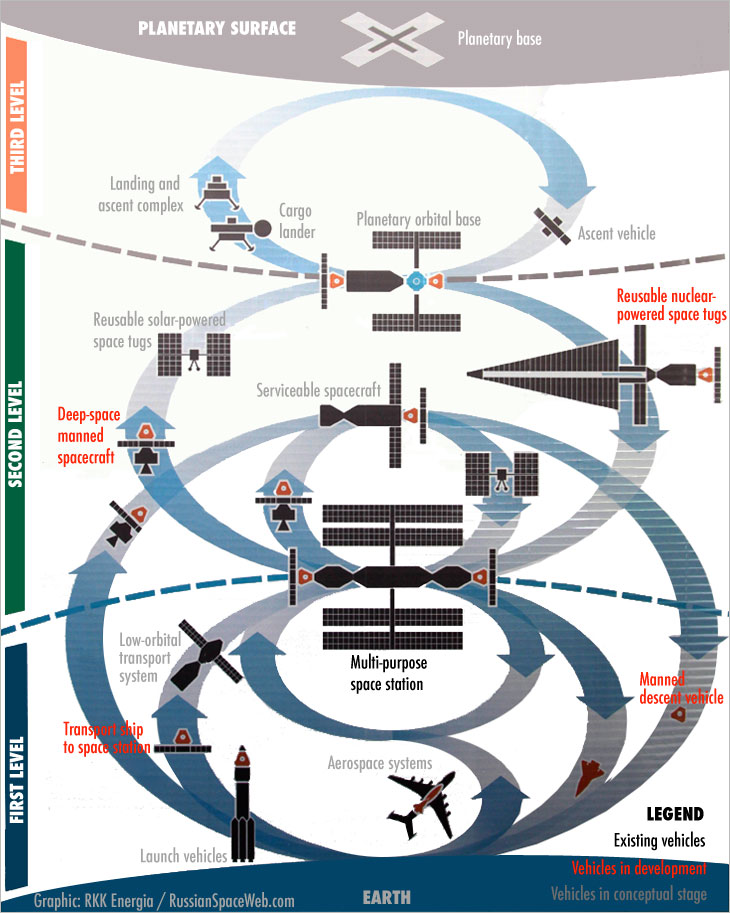

The Russian strategy in piloted space flight and the status of its major components as of 2013. (Clickable)

Continuing a tradition started in 2009, the Russian space agency, Roskosmos, used a Moscow air and space show, MAKS-2013, in August, to present a broad outline of its strategy for human space exploration. This time, a roadmap extending three decades into the future appeared in the form of an oversized poster strung like a sail above a crew module of the next-generation spacecraft. It illustrated an already familiar scenario of expanding human exploration from the International Space Station, ISS, to a habitable outpost at one of the Lagrangian points near the Moon. The itinerary would then split into two possible routes: one leading to the Moon and followed by visits to asteroids at the turn of the 2030s and another -- heading to the same destinations but in a reverse order. Both routes would ultimately lead to Mars around 2040.

Despite this two-option concept having been on the table since at least 2011, Russia and its key partners in piloted space flight failed to single out a joint project. In August 2013, Russian officials said that NASA had been reluctant to lead a big international space venture and Roskosmos could only hope to reach an agreement on any strategy in 2014.

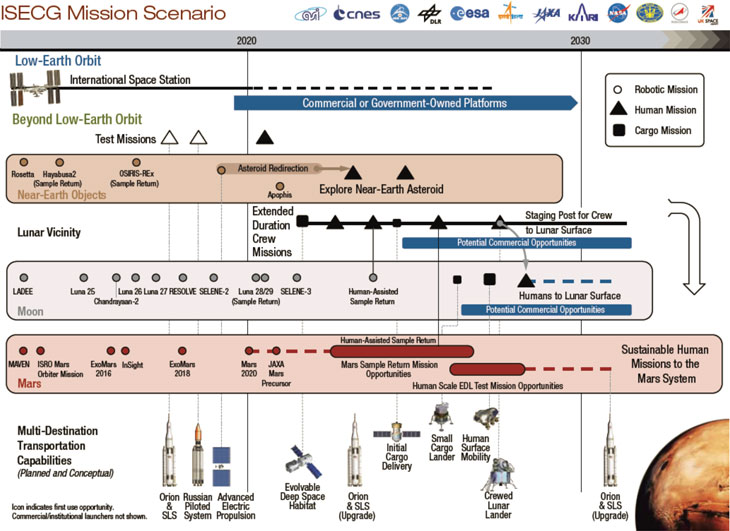

According to US officials, NASA had many reservations about getting into another complex and costly project with Russia. In addition to a rocky ride during the development of the ISS in the past two decades, the overall atmosphere of US-Russian relations was now clouded with deep divisions over major geopolitical issues, such as Syria and Iran. As a result, both sides were chartering "going alone" strategies in piloted space flight, while continuing snail-pace consultations on a potential joint program within the International Space Exploration Coordination Group, ISECG. This group was officially established in 2007 and by 2013 involved 14 space agencies.

Items on the menu

At MAKS-2013, Roskosmos presented a "wish list" of spacecraft and hardware to achieve its ambitious goals in space. The most immediate items on the agenda included three new modules designed to dramatically expand the Russian segment of the ISS. As of 2013, the 20-ton Multi-purpose Laboratory Module, MLM, was scheduled for launch in 2014, followed by the Node Module, UM, within a year. The Node Module could also serve as the basis for a large airlock studied by the agency's key piloted space flight contractor -- RKK Energia.

The development of the first in the pair of planned Science and Power Modules, NEM-1, had also started. Sporting a drastically new architecture, NEM-1 would house a state-of-the-art science lab and provide the Russian segment with an independent source of power. That feature could become critical if Roskosmos was ever to fulfill its promise to split the Russian segment from the rest of the ISS at the end of the station's service life in 2022-2028. In 2013, Russian space officials still maintained that the newest modules of the Russian segment could eventually become the nucleus of the next-generation outpost in the Earth orbit within the OPSEK project, later renamed the Russian Orbital Station, ROS.

Finally, RKK Energia was also studying an experimental inflatable module, which if funded, could also be added to the Russian ISS segment or to a future space station.

Going to Lagrange?

By the beginning of 2012, a man-tended platform at a Lagrange point was endorsed by the head of the Russian space agency as a stepping stone to the Moon. To reach both destinations, Russia would have to develop a piloted transport spacecraft capable of flying beyond the Earth orbit. As a result, in the spring of 2012, Roskosmos urgently ordered RKK Energia -- to re-tailor its all-but-ready design of the next-generation spacecraft, PTK NP, for deep-space missions.

In addition, a super-heavy launch vehicle with a payload of 70 tons would be required for sending PTK NP into deep space. During 2012 and 2013, the Russian space industry made several proposals for such a rocket within Sodruzhestvo, Energia-5K and STK projects, and Roskosmos promised to start a formal competition to choose a winning architecture for the giant rocket within months.

To build a launcher with a payload of 80-tons to low Earth's orbit by 2028 would require 700 billion rubles with a possible 30 percent increase based on previous experience with programs of this scale. The production plant in Vostochny would probably be required as well.

Mars receding

During 2010s, prospects for human mission to Mars, that had been 20 years away for much of the Space Age, now receded ever farther. In August 2011, Nikolai Panichkin, a deputy head of TsNIIMash research institute, told journalists that planners from his organization, traditionally responsible for Russia's long-term planning in space, had scheduled an expedition to Mars in 2040 or 2045, thus pushing this milestone as far as 34 years away. At the same time, a lunar landing was not expected before 2030. Still, Russian officials at RKK Energia insisted that Mars had remained the ultimate goal of the Russian space program in the next half a century.

In April 2013, the head of Roskosmos Vladimir Popovkin told the official newspaper of the Russian Duma (parliament) that the agency's latest conceptual designs envisioned assembling a 450-ton Mars-bound expeditionary complex out of four or five components with a mass ranging from 90 to 112 tons and delivered to the low Earth orbit by future super-heavy launchers. In addition to record-breaking payload capabilities, these powerful rockets could be propelled by winged first-stage boosters, which would fly back to Earth and land on a runway like an aircraft. At the MAKS-2013 air show, Russia's prime aviation research center, TsAGI, demonstrated two scaled prototypes of fly-back boosters, which had already gone through the rigors of wind tunnel testing.

As an even more significant step toward making the mission to Mars possible, Moscow-based Keldysh research center claimed major progress at MAKS-2013 in the development of a nuclear-powered and electrically propelled space tug. The project, first approved by then Russian President Dmitry Medvedev in 2009, would revolutionize space travel, enabling long-haul ferry flights around the Solar System for very large payloads, including habitable modules.

Russia's lost chance at the Moon

In 2014, on the wave of the successful Sochi Olympics and with a growing economy, Roskosmos advertised ambitious space exploration plans focused on the Moon. At the time, proponents of lunar exploration hoped it could become another national flagship project after Sochi. Behind the scene, public pronouncements relied on several studies that grew into a multi-year engineering effort to develop lunar exploration systems. The work continued into the early 2020s and left a considerable even if little known design legacy.

Russian cooperation with its ISS partners

On January 28, 2014, speaking at the Korolev Memorial Symposium in Moscow, the head of Roskosmos Oleg Ostapenko energetically reconfirmed the strong Russian interest in cooperation with NASA on piloted missions to asteroids, as well as expeditions to the Moon and to Mars. "I am confident that we can resolve all the challenges (of such missions) at much larger scale than other countries and I don't have a slightest doubt about it," Ostapenko said, "What's important is to concentrate our efforts correctly."

It was unclear, whether this was a message directed at NASA or at the Russian government or at both. In any case, this optimism looked completely unfounded just weeks later in the wake of Russian Anschluss of Crimea, followed by a bloody conflict in Ukraine.

International cis-lunar station

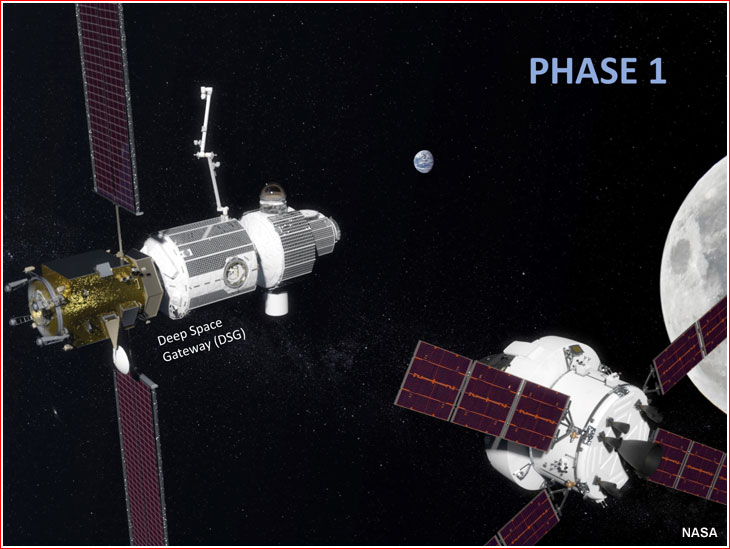

Despite the politics, in November 2014, the heads of agencies involved in the ISS program agreed to begin a joint study of a possible cooperative project which would lead human space missions into deep space. The effort centered on a NASA-led man-tended platform in the cis-lunar space, which could be used as a "proving ground" for US missions to Mars and as a way station for the exploration of the Moon by other partners.

During 2016, the international team made significant progress in formulating the final architecture and the assembly schedule of the cis-lunar outpost, which could lead to full-scale development in 2017 or 2018. However, unlike all other partners, Roskosmos remained uncommitted about its contribution into the program besides a small airlock module and provisional flights of the PTK/Federatsiya spacecraft beginning in 2027.

The agency's own strategic resarch arm, TsNIIMash, concluded that a direct flight to the Moon would be a simpler, cheaper option than building a cooperative cis-lunar platform. That is despite the fact that Russia's own independent efforts to go beyond low Earth orbit has been hitting one obstacle after the other in the mid-2010s. The Russian next-generation spacecraft capable of deep-space missions still remained largely on paper with its first launch delayed from 2018 to 2023 or 2024, at the earliest.

Also in 2016, after a year-long study, the six-launch lunar expedition scenario based on the Angara-5V rocket was deemed to be unworkable, while the funding for the super-heavy launcher, which could dispatch the lunar expedition in a single shot, was not expected to come around until the second half of 2020s. Whether the overall political situation played any role Roskosmos' reluctance to cooperate with NASA remained unclear.

Downsizing and delaying the program during mid-2010s

In December 2014, a group of officials lead by Yuri Koptev from the United Rocket and Space Corporation, ORKK, began another review of the piloted space efforts, including the proposals for a super-heavy rocket. The review has continued within the Scientific and Technical Council, NTS, at Roskosmos after restructuring of the agency into the State Corporation in January 2015. (744)

Critics noted that the piloted program expenditure exceeded 50 percent of the agency's budget. By taking obligations on the piloted space flight, everything else had to be of a secondary importance, critics charged.

As of 2016, the Moon still remained the ultimate goal of the Russian space program. However, according to industry sources, there were serious doubts about Roskosmos' ability to fund both the piloted lunar program and the development of the Russian orbital station to succeed the ISS. As of the end of 2016, the lunar exploration effort still retained its highest priority status as mandated by the Kremlin in 2013 during the high time for oil prices.

Up to six billion rubles were reportedly spent on the Russian lunar program as of September 2017, Roskosmos sources said.

Russian cosmonauts to stay in Baikonur for the time being

On May 22, 2017, President Putin endorsed a politically sensitive proposal from Roskosmos to base the next-generation piloted spacecraft, PTK Federatsiya, in Baikonur rather than in Vostochny, at least for the ship's initial launches which would now switch from Angara-5P to the yet-to-be developed Soyuz-5 rocket. All piloted missions from Vostochny were deferred until the arrival of the superheavy rocket, which was not expected for at least a decade. That plan would allow the Russian government to slash funding for the 10-year-long cosmodrome development program, which was approved in 2017 after several delays. By Sept. 13, 2017, Roskosmos received the final draft of a government decree approving that strategy.

Russia to support ISS extension, jumps on cis-lunar bandwagon!

By August 2017, Roskosmos also decided to reexamine once again, the level of its engagement in the cis-lunar station project. The State Corporation re-staffed its team at the consultations of the ISS Exploration Capabilities Study Team, IECST, which was working on various technical aspects of the program. At the latest meeting of the team, Roskosmos officials were jointed by experts from the TsNIIMash research institute, Russia's leading evaluation and certification center in space technology, and from RKK Energia, the nation's prime contractor in human space flight.

In 2017, publicly released NASA renderings of the cis-lunar station depicted a "notional" design of the airlock (center), instead of the Russian-built airlock module, which had been studied for that role by the ISS partners at the time.

At the time, the Russian team did not present any new proposals, but the Russian-built airlock module remained on the table as an option, even though, contemporary NASA's renderings of the cis-lunar outpost were depicting a notional US-based design of the airlock that had no real engineering foundation behind it.

Also, in the middle of August, the head of Roskosmos Igor Komarov hosted a meeting of Russian space officials on the nation's future strategy for the piloted space program. The gathering was expected to work on a crucial plan to extend the life of the International Space Station, ISS, until 2028 from the currently planned deadline of 2024. At the same time, the meeting reportedly also considered Russian options for the participation in the NASA-led cis-lunar project and, possibly, reviewed a concept of the Russian Earth-orbiting space station, ROS, intended to succeed the ISS. By that time, the TsNIIMash research institute estimated that the funding of the ROS in parallel with the lunar program would not be possible. As a result, Roskosmos made a decision to side with the cis-lunar station project led by NASA.

However, as US-Russian relations continued to deteriorate at the end of 2017 and the beginning of 2018, Roskosmos began considering alternative scenarios to cooperation with the US, including the possibility of joining a Chinese space station slated for orbital assembly during the 2020s. In April 2018, Head of Roskosmos Igor Komarov abruptly cancelled his visit to the 34th Space Symposium in Colorado Springs, reportedly as a result of the latest US sanctions against Russia. Russian cosmonaut Sergei Krikalev, currently leading the development of the Russian human space flight strategy, represented Roskosmos at the Space Symposium, which saw the participation of heads of other space agencies.

Russia considers cooperation with China in human space flight

The worsening of the Russian-Western relations in the mid-2010s, prompted Moscow to consider new strategies in human space flight, independent of the existing partnerships with NASA and Europe. Because the "going alone" strategy could be too expensive, the Russian government looked at a potential partnership with the only other country pursuing a full-fledged human space effort -- China.

Rogozin's stance: Will US-Russian cooperation continue?

Deputy Prime Minister Yuri Borisov (center) visits Control and Test Station, KIS, at RKK Energia on Aug. 31, 2018. He is accompanied (right to left): Roskosmos head Dmitry Rogozin, Director General at RKK Energia Sergei Romanov, a former cosmonaut Sergei Krikalev and Acting Deputy Director at Roskosmos Nikolai Sevastyanov.

The appointment of the controversial former Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Rogozin to lead Roskosmos, raised new concerns about the prospects of the US-Russian cooperation. Rogozin famously proposed NASA to use a trampoline to get its astronauts to the ISS, when the US-Russian cooperation came under a serious strain in the wake of the Crimean invasion. However, during his first interaction with foreign partners in the new capacity of the Roskosmos head, Rogozin apparently took a friendly stance. Top managers from NASA, the European Space Agency, ESA, and the German Space Agency, DLR, met Rogozin in Baikonur for the launch of the Soyuz MS-09 spacecraft to the ISS on June 6, 2018. The group included NASA's Associate Administrator for Human Exploration and Operations William Gerstenmaier and the Director General of the European Space Agency, ESA, Johann-Dietrich Wörner.

Two days later, Roskosmos issued a statement declaring Rogozin's principal committment to a broad international cooperation in space. The press-release specifically singled out the development of the joint lunar orbital station, LOP-G, as a platform for the human exploration of Mars and for the eventual creation of lunar infrastructure.

On June 24, 2018, in an interview with the official RT TV channel, Rogozin once again reiterated the desire of Roskosmos to continue cooperation with the US in human space flight, including the joint exploration of the Moon. He cited technical risks associated with lunar missions as a reason to preserve the US-Russian ties.

On Sept. 12, 2018, Deputy Prime Minister Yuri Borisov, recently appointed to oversee the defense and space industry, also echoed the Russian interest to cooperate with other countries in the exploration of the Moon.

However, in January 2019, NASA had to cancel planned Rogozin's visit to the US due to pressure from the members of Congress.

Planning activities in 2018 for human expeditions to the Moon

During 2018, space officials in Russia and the US accelerated work on gathering political support, lining up funding and engineering efforts for preparing the return of humans to the surface of the Moon.

Russian space leaders to discuss cooperation with US on the Moon

At the start of 2019, captains of the Russian space industry were gearing up for a major summit to form the national strategy toward cooperation with the United States on human lunar missions. A series of high-level meetings aimed to resolve a number of political, financial and technical questions facing Roskosmos as it tried to calibrate its program relative to NASA's own effort to explore the Moon.

Can Russia and China take over the Moon?

In July 2020, Head of Roskosmos Dmitry Rogozin touted plans for a Russian-Chinese base on the Moon. But is there really anything behind the talk and what are the prospects for an ambitions Russo-Chinese space exploration program?

Roskosmos begins planning for 2040

On October 7, 2019, Roskosmos issued State Contract No. 851-0923A/19/140 to its prime research organization AO TsNIIMash to organize systemic studies for justification and implementation of development programs in human space flight. The study, that had to explore prospects for the human space flight strategy in Russian extending as far as 2040, was code-named Avangard (Pilot-1). In the following year, TsNIIMash sub-contracted the core of this work to RKK Energia.

In 2021, top Roskosmos officials and engineers continued a multi-prong effort seeking new directions for the nation's human space flight after the retirement of the International Space Station, ISS. At least two major strategies along with multiple secondary options are on the table, including early exit from the ISS.

Work continues to formulate Russian post-ISS strategy

In 2022, financial and technical uncertainty surrounded Roskosmos' evolving long-term plans for piloted missions.

Read more on the subject at:

An overview of Russia's major research and development projects in piloted spacecraft during 2010s:

| Project | Development start | Original launch date | Current launch date | Cost | Status, notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIM1 | 2006 (?) | 2010 | 2010 | - | Launched, operational |

| MLM | 1999 | 2007 | 2017 | - | In development; (376) delayed to 2014 |

| Node Module (UM) | 2009 | 2013 | 2018 | - | In development |

| NEM-1 (575GK) | 2009 | 2014 | 2019 | - | Full-scale development started in 2012 (376) |

| NEM-2 | 2010 | 2015 | ? | - | Concept evaluation (376) |

| OKA-T-MKS (52KS) | 2006 | 2012-2015 (378) | End of 2018 | R2.82 billion | Preliminary development (cost for 2006-2014) |

| Vozvrat MKA | 2009 | 2016 | - | R860 million | (beginning in 2009(?) |

| PTK NP | 2009 | 2015 | 2021 | - | In development |

| TGKS (Parom) | ? | 2009 | 2015 | - | Preliminary development (376) |

| OPSEK/VShOS/ROS | ? | 2020 | 2024 | - | Concept evaluation (376) |

| OPSEK core module | 2015 | 2020 | - | - | Concept evaluation (376) |

| NEM-1 heavy | 2024 | 2029 | - | - | Concept evaluation (376) |

| NEM-2 heavy | 2025 | 2030 | - | - | Concept evaluation (376) |

| Lunar base | 2016 | 2025 | 2030 | $50 billion (377) | Concept evaluation (376) |

| Expedition to Mars | 2013 | 2021 | - | - | Concept evaluation (376) |

| Soyuz MS (upgrade program) | 2010 | 2011-2012 | 2016 | - | In flight testing |

| New-generation cargo ship, TGK PG | - | - | - | - | - |

| Airlock for the international cis-lunar platform | - | - | - | - | - |

Pros and cons of possible goals and destinations in piloted space flight:

| Goal or destination | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Maintaining the International Space Station | Enables largely flat budgets | Can hardly be justified with onboard science; faces end of service life by mid-2020s |

| Building a man-tended platform in the Earth orbit | Enables to cut budget (?) | Dead-end strategy which can hardly be justified with onboard science |

| Missions to asteroids | Flexible and potentially affordable (?) goal, providing experience for further piloted missions | Can be accomplished more effectively with unpiloted spacecraft |

| Lunar Orbital Station | Might be achievable with projected budgets and international participation | Makes little sense without a lunar exploration program to follow |

| A men-tended platform at the lunar Lagrange point | Might be achievable with projected budgets and international participation | Makes little sense without a lunar exploration program to follow |

| Lunar base | An ambitious, long-term goal | Might be unaffordable under current budgets and without a broad international agreement to share costs |

| Expedition to Mars | An ambitious, long-term goal | Unaffordable under current budget and without a broad international agreement to share costs |

Estimated annual funding required for an ambitious cooperative piloted project (as of beginning of 2012):

| Contributor | Percentage | Amount |

|---|---|---|

| USA (NASA) | 37 percent | $1.5 billion |

| Russia (Roskosmos) | 22 percent | $0.9 billion |

| Europe (ESA) | 16 percent | $0.6 billion |

| Japan (JAXA) | 10 percent | $0.4 billion |

| Canada (CSA) | 5 percent | $0.2 billion |

| Others (possibly Brazil, India, South Korea) | 10 percent | $0.4 billion |

| Total | 100 percent | $4.0 billion |

Next chapter: Russian human space flight program in 2020 (INSIDER CONTENT)

Story, illustrations and photography by Anatoly Zak; Last update:June 14, 2024

Page editor: Alain Chabot; Edits: October 1, 2013; November 10, 2016; August 8, 2017; June 25, 2018

All rights reserved

By 2011, NASA and its partners in the International Space Station program formulated several scenarios for the future of piloted space flight. Click to enlarge. Credit: NASA

A timeline of piloted space program unveiled at MAKS-2011 air show pushed possible expedition to Mars to 2040s. Click to enlarge. Copyright © 2011 Anatoly Zak

All roads lead to Mars... in 2040, originating at Lagrange points as early as 2022, according to a poster strung at the Roskosmos pavilion at the MAKS-2013 air and space show. Click to enlarge. Copyright © 2013 Anatoly Zak

Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Rogozin (left) and Roskosmos head Igor Komarov (center) demonstrate President Putin scale models of the Angara-5 rocket and the descent module of the next-generation piloted spacecraft, PTK NP, on April 13, 2015. Click to enlarge. Credit: Russian government

In 2015, joint groups from RKK Energia and Boeing formulated several concepts of a man-tended habitable platform in the lunar orbit. Click to enlarge. Copyright © 2016 Anatoly Zak

Circa 2015 concept of a near-lunar station assembled of Russian-built modules delivered as piggyback payloads on NASA's Orion/SLS system. Click to enlarge. Copyright © 2016 Anatoly Zak

Likely configurations for a fully assembled, low-cost successor to the ISS proposed by the Russian space industry in 2014. The facility includes the MLM module (top), a Node Module (center), an Inflatable Habitat (left), a Soyuz spacecraft (background); Docking and Airlock Compartment (right) and the Oka-T free-flying laboratory (bottom). Copyright © 2014 Anatoly Zak

As the first significant step toward achieving the mission to Mars, the Russian government approved the development of a nuclear-powered, electrically propelled space tug at the turn of 2010s. Copyright © 2013 Anatoly Zak

A scale model of a fly-back booster that was tested in wind tunnels of the TsAGI research institute in Zhukovsky, near Moscow. Copyright © 2013 Anatoly Zak

A lunar lander conceptualized during 2015 to be compatible with the Angara-5V rocket. Click to enlarge. Copyright © 2016 Anatoly Zak

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)