Myths of Crete and Pre-Hellenic Europe: Chapter VII. Races and Myths of Neolithic Crete (original) (raw)

Sacred Texts Classics Index Previous Next

Myths of Crete and Pre-Hellenic Europe, by Donald A. Mackenzie, [1917], at sacred-texts.com

p. 143

Races and Myths of Neolithic Crete

The Cave--dwellers of Crete--Azilian Stage of Culture--The Neolithic Folk--Obsidian obtained from Melos--Neolithic Finds at Knossos and Phæstos--Island inhabited at 10,000 B.C.--Settlers of the Mediterranean Race--The Evidence of Early Egyptian Graves--Migrations from North Africa into Europe--Appearance of Anatolians in Crete--The Agriculturists and Bearded Pastoralists--Racial Religious Beliefs in Scotland and Greece--The Various Cults of Zeus--Political Significance of Zeus Worship--Legend of the Cretan Zeus--the Tomb of the God--Traditional Holy Places appropriated by Early Christians--Cretan Zeus like Osiris, Adonis, Tammuz, Attis, and other Young Gods--Kings as Incarnations of Deities--Egyptian and Greek Mysticism--Demeter and Dionysus--Totemic Animals Tabooed--Pig Sacred in Egypt and Crete--The Sacred Goat--Bull Cult of Knossos--Links between Libya and Crete--The Double--axe Symbol--Maltese Story of "Axe Land"--Etymology and Labyrinth--Neolithic Houses in Crete--Survival of Palæolithic Traditions and Customs and Types--Religious Borrowing.

WHO were the earliest inhabitants of Crete and whence came they? The problem is involved in obscurity, but certain suggestive facts may be stated which throw some light upon it. As already indicated (Chapter III) no bones of Palæolithic man have been discovered on the island. Signor Taramelli, an Italian excavator, recently explored, however, the interesting grotto of Miamu, which was inhabited by early settlers who appear to have been either in the Late Magdelenian or the Azillan stage of culture. The deposit of the partly artificial cave yielded on examination a number of bone heads of weapons and bone spatulas, somewhat like the "spoon-shaped celts"

p. 144

of the Swiss lake-dwellings and the Rhone valley, which were probably utilized by huntsmen for scooping out marrow from the bones of roasted animals. Evidently, therefore, Crete had been occupied at a remote period by cave-dwellers. The lower grotto deposit was overlaid by Bronze Age remains.

During the long interval which followed the last glacial epoch, there was a gradual and general subsidence of land round the Mediterranean as elsewhere. But after Crete had become detached from Greece, it still remained for a period of uncertain duration connected with Asia Minor, where there were, no doubt, communities of cave-dwellers as in Phœnicia and Palestine. These ancient folks of the Cretan grotto of Miamu may have been isolated from their congeners on the mainland like the "beachcombers" of the "kitchen middens" in England and Scotland. We cannot say whether they became extinct or not. It is possible that the seafaring pioneers of the Neolithic Age found inhabitants on the island.

The earliest traces of the Neolithic folk have been discovered in the vicinity of the mountain village of Magasa. Among the relics were polished stone axes, numerous bone awls, and fragments of coarse pottery belonging to a similar stage of culture to that which obtained among the Neolithic cave-dwellers of Gezer, Palestine, who, as has been indicated, made pottery also. Apparently the Magasa settlers came from the north in their many-oared galleys, resembling those depicted on the painted pre-Dynastic pottery of Egypt. As much is indicated by the finds of obsidian flakes, Neolithic man, it may be explained, not only constructed knives, saws, arrow-heads, and other small implements from flint found in chalk deposits, and chert nodules embedded in limestone, but also from obsidian, which is the "glassy" variety of

p. 145

volcanic rock-hardened lava--known as liparite, 1 the "frothy" variety being "pumice-stone". Now, there is no obsidian in Crete. The only source of it in the Ægean is the Island of Melos (now Milos, or Milo), where the famous statue of Venus de Milo was discovered. Evidently an early Neolithic civilization had local development in the Cyclades, amidst

the sprinkled isles,

Lily on lily, that o'erlace the sea,

And laugh their pride when the light wave lisps "Greece". 2

Obsidian artifacts have been found in various islands of the Ægean, as well as on the mainland at Mycenæ and elsewhere, on the island of Cyprus, and as far westward as Malta, where it was imported, apparently from Melos, to be worked, for flakes as well as knives have been found, and also in Sicily. Schliemann discovered knives and flakes of obsidian in "the four lowest prehistoric cities at Hissarlik". He remarked regarding them at the time: "All are two-edged, and some are so sharp that one might shave with them". 3 The Jews still use flint and obsidian knives in religious ceremonies. Obsidian implements have also been taken from Neolithic strata near Nineveh. In Egypt, during the Old Kingdom Period, the beaten-copper statues of Pepi I and his son were given eyes of obsidian.

When Knossos and Phæstos were first selected as settlements, the Cretans had advanced into the later stage of Neolithic culture. Their obsidian knives were finely wrought, and have been found associated with serpentine maces, axes of diorite and other hard stone, and, as it is of special interest to note, clay and stone spindle whorls, indicating that the art of spinning was well known.

p. 146

It has been stated that the beginning of the Neolithic Age has been dated approximately 103000 B.C. The calculation has been arrived at by the comparative study of the stratified deposit at Knossos. The layers of the historic period are about 18 feet deep. Below these are the Neolithic layers, through which a depth of about 20 feet has been reached. Roughly about 3 feet was accumulated every thousand years. Allowing for variation in the deposits, the minimum date 10,000 B.C. appears to be safe; even 12,000 B.C. or 13,000 B.C. is possible. There is no trace in the first layer of a culture so low as that of Magasa. The earliest "folk-wave" which reached Knossos came with a form of culture which had been developed elsewhere.

Unfortunately no human remains have been unearthed in the Neolithic deposit to afford evidence regarding the racial affinities of these pioneers of civilization. Ethnologists are of opinion that they were representations of the Mediterranean race, and arrive at their conclusion on the following grounds: The large majority of the skulls found in Bronze Age graves are long, and are similar to those taken from Neolithic graves in Greece and elsewhere throughout Europe, especially in the south and west, as well as those from the pre-Dynastic graves of Egypt. The average stature of the Minoan Cretans was about 5 feet 4. inches. In the early Bronze Age there was a broad-headed minority.

It has been found that, as Dr. Collignon says, "when a race is well seated in a region, fixed to the soil by agriculture, acclimatized by natural selection, and sufficiently dense, it opposes an enormous resistance to absorption by the new-comers, whoever they may be". This view finds conspicuous support in the permanence of the Cro-Magnon type of mankind in the Dordogne

p. 147

valley. An interval of at least 20,000 years has not altered particular skull and face forms there. In Egypt at the present day the fellaheen resemble to a marked degree their Neolithic ancestors. Ethnologists explain in this connection that physical characteristics are controlled by the females of a community. Intrusions of males as traders, settlers, or conquerors may have been productive of variations, but the tendency to revert to the original type has operated to a marked degree, the "unfits" being eliminated by local diseases from generation to generation. In those districts, however, where settlers of alien type were accompanied by their wives and families, ethnic changes have been more pronounced. It is not surprising to find, in this connection, that in a country like Great Britain primitive types should be found to be still persistent. The majority of the invaders who crossed the seas were evidently males.

Since Sergi first roused a storm of criticism by advancing his theory of the North African origin of the Mediterranean race, a considerable mass of data has been accumulated which tends to confirm his conclusions. Egypt has provided evidence which sets beyond dispute the fact that once a racial type had been fixed it persisted for many thousands of years with little or no change. The problem as to why some heads are long and some are broad still remains obscure. All that can be said is that certain peoples developed in isolation during untold ages their peculiar physical characteristics, which changes of food and location have failed to alter.

Numerous graves were found during recent years in Upper Egypt in which the bodies have been preserved for a space of at least sixty centuries--"not the mere bones only", says Professor Elliot Smith, "but also the skin and hair, the muscles and organs of the body; and

p. 148

even such delicate tissues as the nerves and brain, and, most marvellous of all, the lens of the eye. "Thus", he adds, "we are able to form a very precise idea of the structure of the proto-Egyptian." This distinguished ethnologist's description of the early inhabitant of the Nile valley is of special interest: "The proto-Egyptian was a man of small stature, his mean height" was "a little under 5 feet 5 inches in the flesh for men, and almost 5 feet in the case of women. . . . He was of very slender build, for his bones are singularly slight and free from pronounced roughness and projecting bosses that indicate great muscular development. In fact, there is a suggestion of effeminate grace and frailty about his bones. . . . Like all his kinsmen of the Mediterranean group of peoples, the proto-Egyptian, when free from alien admixture, had a very scanty endowment of beard and almost no moustache. On neither lip were there ever more than a few sparsely scattered hairs, and in most cases also the cheeks were equally scantily equipped. But there was always a short tuft of beard under the chin." The burial customs and the ceramic and other remains of the Mediterranean peoples were of similar character everywhere. 1

In some pre-Dynastic Egyptian graves the dead were wrapped in "flaxen cloth of considerable fineness". It is probable, therefore, that the spindle whorls found in Crete were invented in Egypt. The brunette complexion of the Mediterranean Neolithic folk was probably acquired on the North African coast whence they spread into Europe. As ships were depicted on Egyptian pre-Dynastic pottery, it is possible that companies of them crossed the Mediterranean Sea. The great majority entered Europe, however, across the Straits of Gibraltar, and by the Palestine

p. 149

and Asia Minor route, along the ancient "way of the Philistines".

The stomachs of some of the naturally mummified bodies have been taken out, and when their undigested contents were submitted to examination) discovery was made, among other things, of fish bone and scales, fragments of mammalian bones, remains of plants used as drugs, and husks of barley and millet. The Mediterranean folks who remained in Egypt were evidently agriculturists, stock-breeders and fishermen, and non-vegetarians.

A people who had adopted the agricultural mode of life were able to occupy more limited areas than huntsmen or pastoralists. Europe must have been thinly populated at the dawn of the Neolithic Age, when the Mediterranean peoples began to "peg out claims" in its valleys, round its shores, and on green inviting islands. The Cretan pioneers were undoubtedly agriculturists. They grew peas and barley, and ground their meal in stone mortars and querns; they fenced their land, and must therefore have had land laws; and they kept herds of sheep, cattle, pigs, and goats. The fig- and olive-trees were also cultivated. In short, they had imported to Crete the agricultural and horticultural civilization which the Egyptians credited to Osiris and Isis, before they had begun to carry on a sea trade with the home country. Evidence has also been forthcoming that the Neolithic peoples of western Europe and the British Isles were similarly agriculturists. Sometimes the teeth taken from graves are found to be in a ground-down condition. This was partly due to the deposit of grit in limestone and sandstone mortars and querns, which mixed with the meal. 1 The Neolithic folk who utilized soft stones for milling must have been as

p. 150

familiar as some of their modern descendants with the agonies of toothache and indigestion.

The minority of broad-heads in the early Minoan period in Crete may have been survivals from Palæolithic times, or the descendants of slaves. It is more probable, however, that they represented an infusion of traders and artisans from Asia Minor. Professor Elliot Smith, who believes that the Egyptians were the first to work copper, suggests that "the broad-headed, long-bearded Asiatics", of Alpine or Armenoid type, "learned of its usefulness by contact with the Egyptians in Syria", and passed on their acquired knowledge to other peoples. Referring to Crete in particular he says: "We can have no doubt these people (the Armenoids) began to make their way into Crete, from Anatolia perhaps, at the time when the diffusion of the knowledge of copper was beginning". 1 At a much later period the artisans of North Syria and Anatolia were famous as metal-workers. One of the results of the wars waged by Egypt, after the expulsion of the Hyksos, was the introduction to the Nile valley of coats of mail, gilded chariots, gold and silver vases, and other articles which were greatly prized. "At this period", writes Professor Flinders Petrie, "the civilization of Syria was equal or superior to that of Egypt. . . . Here was luxury far beyond that of the Egyptians, and technical work which could teach them, rather than be taught." 2 Many thousands of prisoners were also taken, and, when tribute was arranged for, the Pharaoh made it a condition that his vassals should send "the foreign workmen" with it. Kings and noblemen also received wives from Syria and Anatolia. During the Eighteenth Dynasty the typical Egyptian face, as a result, underwent a change. The upper and artisan classes became half foreigners. As at

p. 151

the present day, however, the peasants were unaffected by the alien infusion, and they constituted the large majority of the inhabitants.

The broad-heads represent an ancient stock which had an area of characterization somewhere in Central Asia. They were apparently separated, during the Late Glacial and Inter-glacial Periods, for many thousands of years from the fair northerners and the brunette Mediterraneans--long enough, at any rate, to develop distinctive physical characteristics, and also, it would appear, distinctive modes of thought. They were mainly a pastoral people, and clung to an upland habitat along the grassy steppes. In contrast to the lithe and slight agriculturists from North Africa, they were heavily bearded and muscular; they also included short and tall stocks. During the Neolithic Period these broad-heads were filtering into Europe, but it was not until the early Copper Age that their western migrations assumed greatest volume.

Evidence as to the source of early Cretan culture and the homeland of the pioneer settlers may be obtained, not only by studying physical characteristics, but also early religious beliefs. There is nothing so persistent as "immemorial modes of thought". At the present day it is possible to find, even in these islands, small communities descended from alien settlers, who have for long centuries lived beside and never mixed with the descendants of the aborigines. Round the east coast of Scotland, for instance, the fisher-folks in not a few of the small towns are endogamous-they rarely marry outside their own kindred; and they not only speak a different dialect from their neighbours, but have different superstitions. So distinctive, too, are their physical traits that they are easily distinguished in certain localities.

In ancient times peoples of different origin lived more

p. 152

strictly apart than is the case nowadays. Herodotus and other Greek writers sought for clues as to tribal origins by making reference to burial customs and religious beliefs.

The Carians maintain they are the aboriginal inhabitants of the part of the mainland where they now dwell, and never had any other name than that which they still bear; and in proof of this they show an ancient temple of the Carian Jove in the country of the Mylasians. 1

There is a third temple, that of the Carian Zeus, common to all Carians, in the use of which also the Lydians and Mysians participate, on the ground that they are brethren. 2

One of the interesting phases of Cretan religion was the worship of the local Zeus. The deity must not be confused, however, with the so-called Aryan or Indo-European Zeus of the philologists of a past generation. The name Zeus is less ancient than the deities to whom it was applied. It is derived from the root div, meaning "bright" or "shining". In Sanskrit it is Dyaus, in Latin Diespiter, Divus, Diovis, and Jove, in Anglo-Saxon Tiw, and in Norse Tyr; an old Germanic name of Odin was Divus or Tivi, and his descendants were the Tivar. The Greeks had not a few varieties of Zeus. These included: "Zeus, god of vintage", "Zeus, god of sailors," "Bald Zeus", "Dark Zeus" (god of death and the underworld), "Zeus-Trophonios" (earth-god), "Zeus of thunder and rain", "Zeus, lord of flies", "Zeus, god of boundaries", "Zeus Soter", as well as the "Carian Zeus" and the "Cretan Zeus". The chief gods of alien peoples were also called Zeus or Jupiter. Merodach of Babylon was "Jupiter Belus" and Amon of Thebes "Jupiter Amon", and so on.

The worship of Zeus, the father-god, had a political significance. He was imposed as the chief deity on

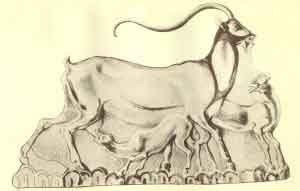

WILD GOAT AND YOUNG: FAIENCE RELIEF, FROM KNOSSOS (See page 139)

Reproduced from "Annual of the British School at Athens", by kind permission of the Committee and of Messrs. Macmillan & Co., Ltd.

p. 153

various Pantheons by the Hellenic conquerors of prehistoric Greece, but local deities suffered little or no change except in name. Dionysus might be called Zeus, but he still continued to be Dionysus, the son of the Great Mother, and did not become Zeus the self-created father-god.

The legend of the Cretan Zeus is as follows: It had been prophesied by Uranus and Gaia that Cronos would be displaced by one of his own children. He endeavoured to avert this calamity by swallowing each babe that was born to his wife, Rhea. After he had thus disposed of five of his family, Rhea went to Crete, and in a mountain cave there gave birth to Zeus. She then returned to her husband and presented him with a stone dressed up as a babe, which he swallowed.

Rhea was assisted by her priests, the Curetes, who danced a war or fertility dance, and her child was fostered by nymphs (the Cretan "mothers"), who gave him honey, so that Cronos would not hear his cries. Milk for nourishment was provided by the goat Amalthea. So strong was the child that soon after birth he broke off one of the goat's horns, which he presented to the nymphs: it afterwards became known as Cornucopia, the "horn of plenty", because it became filled with whatever its owner desired.

When Zeus grew up he rescued his brothers and sisters from the stomach of Cronos, and also took forth the stone which had been substituted for himself: this stone became sacred to his worshippers. Afterwards he deposed his father and sat on the throne as chief deity. Like other ancient gods, he reigned for a time and then died. His grave was pointed out in Crete, as several classical authors have testified. 1 Perhaps it was on

p. 154

account of their habit of repeating this and other ancient legends that the Cretans became so notorious among orthodox Greeks. Paul wrote of them: "There are many unruly and vain talkers and deceivers . . . whose mouths must be stopped; who subvert whole houses, teaching things which they ought not. . . . One of themselves, even a prophet of their own, said, The Cretans are always liars." 1

"Later Cretan tradition", writes Sir Arthur Evans, "has persistently connected the tomb of Zeus with Mount Juktas, which rises as the most prominent height on the land side above the site of Knossos. Personal experiences obtained during two recent explorations of this peak go far to confirm this tradition. All that is not precipitous of the highest point of the ridge of Juktas is enclosed by a 'Cyclopean' wall of large roughly oblong blocks, and within this enclosure, especially towards the summit, the ground is strewn with pottery, dating from Mycenæan to Roman times, and including a large number of small cups of pale clay exactly resembling those which occur in votive deposits of Mycenæan date in the caves of Dikta and of Ida, also intimately connected with the cult of the Cretan Zeus."

In the vicinity is "the small church of Aphendi Kristos, or the Lord Christ, a name which in Crete clings in an especial way to the ancient sanctuaries of Zeus, and marks here in a conspicuous manner the diverted but abiding sanctity of the spot. Popular tradition, the existing cult, and the archaeological traces point alike to the fact that there was here 'a holy sepulchre' of remote antiquity." 2

Early Christian missionaries similarly appropriated elsewhere the "holy places" of the Pagan cults. St. Paul's

p. 155

[paragraph continues] Cathedral in London probably marks the site of the ancient sanctuary of the god Lud, which was approached by Ludgate (the way of Lud). Ancient sculptured stones are often found built into the walls of old chapels. Sometimes the local saint was worshipped after death as if he had acquired the attributes of the Pagan deity he displaced. Bulls were offered up in Applecross, Ross-shire, in 1656, "upon the 25th August", runs a minute of Dingwall Presbytery, "which day is dedicate, as they conceive, to Sn. Mourie as they call him". 1

The Cretan Zeus was a deity who each year died a violent death and came to life again. He thus resembled closely the Egyptian Osiris, the culture king, who introduced agriculture, was slain by Set (one of whose forms was the black pig), and afterwards became Judge of the Dead. We do not know what name was borne by this Cretan deity. It may have been "Velchanos", the youthful warrior of Cretan tradition. A Knossian cult may have called him Minos. As we have seen, this culture king, who during life was famed as a lawgiver, became one of the judges of the dead in the Homeric Hades. Apparently he was deified and regarded as a form of the Cretan Dionysus, who differed somewhat from the Thracian Dionysus.

At what period Zeus-Dionysus was introduced into Crete it is impossible to say with certainty. His close association with agriculture and the underworld suggests that he was known at an early period, but, as will be shown in the next chapter, not necessarily the earliest.

To the agriculturists the myths and customs associated with the sowing and reaping of grain were of as much importance as the implements they used. Every people who

p. 156

in early times adopted the agricultural mode of life adopted also the religious practices associated with it. Persistent folk-legends in Greece pointed to Egypt as the fountainhead of agricultural religion. Diodorus Siculus says that the mysteries of Dionysus are identical with those of Osiris, and that the Isis and Demeter mysteries are the same also, the only difference being in the names applied to the deities. 1 "Osiris", says Herodotus, "is named Dionysus (Bacchus) by the Greeks." 2

The Cretan Zeus-Dionysus links not only with Osiris, but also with Tammuz of Babylon, Ashur of Assyria, Attis of Phrygia, Adonis of Greece, Agni of India and his twin-brother Indra, the Germanic Scef and Frey and Heimdal, and the Scoto-Irish Diarmid. Each of these deities was apparently a developed form of a primitive culture-god, who was a deity of love, fertility, and vegetation; he symbolized the grass required by pastoralists, the fruit of wild and cultivated trees, the spring flowers, and the corn; in short, he was the provider of the food-supply, and he was the life-principle in the food.

In pre-historic times, when the migrating peoples had a vague conception of the mysterious Power which controlled the Universe and the lives of men, they did not give concrete and permanent form to the deities they worshipped and propitiated and controlled by the performance of magical ceremonies. They believed that the Power was manifested in various forms at different periods, and existed in all forms at one and the same time. Osiris appeared among men as a wise king who introduced agriculture and inaugurated just laws; he was at the same time the moon and the young bull, goat, or boar, who was given origin by a "ray of light" issuing from the moon. He was the ancestor of men and edible animals; he was

p. 157

the "vital spark" or life-essence n all that grew; he was the Nile which fertilized the sun-parched desert. Each Pharaoh was an Osiris, and each pious individual who died became one with Osiris in the agricultural heaven which he attained by obeying the laws of Osiris. Thus Proclus says, in reference to the Greek mysteries: "The gods assume many forms and change from one to another; now they are manifested in the emission of shapeless light, now they are of human shape, and anon appear in other and different forms". 1

The Cretan god was the son of the Great Mother who has been identified with Rhea. Apparently he also became her husband. Osiris was the son of Isis, or of Isis and Nepthys--"the bull begotten of the two cows Isis and Nepthys", and he was also at once the husband and father of Isis. Tammuz was the son and spouse of Ishtar, and the later Adonis the lover and son of Aphrodite.

The goddess Demeter and the god Dionysus, her son, were said to be of Cretan origin. According to Firmicus Maternus, Dionysus was the illegitimate son of King Jupiter of Crete, and was hated by Queen Juno. On one occasion, when Jupiter prepared to leave the island, he appointed Dionysus to reign in his place. Juno plotted, during her husband's absence, with the Titans, who lured the young prince away and devoured him. Minerva, his sister, however, rescued his heart and gave it to Jupiter on his return, and that high god enclosed the heart in a case and placed it in a temple which he erected, so that it might be worshipped. Other myths of similar character are told regarding the young god who was mangled like the Egyptian Osiris. One variation states that Jupiter had the heart pounded in a mortar and given to Semele, who, after eating it, gave birth once more to Dionysus.

p. 158

In the Egyptian Anpu-Bata story, Bata, who is evidently a primitive god resembling Osiris, exists in various forms at different periods. His soul enters a blossom, and when the blossom is destroyed the soul enters a sacred bull; the bull is slain and the soul is enclosed in two trees: the trees are cut down, and a chip having entered the mouth of the Pharaoh's wife, that lady gives birth to a child who is no other than the original Bata.

The identification of the god with an animal suggests totemism. In one of the early culture stages it was believed that the spirit of the eponymous tribal ancestor existed in a bull, a bear, a pig, or a deer, as the case might be. Invariably the animal was an edible one--the source of the food-supply, or the guardian of it. Osiris, in one part of Egypt, was a bull and in another a goat. He appears also to have had a boar form. Set went out to hunt a wild boar when he found the body of Osiris and tore it in pieces.

The sacred animal was tabooed for a certain period of the year, or altogether. In Egypt the pig was never eaten except sacrificially. Herodotus says: "The pig is regarded among them (the Egyptians) as an unclean animal, so much so that if a man in passing accidentally touch a pig, he instantly hurries to the river and plunges in with all his clothes on. Hence, too, the swineherds, notwithstanding that they are of pure Egyptian blood, are forbidden to enter into any of the temples, which are open to all other Egyptians; and further, no one will give his daughter in marriage to a swineherd, or take a wife from among them, so that the swineherds are forced to intermarry among themselves. They do not offer swine in sacrifice to any of their gods, excepting Bacchus (Osiris) and the moon, whom they honour in this way at the same

p. 159

time, sacrificing pigs to both of them at the same full moon, and afterwards eating of the flesh. . . . At any other time they would not so much as taste it." 1

According to one of the Cretan legends regarding Zeus-Dionysus, as related by Athenæus, 2 the animal which nourished with its milk the young god of the cave was a sow. "Wherefore all the Cretans consider this animal sacred, and will not taste of its flesh; and the men of Præsos perform sacred rites with the sow, making her the first offering at the sacrifice." 3 The pig taboo extended as far as Wales, Scotland, and Ireland, and is still remembered. 4

Dionysus was also associated with the goat, as we have seen. A clay impression of a gem from Knossos shows an infant sitting beside a horned sheep. 5 Possibly we have here another form of the legend. The various animals may have been totemic. Different tribes claimed descent from different animals which were associated with the culture-god whom they adopted.

It would appear that the bull tribe achieved ascendancy in Crete, for the horns of that animal, a piece of "ritual furniture", which Sir Arthur Evans refers to "by anticipation" as "the horns of consecration", is the commonest cult objective on pottery, frescoes, gems, steles, and altars. The horns were evidently a symbol of the god of fertility. It would appear that before Zeus-Dionysus was depicted in human shape he was worshipped through his symbols or attributes.

Another symbol of the god was the 8-form shield. In North Africa it is found associated with the Libyan

p. 160

goddess Neith, who was a Great Mother with a fatherless son. On Mycenæan and Cretan signets and seals this shield is sometimes shown with human head and arms. It was used by one of the Hittite tribes, and may be identical with the Bœotian shield. A similar pattern also "appears as an ornamental motive on a bronze belt of the latest Bronze or earliest Hallstatt period in Hungary". 1 The so-called "spectacle marking" on the Scottish sculptured stones, which sometimes appears upright and sometimes longwise, may have been an 8-form shield of symbolic significance--an attribute of the god or goddess of fertility.

The double axe was another distinctive symbol of the Cretan god. In Malta certain folk-tales make reference to "Bufies", which is believed to signify "Axe-land", situated somewhere beyond the Sahara. "Axe-land", says Mr. R. N. Bradley, "must be one of the original homes of the axe, and therefore possibly of Neolithic culture." 2 Votive stone axes, perforated for suspension, are common in Malta, Cyprus, and other Mediterranean islands. On the sculptured stones of Brittany the double axe appears as a symbol or hieroglyph, and it is sometimes grasped by an outstretched hand. 3 In Crete the double axe with long handle was depicted between the "horns of consecration" in outline on stones of pillars of palaces and the Dictæan inner cave, and inside houses, apparently as a charm. It figures on a gold signet from Mycenæ in elaborate form, beside a goddess, seated beneath a vine. On the upper part of the signet the sun and crescent moon are enclosed by "water rays". Hovering high on the left is the 8-form shield with human head, an uplifted arm with a

THE PRINCIPAL ROOM OF THE MUSEUM AT CANDIA, CRETE

In the foreground is a great double axe from Aghia Triadha.

p. 161

staff or spear in the hand, and a single leg below. The goddess is approached by votaries, who make offerings of flowers including the iris and hyacinth. On a gem from Knossos the goddess grasps the double axe in her hand, as she does also on a mould from Palaikastro, and other objects found elsewhere. Sir Arthur Evans is of opinion that "labyrinth" is derived from labrys, the Lydian (or Carian) name for the Greek double-edged axe. 1 "The suffix in -nth has been conclusively shown", says Professor Burrows, "to belong to that interesting group of pre-Hellenic words that survives both in place-names like Corinth (Corinthos) and Zakynthos . . . and in common words that would naturally be borrowed by the invaders from the old population." Some of these are the words for "barley-cake", "basket", "hedge-sparrow", and "worm". "The similarly formed word for 'mouse'," he adds, "which remains as the ordinary Greek word. . . . is quoted by the Greek grammarians as a Cretan word." 2

Words like "absinth" and "hyacinth" are similarly survivals that have been borrowed. Professor Burrows thinks, however, that laura, lavra, or labra, signified "passage". Laburinthos would thus mean "place of passages". He notes that "the early Eastern Church called its monasteries Laurai, or Labri as they were sometimes spelt. The name must have been originally given, either from the cloisters round them, or because of the long passages, with the monks' cells leading off them; but this does not seem to have been consciously felt, and the word was used for the monastery as a whole. The name indeed is still seen in The Lavra, a monastery at Mount Athos." 3

The Cretan Zeus was, as a deity of vegetation, associated

p. 162

with tree- and water-worship. In the myth about Cronos swallowing the stone there is evidently a memory of stone-worship also.

It would appear that more than one folk-wave entered Crete during the thousands of years which were covered by the Neolithic Period. At Knossos the earliest settlers constructed wattle huts, plastered with mud, and were well advanced in civilization. The Magasa folks, on the other hand, who produced fewer and cruder artifacts, had more substantial houses. They built low walls of stone) and erected a timber framework, which they enclosed in brick. A similar architectural method appears to have obtained among the Anatolian Hittites in historic times. Inside the Magasa house walls were plastered, and the flat roofs were made of plastered reeds. Both these sections of Cretans, as has been shown, obtained obsidian from Melos, and worked it beside their dwellings, as the finds of flake testify. Whether, however, either or both of them were contemporaries of the dwellers in the artificial cave at Miamu is uncertain. It is suggestive, however, to find that the historic Cretans had sacred caves like the Hittites, the prehistoric people of Phoenicia, and the French and Spanish Palæolithic folk of the Aurignacian and Magdalenian stages of culture. Did they adopt certain of the religious customs of the descendants of the Palæolithic folks who survived on the island? Or was there among the earliest settlers a community of Libyans of mingled stock? The Cro-Magnon type survives till the present day on the North African coast, where it has been identified by Collignon and Bertholon among the Berbers. 1 It may be that there were tall men among the Cretans, who were distinguished as warriors, as was Goliath among the Philistines. The Philistines were of Cretan origin.

p. 163

[paragraph continues] Some of the athletes depicted on vases and frescoes appear to have been above the average stature. It is of interest to recall, too, in this connection, that the slim waists that distinguished the Cretans were characteristic also of the Aurignacian cave-dwellers. This custom of waist-tightening may have survived from the archæological Hunting Period. In Gaelic stories there are references to the "hunger belt". It is possible, too, that the Cretan girdle had a religious significance, like the "prayer belt" of Russia. Sir Arthur Evans found at Knossos snake girdles which had been deposited as votive offerings in a sacred place. Two snakes enfolded the hips of the snake-goddess. Aphrodite's girdle compelled love. The Germanic Brunhild's great strength lay in her girdle. The dwarf Laurin was subdued when his girdle was wrenched off by the heroic Dietrich. 1 Ishtar wore a girdle.

As has been indicated also (Chapter II), the bell-mouthed skirt worn by the Minoan women was similar to that of the Cro-Magnon women depicted in the Aurignacian caves 10,000 years ere the Neolithic folk settled in Crete. The gowns of the Egyptian women were of the "hobble" pattern.

Crete, of course, could not have maintained a large population of hunters. There can be little doubt that its inhabitants were not numerous at any period prior to the introduction of agriculture. As the great bulk of its historic population were of Mediterranean type, it would appear that North Africa was the source of the high civilization which obtained at Knossos during the Late Neolithic Period. The religion of the Cretan agriculturists resembled in essential details that of the Egyptians. Their chief deity was the Great Mother, whose son died, like Osiris, a violent death. No doubt religious borrowing

p. 164

took place when the Cretans traded with Egypt, and that the traditions preserved by Herodotus and other writers in this connection were not without some foundation. But, as there existed so close a resemblance between the fundamental beliefs of the separated peoples, it is impossible to discover to what extent Cretan religion was influenced by Nilotic. The Sumerian Tammuz myth, which also resembles the Osirian, was fully developed at the dawn of history, and Merodach, a fusion of Tammuz and Ramman, had for one of his names Asari, which has been identified with Asar (Osiris).

A conclusion which may be suggested is that the various sections of the Mediterranean race had, prior to their migrations to suitable areas of settlement from the North African homeland, adopted a system of religious beliefs which was closely associated with their agricultural mode of life, and passed it on afterwards to the peoples, who learned from them how to till and sow the soil and reap the harvest in season. The myths of the Phrygian Attis and the Germanic Scef are probably relics of cultural contact in bygone ages.

Footnotes

145:1 So called after the semi-crystalline rock emitted as lava from the chief volcano of the Lipari Islands.

145:2 Browning's "Cleon".

145:3 Ilios, p. 247.

148:1 The Ancient Egyptians, pp. 41 et seq.

149:1 The writer and a friend once tested a limestone quern and ascertained that it deposited as much grit as covered a three-penny piece in about fifteen minutes.

150:1 The Early Egyptians, pp. 172, 173.

150:2 A History of Egypt, Vol. II, pp. 146, 147.

152:1 Herodotus, I, 171.

152:2 Strabo, 659.

153:1 Diodorus Siculus, III, 61; Cicero, De natura deorum, III, 21, 53; Lucian, Philopseudes, 3, &c.

154:1 Titus, i, 10-12.

154:2 Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. XXI, pp. 121, 122.

155:1 St. Maelrubha, the early Christian missionary, who gave his name to Loch Maree (formerly Loch Ewe). He flourished in the seventh century.

156:1 Diodorus Siculus, I, 96.

156:2 Herodotus, II, 144.

157:1 Ennead, I, 6, 9.

159:1 Herodotus, II, 47.

159:2 Pausanias, VII, 17, 5.

159:3 Cults of the Greek States, L. R. Farnell, Vol. I, p. 37.

159:4 Myths of Babylonia and Assyria, pp. 293-4, and Egyptian Myth and Legend, pp. vii, vii.

159:5 Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. XXI, p. 129.

160:1 British Museum Early Iron Age Guide, p. 7.

160:2 Malta and the Mediterranean Race, p. 126 (1912).

160:3 See The Mediterranean Race, G. Sergi, p. 313, for illustration or axes on one of the sculptured stones.

161:1 Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. XXI, pp. 106 et seq.

161:2 The Discoveries in Crete, p. 120.

161:3 The Discoveries in Crete, pp. 118, 119.

162:1 Ripley's Races of Europe, p. 177.

163:1 Teutonic Myth and Legend, pp. 380 and 428.