Thomas Hale Boggs (original) (raw)

Sections

- Hale Boggs in Congress

- Warren Commission

- J. Edgar Hoover

- Primary Sources

- Student Activities

- References

Thomas Hale Boggs, the son of William Robertson Boggs, a businessman, and Claire Josephine Hale, was born in Long Beach, Mississippi, on 15th February, 1914. Boggs was descended from Colonial and Revolutionary War ancestors, grew up in Jefferson Parish, Louisiana, the county just west of New Orleans. (1)

After attending public and Roman Catholic schools there, he went to Tulane University, where he majored in journalism, was the editor of the school newspaper. He was also a member of the American Student Union. Later this organisation was accused of being under the control of the American Communist Party. Boggs graduated in 1935. He received his law degree from Tulane two years later. Boggs helped to form the People's League, a reform group that was seeking to break the iron grip of the family of Huey Long, who had been assassinated in 1935. (2)

Boggs, a member of the Democratic Party, running as an anti-Long family candidate, defeated incumbent Paul H. Maloney in the 1940 Democratic primary and won the general election unopposed. When he was sworn in he was, at 27, the youngest member of Congress. Defeated two years later, he enlisted in the United States Naval Reserve and served in the Potomac River Naval Command during the rest of the Second World War.. (3)

Hale Boggs in Congress

After the war, Boggs began his political comeback. He was again elected to Congress in 1946 (on Maloney's retirement). After the Brown v. Board of Education decision, he signed the 1956 Southern Manifesto condemning desegregation. Boggs also voted against the Civil Rights Act of 1957. According to The New York Times: "Mr. Boggs, an intelligent and urbane lawyer from New Orleans, can command the attention of an audience under the most trying circumstances. He is one of perhaps a dozen men with the ability to gain and hold the hushed attention of the House without so much as a gentle tap of the presiding officer's gavel. It has been said that no speech ever changed a vote in Congress, but Mr. Boggs and a few others are talking evidence to the contrary. Colleagues not only listen to him, but they also often heed his advice. The elements of his persuasiveness include a prepossessing figure (6 feet, 200 pounds), a resonant voice, usually pitched in conversational tones, an ability to articulate even the most complicated point clearly and concisely and a thorough knowledge of his subject. As a rule, he speaks without text or notes. He uses a relaxed manner and a boyish smile to disarm his opponents in debate and an occasionally sharp tongue to deflate them." (4)

Hale Boggs became a protégé of Speaker Sam Rayburn of Texas and in 1960 played a key role in urging that his old friend, Lyndon B. Johnson, to accept the Vice-Presidential spot with John F. Kennedy, despite the misgivings of Rayburn. Boggs told Rayburn, that. "If you don't want Johnson to run, it means that you'll elect Richard Nixon." (5)

Warren Commission

After the death of John F. Kennedy, his deputy, Johnson, was appointed president. He immediately set up a commission to "ascertain, evaluate and report upon the facts relating to the assassination of the late President John F. Kennedy." The seven man commission was headed by Chief Justice Earl Warren and included Thomas Hale Boggs, Gerald Ford, Allen W. Dulles, John J. McCloy, Richard B. Russell and John S. Cooper. (6)

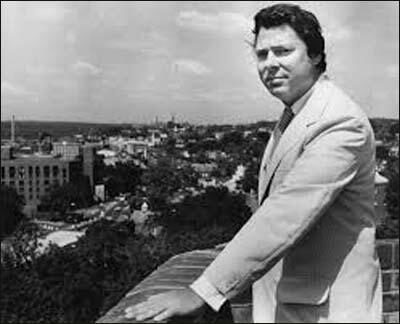

Thomas H. Boggs

Lyndon B. Johnson also commissioned a report on the assassination from J. Edgar Hoover. Two weeks later the Federal Bureau of Investigation produced a 500 page report claiming that Lee Harvey Oswald was the sole assassin and that there was no evidence of a conspiracy. The report was then passed to the Warren Commission. Rather than conduct its own independent investigation, the commission relied almost entirely on the FBI report. According to Gerald D. McKnight, the author of Breach of Trust: How the Warren Commission Failed the Nation and Why (2005): "Hoover and his executive officers at FBIHQ intended to control the Commission to assure that it ratified the solution to the assassination decided upon by the government over the first weekend." (7)

At the first meeting of the Warren Commission, Allen W. Dulles handed out copies of a book to help define the ideological parameters he proposed for the Commission's forthcoming work. "American assassinations were different from European ones, he told the Commission. European assassinations were the work of conspiracies, whereas American assassins acted alone." John J. McCloy said that it was of paramount importance to "show the world that America is not a banana republic, where a government can be changed by conspiracy." Chief Justice Earl Warren said at the same meeting, "We can start with the premise that we can rely upon the reports of the various agencies that have been engaged in the investigation." (8)

Chief Justice Earl Warren handing over the report to Lyndon B. Johnson

Richard B. Russell, John S. Cooper and Thomas H. Boggs all questioned the FBI report that suggested a single-bullet (CE 399) had inflicted all seven non-fatal wounds of President John F. Kennedy and Governor John B. Connally. John J. McCloy also initially had doubts about the single bullet theory, he came around to it, siding with Allen W. Dulles and Gerald Ford. Russell phoned up President Lyndon B. Johnson and said: "They're trying to prove that the same bullet that hit Kennedy first was the one that hit Connally, went through him and through his hand, his bone, and into his leg... the Commission believes that the same bullet that hit Kennedy hit Connally. Well, I don't believe it!" Johnson's reply was "I don't either." (9)

Nellie Connally, who was in the same car as her husband later told Walter Cronkite: "The first sound, the first shot, I heard, and turned and looked right into the President's face. He was clutching his throat, and just slumped down. He Just had a - a look of nothingness on his face. He didn't say anything. But that was the first shot. The second shot, that hit John - well, of course, I could see him covered with - with blood, and his - his reaction to a second shot. The third shot, even though I didn't see the President, I felt the matter all over me, and I could see it all over the car." John Connolly. added: "Beyond any question, and I'll never change my opinion, the first bullet did not hit me. The second bullet did hit me. The third bullet did not hit me." (10)

The Warren Commission reported to President Johnson ten months later. It reached the following conclusions:

(1) The shots which killed President Kennedy and wounded Governor Connally were fired from the sixth floor window at the southeast corner of the Texas School Book Depository.

(2) The weight of the evidence indicates that there were three shots fired.

(3) Although it is not necessary to any essential findings of the Commission to determine just which shot hit Governor Connally, there is very persuasive evidence from the experts to indicate that the same bullet which pierced the President's throat also caused Governor Connally's wounds. However, Governor Connally's testimony and certain other factors have given rise to some difference of opinion as to this probability but there is no question in the mind of any member of the Commission that all the shots which caused the President's and Governor Connally's wounds were fired from the sixth floor window of the Texas School Book Depository.

(4) The shots which killed President Kennedy and wounded Governor Connally were fired by Lee Harvey Oswald.

(5) Oswald killed Dallas Police Patrolman J. D. Tippit approximately 45 minutes after the assassination.

(6) Within 80 minutes of the assassination and 35 minutes of the Tippit killing Oswald resisted arrest at the theater by attempting to shoot another Dallas police officer.

(7) The Commission has found no evidence that either Lee Harvey Oswald or Jack Ruby was part of any conspiracy, domestic or foreign, to assassinate President Kennedy.

(8) In its entire investigation the Commission has found no evidence of conspiracy, subversion, or disloyalty to the US Government by any Federal, State, or local official.

(9) On the basis of the evidence before the Commission it concludes that, Oswald acted alone. (11)

Thomas H. Boggs was the most opposed to the idea of a lone gunman. According to Bernard Fensterwald: "Almost from the beginning, Congressman Boggs had been suspicious over the FBI and CIA's reluctance to provide hard information when the Commission's probe turned to certain areas, such as allegations that Oswald may have been an undercover operative of some sort. When the Commission sought to disprove the growing suspicion that Oswald had once worked for the FBI, Boggs was outraged that the only proof of denial that the FBI offered was a brief statement of disclaimer by J. Edgar Hoover. It was Hale Boggs who drew an admission from Allen Dulles that the CIA's record of employing someone like Oswald might be so heavily coded that the verification of his service would be almost impossible for outside investigators to establish." According to one of his friends: "Hale felt very, very torn during his work (on the Commission) ... he wished he had never been on it and wished he'd never signed it (the Warren Report)." Another former aide argued that "Hale always returned to one thing: Hoover lied his eyes out to the Commission - on Oswald, on Ruby, on their friends, the bullets, the gun, you name it." (11)

Boggs was a stanch supporter of President Lyndon B. Johnson including the Administration's posture on the Vietnam War. He also supported Johnson's domestic policies. He had consistently opposed civil rights legislation but voted for the 1965 Voting Rights Act. After he announced he was withdrawing from being a candidate for the 1968 presidential election, Boggs gave his support to Hubert Humphrey. (12)

J. Edgar Hoover

Thomas Hale Boggs came under considerable pressure when he began questioning the Warren Report in public. On 5th April 1971, Boggs made a speech on the floor of the House accusing the FBI of tapping his phones and keeping dossiers on members of Congress. Boggs said the files consisted of information on seven persons who had written critically of the commission's findings. He accused J. Edgar Hoover, of being "incompetent and senile" and that the FBI under Hoover's most recent years "adopted the tactics of the Soviet Union and the Hitler's Gestapo." (13)

Ron Kessler, reported in the Washington Post that his son Thomas Hale Boggs Jr claimed that the FBI had mounted a smear campaign against Boggs because of his criticism of the Warren Commission Report. "The material, which Thomas Boggs made available, includes photographs of sexual activity and reports on alleged communist affiliations of some authors of articles and books on the assassination." (14) He said these dossiers had been compiled by the FBI on Warren Commission critics in order to discredit them. "Mr. Boggs said the files consisted of information on seven persons who had written critically of the commission's findings." (15)

Thomas Hale Boggs disappeared while on a campaign flight from Anchorage to Juneau, Alaska, on 16th October, 1972. Also killed in the accident was Nick Begich, a member of the House of Representatives. (14a) No bodies were ever found and in 1973 his wife, Lindy Boggs, was elected in her husband's place. (16) The Los Angeles Star, on November 22, 1973, reported that before his death Boggs claimed he had "startling revelations" on Watergate and the assassination of John F. Kennedy. (17)

Primary Sources

(1) The New York Times (10 January 1962)

"When Hale takes the floor, there's always order in the House." That comment by a colleague points up a basic factor in the political strength of Representative Thomas Hale Boggs, the new Democratic whip, or assistant majority leader, of the House. For Mr. Boggs, an intelligent and urbane lawyer from New Orleans, can command the attention of an audience under the most trying circumstances. He is one of perhaps a dozen men with the ability to gain and hold the hushed attention of the House without so much as a gentle tap of the presiding officer's gavel.

It has been said that no speech ever changed a vote in Congress, but Mr. Boggs and a few others are talking evidence to the contrary. Colleagues not only listen to him, but they also often heed his advice.

The elements of his persuasiveness include a prepossessing figure (6 feet, 200 pounds), a resonant voice, usually pitched in conversational tones, an ability to articulate even the most complicated point clearly and concisely and a thorough knowledge of his subject.

As a rule, he speaks without text or notes. He uses a relaxed manner and a boyish smile to disarm his opponents in debate and an occasionally sharp tongue to deflate them.

At 47 years of age, Mr. Boggs has won national attention mainly as an effective spokesman for liberal foreign trade policies. He has been equally influential in the passage of tax legislation to finance the Interstate Highway System.

In addition, he has had an influential hand in tightening narcotics control laws and in shaping tax revision bills, rivers and harbors measures and sugar control legislation. Although he has always stood with the Southerners on civil rights, Mr. Boggs is not regarded as an extremist. He signed the "Southern Manifesto" in 1956 against the Supreme Court's school desegregation decree but otherwise has been largely inactive in racial controversies.

On legislative issues pitting liberals against conservatives, he has voted against the conservative coalition in the House more often than he has voted with it. The post of deputy Democratic whip of the House was created especially for Mr. Boggs by Speaker Sam Rayburn in 1954. This was regarded by some colleagues as a gesture in support of Mr. Bogg's long-standing ambition to become Speaker himself some day. That ambition has probably been fortified by his elevation to the third-ranking post-that of whip- Influential in Legislation in the House Democratic leadership.

Despite his new responsibilities, Mr. Boggs is expected to continue as the fourth-ranking Democratic member of the House Ways and Means Committee and chairman of a House-Senate subcommittee on foreign trade policy. Mr. Boggs got into politics shortly after winning a law degree from Tulane University in 1937 as a leader of a New Orleans reform group that temporarily broke the power of the old Huey P. Long machine. Mr. Boggs was first elected to Congress in 1940 and, at the age of 26, was its youngest member. Defeated in his bid for a second term in 1942, he served as a naval officer in World War II and regained his House seat in 1946. He has held it since then.

At Tulane. Mr. Boggs was editor in chief of the campus weekly. The Hullabaloo. The editor for Newcombe Collège, Tulane's women's branch, was Corrine Morrison Claiborne. They were married in 1938. They have three children, Barbara, 22, Thomas Hale, Jr., 21, and Corinne, 18.

Mr. and Mrs. Boggs entertain frequently at large, politically oriented parties in their big Georgia-style white home in near-by Bethesda, Md. Mrs. Boggs, long active in Democratic political affairs, was co-chairman of President Kennedy's inaugural committee last year. For relaxation, the Congressman grows turnip greens, asparagus, beans, beets, onions, lettuce, broccoli, corn - everything you imagine" in Mrs. Bogg's words in a huge garden at their Bethesda home. Mr. Boggs was born at Long Beach, Miss., but spent most of his boyhood in Jefferson Parish, the Louisiana county just west of New Orleans. His parents were William Robertson and Claire Josephine Hale

(2) The New York Times (20 August 1968)

When John F. Kennedy was nominated as the Democratic Presidential candidate in 1960 and offered the Vice- Presidential nomination to Lyndon B. Johnson, some of Mr. Johnson's closest political advisers urged him to reject it. The advisers, led by the late Sam Rayburn of Texas, feared that Mr. Johnson would be buried politically as Vice President under Mr. Kennedy. It was Thomas Hale Boggs, Democratic Representative from Louisiana and, like Mr. Johnson, a protégé of Mr. Rayburn, who convinced the then Speaker of the House to persuade Mr. Johnson to accept the nomination. "If you don't want Johnson to run," Mr. Boggs told Mr. Rayburn, "it means that you'll elect Richard Nixon."

This combination of hard-headed political realism and a capacity for reconciling divergent views within his party has characterized the career of Mr. Boggs, who is currently putting his mediating skills to their toughest test as chairman of the Democratic platform committee, which opened its hearings yesterday in Washington.

While he views himself as a reconciler and mediator of intra party differences, Mr. Boggs has left little doubt during his long Congressional career about where he personally stands on most issues. He was an ardent supporter of John F. Kennedy's Presidential candidacy and, as House Whip, was one of the late President's trusted lieutenants in Congress.

Since 1963, he has been an equally stanch supporter of President Johnson's domestic and foreign policies, including the Administration's posture on Vietnam. In the current Democratic party showdown, Mr. Boggs has cast his lot solidly with the forces of Vice President Humphrey. He is an internationalist with an intense interest in foreign trade expansion. He consistently opposed civil rights legislation, at least until 1965, when many believe he turned a corner by voting for a strong voting rights bill.

Hale Boggs (he does not use his first name) was born on Feb. 15, 1914, in Long Beach, Miss., the son of William Robertson Boggs, a businessman, and the former Claire Josephine Hale. Mr. Boggs, who is descended from Colonial and Revolutionary War ancestors, grew up in Jefferson Parish, La., the county just west of New Orleans.

After attending public and Roman Catholic schools there, he went to Tulane University, where he majored in journalism, was the editor of the school newspaper and was graduated in 1935 Phi Beta Kappa. He received his law degree from Tulane two years later. Mr. Boggs's interest in politics was kindled while he was still a student. After graduation, he helped to form the People's League, a reform group that was seeking to break the iron grip of the Long family on Louisiana politics.

In 1940, when he was only 25 years old, Mr. Boggs was elected to Congress from Louisiana's Second District. He was the youngest Democrat seated in the House in January, 1941, and one of the youngest Congressmen in history. After serving one term, however, Mr. Boggs lost the Democratic primary and returned to private law practice in New Orleans.

During World War II he spent almost three years in the Navy. Mr. Boggs was re-elected to Congress in 1946 and has remained in the House ever since. He ran unsuccessfully for Governor of Louisiana in 1951. Since 1962, he has been the House Whip, making him the third-ranking Democratic member.

He enjoys gardening and he and his wife entertain lavishly, often inviting several hundred people to dinner Mrs. Boggs is the former Corinne Morrison Claiborne and is known as Lindy. She is descended from the first Governor of the Louisiana Territory, W.C. C. Claiborne. She met Mr. Boggs while she was a student at Sophie Newcomb College of Tulane University and both were working on the campus newspaper. They were married in 1938. They have a son, Thomas Hale Boggs Jr., a Washington lawyer; and two daughters, Mrs. Paul E. Sigmund, wife of a Princeton professor of politics, and Mrs. Steven V. Roberts, whose husband is a member of the news staff of The New York Times.

Despite his early stand against civil rights legislation, Mr. Boggs has always drawn strong support from Negroes in his district. A friend in New Orleans recalls that he once told his Negro maid to take special pains to get the house in order because Mr. Boggs was coming to visit. The maid commented: "Why, are there white folks for him, too?"

(3) Gerald D. McKnight, Breach of Trust: How the Warren Commission Failed the Nation and Why (2005)

In May 1964, about the midway point in the Warren Commission's investigation, Director J. Edgar Hoover appeared before the commissioners to provide them with his special insights into the Kennedy assassination and the benefit of his forty years as head of the nation's most prestigious and revered law enforcement agency. Hoover was probably America's most renowned and best-recognized public figure, and the Commission wanted to trade on his eclat.

Hoover was scheduled to give his testimony when the Commission was still working under Warren and Rankin's initial time frame and expected to finish up its work by the end of June. Ford and Dulles did most of the early questioning. What they wanted from America's iconic hero was his assurance that the assassination had been the act of a lone nut. Hoover was quick to oblige, assuring the commissioners that there was not "a scintilla of evidence showing any foreign conspiracy or domestic conspiracy that culminated in the assassination of President Kennedy." Hoover told the commissioners they could expect to be second-guessed and violently disagreed with, whatever their ultimate findings were. He pointed out that the FBI was already inundated with crank letters and calls from kooks, weirdos, crazies, and self-anointed psychics, all alleging a monstrous conspiracy behind Kennedy's violent death. Whether orchestrated or not, his testimony before the Commission provided the director an opportunity to launch a preemptive strike against future dissenters and critics of the Warren Commission and, by extension, Hoover's FBI, the Commission's investigative arm.

Whatever the merits, if any, of Hoover's profiling of future Commission dissenters and critics, its first test was a hands-down failure. The Commission's first dissenter was Senator Richard Brevard Russell, Jr., one of the most conservative as well as respected and admired members of the U.S. Senate. Russell wielded great power in the upper chamber and had earned the title "dean of the Senate." During 1963-1964, when the Warren Commission was conducting its business, no U.S. legislator was at the White House as frequently as the senior senator from Georgia.

On September 18, 1964, a Friday evening, President Johnson phoned Russell, his old political mentor and longtime friend, to find out what was in the Commission's report scheduled for release within the week. Johnson was surprised that Russell had suddenly bolted from Washington for a weekend retreat to his Winder, Georgia, home. Russell was quick to clear up the mystery as to why he needed to get out of the nation's capital. For the past nine months the Georgia lawmaker had been trying to balance his heavy senatorial duties with his responsibilities as a member of the Warren Commission, a perfect drudgery that Johnson had imposed upon him despite Russell's strenuous objections. No longer a young man and suffering from debilitating emphysema, Russell was simply played out. But it was the Warren Commission's last piece of business that had prompted his sudden Friday decision to escape Washington.

That Friday, September 18, Russell forced a special executive session of the Commission. It was not a placid meeting. In brief, Russell intended to use this session to explain to his Commission colleagues why he could not sign a report stating that the same bullet had struck both President Kennedy and Governor Connally. Russell was convinced that the missile that had struck Connally was a separate bullet. Senator Cooper was in strong agreement with Russell, and Boggs, to a lesser extent, had his own serious reservations about the single-bullet explanation. The Commission's findings were already in page proofs and ready for printing when Russell balked at signing the report. Commissioners Ford, Dulles, and McCloy were satisfied that the one-bullet scenario was the most reasonable explanation because it was essential to the report's single-assassin conclusion. With the Commission divided almost down the middle, Chairman Warren insisted on nothing less than a unanimous report. The stalemate was resolved, superficially at least, when Commissioner McCloy fashioned some compromise language that satisfied both camps.'

The tension-ridden Friday-morning executive session had worn Russell out. He told Johnson that the "damn Commission business whupped me down." Russell was in such haste to get away that he had forgotten to pack his toothbrush, extra shirts, and the medicine he used to ease his respiratory illness. Although Russell had support from Cooper and Boggs, he was the only one who actively dug in his heels against Rankin and the staff's contention that Kennedy and Connally had been hit by the same nonfatal bullet. Because of Russell's chronic Commission absenteeism he never fully comprehended that the final report's no-conspiracy conclusion was inextricably tied to the validity of what would later be referred to as the "single-bullet" theory. But he had read most of the testimony and was convinced that the staff's contention that the same missile had hit Kennedy and Connally was, at best, "credible" but not persuasive. "I don't believe it," he frankly told the president. Johnson's response -whether patronizing or genuine remains guesswork - was "I don't either." In summing up their Friday-night exchange, Russell and Johnson agreed that the question of the Connally bullet did not jeopardize the credibility of the report. Neither questioned the official version that Oswald had shot President Kennedy.

(4) Bernard Fensterwald, Assassination of JFK: Coincidence or Conspiracy (1974)

"You have got to do everything on earth to establish the facts one way or the other. And without doing that, why everything concerned, including every one of us is doing a very grave disservice. Thus House Majority Leader Hale Boggs delivered an admonishment of sorts to his Warren Commission colleagues on January 27, 1964. Along with Senator Richard Russell, and to a lesser degree, Senator John Sherman Cooper, Congressman Boggs served as a beacon of skepticism and probity in trying to fend off the FBI and CIA's efforts to "shade" and indeed manipulate the findings of the Warren Commission.

Like Russell, Boggs was, very simply, a strong doubter. Several years after his death in 1972, a colleague of his wife Lindy (who was elected to fill her late husband's seat in the Congress) recalled Mrs. Boggs remarking, "Hale felt very, very torn during his work [on the Commission] ... he wished he had never been on it and wished he'd never signed it [the Warren Report]." A former aide to the late House Majority Leader has recently recalled, "Hale always returned to one thing: Hoover lied his eyes out to the Commission - on Oswald, on Ruby, on their friends, the bullets, the gun, you name it... "

Almost from the beginning, Congressman Boggs had been suspicious over the FBI and CIA's reluctance to provide hard information when the Commission's probe turned to certain areas, such as allegations that Oswald may have been an undercover operative of some sort. When the Commission sought to disprove the growing suspicion that Oswald had once worked for the FBI, Boggs was outraged that the only proof of denial that the FBI offered was a brief statement of disclaimer by J. Edgar Hoover. It was Hale Boggs who drew an admission from Allen Dulles that the CIA's record of employing someone like Oswald might be so heavily coded that the verification of his service would be almost impossible for outside investigators to establish...

Congressman Boggs had been the Commission's leading proponent for devoting more investigative resources to probing the connections of Jack Ruby. With an early recognition that "the most difficult aspect of this is the Ruby aspect," Boggs had wanted an increased effort made to investigate the accused assassin's murderer.

Boggs was perhaps the first person to recognize something which numerous Warren Commission critics would write about in future years: the strange variations and dissimilarities to be found in Lee Harvey Oswald's correspondence during 1960 to 1963. Some critics have advanced the theory that some of Oswald's letters - particularly correspondence to the American Embassy in Moscow, and later, to the Fair Play for Cuba Committee - may have been "planted" documents written by someone else. In 1975 and 1976, the investigations of the Senate Intelligence Committee and other Congressional groups disclosed that such uses of fabricated correspondence had been a recurring tool of the FBI's secret domestic COINTELPRO [Counter Intelligence] program as well as other intelligence operations. In any event, Warren Commission member Boggs and Commission General Counsel Lee Rankin had early on discussed such an idea:

"Rankin: They [the Fair Play For Cuba Committee] denied he was a member and also he wrote to them and tried to establish as one of the letters indicate, a new branch there in New Orleans, the Fair Play For Cuba.

Boggs: That letter has caused me a lot of trouble. It is a much more literate and polished communication than any of his other writing."

It is also known Boggs felt that because of the lack of adequate material from the FBI and CIA the Commission members were poorly prepared for the examination of witnesses. According to a former Boggs staffer, the Congressman felt that lack of adequate file preparation and the sometimes erratic scheduling of Commission sessions served to prevent those same sessions from being adequately substantive. Consequently, Boggs cut down his participation in these sessions as the investigation stretched on through 1964...

On April 5, 1971, House Majority Leader Hale Boggs took the floor of the House to deliver a speech that created a major stir in Washington for several weeks. Declaring that FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover was incompetent and senile, and charging that the FBI had, under Hoover's most recent years adopted "the tactics of the Soviet Union and Hitler's Gestapo"; Boggs demanded Hoover's immediate resignation. Boggs also charged that he had discovered that certain FBI agents had tapped his own telephone as well as the phones of certain other members of the House and Senate. In his emotional House speech, Boggs went on to say Attorney General Mitchell says he is a law and order man. If law and order means the suppression of the Bill of Rights . . . then I say "God help us." As the Washington Post noted, "The Louisiana Democrat's speech was the harshest criticism of Hoover ever heard in the House . . . It was the first attack on Hoover by any member of the House leadership."

At the time, Boggs' startling speech created a sensation in Washington. Observers were uncertain as to his exact motivations in demanding Hoover's resignation, and there was an immediate critical reaction from Hoover's various defenders. It has been reported that sources within the FBI and the Attorney General's office began spreading stories that Boggs was a hopeless alcoholic. However, it was not until almost four years later that the motivation behind Boggs' outburst came into clearer focus.

(5) Bernard Fensterwald, Assassination of JFK: Coincidence or Conspiracy (1974)

The Senate investigators finally established that FBI Director Hoover not only had prepared secret "derogatory dossiers" on the critics of the Warren Commission over the years, but had even ordered the preparation of similar "damaging" reports about staff members of the Warren Commission. Whether FBI Director Hoover intended to use these dossiers for purposes of blackmail has never been determined.

Although it was not until eleven years after the murder of John F. Kennedy that the FBI's crude harassment and surveillance of various assassination researchers and investigators became officially documented, other information about it had previously surfaced.

Mark Lane, the long time critic of the Warren Report has often spoken of FBI harassment and surveillance directed against him. While many observers were at first skeptical about Lane's characteristically vocal allegations against the FBI, the list of classified Warren Commission documents that was later released substantiated Lane's charges, as it contained several FBI files about him. Lane had earlier uncovered a February 24, 1964 Warren Commission memorandum from staff counsel Harold Willens to General Counsel J. Lee Rankin. The memorandum revealed that FBI agents had Lane's movements and lectures under surveillance, and were forwarding their reports to the Warren Commission.

In March, 1967, the official list of secret Commission documents then being held in a National Archives vault included at least seven FBI files on Lane, which were classified on supposed grounds of "national security." Among these secret Bureau reports were the following: Warren Commission Document 489, "Mark Lane, Buffalo appearances;" Warren Commission Document 694, "Various Mark Lane appearances;" Warren Commission Document 763, "Mark Lane appearances;" and Warren Commission Document 1457, "Mark Lane and his trip to Europe."

In at least one documented instance, the CIA had been equally avid in "compiling" information on another critic, the noted European writer Joachim Joesten, who had written an early "conspiracy theory" book, titled Oswald: Assassin or Fall Guy (Marzani and Munsell Publishers, Inc., 1964, West Germany). A Warren Commission file (Document 1532), declassified years later, revealed that the CIA had turned to an unusual source in their effort to investigate Joesten. According to the document, which consists of a CIA memorandum of October 1, 1964, written by Richard Helms' staff, the CIA conducted a search of some of Adolph Hitler's Gestapo files for information on Joesten.

Joachim Joesten, an opponent of the Hitler regime in Germany, was a survivor of one of the more infamous concentration camps. The Helms memorandum reveals that Helms' CIA aides had compiled information on Joesten's alleged political instability - information taken from Gestapo security files of the Third Reich, dated 1936 and 1937. In one instance, Helms' aides had used data on Joesten which had been gathered by Hitler's Chief of S.S. on November 8, 1937. While the CIA memorandum did not mention it, there was good reason for the Third Reich's efforts to compile a dossier on Joesten. Three days earlier, on November 5, 1937, at the infamous "Hossbach Conference," Adolph Hitler had informed Hermann Goering and his other top lieutenants of his plan to launch a world war by invading Europe."

In late 1975, during a Senate Intelligence Committee hearing that featured the questioning of top FBI officials, Senator Richard Schweiker disclosed other secret FBI surveillance of Warren Commission critics. Senator Schweiker disclosed new information from a November 8, 1966 memorandum by J. Edgar Hoover, relating to other dossiers on the critics. According to Schweiker, "Seven individuals [were] listed, some of their files... not only included derogatory information, but sex pictures to boot.

During the Senate Committee session, Schweiker also disclosed that "we came across another FBI letter several months later on another of the critic's personal files. I think it is January 30, 1967. Here, almost three months apart, is an ongoing campaign to personally derogate people who differed politically. In this case it was the Warren Commission [critics].

As will be seen in the chapter on "Links to Watergate," copies - of the FBI's "derogatory dossier" on another leading Warren Commission critic, associated with Mark Lane, were later distributed through the Nixon White House by secret Nixon investigator John Caulfield, John Dean, and H. R. Haldeman's top aides.

Still further information relating to FBI-CIA surveillance of the Warren Commission critics was disclosed in January, 1975 by Senator Howard Baker and the New York Times. On January 17, 1975, the Times disclosed that Senator Baker had come across an extensive CIA dossier on Bernard Fensterwald, Jr., the Director of the Committee to Investigate Assassinations, during the course of Baker's service on the Senate Watergate Committee. Senator Baker was then probing various areas of CIA involvement in the Watergate conspiracy. The New York Times reported that Baker believed the dossier on Fensterwald indicated that the Agency was conducting domestic activities or surveillances - prohibited by the Agency charter's ban on domestic involvement.

Among the items contained in the CIA dossier on Fensterwald was an Agency report of May 12, 1972 titled "#553 989." The CIA report indicated that this detailed surveillance was conducted under the joint auspices of the CIA and the Washington, D. C. Metropolitan Police Intelligence Unit. D. C. Police involvement with the CIA, which in some cases was illegal, subsequently erupted into a scandal which resulted in an internal police investigation in 1975 and 1976, as well as a Congressional investigation.

The May 12, 1972 CIA report on Fensterwald states:

"On 10 May 1972, a check was made at the Metropolitan Police Department Intelligence , Unit concerning an organization called The Committee To Investigate Assassinations located at 927 15th Street, N.W., Washington, D. C. . . .

On 10 May 1972, a check was made (DELETION)

On 11 May 1972, a physical check was made of 927 15th Street .... to verify the location of the above-mentioned organization. This check disclosed that the Committee To Investigate Assassinations is located in room 409 and 414 of the Carry Building."

After setting forth a room by room analysis of the offices and businesses located on the same floor as the Committee, the report went on:

"A discreet inquiry was made with (DELETION) of this building showing no government interest concerning the Committee To Investigate Assassinations. This source stated that on a daily basis that traffic coming and going from this office is very busy. This source stated that on a daily basis the office is operated by two individuals one of whose name is Jim."

Former Warren Commission member Hale Boggs would no doubt have been pleased that these activities of the FBI and CIA were finally brought to light. As his son has pointed out, Boggs' denunciation of J. Edgar Hoover in April of 1971 was based in part on his knowledge of the FBI's murky surveillance of Warren Commission critics. Whether Boggs believed the FBI's surveillance of him was based on the fact that he himself had privately become a fierce critic of Commission's conclusions is not known.

On October 16, 1972, Hale Boggs vanished during a flight in Alaska from Anchorage to Juneau. Despite a thirty-nine-day search by the Air Force, Navy, and Coast Guard, no trace of the twin-engine plane on which Boggs was traveling has ever been found.

Had he been alive today, Boggs would probably have become Speaker of the House, having held the number two leadership post in the Congress at the time of his disappearance. There is no doubt Boggs would have been a singularly important figure in any re-opening of the Kennedy case.

(6) The New York Times (20 January 1971)

As the Lady Bird Johnson campaign special rolled through the South in the fall of 1964, Thomas Hale Boggs of Louisiana drew wild cheers from the trainside crowds.

"On this great, long train we had grits for breakfast!" cried Representative Boggs. (Loud cheers.) "And we gonna have tur nip greens and black-eyed peas for lunch," he roared. (More cheers.) "And after talkin' to a million Southerners we gonna have crawfish bisque, red beans and rice and creole gumbo for dinner," he concluded, bringing more shrieks of joy from the crowds.

This ability to inject a sense of excitement into even a simple mess of turnip greens points up the oratorical skill of the man who will become a principal voice of the Democratic party as majority leader of the House.

In winning the majority leadership, Hale Boggs had to overcome a number of obstacles, some of them so critical that the seriousness of his candidacy was initially questioned.

Liberal-minded reformers contended that his elevation from the No. 3 post, that of majority whip, into the majority leadership would rep resent no break with what they viewed. as "the tired leadership of the past."

There was concern, too, within the ranks of his supporters when word spread last year that a Baltimore contractor had remodeled the Boggses white columned Bethesda mansion at "substantially below cost" and later sought Mr. Boggs's aid in pressing a claim for $5million in extra payment for a Capital garage.

Mr. Boggs also had to over come the apprehension of some fellow Southerners who felt he was too much of a "national Democrat." He skillfully chaired the committee that produced a largely liberal Democratic platform at the party's convention in 1968. He voted for most of President Johnson's Great Society domestic reforms, And, while he opposed early civil rights legislation, in recent years he has supported such legislation.

Even his critics, Northern or Southern, readily concede that Mr. Boggs is one of the most effective orators in Congress. As his voice booms out, a hush falls over the usually noisy House chamber.

"When Hale takes the floor, there's always order in the House," a colleague once observed.

His first lusty cry came nearly 57 years ago, on Feb. 15, 1914, in the Gulf Coast town of Long Beach, Miss. The family later moved to Jefferson Parish, La., just west of New Orleans.

At Tulane University, young Hale Boggs majored in journalism, and, in 1937, won his law degree.

He was 26 years old, the youngest man in Congress, when he first came to the House in 1941. Defeated two years later, he served in the Navy during the rest of World War II and made a House comeback in 1946.

He became a protégé of Speaker Sam Rayburn of Texas and in 1960 played a key role in urging that his old friend, Lyndon B. Johnson, accept the Vice-Presidential spot on John F. Kennedy's ticket, despite the misgivings of Speaker Rayburn.

"If you don't want Johnson to run, it means you elect Richard Nixon," Mr. Boggs informed Speaker Rayburn, who had insisted that Mr. Johnson turn down the Kennedy offer.

With the death of Speaker Rayburn, Mr. Boggs moved into a leadership post as majority whip under Speaker John W. McCormack in 1962.

Witty and urbane, Mr. Boggs was once voted by Congressional secretaries as "the most charming man on Capitol Hill." He is also a notable host with a New Orleans resident's appreciation of good food and fun.

For luncheons in his Capitol office, he serves vege tables from the small home garden that he tends. A special favorite is the sweet corn.

There are gay parties at the Boggs estate, now that the children are no longer at home. One daughter is Mrs. Steven V. Roberts, wife of the Los Angeles bureau chief for The New York Times; another is Mrs. Paul Sigmund, wife of a professor of politics at Princeton University. A son, Thomas Hale Boggs Jr., ran for Congress last year in suburban Mary land but was defeated.

Until last year, it never rained on any of the 15 or more lavish garden parties given by Hale and Lindy Boggs. But this time, the thousand or so guests had to scurry for cover as the rains came.

Through it all, a New Orleans jazz combo blared out from a trolley parked in the garden. The Boggses had dubbed it, appropriately enough for a leadership candidate, "A Streetcar Named Desire."

(7) The New York Times (25 November 1972)

An Air Force Rescue Coordination center officially suspended to day the search for Representative Hale Boggs of Louisiana, Representative Nick Begich of Alaska and two others who have been missing since taking off Oct. 16 in a twin-engine plane for a 550-mile flight from here to Juneau.

Mr. Boggs, the House majority leader, and Mr. Begich were accompanied by the latter's aide, Russell L. Brown. The pilot was Don E. Jonz of Fairbanks. The two Representatives had been scheduled to address a fund-raising dinner in Juneau that day, but their plane never landed there. Mr. Boggs arrived in Anchorage Oct. 15 for three fund-raising affairs with Mr. Begich.

The Air Force, Army, Coast Guard and Civil Air Patrol con ducted a 39-day search of the mountain ranges, glaciers and icy seas of Prince William Sound. Gradually worsening weather, along with snowfalls earlier this week and a lack of clues, caused the Air Force to suspend the search.

The search will continue unofficially, however, since a hunt for two Californians who disappeared Wednesday in a twin-engine plane while flying the same Anchorage-to-Juneau route has just begun.

While the search for the Boggs plane has now been called off, neither Representative has been declared dead or presumed dead.

The first step toward such an official declaration is expected within the next two weeks with the convening of a special jury in Alaska. Under Alaska law, anyone can file a petition calling upon the courts to declare a missing person presumed dead. The court then names special six-man jury to hear witnesses.

Jury findings of presumed dead must be unanimous. A judge must then approve the findings, and only then could Gov. William A. Egan of Alaska call a special election to fill the Begich vacancy.

Mr. Boggs was just 26, the youngest man in Congress, when he first entered the House in 1941. A fiercely deter mined man, an ear-shattering orator, a masterful politician, a sternly partisan Democrat, he edged his way from one position of power to another, finally emerging as House majority leader and one of the most influential men in Congress.

It has not always been easy. Fellow Southerners felt he was too much of a "national Democrat." Northerners felt he was too much of a "Southern Democrat." And there were long months, before his election as majority leader nearly two years ago, when he was so beset with personal problems and ill health that the serious ness of his candidacy was initially questioned.

To those who dismissed his candidacy for the leadership post, he would say calmly: "A wise politician once told me that politics is played in the present tense. We don't know what the present tense will be."

Opposed by Democrats from both the right and the left, he doubled his efforts, reminding fellow members of past favors he had bestowed on them, of campaign speeches he had made on their behalf. He won on the second ballot, outpolling his principal opponent, Representative Morris K. Udall of Arizona, by a margin of nearly 2 to 1.

Musing about the leadership election and some of his earlier trials in winning re-election to the House, Mr. Boggs remarked a year or so ago: "One reason they have never succeeded in defeating me, no matter how much they have spent, is the fact that we have always helped people."

Until his disappearance, he was still pursuing that course. hoping some day to become Speaker of the House. Unopposed for re-election to his House seat in the Nov. 7 election, he had promised to campaign for many of his fellow Democrats facing tough races.

To keep that pledge, he took a plane for Alaska to campaign for Representative Nick Begich, a fellow Democrat. There were dozens of other such campaign trips on his schedule.

His effectiveness as a crowd pleaser has never been questioned, by either the left or the right. He once injected a sense of high drama into a simple mess of turnip greens, as witness the wild cheers of the train-side crowds as the Lady Bird Johnson campaign special rolled through the South in the fall of 1964.

"On this great long train we had grits for breakfast!" he cried. There were loud cheers.

"And we gonna have turnip greens and black-eyed peas for lunch," he roared (more cheers).

"And after talkin' to a million Southerners we gonna have crawfish bisque, red beans and rice and Creole gumbo for dinner," he concluded, bringing more shrieks of joy from the crowd.

That represents the homey side of the big man from Louisiana, a Southerner with a gusty appetite for good food, good liquor and lavish garden parties that he has had his wife, Lindy, hold yearly at their suburban Washington mansion.

More often, he has been a moody intellectual, a deeply devout Roman Catholic, pursuing a lonely course that he knew would alienate his Southern companions in the House and white voters in his New Orleans district.

He voted against early civil rights measures but supported the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the open housing legislation a few years later.

There were moments of high drama that day in 1965 when he strode to the well of the House and, his voice booming into the far reaches of the vast chamber, began:

"I wish I could stand here as a man who loves my state. born and reared in the South, who has spent every year or his life in Louisiana since he was 5 years old, and say there has not been discrimination.

"But, unfortunately, it is not so," he told the hushed gathering. "I shall support the bill because I believe the fundamental right to vote must be a part of this great experiment in human progress under freedom which is America."

The pressures that were to lead to his near breakdown began building during those years of the nineteen-sixties. As majority whip, he helped steer through Congress much of the Great Society legislation - such as Medicare and school aid of his old friend, President Johnson.

He served too, on the House Ways and Means Committee, a demanding assignment. He was a member of the Warren Com mission that investigated the assassination of President Kennedy, another old friend. And he was a member of the President's Committee on Violence and numerous other commit tees and commissions.

But it was not until 1968 that he began showing signs of breaking. Once again, he teamed up with civil rights forces by voting for open housing, then flew off to Chicago to preside over the drafting of an unusually liberal platform for a Democratic convention that was to end with rioting in the streets.

He left the debris of Chicago, an exhausted man, to face the toughest fight of his career, his own bid for re-election. He won, but in the months that followed, his often erratic behavior, both on and off the floor of the House, threatened to thwart his ambition to be come majority leader some day.

In winning the majority leadership, he overcame many obstacles. Liberals felt that his elevation from majority whip to majority leader would mark no break with what they viewed as "the tired leadership of the past."

There was concern, too, when word spread that a Baltimore contractor had remodeled the white-columned Bethesda mansion of Mr. and Mrs. Boggs at "substantially below cost" and had later sought Mr. Boggs's aid in pressing a claim for $5 million in extra payment for a Capitol garage.

There were those who questioned his emotional stability, too, after he had informed the House, in a rambling, often incoherent speech, that his home and office had been "bugged" by the Federal Bureau of Investigation - a charge that he has never proved but maintained was true.

While the leadership team of Speaker Carl Albert and Major ity Leader Boggs was criticized by younger, liberal, Democrats as "just more of the same tired old leadership," Mr. Boggs often won applause from fellow Democrats for his partisan at tacks on President Nixon and Congressional Republicans and it was Hale Boggs, the skilled orator, to whom they turned for campaign help in the waning weeks before the November election.

Thomas Hale Boggs (he never used his first name) was born on Feb. 15, 1914, in the Gulf Coast town of Long Beach, Miss. His family later moved to Jefferson Parish, La., just west of New Orleans.

With a scholarship and just 35,heenteredTulaneUniversity,wherehestudiedjournalismandlaw.BythetimehegraduatedwithalawdegreeandaPhiBetaKappakeyin1937,hewasmaking35, he entered Tulane University, where he studied journal ism and law. By the time he graduated with a law degree and a Phi Beta Kappa key in 1937, he was making 35,heenteredTulaneUniversity,wherehestudiedjournalismandlaw.BythetimehegraduatedwithalawdegreeandaPhiBetaKappakeyin1937,hewasmaking400 a month, working on the copy desk of The New Orleans States and selling radios, chewing gum, clothing and candy in his spare moments.

As a young lawyer, he be came leader of a New Orleans reform group that temporarily broke the power of the old Huey Long political machine. Years later, however he was backed by Huey Long's son, Senator Russell B. Lone, in an unsuccessful bid for Governor in 1951.

His national political debut came with election to Congress in 1940, but he was defeated two years later and served in the Navy in World War II be fore making a House comeback in 1946.

He became a protégé of House Speaker Sam Rayburn of Texas and in 1960 played a key role in urging his old friend, Lyndon Johnson, to accept the Vice-Presidential spot on John Kennedy's ticket, de spite the initial misgivings of Speaker Rayburn.

"If you don't want Johnson to run, it means you elect Richard Nixon," Mr. Boggs in formed the Speaker, who had insisted that Mr. Johnson turn down the Kennedy offer.

Two years later, with the death of Speaker Rayburn, Mr. Boggs began his political climb, becoming majority whip under Speaker John W. McCormack. As ranking Democrat on the Ways and Means Committee, he was a leading oil protectionist but also an articulate spokesman for liberal foreign trade policies.

He was a stanch supporter, too, of President Johnson's Vietnam policies and, while critical of President Nixon's domestic programs, he supported Mr. Nixon's handling of the Vietnam war.

In early summer, Mr. Boggs and his wife and the House minority leader, Gerald R. Ford, and his wife visited China, not long after President Nixon's historic visit there.

Witty and urbane, Mr. Boggs was once voted by Congressional secretaries as "the most charming man on Capitol Hill." He was also a notable host with a deep appreciation of good food.

Often, he has been host at luncheons in his Capitol office, serving vegetables from his small home garden, which he tended. A special favorite was the sweet corn, a hybrid produced by the one-time Vice President, Henry A. Wallace. On the long table, too, would appear mounds of shrimp and crabs, flown in from Louisiana and cooked the night before by Mr. Boggs.

For their annual garden party - usually the largest and gayest Congressional fete of he year - Hale and Lindy Boggs also did most of their own cooking.

The. Boggses - she is the former Corinne Morrison Cliborne - were married in 1938 and have three children. One daughter is Mrs. Steven V. Roberts, wife of the Los Angeles bureau chief of The New York Times. Another, Mrs. Paul Sigmund, is the wife of a professor at Princeton University. A son, Thomas Hale Boggs Jr., ran unsuccessfully for Congress from Maryland in 1970 and is a lawyer and lobbyist in Washington.

(8) Ronald Kessler, The Washington Post (21st January, 1975)

The son of the late House Majority Leader Boggs has told The Post that the FBI leaked to his father damaging material on the personal lives of critics of its investigation into John F. Kennedy's assassination. Thomas Hale Boggs, Jr. said his father, who was a member of the Warren Commission, which investigated the assassination and its handling by the FBI, was given the material in an apparent attempt to discredit the critics (of the Warren Commission).

The material, which Thomas Boggs made available, includes photographs of sexual activity and reports on alleged communist affiliations of some authors of articles and books on the assassination.

Boggs, a Washington lawyer, said the experience played a large role in his father's decision to publicly charge the FBI with Gestapo tactics in a 1971 speech alleging the Bureau had wiretapped his telephone and that of other Congressmen.

(9) New York Times (31st January, 1975)

The son of the late Representative Hale Boggs, Democrat of Louisiana, said today that his father had given him dossiers that the Federal Bureau of Investigation had compiled on critics of the Warren Commission in an attempt to discredit them. "They weren't basically sex files," said Tom H. Boggs, of Washington, a lawyer. "They had some of that element but most of the material dealt with leftwing organizations these neoole belonged to."

Mr. Boggs said that he had received the material in late 1970 and had kept it in a safe deposit box. The senior Mr. Boggs was a member of the Warren Comission established to investigate the assassination of President John F. Kennedy.

In 1971, the Congressman made a speech on the floor of the House accusing the F.B.I. of tapping his phones and keeping dossiers on members of Congress. Those charges were never substantiated by Mr. Boggs, who disappeared in October, 1972, while on an airplane flight in Alaska. Mr. Boggs said the files consisted of information on seven persons who had written critically of the commission's findings.

(6) Gerald D. McKnight, Breach of Trust: How the Warren Commission Failed the Nation and Why (2005)

In May 1964, about the midway point in the Warren Commission's investigation, Director J. Edgar Hoover appeared before the commissioners to provide them with his special insights into the Kennedy assassination and the benefit of his forty years as head of the nation's most prestigious and revered law enforcement agency. Hoover was probably America's most renowned and best-recognized public figure, and the Commission wanted to trade on his eclat.

Hoover was scheduled to give his testimony when the Commission was still working under Warren and Rankin's initial time frame and expected to finish up its work by the end of June. Ford and Dulles did most of the early questioning. What they wanted from America's iconic hero was his assurance that the assassination had been the act of a lone nut. Hoover was quick to oblige, assuring the commissioners that there was not "a scintilla of evidence showing any foreign conspiracy or domestic conspiracy that culminated in the assassination of President Kennedy." Hoover told the commissioners they could expect to be second-guessed and violently disagreed with, whatever their ultimate findings were. He pointed out that the FBI was already inundated with crank letters and calls from kooks, weirdos, crazies, and self-anointed psychics, all alleging a monstrous conspiracy behind Kennedy's violent death. Whether orchestrated or not, his testimony before the Commission provided the director an opportunity to launch a preemptive strike against future dissenters and critics of the Warren Commission and, by extension, Hoover's FBI, the Commission's investigative arm.

Whatever the merits, if any, of Hoover's profiling of future Commission dissenters and critics, its first test was a hands-down failure. The Commission's first dissenter was Senator Richard Brevard Russell, Jr., one of the most conservative as well as respected and admired members of the U.S. Senate. Russell wielded great power in the upper chamber and had earned the title "dean of the Senate." During 1963-1964, when the Warren Commission was conducting its business, no U.S. legislator was at the White House as frequently as the senior senator from Georgia.

On September 18, 1964, a Friday evening, President Johnson phoned Russell, his old political mentor and longtime friend, to find out what was in the Commission's report scheduled for release within the week. Johnson was surprised that Russell had suddenly bolted from Washington for a weekend retreat to his Winder, Georgia, home. Russell was quick to clear up the mystery as to why he needed to get out of the nation's capital. For the past nine months the Georgia lawmaker had been trying to balance his heavy senatorial duties with his responsibilities as a member of the Warren Commission, a perfect drudgery that Johnson had imposed upon him despite Russell's strenuous objections. No longer a young man and suffering from debilitating emphysema, Russell was simply played out. But it was the Warren Commission's last piece of business that had prompted his sudden Friday decision to escape Washington.

That Friday, September 18, Russell forced a special executive session of the Commission. It was not a placid meeting. In brief, Russell intended to use this session to explain to his Commission colleagues why he could not sign a report stating that the same bullet had struck both President Kennedy and Governor Connally. Russell was convinced that the missile that had struck Connally was a separate bullet. Senator Cooper was in strong agreement with Russell, and Boggs, to a lesser extent, had his own serious reservations about the single-bullet explanation. The Commission's findings were already in page proofs and ready for printing when Russell balked at signing the report. Commissioners Ford, Dulles, and McCloy were satisfied that the one-bullet scenario was the most reasonable explanation because it was essential to the report's single-assassin conclusion. With the Commission divided almost down the middle, Chairman Warren insisted on nothing less than a unanimous report. The stalemate was resolved, superficially at least, when Commissioner McCloy fashioned some compromise language that satisfied both camps.'

The tension-ridden Friday-morning executive session had worn Russell out. He told Johnson that the "damn Commission business whupped me down." Russell was in such haste to get away that he had forgotten to pack his toothbrush, extra shirts, and the medicine he used to ease his respiratory illness. Although Russell had support from Cooper and Boggs, he was the only one who actively dug in his heels against Rankin and the staff's contention that Kennedy and Connally had been hit by the same nonfatal bullet. Because of Russell's chronic Commission absenteeism he never fully comprehended that the final report's no-conspiracy conclusion was inextricably tied to the validity of what would later be referred to as the "single-bullet" theory. But he had read most of the testimony and was convinced that the staff's contention that the same missile had hit Kennedy and Connally was, at best, "credible" but not persuasive. "I don't believe it," he frankly told the president. Johnson's response -whether patronizing or genuine remains guesswork - was "I don't either." In summing up their Friday-night exchange, Russell and Johnson agreed that the question of the Connally bullet did not jeopardize the credibility of the report. Neither questioned the official version that Oswald had shot President Kennedy.

Russell enjoyed a deserved reputation for devotion to his senatorial responsibilities and mastery of the legislative details of the business that came before the Senate. Consequently, he was sensitive and apologetic about the fact that time constraints had limited him to being only a part-time member of the Commission. As he told Johnson, "This staff business always scares me. I like to put my own views down." When he left Friday afternoon for his Georgia home, he was not at ease in his own mind about McCloy's compromise language. He told Johnson, "I tried my best to get in a dissent. But they came around and traded me out of it by giving me a little ole thread of it." Russell was referring to his less-than-enthusiastic acceptance of McCloy's compromise language. What Russell was not aware of at the time was that wholesale perfidy, not mere pressure for consensus, would stigmatize the Commission's September 18 executive session as one of the most disgraceful episodes in the history of the Kennedy assassination investigation. Rankin suppressed the entire record of the divisions among the commissioners over the single-bullet construction to leave the false impression that the commissioners were in universal agreement on this crucial point. The unreported record revealed that Russell, and by extension the American people, were misled by Rankin's unprecedented deception, whose sole purpose was to hide the fact that unanimous Commission support for the single-bullet "solution" was a fraud.

Russell was more outspoken than any of his colleagues in his displeasure about both the quality of the FBI investigation and the information the FBI and CIA fed to the Commission. He suspected that both agencies were not giving the Commission everything they knew about the assassination. For instance, during the January 27, 1964, executive session the commissioners were wrestling with how to approach FBI director Hoover to help them disprove the rumors and allegations that Oswald had been an FBI source or informant. They discussed the unlikeliness of any possibility that the FBI or CIA, investigating themselves, could be counted upon to be forthcoming with whatever information they had, especially if the allegations were true. Russell was certain that the FBI "would have denied that he was an agent." The Georgia senator was certain the CIA would take the same tack. When he turned to Allen Dulles, the former CIA director agreed with him. Russell, expressing the hopelessness of their quandary, remarked to Dulles, "They (CIA) would be the first to deny it. Your agents would have done exactly the same thing."