Thurber, Texas. (original) (raw)

There never was a Texas town quite like Thurber and there never will be again. In a state not known for coal, Thurber produced tons of "black diamonds" for more than 30 years. In a state known for its independence, Thurber was a wholly company-owned town, right down to the last nail in the last miner's house, and became a union town populated by mostly foreign workers.

Thurber, along with Indianola, is perhaps the state's most celebrated ghost town because it was contrary to ordinary in every way. Situated in the northeast corner of Erath County, almost to the Palo Pinto County line, Thurber was different from every other Texas town of its time. This was not a land of cotton or cattle but of coal, bricks and, later oil. Thurber was one of the first towns in the state to have full electric service and its ice factory, with a 17-ton capacity, was the largest in the Southwest. There was even an opera house. A.C. Greene in his book "A Personal Country" wrote that Thurber had "a kind of dangerous pretension."

"Thurber was a mining town, an industrial city, and a true city, while most of the rest of West Texas burned cow chips for fuel and gathered buffalo bones to sell to survive the droughts," Greene wrote. "While other towns in West Texas considered the buckboard and the buggy the ultimate in transportation, Thurber had a siding for the Pullman Palace cars and private sleepers which were set off the mainline Texas and Pacific Railway at Mingus for the short ramble down to Thurber's station on the town square."

Only company miners, along with some school teachers and preachers, were allowed to live in Thurber, and the miners were a diverse group that representing some 18 or so ethnic groups. Italians made up more than half of the work force with Poles representing about 12 percent. Others came from Britain, Ireland, Mexico, Germany, France, Belgium, Austria, and Sweden and from coal mining regions of the U.S. Early attempts to unionize the workers failed, but the United Mine Workers union was formed in 1903. A second union, the Italian local, followed in 1906. Thurber became the only 100 percent closed shop nation in the country.

A land speculator from Michigan, William Whipple Johnson, discovered coal in the area in the 1880s and began mining operations but, following a strike by the miners, sold the company to a group of eastern investors who formed the Texas and Pacific Coal Company. A contract with the Texas & Pacific Railway, originally negotiated by Johnson, was renegotiated and a new town named for T&P investor H.K. Thurber was built. By the turn of the century, Thurber was the leading coal-producing area in the state and Texas' coal output exceeded the value of all other minerals combined.

The Thurber Brick yards.

TE Post Card Archives

The 1908 smokestack in Thurber

Photo courtesy TXDoT

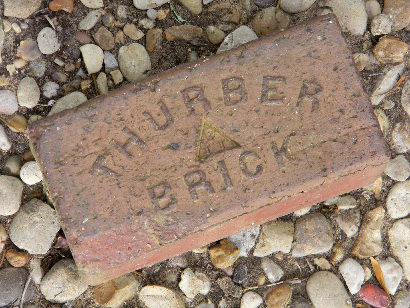

The area that produced the Texas coal also had a large amount of shale clay, which the glad hands of Thurber industry used to produce bricks. Practically the entire town was made of brick. "All its streets and sidewalks, its smokestack and pumphouses, the bandstand on the square, railroad abutments, bridges and watering troughs - all were made of brick," Greene wrote.

In the course of looking for coal and other mineral deposits, mine manager William Knox Gordon became convinced that the area west of town contained significant amounts of coal and gas. Trained geologists disagreed, but when Gordon hit oil a few miles from Thurber, near Strawn, the company okayed continued exploration. That led to the discovery of the wildly productive Ranger oil field in October of 1917 and the beginning of an oil boom that changed everything, including Thurber.

Thurber initially prospered from the local oil boom. The company added "and Oil" to its name but when locomotives converted from coal-fired steam engines to oil burners, Thurber had no market for its coal. To make up for the loss of the coal market, Thurber began producing paving bricks, which are about twice as heavy as an ordinary brick. Thurber bricks paved many Texas highways and streets, including Congress Avenue in downtown Austin, and were used to construct the Galveston Sea Wall, the Bankhead Highway, Camp Bowie and the Fort Worth Stockyards. Then along came concrete and asphalt roads and the market for the paving bricks went the way of coal-fired steam engines.

In 1933, in the middle of the Great Depression, the company announced that the town was being abandoned. The utility poles were taken down and the wire was salvaged. The houses were boarded up and supplies were sold at cost in the company store. In a blink, it was gone.

"Thurber had been built all at once, its population had come all at once, and everything it did all at once," Greene wrote. "And as things turned out, it died all at once."

�

Clay Coppedge November 1, 2014 Column

More "Letters from Central Texas"