Llano Flood of 1935. (original) (raw)

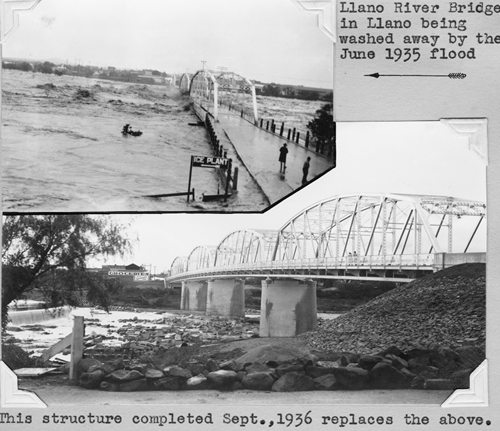

Since 1892, a four-span steel bridge resting on stone supports had extended across the Llano River to connect the northern and southern sides of the small county seat town that shared the river's name.

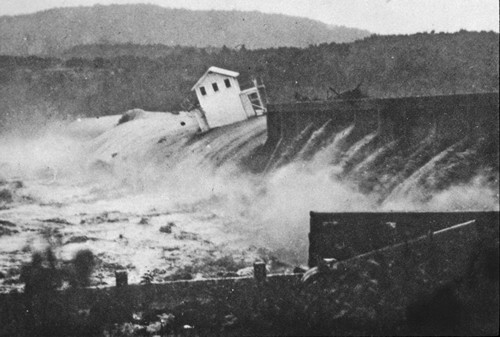

The structure amounted to an impressive piece of engineering for its day, but when heavy rain began pouring down upstream from the bridge in the Hill Country on June 14, 1935, the figurative clock started ticking toward the moment of its destruction. That came on the following morning, when the Llano River crested at 41.5 feet, its highest level in known history.

Frothy, chocolate-colored water roaring down a normally shallow stream swept away three of the bridge's four spans.

Llano River Bridge in Llano being washed away by the 1935 flood

Photo courtesy TXDoT

"Friday's Flood Washed Out Bridge," the weekly Llano News reported on June 20. "The river began to rise at about 8 o'clock in the morning [of Friday, June 15]," the lead article related, "and continued to rise steadily until the bridge had been taken out."

Of course, the flood did much more than wipe out the Llano River bridge. It destroyed two smaller bridges on the Llano, including one at the old German-settled community of Castell. When the surge moved from the Llano to the Colorado, it also washed out the bridge at Marble Falls. Then the water rushed onward to Austin, where it spared-barely-the Congress Avenue bridge that was then the river's principal crossing in the capital city. Even so, the flood waters covered the bridge for a time, isolating north and south Austin.

Elsewhere in the state, heavy rain triggered major flooding along the Nueces and Guadalupe rivers.

Back in Llano, the flood not only cut the town in half, it left parts of town with no electricity, drinking water or commercial ice. On top of all that, Llano had no means of contact with the outside world. While hard to believe given today's instant communication channels, more than 24 hours passed before someone was able to make it to Fredericksburg to report the extensive damage in Llano.

The Llano-Colorado river flood claimed the lives of eight people, including a man who died just doing his job.

High water had taken down the only telephone line between Llano and Austin at a point where it crossed the river about 12 miles downstream from Llano. The Monday following the flood, C. L. Gunderman, a 35-year-old lineman for what was then Southwestern Bell Telephone Co., drowned in the Llano when still fast-moving water capsized a boat he was in. He had been working with other phone company personnel to get the toll line back in operation. When the Llano News went to press two days later, Gunderman's body was still missing.

In addition to the loss of lives (statewide at least 24 people died in weather-related incidents) and damage to property in that Depression-era flood, 3,000-plus pecan trees along the Llano River were uprooted by the flood. That caused significant economic harm to landowners who made part of their living selling nuts harvested on their river-front acreage.

Meanwhile, workers from the state Highway Department (now Texas Department of Transportation) were busy building a temporary, low-water bridge to reconnect Llano and get State Highway 16 back in service. A permanent bridge was not completed until September 1936, lightning speed compared with highway construction projects today.

Wider and higher than the original bridge, that now 82-year-old bridge survived the recent devastating Llano-Colorado River flood, the worst flood along the two streams since the 1935 event.

A report prepared in 1937 by the Austin-San Antonio office of what is now the National Weather Service noted that, "Timely warnings were issued for these floods, and large amounts of property saved thereby�.However, loses were heavy, especially to bridges and highways." Back then, those warnings would only have come via commercial radio broadcasts or teletype messages.

Central Texans had realized for years that the only way to lessen the impact of the periodic torrential rains that turned Hill Country rivers and streams into deadly torrents would be a dam or series of flood control dams on the Colorado. The Lower Colorado River Authority had been created earlier that year, so while the June flood did not inspire the construction of the dams that resulted in the Highland Lakes chain, the disaster certainly gave the project impetus.

Within three years of the flood, dams had been completed or were under construction at three points along the Colorado-Buchanan Dam, Mansfield Dam (Lake Travis) and Tom Miller Dam (Lake Austin). During their extensive live coverage of the latest major flood, Austin's television stations as well as its daily newspaper all compared the event with the 1935 disaster and noted that the LCRA's dams and the lakes they formed had done much to tame the two rivers. But as KXAN's longtime weathercaster Jim Spencer pointed out during the flood, "Mother nature is never going to be completely tamed."

1940s map showing Llano River coursing through Llano County

From Texas state map #4335

Courtesy Texas General Land Office