The poor man, with a gush of tears, answered, "Am I talking to a man or an angel?" — eighth illustration for the Illustrated Children's Edition of "Robinson Crusoe" (1815) (original) (raw)

Full Caption

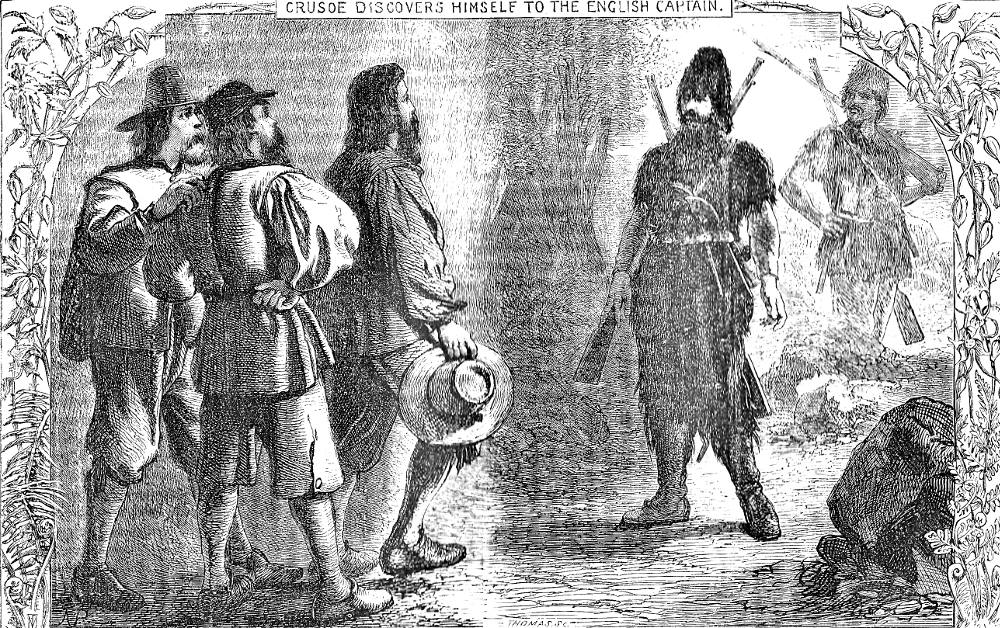

The poor man, with a gush of tears, answered, "Am I talking to a man or an angel?" — "A man, an Englishman," I returned, "ready to assist and save you: tell me your case." [See page 73.]

Original Passage Adapted

I came as near them undiscovered as I could, and then, before any of them saw me, I called aloud to them in Spanish, “What are ye, gentlemen?” They started up at the noise, but were ten times more confounded when they saw me, and the uncouth figure that I made. They made no answer at all, but I thought I perceived them just going to fly from me, when I spoke to them in English. “Gentlemen,” said I, “do not be surprised at me; perhaps you may have a friend near when you did not expect it.” “He must be sent directly from heaven then,” said one of them very gravely to me, and pulling off his hat at the same time to me; “for our condition is past the help of man.” “All help is from heaven, sir,” said I, “but can you put a stranger in the way to help you? for you seem to be in some great distress. I saw you when you landed; and when you seemed to make application to the brutes that came with you, I saw one of them lift up his sword to kill you.”

The poor man, with tears running down his face, and trembling, looking like one astonished, returned, “Am I talking to God or man? Is it a real man or an angel?” “Be in no fear about that, sir,” said I; “if God had sent an angel to relieve you, he would have come better clothed, and armed after another manner than you see me; pray lay aside your fears; I am a man, an Englishman, and disposed to assist you; you see I have one servant only; we have arms and ammunition; tell us freely, can we serve you? What is your case?” “Our case, sir,” said he, “is too long to tell you while our murderers are so near us; but, in short, sir, I was commander of that ship — my men have mutinied against me; they have been hardly prevailed on not to murder me, and, at last, have set me on shore in this desolate place, with these two men with me — one my mate, the other a passenger — where we expected to perish, believing the place to be uninhabited, and know not yet what to think of it.” [Chapter XVII, "The Visit of the Mutineers"]

Text on the Facing Page

It was easy to kill them all while they were asleep, or to take them prisoners. He replied, that there were two incorrigible villains among them, to whom it would not be safe to shew mercy. I then gave each of them a musket, and advised them to fire among them at once; but he was cautious of shedding blood. In the midst of our discourse some of them waked, and two walked from the rest. The captain said he would gladly spare them. "Now," said I, "if the rest escape you, it is your fault." Animated with this, they went to the sailors, and he captain reserving his own piece, the two men shot one of the villains dead, and wounded the other. He who was wounded cried out for help, when the captain knocked him down with the stock of his musket. There were three more in company, one of whom was wounded. They begged for mercy, and I coming up, gave orders for sparing their lives, on condition of their being bound hand and foot while they staid in the island. [p. 75]

Commentary

Written in an age in which slavery was still perfectly legal throughout the British Empire, and particularly throughout Britain's West Indian possessions, Defoe has his high-minded protagonist introduce the obviously Negro "Man Friday" in this picture as his "servant" rather than as his slave. The three sailors stare at Crusoe in wonder, as if he might really be an angel rather than an English castaway. The incredulous Captain, distinguished by his hat, centre, is in full naval uniform of the period 1795-1815; the only incongruous element in the uniforms of his subordinates are the large-brimmed hats. Friday is minimized, relegated to the margin. Crusoe's status as a colonist rather than a soldier of empire is implied by his wearing a short saw rather than a pistol in his broad belt.

Related Material

- Daniel Defoe

- Illustrations of Robinson Crusoe by various artists

- Illustrations of children’s editions

Parallel Scenes from Stothard (1790), a Children's Book (1818), and Cassell's (1863-64)

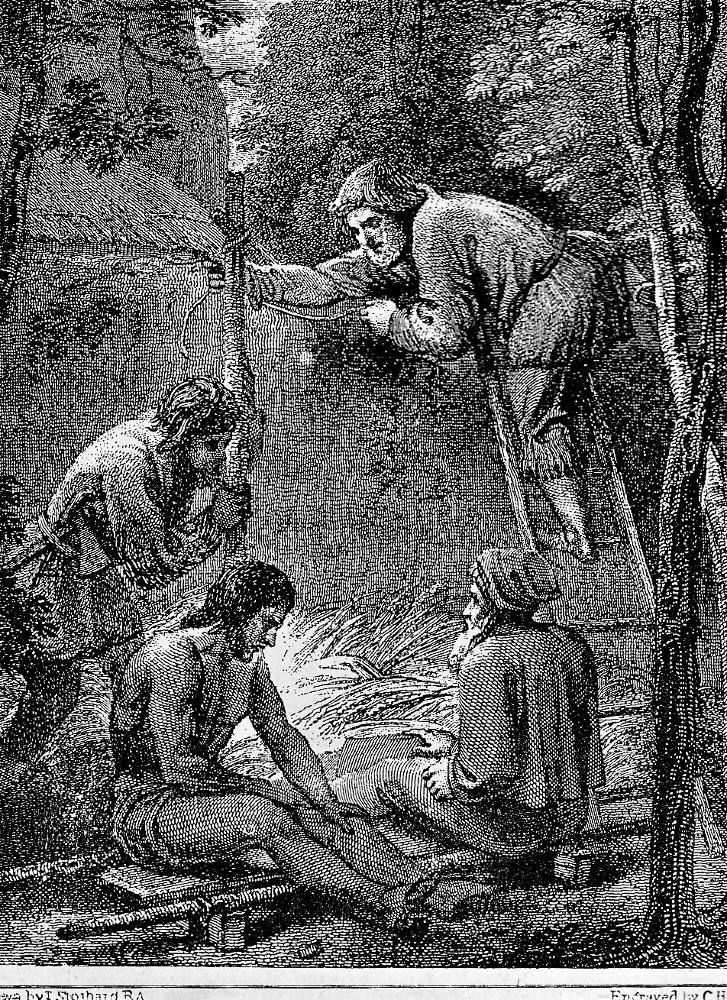

Left: Stothard's 1790 realisation of another significant meeting at the end of the first book, Robinson Crusoe and Friday making a tent to lodge Friday's father and the Spaniard (Chapter XVI, "Rescue of the Prisoners from the Cannibals," copper-engraving). Centre: In the children's book illustration, the Captain offers Crusoe his ship without any reference to quelling the mutiny first, The Captain offers a Ship to Robinson Crusoe. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Above: George Cruikshank somewhat theatrical wood-engraving of the same moment in the narrative, Crusoe and Friday encounter the captain of a British ship whose crew have mutinied. (1831) [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Above: The Cassell's house-artist's realistic wood-engraving of the same moment in the narrative, with the Captain and his men in civilian dress, suggesting theirs is a merchant-ship: >Crusoe discovers Himself to the English Captain. (1863-64) [Click on image to enlarge it.]

Many thanks for the assistance of the staff at Special Collections and University Archives, particularly John Frederick, Library Assistant, McPherson Library, University of Victoria, British Columbia, Canada.

Reference

Defoe, Daniel (adapted). The Wonderful Life and Surprising Adventures of that Renowned Hero, Robinson Crusoe: who lived twenty-eight years on an uninhabited island, which he afterwards colonized.. London: W. Darton, 1815.

Last modified 22 February 2018