"Knitting" by Harry Furniss — sixteenth illustration for "A Tale of Two Cities" (1910) (original) (raw)

Passage Illustrated

. . . when Sunday came, the mender of roads was not enchanted (though he said he was) to find that madame was to accompany monsieur and himself to Versailles. It was additionally disconcerting to have madame knitting all the way there, in a public conveyance; it was additionally disconcerting yet, to have madame in the crowd in the afternoon, still with her knitting in her hands as the crowd waited to see the carriage of the King and Queen.

"You work hard, madame," said a man near her.

"Yes," answered Madame Defarge; "I have a good deal to do."

"What do you make, madame?"

"Many things."

"For instance —"

"For instance," returned Madame Defarge, composedly, "shrouds." [Book Two, "The Golden Thread," Chapter Fifteen, "Knitting," 163: the picture's original caption has been emphasized]

Commentary

The illustration reiterates the inscrutable Moira figure of Madame Defarge, calculating and implacable as she minutely records the transgressions of the upper class. Fifty pages earlier, she appears, recalling her textual appearance in Book Two, Chapter Seven, among the women at the base of the fountain in Saint Antoine. Here, however, she sits in a chair, presumably behind the counter of the wine-shop, looking squarely at the reader, as confidently and penetratingly as she examines the spy, John Barsad, in whose position Furniss has apparently placed the reader.

Previously, in The Fountain — An Allegory, Furniss has depicted Madame Defarge was the patient but implacable spinner of lives marked for termination, Clotho; here, Dickens prepares us for her enacting at the Bastille the roles of the other two Greco-Roman Fates or Parcae: Lachesis, the apportioner of the thread of life (to which Dickens obliquely but repeatedly alludes in the title of the second book, "The Golden Thread"), and Atropos, the merciless severer of that thread.

Although the previous illustrators have all given prominence to the figure of Madame Therèse Defarge as the patient spider, laying her web methodically against the day when she will ensnare and annihilate her enemies, Furniss's point of departure is clearly the inscrutable knitter in Phiz's The Wine-shop(see below), in which the Defarges without apparent anxiety entertain the royalist spy, Barsad, unperturbed (at least outwardly) by the questions of an agent who could arbitrarily consign them to a political prison. But whereas Phiz's publican does not pause to look up from her needle-work for even an instant (despite the fact that she is checking her prior recording of the spy's appearance), in Furniss's she visually examines the reader. Her scrutiny suggests that Furniss regards her as a type of writer, for her knitting, paralleling Doctor Manette's testimony found in the Bastille, will serve as the basis for condemning the enemies of the new republic to the guillotine.

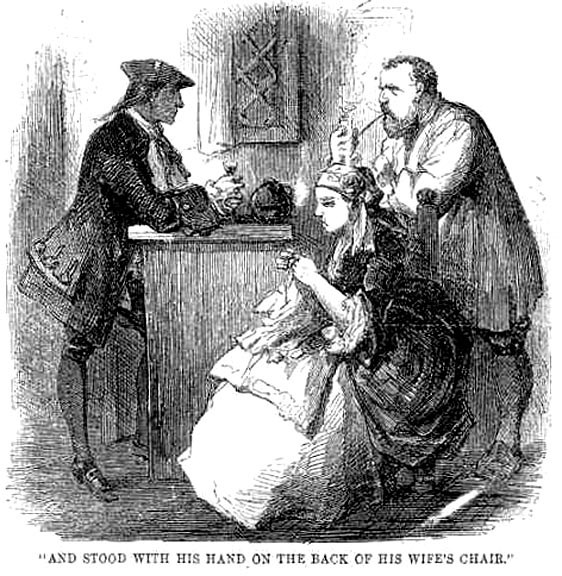

The fifteenth weekly instalment in Harper's, issued on the 13th of August 1859, features John McLenan's less animated and detailed realisation of the scene in the wine-shop, And stood with his hand on the back of his wife's chair (see below) for Book Two, Chapter Sixteen, "Still Knitting." Proleptically, in fact, Furniss's illustration, although situated in Chapter Fifteen ("Knitting"), alludes through its caption to a later scene which anticipates the arrival of the spy. Readers of the serial published in theAll the Year Roundweekly numbers had no such visual reinforcement of these themes; only the purchasers of the monthly parts had the benefit of the Phizsteel-engraving The Wine-shop (see below: Part Four, September 1859), in which the emphasis is clearly on the knitting madame, whereas McLenan's scene has a divided focus since the caption points to Defarge as the principal figure, whereas the illustration itself places Madame Defarge at its centre. Fred Barnard, on the other hand, in his version of The Wine-shop (see below) seems far more interested in the three "Jacques" opposite the placid proprietess, who has laid her knitting aside to pick her teeth — and to drink in all that her customers have to say, while (suspicious of a pair of unfamiliar customers who have just entered) she commits herself to no words whatsoever in Book One, Chapter Five, "The Wine-sho" Dickens develops the character whom he introduced in the opening book as "stout" and "watchful" — Furniss, like Phiz, communicates the watchfulness, but opts for a more petite and feminine figure than Dickens suggests in the following passage, which seems to be the basis of Barnard's description of her.

Madame Defarge, his wife, sat in the shop behind the counter as he came in. Madame Defarge was a stout woman of about his own age, with a watchful eye that seldom seemed to look at anything, a large hand heavily ringed, a steady face, strong features, and great composure of manner. There was a character about Madame Defarge, from which one might have predicated that she did not often make mistakes against herself in any of the reckonings over which she presided. Madame Defarge being sensitive to cold, was wrapped in fur, and had a quantity of bright shawl twined about her head, though not to the concealment of her large earrings. [Book One, "Recalled to Life," Chapter Five, "The Wine-shop," 29]

Furniss's Therèse Defarge, like Phiz's, is neither crone nor Weird Sister, but a demurely clad bourgeois minding her shop and engaged in a particularly feminine pursuit — knitting. However, as the dialogue reveals, her object is not to manufacture baby-clothes, but shrouds for the corpses of the enemies of the people. Furniss and his editor, J. A. Hammerton, however, have juxtaposed the picture of the respectable, middle-class matron with the passage in which the road-mender describes the execution of the patriot, who has executed Nemesis on the brutal Marquis. At the bottom of the facing page, the entire line of the Evrémondes is "registered, as doomed to destruction" (161), so that the illustration does triple duty, alluding to Madame Defarge's earlier appearances, preparing us for her interview with the spy in Chapter Sixteen, and underscoring her importance as the record-keeper of the Jacquerie and the avenging spirit of the people, and of her family.

Presumably what she is "recording" in this illustration, named for the succeeding chapter, is not the annihilation of the aristocratic line that includes Charles Darnay, but the description of the latest police spy, just conveyed to her by the Jacquerie's mole at police headquarters:

"Say then, my friend; what did Jacques of the police tell thee?"

"Very little to-night, but all he knows. There is another spy commissioned for our quarter. There may be many more, for all that he can say, but he knows of one."

"Eh well!" said Madame Defarge, raising her eyebrows with a cool business air. "It is necessary to register him. How do they call that man?"

"He is English."

"So much the better. His name?"

"Barsad," said Defarge, making it French by pronunciation. But, he had been so careful to get it accurately, that he then spelt it with perfect correctness.

"Barsad," repeated madame. "Good. Christian name?"

"John."

"John Barsad," repeated madame, after murmuring it once to herself. "Good. His appearance; is it known?"

"Age, about forty years; height, about five feet nine; black hair; complexion dark; generally, rather handsome visage; eyes dark, face thin, long, and sallow; nose aquiline, but not straight, having a peculiar inclination towards the left cheek; expression, therefore, sinister."

"Eh my faith. It is a portrait!" said madame, laughing. "He shall be registered to-morrow." [Book Two, "The Golden Thread," Chapter Sixteen, "Still Knitting," 166]

Shortly in Furniss's sequence we shall meet the spy thus delineated, although Furniss will not present him in the context of the wine-shop, and indeed his is one of the few Furniss images not accompanied by any sort of explanatory quotation, other than that the artist and editor suggest that his name, appearing in quotation marks, is an alias.

Related Materials

- A Tale of Two Cities(1859) — the last Dickens's novel "Phiz" Illustrated

- Costume Notes on A Tale of Two Cities

- List of Plates by Phiz for the 1859 Monthly Instalments

- John McLenan's Illustrations for Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities (1859)

- Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s Diamond Edition Eight Illustrations for A Tale of Two Cities (1867)

- 25 Illustrations for Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities by Fred Barnard (1874)

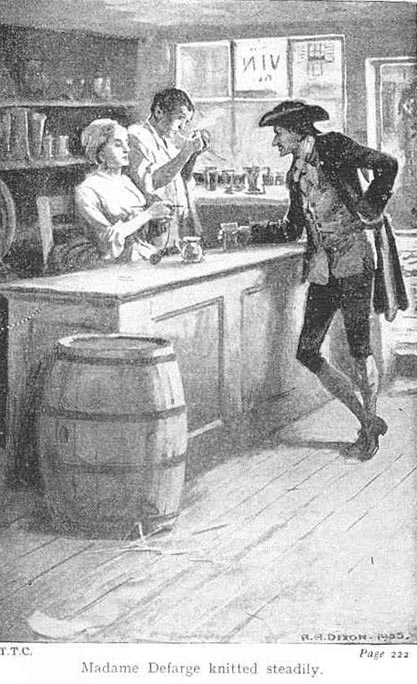

- A. A. Dixon's Illustrations for the Collins Pocket Edition of A Tale of Two Cities (1905)

Relevant Illustrations from earlier editions, 1859, 1867, 1874, and 1905.

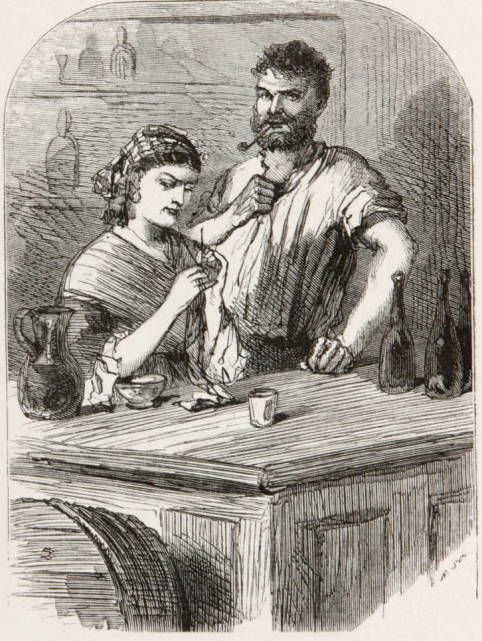

Above: Phiz's The Wine-shop (September 1859).

Above: Barnard's Still, the Doctor, with shaded forehead, beat his foot nervously on the ground (1874).

Left: McLenan's version of Phiz's illustration of Barsad in the wine-shop, And stood with his hand on the back of his wife's chair. Middle: Eytinge's dual character study of the would-be avengers of the past wrongs of the Old Regime, Monsieur and Madame Defarge (1867). Right: Dixon's wine-shop proprietors coolly assess the government spy in Madame DeFarge knitted steadily (1905).

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. , 1988.

Bolton, H. Phili "A Tale of Two Cities." Dickens Dramatized. Boston: G. K. Hall, 1987, 395-412.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Pilgrim Edition of the Letters of Charles Dickens. Ed. Madeline House, Graham Storey, and Kathleen Tillotson. Oxford: Clarendon, 1974. IX (1859-61).

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. All the Year Round. 30 April through 26 November 1859.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by John McLenan. Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization. 7 May through 3 December 1859.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ('Phiz'). London: Chapman and Hall, 1859.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities andGreat Expectations. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. 16 vols. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1874.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by A. A. Dixon. London: Collins, 1905.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities, American Notes, and Pictures from Italy. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. 13.

Mengel, Ewald. "The Poisoned Fountain: Dickens's Use of a Traditional Symbol in A Tale of Two Cities." Dickensian, 80/1 (Spring 1984): 26-32.

Sanders, Andrew. A Companion to "A Tale of Two Cities." London: Unwin Hyman, 1988.

Created 3 January 2014

Last modified 8 January 2020