Exploring similarities and differences between Toxoplasma gondii and Neospora caninum infections in dogs (original) (raw)

Abstract

Toxoplasma gondii and Neospora caninum infections in dogs are predominantly manifest asymptomatic. However, these infections can also present highly varied and potentially severe clinical signs. This is due to the parasites’ ability to replicate in a number of cell types within the host organism, with N. caninum exhibiting a particular tropism for the central and peripheral nervous systems, and T. gondii targeting the central nervous system and musculature. In clinical practice, toxoplasmosis and neosporosis are often considered to be closely related diseases, despite their distinct epidemiological, clinical, diagnostic, and therapeutic characteristics. The present review analyses the similarities and differences between these two protozoan infections, since an accurate and timely aetiological diagnosis is essential for establishing effective therapeutic protocols and control strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Toxoplasma gondii and Neospora caninum are two obligate intracellular parasites belonging to the phylum Apicomplexa and the order Eucoccidiorida. Unlike the correctly defined coccidia (e.g. Cystoisospora canis, Cystoisospora ohioensis complex), they are not included in the aetiological agents capable of causing enteritis in dogs. In fact, their clinical impact is not related to the intestinal development phase (present only in N. caninum), but rather to the extraintestinal phase that develops in multiple organs, with elective tropism for the nervous system (Black and Boothroyd [2000](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR17 "Black MW, Boothroyd JC (2000) Lytic cycle of Toxoplasma gondii. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 64:607–23. https://doi.org/10.1128/mmbr.64.3.607-623.2000

"); Dubey et al. [2007](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR44 "Dubey JP, Barr BC, Barta JR, Bjerkås I, Björkman C, Blagburn BL, Bowman DD, Buxton D, Ellis JT, Gottstein B, Hemphill A, Hill DE, Howe DK, Jenkins MC, Kobayashi Y, Koudela B, Marsh AE, Mattsson JG, McAllister MM, Modrý D, Omata Y, Sibley LD, Speer CA, Trees AJ, Uggla A, Upton SJ, Williams DJ, Lindsay DS (2002) Redescription of Neospora caninum and its differentiation from related coccidia. Int J Parasitol 32:929–946.

https://doi.org/10.1016/s0020-7519(02)00094-2

")).Both parasites play an important role in veterinary medicine. They are responsible for serious clinical conditions that affect a wide range of animal species, and primarily ruminants. T. gondii is considered one of the main abortigenic pathogens of small ruminants and can also cause extremely serious diseases in other domestic (e.g. cats and dogs) and wild (e.g. marine mammals, hares) species, leading to severe forms of encephalitis with a high fatality rate (Dubey et al. [2004](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR43 "Dubey JP, Schares G (2011) Neosporosis in animals -- the last five years. Vet Parasitol 180:90–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.05.031

")).Neospora caninum is also the most important abortigenic protozoa on dairy cattle farms worldwide. It is increasingly impacting small ruminants (sheep and goats), potentially causing a significant miscarriage rate (Rodrigues et al. [2020](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR105 "Rodrigues AA, Reis SS, Sousa ML, Moraes EDS, Garcia JL, Nascimento TVC, Cunha IALD (2020) A systematic literature review and meta-analysis of risk factors for Neospora caninum seroprevalence in goats. Prev Vet Med 185:105176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2020.105176

"); Romanelli et al. [2021](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR106 "Romanelli PR, Caldart ET, Martins FDC, Martins CM, de Matos AMRN, Pinto-Ferreira F, Mareze M, Mitsuka-Breganó R, Freire RL 1, Navarro IT (2021) Seroprevalence and associated risk factors of ovine neosporosis worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin Cienc Agrar 42:2111–2126.

https://doi.org/10.5433/1679-0359.2021v42n3Supl1p2111

")) and in alpaca (Serrano-Martínez et al. [2007](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR113 "Serrano-Martínez E, Collantes-Fernández E, Chávez-Velásquez A, Rodríguez-Bertos A, Casas-Astos E, Risco-Castillo V, Rosadio-Alcantara R, Ortega-Mora LM (2007) Evaluation of Neospora caninum and Toxoplasma gondii infections in alpaca (Vicugna pacos) and lama (Lama glama) aborted foetuses from Peru. Vet Parasitol 150:39–45.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2007.08.048

")). _T. gondii_ also plays a significant role in public health as it is a zoonotic agent of major concern (Dini et al. [2023](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR37 "Dini FM, Stancampiano L, Poglayen G, Galuppi R (2024) Risk factors for Toxoplasma gondii infection in dogs: a serological survey. Acta Vet Scand 66(1):14.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s13028-024-00734-0

")).In addition to the clinical disorders associated with these infections, dogs contribute to the transmission and dissemination of both parasites in nature, becoming part of their epidemiological circuit in various ways, such as acting as predators for T. gondii or as vectors for the resistant forms of N. caninum.

This review compares T. gondii and N. caninum infections in dogs. These two diseases are often considered to be closely related in clinical settings. However, they exhibit numerous distinct epidemiological, clinical, diagnostic, and therapeutic response characteristics which should be clearly differentiated to support timely diagnosis and to establish effective therapeutic protocols and control strategies.

Morphobiological aspects and routes of transmission

Toxoplasma gondii and N. caninum are two facultative heteroxenous parasites with particular biological cycles and several routes of transmission. Both parasites exhibit definitive and intermediate hosts at the same time (defined as complete host), harbouring both the sexual and asexual phases of the cycle, and they have also a wide range of alternative intermediate hosts.

Domestic cats (Felis catus) and numerous wild cats are recognised as definitive/complete hosts of T. gondii, and numerous domestic and wild animals are intermediate hosts (more than 200 species among mammals and birds), including dogs and humans (Hill et al. [2005](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR62 "Hill DE, Chirukandoth S, Dubey JP (2005) Biology and epidemiology of Toxoplasma gondii in man and animals. Anim Heal Res Rev 6:41–61. https://doi.org/10.1079/ahr2005100

"); Al-Malki [2021](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR3 "Al-Malki ES (2021) Toxoplasmosis: stages of the protozoan life cycle and risk assessment in humans and animals for an enhanced awareness and an improved socio-economic status. Saudi J Biol Sci 28:962–969.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2020.11.007

")). _Neospora caninum_ has a more limited spectrum of intermediate hosts, consisting of wild ruminants (e.g. cervids) and domestic ruminants, camelids, equids and rodents. The domestic dog (_Canis familiaris_) and some wild canids, such as dingo (_Canis lupus_) and coyote (_Canis latrans_), are definitive and complete hosts (Cedillo et al. [2008](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR27 "Cedillo CJR, Martínez MJJ, Santacruz AM, Banda RVM, Morales SE (2008) Models for experimental infection of dogs fed with tissue from fetuses and neonatal cattle naturally infected with Neospora caninum. Vet Parasitol 154:151–155.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.02.025

")).Neospora caninum and T. gondii show the same biological and infection stages (i.e. oocysts, bradyzoites and tachyzoites), as well as very similar routes of transmission. However, they also have some distinctive features which are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1 Transmission routes differences between Neospora caninum and Toxoplasma gondii in dogs

Oocysts, defined as _Cystoisospora_-like due to their internal arrangement in two sporocysts each containing four sporozoites, are the small elements that the definitive host spreads in the environment through faeces and are responsible for transmission via the faecal-oral route. The oocysts shed are not directly infectious, and sporulate rapidly in the external environment within 24–72 h. Tachyzoites are the rapidly replicating morphotypes that spread during the acute phase of infection through the body of the intermediate hosts, including dogs. They are able to colonize any metabolically active cell (e.g. neurons, macrophages, hepatocytes, fibroblasts, muscle fibre cells, vessel endothelium cells, renal tubular epithelium cells, etc.) and show elective affinity for highly vascularized organs where parasite clusters at the pseudocyst stage.

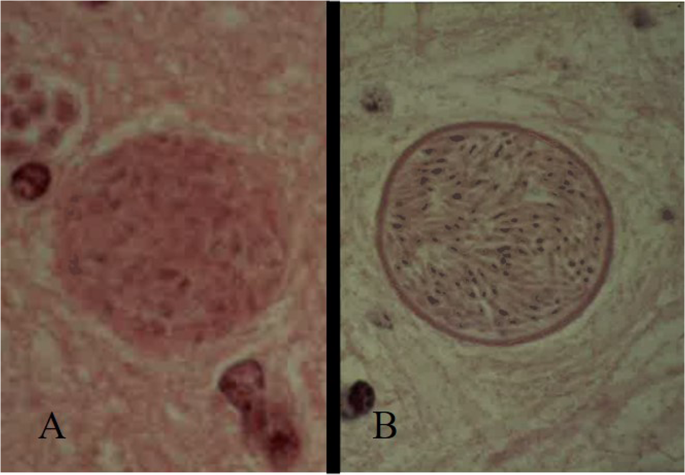

Bradyzoites replicate slowly and are typical of the chronic phase of infection, which develop within tissue cysts reaching the size of 70–100 μm at full development (within three months after infection). The thickness of the wall differs between the two parasites, which is thicker in N. caninum (1–4 μm), then in T. gondii (< 0.5 μm) (Dubey et al. [2002](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR42 "Dubey JP, Lindsay DS (1996) A review of Neospora caninum and neosporosis. Vet Parasitol 67:1–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-4017(96)01035-7

")) (Fig. [1](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#Fig1)). The cysts develop in anatomical sites that are hard to access immunologically. In the case of _N. caninum_, they develop exclusively in the neural tissues, whereas in the case of _T. gondii_ cysts can be found in many organs, including voluntary and involuntary striated muscles. Under conditions of immunosuppression or certain physiological situations (e.g. pregnancy), the cysts may rupture, releasing the bradyzoites, which replicate rapidly as tachyzoites and spread through the blood to the placenta and _foetus_ (in same species) and in other organs (Silva and Machado [2016](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR116 "Silva DAO, Lobato J, Mineo TWP, Mineo JR (2007) Evaluation of serological tests for the diagnosis of Neospora caninum infection in dogs: optimization of cut off titers and inhibition studies of cross-reactivity with Toxoplasma gondii. Vet Parasitol 143:234–244.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.08.028

"); Sanchez and Besteiro [2021](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR111 "Sanchez SG, Besteiro S (2021) The pathogenicity and virulence of Toxoplasma gondii. Virulence 12:3095–3114.

https://doi.org/10.1080/21505594.2021.2012346

")).Fig. 1

Tissue cysts of Toxoplasma gondii (A) and Neospora caninum (B). The wall is thicker in N. caninum (1–4 μm), then in T. gondii (< 0.5 μm)

The reactivation skills of the chronic phases of the infection are different for T. gondii and N. caninum. After the first infection, in fact T. gondii can evoke a fully protective interferon-γ mediated immunity, which may be broken only in rare cases following extremely serious and immunosuppressive underlying diseases (e.g. canine distemper virus or leishmaniosis) (Moretti et al. [2006](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR88 "Moretti LD, Da Silva AV, Ribeiro MG, Paes AC, Langoni H (2006) Toxoplasma gondii genotyping in a dog co-infected with distemper virus and ehrlichiosis rickettsia. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo 48:359–363. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0036-46652006000600012

")). On the other hand, _N. caninum_ can be reactivated easily, even after hormonal disorders that are physiologically related to the oestrous cycle (Silva and Machado [2016](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR116 "Silva DAO, Lobato J, Mineo TWP, Mineo JR (2007) Evaluation of serological tests for the diagnosis of Neospora caninum infection in dogs: optimization of cut off titers and inhibition studies of cross-reactivity with Toxoplasma gondii. Vet Parasitol 143:234–244.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.08.028

")).Concerning the routes of transmission, both N. caninum and T. gondii can be transmitted from the definitive host to an intermediate host and vice-versa through a faecal-oral and prey-predator circuit, respectively. They can also be transmitted from an intermediate host to another intermediate host through carnivorism and from a definitive host to another definitive host by contaminated food or water containing oocysts (Silva and Machado [2016](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR116 "Silva DAO, Lobato J, Mineo TWP, Mineo JR (2007) Evaluation of serological tests for the diagnosis of Neospora caninum infection in dogs: optimization of cut off titers and inhibition studies of cross-reactivity with Toxoplasma gondii. Vet Parasitol 143:234–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.08.028

"); Sanchez and Besteiro [2021](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR111 "Sanchez SG, Besteiro S (2021) The pathogenicity and virulence of Toxoplasma gondii. Virulence 12:3095–3114.

https://doi.org/10.1080/21505594.2021.2012346

")).In dogs, T. gondii and N. caninum infection are acquired via three routes of transmission: (i) ingestion of sporulated oocysts present in the soil and which contaminate food and water; (ii) ingestion of tissue cysts containing bradyzoites through the consumption of raw or undercooked meat or as a result of predation; (iii) transmission of tachyzoites through the placenta (Dubey [2008](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR45 "Dubey JP, Lipscomb TP, Mense M (2004) Toxoplasmosis in an elephant seal (Mirounga angustirostris). J Parasitol 90:410–411. https://doi.org/10.1645/ge-155r

"); King et al. [2011](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR69 "King JS, Jenkins DJ, Ellis JT, Fleming P, Windsor PA, Šlapeta J (2011) Implications of wild dog ecology on the sylvatic and domestic life cycle of Neospora caninum in Australia. Vet J 188:24–33.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tvjl.2010.03.002

")). These routes of transmission have different frequencies in dogs: _T. gondii_ is acquired mainly horizontally, through predation, while _N. caninum_ is mainly transmitted vertically, through the maternal-foetal lineage (Barber and Trees [1998](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR9 "Barber JS, Trees AJ (1998) Naturally occurring vertical transmission of Neospora caninum in dogs. Int J Parasitol 28:57–64.

https://doi.org/10.1016/s0020-7519(97)00171-9

"); Machacova et al. [2016](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR77 "Machacova T, Bartova E, Sedlak K, Slezakova R, Budikova M, Piantedosi D, Veneziano V (2016) Seroprevalence and risk factors of infections with Neospora caninum and Toxoplasma gondii in hunting dogs from Campania region, southern Italy. Folia Parasitol (Praha) 63:2016012.

https://doi.org/10.14411/fp.2016.012

")).Epidemiology and risk factors

Toxoplasma gondii and N. caninum infections are found globally in dog populations, with variable prevalence rates according to the sample population, the risk factors considered and the accuracy of the diagnostic tests used (Dubey et al. [2020](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR49 "Dubey JP, Murata FHA, Cerqueira-Cézar CK, Kwok OCH, Yang Y, Su C (2020) Toxoplasma gondii infections in dogs: 2009–2020. Vet Parasitol 31:287:109223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2020.109223

")). Recent data available on _T. gondii_ and _N. caninum_ seroprevalence in dogs in various parts of the world may thus diverge (Tables [2](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#Tab2) and [3](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#Tab3)).Table 2 Trends in Toxoplasma gondii prevalence in dogs over the past 20 years

Table 3 Trends in Neospora caninum prevalence in dogs over the past 20 years

The seroprevalence of T. gondii increases with the age of the animals, due to exposure over time to potential horizontal routes of infection (e.g. faecal-oral contamination and predatory activity). The habitat and type of diet administered are considered as risk factors. Working dogs (e.g. hunting dogs) in wild environments or those living in rural or semirural areas are exposed to a greater extent, since they are most likely to carry out predatory activities (Lopes et al. [2011](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR74 "Lopes AP, Santos H, Neto F, Rodrigues M, Kwok OC, Dubey JP, Cardoso L (2011) Prevalence of antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii in dogs from northeastern Portugal. J Parasitol 97:418–420. https://doi.org/10.1645/ge-2691.1

"); Cano-Terriza et al. [2016](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR23 "Cano-Terriza D, Puig-Ribas M, Jiménez-Ruiz S, Cabezón Ó, Almería S, Galán-Relaño Á, Dubey JP, García-Bocanegra I (2016) Risk factors of Toxoplasma gondii infection in hunting, pet and watchdogs from southern Spain and northern Africa. Parasitol Int 65:363–366.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parint.2016.05.001

")). In addition, animals fed with raw meat or household food are considered at risk (Ali et al. [2003](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR4 "Ali CN, Harris JA, Watkins JD, Adesiyun AA (2003) Seroepidemiology of Toxoplasma gondii in dogs in Trinidad and Tobago. Vet Parasitol 113:179–187.

https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-4017(03)00075-x

"); Lopes et al. [2011](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR74 "Lopes AP, Santos H, Neto F, Rodrigues M, Kwok OC, Dubey JP, Cardoso L (2011) Prevalence of antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii in dogs from northeastern Portugal. J Parasitol 97:418–420.

https://doi.org/10.1645/ge-2691.1

")). Cohabiting with cats that live in semi-freedom may be also considered a risk factor, above all for dogs exhibiting coprophagia behaviour (Dini et al. [2024](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR36 "Dini FM, Morselli S, Marangoni A, Taddei R, Maioli G, Roncarati G, Balboni A, Dondi F, Lunetta F, Galuppi R (2023) Spread of Toxoplasma gondii among animals and humans in Northern Italy: a retrospective analysis in a one-health framework. Food Waterborne Parasitol 32:e00197.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fawpar.2023.e00197

")).Regarding the morbidity of T. gondii infection, an extremely important factor is the presence of viral or bacterial coinfections (e.g. canine distemper virus, Ehrlichia canis) (Headley et al. [2013](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR61 "Headley SA, Alfieri AA, Fritzen JT, Garcia JL, Weissenböck H, da Silva AP, Bodnar L, Okano W, Alfieri AF (2013) Concomitant canine distemper, infectious canine hepatitis, canine parvoviral enteritis, canine infectious tracheobronchitis, and toxoplasmosis in a puppy. J Vet Diagn Invest 25:129–135. https://doi.org/10.1177/1040638712471344

"); Cardinot et al. [2016](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR25 "Cardinot CB, Silva JE, Yamatogi RS, Nunes CM, Biondo AW, Vieira RF, Junior JP, Marcondes M (2016) Detection of Ehrlichia canis, Babesia vogeli and Toxoplasma gondii DNA in the brain of dogs naturally infected with Leishmania infantum. J Parasitol 102:275–279.

https://doi.org/10.1645/15-821

")) that have an immunosuppressive effect. In fact, dogs rarely manifest clinical signs of primary toxoplasmosis, but more frequently show secondary reactivation forms in adult animals (Webb et al. [2005](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR128 "Webb JA, Keller SL, Southorn EP, Armstrong J, Allen DG, Peregrine AS, Dubey JP (2005) Cutaneous manifestations of disseminated toxoplasmosis in an immunosuppressed dog. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 41:198–202.

https://doi.org/10.5326/0410198

")).N. caninum seropositivity rates do not increase significantly with the age of the animals, supporting the hypothesis that the ingestion of sporulated oocysts is not so important in the epidemiological circuits as their elimination is extremely rare and mostly only demonstrated experimentally (Dubey and Schares [2011](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR47 "Dubey JP, Lindsay DS, Lappin MR (2009) Toxoplasmosis and other Intestinal Coccidial infections in cats and dogs. Vet Clin North Am - Small Anim Pract 39:1009–1034. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cvsm.2009.08.001

")). Young animals (i.e. puppies) are more susceptible to _N. caninum_, since vertical transmission is more prevalent than in _T. gondii_. Infection is more common in some breeds (e.g. German Shepherd, Alsatian, Labrador, Golden Retriever, Basset Hound and Greyhound), which is not related to a real genetic predisposition, but to the establishment of infected maternal-filial lines on breeding farms (Dubey et al. [2009](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR46 "Dubey JP, Schares G, Ortega-Mora LM (2007) Epidemiology and control of neosporosis and Neospora caninum. Clin Microbiol Rev 20:323–367.

https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00031-06

")).Dogs on dairy farms are considered to be at high risk, because they may ingest placental and aborted foetuses containing the parasite, as well as animals with an outdoor lifestyle prone to predatory activities. In general, all animals that could potentially ingest tissues of intermediate hosts containing pseudocysts and cysts are considered at neosporosis risk (Paradies et al. [2007](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR96 "Paradies P, Capelli G, Testini G, Cantacessi C, Trees AJ, Otranto D (2007) Risk factors for canine neosporosis in farm and kennel dogs in southern Italy. Vet Parasitol 145:240–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.12.013

"); Dubey et al. [2009](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR46 "Dubey JP, Schares G, Ortega-Mora LM (2007) Epidemiology and control of neosporosis and Neospora caninum. Clin Microbiol Rev 20:323–367.

https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00031-06

")).The epidemiological role that dogs play in the transmission of T. gondii is more marginal than that of cats because they do not act as a definitive host, and they are unlikely to be preyed upon. However, dogs can act as mechanical carriers of T. gondii oocysts, excreting them in their faeces after ingestion from cat stools (Schares et al. [2005](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR112 "Schares G, Pantchev N, Barutzki D, Heydorn, Bauer C, Conraths (2005) Oocysts of Neospora caninum, Hammondia heydorni, Toxoplasma gondii and Hammondia hammondi in faeces collected from dogs in Germany. Int J Parasitol 35:1525–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpara.2005.08.008

")). Moreover, _T. gondii_ oocysts can contaminate dog fur, potentially leading to human infection through contact with the dog’s coat, mouth, and feet (Lindsay et al. [1997](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR73 "Lindsay DS, Dubey JP, Butler JM, Blagburn BL (1997) Mechanical transmission of Toxoplasma gondii oocysts by dogs. Vet Parasitol. 15;73(1–2):27–33.

https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-4017(97)00048-4

"); Dubey et al. [2020](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR49 "Dubey JP, Murata FHA, Cerqueira-Cézar CK, Kwok OCH, Yang Y, Su C (2020) Toxoplasma gondii infections in dogs: 2009–2020. Vet Parasitol 31:287:109223.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2020.109223

")). In contrast, through the elimination of oocysts of _N. caninum_, the dog is considered as the main animal responsible for the outbreak of high-prevalence abortions (i.e. abortion storms) on dairy farms (Bartels et al. [1999](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR12 "Bartels CJM, Wouda W, Schukken YH (1999) Risk factors for Neospora caninum-associated abortion storms in dairy herds in the Netherlands (1995 to 1997). Theriogenology 52:247–257.

https://doi.org/10.1016/s0093-691x(99)00126-0

")).Regarding the potential zoonotic transmission of T. gondii, symptomatic dogs, especially those with respiratory forms, may act as a source of infection for humans. This can occur through the sputum containing tachyzoites, which can penetrate damaged skin or mucous membranes of people handling them (e.g. veterinary surgeons performing medical or necropsy procedures) or those in close contact with them (Tenter et al. [2000](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR120 "Tenter AM, Heckeroth AR, Weiss LM (2000) ToxopGondiigondii: from animals to humans. Int J Parasitol 31:217–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0020-7519(00)00124-7

")). In contrast, dogs do not seem to show a zoonotic risk for humans concerning _N. caninum_, as no zoonotic value has been confirmed to date. However, some reports have shown varying degrees of human exposure to _N. caninum_ through antibody assays (Tranas et al. [1999](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR121 "Tranas J, Heinzen RA, Weiss LM, McAllister MM (1999) Serological evidence of human infection with the protozoan Neospora caninum. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 6:765–767.

https://doi.org/10.1128/cdli.6.5.765-767.1999

"); Duarte et al. [2020](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR40 "Duarte PO, Oshiro LM, Zimmermann NP, Csordas BG, Dourado DM, Barros JC, Andreotti R (2020) Serological and molecular detection of Neospora caninum and Toxoplasma gondii in human umbilical cord blood and placental tissue samples. Sci Rep 10:9043.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-65991-1

")). Additionally, experimental studies have demonstrated possible vertical transmission in non-human primates, resulting in fatal encephalitis that resembles that induced by _T. gondii_ (Barr et al. [1994](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR11 "Barr BC, Conrad PA, Sverlow KW, Tarantal AF, Hendrickx AG (1994) Experimental fetal and transplacental Neospora infection in the nonhuman primate. Lab Investig J Tech Methods Pathol 71:236–242")).Pathogenesis and clinical expression

Toxoplasma gondii and N. caninum infections in dogs evolve mainly in an asymptomatic form. However, when clinical manifestations occur, morbidity and mortality rates depend on several factors, primarily the animal’s age and immune status. Additionally, the transmission route (vertical versus horizontal) and the stage of infection (acute, chronic, or reactivation) are significant determinants (Carruthers and Suzuki [2007](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR26 "Carruthers VB, Suzuki Y (2007) Effects of Toxoplasma gondii infection on the brain. Schizophr Bull 33:745–751. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbm008

"); Dubey et al. [2009](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR46 "Dubey JP, Schares G, Ortega-Mora LM (2007) Epidemiology and control of neosporosis and Neospora caninum. Clin Microbiol Rev 20:323–367.

https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00031-06

"); Swinger et al. [2009](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR119 "Swinger RL, Schmidt KA Jr, Dubielzig RR (2009) Keratoconjunctivitis associated with Toxoplasma gondii in a dog. Vet Ophthalmol 12:56–60.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-5224.2009.00675.x

")). As observed in other species, including humans and rodents, the severity of the disease and the various clinical presentations in dogs may also correlate with the infectious dose. No evidence currently exists on a possible correlation between parasite lineage and clinical forms in either _T. gondii_ or _N. caninum_ (Calero-Bernal and Gennari [2019](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR21 "Calero-Bernal R, Gennari SM (2019) Clinical toxoplasmosis in dogs and cats: an update. Front Vet Sci 6:54.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2019.00054

")).Acquired acute forms related to post-natal primary infection (more common in T. gondii than in N. caninum), reactivation chronic forms and congenital forms have been described (Dubey and Lindsay [1996](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR41 "Dubey JP (2008) The history of Toxoplasma gondii -- the first 100 years. J Eukaryot Microbiol 55:467–475. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1550-7408.2008.00345.x

"); Montoya and Liesenfeld [2004](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR87 "Montoya JG, Liesenfeld O (2004) Toxoplasmosis. Lancet 363:1965–1976.

https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(04)16412-x

")).During the acute phase of infection, T. gondii and N. caninum exhibit pathogenic effects through active invasion and replication at the multiorgan intracellular level by tachyzoites. This phase is characterized by cell lysis and subsequent inflammatory and necrotic processes. In contrast, the chronic phase is characterized by general inactivity of both the immune system and organ responses to the parasites. Bradyzoites are located in tissue cysts within the central and peripheral nervous system for N. caninum, and in the CNS and muscles for T. gondii, without causing damage. Reactivation occurs when there is an immune breakdown due to immunosuppressive conditions, which can lead to renewed local replication of tachyzoites, potentially resulting in severe organ damage or, more rarely, systemic dissemination (Silva and Machado [2016](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR116 "Silva DAO, Lobato J, Mineo TWP, Mineo JR (2007) Evaluation of serological tests for the diagnosis of Neospora caninum infection in dogs: optimization of cut off titers and inhibition studies of cross-reactivity with Toxoplasma gondii. Vet Parasitol 143:234–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.08.028

"); Sanchez and Besteiro [2021](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR111 "Sanchez SG, Besteiro S (2021) The pathogenicity and virulence of Toxoplasma gondii. Virulence 12:3095–3114.

https://doi.org/10.1080/21505594.2021.2012346

")).Additionally, congenital clinical disorders can occur when tachyzoites cross the placental barrier and replicate at the multiorgan level in the foetus (Silva and Machado [2016](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR116 "Silva DAO, Lobato J, Mineo TWP, Mineo JR (2007) Evaluation of serological tests for the diagnosis of Neospora caninum infection in dogs: optimization of cut off titers and inhibition studies of cross-reactivity with Toxoplasma gondii. Vet Parasitol 143:234–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.08.028

"); Sanchez and Besteiro [2021](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR111 "Sanchez SG, Besteiro S (2021) The pathogenicity and virulence of Toxoplasma gondii. Virulence 12:3095–3114.

https://doi.org/10.1080/21505594.2021.2012346

")).The clinical conditions most associated with toxoplasmosis and neosporosis in dogs include peripheral and central neurological disorders, reproductive illnesses, dermatological problems and systemic disorders (Ruehlmann et al. [1995](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR108 "Ruehlmann D, Podell M, Oglesbee M, Dubey JP (1995) Canine neosporosis: a case report and literature review. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 31:174–183. https://doi.org/10.5326/15473317-31-2-174

"); Dubey and Lindsay [1996](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR41 "Dubey JP (2008) The history of Toxoplasma gondii -- the first 100 years. J Eukaryot Microbiol 55:467–475.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1550-7408.2008.00345.x

"); Dubey et al. [2009](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR46 "Dubey JP, Schares G, Ortega-Mora LM (2007) Epidemiology and control of neosporosis and Neospora caninum. Clin Microbiol Rev 20:323–367.

https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00031-06

"); Calero-Bernal and Gennari [2019](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR21 "Calero-Bernal R, Gennari SM (2019) Clinical toxoplasmosis in dogs and cats: an update. Front Vet Sci 6:54.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2019.00054

"); Barker et al. [2021](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR10 "Barker A, Wigney D, Child G, Šlapeta J (2021) Seroprevalence of Neospora caninum in dogs from greater Sydney, Australia unchanged from 1997 to 2019 and worldwide review of adult-onset of canine neosporosis. Curr Res Parasitol Vector Borne Dis 1:100005.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crpvbd.2020.100005

")). Behavioural changes have also been reported in dogs and wild canids affected by toxoplasmosis (Papini et al. [2009](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR95 "Papini R, Mancianti F, Saccardi E (2009) Noise sensitivity in a dog with toxoplasmosis. Vet Rec 165:62.

https://doi.org/10.1136/vetrec.165.2.62-b

"); Milne et al. [2020](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR85 "Milne G, Fujimoto C, Bean T, Peters HJ, Hemmington M, Taylor C, Fowkes RC, Martineau HM, Hamilton CM, Walker M, Mitchell JA, Léger E, Priestnall SL, Webster JP (2020) Infectious causation of abnormal host behavior: Toxoplasma gondii and its potential Association with Dopey Fox Syndrome. Front Psychiatry 11:513536.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.513536

")).Peripheral neurological disorders

Peripheral neurological disorders are more frequently related to N. caninum infections than to T. gondii and include polyradiculoneuritis associated with chronic subacute evolving myositis. They are observed mainly in puppies under six months of age that have acquired the infection via the congenital route (Lyon [2010](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR76 "Lyon C (2010) Update on the diagnosis and management of Neospora caninum infections in dogs. Top Companion Anim Med 25:170–175. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.tcam.2010.07.005

")). Clinical signs may be evident at birth, but are observed more frequently in the first 5–8 weeks of life (Lyon [2010](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR76 "Lyon C (2010) Update on the diagnosis and management of Neospora caninum infections in dogs. Top Companion Anim Med 25:170–175.

https://doi.org/10.1053/j.tcam.2010.07.005

")). In the starting phase, the parasite affects the lumbosacral plexus, consequently neurological signs appear in the hind legs. Ipsilateral muscle weakness is observed, which rapidly affects the contralateral leg, and is followed by a rapid neurogenic atrophy with paraplegia and typical stiff hyperextension (arthrogryposis) of one or both hind legs (Dubey et al. [2009](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR46 "Dubey JP, Schares G, Ortega-Mora LM (2007) Epidemiology and control of neosporosis and Neospora caninum. Clin Microbiol Rev 20:323–367.

https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00031-06

")) (Fig. [2](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#Fig2)). In this phase, the animal retains deep pain perception and consciousness. This condition may progress to a chronic state without further developments. However, medium to large-sized animals are often euthanized due to poor quality of life and the difficulties in their management by owners.Fig. 2

An 8-week-old German Shepherd puppy affected by Neospora caninum exhibits characteristic stiff hyperextension (arthrogryposis) of both hind legs

In some cases, N. caninum can even affect the nerve roots of the forelimbs and CNS, causing tetraplegia and impairments of the brainstem and cranial nerves. This results in sensory deficits, nystagmus, absence of a menace response, dysphagia, megaesophagus, and arrhythmias, which may lead to sudden death due to cardiac arrest or phrenic nerve blockage accompanied by respiratory difficulties (Basso et al. [2005](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR13 "Basso W, Venturini MC, Bacigalupe D, Kienast M, Unzaga JM, Larsen A, Machuca M, Venturini L (2005) Confirmed clinical Neospora caninum infection in a boxer puppy from Argentina. Vet Parasitol 131:299–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2005.05.003

"); Dubey et al. [2009](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR46 "Dubey JP, Schares G, Ortega-Mora LM (2007) Epidemiology and control of neosporosis and Neospora caninum. Clin Microbiol Rev 20:323–367.

https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00031-06

")). Additionally, reduced tail movement, perineal sensitivity deficits, and local faecal and/or urinary incontinence have been reported (Basso et al. [2005](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR13 "Basso W, Venturini MC, Bacigalupe D, Kienast M, Unzaga JM, Larsen A, Machuca M, Venturini L (2005) Confirmed clinical Neospora caninum infection in a boxer puppy from Argentina. Vet Parasitol 131:299–303.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2005.05.003

")). The involvement of CNS is generally considered a negative prognostic indicator.To date, only one case of suspected toxoplasmosis in a 12-week-old puppy has been reported in the literature, presenting with hindlimb weakness, sarcopenia, rapidly progressing ascending paralysis, and respiratory distress (Chen et al. [2023](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR29 "Chen A, Boulay M, Chong S, Ho K, Chan A, Ong J, Fernandez CJ, Chang SF, Yap HH (2023) Suspected clinical toxoplasmosis in a 12-week-old puppy in Singapore. BMC Vet Res 19:110. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-023-03674-5

")).Central neurological disorders

Central neurological disorders caused by T. gondii and N. caninum are more frequently observed in animals older than one year. The neurological signs include sequelae of chronic infections. Specifically, the reactivation of latent cysts in the brain can cause focal or multifocal inflammatory processes depending on the selective tropism that the two parasites exhibit for different parts of the CNS (Carruthers and Suzuki [2007](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR26 "Carruthers VB, Suzuki Y (2007) Effects of Toxoplasma gondii infection on the brain. Schizophr Bull 33:745–751. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbm008

"); Silva and Machado [2016](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR116 "Silva DAO, Lobato J, Mineo TWP, Mineo JR (2007) Evaluation of serological tests for the diagnosis of Neospora caninum infection in dogs: optimization of cut off titers and inhibition studies of cross-reactivity with Toxoplasma gondii. Vet Parasitol 143:234–244.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.08.028

")). _Toxoplasma gondii_ may cause behavioural alterations, circling, tremors, and cranial nerve deficits. _N. caninum_ infections are more often associated with reduced levels of consciousness, head shaking, cerebellar ataxia, hypermetria, and cervical hyperesthesia, which are manifestations of meningoencephalitis and necrotizing cerebellitis (Dubey and Lindsay [1996](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR41 "Dubey JP (2008) The history of Toxoplasma gondii -- the first 100 years. J Eukaryot Microbiol 55:467–475.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1550-7408.2008.00345.x

"); Garosi et al. [2010](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR54 "Garosi L, Dawson A, Couturier J, Matiasek L, de Stefani A, Davies E, Jeffery N, Smith P (2010) Necrotizing cerebellitis and cerebellar atrophy caused by Neospora caninum infection: magnetic resonance imaging and clinicopathologic findings in seven dogs. J Vet Intern Med 24:571–578.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-1676.2010.0485.x

"); Calero-Bernal and Gennari [2019](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR21 "Calero-Bernal R, Gennari SM (2019) Clinical toxoplasmosis in dogs and cats: an update. Front Vet Sci 6:54.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2019.00054

"); Didiano et al. [2020](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR35 "Didiano A, Monti P, Taeymans O, Cherubini GB (2020) Canine central nervous system neosporosis: clinical, laboratory and diagnostic imaging findings in six dogs. Vet Rec Case Rep 8:e000905.

https://doi.org/10.1136/vetreccr-2019-000905

")).Toxoplasma gondii and, less frequently, N. caninum, are included in differential diagnoses of epilepsy, probably due to evidence in studies on mouse models and on several case-control studies conducted on humans (Ferguson and Hutchison [1987](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR52 "Ferguson DJ, Hutchison WM (1987) An ultrastructural study of the early development and tissue cyst formation of Toxoplasma gondii in the brains of mice. Parasitol Res 73:483–491. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00535321

"); Sadeghi et al. [2019](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR109 "Sadeghi M, Riahi SM, Mohammadi M, Saber V, Aghamolaie S, Moghaddam SA, Aghaei S, Javanian M, Gamble HR, Rostami A (2019) An updated meta-analysis of the association between Toxoplasma gondii infection and risk of epilepsy. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 113:453–462.

https://doi.org/10.1093/trstmh/trz025

")). Recently, a study searched the medical record database of the Veterinary Teaching Hospital, University of Perugia (Italy) for dogs serologically tested by IFAT for _T. gondii_ and _N. caninum_ between 2017 and 2023\. In order to investigate the serological correlation between these pathogens and epilepsy, the dogs were stratified by a clinical diagnosis of epilepsy or suffering from different conditions. The results obtained do not seem to support the role of _T. gondii_ and _N. caninum_ as causal agents of epilepsy in dogs (Morganti et al. [2024](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR89 "Morganti G, Rigamonti G, Marchesi MC, Maggi G, Angeli G, Moretta I, Brustenga L, Diaferia M, Veronesi F (2024) Toxoplasma gondii and Neospora caninum infection in epileptic dogs. J Small Anim Pract.

https://doi.org/10.1111/jsap.13735

")).Reproductive disorders

Toxoplasma gondii and Neospora caninum are known to cause abortions or stillbirths. However, there is no clear evidence supporting the role of these protozoa in reproductive disorders in dogs, which is largely inferred from their pathogenicity in other animal species (e.g., sheep and cattle). While N. caninum is primarily transmitted vertically in dogs, this transmission rarely results in foetal death (Reichel et al. [2007](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR103 "Reichel MP, Ellis JT, Dubey JP (2007) Neosporosis and hammondiosis in dogs. J Small Anim Pract 48:308–312. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-5827.2006.00236.x

")). Unlike _T. gondii_, _N. caninum_ can reactivate and cross the placental barrier during gestation, as it does not elicit a strong cell-mediated immune response (Barber and Trees [1998](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR9 "Barber JS, Trees AJ (1998) Naturally occurring vertical transmission of Neospora caninum in dogs. Int J Parasitol 28:57–64.

https://doi.org/10.1016/s0020-7519(97)00171-9

")). This transmission can lead to the onset of polyradiculoneuritis in varying numbers of puppies within a few weeks after birth. Asymptomatic puppies, particularly females used for breeding, can perpetuate infected bloodlines within breeding farms. The efficiency of _T. gondii_ transplacental transmission in dogs is lower than that of _N. caninum_. However, there is a stronger correlation between _T. gondii_ infection and instances of abortion and stillbirth (Bresciani et al. [2009](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR20 "Bresciani KD, Costa AJ, Toniollo GH, Luvizzoto MC, Kanamura CT, Moraes FR, Perri SH, Gennari SM (2009) Transplacental transmission of Toxoplasma gondii in reinfected pregnant female canines. Parasitol Res 104:1213–1217.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-008-1317-5

")). Puppies born with congenital toxoplasmosis often present without vital signs and exhibit multiple organ syndromes, with neurological manifestations such as encephalitis accompanied by hepatomegaly, ascites, interstitial pneumonia, and myocarditis (Calero-Bernal and Gennari [2019](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR21 "Calero-Bernal R, Gennari SM (2019) Clinical toxoplasmosis in dogs and cats: an update. Front Vet Sci 6:54.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2019.00054

")).Dermatological forms

Cutaneous clinical signs are associated mainly with N. caninum. Adult dogs with neosporosis in the case of concomitant diseases or long corticosteroid treatment may present with dermatological lesions characterized by erythematous epidermal nodules of various sizes (from 0.5 to 5 cm) and a tendency for ulcers. This clinical picture may be accompanied by satellite lymphadenomegaly. The histopathological lesions are described as pyogranulomatous and necrotizing dermatitis and alopecia, panniculitis with multifocal vasculitis, and vascular thrombosis (Webb et al. [2005](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR128 "Webb JA, Keller SL, Southorn EP, Armstrong J, Allen DG, Peregrine AS, Dubey JP (2005) Cutaneous manifestations of disseminated toxoplasmosis in an immunosuppressed dog. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 41:198–202. https://doi.org/10.5326/0410198

"); Park et al. [2007](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR97 "Park CH, Ikadai H, Yoshida E, Isomura H, Inukai H, Oyamada T (2007) Cutaneous toxoplasmosis in a female Japanese cat. Vet Pathol 44:683–687.

https://doi.org/10.1354/vp.44-5-683

"); Amir et al. [2008](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR6 "Amir G, Salant H, Resnick IB, Karplus R (2008) Cutaneous toxoplasmosis after bone marrow transplantation with molecular confirmation. J Am Acad Dermatol 59:781–784.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2008.07.014

"); Hoffmann et al. [2012](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR63 "Hoffmann AR, Cadieu J, Kiupel M, Lim A, Bolin SR, Mansell J (2012) Cutaneous toxoplasmosis in two dogs. J Vet Diagn Invest 24:636–640.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1040638712440995

")).Cases of systemic toxoplasmosis in dogs with diffusion of tachyzoites in the skin have been found after immunosuppressive treatments with corticosteroids or transplants (Bernsteen et al. [1999](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR16 "Bernsteen L, Gregory CR, Aronson LR, Lirtzman RA, Brummer DG (1999) Acute toxoplasmosis following renal transplantation in three cats and a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc 215:1123–1126. https://doi.org/10.2460/javma.1999.215.08.1123

"); Hoffmann et al. [2012](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR63 "Hoffmann AR, Cadieu J, Kiupel M, Lim A, Bolin SR, Mansell J (2012) Cutaneous toxoplasmosis in two dogs. J Vet Diagn Invest 24:636–640.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1040638712440995

")). However, dermatological forms caused by _T. gondii_ are reported above all in humans and rarely in immunocompromised cats (Mawhorter et al. [1992](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR81 "Mawhorter SD, Effron D, Blinkhorn R, Spagnuolo PJ (1992) Cutaneous manifestations of Toxoplasmosis. Clin Infect Dis 14:1084–1088.

https://doi.org/10.1093/clinids/14.5.1084

"); Beatty and Barrs [2003](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR14 "Beatty J, Barrs V (2003) Acute toxoplasmosis in two cats on cyclosporin therapy. Aust Vet J 81:339.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-0813.2003.tb11508.x

")).Other clinical forms

Other clinical forms associated with toxoplasmosis and neosporosis in dogs consist of myocarditis, hepatitis, pancreatitis and interstitial pneumonia, the latter being associated above all with T. gondii infections (Calero-Bernal and Gennari [2019](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR21 "Calero-Bernal R, Gennari SM (2019) Clinical toxoplasmosis in dogs and cats: an update. Front Vet Sci 6:54. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2019.00054

"); Dorsch et al. [2022](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR38 "Dorsch MA, Cesar D, Bullock HA, Uzal FA, Ritter JM, Giannitti F (2022) Fatal Toxoplasma gondii myocarditis in an urban pet dog. Vet Parasitol Reg Stud Rep 27:100659.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vprsr.2021.100659

")). Although less frequently than observed in cats, _T. gondii_ may also cause eye diseases such as necrotizing conjunctivitis (Swinger et al. [2009](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR119 "Swinger RL, Schmidt KA Jr, Dubielzig RR (2009) Keratoconjunctivitis associated with Toxoplasma gondii in a dog. Vet Ophthalmol 12:56–60.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-5224.2009.00675.x

")), anterior uveitis, endophthalmitis and chorioretinitis in dogs (Wolfer and Grahn [1996](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR130 "Wolfer J, Grahn B (1996) Diagnostic ophthalmology. Case report of anterior uveitis and endophthalmitis. Can Vet J 37:506–507")).Behavioural changes

Although the literature reports that T. gondii is implicated in behavioural modification in rodents and humans (Johnson and Koshy [2020](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR67 "Johnson HJ, Koshy AA (2020) Latent Toxoplasmosis effects on rodents and humans: how much is real and how much is Media hype? mBio. 11:e02164–e02119. https://doi.org/10.1128/mbio.02164-19

"); Tyebji et al. [2019](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR122 "Tyebji S, Seizova S, Hannan AJ, Tonkin CJ (2019) Toxoplasmosis: a pathway to neuropsychiatric disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 96:72–92.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.11.012

")), similar evidence is lacking for other hosts, including dogs. A single case report found a sudden noise sensitivity described as behavioural change in an 8-year-old female collie infected with _T. gondii_ (Papini et al. [2009](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR95 "Papini R, Mancianti F, Saccardi E (2009) Noise sensitivity in a dog with toxoplasmosis. Vet Rec 165:62.

https://doi.org/10.1136/vetrec.165.2.62-b

")).More evidence of correlations between T. gondii and behavioural changes has been found for wild canids. Recent studies report many wild red foxes exhibiting a range of aberrant behavioural traits, including apparent lack of fear and increased affection, and suggested that the infection with T. gondii and likely co-infection with Fox Circovirus and/or another neurotropic agent could be implicated in this spectrum, subsequently classified as Dopey Fox Syndrome (DFS) (Milne et al. [2020](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR85 "Milne G, Fujimoto C, Bean T, Peters HJ, Hemmington M, Taylor C, Fowkes RC, Martineau HM, Hamilton CM, Walker M, Mitchell JA, Léger E, Priestnall SL, Webster JP (2020) Infectious causation of abnormal host behavior: Toxoplasma gondii and its potential Association with Dopey Fox Syndrome. Front Psychiatry 11:513536. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.513536

")). A study conducted in Yellowstone National Park (USA) found that seropositive wolves were more likely to make high-risk decisions such as dispersing and becoming a pack leader, both of which factors are critical to individual fitness and wolf vital rates.These findings demonstrate that parasites have important implications for intermediate hosts, beyond acute infections, through behavioural impacts (Meyer et al. [2022](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR83 "Meyer CJ, Cassidy KA, Stahler EE, Brandell EE, Anton CB, Stahler DR, Smith DW (2022) Parasitic infection increases risk-taking in a social, intermediate host Carnivore. Commun Biol 5:1180. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-022-04122-0

")). Similarly, Gering et al. ([2021](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR55 "Gering E, Laubach ZM, Weber PSD, Soboll Hussey G, Lehmann KDS, Montgomery TM, Turner JW, Perng W, Pioon MO, Holekamp KE, Getty T (2021) Toxoplasma gondii infections are associated with costly boldness toward felids in a wild host. Nat Commun 12:3842.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-24092-x

")) found that, after three decades of field observations, _T. gondii_\-infected hyena cubs approach lions more closely than uninfected peers and thus have higher rates of mortality. No data on behavioural changes and infection by _N. caninum_ have been reported in dogs or wild canids.Diagnosis

Toxoplasmosis and neosporosis can be clinically confused with each other and with other diseases. A precise clinical examination supported by numerous specific (i.e., parasitological) and non-specific tests is therefore essential. Table 4 highlights the primary specific and non-specific tests that aid in diagnosing the various clinical manifestations of toxoplasmosis and neosporosis in dogs.

Table 4 Specific and nonspecific exams to support the diagnosis of the different clinical forms of canine toxoplasmosis and neosporosis

Specific tests

The diagnosis of T. gondii or N. caninum infections requires a series of tests that encompass both direct methods (which detect the parasite within lesions), and indirect methods that detect the host’s immune response. Indirect methods are predominantly used, especially in the initial stages, and typically involve screening tests.

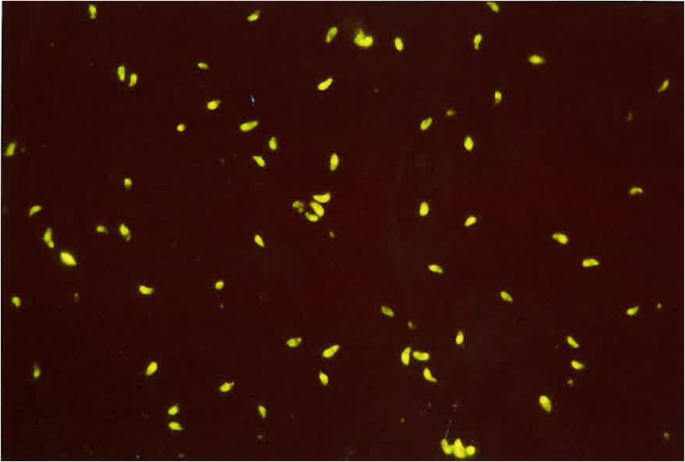

The most commonly employed immunodiagnostic tests in dogs include the Indirect Fluorescent Antibody Test (IFAT), which is known for its sensitivity and specificity (Fig. 3). For N. caninum, the IFAT typically utilizes a cut off of 1/50, which for T. gondii, is 1/40 (Silva et al. [2007](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR115 "Silva RC, Machado GP (2016) Canine neosporosis: perspectives on pathogenesis and management. Vet Med Res Rep 7:59–70. https://doi.org/10.2147/vmrr.s76969

"); Dini et al. [2023](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR37 "Dini FM, Stancampiano L, Poglayen G, Galuppi R (2024) Risk factors for Toxoplasma gondii infection in dogs: a serological survey. Acta Vet Scand 66(1):14.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s13028-024-00734-0

")). The Enzyme Linked Immuno Assay (ELISA) is also used. Both tests detect IgG and IgM antibodies generated against either corpuscular antigens (IFAT) or soluble antigens (ELISA) of varying degrees of purification.Fig. 3

Indirect fluorescent antibody test used for the diagnosis of Toxoplasma gondii (cut off 1/40)

The serological result must be interpreted with caution, since both infections are persistent and have a low degree of morbidity. Seropositivity may therefore demonstrate infection and not the active role of the parasite in the disease progression. Low antibody titres (i.e. IFAT results lower than the cut off dilution) or apical reactions (i.e. reactions limited to the apex of the parasite) may be regarded as the expression of cross-reactivity with parasites of the Sarcocystidae family (i.e. Sarcocystis, Hammondia, which are closely antigenically correlated (Gondim et al. [2017](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR58 "Goździk K, Wrzesień R, Wielgosz-Ostolska A, Bień J, Kozak-Ljunggren M, Cabaj W (2011) Prevalence of antibodies against Neospora caninum in dogs from urban areas in Central Poland. Parasitol Res 108:991–996. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-010-2143-0

")), or with other common pathogens affecting dogs such as _Leishmania infantum_ and _Ehrlichia canis_ (Silva et al. [2007](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR115 "Silva RC, Machado GP (2016) Canine neosporosis: perspectives on pathogenesis and management. Vet Med Res Rep 7:59–70.

https://doi.org/10.2147/vmrr.s76969

"); Zanette et al. [2014](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR134 "Zanette MF, Lima VM, Laurenti MD, Rossi CN, Vides JP, Vieira RF, Biondo AW, Marcondes M (2014) Serological cross-reactivity of Trypanosoma Cruzi, Ehrlichia canis, Toxoplasma Gondii, Neospora Caninum and Babesia canis to Leishmania infantum chagasi tests in dogs. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 47:105–107.

https://doi.org/10.1590/0037-8682-1723-2013

")).Both IgM and IgG antibodies need to be assessed because IgM antibodies can be detected starting from the second week after the infection and persist for about four months, while IgG antibodies are produced starting from the third to fourth week after the infection and may persist throughout out life at the cut off level (Sinnott et al. [2017](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR117 "Sinnott FA, Monte LG, Collares TF, Maraninchi Silveira R, Borsuk S (2017) Review on the immunological and molecular diagnosis of neosporosis (years 2011–2016). Vet Parasitol 239:19–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2017.04.008

")). In addition, in congenital forms, caused especially by _N. caninum_, the interference of maternal passive immunity in the first 14 weeks of life can complicate the diagnosis. In this case, the detection of IgM is mandatory (Anderson et al. [2000](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR7 "Anderson ML, Andrianarivo AG, Conrad PA (2000) Neosporosis in cattle. Anim Reprod Sci 60–61:417–431.

https://doi.org/10.1016/s0378-4320(00)00117-2

")).In symptomatic animals, it is useful to distinguish the classes of antibodies in order to assess the possibility of a recent infection and to define the antibody titre. In fact, active infections are generally associated with high antibody titres (IgG starting from 1/200 for N. caninum and 1/80 for T. gondii). Nevertheless, since a low antibody titre does not rule out active infection, seroconversion should be verified after two weeks in the case of a well-founded suspicion along with histological or immunohistochemical tests (Piergili Fioretti 2004; Sinnott et al. [2017](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR117 "Sinnott FA, Monte LG, Collares TF, Maraninchi Silveira R, Borsuk S (2017) Review on the immunological and molecular diagnosis of neosporosis (years 2011–2016). Vet Parasitol 239:19–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2017.04.008

")).Serological positivity has a reduced positive predictive value in relation to both central and peripheral neurological forms. In these disorders, the antibody titre in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is considered more accurate. However, the possibility of false positives related to contamination of the blood during collection remains, as well as the normal passive transfer of antibodies through the blood-brain barrier. Demonstration of intrathecal antibody production entails establishing the ratio between the titres of antibodies in the CSF and circulating antibodies (QIgG = Cerebrospinal fluid IgG/Serum IgG) (Whitney Marlyn and Ripley Coates [2020](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR129 "Whitney Marlyn S, Ripley Coates J (2020) Cerebrospinal fluid analysis in the dog and cat. In: Sharkey LC, Radin MJ, Seelig D (eds) Veterinary citology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., pp 638–654. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119380559.ch48

")).Direct methods often have limitations related to intra-vitam sampling. These tests include (a) cytological tests for tachyzoite identification prepared from dermatological lesions or in bronchoalveolar washing and CSF in the course of interstitial pneumonia and neurological disorders, respectively; (b) histological examinations on biopsy samples of CNS (e.g. tibial nerve during neosporosis), muscles, liver, spleen, heart, lungs, skeletal muscles and kidneys to reveal cystic and pseudocyst formations. These are the only examinations that establish a cause-effect connection with the lesions, however, they are difficult to apply intra-vitam due to the invasiveness of the sampling.

Notably, the cysts of N. caninum and T. gondii have the same size (100 μm), and only differ in the thickness of the wall (thicker in N. caninum than in T. gondii) and may have a range of variability that depends on the phase of development. Diagnostic certainty therefore requires PCR tests using various protocols (e.g. traditional PCR, nested-PCR, real-time PCR) or by immunohistochemical target (IHC), which detects immunodominant surface antigens. Although PCR offers a more accurate means of revealing active infection by amplifying parasite-specific deoxyribonucleic acid in CSF, false negatives are possible if the protozoan is embedded deeply into the tissues (Coelho et al. [2019](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR30 "Coelho AM, Cherubini G, De Stefani A, Negrin A, Gutierrez-Quintana R, Bersan E, Guevar J (2019) Serological prevalence of toxoplasmosis and neosporosis in dogs diagnosed with suspected meningoencephalitis in the UK. J Small Anim Pract 60(1):44–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsap.12937

")).Direct tests also include coprological examinations to identify the presence of N. caninum oocysts. However, their detection in dogs is rare and does not necessarily correlate with clinical manifestations associated with the parasite’s extraintestinal cycle. From an epidemiological standpoint, detection of oocysts in faeces can help to determine the role of dogs as a potential source of infection in dairy farms. The oocysts can be detected using a flotation technique with a 33% zinc sulphate solution. Despite their infrequent detection, oocysts of N. caninum resemble those of Cystoisospora, making them potentially confusable with those from other dog coccidia or incidental parasites acquired through predation on birds and rodents. Table 5 presents the main morphological characteristics that differentiate N. caninum oocysts from those of other species.

Table 5 Morphological characteristics of oocysts belonging to Apicomplexa Phylum

Non-specific tests

Non-specific tests may support diagnosis and identify the degree of impairment of different organs. These include (a) complete blood count and biochemical blood tests, useful above all in systemic disorders and polyradiculoneuritis; (b) total protein concentration and cytological analysis of the CSF in central and peripheral neurological forms; (c) X-ray examination of chest and magnetic resonance imaging for interstitial pneumonia and central neurological disorders, respectively. Table 6 indicates the most frequently detectable alterations recorded in dogs affected by toxoplasmosis and/or neosporosis.

Table 6 Detectable alterations in nonspecific tests during neosporosis and toxoplasmosis in dogs

Treatment and prevention

No treatment is required in asymptomatic dogs affected by T. gondii and N. caninum infections. In addition, no currently available molecule is able to penetrate the wall of the cyst and thus eliminate the bradyzoites in chronic forms. In contrast, dogs with clinical signs require prompt treatment in order to suppress the replication of tachyzoites and prevent clinical progression.

Concerning toxoplasmosis, clindamycin is the elective drug at a dosage of 12.5–25 mg/kg orally, twice a day, for at least 4 weeks, however, in some cases, 2 months of treatment may be required. Clindamycin administered per os may cause anorexia, vomiting and diarrhoea in dogs treated at high doses, as it irritates the gastrointestinal mucosa. Alternatively, a parenteral treatment can be administered, via the intramuscular route, with 25 mg/kg of clindamycin phosphate, twice a day, for 4 weeks or with a combination of trimethoprim-sulfadiazine at a dosage of 15–30 mg/kg, orally, twice a day, for 4–6 weeks.

In general, dogs with toxoplasmosis react better to treatment than those affected by clinical neosporosis. In fact, when muscle contracture has already set in during neosporosis, the administration of drugs is only partially effective. Neosporosis treatment consists in clindamycin at a dosage of 10 mg/kg, orally, three times a day, for 4 to 24 weeks or 7.5–25 mg/kg, orally, twice a day, for at least 4 weeks. Alternatively, a combination of trimethoprim and sulfadiazine at a dosage of 15–30 mg/kg, orally, twice a day, for at least 4 weeks, and pyrimethamine at a dosage of 1 mg/kg, orally, once a day, can be administered to exploit their synergy (Dubey and Lindsay [1996](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR41 "Dubey JP (2008) The history of Toxoplasma gondii -- the first 100 years. J Eukaryot Microbiol 55:467–475. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1550-7408.2008.00345.x

"); Lyon [2010](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR76 "Lyon C (2010) Update on the diagnosis and management of Neospora caninum infections in dogs. Top Companion Anim Med 25:170–175.

https://doi.org/10.1053/j.tcam.2010.07.005

")).Regarding prophylactic measures, dogs should not be fed with cooked meat or entrails. Predatory activity should be prevented, together with access to cats’ litter boxes, especially for animals that practise coprophagia. Dogs should never have access to the placental materials of bovine or small ruminants, dead calves or lambs or foetal membranes. Effective vaccines to protect dogs and prevent infection are not commercially available for N. caninum or for T. gondii, however some attempts were made to design vaccine against N. caninum for use in dogs (Nishikawa et al. [2000](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR92 "Nishikawa Y, Ikeda H, Fukumoto S, Xuan X, Nagasawa H, Otsuka H, Mikami T (2000) Immunization of dogs with a canine herpesvirus vector expressing Neospora caninum surface protein, NcSRS2. Int J Parasitol 30:1167–1171. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0020-7519(00)00111-9

")).Seropositive bitches may transmit N. caninum and, less frequently, T. gondii to their puppies. It is thus advisable to exclude them from any reproduction program, as they could generate infected maternal-filial lines, which could maintain the infection endemicity on breeding farms and in canine populations. Finally, immunosuppressive treatments in seropositive dogs should be avoided because they could be potentially responsible for reactivating the infection (Barker et al. [2021](/article/10.1007/s11259-024-10549-z#ref-CR10 "Barker A, Wigney D, Child G, Šlapeta J (2021) Seroprevalence of Neospora caninum in dogs from greater Sydney, Australia unchanged from 1997 to 2019 and worldwide review of adult-onset of canine neosporosis. Curr Res Parasitol Vector Borne Dis 1:100005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crpvbd.2020.100005

")).Conclusions

Differentiating between a T. gondii and N. caninum infection in dogs is crucial for the individual animal’s health and also for preventing transmission to humans, and effectively managing diseases on farms. This differentiation also optimizes treatments and promotes enhanced public health and food safety measures.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

- Adhami G, Dalimi A, Hoghooghi-Rad N, Fakour S (2020) Molecular and serological study of Neospora caninum infection among dogs and foxes in Sanandaj, Kurdistan Province, Iran. Arch Razi Inst 75:267–274. https://doi.org/10.22092/ari.2018.120218.1186

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Ahmad N, Ahmed H, Irum S, Qayyum M (2014) Seroprevalence of IgG and IgM antibodies and associated risk factors for toxoplasmosis in cats and dogs from sub-tropical arid parts of Pakistan. Trop Biomed 31:777–784

PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Al-Malki ES (2021) Toxoplasmosis: stages of the protozoan life cycle and risk assessment in humans and animals for an enhanced awareness and an improved socio-economic status. Saudi J Biol Sci 28:962–969. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sjbs.2020.11.007

Article CAS Google Scholar - Ali CN, Harris JA, Watkins JD, Adesiyun AA (2003) Seroepidemiology of Toxoplasma gondii in dogs in Trinidad and Tobago. Vet Parasitol 113:179–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-4017(03)00075-x

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Alvarado-Esquivel C, Romero-Salas D, Cruz-Romero A, García-Vázquez Z, Peniche-Cardeña A, Ibarra-Priego N, Ahuja-Aguirre C, Pérez-de-León AA, Dubey JP (2014) High prevalence of Toxoplasma gondii antibodies in dogs in Veracruz, Mexico. BMC Vet Res 10:191. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-014-0191-x

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar - Amir G, Salant H, Resnick IB, Karplus R (2008) Cutaneous toxoplasmosis after bone marrow transplantation with molecular confirmation. J Am Acad Dermatol 59:781–784. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2008.07.014

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Anderson ML, Andrianarivo AG, Conrad PA (2000) Neosporosis in cattle. Anim Reprod Sci 60–61:417–431. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0378-4320(00)00117-2

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Ayinmode AB, Adediran OA, Schares G (2016) Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii and Neospora caninum in urban and rural dogs from southwestern Nigeria. African J Infect Dis 10:25–28. https://doi.org/10.4314/ajid.v10i1.5

- Barber JS, Trees AJ (1998) Naturally occurring vertical transmission of Neospora caninum in dogs. Int J Parasitol 28:57–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0020-7519(97)00171-9

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Barker A, Wigney D, Child G, Šlapeta J (2021) Seroprevalence of Neospora caninum in dogs from greater Sydney, Australia unchanged from 1997 to 2019 and worldwide review of adult-onset of canine neosporosis. Curr Res Parasitol Vector Borne Dis 1:100005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crpvbd.2020.100005

Article CAS Google Scholar - Barr BC, Conrad PA, Sverlow KW, Tarantal AF, Hendrickx AG (1994) Experimental fetal and transplacental Neospora infection in the nonhuman primate. Lab Investig J Tech Methods Pathol 71:236–242

CAS Google Scholar - Bartels CJM, Wouda W, Schukken YH (1999) Risk factors for _Neospora caninum_-associated abortion storms in dairy herds in the Netherlands (1995 to 1997). Theriogenology 52:247–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0093-691x(99)00126-0

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Basso W, Venturini MC, Bacigalupe D, Kienast M, Unzaga JM, Larsen A, Machuca M, Venturini L (2005) Confirmed clinical Neospora caninum infection in a boxer puppy from Argentina. Vet Parasitol 131:299–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2005.05.003

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Beatty J, Barrs V (2003) Acute toxoplasmosis in two cats on cyclosporin therapy. Aust Vet J 81:339. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-0813.2003.tb11508.x

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Benitez Ado, Martins N, Mareze FDC, Santos M, Ferreira NJS, Martins FP, Garcia CM, Mitsuka-Breganó JL, Freire R, Biondo RL, Navarro AW IT (2017) Spatial and simultaneous representative seroprevalence of anti-Toxoplasma gondii antibodies in owners and their domiciled dogs in a major city of southern Brazil. PLoS ONE 12. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0180906

- Bernsteen L, Gregory CR, Aronson LR, Lirtzman RA, Brummer DG (1999) Acute toxoplasmosis following renal transplantation in three cats and a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc 215:1123–1126. https://doi.org/10.2460/javma.1999.215.08.1123

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Black MW, Boothroyd JC (2000) Lytic cycle of Toxoplasma gondii. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 64:607–23. https://doi.org/10.1128/mmbr.64.3.607-623.2000

- Borges-Silva W, Rezende-Gondim MM, Galvão GS, Rocha DS, Albuquerque GR, Gondim LP (2021) Cytologic detection of Toxoplasma gondii in the cerebrospinal fluid of a dog and in vitro isolation of a unique mouse-virulent recombinant strain. J Vet Diagn Invest 33:591–594. https://doi.org/10.1177/1040638721996685

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar - Brasil AWL, Parentoni RN, Da Silva JG, Santos C, de SAB, Mota RA, De Azevedo SS (2018) Risk factors and anti-Toxoplasma gondii and Neospora caninum antibody occurrence in dogs in João Pessoa, Paraíba state, Northeastern Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 27:242–247. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612018006

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Bresciani KD, Costa AJ, Toniollo GH, Luvizzoto MC, Kanamura CT, Moraes FR, Perri SH, Gennari SM (2009) Transplacental transmission of Toxoplasma gondii in reinfected pregnant female canines. Parasitol Res 104:1213–1217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00436-008-1317-5

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Calero-Bernal R, Gennari SM (2019) Clinical toxoplasmosis in dogs and cats: an update. Front Vet Sci 6:54. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2019.00054

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Campos HGN, Soares HS, Azevedo SS, Gennari SM (2022) Occurrence of Toxoplasma gondii and Neospora caninum antibodies and risk factors in domiciliated dogs of Manaus, Amazonas, Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 31:e020321. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1984-29612022024

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Cano-Terriza D, Puig-Ribas M, Jiménez-Ruiz S, Cabezón Ó, Almería S, Galán-Relaño Á, Dubey JP, García-Bocanegra I (2016) Risk factors of Toxoplasma gondii infection in hunting, pet and watchdogs from southern Spain and northern Africa. Parasitol Int 65:363–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parint.2016.05.001

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Capelli G, Nardelli S, di Regalbono AF, Scala A, Pietrobelli M (2004) Sero-epidemiological survey of Neospora caninum infection in dogs in north-eastern Italy. Vet Parasitol 123:143–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2004.06.012

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Cardinot CB, Silva JE, Yamatogi RS, Nunes CM, Biondo AW, Vieira RF, Junior JP, Marcondes M (2016) Detection of Ehrlichia canis, Babesia vogeli and Toxoplasma gondii DNA in the brain of dogs naturally infected with Leishmania infantum. J Parasitol 102:275–279. https://doi.org/10.1645/15-821

- Carruthers VB, Suzuki Y (2007) Effects of Toxoplasma gondii infection on the brain. Schizophr Bull 33:745–751. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbm008

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Cedillo CJR, Martínez MJJ, Santacruz AM, Banda RVM, Morales SE (2008) Models for experimental infection of dogs fed with tissue from fetuses and neonatal cattle naturally infected with Neospora caninum. Vet Parasitol 154:151–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2008.02.025

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Cedillo-Peláez C, Díaz-Figueroa ID, Jiménez-Seres MI, Sánchez-Hernández G, Correa D (2012) Frequency of antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii in stray dogs of Oaxaca, México. J Parasitol 98:871–872. https://doi.org/10.1645/GE-3095.1

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Chen A, Boulay M, Chong S, Ho K, Chan A, Ong J, Fernandez CJ, Chang SF, Yap HH (2023) Suspected clinical toxoplasmosis in a 12-week-old puppy in Singapore. BMC Vet Res 19:110. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-023-03674-5

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Coelho AM, Cherubini G, De Stefani A, Negrin A, Gutierrez-Quintana R, Bersan E, Guevar J (2019) Serological prevalence of toxoplasmosis and neosporosis in dogs diagnosed with suspected meningoencephalitis in the UK. J Small Anim Pract 60(1):44–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsap.12937

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Cruz-Vázquez C, Maldonado-López L, Vitela-Mendoza I, Medina-Esparza L, Aguilar-Marcelino L, de Velasco-Reyes I (2023) Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii infection and associated risk factors in different populations of dogs from aguascalientes, Mexico. Acta Parasitol 68:683–689. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11686-023-00703-z

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Cui LL, Yu YL, Liu S, Wang BB, Zhang ZX, Wang M (2012) Epidemiological investigations of toxoplasmosis in dogs and cats in Beijing area. Chin J Vet Med 48:7–9

Google Scholar - Curtis B, Harris A, Ullal T, Schaffer PA, Muñoz Gutiérrez J (2020) Disseminated Neospora caninum infection in a dog with severe colitis. J Vet Diagn Invest 32(6):923–927. https://doi.org/10.1177/1040638720958467

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Da Cunha GR, Pellizzaro M, Martins CM, Rocha SM, Yamakawa AC, Da Silva EC, Dos Santos AP, Morikawa VM, Langoni H, Biondo AW (2020) Spatial serosurvey of anti-Toxoplasma gondii antibodies in individuals with animal hoarding disorder and their dogs in Southern Brazil. PLoS ONE 15(5):e0233305. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0233305

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar - Didiano A, Monti P, Taeymans O, Cherubini GB (2020) Canine central nervous system neosporosis: clinical, laboratory and diagnostic imaging findings in six dogs. Vet Rec Case Rep 8:e000905. https://doi.org/10.1136/vetreccr-2019-000905

Article Google Scholar - Dini FM, Morselli S, Marangoni A, Taddei R, Maioli G, Roncarati G, Balboni A, Dondi F, Lunetta F, Galuppi R (2023) Spread of Toxoplasma gondii among animals and humans in Northern Italy: a retrospective analysis in a one-health framework. Food Waterborne Parasitol 32:e00197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fawpar.2023.e00197

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar - Dini FM, Stancampiano L, Poglayen G, Galuppi R (2024) Risk factors for Toxoplasma gondii infection in dogs: a serological survey. Acta Vet Scand 66(1):14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13028-024-00734-0

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar - Dorsch MA, Cesar D, Bullock HA, Uzal FA, Ritter JM, Giannitti F (2022) Fatal Toxoplasma gondii myocarditis in an urban pet dog. Vet Parasitol Reg Stud Rep 27:100659. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vprsr.2021.100659

Article Google Scholar - Duan G, Tian YM, Li BF, Li T, Chen Y, Wang S, Han X, Wang Q (2012) Seroprevalence of Toxoplasma gondii infection in pet dogs in Kunming, Southwest China. Parasites Vectors 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-5-118

- Duarte PO, Oshiro LM, Zimmermann NP, Csordas BG, Dourado DM, Barros JC, Andreotti R (2020) Serological and molecular detection of Neospora caninum and Toxoplasma gondii in human umbilical cord blood and placental tissue samples. Sci Rep 10:9043. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-65991-1

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar - Dubey JP (2008) The history of Toxoplasma gondii -- the first 100 years. J Eukaryot Microbiol 55:467–475. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1550-7408.2008.00345.x

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Dubey JP, Lindsay DS (1996) A review of Neospora caninum and neosporosis. Vet Parasitol 67:1–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-4017(96)01035-7

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Dubey JP, Schares G (2011) Neosporosis in animals -- the last five years. Vet Parasitol 180:90–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.05.031

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Dubey JP, Barr BC, Barta JR, Bjerkås I, Björkman C, Blagburn BL, Bowman DD, Buxton D, Ellis JT, Gottstein B, Hemphill A, Hill DE, Howe DK, Jenkins MC, Kobayashi Y, Koudela B, Marsh AE, Mattsson JG, McAllister MM, Modrý D, Omata Y, Sibley LD, Speer CA, Trees AJ, Uggla A, Upton SJ, Williams DJ, Lindsay DS (2002) Redescription of Neospora caninum and its differentiation from related coccidia. Int J Parasitol 32:929–946. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0020-7519(02)00094-2

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Dubey JP, Lipscomb TP, Mense M (2004) Toxoplasmosis in an elephant seal (Mirounga angustirostris). J Parasitol 90:410–411. https://doi.org/10.1645/ge-155r

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Dubey JP, Schares G, Ortega-Mora LM (2007) Epidemiology and control of neosporosis and Neospora caninum. Clin Microbiol Rev 20:323–367. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00031-06

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar - Dubey JP, Lindsay DS, Lappin MR (2009) Toxoplasmosis and other Intestinal Coccidial infections in cats and dogs. Vet Clin North Am - Small Anim Pract 39:1009–1034. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cvsm.2009.08.001

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Dubey JP, Tiwari K, Chikweto A, DeAllie C, Sharma R, Thomas D, Choudhary S, Ferreira LR, Oliveira S, Verma SK, Kwok OCH, Su C (2013) Isolation and RFLP genotyping of Toxoplasma gondii from the domestic dogs (Canis familiaris) from Grenada, West Indies revealed high genetic variability. Vet Parasitol 197:623–626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2013.07.029

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar - Dubey JP, Murata FHA, Cerqueira-Cézar CK, Kwok OCH, Yang Y, Su C (2020) Toxoplasma gondii infections in dogs: 2009–2020. Vet Parasitol 31:287:109223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2020.109223

Article CAS Google Scholar - Dwinata IM, Oka IBM, Agustina KK, Damriyasa IM (2018) Seroprevalence of Neospora caninum in local Bali dog. Vet World 11:926–929. https://doi.org/10.14202/vetworld.2018.926-929

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - El Behairy AM, Choudhary S, Ferreira LR, OCH Kwok, Hilali M, Su C, Dubey JP (2013) Genetic characterization of viable Toxoplasma gondii isolates from stray dogs from Giza, Egypt. Vet Parasitol 193:25–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2012.12.007

- Ferguson DJ, Hutchison WM (1987) An ultrastructural study of the early development and tissue cyst formation of Toxoplasma gondii in the brains of mice. Parasitol Res 73:483–491. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00535321