Trends in Distant-Stage Breast, Colorectal, and Prostate Cancer Incidence Rates from 1992 to 2004: Potential Influences of Screening and Hormonal Factors (original) (raw)

Abstract

Differential utilization of cancer screening between populations could lead to changes in cancer disparities. Evaluating incidence rates trends is one means of monitoring these disparities. Using Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results data, we compared annual percent changes (APC) in age-adjusted incidence rates of distant-stage breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer between non-Hispanic whites (NHW) and African Americans (AA). From 1992 to 2004, distant-stage breast cancer incidence rates remained essentially constant among both AA and NHW women, though rates were 30–90% higher among AA women throughout. NHW men and women experienced declines in distant-stage colorectal cancer incidence rates [APC = −1.6, 95% confidence interval (CI) −2.3, −0.9], but AA men and women did not. Distant-stage prostate cancer incidence rates declined for both AA (APC = −5.8, 95% CI −7.9, −3.8) and NHW (APC = −5.1, 95% CI −6.7, -3.4). Despite now having nearly equal mammography screening rates, the persistent breast cancer disparity observed among AAs compared to NHWs may be due to the greater susceptibility of AAs to more aggressive tumors, particularly hormone-receptor-negative disease, which is more difficult to detect by mammography. For colorectal cancer, greater utilization of screening tests among NHWs vs. AAs is likely a primary contributor to the observed widening disparity. Wider recognition of AA race as a prostate cancer risk factor may contribute to the narrowing disparity in the incidence of disease.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles and news from researchers in related subjects, suggested using machine learning.

Introduction

Racial disparities in cancer incidence and mortality have been extensively documented. Specifically, numerous studies have described disparities in cancer incidence and mortality between whites and African Americans for three screenable cancers: breast [1–4], colorectal [5], and prostate cancers [6]. While many studies point to inequalities in cancer screening as a structural reason driving cancer disparities [7, 8], racial differences in tumor biology and hormonal influences also appear to be important contributors [9–13]. For breast cancer, it is well documented that African American women are more likely to be diagnosed with hormone-receptor-negative tumors compared to whites [9–12] and that these tumors are more aggressive and have a poorer prognosis compared to hormone-receptor-positive disease regardless of factors such as stage or grade [14]. Also of note is that hormone-receptor-negative tumors are more difficult to detect by mammography compared to hormone-receptor-positive tumors. Specifically, interval-detected cancers are 1.8- to 2.6-fold more likely to be estrogen receptor (ER) negative compared to screen-detected tumors [15, 16]. In addition, hormonal factors may contribute to racial disparities in prostate cancer incidence. Several studies have observed that on average African American men have higher levels of endogenous androgens compared to non-Hispanic white men of similar age [17, 18]. While there is some evidence that androgen levels are positively related to prostate cancer risk [19, 20], a recent analysis by the Breast and Prostate Cancer Cohort Consortium found no association between differences in sex hormone concentrations in men and prostate cancer risk [21].

An aspect of disparities present for breast, colorectal, and prostate cancers that is unclear is the extent to which they may be widening or narrowing as a result of the increased availability of screening tests for these cancers over the past several years. Disparities could widen if certain populations have greater access to screening, could narrow if populations with poorer outcomes have experienced improved access to screening, or could remain the same if screening has been utilized more uniformly. For each of these cancer sites, mortality rates are substantially higher among African Americans compared to non-Hispanic whites in the USA [22]. The goal of cancer screening tests is the early detection of cancer or precancerous lesions and the prevention of advanced-stage disease. As such, one means of assessing the impact of screening is to evaluate incidence rates of advanced-stage disease. Here, we examine trends in distant-stage breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer incidence rates among African Americans and whites in the USA between 1992 and 2004 as an ecologic indicator of how the cancer disparities experienced by African Americans may be narrowing or widening compared to whites during an era of increasing utilization of breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer screening.

Methods

This study used publicly available data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program, which is funded by the National Cancer Institute. The SEER 13 Registry Limited Use, Nov2006 (Sub 1992–2004), dataset was used to identify cases. This dataset includes cancer cases ascertained from the following population-based cancer registries: Atlanta, Connecticut, Detroit, Hawaii, Iowa, Los Angeles, New Mexico, Rural Georgia, San Francisco–Oakland, San Jose–Monterrey, Seattle–Puget Sound, and Utah. Data from the Alaska Native Tumor Registry were not included because this registry is limited to Alaska Natives only and thus does not consist of any African Americans or whites.

All females between 40 and 64 years of age who were diagnosed with distant-stage breast cancer were included in our breast cancer analyses. Only women in this age range were considered because current breast cancer screening guidelines set forth by the American Cancer Society (ACS) recommend yearly mammograms beginning at age 40 and because the majority of people over age 64 are covered by Medicare. Males and females of between 50 and 64 years of age who were diagnosed with distant-stage colorectal cancer were included in the colorectal cancer analysis. Males between the ages of 50 and 64 who were diagnosed with distant-stage prostate cancer were included in the prostate cancer analyses. The age range of 50–64 was chosen for both colorectal and prostate cancers to reflect ACS screening guidelines and Medicare eligibility. Data on tumor stage were obtained from the SEER database, which relies on information abstracted from medical records. Distant-stage tumors were identified using the SEER historic stage A coding and are defined by tumor cells that have broken away from the primary tumor, have traveled to other parts of the body, and have begun to grow at a new location. Clinically, distant-stage tumors are often referred to as remote, disseminated, diffuse, or metastatic [23]. For all cancer sites, cases were limited to those diagnosed between 1992 and 2004.

Data on race were ascertained from the SEER database and are also based on medical record reviews. Analyses were restricted to cases identified as white or African American race who were also non-Hispanic. Asians/Pacific Islanders, American Indians/Alaska Natives, and people of Hispanic ethnicity were not evaluated separately because insufficient numbers of distant-stage breast, colorectal, and prostate cancers within each racial/ethnic group per year were diagnosed to meaningfully evaluate time trends.

Demographic characteristics used to describe group-level differences, including year of diagnosis, age at diagnosis, SEER registry, and gender were obtained from the SEER database. Age at diagnosis was subdivided into five 5-year groups: 40–44, 45–49, 50–54, 55–59, and 60–64. County-level measures of socioeconomic status (SES) based on information from the 2000 US Census are also available from the SEER database. Three county attribute variables were used as group-level measures of SES: median annual household income (<$45,000, 45,000–45,000–45,000–54,999, and ≥$55,000), percent of persons in the county with less than a high school education (<15.0%, 15.0–24.9%, and ≥25.0%), and the percent of persons in the county living below the federal poverty level (<5.0%, 5.0–9.9%, and ≥10.0%).

SEER*Stat Software Version 6.4.4 was used to calculate incidence rates and annual percent changes (APC). Age-adjusted incidence rates were calculated based on population distributions from the 2000 US Census P25-1130. Age-adjusted trends were evaluated based on APC which were calculated using the least squares method in SEER*Stat. We also used the National Cancer Institute’s Joinpoint Regression Program Version 3.3 to evaluate the statistical significance of the age-adjusted trends in cancer incidence using a Monte Carlo permutation method [24]. Disparities were assessed on a relative scale by calculating the relative risk comparing African American to white incidence rates for each year of diagnosis and cancer site. In addition, rate differences were calculated by subtracting the incidence rate for whites from the incidence rate for African Americans in order to provide a comparison of the absolute disparity for each year of diagnosis and cancer site [25].

Results

Demographic Characteristics

Across all three cancer sites, the cancer registries contributing the largest numbers of African American cases were Atlanta, Detroit, Los Angeles, and San Francisco–Oakland and the registries contributing the largest numbers of white cases were Connecticut, Detroit, Iowa, Los Angeles, San Francisco–Oakland, and Seattle–Puget Sound (Table 1). In addition, African American cases were somewhat more likely to live in counties that had lower median annual household incomes, higher proportions of residents without a high school education, and higher proportions of residents living below the federal poverty level.

Table 1 Characteristics of distant-stage breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer cases diagnosed from 1992 to 2004

Breast Cancer

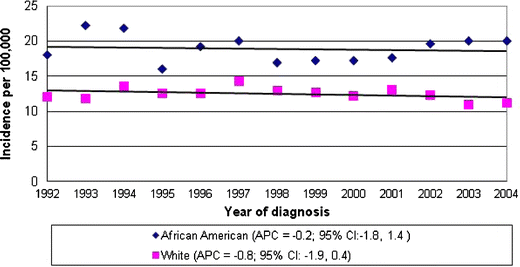

From 1992 to 2004, there were a total of 7,237 newly diagnosed cases of distant-stage breast cancer diagnosed in African American (n = 1,364) and white women (n = 5,873). African American women tended to be somewhat younger at diagnosis (Table 1). Age-adjusted distant-stage breast cancer incidence rates for African American women were 18.0/100,000 in 1992 and 20.0/100,000 in 2004, climbing as high as 22.2/100,000 in 1993 (Table 2). Rates among white women were 12.0/100,000 in 1992 and 11.2/100,000 in 2004, with a peak incidence of 14.3/100,000 in 1997. On a relative scale, African American women were between 30% and 90% more likely to be diagnosed with distant-stage breast cancer than white women during this time, with no clear trend of this disparity either widening or narrowing over this time period. The rate difference, a measure of the absolute difference in African American and white rates, ranged between 10.4 and 3.5 with no apparent trend over time. Overall, rates of distant-stage breast cancer remained essentially constant between 1992 and 2004 for both African American women (APC = −0.2, 95% confidence interval (CI) −1.8, 1.4) and white women (APC = −0.8, 95% CI −1.9, 0.4; Fig. 1).

Table 2 Distant-stage breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer incidence rates and age-adjusted relative risks for African Americans and whites from 1992 to 2004

Fig. 1

Trends in distant-stage breast cancer in African American and white females from 1992 to 2004.

Colorectal Cancer

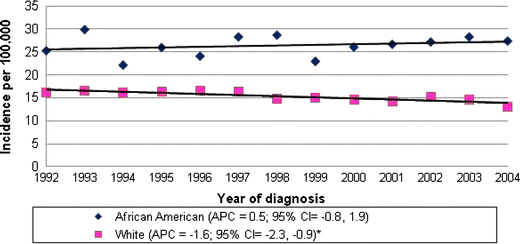

A total of 8,920 cases of distant-stage colorectal cancer were diagnosed from 1992 to 2004 in African American (n = 1,669) and white (n = 7,251) men and women. African American colorectal cases were slightly younger at diagnosis and were more likely to be female (47.3%) as compared to whites (41.4%; Table 1). Age-adjusted incidence rates of distant-stage colorectal cancer for African Americans were 25.9/100,000 in 1992 and 28.1/100,000 in 2004, reaching a high of 30.4/100,000 in 1993 (Table 2). Rates among whites were 16.6/100,000 in 1992 and 13.0/100,000 in 2004. The relative risk of distant-stage colorectal cancer was significantly elevated in African Americans as compared to whites throughout the period from 1992 to 2004. On this relative scale, in 1992, African Americans were 60% more likely to be diagnosed with distant-stage colorectal cancer as compared to whites and by 2004 African Americans were 120% more likely than whites to be diagnosed with distant-stage colorectal cancer. The rate difference between African Americans and whites ranged from 5.9/100,000 to 15.1/100,000, suggesting a possible, though inconsistent, increase in the absolute disparity over time. Statistically significant declines in distant-stage colorectal cancer incidence were observed for whites (APC = −1.6; 95% CI −2.3, −0.9) but not for African Americans (APC = 0.5; 95% CI −0.8, 1.9; Fig. 2). When we stratified the rates further by gender, we saw similar widening of the racial disparity in the incidence of distant-stage colorectal cancer for both men and women between 1992 and 2004 (data not shown).

Fig. 2

Trends in distant-stage colorectal cancer in African American and white males and females from 1992 to 2004.

Prostate Cancer

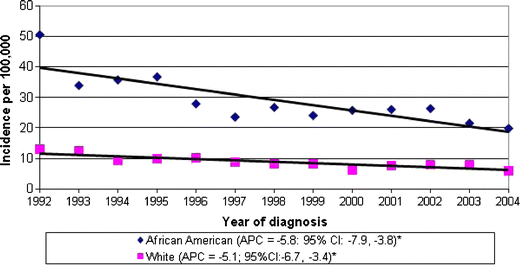

A total of 2,801 cases of distant-stage prostate cancers were diagnosed in African American (791) and white (2,010) men from 1992 to 2004. A higher percentage of African American (16.8%) cases were diagnosed in the youngest age group of 50–54 years of age as compared to whites (15.5%; Table 1). The age-adjusted incidence rate for distant-stage prostate cancer in African American men ranged from 50.5/100,000 in 1992 to 19.8/100,000 in 2004 (Table 2). For white men, the incidence of distant-stage prostate cancer was 13.1/100,000 in 1992 and 6.0/100,000 in 2004. The rate difference for prostate cancer ranged from 37.4/100,000 to 13.8/100,000 and decreased over time. African American men had an incidence that was 2.7 to 4.1 times the incidence of white men throughout this period. Statistically significant declines in the incidence of distant-stage prostate cancer were seen for both African American (APC = −5.8, 95% CI −7.9, −3.8) and white men (APC = −5.1, 95% CI −6.7, −3.4) from 1992 to 2004 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3

Trends in distant-stage prostate cancer in African American and white males from 1992 to 2004.

Discussion

Before interpreting our results, it is important to acknowledge that this is an ecologic study. Causation can certainly not be inferred, but descriptive studies like this can provide insight into demographic trends and generate hypotheses. Our goal was to assess how disparities in the incidence rates of distant-stage breast, colorectal, and prostate cancers have changed during an era when screening tests for each of these cancers were available.

The data indicate that, on both an absolute and relative scale, African American women 40–64 years of age continue to experience higher incidence rates of distant-stage breast cancer compared to white women, with no evidence that this disparity either narrowed or widened from 1992 to 2004. This result is consistent with prior studies documenting higher risks of advanced-stage breast cancer and of breast cancer mortality among African Americans compared to whites [1, 3, 26, 27]. With respect to screening, this result is also consistent with data indicating that mammography screening rates are similar among both African American and white women in the USA. In the 2000 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), the proportion of women receiving a screening mammogram in the past 2 years was 67.6% for African Americans and 71.2% for whites, a difference that was not statistically significant [28]. The relative equality in screening rates between African Americans and whites and our observation that the disparity with respect to distant-stage disease incidence has held constant suggest that work in addition to promoting access to breast cancer screening is needed to reduce these disparities. In particular, the higher rate of hormone-receptor-negative, and perhaps more aggressive, breast cancers in African American women noted in several recent studies [11, 12] suggests that differences in tumor biology contribute to the late stage at diagnosis of breast cancer in African American women. Studies of breast tumor hormone receptor status have consistently noted that breast cancer subtypes characterized by ER− disease are less likely to be detected through routine screening and therefore patients with ER− tumors often present at a later stage than patients with ER+ tumors [15, 16]. Differences in risk factors for ER+ disease, such as the use of menopausal hormone therapy (HT) [29], are not distributed equally between racial groups. On average, whites are more likely to use HT than African Americans [30] which may partially explain the higher proportion of ER− tumors in African American women. More research is needed to determine specific risk factors for ER− disease.

With respect to colorectal cancer, on both an absolute and relative scale, the data indicate that the disparity in incidence of distant-stage colorectal cancer between African Americans and whites is widening. The APCs in distant-stage colorectal cancer statistically significantly fell by 1.6% per year among whites, while increasing slightly (though not statistically significantly) among African Americans by 0.5%. The relative incidence rate of distant-stage colorectal cancer increased in African Americans vs. whites increased from a 1.6-fold difference in 1992 to a 2.2-fold difference in 2004. Again, our finding of a disparity in incidence of distant-stage colorectal cancer is consistent with prior studies documenting that African Americans have higher risks of distant-stage colorectal cancer and colorectal cancer mortality compared to whites [5, 31]. With respect to 2000 NHIS data on colorectal screening, rates of utilization of a home blood stool test within the past year or a colorectal endoscopy in the past 5 years are similar in African American men compared to white men (40.1% vs. 41.7%) but are marginally statistically significantly different in African American women compared to white women (31.8% vs. 38.7%) [28]. It is somewhat difficult to interpret these data though because colorectal endoscopy is a considerably superior colorectal cancer screening test compared to a blood stool test with respect to both sensitivity and specificity, and so it is unclear the extent to which rates of colorectal endoscopy itself are different between African Americans and whites in the general population. It is possible that more common utilization of screening colorectal endoscopy among whites compared to African Americans could be one of the factors contributing to the widening of the distant-stage colorectal cancer disparity in recent years.

Our prostate cancer data illustrate the different conclusions that can be reached depending on whether one focuses on absolute or relative disparities. Visually, Fig. 3 demonstrates a clear narrowing of this disparity on an absolute scale as the difference in incidence rates of distant-stage prostate cancer between African American and white men declined from 37.4/100,000 to 13.8/100,000 from 1992 to 2004. However, since rates also declined among whites, the relative difference in incidence held essentially constant with about a threefold difference in rates among African Americans vs. whites across the study period. The 2000 NHIS data on prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening rates indicate that 37.4% of African American men and 41.9% of white men have been screened for prostate cancer within the past year [28]. More recent NHIS data from 2005 indicate though that African American men were more likely than white men to report having ever had a PSA test (odds ratio = 1.85, 95% CI 1.05–3.25) [32]. The role of PSA testing remains controversial, and its abilities to detect prostate cancer at earlier stages and to reduce prostate cancer mortality are unclear. However, to the extent to which PSA testing is useful for detecting disease early, this coupled with the higher rates of PSA testing among African Americans compared to whites and the absolute reduction in the disparity in incidence of distant-stage prostate cancer we observed is consistent with the hypothesis that increased prostate cancer screening among African American men has had an impact on reducing this disparity. Aside from the role of PSA screening, it is possible that the identification of African American race as a risk factor for prostate cancer has led to targeted interventions for early detection and prevention of prostate cancer that have reduced the racial disparity in distant-stage prostate cancer incidence.

In addition to its limitations as an ecologic study, other limitations of this study relate to its data source. Although this is a population-based study, it only includes people residing in areas of the USA covered by one of the 12 SEER registries included in this analysis, approximately 14% of the US population [22]. This population is more urban than the rest of the USA [33], and so our results may not be generalizable to the whole US population. In addition, data on race/ethnicity are based on medical record reviews only, so misclassification is a concern. However, a recent study comparing SEER data on race and ethnicity to self-report data demonstrated an agreement between the two sources of over 90% [34].

In conclusion, disparities in the incidence of distant-stage breast, colorectal, and prostate cancers experienced by African Americans compared to whites have stayed relatively constant for breast cancer, increased for colorectal cancer, and decreased for prostate cancer from 1990 to 2004 on an absolute scale. For all of these cancer sites, African Americans continue to have a disproportionately high disease burden, so continued multipronged efforts aimed at improving access to breast, colorectal, and prostate prevention, screening, diagnostic, and treatment services are warranted. Ongoing research is needed to determine the causes of these trends and their relative contributions in order to design additional targeted efforts to reduce these cancer disparities.

References

- Boyer-Chammard A, Taylor TH, Anton-Culver H (1999) Survival differences in breast cancer among racial/ethnic groups: a population-based study. Cancer Detect Prev 23(6):463–473

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Bradley CJ, Given CW, Roberts C (2002) Race, socioeconomic status, and breast cancer treatment and survival. J Natl Cancer Inst 94(7):490–496

PubMed Google Scholar - Joslyn SA, West MM (2000) Racial differences in breast carcinoma survival. Cancer 88(1):114–123

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Shavers VL, Harlan LC, Stevens JL (2003) Racial/ethnic variation in clinical presentation, treatment, and survival among breast cancer patients under age 35. Cancer 97(1):134–147

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Cress RD, Morris CR, Wolfe BM (2000) Cancer of the colon and rectum in California: trends in incidence by race/ethnicity, stage, and subsite. Prev Med 31(4):447–453

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Chu KC, Tarone RE, Freeman HP (2003) Trends in prostate cancer mortality among black men and white men in the United States. Cancer 97(6):1507–1516

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Merrill RM, Lyon JL (2000) Explaining the difference in prostate cancer mortality rates between white and black men in the United States. Urology 55(5):730–735

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Jones BA, Liu WL, Araujo AB, Kasl SV, Silvera SN, Soler-Vila H et al (2008) Explaining the race difference in prostate cancer stage at diagnosis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 17(10):2825–2834

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Elledge RM, Clark GM, Chamness GC, Osborne CK (1994) Tumor biologic factors and breast cancer prognosis among white, Hispanic, and black women in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst 86(9):705–712

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Elmore JG, Moceri VM, Carter D, Larson EB (1998) Breast carcinoma tumor characteristics in black and white women. Cancer 83(12):2509–2515

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Li CI, Malone KE, Daling JR (2002) Differences in breast cancer hormone receptor status and histology by race and ethnicity among women 50 years of age and older. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 11(7):601–607

PubMed Google Scholar - Carey LA, Perou CM, Livasy CA, Dressler LG, Cowan D, Conway K et al (2006) Race, breast cancer subtypes, and survival in the Carolina Breast Cancer Study. JAMA 295(21):2492–2502

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Powell IJ, Banerjee M, Sakr W, Grignon D, Wood DP Jr, Novallo M et al (1999) Should African–American men be tested for prostate carcinoma at an earlier age than white men? Cancer 85(2):472–477

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Dunnwald LK, Rossing MA, Li CI (2007) Hormone receptor status, tumor characteristics, and prognosis: a prospective cohort of breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res 9(1):R6

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Porter PL, El-Bastawissi AY, Mandelson MT, Lin MG, Khalid N, Watney EA et al (1999) Breast tumor characteristics as predictors of mammographic detection: comparison of interval- and screen-detected cancers. J Natl Cancer Inst 91(23):2020–2028

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Collett K, Stefansson IM, Eide J, Braaten A, Wang H, Eide GE et al (2005) A basal epithelial phenotype is more frequent in interval breast cancers compared with screen detected tumors. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 14(5):1108–1112

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Rohrmann S, Sutcliffe CG, Bienstock JL, Monsegue D, Akereyeni F, Bradwin G et al (2009) Racial variation in sex steroid hormones and the insulin-like growth factor axis in umbilical cord blood of male neonates. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 18(5):1484–1491

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Winters SJ, Brufsky A, Weissfeld J, Trump DL, Dyky MA, Hadeed V (2001) Testosterone, sex hormone-binding globulin, and body composition in young adult African American and Caucasian men. Metabolism 50(10):1242–1247

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Ingles SA, Ross RK, Yu MC, Irvine RA, La Pera G, Haile RW et al (1997) Association of prostate cancer risk with genetic polymorphisms in vitamin D receptor and androgen receptor. J Natl Cancer Inst 89(2):166–170

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Ross RK, Pike MC, Coetzee GA, Reichardt JK, Yu MC, Feigelson H et al (1998) Androgen metabolism and prostate cancer: establishing a model of genetic susceptibility. Cancer Res 58(20):4497–4504

CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Travis RC, Schumacher F, Hirschhorn JN, Kraft P, Allen NE, Albanes D et al (2009) CYP19A1 genetic variation in relation to prostate cancer risk and circulating sex hormone concentrations in men from the Breast and Prostate Cancer Cohort Consortium. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 18(10):2734–2744

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Ries LAG, Krapcho M, Stinchcomb DG, Howlader N, Horner MJ, Mariotto A, Miller BA, Feuer EJ, Altekruse SF, Lewis DR, Clegg L, Eisner MP, Reichman M, Edwards BK (eds) (2008) SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2005. National Cancer Institute, Bethesda

Google Scholar - Young J, Roffers S, Ries L, Fritz A, Hurlbut A (2001) SEER summary staging manual—2000: codes and coding instructions. National Cancer Institute, Bethesda

Google Scholar - Kim HJ, Fay MP, Feuer EJ, Midthune DN (2000) Permutation tests for Joinpoint regression with applications to cancer rates. Stat Med 19(3):335–351

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Harper S, Lynch J (2005) Methods for measuring cancer disparities: a review using data relevant to healthy people 2010 cancer-related objectives. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda

Google Scholar - Anderson WF, Reiner AS, Matsuno RK, Pfeiffer RM (2007) Shifting breast cancer trends in the United States. J Clin Oncol 25(25):3923–3929

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Smigal C, Jemal A, Ward E, Cokkinides V, Smith R, Howe HL et al (2006) Trends in breast cancer by race and ethnicity: update 2006. CA Cancer J Clin 56(3):168–183

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Swan J, Breen N, Coates RJ, Rimer BK, Lee NC (2003) Progress in cancer screening practices in the United States: results from the 2000 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer 97(6):1528–1540

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Chen WY, Hankinson SE, Schnitt SJ, Rosner BA, Holmes MD, Colditz GA (2004) Association of hormone replacement therapy to estrogen and progesterone receptor status in invasive breast carcinoma. Cancer 101(7):1490–1500

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Daling JR, Malone KE, Doody DR, Voigt LF, Bernstein L, Marchbanks PA et al (2003) Association of regimens of hormone replacement therapy to prognostic factors among women diagnosed with breast cancer aged 50–64 years. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 12(11 Pt 1):1175–1181

CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Chu KC, Tarone RE, Chow WH, Alexander GA (1995) Colorectal cancer trends by race and anatomic subsites, 1975 to 1991. Arch Fam Med 4(10):849–856

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Drake BF, Lathan CS, Okechukwu CA, Bennett GG (2008) Racial differences in prostate cancer screening by family history. Ann Epidemiol 18(7):579–583

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Wingo PA, Jamison PM, Hiatt RA, Weir HK, Gargiullo PM, Hutton M et al (2003) Building the infrastructure for nationwide cancer surveillance and control—a comparison between the National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR) and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program (United States). Cancer Causes Control 14(2):175–193

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Clegg LX, Reichman ME, Hankey BF, Miller BA, Lin YD, Johnson NJ et al (2007) Quality of race, Hispanic ethnicity, and immigrant status in population-based cancer registry data: implications for health disparity studies. Cancer Causes Control 18(2):177–187

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- Department of Epidemiology, University of Washington School of Public Health, 1959 NE Pacific Street, Health Sciences Building F-262, Box 357236, Seattle, WA, 98195-7236, USA

Jean A. McDougall & Christopher I. Li - Division of Public Health Sciences, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, M4-C308, P.O. Box 19024, Seattle, WA, 98109-1024, USA

Jean A. McDougall & Christopher I. Li

Authors

- Jean A. McDougall

- Christopher I. Li

Corresponding author

Correspondence toJean A. McDougall.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McDougall, J.A., Li, C.I. Trends in Distant-Stage Breast, Colorectal, and Prostate Cancer Incidence Rates from 1992 to 2004: Potential Influences of Screening and Hormonal Factors.HORM CANC 1, 55–62 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12672-009-0002-1

- Received: 21 October 2009

- Accepted: 17 December 2009

- Published: 06 February 2010

- Issue Date: February 2010

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12672-009-0002-1