Origin of the chromosomal radiation of Madeiran house mice: a microsatellite analysis of metacentric chromosomes (original) (raw)

Introduction

The Robertsonian (Rb) fusion chromosomal rearrangement (the joining of two acrocentrics to form a metacentric) is commonly involved in karyotypic differences between and within animal species (King, 1993; Searle, 1993). Given the potential of chromosomal rearrangements such as this to cause an interruption of gene flow, and therefore speciation (King, 1993; Butlin, 2005; Faria and Navarro, 2010), it is important to investigate their origin and impact in natural systems. The western house mouse (Mus musculus domesticus) is very variable chromosomally (Piálek et al., 2005): while the standard karyotype of the house mouse consists of 40 acrocentric chromosomes, there are chromosomal forms with different combinations of autosomal metacentrics, which represent the products of Rb fusions or derivatives of these (that is, whole-arm reciprocal translocations: the exchange of chromosome arms between metacentrics or between metacentrics and acrocentrics). Where metacentrics are fixed within a population, they define a metacentric race. Because each metacentric involves a reduction in chromosome number, the diploid number that characterises such races can be as low as 2_n_=22 (nine pairs of metacentrics).

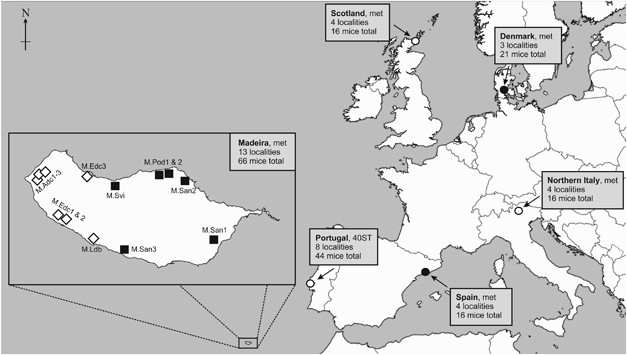

Here we focus on the notable chromosomal radiation in the house mice on the island of Madeira (Figure 1), where there are six metacentric races with diploid chromosome numbers ranging from 22 to 28 (Britton-Davidian et al., 2000). Of the 20 metacentric chromosomes, 7 found on Madeira have been documented elsewhere in the distribution of M. m. domesticus (Piálek et al., 2005). This includes metacentric 3.8, which phylogenetic studies suggest is likely to be one of the first Rb fusions to have arisen on the island (Britton-Davidian et al., 2005; White et al., 2010). As the proposed north European source of the Madeiran mice (based on mitochondrial (mt) DNA analysis: Gündüz et al. (2001a) and Förster et al. (2009)) includes a region of Denmark inhabited by races fixed for metacentric 3.8 (Piálek et al. (2005), and references therein), it is possible that this metacentric was introduced to Madeira from Denmark during colonisation. Such (human-mediated) long-distance dispersal of metacentric-bearing mice has already been confirmed for some European populations (Riginos and Nachman, 1999). In the case of Madeira, such a scenario may help to explain the extensive chromosomal diversification observed. Further, it has been reported that the presence of an Rb fusion in mouse laboratory stocks appears to predispose such stocks to further Rb fusions (Nachman and Searle (1995), and references therein). This presents the intriguing possibility that a metacentric introduced during colonisation could have led to a fusion ‘cascade’ on Madeira.

Figure 1

Map indicating the sampling localities used in this study; the island of Madeira is enlarged (left). Localities in continental Europe are indicated by circles (○), filled circles (●) represent localities where metacentric 3.8 is present. Text in boxes gives the chromosome status of M. m. domesticus at these localities (met=metacentric races; 40ST=standard karyotype (all-acrocentric) mice; see Table 1 for details); the number of sampling localities and total number of mice per geographic region is also indicated. Madeiran sampling localities are shown in the inlay; see Table 1 for details about races. (▪) Races with metacentric 3.8; and (◊) races with metacentrics 3.14 and 8.11.

In this study, we use mapped microsatellite loci to investigate the Madeiran metacentric races. Our first aim was to investigate the possibility that metacentric 3.8 was introduced to Madeira. For this purpose, microsatellite loci closely linked to this Rb fusion (that is, loci mapping to the centromeres of the constituent chromosomes 3 and 8) were genotyped in mice from Madeira and elsewhere in the distribution of M. m. domesticus in Europe, including chromosome races with metacentric 3.8. Such loci have previously proven effective in demonstrating a shared evolutionary origin of a metacentric in the house mouse (Riginos and Nachman, 1999). Races with metacentric 3.8 from Denmark represent a potential source from a north European origin, if the metacentric was introduced during colonisation. An alternative source of metacentric 3.8, a race in Spain, may have contributed this metacentric subsequent to colonisation.

Additionally, we aimed to investigate the genetic input from mainland Portugal to Madeira. The island is a Portuguese dependency and passive transport (by humans) of mice from mainland Portugal to Madeira is expected to have occurred since the island’s settlement in the 15th century. In spite of a virtual absence of Portuguese mtDNA sequences on Madeira (Gündüz et al., 2001a; Förster et al., 2009), there is high genic similarity between most Madeiran metacentric races and Portuguese house mice at nuclear allozyme markers (Britton-Davidian et al., 2007). It has been proposed that mice introduced from Portugal likely represent a secondary wave of colonisers after an initial colonisation from northern Europe (Britton-Davidian et al., 2007; Förster et al., 2009). Several Portuguese mouse populations that could have contributed to this second wave of colonisers were included in the study (that is, from cities along the Atlantic coast with active harbours since the settlement period of Madeira from Portugal).

Finally, chromosomal speciation theory predicts that karyotypic divergence facilitates genetic divergence (for example, King, 1993), particularly in those chromosome regions involved in the karyotypic rearrangement(s) (for example, Faria and Navarro, 2010). We aimed to investigate this in the metacentric races of Madeira. As our efforts were focused on chromosomes 3 and 8, the metacentric races on Madeira were considered as two karyotypic groups: those with metacentric 3.8 and those with metacentrics 3.14 and 8.11 (see Figure 1). Gene flow between the metacentric races was investigated using microsatellite loci mapping to three chromosome regions (proximal, interstitial and distal) of chromosomes 3 and 8. As the formation of metacentric chromosomes by Rb fusions or whole-arm reciprocal translocations involves the centromere, it was predicted that loci closely linked to the centromere (that is, proximal loci) would show an interruption to gene flow between the karyotypic groups. It was not expected that gene flow at loci located in the other two chromosome regions (that is, interstitial and distal loci) would be affected by the chromosome disposition (that is, 3.8 versus 3.14 and 8.11).

Materials and methods

Specimens

The 179 mice used in this study were collected at 36 localities in six geographical regions: Madeira, Portugal, Spain, Italy, Denmark and Scotland (Figure 1). Collection dates and karyotype information are shown in Table 1.

Table 1 Specimen details

Karyotypes of mice were determined in previous studies, as follows: Madeira and Portugal, Förster et al. (2009); Denmark, Smadja et al. (2004); Spain, Gündüz et al. (2001b); northern Italy, Hauffe and Searle (1993) and Panithanarak et al. (2004); and Scotland, Searle (1991), Searle et al. (1993) and Palmer (1997).

Microsatellite typing

In all, 24 loci were chosen based on their genetic distance from the centromere (see Supplementary Table S1 for details). Proximal loci: D3mit60, D3mit117, D3mit221, D3mit62, D8mit155, D8mit58, D8mit124 and D8mit171. Interstitial loci: D3mit72, D3mit156, D3mit283, D3mit28, D8mit54, D8mit193, D8mit130 and D8mit178. Distal loci: D3mit87, D3mit116, D3mit163, D3mit19, D8mit52, D8mit93, D8mit56 and D8mit92.

Tail tips, spleens and/or toe clippings were stored in 100% ethanol and maintained at 4 °C. DNA was extracted using the Qiagen DNeasy Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) following the manufacturers’ instructions. The polymerase chain reaction volume was 5 μl; polymerase chain reactions were carried out using the Qiagen Multiplex PCR Kit (Qiagen) following the instructions for multiplexing microsatellite loci. Reverse primers were labelled with one of the fluorescent dyes: FAM, HEX, VIC, NED or PET. Amplifications were carried out following the ‘microsatellite cycling protocol’ of the Qiagen Multiplex PCR Kit.

When microsatellites were labelled with FAM or HEX, alleles were separated using an Applied Biosystems 377a sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA); when they were labelled with FAM, VIC, NED or PET, they could be separated using an Applied Biosystems 3130xl sequencer (Applied Biosystems). GENEMAPPER v.4.0 (Applied Biosystems) was used to determine allele sizes. Alleles were scored two times; peak morphologies and sizes were assessed by eye. Alleles were allocated using histograms of raw allele sizes given to two decimal places of a base pair.

Analysis

MICROCHECKER v.2.2.3 (Van Oosterhout et al., 2004) was used to test for null alleles, large allele drop-out and scoring errors. One locus (D8mit92) was removed from the data set because of the presence of null alleles. Two further loci were excluded because they either did not amplify consistently (D3mit62) or had peak profiles with extensive stuttering (D3mit28), making it impossible to score with confidence. All further analyses were carried out with the remaining 21 loci (Supplementary Table S1).

GENEPOP v.3.4 (Raymond and Rousset, 1995) was used to test deviations from Hardy–Weinberg proportions. Observed heterozygosity (_H_O) and unbiased expected heterozygosity (_H_E) were estimated following Nei (1978) in POPGENE v.1.32 (Yeh et al., 1997).

F-statistic (FST) values were calculated as θ (Weir and Cockerham, 1984) in FSTAT v.2.9.3.2 ([Goudet, 2002](/articles/hdy2012107#ref-CR22 "Goudet J (2002). FSTAT 2.9.3.2. Lausanne: Switzerland. Available at: http://www2.unil.ch/popgen/softwares/fstat.htm

.")). FSTAT was also used to estimate allelic frequencies. R-statistic (RST) values were determined in RSTCALC v.2.2 ([Goodman, 1997](/articles/hdy2012107#ref-CR21 "Goodman SJ (1997). rst calc: a collection of computer programs for calculating unbiased estimates of genetic differentiation and gene flow from microsatellite data and determining their significance. Mol Ecol 6: 881–885.")). RST values were calculated by first averaging variance components over loci, following [Slatkin (1995)](/articles/hdy2012107#ref-CR46 "Slatkin M (1995). A measure of population subdivision based on microsatellite allele frequencies. Genetics 139: 457–462."). For multilocus estimates, data were ‘globally standardised’ with the _standard.exe_ application of RSTCALC, so that loci with low variances may contribute to the final estimates of RST. For the two summary statistics, _P-_values were corrected for multiple comparisons when appropriate (Bonferroni correction).Several analyses were carried out in the statistical programming environment R (http://www.cran.r-project.org/). We calculated Spearman’s correlation coefficients (and their significance levels) to examine if levels of genetic diversity (_H_O, _H_E, mean number of alleles) were affected by differences in sampling. A principal component analysis (PCA) was carried out using the R package adegenet v.1.3-3 (Jombart, 2008), to examine the genetic relationship among localities (at two scales: by locality and by geographic region). Three further PCAs were carried out to determine the genetic differentiation among the six Madeiran races (13 localities) by chromosome region (proximal, interstitial and distal). To examine to what degree chromosome disposition (3.8 versus 3.14 and 8.11) and chromosome race affected population genetic structuring, we carried out an analysis of molecular variance with four hierarchical levels using the R package Hierfstat v.0.04-6 (Goudet, 2005).

Results

Microsatellite variation

The microsatellite loci were highly polymorphic. Considering 179 mice from 36 localities in six geographic regions (Table 1), 331 alleles were found for the 21 microsatellite loci. The mean number of alleles per locus varied between localities, with a range of 1.2–4.7 (overall mean=3.5; Table 2). This was significantly correlated with sample size (_r_s=0.534; P<0.01), as expected with small but varying sample sizes. _H_E’s are also significantly correlated with sample size (_r_s=0.38; _P_=0.02). They show values between 0.069 (I.Ser) and 0.672 (M.San3), similar to the range of _H_O values: from 0.119 (I.Ser) to 0.771 (P.Lag). Partitioning of genetic diversity was significant under both the infinite-allele model (FST=0.285, P<0.001) and the stepwise-mutation model (RST=0.319, P<0.001). These values compare to previous microsatellite studies in M. m. domesticus (Dallas et al., 1998; Panithanarak et al., 2004; Franchini et al., 2008, 2010).

Table 2 Summary of multilocus (21 microsatellite loci) population genetic analyses

Genetic differentiation between geographic regions

Summary statistics (FST and RST) for pairwise comparisons between geographic regions are shown in Table 3. Localities within geographic regions were pooled with the exception of Madeira, for which specimens were pooled into two groups: mice with metacentric 3.8 versus those without (that is, all specimens with 3.14 and 8.11). This was carried out because of interest in the amount of differentiation between these two karyotypic groups on Madeira (see below). Differentiation among geographic regions measured under the infinite-allele model and stepwise-mutation model was highly significant (Table 3); RST values tended to be higher in this analysis (FST: 0.067–0.289; RST: 0.101–0.478). Although the extent of differentiation was sometimes inconsistent between FST and RST, both summary statistics show that the pairwise comparison between Madeiran samples with and without metacentric 3.8 have the lowest values, followed by pairwise comparisons involving either of the Madeiran samples and the Portugal sample (Table 3).

Table 3 Estimates of pairwise genetic differentiation (FST and RST) between geographic regions based on 21 microsatellite loci

Relationship of Madeiran metacentric populations and other localities

Selectively neutral loci linked to the centromere of a metacentric (that is, proximal loci) are the most likely to reflect accurately the evolutionary history of the chromosome involved (Riginos and Nachman, 1999). Regarding the colonisation of Madeira, use of such loci on mouse chromosomes 3 and 8 enabled us to examine if metacentric 3.8 was introduced to Madeira during colonisation of the island.

Table 4 shows pairwise FST values (proximal loci only) between Madeiran localities characterised by metacentric 3.8 and the remaining 30 localities. This summary statistic does not indicate a close genetic relationship between Madeiran mice with metacentric 3.8 and mice carrying this Rb fusion from Denmark (DK.Lu, DK.Sm and DK.Sn) or Spain (E.Gar). Rather, the data on proximal loci recapitulates the pattern seen when examining all 21 microsatellites (Table 3): the lowest pairwise values are observed among the two karyotypic groups on Madeira (FST: 0.125–0.405), followed by comparisons involving Portuguese localities (FST: 0.206–0.413).

Table 4 Pairwise FST values between Madeiran localities characterised by metacentric 3.8 and the remaining 30 localities

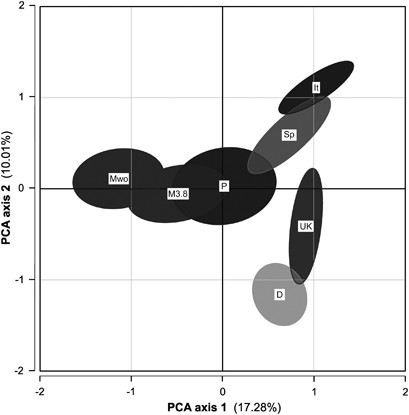

A PCA based on only proximal loci (Figure 2) reflects the genetic affinities discerned from the summary statistics: the two Madeiran samples (mice with and without metacentric 3.8) show genetic similarity, and are clearly separated from all but the Portuguese mice along the first principal component (which explains 17.28% of variation). The same analysis conducted at the scale of locality (Supplementary Figure S1) also shows no evidence of genetic similarity between Madeiran, Danish or Spanish localities characterised by metacentric 3.8. In the latter PCA, three Portuguese localities (Setubal, Sines and Tavira) appear genetically most similar to the Madeiran populations characterised by metacentric 3.8. However, these three Portuguese localities do not stand out based on FST values (proximal loci only; Table 4), in comparison to other Portuguese localities, or Madeiran populations characterised by metacentrics 3.14 and 8.11. It is worth noting that the populations on Madeira characterised by metacentric 3.8 occupy the eastern portion of the island (Figure 1), where the main port and airport are located; this is the area most likely to receive mouse immigrants from Portugal, and mice here show within-race polymorphism involving metacentrics and their acrocentric homologues (Britton-Davidian et al., 2005, 2007). However, it has not been conclusively determined if this chromosomal polymorphism is due to immigration of standard karyotype (all-acrocentric) mice, and no mice with what could be considered Portuguese mtDNA haplotypes have been detected in this area (Gündüz et al., 2001a; Förster et al., 2009).

Figure 2

PCA plot showing relationship among M. m. domesticus in this study by geographic region (seven proximal loci; see Supplementary Table S1) on first two principal components. Ellipses capture 95% variation among mice from a given geographic region. M3.8, Madeiran specimens with metacentric 3.8; Mwo, Madeiran specimens without metacentric 3.8; P, Portugal; Sp, Spain; It, Northern Italy; UK, Scotland; and D, Denmark.

Relationship among Madeiran karyotypic groups

Overall differentiation on the island was highly significant when considering all loci and all individuals (FST=0.129; RST=0.168; P<0.001 in both cases).

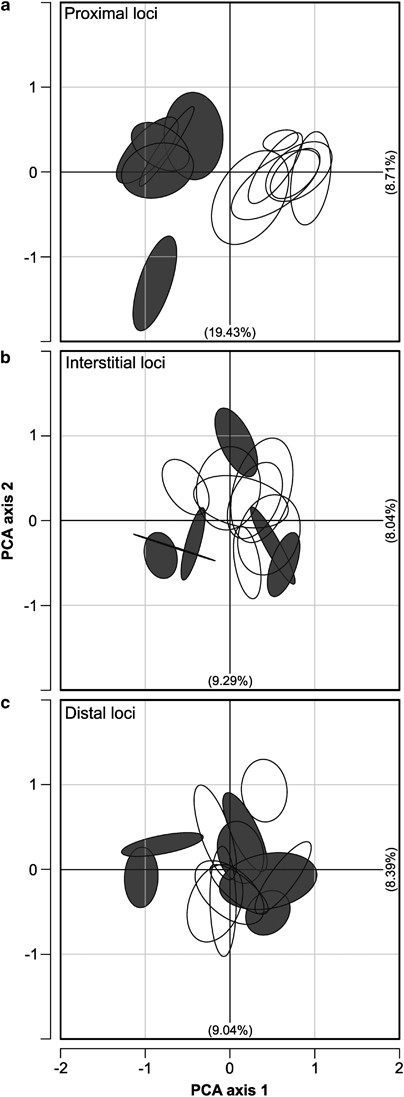

To examine the impact of chromosome disposition (metacentric 3.8 versus 3.14 and 8.11) and chromosome race on genetic structure, we conducted an analysis of molecular variance at four hierarchical levels: (1) among karyotypic groups (3.8 versus 3.14 and 8.11); (2) among chromosome races within karyotypic groups; (3) among populations within races; and (4) within populations. The results are shown in Table 5. For this analysis, we examined the three chromosome regions separately (proximal, interstitial and distal). The proximal region shows a significant proportion of variation partitioned among karyotypic groups (14.05%), whereas the interstitial and distal regions do not (Table 5). At the lower hierarchical levels, all three chromosome regions show significant genetic structuring—with the ‘within-population’ level harbouring by far the greatest proportion of variation. Of note is that the proportion of variation at proximal loci is greater between karyotypic groups (14.05%) than between races within these groups (4.09%) or among populations within races (5.78%). At the latter two hierarchical levels, the proportion of variation at proximal loci lays in the range of the other two chromosome regions (Table 5).

Table 5 AMOVA among Madeiran mice, by chromosome region and by locus

Three PCAs were carried out on the Madeiran data set, each corresponding to one of the three chromosome regions investigated (Figure 3). The plot for proximal loci (Figure 3a) shows a clear separation of specimens homozygous for metacentric 3.8 and its monobrachial homologues on the first principal component (which explains 19.43% of variation). The PCA plots for the interstitial and distal regions (Figures 3b and c) do not show a similar separation of the two karyotypic groups.

Figure 3

PCA plot showing relationship among Madeiran metacentric races of M. m. domesticus. Ellipses capture 95% variation among mice from a given population. Specimens homozygous for metacentric 3.8 are represented by filled ellipses (six populations), whereas those homozygous for its monobrachial homologues 3.14 and 8.11 are represented by open ellipses (seven populations). PCAs are shown by chromosome region: (a) proximal loci; (b) interstitial loci; and (c) distal loci.

The high differentiation in the proximal region between the karyotypic groups appears to be more a reflection of the loci on chromosome 3 (three loci, FST=0.237, P<0.001) than those on chromosome 8 (four loci, FST=0.081, _P<_0.001). Our outlier analysis identified two proximal loci on chromosome 3 as having significantly higher FST values than expected given the level of genetic diversity and differentiation among Madeiran specimens, but tests of neutrality do not suggest that this is the result of selection (Supplementary Figure S2). Supplementary Table S2 shows the frequencies of alleles at three proximal loci that appear exclusive or nearly exclusive to one of the karyotypic groups; those on chromosome 3 show the strongest allelic association with karyotype.

Discussion

Common versus multiple origin of Rb metacentric 3.8

For metacentrics generated by Rb fusion, selectively neutral loci linked to the centromere are most likely to reflect the evolutionary history of the chromosome concerned (Riginos and Nachman, 1999). Neither summary statistics nor principal component analyses were able to demonstrate strong genetic similarity at such loci between any of the mainland populations of house mice characterised by metacentric 3.8 and those on Madeira with this chromosome. Instead, our microsatellite results and the allozyme results of Britton-Davidian et al. (2007) demonstrate an affinity between Madeiran mice and those on the Portuguese mainland.

The chromosomal divergence on Madeira is remarkable, particularly given the timeframe within which this must have arisen (Förster et al., 2009). The introduction of a metacentric from elsewhere could potentially have contributed to the karyotypic diversity observed. We chose to investigate metacentric 3.8 in this context, because it was likely one of the earliest metacentrics to arise on Madeira (Britton-Davidian et al., 2005; White et al., 2010) and its presence in the proposed colonisation source (Gündüz et al., 2001a; Förster et al., 2009). Our results do not support the introduction of metacentric 3.8 during colonisation from northern Europe (Denmark), or thereafter from Spain.

Relationship of Madeiran metacentric mice with those of elsewhere

Island populations are expected to show genetic signatures of their source area, particularly when oceanic barriers greatly reduce post-colonisation gene flow (Avise, 2000). The large distance of Madeira to the closest continental landmass (600 km) supports a human-mediated colonisation event linked to the arrival of seafarers on the island. Phylogenetic analyses with mtDNA provide very strong evidence for a north European source of the first mouse colonists (Gündüz et al., 2001a; Förster et al., 2009). This result was unexpected because of the absence of historical documentation for a north European presence on the archipelago, whereas the human association with Portugal from the fifteenth century onward is well documented (Albuquerque and Vieira, 1988). Our analysis of microsatellite variation confirms results of previous studies indicating gene flow from mainland Portugal to Madeira (Britton-Davidian et al., 2007; Förster et al., 2009).

The high level of genetic diversity observed by us and Britton-Davidian et al. (2007) for two types of nuclear marker (microsatellites, allozymes) is unexpected considering (i) the process of chromosomal divergence and (ii) the fragmentation of habitat on Madeira suitable for house mouse occupation. Britton-Davidian et al. (2007) suggested that a significant influx of mice from Portugal might have taken place during the rapid expansion of farming communities on Madeira, thus potentially introducing variation to a genetically impoverished Madeiran mouse population. This interpretation is consistent with the genetic similarity between Madeiran mouse populations and those of mainland Portugal (this study; Britton-Davidian et al., 2007), as well as the high levels of variation detected at nuclear markers. A similar situation has been reported for mouse populations on Mediterranean islands, which show no reduction in genetic variability compared with mainland populations, presumably as a result of multiple (human-mediated) introductions of house mice (Navarro and Britton-Davidian, 1989).

However, a high expansion rate, which is consistent with the mtDNA results (Förster et al., 2009), could also explain the high levels of microsatellite and allozyme variability detected (Zenger et al., 2003). In addition, microsatellite studies investigating population bottlenecks (for example, Keller et al., 2001; Busch et al., 2007) have demonstrated that very low levels of immigration (on the level of a few individuals) can recover levels of variability to pre-bottleneck levels in a small number of generations, even when the incidence of inbreeding is high. It is thus difficult to ascertain conclusively to what extent Portuguese mouse immigrants have contributed to the current high levels of variability, although the genetic similarity at nuclear loci between Madeiran and Portuguese mice does provide compelling evidence for an influx of individuals. Of note is that the microsatellite data suggest that the Madeiran populations most likely to come into contact with mouse immigrants (that is, closest to the port city of Funchal) are those that show signs of gene flow from mainland Portugal.

Highly divergent chromosome races on Madeira show low-to-moderate genetic differentiation

While genetic differentiation among the Madeiran metacentric mice is highly significant (FST=0.129; RST=0.168; P<0.001 in both cases), the degree of differentiation observed is lower than may be expected considering the extensive chromosomal divergence on the island, which involves 20 or more chromosomal rearrangements (Britton-Davidian et al., 2005; White et al., 2010). Previous studies in house mice involving chromosomally less divergent races typically show higher levels of genetic differentiation at microsatellite loci (FST=0.39, 13 microsatellite loci (Panithanarak et al., 2004); _F_ST=0.187, 8 microsatellite loci (Franchini et al., 2008); _F_ST=0.133, 12 microsatellite loci (Franchini et al., 2010)). More pronounced differentiation has also been recorded in a study involving metacentric and standard karyotype (all-acrocentric) mice (FST=0.29; eight microsatellite loci (Dallas et al., 1998)), as well as between standard karyotype mice, even in localities only 300 m distant from one another (FST=0.18; six microsatellite loci (Dallas et al., 1995)). The effects of individual microsatellite loci may be strong and studies using fewer loci may show greater differentiation. A study of Madeiran metacentric races using 39 microsatellite loci spread over six chromosomes (Förster, 2007) indicates that the degree of differentiation reported here is not unique to chromosomes 3 and 8. As three of the Italian samples in this study (I.Son, I.Mig and I.Ser; Table 1) correspond to sampling localities analysed by Panithanarak et al. (2004), we were able to examine if our results were affected by the particular loci chosen. Results for this analysis of Italian mice with our set of loci (FST=0.404; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.308–0.487) are clearly similar to those obtained by Panithanarak et al. (2004) and confirm that the degree of differentiation observed for the Madeiran metacentric mice is not because of some property of the particular microsatellites used in this study. This is further supported by the observed degree of differentiation between localities in Portugal (FST=0.287; 95% CI: 0.249–0.326), Scotland (FST=0.225; 95% CI: 0.158–0.301) and Spain (FST=0.149; 95% CI: 0.106–0.189), which is in the same range as previous studies (Dallas et al., 1995, 1998; Panithanarak et al., 2004; Franchini et al., 2008, 2010).

As there are several lines of evidence supporting a single origin of the Madeiran mice (Gündüz et al., 2001a; Britton-Davidian et al., 2005; Förster et al., 2009), it is not surprising that these races exhibit genetic similarities. The low degree of differentiation we found among Danish mice (_F_ST=0.082; 95% CI: 0.027–0.161), which share metacentric 3.8 by descent (Piálek et al. (2005), and references therein), appears consistent with such an interpretation. As the number of fixed karyotypic differences between races increases, the strength of the chromosomal barrier to gene flow is expected to increase (for example, Hauffe and Searle, 1998). The low degree of differentiation observed on Madeira for microsatellites (this study), allozymes (Britton-Davidian et al., 2007) and mt sequences (Förster et al., 2009) may thus reflect that karyotypic divergence on Madeira is recent and involved individuals from one source.

Differential gene flow between chromosome regions

Karyotypic differences are expected to act as barriers to gene flow (for example, King, 1993; Faria and Navarro, 2010). Some chromosomal speciation models propose that it is reduced recombination in those parts of the genome involved in chromosomal rearrangements that facilitates divergence (see Butlin (2005) and Faria and Navarro (2010)), whereas earlier models emphasise the reduction of reproductive fitness of karyotypic heterozygotes (that is, post-zygotic isolation, see King (1993) and Coyne and Orr (2004)). In both types of model it is the portion of the genome affected by chromosomal rearrangements that experiences a reduction in gene flow, promoting divergence. In the case of Rb fusions and whole-arm reciprocal translocations, the prediction is that loci in the centromeric region (referred to by us as ‘proximal loci’) should experience diminished gene flow, because the centromere is involved in these rearrangements.

There is evidence that the processes described by both types of chromosomal speciation model may apply in the house mouse. It has been demonstrated that house mice heterozygous for metacentrics have impaired reproductive fitness (for example, Wallace et al., 1992, 2002; Saïd et al., 1993; Hauffe and Searle, 1998), and that there are recombination effects in the vicinity of the centromere in such heterozygotes (for example, Davisson and Akeson, 1993; Bidau et al., 2001; Merico et al., 2003). Thus, one or both of these processes could affect gene flow in the centromeric region of the metacentric chromosomes investigated by us.

This potential chromosomal barrier to gene flow was investigated using microsatellite loci mapping to three chromosome regions (proximal, interstitial and distal) of mouse chromosomes 3 and 8. We found that the extent of genetic differentiation between karyotypic groups on Madeira varied according to the chromosome region examined. As predicted, higher genetic structure was observed near the centromere (proximal microsatellite loci) than in the other two chromosome regions examined (interstitial and distal microsatellite loci). This resulted from the association of alleles at proximal loci with either metacentric 3.8 or with metacentrics 3.14 and 8.11. A similar situation was reported by Panithanarak et al. (2004), who examined two chromosome regions (proximal and distal) in a system of house mouse metacentric races using mapped microsatellite loci.

It should be noted that the centromeric region is expected to show reduced recombination in general (for example, Carneiro et al., 2009; Geraldes et al., 2011; Nachman and Payseur, 2012), and that this has been documented for metacentric chromosomes in the house mouse (Dumas and Britton-Davidian, 2002). As the extent of genetic differentiation in the three chromosome regions was essentially the same among races sharing the same disposition of chromosomes (3.8 or 3.14 and 8.11), as well as within races, it seems unlikely that solely a ‘centromeric effect’ is responsible for the significant divergence observed at proximal loci between karyotypic groups (that is, 3.8 versus 3.14 and 8.11).

Not all proximal loci were characterised by alleles with a strong association with karyotype. Although this may reflect the short timeframe of the chromosomal radiation on Madeira (Britton-Davidian et al., 2007; Förster et al., 2009), the following factors may have contributed:

- Recombination: It has been suggested (Panithanarak et al., 2004) that association with a particular karyotype is not absolute, and that recombination breakpoints may occur between a proximal locus and the centromere, even when its genetic distance to the centromere is reported to be 0 cM. Not all of the proximal microsatellite loci investigated had zero recombination distance from the centromere (Supplementary Table S1).

- Random sampling of alleles: The random sampling of alleles during the fixation process in founding populations may involve common or uncommon alleles. Loci initially characterised by uncommon alleles may subsequently show a strong association with karyotype (like those in Supplementary Table S2), whereas loci initially characterised by common alleles may not.

Overall, our results are in agreement with chromosomal speciation models that predict higher divergence (or less introgression) in the vicinity of chromosomal rearrangements despite hybridisation and gene flow (for example, Butlin, 2005; Faria and Navarro, 2010). However, studies on more chromosomes are desirable. Thus, Panithanarak et al. (2004) compared chromosomes that did and did not differ between chromosomal races in Northern Italy and showed that centromeric regions of rearranged chromosomes showed less introgression than non-rearranged chromosomes. Such a study would be worthwhile on the Madeiran mice, to rule out the possibility that the reduced gene flow associated with proximal markers of metacentric 3.8 is a purely centromeric effect, rather than an impact of the chromosomal rearrangement (Carneiro et al., 2009; Geraldes et al., 2011; Nachman and Payseur, 2012). Such work is currently being carried out, using a suite of centromeric microsatellites that includes three loci per chromosome (total 60 loci: three for each of the 19 autosomes, plus three on the X chromosome).

Data archiving

Genotype data have been submitted to Dryad: doi:10.5061/dryad.jv2hd.

References

- Albuquerque L, Vieira A (1988). The Arquipelago of Madeira in the XV-century. Colecção Atlântica. Secretaria Regional do Turismo e Cultura/Centro de Estudos de História do Atlântico, Região Autónoma da Madeira.

- Avise JC (2000). Phylogeography: The History and Formation of Species. Harvard University Press: Boston, MA.

Google Scholar - Bidau CJ, Giménez MD, Palmer CL, Searle JB (2001). The effects of Robertsonian fusions on chiasma frequency and distribution in the house mouse (Mus musculus domesticus) from a hybrid zone in northern Scotland. Heredity 87: 305–313.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Britton-Davidian J, Catalan J, Ramalhinho G, Auffray J-C, Nunes AC, Gazave E et al. (2005). Chromosomal phylogeny of Robertsonian races of the house mouse on the island of Madeira: testing between alternative mutational processes. Genet Res 86: 171–183.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Britton-Davidian J, Catalan J, Lopez J, Ganem G, Nunes AC, Ramalhinho MG et al. (2007). Patterns of genic diversity and structure in a species undergoing rapid chromosomal radiation: an allozyme analysis of house mice from the Madeira archipelago. Heredity 99: 432–442.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Britton-Davidian J, Catalan J, Ramalhinho M, Ganem G, Auffray J-C, Capela R et al. (2000). Rapid chromosomal evolution in island mice. Nature 403: 158.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Busch JD, Waser PM, DeWoody JA (2007). Recent demographic bottlenecks are not accompanied by a genetic signature in banner-tailed kangaroo rats (Dipodomys spectabilis). Mol Ecol 16: 2450–2462.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Butlin RK (2005). Recombination and speciation. Mol Ecol 14: 2621–2635.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Carneiro M, Ferrand N, Nachman MW (2009). Recombination and speciation: loci near centromeres are more differentiated than loci near telomeres between subspecies of the European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus). Genetics 181: 593–606.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Coyne JA, Orr HA (2004) Speciation. Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA.

Google Scholar - Dallas JF, Bonhomme F, Boursot P, Britton-Davidian J, Bauchau V (1998). Population genetic structure in a Robertsonian race of house mice: evidence from microsatellite polymorphism. Heredity 80: 70–77.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Dallas JF, Dod B, Boursot P, Prager EM, Bonhomme F (1995). Population subdivision and gene flow in Danish house mice. Mol Ecol 4: 311–320.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Davisson MT, Akeson EC (1993). Recombination suppression by heterozygous Robertsonian chromosomes in the mouse. Genetics 133: 649–667.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Dumas D, Britton-Davidian J (2002). Chromosomal rearrangements and evolution of recombination: comparison of chiasma distribution patterns in standard and Robertsonian populations of the house mouse. Genetics 162: 1355–1366.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Faria R, Navarro A (2010). Chromosomal speciation revisited: rearranging theory with pieces of evidence. Trends Ecol Evol 25: 660–669.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Förster DW (2007). A molecular study on the evolution of island races of house mice on Madeira. DPhil thesis, University of York.

- Förster DW, Gündüz I, Nunes AC, Gabriel S, Ramalhinho MG, Mathias ML et al. (2009). Molecular insights into the colonization and chromosomal diversification of Madeiran house mice. Mol Ecol 18: 4477–4494.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Franchini P, Castiglia R, Capanna E (2008). Reproductive isolation between chromosomal races of the house mouse Mus musculus domesticus in a parapatric contact area revealed by an analysis of multiple unlinked loci. J Evol Biol 21: 502–513.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Franchini P, Colangelo P, Solano E, Capanna E, Verheyen E, Castiglia R (2010). Reduced gene flow at pericentromeric loci in a hybrid zone involving chromosomal races of the house mouse Mus musculus domesticus. Evolution 64: 2020–2032.

PubMed Google Scholar - Geraldes A, Basset P, Smith KL, Nachman MW (2011). Higher differentiation among subspecies of the house mouse (Mus musculus) in genomic regions with low recombination. Mol Ecol 20: 4722–4736.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Goodman SJ (1997). rst calc: a collection of computer programs for calculating unbiased estimates of genetic differentiation and gene flow from microsatellite data and determining their significance. Mol Ecol 6: 881–885.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Goudet J (2002). FSTAT 2.9.3.2. Lausanne: Switzerland. Available at: http://www2.unil.ch/popgen/softwares/fstat.htm.

- Goudet J (2005). Hierfstat, a package for R to compute and test hierarchical F-statistics. Mol Ecol Notes 5: 184–186.

Article Google Scholar - Gündüz I, Auffray J-C, Britton-Davidian J, Catalan J, Ganem G, Ramalhinho MG et al. (2001a). Molecular studies on the colonization of the Madeiran archipelago by house mice. Mol Ecol 10: 2023–2029.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Gündüz I, López-Fuster MJ, Ventura J, Searle JB (2001b). Clinal analysis of a chromosomal hybrid zone in the house mouse. Genet Res 77: 41–51.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Hauffe HC, Searle JB (1993). Extreme karyotypic variation in a Mus musculus domesticus hybrid zone: the tobacco mouse story revisited. Evolution 47: 1374–1395.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Hauffe HC, Searle JB (1998). Chromosomal heterozygosity and fertility in house mice (Mus musculus domesticus) from Northern Italy. Genetics 150: 1143–1154.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Jombart T (2008). adegenet: a R package for the multivariate analysis of genetic markers. Bioinformatics 24: 1403–1405.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Keller LF, Jeffery KJ, Arcese P, Beaumont MA, Hochachka WM, Smith JNM et al. (2001). Immigration and the ephemerality of a natural population bottleneck: evidence from molecular markers. Proc R Soc Lond Ser B 268: 1387–1394.

Article CAS Google Scholar - King M (1993) Species Evolution. The Role of Chromosome Change. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

Google Scholar - Merico V, Pigozzi MI, Esposito A, Merani MS, Garagna S (2003). Meiotic recombination and spermatogenic impairment in Mus musculus domesticus carrying multiple simple Robertsonian translocations. Cytogenet Genome Res 103: 321–329.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Nachman MW, Payseur BA (2012). Recombination rate variation and speciation: theoretical predictions and empirical results from rabbits and mice. Philos Trans R Soc Ser B 367: 409–421.

Article Google Scholar - Nachman MW, Searle JB (1995). Why is the mouse karyotype so variable? Trends Ecol Evol 10: 397–402.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Navarro YN, Britton-Davidian J (1989). Genetic structure of insular Mediterranean populations of the house mouse. Biol J Linn Soc 36: 377–390.

Article Google Scholar - Nei M (1978). Estimation of average heterozygosity and genetic distance from a small number of individuals. Genetics 89: 583–590.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Palmer CL (1997). A chromosomal hybrid zone of the house mouse (Mus musculus domesticus) in northern Scotland. DPhil thesis, University of York.

- Panithanarak T, Hauffe HC, Dallas JF, Glover A, Ward RG, Searle JB (2004). Linkage-dependent gene flow in a house mouse chromosomal hybrid zone. Evolution 58: 184–192.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Piálek J, Hauffe HC, Searle JB (2005). Chromosomal variation in the house mouse. Biol J Linn Soc 84: 535–563.

Article Google Scholar - Raymond M, Rousset F (1995). GENEPOP. Version 3.1d: population genetics software for exact tests and ecumenism. J Hered 86: 248–249.

Article Google Scholar - Riginos C, Nachman MW (1999). The origin of a Robertsonian chromosomal translocation in house mice inferred from linked microsatellite markers. Mol Biol Evol 16: 1763–1773.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Saïd K, Saad A, Auffray J-C, Britton-Davidian J (1993). Fertility estimates in the Tunisian all-acrocentric and Robertsonian populations of the house mouse and their chromosomal hybrids. Heredity 71: 532–538.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Schneider S, Kueffer JM, Roessli D, Excoffier L (1997). Arlequin, version 1.1: a software for population genetic data analysis. Genetics and Biometry Laboratory, University of Geneva.

- Searle JB (1991). A hybrid zone comprising staggered chromosomal clines in the house mouse (Mus musculus domesticus). Proc R Soc Lond Ser B 246: 47–52.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Searle JB (1993). Chromosomal hybrid zones in eutherian mammals. In: Harrison RG (ed.). Hybrid Zones and the Evolutionary Process. Oxford University Press: New York, pp 507–532.

Google Scholar - Searle JB, Navarro YN, Ganem G (1993). Further studies of a staggered hybrid zone in Mus musculus domesticus (the house mouse). Heredity 71: 523–531.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Slatkin M (1995). A measure of population subdivision based on microsatellite allele frequencies. Genetics 139: 457–462.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Smadja C, Catalan J, Ganem G (2004). Strong premating divergence in a unimodal hybrid zone between two subspecies of the house mouse. J Evol Biol 17: 165–176.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Van Oosterhout C, Hutchinson WF, Wills DPM, Shipley P (2004). Micro-checker: software for identifying and correcting genotyping errors in microsatellite data. Mol Ecol Notes 4: 535–538.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Wallace BMN, Searle JB, Everett CA (1992). Studies on meiosis and gametogenesis in wild house mice (Mus musculus domesticus): Male ‘simple’ heterozygotes and homozygotes from a chromosomal hybrid zone. Cytogenet Cell Genet 61: 211–220.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Wallace BMN, Searle JB, Everett CA (2002). The effect of multiple simple Robertsonian heterozygosity on chromosome pairing and fertility of wild-stock house mice (Mus musculus domesticus). Cytogenet Genome Res 96: 276–286.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Weir BS, Cockerham CC (1984). Estimating F-statistics for the analysis of population structure. Evolution 38: 1358–1370.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar - White TA, Bordewich M, Searle JB (2010). A network approach to study karyotypic evolution: the chromosomal races of the common shrew (Sorex araneus) and house mouse (Mus musculus) as model systems. Syst Biol 59: 262–276.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Yeh FC, Yang RC, Boyle TBJ, Ye ZH, Mao JX (1997) popgene, the User-Friendly Shareware for Population Genetic Analysis. Molecular Biology and Biotechnology Centre, University of Alberta: Canada.

Google Scholar - Zenger KR, Richardson BJ, Vachot-Griffin AM (2003). A rapid population expansion retains genetic diversity within European rabbits in Australia. Mol Ecol 12: 789–794.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to C Bidau, S Gabriel, G Ganem, M Giménez, İ Gündüz, H Hauffe, M López-Fuster, A Nunes, C Palmer, T Panithanarak, C Smadja and J Ventura for contributing house mouse samples to this study. This project benefited from the financial support of the Fundacao para a Ciencia e a Tecnologia (PRAXIS/PCNA/C/BIA/135/96) and SAPIENS (POCTI/BSE/47019/02), the University of York (UK) and the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- Research Group Evolutionary Genetics, Leibniz-Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research, Berlin, Germany

D W Förster - Department of Biology, University of York, Wentworth Way, York, UK

D W Förster & J B Searle - Departmento de Biologia Animal, Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa, Portugal

M L Mathias - Université Montpellier II, CNRS Institu des Sciences de l’Evolution, Montpellier, France

J Britton-Davidian - Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA

J B Searle

Authors

- D W Förster

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - M L Mathias

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - J Britton-Davidian

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - J B Searle

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence toD W Förster.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on Heredity website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Förster, D., Mathias, M., Britton-Davidian, J. et al. Origin of the chromosomal radiation of Madeiran house mice: a microsatellite analysis of metacentric chromosomes.Heredity 110, 380–388 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/hdy.2012.107

- Received: 26 June 2012

- Revised: 25 October 2012

- Accepted: 05 November 2012

- Published: 12 December 2012

- Issue Date: April 2013

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/hdy.2012.107