The origins of the enigmatic Falkland Islands wolf (original) (raw)

Introduction

During the Pleistocene (ca. 2.6 Ma–12 ka) South America supported a diverse canid fauna including large hyper-carnivorous species (that is, Theriodictis spp., Protocyon spp.,1,2,3,4), as well as smaller species such as the Falkland Islands wolf (FIW) and a related fox found on the mainland, Dusicyon avus (Fig. 1). Most of these species became extinct during the Pleistocene, with D. avus extinct by the late Holocene, and the FIW extinct in the nineteenth century following human hunting4,5,6,7. The origin of the FIW has been a natural history mystery for over 320 years8. Following his encounter with the species in 1,834, Darwin commented ‘As far as I am aware, there is no other instance in any part of the world, of so small a mass of broken land, distant from a continent, possessing so large a quadruped peculiar to itself’9. The mystery is deepened by the absence of any other terrestrial mammals on the islands. While the flora and fauna of the islands show overwhelming Patagonian biogeographical affinities10, the physical isolation of the islands (~460 km from the South American mainland) has resulted in a number of theories to explain the origin of the FIW. These include semi-domestication and transport of a continental ancestor by humans sometime after their arrival in southern South America ~13–14.5 ka (11,12) or natural dispersal via rafting on ice or over a land bridge during Pleistocene glacial sea level minima1,13,14,15. Recently, ancient DNA analysis revealed the FIW to be a unique South American endemic only distantly related to the living South American maned wolf (Chrysocyon brachyurus)7. However, uncertainty about the canid phylogenetic tree and ambiguous and/or imprecise fossil calibrations limited the power of the analysis to an approximate divergence date for the FIW and maned wolf of 6.7 Ma (4.2–8.9 Ma). The molecular evolutionary rate estimated in this analysis was also used to calculate the time to the most recent common ancestor (TMRCA) of five museum specimens of the FIW as 330 ka (95% highest posterior density (HPD) 70–640 ka), and this date was used as a proxy for the colonization age of the Falkland Islands. However, even if this date estimate was approximately accurate, the colonization event could have been considerably older or younger than this depending on the demographic history, any subsequent lineage extinctions16, and the relationship between the FIW and unsampled mainland relatives17. Furthermore, the use of external fossil calibrations to date recent events is known to be problematic due to the temporal dependency of molecular rates18,19. Either way, while the estimated 330 ka date and wide error margins (70–640 ka) clearly predates human arrival, it provided little evidence as to how the FIW might have colonized the islands.

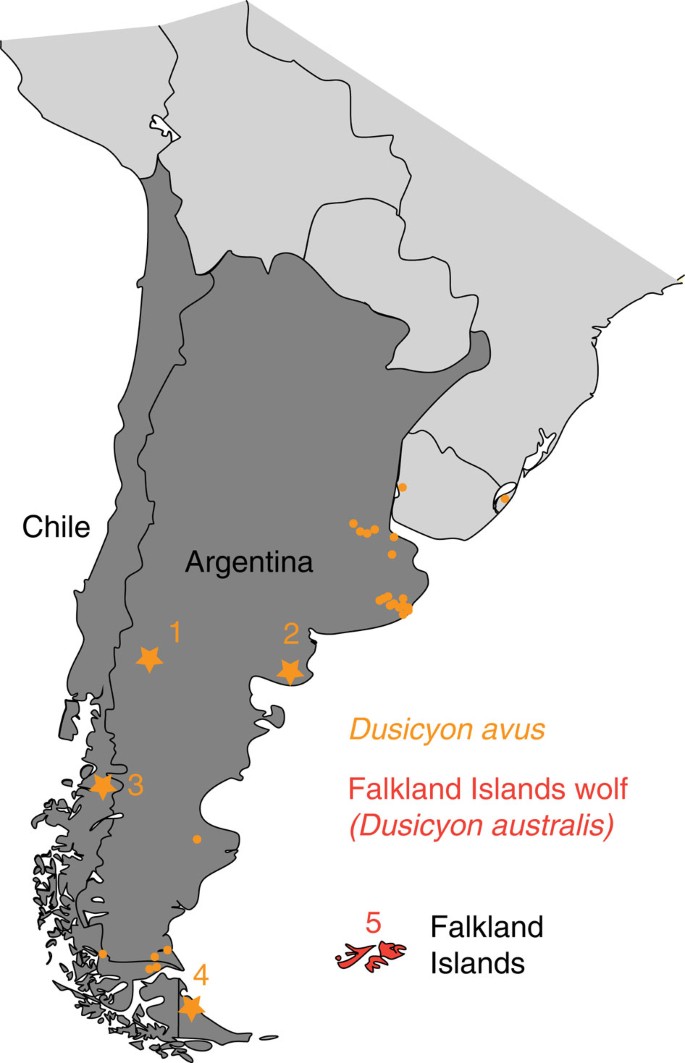

Figure 1: Specimen distribution.

Distribution map of the specimens analysed. The geographical locations of Dusicyon avus specimens known from late Pleistocene to late Holocene sites are shown as orange dots, with the localities of sampled specimens as orange stars. The latter are (1): La Marcelina 1, Rio Negro, Argentina; (2): Loma de los Muertos, Rio Negro, Argentina; (3): Baño Nuevo-1 Cave, Chile; (4): Perro 1 site, Tierra del Fuego, Argentina. Five specimens of Falkland Islands Wolf (FIW) (red) from museum collections were previously analysed, (5): Falkland or Malvinas Islands.

Critically, the genetic analysis of the FIW did not include the putative mainland close relative D. avus, whose phylogenetic relationship has not been tested. D. avus had a clear archaeological association and temporal overlap with modern humans until extinction ~3 ka (6), raising the possibility of human transport to the islands. To investigate this issue and characterize the genetic diversity and phylogenetic relationships of this extinct canid, we extracted and sequenced 1,069 bp of ancient mitochondrial DNA from six specimens of D. avus collected across Argentina and Chile, ranging in age from 7,800–3,000 yr BP. We also compared the genetic signals with morphological data from nearly all the extinct and living species of South American canids, a wide sample of other Caninae, and fossils of the extinct subfamilies Hesperocyonidae and Borophaginae3.

Results

Sequences

A combined 1,069 bp of mtDNA COII and cytochrome b sequence was obtained from six out of seven D. avus specimens (Supplementary Table S1). No samples produced PCR products for the four nuclear gene targets. All PCR and sequencing results were replicated at least once and produced identical results, suggesting a minimal contribution from damage-related artefacts.

Topology

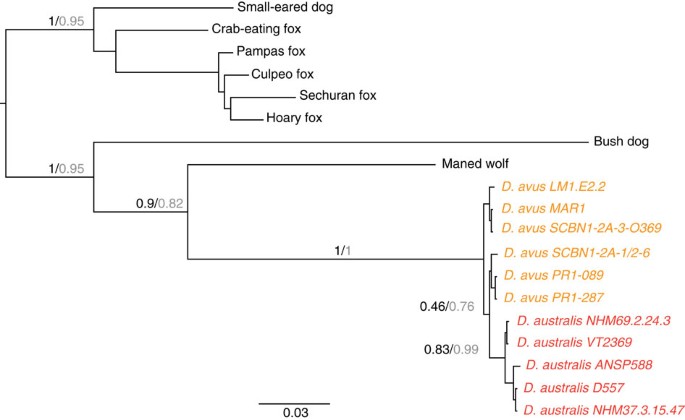

Both ML and Bayesian molecular analyses confirm that D. avus is the closest relative of the FIW with strong statistical support (Fig. 2), and only six fixed transition differences separate the FIW and D. avus (Supplementary Fig. S1, uncorrected sequence divergence=0.56%). Ten additional variable sites defined three haplotypes within the FIW (from five individuals) and four haplotypes in D. avus (from six individuals) (Supplementary Fig. S1). Strong support is also recovered for the monophyly of the Dusicyon clade, its sister taxon relationship to the maned wolf, with the bush dog as the outgroup. While D. avus was weakly recovered as paraphyletic in the topological analysis, D. avus and the FIW were strongly supported as reciprocally monophyletic in analyses using a molecular clock and either external or internal calibrations (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. S2). The combined morphological and molecular analysis recovered one most parsimonious tree of 3782.017 steps (Supplementary Figs S3 and S4), similar to the one previously reported by Prevosti3, but D. avus and FIW are a monophyletic group sister of C. brachyurus (Supplementary Figs S2, S3 and S4).

Figure 2: Phylogenetic position of D. avus and FIW.

Phylogenetic tree showing the topological placement of D. avus, FIW and South American canids, based on the analysis of 1,069bp of mitochondrial cyt b and COII genes. The same topology was recovered using Bayesian (MrBayes, black support values) and maximum likelihood analyses (PhyML, grey support values). The FIW forms a monophyletic group separate from the mainland D. avus, which is weakly supported as being paraphyletic, with the maned wolf as the closest living relative to the extinct Dusicyon clade.

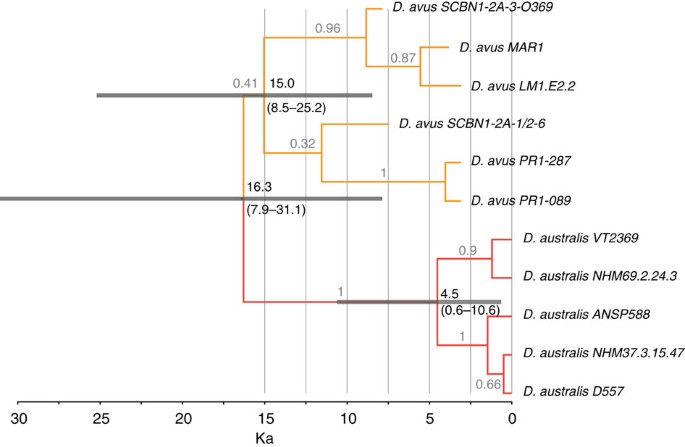

Figure 3: Dated phylogeny of D. avus and FIW (D. australis).

Unconstrained phylogeny of D. avus and FIW using a molecular clock, with the radiocarbon-dated ancient samples as temporally proximate calibration points. The timescale is given in thousand years (ka). The two Dusicyon species are strongly supported as reciprocally monophyletic clades in this analysis, and when external canid fossil calibration points are used (Supplementary Fig S2). The two species are estimated to have diverged during the last glacial phase (7.9–31.1 ka), with the upper bound overlapping with the first human presence in Patagonia11,12. The topology is a maximum clade credibility tree from BEAST with 95% HPD of the calculated node ages represented as grey bars. The use of ancient samples to provide tip-date calibrations led to considerably younger TMRCA estimates for the Dusicyon clades than previous estimates (~330 ka for FIW7), which relied on deep canid fossil calibrations of imprecise phylogenetic and temporal position.

Dating

Date randomization tests confirmed that sufficient signal existed in the dated concatenated sequences from the six D. avus individuals to provide appropriate internal temporal calibration information at the tip of the tree to facilitate molecular dating19 (Supplementary Fig. S5). Bayesian analyses estimate that the FIW diverged from D. avus recently, around 16.3 ka (95% HPD 7.9–31.1 ka). The TMRCA for the D. avus, and for the FIW, specimens were estimated at 15.0 ka (95% HPD 8.5–25.2 ka) and 4.5 ka (95% HPD 0.6–10.6 ka), respectively (Fig. 3). In contrast, analyses using several deep, and poorly constrained canid fossil calibration points originally used in Slater et al.7 produced much older age estimates, close to those previously reported (Supplementary Figs S2, Supplementary Table S2 and Supplementary Methods).

Interestingly, while the low intra-specific mtDNA diversity within the FIW (_π_=0.0021) was consistent with that of other insular species, the diversity within D. avus was similar (_π_=0.0026), despite the much larger geographic and ecological range of the samples. Furthermore, no phylogeographic patterns were evident within the D. avus sequences (Supplementary Fig. S1) despite the wide sampling area.

Discussion

The estimated latest Pleistocene date of 16 ka (8–31 ka) for the origin of the FIW is consistent with events associated with the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) ca. 26–19 ka (20), and is considerably younger than the previously estimated date of 330 ka (7). The accuracy of molecular divergence date estimates is directly related to the quality of calibration data, and their proximity to the date of interest. In this regard, the use of deep fossil calibration points has been shown to be inappropriate for intra-specific and recent inter-specific divergences18,19, such as those within Dusicyon. The radiocarbon dates associated with the ancient sequences of D. avus provide much closer calibration points to the late Pleistocene events under consideration than the early canid fossils used in Slater et al.7, and importantly do not suffer from the same uncertainty over taxonomic identification and phylogenetic position. Although additional internal calibration points would no doubt help refine the inferred dates, the randomization analyses confirm that the heterochronous Holocene D. avus sequences contain sufficient temporal information to calibrate the recent evolutionary history of Dusicyon (Supplementary Fig. S5 and Supplementary Methods).

The data do not support a recent origin for the FIW via human transport from a source population of D. avus on the South American mainland due to the estimated 16 ka divergence date and the reciprocal monophyly of the two species in calibrated analyses. Although the confidence interval (8–31 ka) for the divergence event overlaps with the earliest human presence in Patagonia (13–14.5 ka, (11,12), and human agency cannot therefore be ruled out, the genetic isolation of the FIW (presumably via transfer to the Falkland Islands) would have had to occur only once during the earliest phases of human occupation in Patagonia (that is, >8 ka), which seems improbable. Furthermore, the estimated 16 ka divergence date is unlikely to be an overestimate due to the existence of undetected and phylogenetically closer source populations of D. avus, because the geographically widespread D. avus samples have low nucleotide diversity and lack phylogeographic structure. Indeed, the young TMRCA of ~15 ka for D. avus and the lack of geographic structure and low genetic diversity suggest that the range of this species has recently expanded across the Patagonian and Pampean regions, potentially from a LGM refugium.

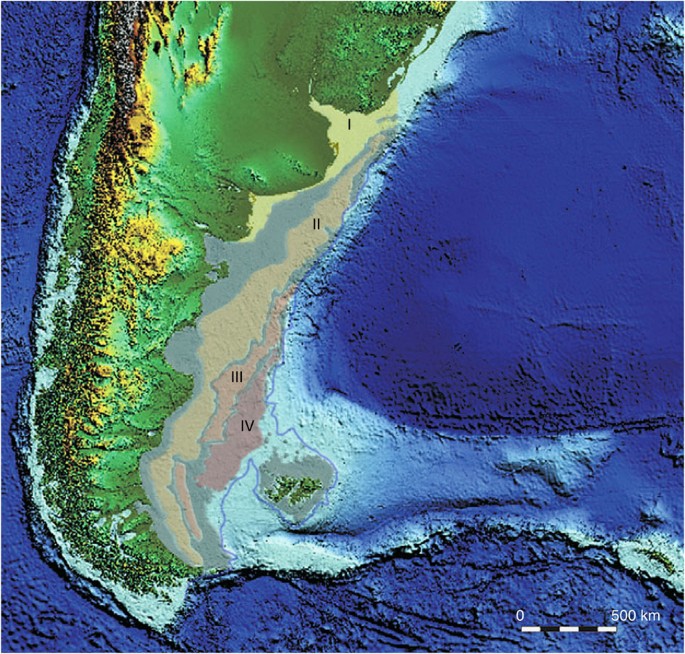

A pre-human dispersal of the FIW requires either a land bridge during low sea level stands or a marine crossing, but the absence of other terrestrial mammals on the Falkland Islands strongly argues against a continuous land bridge connection to the mainland. The particularly shallow slope of the Argentine continental shelf means that lowered sea levels dramatically reduce the size of the marine strait separating the Falkland Islands, which currently has a minimum depth of ca. 160 m (21). During the height of the LGM (26–19 ka) global sea levels were around 130 m lower, which exposed an enormous coastal plain off the Argentine coast, while the Falkland islands landmass was about four times larger than the present21,22,23. Four pronounced submarine terraces detected on the coastal shelf (Fig. 4) are thought to record low sea-stands at various points during the LGM24. The two shallowest have been dated ca. 11 ka (−35/−40 m isobath) and 15 ka (−80/−90 m) (ref. 21), with the timing of the latter being consistent with Meltwater Pulse 1A, associated with the onset of the retreat of the West Antarctic Ice Shelf20. Two deeper terraces situated at the −110/−120 m and the −130/150 m isobaths remain undated, but are thought to represent low sea-stands during earlier phases of the LGM. The deepest terrace (−130/150 m) is presumably the oldest and corresponds to the lowest isostatic conditions, as it has not been degraded through subsequent near-shore activity. The depth of the terrace matches the estimated minimal sea level during the LGM (ca. −130 m), but could also relate to earlier glacial events24. However, the difference between the −110/120 m and −130/150 m terraces is consistent with a rapid 10 m rise from LGM lowstand sea levels associated with the 19–20 ka Meltwater Pulse caused by the widespread retreat of northern hemisphere ice sheets20. Either way, the molecular date estimate for the divergence of the FIW of 16 ka (range 8–31 ka) is consistent with colonization during the LGM, when the submarine terraces indicate the marine strait was both narrow and shallow.

Figure 4: Submarine terraces between the mainland and the Falkland Islands.

The four submarine terraces (levels I–IV) along the continental shelf (light blue) between the South American continent and the Falkland Islands: level I=−25/−30 m isobath; level II=−85/−95 m; level III=−110/−120 m and level IV=−130/−150 m (21). Terrace I has been dated ca. 11 ka, and Terrace II ca. 15 ka (21), with the latter being consistent with the global Meltwater Pulse 1A, associated with the West Antarctic Ice Sheet20. Terraces III and IV are undated but are thought to reflect earlier phases of the LGM, with the depth differential matching the rapid 10 m rise from the LGM lowstand caused by the global Meltwater Pulse at 19–20 ka (ref. 20). The projected sea level position at −140 m is drawn in grey, representing the peak low sea-stand during the LGM (data from Ponce et al.21). At this point the Falkland Islands would have been separated from the mainland by a shallow marine strait estimated to be as little as 20 km wide and only 10–30 m deep. It is suggested that this is likely to periodically have been covered by ice, or facilitated ice rafting, during peak glacial conditions.

A low sea-stand between the −130 and −150 m isobaths would drastically reduce the size of the marine strait separating the Falkland Islands, potentially to just 20–30 km (Fig. 4), with an estimated minimum depth of 10–30 m. It is possible that the ancestors of the FIW were transported across this strait by ice rafting during this period, as has been suggested, but it seems more likely that such a shallow marine strait would be periodically frozen over by continuous sea ice and/or glacial outflow to produce an ephemeral connection that could act as a filter, rather than a corridor. Individuals or packs of the ancestor of FIW pursuing marine food sources (for example, seals, penguins, seabirds) on the margins of the ice would have an increased likelihood of colonization compared with other South American endemic mammals that would not cross large ice-fields due to either habitat or behaviour. An interesting question is why previous glacial maxima did not lead to other mammal colonizations of the Falkland Islands, as the marine strait is thought to have been shallower during earlier phases of the Pleistocene before the erosion of soft sediments21. It is possible that if there were such previous residents they may have gone extinct without leaving a fossil record.

The greatly improved resolution provided by genetic data from the closest mainland relative allows us to conclude that the ancestor of the FIW likely colonized the Falkland Islands via mobile or static ice, crossing a narrow strait during the Last Glacial Maximum in Patagonia.

Methods

Samples

Seven D. avus teeth representing different individuals (Supplementary Table S3) were obtained from four sites in Patagonia: La Marcelina, Rio Negro (one tooth); Loma de los Muertos, Rio Negro (one tooth) and Perro 1 site; Tierra del Fuego (two teeth) in Argentina; and Baño Nuevo-1 Cave (three teeth) in Chile. One premolar from Baño Nuevo-1 cave has been dated to 7,860±78 cal. yr BP (UCIAMS-19490, Supplementary Table S3), while specimens from Perro 1, Loma de los Muertos and La Marcelina 1 were dated to 3,085±133, 3,072±151, and 3,814±117 cal. yr BP (AA75297, AA83516, AA90951; (6,23) Supplementary Table S3), respectively. A second specimen from Baño Nuevo-1 cave was undated but assigned a prior mean age of 7,500 cal. yr BP (6,000–9,000 cal. yr BP 95% range, Supplementary Table S3) based on an archaeological association with dated remains from the same site. Teeth were obtained from recently described specimens that have diagnostic morphological features of D. avus for example, large lower carnassial, a lower fourth premolar with a second distal accessory cusp and a narrow distal cingulum4,6. The FIW exhibits differences in dental morphology from D. avus including a more reduced protocone in the P4, smaller metaconid in the m1, and taller and more acute principal cusps of the premolars6. These characters are generally associated with a more carnivorous diet25,26 and potentially reflect the limited dietary breadth of the FIW27,28.

Molecular analyses

To avoid the potential for contamination of D. avus samples with contemporary canid DNA or previously amplified FIW PCR products7, all pre-PCR work was performed in a dedicated ancient DNA laboratory geographically separated (by ~1.5 km) from post-PCR and other molecular biology laboratories at the Australian Centre for Ancient DNA, University of Adelaide, South Australia. No contemporary canid DNA had ever been present in the pre-PCR laboratory. The ancient DNA facility includes high-efficiency particulate air-filtered positive air pressure with one-way air flow, overhead ultraviolet (UV) lights, individual work-rooms, the use of dead-air glove boxes with internal UV lights for DNA extractions and PCR set-up, regular decontamination of all work areas and equipment with sodium hypochlorite, personal protective equipment including full body suit, face mask, face shield, boots and triple-gloving and strict one-way movement of personnel (shower>freshly laundered clothes>ancient DNA laboratory>post-PCR laboratory).

A negative extraction control was included with every set of DNA extractions and all extractions were carried out in small sets and generally included samples from phylogenetically divergent non-canid species. DNA was extracted using a modified silica-based method29 designed to maximize recovery of PCR-amplifiable DNA from ancient bone and tooth specimens while minimizing coextraction of PCR inhibitors.

Short fragments of mitochondrial (166–240 bp) and nuclear (108–173 bp) DNA were targeted by PCR, to assemble a 652-bp fragment of the mtDNA COII gene, a 394-bp fragment of the mtDNA cytochrome b gene, and four nuclear loci (CH21, VANGL, VTN(SNP), VTN(indel)7, (Supplementary Table S4). One microlitre of extract, in parallel with extraction controls and negative PCR controls, was amplified in a 25-μl PCR containing: 1 × Platinum Taq High Fidelity Buffer (Invitrogen), 2 mM MgSO4, 0.4 mM each primer, 0.25 mM each dNTP, 0.5 U Platinum Taq DNA Polymerase High Fidelity, 1 mg ml−1 RSA (Sigma-Aldrich) and sterile H20. PCRs were run on a Palmcycler (Corbett Research) under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 94 °C for 1 min; 50 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 15 s; primer annealing at 55 °C for 15 s; elongation at 68 °C for 30 s; a final elongation step at 68 °C for 10 min. PCR products were visualized under UV light on a 3.5% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide. Successful amplifications were purified using Ampure (Agencourt) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and sequenced directly using Big Dye chemistry and an ABI 3130XL Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems). All positive PCR and sequencing results were repeated to ensure reproducibility.

Sequence alignment

COII and cytochrome b sequences were generated from six D. avus specimens and aligned with the available sequences from five FIW specimens, and the eight South American canids used by Slater et al.7 (maned wolf—Chrysocyon brachyurus, bush dog—Speothos venaticus, crab-eating fox—Cerdocyon thous, small-eared dog—Atelocynus microtis, sechuran fox—Lycalopex sechurae, culpeo fox—Lycalopex culpaeus, pampas fox—Lycalopex gymnocercus, hoary fox—Lycalopex vetulus). The South American canids have previously been shown to be monophyletic7.

Phylogenetic analyses

To study the phylogenetic placement of D. avus, we performed both Bayesian (MrBayes30) and maximum likelihood (PhyML31) analyses on the entire data set (D. avus, FIW and eight South American canids, as described above). The best substitution model was selected through comparison of Bayesian information criteria scores using ModelGenerator v0.85 (ref. 32).

In addition, a haplotype network showing genealogical relationships between all D. avus and FIW sequences was generated using statistical parsimony implemented in TCS v1.17 (33). Nucleotide diversity within D. avus and FIW was calculated using DnaSP v5.10.01 (34).

We also performed a total evidence analysis combining the new mitochondrial sequences with previously reported morphological, behavioural and genetic data for South American canids35. The individual mitochondrial sequences of D. avus and FIW were each combined into a single consensus sequence using the programme Bioedit 7.0.5.3 (36), and the variable sites were scored as polymorphic using the IUPAC code. The mitochondrial sequences were added to a previously published ‘total evidence’ matrix3 containing dental and skeletal characters, behavioural and life history traits37, and 22 nuclear and 3 mitochondrial genes from a wide sampling of living canids and several fossil representatives (for whom only dental and skeletal data was available). Sequence gaps were coded as a fifth state. The combined matrix was analysed under Maximum parsimony with the software TNT version 1.1 (ref. 38) under equal weighting (SI). Trees were obtained from heuristic searches with 1,000 random-addition sequence replicates and tree bisection-reconnection (TBR) branch swapping, supplemented by a TBR round on the resulting shortest-length trees. Additional searches were conducted using the sectorial-searches, tree-drifting and tree-fusing algorithms39, but they found the same trees. Branch support was quantified with symmetrical-resampling jackknifing frequencies and frequency differences (5,000 resamples; ref. 40). The trees were rooted with the basal canid Hesperocyon gregarius. Branches were collapsed following the rule number 1, where any branch with at least one reconstruction with 0 changes is collapsed (minimal branch length=0; see ref. 41).

Calibration using fossils versus internal radiocarbon dates

To examine the problems caused by the temporal dependency of molecular dates, we performed molecular dating analyses using either internal (radiocarbon), or external (fossil), dates. The advantages of using internal calibrations to study recent evolutionary events are well established18,19, and given a divergence event thought to be late Pleistocene (natural dispersal) or Holocene (human dispersal), the internal radiocarbon dates for D. avus appear far more appropriate than external fossil dates of 4–32 Ma (with largely unknown error margins) and uncertain taxonomic/phylogenetic position.

Radiocarbon ages were converted to calibrated ages using the CALIB 6.0.1 software available at http://intcal.qub.ac.uk/calib/42,43, using the Southern Hemisphere SHCal04 curve44 and two sigma ranges. A Bayesian phylogenetic analysis was performed using the FIW and D. avus sequences to estimate the TMRCA of each species, and their immediate ancestor, using the D. avus radiocarbon dates as the sole calibration points. The best substitution model was selected through comparison of Bayesian information criteria scores using ModelGenerator v0.85 (ref. 32). Phylogenetic analyses were performed with BEAST 1.6.2 (ref. 45) using a strict molecular clock (analyses using an uncorrelated lognormal relaxed clock could not reject the strict clock assumption), and the Bayesian skyride demographic model46 to account for demographic changes through time. The results were processed with Tracer v1.5 ([47](/articles/ncomms2570#ref-CR47 "Rambaut, A. & Drummond, A. J. Tracer v1.4, Available from beast.bio.ed.ac.uk/Tracer

(2007) .")) to check that each sampled parameter had an effective sample size over 200.To test whether the signal from the radiocarbon dates associated with the ancient sequences is sufficient to calibrate the Dusicyon phylogeny, a ‘date randomization test’48 was conducted. This test consists of randomizing all dates associated with the sequences (including modern ones), and then replicating the phylogenetic analysis. Ten replicates of the BEAST phylogeny described in the main text were performed using different iterations of randomized dates.

To examine the impact of using external canid fossils as calibration points, we repeated the initial molecular analysis of the FIW by Slater et al.7, but with the addition of six new sequences from D. avus (Supplementary Fig. S2).

Additional information

How to cite this article: Austin, J.J. et al. The origins of the enigmatic Falkland Islands wolf. Nat. Commun. 4:1552 doi: 10.1038/ncomms2570 (2013).

References

- Berta, A. Origin, diversification, and zoogeography of the South American Canidae. Fieldiana: Zoology 39, 455–471 (1987) .

Google Scholar - Kraglievich, L. Contribution to the knowledge of the extinct canids of South America. Anales de la Sociedad Científica Argentina 106, 25–66 (1928) .

Google Scholar - Prevosti, F. J. Phylogeny of the large extinct South American Canids (Mammalia, Carnivora, Canidae) using a ‘total evidence’ approach. Cladistics 26, 456–481 (2010) .

Article Google Scholar - Prevosti, F. J., Ubilla, M. & Perea, D. Large extinct canids from the Pleistocene of Uruguay: systematic, biogeographic and palaeoecological remarks. Historical Biol. 21, 79–89 (2009) .

Article Google Scholar - Cione, A. L., Tonni, E. P. & Soibelzon, L. H. In American Megafaunal Extinctions at the End of the Pleistocene ed. Haynes G. 125–144 Springer (2009) .

- Prevosti, F. J., Santiago, F., Prates, L. & Salemme, M. Constraining the time of extinction of the South American fox Dusicyon avus (Carnivora, Canidae) during the late Holocene. Quatern. Int. 245, 209–217 (2011) .

Article Google Scholar - Slater, G. J. et al. Evolutionary history of the Falklands wolf. Curr. Biol. 19, R937–R938 (2009) .

Article CAS Google Scholar - Simson, R. in Sloane MS 86, (672): British Library, London (1689) .

- Darwin, C. Narrative of the surveying voyages of His Majesty’s Ships Adventure and Beagle between the years 1826 and 1836, describing their examination of the southern shores of South America, and the Beagle’s circumnavigation of the globe Vol. III (1839) .

- McDowall, R. M. Falkland Islands biogeography: converging trajectories in the South Atlantic Ocean. J. Biogeography 32, 49–62 (2005) .

Article Google Scholar - Dillehay, T. D. & Collins, M. B. Early cultural evidence from Monte-Verde in Chile. Nature 332, 150–152 (1988) .

Article ADS Google Scholar - Steele, J. & Politis, G. AMS C-14 dating of early human occupation of southern South America. J. Archaeol. Sci. 36, 419–429 (2009) .

Article Google Scholar - Clutton-Brock, J., Corbet, G. G. & Hills, M. A review of the family Canidae, with a classification by numerical methods. Bull. Br. Mus. (Nat. His.) Zool. 29, 119–199 (1976) .

Google Scholar - FitzRoy, R. Narrative of the surveying voyages of His Majesty’s Ships Adventure and Beagle between the years 1826 and 1836, describing their examination of the southern shores of South America, and the Beagle’s circumnavigation of the globe. Proceedings of the second expedition (under the command of Captain Robert FitzRoy R. N.) 1831–1836 Henry Colburn (1839) .

- Wang, X., Tedford, R. H. & Anton, M. Dogs: their Fossil Relatives and Evolutionary History Columbia Univ. Press (2008) .

- Poux, C. et al. Asynchronous colonization of Madagascar by the four endemic clades of primates, tenrecs, carnivores, and rodents as inferred from nuclear genes. Syst. Biol. 54, 719–730 (2005) .

Article Google Scholar - Emerson, B. Evolution on oceanic islands: molecular phylogenetic approaches to understanding pattern and process. Mol. Ecol. 11, 951–966 (2002) .

Article CAS Google Scholar - Ho, S. Y. W. et al. Time-dependent rates of molecular evolution. Mol. Ecol. 20, 3087–3101 (2011) .

Article Google Scholar - Ho, S. Y. W., Saarma, U., Barnett, R., Haile, J. & Shapiro, B. The effect of inappropriate calibration: three case studies in molecular ecology. Plos One 3, e1615 (2008) .

Article ADS Google Scholar - Clark, P. U. et al. The last glacial maximum. Science 325, 710–714 (2009) .

Article CAS ADS Google Scholar - Ponce, J. F., Rabassa, J., Coronato, A. & Borromei, A. M. Palaeogeographical evolution of the Atlantic coast of Pampa and Patagonia from the last glacial maximum to the Middle Holocene. Biol. J. Linnean Soc. 103, 363–379 (2011) .

Article Google Scholar - Rabassa, J. Late Cenozoic of Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego. 151–204 (Elsevier, 2008), .

- Rostami, K., Peltier, W. R. & Mangini, A. Quaternary marine terraces, sea-level changes and uplift history of Patagonia, Argentina: comparisons with predictions of the ICE-4G (VM2) model of the global process of glacial isostatic adjustment. Quat. Sci. Rev. 19, 1495–1525 (2000) .

Article ADS Google Scholar - Parker, G., Violante, R. A. & Paterlini, C. M. Report of the XIII Argentine Geological Congress and the III Hydrocarbon Exploration Congress 1–16 Associación Geológica Argentina-Instituto Argentino del Petróleo (1996) .

- Berta, A. Quaternary Evolution and Biogeography of the Large South American Canidae (Mammalia: Carnivora) University of California Publications in Geological Sciences (1989) .

- Van Valkenburgh, B. Iterative evolution of hypercarnivory in canids (Mammalia: Carnivora): evolutionary interactions among sympatric predators. Paleobiology 17, 340–362 (1991) .

Article Google Scholar - Mivart, G. Dogs, Jackals, Wolves, and Foxes: a Monograph of the Canidae Taylor and Francis (1890) .

- Waterhouse, G. R. Mammalia Part 2 of the Zoology of the Voyage of HMS Beagle. Edited and superintended by Charles Darwin Smith Elder and Co. (1939) .

- Rohland, N. & Hofreiter, M. Ancient DNA extraction from bones and teeth. Nat. Protocols 2, 1756–1762 (2007) .

Article CAS Google Scholar - Ronquist, F. & Huelsenbeck, J. P. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 19, 1572–1574 (2003) .

Article CAS Google Scholar - Guindon, S. & Gascuel, O. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst. Biol. 52, 696–704 (2003) .

Article Google Scholar - Keane, T. M., Creevey, C. J., Pentony, M. M., Naughton, T. J. & McLnerney, J. O. Assessment of methods for amino acid matrix selection and their use on empirical data shows that ad hoc assumptions for choice of matrix are not justified. BMC Evol. Biol. 6, 29 (2006) .

Article Google Scholar - Clement, M., Posada, D. & Crandall, K. A. TCS: a computer program to estimate gene genealogies. Mol. Ecol. 9, 1657–1659 (2000) .

Article CAS Google Scholar - Librado, P. & Rozas, J. DnaSP v5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics 25, 1451–1452 (2009) .

Article CAS Google Scholar - Wiens, J. J. Phylogenetic Analysis of Morphological Data 115–145 Smithsonian (2000) .

- Hall, T. A. BioEdit: a user-friendly biological sequence alignment editor and analysis program for Windows 95/98/NT. Nucleic Acids Symp. Ser. 41, 95–98 (1999) .

CAS Google Scholar - Zrzavý, J. & ŘIčánková, V. Phylogeny of Recent Canidae (Mammalia, Carnivora): relative reliability and utility of morphological and molecular datasets. Zoologica Scripta 33, 311–333 (2004) .

Article Google Scholar - Goloboff, P. A., Farris, J. S. & Nixon, K. C. TNT, a free program for phylogenetic analysis. Cladistics 24, 774–786 (2008) .

Article Google Scholar - Goloboff, P. A. Analyzing large data sets in reasonable times: Solutions for composite optima. Cladistics 15, 415–428 (1999) .

Article Google Scholar - Goloboff, P. A. et al. Improvements to resampling measures of group support. Cladistics 19, 324–332 (2003) .

Article Google Scholar - Coddington, J. & Scharff, N. Problems with zero-length branches. Cladistics 10, 415–423 (1994) .

Article Google Scholar - Reimer, P. J. et al. IntCal09 and Marine09 radiocarbon age calibration curves, 0-50,000 years CAL BP. Radiocarbon 51, 1111–1150 (2009) .

Article CAS Google Scholar - Stuiver, R. Extended 14C data base and revised CALIB 3.0 14C age calibration program. Radiocarbon 35, 215–230 (1993) .

Article Google Scholar - McCormac, F. G. et al. SHCal04 Southern Hemisphere calibration, 0–11.0 cal kyr BP. Radiocarbon 46, 1087–1092 (2004) .

Article CAS Google Scholar - Drummond, A. J. & Rambaut, A. BEAST: Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees. BMC Evol. Biol. 7, 214 (2007) .

Article Google Scholar - Minin, V. N., Bloomquist, E. W. & Suchard, M. A. Smooth skyride through a rough skyline: Bayesian coalescent-based inference of population dynamics. Mol. Biol. Evol. 25, 1459–1471 (2008) .

Article CAS Google Scholar - Rambaut, A. & Drummond, A. J. Tracer v1.4, Available from beast.bio.ed.ac.uk/Tracer (2007) .

- Ho, S. Y. W. et al. Bayesian estimation of substitution rates from ancient DNA sequences with low information content. Syst. Biol. 60, 366–375 (2011) .

Article CAS Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

We thank J. Rabassa and J. F. Ponce for comments and access to high-resolution versions of published figures, and F. Martin, M. Salemme, F. Santiago, O. Palacios and M. Silveira for access to the D. avus samples, and the Otago Museum for a sample of their FIW specimen. This work was funded by the Australian Research Council, PICT 2011-309 (ANPCyT), PIP 1054 and PIP 201101-00164 (CONICET).

Author information

Author notes

- Jeremy J. Austin and Julien Soubrier: These authors contributed equally to this work

Authors and Affiliations

- Australian Centre for Ancient DNA, School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, The University of Adelaide, North Terrace, Adelaide, 5005, South Australia, Australia

Jeremy J. Austin, Julien Soubrier & Alan Cooper - Department of Sciences, Museum Victoria, Carlton Gardens, Melbourne, 3001, Victoria, Australia

Jeremy J. Austin - División of Mastozoología, Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales ‘Bernardino Rivadavia’—CONICET, Avenida Angel Gallardo 470, Buenos Aires, C1405DJR, Argentina

Francisco J. Prevosti - División of Arqueología, Museo de La Plata, La Plata, 1900, Argentina

Luciano Prates - Martín Alonso Pinzón 6511, Las Condes, Santiago, Chile

Valentina Trejo - Centro de Investigación en Ecosistemas de la Patagonia (R10C1003), I. Serrano 509, Coyhaique, Chile

Francisco Mena

Authors

- Jeremy J. Austin

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Julien Soubrier

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Francisco J. Prevosti

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Luciano Prates

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Valentina Trejo

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Francisco Mena

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Alan Cooper

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

A.C. and J.J.A. conceived the study; F.J.P., L.P., V.T. and F.M. provided samples; J.J.A., J.S. and F.J.P. performed the experiments; and A.C., J.S. and J.J.A. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Corresponding author

Correspondence toAlan Cooper.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures S1-S5, Supplementary Tables S1-S4, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References (PDF 1368 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Austin, J., Soubrier, J., Prevosti, F. et al. The origins of the enigmatic Falkland Islands wolf.Nat Commun 4, 1552 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms2570

- Received: 04 October 2012

- Accepted: 01 February 2013

- Published: 05 March 2013

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms2570