Novel κ-opioid receptor agonist MB-1C-OH produces potent analgesia with less depression and sedation (original) (raw)

Introduction

Opioid receptors have been classified into μ-, κ-, and δ-opioid receptors based on their different pharmacological profiles1. Currently, most opioid analgesics, such as morphine, mainly induce analgesia via binding to the μ-opioid receptor, but they are also associated with a spectrum of undesirable side effects, such as physical dependence, respiratory depression, and constipation2. Numerous studies have demonstrated that drugs targeting κ-opioid receptor produced potent antinociception with less adverse and fewer addictive side effects than μ-opioid receptor agonists3,4,5. Endoh et al reported that TRK-820, a κ-opioid receptor agonist, was 68- to 328-fold more potent than (−)U50,488H, and 41- to 349-fold more potent than morphine in producing antinociception6. We previously found that LPK-26 produced potent antinociceptive effects without inducing physical dependence7. However, selective κ-opioid agonists frequently exhibit severe central nervous system side effects such as sedation and depression, which limit their clinical use8.

Increasing evidence from a wide variety of visceral pain models, inflammatory pain models and thermal hyperalgesia induced by capsaicin show that κ-opioid agonists could produce their analgesic effects via peripheral targeting9,10,11,12,13. Thus, peripherally acting κ-opioid agonists may be more promising candidate pharmacotherapies for pain relief because they do not cause central nervous system side effects.

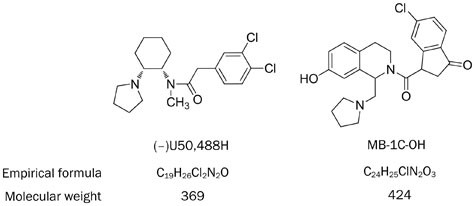

In this study, a novel synthetic compound, MB-1C-OH (empirical formula: C24H25ClN2O3, molecular weight: 424), in which a hydroxyl group was introduced in the parent framework of MB-1C, was examined (Figure 1). MB-1C-OH was characterized using in vitro and in vivo experiments. Specifically, MB-1C-OH's binding affinity for opioid receptors (μ, κ, and δ) and ability to stimulate guanosine 5′-O-(3-[35S]thio) triphosphate ([35S]GTPγS) binding to G-proteins were determined. The antinociceptive effects of MB-1C-OH were evaluated in the hot plate, tail flick, acetic acid-induced writhing and formalin tests.

Figure 1

Chemical structures of (−)U50,488H and MB-1C-OH.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells were transfected with human κ-, rat μ-, or rat δ-opioid receptors using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) as per the manufacturer's protocol. CHO cells stably expressing human κ-, rat μ-, or rat δ-opioid receptors were maintained in F12 medium (Gibco) with 10% fetal calf serum and 0.25 mg/mL G418 (Roche). Cells were incubated in a humidified atmosphere consisting of 5% CO2, 95% air at 37 °C. For the receptor binding assay and the [35S]GTPγS binding assay, cells were seeded into 175-cm3 flasks. When cell growth reached 70% confluence, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline and the membrane was prepared as follows.

Cell membrane preparation

CHO cells were detached by incubation with phosphate-buffered saline containing 1 mmol/L EDTA and centrifuged at 1000×g for 10 min. The cell pellet was suspended in ice-cold homogenization buffer composed of 50 mmol/L HEPES, pH 7.4; 1 mmol/L MgCl2; and 1 mmol/L EGTA. Cells were homogenized with 10 strokes using a glass Dounce homogenizer. After centrifugation at 40 000×g for 10 min (4 °C), pellets were resuspended in homogenization buffer, homogenized, and centrifuged again as described. This procedure was repeated twice more. The final pellets were resuspended in 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.4. The protein concentration was determined, and aliquots were stored at −80 °C.

Receptor binding assay

Ligand binding experiments were performed with [3H]diprenorphine for opioid receptors. Competition inhibition of [3H]diprenorphine binding to opioid receptors by MB-1C-OH or (−)U50,488H was performed in the absence or presence at various concentration of each drug. The receptor binding assay was carried out in triplicate using 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4) at 37 °C for 30 min in a final volume of 0.5 mL with 30 μg of membrane protein. Naloxone (10 μmol/L, Sigma) was used to define nonspecific binding. Bound and free [3H]diprenorphine were separated by filtration under reduced pressure with GF/B filters (Whatman). The amount of radioactivity on the filters was determined using a liquid scintillation counter (Beckman LS6500).

GTPγS binding assay

[35S]GTPγS binding was performed as described previously14,15. Briefly, membranes (15 μg/sample) were incubated with 0.1 nmol/L [35S]GTPγS in a binding buffer composed of 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 1 mmol/L EDTA; 5 mmol/L MgCl2; 100 mmol/L NaCl; and 40 μmol/L GDP at 30 °C for 1 h in the presence of increasing concentrations of MB-1C-OH. Nonspecific binding was determined in the presence of nonradioactive GTPγS (10 μmol/L). Reactions were terminated by rapid filtration, and the amount of bound radioactivity was determined by liquid scintillation counting as described above. The percentage of stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding was calculated as 100×(cpmsample − cpmnonspecific)/(cpmbasal − cpmnonspecific).

Animals

Male Kunming strain mice (approximately 20 g) were obtained from the Laboratory Animal Center, Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). Mice were housed in groups and maintained in a 12/12 h light/dark cycle in a temperature controlled environment with free access to food and water. Ten to fifteen mice were used per treatment group. All animal treatments were strictly in accordance with the institutional guidelines of Animal Care and Use Committee, Shanghai Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Hot plate test

The hot plate test was performed according to the method we described previously4,16. Briefly, the hot plate temperature was set at 55 °C. Mice were placed on the heated smooth surface. The amount of time that elapsed before the mice showed the first signs of discomfort (hind-paw lifting, licking or shaking, and jumping) was recorded. Prior to drug administration, the nociceptive response for each mouse was measured two times. The mean of these two times was used as the basal response time for each mouse. A cut-off time of 60 s was used in the test to avoid tissue damage. Each test was undertaken 15 min after the drug was administered. The Maximum Possible Effect (% MPE) was calculated as: 100×(response time after drug treatment – basal response time before drug treatment)/(cut-off time – basal latency before response time without drug treatment).

Acetic acid-induced writhing test

The acetic acid-induced writhing test was performed in mice according to our previously reported procedure4,16. Abdominal constriction was induced by the injection of 0.6% acetic acid (10 mL/kg, ip). An abdominal constriction was defined as a wave of contraction of the abdominal musculature followed by extension of the hind limbs. Acetic acid solution was injected ip 15 min after the administration of the drug, and the number of abdominal constrictions was counted for 15 min after acetic acid administration. The Maximum Possible Effect (% MPE) was calculated as: 100×(mean abdominal constriction in vehicle treated group – constriction times in drug-treated animal)/mean abdominal constriction in vehicle treated group. In all experiments with mice, drugs were given by a subcutaneous (sc) route prior to acetic acid administration. To determine the in vivo agonist profile of MB-1C-OH, mice were pretreated with a κ-(or-binaltorphimine (Nor-BNI), 10 mg/kg, sc, -15 min)7,16,17, μ- (β-funaltrexamine (β-FNA), 10 mg/kg, sc, −24 h)18,19 or δ-(naltrindole, 3.0 mg/kg, sc, −30 min)20 opioid receptor antagonist before MB-1C-OH administration.

Tail flick test

The tail-flick assay was performed according to our previously reported procedure4,16. Briefly, a beam of light was focused on the dorsal surface of the tail approximately 1–2 cm from the tip, and the amount of time that it took the mouse to withdraw its tail from the noxious stimulus was recorded. Before drug administration, the nociceptive response of each mouse was measured twice with a between trial interval of 5 min, and the mean of the two trials was recorded as the basal response time without drug treatment. Mice that did not have a basal response time between 2 and 7 s were excluded from further studies. A cut-off time of 14 s was employed as the maximum possible duration in the test after drug treatment in order to prevent tissue damage. The test was conducted 15 min after the administration of the drug. The Maximum Possible Effect (% MPE) was calculated as follows: 100×(response time after drug treatment – basal response time before drug treatment)/(cut-off time – basal latency before drug treatment).

Formalin test

The formalin test was performed according to the method described previously21. Briefly, 20 μL of 1.0% formalin was injected to the plantar surface of the right hind paw. The mice were observed for 60 min after the injection of formalin, and the amount of time that the mice spent licking or flinching the injected hind paw was recorded. The first 10 min after an injection of formalin was recorded as the early phase, and the period between 10 min and 60 min was recorded as the late phase. The drugs were administered 15 min before the injection of formalin. The total time that the mice spent licking or flinching the injured paw (pain behavior) was measured with a stopwatch.

Forced swimming test (FST)

The forced swimming test was performed according to the method described previously22. Mice were put singly into transparent Plexiglas cylinders (height: 24 cm, diameter: 13 cm) containing water at a depth of 10 cm, maintained at 22 °C for 6 min. The amount of time that the mice remained immobile was recorded in seconds during the final 4 min of the test. The percentage of depression was calculated as:100×(immobility time)/240, and then, the ED50 value was calculated using software which was based on the Litchfield and Wilcoxon method23.

Rotarod test

The rotarod test was conducted using a procedure described previously16,24. The maximum time tested was prolonged from 60 s to 300 s. In brief, the machine was set at a fixed rotational rate of 8 rounds per minute. The animals were trained twice a day for three consecutive days to maintain their position for 300 s without falling off the rotarod. The formal test began 15 min after the administration of the drug. The duration time for each mouse to remain on the Rotarod was recorded in seconds. The percentage of sedation was calculated as 100×(300 - duration time after test drug treatment)/300 and was used to determine the ED50 values of the test drugs.

Drugs

[3H]diprenorphine (1.85 TBq/mmol) and guanosine 5-O-(3-[35S]thio)triphosphate ([35S]GTPγS) (38.11 TBq/mmol) were purchased from Amersham Biosciences (Piscataway, NJ, USA). (−)U50,488H; naloxone; naltrindole; nor-binaltorphimine; β-funaltrexamine; GTPγS and GDP were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). Morphine hydrochloride was purchased from Qinghai Pharmaceutical General Factory (Xining, China).

Statistical analysis

Curve-fitting analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 4.02 software. Results are expressed as the mean±SEM of at least three separate experiments. Statistical significance was determined using ANOVA (one- or two-way) followed by post hoc comparison using Dunnett's tests. When only two groups were compared, statistical significance was determined using unpaired Student's _t_-tests.

Results

Affinity, selectivity, and efficacy of MB-1C-OH

Competitive inhibition of [3H]diprenorphine binding to opioid receptors by MB-1C-OH was performed to examine the binding affinities of MB-1C-OH to the opioid receptors (μ, κ, and δ). The _K_i of MB-1C-OH was 35 nmol/L to inhibit the binding of [3H]diprenorphine to the κ-opioid receptor, whereas MB-1C-OH at concentrations as high as 100 μmol/L showed no affinity for the μ- or δ-opioid receptors (Table 1). In the [35S]GTPγS binding assay, MB-1C-OH had an _E_max (percentage of maximal stimulation) of 98.19% for the κ-opioid receptor. The EC50 of MB-1C-OH to stimulate [35S]GTPγS binding to the κ-opioid receptor was 16.7 nmol/L (Table 1).

Table 1 Affinity values (_K_i) for the binding to opioid receptors and EC50 values as well as maximal effects in stimulating [35S]GTPγS binding to membranes of MB-1C-OH and (−)U50,488H in CHO cells stably expressing opioid receptors.

Antinociceptive effects of MB-1C-OH were mediated by the κ-opioid receptor

As shown in Table 2, in the hot plate and tail flick tests, MB-1C-OH had no significant antinociceptive effects. MB-1C-OH (10 mg/kg, sc) did not produce significant analgesic effects in both mouse hot plate and tail flick tests, which was similar to the data that we got from dose of 6 mg/kg (data not shown). Morphine and (−)U50,488H produced antinociception in the hot plate test with ED50 values of 6.95 and 4.42 mg/kg, respectively, and in the tail flick test with ED50 values of 3.46 and 5.02 mg/kg, respectively.

Table 2 ED50 values of the maximal possible effect (% MPE) produced by MB-1C-OH, morphine, and (−)U50,488H evaluated with hot plate, tail flick and acetic acid-induced writhing tests.

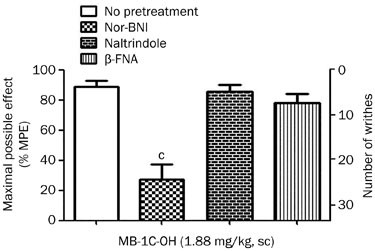

In the mouse acetic acid-induced writhing test, MB-1C-OH produced significant antinociception with an ED50 value of 0.39 mg/kg, which was approximately 2.3-fold smaller than the ED50 for (−)U50,488H (0.89 mg/kg), and 2.1-fold smaller than the ED50 for morphine (0.84 mg/kg) (Table 2). The antinociceptive effect of MB-1C-OH in the acetic acid-induced writhing test was also completely antagonized by the κ-opioid receptor antagonist nor-BNI but not by the μ- or δ-opioid receptor antagonists (Figure 2). One-way ANOVA tests (_F_3, 36=22.34, P<0.01) and the following post hoc comparison using Dunnett's tests (P<0.01) revealed a significant effect of the ability of nor-BNI to inhibit the antinociceptive effect of MB-1C-OH. These results suggested that the κ-opioid receptor is involved in MB-1C-OH-mediated antinociceptive effects.

Figure 2

Effects of pretreatment with nor-BNI, β-FNA, and naltrindole on MB-1C-OH-induced antinociception in the acetic acid-induced writhing assay. Mice were pretreated with the μ-opioid receptor antagonist, β-FNA (10 mg/kg, sc) 24 h before MB-1C-OH administration; the δ-opioid receptor antagonist, naltrindole (3.0 mg/kg, sc) 30 min before MB-1C-OH administration; or the selective κ-opioid receptor antagonist, nor-BNI (10 mg/kg, sc) 15 min before MB-1C-OH administration and then injected with MB-1C-OH (1.88 mg/kg, sc). Acetic acid solution was intraperitoneally injected 15 min after drug administration. The maximum possible effect (% MPE) was calculated as described in the Materials and methods section, and the number of times the mouse writhed is also shown. Data are presented as the mean±SEM from 10 animals. c_P_<0.01 compared with the control group.

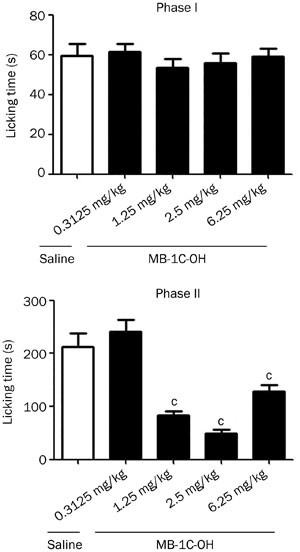

In the formalin test, MB-1C-OH dose-dependently inhibited formalin-induced pain only in the second phase with an ED50 of 0.87 mg/kg (Figure 3, Table 3), which was similar to the pattern of antinociception produced by (−)U50,488H but different from the antinociception produced by morphine. In Figure 3, one-way ANOVA tests (_F_4, 45=22.53, P<0.01) and the following post hoc comparison using Dunnett's tests revealed that doses of 1.25 mg/kg (P<0.01), 2.5 mg/kg (P<0.01) and 6.25 mg/kg (P<0.01) of MB-1C-OH could significantly inhibit formalin-induced pain in second phase. As shown in Table 3, (−)U50,488H produced antinociception on the second phase with an ED50 of 0.41 mg/kg. Morphine acted on both phases with ED50 values of 5.05 mg/kg in the first phase and 3.06 mg/kg in the second phase.

Figure 3

MB-1C-OH-induced antinociceptive effects in the formalin test. The animals were pretreated with MB-1C-OH into subcutaneous. After 15 min, the animals were injected with formalin (20 μL/paw). The amount of time the mice spent licking or flinching during first phase and second phase was recorded. All data are expressed as the mean±SEM (at least five animals in each group). c_P_<0.01 compared with the vehicle group (one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's test).

Table 3 ED50 of each drug maximal possible effect (% MPE) measured by the formalin test in mice.

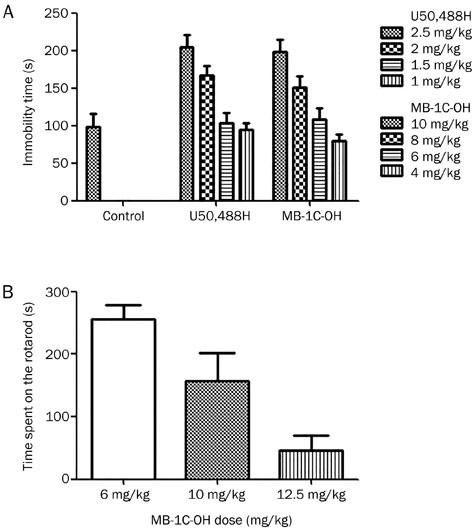

Depressive side effect of MB-1C-OH in the forced swimming test

MB-1C-OH and (−)U50,488H dose-dependently increased the immobility time during the forced swimming test (Figure 4A). As shown in Table 4, the depressive ED50 of MB-1C-OH in the FST was 9.49 mg/kg, which was 4 times higher than that of (−)U50,488H (2.35 mg/kg). The ratio of the depressive ED50 to the antinociceptive ED50 of MB-1C-OH was 24.33, which was 9.2 times higher than that of (−)U50,488H (2.64), suggesting that MB-1C-OH has a lower potential to cause depression than the classical κ-opioid agonist (−)U50,488H.

Figure 4

The depressive effect of MB-1C-OH in the forced swimming test and the sedative effect of MB-1C-OH in the rotarod test. (A) Mice were administered (sc) saline, (−)U50,488H or MB-1C-OH. After 15 min, they were put singly into transparent Plexiglas cylinders containing water at a depth of 10 cm for 6 min. The immobility time was recorded during the final 4 min. Data for each group are presented as the mean±SEM from 5–12 animals. (B) Mice were subcutaneously administered various doses of MB-1C-OH. Then, 15 min later, mice were put singly on a rotarod for 300 s. The duration time before each mouse fell off the rotarod was recorded. Data for each group are presented as the mean±SEM from 10 animals.

Table 4 Depression effects in mouse forced swimming test and sedation effects in mouse rotarod test.

Sedative side effect of MB-1C-OH in the rotarod test

κ-opioid agonists often produce the undesirable side effect of sedation in therapeutic use. MB-1C-OH also caused a dose-dependent inhibition in rotarod performance (Figure 4B). As shown in Table 4, the sedative ED50 values of MB-1C-OH and (−)U50,488H were 9.29 mg/kg and 3.32 mg/kg, respectively. The ratio of the sedative ED50 to the antinociceptive ED50 of MB-1C-OH was 23.82, which was 6.4 times higher than that of (−)U50,488H (3.73), suggesting that MB-1C-OH has a lower risk for causing sedation than (−)U50,488H.

Discussion

The present study demonstrated that MB-1C-OH had high affinity for the κ-opioid receptor with a _K_i value of 35 nmol/L in the receptor binding assay. With the [35S]GTPγS binding assay, a classical functional measurement for receptor activation that can be used to determine the potencies and efficacies of opioid ligands at opioid receptors25, we found that MB-1C-OH stimulated [35S]GTPγS binding to membrane receptors with an _E_max of 98% and an EC50 value of 16.7 nmol/L. These results indicate that MB-1C-OH is a highly selective, potent κ-opioid receptor agonist.

It have been well demonstrated that κ-agonists produce potent antinociception in different animal pain models9,11,12,13. Our findings were similar to these studies in that we found that MB-1C-OH produced a significant antinociceptive effect in the acetic acid-induced writhing test via κ- but not μ- or δ-opioid receptors. Furthermore, compared with morphine and (−)U50,488H, MB-1C-OH displayed more potent antinociception in the acetic acid-induced writhing test. In the formalin test, MB-1C-OH also significantly inhibited formalin-induced flinching behavior in the second phase. These results suggested that MB-1C-OH, a full κ-receptor agonist, produced potent antinociceptive effects and were similar to our previous findings4,7,16.

More importantly, we found that MB-1C-OH had no effects on the mouse hot plate and tail flick tests. Because the hot plate and tail flick tests both measure responses to thermal pain and often reflect central drug actions mediated by supraspinal and spinal mechanisms26,27, our results suggested that the antinociceptive effects of MB-1C-OH may occur via a peripheral- rather than a central-acting mechanism. We further evaluated the antinociception produced by MB-1C-OH using the acetic acid-induced writhing and formalin tests. These tests are both widely used to measure analgesic activity28,29,30. The formalin test occurs in two phases. The first phase is characterized by neurogenic pain caused by the direct chemical stimulation of nociceptors. The second phase is characterized by inflammatory pain triggered by a combination of stimuli31,32. Drugs that act primarily on the central nervous system inhibit both phases equally, whereas peripherally acting drugs only inhibit the late phase33. MB-1C-OH produced significant inhibition of flinching behavior in the second phase but not in the first phase, suggesting that its antinociceptive effect may be related to peripheral action on inflammatory pain. The precise mechanisms of MB-1C-OH-induced antinociception are of great interest and need to be elucidated in future studies. Many recent studies have shown that κ-opioid agonists produced analgesic effect via peripheral κ-opioid receptor9,10,11,12,13 without producing undesirable side effects.

Activation of the κ-receptor produces severe, undesirable central nervous system side effects, which limit the clinical utility of κ-receptor agonists for pain relief34,35. In the present study, we found that the depression and sedation ED50 values of MB-1C-OH are much higher than the ED50 value for antinociception. In contrast, the doses of (−)U50,488H that produce depression and sedation were similar to those that produce antinociception. These results demonstrated that MB-1C-OH produced less risk for sedation and depression than the classical κ-agonist (−)U50,488H.

In summary, MB-1C-OH, a novel selective κ-opioid receptor agonist, produced potent antinociceptive effects and little sedation and depression. Taken together, MB-1C-OH may be a promising analgesic for pain relief.

Author contribution

Jing-gen LIU, Yu-jun WANG, and Tao XI designed and supervised the research project; Yun-gen XU provided the compound; Le-sha ZHANG, Jun WANG, Yi-min TAO, Yu-hua WANG, Xue-jun XU, Jian-chun CHEN, Xiao-wu HU and Jie CHEN performed the experiments; Le-sha ZHANG, Jun WANG, and Yu-jun WANG analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript; Yu-jun WANG revised the manuscript.

References

- Trescot AM, Datta S, Lee M, Hansen H . Opioid pharmacology. Pain Physician 2008; 11: S133–53.

PubMed Google Scholar - Ballantyne JC . Opioid analgesia: perspectives on right use and utility. Pain Physician 2007; 10: 479–91.

PubMed Google Scholar - Clark JA, Pasternak GW . U50,488: a kappa-selective agent with poor affinity for mu1 opiate binding sites. Neuropharmacology 1988; 27: 331–2.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Sun JF, Wang YH, Li FY, Lu G, Tao YM, Cheng Y, et al. Effects of ATPM-ET, a novel κ agonist with partial μ activity, on physical dependence and behavior sensitization in mice. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2010; 31: 1547–52.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Wang YH, Sun JF, Tao YM, Chi ZQ, Liu JG . The role of kappa-opioid receptor activation in mediating antinociception and addiction. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2010; 31: 1065–70.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Endoh T, Matsuura H, Tajima A, Izumimoto N, Tajima C, Suzuki T, et al. Potent antinociceptive effects of TRK-820, a novel kappa-opioid receptor agonist. Life Sci 1999; 65: 1685–94.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Tao YM, Li QL, Zhang CF, Xu XJ, Chen J, Ju YW, et al. LPK-26, a novel kappa-opioid receptor agonist with potent antinociceptive effects and low dependence potential. Eur J Pharmacol 2008; 584: 306–11.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Negus SS, Mello NK, Portoghese PS, Lin CE . Effects of kappa opioids on cocaine self-administration by rhesus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1997; 282: 44–55.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Riviere PJ . Peripheral kappa-opioid agonists for visceral pain. Br J Pharmacol 2004; 141: 1331–4.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Stein C, Lang LJ . Peripheral mechanisms of opioid analgesia. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2009; 9: 3–8.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Binder W, Machelska H, Mousa S, Schmitt T, Riviere PJ, Junien JL, et al. Analgesic and antiinflammatory effects of two novel kappa-opioid peptides. Anesthesiology 2001; 94: 1034–44.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Jolivalt CG, Jiang Y, Freshwater JD, Bartoszyk GD, Calcutt NA, Dynorphin A . kappa opioid receptors and the antinociceptive efficacy of asimadoline in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Diabetologia 2006; 49: 2775–85.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Ko MC, Tuchman JE, Johnson MD, Wiesenauer K, Woods JH . Local administration of mu or kappa opioid agonists attenuates capsaicin-induced thermal hyperalgesia via peripheral opioid receptors in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2000; 148: 180–5.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Liu JG, Prather PL . Chronic exposure to mu-opioid agonists produces constitutive activation of mu-opioid receptors in direct proportion to the efficacy of the agonist used for pretreatment. Mol Pharmacol 2001; 60: 53–62.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Wen Q, Yu G, Li YL, Yan LD, Gong ZH . Pharmacological mechanisms underlying the antinociceptive and tolerance effects of the 6,14-bridged oripavine compound 030418. Acta Pharmacol Sin 2011; 32: 1215–24.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Portoghese AS, Lipkowski AW, Takemori AE . Bimorphinans as highly selective, potent kappa opioid receptor antagonists. J Med Chem 1987; 30: 238–9.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Wang YJ, Tao YM, Li FY, Wang YH, Xu XJ, Chen J, et al. Pharmacological characterization of ATPM [(−)-3-aminothiazolo[5,4-b]-_N_-cyclopropylmethylmorphinan hydrochloride], a novel mixed κ-agonist and μ-agonist/-antagonist that attenuates morphine antinociceptive tolerance and heroin self-administration behavior. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2009; 329: 306–13.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Jiang Q, Heyman JS, Porreca F . Mu antagonist and kappa agonist properties of b-funaltrexamine (b-FNA): long lasting spinal antinociception. NIDA Res Monogr 1989; 95: 199–205.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Vanderah TW, Schteingart CD, Trojnar J, Junien JL, Lai J, Riviere PJ . FE200041 (D-Phe-D-Phe-D-Nle-D-Arg-NH2): A peripheral efficacious kappa opioid agonist with unprecedented selectivity. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2004; 310: 326–33.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Saitoh A, Yoshikawa Y, Onodera K, Kamei J . Role of delta-opioid receptor subtypes in anxiety-related behaviors in the elevated plus-maze in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005; 182: 327–34.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Hunskaar S, Hole K . The formalin test in mice: dissociation between inflammatory and non-inflammatory pain. Pain 1987; 30: 103–14.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - David DJ, Renard CE, Jolliet P, Hascoet M, Bourin M . Antidepressant-like effects in various mice strains in the forced swimming test. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003; 166: 373–82.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Litchfield JT Jr, Wilcoxon F . A simplified method of evaluating dose-effect experiments. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1949; 96: 99–113.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Shiotsuki H, Yoshimi K, Shimo Y, Funayama M, Takamatsu Y, Ikeda K, et al. A rotarod test for evaluation of motor skill learning. J Neurosci Methods 2010; 189: 180–5.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Zhu J, Luo LY, Li JG, Chen C, Liu-Chen LY . Activation of the cloned human kappa opioid receptor by agonists enhances [35S]GTPgammaS binding to membranes: determination of potencies and efficacies of ligands. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1997; 282: 676–84.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Nemirovsky A, Chen L, Zelman V, Jurna I . The antinociceptive effect of the combination of spinal morphine with systemic morphine or buprenorphine. Anesth Analg 2001; 93: 197–203.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Rani S, Gupta MC . Evaluation and comparison of antinociceptive activity of aspartame with sucrose. Pharmacol Rep 2012; 64: 293–8.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Matsumoto A, Anan H, Maeda K . An immunohistochemical study of the behavior of cells expressing interleukin-1 alpha and interleukin-1 beta within experimentally induced periapical lesions in rats. J Endod 1998; 24: 811–6.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Vanderlei ES, Patoilo KK, Lima NA, Lima AP, Rodrigues JA, Silva LM, et al. Antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory activities of lectin from the marine green alga Caulerpa cupressoides. Int Immunopharmacol 2010; 10: 1113–8.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Shields SD, Cavanaugh DJ, Lee H, Anderson DJ, Basbaum AI . Pain behavior in the formalin test persists after ablation of the great majority of C-fiber nociceptors. Pain 2010; 151: 422–9.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Tjølsen A, Berge OG, Hunskaar S, Rosland JH, Hole K . The formalin test: an evaluation of the method. Pain 1992; 51: 5–17.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Puig S, Sorkin LS . Formalin-evoked activity in identified primary afferent fibers: systemic lidocaine suppresses phase-2 activity. Pain 1996; 64: 345–55.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Bitencourt Fda S, Figueiredo JG, Mota MR, Bezerra CC, Silvestre PP, Vale MR, Nascimento KS, et al. Antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects of a mucin-binding agglutinin isolated from the red marine alga Hypnea cervicornis. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2008; 377: 139–48.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Wadenberg ML . A review of the properties of spiradoline: a potent and selective kappa-opioid receptor agonist. CNS Drug Rev 2003; 9: 187–98.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Dortch-Carnes J, Potter DE . Bremazocine: a kappa-opioid agonist with potent analgesic and other pharmacologic properties. CNS Drug Rev 2005; 11: 195–212.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grants from the National Basic Research Program: a grant from the Ministry of Science and Technology of China 2009CB522005 (Jing-gen LIU) and grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China 81130087 (Jing-gen LIU) and 81171296 (Xiao-wu HU).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- State Key Laboratory of Drug Research, Shanghai Institute of Materia Medica and Collaborative Innovation Center for Brain Science, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai, 201203, China

Le-sha Zhang, Jun Wang, Yi-min Tao, Xue-jun Xu, Jie Chen, Yu-jun Wang & Jing-gen Liu - Biotechnology Center, School of Life Science and Technology, China Pharmaceutical University, Nanjing, 210009, China

Jun Wang, Yu-hua Wang, Yun-gen Xu & Tao Xi - Department of Neurosurgery, Changhai Hospital, Second Military Medical University, Shanghai, 200433, China

Jian-chun Chen & Xiao-wu Hu - School of Pharmacy, Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine, Nanjing, 210046, China

Yu-hua Wang

Authors

- Le-sha Zhang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Jun Wang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Jian-chun Chen

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Yi-min Tao

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Yu-hua Wang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Xue-jun Xu

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Jie Chen

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Yun-gen Xu

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Tao Xi

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Xiao-wu Hu

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Yu-jun Wang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Jing-gen Liu

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding authors

Correspondence toXiao-wu Hu or Yu-jun Wang.

PowerPoint slides

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Ls., Wang, J., Chen, Jc. et al. Novel κ-opioid receptor agonist MB-1C-OH produces potent analgesia with less depression and sedation.Acta Pharmacol Sin 36, 565–571 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/aps.2014.145

- Received: 09 August 2014

- Accepted: 10 November 2014

- Published: 30 March 2015

- Issue Date: May 2015

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/aps.2014.145