The DNA sequence of the human X chromosome (original) (raw)

Main

The X chromosome has many features that are unique in the human genome. Females inherit an X chromosome from each parent, but males inherit a single, maternal X chromosome. Gene expression on one of the female X chromosomes is silenced early in development by the process of X-chromosome inactivation (XCI), and this chromosome remains inactive in somatic tissues thereafter. In the female germ line, the inactive chromosome is reactivated and undergoes meiotic recombination with the second X chromosome. The male X chromosome fails to recombine along virtually its entire length during meiosis: instead, recombination is restricted to short regions at the tips of the X chromosome arms that recombine with equivalent segments on the Y chromosome. Genes inside these regions are shared between the sex chromosomes, and their behaviour is therefore described as ‘pseudoautosomal’. Genes outside these regions of the X chromosome are strictly X-linked, and the vast majority are present in a single copy in the male genome.

The unique properties of the X chromosome are a consequence of the evolution of sex chromosomes in mammals. The sex chromosomes have evolved from a pair of autosomes within the last 300 million years (Myr)1. In the process, the original, functional elements have been conserved on the X chromosome, but the Y chromosome has lost almost all traces of the ancestral autosome, including the genes that were once shared with the X chromosome. The hemizygosity of males for almost all X chromosome genes exposes recessive phenotypes, thus accounting for the large number of diseases that have been associated with the X chromosome[2](/articles/nature03440#ref-CR2 "McKusick-Nathans Institute for Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University and National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Library of Medicine. OMIM: Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim/

(2000)."). The characteristic pattern of X-linked inheritance (affected males and no male-to-male transmission) was recognized by the eighteenth century for some cases of haemophilia, and gave impetus in the 1980s to the earliest successes in positional cloning—of the genes for chronic granulomatous disease[3](/articles/nature03440#ref-CR3 "Royer-Pokora, B. et al. Cloning the gene for an inherited human disorder—chronic granulomatous disease—on the basis of its chromosomal location. Nature 322, 32–38 (1986)") and Duchenne muscular dystrophy[4](/articles/nature03440#ref-CR4 "Monaco, A. P. et al. Isolation of candidate cDNAs for portions of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy gene. Nature 323, 646–650 (1986)"). For females, the major consequence of the loss of genes from the Y chromosome is XCI, which equalizes the dosage of X-linked gene products between the sexes.The biological consequences of sex chromosome evolution account for the intense interest in the human X chromosome in recent decades. However, evolutionary processes are likely to have shaped the behaviour and structure of the X chromosome in many other ways, influencing features such as repeat content, mutation rate, gene content and haplotype structure. The availability of the finished sequence of the human X chromosome, described here, now allows us to explore its evolution and unique properties at a new level.

The X chromosome sequence

We constructed a map of the X chromosome using predominantly P1-artificial chromosome (PAC) and bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clones (Supplementary Table 1), which were assembled into contigs using restriction-enzyme fingerprinting and integrated with earlier maps using sequence-tagged site (STS) content analysis5. Gaps were closed by targeted screening of clone libraries in bacteria or yeast, and by assessing BAC and fosmid end-sequence data for evidence of spanning clones. Fourteen euchromatic gaps remain intractable, despite using libraries with a combined 80-fold chromosome coverage. Five of these gaps are within the 2.7 megabase (Mb) pseudoautosomal region at the tip of the chromosome short arm (PAR1). This is reminiscent of the situation in other human sub-telomeric regions6, and might reflect cloning difficulties in an area with a high content of (G + C) nucleotides and minisatellite repeats.

We selected 1,832 clones from the map for shotgun sequencing and directed finishing using established procedures7. Finished sequences were estimated to be more than 99.99% accurate by independent assessment8. The sequence of the X chromosome has been assembled from the individual clone sequences and comprises 16 contigs. These extend into the telomeric (TTAGGG)n repeat arrays at the ends of the chromosome arms, and include both pseudoautosomal regions (PARs). The data were frozen for the analyses described below, at which point we had determined 150,396,262 base pairs (bp) of sequence (Supplementary Table 2). Subsequently, we obtained a further 609,664 bp of sequence. The 14 euchromatic gaps are estimated to have a combined size of less than 1 Mb (see Methods and Supplementary Table 2), and the sequence therefore covers at least 99.3% of the X chromosome euchromatin. There is also a single heterochromatic gap corresponding to the polymorphic 3.0 (± 0.4) Mb array9 of alpha satellite DNA at the centromere. On this basis, we conclude that the X chromosome is approximately 155 Mb in length.

The coverage and quality of the finished sequence have been assessed using independent data. All markers from the deCODE genetic map10 are found in the sequence and the concordance of marker orders is excellent with only one discrepancy. DXS6807 is the most distal Xp marker on the deCODE map (4.39 cM), but in the sequence this marker is proximal to three others with genetic locations of 9–11 cM on the deCODE map. Out of 788 X chromosomal RefSeq11 messenger RNAs that were assessed, 783 were found completely in the sequence, and parts of four others are also present (T. Furey, personal communication). The missing segments of GTPBP6, CRLF2, DHRSX and FGF16 lie within gaps 1, 4, 5 and 10, respectively, and the GAGE3 gene is in gap 7 (Supplementary Table 2). The sequence assembly was assessed using fosmid end-sequence pairs that match the X chromosome sequence. The orientation and separation of end-pairs of more than 17,000 fosmids were consistent with the sequence assembly. In two cases, sequences had been misassembled owing to long and highly similar repeats. There were six instances of large deletions in sequenced clones, which were resolved by determining fosmid sequences through the deleted regions. Finally, there were two cases of apparent length variation between the reference sequence and the DNA used for the fosmid library.

Features of the X chromosome sequence

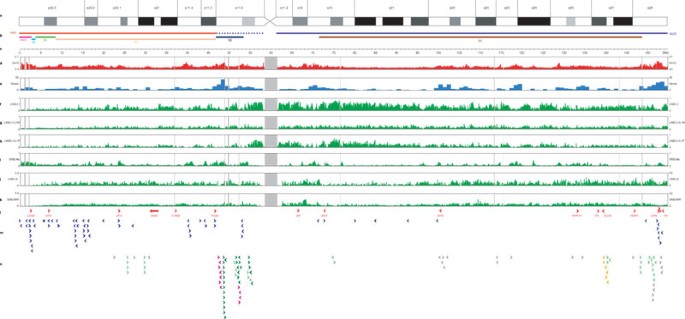

The annotated sequence of the X chromosome is presented in Supplementary Fig. 1, and updates are contained in the Vertebrate Genome Annotation (VEGA) database (http://vega.sanger.ac.uk/Homo_sapiens/). The distribution of a number of sequence features on the chromosome is shown in Fig. 1. Analysis of the sequence reveals a gene-poor chromosome that is highly enriched in interspersed repeats and has a low (G + C) content (39%) compared with the genome average (41%).

Figure 1: Features of the X chromosome sequence.

To view a larger version of this image download the pdf (126KB).

a, X chromosome ideogram according to Francke65. b, Evolutionary domains of the X chromosome: the X-added region (XAR), the X-conserved region (XCR; dotted region in proximal Xp does not appear to be part of the XCR), the pseudoautosomal region PAR1, and evolutionary strata S5–S1. c, Sequence scale in intervals of 1 Mb. Note that correlation between cytogenetic band positions and physical distance is imprecise, owing to varying levels of condensation of different Giemsa bands. d, (G + C) content of 100-kb sequence windows. e, Number of genes in 1-Mb sequence windows (pseudogenes not included). f–k, Fractional coverage of 100-kb sequence windows by interspersed repeats: L1 repeats (f), L1M subfamilies of L1 repeats (g), L1P subfamilies of L1 repeats (h), Alu repeats (i), L2 repeats (j), MIR repeats (k). Vertical grey lines in d–k represent gaps in the euchromatic sequence of the chromosome. Grey bar centred at approximately 60 Mb shows the position of the centromere. l, A selection of landmark genes on the chromosome. OPN refers to the three opsin genes in the reference sequence, which are organized as follows: cen-_OPN1LW_-_OPN1MW_-_OPN1MW_-tel. m, Genes that escape from X-chromosome inactivation as previously identified48. n, Cancer-testis antigen genes, belonging to the MAGE (light green), GAGE (dark green), SSX (magenta), SPANX (orange) or other (grey) CT gene families. For the genes in l–n, arrows indicate the direction of transcription.

Genes

Based on a manual assessment of all publicly available human expressed sequences and genes from other organisms, we have annotated 1,098 genes (7.1 genes per Mb) across four different categories (see Methods): known genes (699), novel coding sequences (132), novel transcripts (166), and putative transcripts (101). We have also identified 700 pseudogenes in the sequence (4.6 pseudogenes per Mb), of which 644 are classified as processed and 56 as non-processed. The gene density (excluding pseudogenes) on the X chromosome is among the lowest for the chromosomes that have been annotated to date. This might simply reflect a low gene density on the ancestral autosomes. Alternatively, selection may have favoured transposition of particular classes of gene from the X chromosome to the autosomes during mammalian evolution. These could include developmental genes for which the protein products are required in double dose in males (or in females after XCI has occurred), or genes for which mutation in male somatic tissues is lethal.

Physical characteristics of the genes and pseudogenes are summarized in Supplementary Table 3. Exons of the 1,098 genes account for only 1.7% of the X chromosome sequence. On the basis of the lengths of these gene loci, 33% of the chromosome is transcribed. This is considerably below the recent estimates for chromosomes 6 (ref. 12), 9 (ref. 6), 10 (ref. 13) and 13 (ref. 14), to which the equivalent gene annotation procedure was applied (Supplementary Table 4), and is a reflection not just of low gene density on chromosome X but also of low gene length. For example, mean gene length is 49 kilobases (kb) on chromosome X compared with 57 kb on chromosome 13. Nevertheless, the X chromosome contains the largest known gene in the human genome, the dystrophin (DMD) locus in Xp21.1, which spans 2,220,223 bp. Consistent with its low gene density, the frequency of predicted CpG islands on the X chromosome is only 5.25 per Mb, which is exactly half of the estimated genome average7. There is an association with a CpG island for 49% of the known genes, the category for which the most complete gene structures are expected in the current annotation.

We identified evolutionarily conserved regions (ECRs) by comparing the X chromosome sequence to the genomes of mouse, rat, zebrafish and the pufferfishes Tetraodon nigroviridis and Fugu rubripes (Supplementary Table 5). There are 4,493 ECRs that are conserved between the X chromosome and all of the other species. Of these, 4,393 overlap with 4,373 annotated exons. The remaining 100 ECRs are most likely to be unannotated exons, although some could be highly conserved control or structural elements. From these data we conclude that we have annotated at least 97.8% of the protein-coding exons on the X chromosome ([4,373/(4,373 + 100)] × 100).

Non-coding RNA genes

The gene set described above includes non-coding RNA (ncRNA) genes only when there is supporting evidence of expression from complementary DNA or expressed-sequence-tag (EST) sources. Using a complementary approach, we analysed the X chromosome sequence using the Rfam15 database of structural RNA alignments, and predicted 173 ncRNA genes and/or pseudogenes (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 6). These are physically separate from the genes described in the preceding section and are not included in the total gene count, owing to the difficulty in discriminating between genes and pseudogenes for these ncRNA predictions. Using tRNAscan-SE16, we predicted only two transfer RNA genes on the X chromosome (Supplementary Table 6), out of the several hundred predicted in the human genome7. Thirteen microRNAs from the microRNA registry17 have also been mapped onto the sequence (Supplementary Table 7).

The most prominent of the ncRNA genes on the X chromosome is XIST (X (inactive)-specific transcript)18, which is critical for XCI. The XIST locus spans 32,103 bp in Xq13, and its untranslated transcript coats and transcriptionally silences one X chromosome in cis. The RefSeq11 transcript of XIST is an RNA of 19,275 bases, which includes the largest exon on the chromosome (exon 1: 11,372 bp). There is also evidence for shorter XIST transcripts generated by alternative splicing, particularly in the 3′ region of the gene19. In the mouse, Tsix is antisense to Xist20, and its transcript (or the process of its transcription) is believed to repress the accumulation of Xist RNA. There is evidence for transcription antisense to XIST in human21,22, but we have been unable to annotate the human TSIX gene as there are no corresponding expressed sequences in the public databases, and because there is a lack of primary sequence conservation between the human and mouse regions. In the human sequence, two other ncRNA genes are annotated in the 400 kb region distal to XIST, which are orthologues of the mouse genes described previously as Jpx and Ftx (ref. 23). In the mouse, Xist, Jpx and Ftx are located within a smaller area of approximately 200 kb23.

The cancer-testis antigen genes

On assessing the predicted proteome of the X chromosome for Pfam24 domains, our most prominent finding was the presence of the MAGE domain (IPR002190) in 32 genes (Supplementary Table 8). In comparison, only four other MAGE genes are reported in the rest of the genome: MAGEF1 on chromosome 3, and MAGEL2, NDN and NDNL2 on chromosome 15. The MAGE gene products are members of the cancer-testis (CT) antigen group, which are characterized by their expression in a number of cancer types, while their expression in normal tissues is solely or predominantly in testis. This expression profile has led to the suggestion that the CT antigens are potential targets for tumour immunotherapy. A recent report listed 84 CT antigen genes for the human genome25. The X chromosome gene set we describe above contains 99 CT antigen genes and includes novel members of the MAGE, GAGE, SSX, LAGE, CSAGE and NXF families (Supplementary Table 9). Assessment of the most recent RefSeq11 information shows that this set does not include two known MAGE genes (MAGEA5 and MAGEA7) and seven GAGE genes (GAGE3–7, 7B and 8), which are expected to lie in gaps 14 and 7, respectively (Supplementary Table 2). Furthermore, gaps 6 and 9 are also within regions of CT antigen gene duplication. Therefore, we predict that approximately 10% of the genes on the X chromosome are of the CT antigen type.

Conclusive data on the normal functions of the CT antigens, or their involvement in disease conditions, are very limited. However, the remarkable enrichment for CT antigen genes on the X chromosome relative to the rest of the genome might be indicative of a male advantage associated with these genes. Recessive alleles that are beneficial to males are expected to become fixed more rapidly on the X chromosome than on an autosome26. If these alleles are detrimental to females, their expression could become restricted to male tissues as they rise to fixation. Both the concentration of the CT antigen genes on the X chromosome and their expression profiles are consistent with this model of male benefit. The CT antigen genes on the X chromosome are also notable for the expansion of various gene families by duplication. This degree of duplication is perhaps an indication of selection in males for increased copy number. In this context, it is of interest that the MAGE family has independently expanded on the X chromosome in both the human and mouse lineages27.

Repetitive sequences

Interspersed repeats account for 56% of the euchromatic X chromosome sequence, compared with a genome average of 45% (Supplementary Table 10). Within this, the Alu family of short interspersed nuclear elements (SINEs) is below average, in keeping with the gene-poor nature of the chromosome. Conversely, long terminal repeat (LTR) retroposon coverage is above average; but the most remarkable enrichment is for long interspersed nuclear elements (LINEs) of the L1 family, which account for 29% of the X chromosome sequence compared to a genome average of only 17%. The possible significance of this enrichment for XCI is discussed later.

Applying the criterion of at least 90% sequence identity over at least 5 kb (ref. 28), we estimate that intrachromosomal segmental duplications account for 2.59% of the X chromosome (Supplementary Table 11 and Supplementary Fig. 2). In contrast, interchromosomal segmental duplications indicated by sequence matches to the autosomes account for a very small fraction (0.24%) of the X chromosome (Supplementary Table 12). Six gaps in the X chromosome map are either flanked by or contained within intrachromosomally-duplicated segments (gaps 2, 3, 6, 7, 9 and 14 in Supplementary Table 2), which might produce instability of clones or otherwise confound mapping progress. The intrachromosomal duplicates are striking in their proximity. Apart from the two segments containing SSX gene copies, which are separated by 4.5 Mb, only six of 229 matches are separated by more than 1 Mb. Among these duplications are well-described cases that are associated with genomic disorders29. In Xp22.32, deletions of the steroid sulphatase (STS) gene, causing X-linked ichthyosis (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM)[2](/articles/nature03440#ref-CR2 "McKusick-Nathans Institute for Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University and National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Library of Medicine. OMIM: Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim/

(2000).") entry number 308100), result from recombination between flanking duplications that contain copies of the _VCX_ gene. Also, some instances of Hunter syndrome (OMIM 309900), red-green colour blindness (OMIM 303800), Emery-Dreifuss muscular dystrophy (OMIM 310300), incontinentia pigmenti (OMIM 308300) and haemophilia A (OMIM 306700) result from rearrangements involving duplicated sequences in Xq28\. In haemophilia A, mutations are frequently the result of inversions between a sequence in intron 22 of the _F8_ gene and one of two more distally located copies. A novel finding from our analysis of the X chromosome reference sequence is that the two distal copies are in opposite orientations. Therefore, a large deletion involving _F8_ and several more distal genes could be an alternative to the inversion rearrangement. A deletion consistent with this prediction has been reported in a family in which carrier females are affected by a high spontaneous-abortion rate in pregnancy[30](/articles/nature03440#ref-CR30 "Pegoraro, E. et al. Familial skewed X inactivation: a molecular trait associated with high spontaneous-abortion rate maps to Xq28. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 61, 160–170 (1997)").The X chromosome centromere

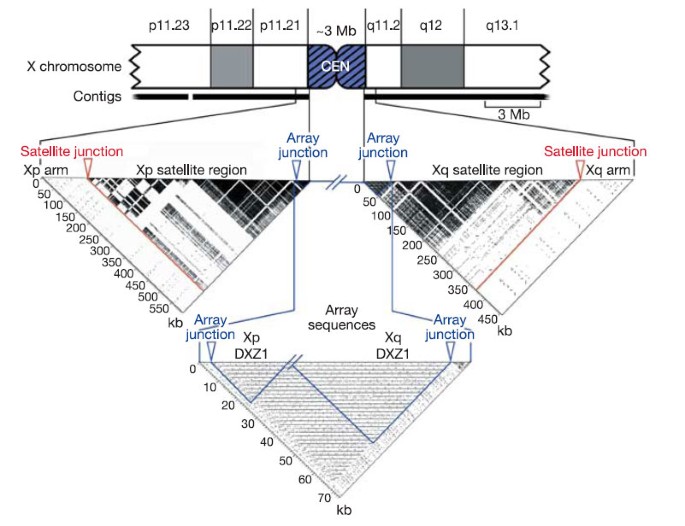

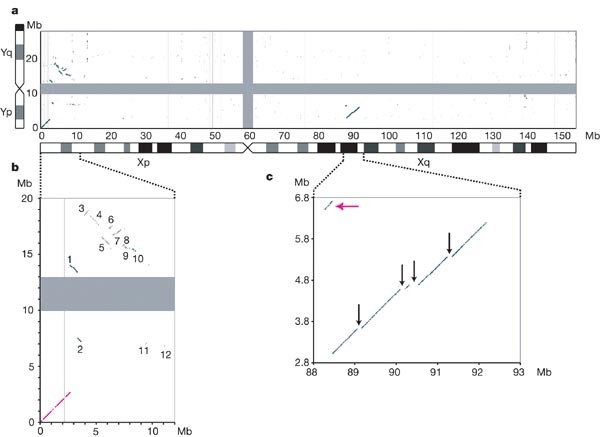

The X chromosome sequence extends from both arms into centromeric, higher-order repeat sequences, which are known to be associated functionally with the X centromere31,32,33. The most proximal 494 kb and 360 kb of the Xp and Xq sequences, respectively, consist of extensive regions of satellite DNA, adjacent to euchromatin of the chromosome arms that is exceptionally high in L1 content (Fig. 2). The satellite region on Xp contains small amounts of other satellite families31, whereas that on Xq consists entirely of alpha satellite. Similar to all other human chromosome arms that have been examined33,34, these transition regions consist of monomeric alpha satellite that is not associated with centromere function. Both the Xp and Xq contigs reported here, though, extend more proximally and reach into highly homogeneous, higher-order repeat alpha satellite (DXZ1). Critically, the Xp and Xq contig copies of the DXZ1 repeat are themselves 98–100% identical in sequence, and are oriented in the same direction along the chromosome (Fig. 2). On this basis, the two contigs reach the ‘end’ of each chromosome arm and thus also reach the centromeric locus from either side. This represents a logical endpoint for efforts to complete the sequence of chromosome arms in the human genome, and the first demonstration of this endpoint is provided by the X chromosome sequence.

Figure 2: Xp and Xq pericentromeric contigs extend into the X-chromosome-specific higher-order alpha satellite, DXZ1.

The pericentromeric region of the X chromosome is shown as a truncated ideogram. Self-self alignments of proximal sequences from each arm are illustrated by dotter plots below the ideogram. On each plot, the junction between the arm sequence and the arm-specific satellite region is marked by a red arrow, and the junction between the arm-specific satellite region and the X-chromosome-specific alpha satellite array (DXZ1) is marked with a blue arrow. Approximately 594 kb of sequence were analysed from Xp, including ∼21 kb of DXZ1 sequence. The ∼454 kb of sequence analysed from Xq included ∼44 kb of DXZ1 sequence. In each case, ∼100 kb of arm sequence were included. The highly repetitive structure of pericentromeric satellites is in stark contrast to the near absence of repetitive structure in the arm sequences, despite an unusually high density of LINE repeats in these regions. Gaps in the dark satellite regions occur where interspersed elements (LINEs, SINEs and LTRs) interrupt the satellite sequences. In the Array Sequences dotter plot, the most proximal ∼21 kb of the Xp sequence is joined to the most proximal ∼44 kb of the Xq sequence. The periodic nature of the centromeric, higher-order alpha satellite array is evident. Black horizontal lines on the plot reveal near identity of sequences spaced at ∼2 kb intervals. This DXZ1 sample represents ∼65 kb of the 3 (± 0.4) Mb alpha satellite array. The regions outlined in blue are self-self alignments (’Xp DXZ1’ and ’Xq DXZ1’), and the remaining rectangular region of the plot is an alignment of Xp versus Xq DXZ1, which reveals the close relationship between DXZ1 sequences from each arm.

Single-nucleotide polymorphisms

A total of 153,146 candidate single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have been mapped onto the X chromosome sequence and are displayed in the VEGA database. These include 901 SNPs that result in non-synonymous changes in protein-coding regions, and are therefore candidate functional protein variants. The heterozygosity level on the X chromosome is known to be well below that of the autosomes, and this difference can be explained partly or entirely by population genetic factors35. Included in the mapped SNPs are 62,334 that were identified by alignment of flow-sorted X chromosome shotgun sequence reads to the X chromosome reference sequence. Using comparable sequence data for chromosome 20, we calculated that the heterozygosity level on the X chromosome is approximately 57% of that observed for the autosome.

Evolution of the human X chromosome

Males of the three mammalian groups—Eutheria (‘placental’ mammals), Metatheria (marsupials) and Prototheria (egg-laying mammals)—have X and Y sex chromosomes. Ohno proposed in 1967 that the mammalian sex chromosomes evolved from an autosome pair following their recruitment into a chromosomal system for sex determination1. A barrier to recombination developed between these ‘proto’ sex chromosomes, isolating the sex-determining regions and eventually spreading throughout the two homologues. In the absence of recombination, the accumulation of mutation events subsequently led to the degeneration of the Y chromosome. The sex chromosomes of birds are not homologous to those of the mammals. The sex chromosome system of birds evolved independently during the last 300 Myr, giving rise to homogametic (ZZ) male birds and heterogametic (ZW) female birds, in contrast to the mammalian system of XY males and XX females.

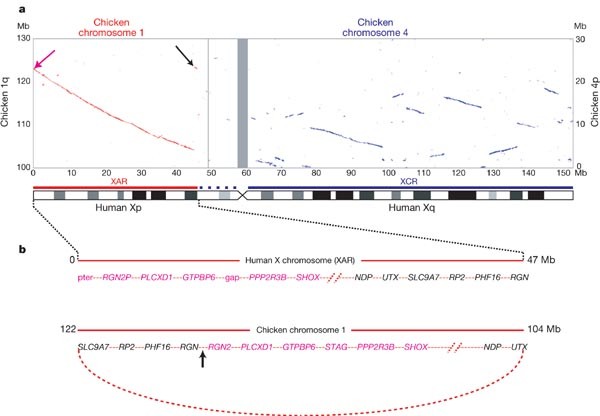

The autosomal origin of the mammalian sex chromosomes is vividly illustrated by alignment of the human X and chicken whole genome sequences (Fig. 3a). Orthologues of some human X chromosome genes were previously mapped to chicken chromosomes 1q13-q21 and 4p11-p14 (ref. 36). Using genomic sequence alignment, we identified approximately 30 regions of homology that together cover most of human Xq and are confined to a single section of approximately 20 Mb at the end of chicken chromosome 4p (Fig. 3a). In contrast, most of the short arm (Xp11.3–pter), including the pseudoautosomal region PAR1, matches a single block of chicken chromosome 1q. No clear picture emerges regarding the origin of the remainder of the short arm (Xcen–p11.3). We were unable to detect large regions of conserved synteny using sequence alignment, and genes from this region have orthologues on several chicken autosomes, including chromosomes 12, 1 and 4 (ref. 37). This region is also characterized by the expansion of several families of CT antigen genes (Fig. 1), which have no readily detectable orthologues in chicken. The present analysis supports the notion of a mammalian ‘X-conserved region’ (XCR)38, which includes the long arm and is descended from the proto-X chromosome. It also supports a separate, large addition (‘X-added region’ or XAR38) to the established X chromosome by translocation from a second autosome, which occurred in the eutherian mammals before their radiation (∼ 105 Myr ago). In contrast to earlier hypotheses, however, it appears that much of the proximal short arm (Xcen–p11.3) should no longer be considered part of an XCR.

Figure 3: Homologies between the human X chromosome and chicken autosomes.

a, Plot of BLASTZ sequence alignments between the X chromosome and chicken chromosomes 1 (red) and 4 (blue). Grey bar centred at approximately 60 Mb shows the position of the X centromere. Only the relevant section of each chicken chromosome is shown (see Mb scale at left for chromosome 1 and at right for chromosome 4). A schematic interpretation of the homologies shows the XAR and XCR as red and blue bars, respectively (see Fig. 1). Homologies at the ends of the XAR are indicated with arrows and are expanded in b. b, (Top) Genes at the ends of the human XAR. Genes from distal Xp (magenta arrow in a) are in magenta and genes from Xp11.3 (black arrow in a) are shown in black. (Bottom) Arrangement of the orthologous genes on chicken chromosome 1. A hypothetical ring chromosome, with the equivalent gene order to that observed in the chicken, is indicated by the curved, dotted red line. Recombination between one end of the established X chromosome and the ring chromosome at the arrowed position could, in a single step, have added the XAR and created the gene order observed on the human X chromosome.

The precise location of genes that demarcate the XAR suggests a possible mechanism for the addition. The annotated genes at the extreme ends of the 47 Mb XAR are PLCXD1 (cU136G2.1 in Supplementary Fig. 1) near Xpter, and RGN in Xp11.3. We also found an unprocessed RGN pseudogene (RGN2P) at Xpter, distal to PLCXD1. The orthologues for these three loci are adjacent on chicken chromosome 1, in the order (tel)–_RGN_–_RGN2_–_PLCXD1_–(cen) (Fig. 3b). The generation of these two different gene orders from a common ancestral sequence would require a minimum of two rearrangements as well as the translocation that added the XAR. A more parsimonious model suggested by these data, however, is that the XAR was acquired by recombination between the X chromosome and a ring chromosome in which the ancestral PLCXD1, RGN and RGN2 sequences were neighbours (Fig. 3b).

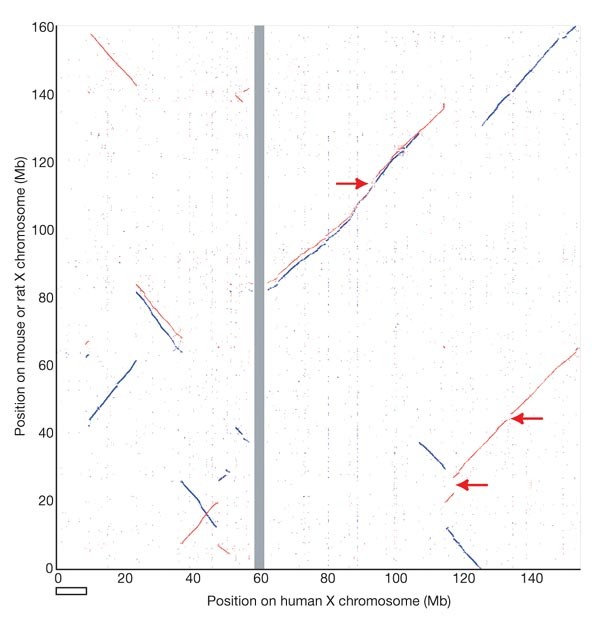

In order to examine more recent patterns of evolution, we compared the human X chromosome with other mammalian sequences. We saw nine major blocks of sequence homology between human and mouse X chromosomes, and eleven between human and rat (Fig. 4). The homology blocks occupy almost the entirety of each X chromosome, confirming the remarkable degree of conserved synteny of this chromosome within the eutherian mammalian lineage. This is consistent with Ohno's law, which predicts that the establishment of a dosage compensation mechanism had a stabilizing effect on the gene content of the mammalian X chromosome1. On the long arm, just two blocks of homology account for the entire alignment of the human and corresponding mouse sequences, but the mouse homologous regions are punctuated with three additional segments, each containing long and very similar repeats (arrowed in Fig. 4). Alignment of human Xq with the rat sequence reveals four discrete homology blocks; the greater fragmentation compared with the mouse alignment would be explained by a minimum of two rearrangements, one in each of the two mouse–human homology blocks, specifically on the rat lineage. The mouse-specific repeat segments are not detected in the current version of the rat genome sequence. On the short arm of the human X chromosome, seven major blocks of homology with each rodent account for most of the human sequence (Fig. 4). Using the dog as an outgroup, we established that the human and dog X chromosome sequences are essentially collinear (K. Lindblad-Toh, personal communication). Therefore, all of the rearrangements indicated in Fig. 4 occurred in the rodent lineage, and the human X chromosome appears to have been remarkably stable in its organization since the radiation of eutherian mammals. This is consistent with the recent prediction, derived from a comparison of human, rodent and chicken chromosomes, that the human X chromosome is identical to the putative ancestral (eutherian) mammalian X chromosome39.

Figure 4: Conservation of the X chromosome in eutherian mammals.

Plot of BLASTZ sequence alignments between the human X chromosome and the mouse (red) and rat (blue) X chromosomes. The rodent chromosomes are oriented with their centromeres pointing downwards. Regions indicated with arrows are long, highly similar repeats in the mouse sequence that are absent from the human and rat sequences. These repeats were apparently collapsed in an earlier analysed version of the mouse sequence, which also had a large inversion with respect to the mouse assembly used here (NCBI32)66. The NCBI32 assembly has a gap from 0–3 Mb, which explains the absence of homology to the human X sequence in this part of the plot. The open horizontal bar shows the terminal section of human Xp, which is not conserved on the rodent X chromosomes.

The most notable difference we found between the human and rodent X chromosomes is the existence of 9 Mb of sequence at the tip of the human short arm (including human PAR1) that is apparently missing from the rodent X chromosomes (Fig. 4). There are 34 known and novel protein-coding genes in this segment of the human X chromosome (Supplementary Fig. 1), enabling us to investigate how this difference arose. A comprehensive database search of the rodent genome sequences revealed convincing orthologues for only thirteen of these genes in rat and five in mouse. Most of the rat orthologues are located in two groups on chromosome 12, and the only genes for which X-linked orthologues could be found in both rodents were PRKX and STS. In contrast, we found 24 of these 34 genes on chicken chromosome 1, and the order of these genes is perfectly conserved between the two genomes. Therefore, we conclude that this large terminal segment was present in the XAR and was subsequently removed from the X chromosome in a common murid ancestor of mouse and rat. The relative paucity of rodent ECRs in this segment of the X chromosome sequence (Supplementary Fig. 1) suggests that much of the region may be absent altogether from the genomes of Mus musculus and Rattus norvegicus.

Comparison of the human X and Y chromosomes

The evolutionary process has eradicated most traces of the ancestral relationship between the human X and Y chromosomes. At the cytogenetic level, the Y chromosome has a large and variably sized heterochromatic block and is considerably smaller than the X chromosome, and the euchromatic part of the X chromosome is six times longer than that of Y. Few genes on human chromosome X have an active counterpart on the Y chromosome, and the majority of these are contained in regions where XY homology is of relatively recent origin.

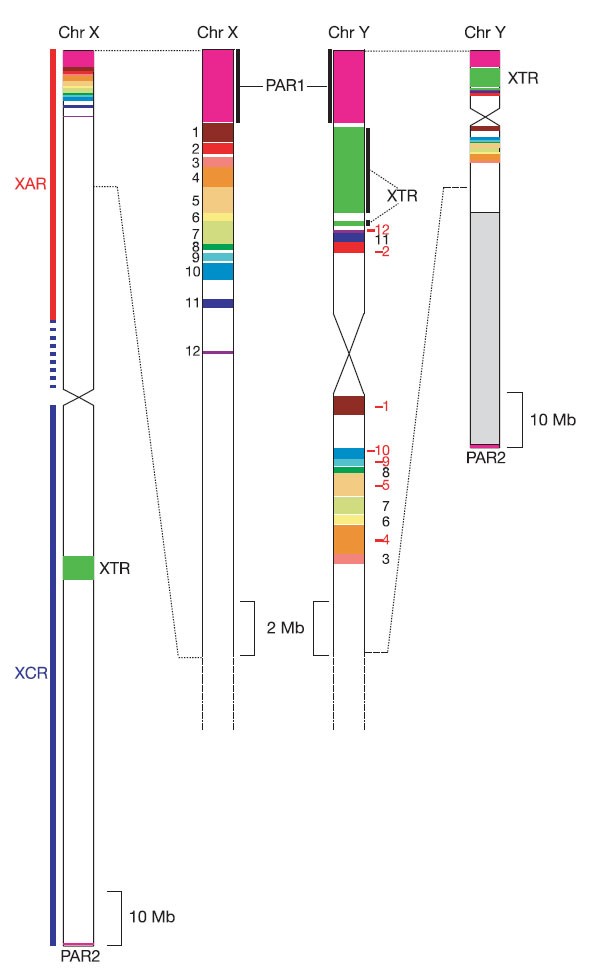

A detailed comparison of the human X and Y chromosome sequences reveals the extent of Y chromosome decay in non-recombining regions. All of the large homologous blocks visible in Fig. 5 (and represented schematically in Fig. 6) are descended from material that was added to the established sex chromosomes. The tip of the short arm of the X and Y chromosomes comprises the 2.7 Mb pseudoautosomal region PAR1. Homology between the X and Y chromosomes in PAR1 is maintained by an obligatory recombination in male meiosis; gene loci in this region are present in two copies in both males and females and are not subject to dosage compensation by XCI. At the tip of the long arm of X and Y is a second pseudoautosomal region, the 330 kb PAR2, which was created by duplication of material from X to Y since the divergence of human and chimpanzee lineages40. Some genes in PAR2 are subject to XCI, presumably reflecting their status on the X chromosome before the duplication event. Outside the PARs, homologies between the X and Y chromosomes are in non-recombining regions, predominantly in other parts of the XAR, together with a large ‘X-transposed region’ (XTR)41 in Xq21.3 and Yp11.2–p11.3 (see below). It is thought that the XAR originally formed a large pseudoautosomal region with an equivalent YAR, which is now largely eroded. At a gross level, the homology between the XAR and YAR is continuous for 6 Mb proximal to the pseudoautosomal boundary on the X (PABX), but is considerably more fragmented on the Y chromosome (Figs 5b and 6). Beyond this, the remaining 38.5 Mb of the XAR detects few other remnants of the YAR. Homologies are mostly in small islands around genes with functional orthologues on both sex chromosomes (for example, AMELX/AMELY, ZFX/ZFY, see Table 1).

Figure 5: Limited homology between the human sex chromosomes illustrates the extent of Y chromosome erosion in non-recombining regions.

a, BLASTN alignments (length ≥80 bp, sequence identity ≥70%) between the finished sequences of the X and Y chromosomes. The centromere positions are represented by grey bars. The analysed Y chromosome sequence ends at the large, heterochromatic segment on Yq, which is indicated by the black bar on the truncated Y chromosome ideogram. b, Major blocks of homology remaining between the XAR and the YAR. Expansion of the BLASTN plot from 0–12 Mb on the X chromosome and 0–20 Mb on the Y chromosome. On the X chromosome, the major homologies lie in the terminal 8.5 Mb of Xp: PAR1 (magenta line) and numbered blocks 1–10. Lesser homologies 11 and 12 contain the TBL1X/TBL1Y and AMELX/AMELY genes, respectively. c, The XTR region in detail (88–93 Mb on X and 2.8–6.8 Mb on Y). Black arrows show large segments deleted from the Y chromosome copy of the XTR. The magenta arrow indicates the short segment that is separated from the rest of the XTR by a paracentric inversion on the Y chromosome. An independent inversion polymorphism on Yp in human populations encompasses this small segment. The position and orientation of the segment shows that the Y chromosome reference sequence is of the less common, derived Y chromosome.

Figure 6: Schematic representation of major homologies between the human sex chromosomes.

The entire X and Y chromosomes are shown using the same scale on the left and right sides of the figure, respectively. The major heterochromatic region on Yq is indicated by the pale grey box proximal to PAR2. Expanded sections of X and Y are shown in the centre of the figure. Homologies coloured in the figure are either part of the XAR (PAR1 and blocks 1–12), or were duplicated from the X chromosome to the Y chromosome since the divergence of human and chimpanzee lineages (XTR and PAR2). The numbering of XAR-YAR blocks follows that in Fig. 5b. Blocks inverted on the Y chromosome relative to the X chromosome are assigned red, negative numbers.

Table 1 Homologous genes on the human X and Y chromosomes

The XTR arose by duplication of material from X to Y since the divergence of the human and chimpanzee lineages42. The duplicated region spans 3.91 Mb on X, but the corresponding region is only 3.38 Mb on the Y chromosome (Fig. 5c). We have aligned the entire X and Y copies of this region. Excluding insertions and deletions, sequence identity between the copies is 98.78%. We estimate that the transposition event occurred approximately 4.7 Myr ago (Supplementary Discussion 1), which is close to the suggested date of the speciation event that led to humans and chimpanzees, assumed here to be 6 Myr ago. The sequence alignment demonstrates the substantial changes to the XTR on the Y chromosome since the transposition. An inversion is known to have separated a 200-kb section from the rest of the XTR43 (Fig. 5c). Also, the main block of homology is 540 kb shorter on Y than X, owing in particular to the absence of four large regions from the Y chromosome (Fig. 5c). The detection of these sequences at the expected positions on the chimpanzee X chromosome confirms that they were deleted from the Y chromosome after the transposition.

We found that only 54 of the 1,098 genes annotated on the X chromosome have functional homologues on the Y chromosome (Table 1). We obtained direct evidence for 24 genes in PAR1. Twenty-three of them are annotated (Supplementary Fig. 1), and the location of the 5′ end of CRLF2 indicates that the rest of this gene is in gap 4 of the human X sequence (see the VEGA database). On the basis of the excellent conservation of synteny between human PAR1 and the chicken sequence, we infer that a stromal antigen gene (orthologue of chicken Ensembl gene ENSGALG00000016716) lies in gap 1 (see Fig. 3b). As the annotated putative transcript cM56G10.2 might represent the 3′ end of this gene, we conclude that PAR1 contains at least 24 genes. Together with the five annotated genes in PAR2, 29 genes lie entirely within the recombining regions of the sex chromosomes. Additionally, the XG locus spans the boundary between PAR1 and X-specific DNA, but has been disrupted by rearrangement on the Y chromosome.

Outside the XY-recombining regions of the X chromosome, we observed 25 genes that have functional homologues on the Y chromosome (Table 1). Fifteen of these are within the XAR, and a further three genes are shared by the X and Y copies of the XTR. The seven other XY gene pairs are believed to have descended from the proto-sex chromosomes. Only five cases have been described previously44,45: the X chromosome genes are SOX3, SMCX, RPS4X, RBMX and TSPYL2, which are located on the long arm and proximal short arm (Table 1). The two additional cases we report here involve heat-shock transcription factor genes, designated HSFX1 and HSFX2. They are assigned to the category of XCR genes on the basis of a high degree of divergence from their Y chromosome homologues and their location distal to SOX3 within the XCR. HSFX1 and HSFX2 lie within the separate copies of a palindromic repeat in Xq28 and are identical to each other. By analogy, their Y chromosome homologues (HSFY1 and HSFY2) lie within the arms of a Y chromosome palindrome, the similarity of which is thought to be maintained by gene conversion41.

On the basis of this and previously published information41, we can conclude that approximately 15 protein-coding genes on the Y chromosome have no detectable X chromosome homologue.

The progressive loss of XY recombination

The barrier to recombination between the proto-X and Y chromosomes initially encompassed the sex-determining locus on the Y (SRY) and possibly other loci affecting male fitness. It is proposed that rearrangement of the Y chromosome led to the development of this barrier. Thereafter, successive rearrangements that encompassed parts of the pseudoautosomal region resulted in segments of Y-linked DNA that could no longer recombine and consequently degenerated over time. Evidence for the role of Y-specific (as opposed to X-specific) rearrangement in this phenomenon is most clearly illustrated by our analysis of the XAR, which shows very little rearrangement between human and avian lineages (Fig. 3a).

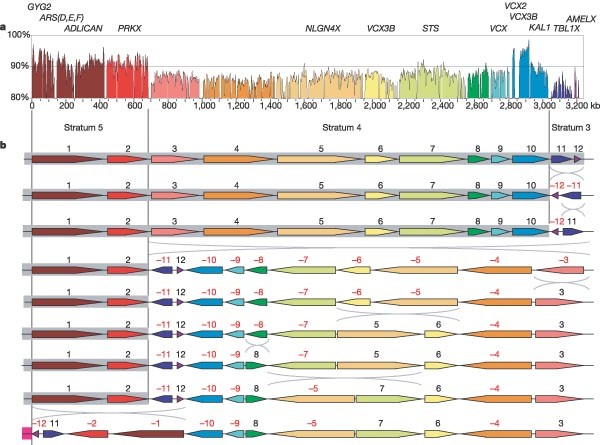

In a previous study46, four broad physical and evolutionary regions were defined on the X chromosome. The X chromosome genes within a given region all showed a similar level of divergence from their Y chromosome counterparts. However, between regions, levels of divergence were very different, presumably reflecting the stepwise loss of recombination between the X and Y chromosomes. The physical order of the four regions on the X chromosome was seen to parallel their evolutionary ages, and therefore the chromosome was described as having four “evolutionary strata”46. In general, gene pairs were found to be less divergent moving through the strata from Xqter to Xpter. The first two strata (S1 and S2) encompass the long arm and proximal short arm, respectively, and were defined by the genes that survive from the proto-sex chromosomes. Gene pairs were found to be increasingly similar moving through strata 3 and 4, which occupy the proximal and distal sections of the XAR, respectively.

We re-evaluated XY homology in S4 and S3 using finished, genomic sequences from the two chromosomes. For S4 in particular, substantial blocks of homology exist between the chromosomes (blocks 1–10 in Fig. 5b and Fig. 6). Aligning the X and Y chromosome sequences across this region, we observed a bipartite organization, with markedly greater XY identity in the distal 1.0 Mb compared with the proximal 4.5 Mb (Fig. 7a). On this basis, the distal portion containing the GYG2, ARSD, ARSE, ARSF, ADLICAN and PRKX genes can be redefined as a new, fifth stratum, S5 (Figs 1 and 7a). A most parsimonious series of inversions, from the current arrangement of homologous blocks on X to that on Y, is consistent with the proposed strata (Fig. 7b). These data refine the picture of loss of XY recombination during evolution, which occurred by migration of the PABX in a stepwise manner distally through the XAR. The available evidence now suggests that there have been at least four PABX positions within the XAR, which are at the S2/S3, S3/S4 and S4/S5 boundaries (∼ 47 Mb, ∼8.5 Mb and ∼4 Mb from Xpter, respectively), and at the current position (2.7 Mb from Xpter). We estimate that the two most recent PABX movements, which created first S4 and then S5, occurred 38–44 Myr ago and 29–32 Myr ago, respectively (Supplementary Discussion 2).

Figure 7: Evidence for a fifth evolutionary stratum on the X chromosome.

a, Sequence identity between the X and Y homology blocks 1–12 (see Figs 5b and 6) plotted in 5-kb windows. The scale shows the total amount of sequence aligned, excluding insertions and deletions (see Methods). A 10-kb spacer is placed between each consecutive block of homology. Segments of the plot are coloured according to the system used in Figs 6 and 7b. On the basis of this plot, a new evolutionary stratum S5 is defined, which includes homology blocks 1 and 2. b, A most parsimonious series of inversion events from the arrangement of homology blocks 1–12 on the X chromosome (top) to the Y chromosome (bottom), calculated using GRIMM64. The grey boxes show the suggested extents of former pseudoautosomal regions within the distal part of the XAR, and the magenta box (bottom row) shows the position of the current pseudoautosomal region. This inversion sequence provides independent support for the proposed pseudoautosomal boundary movements and evolutionary strata. It was previously suggested that AMELX (in block 12) is in S4 (ref. 46), or possibly at the boundary between S3 and S4 (ref. 67). However, the more distal location of block 11, which contains TBL1X (an S3 gene46), is not consistent with these suggestions. The two regions of increased sequence identity within block 10 contain the VCX2 and VCX3B genes on the X chromosome and the VCY1B and VCY genes on the Y chromosome. This gene family might have arisen de novo in the simian lineage68, which could account for the unusual characteristics of this part of the alignment.

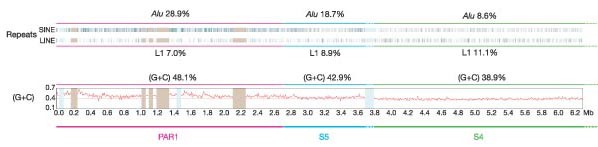

In addition to the varied degree of XY sequence identity within S3, S4, S5 and PAR1, we found marked differences in their sequence composition, which were presumably also caused by the loss of recombination in each region during evolution. Specifically, we observed that L1, L2 and mammalian interspersed repeat (MIR) coverage decrease with each more distal stratum and PAR1 (Table 2 and Fig. 1), but (G + C) levels and Alu repeat content increase abruptly at the boundary between S4 and S5 (Table 2 and Fig. 8); variations in the incidence of different Alu subfamilies (Y, S and J) also contribute to the distinct character of each stratum and PAR1 (Supplementary Table 13). The compositional differences between S4 and S5 provide additional support for the subdivision of the original stratum 4 (Fig. 8).

Table 2 Sequence characteristics of evolutionary domains of the X chromosome

Figure 8: Sequence compositional changes in the distal evolutionary strata of the X chromosome.

Shown are the positions of SINE and LINE repeats and (G + C) content within PAR1, S5 and the distal half of S4. The percentage of Alu, L1 and (G + C) are shown for each region (including the whole of S4). There is an abrupt increase in Alu repeat levels and (G + C) content from S4 to S5. The five euchromatic gaps in PAR1 are shown as light brown bars. Pale blue bars represent clones for which the sequences were unfinished at the time of the sequence assembly.

X-chromosome inactivation

XCI in mammals achieves dosage compensation between males and females for X-linked gene products. Inactivation of one X chromosome occurs early in female development and is initiated from the X-inactivation centre (XIC). The XIST transcript is expressed initially on both X chromosomes, but later the transcript from the chromosome that is destined for inactivation becomes more stable than the other. Finally, the transcript is expressed only from the inactive X chromosome (Xi). Coating with the XIST transcript is the earliest of many chromatin modifications on Xi.

XCI was first proposed based partly on the study of X:autosome translocations in female mice47. Studies of derivative chromosomes containing inactivated X chromosome segments later concluded that the inactivation could spread across the translocation boundary to the autosomal segment, but that inactivation of this segment was incomplete. More recently, it has become clear that more than 15% of the genes on the human X chromosome, including many without functional equivalents on the Y, escape from XCI, as presented in detail elsewhere48. The majority of the genes that escape XCI lie within the distal regions of the XAR (Fig. 1): all genes studied in PAR1, S5 and S4 were found to escape from XCI, but there is a lower proportion of escapees in S3, and very few examples in the XCR48. This observation correlates with our picture of X chromosome evolution: XCI follows Y chromosome attrition49, which is less advanced in the distal strata of the XAR.

Inefficient inactivation of the autosomal segment in Xi:autosome translocations led to the proposal that ‘way stations’ on the X chromosome boost the spread of XCI. According to this model, way stations are present throughout the genome but are enriched on the X chromosome, particularly in the region of the XIC50. Lyon suggested that L1 elements are good candidates for acting as way stations on account of their enrichment on the mammalian X chromosome51. We observe a distribution of L1 elements on the chromosome that is consistent with both the way station and the Lyon hypotheses (Fig. 1 and Table 2). The coverage of L1 repeats is very high in the XCR, especially around the XIC. As noted previously52, this enrichment in L1 levels is accounted for particularly by elements that were active more recently in mammalian evolution53 (L1P in Fig. 1). In the XAR, L1 coverage is close to autosome levels, whereas L1 levels are particularly low in the distal evolutionary strata of the XAR, where genes consistently escape inactivation. The XIST locus itself lies in a 60 kb region that is virtually devoid of L1 elements, whereas L1 levels are extremely high in the adjacent regions. Based on their distributions, other interspersed repeats are not strong candidates for way stations. For example, although L2 and MIR elements are reduced in S4, S5 and particularly PAR1 relative to the rest of the chromosome, their overall levels on the X chromosome are not enriched relative to the autosomes but are slightly reduced. Furthermore, L2 and MIR levels are low in the region distal to the XIC. These characteristics do not preclude an involvement in XCI, but are not consistent with a role as way stations.

The possible causal relationship of L1 elements to the spread of XCI remains a subject of debate. Some studies have reported significant associations between L1 coverage and inactivation52, and others have refuted this54. Our observations on regional differences in composition emphasize that such studies should compare active and inactivated genes (or domains) from the same evolutionary stratum, in order to avoid correlations that are unrelated to XCI.

Medical genetics and the X chromosome sequence

The X chromosome holds a unique place in the history of medical genetics. Ascertainment of X-linked diseases is enhanced by the relative ease of recognizing this mode of inheritance. More important, however, is the fact that a disproportionately large number of disease conditions have been associated with the X chromosome because the phenotypic consequence of a recessive mutation is revealed directly in males for any gene that has no active counterpart on the Y chromosome. Thus, although the X chromosome contains only 4% of all human genes, almost 10% of diseases with a mendelian pattern of inheritance have been assigned to the X chromosome (307 out of 3,199; information obtained from OMIM[2](/articles/nature03440#ref-CR2 "McKusick-Nathans Institute for Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University and National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Library of Medicine. OMIM: Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim/

(2000).")). These two aspects of the medical genetics of the X chromosome have greatly stimulated progress in the positional cloning of many genes associated with human disease. To date, the molecular basis for 168 X-linked phenotypes has been determined, and the X chromosome sequence has aided this process for 43 of them, by providing positional candidate genes or a reference sequence for comparison to patient samples ([Supplementary Table 14](/articles/nature03440#MOESM1)).Identifying genes involved in rare conditions yields important biological insights. For example, discovery of mutations in the SH2D1A gene55 (involved in X-linked lymphoproliferative disease (XLP, OMIM 308240)) led to identification of a new mediator of signal transduction between T and NK cells, and a novel family of proteins involved in the regulation of the immune response. Mental retardation is one of the most common problems in clinical genetics, and affects significantly more males than females. To date, 16 genes from the X chromosome have been associated with cases of non-syndromic X-linked mental retardation (NS-XLMR), in which mental retardation is the only phenotypic feature. These genes encode a range of protein types, and some are also involved in syndromic forms of mental retardation. For example, the ARX gene encodes an aristaless-related homeobox transcription factor and is linked to NS-XLMR cases, as well as to syndromic mental retardation associated with epilepsy (infantile spasm syndrome, ISSX, OMIM 308350) or with dystonic hand movements (Partington syndrome, PRTS, OMIM 309510)56. The MECP2 gene, which encodes a methyl-CpG-binding protein, was initially linked to cases of Rett syndrome in girls57 (RTT, OMIM 312750) but was later also seen to be mutated in males or females with NS-XLMR58. The molecular defect has been determined in only a minority of families affected by NS-XLMR, which has led to speculation that there could be as many as 100 genes on the X chromosome that are associated with NS-XLMR59. Discovering the genes for these and other rare, monogenic disorders is of critical value in extending our understanding of fundamental new processes in human biology, and the annotated X chromosome will further facilitate this process.

Concluding remarks

The completion of the X chromosome sequencing project is an essential component of the goal of obtaining a high-quality, annotated human genome sequence for use in studies of gene function, sequence variation, disease and evolution. It also means that for the first time, we now have the finished sex chromosome sequences of an organism. The study of these sequences gives a greater insight into mammalian sex chromosome evolution and its consequences. As these analyses are extended to other genomes, we will gain a greater appreciation of the different evolutionary forces that shape sex chromosome and autosome evolution. It will be important to study differences in the rates of mutational processes, and to consider the influence of the unusual pattern of male recombination on these processes. Clearly, this analysis should not be restricted to a consideration of mammalian sex chromosomes, and it will be of great interest to make comparisons with non-mammalian systems that arose independently in evolution.

Methods

The approach used to establish a bacterial clone map of the X chromosome has been previously described5. 13,264 clones were identified using 4,363 STS markers derived from published genetic or physical maps, from shotgun sequencing of flow-sorted X chromosomes, or from end-sequences of clones at contig ends. Clones were assembled into contigs using restriction-enzyme fingerprinting, and were integrated with the Washington University Genome Sequencing Center whole genome BAC map60 in order to identify additional clones. Nine euchromatic gaps were measured using fluorescent in situ hybridization of clones to extended DNA fibres, and a tenth gap was estimated on the basis of end-sequence data from spanning, unstable BAC clones (Supplementary Table 2). On the basis of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis experiments, we expect the sizes of the other four euchromatic gaps to have a combined size of less than 400 kb.

Finished sequences of individual clones were determined using procedures described in ref. 7. For the analyses described above, the sequence was frozen in March 2004, at which point 150,396,262 bp of sequence had been determined from a minimal tiling path of 1,832 clones (1,616 sequence accessions). This sequence is available at http://www.sanger.ac.uk/HGP/ChrX/, and its annotation is represented in Supplementary Fig. 1. Updates to the sequence and annotation can be obtained from the VEGA database.

Manual annotation of gene structures has been described elsewhere14, and used guidelines agreed at the human annotation workshop (HAWK; http://www.sanger.ac.uk/HGP/havana/hawk.shtml). Genes were assigned to one of four groups: (1) known genes that are identical to human cDNAs or protein sequences and have a RefSeq RNA (and RefSeq protein, if the gene encodes a protein); (2) novel coding sequences, which have an open reading frame (ORF) and are identical to spliced ESTs, or have similarity to other genes/proteins (any species); (3) novel transcripts, which are similar to novel coding sequences, except that no ORF can be determined with confidence; and (4) putative transcripts, which are identical to splicing human ESTs but have no ORF. Gene symbols were approved by the HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee wherever possible. Predicted protein translations were analysed for Pfam domains using InterProScan (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/InterProScan/). CpG islands were predicted using the program GpG (G. Micklem, personal communication).

Interspersed repeats were identified and classified using RepeatMasker (http://repeatmasker.genome.washington.edu). In order to search for segmental duplications, WU-BLASTN (http://blast.wustl.edu) was used to align the current X chromosome sequence to itself or to the NCBI34 autosome assemblies. Duplicated blocks at least 5 kb in length were defined as described in ref. 28.

SNPs (dbSNP release 119) were mapped onto the X chromosome sequence using first SSAHA61 and then Cross-match (http://www.phrap.org/phredphrapconsed.html).

Comparative analysis

The genome assemblies used for comparative analyses were: Gallus gallus WASHUC1 (Washington University Genome Sequencing Center, http://www.genome.wustl.edu/projects/chicken), Rattus norvegicus RGSC3.1 (Rat Genome Sequencing Consortium http://www.hgsc.bcm.tmc.edu/projects/rat/), Mus musculus NCBI32 (Mouse Genome Sequencing Consortium, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/seq/NCBIContigInfo.html), Danio rerio version 3 (Sanger Institute, http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/D_rerio), T. nigroviridis version 6 (Genoscope and the Broad Institute, http://www.genoscope.cns.fr/externe/tetraodon/Ressource.html), and F. rubripes version 2 (International Fugu Genome Consortium, http://www.fugu-sg.org/project/info.html). ECRs between the X chromosome and the rodent and fish genomes were obtained as described elsewhere13. In order to visualize regions of conserved synteny, the X chromosome sequence was aligned to the chicken and rodent genome sequences using BLASTZ (with default parameters), and matches were plotted by chromosome position. Matches to the rodent genomes were filtered to include only those with a sequence identity of at least 70% to the human sequence. The Ensembl database (http://www.ensembl.org) was used to search for orthologous gene pairs between the X chromosome and the other three genomes.

Genomic sequence homologies between the X and Y chromosomes were identified by aligning the two finished chromosome sequences using WU-BLASTN, and then filtering the alignments to include only those of at least 70% sequence identity and 80 bp length. In order to calculate the sequence identity between large, XY-homologous regions, a global alignment of unmasked sequence was generated using LAGAN62. Gapped regions, which result from insertions or deletions, were removed from the alignment, and then the nucleotide sequence identity was calculated for the remainder. Sequence identity plots were produced by parsing the LAGAN output into VISTA63. GRIMM64 was used to calculate a most parsimonious series of inversions that would account for differences in homology block order and orientation between the X and Y chromosomes. Homologous protein-coding gene pairs between the X and Y chromosomes were identified by TBLASTN searching with the coding sequences of annotated coding genes on the Y chromosome against the X chromosome genomic sequence.

References

- Ohno, S. Sex Chromosomes and Sex-linked Genes (Springer, Berlin, 1967)

Book Google Scholar - McKusick-Nathans Institute for Genetic Medicine, Johns Hopkins University and National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Library of Medicine. OMIM: Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/omim/ (2000).

- Royer-Pokora, B. et al. Cloning the gene for an inherited human disorder—chronic granulomatous disease—on the basis of its chromosomal location. Nature 322, 32–38 (1986)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Monaco, A. P. et al. Isolation of candidate cDNAs for portions of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy gene. Nature 323, 646–650 (1986)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Bentley, D. R. et al. The physical maps for sequencing human chromosomes 1, 6, 9, 10, 13, 20 and X. Nature 409, 942–943 (2001)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Humphray, S. J. et al. DNA sequence and analysis of human chromosome 9. Nature 429, 369–374 (2004)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature 409, 860–921 (2001)

Article Google Scholar - Schmutz, J. et al. Quality assessment of the human genome sequence. Nature 429, 365–368 (2004)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Mahtani, M. M. & Willard, H. F. Physical and genetic mapping of the human X chromosome centromere: repression of recombination. Genome Res. 8, 100–110 (1998)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Kong, A. et al. A high-resolution recombination map of the human genome. Nature Genet. 31, 241–247 (2002)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Pruitt, K. D., Katz, K. S., Sicotte, H. & Maglott, D. R. Introducing RefSeq and LocusLink: curated human genome resources at the NCBI. Trends Genet. 16, 44–47 (2000)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Mungall, A. J. et al. The DNA sequence and analysis of human chromosome 6. Nature 425, 805–811 (2003)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Deloukas, P. et al. The DNA sequence and comparative analysis of human chromosome 10. Nature 429, 375–381 (2004)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Dunham, A. et al. The DNA sequence and analysis of human chromosome 13. Nature 428, 522–528 (2004)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Griffiths-Jones, S., Bateman, A., Marshall, M., Khanna, A. & Eddy, S. R. Rfam: an RNA family database. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 439–441 (2003)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Lowe, T. M. & Eddy, S. R. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 25, 955–964 (1997)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Griffiths-Jones, S. The microRNA Registry. Nucleic Acids Res. 32 (Database issue), D109–111 (2004)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Brown, C. J. et al. A gene from the region of the human X inactivation centre is expressed exclusively from the inactive X chromosome. Nature 349, 38–44 (1991)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Brown, C. J. et al. The human XIST gene: analysis of a 17 kb inactive X-specific RNA that contains conserved repeats and is highly localized within the nucleus. Cell 71, 527–542 (1992)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Lee, J. T., Davidow, L. S. & Warshawsky, D. Tsix, a gene antisense to Xist at the X-inactivation centre. Nature Genet. 21, 400–404 (1999)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Migeon, B. R., Chowdhury, A. K., Dunston, J. A. & McIntosh, I. Identification of TSIX, encoding an RNA antisense to human XIST, reveals differences from its murine counterpart: implications for X inactivation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 69, 951–960 (2001)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Chow, J. C., Hall, L. L., Clemson, C. M., Lawrence, J. B. & Brown, C. J. Characterization of expression at the human XIST locus in somatic, embryonal carcinoma, and transgenic cell lines. Genomics 82, 309–322 (2003)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Chureau, C. et al. Comparative sequence analysis of the X-inactivation center region in mouse, human, and bovine. Genome Res. 12, 894–908 (2002)

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Bateman, A. et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 32 (Database issue), D138–141 (2004)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Scanlan, M. J., Simpson, A. J. & Old, L. J. The cancer/testis genes: review, standardization, and commentary. Cancer Immun. [online] 4, 1 (2004)

PubMed Google Scholar - Hurst, L. D. Evolutionary genomics: Sex and the X. Nature 411, 149–150 (2001)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Chomez, P. et al. An overview of the MAGE gene family with the identification of all human members of the family. Cancer Res. 61, 5544–5551 (2001)

CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Cheung, J. et al. Genome-wide detection of segmental duplications and potential assembly errors in the human genome sequence. Genome Biol. 4, R25 (2003)

Article Google Scholar - Stankiewicz, P. & Lupski, J. R. Genome architecture, rearrangements and genomic disorders. Trends Genet. 18, 74–82 (2002)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Pegoraro, E. et al. Familial skewed X inactivation: a molecular trait associated with high spontaneous-abortion rate maps to Xq28. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 61, 160–170 (1997)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Schueler, M. G., Higgins, A. W., Rudd, M. K., Gustashaw, K. & Willard, H. F. Genomic and genetic definition of a functional human centromere. Science 294, 109–115 (2001)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Spence, J. M. et al. Co-localization of centromere activity, proteins and topoisomerase II within a subdomain of the major human X alpha-satellite array. EMBO J. 21, 5269–5280 (2002)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Rudd, M. K. & Willard, H. F. Analysis of the centromeric regions of the human genome assembly. Trends Genet. 20, 529–533 (2004)

Article CAS Google Scholar - She, X. et al. The structure and evolution of centromeric transition regions within the human genome. Nature 430, 857–864 (2004)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - The International SNP Map Working Group. A map of human genome sequence variation containing 1.42 million single nucleotide polymorphisms. Nature 409, 928–933 (2001)

Article Google Scholar - Schmid, M. et al. First report on chicken genes and chromosomes 2000. Cytogenet. Cell Genet. 90, 169–218 (2000)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Kohn, M., Kehrer-Sawatzki, H., Vogel, W., Graves, J. A. & Hameister, H. Wide genome comparisons reveal the origins of the human X chromosome. Trends Genet. 20, 598–603 (2004)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Graves, J. A. The origin and function of the mammalian Y chromosome and Y-borne genes—an evolving understanding. Bioessays 17, 311–320 (1995)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Hillier, L. W. et al. Sequence and comparative analysis of the chicken genome provide unique perspectives on vertebrate evolution. Nature 432, 695–716 (2004)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Freije, D., Helms, C., Watson, M. S. & Donis-Keller, H. Identification of a second pseudoautosomal region near the Xq and Yq telomeres. Science 258, 1784–1787 (1992)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Skaletsky, H. et al. The male-specific region of the human Y chromosome is a mosaic of discrete sequence classes. Nature 423, 825–837 (2003)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Page, D. C., Harper, M. E., Love, J. & Botstein, D. Occurrence of a transposition from the X-chromosome long arm to the Y-chromosome short arm during human evolution. Nature 311, 119–123 (1984)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Sargent, C. A. et al. The sequence organization of Yp/proximal Xq homologous regions of the human sex chromosomes is highly conserved. Genomics 32, 200–209 (1996)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Toder, R., Wakefield, M. J. & Graves, J. A. The minimal mammalian Y chromosome - the marsupial Y as a model system. Cytogenet. Cell Genet. 91, 285–292 (2000)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Delbridge, M. L. et al. TSPY, the candidate gonadoblastoma gene on the human Y chromosome, has a widely expressed homologue on the X - implications for Y chromosome evolution. Chromosome Res. 12, 345–356 (2004)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Lahn, B. T. & Page, D. C. Four evolutionary strata on the human X chromosome. Science 286, 964–967 (1999)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Lyon, M. F. Gene action in the X-chromosome of the mouse (Mus musculus L.). Nature 190, 372–373 (1961)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Carrel, L. & Willard, H. F. X-inactivation profile reveals extensive variability in X-linked gene expression in females. Nature doi:10.1038/nature03479 (this issue)

- Jegalian, K. & Page, D. C. A proposed path by which genes common to mammalian X and Y chromosomes evolve to become X inactivated. Nature 394, 776–780 (1998)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Gartler, S. M. & Riggs, A. D. Mammalian X-chromosome inactivation. Annu. Rev. Genet. 17, 155–190 (1983)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Lyon, M. F. X-chromosome inactivation: a repeat hypothesis. Cytogenet. Cell Genet. 80, 133–137 (1998)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Bailey, J. A., Carrel, L., Chakravarti, A. & Eichler, E. E. Molecular evidence for a relationship between LINE-1 elements and X chromosome inactivation: the Lyon repeat hypothesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97, 6634–6639 (2000)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Smit, A. F., Toth, G., Riggs, A. D. & Jurka, J. Ancestral, mammalian-wide subfamilies of LINE-1 repetitive sequences. J. Mol. Biol. 246, 401–417 (1995)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Ke, X. & Collins, A. CpG islands in human X-inactivation. Ann. Hum. Genet. 67, 242–249 (2003)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Coffey, A. J. et al. Host response to EBV infection in X-linked lymphoproliferative disease results from mutations in an SH2-domain encoding gene. Nature Genet. 20, 129–135 (1998)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Stromme, P. et al. Mutations in the human ortholog of Aristaless cause X-linked mental retardation and epilepsy. Nature Genet. 30, 441–445 (2002)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Amir, R. E. et al. Rett syndrome is caused by mutations in X-linked MECP2, encoding methyl-CpG-binding protein 2. Nature Genet. 23, 185–188 (1999)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Orrico, A. et al. MECP2 mutation in male patients with non-specific X-linked mental retardation. FEBS Lett. 481, 285–288 (2000)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Ropers, H. H. et al. Nonsyndromic X-linked mental retardation: where are the missing mutations? Trends Genet. 19, 316–320 (2003)

Article CAS Google Scholar - The International Human Genome Mapping Consortium. A physical map of the human genome. Nature 409, 934–941 (2001)

Article Google Scholar - Ning, Z., Cox, A. J. & Mullikin, J. C. SSAHA: a fast search method for large DNA databases. Genome Res. 11, 1725–1729 (2001)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Brudno, M. et al. LAGAN and Multi-LAGAN: efficient tools for large-scale multiple alignment of genomic DNA. Genome Res. 13, 721–731 (2003)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Frazer, K. A., Pachter, L., Poliakov, A., Rubin, E. M. & Dubchak, I. VISTA: computational tools for comparative genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, W273–W279 (2004)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Bourque, G. & Pevzner, P. A. Genome-scale evolution: reconstructing gene orders in the ancestral species. Genome Res. 12, 26–36 (2002)

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Francke, U. Digitized and differentially shaded human chromosome ideograms for genomic applications. Cytogenet. Cell Genet. 65, 206–218 (1994)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Gibbs, R. A. et al. Genome sequence of the Brown Norway rat yields insights into mammalian evolution. Nature 428, 493–521 (2004)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Iwase, M. et al. The amelogenin loci span an ancient pseudoautosomal boundary in diverse mammalian species. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 5258–5263 (2003)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Lahn, B. T. & Page, D. C. A human sex-chromosomal gene family expressed in male germ cells and encoding variably charged proteins. Hum. Mol. Genet. 9, 311–319 (2000)

Article CAS Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

We thank the Washington University Genome Sequencing Center for access to chicken and chimpanzee genome sequence data before publication; the Broad Institute for access to dog and chimpanzee genome sequence data before publication, for T. nigroviridis genome data, and for fosmid end-sequence data and clones; members of the Sanger Institute zebrafish genome project; the mouse, rat and F. rubripes sequencing consortia; Genoscope for T. nigroviridis genome data; the Ensembl, UCSC, EMBL and GenBank database groups; G. Schuler for information on sequence overlaps; T. Furey for information on RefSeq RNA coverage; D. Jaffe for data on fosmid end-sequence matches; D. Vetrie, E. Kendall, D. Stephan, J. Trent, A. P. Monaco, J. Chelly, D. Thiselton, A. Hardcastle, G. Rappold and the Resource Centre of the German Human Genome Project (RZPD) for the provision of clones and mapping data; the HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee (S. Povey (chair), M. W. Wright, M. J. Lush, R. C. Lovering, V. K. Khodiyar, H. M. Wain and C. C. Talbot Jr) for assigning official gene symbols; C. Rees for assistance with the manuscript; C. Tyler-Smith for critical reading of the manuscript; and the Wellcome Trust, the NHGRI, and the Ministry of Education and Research (Germany) for financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Wellcome Trust Genome Campus, Hinxton, CB10 1SA, Cambridge, UK

Mark T. Ross, Darren V. Grafham, Alison J. Coffey, Kirsten McLay, Gareth R. Howell, Christine Burrows, Christine P. Bird, Adam Frankish, Frances L. Lovell, Kevin L. Howe, Jennifer L. Ashurst, Matthew C. Jones, Matthew E. Hurles, T. Daniel Andrews, Carol E. Scott, Stephen Searle, Adam Whittaker, Rebecca Deadman, Nigel P. Carter, Sarah E. Hunt, Rachael Ainscough, Kerrie D. Ambrose, Robert I. S. Ashwell, Anne K. Babbage, Claire L. Bagguley, Ruby Banerjee, Gary E. Barker, Karen F. Barlow, Ian P. Barrett, Karen N. Bates, David M. Beare, Helen Beasley, Oliver Beasley, Graeme Bethel, Nicola Brady, Sarah Bray-Allen, Anne M. Bridgeman, Andrew J. Brown, Deborah Burford, Joanne Burgess, Wayne Burrill, John Burton, Jackie M. Bye, Carol Carder, Joanne C. Chapman, Sue Y. Clark, Graham Clarke, Chris M. Clee, Sheila Clegg, Karen Clifford, Vicky Cobley, Charlotte G. Cole, Jen S. Conquer, Nicole Corby, Richard E. Connor, Joy Davies, John Davis, Pawandeep Dhami, Steve Dodsworth, Andrew Dunham, Matthew Dunn, Ireena Dutta, Tamsin Eades, Matthew Ellwood, Helen Errington, Louisa Faulkner, John Frankland, Audrey E. Fraser, James Gilbert, Simon G. Gregory, Susan Gribble, Coline Griffiths, Russell Grocock, Rhian Gwilliam, Elizabeth A. Hart, Paul D. Heath, Sarah Ho, Michael Hoffs, Phillip J. Howden, Elizabeth J. Huckle, Paul J. Hunt, Adrienne R. Hunt, Judith Isherwood, David Johnson, Shirin S. Joseph, Stephen Keenan, Joanne K. Kershaw, Andrew J. Knights, Gavin K. Laird, Cordelia Langford, Stephanie Lawlor, Margaret Leversha, Christine Lloyd, David M. Lloyd, Jane E. Loveland, Jamieson D. Lovell, Rachael Lyne, Lucy H. Matthews, Jennifer McDowall, Stuart McLaren, Amanda McMurray, Patrick Meidl, Sarah Milne, Shailesh L. Mistry, Christopher N. O'Dell, Sophie Palmer, Richard Pandian, Dina Patel, Alex V. Pearce, Danita M. Pearson, Sarah E. Pelan, Keith M. Porter, Yvonne Ramsey, Susan Rhodes, Kerry A. Ridler, Harminder K. Sehra, Charles Shaw-Smith, Elizabeth M. Sheridan, Ratna Shownkeen, Carl D. Skuce, Michelle L. Smith, Elizabeth C. Sotheran, Helen E. Steingruber, Charles A. Steward, Roy Storey, R. Mark Swann, David Swarbreck, Karen Thomas, Andrea Thorpe, Alan Tracey, Steve Trevanion, Anthony C. Tromans, Melanie Wall, Georgina L. Warry, Anthony West, Siobhan L. Whitehead, Mathew N. Whiteley, Jane E. Wilkinson, David L. Willey, Leanne Williams, Helen Williamson, Laurens Wilming, Rebecca L. Woodmansey, Paul W. Wray, David Buck, Catherine M. Rice, Mark Vaudin, Alan Coulson, John E. Sulston, Richard Durbin, Tim Hubbard, Stephan Beck, Jane Rogers & David R. Bentley - Baylor College of Medicine Human Genome Sequencing Center, Department of Molecular and Human Genetics, One Baylor Plaza, Houston, Texas, 77030, USA

Steven Scherer, Donna Muzny, Rui Chen, Andrew Cree, Preethi Gunaratne, Paul Havlak, Anne Hodgson, Michael L. Metzker, Stephen Richards, Graham Scott, David Steffen, Erica Sodergren, David A. Wheeler, Kim C. Worley, M. Ali Ansari-Lari, Swaroop Aradhya, Andrea Ballabio, Mary J. Brown, David Bonnin, Christian Buhay, Paula Burch, Joseph Chako, Dean Chavez, Guan Chen, Zhijian Chen, Craig Chinault, Kerstin Clerc-Blankenburg, Robert David, Clay Davis, Oliver Delgado, Denise DeShazo, Yan Ding, Huyen Dinh, Heather Draper, Shannon Dugan-Rocha, K. James Durbin, Alexandra Emery-Cohen, Rachel Gill, Yanghong Gu, Cerissa Hamilton, Alicia Hawes, Judith Hernandez, Jennifer Hume, Leni Jacob, Sally Jones, Susan Kelly, Ziad Khan, Christie Kovar-Smith, Lora Lewis, Wen Liu, Hermela Loulseged, Ryan Lozado, Jing Lu, Jie Ma, Manjula Maheshwari, George Miner, Margaret Morgan, Sidney Morris, Ngoc Nguyen, Geoffery Okwuonu, David Parker, Julia Parrish, Shiran Pasternak, Lesette Perez, Hua Shen, Paul E. Tabor, Tineace Taylor, Brian Teague, Kirsten Timms, Daniel Verduzco, Donna Villasana, Lenee Waldron, Qiaoyan Wang, James Warren, Xuehong Wei, Gabrielle Williams, Angela Williamson, Jennifer Yen, Jingkun Zhang, Jianling Zhou, Huda Zoghbi, Sara Zorilla, David L. Nelson, George Weinstock & Richard A. Gibbs - Genomanalyse, Institut für Molekulare Biotechnologie, Beutenbergstr. 11, 07745, Jena, Germany

Matthias Platzer, Gaiping Wen, Karin Blechschmidt, Petra Galgoczy, Gernot Glöckner, Bernd Hinzmann, Gabriele Nordsiek, Gerald Nyakatura, Kathrin Reichwald, Stefan Taudien & André Rosenthal - Washington University Genome Sequencing Center, Box 8501, 4444 Forest Park Avenue, St. Louis, Missouri, 63108, USA

Robert S. Fulton, Patrick J. Minx, LaDeana W. Hillier, Richard K. Wilson & Robert H. Waterston - Max Planck Institute for Molecular Genetics, Ihnestrasse 73, 14195, Berlin, Germany

Ralf Sudbrak, Alfred Beck, Katja Heitmann, Steffen Hennig, Sven Klages, Anna Kosiura, Ines Müller, Richard Reinhardt & Hans Lehrach - Institute for Clinical Molecular Biology, Christian-Albrechts-University, 24105, Kiel, Germany

Ralf Sudbrak - Medizinische Genetik, Ludwig-Maximilian-Universität, Goethestr. 29, 80336, München, Germany

Juliane Ramser & Alfons Meindl - HUGO Gene Nomenclature Committee, The Galton Laboratory, Department of Biology, University College London, Wolfson House, 4 Stephenson Way, NW1 2HE, London, UK

Elspeth A. Bruford - Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Pennsylvania State College of Medicine, Hershey, Pennsylvania, 17033, USA

Laura Carrel - Advanced Center for Genetic Technology, PE-Applied Biosystems, Foster City, California, 94404, USA

Ellson Chen - European Bioinformatics Institute, Wellcome Trust Genome Campus, Hinxton, CB10 1SD, Cambridge, UK

Yuan Chen - Institute of Genetics and Biophysics, Adriano Buzzati-Traverso, Via Marconi 12, 80100, Naples, Italy

Alfredo Ciccodicola & Michele d'Urso - Medical Genetics Section, University of Edinburgh, Western General Hospital, EH4 2XU, Edinburgh, UK