The sequence and de novo assembly of the giant panda genome (original) (raw)

Abstract

Using next-generation sequencing technology alone, we have successfully generated and assembled a draft sequence of the giant panda genome. The assembled contigs (2.25 gigabases (Gb)) cover approximately 94% of the whole genome, and the remaining gaps (0.05 Gb) seem to contain carnivore-specific repeats and tandem repeats. Comparisons with the dog and human showed that the panda genome has a lower divergence rate. The assessment of panda genes potentially underlying some of its unique traits indicated that its bamboo diet might be more dependent on its gut microbiome than its own genetic composition. We also identified more than 2.7 million heterozygous single nucleotide polymorphisms in the diploid genome. Our data and analyses provide a foundation for promoting mammalian genetic research, and demonstrate the feasibility for using next-generation sequencing technologies for accurate, cost-effective and rapid de novo assembly of large eukaryotic genomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The giant panda, Ailuropoda melanoleura, is at high risk of extinction because of human population expansion and destruction of its habitat. The latest molecular census of its population size, using faecal samples and nine microsatellite loci, provided an estimate of only 2,500–3,000 individuals, which were confined to several small mountain habitats in Western China1. The giant panda has several unusual biological and behavioural traits, including a famously restricted diet, primarily made up of bamboo, and a very low fecundity rate. Moreover, the panda holds a unique place in evolution, and there has been continuing controversy about its phylogenetic position2. At present, there is very little genetic information for the panda, which is an essential tool for detailed understanding of the biology of this organism.

A major limitation in obtaining extensive genetic data is the prohibitive costs associated with sequencing and assembling large eukaryotic genomes. The development of next-generation massively parallel sequencing technologies, including the Roche/454 Genome Sequencer FLX Instrument, the ABI SOLiD System, and the Illumina Genome Analyser, has significantly improved sequencing throughput, reduced costs, and advanced research in many areas, including large-scale resequencing of human genomes3,4, transcriptome sequencing, messenger RNA and microRNA expression profiling, and DNA methylation studies. However, the read length of these sequencing technologies, which is much shorter than that of traditional capillary Sanger sequencing reads, has prevented its use as the sole sequencing technology in de novo assembly of large eukaryotic genomes.

Here, using only Illumina Genome Analyser sequencing technology, we have generated and assembled a draft genome sequence for the giant panda with an assembled N50 contig size (defined in Table 1) reaching 40 kilobases (kb), and an N50 scaffold size of 1.3 megabases (Mb). This represents the first, to our knowledge, fully sequenced genome of the family Ursidae and the second of the order Carnivora5. We also carried out several analyses using the complete sequence data, including genome content, evolutionary analyses, and investigation of some of the genetic features underlying the panda’s unique biology. The work presented here should aid in understanding and carrying out further research on the genetic basis of panda’s biology, and contribute to disease control and conservation efforts for this endangered species. Furthermore, our demonstration that next-generation sequencing technology can allow accurate de novo assembly of the giant panda genome will have far-reaching implications for promoting the construction of reference sequences for other animal and plant genomes in an efficient and cost-effective way.

Table 1 Summary of the panda genome sequencing and assembly

Short-read de novo sequencing and assembly

For sequencing, we selected a 3-year-old female giant panda from the Chengdu breeding centre in China. The panda genome contains 20 pairs of autosomes and one pair of sex chromosomes (2_n =_ 42) (Supplementary Fig. 1). We used a whole-genome shotgun sequencing strategy and Illumina Genome Analyser sequencing technology. DNA was extracted from the peripheral venous blood, and 37 paired-end sequencing libraries were constructed with insert sizes of about 150 base pairs (bp), 500 bp, 2 kb, 5 kb and 10 kb. In total, we generated 176-Gb of usable sequence (equal to 73-fold coverage of the whole genome), with an average read length of 52 bp (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2).

We assembled the short reads using SOAPdenovo (http://soap.genomics.org.cn)—a genome assembler developed specifically for use with next-generation short-read sequences6 (Supplementary Fig. 2). SOAPdenovo uses the de Bruijn graph algorithm7 and applies a stepwise strategy to make it feasible to assemble the panda genome using a supercomputer (32 cores and 512 Gb random access memory (RAM)). The algorithm is sensitive to sequencing errors, so we excluded the data generated from poor libraries, filtered low-quality reads, and used the 134 Gb (56-fold coverage) high-quality reads for de novo assembly.

We first assembled the short reads from fragmented small insert-size libraries (<500 bp) into contigs using sequence overlap information. Contigs were not extended into regions in which repeat sequences created ambiguous connections. At this point, we assembled about 39-fold coverage short-reads into contigs having an N50 length of 1.5 kb, achieving a total length of 2.0 Gb (Table 1). Here, we avoided using reads from long insert-size paired-end libraries (≥2 kb) on contig assembly because these libraries were constructed using a circularization and random fragmentation method4, and the small fraction (∼5%) of chimaeric reads in these long insert-size libraries could generate incorrect sequence overlap resulting in misassembly.

We then used the paired-end information, step by step from the shortest (150 bp) to the longest (10 kb) insert size, to join the contigs into scaffolds. We obtained a scaffold N50 length of 1.3 Mb and a total length of 2.3 Gb, determined by counting the estimated intra-scaffold gaps. Most of the remaining gaps probably occur in repetitive regions, so we further gathered the paired-end reads with one end mapped on the unique contig and the other end located in the gap region and performed local assembly with the unmapped end to fill in the small gaps within the scaffolds. The resulting assembly had a final contig N50 length of 40 kb (Table 1). In total, 223.7 Mb gaps were closed. Roughly 54.2 Mb (2.4% of total scaffold sequence) remained unclosed, of which we determined that about 90% contained carnivore-specific transposable elements and the remainder were primarily tandem repeats with high unit identity and lengths larger than the sequencing read length, which could not be assembled with the current data. About 0.05% of the panda assembly was composed of tandem repeats (Supplementary Table 3). Given the genome similarity between the panda and the dog, and that 0.2% of the dog genome is made up of tandem repeats, we estimate that around 3.6 Mb (0.15%) of tandem repeat sequences might be missing in the current panda genome assembly.

To evaluate the single-base accuracy of the assembled genome sequence, we realigned all the usable sequencing reads onto the scaffolds using SOAPaligner8. The peak sequencing depth was 65×, and more than 20 reads covered over 99% of the assembled sequences (Fig. 1a). Using massively parallel next-generation sequencing technology and improving sequencing depth to more than 20× coverage provides a very high single-base accuracy3,9.

Figure 1: Assessment of assembly quality.

a, Distribution of sequencing depth of the assembled genome. b, Comparison of the assembled genome with a BAC sequence. Read depth on the BAC was calculated by mapping the Illumina Genome Analyser short reads onto the BAC sequence. The predicted gene and annotated transposable elements (TEs) on the BAC sequence are shown in green and red, respectively. The remaining unclosed gaps on the scaffolds are marked as white blocks.

The GC content difference is a primary factor for non-random sequencing-depth distribution4. Using 500-bp non-overlapping sliding windows along the genome, which is similar to the size of sequencing DNA fragments (150–500 bp), we found that both very low and very high GC regions had a relatively lower sequencing depth, but nearly all regions with a GC content between 20% and 80% had more than 20× coverage, which is sufficient for de novo assembly (Supplementary Fig. 3). Only a minor fraction (0.004%) of the panda genome—as compared to the sequenced dog (0.079%), human (0.095%) and mouse (0.015%) genomes—had a GC content lower than 20% or higher than 80% (Supplementary Fig. 4). Assuming similar GC content in the panda and dog genomes, 0.075% (1.8 Mb) sequence with extreme GC content could be missing in the current panda assembly. Nevertheless, the analysis showed that de novo genome assembly is unlikely to be strongly affected by GC-biased non-random sampling.

There are 27 known panda mRNA genes in GenBank, one of which is the SRY sex determination gene located on chromosome Y, thus not present in the female panda. We were able to detect the remaining 26 genes in the assembled scaffolds with 99.3% total sequence aligned (Supplementary Table 4). All of these genes, with the exception of the ribosomal gene RPS15, were intact on the scaffolds. For RPS15, we found one fragment in the scaffolds and the other in a small contig not incorporated in the scaffolds. These data indicate that the genome assembly has good coverage and completeness for genes with unique sequences, but given their nature, multiple-copy genes or genes containing repetitive sequences may be fragmented.

To assess the large-scale and local assembly accuracy of the scaffolds, we sequenced and assembled nine bacterial artificial chromosomes (BACs) independently using Sanger sequencing technology10. Each BAC (average length 97.7 kb) was aligned to only one scaffold, and up to 98.0% of the total BAC regions were well covered by the assembled contigs. We did not observe any obvious misassembly errors (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 5). We then checked the single-base mismatch or small insertion/deletion differences. After excluding the annotated heterozygous single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and indels (described later), the rate of single-base differences was 0.07% and the average number of insertions/deletions on each BAC was 16 (Supplementary Table 5 and Supplementary Fig. 6). There was both a very high read depth on the scaffolds and a high Phred score on the BACs at the discrepant bases, so most of these might be unidentified heterozygous SNPs. Manual inspection showed that 38% of the insertions/deletions were caused by assembly errors on the BAC (Supplementary Fig. 7a), and the rest were unidentified heterozygous indels of the diploid genome (Supplementary Fig. 7b).

To assess genome coverage of the assembled contigs and scaffolds, we first estimated the genome size of the panda. To obtain the best estimate, we used sequencing depth, size ratio of syntenic blocks, and comparison of C-values. Using 17-base oligonucleotides and their frequency distribution in the usable sequencing reads to determine sequencing depth11, we obtained an estimated panda genome size of 2.46 Gb (Supplementary Fig. 8). Given the presence of sequencing errors, we expect that the sequencing depth is underestimated, and consequently the panda genome size should be slightly smaller than 2.46 Gb.

Given the evolutionary relationship of the panda with the dog and the bear, we used their genome size information to refine our estimate of the panda genome size. For the whole genome, the size ratio of conserved syntenic blocks between the panda and the dog genomes is 0.978. As the current estimated size of the dog genome is 2.45 Gb5, we estimated the panda genome size to be 2.40 Gb. Genome sequence and size information for the bear is unavailable. We therefore used C-values (haploid DNA content in picograms), as this is proportional to genome size. The recorded C-value is 2.80 for the dog and 2.75 for two bears, Ursus arctos and Ursus hibetanus (http://www.genomesize.com/), indicating that the genome size of bears should be smaller than that of the dog. On the basis of previous reports showing that the karyotype of panda is similar to that of bears12, the bear and the panda are expected to have similar genome sizes. We again determined the panda genome size to be 2.40 Gb. Using this genome size, the assembled contigs and scaffolds should cover about 94% and 96% of the whole genome, respectively.

Panda, dog and human repeat comparison

Combining results from analyses using the Repbase library13, alignment with known transposable-element-related genes, and de novo RepeatModeller[14](/articles/nature08696#ref-CR14 "Smit, A. F. A., Hubley, R. & Green, P. RepeatMasker at 〈 http://www.RepeatMasker.org

〉.") identification, we estimate that transposable elements comprised approximately 36.2% of the panda genome, which is similar to that of the dog genome (36.1%), and lower than the human genome (46.1%) (see [Supplementary Tables 6 and 7](/articles/nature08696#MOESM303)). Analysis of the divergence rate of the transposable element in the panda genome using Repbase transposable-element libraries showed that nearly all of the identified panda transposable-element copies had a >10% divergence rate from the consensus. This high divergence rate may be related to the fact that the Repbase transposable-element consensus sequences were annotated using mammalian genomes other than the panda. Using RepeatModeller transposable elements, we found that about 70 Mb of transposable-element sequences (3% of the genome) had a <10% divergence rate from the consensus ([Supplementary Fig. 9](/articles/nature08696#MOESM303)), which are likely to be active transposable elements of recent origin. (See [Supplementary Results](/articles/nature08696#MOESM303) for further analyses on specific transposable elements.)Panda genome has a low divergence rate

To investigate the rate of recent segmental duplication (>90% identity, >1 kb length) in the panda genome, we conducted self-sequence alignment and identified 3,095 duplicated fragments with a total length 10.4 Mb (0.43%) in the whole genome assembly. To determine whether these highly similar recent duplicates were collapsed by the assembly, we aligned all sequencing reads to the assembled genome, and identified 5,485 segments (>1 kb in length) with a total length of 13.9 Mb that had an obviously higher read depth than the other genomic regions. Considering the average depth was about 2.47 times that of the whole genome, we estimated that the total length of the duplicated copies was about 34.3 Mb (1.43% of the whole genome) (Supplementary Table 8). Integrating the results of the two methods, we estimated that recent segmental duplication comprised about 43.7 Mb (1.82%) of the panda genome, which is lower than the rate in the dog genome (106.6 Mb, 4.21%)15.

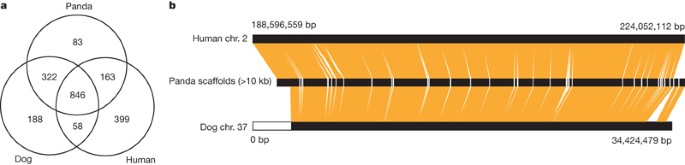

To investigate panda genome conservation and evolution, we performed whole-genome alignment with the panda, dog and human genomes. Each of these genomes contained ∼1.4 Gb of non-repetitive sequence, of which 846 Mb of sequence was shared by all three genomes. Of the remainder, 322 Mb of sequence was shared between panda and dog, which was much higher than that between panda and human (163 Mb) or between dog and human (58 Mb). The panda had the lowest amount of lineage-specific sequences, indicating that it has the lowest divergence rate among the three genomes (Fig. 2a).

Figure 2: Conserved sequences among the panda, dog and human genomes.

a, The total lengths of aligned and unaligned non-repetitive sequences. Each of the three genomes contains 1.4 Gb of non-repetitive sequences. Pairwise whole-genome alignment was performed using Blastz. The lengths shown are in Mb. b, Syntenic view of the dog chromosome 37, 35 panda scaffolds (>10 kb), and the human chromosome 2. Note that the 3 Mb region at the end of dog chromosome 37 was unanchored.

We found that the panda, dog and human genomes had high genomic synteny. For example, the syntenic relationship of 35 panda scaffolds, 36.5 Mb of human chromosome 2, and dog chromosome 37 (Fig. 2b) showed no large-scale rearrangement within the chromosomal region. For the whole genome, regions of conserved synteny between the panda and dog genomes covered 2.22 Gb (96.7%) and 2.27 Gb (92.9%), respectively; and the pairwise syntenic regions between the panda and human genomes covered 2.19 Gb (95.3%) and 2.66 Gb (88.1%), respectively (Supplementary Table 9).

We further detected genomic rearrangement events using the whole genome alignments. Here, we used 3,805 panda scaffolds with lengths longer than 10 kb, which covered 98.6% of the assembled genome. To define rearrangements, we used different cutoffs for minimum syntenic segments. The total intra-chromosomal breakpoints between the panda and the dog genomes varied from 468 with a 5-kb cutoff to 20 with a 100-kb cutoff. We also identified about 42 inter-chromosomal rearrangements using a 100-kb cutoff (Supplementary Table 10). We used the human genome as the common outgroup and found that there were 4–5 times more rearrangements in dog than in panda, which provided evidence that the panda has a lower divergence rate than the dog.

Gene prediction and comparison

To predict the number of genes in the panda genome, we used both evidence-based and ab inito methods. We aligned 20,001 (94%) of the human and 19,086 (99%) of the dog genes to the panda genome and predicted 19,303 and 19,245 gene loci, respectively (see Methods and Supplementary Table 11). We also used Genscan16 and Augustus17 with model parameters trained on the human, and predicted 44,428 and 29,238 gene loci, respectively for the two programs, in the panda genome. To facilitate further analysis, we integrated all the gene sources and created a reference gene set that contained 21,001 genes for the panda (Supplementary Table 12).

To measure the quality of gene prediction, we compared the length distribution of genes, coding sequences (CDS), exons and introns, and the distribution of exon number per gene among representative mammalian genomes, including panda, dog, human, mouse and opossum. The panda was similar to the human with respect to all of these key parameters (Supplementary Fig. 10). To evaluate the rate of missing exons in the predicted genes, we aligned both the panda and dog genes to the human genes and calculated the percentage of human gene sequences covered. On average, the dog and panda genes covered 96.2% and 93.5% of the human gene sequences, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 11a). Further checking showed that most (more than 80%) of the unannotated exons were at the 5′ or 3′ ends of genes; these exons were usually very small and separated by large introns that were hard to predict by gene finders, although they were correctly presented in the assembled scaffolds (Supplementary Fig. 11b). There are 626 genes, with predicted functions in defence/immunity, receptors and signalling, located in the segmental duplication regions, which was similar to the findings in a previous analysis of the dog genome15 (Supplementary Table 13). Overall, we found that the quality of the predicted panda genes was comparable to that of other well-annotated mammalian genomes.

We next used InParanoid and Multiparanoid18 to identify gene orthologues among panda, dog, mouse and human. In total, we found 18,643 orthologous clusters that were shared by at least two species, and 15,060 clusters that were shared by all four species (Supplementary Fig. 12). There were 2,534 panda-specific genes, which is nearly double the amount of dog-specific genes (1,677). This difference might be due to the fact that only an evidence-based method was used for dog gene prediction and a smaller number of genes was predicted in the dog genome (19,305)5.

Gene gains and losses are one of the primary contributors to functional changes19. To obtain greater insight into the evolutionary dynamics of the genes, we determined the expansion and contraction of the gene orthologue clusters among these four species. We used a maximum-likelihood method to estimate the orthologue cluster sizes in their common ancestor20, and then defined the expansion and contraction by comparing the cluster size differences between the ancestor and each of the current species. Overall in all four genomes, we found a greater amount of gene contraction than expansion (Fig. 3), indicating that loss-of-function might have an important role in functional evolution. We also saw that the clusters within different species that underwent the most marked changes (expansion or contraction) were those involved in receptor activity (Supplementary Table 14).

Figure 3: Dynamic evolution of orthologous gene clusters.

The estimated numbers of orthologue groups in the common ancestral species are shown on the internal nodes. The numbers of orthologous groups that expanded or contracted in each lineage after speciation are shown on the corresponding branch, with ‘+’ referring to expansion and ‘-’ referring to contraction.

We looked for signatures of positive selection using branch-site likelihood ratio tests21 for 12,424 genes of high confidence that had 1:1 orthologues in the panda and human genome and in at least one of the rat, mouse and dog genomes that had passed a series of rigorous filters for large-scale synteny, alignment quality, conservation of exon–intron structure, and sequence quality22. Using three different tests—one specific for the panda lineage, one specific for the dog lineage, and one combining evidence from all five species included in the alignment—we found 134, 94 and 182 positively selected genes (PSGs), respectively, using a conservative 5% false-discovery-rate criterion.

The panda and the dog lineage only share six PSGs. However, Fisher’s exact and Mann–Whitney U tests showed enrichment of several immunity- and defence-related functional categories in both the panda and the dog genomes, which is consistent with the results from previous genome-wide positive selection scans in mammalian genomes23 (Supplementary Table 15). Gene Ontology classification showed that panda PSGs spanned a diverse range of immune response systems, in particular acute inflammatory and innate immune response, as well as response to wounding (Supplementary Table 16).

Of note, the inclusion of the panda genome in the multiple species analysis showed an enrichment of two new Gene Ontology categories ‘blood circulation and gas exchange activity’ and ‘haemostasis’ as compared to an analysis with six mammalian species23 (human, chimpanzee, macaque, mouse, rat and dog). In contrast to the various enrichments for Gene Ontology categories for the panda PSGs, only two categories, ‘cytolysis’ and ‘cell–cell adhesions’, were over-represented in the dog PSGs. The latter category includes cadherins (for example, PCDHB10 (P = 2.66 × 10-32), PCDHB8 (P = 1.80 × 10-19), PCDHB17 (P = 3.74 × 10-10) and ME1 (P = 7.10 × 10-9)).

Panda-specific characteristics

To gain insight into some of the traits unique to the panda, we investigated genes that may influence characteristics such as panda diet and fecundity. For our investigation of genes that may be involved in food selection and digestion, we identified genes that encode digestive enzymes protease, amylase, lipase, cellulase, lactase, invertase and maltase in the panda genome, indicating that the panda probably has all the necessary components for a carnivorous digestive system. We did not find any homologues of digestive cellulase genes, including endoglucanase, exoglucanase and beta-glucosidase, indicating that the bamboo diet of the panda is unlikely to be dictated by its own genetic composition, and may instead be more dependent on its gut microbiome.

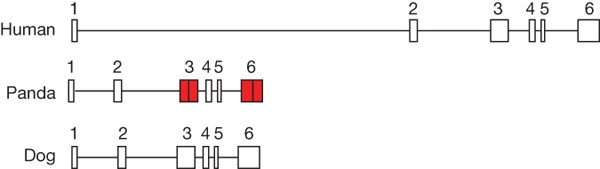

Taste is also an important factor in the development of dietary habits. The five components of basic taste are: sweetness, saltiness, sourness, bitterness and umami. Bitterness is sensed by the T2R gene family24, and we identified 16 T2R genes in the panda genome, which is comparable to 14 T2R genes reported for the dog25. Umami is sensed through the T1R gene family26. In the panda genome, T1R2 and T1R3 are in an intact form, but T1R1 has become a pseudogene (Fig. 4)—we found that the two panda T1R1 exons contain frameshift errors, which we confirmed by Sanger sequencing. We also found that the _d_N/_d_S (the ratio of the rate of non-synonymous substitutions to the rate of synonymous substitutions) difference for this gene was low between the panda (0.17) and dog (0.13) lineage, indicating a recent death for this gene in the panda lineage (Supplementary Fig. 13). The T1R1/T1R3 heterodimer is known to be a receptor that senses umami27, and a previous study indicated that T1R1/T1R3 may be the sole receptor for umami taste28. Umami perception occurs through the detection of the carboxylate anion of glutamic acid, which is a naturally occurring amino acid common in meats, cheese, broth, stock and other protein-heavy foods. Thus, the loss-of-function of the T1R1 gene might prevent the panda from expressing a functional umami taste receptor, which may partly explain why the panda diet is primarily herbivorous despite its taxonomic classification as a carnivore.

Figure 4: Structure of the umami receptor T1R1 gene.

Two frameshift mutations occurred in the third and sixth exons (red) of the panda T1R1 gene. The third exon contained a 2-bp (‘GG’) insertion; the sixth exon contained a 4-bp (‘GTGT’) deletion.

The giant panda has a low fecundity rate, which is of great consequence given its endangered status. We identified nearly all of the reproduction genes known to be critical for mammalian gonad development and function. We identified a putative pseudo follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) β-subunit gene (giant panda-FSHB2), which has high sequence similarity to the giant panda FSH β-subunit gene (giant panda-FSHB1) in the panda genome as well as in several other mammalian species, including cow and horse (Supplementary Fig. 14). At this stage, whether the pseudo FSHB2 gene contributes to the reproductive features of the giant panda remains to be determined.

Panda has a high heterozygosity rate

As the panda population is estimated to be ∼2,500 wordwide at present1, the issue of genetic variability and evolutionary potential is extremely important because low genetic variability will cause a population decline. A recent molecular analysis of the 655 bp of the mitochondrial control region DNA and ten microsatellite loci indicated that the panda still has high genetic variability29. Sequence data for the whole genome to firmly establish this important issue have not been available until now.

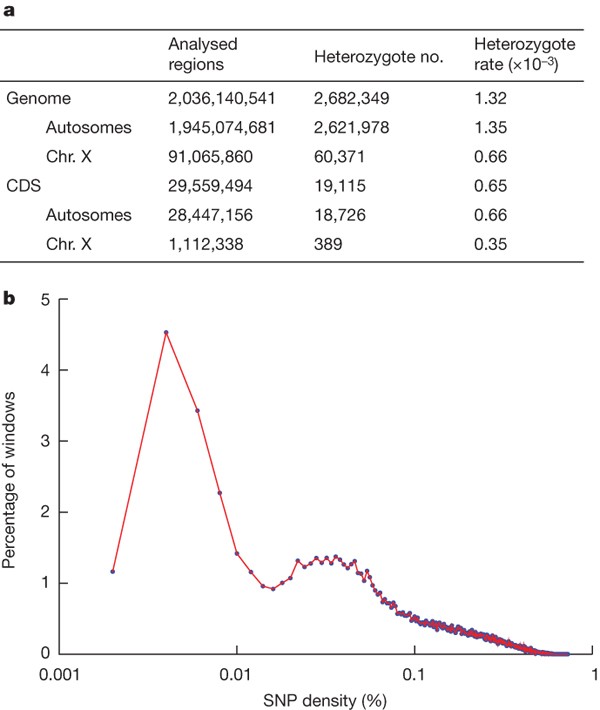

Using the assembled panda genome sequence as a reference, we realigned all of the usable sequencing reads with the genome to identify the heterozygous SNPs, small indels, and structural variations between the two sets of homologous chromosomes in the diploid genome. We were able to align about 85% of the usable sequencing reads. Among these, we used the 90% that had unique best locations to detect variation by applying the pipeline developed in the analysis of the first Asian human genome3,6,8 (Supplementary Table 17). We identified 2.7 million heterozygous SNPs in the panda diploid genome. The estimated heterozygosity rate of the autosomes was 1.35 × 10-3 for the whole genome and 0.66 × 10-3 for the coding regions (Fig. 5a). This is about 1.95 times higher than the rate estimated for the human genome (0.69 × 10-3 and 0.34 × 10-3)3. The heterozygosity rate in the X chromosome is about half that of the autosomes, and the ratio of transition/transversion is 2.1 (Supplementary Table 18). Our finding of a high heterozygosity rate may be due to the mixed genetic background (Liangshan and Minshan sub-populations) of the panda that we sequenced. These results, however, may indicate that the panda species still has high genetic variability, which would support the potential for its successful survival despite its small population size. To determine this, analyses of other panda genomes are required.

Figure 5: Panda heterozygous SNP density.

a, Statistics of identified heterozygous SNPs. Analysed regions are the genomic regions with proper unique read coverage that were used for heterozygote detection. The panda X-chromosome-derived scaffolds were identified by Blastz alignment to the dog X chromosome. b, Distribution of heterozygosity density in the panda diploid genome. Heterozygous SNPs between the two sets of chromosomes of the panda diploid genome were annotated, then non-overlapping 50-kb windows were chosen and heterozygosity density in each window was calculated.

The heterozygous SNP rate in the panda genome showed a bimodal distribution with one peak at 0.004% and another at 0.035% (Fig. 5b). The SNP rate of 14.9% of the genome regions was lower than 0.015%, and the SNP rate of the remaining regions was in range 0.015–0.6%. According to the Wright–Fisher population genetic model30, the effective population size is inversely proportional to the time to the most recent common ancestor (TMRCA), and TMRCA directly determines the heterozygosity, so this SNP distribution might indicate changes or bottlenecks of the effective population size in the panda population history.

In addition to SNPs, we identified 267,958 small indels that ranged in size from 1 to 6 bp (Supplementary Table 19). The estimated small indel rate was 1.22 × 10-4 and 0.70 × 10-4 on autosomes and sex chromosomes, respectively—roughly one order of magnitude lower than that of the SNP rate. We also identified insertions or deletions that were greater than 100 bp and inversion events. There were 4,359 insertions and deletions detected with a median length of 150 bp, and 20 inversions (Supplementary Table 20). More than 70% of the insertions or deletions overlapped transposable elements, and these were primarily made up of carnivore-specific LINE/L1 and SINE/Lys transposable elements. We expect that the amount of structural variation was underestimated because the genome assembly is still too fragmented to identify long structural variations.

Discussion

Comparative genomics is a powerful tool for determining the genetic basis of biological functions. Sequencing more mammalian genomes will undoubtedly facilitate our ability to annotate the human genome. So far, however, only a few mammals have had their complete genomes sequenced, and a great deal more data are necessary for carrying out more detailed mammalian comparative genomics. The primary limitations are related to the extreme cost and length of time needed to sequence and assemble very large genomes that would be suitable for such analyses.

Our ability to generate and assemble a draft sequence for an entire mammalian genome using only next-generation Illumina Genome Analyser short-read sequencing technology indicates that such technology can be used to generate many more mammalian genome draft sequences in a rapid and cost-effective manner. The assembled contigs and scaffolds of the panda genome were sufficiently long to allow us to carry out our gene prediction and comparative analyses, and our evaluation of the sequence quality showed that the panda genome sequence was of similar utility to sequences generated using traditional capillary-based Sanger sequencing. It should be noted that fewer active transposons and recent segmental duplications in the panda genome may have made it relatively easier to assemble than some other complex animal or plant genomes. Thus, the relative affect of these genomic features on de novo assembly from short reads will need to be assessed in the future in genomes that contain such features.

The panda genome is, to our knowledge, the first genome from the Ursidae lineage, and the second carnivore to be sequenced. Our comparative analysis showed that the panda had high genomic synteny with dog and human, but that there has been considerable divergence in the repetitive regions, most of which seems to result from recent transposable-element activity. Our comparison of the panda and other available mammalian genomes showed that most genes were conserved among all of these mammals, although we also identified several gene families that had expanded or contracted within each lineage. Of interest, our analysis of genes potentially involved in the evolution of the panda’s reliance on bamboo in its diet showed that the panda seems to have maintained the genetic requirements for being purely carnivorous even though its diet is primarily herbivorous. Furthermore, given our finding that some of the genes necessary for complete digestion of bamboo are missing from its genome, investigation of panda’s gut microbiome may be important for understanding its unusual dietary restrictions.

As well as providing a reference genome for use in future studies, we were also able to detect the most extensive heterozygous SNPs, indels and structural variation in the diploid genome, which will be important for ecological and population studies designed to address issues of panda survival.

Methods Summary

We constructed the paired-end DNA libraries with insert sizes larger than 2 kb by self-ligation of the DNA fragments and merging the two ends of the DNA fragment. We randomly fragmented the circularized DNA and enriched the fragments crossing the merged boundaries using magnetic beads with biotin and streptavidin. The sequencing process followed the manufacturer’s instructions (Illumina), and the fluorescent images were processed to sequences using the Illumina data processing pipeline (v1.1).

The genome sequence was assembled with short reads using SOAPdenovo software6 (http://soap.genomics.org.cn), which adopts the de Bruijn graph data structure to construct contigs7. The reads were then realigned to the contig sequence, and the paired-end relationship between the reads was transferred to linkage between contigs. We constructed scaffolds starting with short paired-ends and then iterated the scaffolding process, step by step, using longer insert size paired-ends. To fill the intra-scaffold gaps, we used the paired-end information to retrieve read pairs that had one read well-aligned on the contigs and another read located in the gap region, then did a local assembly for the collected reads.

Known transposable elements were identified using RepeatMasker (version 3.2.6)[14](/articles/nature08696#ref-CR14 "Smit, A. F. A., Hubley, R. & Green, P. RepeatMasker at 〈 http://www.RepeatMasker.org

〉.") against the Repbase[31](/articles/nature08696#ref-CR31 "Jurka, J. et al. Repbase Update, a database of eukaryotic repetitive elements. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 110, 462–467 (2005)") transposable element library (version 2008-08-01), and highly diverged transposable elements were identified with RepeatProteinMask[14](/articles/nature08696#ref-CR14 "Smit, A. F. A., Hubley, R. & Green, P. RepeatMasker at 〈

http://www.RepeatMasker.org

〉.") by aligning the genome sequence to the curated transposable-element-related proteins. A _de novo_ panda repeat library was constructed using RepeatModeller[14](/articles/nature08696#ref-CR14 "Smit, A. F. A., Hubley, R. & Green, P. RepeatMasker at 〈

http://www.RepeatMasker.org

〉."). Using evidence-based gene prediction, the human and dog genes (Ensembl release 52) were projected onto the panda genome, and the gene loci were defined by using both sequence similarity and whole-genome synteny information. _De novo_ gene prediction was performed using Genscan[16](/articles/nature08696#ref-CR16 "Salamov, A. A. & Solovyev, V. V. Ab initio gene finding in Drosophila genomic DNA. Genome Res. 10, 516–522 (2000)") and Augustus[17](/articles/nature08696#ref-CR17 "Stanke, M. & Waack, S. Gene prediction with a hidden Markov model and a new intron submodel. Bioinformatics 19 (suppl. 2). ii215–ii225 (2003)"). A reference gene set was created by merging all of the gene sets. The sequencing reads were mapped on the panda genome sequence using SOAPaligner[8](/articles/nature08696#ref-CR8 "Li, R., Li, Y., Kristiansen, K. & Wang, J. SOAP: short oligonucleotide alignment program. Bioinformatics 24, 713–714 (2008)"), and heterozygous SNPs were identified by SOAPsnp[9](/articles/nature08696#ref-CR9 "Li, R. et al. SNP detection for massively parallel whole-genome resequencing. Genome Res. 19, 1124–1132 (2009)").Accession codes

Data deposits

This Whole Genome Shotgun project has been deposited at DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under the accession ACTA00000000. The version described in this paper is the first version ACTA01000000. The reads data have been deposited in the EBI/NCBI Short Read Archive under the accession SRA009203. All panda data have been released for public use and can be freely accessed at BGI official website: http://panda.genomics.org.cn/download.jsp. The entire dataset includes all usable reads, genome assembly, annotation of genes, repeat and non-coding RNA, as well as heterozygous SNP, indel and structural variation information.

References

- Zhan, X. et al. Molecular censusing doubles giant panda population estimate in a key nature reserve. Curr. Biol. 16, R451–R452 (2006)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Krause, J. et al. Mitochondrial genomes reveal an explosive radiation of extinct and extant bears near the Miocene-Pliocene boundary. BMC Evol. Biol. 8, 220 (2008)

Article Google Scholar - Wang, J. et al. The diploid genome sequence of an Asian individual. Nature 456, 60–65 (2008)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Bentley, D. R. et al. Accurate whole human genome sequencing using reversible terminator chemistry. Nature 456, 53–59 (2008)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Lindblad-Toh, K. et al. Genome sequence, comparative analysis and haplotype structure of the domestic dog. Nature 438, 803–819 (2005)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Li, R., Zhu, H. & Wang, J. De novo assembly of human genomes with massively parallel short read sequencing. Genome Res. 10.1101/gr.097261.109 (in the press)

- Pevzner, P. A., Tang, H. & Waterman, M. S. An Eulerian path approach to DNA fragment assembly. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 9748–9753 (2001)

Article ADS MathSciNet CAS Google Scholar - Li, R., Li, Y., Kristiansen, K. & Wang, J. SOAP: short oligonucleotide alignment program. Bioinformatics 24, 713–714 (2008)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Li, R. et al. SNP detection for massively parallel whole-genome resequencing. Genome Res. 19, 1124–1132 (2009)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Zheng, Y. et al. Sequencing, annotation and comparative analysis of nine BACs of giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca). Sci. China C Life Sci. 10.1007/s11427-010-0001-z (in the press)

- Yu, J. et al. The genomes of Oryza sativa: a history of duplications. PLoS Biol. 3, e38 (2005)

Article Google Scholar - Nash, W. G., Wienberg, J., Ferguson-Smith, M. A., Menninger, J. C. & O’Brien, S. J. Comparative genomics: tracking chromosome evolution in the family Ursidae using reciprocal chromosome painting. Cytogenet. Cell Genet. 83, 182–192 (1998)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Kapitonov, V. V. & Jurka, J. A universal classification of eukaryotic transposable elements implemented in Repbase. Nature Rev. Genet. 9, 411–412, author reply 414 (2008)

Article Google Scholar - Smit, A. F. A., Hubley, R. & Green, P. RepeatMasker at 〈http://www.RepeatMasker.org〉.

- Nicholas, T. J. et al. The genomic architecture of segmental duplications and associated copy number variants in dogs. Genome Res. 19, 491–499 (2009)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Salamov, A. A. & Solovyev, V. V. Ab initio gene finding in Drosophila genomic DNA. Genome Res. 10, 516–522 (2000)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Stanke, M. & Waack, S. Gene prediction with a hidden Markov model and a new intron submodel. Bioinformatics 19 (suppl. 2). ii215–ii225 (2003)

Article Google Scholar - Alexeyenko, A., Tamas, I., Liu, G. & Sonnhammer, E. L. Automatic clustering of orthologs and inparalogs shared by multiple proteomes. Bioinformatics 22, e9–e15 (2006)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Nei, M. & Rooney, A. P. Concerted and birth-and-death evolution of multigene families. Annu. Rev. Genet. 39, 121–152 (2005)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Demuth, J. P., De Bie, T., Stajich, J. E., Cristianini, N. & Hahn, M. W. The evolution of mammalian gene families. PLoS One 1, e85 (2006)

Article ADS Google Scholar - Yang, Z. Likelihood ratio tests for detecting positive selection and application to primate lysozyme evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 15, 568–573 (1998)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Kosiol, C. et al. Patterns of positive selection in six mammalian genomes. PLoS Genet. 4, e1000144 (2008)

Article Google Scholar - Nielsen, R. et al. A scan for positively selected genes in the genomes of humans and chimpanzees. PLoS Biol. 3, e170 (2005)

Article Google Scholar - Chandrashekar, J. et al. T2Rs function as bitter taste receptors. Cell 100, 703–711 (2000)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Go, Y. Proceedings of the SMBE Tri-National Young Investigators’ Workshop 2005. Lineage-specific expansions and contractions of the bitter taste receptor gene repertoire in vertebrates. Mol. Biol. Evol. 23, 964–972 (2006)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Chandrashekar, J., Hoon, M. A., Ryba, N. J. & Zuker, C. S. The receptors and cells for mammalian taste. Nature 444, 288–294 (2006)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Nelson, G. et al. An amino-acid taste receptor. Nature 416, 199–202 (2002)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Yasuo, T., Kusuhara, Y., Yasumatsu, K. & Ninomiya, Y. Multiple receptor systems for glutamate detection in the taste organ. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 31, 1833–1837 (2008)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Zhang, B. et al. Genetic viability and population history of the giant panda, putting an end to the “evolutionary dead end”? Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1801–1810 (2007)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Donnelly, P. & Tavare, S. Coalescents and genealogical structure under neutrality. Annu. Rev. Genet. 29, 401–421 (1995)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Jurka, J. et al. Repbase Update, a database of eukaryotic repetitive elements. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 110, 462–467 (2005)

Article CAS Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to the faculty and staff of Beijing Genomics Institute at Shenzhen, whose names were not included in the author list, but who contributed to this team work. This project is funded by the Shenzhen Municipal Government and the Yantian District local government of Shenzhen. This project is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (30725008), Ole Romer grant from the Danish Natural Science Research Council, the Solexa project (272-07-0196), and Danish Strategic Research Council (2106-07-0021). We thank C. Wang, X. Huang and L. Luo for their assistance in collecting the blood sample. We thank D. D. Pollock for repeat content estimation. We thank M. Shi, Y. Wang and M. Ting Wong for analysis of the reproduction related genes. We also thank L. Goodman for editing the manuscript.

Author Contributions R.L., W.F., G.T., Ho.Z., L.H. and Jin.C. contributed equally to this work. Ju.W. and Ji.W. managed the project. Zhi.Z., R.H., F.S., He.Z., De.L., Ya.H., Jin.C., W.N., Jin.W. and W.W. prepared the panda DNA sample. X.Z., G.T., Jin.L., L.L., M.J., Da.L., Z.X., Jia.C., B.W., B.M., Z.W., Hu.L., X.R., Hu.Z., Si.L., Q.Z., Ju.Z., Y.R., Qin.L., Y.C., X.L. and Y.Z. performed sequencing. Ju.W., R.L. and W.F. designed analysis. Ho.Z., P.N., W.Q., G.S., S.Z., Run.L., F.T., J.R., M.Wa., Z.S., M.We., Xiao.W., H.W., L.X., T.-W.L. and S.-M.Y. performed genome assembly. Q.H., Q.C., Jia.L., J.M., Bi.L., Qib.L., Yu.H., Yang.Z., Ji.Z., W.G., X.X., Zu.L., X.S., Ho.L., D.Z. and Ni.Q. performed genome annotation. Ju.L., Bo.L., Y.B., Z.Y., S.C., Zha.Z., D.D., K.C., R.N., C.K., T.V., N.A., Sh.L., G.Z. and L.M. performed comparative genomics. Yap.Z., G.W., F.W., Q.W., M.W.B., L.H., Y.S., Zh.L., C.C.S., O.A.R., F.C.-C.L., T.T.-Y.L., Y.W., W.H., Y.F. and A.X. analysed genes related to panda-specific phenotypic characteristics. X.F., He.L., F.W., X.G., C.Yu., Hao.Z., Han.Z. and Y.L. identified heterozygous SNPs and performed panda historical population analysis. G.L., J.T., L.F., C.Ye. and T.G. performed data submission and database construction. Ju.W., Ji.W., R.L. and W.F. wrote the paper. X.W., G.Y., Y.G., Z.J., Juny.W., Na.Q., G.K.-S.W., L.B., M.O., K.K., So.L. and H.Y. revised the paper.

Author information

Author notes

- Ruiqiang Li, Wei Fan, Geng Tian, Hongmei Zhu, Lin He and Jing Cai: These authors contributed equally to this work.

Authors and Affiliations

- BGI-Shenzhen, Shenzhen 518083, China

Ruiqiang Li, Wei Fan, Geng Tian, Hongmei Zhu, Quanfei Huang, Qingle Cai, Bo Li, Yinqi Bai, Jun Li, Min Jian, Jianwen Li, Dawei Li, Zhentao Yang, Zhaoling Xuan, Yan Zhou, Jianjun Cao, Xiaodong Fang, Xiaosen Guo, Bo Wang, Bo Mu, Peixiang Ni, Runmao Lin, Wubin Qian, Chang Yu, Zhigang Wu, Huiqing Liang, Jiumeng Min, Shifeng Cheng, Jue Ruan, Mingwei Wang, Zhongbin Shi, Ming Wen, Binghang Liu, Xiaoli Ren, Huisong Zheng, Gao Shan, Hao Zhang, Hancheng Zheng, Yingrui Li, Siyuan Lin, Qinghui Zhang, Guoqing Li, Jing Tian, Timing Gong, Lin Fang, Chen Ye, Juanbin Zhang, Yuanyuan Ren, Guojie Zhang, Qibin Li, Lijia Ma, Yiran Guo, Na An, Yujie Hu, Yang Zheng, Qing Liu, Yanling Chen, Jing Zhao, Ning Qu, Shancen Zhao, Feng Tian, Xiaoling Wang, Haiyin Wang, Lizhi Xu, Xiao Liu, Xia Wang, Guohua Yang, Zhi Jiang, Junyi Wang, Nan Qin, Li Li, Jingxiang Li, Lars Bolund, Karsten Kristiansen, Gane Ka-Shu Wong, Xiuqing Zhang, Songgang Li, Huanming Yang, Jian Wang & Jun Wang - Department of Biology, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen DK-2200, Denmark

Ruiqiang Li, Karsten Kristiansen & Jun Wang - The Graduate University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100062, China

Geng Tian, Jing Cai, Guodong Wang, Jue Ruan, Yingrui Li, Guojie Zhang, Qibin Li, Lijia Ma, Yiran Guo, Yujie Hu & Yang Zheng - Institutes of Biomedical Sciences, Fudan University, 138 Yixueyuan Road, Shanghai 200032, China ,

Lin He - Bio-X Center, Key Laboratory for the Genetics of Developmental and Neuropsychiatric Disorders (Ministry of Education), Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai 200030, China

Lin He, Yongyong Shi & Zhiqiang Li - State Key Laboratory of Genetic Resources and Evolution, Kunming Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming 650223, China

Jing Cai, Yaping Zhang, Wen Wang, Guodong Wang, Wenhui Nie, Jinhuan Wang & Guojie Zhang - Genome Research Institute, Shenzhen University Medical School, Shenzhen 518000, China

Qingle Cai, Jiumeng Min, Shifeng Cheng & Ning Qu - Chengdu Research Base of Giant Panda Breeding, Chengdu 610081, China

Zhihe Zhang, Rong Hou & Fujun Shen - Key Lab of Animal Ecology and Conservation Biology, Institute of Zoology, the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beichenxilu 1-5, Chaoyang District, Beijing 100101, China ,

Fuwen Wei & Qi Wu - Wellcome Trust Genome Campus, Hinxton, Cambridge CB10 1SA, UK ,

Heng Li - Banting and Best Department of Medical Research, Department of Molecular Genetics, Donnelly Centre for Cellular and Biomolecular Research, University of Toronto, 160 College Street, Toronto, Ontario M5S 3E1, Canada,

Zhaolei Zhang, Dong Dong & Kathleen Cook - Departments of Integrative Biology and Statistics, UC-Berkeley, 3060 VLSB, Berkeley, California 94720, USA,

Rasmus Nielsen - Key Laboratory of Child Development and Learning Science, Southeast University, Ministry of Education, Nanjing 210096, China

Wanjun Gu, Xueying Xie & Zuhong Lu - San Diego Zoo’s Institute for Conservation Research, 15600 San Pasqual Valley Road, Escondido, California 92027, USA ,

Oliver A. Ryder & Cynthia C. Steiner - School of Biological Sciences, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China

Frederick Chi-Ching Leung & Tommy Tsan-Yuk Lam - State Key Laboratory of Bioelectronics, Southeast University, Nanjing 210096, China

Xiao Sun, Hongde Liu & Dejin Zhang - State Key Laboratory of Biocontrol, College of Life Sciences, Sun Yat-sen University, 510275 Guanghou, China

Yonggui Fu, Wenbo Hu & Anlong Xu - Institut für Populationsgenetik, Veterinärmedizinische Universität Wien, Veterinärplatz 1, 1210 Wien, Austria ,

Carolin Kosiol - Biodiversity and Ecological Processes Group, Cardiff School of Biosciences, Cardiff University, Cardiff CF10 3AX, UK

Michael W. Bruford - Department of Applied Informatics, Faculty of Mathematics, Physics, and Informatics, Comenius University, Mlynska Dolina, 84248 Bratislava, Slovakia,

Tomas Vinar - School of Life Science, Sichuan University, Chengdu 610064, China

Yajun Wang - Department of Computer Science, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China

Tak-Wah Lam & Siu-Ming Yiu - South China University of Technology, Guangzhou 510641, China

Shiping Liu - China Conservation and Research Centre for the Giant Panda, Wolong Nature Reserve 623006, China

Hemin Zhang, Desheng Li & Yan Huang - Department of Biological Sciences and Department of Medicine, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta T6G 2E9, Canada,

Gane Ka-Shu Wong - University of Washington Genome Center, Seattle 352145, USA

Maynard Olson

Authors

- Ruiqiang Li

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Wei Fan

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Geng Tian

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Hongmei Zhu

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Lin He

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Jing Cai

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Quanfei Huang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Qingle Cai

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Bo Li

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Yinqi Bai

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Zhihe Zhang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Yaping Zhang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Wen Wang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Jun Li

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Fuwen Wei

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Heng Li

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Min Jian

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Jianwen Li

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Zhaolei Zhang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Rasmus Nielsen

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Dawei Li

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Wanjun Gu

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Zhentao Yang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Zhaoling Xuan

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Oliver A. Ryder

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Frederick Chi-Ching Leung

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Yan Zhou

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Jianjun Cao

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Xiao Sun

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Yonggui Fu

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Xiaodong Fang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Xiaosen Guo

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Bo Wang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Rong Hou

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Fujun Shen

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Bo Mu

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Peixiang Ni

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Runmao Lin

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Wubin Qian

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Guodong Wang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Chang Yu

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Wenhui Nie

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Jinhuan Wang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Zhigang Wu

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Huiqing Liang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Jiumeng Min

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Qi Wu

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Shifeng Cheng

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Jue Ruan

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Mingwei Wang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Zhongbin Shi

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Ming Wen

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Binghang Liu

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Xiaoli Ren

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Huisong Zheng

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Dong Dong

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Kathleen Cook

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Gao Shan

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Hao Zhang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Carolin Kosiol

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Xueying Xie

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Zuhong Lu

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Hancheng Zheng

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Yingrui Li

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Cynthia C. Steiner

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Tommy Tsan-Yuk Lam

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Siyuan Lin

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Qinghui Zhang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Guoqing Li

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Jing Tian

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Timing Gong

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Hongde Liu

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Dejin Zhang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Lin Fang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Chen Ye

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Juanbin Zhang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Wenbo Hu

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Anlong Xu

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Yuanyuan Ren

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Guojie Zhang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Michael W. Bruford

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Qibin Li

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Lijia Ma

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Yiran Guo

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Na An

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Yujie Hu

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Yang Zheng

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Yongyong Shi

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Zhiqiang Li

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Qing Liu

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Yanling Chen

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Jing Zhao

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Ning Qu

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Shancen Zhao

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Feng Tian

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Xiaoling Wang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Haiyin Wang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Lizhi Xu

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Xiao Liu

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Tomas Vinar

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Yajun Wang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Tak-Wah Lam

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Siu-Ming Yiu

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Shiping Liu

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Hemin Zhang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Desheng Li

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Yan Huang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Xia Wang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Guohua Yang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Zhi Jiang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Junyi Wang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Nan Qin

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Li Li

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Jingxiang Li

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Lars Bolund

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Karsten Kristiansen

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Gane Ka-Shu Wong

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Maynard Olson

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Xiuqing Zhang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Songgang Li

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Huanming Yang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Jian Wang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Jun Wang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding authors

Correspondence toJian Wang or Jun Wang.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

This file contains Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Figures S1-S14 with Legends, Supplementary Tables S1-S20, Supplementary Results with Supplementary Figures SA1-SA6 with Legends and Supplementary Tables SA1-SA2 and Supplementary References. (PDF 1603 kb)

PowerPoint slides

Rights and permissions

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-Share Alike licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/), which permits distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. This licence does not permit commercial exploitation, and derivative works must be licensed under the same or similar licence.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, R., Fan, W., Tian, G. et al. The sequence and de novo assembly of the giant panda genome.Nature 463, 311–317 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08696

- Received: 19 August 2009

- Accepted: 24 November 2009

- Published: 13 December 2009

- Issue Date: 21 January 2010

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08696