Accurate whole human genome sequencing using reversible terminator chemistry (original) (raw)

Abstract

DNA sequence information underpins genetic research, enabling discoveries of important biological or medical benefit. Sequencing projects have traditionally used long (400–800 base pair) reads, but the existence of reference sequences for the human and many other genomes makes it possible to develop new, fast approaches to re-sequencing, whereby shorter reads are compared to a reference to identify intraspecies genetic variation. Here we report an approach that generates several billion bases of accurate nucleotide sequence per experiment at low cost. Single molecules of DNA are attached to a flat surface, amplified in situ and used as templates for synthetic sequencing with fluorescent reversible terminator deoxyribonucleotides. Images of the surface are analysed to generate high-quality sequence. We demonstrate application of this approach to human genome sequencing on flow-sorted X chromosomes and then scale the approach to determine the genome sequence of a male Yoruba from Ibadan, Nigeria. We build an accurate consensus sequence from >30× average depth of paired 35-base reads. We characterize four million single-nucleotide polymorphisms and four hundred thousand structural variants, many of which were previously unknown. Our approach is effective for accurate, rapid and economical whole-genome re-sequencing and many other biomedical applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

DNA sequencing yields an unrivalled resource of genetic information. We can characterize individual genomes, transcriptional states and genetic variation in populations and disease. Until recently, the scope of sequencing projects was limited by the cost and throughput of Sanger sequencing. The raw data for the three billion base (3 gigabase (Gb)) human genome sequence, completed in 2004 (ref. 1), was generated over several years for ∼$300 million using several hundred capillary sequencers. More recently an individual human genome sequence has been determined for ∼$10 million by capillary sequencing2. Several new approaches at varying stages of development aim to increase sequencing throughput and reduce cost3,4,5,6. They increase parallelization markedly by imaging many DNA molecules simultaneously. One instrument run produces typically thousands or millions of sequences that are shorter than capillary reads. Another human genome sequence was recently determined using one of these approaches7. However, much bigger improvements are necessary to enable routine whole human genome sequencing in genetic research.

We describe a massively parallel synthetic sequencing approach that transforms our ability to use DNA and RNA sequence information in biological systems. We demonstrate utility by re-sequencing an individual human genome to high accuracy. Our approach delivers data at very high throughput and low cost, and enables extraction of genetic information of high biological value, including single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and structural variants.

DNA sequencing using reversible terminators

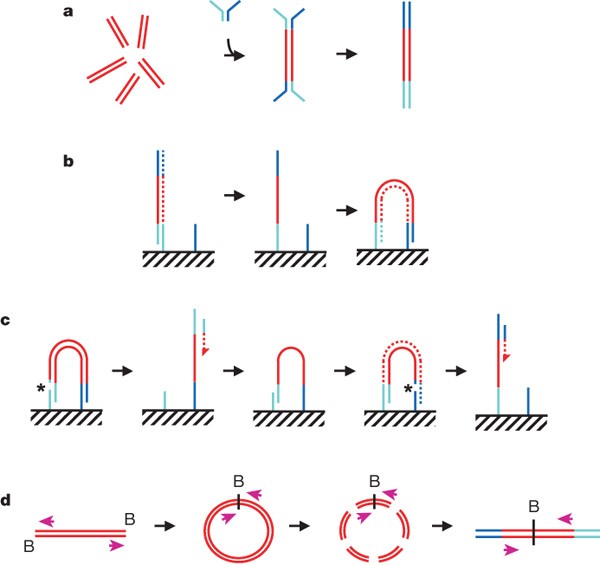

We generated high-density single-molecule arrays of genomic DNA fragments attached to the surface of the reaction chamber (the flow cell) and used isothermal ‘bridging’ amplification to form DNA ‘clusters’ from each fragment. We made the DNA in each cluster single-stranded and added a universal primer for sequencing. For paired read sequencing, we then converted the templates to double-stranded DNA and removed the original strands, leaving the complementary strand as template for the second sequencing reaction (Fig. 1a–c). To obtain paired reads separated by larger distances, we circularized DNA fragments of the required length (for example, 2 ± 0.2 kb) and obtained short junction fragments for paired end sequencing (Fig. 1d).

Figure 1: Preparation of samples.

a, DNA fragments are generated, for example, by random shearing and joined to a pair of oligonucleotides in a forked adaptor configuration. The ligated products are amplified using two oligonucleotide primers, resulting in double-stranded blunt-ended material with a different adaptor sequence on either end. b, Formation of clonal single-molecule array. DNA fragments prepared as in a are denatured and single strands are annealed to complementary oligonucleotides on the flow-cell surface (hatched). A new strand (dotted) is copied from the original strand in an extension reaction that is primed from the 3′ end of the surface-bound oligonucleotide; the original strand is then removed by denaturation. The adaptor sequence at the 3′ end of each copied strand is annealed to a new surface-bound complementary oligonucleotide, forming a bridge and generating a new site for synthesis of a second strand (dotted). Multiple cycles of annealing, extension and denaturation in isothermal conditions result in growth of clusters, each ∼1 μm in physical diameter. This follows the basic method outlined in ref. 33. c, The DNA in each cluster is linearized by cleavage within one adaptor sequence (gap marked by an asterisk) and denatured, generating single-stranded template for sequencing by synthesis to obtain a sequence read (read 1; the sequencing product is dotted). To perform paired-read sequencing, the products of read 1 are removed by denaturation, the template is used to generate a bridge, the second strand is re-synthesized (shown dotted), and the opposite strand is then cleaved (gap marked by an asterisk) to provide the template for the second read (read 2). d, Long-range paired-end sample preparation. To sequence the ends of a long (for example, >1 kb) DNA fragment, the ends of each fragment are tagged by incorporation of biotinylated (B) nucleotide and then circularized, forming a junction between the two ends. Circularized DNA is randomly fragmented and the biotinylated junction fragments are recovered and used as starting material in the standard sample preparation procedure illustrated in a. The orientation of the sequence reads relative to the DNA fragment is shown (magenta arrows). When aligned to the reference sequence, these reads are oriented with their 5′ ends towards each other (in contrast to the short insert paired reads produced as shown in a–c). See Supplementary Fig. 17a for examples of both. Turquoise and blue lines represent oligonucleotides and red lines represent genomic DNA. All surface-bound oligonucleotides are attached to the flow cell by their 5′ ends. Dotted lines indicate newly synthesized strands during cluster formation or sequencing. (See Supplementary Methods for details.)

We sequenced DNA templates by repeated cycles of polymerase-directed single base extension. To ensure base-by-base nucleotide incorporation in a stepwise manner, we used a set of four reversible terminators, 3′-_O_-azidomethyl 2′-deoxynucleoside triphosphates (A, C, G and T), each labelled with a different removable fluorophore (Supplementary Fig. 1a)8. The use of 3′-modified nucleotides allowed the incorporation to be driven essentially to completion without risk of over-incorporation. It also enabled addition of all four nucleotides simultaneously rather than sequentially, minimizing risk of misincorporation. We engineered the active site of 9°N DNA polymerase to improve the efficiency of incorporation of these unnatural nucleotides9. After each cycle of incorporation, we determined the identity of the inserted base by laser-induced excitation of the fluorophores and imaging. We added tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) to remove the fluorescent dye and side arm from a linker attached to the base and simultaneously regenerate a 3′ hydroxyl group ready for the next cycle of nucleotide addition (Supplementary Fig. 1b). The Genome Analyzer (GA1) was designed to perform multiple cycles of sequencing chemistry and imaging to collect the sequence data automatically from each cluster on the surface of each lane of an eight-lane flow cell (Supplementary Fig. 2).

To determine the sequence from each cluster, we quantified the fluorescent signal from each cycle and applied a base-calling algorithm. We defined a quality (Q) value for each base call (scaled as by the phred algorithm10) that represents the likelihood of each call being correct (Supplementary Fig. 3). We used the Q-values in subsequent analyses to weight the contribution of each base to sequence alignment and detection of sequence variants (for example, SNP calling). We discarded all reads from mixed clusters and used the remaining ‘purity filtered’ reads for analysis. Typically we generated 1–2 Gb of high-quality purity filtered sequence per flow cell from ∼30–60-million single 35-base reads, or 2–4 Gb in a paired read experiment (Supplementary Table 1).

To demonstrate accurate sequencing of human DNA, we sequenced a human bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) clone (bCX98J21) that contained 162,752 bp of the major histocompatibility complex on human chromosome 6 (accession AL662825.4, previously determined using capillary sequencing by the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute). We developed a fast global alignment algorithm ELAND that aligns a read to the reference only if the read can be assigned a unique position with 0, 1 or 2 differences. We collected 0.17 Gb of aligned data for the BAC from one lane of a flow cell. Approximately 90% of the 35-base reads matched perfectly to the reference, demonstrating high raw read accuracy (Supplementary Fig. 4). To examine consensus coverage and accuracy, we used 5 Mb of 35-base purity filtered reads (30-fold average input depth of the BAC) and obtained 99.96% coverage of the reference. There was one consensus miscall, at a position of very low coverage (just above our cutoff threshold), yielding an overall consensus accuracy of >99.999%.

Detecting genetic variation of the human X chromosome

For an initial study of genetic variation, we sequenced flow-sorted X chromosomes of a Caucasian female (sample NA07340 originating from the Centre d’Etude du Polymorphisme Humain (CEPH)). We generated 278-million paired 30–35-bp purity filtered reads and aligned them to the human genome reference sequence. We carried out separate analyses of the data using two alignment algorithms: ELAND (see above) or MAQ (Mapping and Assembly with Qualities)11. Both algorithms place each read pair where it best matches the reference and assign a confidence score to the alignment. In cases where a read has two or more equally likely positions (that is, in an exact repeat), MAQ randomly assigns the read pair to one position and assigns a zero alignment quality score (these reads are excluded from SNP analysis). ELAND rejects all non-unique alignments, which are mostly in recently inserted retrotransposons (see Supplementary Fig. 5). MAQ therefore provides an opportunity to assess the properties of a data set aligned to the entire reference, whereas ELAND effectively excludes ambiguities from the short read alignment before further analysis.

We obtained comprehensive coverage of the X chromosome from both analyses. With MAQ, 204 million reads aligned to 99.94% of the X chromosome at an average depth of 43×. With ELAND, 192 million reads covered 91% of the reference sequence, showing what can be covered by unique best alignments. These results were obtained after excluding reads aligning to non-X sequence (impurities of flow sorting) and apparently duplicated read pairs (Supplementary Table 2). We reasoned that these duplicates (∼10% of the total) arose during initial sample amplification.

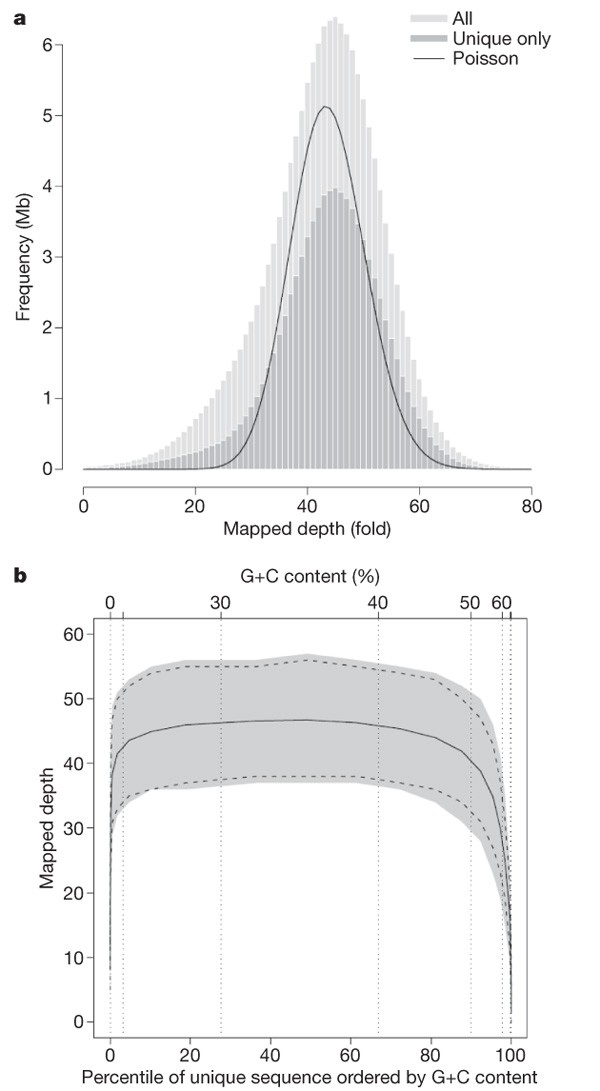

The sampling of sequence fragments from the X chromosome is close to random. This is evident from the distribution of mapped read depth in the MAQ alignment in regions where the reference is unique (Fig. 2a): the variance of this distribution is only 2.26 times that of a Poisson distribution (the theoretical minimum). Half of this excess variance can be accounted for by a dependence on G+C content. However, the average mapped read depth only falls below 10× in regions with G+C content less than 4% or greater than 76%, comprising in total just 1% of unique chromosome sequence and 3% of coding sequence (Fig. 2b).

Figure 2: X chromosome data.

a, Distribution of mapped read depth in the X chromosome data set (NA07340), sampled at every 50th position along the chromosome and displayed as a histogram (‘All’). An equivalent analysis of mapped read depth for the unique subset of these positions is also shown (‘Unique only’). The solid line represents a Poisson distribution with the same mean. b, Distribution of X chromosome uniquely mapped reads as a function of G+C content. Note that the x axis is per cent G+C content and is scaled by percentile of unique sequence. The solid line is average mapped depth of unique sequence; the grey region is the central 80% of the data (10th to 90th centiles); the dashed lines are 10th and 90th centiles of a Poisson distribution with the same mean as the data.

We identified 92,485 candidate SNPs in the X chromosome using ELAND (Supplementary Fig. 6). Most calls (85%) match previous entries in the public database dbSNP. Heterozygosity (π) in this data set is 4.3 × 10-4 (that is, one substitution per 2.3 kb), close to a previously published X chromosome estimate (4.7 × 10-4)12. Using MAQ we obtained 104,567 SNPs, most of which were common to the results of the ELAND analysis. The differences between the two sets of SNP calls are largely the consequence of different properties of the alignments as described earlier. For example, most of the SNPs found only by the MAQ-based analysis were at positions of low or zero sequence depth in the ELAND alignment (Supplementary Fig. 6c).

We assessed accuracy and completeness of SNP calling by comparison to genotypes obtained for this individual using the Illumina HumanHap550 BeadChip (HM550). The sequence data covered >99.8% of the 13,604 genotyped positions and we found excellent agreement between sequence-based SNP calls and genotyping data (99.52% or 99.99% using ELAND or MAQ, respectively; Supplementary Table 3). There was complete concordance of all homozygous calls and a low level of ‘under-calling’ from the sequence data (denoted as ‘GT>Seq’ in Table 1) at a small number of the heterozygous sites, caused by inadequate sampling of one of the two alleles. The depth of input sequence influences the coverage and accuracy of SNP calling. We found that reducing the read depth to 15× still gives 97% coverage of genotype positions and only 1.27% of the heterozygous sites are under-called. We observed no other types of disagreement at any input depth (Supplementary Fig. 7).

Table 1 Comparison of SNP calls made from sequence versus genotype data for the human genome (NA18507) and X chromosome (NA07340)

We detected structural variants (defined as any variant other than a single base substitution) as follows. We found 9,747 short insertions/deletions (‘short indels’; defined here as less than the length of the read) by performing a gapped alignment of individual reads (Supplementary Fig. 8). We identified larger indels based on read depth and/or anomalous read pair spacing, similar to previous approaches13,14,15. We detected 115 indels in total, 77 of which were visible from anomalous read-pair spacing (see Supplementary Tables 4 and 5). We developed Resembl, an extension to the Ensembl browser16, to view all variants (Supplementary Fig 9). Inversions can be detected when the orientation of one read in a pair is reversed (for example, see Supplementary Fig. 10). In general, inversions occur as the result of non-allelic homologous recombination, and are therefore flanked by repetitive sequence that can compromise alignments. We found partial evidence for other inversion events, but characterization of inversions from short read data is complex because of the repeats and requires further development.

Sequencing and analysis of a whole human genome

Our X chromosome study enabled us to develop an integrated set of methods for rapid sequencing and analysis of whole human genomes. We sequenced the genome of a male Yoruba from Ibadan, Nigeria (YRI, sample NA18507). This sample was originally collected for the HapMap project17,18 through a process of community engagement and informed consent19 and has also been studied in other projects20,21. We were therefore able to compare our results with publicly available data from the same sample. We constructed two libraries: one of short inserts (∼200 bp) with similar properties to the previous X chromosome library and one from long fragments (∼2 kb) to provide longer-range read-pair information (see Supplementary Fig. 11 for size distributions). We generated 135 Gb of sequence (∼4 billion paired 35-base reads; see Supplementary Table 6) over a period of 8 weeks (December 2007 to January 2008) on six GA1 instruments averaging 3.3 Gb per production run (see Supplementary Table 1 for example). The approximate consumables cost (based on full list price of reagents) was $250,000. We aligned 97% of the reads using MAQ and found that 99.9% of the human reference (NCBI build 36.1) was covered with one or more reads at an average of 40.6-fold depth. Using ELAND, we aligned 91% of the reads over 93% of the reference sequence at sufficient depth to call a strong consensus (>three Q30 bases). The distribution of mapped read depth was close to random, with slight over-dispersion as seen for the X chromosome data. We observed comprehensive representation across a wide range of G+C content, dropping only at the very extreme ends, but with a different pattern of distribution compared to the X chromosome (see Supplementary Fig. 12).

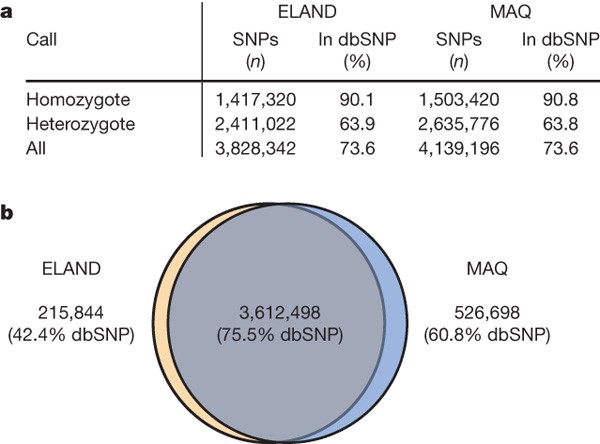

We identified ∼4 million SNPs, with 74% matching previous entries in dbSNP (Fig. 3). We found excellent agreement of our SNP calls with genotyping results: sequence-based SNP calls covered almost all of the 552,710 loci of HM550, with >99.5% concordance of sequencing versus genotyping calls (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 7a). The few disagreements were mostly under-calls of heterozygous positions (GT>Seq) in areas of low sequence depth, providing us with a false-negative rate of <0.35% from the ELAND analysis (see Table 1). The other disagreements (0.09% of all genotypes) included errors in genotyping plus apparent tri-allelic SNPs (Supplementary Table 7a). The main cause of genotype error (0.05% of all genotypes) is the existence of a second ‘hidden’ SNP close to the assayed locus that disrupts the genotyping assay, leading to loss of one allele and an erroneous homozygous genotype (Supplementary Figs 13 and 14).

Figure 3: SNPs identified in the human genome sequence of NA18507.

a, Number of SNPs detected by class and percentage in dbSNP (release 128). Results from ELAND and MAQ alignments are reported separately. b, Analysis of SNPs detected in each analysis reveals extensive overlap. The percentage of NA18507 SNP calls that match previous entries in dbSNP is lower than that of our X chromosome study (see Supplementary Fig. 6). We expect this because individual NA07340 (from the X chromosome study) was also previously used for discovery and submission of SNPs to dbSNP during the HapMap project, in contrast to NA18507.

To examine the accuracy of SNP calling in more detail, we compared our sequence-based SNP calls with 3.7 million genotypes (HM-All) generated for this sample during the HapMap project (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 7b)18 and found excellent concordance between the data sets. Disagreements included sequence-based under-calls of heterozygous positions in regions of low read depth. The slightly higher level of other disagreements (0.76%) seen in this analysis compared to that of the HM550 data (0.09%) is in line with the higher level of underlying genotype error rate of 0.7% for the HapMap data18. To refine this analysis further, we generated a set of 530,750 very high confidence reference genotypes comprising concordant calls in both the HM550 and HM-All genotype data sets. Comparing the results of the MAQ analysis to this high confidence set (see Table 1), we found 130 heterozygote under-calls GT>Seq (that is, a false-negative rate of 0.025%). There were also 130 heterozygote over-calls Seq>GT, but most of these are probably genotype errors as 82 have a nearby ‘hidden’ SNP and 3 have a nearby indel. A further 41 are tri-allelic loci, leaving at most 4 potential wrong calls by sequencing (that is, false-positive rate of 4 per 529,589 positions). Finally we selected a subset of novel SNP calls from the sequence data and tested them by genotyping. We found 96.1% agreement between sequence and genotype calls (Supplementary Table 8). However, the 47 disagreements included 10 correct sequencing calls (genotyping under-calls owing to hidden SNPs) and 7 sequencing under-calls. On this basis, therefore, the false-positive discovery rate for the one million novel SNPs is 2.5% (30 out of 1,206). For the entire data set of four million SNPs detected in this analysis, the false-positive and -negative rates both average <1%.

This genome from a Yoruba individual contains significantly more polymorphism than a genome of European descent. The autosomal heterozygosity (π) of NA18507 is 9.94 × 10-4 (1 SNP per 1,006 bp), higher than previous values for Caucasians (7.6 × 10-4, ref. 12). Heterozygosity in the pseudoautosomal region 1 (PAR1) is substantially higher (1.92 × 10-3) than the autosomal value. PAR1 (2.7 Mb) at the tip of the short arm of chromosomes X and Y undergoes obligatory recombination in male meiosis, which is equivalent to 20× the autosome average. This illustrates a clear correlation between recombination and nucleotide diversity. By contrast, the 0.33-Mb PAR2 region has a much lower recombination rate than PAR1; we observed that heterozygosity in PAR2 is identical to that of the autosomes in NA18507. Heterozygosity in coding regions is lower (0.54 × 10-3) than the total autosome average, consistent with the model that some coding changes are deleterious and are lost as the result of natural selection22. Nevertheless, the 26,140 coding SNPs (Supplementary Fig. 15) include 5,361 non-conservative amino acid substitutions plus 153 premature termination codons (Supplementary Table 9), many of which are expected to affect protein function.

We performed a genome-wide survey of structural variation in this individual and found excellent correlation with variants that had been reported in previous studies, as well as detecting many new variants. We found 0.4 million short indels (1–16 bp; Supplementary Fig. 16), most of which are length polymorphisms in homopolymeric tracts of A or T. Half of these events are corroborated by entries in dbSNP, and 95 of 100 examined were present in amplicons sequenced from this individual in ENCODE regions, confirming the high specificity of this method of short indel detection. For larger structural variants (detected by anomalously spaced paired ends) we found that some were detected by both long and short insert data sets (Supplementary Fig. 17a), but most were unique to one or other data set. We observed two reasons for this: first, small events (<400 bp) are within the normal size variance of the long insert data; second, nearby repetitive structures can prevent unique alignment of read pairs (see Supplementary Fig. 17b, c). In some cases, the high resolution of the short insert data permits detection of additional complexity in a structural rearrangement that is not revealed by the long insert data. For example, where the long insert data indicate a 1.3-kb deletion in NA18507 relative to the reference, the short insert data reveal an inversion accompanied by deletions at both breakpoints (Fig. 4). We carried out de novo assembly of reads in this region and constructed a single contig that defines the exact structure of the rearrangement (data not shown).

Figure 4: Homozygous complex rearrangement detected by anomalous paired reads.

The rearrangement involves an inversion of 369 bp (blue–turquoise bar in the schematic diagram) flanked by deletions (red bars) of 1,206 and 164 bp, respectively, at the left- and right-hand breakpoints. a, Summary tracks in the Resembl browser, denoting scale, simulated alignability of reads to reference (blue plot), actual aligned depth of coverage by NA18507 reads (green plot), density of anomalous reads indicating structural variants (red plot; peaks denote ‘hotspots’) and density of singleton reads (pink plot). b, Anomalous long-insert read pairs (orange lines denote DNA fragment; blocks at either end denote each read); the data indicate loss of ∼1.3 kb in NA18507 relative to the reference. c, Anomalous short-insert pairs of two types (red and pink) indicate an inverted sequence flanked by two deletions. d, Normal short-insert read-pair alignments (each green line denotes the extent of the reference that is covered by the short fragment, including the two reads). e, The schematic diagram depicts the arrangement of normal and anomalous read pairs relative to the rearrangement. Top line, structure of NA18507; second line, structure of reference sequence. Green bars denote sequence that is collinear in the reference and NA18507 genomes. The turquoise–blue bar illustrates the inverted segment. Red bars indicate the sequences present in the reference but absent in NA18507. Arrows denote orientation of reads when aligned to the reference. The display in a–d is a composite of screen shots of the same window, overlapped for display purposes.

We discovered 5,704 structural variants ranging from 50 bp to >35 kb where there is sequence absent from the genome of NA18507 compared to the reference genome. We observed a steadily decreasing number of events of this type with increasing size, except for two peaks (Supplementary Fig. 18). Most of the events represented by the large peak at 300–350 bp contain a sequence of the AluY family. This is consistent with insertion of short interspersed nuclear elements (SINEs) that are present in the reference genome but missing from the genome of NA18507. Similarly, the second, smaller peak at 6–7 kb is the consequence of insertion of the long interspersed nuclear element (LINE) L1 Homo sapiens (L1Hs) in many cases. We found good correspondence between our results and the data of ref. 23, which reported 148 deletions of <100 kb in this individual on the basis of abnormal fosmid paired-end spacing. We found supporting evidence for 111 of these events. We detected a further 2,345 indels in the range 60–160 bp which are sequences present in the genome of NA18507 and absent from the reference genome (Supplementary Fig. 19). One example is shown in Supplementary Fig. 20. The ‘singleton’ reads on either side of the event, which have partners that do not align to the reference, form part of a de novo assembly that precisely defines the novel sequence and breakpoint (Supplementary Fig. 21).

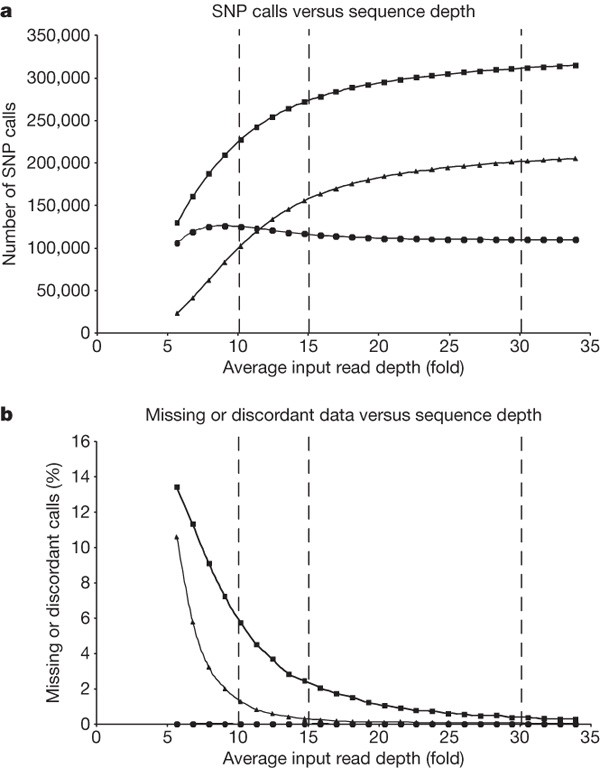

Effect of sequence depth on coverage and accuracy

We investigated the impact of varying input read depth (and hence cost) on SNP calling using chromosome 2 as a model. SNP discovery increases with increasing depth: essentially all homozygous positions are detected at 15×, whereas heterozygous positions accumulate more gradually to 33× (Fig. 5a). This effect is influenced by the stringency of the SNP caller. To call each allele in this analysis we required the equivalent of two high-quality Q30 bases (as opposed to three used in full depth analyses). Homozygotes could be detected at read depth of 2× or higher, whereas heterozygote detection required at least double this depth for sampling of both alleles. Missing calls (not covered by sequence) and discordances between sequence-based SNP calls and genotype loci (mostly under-calls of heterozygotes due to low depth) progressively reduced with increasing depth (Fig. 5b). We observed very few other types of discordance at any depth; many of these are genotyping errors as described above.

Figure 5: Effect of sequence depth on coverage and accuracy of human genome sequencing.

ELAND alignments were used for this analysis. a, Accumulation of sequence-based SNP calls, including all SNPs (squares), heterozygous SNPs (triangles) and homozygous SNPs (circles) with increasing input read depth. b, Decrease in genotype positions not covered by sequence (squares), heterozygote under-calls in sequence data relative to genotype data (triangles) and discordant SNP calls compared to genotypes (circles) with increasing input read depth. Vertical dotted lines indicate various input read depths (10×, 15×, 30× haploid genome).

Concluding remarks

Reversible terminator chemistry is a defining feature of this sequencing approach, enabling each cycle to be driven to completion while minimizing misincorporation. The result is a system that generates accurate data at very high throughput and low cost. We determined an accurate whole human genome sequence in 8 weeks to an average depth of ∼40×. We built a consensus sequence, optimized methods for analysis, assessed accuracy and characterized the genetic variation of this individual in detail.

We assessed accuracy relative to genotype data over the entire fraction of the human sequence where SNP calling was possible (>90%). We established very low false-positive and -negative rates for the ∼four million SNPs detected (<1% over-calls and under-calls). This compares favourably with previous individual genome analyses which reported a 24% under-calling of heterozygous positions2,7.

Paired reads were very powerful in all areas of the analysis. They provided very accurate read alignment and thus improved the accuracy and coverage of consensus sequence and SNP calling. They were essential for developing our short indel caller, and for detecting larger structural variants. Our short-insert paired-read data set introduced a new level of resolution in structural variation detection, revealing thousands of variants in a size range not characterized previously. In some cases we determined the exact sequence of structural variants by de novo assembly from the same paired-read data set. Interpreting events that are embedded in repetitive sequence tracts will require further work.

Massively parallel sequencing technology makes it feasible to consider whole human genome sequencing as a clinical tool in the near future. Characterizing multiple individual genomes will enable us to unravel the complexities of human variation in cancer and other diseases and will pave the way for the use of personal genome sequences in medicine and healthcare. Accuracy of personal genetic information from sequence will be critical for life-changing decisions.

In addition to the large-scale genomic projects exemplified by the present study and others15,24,25,26, the system described here is being used to explore biological phenomena in unprecedented detail, including transcriptional activity, mechanisms of gene regulation and epigenetic modification of DNA and chromatin27,28,29,30,31,32. In the future, DNA sequencing will be the central tool for unravelling how genetic information is used in living processes.

Methods Summary

DNA and sequencing

DNA samples (NA07340 and NA18507) and cell line (GM07340) were obtained from Coriell Repositories. DNA samples were genotyped on the HM550 array and the results compared to publicly available data to confirm their identity before use. Methods for DNA manipulation, including sample preparation, formation of single-molecule arrays, cluster growth and sequencing were all developed during this study and formed the basis for the standard protocols now available from Illumina, Inc. All sequencing was performed on Illumina GA1s equipped with a one-megapixel camera. All purity filtered read data are available for download from the Short Read Archive at NCBI or from the European Short Read Archive (ERA) at the EBI.

Analysis software

Image analysis software and the ELAND aligner are provided as part of the Genome Analyzer analysis software. SNP and structural variant detectors will be available as future upgrades of the analysis pipeline. The Resembl extension to Ensembl is available on request. The MAQ (Mapping and Assembly with Qualities) aligner is freely available for download from http://maq.sourceforge.net.

Data access

Sequence data for NA18507 are freely available from the NCBI short read archive, accession SRA000271 (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/pub/TraceDB/ShortRead/SRA000271). X chromosome data are freely available from ERA, accession ERA000035. Links to Resembl displays for chromosome X and human data, plus information on other available data, are provided at http://www.illumina.com/HumanGenome.

See Supplementary Methods for a detailed Methods section.

References

- International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium. Finishing the euchromatic sequence of the human genome. Nature 431, 931–945 (2004)

- Levy, S. et al. The diploid genome sequence of an individual human. PLoS Biol. 5, e254 (2007)

Article Google Scholar - Margulies, M. et al. Genome sequencing in microfabricated high-density picolitre reactors. Nature 437, 376–380 (2005)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Shendure, J. et al. Accurate multiplex polony sequencing of an evolved bacterial genome. Science 309, 1728–1732 (2005)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Harris, T. D. et al. Single-molecule DNA sequencing of a viral genome. Science 320, 106–109 (2008)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Lundquist, P. M. et al. Parallel confocal detection of single molecules in real time. Opt. Lett. 33, 1026–1028 (2008)

Article ADS Google Scholar - Wheeler, D. A. et al. The complete genome of an individual by massively parallel DNA sequencing. Nature 452, 872–876 (2008)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Milton, J. et al. Modified nucleotides. World Intellectual Property Organization WO/2004/018497. (2004)

- Smith, G. P. et al. Modified polymerases for improved incorporation of nucleotide analogues. World Intellectual Property Organization WO/2005/024010. (2005)

- Ewing, B. & Green, P. Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. II. Error probabilities. Genome Res. 8, 186–194 (1998)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Li, H., Ruan, J. & Durbin, R. Mapping short DNA sequencing reads and calling variants using mapping quality scores. Genome Res. doi: 10.1101/gr.078212.108 (25 September 2008)

- The International SNP Map Working Group. A map of human genome sequence variation containing 1.42 million single nucleotide polymorphisms. Nature 409, 928–933 (2001)

- Tuzun, E. et al. Fine-scale structural variation of the human genome. Nature Genet. 37, 727–732 (2005)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Korbel, J. O. et al. Paired-end mapping reveals extensive structural variation in the human genome. Science 318, 420–426 (2007)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Campbell, P. J. et al. Identification of somatically acquired rearrangements in cancer using genome-wide massively parallel paired-end sequencing. Nature Genet. 40, 722–729 (2008)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Hubbard, T. et al. The Ensembl genome database project. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 38–41 (2002)

Article CAS Google Scholar - The International HapMap Consortium. A haplotype map of the human genome. Nature 437, 1299–1320 (2005)

- The International HapMap Consortium. A second generation human haplotype map of over 3.1 million SNPs. Nature 449, 851–861 (2007)

- The International HapMap Consortium. The International HapMap Project. Nature 426, 789–796 (2003)

- The ENCODE Project Consortium. Identification and analysis of functional elements in 1% of the human genome by the ENCODE pilot project. Nature 447, 799–816 (2007)

- Redon, R. et al. Global variation in copy number in the human genome. Nature 444, 444–454 (2006)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Cargill, M. et al. Characterization of single-nucleotide polymorphisms in coding regions of human genes. Nature Genet. 22, 231–238 (1999)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Kidd, J. M. et al. Mapping and sequencing of structural variation from eight human genomes. Nature 453, 56–64 (2008)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Hillier, L. W. et al. Whole-genome sequencing and variant discovery in C. elegans . Nature Methods 5, 183–188 (2008)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Hodges, E. et al. Genome-wide in situ exon capture for selective resequencing. Nature Genet. 39, 1522–1527 (2007)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Porreca, G. J. et al. Multiplex amplification of large sets of human exons. Nature Methods 4, 931–936 (2007)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Barski, A. et al. High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell 129, 823–837 (2007)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Johnson, D. S., Mortazavi, A., Myers, R. M. & Wold, B. Genome-wide mapping of in vivo protein-DNA interactions. Science 316, 1497–1502 (2007)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Mikkelsen, T. S. et al. Genome-wide maps of chromatin state in pluripotent and lineage-committed cells. Nature 448, 553–560 (2007)

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Boyle, A. P. et al. High-resolution mapping and characterization of open chromatin across the genome. Cell 132, 311–322 (2008)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Lister, R. et al. Highly integrated single-base resolution maps of the epigenome in Arabidopsis . Cell 133, 523–536 (2008)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Mortazavi, A., Williams, B. A., McCue, K., Schaeffer, L. & Wold, B. Mapping and quantifying mammalian transcriptomes by RNA-Seq. Nature Methods 5, 585–587 (2008)

Article Google Scholar - Fedurco, M., Romieu, A., Williams, S., Lawrence, I. & Turcatti, G. BTA, a novel reagent for DNA attachment on glass and efficient generation of solid-phase amplified DNA colonies. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, e22 (2006)

Article Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the advice of A. Williamson, T. Rink, S. Benkovic, J. Berriman, J. Todd, R. Waterston, S. Eletr, W. Jack, M. Cooper, T. Brown, C. Reece and R. Cook during this work; E. Margulies for assistance with data analysis; M. Shumway for assistance with data submission; and the contributions of the administrative and support staff at all the institutions. This research was supported in part by The Wellcome Trust (to H.L., A.Sc., K.W., N.P.C, B.N.L., J.R., M.E.H. and R.D.), the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) (to S.B. and D.K.), the BBSRC Applied Genomics LINK Programme (to A.Sp. and C.L.B.) and the Intramural Research Program of the National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health (to N.F.H. and J.C.M.). S. Balasubramanian and D. Klenerman are inventors and founders of Solexa Ltd.

Author information

Author notes

- Harold P. Swerdlow, John Milton, Clive G. Brown, Jane Rogers & Nick J. McCooke

Present address: †Present addresses: The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Wellcome Trust Genome Campus, Hinxton, Cambridge CB10 1SA, UK (H.P.S.); Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Begbroke Science Park, Sandy Lane, Kidlington OX5 1PF, UK (J.M., C.G.B.); BBSRC Genome Analysis Centre, John Innes Centre, Norwich Research Park, Colney, Norwich NR4 7UH, UK (J.R.); Pronota, NV, VIB Bio-Incubator, Technologiepark 4, B-9052 Zwijnaarde/Ghent, Belgium (N.J.M.).,

Authors and Affiliations

- Illumina Cambridge Ltd. (Formerly Solexa Ltd), Chesterford Research Park, Little Chesterford, Nr Saffron Walden, Essex CB10 1XL, UK.,

David R. Bentley, Harold P. Swerdlow, Geoffrey P. Smith, John Milton, Clive G. Brown, Kevin P. Hall, Dirk J. Evers, Colin L. Barnes, Helen R. Bignell, Jonathan M. Boutell, Jason Bryant, Richard J. Carter, R. Keira Cheetham, Anthony J. Cox, Darren J. Ellis, Niall A. Gormley, Sean J. Humphray, Leslie J. Irving, Xiaohai Liu, Klaus S. Maisinger, Lisa J. Murray, Bojan Obradovic, Tobias Ost, Michael L. Parkinson, Isabelle M. J. Rasolonjatovo, Roberto Rigatti, Chiara Rodighiero, Mark T. Ross, Andrea Sabot, Mark E. Smith, Vincent P. Smith, Anastassia Spiridou, Peta E. Torrance, Xiaolin Wu, Carole Anastasi, Ify C. Aniebo, David M. D. Bailey, Iain R. Bancarz, Selena G. Barbour, Vincent A. Benoit, Kevin F. Benson, Claire Bevis, Phillip J. Black, Asha Boodhun, Joe S. Brennan, Rob C. Brown, Andrew A. Brown, Abass A. Bundu, Maria Chiara E. Catenazzi, R. Neil Cooley, Natasha R. Crake, Olubunmi O. Dada, Konstantinos D. Diakoumakos, Belen Dominguez-Fernandez, David J. Earnshaw, Ugonna C. Egbujor, Louise J. Fraser, Karin V. Fuentes Fajardo, Colin P. Goddard, David E. Green, Kevin Harnish, Narinder I. Heyer, Matthew M. Hims, Adrian M. Horgan, Katya Hoschler, Terena James, T. A. Huw Jones, Gyoung-Dong Kang, Alan D. Kersey, Zoya Kingsbury, Paula I. Kokko-Gonzales, Anil Kumar, Sarah E. Lee, Jennifer A. Loch, Radhika M. Mammen, Patrick G. McCauley, Parul Mehta, Taksina Newington, Sonia M. Novo, Mark A. Osborne, Andrew Osnowski, Lea Pickering, Andrew C. Pike, Come Raczy, Vicki H. Rae, Stephen R. Rawlings, Ana Chiva Rodriguez, Phyllida M. Roe, John Rogers, Maria C. Rogert Bacigalupo, Nikolai Romanov, Natalie J. Rourke, Silke T. Ruediger, Raquel M. Sanches-Kuiper, Martin R. Schenker, Richard J. Shaw, Melanie A. Smith, Jean Ernest Sohna Sohna, Kim Stevens, Neil Sutton, Lukasz Szajkowski, Carolyn L. Tregidgo, Stephanie vandeVondele, Jingwen Wang, Graham J. Worsley, Nick J. McCooke & Anthony J. Smith - Department of Chemistry, University of Cambridge, The University Chemical Laboratory, Lensfield Road, Cambridge CB2 1EW, UK.,

Shankar Balasubramanian, Colin L. Barnes, Xiaohai Liu, David J. Earnshaw, W. Scott Furey, Mark A. Osborne & David Klenerman - Illumina Hayward (Formerly Solexa Inc.), 23851 Industrial Boulevard, Hayward, California 94343, USA.,

Michael R. Flatbush, Mirian S. Karbelashvili, Scott M. Kirk, Mark R. Pratt, Mark T. Reed, Subramanian V. Sankar, Gary P. Schroth, Svilen S. Tzonev, Eric H. Vermaas, Lu Zhang, Mohammed D. Alam, Saibal Banerjee, Primo A. Baybayan, John A. Bridgham, Dale H. Buermann, James C. Burrows, Nestor Castillo, Simon Chang, David W. Elmore, Sergey S. Etchin, Mark R. Ewan, David George, George S. Golda, Philip A. Granieri, David L. Gustafson, Christian D. Haudenschild, Johnny T. Ho, Steve Hurwitz, Denis V. Ivanov, Maria Q. Johnson, Tzvetana H. Kerelska, Irina Khrebtukova, Alex P. Kindwall, Xavier Lee, Arnold K. Liao, Mitch Lok, Shujun Luo, John W. Martin, Paul McNitt, Keith W. Moon, Joe W. Mullens, Michael J. O’Neill, Omead Ostadan, Lambros L. Paraschos, Alger C. Pike, D. Chris Pinkard, Daniel P. Pliskin, Joe Podhasky, Victor J. Quijano, Rithy K. Roth, Eli Rusman, Josefina M. Seoane, Mitch K. Shiver, Steven W. Short, Ning L. Sizto, Johannes P. Sluis, Eric J. Spence, Yuli Verhovsky, Selene M. Virk, Suzanne Wakelin, Gregory C. Walcott, Juying Yan, Ling Yau, Mike Zuerlein, John S. West, Frank L. Oaks & Peter L. Lundberg - The Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Wellcome Trust Genome Campus, Hinxton, Cambridge CB10 1SA, UK.,

Heng Li, Aylwyn Scally, Klaudia Walter, Nigel P. Carter, Zemin Ning, Bee Ling Ng, Jane Rogers, Matthew E. Hurles & Richard Durbin - Manteia Predictive Medicine S.A. Zone Industrielle, Coinsins, CH-1267, Switzerland.,

Milan Fedurco, Anthony Romieu & Gerardo Turcatti - Illumina Inc., Corporate Headquarters, 9883 Towne Centre Drive, San Diego, California 92121, USA.,

Kimberley J. Gietzen, Marc A. Laurent, Cynthia T. Lawley & Omead Ostadan - National Human Genome Research Institute, National Institutes of Health, 41 Center Drive, MSC 2132, 9000 Rockville Pike, Bethesda, Maryland 20892-2132, USA.,

Nancy F. Hansen & James C. Mullikin

Authors

- David R. Bentley

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Shankar Balasubramanian

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Harold P. Swerdlow

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Geoffrey P. Smith

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - John Milton

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Clive G. Brown

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Kevin P. Hall

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Dirk J. Evers

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Colin L. Barnes

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Helen R. Bignell

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Jonathan M. Boutell

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Jason Bryant

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Richard J. Carter

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - R. Keira Cheetham

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Anthony J. Cox

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Darren J. Ellis

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Michael R. Flatbush

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Niall A. Gormley

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Sean J. Humphray

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Leslie J. Irving

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Mirian S. Karbelashvili

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Scott M. Kirk

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Heng Li

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Xiaohai Liu

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Klaus S. Maisinger

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Lisa J. Murray

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Bojan Obradovic

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Tobias Ost

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Michael L. Parkinson

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Mark R. Pratt

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Isabelle M. J. Rasolonjatovo

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Mark T. Reed

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Roberto Rigatti

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Chiara Rodighiero

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Mark T. Ross

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Andrea Sabot

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Subramanian V. Sankar

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Aylwyn Scally

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Gary P. Schroth

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Mark E. Smith

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Vincent P. Smith

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Anastassia Spiridou

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Peta E. Torrance

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Svilen S. Tzonev

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Eric H. Vermaas

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Klaudia Walter

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Xiaolin Wu

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Lu Zhang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Mohammed D. Alam

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Carole Anastasi

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Ify C. Aniebo

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - David M. D. Bailey

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Iain R. Bancarz

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Saibal Banerjee

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Selena G. Barbour

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Primo A. Baybayan

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Vincent A. Benoit

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Kevin F. Benson

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Claire Bevis

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Phillip J. Black

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Asha Boodhun

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Joe S. Brennan

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - John A. Bridgham

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Rob C. Brown

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Andrew A. Brown

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Dale H. Buermann

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Abass A. Bundu

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - James C. Burrows

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Nigel P. Carter

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Nestor Castillo

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Maria Chiara E. Catenazzi

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Simon Chang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - R. Neil Cooley

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Natasha R. Crake

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Olubunmi O. Dada

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Konstantinos D. Diakoumakos

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Belen Dominguez-Fernandez

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - David J. Earnshaw

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Ugonna C. Egbujor

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - David W. Elmore

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Sergey S. Etchin

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Mark R. Ewan

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Milan Fedurco

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Louise J. Fraser

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Karin V. Fuentes Fajardo

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - W. Scott Furey

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - David George

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Kimberley J. Gietzen

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Colin P. Goddard

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - George S. Golda

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Philip A. Granieri

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - David E. Green

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - David L. Gustafson

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Nancy F. Hansen

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Kevin Harnish

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Christian D. Haudenschild

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Narinder I. Heyer

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Matthew M. Hims

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Johnny T. Ho

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Adrian M. Horgan

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Katya Hoschler

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Steve Hurwitz

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Denis V. Ivanov

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Maria Q. Johnson

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Terena James

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - T. A. Huw Jones

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Gyoung-Dong Kang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Tzvetana H. Kerelska

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Alan D. Kersey

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Irina Khrebtukova

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Alex P. Kindwall

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Zoya Kingsbury

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Paula I. Kokko-Gonzales

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Anil Kumar

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Marc A. Laurent

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Cynthia T. Lawley

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Sarah E. Lee

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Xavier Lee

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Arnold K. Liao

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Jennifer A. Loch

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Mitch Lok

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Shujun Luo

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Radhika M. Mammen

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - John W. Martin

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Patrick G. McCauley

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Paul McNitt

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Parul Mehta

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Keith W. Moon

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Joe W. Mullens

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Taksina Newington

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Zemin Ning

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Bee Ling Ng

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Sonia M. Novo

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Michael J. O’Neill

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Mark A. Osborne

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Andrew Osnowski

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Omead Ostadan

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Lambros L. Paraschos

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Lea Pickering

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Andrew C. Pike

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Alger C. Pike

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - D. Chris Pinkard

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Daniel P. Pliskin

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Joe Podhasky

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Victor J. Quijano

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Come Raczy

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Vicki H. Rae

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Stephen R. Rawlings

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Ana Chiva Rodriguez

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Phyllida M. Roe

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - John Rogers

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Maria C. Rogert Bacigalupo

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Nikolai Romanov

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Anthony Romieu

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Rithy K. Roth

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Natalie J. Rourke

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Silke T. Ruediger

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Eli Rusman

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Raquel M. Sanches-Kuiper

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Martin R. Schenker

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Josefina M. Seoane

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Richard J. Shaw

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Mitch K. Shiver

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Steven W. Short

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Ning L. Sizto

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Johannes P. Sluis

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Melanie A. Smith

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Jean Ernest Sohna Sohna

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Eric J. Spence

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Kim Stevens

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Neil Sutton

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Lukasz Szajkowski

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Carolyn L. Tregidgo

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Gerardo Turcatti

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Stephanie vandeVondele

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Yuli Verhovsky

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Selene M. Virk

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Suzanne Wakelin

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Gregory C. Walcott

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Jingwen Wang

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Graham J. Worsley

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Juying Yan

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Ling Yau

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Mike Zuerlein

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Jane Rogers

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - James C. Mullikin

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Matthew E. Hurles

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Nick J. McCooke

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - John S. West

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Frank L. Oaks

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Peter L. Lundberg

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - David Klenerman

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Richard Durbin

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Anthony J. Smith

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence toDavid R. Bentley.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

All authors at Illumina (see affiliations) are employees of Illumina Inc., a public company that develops and markets systems for genetic analysis.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

This file contains Supplementary Methods, Supplementary Figures S1-S21 with Legends and Supplementary Tables S1-S9. (PDF 2802 kb)

PowerPoint slides

Rights and permissions

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-Share Alike licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/), which permits distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. This license does not permit commercial exploitation, and derivative works must be licensed under the same or similar licence.

About this article

Cite this article

Bentley, D., Balasubramanian, S., Swerdlow, H. et al. Accurate whole human genome sequencing using reversible terminator chemistry.Nature 456, 53–59 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07517

- Received: 24 June 2008

- Accepted: 02 October 2008

- Issue Date: 06 November 2008

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07517