Subgroup-specific structural variation across 1,000 medulloblastoma genomes (original) (raw)

Main

Brain tumours are the most common cause of childhood oncological death, and medulloblastoma is the most common malignant paediatric brain tumour. Current medulloblastoma therapy including surgical resection, whole-brain and spinal cord radiation, and aggressive chemotherapy supplemented by bone marrow transplant yields five-year survival rates of 60–70%1. Survivors are often left with significant neurological, intellectual and physical disabilities secondary to the effects of these nonspecific cytotoxic therapies on the developing brain2.

Recent evidence suggests that medulloblastoma actually comprises multiple molecularly distinct entities whose clinical and genetic differences may require separate therapeutic strategies3,4,5,6. Four principal subgroups of medulloblastoma have been identified: WNT, SHH, Group 3 and Group 4 (ref. 7), and there is preliminary evidence for clinically significant subdivisions of the subgroups3,7,8. Rational, targeted therapies based on genetics are not currently in use for medulloblastoma, although inhibitors of the Sonic Hedgehog pathway protein Smoothened have shown early promise9. Actionable targets for WNT, Group 3 and Group 4 tumours have not been identified4,10. Sanger sequencing of 22 medulloblastoma exomes revealed on average only 8 single nucleotide variants (SNVs) per tumour11. Some SNVs were subgroup-restricted (PTCH1, CTNNB1), whereas others occurred across subgroups (TP53, MLL2). We proposed that the observed intertumoural heterogeneity might have underpowered prior attempts to discover targets for rational therapy.

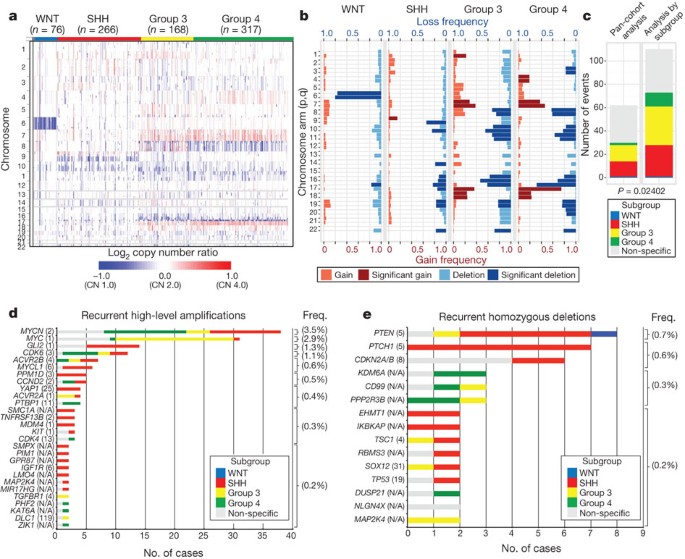

The Medulloblastoma Advanced Genomics International Consortium (MAGIC) consisting of scientists and physicians from 46 cities across the globe gathered more than 1,200 medulloblastomas which were studied by SNP arrays (n = 1,239; Fig. 1a, Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Tables 1–3). Medulloblastoma subgroup affiliation of 827 cases was determined using a custom nanoString-based RNA assay (Supplementary Fig. 2)12. Disparate patterns of broad cytogenetic gain and loss were observed across the subgroups (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Figs 3, 7, 8, 10 and 11). Analysis of the entire cohort using GISTIC2 (ref. 13) to discover significant ‘driver’ events delineated 62 regions of recurrent SCNA (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Tables 4 and 5); analysis by subgroup increased sensitivity such that 110 candidate ‘driver’ SCNAs were identified, most of which are subgroup-enriched (Fig. 1c–e and Supplementary Table 6).

Figure 1: Genomic heterogeneity of medulloblastoma subgroups.

a, The medulloblastoma genome classified by subgroup. b, Frequency and significance (Q value ≤ 0.1) of broad cytogenetic events across medulloblastoma subgroups. c, Significant regions of focal SCNA identified by GISTIC2 in either pan-cohort or subgroup-specific analyses. d, e, Recurrent high-level amplifications (d, segmented copy number (CN) ≥ 5) and homozygous deletions (e, segmented CN ≤ 0.7) in medulloblastoma. The number of genes mapping to the GISTIC2 peak region (where applicable) is listed in brackets after the suspected driver gene, as is the frequency of each event.

Twenty-eight regions of recurrent high-level amplification (copy number ≥ 5) were identified (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Table 7). The most prevalent amplifications affected members of the MYC family with MYCN predominantly amplified in SHH and Group 4, MYC in Group 3, and MYCL1 in SHH medulloblastomas. Multiple genes/regions were exclusively amplified in SHH, including GLI2, MYCL1, PPM1D, YAP1 and MDM4 (Fig. 1d). Recurrent homozygous deletions were exceedingly rare, with only 15 detected across 1,087 tumours (Fig. 1e). Homozygous deletions targeting known tumour suppressors PTEN, PTCH1 and CDKN2A/B were the most common, all enriched in SHH cases (Fig. 1e and Supplementary Table 7). Novel homozygous deletions included KDM6A, a histone-lysine demethylase deleted in Group 4. A custom nanoString CodeSet was used to verify 24 significant regions of gain across 192 MAGIC cases, resulting in a verification rate of 90.9% (Supplementary Fig. 5). We conclude that SCNAs in medulloblastoma are common, and are predominantly subgroup-enriched.

Subgroup-specific SCNAs in medulloblastoma

WNT medulloblastoma genomes are impoverished of recurrent focal regions of SCNA, exhibiting no significant regions of deletion and only a small subset of focal gains found at comparable frequencies in non-WNT tumours (Supplementary Figs 4, 6 and Supplementary Table 8). CTNNB1 mutational screening confirmed canonical exon 3 mutations in 63 out of 71 (88.7%) WNT tumours, whereas monosomy 6 was detected in 58 out of 76 (76.3%) (Supplementary Fig. 6; Supplementary Table 9). Four WNT tumours (4/71; 5.6%) had neither CTNNB1 mutation nor monosomy 6, but maintained typical WNT expression signatures. Given the size of our cohort and the resolution of the platform, we conclude that there are no frequent, targetable SCNAs for WNT medulloblastoma.

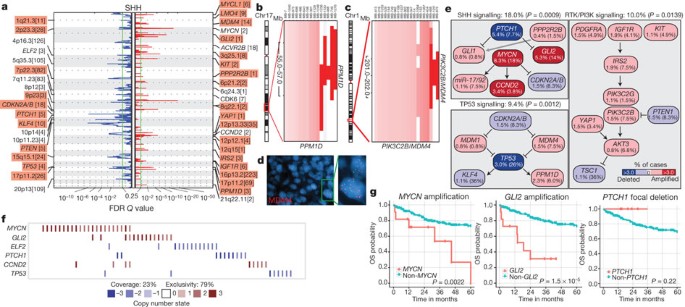

SHH tumours exhibit multiple significant focal SCNAs (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Figs 12, 15, 16 and Supplementary Tables 10 and 11). SHH enriched/restricted SCNAs included amplification of GLI2 and deletion of PTCH1 (Fig. 2a, e, f)10. MYCN and CCND2 were among the most frequently amplified genes in SHH (Supplementary Table 6), but were also altered in non-SHH cases. Genes upregulated in SHH tumours (that is, SHH signature genes) are significantly over-represented among the genes focally amplified in SHH tumours (P = 0.001–0.02, permutation tests; Supplementary Fig. 9). Recurrent amplification of SHH signature genes has clinical implications, as amplification of downstream transcriptional targets could mediate resistance to upstream SHH pathway inhibitors14.

Figure 2: Genomic alterations affect core signalling pathways in SHH medulloblastoma.

a, GISTIC2 significance plot of amplifications (red) and deletions (blue) observed in SHH. The number of genes mapping to each significant region are included in brackets and regions enriched in SHH are shaded red. b, c, Recurrent amplifications of PPM1D (b) and PIK3C2B/MDM4 (c) are restricted to SHH. d, Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) validation of MDM4 amplification. e, SHH signalling, TP53 signalling and RTK/PI3K signalling represent the core pathways genomically targeted in SHH. P values indicate the prevalence with which the respective pathway is targeted in SHH versus non-SHH cases (Fisher’s exact test). Frequencies of focal and broad (parentheses) SCNAs are listed. f, Mutual exclusivity analysis of focal SCNAs in SHH. g, Clinical implications of SCNAs affecting MYCN, GLI2 or PTCH1 in SHH (log-rank tests).

Novel, SHH-enriched SCNAs included components of TP53 signalling, including amplifications of MDM4 and PPM1D, and focal deletions of TP53 (Fig. 2a–e). Targetable events, including amplifications of IGF signalling genes IGF1R and IRS2, PI3K genes PIK3C2G and PIK3C2B, and deletion of PTEN were restricted to SHH tumours (Fig. 2a, c, e). Importantly, focal events affecting genes in the SHH pathway were largely mutually exclusive and prognostically significant (Fig. 2f, g). Many of the recurrent, targetable SCNAs identified in SHH medulloblastoma (IGF1R, KIT, MDM4, PDGFRA, PIK3C2G, PIK2C2B and PTEN) have already been targeted with small molecules for treatment of other malignancies, which might allow rapid translation for targeted therapy of subsets of SHH patients (Supplementary Table 16). Novel SHH targets identified here are excellent candidates for combinatorial therapy with Smoothened inhibitors, to avoid the resistance encountered in both humans and mice9,14,15.

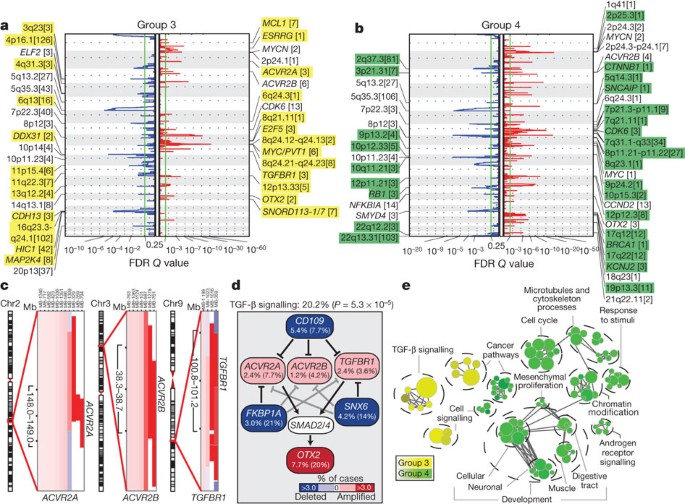

Group 3 and Group 4 medulloblastomas have generic names as comparatively little is known about their genetic basis, and no targets for rational therapy have been identified7. MYC amplicons are largely restricted to Group 3, whereas MYCN amplicons are seen in Group 4 and SHH tumours (Fig. 1d)3,4. Indeed, MYC and MYCN loci comprise the most significant regions of amplification observed in Group 3 and Group 4, respectively (Fig. 3a, b, Supplementary Figs 13, 14, 17–20 and Supplementary Tables 12–15). Group 3 MYC amplicons were mutually exclusive from those affecting the known medulloblastoma oncogene OTX2 (ref. 16) and were highly prognostic (Supplementary Fig. 21)3,16. Type II activin receptors, ACVR2A and ACVR2B and family member TGFBR1 are highly amplified in Group 3 tumours, indicating deregulation of TGF-β signalling as a driver event in Group 3 (Fig. 3c–e and Supplementary Fig. 22). The Group 3-enriched medulloblastoma oncogene OTX2 is a prominent target of TGF-β signalling in the developing nervous system17 and TGF-β pathway inhibitors CD109 (ref. 18), FKBP1A (refs 19 and 20) and SNX6 (ref. 20) are recurrently deleted in Group 3 (Fig. 3a, d). SCNAs in TGF-β pathway genes were heavily enriched in Group 3 (P = 5.37 × 10−5, Fisher’s exact test) and found in at least 20.2% of cases, indicating that TGF-β signalling represents the first rational target for this poor prognosis subgroup (Fig. 3d). Similarly, novel deletions affecting regulators of the NF-κB pathway, including NFKBIA (ref. 21) and USP4 (ref. 22) were identified in Group 4 (Supplementary Fig. 23), proposing that NF-κB signalling may represent a rational Group 4 therapeutic target.

Figure 3: The genomic landscape of Group 3 and Group 4 medulloblastoma.

a, b, GISTIC2 plots depicting significant SCNAs in Group 3 (a) and Group 4 (b) with subgroup-enriched regions shaded in yellow and green, respectively. c, Recurrent amplifications targeting type II (ACVR2A and ACVR2B) and type I (TGFBR1) activin receptors in Group 3. d, Recurrent SCNAs affecting the TGF-β pathway in Group 3 (P = 5.73 × 10−5, Fisher’s exact test). Frequencies of focal and broad (parentheses) SCNAs are listed. e, Enrichment map of gene sets affected by SCNAs in Group 3 versus Group 4.

Network analysis of Group 3 and Group 4 SCNAs illustrates the different pathways over-represented in each subgroup. Only TGF-β signalling is unique to Group 3 (Fig. 3e). In contrast, cell-cycle control, chromatin modification and neuronal development are all Group 4-enriched. Cumulatively, the dismal prognosis of Group 3 patients, the lack of published targets for rational therapy, and the prior targeting of TGF-β signalling in other diseases suggest that TGF-β may represent an appealing target for Group 3 rational therapies (Supplementary Table 16).

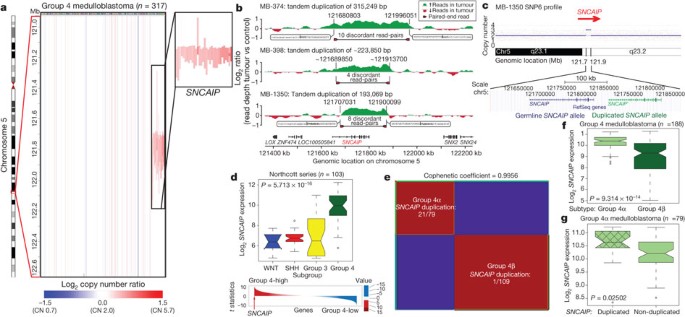

SNCAIP tandem duplication is common in Group 4

Although Group 4 is the most prevalent medulloblastoma subgroup, its pathogenesis remains poorly understood. The most frequent SCNA observed in Group 4 (33/317; 10.4%) is a recurrent region of single copy gain on chr5q23.2 targeting a single gene, SNCAIP (synuclein, alpha interacting protein) (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 24). SNCAIP, encodes synphilin-1, which binds to α-synuclein to promote the formation of Lewy bodies in the brains of patients with Parkinson’s disease23,24. Additionally, rare germline mutations of SNCAIP have been described in Parkinson’s families25. Large insert, mate-pair, whole-genome sequencing (WGS) demonstrates that SNCAIP copy number gains arise from tandem duplication of a truncated SNCAIP (lacking non-coding exon 1), inserted telomeric to the germline SNCAIP allele (Fig. 4b, c and Supplementary Fig. 25). Affymetrix SNP6 array profiling of patient-matched germline material confirmed that SNCAIP duplications are somatic (Supplementary Fig. 26), and subsequent whole-transcriptome sequencing (RNA-Seq) of select Group 4 cases (n = 5) verified that SNCAIP is the only gene expressed in the duplicated region (Supplementary Fig. 27). Analysis of published copy number profiles for 3,131 primary tumours26 and 947 cancer cell lines27 (total of 4,078 cases) revealed only four cases with apparent duplication of SNCAIP, all of which were inferred as Group 4 medulloblastomas (data not shown). We conclude that SNCAIP duplication is a somatic event highly specific to Group 4 medulloblastoma.

Figure 4: Tandem duplication of SNCAIP defines a novel subtype of Group 4.

a, Highly recurrent, focal, single-copy gain of SNCAIP in Group 4. b, Paired-end mapping verifies recurrent tandem duplication of SNCAIP in Group 4. c, Schematic representation of SNCAIP tandem duplication. d, SNCAIP is a Group 4 signature gene. Upper panel, SNCAIP expression across subgroups in a published series of 103 primary medulloblastomas. Error bars depict the minimum and maximum values, excluding outliers. Lower panel, SNCAIP ranks among the top 1% (rank, 39th out of 16,758) of highly expressed genes in Group 4. e, NMF consensus clustering of 188 expression-profiled Group 4 tumours supports two transcriptionally distinct subtypes designated 4α and 4β (cophenetic coefficient = 0.9956). 21 out of 22 SNCAIP duplicated cases belong to Group 4α (P = 3.12 × 10−8, Fisher’s exact test). f, SNCAIP expression is significantly elevated in Group 4α versus 4β (P = 9.31 × 10−14, Mann–Whitney test). g, Group 4α cases harbouring SNCAIP duplication exhibit a ∼1.5-fold increase in SNCAIP expression. f, g, Error bars depict the minimum and maximum values, excluding outliers.

Re-analysis of 499 published medulloblastoma expression profiles confirmed that SNCAIP is one of the most highly upregulated Group 4 signature genes (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. 28). Profiling of 188 Group 4 tumours on expression microarrays followed by consensus non-negative matrix factorization (NMF) clustering delineates two subtypes of Group 4 (4α and 4β; Fig. 4e and Supplementary Fig. 29). Strikingly, 21 out of 22 SNCAIP duplicated cases belonged to Group 4α (P = 3.12 × 10−8, Fisher’s exact test). SNCAIP is more highly expressed in Group 4α than 4β (Fig. 4f), and 4α samples with tandem duplication showed approximately 1.5-fold increased expression, consistent with gene dosage (Fig. 4g and Supplementary Figs 35 and 36). Group 4α exhibits a relatively balanced genome compared to 4β (Supplementary Figs 30–32), and several 4α cases harbour SNCAIP duplication in conjunction with i17q and no other SCNAs (Supplementary Fig. 33). Importantly, SNCAIP duplications are mutually exclusive from other prominent SCNAs in Group 4, including MYCN and CDK6 amplifications (Supplementary Fig. 34).

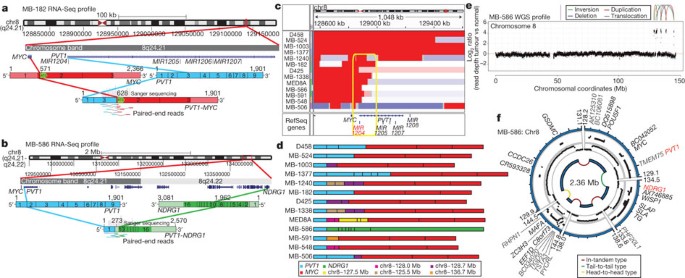

PVT1 fusions arise via chromothripsis in Group 3

Although recurrent gene fusions have recently been discovered in solid tumours, none have been reported in medulloblastoma. RNA-Seq of Group 3 tumours (n = 13) identified two independent gene fusions in two different tumours (MB-182 and MB-586), both involving the 5′ end of PVT1, a non-coding gene frequently co-amplified with MYC in Group 3 (Fig. 5a, b, Supplementary Fig. 37 and Supplementary Tables 17 and 18). Sanger sequencing confirmed a fusion transcript consisting of exons 1 and 3 of PVT1 fused to the coding sequence of MYC (exons 2 and 3) in MB-182, and a fusion involving PVT1 exon 1 fused to the 3′ end of NDRG1 in MB-586 (Fig. 5a, b).

Figure 5: Identification of frequent _PVT1_-MYC fusion genes in Group 3.

a, b, RNA-Seq identifies multiple fusion transcripts driven by PVT1 in Group 3. Schematics depict the structures of verified _PVT1_-MYC (a) and _PVT1_-NDRG1 (b) fusion genes. c, Heat map of the MYC/PVT1 locus showing a subset of 13 _MYC_-amplified Group 3 cases subsequently verified to exhibit PVT1 gene fusions (shown in d). Yellow box highlights the common breakpoint affecting the first exon/intron of PVT1, including miR-1204. d, Summary of PVT1 fusion transcripts identified in Group 3. e, f, WGS confirms complex patterns of rearrangement on chr8q24 in PVT1 fusion (+) Group 3.

Group 3 copy number data at the MYC/PVT1 locus indicated that additional samples might harbour PVT1 gene fusions (Fig. 5c). PCR with reverse transcription (RT–PCR) profiling of select Group 3 cases confirmed _PVT1_-MYC fusions in at least 60% (12/20) of _MYC_-amplified cases (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Table 19). Fusion transcripts included many other portions of chr8q, with up to four different genomic loci mapping to a single transcript, a pattern reminiscent of chromothripsis28,29 (Fig. 5d). WGS performed on four _MYC_-amplified Group 3 tumours harbouring PVT1 fusion transcripts identified a series of complex genomic rearrangements on chr8q (Fig. 5e, f, Supplementary Fig. 38 and Supplementary Tables 20 and 21). Chromosome 8 copy number profile for MB-586 (PVT1-NDRG1) derived from WGS showed that PVT1 and NDRG1 are structurally linked, as predicted by RNA-Seq, and several adjacent regions of 8q24 were extensively rearranged (Fig. 5e, f and Supplementary Table 21). Monte Carlo simulation suggests that this fragmented 8q amplicon arose through chromothripsis, a process of erroneous DNA repair following a single catastrophic event in which a chromosome is shattered into many pieces (Supplementary Fig. 39). Further examination of our copy number data set revealed rare examples of chromothripsis across subgroups (Supplementary Fig. 40), with only chr8 in Group 3 demonstrating statistically significant, region-specific chromothripsis (Q = 0.0004, false discovery rate (FDR)-corrected Fisher’s exact test). Among Group 3 tumours, the occurrence of chr8q chromothripsis is correlated with deletion of chr17p (location of TP53; data not shown), in keeping with the association of loss of TP53 and chromothripsis recently described in medulloblastoma (P = 0.0199, Fisher’s exact test)28. Whereas the PVT1 locus has been suggested to be a genomically fragile site, we observe that the majority of _MYC_-amplified Group 3 tumours harbour PVT1 fusions that arise through a process consistent with chromothripsis.

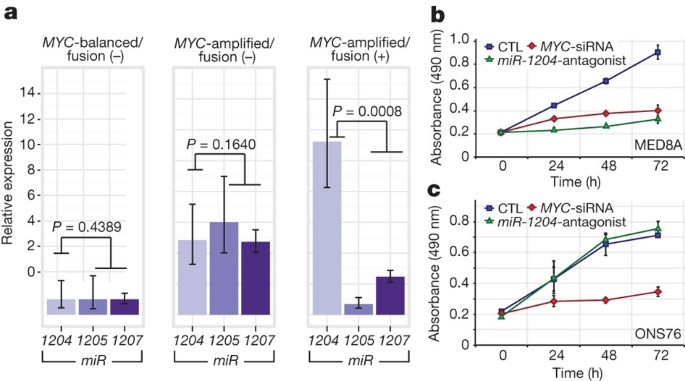

PVT1 is a non-coding host gene for four microRNAs, miR-1204_–_miR-1207. Previous studies have implicated miR-1204 as a candidate oncogene that enhances oncogenesis in combination with MYC30,31. PVT1 fusions identified in this study involve only PVT1 exon 1 and miR-1204. Importantly, miR-1204, but not the adjacent miR-1205 and miR-1206, is expressed at a higher level in _PVT1_-MYC fusion (+) Group 3 tumours compared to fusion (−) cases (P = 0.0008, Mann–Whitney test; Fig. 6a). To evaluate whether aberrant expression of miR-1204 contributes to the malignant phenotype, we inhibited miR-1204 in MED8A cells, a Group 3 medulloblastoma cell line with a confirmed _PVT1_-MYC fusion (Fig. 5d). Antagomir-mediated RNA interference of miR-1204 had a pronounced effect on MED8A growth (Fig. 6b). A comparable reduction in proliferative capacity was achieved with knockdown of MYC. Conversely, the medulloblastoma cell line ONS76 exhibits neither MYC amplification nor a detectable _PVT1_-MYC fusion gene, and knockdown of miR-1204 had no effect in this line (Fig. 6c).

Figure 6: Functional synergy between miR-1204 and MYC secondary to _PVT1_-MYC fusion.

a, Quantitative RT–PCR of _PVT1_-encoded microRNAs confirms upregulation of miR-1204 in _PVT1_-MYC fusion (+) Group 3 tumours. _MYC_-balanced/fusion (−), n = 4; _MYC_-amplified/fusion (−), n = 6; _MYC_-amplified/fusion (+), n = 8. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (s.e.m.) and reflect variability among samples. b, c, Knockdown of miR-1204 attenuates the proliferative capacity of _PVT1_-MYC fusion (+) MED8A medulloblastoma cells (b) but has no effect on fusion (−) ONS76 cells (c). Error bars represent the standard deviation (s.d.) of triplicate experiments. CTL, control.

PVT1 has been reported previously in fusion transcripts with a number of partners30,32,33. The most prevalent form of the _PVT1_-MYC fusion in Group 3 tumours lacks the first, non-coding exon of MYC, similar to forms of MYC that have been described in Burkitt’s lymphoma34 (Fig. 5a, d). The PVT1 promoter contains two non-canonical E-boxes and can be activated by MYC31. This indicates a positive feedback model where MYC can reinforce its own expression from the PVT1 promoter in _PVT1_-MYC fusion (+) tumours. Indeed, knockdown of MYC alone in MED8A cells resulted in diminished expression of both MYC and miR-1204, suggesting MYC may positively regulate PVT1 (that is, miR-1204) expression in medulloblastoma cells (Supplementary Fig. 41).

Discussion

Medulloblastomas have few SNVs compared to many adult epithelial malignancies11, whereas SCNAs seem to be quite common. Medulloblastoma is a heterogeneous disease7, thereby requiring large cohorts to detect subgroup-specific events. Through the accumulation of >1,200 medulloblastomas in MAGIC, we have identified novel and significant SCNAs. Many of the significant SCNAs are subgroup-restricted, highly supporting their role as driver events in their respective subgroups.

Expression of synphilin-1 in neuronal cells results in decreased cell doubling time35, decreased caspase-3 activation36, decreased TP53 transcriptional activity and messenger RNA levels, and decreased apoptosis37. Synphilin-1 is ubiquitinated by parkin, which is encoded by the hereditary Parkinson’s disease gene PARK2 (ref. 24), a candidate tumour suppressor gene38. Whereas patients with Parkinson’s disease have an overall decreased risk of cancer, they may have an increased incidence of brain tumours39,40. As tandem duplications of SNCAIP are highly recurrent, stereotypical, subgroup-restricted, affect only a single gene, and as _SNCAIP_-duplicated tumours have few if any other SCNAs, SNCAIP is a probable driver gene, and merits investigation as a target for therapy of Group 4α. Similarly, PVT1 fusion genes are highly recurrent, restricted to Group 3, arise through a chromothripsis-like process, and are the first recurrent translocation reported in medulloblastoma.

We identify a number of highly targetable, recurrent, subgroup-specific SCNAs that could form the basis for future clinical trials (that is, PI3K signalling in SHH, TGF-β signalling in Group 3, and NF-κB signalling in Group 4). Activation of these pathways through alternative, currently unknown genetic and epigenetic events could increase the percentage of patients amenable to targeted therapy. We also identify a number of highly ‘druggable’ events that occur in a minority of cases. The cooperative, global approach of the MAGIC consortium has allowed us to overcome the barrier of intertumoural heterogeneity in an uncommon paediatric tumour, and to identify the relevant and targetable SCNAs for the affected children.

Methods Summary

All patient samples were obtained with consent as outlined by individual institutional review boards. Genomic DNA was prepared, processed and hybridized to Affymetrix SNP6 arrays according to manufacturer’s instructions. Raw copy number estimates were obtained in dChip, followed by CBS segmentation in R. SCNAs were identified using GISTIC2 (ref. 13). Driver genes within SCNAs were inferred by integrating matched expressions, literature evidence and other data sets. Pathway enrichment of SCNAs was analysed with g:Profiler and visualized in Cytoscape using Enrichment Map. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) was performed as described previously8,10. Medulloblastoma subgroup was assigned using a custom nanoString CodeSet as described previously12. Tandem duplication of SNCAIP was confirmed by paired-end mapping as previously reported28. RNA was extracted, processed and hybridized to Affymetrix Gene 1.1 ST Arrays as recommended by the manufacturer. Consensus NMF clustering was performed in GenePattern. Gene fusions were identified from RNA-Seq data using Trans-ABySS. Medulloblastoma cell lines were maintained as described10. Proliferation assays were performed with the Promega CellTiter 96 Assay. Additional methods are detailed in full in Supplementary Methods.

Accession codes

Primary accessions

Gene Expression Omnibus

Data deposits

SNP6 copy number and gene expression array data have been deposited at the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) as a GEO SuperSeries under accession number GSE37385. Whole genome and transcriptome sequencing data have been deposited at the European Genome-phenome Archive (EGA; https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ega/) hosted by the EBI, under accession number EGAD00001000158.

References

- Gajjar, A. et al. Risk-adapted craniospinal radiotherapy followed by high-dose chemotherapy and stem-cell rescue in children with newly diagnosed medulloblastoma (St Jude Medulloblastoma-96): long-term results from a prospective, multicentre trial. Lancet Oncol. 7, 813–820 (2006)

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Mabbott, D. J. et al. Serial evaluation of academic and behavioral outcome after treatment with cranial radiation in childhood. J. Clin. Oncol. 23, 2256–2263 (2005)

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Cho, Y. J. et al. Integrative genomic analysis of medulloblastoma identifies a molecular subgroup that drives poor clinical outcome. J. Clin. Oncol. 29, 1424–1430 (2011)

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Northcott, P. A. et al. Medulloblastoma comprises four distinct molecular variants. J. Clin. Oncol. 29, 1408–1414 (2011)

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Remke, M. et al. FSTL5 is a marker of poor prognosis in non-WNT/non-SHH medulloblastoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 29, 3852–3861 (2011)

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Northcott, P. A., Korshunov, A., Pfister, S. M. & Taylor, M. D. The clinical implications of medulloblastoma subgroups. Nature Rev. Neurol. 8, 340–351 (2012)

Article CAS Google Scholar - Taylor, M. D. et al. Molecular subgroups of medulloblastoma: the current consensus. Acta Neuropathol. 123, 465–472 (2011)

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Northcott, P. A. et al. Pediatric and adult sonic hedgehog medulloblastomas are clinically and molecularly distinct. Acta Neuropathol. 122, 231–240 (2011)

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Rudin, C. M. et al. Treatment of medulloblastoma with hedgehog pathway inhibitor GDC-0449. N. Engl. J. Med. 361, 1173–1178 (2009)

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Northcott, P. A. et al. Multiple recurrent genetic events converge on control of histone lysine methylation in medulloblastoma. Nature Genet. 41, 465–472 (2009)

Article MathSciNet CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Parsons, D. W. et al. The genetic landscape of the childhood cancer medulloblastoma. Science 331, 435–439 (2011)

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Northcott, P. A. et al. Rapid, reliable, and reproducible molecular sub-grouping of clinical medulloblastoma samples. Acta Neuropathol. 123, 615–626 (2012)

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Mermel, C. H. et al. GISTIC2.0 facilitates sensitive and confident localization of the targets of focal somatic copy-number alteration in human cancers. Genome Biol. 12, R41 (2011)

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Buonamici, S. et al. Interfering with resistance to smoothened antagonists by inhibition of the PI3K pathway in medulloblastoma. Sci. Transl. Med. 2, 51ra70 (2010)

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Yauch, R. L. et al. Smoothened mutation confers resistance to a hedgehog pathway inhibitor in medulloblastoma. Science 326, 572–574 (2009)

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Adamson, D. C. et al. OTX2 is critical for the maintenance and progression of Shh-independent medulloblastomas. Cancer Res. 70, 181–191 (2010)

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Jia, S., Wu, D., Xing, C. & Meng, A. Smad2/3 activities are required for induction and patterning of the neuroectoderm in zebrafish. Dev. Biol. 333, 273–284 (2009)

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Bizet, A. A. et al. The TGF-β co-receptor, CD109, promotes internalization and degradation of TGF-β receptors. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1813, 742–753 (2011)

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Wang, T., Donahoe, P. K. & Zervos, A. S. Specific interaction of type I receptors of the TGF-beta family with the immunophilin FKBP-12. Science 265, 674–676 (1994)

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Parks, W. T. et al. Sorting nexin 6, a novel SNX, interacts with the transforming growth factor-β family of receptor serine-threonine kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 19332–19339 (2001)

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Bredel, M. et al. NFKBIA deletion in glioblastomas. N. Engl. J. Med. 364, 627–637 (2011)

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Xiao, N. et al. Ubiquitin-specific protease 4 (USP4) targets TRAF2 and TRAF6 for deubiquitination and inhibits TNFα-induced cancer cell migration. Biochem. J. 441, 979–986 (2012)

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Engelender, S. et al. Synphilin-1 associates with α-synuclein and promotes the formation of cytosolic inclusions. Nature Genet. 22, 110–114 (1999)

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Chung, K. K. et al. Parkin ubiquitinates the α-synuclein-interacting protein, synphilin-1: implications for Lewy-body formation in Parkinson disease. Nature Med. 7, 1144–1150 (2001)

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Marx, F. P. et al. Identification and functional characterization of a novel R621C mutation in the synphilin-1 gene in Parkinson’s disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 12, 1223–1231 (2003)

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Beroukhim, R. et al. The landscape of somatic copy-number alteration across human cancers. Nature 463, 899–905 (2010)

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Barretina, J. et al. The Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia enables predictive modelling of anticancer drug sensitivity. Nature 483, 603–607 (2012)

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Rausch, T. et al. Genome sequencing of pediatric medulloblastoma links catastrophic DNA rearrangements with TP53 mutations. Cell 148, 59–71 (2012)

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Stephens, P. J. et al. Massive genomic rearrangement acquired in a single catastrophic event during cancer development. Cell 144, 27–40 (2011)

Article MathSciNet CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Shtivelman, E. & Bishop, J. M. The PVT gene frequently amplifies with MYC in tumor cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 9, 1148–1154 (1989)

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Carramusa, L. et al. The PVT-1 oncogene is a Myc protein target that is overexpressed in transformed cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 213, 511–518 (2007)

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Shtivelman, E. & Bishop, J. M. Effects of translocations on transcription from PVT . Mol. Cell. Biol. 10, 1835–1839 (1990)

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Pleasance, E. D. et al. A small-cell lung cancer genome with complex signatures of tobacco exposure. Nature 463, 184–190 (2010)

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Hann, S. R., King, M. W., Bentley, D. L., Anderson, C. W. & Eisenman, R. N. A non-AUG translational initiation in c-myc exon 1 generates an N-terminally distinct protein whose synthesis is disrupted in Burkitt’s lymphomas. Cell 52, 185–195 (1988)

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Li, X. et al. Synphilin-1 exhibits trophic and protective effects against Rotenone toxicity. Neuroscience 165, 455–462 (2010)

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Smith, W. W. et al. Synphilin-1 attenuates neuronal degeneration in the A53T alpha-synuclein transgenic mouse model. Hum. Mol. Genet. 19, 2087–2098 (2010)

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Giaime, E. et al. Caspase-3-derived C-terminal product of synphilin-1 displays antiapoptotic function via modulation of the p53-dependent cell death pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 11515–11522 (2006)

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Veeriah, S. et al. Somatic mutations of the Parkinson’s disease-associated gene PARK2 in glioblastoma and other human malignancies. Nature Genet. 42, 77–82 (2010)

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Olsen, J. H. et al. Atypical cancer pattern in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Br. J. Cancer 92, 201–205 (2005)

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Moller, H., Mellemkjaer, L., McLaughlin, J. K. & Olsen, J. H. Occurrence of different cancers in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Br. Med. J. 310, 1500–1501 (1995)

Article CAS Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

M.D.T. is the recipient of a CIHR Clinician-Scientist Phase II award, and was formerly a Sontag Distinguished Scholar with funds from the Sontag Foundation. Funding is acknowledged from the Pediatric Brain Tumour Foundation (M.D.T. and J.T.R.), and the National Institutes of Health (CA159859 to M.D.T., R.W.R. and B.W.), The Canadian Cancer Society, Genome Canada, Genome BC, Terry Fox Research Institute, Ontario Institute for Cancer Research, Pediatric Oncology Group Ontario, Funds from ‘The Family of Kathleen Lorette’ and the Clark H. Smith Brain Tumour Centre, Montreal Children’s Hospital Foundation, Hospital for Sick Children: Sonia and Arthur Labatt Brain Tumour Research Centre, Chief of Research Fund, Cancer Genetics Program, Garron Family Cancer Centre, B.R.A.I.N. Child, CIHR (grant no. ATE-110814); the University of Toronto McLaughlin Centre, CIHR Institute of Cancer Research (grant no. AT1 – 112286) and C17 through the Advancing Technology Innovation through Discovery competition (Project Title: The Canadian Pediatric Cancer Genome Consortium: Translating next-generation sequencing technologies into improved therapies for high-risk childhood cancer). Canada’s Michael Smith Genome Sciences Centre is supported by the BC Cancer Foundation. J.R. is supported by The Children’s Discovery Institute. P.A.N. was supported by a Restracomp Fellowship (Hospital for Sick Children) and is currently a Roman-Herzog Postdoctoral Fellow (Hertie Foundation). Salary support for L.G. was provided by the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research through funding provided by the Government of Ontario. E.V.G.M. is supported by NIH grants CA86335, CA116804, CA138292, NCI contracts 28XS100 and 29XS193, the Southeastern Brain Tumour Foundation, and the Brain Tumour Foundation for Children. This study includes samples provided by the UK Children’s Cancer and Leukaemia Group (CCLG) as part of CCLG-approved biological study BS-2007-04. J.K. and S.P. were supported by a grant from the German Cancer Aid (109252). We thank C. Lu, K. Otaka and The Centre for Applied Genomics for technical assistance. We thank N. S. Devi and Z. Zhang for technical assistance. We thank D. Stoll for project management, S. Archer for technical writing, and P. Paroutis for artwork. The MAGIC project is part of the International Cancer Genome Consortium.

Author information

Author notes

- Paul A. Northcott and David J. H. Shih: These authors contributed equally to this work.

Authors and Affiliations

- Developmental & Stem Cell Biology Program, The Hospital for Sick Children, 101 College Street, TMDT-11-401M, Toronto, Ontario M5G 1L7, Canada.,

Paul A. Northcott, David J. H. Shih, John Peacock, Livia Garzia, A. Sorana Morrissy, Stephen Mack, Adrian Dubuc, Yuan Yao, Vijay Ramaswamy, Betty Luu, Adi Rolider, Florence M. G. Cavalli, Xin Wang, Marc Remke, Xiaochong Wu & Michael D. Taylor - Division of Pediatric Neurooncology, German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), Im Neuenheimer Feld 280, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany.,

Paul A. Northcott, Marcel Kool, David T. W. Jones & Stefan M. Pfister - Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathobiology, University of Toronto, Medical Sciences Buildings, 1 King’s College Circle, 6th Floor, Toronto, Ontario M5S 1A8, Canada.,

David J. H. Shih, John Peacock, Stephen Mack, Adrian Dubuc, Yuan Yao, Vijay Ramaswamy, Xin Wang & Michael D. Taylor - Genome Biology, European Molecular Biology Laboratory, Meyerhofstrasse 1, 69117 Heidelberg, Germany.,

Thomas Zichner, Adrian M. Stütz & Jan O. Korbel - Department of Neuropathology, CCU Neuropathology, German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), Im Neuenheimer Feld 220-221, University of Heidelberg, Im Neuenheimer Feld 224, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany.,

Andrey Korshunov - The Donnelly Centre, University of Toronto, 160 College Street, Room 602, Toronto, Ontario M5S 3E1, Canada.,

Jüri Reimand & Gary D. Bader - Department of Cancer Biology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, 450 Brookline Avenue, Boston, Massachusetts 02215, USA.,

Steven E. Schumacher & Rameen Beroukhim - Department of Medical Oncology, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, 450 Brookline Avenue, Boston, Massachusetts 02215, USA.,

Rameen Beroukhim & Matthew Meyerson - Department of Medicine, Harvard Medical School, 25 Shattuck Street, Boston, Massachusetts 02115, USA.,

Rameen Beroukhim - Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, 75 Francis Street, Boston, Massachusetts 02115, USA.,

Rameen Beroukhim - Cancer Program, Broad Institute, 7 Cambridge Center, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02142, USA.,

Rameen Beroukhim - Center for Cancer Genome Discovery, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, 450 Brookline Avenue, Boston, Massachusetts 02215, USA.,

Rameen Beroukhim - Pathology, St Jude Children’s Research Hospital, 262 Danny Thomas Place, Memphis, Tennessee 38105, USA.,

David W. Ellison - McLaughlin Centre and Department of Molecular Genetics, University of Toronto, 101 College Street, Toronto, Ontario M5G 1L7, Canada.,

Christian R. Marshall, Gary D. Bader & Stephen W. Scherer - The Centre for Applied Genomics and Program in Genetics and Genome Biology, The Hospital for Sick Children, 101 College Street, TMDT-14-701, Toronto, Ontario M5G 1L7, Canada.,

Anath C. Lionel & Stephen W. Scherer - Michael Smith Genome Sciences Centre, BC Cancer Agency, 100-570 West 7th Avenue, Vancouver, British Columbia V5Z 4S6, Canada.,

Readman Y. B. Chiu, Andy Chu, Eric Chuah, Richard D. Corbett, Gemma R. Hoad, Shaun D. Jackman, Yisu Li, Allan Lo, Karen L. Mungall, Ka Ming Nip, Jenny Q. Qian, Anthony G. J. Raymond, Nina Thiessen, Richard J. Varhol, Inanc Birol, Richard A. Moore, Andrew J. Mungall & Steven J. M. Jones - Michael Smith Genome Sciences Centre, BC Cancer Agency, 675 West 10th Avenue, Vancouver, British Columbia V5Z 1L3, Canada.,

Robert Holt & Marco A. Marra - Tumour Cell Biology, St Jude Children’s Research Hospital, 262 Danny Thomas Place, Memphis, Tennessee 38105, USA.,

Daisuke Kawauchi & Martine F. Roussel - Department of Pediatric Oncology, University Hospital Heidelberg, Im Neuenheimer Feld 430, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany.,

Hendrick Witt & Stefan M. Pfister - Departments of Hematology and Immunology, University Hospital Heidelberg, Im Neuenheimer Feld 430, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany.,

Hendrick Witt - Pediatric Clinical Trials Office, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, 405 Lexington Avenue, New York, New York 10174, USA.,

Africa Fernandez-L - Neurological Surgery, Vanderbilt Medical Center, T-4224 MCN, Nashville, Tennessee 37232-2380, USA.,

Anna M. Kenney & Reid C. Thompson - Cancer Biology, Vanderbilt Medical Center, 465 21st Avenue South, MRB III 6160, Nashville, Tennessee 37232-8550, USA.,

Anna M. Kenney - Sanford-Burnham Medical Research Institute, La Jolla, 92037, California, USA

Robert J. Wechsler-Reya - Department of Surgery, Division of Neurosurgery and Labatt Brain Tumour Research Centre, The Hospital for Sick Children, 555 University Avenue, Hill 1503, Toronto, Ontario M5G 1X8, Canada.,

Peter Dirks, James T. Rutka & Michael D. Taylor - Developmental & Stem Cell Biology Program, The Hospital for Sick Children, 101 College Street, TMDT-13-601, Toronto, Ontario M5G 1L7, Canada.,

Tzvi Aviv - Department of Pathology, The Children’s Memorial Health Institute, Aleja Dzieci Polskich 20, 04-730 Warsaw, Poland.,

Wieslawa A. Grajkowska - Department of Oncology, The Children’s Memorial Health Institute, Aleja Dzieci Polskich 20, 04-730 Warsaw, Poland.,

Marta Perek-Polnik - Institute of Neurology, Medical University of Vienna, AKH 4J, Waehringer Gürtel 18-20, A-1097 Vienna, Austria.,

Christine C. Haberler - INSERM U 830, Institut Curie, 26 rue d’Ulm, 75238 Paris Cedex 5, France.,

Olivier Delattre - Unit of Somatic Genetics, Institut Curie, 26 rue d’Ulm, 75238 Paris Cedex 5, France.,

Stéphanie S. Reynaud - Department of Pediatric Oncology, Institut Curie, 26 rue d’Ulm, 75248 Paris Cedex 5, France.,

François F. Doz - Pediatric Hematology and Oncology, CHUV University Hospital, 1011 Lausanne, Switzerland.,

Sarah S. Pernet-Fattet - Department of Neurosurgery, Division of Pediatric Neurosurgery, Seoul National University Children’s Hospital, 101 Daehak-Ro Jongno-Gu, Seoul 110-744, South Korea.,

Byung-Kyu Cho, Seung-Ki Kim & Kyu-Chang Wang - Head of Pediatrics, Cnopfsche Kinderklinik, Theodor-Kutzer-Ufer 1-3, 90419 Nuremberg, Germany.,

Wolfram Scheurlen - Departments of Pathology, Ophthalmology and Oncology, John Hopkins University School of Medicine, 720 Rutland Avenue, Ross Building 558, Baltimore, Maryland 21205, USA.,

Charles G. Eberhart - INSERM U1028, CNRS UMR5292, Centre de Recherche en Neurosciences, Université de Lyon, 69336 Lyon, France.,

Michelle Fèvre-Montange - Centre de Pathologie EST, Groupement Hospitalier EST, Université de Lyon, 69500 Bron, France.,

Anne Jouvet - Department of Neurological Surgery, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, 4401 Penn Avenue, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15224, USA.,

Ian F. Pollack - Departments of Neurosurgery and Cell and Developmental Biology, University of Michigan Medical School, 109 Zina Pitcher Place, 5018 BSRB, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109, USA.,

Xing Fan - Department of Neurosurgery, University of Michigan Medical School, 1500 E. Medical Center Drive, Taubman Center, Room 3552, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109, USA.,

Karin M. Muraszko - Department of Surgery, Division of Neurosurgery, University of Alabama at Birmingham, 1900 University Boulevard, THT 1052, Birmingham, Alabama 35294-0006, USA.,

G. Yancey Gillespie - Pediatric Neurosurgery, Catholic University Medical School, 00186 Rome, Italy.,

Concezio Di Rocco & Luca Massimi - Department of Pediatric Oncology and Hematology, Erasmus Medical Center, Dr. Molewaterplein 50, 3000 Rotterdam, The Netherlands.,

Erna M. C. Michiels & Nanne K. Kloosterhof - Department of Neurology, Erasmus Medical Center, Dr. Molewaterplein 50, PO Box 2040, 3000 CA Rotterdam, The Netherlands.,

Nanne K. Kloosterhof & Pim J. French - Department of Pathology, Erasmus Medical Center, Dr. Molewaterplein 50, 3015 GE Rotterdam, The Netherlands.,

Johan M. Kros - Clinical Research Division, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, 1100 Fairview Avenue North, D4-100, Seattle, Washington 98109, USA.,

James M. Olson - Seattle Children’s Hospital, Seattle, 98104, Washington, USA

James M. Olson - Neurological Surgery, University of Washington School of Medicine, Harborview Medical Center, 325 Ninth Avenue, Seattle, Washington 98104, USA.,

Richard G. Ellenbogen - Department of Pediatric Oncology, School of Medicine, Masaryk University, Cernopolni 9, 613 00 Brno, Czech Republic.,

Karel Zitterbart - Department of Pediatric Oncology, University Hospital Brno, 625 00 Brno, Czech Republic.,

Karel Zitterbart - Department of Pathology, University Hospital Brno, Jihlavska 20, 625 00 Brno, Czech Republic.,

Leos Kren - Department of Neurology, Vanderbilt Medical Center, 465 21st Avenue South, MRB III 6160, Nashville, Tennessee 37232-8550, USA.,

Michael K. Cooper - Department of Pathology and Molecular Medicine, Division of Anatomical Pathology, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario L8S 4L8, Canada.,

Boleslaw Lach - Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, Hamilton General Hospital, 237 Barton Street East, Hamilton, Ontario L8L 2X2, Canada.,

Boleslaw Lach - Department of Pathology, Duke University, DUMC 3712, Durham, North Carolina 27710, USA.,

Roger E. McLendon & Darell D. Bigner - Division of Experimental Medicine, McGill University, 4060 Ste Catherine West, Montreal, Quebec H3Z 2Z3, Canada.,

Adam Fontebasso & Nada Jabado - Department of Pathology, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec H3A 2B4, Canada.,

Steffen Albrecht - Department of Pathology, Montreal Children’s Hospital, 2300 Tupper, Montreal, Quebec H3H 1P3, Canada.,

Steffen Albrecht - Department of Pediatrics, Division of Hemato-Oncology, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec H3H 1P3, Canada.,

Nada Jabado - Northern Institute for Cancer Research, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 4LP, United Kingdom.,

Janet C. Lindsey, Simon Bailey & Steven C. Clifford - Departments of Neurological Surgery and Pediatrics, University of California San Francisco, 505 Parnassus Avenue, Room M779, San Francisco, California 94143-0112, USA.,

Nalin Gupta - Departments of Neurology, Pediatrics, and Neurosurgery, University of California San Francisco, The Helen Diller Family Cancer Research Building 1450 3rd Street, Room HD-220, MC 0520, San Francisco, California 94158, USA.,

William A. Weiss - Department of Neurosurgery, University of Debrecen, Medical and Health Science Centre, Móricz Zs. Krt. 22., 4032 Debrecen, Hungary.,

László Bognár & Almos Klekner - Pediatrics, Virginia Commonwealthy University, School of Medicine, Box 980646, Pediatric Hematology-Oncology, 1101 East Marshall Street, Richmond, Virginia 23298-0646, USA.,

Timothy E. Van Meter - Department of Neurosurgery, Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine, 1-1 Seiryo-machi, Aoba-ku, Sendai 980-8574, Japan.,

Toshihiro Kumabe & Teiji Tominaga - Department of Neurosurgery, Division of Pediatric Neurosurgery, St Louis University School of Medicine, 1465 South Grand Boulevard, Suite 3707, St Louis, Missouri 63104, USA.,

Samer K. Elbabaa - Department of Neurosurgery, Division of Pediatric Neurosurgery, Washington University School of Medicine and St Louis Children’s Hospital, Campus Box 8057, 660 South Euclid Avenue, St Louis, Missouri 63110, USA.,

Jeffrey R. Leonard - Departments of Pediatrics, Anatomy and Neurobiology, Washington University School of Medicine and St Louis Children’s Hospital, Campus Box 8208, 660 South Euclid Avenue, St Louis, Missouri 63110, USA.,

Joshua B. Rubin - Department of Neurosurgery, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, 10833 Le Conte Avenue, Campus 690118, Los Angeles, California 90095, USA.,

Linda M. Liau - Departments of Neurosurgery and Hematology & Medical Oncology, Laboratory of Molecular Neuro-Oncology, School of Medicine and Winship Cancer Institute, Emory University, 1365C Clifton Road NE, Atlanta, Georgia 30322, USA.,

Erwin G. Van Meir - Division of Oncology, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, 45229, Ohio, USA

Maryam Fouladi - Department of Neurosurgery, Kumamoto University Graduate School of Medical Science, 1-1-1, Honjo, Kumamoto 860-8556, Japan.,

Hideo Nakamura - Paediatric Neurosurgery, Ospedale Santobono-Pausilipon, 80145 Naples, Italy.,

Giuseppe Cinalli - 2nd Department of Pediatrics, Semmelweis University, 1085 Budapest, Hungary.,

Miklós Garami & Peter Hauser - Pathology, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, 1 Children’s Way, lot 820, Little Rock, Arkansas 72202, USA.,

Ali G. Saad - Dipartimento di Biochimica e Biotecnologie Mediche, University of Naples, Via Pansini 5, 80145 Naples, Italy.,

Achille Iolascon & Massimo Zollo - CEINGE Biotecnologie Avanzate, Via Gaetano Salvatore 486, 80145 Naples, Italy.,

Achille Iolascon & Massimo Zollo - Department of Neurosurgery, Chonnam National University Research Institute of Medical Sciences, Chonnam National University Hwasun Hospital and Medical School, 322 Seoyang-ro, Hwasun-eup, Hwasun-gun, Chonnam 519-763, South Korea.,

Shin Jung - Department of Surgery and Anatomy, Faculty of Medicine of Ribeirão Preto, Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil, Avenida Bandeirantes, 3900, Monte Alegre, 14049-900, Rebeirao Preto, São Paulo, Brazil.,

Carlos G. Carlotti - Pediatrics, University of Colorado Denver, 12800 19th Avenue, Aurora, Colorado 80045, USA.,

Rajeev Vibhakar - Department of Neurosurgery, University of Ulsan, Asan Medical Center, Seoul, 138-736, South Korea.,

Young Shin Ra - Division of Pediatric Neurosurgery, Case Western Reserve, Cleveland, 44106, Ohio, USA

Shenandoah Robinson - Rainbow Babies & Children’s, Cleveland, 44106, Ohio, USA

Shenandoah Robinson - Division of Neurosurgery, Hospital de Santa Maria, Centro Hospitalar Lisboa Norte EPE, 1169-050, Lisbon, Portugal.,

Claudia C. Faria - Cell Biology Program, The Hospital for Sick Children, 101 College Street, TMDT-401-J, Toronto, Ontario M5G 1L7, Canada.,

Claudia C. Faria - Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of Calgary, 3330 Hospital Drive NW, HRIC 2A25A, Calgary, Alberta T2N 4N1, Canada.,

Jennifer A. Chan - UCSD Division of Neurosurgery, Rady Children’s Hospital San Diego, 8010 Frost Street, Suite 502, San Diego, California 92123, USA.,

Michael L. Levy - Department of Molecular Oncology, British Columbia Cancer Research Centre, 675 West 10th Avenue, Vancouver, British Columbia V5Z 1L3, Canada.,

Poul H. B. Sorensen - Department of Neurology, Harvard Medical School, Children’s Hospital Boston, Fegan 11, 300 Longwood Avenue, Boston, Massachusetts 02115, USA.,

Scott L. Pomeroy - Department of Neurology and Neurological Sciences, Stanford University School of Medicine, 1201 Welch Road, MSLS Building, Rm P213, Stanford, California 94305, USA.,

Yoon-Jae Cho - Banting and Best Department of Medical Research, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario M5G 1L6, Canada.,

Gary D. Bader - Samuel Lunenfeld Research Institute at Mount Sinai Hospital, University of Toronto, Toronto M5G 1X5, Ontario, Canada.,

Gary D. Bader - Department of Haematology & Oncology, The Hospital for Sick Children, 555 University Avenue, Toronto, Ontario M5G 1X8, Canada.,

Uri Tabori, Eric Bouffet & David Malkin - Department of Pathology, The Hospital for Sick Children, 555 University Avenue, Toronto, Ontario M5G 1X8, Canada.,

Cynthia E. Hawkins - Department of Pediatrics, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario M5G 1X8, Canada.,

David Malkin - Department of Medical Genetics, University of British Columbia, 675 West 10th Avenue, Vancouver, British Columbia V5Z 1L3, Canada.,

Marco A. Marra

Authors

- Paul A. Northcott

- David J. H. Shih

- John Peacock

- Livia Garzia

- A. Sorana Morrissy

- Thomas Zichner

- Adrian M. Stütz

- Andrey Korshunov

- Jüri Reimand

- Steven E. Schumacher

- Rameen Beroukhim

- David W. Ellison

- Christian R. Marshall

- Anath C. Lionel

- Stephen Mack

- Adrian Dubuc

- Yuan Yao

- Vijay Ramaswamy

- Betty Luu

- Adi Rolider

- Florence M. G. Cavalli

- Xin Wang

- Marc Remke

- Xiaochong Wu

- Readman Y. B. Chiu

- Andy Chu

- Eric Chuah

- Richard D. Corbett

- Gemma R. Hoad

- Shaun D. Jackman

- Yisu Li

- Allan Lo

- Karen L. Mungall

- Ka Ming Nip

- Jenny Q. Qian

- Anthony G. J. Raymond

- Nina Thiessen

- Richard J. Varhol

- Inanc Birol

- Richard A. Moore

- Andrew J. Mungall

- Robert Holt

- Daisuke Kawauchi

- Martine F. Roussel

- Marcel Kool

- David T. W. Jones

- Hendrick Witt

- Africa Fernandez-L

- Anna M. Kenney

- Robert J. Wechsler-Reya

- Peter Dirks

- Tzvi Aviv

- Wieslawa A. Grajkowska

- Marta Perek-Polnik

- Christine C. Haberler

- Olivier Delattre

- Stéphanie S. Reynaud

- François F. Doz

- Sarah S. Pernet-Fattet

- Byung-Kyu Cho

- Seung-Ki Kim

- Kyu-Chang Wang

- Wolfram Scheurlen

- Charles G. Eberhart

- Michelle Fèvre-Montange

- Anne Jouvet

- Ian F. Pollack

- Xing Fan

- Karin M. Muraszko

- G. Yancey Gillespie

- Concezio Di Rocco

- Luca Massimi

- Erna M. C. Michiels

- Nanne K. Kloosterhof

- Pim J. French

- Johan M. Kros

- James M. Olson

- Richard G. Ellenbogen

- Karel Zitterbart

- Leos Kren

- Reid C. Thompson

- Michael K. Cooper

- Boleslaw Lach

- Roger E. McLendon

- Darell D. Bigner

- Adam Fontebasso

- Steffen Albrecht

- Nada Jabado

- Janet C. Lindsey

- Simon Bailey

- Nalin Gupta

- William A. Weiss

- László Bognár

- Almos Klekner

- Timothy E. Van Meter

- Toshihiro Kumabe

- Teiji Tominaga

- Samer K. Elbabaa

- Jeffrey R. Leonard

- Joshua B. Rubin

- Linda M. Liau

- Erwin G. Van Meir

- Maryam Fouladi

- Hideo Nakamura

- Giuseppe Cinalli

- Miklós Garami

- Peter Hauser

- Ali G. Saad

- Achille Iolascon

- Shin Jung

- Carlos G. Carlotti

- Rajeev Vibhakar

- Young Shin Ra

- Shenandoah Robinson

- Massimo Zollo

- Claudia C. Faria

- Jennifer A. Chan

- Michael L. Levy

- Poul H. B. Sorensen

- Matthew Meyerson

- Scott L. Pomeroy

- Yoon-Jae Cho

- Gary D. Bader

- Uri Tabori

- Cynthia E. Hawkins

- Eric Bouffet

- Stephen W. Scherer

- James T. Rutka

- David Malkin

- Steven C. Clifford

- Steven J. M. Jones

- Jan O. Korbel

- Stefan M. Pfister

- Marco A. Marra

- Michael D. Taylor

Contributions

P.A.N. and M.D.T. co-conceived the study. P.A.N., M.A.M., and M.D.T. led the study. P.A.N. planned and executed experiments and analyses, supervised data acquisition, performed bioinformatic analyses, and extracted nucleic acids for the MAGIC cohort. D.J.H.S. led the bioinformatics and performed analyses. J.P. performed quantitative RT–PCR and Sanger sequencing of PVT1 fusions, expression profiled _PVT1_-encoded miRNAs, and generated schematics for PVT1 fusion genes. L.G. performed the MYC and miR-1204 knockdown experiments. A.S.M. supervised the RNA-Seq and WGS experiments and performed data analysis. T.Z., A.M.S. and J.O.K. performed the large insert paired-end sequencing and PCR verification of SNCAIP duplication samples. A.Ko. performed interphase FISH and immunohistochemistry for candidate genes. J.R. and G.D.B. led the pathway analyses and generated enrichment plots. S.E.S. and R.B. provided technical support with the GISTIC2 bioinformatic platform. D.W.E. performed interphase FISH for candidate genes. C.R.M., A.C.L. and S.W.S. performed the SNP6 genotyping analysis, provided a database of normal copy number variants, and the control dataset used to infer copy number in the tumour samples. S.M., A.D., F.M.G.C., M.K., D.T.W.J. and H.W. performed bioinformatic analyses and provided technical advice. Y.Y. sequenced CTNNB1 in the WNT tumours. V.R., D.K., M.F.R., T.A., and P.D. performed functional assays for candidate genes. B.Lu. extracted nucleic acids, managed biobanking, and maintained the patient database. S.M. and A.R. performed the drug database analysis. Xin W., Xiaochong W. and M.R. provided technical support. R.Y.B.C., A.C., E.C., R.D.C., G.R.H., S.D.J., Y.L., A.L., K.L.M., K.M.N., J.Q.Q., A.G.J.R., N.T., R.J.V., I.B., R.A.M., A.J.M., R.H. and S.J.M.J. led the RNA-Seq and WGS experiments and performed data analyses. A.F.-L and A.M.K. provided the database of SHH-responsive genes. R.J.W.-R., W.A.G., M.P.-P., C.C.H., O.D., S.S.R., F.F.D., S.S.P.-F., B.-K.C., S.-K.K., K.-C.W., W.S., C.G.E., M.F.-M., A.J., I.F.P., X.F., K.M.M., G.Y.G., C.D.R., L.M., E.M.C.M., N.K.K., P.J.F., J.M.K., J.M.O., R.G.E., K.Z., L.K., R.C.T., MKC, B.La., R.E.M., D.D.B., A.F., S.A., N.J., J.C.L., S.B., N.G., W.A.W., L.B., A.Kl., T.E.V.M., T.K., T.T., S.K.E., J.R.L., J.B.R., L.M.L., E.G.V.M., M.F., H.N., G.C., M.G., P.H., A.G.S., A.I., S.J., C.G.C., R.V., Y.S.R., S.R., M.Z., C.C.F., J.A.C., M.L.L., Y.-J.C., U.T., C.E.H., E.B., S.C.C. and S.M.P. provided the patient samples and clinical details that made the study possible. P.H.B.S., M.M., S.L.P., Y.-J.C., U.T., C.E.H., E.B., S.W.S., J.T.R., D.M., S.C.C., S.J.M.J., J.O.K., S.M.P. and M.A.M. provided valuable input regarding study design, data analysis, and interpretation of results. P.A.N., D.J.H.S., J.P., L.G., A.S.M., M.A.M. and M.D.T. wrote the manuscript. M.A.M. and M.D.T. provided financial and technical infrastructure and oversaw the study. M.A.M. and M.D.T. are joint senior authors and project co-leaders.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence toMarco A. Marra or Michael D. Taylor.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

This file contains Supplementary Figures 1-41; Supplementary Tables 1-2, 6, 8-15 and 17-21 (see Supplementary Data file for Supplementary Tables 3-5, 7 and 16); Supplementary Methods and additional references. (PDF 21021 kb)

Supplementary Data

This zipped file contains Supplementary Tables 3-5, 7 and 16. (ZIP 681 kb)

PowerPoint slides

Rights and permissions

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-Share Alike licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/).

About this article

Cite this article

Northcott, P., Shih, D., Peacock, J. et al. Subgroup-specific structural variation across 1,000 medulloblastoma genomes.Nature 488, 49–56 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11327

- Received: 29 February 2012

- Accepted: 14 June 2012

- Published: 25 July 2012

- Issue Date: 02 August 2012

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11327