Complete sequence and comparative genome analysis of the dairy bacterium Streptococcus thermophilus (original) (raw)

Main

The genus Streptococcus comprises several harmful pathogenic species such as Streptococcus pyogenes or Streptococcus pneumoniae, together with a single 'Generally Recognized As Safe' species, S. thermophilus. Assessing the innocuous nature of S. thermophilus as a food microorganism is of major importance since this bacterium is widely used for the manufacture of dairy products1,2,3 (annual market value of ∼$40 billion)3. In consequence, over 1021 live cells are ingested annually by the human population. The dairy streptococcus must have followed a divergent evolutionary path from that of its pathogenic congeners, as it has adapted to a rather narrow, well-defined and constant ecological niche, milk. To obtain insight into this path and to assess the potential for virulence of this bacterium, we sequenced the genomes of two yogurt strains of S. thermophilus, and compared them to those of previously sequenced pathogenic streptococci4,5,6,7,8,9.

Results

Divergence of S. thermophilus strains

S. thermophilus CNRZ1066 and LMG13811 were isolated from yogurt manufactured in France and in the United Kingdom, respectively. Both strains contain a single circular chromosome of 1.8 Mb, containing about 1,900 coding sequences (Supplementary Fig. 1 online and Table 1). Out of these, about 1,500 (80%) are orthologous (defined as BLASTP reciprocal best hits) to other streptococcal genes, which indicates that S. thermophilus and its pathogenic relatives still share a substantial part of their overall physiology and metabolism. The two S. thermophilus genomes reported here display about 3,000 single nucleotide differences (0.15% polymorphism). Taking into account the estimated natural mutation rate10, and assuming a growth rate between one and ten divisions per day, their common ancestor would have lived about 107 generations ago, that is, 3,000–30,000 years back, roughly fitting the duration of human dairy activity, believed to have begun about 7,000 years ago1. The two genomes differ by 170 single nucleotide shifts, mostly in mononucleotide (n > 3) stretches, and 42 regions of sequence differences >50 base pairs (indels) that represent about 4% of genome length (Supplementary Table 1 online). The two strains have >90% of coding sequences in common (Table 1), suggesting a similar lifestyle, as expected from their involvement in the same dairy process. The main differences concern genes for extracellular polysaccharide biosynthesis (eps, rps), bacteriocin synthesis and immunity, a remnant prophage and a locus known as 'clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats' (denoted CRISPR2 here; CRISPR1 is present in both strains), closely linked to genes of unknown function (cas, Supplementary Fig. 2 online)11.

Table 1 General features of S. thermophilus CNRZ1066 and LMG18311 genomes

Inactive S. thermophilus genes

Unexpectedly, 10% of the S. thermophilus genes are not functional due to frameshift, nonsense mutation, deletion or truncation (globally named pseudogenes). This proportion is the highest among the sequenced streptococcal genomes (Supplementary Table 2 online). A nearly identical set of pseudogenes is shared between the two strains. Different functional categories are affected to various extents, ranging from ∼60% truncated coding sequences for “Other Functions” (atypical conditions, phages, transposons), which mainly include insertion sequences known to be prone to inactivation5 (Supplementary Table 2 online), to only 3.5% or even none, for 'Translation' and 'Transcription', respectively (Table 2). Remarkably, two of the most highly decaying functional groups, 'Transport Proteins' and 'Energy Metabolism' (∼30% truncated coding sequences) relate to carbohydrate degradation, uptake and fermentation. Notably, half of the genes dedicated to sugar uptake, including four of the seven sugar phosphotransferase system (PTS) transporters, are pseudogenes in S. thermophilus (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4 online). To substantiate this finding, we sequenced ptsG (glucose), fruA (fructose), bglP (β-glucoside) and treP (trehalose) PTS transporter genes in eight different S. thermophilus strains and in four strains of the closely related oral commensal Streptococcus salivarius (trehalose PTS was not analyzed in the latter). We found them to be pseudogenes in all S. thermophilus strains (with a single exception of the fructose PTS in one strain), whereas they appeared intact in the four S. salivarius strains. Inactivation of two other genes involved in carbon metabolism, butA (acetoin reductase) and adhE (alcohol-acetaldehyde dehydrogenase), in the S. thermophilus but not S. salivarius strains also took place. Some genes dedicated to carbohydrate uptake may have also been lost, as S. thermophilus has only a minor fraction (19–36%) of the genes present in other streptococci (Supplementary Table 3 online). Conversely, a specific symporter for lactose (the main milk carbohydrate) is present in the S. thermophilus genome but absent in other streptococci (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4 online). Thus, probably because mammals have emerged relatively recently (60 million years ago) in comparison to the remote lactic acid bacteria group (1.5–2 billion years ago)12, numerous genes encoding proteins dispensable in the milk niche have become pseudogenes, paving the way towards gene loss.

Table 2 Truncated coding sequences in different functional categories

Absence of virulence-related genes in S. thermophilus

The availability of the S. thermophilus genome sequence allowed us to systematically search the chromosome for potential genetic virulence determinants. The ability to use an extended range of carbohydrates is reported to be important for the virulence of pathogenic streptococci, possibly by allowing maintenance of these bacteria in their ecological niche5,9. The observed impairment of this function in S. thermophilus is likely to reduce the virulence potential. Antibiotic resistance is another important facet of pathogen virulence. The S. thermophilus genome does not contain any obvious antibiotic modification genes such as those found in the Streptococcus agalactiae pathogen8 and it is reported to be sensitive to a wide range of antimicrobial compounds2. Many streptococcal virulence-related genes (VRGs) are absent from the S. thermophilus genome or are present only as pseudogenes, unless they code for proteins performing basic cellular functions (Supplementary Tables 5,6,7 online). Have some of the absent genes been lost from S. thermophilus, rather than being acquired by the pathogenic streptococci? Over a quarter of virulence-related genes absent in S. thermophilus are present in both S. pyogenes and S. pneumoniae (25/92, using BLASTP with a cut-off value of 10−10) and almost 40% of these (9/25) are found in regions that are colinear in the two genomes. This suggests that they were present in the strain ancestral to both pathogenic species and presumably S. thermophilus and that they were lost from the latter.

Pathogenic streptococci exploit surface-exposed proteins to achieve adhesion to mucosal surfaces and escape host defenses4. Among the 28 S. pneumoniae virulence-related genes coding surface-exposed proteins, only 4 have orthologs in S. thermophilus (Supplementary Table 7 online). A global analysis of surface proteins revealed a major decay in specialized surface proteins (excluding lipoproteins) with a high proportion of pseudogenes (8/13, Supplementary Tables 8,9,10 online). The lipoprotein class, which includes a large number of substrate-binding subunits of ABC transporters (16 out of 27–28 predicted lipoproteins) and contains a low number of virulence-related genes (2 out of 27–28), is not massively affected. Globally, the most important virulence determinants that are exposed on the cell surface of pathogenic streptococci are absent or inactivated, such as the pneumococcal surface protein A and C (PspA, PspC), the pneumococcal manganese ABC transporter lipoprotein PsaA, IgA proteases, adhesins and a majority of pneumococcal choline-binding proteins. One homolog to a choline-binding protein (CbpD) was found in each S. thermophilus genome (Supplementary Table 9 online) but neither contains the domain necessary for binding to teichoic acids substituted with phosphorylcholine, in line with the lack of the lic gene cluster required for phosphorylcholine metabolism13 in the S. thermophilus genome. The two S. thermophilus genomes lack genes coding for sortase-anchored surface proteins14; moreover, the single sortase gene itself is a pseudogene. Some of the important virulence determinants in pathogenic streptococci (S. pyogenes, Streptococcus mutans)6,9 are sortase-anchored proteins. Furthermore, sortase mutants of pathogenic Gram-positive bacteria, including streptococci (S. mutans, Streptococcus gordonii) are attenuated in animal models15. In spite of the presence of homologs of the cps genes, which are involved in the synthesis of the capsule that is essential for virulence in pathogenic streptococci such as S. pneumoniae, the two S. thermophilus strains are not encapsulated. Their cps homologs, also known as eps, are involved in the synthesis of exopolysaccharides, important for the industrial use of S. thermophilus, as they confer the desired texture to yogurt16.

RecQ inhibits symmetrical genome inversions in bacteria

Genome plasticity is another important feature for evolutionary adaptation of pathogens to host defense mechanisms17, as opposed to genome stability, which is expected to better fit the sedate life style of a dairy bacterium. To estimate genome instability we analyzed symmetrical inversions around the chromosome origin/termination axis, which result from recombination events between the replication forks18. X-alignment analysis of pathogenic streptococci versus S. thermophilus revealed a much higher score of chromosomal inversions within the Streptococcus genus than in pairwise comparisons of closely related Bacillus species (see Supplementary Fig. 3a and b online for two selected comparisons with similar G+C content). What might be the reason for this high inversion frequency? We examined replication and recombination-related genes likely to play a role in recombination between the replication forks, and found that streptococci lack the recQ gene whereas B. subtilis has it. RecQ helicases are present in most living cells, from bacteria to man, and contribute in several ways to genome stability19. We found a negative correlation between the frequency of symmetrical chromosomal inversions and the presence of the recQ helicase gene in Gram-positive bacteria (Supplementary Fig. 3c online), suggesting that RecQ stabilizes the genome of these bacteria. However, as all streptococci lack RecQ, this protein does not increase the stability of the S. thermophilus genome relative to its pathogenic relatives and its X-alignment with other streptococci does not appear more conserved than that between pathogenic streptococci (not shown). It is interesting that a phylogenetically related bacterium used in dairy fermentations, Lactococcus lactis (previously S. lactis) possesses recQ20. We noted that pathogenic streptococci, but not S. thermophilus and L. lactis, lack yet another potential genome-stabilizing function, encoded by the sbcC and sbcD genes and thought to participate in the repair of recombinogenic double-stranded DNA breaks21. These genes are adjacent to a remnant transposase in S. thermophilus, suggesting they may have been introduced by lateral gene transfer at a later evolutionary stage to counteract the destabilizing consequences of RecQ deprivation. However, as is often the case with the putative LGT, we cannot rule out the possibility that the genes were originally present in all streptococci and were lost subsequently by deletion from the pathogenic species.

Lateral gene transfer in S. thermophilus

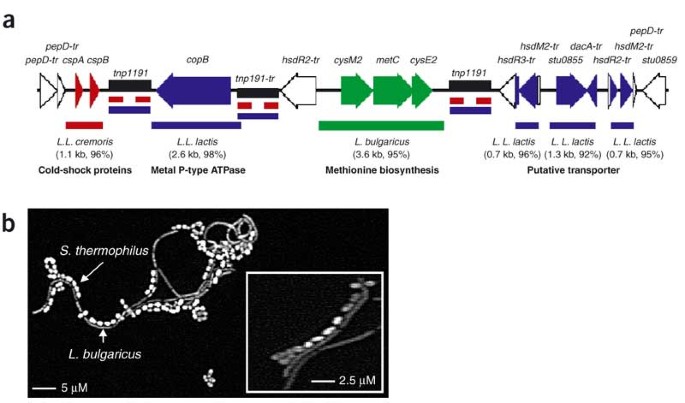

In addition to gene decay and loss, lateral gene transfer has contributed to the shaping of the S. thermophilus genome. There are >50 insertion sequences in the two genomes, some with anomalous G+C content and associated with genes of relevance to milk adaptation. About 75% of insertion sequences are associated with the change in S. thermophilus gene order relative to S. pyogenes, suggesting that these sequences play an important role in the shaping of the genome. A particularly interesting case of LTG is a 17-kb region found within a truncated pepD gene, that is present in both S. thermophilus strains. It could be considered as a hot spot of lateral gene transfer, as it contains three of the six insertion sequence 1191 copies present in the LMG18311 strain and constitutes a mosaic of fragments with more than 90% identity to DNA of Lactobacillus bulgaricus and two subspecies of L. lactis (lactis and cremoris), three other bacteria also growing in milk (Fig. 1a). Interestingly, the leftward flanking region is conserved in two streptococcal species (Streptococcus equii and S. mutans). Similarly, the rightward flanking region is conserved in S. equii, starting about 3.5 kb from the end of the 17 kb region. This conservation supports the hypothesis that insertions took place in the S. thermophilus genome. The L. bulgaricus fragment (3.6 kb) brings a unique copy of metC allowing methionine biosynthesis, a rare amino acid in milk2. The high level of identity (95%) of the respective metC regions reveals a recent lateral gene transfer event between these two rather distant species used in association in yogurt manufacture2 and suggests that ecological proximity rather than a phylogenetic one is a prerequisite for lateral gene transfer. We observed that the two species adhere to each other (Fig. 1b), which could facilitate gene transfer between them.

Figure 1: Lateral gene transfer between S. thermophilus and dairy bacteria.

(a) Schematic representation of a 17-kb mosaic region of lateral gene transfer encompassing DNA fragments with more than 90% DNA/DNA identity with Lactococcus lactis subsp. lactis20 (L.L. lactis, blue), Lactococcus lactis subsp. cremoris (L.L. cremoris, red; Joint Genome Institute, http://www.jgi.doe.gov) and Lactobacillus bulgaricus (green; Joint Genome Institute, http://www.jgi.doe.gov). Rectangular boxes in color correspond to exchanged DNA regions; species, DNA fragment size and percentage of DNA identity are indicated below. IS_1191_ are shown as black boxes. Extension '-tr' indicates genes inactive because of a truncation or one or more frameshifts, _pep_D, endopeptidase; tnp, transposase; _hsd_R, restriction endonuclease; _hsd_M, methylase; _dac_A, carboxypeptidase; IS, insertion sequences. (b) Adhesion of S. thermophilus CNRZ1066 and L. bulgaricus. The two organisms were cultivated together in liquid broth to mid-exponential phase; a glass slide was deposited in the culture for 1 h, withdrawn and rinsed five times with water and observed under an optical microscope. Inset, higher magnification.

Discussion

Comparative genomics leads us to the view that the dairy streptococcus genome may have been shaped mainly through loss-of-function events, even if lateral gene transfer played an important role. This is the first instance where regressive evolution is observed in a food niche rather than in pathogen- or symbiont-host situations22,23. The massive gene decay resulted in inactivation and loss of most of the virulence determinants. This provides a strong genomic argument in support of the 'Generally Recognized As Safe' status of the dairy streptococcus, indicating that massive consumption of this bacterium by humans likely entails no health risk.

Methods

Strains.

S. thermophilus strains CNRZ1066 and LMG18311 are yogurt isolates, deposited in Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique (INRA) and Laboratorium voor Microbiologie Gent (LMG) collections. Other Streptococcus strains used in this study are from the INRA collection: S. salivarius JIM 14, 15, 16 and 17; S. thermophilus CNRZ 302, 385, 388, 389, 703, 1100,1202 and 1575.

Genome sequencing and assembly.

The complete sequences were determined by the random shotgun sequencing strategy followed by multiplex PCR as described earlier20. Two sets of random libraries containing 2- to 3-kb inserts were constructed from chromosomal DNA from S. thermophilus strains LMG18311 and CNRZ1106. Assembling of 20,000 and 28,000 sequences gave 350 and 300 contigs, respectively, for the two strains. We carried out 1,500 multiplex PCR reactions for final assembling of CNRZ1066 in mixtures of 48 primers, according to the one-step protocol20, which led to a single circular contig. Subsequently, fragments representing the boundaries of repetitive regions were flagged with respect to partial mismatches at the ends of alignments and were independently assembled before the final sequence polishing. We used a similar finishing strategy for strain LMG18311. In summary, sequences of the two strains were determined by construction of two independent sequence data sets containing 28,000 random and 2,000 primer-directed reads for CNRZ1066 strain and 21,000 random and 1,500 primer-directed reads for LMG18311 strain.

Gene prediction and annotation.

A combination of CRITICA24, Glimmer25 and an open reading frame calling program developed at Integrated Genomics was used to identify coding sequences. The assembled genomes were analyzed using the ERGO (http://ergo.integratedgenomics.com/IGwit/) bioinformatics suite. The complete DNA sequence and the predicted coding sequences were added into the integrated environment for genome annotation and metabolic reconstruction as described26. Protein identifiers (PIDs) sth0001 and stu0001 were assigned to dnaA in CNRZ1066 and LMG18311, respectively.

Strain polymorphism.

Nucleotide sequences of internal fragments of the genes from different Streptococcus strains were determined from PCR products amplified from chromosomal DNAs using selected primers. For each gene fragment the nucleotide sequences were compared and clustered using CLUSTALW program.

Genome comparisons.

MUMmer27 was used for detailed comparative analysis of the two S. thermophilus genomes. Comparative genome alignments were based on results of BLASTP Reciprocal Best Hits (RBH)28, identification of conserved gene order and construction of chromosome gene clusters29. The number of ori-symmetrical genome rearrangements17 was computed using the syntheny groups30 identified in the RBH genome comparison. We computed the number of inversions by first determining the synthenic regions composed of RBH and then counting the number of regions equidistant from the origin (within 10% tolerance, allowing us to eliminate effects of most insertions and deletions in the compared genomes) but carried on different chromosome arms. Only genomes pairs that have a homology greater than 50% were selected. The homology was defined as the mean of BLASTP identity of all RBH in the pair of genomes that were compared.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The S. thermophilus genome sequences have been deposited in GenBank with accession no. CP000024 (CNRZ1061) and CP000023 (LMG18311).

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Nature Biotechnology website.

Accession codes

Accessions

GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ

References

- Fox, P.F. Cheese: Chemistry, Physics and Microbiology (Chapman & Hall, London, 1993).

Book Google Scholar - Tamine, A.Y. & Deeth, H.C. Yogurt: technology and biochemistry. J. Food Protection 43, 939–977 (1980).

Article Google Scholar - Chausson, F. & Maurisson, E. L'économie Laitière en chiffres (Centre National Interprofessionnel de l'Economie Laitière, Paris, France, 2002).

Google Scholar - Mitchell, T.J. The pathogenesis of streptococcal infections: from tooth decay to meningitis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 1, 219–230 (2003).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Tettelin, H. et al. Complete genome sequence of a virulent isolate of Streptococcus pneumoniae . Science 293, 498–450 (2001).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Ferretti, J.J. et al. Complete genome sequence of an M1 strain of Streptococcus pyogenes . Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 4658–4663 (2001).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Tettelin, H. et al. Complete genome sequence and comparative genomic analysis of an emerging human pathogen, serotype V Streptococcus agalactiae . Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 12391–12396 (2002).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Glaser, P. et al. Genome sequence of Streptococcus agalactiae, a pathogen causing invasive neonatal disease. Mol. Microbiol. 45, 1499–1513 (2002).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Ajdic, D. et al. Genome sequence of Streptococcus mutans UA159, a cariogenic dental pathogen. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 14434–14439 (2002).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Ochman, H., Elwyn, S. & Moran, N.A. Calibrating bacterial evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 12638–12643 (1999).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Jansen, R., van Embden, J.D., Gaastra, W. & Schouls, L.M. Identification of genes that are associated with DNA repeats in prokaryotes. Mol. Microbiol. 43, 1565–1575 (2002).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Stackebrandt, E. & Teuber, M. Molecular taxonomy and phylogenic position of lactic acid bacteria. Biochimie 70, 317–324 (1988).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Zhang, J.-R., Idanpaan-Heikkila, I., Fischer, W. & Tuomanen, E.I. Pneumococcal licD2 gene is involved in phosphorylcholine metabolism. Mol. Microbiol. 31, 1477–1488 (1999).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Comfort, D. & Clubb, R.T. A comparative genome analysis identifies distinct sorting pathways in Gram-positive bacteria. Infect. Immun. 72, 2710–2722 (2004).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Paterson, G.K. & Mitchell, T.J. The biology of Gram-positive sortase enzymes. Trends in Microbiol. 12, 89–95 (2004).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Broadbent, J.R., McMahon, D.J., Welker, D.L., Oberg, C.J. & Moineau, S. Biochemistry, genetics, and applications of exopolysaccharide production in Streptococcus thermophilus: a review. J. Dairy Sci. 86, 407–423 (2003).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Dobrint, U. & Hacker, J. Whole genome plasticity in pathogenic genomes. Curr. Opinion Microbiol. 4, 550–557 (2001).

Article Google Scholar - Eisen, J.A., Heidelberg, J.F., White, O. & Salzberg, S.L. Evidence for symmetric chromosomal inversions around the replication origin in bacteria. Genome Biol. 1, 1101–1109 (2000).

Article Google Scholar - Hickson, I.D. RecQ helicases: caretakers of the genome. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 3, 169–178 (2003).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Bolotin, A. et al. The complete genome sequence of the lactic acid bacterium Lactococcus lactis ssp. lactis IL1403. Genome Res. 11, 731–753 (2001).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Bidnenko, V. et al. sbcB sbcC null mutations allow RecF-mediated repair of arrested replication forks in rep recBC mutants. Mol. Microbiol. 33, 846–857 (1999).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Wren, B.W. Microbial genome analysis: insights into virulence, host adaptation and evolution. Nat. Rev. Genetics, 1, 30–39 (2000).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Cole, S.T. et al. Massive gene decay in the leprosy bacillus. Nature 409, 1007–1011 (2001).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Badger, J.H. & Olsen, G.J. CRITICA: Coding Region Identification Tool Invoking Comparative Analysis. Mol. Biol. Evol. 16, 512–524 (1999).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Delcher, A.L., Harmon, D., Kasif, S., White, O. & Salzberg, S.L. Improved microbial gene identification with GLIMMER. Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 4636–4641 (1999).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Overbeek, R. et al. WIT: integrated system for high-throughput genome sequence analysis and metabolic reconstruction. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 123–125 (2000).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Delcher, A.L. et al. Alignment of whole genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 27, 2369–2376 (1999).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Hirsh, A.E. & Fraser, H.B. Protein dispensability and rate of evolution. Nature 411, 1046–1049 (2001).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Overbeek, R., Fonstein, M., D'Souza, M., Pusch, G.D. & Maltsev, N. The use of gene clusters to infer functional coupling. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 2896–2901 (1999).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Huyen, M. & Bork, P. Measuring genome evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 5849–5856 (1998).

Article Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

The S. thermophilus LMG18311 chromosome sequence was supported by funding from the Walloon Region (Bioval no. 981/3866 and First Europe no. EPH3310300R0082) and FNRS (grant no. 2.4586.02). P.H. is Research Associate at FNRS.

Author information

Author notes

- Alla Lapidus, Eugene Goltsman & Nikos Kyprides

Present address: Microbial Genomics, Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute, 2800 Mitchell Drive, B400, Walnut Creek, California, 94598, USA - Gordon D Pusch & Ross Overbeek

Present address: Fellowship for Interpretation of Genomes, 15W155 81st Street, Burr Ridge, Illinois, 60527, USA - Michael Fonstein

Present address: Cleveland BioLabs, Inc., 10265 Carnegie Ave., Cleveland, Ohio, 44106 - Katrina Ngui

Present address: Department Anatomy and Cell Biology, University of Melbourne, Victoria, 3010, Australia - Sophie Burteau

Present address: Unité de Recherche en Biologie Cellulaire, Facultés Universitaires Notre-Dame de la Paix, 61 Rue de Bruxelles, 5000, Namur, Belgium - Michael Mazur and David Masuy: Deceased.

Authors and Affiliations

- Génétique Microbienne. Centre de Recherche de Jouy en Josas, Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique, Jouy en Josas, 78352, Cedex, France

Alexander Bolotin, Benoît Quinquis, Pierre Renault, Alexei Sorokin & S Dusko Ehrlich - Unité de Recherche Latière et Génétique Appliquée, Centre de Recherche de Jouy en Josas, Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique, Jouy en Josas, 78352, Cedex, France

Saulius Kulakauskas - Integrated Genomics, Chicago, 60612, USA, Illinois

Alla Lapidus, Eugene Goltsman, Michael Mazur, Gordon D Pusch, Michael Fonstein, Ross Overbeek & Nikos Kyprides - Institut des Sciences de la Vie, Université Catholique de Louvain, Louvain-la-Neuve, 1348, Belgium

Bénédicte Purnelle, Deborah Prozzi, Katrina Ngui, David Masuy, Frédéric Hancy, Sophie Burteau, Marc Boutry, Jean Delcour, André Goffeau & Pascal Hols

Authors

- Alexander Bolotin

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Benoît Quinquis

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Pierre Renault

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Alexei Sorokin

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - S Dusko Ehrlich

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Saulius Kulakauskas

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Alla Lapidus

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Eugene Goltsman

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Michael Mazur

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Gordon D Pusch

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Michael Fonstein

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Ross Overbeek

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Nikos Kyprides

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Bénédicte Purnelle

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Deborah Prozzi

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Katrina Ngui

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - David Masuy

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Frédéric Hancy

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Sophie Burteau

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Marc Boutry

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Jean Delcour

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - André Goffeau

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Pascal Hols

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence toS Dusko Ehrlich.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Fig. 1

Schematic representation of the S. thermophilus genome. (PDF 152 kb)

Supplementary Fig. 2

LMG18311 and CNRZ1061 share a CRISPR1 locus (∼3 kb) adjacent to two cas genes (cas1 and cas2), interspaced by unique sequences of a similar size, but differing in the number of direct repeats (34 and 43 in LMG18311 and CNRZ1066, respectively). (PDF 348 kb)

Supplementary Fig. 3

RecQ affects symmetrical inversions. (PDF 348 kb)

Supplementary Table 1

Characterization of the insertion-deletion regions (indels) longer than 50 bp between CNRZ1066 and LMG18311 genomes (PDF 23 kb)

Supplementary Table 2

Comparison of the content in pseudogenes among streptococcal genomes (PDF 22 kb)

Supplementary Table 3

Comparison of gene content involved in carbohydrate uptake among streptococcal genomes (PDF 23 kb)

Supplementary Table 4

Identification of genes involved in carbohydrate uptake in S. thermophilus CNRZ1061 (PDF 28 kb)

Supplementary Table 5

Identification of putative virulence related genes (VRGs) in S. thermophilus CNRZ1066 genome by comparison with S. pyogenes SF370 (M1) and S. pneumoniae TIGR4 genomes (PDF 23 kb)

Supplementary Table 6

Identification of VRGs in S. thermophilus CNRZ1066 similar to virulence genes from S. pyogenes SF370 (M1)7 (PDF 31 kb)

Supplementary Table 7

Identification of VRGs in S. thermophilus CNRZ1066 similar to demonstrated VRGs from S. pneumoniae TIGR45 (PDF 37 kb)

Supplementary Table 8

Comparison of putative surface exposed proteins among streptococcal genomes (PDF 26 kb)

Supplementary Table 9

Identification of putative surface exposed proteins (excluding lipoproteins) in S. thermophilus CNRZ1061 and LMG18311 (PDF 28 kb)

Supplementary Table 10

Best BlastP homologous proteins from Streptococci of putative surface exposed proteins (excluding lipoproteins) in S. thermophilus CNRZ1061 and LMG18311 (PDF 26 kb)

Rights and permissions

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-Share Alike license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/), which permits distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. This license does not permit commercial exploitation, and derivative works must be licensed under the same or similar license.

About this article

Cite this article

Bolotin, A., Quinquis, B., Renault, P. et al. Complete sequence and comparative genome analysis of the dairy bacterium Streptococcus thermophilus.Nat Biotechnol 22, 1554–1558 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt1034

- Received: 08 July 2004

- Accepted: 21 September 2004

- Published: 14 November 2004

- Issue Date: December 2004

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt1034