Parallel evolution of the make–accumulate–consume strategy in Saccharomyces and Dekkera yeasts (original) (raw)

Introduction

A fundamental characteristic of the Saccharomyces yeasts is their ability to degrade sugars to two-carbon components, in particular ethanol, even in the presence of excess oxygen. This characteristic is called the Crabtree effect1 and represents the background for the 'make–accumulate–consume' strategy2. Every autumn, when fruits ripen, a fierce competition for the fruit sugars starts within microbial communities. Yeasts, especially Saccharomyces cerevisiae and its close relatives, usually become the predominant group in niches with freely available mono- and oligo-saccharides, and the 'make–accumulate–consume' strategy helps these yeasts to out-compete other microorganisms3. Fast sugar consumption, ethanol production, accumulation and tolerance, and the ability to propagate without oxygen are some of the 'winning' traits, and have apparently evolved and become specialized to perfection in the S. cerevisiae lineage. Apparently, after the split between the S. cerevisiae and Kluyveromyces lactis lineages approximately 100 mya, the former drastically redesigned its carbon metabolism and developed the ability to suppress the respiratory metabolism and thereby accumulate ethanol3,4. A whole genome duplication (WGD4) and promoter rewiring5 in the S. cerevisiae lineage, which occurred around 100 mya, were the main molecular events providing the background for evolution of this strategy3,6,7,8. A specific _cis_-regulatory element, AATTTT, is present at a conserved position in K. lactis, Ashbya gossypii, Candida albicans, Debaryomyces hansenii and K. waltii promoters belonging to genes involved in rapid growth and respiration, but in Saccharomyces yeasts the motif is missing in the respiration-associated genes5. Apparently, the large-scale loss of this regulatory element caused a change in the global expression network of Saccharomyces yeasts5, and provided one of the mechanisms to achieve accumulation of ethanol3,5.

However, several modern yeasts, apart from S. cerevisiae and its sister species, are also capable of at least limited ethanol production and even its accumulation9. In this report, we characterize the Dekkera/Brettanomyces (D/B) yeasts10, which in nature often occupy a similar niche to Saccharomyces/Kluyveromyces (S/K) yeasts11. We demonstrate that the wine yeast D. bruxellensis is also a good ethanol producer owing to the loss of _cis_-regulatory elements from the promoters of genes crucial for respiration. Apparently, S. cerevisiae and D. bruxellensis lineages independently used global promoter rewiring in the development of the 'make–accumulate–consume' strategy.

Results

D. bruxellensis accumulates ethanol and acetic acid

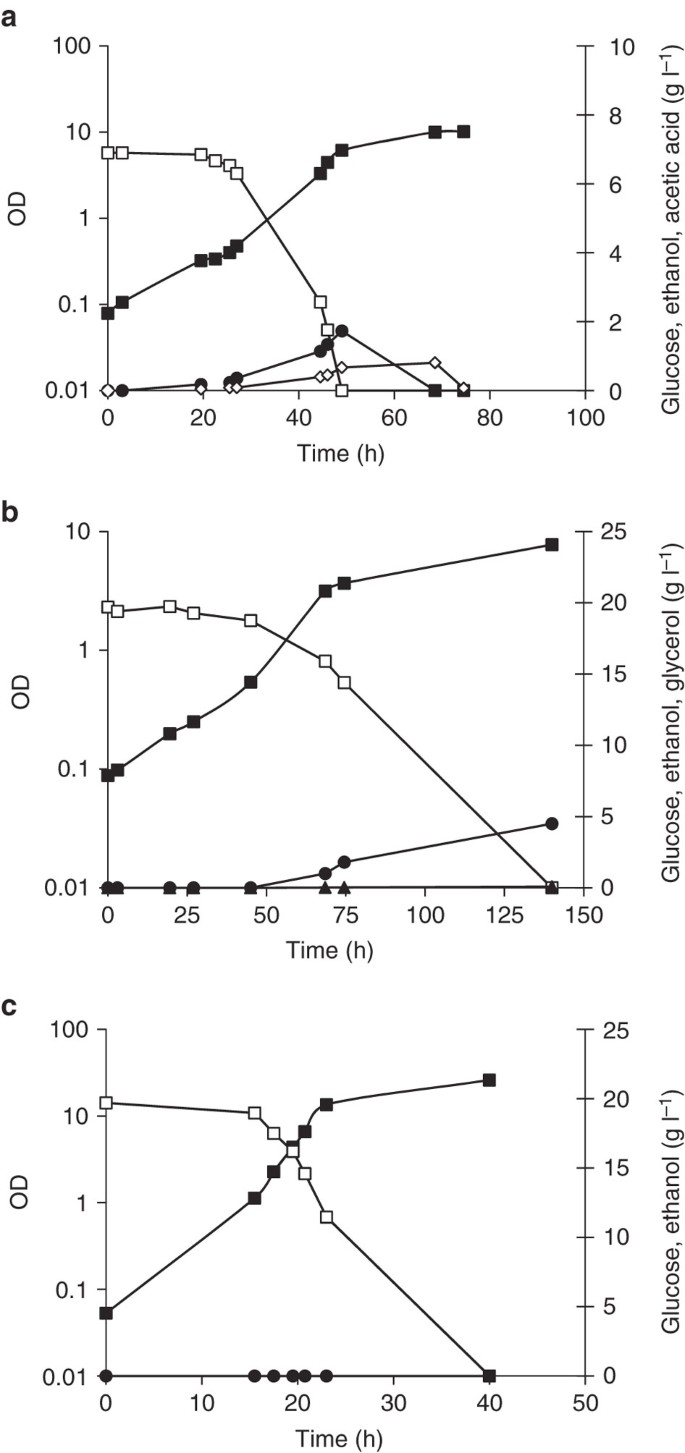

It has previously been reported that D. bruxellensis is a good ethanol producer (reviewed in ref. 12), but so far a detailed study of its carbon metabolism has not been available. Thus, several isolates of D. bruxellensis and Brettanomyces naardenensis were studied under controlled batch cultivation for their growth parameters and carbon metabolism (Fig. 1). In our experiments under aerobic conditions, D. bruxellensis produced substantial amounts of ethanol (Fig. 1a) and, as has been observed before13, good aeration stimulated acetate production (Fig. 1a). After glucose depletion, both ethanol and acetate were completely consumed. This yeast could also grow under anaerobiosis if the minimal medium was supplemented with Tween 80, ergosterol and amino acids (Fig. 1b). In contrast, in the presence of oxygen, B. naardenensis exhibited a completely respiratory metabolism and converted almost all glucose into biomass and carbon dioxide, and ethanol and acetate were not detected (Fig. 1c). This yeast produced higher biomass yield than D. bruxellensis and S. cerevisiae and is, in this sense, more similar to K. lactis9. B. naardenensis could not grow in the absence of oxygen. The D. bruxellensis ethanol yield in aerobiosis and the ability to grow without oxygen (Table 1, Fig. 1b) were very similar to those reported for S. cerevisiae14 and its close relatives. During anaerobic growth, D. bruxellensis converted glucose into biomass at lower yields than in aerobiosis due to a higher ethanol production (Table 1), and neither acetic acid nor pyruvate was produced and accumulated.

Figure 1: Growth of D/B yeasts under controlled conditions.

Optical density, OD600 nm (closed squares) and glucose (open squares), ethanol (closed circles), glycerol (closed triangles) and acetic acid (open diamonds) concentrations are shown. In each case a representative experiment is shown. (a) Batch culture of D. bruxellensis Y879 (CBS 2499) under aerobic conditions in the defined minimal medium. (b) Batch culture of D. bruxellensis Y879 under strict anaerobic conditions. (c) Batch culture of B. naardenensis Y922 (CBS 754) under aerobic conditions. B. naardenensis strains could not grow under strict anaerobic conditions.

Table 1 Growth parameters of D. bruxellensis and B. naardenensis.

Saccharomyces and Dekkera yeasts separated at least 200 mya

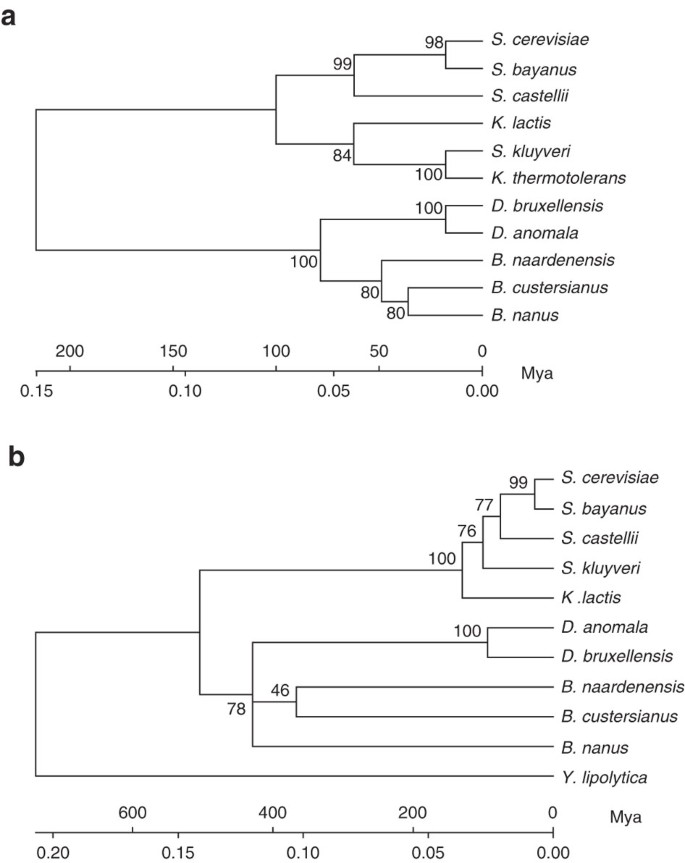

Phylogenetic relationship among the D/B and S/K yeast complexes was studied using the mitochondrial 15S rDNA and the nuclear 26S rDNA. Our analysis suggests that the S/K and D/B groups separated at least 200 mya (Fig. 2). We could also determine the timing of the separation of the two subgroups within the D/B complex. According to the mitochondrial 15S rDNA sequence analysis (Fig. 2a), the D. bruxellensis and B. naardenensis lineages separated close to 100 mya or, as the nuclear 26S rDNA locus analysis suggests (Fig. 2b), even before. The split between the D. bruxellensis and B. naardenensis lineages could have occurred at the same time as the division between the S. cerevisiae and K. lactis lineages. Interestingly, within the S/K and D/B groups the S. cerevisiae and D. bruxellensis lineages have independently acquired resistance to high ethanol concentration, which is a crucial trait to accompany efficient ethanol production and accumulation (Table 2). The D. bruxellensis lineage has in addition developed a high resistance to acidic pH and can still efficiently propagate at pH values as low as 2.3 (Table 2). This trait is one of the prerequisites for tolerance towards high acetate production, accumulation and later consumption (Fig. 1a).

Figure 2: Phylogenetic relationship among yeasts.

(a) The phylogenetic relationship is based on the mitochondrial 15S rDNA sequence (for details see ref. 15). Accumulation of substitutions was used to deduce the timing of the divergence events. The split between S. cerevisiae and S. kluyveri (post- and pre-WGD lineages in the S/K complex) was taken as 100 mya24 and this distance (or the number of accumulated substitutions) was then used to calibrate the rest of the events. Each of the D/B and S/K yeast complexes can be divided into two subgroups, based on their phylogenetic relationship and the physiological traits. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the phylogenetic tree. (b) The phylogenetic relationship based on the nuclear 26S rDNA sequences (for details see ref. 16). The accession numbers of the sequences, analysed using the neighbour-joining method22, can be found in the Supplementary Methods.

Table 2 Tolerance of acidic pH and ethanol.

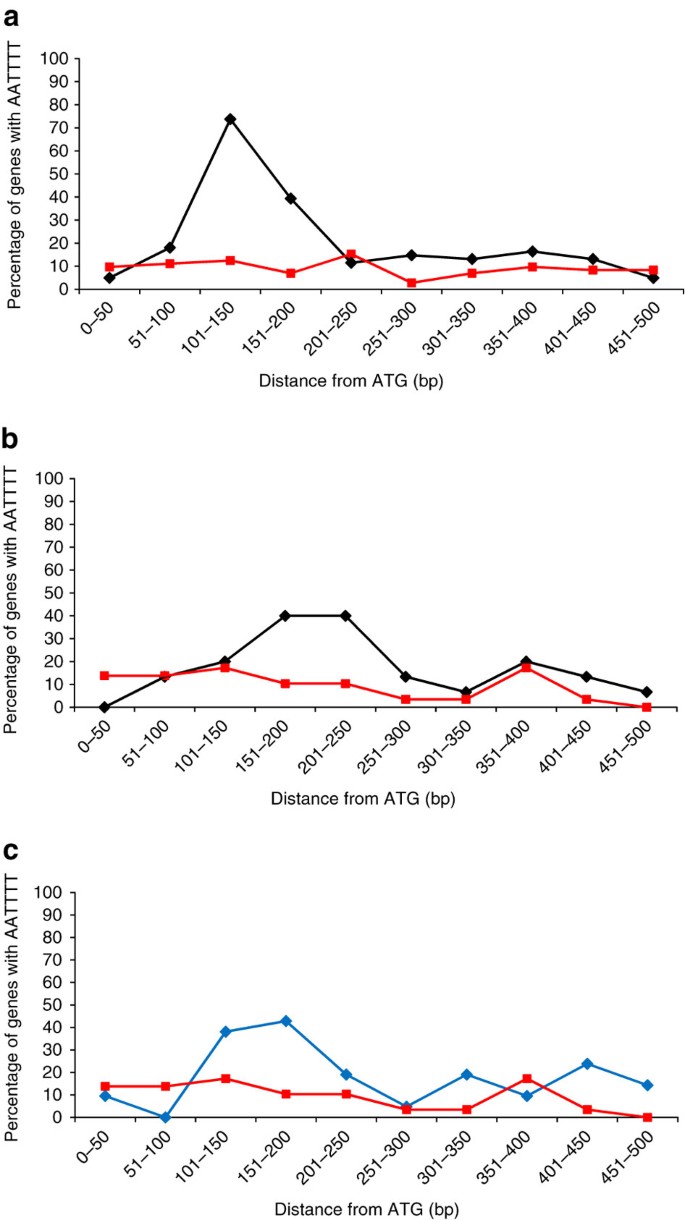

Promoter analysis demonstrates a _cis_-element loss

The D/B yeasts have not been intensively sequenced to date. Only the D. bruxellensis genome has recently been partially sequenced and the 40% of the genome available does not contain a substantial number of duplicated genes15,16. Therefore, it seems unlikely that an ancient genome duplication drove evolution towards the modern traits as was the case with the S. cerevisiae lineage. However, when we identified and analysed promoters belonging to rapid growth- and respiration-associated genes, a clear analogy between S. cerevisiae and D. bruxellensis was noted (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: The AATTTT motif is missing at the conserved position.

The S. cerevisiae (a) and D. bruxellensis (b, c) promoters of the respiration- and rapid growth-associated genes were analysed for the presence of the AATTTT _cis_-elements positioned at the conserved sites. For D. bruxellensis two different rapid growth-associated gene sets are shown: set 1 (containing 15 available promoters and including rRNA-processing-associated genes, black line, see b) and set 2 (including 21 available promoters and including CRP-associated genes, blue line, see c). For S. cerevisiae only set 1 is shown (and it includes only the available D. bruxellensis orthologues, black line), the set 2 data can be found elsewhere5. Sets 1 and 2 contain genes as defined by ref. 5. The 500 bp of sequence upstream was checked for the presence of the regulatory element; the percentage of the gene promoters containing the AATTTT motif (and its reverse complement) within the blocks of 50 bp was plotted against the distance from the start codon (see also ref. 5). The AATTTT motif was overrepresented in the promoters of the rapid growth-associated genes in the regions 101–150 bp upstream from the ATG codon in S. cerevisiae (a) and 101–250 bp upstream from the ATG codon in D. bruxellensis (b, c). The AATTTT motif did not exhibit any positional conservation in the respiration-associated genes (red line), and it was either missing or was spread equally along the promoter sequence. The differences in the distribution pattern of the motif in rRNA/CRP versus MRP genes in D. bruxellensis were statistically significant according to the repeated-measures analysis of variance.

The gene groups in this study follow the previously proposed gene sets based on the global gene expression studies in S. cerevisiae and C. albicans5. The rapid growth-associated genes set 1 (also called rRNA) included genes encoding enzymes involved in rRNA processing, pyrimidine biosynthesis pathway, RNA helicases, proteins involved in RNA biogenesis and transport, proteins with similarity to cytoplasmic ribosomal proteins, proteins involved in organization of actin cytoskeleton, t-RNA transporters and RNA polymerase I subunit (for more details see Supplementary Data 1). The rapid growth-associated genes set 2 (also called CRP) included genes coding for cytoplasmic ribosomal proteins (CRP), CTP synthase, translation initiation and elongation factors, RNA helicases, proteins involved in ribosomal biogenesis and nuclear export of ribosomal subunits, enzyme of the pyrimidine biosynthesis, tRNA synthetases, subunits of the RNA polymerases, heat shock proteins, genes involved in purine biosynthesis pathway, phosphoribosyl transferases, and genes coding for enzymes involved in elongation of fatty acids (for more details see Supplementary Data 1). The respiration-associated genes (also called MRP) included genes coding for mitochondrial ribosomal proteins (MRPs), proteins required for mitochondrial respiratory complex assembly, transport of ions to cytochrome oxidase, mitochondrial inorganic pyrophosphatase and ATP synthase assembly proteins. The D. bruxellensis set is based on 28 available promoters (for more details see Supplementary Data 1).

In S. cerevisiae and its close relatives we could find the AATTTT motif at the fixed position in the genes associated with rapid growth (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Fig. S1). However, in S. cerevisiae, the motif is missing at the fixed position in the respiration-associated genes, such as MRP (ref. 5; Fig. 3a, Supplementary Data 2). Similarly, in a post-WGD yeast S. bayanus, a great majority of respiration-associated genes lacks the motif at the fixed position (Supplementary Fig. S1), while a pre-WGD yeast K. lactis has the motif at the fixed position in the respiration-associated genes (Supplementary Fig. S1). Over 90% of available D. bruxellensis respiration-associated genes (MRP set) lacked the motif at the fixed position within the promoter (Fig. 3b,c). In the promoters of D. bruxellensis associated with rapid growth, such as genes coding for CRP and proteins involved in rRNA processing, the AATTTT motif was present at a fixed position, 150–250 bp from the start codon of set 1 genes (including rRNA-processing genes) (Fig. 3b), and 100–200 bp from the start codon of set 2 genes (including CRP) (for details see Fig. 3c and Supplementary Data 1 and 2). To test whether this pattern represents a parallel loss of the motif in D. bruxellensis and the Saccharomyces lineage, we examined the position of the motif in Yarrowia lipolytica, which separated from the S. cerevisiae lineage before the C. albicans and D. bruxellensis6 and could thus be used to deduce the properties of the common yeast progenitor. The _cis_-regulatory motif was also present at a specific position in the promoter of a majority of the analysed genes associated with rapid growth and respiration of Y. lipolytica (Supplementary Fig. S1), suggesting that the ancestral yeast also possessed the motif in the promoters of these genes.

Differential expression of rapid growth- and respiration-associated genes

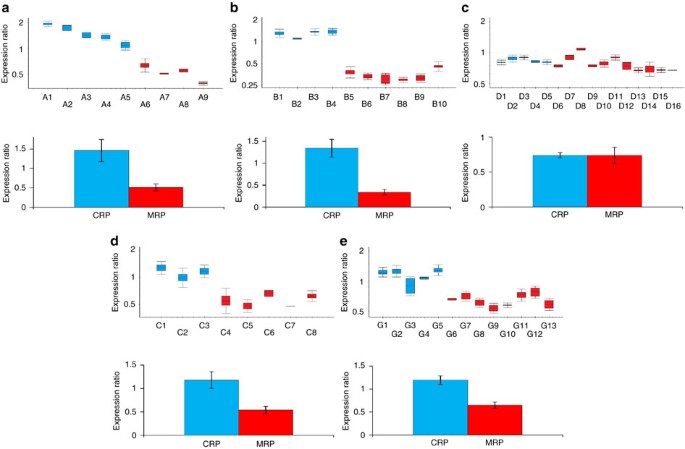

To determine whether the AATTTT motif is also associated in D. bruxellensis with the differential regulation of genes when cells ferment or respire, we examined the expression pattern of several rapid growth- and respiration-associated genes under these conditions. We grew yeasts in two different media containing either a fermentable carbon source (glucose) or a non-fermentable one (ethanol). The transcription levels of several rapid growth- or respiration-associated genes were then expressed as a ratio of normalized expression levels in the glucose versus ethanol experiments (Fig. 4). For example, in S. cerevisiae (Fig. 4a) and S. bayanus (Fig. 4b) the respiration-associated genes were expressed much lower in glucose than in ethanol. In K. lactis there was no difference in the expression levels (Fig. 4c). In D. bruxellensis Y872, the expression of the rapid growth-associated genes was 1.2-fold higher in the glucose than in the ethanol medium. The respiration-associated genes were expressed twofold lower in glucose than in ethanol (because the relative expression value was approximately 0.5, Fig. 4d). In another strain of D. bruxellensis, Y883, the respiration-associated genes were also expressed at a lower level in the presence of glucose (Fig. 4e). The observed pattern was very similar to the one in S. cerevisiae and S. bayanus (Fig. 4a,b and ref. 5), but different from the pattern in K. lactis (Fig. 4c and ref. 5) and C. albicans5. In the latter two species, transcription of the respiration-associated genes seems to be similar in fermentable and non-fermentable media. Note that these two species have the AATTTT motif in all promoters, whereas this motif is missing at a fixed position in the promoters of the respiration-associated genes of the post-WGD species and D. bruxellensis.

Figure 4: Respiration-associated genes are less expressed in the presence of glucose.

Ratio of the expression levels of the rapid growth-associated genes (CRP, blue) and respiration-associated genes (MRP, red) in different yeasts species: (a) S. cerevisiae, (b) S. bayanus, (c) K. lactis, (d) D. bruxellensis Y872 (CBS1943) and (e) D. bruxellensis Y883 (CBS3025). Each yeast species was grown in a defined minimal medium with a fermentable carbon source (glucose) and a defined minimal medium with a non-fermentable carbon source (ethanol). The results were expressed as a ratio of expression levels in the glucose and ethanol experiments. The α-tubulin encoding gene (YML085C), which has the same expression level in both media (according to the microarray studies; for example, ref. 5), was used to normalize the data. The upper graphs for each species show the ratio of expression levels of a set of CRP and a set of MRP genes from a single representative experiment (each gene measurement was done in duplicates). The take-off and the amplification values, obtained from the relative quantification performed using the RotorGene 2000 software, were used to quantify the expression ratios with help of REST 2009 V2.0.13 with RG mode5. These results are presented as Whisker box plot. The lower graphs show the average of the expression ratios calculated for all CRP and MRP genes in each strain and are based on four (b–d) or two (a, e) replicates. The error bars represent the standard deviation. Note that all the orthologous gene names follow the S. cerevisiae naming system and the genes are lined along the x axis. The following genes were used: a S. cerevisiae genes: A1-YLR029C; A2-YLR264W; A3-YBR031W; A4-YCR012W; A5-YKL156W; A6-YBR282W; A7-YMR225C; A8-YMR193W; A9-YMR188C. b S. bayanus genes: B1-YOR063W; B2-YPL131W; B3-YNL178W; B4-YBR031W; B5-YDR116C; B6-YGR165W; B7-YKL167C; B8-YOR158W; B9-YGR220C; B10-YBR122C. c K. lactis genes: D1-YBR189W; D2-YPL143W; D3-YHR141C; D4-YHR021C; D5-YLR367W; D6-YGL129C; D7-YEL050C; D8-YKL138C; D9-YHR147C; D10-YDR237W; D11-YMR158W; D12-YNR037C; D13-YNL185C; D14-YGR165W; D15-YDR175C; D16-YDR322W. d D. bruxellensis Y879 genes: C1-YDL081C; C2-YPL143W; C3-YPL131W; C4-YDR405W; C5-YHR075C; C6-YGR165W; C7-YGR220C; C8-YNL005C. e D. bruxellensis Y883 genes: G1-YPL143W; G2-YDL081C; G3-YPL131W; G4-YDR025W; G5-YGL103W; G6-YDR405W; G7-YGR165W; G8-YGR220C; G9-YNL005C; G10-YGR215W; G11-YEL050C; G12-YML009C; G13-YHR075C.

Discussion

D. bruxellensis produced substantial amounts of ethanol under aerobic conditions and could also grow anaerobically (Table 1, Fig. 1a,b), just like S. cerevisiae and its close relatives. In other words, D. bruxellensis can be classified as a Crabtree-positive and facultative anaerobic yeast. B. naardenensis, on the other hand, behaves more similarly to K. lactis (Table 1), which is a Crabtree-negative and aerobic yeast. Our phylogenetic analysis suggests that the S/K and D/B groups separated at least 200 mya (Fig. 2). In other words, the divergence took place long before the WGD, promoter rewiring, URA1 horizontal transfer and ADH duplication events that occurred in the S. cerevisiae lineage and are thought to be involved in the 'make-accumulate-consume' strategy (reviewed in ref. 3). The S. cerevisiae and D. bruxellensis lineages, but not the K. lactis and B. naardenensis lineages, have apparently independently acquired the ability to accumulate ethanol in the presence of oxygen and resistance to high ethanol concentration, which is a crucial trait to accompany efficient ethanol production and accumulation (Table 2). At least 100 mya, the progenitors of different modern yeast lineages likely experienced very similar environmental conditions, with sudden appearance of high amounts of available sugars, and pressures, such as fierce competition from other microbes3. Therefore, it is not surprising that several similar traits, like the ability to grow without oxygen and the Crabtree effect (or 'make–accumulate–consume' strategy), can be found among the not so closely related modern yeasts. Dekkera yeasts may 'poison' their competitors both with ethanol, as S. cerevisiae does, and by lowering the pH of the local environment. This particular biological wheel appears to have been invented more than once, spurring us to ask what were then the molecular scenarios and evolutionary pathways leading to these phenotypes.

When we analysed promoters belonging to the rapid growth- and respiration-associated genes of S. cerevisiae and D. bruxellensis, the AATTTT motif was present at the conserved position in the rapid growth-associated genes but missing in the respiration-associated genes (Fig. 3). Whereas all other examined pre-WGD yeasts keep the motif at a fixed position in both the rapid growth and respiration-associated gene sets, it appears that D. bruxellensis has, in parallel with the post-WGD lineage, undergone a large-scale motif loss. The expression pattern of several rapid growth- and respiration-associated genes in S. cerevisiae and D. bruxellensis showed differential regulation in media containing either a fermentable carbon source or a non-fermentable one (Fig. 4). In conclusion, apparently both lineages, post-WGD and D. bruxellensis, used the same molecular tool, global promoter rewiring, to change the regulation pattern of expression of respiration-associated genes, resulting in ethanol accumulation and consequently in the development of the 'make–accumulate–consume' strategy.

Yeasts and other organisms share many traits that have a common origin, and in these cases we infer that the genes behind such a trait are homologous, for example, the ability to degrade glucose to pyruvate using the glycolytic pathway. However, a similar trait can also arise independently in different lineages, and this is called convergent evolution, for example, wings in birds and bats or the antifreeze proteins in Arctic and Antarctic fish17. If two independent lineages share a similar niche and acquire similar traits, then we can talk about parallel evolution. Our results can now help to reconstruct the original environment and evolutionary trends that operated within the yeast community more than 100 mya. We think that at that time many different yeast lineages shared a similar ecospace that was relatively poor in simple sugars. However, several niches became enriched by larger amounts of simple mono- and oligo-saccharides from the excess fruits emerging at the end of the Cretaceous age18. Several yeasts could apparently evolve their carbon metabolism to produce toxic metabolites killing other competing microbes, and, in parallel, also developed resistance towards these metabolites. We show here that this trait, the 'make–accumulate–consume' survival strategy, evolved in at least two lineages, post-WGD and Dekkera yeasts, using a similar molecular pathway, a global rewiring of the transcription network. Such 'coincidental' events are actually not so rare in nature. For example, TRIM5-cyclophilin gene fusions providing anti-viral activity19 and opsins involved in photo-transduction20 were recruited repeatedly by different organisms and evolved using similar molecular processes. Such repetitions of the evolutionary pathways could be a consequence of a strong and well-defined environmental pressure narrowing the number of possible molecular scenarios to acquire a new trait.

Methods

Carbon metabolism

Batch cultivations were performed in a Biostat-Q system (B-Braun) at the working volume of 0.8 l. For experiments performed in aerobic conditions, an airflow of 0.8 l min−1 and a stirrer speed of 500 r.p.m. maintained a dissolved oxygen concentration above 30% of air saturation, measured by a Mettler Toledo polarographic oxygen probe. The culture pH was maintained at 5.0 by KOH 2 M. The cell biomass from pre-inoculum was washed and used to inoculate batch cultures on defined mineral medium prepared as reported21 and containing the carbon source (glucose 7–20 g l−1). Anaerobic cultures were flushed with certified nitrogen gas containing less than 2 p.p.m. of oxygen at a flow rate of 0.12 l min−1, equivalent to 0.15 l per litre of medium per minute. In order to minimize oxygen diffusion into the bioreactor, Norprene tubes were used for the entire fermentor set-up. For anaerobic cultures uracil, Tween 80, ergosterol and casamino acids were added to the defined mineral medium at concentrations of 50, 420, 10 and 0.5 g l−1.

The amounts of glucose, glycerol, ethanol, acetate and lactate in the supernatants were determined with R-Biopharm (Roche Diagnostics) enzymatic kits (0716251, 10148270035, 10176290035, 0148261, 1112821, respectively). Pyruvate was detected in assay mixtures containing 100 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.6), 0.3 mM NADH, 1.5 mM EDTA and the sample; the concentration of pyruvate was calculated from the decrease in extinction at 340 nm after the addition of 2 U of lactate dehydrogenase (Roche). All samples were analysed in triplicate and the values of standard deviation obtained varied between 1–2%. Specific rates were calculated during the exponential growth phase. Biomass, ethanol, glycerol and acetic acid yields are derived from glucose. For this reason, they were calculated just before the end of growth on glucose, when there was still some residual carbon source present in the medium. For the dry weight determinations, washed culture samples were filtered on a 0.45 μm glass microfibre GF/A filter (Millipore) and dried for 24 h at 80 °C. Parallel samples varied of about 3–5%.

Phylogenetic analysis

The phylogenetic relationship based on the nuclear 26S rDNA and mitochondrial 15S rDNA sequences from different yeast species (see Supplementary information) were analysed using the neighbour–joining method.22 A detailed analysis of D. bruxellensis relationship with other yeasts can also be found in ref. 15.

For the 15S rDNA sequences, the optimal tree with the sum of branch length=0.60941220 is shown. The percentages of replicates in which the associated taxa clustered together in the bootstrap test (500 replicates) are shown next to the branches. The phylogenetic tree was linearized assuming equal evolutionary rates in all lineages. The clock calibration to convert the distance into time was 1,441.2 (time/node height) and was calibrated according to the time estimates suggested in ref. 23. The evolutionary distances were computed using the maximum composite likelihood method and are in the units of the number of base substitutions per site. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated from the dataset (complete deletion option). In the final data set, there was a total of 333 positions. Phylogenetic analyses were conducted in MEGA4 (ref. 24). For the 26S rDNA sequences the optimal tree with the sum of branch lengths=1.02971408 is shown. The clock calibration to convert the distance into time was 3,567.9 (time/node height). In the final data set, there were a total of 475 positions.

Low pH and ethanol tolerance

Several representatives of different yeast species (see Supplementary information) were tested for their growth at low pH and high ethanol concentration, and the lowest pH and the highest ethanol concentrations that still permit the growth were recorded. Growth at low pH was determined in liquid-rich medium (1% Bacto-yeast extract, 2% Bacto-peptone, 2% glucose (YPD)). The medium pH values, from 2 to 6, were obtained with different potassium phosphate buffers at the final concentration of 0.2 M. A yeast culture in late logarithmic phase was diluted 100-fold in the corresponding buffered medium and then the OD600 nm followed. If the OD value at least doubled, then the pH value was taken as a non-inhibitory one. The final pH value of the medium, after the OD doubled, was checked. In all tested yeasts, the media with the lowest pH completely inhibited the growth. Ethanol tolerance was determined on the solid and liquid YPD media containing different ethanol concentrations. A yeast culture in late logarithmic phase was diluted 1.000-fold and dropped on the plates (which were then inspected visually) or inoculated in the liquid medium and the OD600 nm followed. In all tested yeasts, the highest EtOH concentrations tested completely inhibited the growth.

Promoter motif analysis

Genes extracted from different yeast genomes (Supplementary Table S1) were defined as rapid growth-associated (including CRP and rRNA-processing genes) or respiration-associated (including MRP genes. Rapid growth-associated genes were divided into set 1 (or rRNA) and set 2 (or CRP) following ref. 5 and are listed in Supplementary Data 1. D. bruxellensis and Y. lipolytica genes were classified on the basis of their S. cerevisiae orthologues. The MRP set and the rRNA set of S. cerevisiae, S. bayanus and K. lactis were defined according to ref. 5. Note that to the K. lactis MRP set, two relevant genes were added to the pre-defined set (YNL185C and YNR037C). The CRP genes were defined as orthologues to S. cerevisiae5 for all the species analysed. The promoter sequences were considered as the 500 bp of sequences upstream of genes and analysed for the presence of AATTTT or its reverse complement, AAAATT. The promoters were searched using a purpose-written Perl script. The occurrence of the motif in each 50-bp window within the promoter sequence was determined (Supplementary Data 2). AATTTT occurrence was counted only once in each window (even if two or more motif copies were present). The graphs shown represent the percentage of the promoters that contain the AATTTT motif in each window. The repeated-measures analysis of variance was used to determine the significance of the motif distribution patterns.

Transcription studies

The genes for the transcription studies were chosen based on the position of the motif in their promoter sequences. For the post-WGD species (S. cerevisiae and S. bayanus) and D. bruxellensis, CRP genes (promoters contain the AATTTT motif within the highest frequency region) and MRP respiration genes (promoters do not contain the motif in the 'preferred' region) were studied. For the pre-WGD species, both respiration- and rapid growth-associated genes with the motif at the fixed position were studied.

The yeasts used in the transcription study were grown on the defined minimal medium (Yeast Nitrogen Base: 1.7 g l−1; 5 g l−1 ammonium sulphate) with the supplement of glucose (20 g l−1) or ethanol (10 g l−1) as carbon source to promote fermentative or oxidative metabolism. The cultures of 100 ml were grown in the 1-l flasks at 30 °C. Proper aeration was ensured by stirring of 200 r.p.m. in the rotative incubator. In all, 12 ml of cells in the exponential growth phase were harvested at 2,850 g for 10 min and then resuspended in 200 μl RNA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4; 100 mM NaCl; 10 mM EDTA) and 400 μl acidic phenol (pH 4.3). Cells were broken using acid-washed glass beads for 3 min with incubation on ice every 1 min. RNA buffer (200 μl) and 10% SDS (40 μl) were added and the mix was incubated for 6 min on 65 °C followed by centrifugation at 16,060 g for 15 min. Acidic phenol (400 μl) and 3 M NaOAc (40 μl) were added to the water phase. After centrifugation at 16,060 g for 15 min, 1 ml of 96% ethanol was added and the mix was incubated overnight at −20 °C. The precipitated RNA was spun down at 4 °C for 10 min. The pellet was washed with 70% ethanol, spun down at 4 °C for 5 min, dried and suspended in DEPC-treated water. The concentration of the RNA was measured on NanoDrop spectrophotometer and the integrity was analysed on Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. In all, 1 μg of RNA was used for the synthesis of cDNA using SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase kit from Invitrogen (Cat. no. 18080-044) with RNaseOUT Ribonuclease Inhibitor from Invitrogen (Cat. no. 10777-019) and random primers from Invitrogen (Cat. no. 48190-011). RNA was isolated from at least two independent growth experiments and in most cases each RNA batch was then analysed at least two times.

The expression studies were carried out using SYBR GreenER qPCR SuperMix from Invitrogen (Cat. no. 11762-500) with the cDNA as a template and the specific primers (Supplementary Table S2). The PCRs were run as duplicates in RotorGene 2000 with the conditions specified by Invitrogen. The take-off and the amplification values, obtained from the relative quantification performed using the RotorGene 2000 software, were used to quantify the expression ratios of CRPs and MRPs with the help of REST 2009 V2.0.13 with RG mode25. The α-tubulin gene was treated as endogenous reference. The cDNA sample drawn from the culture grown on ethanol was regarded as a control sample (untreated). The cDNA prepared from the total RNA isolated from yeast cultures grown on glucose was regarded as the treated sample. The results were presented as a Whisker box plot.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Rozpędowska, E. et al. Parallel evolution of the make-accumulate-consume strategy in Saccharomyces and Dekkera yeasts. Nat. Commun. 2:302 doi: 10.1038/ncomms1305 (2011).

References

- Pronk, J. T., Steensma, H. Y. & van Dijken, J. P. Pyruvate metabolism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 12 1607–1633 (1996).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Thomson, J. M. et al. Resurrecting ancestral alcohol dehydrogenases from yeast. Nat. Genet. 37 630–635 (2005).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Piskur, J., Rozpedowska, E., Polakova, S., Merico, A. & Compagno, C. How did Saccharomyces evolve to become a good brewer? Trends Genet. 22 183–186 (2006).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Wolfe, K. H. & Shields, D. C. Molecular evidence for an ancient duplication of the entire yeast genome. Nature 387 708–713 (1997).

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Ihmels, J. et al. Rewiring of the yeast transcriptional network through the evolution of motif usage. Science 309 938–940 (2005).

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Dujon, B. et al. Genome evolution in yeast. Nature 430 35–44 (2004).

Article ADS Google Scholar - Jiang, H., Guan, W., Pinney, D., Wang, W. & Gu, Z. Relaxation of yeast mitochondrial functions after whole-genome duplication. Genome Res. 18 1466–1471 (2008).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Replansky, T., Koufopanou, V., Greig, D. & Bell, G. Saccharomyces sensu stricto as a model system for evolution and ecology. Trends Ecol. Evol. 23 494–501 (2008).

Article Google Scholar - Merico, A., Sulo, P., Piskur, J. & Compagno, C. Fermentative lifestyle in yeasts belonging to the Saccharomyces complex. FEBS J. 274 976–989 (2007).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Cai, J., Roberts, I. N. & Collins, M. D. Phylogenetic relationships among members of the ascomycetous yeast genera Brettanomyces, Dekkera, and Kluyveromyces deduced by small-subunit rRNA gene sequences. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 46 542–549 (1996).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Renouf, V. et al. Interactions between Brettanomyces bruxellensis and other yeast species during the initial stages of winemaking. J. Appl. Microbiol. 100 1208–1219 (2006).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Van Dijken, J. P. & Scheffers, W. A. Redox balances in the metabolism of sugars by yeasts. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 32 199–224 (1986).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Aguilar Uscanga, M. G., Delia, M. L. & Strehaiano, P. Brettanomyces bruxellensis: effect of oxygen on growth and acetic acid production. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 61 157–162 (2003).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Nissen, T. L., Hamann, C. W., Kielland-Brandt, M. C., Nielsen, J. & Villadsen, J. Anaerobic and aerobic batch cultivations of Saccharomyces cerevisiae mutants impaired in glycerol synthesis. Yeast 16 463–674 (2000).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Woolfit, M., Rozpedowska, E., Piskur, J. & Wolfe, K. H. Genome survey sequencing of the wine spoilage yeast Dekkera (Brettanomyces) bruxellensis. Eukaryot. Cell 6 721–733 (2007).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Hellborg, L. & Piskur, J. Complex nature of the genome in a wine-spoilage yeast, Dekkera bruxellensis. Eukaryot. Cell 8 1739–1749 (2009).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Chen, L., DeVries, A. L. & Cheng, C.- H. C. Convergent evolution of antifreeze glycoproteins in Antarctic notothenioid fish and Arctic cod. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 94 3817–3822 (1997).

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Friis, E. M., Chaloner, W. G. & Crane, P. R. The Origins of Angiosperms and their Biological Consequences (Cambridge University Press, 1987).

- Stoye, J. P. & Yap, M. W. Chance favors a prepared genome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105 3177–3178 (2008).

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Fernald, R. D. Casting a genetic light on the evolution of eyes. Science 313 1914–1918 (2006).

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Verduyn, C., Potsma, E., Scheffers, W. A. & van Dijken, J. P. Effect of benzoic acid on metabolic fluxes in yeasts: a continuous-culture study on the regulation of respiration and alcoholic fermentation. Yeast 8 501–517 (1992).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Tamura, K., Nei, M. & Kumar, S. Prospects for inferring very large phylogenies by using the neighbor-joining method. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101 11030–11035 (2004).

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Langkjaer, R. B., Cliften, P. F., Johnston, M. & Piskur, J. Yeast genome duplication was followed by asynchronous differentiation of duplicated genes. Nature 421 848–852 (2003).

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Tamura, K., Dudley, J., Nei, M. & Kumar, S. MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24 1596–1599 (2007).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Pfaffl, M. W., Horgan, G. W. & Dempfle, L. Relative expression software tool (REST) for group-wise comparison and statistical analysis of relative expression results in real-time PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 30 e36 (2002).

Article Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

We thank K. Wolfe for valuable discussions, E. Svensson for help on statistical evaluations and A. Rasmusson for help on qRNA analysis. We also thank the Swedish Research Council, Italian Ministry of Instruction, University and Research, and the Crafoord, Futura, Fysiografen, Lindström and Sörensen Foundations for their financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- Department of Biology, Lund University, Sölvegatan 35, Lund, 223 62, Sweden

Elżbieta Rozpędowska, Linda Hellborg, Olena P. Ishchuk, Furkan Orhan & Jure Piškur - Dipartimento di Scienze Biomolecolari e Biotecnologie, Università degli Studi di Milano, via Celoria 26, Milan, 20133, Italy

Silvia Galafassi, Annamaria Merico & Concetta Compagno - Department of Genetics, Smurfit Institute, Trinity College Dublin, Dublin, 2, Ireland

Megan Woolfit - School of Biological Sciences, University of Queensland, Brisbane, 4072, Queensland, Australia

Megan Woolfit

Authors

- Elżbieta Rozpędowska

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Linda Hellborg

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Olena P. Ishchuk

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Furkan Orhan

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Silvia Galafassi

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Annamaria Merico

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Megan Woolfit

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Concetta Compagno

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Jure Piškur

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

E.R. performed the promoter motif analysis; E.R., O.I., S.G. and F.O. performed the transcription studies; L.H. did the phylogenetic analysis; O.I. and L.H. investigated pH and ethanol tolerance; S.G., A.M. and C.C. performed the batch culture growth experiments; M.W. helped with the statistical studies; J.P. coordinated the study and wrote the manuscript; E.R. and L.H. wrote the Methods; all authors commented on and improved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence toJure Piškur.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figure S1, Supplementary Tables S1-S2 and Supplementary Methods. (PDF 127 kb)

Supplementary Data 1

Supplementary Data 1 List of genes that were examined in this study. (XLS 56 kb)

Supplementary Data 2

Supplementary Data 2 List of genes containing the AATTT motif in their promoter sequences. (XLS 52 kb)

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Rozpędowska, E., Hellborg, L., Ishchuk, O. et al. Parallel evolution of the make–accumulate–consume strategy in Saccharomyces and Dekkera yeasts.Nat Commun 2, 302 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1305

- Received: 13 December 2010

- Accepted: 08 April 2011

- Published: 10 May 2011

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1305