TRPV3 regulates nitric oxide synthase-independent nitric oxide synthesis in the skin (original) (raw)

Introduction

Nitric oxide (NO) serves as a critical signalling molecule for many biological processes, including regulation of vascular tone, synaptic plasticity and inflammation1,2,3. NO has a short half-life and high reactivity and is synthesized de novo when and where needed, predominantly from L-arginine by NO synthases (NOS). Although store-mediated NO production has been proposed4,5, the molecular identity of NO pools remains enigmatic. Nitrite (NO2−) and nitrate (NO3−), oxidation products of NO abundant in our diet, could serve as an alternative source for NO-production as they are relatively more stable than NO and can be recycled back to NO (nitrate to nitrite, then nitrite to NO)6,7. Moreover, nitrite–NO pathways do not require oxygen and thus can contribute to NO synthesis during hypoxia and acidosis, conditions that compromise NOS enzymes6,7. Nitrite–NO pathways are important in a variety of in vivo settings. Plasma nitrite can react with deoxyhemoglobin, deoxymyoglobin and xanthine oxydoreductase to form NO6,8,9,10,11. Acid converts salivary nitrite to NO in the stomach12,13. Ultraviolet light reduces nitrite in the skin or sweat14,15. Nitrite–NO pathways mostly occur in the extracellular milieu or are regulated by extracellular chemical environments. Whether nitrite–NO pathways are modulated by canonical signalling pathways, such as activation of membrane-spanning receptors, is not known.

In the skin, NO is produced in many cell types and has important roles in keratinocyte differentiation, inflammation, wound healing and many other biological processes16. Skin cells experience drastic thermal variations compared with other tissues, and NO is produced in the skin upon warming17. Keratinocytes, prevalent cells in the skin epidermis, produce NO in response to various stimuli, but the underlying mechanisms are not well understood16. Keratinocytes express a heat-sensitive transient receptor potential (TRP) ion channel, TRPV3 (ref. 18), that has a role in thermosensation19, hair morphogenesis, keratinocyte development and skin barrier formation20.

In this study, we show that TRPV3 regulates NO production in keratinocytes via the nitrite pathway, with physiologically relevant consequences in vivo.

Results

TRPV3 induces NOS-independent NO production in keratinocytes

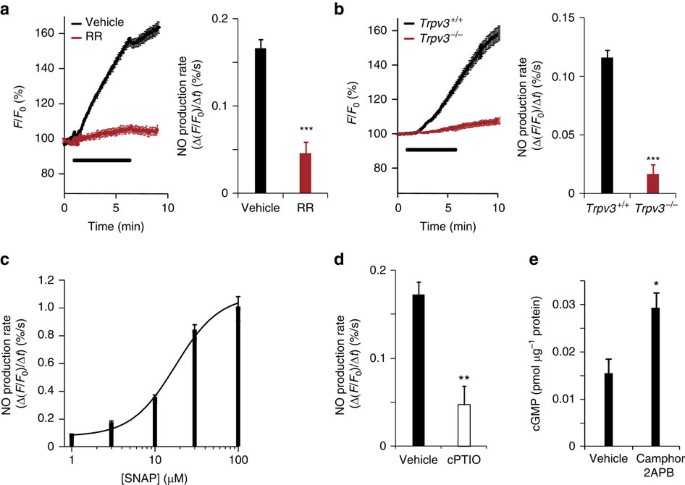

We tested whether activation of TRPV3 induces NO production in primary cultured keratinocytes using a specific NO-sensitive fluorescent dye (DAF-FM: 4-amino-5-methylamino-2′,7′-difluorofluorescein diacetate)21. A significant fluorescent increase indicating NO production was observed (Fig. 1a,b; black) upon co-application of TRPV3 agonists camphor (1 mM, ~EC20) and 2APB (2-aminoethyoxydiphenyl borate, 100 μM, EC100)19,22,23. This cocktail elicited a robust and specific TRPV3-dependent calcium response in keratinocytes. We were unable to test individual chemical agonists or heat as specific TRPV3 activators on keratinocytes due to their relatively low efficacy in calcium-imaging experiments (Supplementary Fig. S1a,b). NO irreversibly modifies DAF-FM fluorescence21, and thus the slope of the normalized fluorescence (Δ(F/F_0)/Δ_t, %/s) reflects the rate of NO production (RNO). Cocktail-induced increase in RNO (RNO(TRPV3)) was attenuated by a non-specific TRP channel blocker ruthenium red (RR) and in keratinocytes from _Trpv3_−/− littermates (Fig. 1a,b; red). These results confirm a specific requirement of TRPV3 and exclude any potential non-specific effects on DAF-FM by camphor and 2APB. We also calibrated RNO to concentrations of an NO donor SNAP (_S_-nitroso-_N_-acetylpenicillamine) using CHO (Chinese hamster ovary) cells loaded with DAF-FM. The levels of TRPV3-dependent NO production are similar to those released by ~3 μM SNAP, which are sufficient (>EC100) to induce smooth muscle relaxation24, suggesting potential biological relevance of TRPV3-dependent NO production (Fig. 1c).

Figure 1: TRPV3 induces NO production in keratinocytes.

(a) Representative changes in normalized fluorescence of NO-sensitive dye DAF-FM (F/_F_0, %; left) and averaged NO production rate (RNO, represented by the rate of fluorescence-increase determined from a line-fit of the F/_F_0 trace during stimulus; Δ(F/F_0)/Δ_t, %/s; right) of wild-type keratinocytes incubated with either a nonspecific TRP channel blocker ruthenium red (RR; 30 μM, red, _n_=6 experiments in bar graph) or vehicle (0.3% DMSO, black, _n_=7) for 3 min before and throughout addition of TRPV3 agonists (1 mM camphor and 100 μM 2APB, horizontal bar). (b) Representative changes in F/_F_0 (left) and averaged RNO (right) of Trpv3+/+ (black, _n_=5) or _Trpv3_−/− (red, _n_=7) keratinocytes in response to TRPV3 agonists (horizontal bar). (c) Calibration of the RNO; averaged RNO in CHO cells in response to various concentrations of a NO donor SNAP (_n_=3 per point). (d) RNO in wild-type keratinocytes treated with a NO scavenger cPTIO (0.5 mM; clear, _n_=5) or vehicle (0.5% water; filled, _n_=5) in response to TRPV3 agonists. Keratinocytes were incubated with cPTIO or vehicle for 30 min before and throughout application of TRPV3 agonists. (e) cGMP levels in primary keratinocytes treated with vehicle (left, _n_=5) or TRPV3 agonists (right, _n_=12). Data are represented as mean±s.e.m. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, unpaired two-tailed _t_-test.

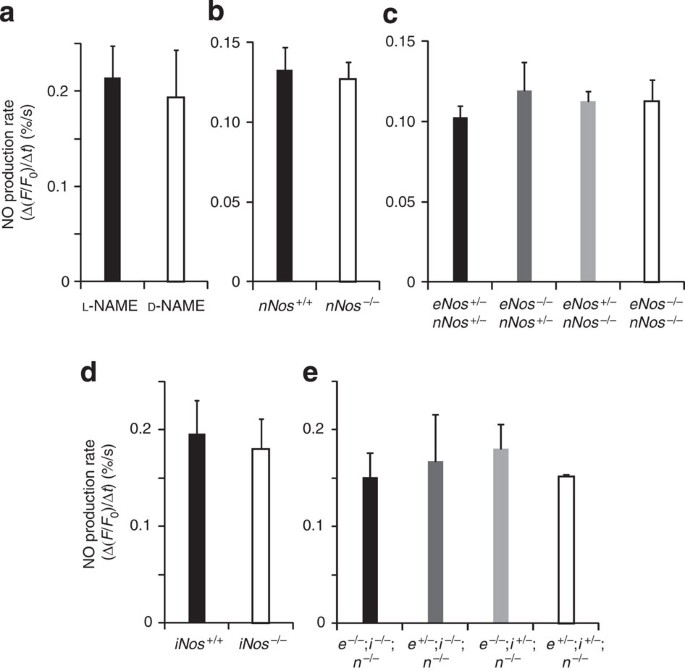

We further confirmed that the TRPV3-dependent signal is mediated by NO and not by oxidants and radicals other than NO21 using a specific membrane-permeable NO scavenger cPTIO (2-(4-carboxyphenyl)-4,4,5,5-tetramethylimidazoline-1-oxy-3-oxide). cPTIO effectively attenuated RNO(TRPV3), without affecting TRPV3 functionality (Fig. 1d; Supplementary Fig. S1c). TRPV3 activation also increased cGMP, consistent with an effect of NO production (Fig. 1e). Surprisingly, L-NAME (_N_ω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester), an inhibitor of all three NOS enzymes, had no effect on RNO(TRPV3) compared with its inactive isomer D-NAME (_N_ω-Nitro-D- ) (Fig. 2a). We confirmed this finding genetically by examining keratinocytes from single and combinatorial NOS-deficient mice. All three NOS enzymes can be expressed in keratinocytes16, but we first focused on nNOS and eNOS, two calcium-dependent subtypes, because calcium permeates TRPV3. nNOS is predominant in keratinocytes16, and eNOS compensates for the loss of nNOS in other tissues25. Keratinocytes from _nNos_−/− or _nNos_−/−;_eNos_−/− mice showed normal RNO(TRPV3) (Fig. 2b,c). Deletion of iNOS, a calcium-independent subtype, also had no effect on RNO(TRPV3) (Fig. 2d). Finally, normal RNO(TRPV3) was observed in keratinocytes from mice lacking all three NOSs (Fig. 2e). Together, these results indicate that TRPV3 induces NOS-independent NO production.

Figure 2: TRPV3-mediated NO production is NOS-independent.

RNO in primary keratinocytes in response to TRPV3 agonists (1 mM camphor and 100 μM 2APB). (a) Wild-type keratinocytes treated with a pan-NOS inhibitor L-NAME (1 mM; filled, _n_=5) or its inactive isomer D-NAME (1 mM; filled, _n_=5) for 30 min before and throughout application of TRPV3 agonists. (b) Keratinocytes from nNOS+/+ (filled, _n_=9) and _nNOS_−/− (clear, _n_=9) mice. (c) Keratinocytes of indicated genotypes; numbers of experiments are (left to right) _n_=3, 4, 5, 6. (d) Keratinocytes from iNOS+/+ (filled, _n_=8) and _iNOS_−/− (clear, _n_=13) mice. (e) Keratinocytes of indicated genotypes; numbers of experiments are (left to right) _n_=5, 2, 2, 2 (e, i, and n represent eNos, iNos, and nNos, respectively). Data are represented as mean±s.e.m.

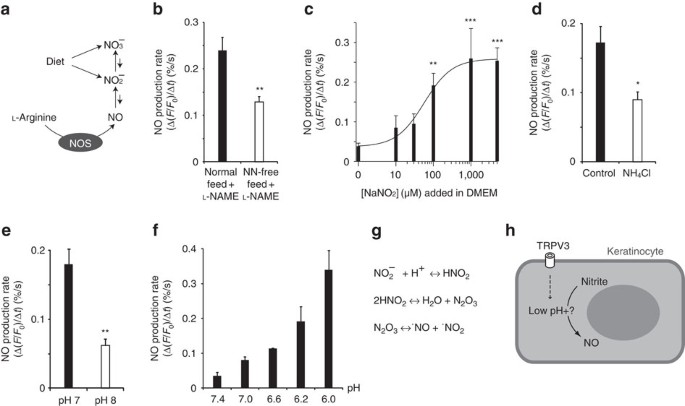

TRPV3-mediated NO production requires nitrite and low pH

We tested whether TRPV3-induced NO production involved nitrite pathways6,7, because human skin is enriched in nitrites15 and modestly hypoxic26. Two major nitrite sources are dietary intake (in forms of nitrate or nitrite) and endogenously produced oxidation products of NO itself6,7 (Fig. 3a). Nitrite and nitrate are lost from the body at a significant rate through urine, saliva and sweat, and thus they have relatively short in vivo half-lives7. Indeed, in vivo nitrite/nitrate levels can be readily depleted in mice by controlling dietary nitrite/nitrate and NOS activity27, enabling us to examine the requirement of nitrites using keratinocytes from nitrite-deprived mice. Keratinocytes from nitrite-deprived mice showed a marked reduction in RNO(TRPV3), whereas those from L-NAME-administered mice showed normal RNO(TRPV3) (Fig. 3b). TRPV3 channel activity itself was not compromised, only downstream NO formation in nitrite-deprived keratinocytes (Supplementary Fig. S2a). The attenuation of NO production by nitrite deprivation was not as severe as observed for RR treatment or in _Trpv3_−/− mice (Fig. 1a,b), presumably due to residual nitrites in the media or otherwise incomplete nitrite-depletion.

Figure 3: Nitrite and intracellular acidification are required for TRPV3-mediated NO production.

(a) The NOS- and nitrite (NO2−)-dependent pathways for NO production (nitrate (NO3−)). Modified from Suscheck et al.7 (b) RNO during application of TRPV3 agonists (1 mM camphor and 100 μM 2APB) in keratinocytes from wild-type mice given L-NAME (1 g per l in drinking water) and nitrite/nitrate/L-arginine-free feed for 5 days (clear, _n_=10) and mice given L-NAME and normal feed for 5 days (filled, _n_=13). (c) RNO in CHO cells co-transfected with mTRPV3 and mCherry-reporter in response to camphor (5 mM). Cells were cultured overnight in either DMEM (the leftmost column without NaNO2 addition shows the basal rate) or DMEM supplemented with various indicated concentrations of NaNO2 (_n_=4–12 per point). (d,e) RNO in wild-type keratinocytes treated with extracellular salines for 3 min before and throughout application of TRPV3 agonists (1 mM camphor and 100 μM 2APB). In (d), control saline (filled, _n_=5) contained (in mM): 126 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 10 HEPES (pH7.4), and NH4Cl saline (clear, _n_=4): 50 NH4Cl, 76 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 10 HEPES (pH7.4). In (e), standard Hanks with 10 mM HEPES (pH7.0; filled, _n_=3) was adjusted to pH8.0 (clear, _n_=5) with NaOH. (f) RNO of wild-type keratinocytes in response to intracellular pH changes using K+N buffer (_n_=2–4 per point). K+N buffer contained (in mM): 5 NaCl, 126 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, with 10 μM protonophore nigericin (pH7.4). TRPV3 agonists were not applied. (g) Chemical reactions for proton-mediated nitrite-reduction proposed by Benjamin et al.12 (h) A model for the potential mechanism of TRPV3-dependent NO production. Bars represent mean±s.e.m. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, unpaired two-tailed _t_-test except for (c), and one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's test in (c).

Interestingly, whereas primary keratinocytes produce NO upon TRPV3 activation, CHO cells expressing mouse TRPV3 (CHOmTRPV3) do not show a significant increase in RNO(TRPV3) (Fig. 3c). We hypothesized that the lack of NO production in the heterologous system was due to low levels of nitrites. Strikingly, after culturing CHOmTRPV3 in media supplemented with sodium nitrite (NaNO2) at 100 μM or above, a robust increase in RNO(TRPV3) was observed (Fig. 3c). The required extracellular nitrite concentration for CHOmTRPV3 is several folds higher than that in the skin (15 μM)15 and may be due to more efficient nitrite-uptake/storage in keratinocytes. Nitrite specifically enhances TRPV3-mediated NO production, since culturing CHOmTRPV3 in NaNO2-supplemented media had no effect on TRPV3 functionality (Supplementary Fig. S2b).

A few potential pathways are known to reduce nitrites6,7. Deoxyhaemoglobin or deoxymyoglobin are unlikely to be involved as they are not present in keratinocytes. Nitrite-reduction via xanthine oxidoreductase and aldehyde oxydase 1 is a possibility28; however, these genes are not expressed in keratinocytes at significant levels, and inhibitors of these enzymes28 did not block RNO(TRPV3) (Supplementary Fig. S2c). Proton-mediated nitrite-reduction has been postulated, and we tested whether increasing pH would block NO production. Remarkably, extracellular ammonium chloride (NH4Cl acts as an intracellular base29) or basic buffer (pH8.0 increases intracellular pH within minutes) each attenuated RNO(TRPV3) without affecting TRPV3 functionality (Fig. 3d,e; Supplementary Fig. S2d,e).

We asked whether acidification was sufficient for NO production, utilizing buffer solutions containing high potassium and the protonophore nigericin (K+N buffer) buffered to various pH levels to rapidly set the intracellular pH to the extracellular pH29. Consistent with our hypothesis, RNO increased as pH was lowered in the absence of TRPV3 agonists (Fig. 3f). It is unlikely that this result is due to a direct effect of pH on DAF-FM, because DAF-FM fluorescence decreases at low (<5.0) pH levels21.

S-nitrosothiols are involved in NOS-independent NO production4,15; their levels are high in the skin and are potentially affected by nitrite levels. Thus, their involvement cannot be excluded. However, TRPV3-induced NO production is modulated by intracellular pH, consistent with acid-induced nitrite-reduction (Fig. 3d–f), and our data collectively argue that TRPV3-dependent NO production occurs via nitrite-reduction (Fig. 3g,h).

We also examined whether TRP channels closely related to TRPV3 induce nitrite-reduction. CHOTRPV1 and CHOTRPV4 cultured in NaNO2-supplemented DMEM showed small but significant increases in RNO (Supplementary Fig. S3a,b). Activation of TRPV4, expressed in keratinocytes30, could induce NO production, but at a much lower level than TRPV3 activation (Supplementary Fig. S3c,d). Therefore, nitrite-reduction may occur downstream of other TRP channels, but the level of NO production in our assay is minor compared with that by TRPV3.

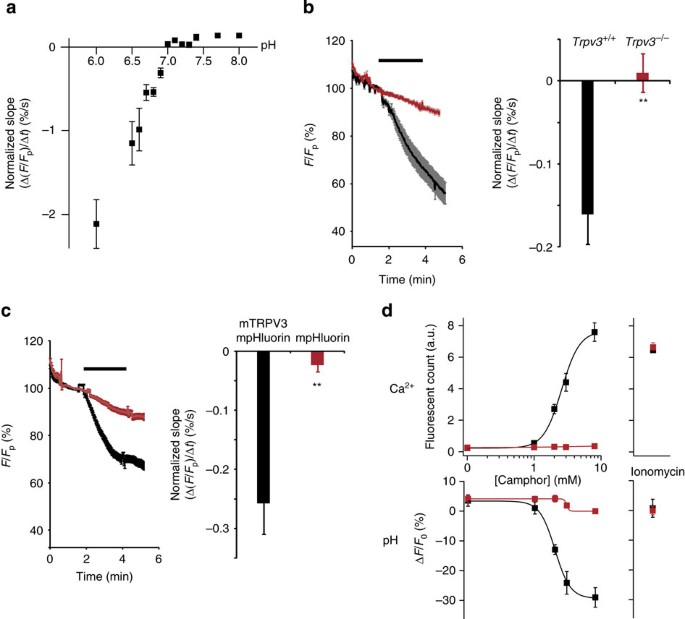

TRPV3 activation induces only modest acidification

We next determined whether TRPV3 induces intracellular acidification using pHluorin, a pH-sensitive GFP variant with pKa=7.1 (ref. 31). We attached a myristoylation signal at the N-terminus of pHluorin (mpHluorin) to read out intracellular pH in the proximity of the plasma membrane. As mpHluorin-expressing cells showed a baseline decrease in fluorescence owing to photobleaching, normalized slope [Δ(F/F_p)/Δ_t, %/s] was used as an indicator of intracellular pH (Methods). The normalized slope was first calibrated against cellular pH using CHOmpHluorin and K+N buffer (Fig. 4a).

Figure 4: TRPV3 activation induces modest intracellular acidification.

(a) Calibration of the normalized slope to known changes in intracellular pH, using CHO cells transfected with mpHluorin and K+N buffers at the indicated pH (at least _n_=3 per point). To calculate the normalized slope, mpHluorin fluorescence values of individual cells were first normalized to the level just prior to agonist application (F/_F_p, %). The slope of F/_F_p under basal conditions (representing the photobleaching rate) is subtracted from the slope during stimuli (representing the summed rates of photobleaching and intracellular pH changes) to have the normalized slope (Δ(F/F_p)/Δ_t) (%/s). (b) Representative changes of normalized mpHluorin intensity (F/_F_p; left) and averages of normalized slope (right) in Trpv3+/+ (black, _n_=8 for bar graph) and _Trpv3_−/− (red, _n_=5) keratinocytes electroporated with mpHluorin-encoding plasmid upon application of TRPV3 agonists (horizontal bar). (c) Representative changes of normalized mpHluorin intensity (F/_F_p; left) and averages of normalized slope (right) in CHO cells transiently transfected with mTRPV3 and mpHluorin (black, _n_=7) or mpHluorin only (red, n_=5) in response to camphor (3 mM; horizontal bar). (d) A FLIPR assay showing arbitrary fluorescence counts of Fluo-3 loaded cells (calcium indicator, top) and normalized changes in mpHluorin intensity (pH indicator, bottom, %) of HEK293T cells transiently transfected with mTRPV3 and mpHluorin (black) or mpHluorin only (red) in response to camphor at various concentrations (left) and calcium ionophore ionomycin (3 μM, right). As photobleaching was not observed in FLIPR, the change in mpHluorin intensity (Δ_F/_F_0, %) was plotted. Data are represented as mean±s.e.m. **P<0.01, unpaired two-tailed _t_-test.

Primary cultured keratinocytes electroporated with mpHluorin showed a steeper negative normalized slope (that is, acidification) upon TRPV3 activation, and this acidification was absent in keratinocytes from _Trpv3_−/− mice (Fig. 4b). CHOTRPV3;mpHluorin also showed an increased negative slope upon TRPV3 activation (Fig. 4c). It is unclear whether intracellular pH recovered to the baseline level after agonist washout due to photobleaching. Finally, TRPV3-dependent acidification was observed in HEK293T (human embryonic kidney) cells transfected with TRPV3 and mpHluorin, as assayed by fluorometric imaging plate reader (FLIPR) (Fig. 4d). Similar results were obtained with normal pHluorin (Supplementary Fig. S4), suggesting that TRPV3-mediated acidification occurs throughout the cytosol. Ionomycin, which increases intracellular calcium levels, induced no change in mpHluorin intensity (Fig. 4d), arguing that intracellular acidification is not a general consequence of increased intracellular calcium levels.

Comparisons with calibration curves reveal TRPV3-activation causes relatively minor acidification (from pH7.0 to pH6.9). However, pH6.9 alone is insufficient to induce NO production at levels observed after TRPV3 activation (compare Fig. 3f with 3d,e). This suggests that TRPV3-mediated cellular acidification accounts for only a part of the NO production mechanism; alternatively, TRPV3 activation could cause significant spatially restricted acidification to drive NO production. Regardless, we show that low pH contributes to RNO(TRPV3).

TRPV3 activation could induce cellular acidification through direct or indirect mechanisms. If indirect, this process would require presumably ubiquitous factors, as we observe acidification in three different cell types. Cellular acidification is likely due to influx of extracellular protons, as negative resting membrane potential is required for acidification (Supplementary Fig. S5). We examined whether TRPV3 conducts protons because closely related TRPV1 is permeable to protons32. Using the whole-cell voltage clamp configuration, we recorded from CHOTRPV3 in the presence of TRPV3 agonists with NMDG+ and protons as the only extracellular and intracellular cations. NMDG+ is a large cation to which TRPV3 is less permeable than Na+ (ref. 33), and was used to maintain cellular electroneutrality while improving our ability to detect small proton-mediated currents. We failed to detect a current that was dependent on the electrochemical gradient for protons. However, given the relatively minor acidification induced by TRPV3 activation, we cannot rule out that proton conductance below the level of detection by our electrophysiological recordings could induce nitrite-reduction.

TRPV3-mediated thermosensory behaviour requires nitrite

Although skin cells routinely experience temperatures that activate TRPV3, the role of TRPV3 in the skin remains largely unknown. We have previously reported that _Trpv3_−/− mice (in the mixed background of C57BL/6J and R1 ES cell derived 129X1/SvJ and 129S1/Sv-+p+Try-c Kitl Sl-J/+) show a specific deficit in heat sensation as assayed by a hot plate (noxious heat) and temperature choice test (innocuous heat)19. We have since backcrossed _Trpv3_−/− mice to both pure C57BL/6J and 129S1/SvImJ backgrounds. Interestingly, C57BL/6J _Trpv3_−/− mice did not show any detectable deficit in heat sensation (Supplementary Fig. S6). However, _Trpv3_−/− mice exhibited thermosensory deficits in the 129S1/SvImJ background, and one of these phenotypes was observed only in females (Figs 5 and 6). We thus focused on mice in the 129S1/SvImJ background.

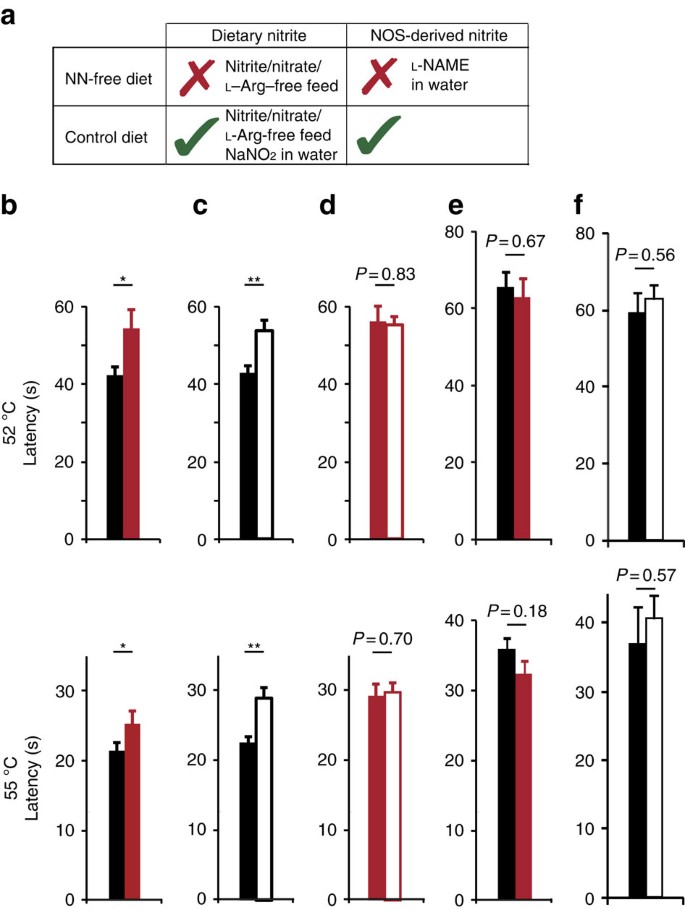

Figure 5: Nitrite and TRPV3 are required for normal nociceptive thermosensory behaviours.

(a) Description of the NN-free and control diets. (b–f) Hot plate assay testing responses of littermates (both males and females in the 129S1/SvImJ background) to noxious heat (top: 52 °C, bottom: 55 °C). Genotypes are represented in colour (black; wild type, red: _Trpv3_−/−) and diets are in fill (control or normal) or clear (NN-free) bars. Numbers of mice tested are as follows (left to right): _n_=38, 31 (b; mice on normal diet), _n_=30, 29 (c; wild-type mice on control or NN-free diet), _n_=22, 20 (d; _Trpv3_−/− mice on control or NN-free diet), _n_=19, 21 (e; mice on normal diet administered with TRPV1 antagonist AMG517 (3 mg per kg, i.p.)), and _n_=10, 10 (f; wild-type mice on control or NN-free diet administered with AMG517). AMG517 was administered daily for 3 consecutive days prior to behavioural assays, ensuring that the transient hyperthermia caused by the TRPV1 antagonist is tolerated. Data are represented as mean±s.e.m. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, unpaired two-tailed _t_-test.

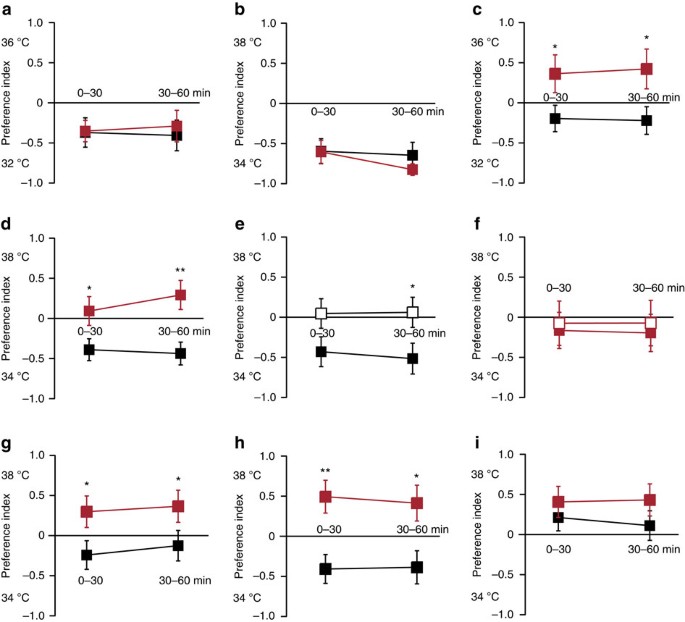

Figure 6: Nitrite and TRPV3 are required for normal innocuous thermosensory behaviours.

Thermal choice assay testing the preference between two innocuous warm temperatures (indicated at the left of each panel: either 32 versus 36 °C or 34 versus 38 °C) of littermates in the 129S1/SvImJ background. Preference index over an hour in 30 min intervals is shown. Genotypes are represented in colour (black; wild-type, red: _Trpv3_−/−) and diets are in fill (control or normal) or clear (NN-free) squares. (a, b) Trpv3+/+ (black, _n_=20) and _Trpv3_−/− males (red, _n_=17) on normal diet in 32 versus 36 °C (a) or in 34 versus 38 °C (b) choice assay. (c, d) Trpv3+/+ (black, _n_=31) and _Trpv3_−/− females (red, _n_=21) on normal diet in 32 versus 36 °C (c) or in 34 versus 38 °C (d) choice assay. (e) Wild-type females on either the control (filled, _n_=16) or NN-free (clear, _n_=18) diet. (f) _Trpv3_−/− females on either the control (filled, _n_=14) or NN-free (clear, _n_=12) diet. (g) Wild-type (black, _n_=26) and _Trpv3_−/− (red, _n_=21) females on normal diet administered with TRPV1 antagonist AMG517 (3 mg per kg i.p. for 3 consecutive days). (h) Wild-type (black, _n_=19) and _Trpv3_−/− (red, _n_=17) females on normal diet administered with TRPA1 antagonist HC030031 (150 mg per kg i.p.). (i) Wild-type (black, _n_=26) and _Trpv3_−/− (red, _n_=21) females on normal diet administered with both TRPV1 and TRPA1 antagonists. Data are represented as mean±s.e.m. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, unpaired two-tailed _t_-test.

As TRPV3-dependent behavioural assays are based on temperature sensitivity, we first confirmed that heat can induce NO production in cultured cells using FLIPR and the temperature-control device34. Upon heating, a robust increase in DAF-FM fluorescence was observed in TRPV3-expressing HEK293T cells cultured in NaNO2-supplemented DMEM (Supplementary Fig. S7), suggesting that NO production is independent of the mode of TRPV3 activation.

We asked whether nitrite-deprived wild-type and _Trpv3_−/− mice behaved similarly. For nitrite deprivation, mice were treated with nitrite/nitrate/L-arginine-free feed and L-NAME in the drinking water (NN-free diet, Fig. 5a). Because the NN-free diet caused some weight loss, a control group was given the same feed but supplemented with NaNO2 without L-NAME in the drinking water, providing both nitrite sources (control diet, Fig. 5a). Mice on the NN-free and the control diet showed comparable reductions in body weight (Supplementary Fig. S8a), allowing further experimentation. We first examined noxious thermosensory behaviour (hot plate assay) in which both _Trpv3_−/− males and females show longer withdrawal latencies compared with wild-type littermates (Fig. 5b). Interestingly, wild-type mice on the NN-free diet (wildtypeNN-free) showed longer withdrawal latencies compared with wildtypecontrol, similar to the phenotype of _Trpv3_−/− mice (Fig. 5c). Importantly, _Trpv3_−/− mice were not further impaired by the NN-free diet (Fig. 5d). L-NAME alone had no effect on hot plate latency, confirming nitrites, but not NOS enzymes, cause the change in thermosensory behaviour (Supplementary Fig. S8b). These results are consistent with nitrites and TRPV3 acting in the same pathway and argue against the possibility that nitrite deprivation influences thermosensory behaviour TRPV3-independently. The NN-free diet did not affect mechanical sensitivity, implying that nitrite deprivation does not cause global deficits in somatosensation (Supplementary Fig. S8c).

Thermosensation is primarily encoded by a subset of sensory neurons of dorsal root ganglia (DRG)35. TRPV1, expressed in a subset of DRG, has a direct and prominent role in noxious heat sensation36. We tested whether the TRPV3- and nitrite-dependent hot plate phenotype is dependent on the presence of functional TRPV1. Because Trpv1 and Trpv3 are less than 10 kb apart and mice lacking both TRPV1 and TRPV3 are not currently available, we utilized a specific TRPV1 antagonist AMG517 (ref. 37) to block TRPV1 in vivo. We did not observe a TRPV3- and nitrite-dependent phenotype in the hot plate assays after AMG517 administration; Trpv3+/+ and _Trpv3_−/− littermates (Fig. 5e), and wildtypeNN-free and wildtypecontrol (Fig. 5f) showed comparable hot plate latencies. These results suggest that TRPV1 potentially acts in the same pathway as TRPV3 and nitrites to regulate heat nociception, although the possibility of two independent parallel pathways cannot be excluded. Interestingly, we have previously shown that TRPV1 is activated by NO in vivo38.

We also investigated whether the deficit in innocuous warm sensory behavior observed in _Trpv3_−/− mice was dependent on nitrites. Multiple two-temperature choice assays in 129S1/SvImJ mice identified the strongest TRPV3-dependent phenotypes at 32 versus 36 °C and 34 versus 38 °C. Wild-type females and males spent more time on the cooler sides; however, _Trpv3_−/− females, but not _Trpv3_−/− males, showed a profound phenotype in these choice assays, gravitating towards the warmer side (Fig. 6a–d). Interestingly, similar to _Trpv3_−/− females, female wildtypeNN-free showed a shift in preference towards the warmer side when compared with female wildtypecontrol (Fig. 6e). Importantly, the NN-free diet had no effect on thermal preference of _Trpv3_−/− females (Fig. 6f), and L-NAME alone did not affect thermal preference of wild-type females (Supplementary Fig. S8d). These results suggest that TRPV3 and nitrites act in the same pathway to regulate innocuous thermosensory behaviour. Male wildtypeNN−free showed no change in thermal preference (Supplementary Fig. S8e), consistent with the sex-specific phenotype of _Trpv3_−/− mice in this assay.

We further tested whether innocuous thermosensory behaviours also involve TRPV1. AMG517 administration had no effect on thermal preference of Trpv3+/+ and _Trpv3_−/− females (Fig. 6g). TRPA1, another NO-activated ion channel expressed in DRG39, and TRPV1 are redundantly required for exogenous NO-mediated nociception38. We thus tested whether TRPV3-mediated innocuous warm sensation is dependent on both TRPV1 and TRPA1, utilizing AMG517 and a TRPA1 antagonist HC030031 (ref. 40). Although HC030031 alone had no effect on thermosensory behaviours, Trpv3+/+ and _Trpv3_−/− females administered with both antagonists showed a deficit in thermal preference comparable to _Trpv3_−/− females without antagonists (Fig. 6h,i). These results suggest that both TRPV1 and TRPA1 might act in the same pathway as TRPV3 and nitrites to regulate warm thermosensation. How TRPV1 and TRPA1 are differentially involved in the TRPV3- and nitrite-dependent heat-transduction (noxious versus innocuous) is unknown. Direct TRPV1 activation by noxious heat (threshold is ~42°C) possibly contributes to its predominant role in noxious heat sensation.

Given the strain- and sex-dependent requirement of TRPV3 and nitrites for thermosensory behaviour in vivo, we tested whether RNO(TRPV3) in cultures was dependent on these factors as well. However, we observed comparable RNO(TRPV3) in keratinocytes from both the C57BL/6J and 129S1/SvImJ backgrounds, and from both sexes (Supplementary Fig. S9). This suggests that unknown modifiers of TRPV3-phenotypes are likely to act downstream of NO production.

The NN-free diet potentially has a significant effect on the vascular system, indirectly affecting thermosensation. However, the complete agreement in thermosensory phenotypes between _Trpv3_−/− and nitrite-deprived mice, and the lack of any change in thermosensory behaviours by L-NAME alone argue against the modulation of the vascular system as a major determinant of the change in thermosensory behaviour.

Skin anatomy in adult _Trpv3_−/− and nitrite-deprived mice

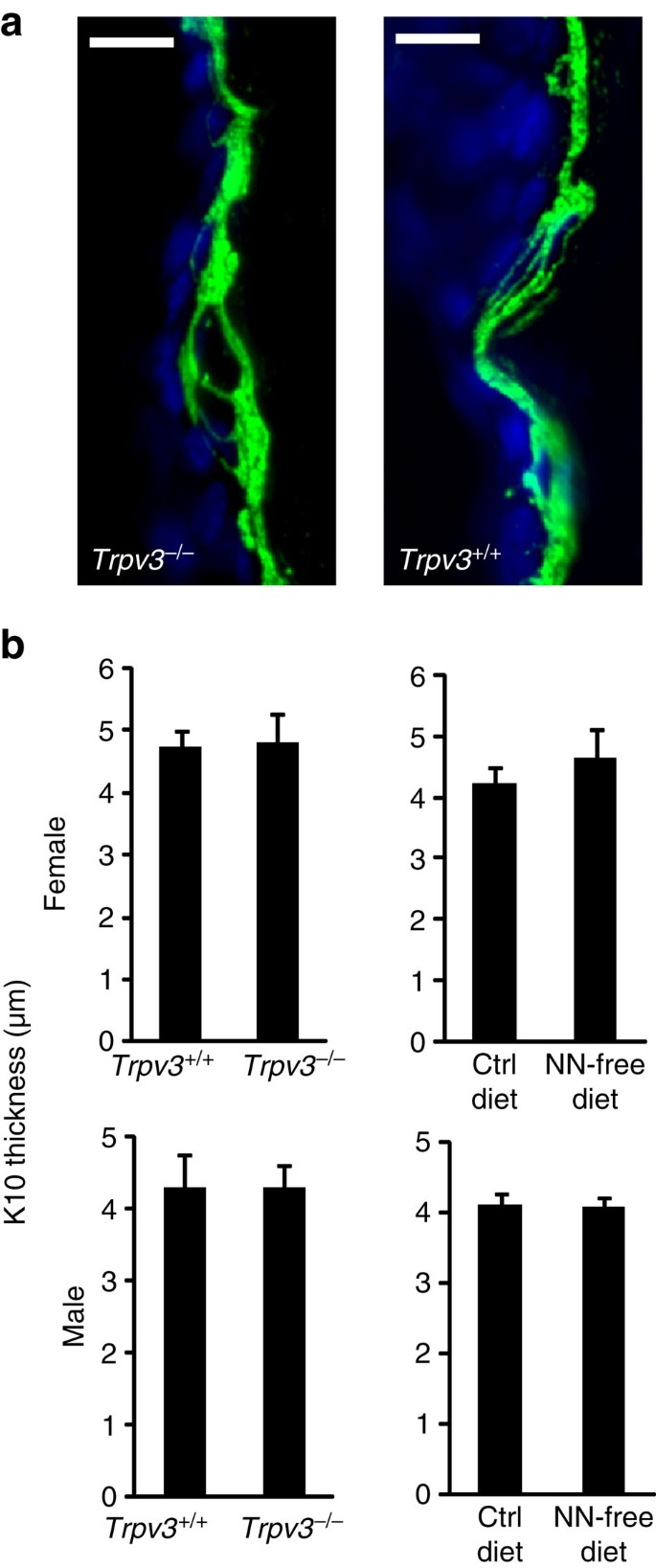

A recent study reported that _Trpv3_−/− mice (both constitutive and conditionally ablated in the skin) show deficits in keratinocyte differentiation and epidermal barrier formation in neonates, and wavy hair in the adult20. In contrast, another study reported normal epidermal barrier formation in the same transgenic _Trpv3_−/− mice in our study41. The apparently conflicting results could be due to unknown differences between the two independently generated _Trpv3_−/− strains including, but not limited to background effects, and/or slightly different assays. In our own previous work, we did observe atypical hair formation in _Trpv3_−/− mice19, but had not explored aspects of keratinocyte differentiation and epidermal barrier formation. Clearly, anatomical deficits in the skin could profoundly affect thermosensory behaviour. However, as the anatomical deficits at the molecular level were described in neonates, we checked whether such deficits persisted in adulthood and measured thickness of keratin-10 (K10) staining, a major phenotype in neonatal (P4) _Trpv3_−/− skin20. Comparable K10-thickness was observed in adult Trpv3+/+ and _Trpv3_−/− mice, or in wildtypecontrol and wildtypeNN-free (Fig. 7). It is possible that the anatomical deficits observed during neonatal life are compensated in adults, or the K10-thickness deficit could be dependent on genetic background. Although subtle hair morphological deficits do exist in Trpv3 alleles19,20, it is unlikely that this causes the strain- and sex-specific behavioural phenotypes to heat. Regardless, our intention is not to argue for or against a direct role of TRPV3 in thermosensation but to point out that behavioural phenotypes of _Trpv3_−/− mice are dependent on nitrites.

Figure 7: Adult _Trpv3_−/− and nitrite-deprived mice reveal normal skin morphology.

(a) Representative immunostaining images for keratin10 (K10, green) with DAPI (blue) in the dorsal skin of adult (~8 week old) Trpv3+/+ (left) and _Trpv3_−/− (right) mice. Scale bars represent 10 μm. (b) The thickness of the K10 layer of dorsal skin obtained from adult (8–12 weeks old) mice of indicated genotype, sex and diet. Numbers of animals are as follows: Female: _n_=6 (Trpv3+/+), 6 (Trpv3 −/−), 4 (Ctrl), and 4 (NN-free), male: _n_=6 (Trpv3+/+), 6 (Trpv3 −/−), 4 (Ctrl), and 4 (NN-free). All the mice are in the 129S1/SvImJ background. Data are represented as mean±s.e.m.

Nitrite contributes to cell migration and wound healing

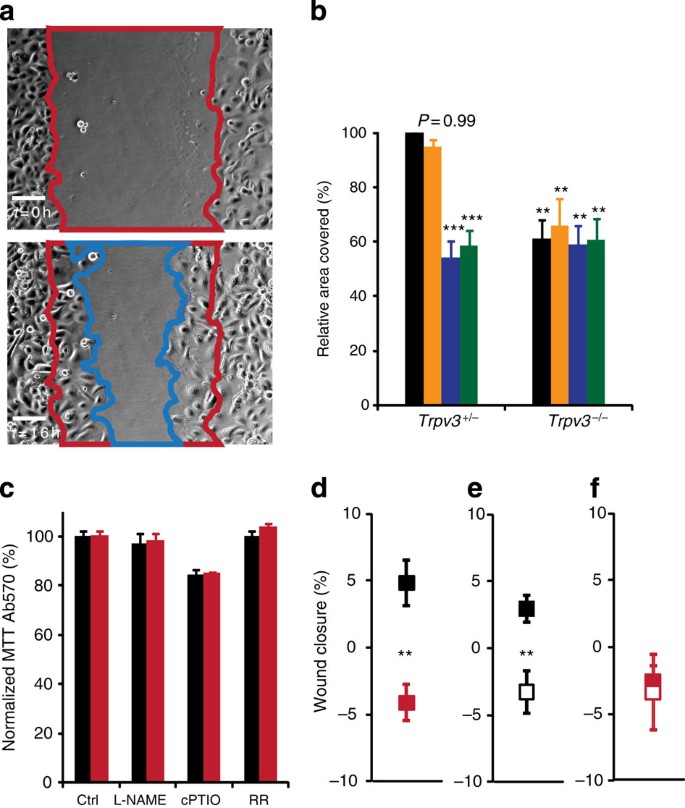

NO is known to have other roles in the skin16, and we explored whether TRPV3 is involved in such NO-mediated processes. We focused on wound healing because the contribution of NO (predominantly NOS-dependent) to this process is reported; however, the role of keratinocytes in NO production is largely unknown42. We first assayed scratch-induced migration of primary keratinocytes (Fig. 8a). Carvacrol, a non-specific TRPV3 agonist, affects corneal cell migration43, suggesting a potential role of TRPV3. Interestingly, keratinocyte migration was compromised by cPTIO and RR, but not by L-NAME (Fig. 8b). _Trpv3_−/− keratinocytes also showed a deficit in this assay; moreover, cPTIO or RR had no further effect over the deficit observed in the _Trpv3_−/− keratinocytes (Fig. 8b). No difference in cell proliferation was observed between Trpv3+/− and _Trpv3_−/− keratinocytes (Fig. 8c). Collectively, TRPV3 and NOS-independent NO contribute to keratinocyte migration.

Figure 8: TRPV3 and nitrite-dependent NO contribute to keratinocyte migration and wound healing.

(a) Representative images of scratched keratinocytes at _t_=0 h (top) and _t_=16 h (bottom). Area not covered by keratinocytes at _t_=0 h is highlighted in red and at _t_=16 h in blue. Scale bars represent 100 μm. (b) Relative area covered (normalized to the control condition in Trpv3+/−) in Trpv3+/− (left) and _Trpv3_−/− (right) keratinocytes during 16 h after the scratch-formation, cultured in keratinocyte media (Control, black), media with a pan-NOS inhibitor L-NAME (500 μM, orange), a NO scavenger cPTIO (100 μM, blue), or a non-specific TRP channel blocker RR (10 μM, green). **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's test (_n_=4 experiments). (c) Normalized cell proliferation (Ab570 of MTT, a cellular respiratory indicator, normalized to the ctrl condition in Trpv3+/−) of Trpv3+/− (black) or _Trpv3_−/− (red) keratinocytes during 16 h in keratinocyte media (Ctrl), media with L-NAME (500 μM), with cPTIO (100 μM), or with RR (10 μM). (d–f) Wound closure (%) 3 days after wound formation in dorsal skin of mice in the 129S1/SvImJ background. Genotypes are represented in colour (black; wild type, red: _Trpv3_−/−) and diets are in fill (control or normal) or clear (NN-free) squares. All the mice were additionally given L-NAME (1 g per l in drinking water). In (d) Trpv3+/+ (black, _n_=19) and _Trpv3_−/− (red, _n_=20) mice on normal diet. In (e), wild-type mice on the control (filled, _n_=21) or NN-free diet (clear, _n_=17). In (f), _Trpv3_−/− mice on the Control (filled, _n_=10) or NN-free diet (clear, _n_=9). Data are represented as mean±s.e.m. **P<0.01, unpaired two-tailed _t_-test.

Keratinocyte migration is one crucial step in epithelialization during wound healing in vivo44. _Trpv3_−/− mice did not show a delay in wound closure in the dorsal skin full-thickness wound model (Supplementary Fig. S10a). This result supports that the skin of _Trpv3_−/− mice is globally normal, and can respond relatively normally to insult (Fig. 7). Because NOS-dependent NO has a prominent role in wound healing42, we postulated that the loss of TRPV3-mediated NO is masked by NOS-dependent pathways. We thus performed a full-thickness wound healing assay in mice administered with L-NAME. Interestingly, L-NAME-treated _Trpv3_−/− mice showed slower wound recovery on day 3, and comparable recovery after day 6, compared with L-NAME-treated Trpv3+/+ littermates (Fig. 8d; Supplementary Fig. S10b). Moreover, wildtypeNN−free showed a similar deficit on day 3 compared with wildtypecontrol (Fig. 8e). Importantly, wound closure in _Trpv3_−/− mice was unaffected by the NN-free diet on day 3 (Fig. 8f). Note that slight expansion of wound sizes during the first few days (negative values of % closure in Fig. 8d–f) is not unusual45. Taken together, these results suggest that TRPV3 and nitrite-dependent NO partly contribute to wound healing in vivo, especially during early stages.

Discussion

Growing evidence suggests that nitrite and nitrate, previously considered as unnecessary end products of NO or undesirable food adducts, should be viewed as important precursors for NO. Nitrite- and NOS-dependent NO-producing pathways often function redundantly. Furthermore, NOS-derived NO is also a source of nitrite. It has been difficult to assign roles for the nitrite-dependent pathway in vivo owing to a lack of specific inhibitors of the nitrite-dependent NO production and partial dependency of the nitrite pathway on NOS-dependent NO. Thus, physiological relevance of nitrite-dependent NO has been demonstrated mostly using exogenously applied nitrites46. Although it is reported that the levels in NO-related signalling molecules are modulated by reduction in endogenous nitrites47, direct evidence that nitrite deprivation attenuates NO production is lacking and its physiological consequences are unknown. Here we show that endogenous levels of nitrites are involved in TRPV3-dependent NO production in keratinocytes. Remarkably, similar thermosensory phenotypes observed in _Trpv3_−/− and nitrite-deprived mice suggest in vivo relevance of this pathway. Although some of the observed phenotypes are relatively subtle, there is very strong agreement that nitrite deprivation causes the same phenotype as _Trpv3_−/− mice. Importantly, nitrite deficiency is ineffective in _Trpv3_−/− mice, emphasizing the requirement of nitrites for TRPV3-signalling.

A subset of DRG neurons innervates peripheral tissues to sense environmental temperature shifts. Many thermoTRPs, including TRPV1, TRPM8 and TRPA1, are expressed in DRGs at high levels and required for thermosensation35. TRPV3 is expressed in keratinocytes and not in DRGs in mice; nevertheless, _Trpv3_−/− mice show thermosensory behavioural deficits18,19. Direct synaptic or otherwise fast signalling between keratinocytes and DRG nerve endings has not been demonstrated. Therefore, it is unclear if the thermosensory behavioural phenotype in _Trpv3_−/− mice is due to deficits in acute thermal transduction. Alternatively, TRPV3 could indirectly affect thermosensory behaviour. For example, TRPV3 could be required for normal keratinocyte development or could affect thermosensory behaviour by modulating vasodilation. Here we link nitrite-dependent NO to the previously described thermosensory behavioural deficit of _Trpv3_−/− mice. This raises the intriguing possibility that NO is a direct signalling molecule between keratinocytes and sensory neurons. NO produced de novo upon heat exposure could acutely excite or modulate sensory neurons. Even low-level NO produced by basal TRPV3 activity (skin temperature being near the TRPV3 threshold) may influence the excitability of heat-sensitive neurons. Potential molecular targets for TRPV3-dependent NO are TRPV1 and TRPA1 ion channels expressed in sensory neurons and activated by NO in vivo38. Indeed, our results suggest TRPV1 and TRPA1 might act in the same pathway as TRPV3 and nitrites in thermosensory behaviours (Figs 5 and 6). It is challenging to determine local concentrations of NO released from keratinocytes in vivo and whether these levels of NO are sufficient to activate or modulate thermoTRPs at nerve endings. TRPV1 and TRPA1 are also potentially expressed in keratinocytes48,49, and might be involved in TRPV3/NO signalling within keratinocytes. The strain- and sex-dependent requirement of nitrites and TRPV3 for thermosensory behaviour argues for a partly redundant role of TRPV3 and nitrite-dependent NO in thermosensation.

As mentioned above, NO signalling could also indirectly affect thermosensory behaviours. In vivo nitrite-depletion, carried out within a few days in adult mice, results in a similar phenotype to _Trpv3_−/− mice, arguing against developmental deficits being responsible for the phenotype. However, as NO is a potent vasodilator, the nitrite-dependent NO could indirectly affect thermosensory behaviour by modulating the vascular system in adult mice. Our results do not answer whether TRPV3 has a direct or indirect role in thermotransduction. Regardless, we linked the phenotype observed in _Trpv3_−/− mice with nitrite levels, implicating a physiological role of the TRPV3-dependent NO in thermosensation.

TRPV3 seems to have diverse roles in the skin. In addition to thermosensation19, TRPV3 has been studied in hair morphology, keratinocyte differentiation and epidermal barrier function20. Indeed, previous studies proposed that prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), ATP, interleukin-1α (IL-1α), and transforming growth factor α (TGFα) potentially act downstream of TRPV3 (refs 20,50,51,52). However, evidence for a direct link between those molecules and endogenous TRPV3 function in vivo is lacking. For example, TRPV3-mediated PGE2 production was observed in TRPV3-overexpressing but not in wild-type keratinocytes50. Consequently, TRPV3-overexpressing transgenic but not wild-type mice showed PGE2-dependent heat sensitivity50. Meanwhile, the role of ATP in TRPV3-dependent signalling in vivo has not been demonstrated51. TRPV3-dependent TGFα secretion is implicated in normal hair morphology and skin anatomy, but a direct in vivo link has not been demonstrated20. The role of TRPV3-dependent IL-1α release remains unknown52. Regardless, it is likely that TRPV3 activation in keratinocytes causes secretion of a cocktail of signalling factors that act in concert on keratinocytes themselves, other neighbouring cell types, and nerve endings to affect thermosensation as well as other biological processes.

We investigated whether the TRPV3–nitrite pathway is involved in wound healing, a process involving NO in the skin42, and observed effects only when the NOS pathway is blocked (Fig. 8). This suggests that, unlike thermosensory behaviours, the NOS-dependent NO compensates for the TRPV3–nitrite pathway in wound healing. iNOS, a transcriptionally regulated subtype, accounts for most of the NO production during wound healing42. The TRPV3–nitrite–NO pathway might have a more prominent role before transcriptional upregulation of iNOS. Indeed, both _Trpv3_−/− and nitrite-deprived mice showed a delayed wound closure only at early stages. We also show that in vitro, TRPV3-mediated and NOS-independent NO has a role in keratinocyte migration. Although NO has been shown to indirectly modulate endothelial cell migration during wound healing42, the role of NO in keratinocyte migration has not been reported previously. Whether keratinocyte migration contributes to the wound healing process has not been definitively established. What TRPV3-activating signals are involved in wound healing and keratinocyte migration? Skin temperature is near the threshold of TRPV3 activation under physiological conditions, and basal TRPV3 activity might contribute to keratinocyte migration. Inflammation during the wound healing process causes an increase in local temperature53 and secretion of inflammatory mediators54 that potentially modulate TRPV3 activity directly or indirectly via activating G-protein-coupled-receptors and receptor tyrosine kinases within keratinocytes20,52. Finally, tissue acidosis during inflammation could also potentially enhance TRPV3-mediated NO production.

Our study suggests wider functions of nitrite-dependent NO, previously described mainly in extracellular milieu or under hypoxic/acidic conditions6. In the skin, biological processes involving NO include inflammation, melanogenesis, hair development and heat-induced vasodilation16. Although NOS-dependent NO has been demonstrated to contribute to these processes16, nitrite-dependent NO could also participate, especially in severely hypoxic areas of the skin such as hair follicles and sebaceous glands26. Nitrite-dependent NO could also have a role downstream of other receptors. Indeed, TRPV1 and TRPV4 could function in a similar way to TRPV3. TRPV4 is implicated in warm thermosensation55. TRPV1 is involved in NO release in urothelial cells via an unknown mechanism56. A more recent study reported a role of TRPV1 in arterial endothelial cells in regulating NO production, although the NOS-dependent pathway is implicated57. TRPV1 is also involved in synaptic plasticity through unknown mechanisms and this regulation may employ NO58,59,60. Finally, it is likely that ion channel families and receptors beyond TRPs can also regulate NOS-independent NO release.

Methods

Primary keratinocyte culture

Primary culture of newborn mouse keratinocytes (P0-P2) was performed according to our previous protocol19. Briefly, dorsal skin was removed and placed in 2.5% dispase solution for 6–18 h at 4 °C. Epidermal layer of the skin was peeled off and gently shaken in a conical tube containing keratinocyte media (CnT-02 CELLnTEC). Cells were fully dissociated with a cell scraper, and centrifuged (5 min, 1,000 r.p.m., RT) with BSA column. The pellet was resuspended and plated on collagen IV (Trevigen)-coated glass coverslips and cultured for 2–3 days in keratinocyte media at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

Electroporation was done using Human Keratinocyte Nucleofector Kit (Lonza) according to the manufacturer's instruction (high efficiency neonatal primary keratinocyte program, T-018).

For nitrite-deprived keratinocyte culture (Fig. 3b), the diet of pregnant females was switched to the NN-free diet (see details in Nitrite deprivation below) at E15.5 and P1 pups from the females were used for primary keratinocyte culture. Keratinocytes were cultured in media containing L-NAME (200 μM) to block potential nitrite formation from NOS-dependent NO production. Nitrite levels in the media for keratinocytes (CnT-02, CELLnTEC) were below the detection limit (~2 μM) using Measure iT high-sensitivity nitrite assay kit (Invitrogen). Control keratinocytes were prepared from P1 pups born by females fed with standard feed and L-NAME (1 g per l) in the drinking water after E15.5 and cultured in media containing L-NAME (200 μM).

For keratinocyte migration and proliferation experiments (Fig. 8), keratinocytes were cultured in 6-well plates for 2–3 days. The grown keratinocytes were then washed, trypsinized (0.25% trypsin) and centrifuged (5 min, 1,000 r.p.m., RT) through a BSA column. The pellet was resuspended and plated in collagen IV (Trevigen)-coated 24-well plates (for migration assay, at least 5×105 cells per well) or 96-well plates (for proliferation assay, 1×105 cells per well). For cell migration assays, keratinocytes were grown at 37 °C with 5% CO2 to confluency (typically takes 1–2 days), and further grown for one more day to ensure full-confluent keratinocyte layers prior to the experiments. To obtain a large amount of keratinocytes in each condition, Trpv3+/− and _Trpv3_−/− keratinocytes (from breeders of Trpv3+/− and _Trpv3_−/− mice) were compared.

NO-imaging

Cells were loaded with DAF-FM deacetate (Invitrogen, 10 μM) for 20 min in the imaging buffer solution. Images of DAF-FM loaded cells with the excitation/emission wavelengths at ~488/520 nm were captured with an LCD camera using MetaFluor (Life Science Imaging). The fluorescence intensity of individual cells in each experiment was normalized to the baseline (F/_F_0, %). At least 100 keratinocytes were averaged per experiment. The trace (F/_F_0 plotted as a function of time) during a stimulus was fit to a line using Igor Pro (WaveMetrics), and the slope (Δ(F/F_0)/Δ_t) (%/s) of the line is shown in bar graph as 'NO production rate'.

pH-imaging

Myristoylated pHluorin (mpHluorin) was constructed by PCR using 5′ primer containing kozak and myristoylation signal sequences (5′-CGCAAGCTTCAGGATGGGCAACTTGAAGAGTGTGGGCCAGATGAGTAAAGGAGAAG-3′) and 3′ primer (5′-CGACTCGAGCTATTTGTATAGTTCATCCATGCCATG-3′). Normal pHluorin was constructed using 5′ primer (5′-CGCAAGCTTGCCATGAGTAAAGGAGAAG-3′) and the same 3′ primer for mpHluorin. Ecliptic pHluorin containing plasmid was kindly provided by Dr Anton Maximov (TSRI). PCR product was cloned into pcDNA5/FRT (Invitrogen) using HindIII and XhoI followed by sequence verification.

Images of cells expressing mpHluorin with the excitation/emission wavelengths at ~488/520 nm were captured with an LCD camera using MetaFluor. The fluorescence intensity of individual cells in each experiment was normalized to the intensity just prior to a stimulus (F/_F_p, %). At least 20 transfected cells were averaged per experiment. The traces (F/_F_p plotted as a function of time) prior to and during a stimulus were fit to lines using Igor Pro (WaveMetrics). The slopes of the fit lines represent the rate of photobleaching and summed rates of intracellular pH change and photobleaching, respectively. The difference between the two slopes ((the slope of 'during')-(the slope of 'prior to')) represents the rate of intracellular pH change and is shown in data as 'Normalized slope' (Δ(F/F_p)/Δ_t) (%/s).

Keratinocyte migration assay

Fully confluent primary keratinocytes on a 24-well plate were scratched using pipette tips, washed, and changed to pre-warmed keratinocyte media (control), supplemented with 500 μM L-NAME (L-NAME), 100 μM cPTIO (cPTIO), or 10 μM RR. The plate was then transferred to a microscope with a temperature-controlled chamber set at 37 °C. Brightfield images of at least 15 regions per each condition were taken every hour for 16 h. Areas not covered by keratinocytes were measured at 0 and 16 h using MetaMorph (Life Science Imaging) and the area covered by keratinocytes within 0–16 h was calculated and averaged for each condition (Fig. 8a). All the conditions per experiment were included on the same 24-well plate. To enable comparison between multiple experiments, the areas covered were normalized to the Trpv3+/− control condition.

Cell proliferation assay

Cell proliferation assay was performed on primary keratinocytes on 96-well plate (105 cells per well) using MTT cell proliferation assay according to manufacturer's instructions. Primary keratinocytes were first cultured at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 4 h after BSA column (this process let keratinocytes attach to the plate), then switched to keratinocyte media (control), or media supplemented with 500 μM L-NAME, 100 μM cPTIO, or 10 μM RR and cultured for 16 h before addition of MTT reagent.

Mice

All experiments involving animals were conducted with the approval of The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) Animal Research Committee. All aspects of the programme for procurement, conditioning/quarantine, housing, management, veterinary care and disposal of carcasses follow the guidelines set down in the NIH Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Mice are housed in SPF facility with 12/12 dark-light cycle. All behavioural experiments were conducted on littermates 6- to 12-week-old during daytime. Unless otherwise noted, both males and females were tested and combined when they behave similarly. Animals were acclimated for 20 min in the testing environment prior to experiments unless otherwise stated. Experimenters were blind to genotype and treatment.

Thermal choice assay

Six mice were individually tracked for an hour in arenas on temperature controlled aluminum plates at the same time. The temperature of the aluminum floor plates is well controlled and stably maintained by Peltier devices (constructed by the Genomic Institute of the Novartis Research Foundation). Each arena is separated by opaque plexiglass walls and transparent ceilings. Video images captured by CCD camera placed ~2 meters above the plates were analysed with Ethovision 3.1 (Noldus Information Technology). Each arena is virtually divided into two zones of equal size with a distinct and stable temperature, and the time spent on each zone in 30 min intervals was recorded. The arena for the thermal choice assay is 39.5 cm (L)×7.9 cm (W)×10 cm (H) with stable set temperatures. The preference index (I) for temperature choice assay is defined as _I_=(_t_H−_t_L)/(_t_H+_t_L), where _t_H and _t_L are the time spent on the zones of higher and lower temperature respectively.

Nitrite deprivation

Unless otherwise stated, all mice were on normal diet (Teklad LM-485 Mouse/Rat sterilizable feed (Harlan Laboratories) and acidified (~pH 5) tap water). Mice were on the NN-free or the control diet at least five days prior to and throughout thermal behavioural and wound healing assays.

For thermal behavioural assays, mice were fed with nitrite/nitrate/L-arginine-free feed (Amino acid rodent without L-arginine, Zeigler Brothers Inc.) and de-ionized drinking water containing L-NAME (1 g per l) (NN-free diet). Control mice were given the same feed but supplemented with NaNO2 (20 mM) and no L-NAME in the drinking water (control diet). The drinking water was freshly prepared and changed every 2 days. For wound healing assays in which L-NAME has a significant effect, control mice were also given L-NAME (1 g per l) in the drinking water in addition to the control diet.

Nitrite concentrations were 30.6±3.0 nmol per g in the standard feed and below the detection limit (~4 nmol per g) in nitrite/nitrate/L-arginine-free feed, respectively. No detectable nitrite was found in either drinking or de-ionized water. Nitrite measurement was performed using Measure iT high-sensitivity nitrite assay kit (Invitrogen).

Wound healing model

Mice were anaesthetized with pentobarbital (40 mg per kg i.p.) and placed on a heating blanket. Dorsal hair was shaved and further removed by hair-removing cream. Two full-thickness wounds were created in the upper dorsal skin using 4 mm wide dermal biopsy punch (Sklar Instruments). Wounded areas were patched with Tegaderm (3 M) for six days and wound sizes were measured with a scale loupe (Peak Optics, #1975) every 3 days. Percent closure of each wound was calculated and averaged for individual mice.

Definition of percent closure n days after wound formation: C(n)=100×[1−(d_L_n_×_d_S_n)/(_d_L0×_d_S0)], where d_L_n and d_S_n are long and short diameters of oval-shaped wound n days after wound formation.

Data analysis

Data are presented as the mean±the standard error of the mean for all the figures. _P_-values are based on unpaired two-tailed _t_-test for comparing two samples, and on one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's test (Figs 3c and 8b). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

See Supplementary Methods for further details of transient transfection, ratiometric calcium-imaging, FLIPR, cGMP measurement, solutions used, Trpv3 −/− mice, NOS-deficient mice, Trpv4 −/− mice, hot plate and von Frey assays, administration of AMG517 and HC030031, immunohistochemistry and chemicals used.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Miyamoto, T. et al. TRPV3 regulates nitric oxide synthase-independent nitric oxide synthesis in the skin. Nat. Commun. 2:369 doi: 10.1038/ncomms1371 (2011).

References

- MacMicking, J., Xie, Q. W. & Nathan, C. Nitric oxide and macrophage function. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 15, 323–350 (1997).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Bredt, D. S. & Snyder, S. H. Nitric oxide: a physiologic messenger molecule. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 63, 175–195 (1994).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Ignarro, L. J. Endothelium-derived nitric oxide: actions and properties. FASEB J. 3, 31–36 (1989).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Chvanov, M., Gerasimenko, O. V., Petersen, O. H. & Tepikin, A. V. Calcium-dependent release of NO from intracellular S-nitrosothiols. EMBO J. 25, 3024–3032 (2006).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Furchgott, R. F., Ehrreich, S. J. & Greenblatt, E. The photoactivated relaxation of smooth muscle of rabbit aorta. J. Gen. Physiol. 44, 499–519 (1961).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Lundberg, J. O., Weitzberg, E. & Gladwin, M. T. The nitrate-nitrite-nitric oxide pathway in physiology and therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 7, 156–167 (2008).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Suschek, C. V., Schewe, T., Sies, H. & Kroncke, K. D. Nitrite, a naturally occurring precursor of nitric oxide that acts like a 'prodrug'. Biol. Chem. 387, 499–506 (2006).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Cosby, K. et al. Nitrite reduction to nitric oxide by deoxyhemoglobin vasodilates the human circulation. Nat. Med. 9, 1498–1505 (2003).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Zweier, J. L., Wang, P., Samouilov, A. & Kuppusamy, P. Enzyme-independent formation of nitric oxide in biological tissues. Nat. Med. 1, 804–809 (1995).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Zhang, Z. et al. Human xanthine oxidase converts nitrite ions into nitric oxide (NO). Biochem. Soc. Trans. 25, 524S (1997).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Allen, B. W., Stamler, J. S. & Piantadosi, C. A. Hemoglobin, nitric oxide and molecular mechanisms of hypoxic vasodilation. Trends. Mol. Med. 15, 452–460 (2009).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Benjamin, N. et al. Stomach NO synthesis. Nature 368, 502 (1994).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Lundberg, J. O., Weitzberg, E., Lundberg, J. M. & Alving, K. Intragastric nitric oxide production in humans: measurements in expelled air. Gut 35, 1543–1546 (1994).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Weller, R. et al. Nitric oxide is generated on the skin surface by reduction of sweat nitrate. J. Invest. Dermatol. 107, 327–331 (1996).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Paunel, A. N. et al. Enzyme-independent nitric oxide formation during UVA challenge of human skin: characterization, molecular sources, and mechanisms. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 38, 606–615 (2005).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Cals-Grierson, M. M. & Ormerod, A. D. Nitric oxide function in the skin. Nitric Oxide 10, 179–193 (2004).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Kellogg, D. L. Jr., Crandall, C. G., Liu, Y., Charkoudian, N. & Johnson, J. M. Nitric oxide and cutaneous active vasodilation during heat stress in humans. J. Appl. Physiol. 85, 824–829 (1998).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Peier, A. M. et al. A heat-sensitive TRP channel expressed in keratinocytes. Science 296, 2046–2049 (2002).

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Moqrich, A. et al. Impaired thermosensation in mice lacking TRPV3, a heat and camphor sensor in the skin. Science 307, 1468–1472 (2005).

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Cheng, X. et al. TRP channel regulates EGFR signaling in hair morphogenesis and skin barrier formation. Cell 141, 331–343 (2010).

Article CAS Google Scholar - McQuade, L. E. & Lippard, S. J. Fluorescent probes to investigate nitric oxide and other reactive nitrogen species in biology (truncated form: fluorescent probes of reactive nitrogen species). Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 14, 43–49 (2010).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Chung, M. K., Lee, H., Mizuno, A., Suzuki, M. & Caterina, M. J. 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate activates and sensitizes the heat-gated ion channel TRPV3. J. Neurosci. 24, 5177–5182 (2004).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Hu, H. Z. et al. 2-aminoethoxydiphenyl borate is a common activator of TRPV1, TRPV2, and TRPV3. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 35741–35748 (2004).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Mathews, W. R. & Kerr, S. W. Biological activity of S-nitrosothiols: the role of nitric oxide. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 267, 1529–1537 (1993).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Son, H. et al. Long-term potentiation is reduced in mice that are doubly mutant in endothelial and neuronal nitric oxide synthase. Cell 87, 1015–1023 (1996).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Evans, S. M., Schrlau, A. E., Chalian, A. A., Zhang, P. & Koch, C. J. Oxygen levels in normal and previously irradiated human skin as assessed by EF5 binding. J. Invest. Dermatol. 126, 2596–2606 (2006).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Granger, D. L., Hibbs, J. B. Jr. & Broadnax, L. M. Urinary nitrate excretion in relation to murine macrophage activation. Influence of dietary L-arginine and oral NG-monomethyl-L-arginine. J. Immunol. 146, 1294–1302 (1991).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Li, H., Cui, H., Kundu, T. K., Alzawahra, W. & Zweier, J. L. Nitric oxide production from nitrite occurs primarily in tissues not in the blood: critical role of xanthine oxidase and aldehyde oxidase. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 17855–17863 (2008).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Roos, A. & Boron, W. F. Intracellular pH. Physiol. Rev. 61, 296–434 (1981).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Chung, M. K., Lee, H., Mizuno, A., Suzuki, M. & Caterina, M. J. TRPV3 and TRPV4 mediate warmth-evoked currents in primary mouse keratinocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 21569–21575 (2004).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Miesenbock, G., De Angelis, D. A. & Rothman, J. E. Visualizing secretion and synaptic transmission with pH-sensitive green fluorescent proteins. Nature 394, 192–195 (1998).

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Hellwig, N. et al. TRPV1 acts as proton channel to induce acidification in nociceptive neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 34553–34561 (2004).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Chung, M. K., Guler, A. D. & Caterina, M. J. Biphasic currents evoked by chemical or thermal activation of the heat-gated ion channel, TRPV3. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 15928–15941 (2005).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Grandl, J. et al. Pore region of TRPV3 ion channel is specifically required for heat activation. Nat. Neurosci. 11, 1007–1013 (2008).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Dhaka, A., Viswanath, V. & Patapoutian, A. Trp ion channels and temperature sensation. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 29, 135–161 (2006).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Caterina, M. J. et al. Impaired nociception and pain sensation in mice lacking the capsaicin receptor. Science 288, 306–313 (2000).

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Gavva, N. R. et al. Repeated administration of vanilloid receptor TRPV1 antagonists attenuates hyperthermia elicited by TRPV1 blockade. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 323, 128–137 (2007).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Miyamoto, T., Dubin, A. E., Petrus, M. J. & Patapoutian, A. TRPV1 and TRPA1 mediate peripheral nitric oxide-induced nociception in mice. PLoS One 4, e7596 (2009).

Article ADS Google Scholar - Story, G. M. et al. ANKTM1, a TRP-like channel expressed in nociceptive neurons, is activated by cold temperatures. Cell 112, 819–829 (2003).

Article CAS Google Scholar - McNamara, C. R. et al. TRPA1 mediates formalin-induced pain. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 13525–13530 (2007).

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Sokabe, T., Fukumi-Tominaga, T., Yonemura, S., Mizuno, A. & Tominaga, M. The TRPV4 channel contributes to intercellular junction formation in keratinocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 18749–18758 (2010).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Rizk, M., Witte, M. B. & Barbul, A. Nitric oxide and wound healing. World J. Surg. 28, 301–306 (2004).

Article Google Scholar - Yamada, T. et al. Functional expression of transient receptor potential vanilloid 3 (TRPV3) in corneal epithelial cells: involvement in thermosensation and wound healing. Exp. Eye. Res. 90, 121–129 (2010).

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar - Kirfel, G. & Herzog, V. Migration of epidermal keratinocytes: mechanisms, regulation, and biological significance. Protoplasma 223, 67–78 (2004).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Tkalcevic, V. I., Cuzic, S., Parnham, M. J., Pasalic, I. & Brajsa, K. Differential evaluation of excisional non-occluded wound healing in db/db mice. Toxicol. Pathol. 37, 183–192 (2009).

Article Google Scholar - Lundberg, J. O. & Weitzberg, E. NO-synthase independent NO generation in mammals. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 396, 39–45 (2010).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Bryan, N. S. et al. Nitrite is a signaling molecule and regulator of gene expression in mammalian tissues. Nat. Chem. Biol. 1, 290–297 (2005).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Denda, M. et al. Immunoreactivity of VR1 on epidermal keratinocyte of human skin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 285, 1250–1252 (2001).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Kwan, K. Y., Glazer, J. M., Corey, D. P., Rice, F. L. & Stucky, C. L. TRPA1 modulates mechanotransduction in cutaneous sensory neurons. J. Neurosci. 29, 4808–4819 (2009).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Huang, S. M. et al. Overexpressed transient receptor potential vanilloid 3 ion channels in skin keratinocytes modulate pain sensitivity via prostaglandin E2. J. Neurosci. 28, 13727–13737 (2008).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Mandadi, S. et al. TRPV3 in keratinocytes transmits temperature information to sensory neurons via ATP. Pflugers. Arch. 458, 1093–1102 (2009).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Xu, H., Delling, M., Jun, J. C. & Clapham, D. E. Oregano, thyme and clove-derived flavors and skin sensitizers activate specific TRP channels. Nat. Neurosci. 9, 628–635 (2006).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Janeway, C. Immunobiology: The Immune System in Health and Disease, 6th edn (Garland Science, 2005).

- Basbaum, A. I., Bautista, D. M., Scherrer, G. & Julius, D. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of pain. Cell 139, 267–284 (2009).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Lee, H., Iida, T., Mizuno, A., Suzuki, M. & Caterina, M. J. Altered thermal selection behavior in mice lacking transient receptor potential vanilloid 4. J. Neurosci. 25, 1304–1310 (2005).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Birder, L. A. et al. Altered urinary bladder function in mice lacking the vanilloid receptor TRPV1. Nat. Neurosci. 5, 856–860 (2002).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Yang, D. et al. Activation of TRPV1 by dietary capsaicin improves endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation and prevents hypertension. Cell Metab. 12, 130–141 (2010).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Marsch, R. et al. Reduced anxiety, conditioned fear, and hippocampal long-term potentiation in transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1 receptor-deficient mice. J. Neurosci. 27, 832–839 (2007).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Gibson, H. E., Edwards, J. G., Page, R. S., Van Hook, M. J., & Kauer, J. A. TRPV1 channels mediate long-term depression at synapses on hippocampal interneurons. Neuron 57, 746–759 (2008).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Calabrese, V. et al. Nitric oxide in the central nervous system: neuroprotection versus neurotoxicity. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 8, 766–775 (2007).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

We thank K. Spencer (TSRI) for valuable help in microscopy/image analysis, A. Maximov (TSRI) for pHluorin containing plasmid, R. Tsien (University of California, San Diego) for mCherry construct, C. Schmedt and V. Piamonte (GNF) for providing a protocol for the dorsal wound healing mouse model, Drs M. Suzuki and A. Mizuno for _Trpv4_−/− mice, and N. Hong for comments on the manuscript. T.M. is supported by Skaggs Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- Department of Cell Biology, Dorris Neuroscience Center, The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, 92037, California, USA

Takashi Miyamoto, Adrienne E. Dubin & Ardem Patapoutian - Genomics Institute of the Novartis Research Foundation, San Diego, 92121, California, USA

Matt J. Petrus & Ardem Patapoutian

Authors

- Takashi Miyamoto

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Matt J. Petrus

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Adrienne E. Dubin

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - Ardem Patapoutian

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

T.M. and A.P. designed experiments. T.M. performed bulk of experiments. M.J.P. contributed to behavioural experiments. A.E.D. contributed to pH-measurement experiments. T.M., A.E.D. and A.P. wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Correspondence toArdem Patapoutian.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Miyamoto, T., Petrus, M., Dubin, A. et al. TRPV3 regulates nitric oxide synthase-independent nitric oxide synthesis in the skin.Nat Commun 2, 369 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1371

- Received: 31 March 2011

- Accepted: 27 May 2011

- Published: 28 June 2011

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms1371