Association of composite dietary antioxidant index with depression and all-cause mortality in middle-aged and elderly population (original) (raw)

Introduction

Depression is an affective disorder characterized by severe and persistent symptoms of mood, cognition, and physical state, such as low self-esteem, anhedonia, lack of energy, despondency, irritability, and fatigue[1](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR1 "Smith, K. Mental health: A world of depression. Nature 515, 181. https://doi.org/10.1038/515180a

(2014)."),[2](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR2 "Monroe, S. M. & Harkness, K. L. Major depression and its recurrences: Life course matters. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 18, 329–357.

https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-072220-021440

(2022)."). Severe depression can even lead to suicide and is one of the most common mental illnesses, significantly affecting cognitive functioning, quality of life, and overall health[3](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR3 "Douglas, K. M., Porter, R. J., Knight, R. G. & Maruff, P. Neuropsychological changes and treatment response in severe depression. Br. J. Psychiatry 198, 115–122.

https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.110.080713

(2011)."). Moreover, depression has become a serious public health issue, increasing social and economic burdens and the risk of death[4](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR4 "McCarron, R. M., Shapiro, B., Rawles, J. & Luo, J. Depression. Ann. Intern. Med. 174, 65–80.

https://doi.org/10.7326/AITC202105180

(2021)."). Epidemiological studies indicate that more than 350 million people worldwide suffer from depression[5](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR5 "Kessler, R. C. et al. Anxious and non-anxious major depressive disorder in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 24, 210–226.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796015000189

(2015)."). The World Health Organization (WHO) predicts that by 2030, major depression will become the leading cause of global disease burden[6](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR6 "O’Leary, K. Global increase in depression and anxiety. Nat. Med.

https://doi.org/10.1038/d41591-021-00064-y

(2021)."). Research has found that the onset and severity of depression are not only influenced by genetic factors but also by environmental and dietary factors[7](#ref-CR7 "Kosciuszko, M., Steptoe, A. & Ajnakina, O. Genetic propensity, socioeconomic status, and trajectories of depression over a course of 14 years in older adults. Transl. Psychiatry 13, 68.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-023-02367-9

(2023)."),[8](#ref-CR8 "Leone, M. et al. Genetic and environmental contribution to the co-occurrence of endocrine-metabolic disorders and depression: A Nationwide Swedish Study of Siblings. Am. J. Psychiatry 179, 824–832.

https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.21090954

(2022)."),[9](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR9 "Swainson, J. et al. Diet and depression: A systematic review of whole dietary interventions as treatment in patients with depression. J. Affect. Disord. 327, 270–278.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.01.094

(2023).").Dietary interventions for chronic diseases have become increasingly recognized. The Mediterranean diet, based on a high intake of vegetables and fruit, fish, grains, legumes, and olive oil, has been shown to offer protection against heart disease, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. It also prevents cerebrovascular damage, thereby reducing the risk of stroke, memory loss, and all-cause mortality[10](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR10 "Bisaglia, M. Mediterranean diet and Parkinson’s disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24010042

(2022)."),[11](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR11 "Ballarini, T. et al. Mediterranean diet, alzheimer disease biomarkers and brain atrophy in old age. Neurology 96, e2920-2932.

https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000012067

(2021)."). The dietary approach to stop hypertension (DASH) diet promotes a diet high in potassium, low in sodium, magnesium, and calcium, and high in dietary fiber and unsaturated fatty acids, which is well proven to be effective in lowering blood pressure[12](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR12 "Goyal, P. et al. The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet pattern and incident heart failure. J. Card. Fail. 27, 512–521.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cardfail.2021.01.011

(2021)."). The flexible vegetarian diet that emphasizes increased vegetable consumption and reduced meat intake, is very effective in weight loss[13](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR13 "Sofi, F. et al. Low-calorie vegetarian versus mediterranean diets for reducing body weight and improving cardiovascular risk profile: CARDIVEG Study (Cardiovascular Prevention With Vegetarian Diet). Circulation 137, 1103–1113.

https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030088

(2018)."). Anti-inflammatory diets focusing on fish, fruits, and vegetables have also been demonstrated a suppressive effect on the risk of Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, atherosclerosis, heart disease, and muscle wasting[14](#ref-CR14 "Chen, L. et al. Different oral and gut microbial profiles in those with Alzheimer’s disease consuming anti-inflammatory diets. Front. Nutr. 9, 974694.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.974694

(2022)."),[15](#ref-CR15 "McNamara, S. L. et al. Anti-inflammatory therapy enables robot-actuated regeneration of aged muscle. Sci. Robot. 8, eadd9369.

https://doi.org/10.1126/scirobotics.add9369

(2023)."),[16](#ref-CR16 "Kaluza, J., Levitan, E. B., Michaelsson, K. & Wolk, A. Anti-inflammatory diet and risk of heart failure: Two prospective cohort studies. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 22, 676–682.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.1746

(2020)."),[17](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR17 "Shah, B. et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of a vegan diet versus the American Heart Association-recommended diet in coronary artery disease trial. J. Am. Heart. Assoc. 7, e011367.

https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.118.011367

(2018)."). Furthermore, a meta-analysis showed that the addition of the antioxidant vitamin E to the treatment of depression and anxiety might be beneficial[18](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR18 "Lee, A. et al. Vitamin E, alpha-tocopherol, and its effects on depression and anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients 14, 656.

https://doi.org/10.3390/nu1403065

(2022).").The composite dietary antioxidant index (CDAI) is a measurement of individual antioxidant profiles derived from dietary combinations developed to assess and reflect the overall impact of dietary antioxidants on health[19](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR19 "Yu, Y. C. et al. Composite dietary antioxidant index and the risk of colorectal cancer: Findings from the Singapore Chinese Health Study. Int. J. Cancer 150, 1599–1608. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.33925

(2022)."). Initially, research on the CDAI predominantly addressed cancer; however, its relevance has increasingly expanded into psychiatry in recent years[20](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR20 "Vahid, F., Rahmani, D. & Davoodi, S. H. Validation of Dietary Antioxidant Index (DAI) and investigating the relationship between DAI and the odds of gastric cancer. Nutr. Metab. 17, 102.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12986-020-00529-w

(2020)."),[21](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR21 "Zhao, L. et al. Non-linear association between composite dietary antioxidant index and depression. Front. Public Health 10, 988727.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.988727

(2022)."). An Iranian study highlighted that the dietary antioxidant index was associated with a reduced incidence of depression and anxiety in young women. However, the association of CDAI with depression and all-cause mortality in the middle-aged and elderly, a population with a high prevalence of depression and death, has still not been explored. To address this gap, we extracted data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) for six cycles (2007–2018) to investigate these associations.Methods

Study population

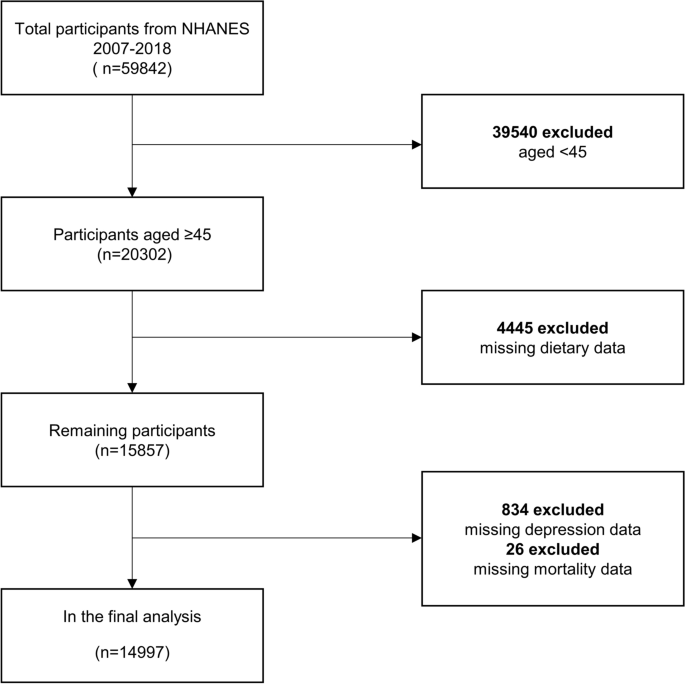

NHANES, initiated in 1999 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, is a biennial observational survey that assesses the health and nutritional status of the non-institutionalized US population. It combines interviews with physical examinations to gather comprehensive data on demographics, socioeconomics, dietary habits, and health status. Medical assessments, physiological measurements, and laboratory examinations were conducted by highly qualified medical specialists. The NHANES protocol was approved by the National Center for Health Statistics of the Institutional Review Board, and all participants' informed consent was obtained. For this study, data from six cycles were analyzed, encompassing 14,997 individuals after excluding those who were: (1) younger than 45 years (n = 39,540); (2) missing CDAI data (n = 445); (3) missing depression data (n = 834), missing mortality data(n = 26) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1

Flow chart of sample selection.

Assessment of composite dietary antioxidant index

Dietary assessments were based on two 24-h recall interviews conducted by trained dietary interviewers. The first recall was carried out in person using a standardized protocol during the medical examination at the mobile screening center. The second recall was conducted by telephone within 3 to 10 days of the first recall. Nutritional intakes were calculated based on food intake through the use of a revised nutritional database which translates each individual's food intake into nutrients. We calculated CDAI for all subjects from six dietary minerals and vitamins (Mn, Se, Zn, Vitamins A, C, and E) using Wright's recommended measures[22](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR22 "Wright, M. E. et al. Development of a comprehensive dietary antioxidant index and application to lung cancer risk in a cohort of male smokers. Am. J. Epidemiol. 160, 68–76. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwh173

(2004)."). The detailed calculation formula was as follows:CDAI = \mathop \sum \limits_{{{\text{i}} = 1}}^{{{\text{n}} = 6}} \frac{{{\text{Individual Intake}} - {\text{Mean}}}}{{{\text{SD}}}}$$

Assessment of depression and all-cause mortality

The diagnosis of depression was determined using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) scores, with each item being scored on a scale of 0–3 and a total score range of 0–27. A PHQ-9 score of 10 or above is considered indicative of depressive symptoms, offering a good balance between sensitivity and specificity for depression diagnosis. This determination has been widely used in cross-sectional studies of depression[23](#ref-CR23 "Smagula, S. F. et al. Association of 24-hour activity pattern phenotypes with depression symptoms and cognitive performance in aging. JAMA Psychiatry 79, 1023–1031. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.2573

(2022)."),[24](#ref-CR24 "Patel, P. O., Patel, M. R. & Baptist, A. P. Depression and asthma outcomes in older adults: Results from the national health and nutrition examination survey. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 5, 1691–1697.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2017.03.034

(2017)."),[25](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR25 "Han, Y. Y., Forno, E., Marsland, A. L., Miller, G. E. & Celedon, J. C. Depression, asthma, and bronchodilator response in a nationwide study of US adults. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 4, 68–73.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2015.10.004

(2016)."). We extracted mortality data from the National Death Index (NDI) death certificate records, from which the information on mortality status and follow-up time (in months) was collected from the date of participation to the end of the follow-up period (December 31, 2019).Covariates

Referring to previous literature, we included covariates potentially influencing CDAI, depression, and all-cause mortality. Demographic characteristics such as age, gender, race, education level, marital status, and income-to-poverty ratio were included. Health-related behaviors included smoking status, vigorous recreational activity, drinking status, and medical co-morbidity variables (CVD, stroke, hypertension, diabetes, and cancer) were also collected. Biochemical and physical examinations consisted of C-reactive protein (CRP), body mass index (BMI), and waist. Additionally, the 24-h dietary recall interviews were utilized to obtain energy intake.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed in R version 4.2.0 with the "Survey" package after considering the complex sampling design. All statistical tests were two-tailed, with the statistical significance set at p < 0.05. In the baseline population characteristics, we divided the study population into five groups based on quintiles of the CDAI. Continuous variables were expressed as means ± standard errors, and categorical variables were presented as percentages. The weighted linear regression method for continuous variables and the weighted chi-square test for categorical variables were used in the comparison of baseline characteristics. Given that depression and all-cause mortality were both dichotomous variables, weighted logistic regression models and weighted Cox proportional hazard regression models were used to assess the association of CDAI and covariates, depression, and all-cause mortality, respectively. The results of the weighted logistic regression models were expressed as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and for Cox proportional hazard regression models as hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

To exclude the influence of confounding factors, three models were constructed to explore the associations. Model 1 performed the analysis without adjustment for any covariates. Model 2 adjusted for age, sex, and race, and Model 3 adjusted for all covariates listed in Table 1. The robustness of the results was further evaluated by a linear trend test based on CDAI quintiles. Restricted cubic spline curves were employed to test for non-linear relationships between the outcome variable and exposure factors. Upon finding the non-linear relationship, the inflection point was calculated by a recursive algorithm, and a two-piecewise linear regression model was constructed. Stratified analyses and interactions were utilized to explore the characteristics of the relationship between CDAI with depression and all-cause mortality across different population subgroups.

Table 1 Characteristics of the study population.

Ethical approval

The NHANES protocol was approved by the National Center for Health Statistics of the Institutional Review Board, and all participants' informed consent was obtained. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations (declarations of Helsinki).

Results

Characteristics of the study population

In the baseline population of Table 1, men accounted for 46.22%, and women for 53.78%. The proportions of Mexican American, White, and Black were 5.04%, 75.6%, and 9.67%, respectively. Additionally, 61.07% of participants had a high school education or higher. Analysis revealed that individuals with higher CDAI were younger, more likely to be men, and white, with higher levels of education and income-to-poverty ratio. These individuals also reported higher energy intake, more frequent engagement in recreational activities, and exhibited lower risks of hypertension, diabetes, depression, and all-cause mortality, alongside reduced C-reactive protein levels.

Univariate analysis

The results of the univariate analysis are presented in Table 2. Women had a higher risk of depression and a lower risk of all-cause mortality compared to men. Depression showed a negative association with income-to-poverty ratio, vigorous recreational activities, CVD, stroke, hypertension, diabetes, BMI, waist, and CRP, and smoking status was found to be positively associated with depression. The covariates positively associated with all-cause mortality included age, cancer, CVD, stroke, hypertension, diabetes, waist, and energy intake.

Table 2 Univariate analyses.

Association between CDAI and depression and all-cause mortality

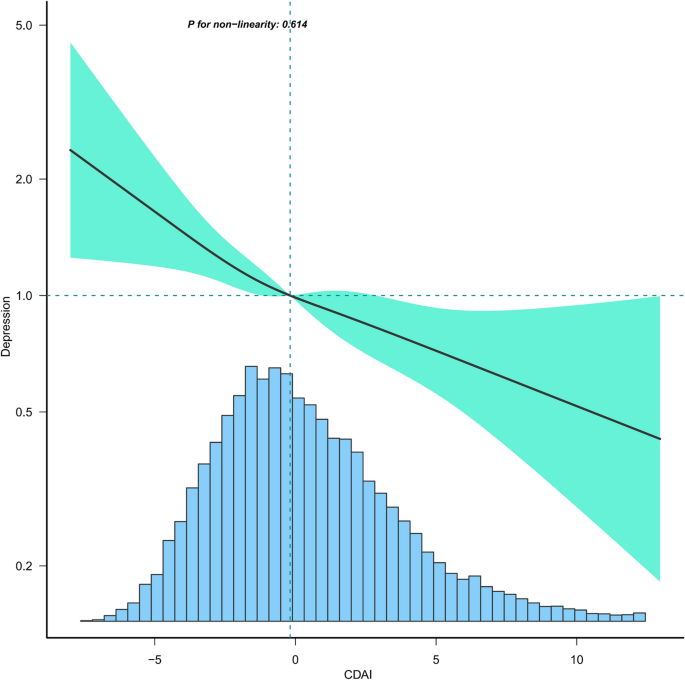

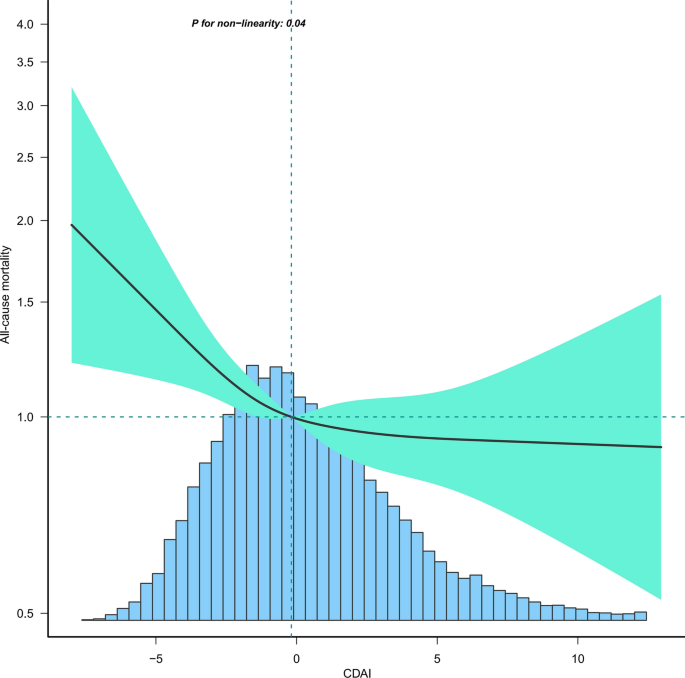

As shown in Table 3, the initial unadjusted analysis (Model 1) revealed that CADI was negatively associated with depression [0.74 (0.70, 0.79)] and all-cause mortality [0.84 (0.80, 0.88)]. This negative association persisted in regression models adjusted for all variables, with ORs for CDAI with depression at 0.77 (95% CI: 0.67, 0.89) and HRs for CDAI with all-cause mortality at 0.91 (95% CI: 0.83, 1.00). Comparing against the lowest quartile of CDAI (Q1) as the reference, higher CDAI was associated with a lower risk of depression, with ORs (95% CI) of 0.80 (0.61, 1.04), 0.67 (0.52, 0.87), 0.65 (0.48, 0.88), and 0.52 (0.36, 0.77). A similar trend was observed for all-cause mortality risk, with HRs (95% CI) of 0.87 (0.72, 1.05), 0.82 (0.69, 0.98), 0.77 (0.63, 0.96), and 0.75 (0.58, 0.96). Subsequent analysis using restricted cubic spline curves indicated a linear association between CDAI and depression (Fig. 2), whereas the relationship with all-cause mortality was non-linear with an inflection point of −0.19 (Fig. 3). This association was statistically significant only before this inflection point [0.71 (0.56, 0.89)] (Table 4).

Table 3 Association of composite dietary antioxidant index with depression and all-cause mortality in middle-aged and elderly population.

Figure 2

Association between CDAI and depression in middle-aged and elderly population. Age, sex, race, education level, income-to-poverty ratio, marital status, smoking status, drinking status, vigorous recreational activity, BMI, waist, stroke, diabetes, CVD, cancer, hypertension, energy intake, and CRP were adjusted.

Figure 3

Association between CDAI and all-cause mortality in middle-aged and elderly population. Age, sex, race, education level, income-to-poverty ratio, marital status, smoking status,drinking status, vigorous recreational activity, BMI, waist, stroke, diabetes, CVD, cancer, hypertension, energy intake, and CRP were adjusted.

Table 4 Threshold effect analysis of composite dietary antioxidant index on all-cause mortality in middle-aged and elderly population using a two-piecewise linear regression model.

Subgroup analysis

To explore the disparities in the relationship between CDAI and depression and all-cause mortality in various subgroups, stratified analyses and interactions were conducted in the middle-aged and elderly population (Table 5), and significant differences were found in these relationships only in the smoking population (P interaction = 0.0343 and P interaction = 0.0399). The associations between CDAI and depression and all-cause mortality were 0.76 (0.59, 0.97) and 0.69 (0.54, 0.89) for former smokers. For those who had never smoked, the relationship was 0.64 (0.51, 0.80) and 0.64 (0.51, 0.80).

Table 5 Subgroup logistic regression analysis for the association between CDAI and outcomes in middle-aged and elderly population.

Discussion

In the observational study among middle-aged and elderly Americans, higher CDAI was associated with a lower risk of depression and all-cause mortality. Further restricted cubic spline curves revealed a linear association of CDAI with depression and a non-linear association of CDAI with all-cause mortality. The inflection point was detected with the relationship being statistically significant only before the inflection point. To explore whether there were differences in the relationships among various subgroups, we conducted stratified analyses. To the best of our knowledge, this investigation represented the inaugural attempt to examine the association of CDAI with depression and all-cause mortality in a middle-aged and elderly population, and the most detailed subgroup analysis was performed.

The association between dietary antioxidants and depression and all-cause mortality has received increasing attention in recent years. Evidence suggested that only antioxidants derived from food sources, not dietary supplements, could offer protective benefits against depression[26](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR26 "Payne, M. E., Steck, S. E., George, R. R. & Steffens, D. C. Fruit, vegetable, and antioxidant intakes are lower in older adults with depression. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 112, 2022–2027. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2012.08.026

(2012)."). Observational meta-analyses have shown that the intakes of vitamins A, C, and E were inversely related to the incidence of depression[27](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR27 "Zhang, Y., Ding, J. & Liang, J. Associations of dietary vitamin a and beta-carotene intake with depression. A Meta-analysis of observational studies. Front. Nutr. 9, 881139.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.881139

(2022)."),[28](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR28 "Ding, J. & Zhang, Y. Associations of dietary vitamin C and E intake with depression. A meta-analysis of observational studies. Front. Nutr. 9, 857823.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.857823

(2022)."). A cross-sectional study in the United States indicated that higher zinc intake was associated with a lower risk of depression[29](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR29 "Li, Z., Wang, W., Xin, X., Song, X. & Zhang, D. Association of total zinc, iron, copper and selenium intakes with depression in the US adults. J. Affect. Disord. 228, 68–74.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.12.004

(2018)."). Interestingly, a study from Brazilian Farmers showed a non-linear negative correlation between dietary selenium intake and depression[30](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR30 "Ferreira de Almeida, T. L. et al. Association of selenium intake and development of depression in brazilian farmers. Front. Nutr. 8, 671377.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2021.671377

(2021)."). Similarly, a study on the general American population found a non-linear negative relationship between CDAI and depression[21](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR21 "Zhao, L. et al. Non-linear association between composite dietary antioxidant index and depression. Front. Public Health 10, 988727.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.988727

(2022)."). However, both our study and the study of Iranian adolescent girls revealed that the relationship between CDAI and depression was linearly negative[31](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR31 "Dehghan, P. et al. The association between dietary inflammatory index, dietary antioxidant index, and mental health in adolescent girls: An analytical study. BMC Public Health 22, 1513.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13879-2

(2022)."). Moreover, the findings on the relationship between dietary antioxidants and all-cause mortality were often inconsistent. A Korean study suggested that dietary zinc intake was associated with lower all-cause mortality[32](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR32 "Kwon, Y. J. et al. Dietary zinc intake and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in Korean middle-aged and older adults. Nutrients 15, 358.

https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15020358

(2023)."), contradicting a study in China, which found a positive correlation between zinc intake and all-cause mortality[33](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR33 "Shi, Z. et al. Association between dietary zinc intake and mortality among Chinese adults: Findings from 10-year follow-up in the Jiangsu Nutrition Study. Eur. J. Nutr. 57, 2839–2846.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-017-1551-7

(2018)."). Additionally, studies in China and the United States have shown that selenium intake was linked to reduced all-cause mortality[34](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR34 "Sun, J. W. et al. Dietary selenium intake and mortality in two population-based cohort studies of 133 957 Chinese men and women. Public Health Nutr. 19, 2991–2998.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980016001130

(2016)."),[35](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR35 "Hoque, B. & Shi, Z. Association between selenium intake, diabetes and mortality in adults: Findings from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2003–2014. Br. J. Nutr. 127, 1098–1105.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S000711452100177X

(2022)."). An elderly epidemiological study indicated that supplementing with vitamins C and E could lower the risk of all-cause mortality[36](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR36 "Losonczy, K. G., Harris, T. B. & Havlik, R. J. Vitamin E and vitamin C supplement use and risk of all-cause and coronary heart disease mortality in older persons: The Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 64, 190–196.

https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/64.2.190

(1996)."). However, a cohort study from the UK Biobank found no significant association between antioxidant use and all-cause mortality[37](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR37 "Behrendt, I., Eichner, G. & Fasshauer, M. Association of antioxidants use with all-cause and cause-specific mortality: A prospective study of the UK biobank. Antioxidants 9, 1287.

https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox9121287

(2020)."). In contrast, a cohort study of American cancer survivors revealed a significantly negative association between CDAI and the risk of mortality[38](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR38 "Tan, Z. et al. Association of dietary fiber, composite dietary antioxidant index and risk of death in tumor survivors: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001–2018. Nutrients 15, 2968.

https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15132968

(2023)."). Our research identified a non-linear relationship between CDAI and all-cause mortality, whereas a study on the general US population indicated a linear relationship between CDAI and all-cause mortality[39](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR39 "Wang, L. & Yi, Z. Association of the Composite dietary antioxidant index with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality: A prospective cohort study. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9, 993930.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2022.993930

(2022)."). Age and geographic differences may account for the inconsistent relationship of dietary antioxidants with depression and all-cause mortality. People in different geographical areas have different dietary habits, which leads to differences in antioxidant intake. In addition, middle-aged and elderly people tend to decline in physical function, which may affect the absorption and utilization of dietary antioxidants, consequently causing inconsistencies in the results of the studies.Although the specific mechanisms linking CDAI to depression and all-cause mortality in middle-aged and elderly population are still not well understood, some possible molecular mechanisms have been suggested in some studies. The first is oxidative stress. Depressed people often experience oxidative stress, characterized by an imbalance between oxygen free radicals and antioxidant substances in the body[40](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR40 "Salustri, C. et al. Oxidative stress and brain glutamate-mediated excitability in depressed patients. J. Affect. Disord. 127, 321–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2010.05.012

(2010)."). Oxygen free radicals are harmful molecules that interact with other molecules in the body and cause oxidative damage to cells and tissues[41](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR41 "Amirtharaj, G. J. et al. Role of oxygen free radicals, nitric oxide and mitochondria in mediating cardiac alterations during liver cirrhosis induced by thioacetamide. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 17, 175–184.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s12012-016-9371-1

(2017)."). Consuming a diet rich in antioxidants has been shown to lower oxidative stress and protect cells from damage caused by free radicals,thereby alleviating symptoms of depression[42](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR42 "Valko, M. et al. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 39, 44–84.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocel.2006.07.001

(2007)."). Studies have shown that vitamins C and E can trap free radicals and protect molecules such as membrane fatty acids, cholesterol, and proteins from oxidative damage, thus reducing the risk of developing chronic diseases such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes[43](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR43 "Riemersma, R. A. et al. Plasma antioxidants and coronary heart disease: Vitamins C and E, and selenium. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 44, 143–150 (1990)."),[44](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR44 "Fletcher, R. H. & Fairfield, K. M. Vitamins for chronic disease prevention in adults: Clinical applications. JAMA 287, 3127–3129.

https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.287.23.3127

(2002)."). Additionally, appropriate exogenous antioxidants can decrease the risk of mortality in diabetic population by balancing oxidative stress reactions[45](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR45 "Wang, W. et al. Dietary antioxidant indices in relation to all-cause and cause-specific mortality among adults with diabetes: A prospective cohort study. Front. Nutr. 9, 849727.

https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.849727

(2022)."). The second is chronic inflammation: Strong evidence suggests that neuroinflammation can promote the emergence and development of depression[46](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR46 "Manning, K. J. Hippocampal neuroinflammation and depression: Relevance to multiple sclerosis and other neuropsychiatric illnesses. Biol. Psychiatry 80, e1-2.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.05.001

(2016)."),[47](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR47 "Guo, B. et al. Neuroinflammation mechanisms of neuromodulation therapies for anxiety and depression. Transl. Psychiatry 13, 5.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-022-02297-y

(2023)."). The antioxidant properties of the diet are capable of diminishing the neuroinflammatory response by modulating the levels of inflammatory factors. Some studies have shown that dietary zinc, vitamin A, and E can lower levels of inflammatory factors such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), consequently reducing the impact of neuroinflammation on depression[48](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR48 "Xu, Y., Wang, C., Klabnik, J. J. & O’Donnell, J. M. Novel therapeutic targets in depression and anxiety: Antioxidants as a candidate treatment. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 12, 108–119.

https://doi.org/10.2174/1570159X11666131120231448

(2014)."). Other studies have shown that chronic inflammation is strongly associated with the development and progression of a variety of diseases, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, obesity, and cancer, as well as being associated with an increased risk of all-cause mortality[49](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR49 "Ehlers, S. & Kaufmann, S. H. Infection, inflammation, and chronic diseases: Consequences of a modern lifestyle. Trends Immunol. 31, 184–190.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2010.02.003

(2010)."),[50](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR50 "Leuti, A. et al. Bioactive lipids, inflammation and chronic diseases. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 159, 133–169.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2020.06.028

(2020)."). Antioxidant diets could significantly reduce inflammatory markers, improve chronic disease states, and reduce mortality risk[51](#ref-CR51 "Possa, L. O. et al. Association of dietary total antioxidant capacity with anthropometric indicators, C-reactive protein, and clinical outcomes in hospitalized oncologic patients. Nutrition 90, 111359.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2021.111359

(2021)."),[52](#ref-CR52 "Xu, X., Hall, J., Byles, J. & Shi, Z. Dietary pattern, serum magnesium, ferritin, C-reactive protein and anaemia among older people. Clin. Nutr. 36, 444–451.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2015.12.015

(2017)."),[53](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR53 "Yang, M. et al. Dietary antioxidant capacity is associated with improved serum antioxidant status and decreased serum C-reactive protein and plasma homocysteine concentrations. Eur. J. Nutr. 52, 1901–1911.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-012-0491-5

(2013)."). The third is neuroplasticity. Depressed patients often experience impaired neuroplasticity and reduced levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF). BDNF is known to be essential for the growth, differentiation, and survival of nerve cells, and BDNF also promotes neuronal connectivity and the formation of neural networks, which is a key factor in neuroplasticity[54](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR54 "Koo, J. W., Chaudhury, D., Han, M. H. & Nestler, E. J. Role of mesolimbic brain-derived neurotrophic factor in depression. Biol. Psychiatry 86, 738–748.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2019.05.020

(2019)."). Antioxidant diets can affect the production and release of neurotrophic factors such as neurotrophic factor (NGF) and BDNF[55](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR55 "Pronk, N. P. Neuroplasticity and the role of exercise and diet on cognition. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 113, 1392–1393.

https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqab083

(2021)."). These neurotrophic factors promote neuronal proliferation and synaptic plasticity, helping to maintain and enhance neurological health and thus improving depressive symptoms[56](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR56 "Wilkinson, S. T., Holtzheimer, P. E., Gao, S., Kirwin, D. S. & Price, R. B. Leveraging neuroplasticity to enhance adaptive learning: The potential for synergistic somatic-behavioral treatment combinations to improve clinical outcomes in depression. Biol. Psychiatry 85, 454–465.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2018.09.004

(2019)."). The fourth is neurotransmitters. Neurotransmitters such as serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine, are critical in regulating mood and depression[57](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR57 "Dicks, L. M. T. Our mental health is determined by an intrinsic interplay between the central nervous system, enteric nerves, and gut microbiota. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 38.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25010038

(2023)."). Antioxidants contribute to the protection of nerve cells from damage and improve neurotransmitter function, which can help prevent and treat depression. Specifically, the antioxidant vitamin C has been found to promote the release of neurotransmitters such as dopamine, norepinephrine, and 5-hydroxytryptamine from neurons, increasing the levels of neurotransmitters that influence communication between neurons[58](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR58 "Hansen, S. N., Schou-Pedersen, A. M. V., Lykkesfeldt, J. & Tveden-Nyborg, P. Spatial memory dysfunction induced by vitamin c deficiency is associated with changes in monoaminergic neurotransmitters and aberrant synapse formation. Antioxidants 7, 82.

https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox7070082

(2018)."). The fifth is the gut microbiota. Imbalances in the gut microbiota have been shown to be strongly associated with the development of depression and adverse outcomes of various diseases[59](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR59 "Fan, Y. & Pedersen, O. Gut microbiota in human metabolic health and disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 19, 55–71.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-020-0433-9

(2021)."). Compared with healthy individuals, the gut microbial composition of depressed patients changed, particularly in microbial diversity and relative abundance of specific bacterial taxa[60](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR60 "Simpson, C. A. et al. The gut microbiota in anxiety and depression: A systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 83, 101943.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101943

(2021)."),[61](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR61 "Valles-Colomer, M. et al. The neuroactive potential of the human gut microbiota in quality of life and depression. Nat. Microbiol. 4, 623–632.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-018-0337-x

(2019)."). In hemodialysis patients, the microbial diversity of non-survivors was significantly lower than that of survivors, especially in terms of amber fungi and anaerobic bacteria[62](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR62 "Lin, T. Y., Wu, P. H., Lin, Y. T. & Hung, S. C. Gut dysbiosis and mortality in hemodialysis patients. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 7, 20.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-021-00191-x

(2021)."). Studies have indicated that dietary antioxidant micronutrients can alleviate depressive symptoms and extend the life span of patients by modulating the abundance of the gut microbiota[63](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR63 "Xiong, R. G. et al. The role of gut microbiota in anxiety, depression, and other mental disorders as well as the protective effects of dietary components. Nutrients 15, 3258.

https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15143258

(2023)."),[64](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR64 "Bear, T. L. K. et al. The role of the gut microbiota in dietary interventions for depression and anxiety. Adv. Nutr. 11, 890–907.

https://doi.org/10.1093/advances/nmaa016

(2020).").Subgroup analyses were conducted to better explore differences among subgroups. Notably, in stratified analyses incorporating demographic characteristics, lifestyle factors, and comorbidities, a statistically significant interaction emerged specifically regarding smoking status. This finding indicated that those who had never smoked benefited more from an antioxidant-rich diet than those who had smoked and were still smoking. Studies have shown that smoking can lead to an increase in lipid peroxidation products and extracellular matrix protein degradation products, chemotaxis of activated neutrophils and macrophages, increased levels of circulating pro-inflammatory markers and oxidative stress markers, including reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels, superoxide dismutase (SOD), and glutathione peroxidase (GPx), along with a decrease in antioxidant levels[65](#ref-CR65 "Khanna, A., Guo, M., Mehra, M. & Royal, W. 3rd. Inflammation and oxidative stress induced by cigarette smoke in Lewis rat brains. J. Neuroimmunol. 254, 69–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneuroim.2012.09.006

(2013)."),[66](#ref-CR66 "Tong, X. et al. Cigarette smoke exposure impairs beta-cell function through activation of oxidative stress and ceramide accumulation. Mol. Metab. 37, 100975.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmet.2020.100975

(2020)."),[67](#ref-CR67 "van der Vaart, H., Postma, D. S., Timens, W. & ten Hacken, N. H. Acute effects of cigarette smoke on inflammation and oxidative stress: A review. Thorax 59, 713–721.

https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.2003.012468

(2004)."),[68](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR68 "Ignatowicz, E. et al. Exposure to alcohol and tobacco smoke causes oxidative stress in rats. Pharmacol. Rep. 65, 906–913.

https://doi.org/10.1016/s1734-1140(13)71072-7

(2013)."). Abnormal levels of inflammation and antioxidants can exacerbate the onset of depression and death[69](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR69 "Choi, M. J. et al. The malnutrition-inflammation-depression-arteriosclerosis complex is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and all-cause death in chronic hemodialysis patients. Nephron. Clin. Pract. 122, 44–52.

https://doi.org/10.1159/000348509

(2012)."),[70](/articles/s41598-024-60322-0#ref-CR70 "Jenkins, D. J. A. et al. Selenium, antioxidants, cardiovascular disease, and all-cause mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 112, 1642–1652.

https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqaa245

(2020)."). Thus, in people who have never smoked, an antioxidant diet may better reduce the risk of depression and all-cause mortality.Our study has several strengths. First, NHANES used standardized methods for data collection and analysis, coupled with stringent quality control of the data to ensure accuracy and reliability. Second, NHANES censuses thousands of participants from all over the country each year, enabling a large sample size and representativeness that provide a wide range of data on the health status of the US population. Third, we performed restricted cubic spline analyses to assess the dose–response relationship between CDAI and the risk of depression and all-cause mortality. Fourth, as global aging increases, it is important to study a large sample of data on middle-aged and elderly adults for health guidance and public health policy development in older populations. Fifth, a more comprehensive inclusion of risk factors affecting depression and all-cause mortality makes the study results more credible. There are also some limitations to this study. First, the observational study designs could only indicate that higher CDAI was associated with a lower risk of depression and all-cause mortality in middle-aged and older populations, whereas no conclusions about causality could be drawn. Second, given that the dietary data were obtained through follow-up interviews, and considering potential memory loss in the middle-aged and elderly population with depressive disorders, recall bias was an unavoidable limitation. Third, the dietary data were extracted from only two follow-up visits and therefore may not accurately reflect the typical dietary patterns of the subjects. Fourth, since this study was conducted on a middle-aged and older population in the United States, this limits the applicability of the findings to other demographics, and future research is necessary to examine the relevance of these findings in different international contexts.

Conclusion

In this study of middle-aged and elderly Americans, CDAI was linearly negatively associated with depression and non-linearly negatively associated with all-cause mortality. The stratified analysis revealed differences between populations with different smoking statuses, and these findings may help public health authorities tailor policies to prevent and improve people's emotional states and increase longevity. Further basic research will be required to discover the molecular biological mechanisms underpinning these associations.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available at https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.

References

- Smith, K. Mental health: A world of depression. Nature 515, 181. https://doi.org/10.1038/515180a (2014).

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Monroe, S. M. & Harkness, K. L. Major depression and its recurrences: Life course matters. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 18, 329–357. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-072220-021440 (2022).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Douglas, K. M., Porter, R. J., Knight, R. G. & Maruff, P. Neuropsychological changes and treatment response in severe depression. Br. J. Psychiatry 198, 115–122. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.110.080713 (2011).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - McCarron, R. M., Shapiro, B., Rawles, J. & Luo, J. Depression. Ann. Intern. Med. 174, 65–80. https://doi.org/10.7326/AITC202105180 (2021).

Article Google Scholar - Kessler, R. C. et al. Anxious and non-anxious major depressive disorder in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 24, 210–226. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796015000189 (2015).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - O’Leary, K. Global increase in depression and anxiety. Nat. Med. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41591-021-00064-y (2021).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Kosciuszko, M., Steptoe, A. & Ajnakina, O. Genetic propensity, socioeconomic status, and trajectories of depression over a course of 14 years in older adults. Transl. Psychiatry 13, 68. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-023-02367-9 (2023).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Leone, M. et al. Genetic and environmental contribution to the co-occurrence of endocrine-metabolic disorders and depression: A Nationwide Swedish Study of Siblings. Am. J. Psychiatry 179, 824–832. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.21090954 (2022).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Swainson, J. et al. Diet and depression: A systematic review of whole dietary interventions as treatment in patients with depression. J. Affect. Disord. 327, 270–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.01.094 (2023).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Bisaglia, M. Mediterranean diet and Parkinson’s disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24010042 (2022).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Ballarini, T. et al. Mediterranean diet, alzheimer disease biomarkers and brain atrophy in old age. Neurology 96, e2920-2932. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000012067 (2021).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Goyal, P. et al. The Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet pattern and incident heart failure. J. Card. Fail. 27, 512–521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cardfail.2021.01.011 (2021).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Sofi, F. et al. Low-calorie vegetarian versus mediterranean diets for reducing body weight and improving cardiovascular risk profile: CARDIVEG Study (Cardiovascular Prevention With Vegetarian Diet). Circulation 137, 1103–1113. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030088 (2018).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Chen, L. et al. Different oral and gut microbial profiles in those with Alzheimer’s disease consuming anti-inflammatory diets. Front. Nutr. 9, 974694. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.974694 (2022).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - McNamara, S. L. et al. Anti-inflammatory therapy enables robot-actuated regeneration of aged muscle. Sci. Robot. 8, eadd9369. https://doi.org/10.1126/scirobotics.add9369 (2023).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Kaluza, J., Levitan, E. B., Michaelsson, K. & Wolk, A. Anti-inflammatory diet and risk of heart failure: Two prospective cohort studies. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 22, 676–682. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.1746 (2020).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Shah, B. et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of a vegan diet versus the American Heart Association-recommended diet in coronary artery disease trial. J. Am. Heart. Assoc. 7, e011367. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.118.011367 (2018).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Lee, A. et al. Vitamin E, alpha-tocopherol, and its effects on depression and anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients 14, 656. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu1403065 (2022).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Yu, Y. C. et al. Composite dietary antioxidant index and the risk of colorectal cancer: Findings from the Singapore Chinese Health Study. Int. J. Cancer 150, 1599–1608. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.33925 (2022).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Vahid, F., Rahmani, D. & Davoodi, S. H. Validation of Dietary Antioxidant Index (DAI) and investigating the relationship between DAI and the odds of gastric cancer. Nutr. Metab. 17, 102. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12986-020-00529-w (2020).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Zhao, L. et al. Non-linear association between composite dietary antioxidant index and depression. Front. Public Health 10, 988727. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.988727 (2022).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Wright, M. E. et al. Development of a comprehensive dietary antioxidant index and application to lung cancer risk in a cohort of male smokers. Am. J. Epidemiol. 160, 68–76. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwh173 (2004).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Smagula, S. F. et al. Association of 24-hour activity pattern phenotypes with depression symptoms and cognitive performance in aging. JAMA Psychiatry 79, 1023–1031. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.2573 (2022).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Patel, P. O., Patel, M. R. & Baptist, A. P. Depression and asthma outcomes in older adults: Results from the national health and nutrition examination survey. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 5, 1691–1697. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2017.03.034 (2017).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Han, Y. Y., Forno, E., Marsland, A. L., Miller, G. E. & Celedon, J. C. Depression, asthma, and bronchodilator response in a nationwide study of US adults. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 4, 68–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaip.2015.10.004 (2016).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Payne, M. E., Steck, S. E., George, R. R. & Steffens, D. C. Fruit, vegetable, and antioxidant intakes are lower in older adults with depression. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 112, 2022–2027. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2012.08.026 (2012).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Zhang, Y., Ding, J. & Liang, J. Associations of dietary vitamin a and beta-carotene intake with depression. A Meta-analysis of observational studies. Front. Nutr. 9, 881139. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.881139 (2022).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Ding, J. & Zhang, Y. Associations of dietary vitamin C and E intake with depression. A meta-analysis of observational studies. Front. Nutr. 9, 857823. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.857823 (2022).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Li, Z., Wang, W., Xin, X., Song, X. & Zhang, D. Association of total zinc, iron, copper and selenium intakes with depression in the US adults. J. Affect. Disord. 228, 68–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.12.004 (2018).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Ferreira de Almeida, T. L. et al. Association of selenium intake and development of depression in brazilian farmers. Front. Nutr. 8, 671377. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2021.671377 (2021).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Dehghan, P. et al. The association between dietary inflammatory index, dietary antioxidant index, and mental health in adolescent girls: An analytical study. BMC Public Health 22, 1513. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13879-2 (2022).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Kwon, Y. J. et al. Dietary zinc intake and all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in Korean middle-aged and older adults. Nutrients 15, 358. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15020358 (2023).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Shi, Z. et al. Association between dietary zinc intake and mortality among Chinese adults: Findings from 10-year follow-up in the Jiangsu Nutrition Study. Eur. J. Nutr. 57, 2839–2846. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-017-1551-7 (2018).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Sun, J. W. et al. Dietary selenium intake and mortality in two population-based cohort studies of 133 957 Chinese men and women. Public Health Nutr. 19, 2991–2998. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980016001130 (2016).

Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Hoque, B. & Shi, Z. Association between selenium intake, diabetes and mortality in adults: Findings from National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2003–2014. Br. J. Nutr. 127, 1098–1105. https://doi.org/10.1017/S000711452100177X (2022).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Losonczy, K. G., Harris, T. B. & Havlik, R. J. Vitamin E and vitamin C supplement use and risk of all-cause and coronary heart disease mortality in older persons: The Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 64, 190–196. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/64.2.190 (1996).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Behrendt, I., Eichner, G. & Fasshauer, M. Association of antioxidants use with all-cause and cause-specific mortality: A prospective study of the UK biobank. Antioxidants 9, 1287. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox9121287 (2020).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Tan, Z. et al. Association of dietary fiber, composite dietary antioxidant index and risk of death in tumor survivors: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2001–2018. Nutrients 15, 2968. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15132968 (2023).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Wang, L. & Yi, Z. Association of the Composite dietary antioxidant index with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality: A prospective cohort study. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9, 993930. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2022.993930 (2022).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Salustri, C. et al. Oxidative stress and brain glutamate-mediated excitability in depressed patients. J. Affect. Disord. 127, 321–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2010.05.012 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Amirtharaj, G. J. et al. Role of oxygen free radicals, nitric oxide and mitochondria in mediating cardiac alterations during liver cirrhosis induced by thioacetamide. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 17, 175–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12012-016-9371-1 (2017).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Valko, M. et al. Free radicals and antioxidants in normal physiological functions and human disease. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 39, 44–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocel.2006.07.001 (2007).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Riemersma, R. A. et al. Plasma antioxidants and coronary heart disease: Vitamins C and E, and selenium. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 44, 143–150 (1990).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Fletcher, R. H. & Fairfield, K. M. Vitamins for chronic disease prevention in adults: Clinical applications. JAMA 287, 3127–3129. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.287.23.3127 (2002).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Wang, W. et al. Dietary antioxidant indices in relation to all-cause and cause-specific mortality among adults with diabetes: A prospective cohort study. Front. Nutr. 9, 849727. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2022.849727 (2022).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Manning, K. J. Hippocampal neuroinflammation and depression: Relevance to multiple sclerosis and other neuropsychiatric illnesses. Biol. Psychiatry 80, e1-2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2016.05.001 (2016).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Guo, B. et al. Neuroinflammation mechanisms of neuromodulation therapies for anxiety and depression. Transl. Psychiatry 13, 5. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-022-02297-y (2023).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Xu, Y., Wang, C., Klabnik, J. J. & O’Donnell, J. M. Novel therapeutic targets in depression and anxiety: Antioxidants as a candidate treatment. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 12, 108–119. https://doi.org/10.2174/1570159X11666131120231448 (2014).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Ehlers, S. & Kaufmann, S. H. Infection, inflammation, and chronic diseases: Consequences of a modern lifestyle. Trends Immunol. 31, 184–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2010.02.003 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Leuti, A. et al. Bioactive lipids, inflammation and chronic diseases. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 159, 133–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2020.06.028 (2020).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Possa, L. O. et al. Association of dietary total antioxidant capacity with anthropometric indicators, C-reactive protein, and clinical outcomes in hospitalized oncologic patients. Nutrition 90, 111359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2021.111359 (2021).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Xu, X., Hall, J., Byles, J. & Shi, Z. Dietary pattern, serum magnesium, ferritin, C-reactive protein and anaemia among older people. Clin. Nutr. 36, 444–451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2015.12.015 (2017).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Yang, M. et al. Dietary antioxidant capacity is associated with improved serum antioxidant status and decreased serum C-reactive protein and plasma homocysteine concentrations. Eur. J. Nutr. 52, 1901–1911. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-012-0491-5 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Koo, J. W., Chaudhury, D., Han, M. H. & Nestler, E. J. Role of mesolimbic brain-derived neurotrophic factor in depression. Biol. Psychiatry 86, 738–748. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2019.05.020 (2019).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Pronk, N. P. Neuroplasticity and the role of exercise and diet on cognition. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 113, 1392–1393. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqab083 (2021).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Wilkinson, S. T., Holtzheimer, P. E., Gao, S., Kirwin, D. S. & Price, R. B. Leveraging neuroplasticity to enhance adaptive learning: The potential for synergistic somatic-behavioral treatment combinations to improve clinical outcomes in depression. Biol. Psychiatry 85, 454–465. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2018.09.004 (2019).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Dicks, L. M. T. Our mental health is determined by an intrinsic interplay between the central nervous system, enteric nerves, and gut microbiota. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms25010038 (2023).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Hansen, S. N., Schou-Pedersen, A. M. V., Lykkesfeldt, J. & Tveden-Nyborg, P. Spatial memory dysfunction induced by vitamin c deficiency is associated with changes in monoaminergic neurotransmitters and aberrant synapse formation. Antioxidants 7, 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/antiox7070082 (2018).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Fan, Y. & Pedersen, O. Gut microbiota in human metabolic health and disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 19, 55–71. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-020-0433-9 (2021).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Simpson, C. A. et al. The gut microbiota in anxiety and depression: A systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 83, 101943. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101943 (2021).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Valles-Colomer, M. et al. The neuroactive potential of the human gut microbiota in quality of life and depression. Nat. Microbiol. 4, 623–632. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-018-0337-x (2019).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Lin, T. Y., Wu, P. H., Lin, Y. T. & Hung, S. C. Gut dysbiosis and mortality in hemodialysis patients. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 7, 20. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41522-021-00191-x (2021).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Xiong, R. G. et al. The role of gut microbiota in anxiety, depression, and other mental disorders as well as the protective effects of dietary components. Nutrients 15, 3258. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15143258 (2023).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Bear, T. L. K. et al. The role of the gut microbiota in dietary interventions for depression and anxiety. Adv. Nutr. 11, 890–907. https://doi.org/10.1093/advances/nmaa016 (2020).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Khanna, A., Guo, M., Mehra, M. & Royal, W. 3rd. Inflammation and oxidative stress induced by cigarette smoke in Lewis rat brains. J. Neuroimmunol. 254, 69–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneuroim.2012.09.006 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Tong, X. et al. Cigarette smoke exposure impairs beta-cell function through activation of oxidative stress and ceramide accumulation. Mol. Metab. 37, 100975. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmet.2020.100975 (2020).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - van der Vaart, H., Postma, D. S., Timens, W. & ten Hacken, N. H. Acute effects of cigarette smoke on inflammation and oxidative stress: A review. Thorax 59, 713–721. https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.2003.012468 (2004).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Ignatowicz, E. et al. Exposure to alcohol and tobacco smoke causes oxidative stress in rats. Pharmacol. Rep. 65, 906–913. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1734-1140(13)71072-7 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Choi, M. J. et al. The malnutrition-inflammation-depression-arteriosclerosis complex is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and all-cause death in chronic hemodialysis patients. Nephron. Clin. Pract. 122, 44–52. https://doi.org/10.1159/000348509 (2012).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Jenkins, D. J. A. et al. Selenium, antioxidants, cardiovascular disease, and all-cause mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 112, 1642–1652. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqaa245 (2020).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Funding

This work was supported by Shandong Provincial Medical and Health Science and Technology Development Program Project (Grant no. 202203070909) and Shandong Province Chinese Medicine Science and Technology Project (Grant no. 2021M150).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- University City Hospital, Affiliated Hospital of Shandong University of Chinese Medicine, Jinan, China

Juanjuan Luo - Affiliated Hospital of Shandong University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Jinan, China

Xiying Xu & Leiyong Zhao - Shandong University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Jinan, China

Yiyan Sun - Neck Shoulder and Lumbocrural Pain Hospital of Shandong First Medical University, Shandong First Medical University (Shandong Academy of Medical Sciences), Jinan, China

Xixue Lu

Authors

- Juanjuan Luo

- Xiying Xu

- Yiyan Sun

- Xixue Lu

- Leiyong Zhao

Contributions

X.X.L. and L.Y.Z. are co-corresponding authors. J.J.L. developed the project, designed the research and wrote the main manuscript. X.Y.X. revised the manuscript and analyzed the data. Y.Y.S. analyzed and interpreted the data. X.X.L. and L.Y.Z. design the research and supervised. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence toXixue Lu or Leiyong Zhao.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Luo, J., Xu, X., Sun, Y. et al. Association of composite dietary antioxidant index with depression and all-cause mortality in middle-aged and elderly population.Sci Rep 14, 9809 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-60322-0

- Received: 28 November 2023

- Accepted: 22 April 2024

- Published: 29 April 2024

- Version of record: 29 April 2024

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-60322-0