CXCL9, IL2RB, and SPP1, potential diagnostic biomarkers in the co-morbidity pattern of atherosclerosis and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (original) (raw)

Introduction

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) refers to the development of hepatic steatosis in the absence of secondary causes such as excessive alcohol consumption. It encompasses conditions including simple steatohepatitis, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), and liver cirrhosis, with NASH being the inflammatory subtype of NAFLD1. It is estimated that NAFLD affects approximately 25% of the global population, with NASH accounting for 59.10% of cases within the NAFLD patient group, a number that is increasing year by year2. NASH causes more severe liver damage than simple steatohepatitis and is more likely to result in liver fibrosis, further progression to cirrhosis or liver cancer, and even death3,4. NASH has become the second-leading cause of liver transplantation; however, there are no drugs approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and treatment options remain very limited5,6.

Atherosclerosis (AS) is a chronic inflammatory pathological change that occurs in the vascular wall and is characterized by lipid deposition and immune cell infiltration. This condition can result in various cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), such as ischemic heart disease and stroke7. CVDs is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, with an increasing trend year by year8. AS serves as the pathological basis of CVDs and has been the subject of research by the SCAPIS project in Sweden. Among 25,182 people with no known coronary heart disease, 42.1% showed evidence of atherosclerosis on coronary computed tomography angiography9. The current treatment of AS is dominated by statins for lipid lowering; however, there is still a significant residual risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease even under optimal statin therapy10.

Chronic diseases are intricately linked, and some often occur in conjunction with each other. AS and NASH are common clinical chronic diseases. A high-fat diet disrupts metabolic rhythms, affecting and altering communication between tissues or organs, which in turn weakens synergistic metabolic associations between organs and causes abnormalities in biometabolism. This disruption contributes to the development of co-morbidities of AS and NASH11,12. Recent clinical studies have shown that NASH increases the risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; patients with NAFLD have twice the risk of cardiovascular disease, and individuals with NAFLD/NASH are twice as likely to die from cardiovascular disease as from liver disease13,14,15. Therefore, studies on co-morbidity patterns can help to understand the characteristics of chronic disease co-morbidities and guide clinical diagnosis, treatment, management, and etiological research into these co-morbidities.

However, the current state of co-morbidity presents unprecedented challenges, as disease-specific diagnostic and therapeutic protocols based on single-disease guidelines may not be suitable for patients with co-morbidities. Moreover, research into the diagnosis, treatment, and underlying mechanisms of co-morbidities is crucial for medical advancement, and the development of coping strategies is particularly important. The guidelines acknowledge that invasive liver biopsy is the gold standard for diagnosing NASH, but its limitations, such as sampling bias, poor acceptability, and serious complications including mortality, bleeding, and pain, have highlighted an urgent need for noninvasive methods to avoid biopsy in the diagnosis of NAFLD16. Biomarkers are ideally suited for diagnosing co-morbidities of AS and NASH, which enable the non-invasive detection of these conditions at their onset and are instrumental in tracking the progression of the diseases and monitoring the effectiveness of treatments. Moreover, biomarkers offer insights into the underlying mechanisms of these co-morbidities, which is crucial for developing targeted therapies. This study offers diagnostic methods and potential therapeutic targets for the co-morbidity of NASH and AS, plays a key role in advancing the treatment of these diseases, and provides new ideas for the development of new drugs.

Materials and methods

Bioinformatics analysis

Subjects and dataset acquisition

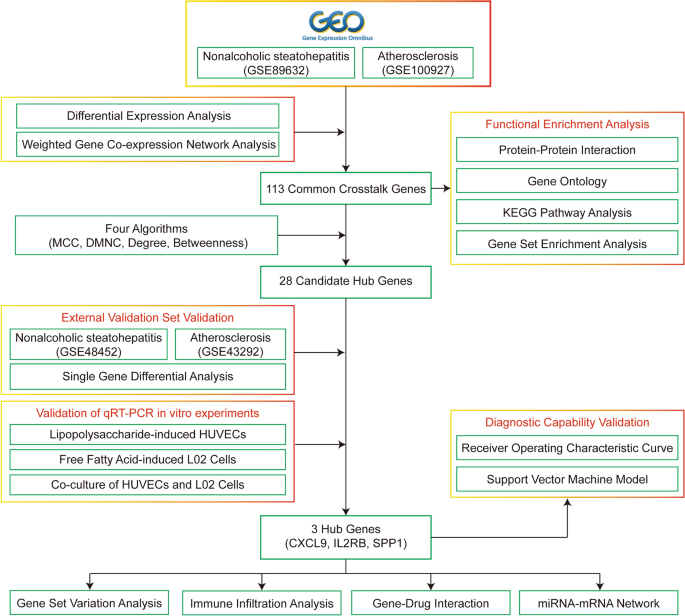

The entire study process is illustrated in Fig. 1, and the study code is detailed in Supplementary Material A. First, gene expression profiles (GSE100927 and GSE89632) were retrieved from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) database searching under the keywords “atherosclerosis” and “nonalcoholic steatohepatitis,” with the species filter set to “Homo sapiens.” The datasets were selected based on the following criteria: (1) the presence of both control and disease groups; (2) specific test tissues for AS (artery) and NASH (liver); (3) a minimum sample size of 10 cases per group. The AS-related dataset, GSE100927, includes mRNA sequencing data from 35 healthy control arteries and 69 arteries from atherosclerotic patients, totaling 104 samples17. The NASH-related dataset, GSE89632, includes mRNA sequencing data from 24 healthy liver tissues and 19 liver tissues from NASH patients, totaling 43 samples18.

Figure 1

Flow chart of this study.

Identification of common crosstalk genes in AS and NASH

The common crosstalk genes of AS and NASH were screened using the “limma” and “WGCNA” R packages in the R software19,20. The differentially expressed genes (DEGs) for AS-GSE100927 were initially identified using the “limma” R package, comparing the disease and control groups with a significance threshold of P < 0.05 and |logFC| > 0.5 for DEG selection. Subsequently, the samples were clustered using the “WGCNA” R package, outliers were removed, and co-expression networks were constructed from the gene expression matrix of the remaining samples. Appropriate soft thresholds were determined, gene modules were identified, and the most relevant gene modules were selected. The crosstalk genes for AS were then obtained by intersecting the genes from the difference analysis with those from the Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA). The crosstalk genes for NASH-GSE89632 were identified in a similar manner. Finally, the common crosstalk genes between AS and NASH were determined by intersecting the crosstalk genes of NASH with AS, ensuring that the genes expressed in the same direction (either upregulated or downregulated).

Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis

The common crosstalk genes were imported into the David database (https://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov/) for GO and KEGG analysis, with P < 0.05 set as the screening condition21,22.

Construction of protein–protein interaction (PPI) network and screening of candidate Hub genes

The common crosstalk genes were imported into the STRING database (https://www.string-db.org/) to construct a PPI network, and “Homo _sapiens_” was selected as a species, with a “score” of ≥ 0.423. The topology analysis of PPI networks was performed using the Cytoscape plugin “CytoHubba,” and four algorithms (MCC, DMNC, Degree, and Betweenness) were selected to screen candidate Hub genes24.

Validation of Hub gene expression

The expression levels of the candidate Hub genes were verified in the datasets GSE43292 for AS and GSE48452 for NASH. GSE43292 contained 32 carotid tissues from AS patients and 32 control tissues25, while GSE48452 contained 17 liver tissues from NASH patients and 12 control liver tissues26. The Wilcoxon test was used to compare the two datasets, with P < 0.05 considered significant.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves

ROC curves for the Hub genes were generated using the “pROC” R package to evaluate the diagnostic efficacy of individual Hub genes27.

Support vector machine (SVM)

SVM models were constructed in the training and validation sets using the “e1071” R package (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/e1071/index.html), and then the ROC curves were used to evaluate the joint diagnosis of Hub genes' performance.

Immune infiltration analysis

The CIBERSORT deconvolution algorithm was applied to gene microarray data to quantify the infiltration of 22 immune cells28. Differences between groups were compared using the Wilcoxon test, and the results were visualized with the “vioplot” R package29. Spearman correlation analysis was then conducted to explore the relationships between Hub genes and immune cells.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)

The “GSEA” R package was utilized to investigate the pathways related to hub genes and to calculate the correlation between hub genes and other genes30. Genes were sorted by their correlation values in descending order, and this sorted gene set was used for enrichment analysis. The KEGG signaling pathway set, referred to as a “predefined set,” was assessed for its enrichment within the gene set.

Gene set variation analysis (GSVA)

The “GSVA” R package was employed to perform a GSVA enrichment analysis for each model gene, and a significant change was considered to have occurred if the |t| value of the GSVA score's t statistic exceeded two31.

Hub gene–drug interaction

Hub genes were imported into the DGIbd database (https://dgidb.org/) to identify drug candidates and screen for FDA-approved drugs.

Construction of common miRNA–mRNA network

The miRTarbase (http://mirtarbase.mbc.nctu.edu.tw/php/index.php) is an experimentally validated miRNA target interaction database32. MiRNAs targeting Hub genes were obtained from the miRTarbase database; four bioinformatics tools were then utilized to predict miRNA target genes, including the TargetScan database (http://www.targetscan.org/vert_72/), the TarBase database (https://dianalab.e-ce.uth.gr/tarbasev9), the miRmap database (https://mirmap.ezlab.org/), and the miRDB database (https://mirdb.org/), where miRNAs of Hub genes were selected by at least three tools at the time of prediction33.

Statistical analysis

All bioinformatics statistical analyses were conducted using R software, with P < 0.05 considered significant.

Cellular experimental validation of Hub gene

Reagents and instruments

Experimental cell: Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) (Procell, Cat.CL-0675); Human normal liver L02 cells (iCell, Cat.h054).

The following reagents were used: Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Solarbio, Cat.L8880); Oleic acid (Solarbio, Cat.SC9320); Palmitic acid (Solarbio, Cat.SP8060); Fetal bovine serum (Biosharp, Cat.BL205A); Trypsin–EDTA Solution (Biosharp, Cat.BL512A); RPMI-1640 cell culture medium (gibco, Cat.C11875500BT); Penicillin/Streptomycin (Biosharp, Cat.BL505A); Oil red O (ORO) staining Kit (Solarbio, Cat.G1262); Paraformaldehyde, 4% (Solarbio, Cat.P1110); Cell counting kit-8 (Solarbio, Cat.CA1210); Serum-free cell freezing medlum (Biosharp, Cat.BL203B); RNA extraction solution (Servicebio, Cat.G3013); Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) (Servicebio, Cat.G4202); Chloroform substitute (Servicebio, Cat.G3014); RNA lysate (Servicebio, Cat.G3029); Water Nuclease-Free (Servicebio, Cat.G4700); SweScript All-in-One RT SuperMix for qPCR (One-Step gDNA Remover) (Servicebio, Cat.G3337); 2×Universal Blue SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (Servicebio, Cat.G3326); isopropanol (Sinopharm, Cat.80109218); Anhydrous ethanol (Sinopharm, Cat.10009218).

The following instruments were used: Inverted microscope (Nikon, Eclipse Ci); Microplate reader (Tecan, Spark 10M); Vortex mixer (Servicebio, SMV-3500); Sealing instrument (Servicebio, FS-A20); Microplate centrifuge (Servicebio, SMP-2); High-speed frozen microcentrifuge (DragonLab, D3024R); Fluorescent quantitative PCR instrument (Bio-rad, CFX Connect); PCR instrument (Eastwin, ETC811).

Cell culture

The HUVECs and L02 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 cell culture medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin, respectively, and incubated at 37 °C in humidified 5% CO2. The cells were used from passages 3–834.

L02 cells and HUVECs were divided into 4 groups: (1) Control L02 group (CL): L02 cells are cultured normally without any treatment; (2) Model L02 group (ML): L02 cells were treated with free fatty acid (FFA) (2.0 mmol/L) (oleic acid = 2 mmol/L, palmitic acid = 1 mmol/L) for 24 h; (3) Control HUVECs group (CH): HUVECs are cultured normally without any treatment; (4) Model HUVECs group (MH): HUVECs were treated with LPS (1.0 μg/mL) for 24 h; (5) The control L02 cell and the control HUVECs cell co-culture group (CL + CH): L02 and HUVECs were co-cultured normally for 24 h without any treatment; (6) The control L02 cell and the model HUVECs cell co-culture group (CL + MH): L02 cells were cultured untreated for 24 h, co-cultured with HUVECs after changing the culture medium, and treated with LPS for 24 h; (7) The model L02 cell and the control HUVECs cell co-culture group (ML + CH): L02 cells were treated with FFA for 24 h and co-cultured with HUVECs for 24 h after changing the culture medium; (8) The model L02 cell and the model HUVECs cell co-culture group (ML + MH): L02 cells were treated with FFA for 24 h, HUVECs were treated with LPS for 24 h, and then co-cultured with L02 cell supernatant.

ORO staining

Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min and then rinsed three times with PBS. Subsequently, the cells were stained with ORO for 1 h at room temperature.

Cell viability assay

Cells were cultured in 96-well plates at a density of 2 × 105 per well. After treatment with different interventions for 24 h, 10 µL of CCK-8 reagent was added to each well and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. The absorbance was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from cell lines using Trizol total RNA isolation reagent (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s specifications and treated with Turbo DNase (Ambion). cDNA was synthesized from 0.5 mg of total RNA using random hexamers with the TaqMan cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems). Primers were designed using Primer Express v3.0 software, and real-time PCR was performed using SYBR Select Master Mix (Applied Bio-Systems) (Table 1). All reactions were carried out on the 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystem). The average of three independent analyses for each gene and sample was calculated using the DD threshold cycle (Ct) method and normalized to the endogenous reference control gene β-actin. The above primers were synthesized by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd (https://www.sangon.com/).

Table 1 A list of the primers used in the qRT-PCR.

Statistical analysis

Cells were observed and photographed under a fluorescence microscope. The stained area was quantified using Image J software. Results were shown as mean ± SD and analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Differences with P < 0.05 was considered significant, and statistical tests for each experiment are detailed in the relevant figure legends. Data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism Software 9.5.

Results

Identification of common crosstalk genes in AS and NASH

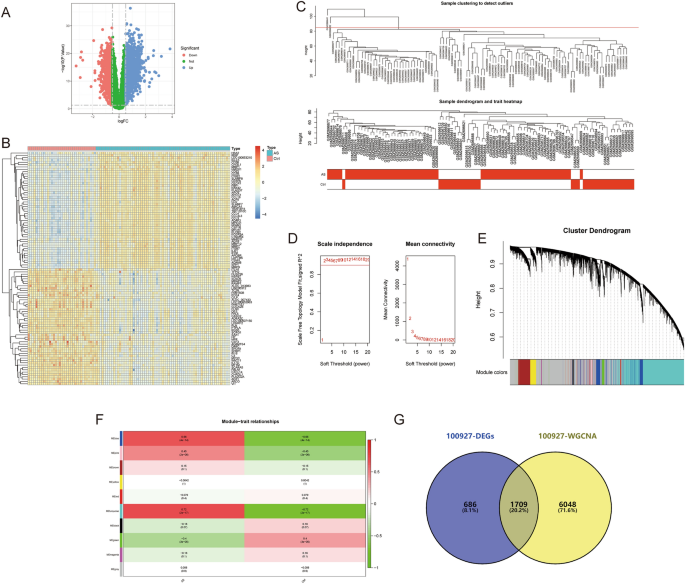

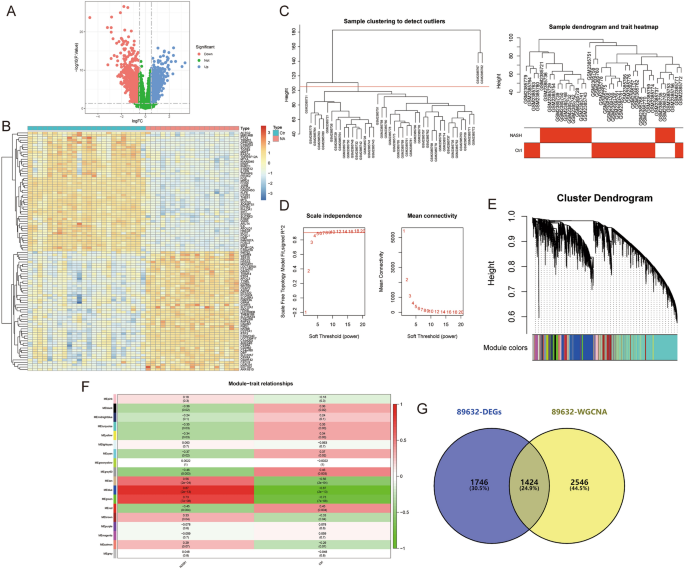

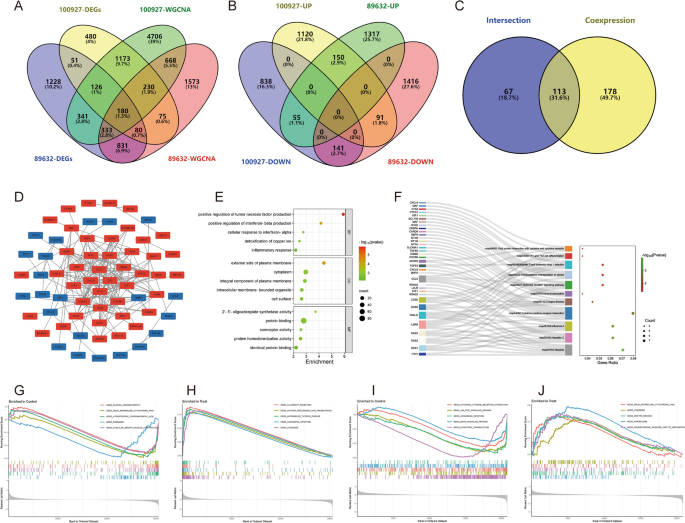

The data for this study is presented in Supplementary Material B. The differential gene expression analysis for AS-GSE100927 identified 2399 DEGs (Fig. 2A,B). WGCNA identified the “turquoise” module with the highest correlation to AS, containing 7757 genes (Fig. 2C–F). 1709 crosstalk genes for AS were obtained after intersection (Fig. 2G). For NASH-GSE89632, the differential gene expression analysis identified 3170 DEGs (Fig. 3A,B), and WGCNA identified the “blue” module with the highest correlation to NASH, containing 3970 genes (Fig. 3C–F); 1424 crosstalk genes of NASH were obtained after intersection (Fig. 3G). Finally, 180 common crosstalk genes between AS and NASH were identified (Fig. 4A), with 113 expressed in the same direction (Fig. 4B,C).

Figure 2

Identification of AS (GSE100927) crosstalk genes by differential expression analysis and WGCNA. (A,B) Volcano plot (A) and heatmap (B) for differentially expressed genes (DEGs). (C) Sample clustering plot after removing outlier samples. (D) Soft-thresholding power analysis was used to obtain the scale-free fit index of network topology. (E) Dendrogram of all genes clustered based on the measurement of dissimilarity (1-TOM). (F) Heatmap of the correlation between the module eigengenes and clinical traits of AS. (G) Venn diagram showing the 1709 crosstalk genes.

Figure 3

Identification of NASH (GSE89632) crosstalk genes by differential expression analysis and WGCNA. (A,B) Volcano plot (A) and heatmap (B) for DEGs. (C) Sample clustering plot after removing outlier samples. (D) Soft-thresholding power analysis was used to obtain the scale-free fit index of network topology. (E) Dendrogram of all genes clustered based on the measurement of dissimilarity (1-TOM). (F) Heatmap of the correlation between the module eigengenes and clinical traits of NASH. (G) Venn diagram showing the 1424 crosstalk genes.

Figure 4

Identification and functional enrichment analysis of AS and NASH common crosstalk genes. (A–C) Venn diagram showing 113 common crosstalk genes expressed in the same direction. (D–F) The PPI network (D), GO (E), and KEGG (F) enrichment analysis of common crosstalk genes. (G,H). The GSEA for normal (G) and AS (H) samples. (I,J) The GSEA for normal (I) and NASH (J) samples.

Enrichment analysis of common crosstalk genes

GO and KEGG analyses were performed to explore the biological functions and pathways involved. The GO analysis encompassed biological process (BP), cellular component (CC), and molecular function (MF). The 113 common crosstalk genes were imported into the David database for GO and KEGG analysis, of which 57 were correlated with BP, 8 with CC, and 13 with MF, and 11 signaling pathways were obtained by KEGG analysis (P < 0.05). The results suggest that the pathogenesis of the co-morbidity pattern of AS and NAHS is related to inflammatory and immune responses, copper ion metabolism, and notably, the NOD-like receptor signaling pathway (Fig. 4E,F).

To determine the potential functions of these genes in GSE100927 and GSE89632, GSEA was used to identify differential regulatory pathways and signaling pathways activated in AS and NASH. The comprehensive analysis indicates that the common pathogenesis of AS and NASH likely involves cardiomyopathy, immunity, metabolism, and cytokine-mediated signaling pathways, such as the JAK-STAT signaling pathway (Fig. 4G–J).

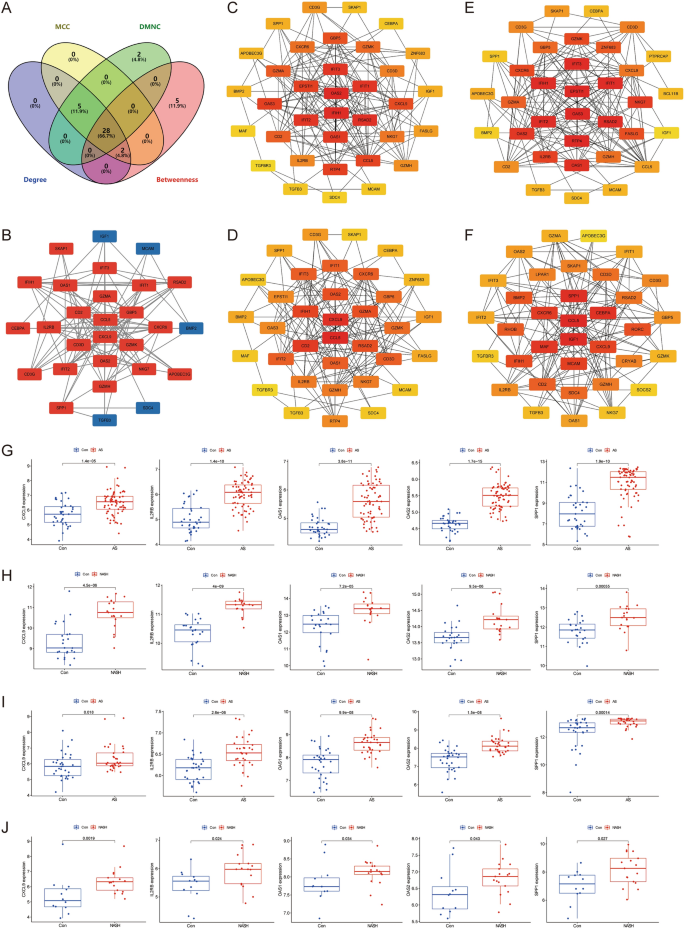

Construction of PPI network

Cytoscape software was utilized to construct a PPI network of 113 common crosstalk genes, which included 66 nodes and 184 edges (Fig. 4D). The top 35 genes ranked by four algorithms (MCC, DMNC, Degree, and Betweenness) were calculated using the “CytoHubba” plugin (Fig. 5C–F). After intersection, 28 candidate Hub genes were obtained (OAS2, IFIH1, RSAD2, IFIT3, IFIT2, IFIT1, OAS1, CCL5, CXCL9, GBP5, GZMA, CD2, GZMK, CXCR6, NKG7, CD3D, IL2RB, GZMH, CD3G, SPP1, IGF1, TGFB3, APOBEC3G, BMP2, SKAP1, MCAM, CEBPA, and SDC4) (Fig. 5A) (Table 2), and a candidate Hub gene PPI network with 28 nodes and 115 edges was constructed (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5

Identification of candidate hub genes. (A) Venn diagram showing the 28 candidate hub genes by four algorithms. (B) The PPI network of candidate hub genes. (C–F) The top 35 candidate hub genes obtained by MCC (C), DMNC (D), Degree (E), and Betweenness (F). (G–J) Identification of hub genes in GES100927 (G), GSE89632 (H), GSE43292 (I), and GSE48452 (J) single gene differential analysis.

Table 2 Screening of candidate Hub genes.

Screening of Hub genes

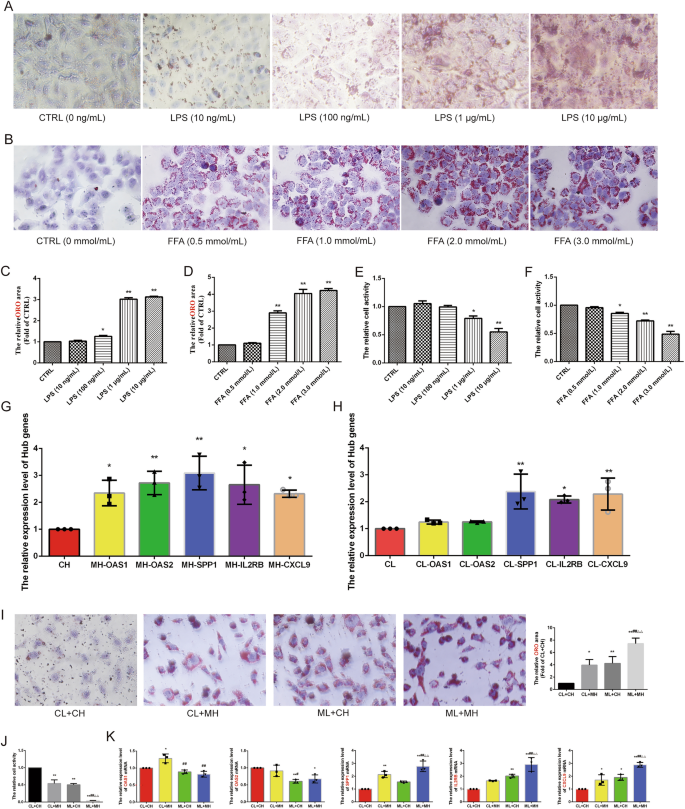

Validation using the GSE43292 and GSE48452 datasets revealed that five genes were significantly upregulated (CXCL9, IL2RB, OAS1, OAS2, and SPP1) in both AS and NASH groups compared to the control group (Fig. 5G–J). In vitro experiments further screened these Hub genes using an AS model induced by LPS (1.0 μg/mL) in HUVECs and a NASH model induced by FFA (2.0 mmol/L) (oleic acid = 2 mmol/L, palmitic acid = 1 mmol/L) in L02 cells. These models exhibited significant lipid accumulation and reduced cell activity (Fig. 6A–F). qRT-PCR results showed that CXCL9 (P < 0.05), IL2RB (P < 0.05), OAS1 (P < 0.05), OAS2 (P < 0.01), and SPP1 (P < 0.01) were significantly up-regulated in the AS model, while CXCL9 (P < 0.01), IL2RB (P < 0.05), and SPP1 (P < 0.01) were significantly up-regulated in the NASH model (Fig. 6G,H). HUVECs and L02 cells co-culture co-morbidity model showed more lipid accumulation and lower cell activity (Fig. 6I,J). Compared with the CL + CH group, the ML + MH group had lower expression levels of OAS2 (P < 0.05) and higher expression levels of SPP1 (P < 0.01), IL2RB (P < 0.01), and CXCL9 (P < 0.01). Compared with the CL + MH and ML + CH groups, the ML + MH group had higher expression levels of SPP1 (P < 0.01) (P < 0.01), IL2RB (P < 0.01) (P < 0.01), and CXCL9 (P < 0.01) (P < 0.01) (Fig. 6K). Therefore, CXCL9, IL2RB, and SPP1 were identified as hub genes.

Figure 6

Experimental validation and screening of Hub genes. (A) The ORO staining of HUVECs was induced by different concentrations of LPS to construct the AS model (n = 5, bar = 500 μm). (B) The ORO staining of L02 cells was induced by different concentrations of FFA to construct the NASH model (n = 5, bar = 500 μm). (C,D) The relative cell area of ORO staining for the AS model (C) and the NASH model (D). (E) CCK8 to detect the relative cell viability of HUVECs induced by different concentrations of LPS. (F) CCK8 to detect the relative cell viability of L02 cells induced by different concentrations of FFA. (G,H) qRT-PCR to detect the relative expression levels of Hub genes in the AS model (G) and the NASH model (H) (n = 3). (I) The ORO staining of the co-morbidity model. (J) The relative cell viability of the co-morbidity model (n = 5, bar = 500 μm). (K) qRT-PCR to detect the relative expression levels of Hub genes in the co-morbidity model (n = 3). *P < 0.05 vs the first group, **P < 0.01 vs the first group, #P < 0.05 vs the CL + MH group, ##P < 0.01 vs the CL + MH group, △P < 0.05 vs the ML + CH group, △△P < 0.01 vs the ML + CH group.

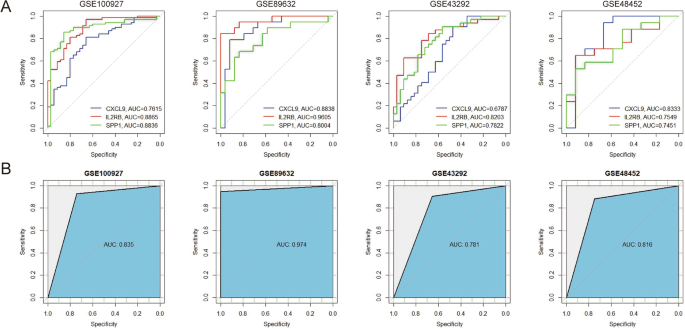

Evaluation of the diagnostic efficacy of Hub genes

ROC curves for these Hub genes across four datasets were generated using the “pROC” R package, and the area under curve (AUC) values for these Hub genes exceeded 0.6, indicating that the diagnostic efficacy of these Hub genes was excellent (Fig. 7A). SVM models were developed for these genes showed AUC values above 0.75, indicating satisfactory combined diagnostic efficacy (Fig. 7B).

Figure 7

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and support vector machine (SVM) models to validate the diagnostic efficacy of hub genes in AS and NASH. (A) ROC curve to validate the diagnostic efficacy of individual hub genes. (B) SVM model to validate the efficacy of combined hub gene diagnosis. The X-axis represents specificity, and the Y-axis represents sensitivity, AUC stands for “rea under the curve”.

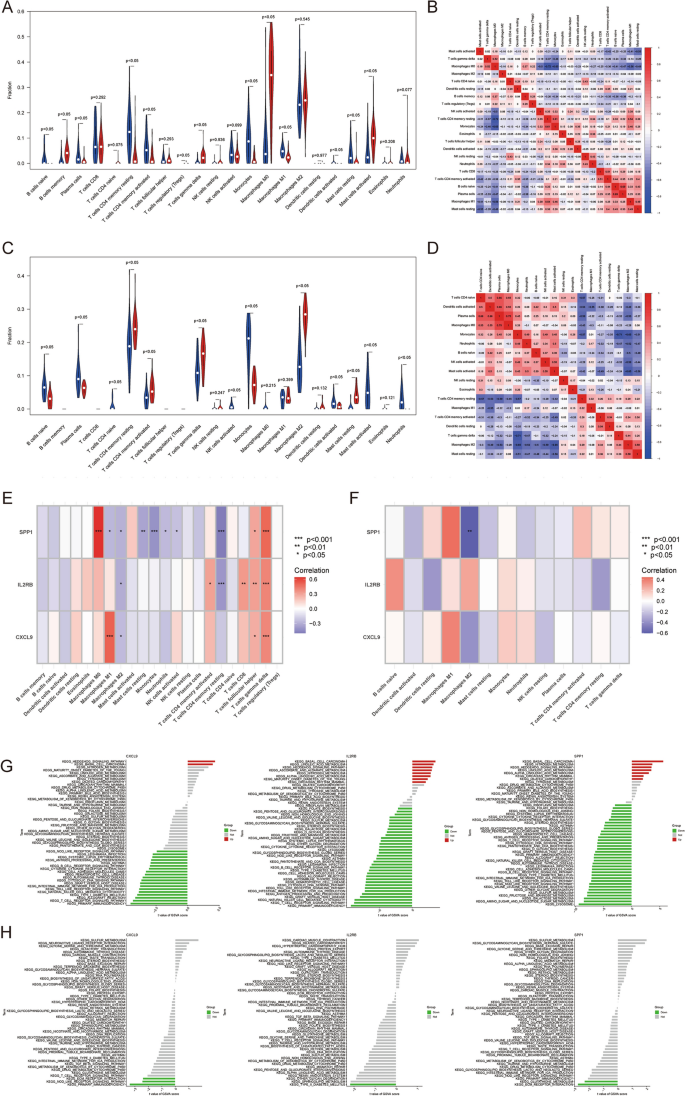

Immune infiltration analysis

To further reveal the immune microenvironment in AS and NASH, specific immune cell types infiltrating into AS and NASH tissues were analyzed using the CIBERSORT method. Among the 22 immune cells studied, the results showed significantly higher levels of memory B cells, γ–δ T cells, M0 macrophages, and activated mast cells in AS (P < 0.05) (Fig. 8A), and further analysis of CIBERSORT scores showed a strong positive correlation of plasma cells with naive B cells, monocytes, and resting memory CD4 T cells, while a strong negative correlation of M0 macrophages with resting memory CD4 T cells and monocytes (Fig. 8B). The levels of resting memory CD4 T cells, activated memory CD4 T cells, γ–δ T cells, M2 macrophages, and resting mast cells were significantly higher in NASH (P < 0.05) (Fig. 8C) and further analysis of CIBERSORT scores showed a strong positive correlation between plasma cells and M0 macrophages, while a strong negative correlation was found between γ–δ T cells and monocytes (Fig. 8D).

Figure 8

Immune infiltration analysis and GSVA. (A,C). Differences in immune infiltration between AS (A) and NASH (C) and control samples. (B,D) Correlation between 22 immune cells in AS (B) and NASH (D). (E,F) Correlation between hub genes and immune cells in AS (E) and NASH (F). (G,H) GSVA analysis of hub genes in AS (G) and NASH (H).

In addition, correlation analyses showed that multiple immune cells were significantly associated with five Hub genes, particularly M0 macrophages, resting memory CD4 T cells, follicular helper T cells, γ–δ T cells in AS, and M2 macrophages in NASH (Fig. 8E,F).

GEVA

To further explore the potential mechanisms of Hub genes in AS and NASH, differences in the enrichment of each Hub gene pathway were analyzed using GSVA. The results showed that CXCL9, IL2RB, and SPP1 were mainly down-regulated in AS and NASH in immune and metabolism-related pathways, especially the metabolism of various fatty acids, the Toll-like receptor signaling pathway, the T cell receptor signaling pathway, and the NOD-like receptor signaling pathway, and up-regulated in some cancer and biosynthesis related pathways, especially basal cell carcinoma, steroid biosynthesis, terpenoid backbone biosynthesis, nitrogen metabolism, sulfur metabolism, Linoleic acid metabolism, and the hedgehog signaling pathway (Fig. 8G,H).

Hub gene–drug interaction

Importing the three Hub genes into the DGIbd database yielded 28 potential drugs, of which 11 were FDA-approved, while no FDA-approved drugs were available for CXCL9. The drugs corresponding to IL2RB are aldesleukin, denileukin diftitox, daclizumab, and basiliximab; and the drugs corresponding to SPP1 are calcitonin, anhydrous tacrolimus, tretinoin, chondroitin sulfates, zoledronic acid anhydrous, pamidronate, and gentamicin. Finally, five potential drugs were screened by literature search for calcitonin, anhydrous tacrolimus, tretinoin, chondroitin sulfates, and zoledronic acid anhydrous.

Construction of common miRNA–mRNA network

There were 30 potential miRNAs for CXCL9, 40 for IL2RB, and 6 for SPP1 obtained by database prediction, of which has-miR-185 regulated CXCL9 and IL2RB, and hsa-miR-335 regulated CXCL9 and SPP1.

Discussion

Several studies have found that cardiovascular risk increases with the severity of fatty liver injury and the degree of fibrosis35,36. Furthermore, AS and NASH share many common risk factors, such as obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia. This suggests that there is an identical pathogenesis between AS and NASH. In the present study, it was found that their shared pathogenesis is associated with biological processes including inflammatory response, immune response, glycolipid metabolism, and copper ion metabolism, which may act through the NOD-like receptor signaling pathway and the JAK-STAT signaling pathway (Fig. 4E–J). The role of inflammation in the co-morbidity pattern of AS and NASH has been validated. NASH is due to chronic inflammatory infiltration of hepatocytes, and AS is due to chronic inflammatory infiltration of the vascular wall. Hepatic secretion of inflammatory molecules, considered pro-atherogenic, may contribute to vascular endothelial dysfunction, resulting in atherosclerosis and CVDs37.

The inflammatory response plays a critical role in the co-morbidity mechanism of AS and NASH. Chronic inflammatory responses in the vascular wall led to endothelial cell damage, vessel wall thickening, and stiffening, which can result in AS formation and plaque development. Lipid accumulation results in prolonged inflammatory infiltration of the liver, leading to the development of hepatic fibrosis. In addition, pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines are secreted during liver inflammation, which may lead to vascular endothelial dysfunction and increase the risk of AS and CVDs37.

The previous immune infiltration analysis revealed disturbances in the immune microenvironment of AS and NASH, particularly involving γ–δ T cells and macrophages. γ–δ T cells primarily reside in epithelial and mucosal layers and play a role in defense against infection by producing cytokines such as IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-17, and Th2 cytokines38,39. The absence of γ–δ T cells, which are the most abundant T cells in AS lesions, reduced neutrophil infiltration and delayed AS lesions development40,41,42,43. γ–δ T cells constitute 3–5% of adult lymphocytes in the liver, a proportion much higher than other tissues44. An increased in γ–δ T17 cells occurs in liver inflammation and fibrosis. Hepatic γ–δ T cells produce IL-17A, which accelerates the development of NAFLD45,46. Mice fed a high-fat diet showed increased hepatic γ–δ T17 cells producing IL-17A, leading to steatohepatitis, liver damage, and impaired glucose metabolism47. Strategies such as deleting, depleting, or interrupting the recruitment of γ–δ T cells have prevented diet-induced steatohepatitis and accelerated resolution48. Hepatic γ–δ T cells also contribute to NASH by bridging innate and adaptive immunity49,50. Thus, the highly expressed γ–δ T cells are a common factor in the pathogenesis of both AS and NASH.

Macrophage infiltration plays a central role in AS and was previously thought to be a late consequence of steatosis. However, recent studies have shown that the activation and infiltration of macrophages are also early initiating event in NASH. Inhibition of macrophage infiltration has been shown to reduce the development of hepatic inflammation and AS, highlighting it as one of the common mechanisms linking AS and NASH51,52.

Copper is an essential trace element involved in oxidative stress and energy metabolism. It has been found that copper levels are closely related to the morbidity and mortality of NASH and atherosclerotic CVDs; thus, abnormal copper metabolism may be one of the mechanisms causing the common pathogenesis of AS and NASH53,54. High serum copper levels accelerate the formation of atherosclerotic plaque by affecting lipid metabolism, oxidative stress, low-density lipoprotein oxidation, and inflammation, thus increasing the risk of atherosclerotic heart disease55,56. In addition, copper ion-oxidized low-density lipoprotein generates intracellular oxidative stress through lipid peroxidation products, induces Tyr phosphorylation and activation of JAK2, STAT1, and STAT3, and participates in the JAK/STAT pathway, which promotes the development of AS and NASH57.

In this study, 28 candidate Hub genes were first obtained after screening for differentially expressed genes between normal individuals and those with AS and NASH. Then, three Hub genes (CXCL9, IL2RB, and SPP1) were confirmed through an external validation set and qRT-PCR verification. The ROC curves and SVM models were used to verify the validity of the diagnostic efficacy. Furthermore, exploring the biological properties of these three Hub genes also explores the common pathogenesis of AS and NASH, potentially offering a new strategy for the early diagnosis of these conditions. SVM is a supervised machine learning algorithm used for binary classification prediction and regression-based attribute value prediction. It is capable of handling high-dimensional data, has strong generalization ability, and is widely used in disease gene screening and drug development. However, SVM has drawbacks, such as its sensitivity to noisy data and its primary applicability to binary classification problems. Future research may focus on constructing multiple models, selecting better and more appropriate models for screening, and improving overall model performance58,59,60.

CXCL9, also known as monokine induced by interferon-γ, plays a role in immune cell migration and inflammatory responses. It is highly expressed in patients with AS and is associated with carotid intima-media thickness and a coronary artery calcification score61,62,63. It may contribute to T lymphocyte recruitment and proliferation at sites of inflammation64,65. CXCL9 expression is also elevated in NAFLD patients and a mouse model of NASH, with the CXCL9 protein detected in hepatocytes and sinusoidal endothelium in areas infiltrated by inflammatory cells66,67. Recent studies suggest that CXCL9 promotes NASH development and progression by activating the p-JNK pathway, promoting Th17 cell proliferation, and disrupting Treg/Th17 cell homeostasis in a mouse model of NASH68. Bioinformatics analyses have consistently shown CXCL9 upregulation in human and animal models of NAFLD and NASH, supporting the findings of the present study69,70. Overall, CXCL9 is recognized as a potential biomarker for AS and NASH, with its elevated mRNA levels potentially indicating early development of both conditions.

IL2RB is a key constituent subunit of the IL-2 cytokine receptor, which plays a central role in IL-2 signaling and is also implicated in the development and progression of AS and NASH71. Activation of IL2RB regulates the proliferation and differentiation of immune cells such as Treg and NK cells72. Treg cells produce high levels of the IL-10 inflammation suppressor to inhibit inflammation, as well as high levels of TGF-β, which regulate macrophage polarization and stabilize AS plaques73,74. However, Treg cells, which are highly expressed in NASH, can accelerate hepatic steatosis during the development of NAFLD and NASH and do not act as modulators of metabolic inflammation but rather enhance it75,76. IL2RB also supports the differentiation of T-lymphocytes towards Th1 and promotes the production of the pro-inflammatory factor interferon-γ, affecting the progression of AS by modulating the inflammatory response77,78. IL-2Rβγ signaling in lymphocytes promotes systemic inflammation and reduces plasma cholesterol in atherosclerotic mice79. Construction of a NASH model in Parma minipigs, continuously fed a high-fat and high-sucrose diet for 23 months, reveals high expression of IL2RB as an inflammatory gene80.

SPP1, also known as osteopontin (OPN), is involved in the inflammatory milieu of AS and is highly expressed in endothelial cells, macrophages, and vascular smooth muscle cells within AS plaques81,82. It is also elevated in AS patients and correlates with the occurrence and severity of coronary artery disease, serving as a marker for monitoring coronary AS severity and predicting cardiovascular event mortality83,84. Overexpression of OPN significantly promotes fatty streak formation in AS mice and inhibits IL-10 production by macrophages85. OPN also increases autophagosome formation, autophagy-related gene expression, and cell death associated with AS development86. SPP1 is closely associated with the development, progression, and prognosis of fatty liver, liver fibrosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma87. Its expressions are significantly elevated in the plasma of NASH patients and correlate with histological features of NASH severity88,89. SPP1 promotes inflammatory responses, cellular activation, proliferation, and migration, and inhibits autophagy in liver disorders. In a porcine model of NASH, SPP1 expression was positively correlated with lipid droplet area and inflammation but decreased when NASH was reversed90. However, a lack of SPP1 exacerbated lipid accumulation, hepatocyte apoptosis, and fibrosis, indicating a complex role in NASH pathogenesis91.

Statins are the primary drugs for preventing cardiovascular disease and constitute the primary class of lipid-lowering drugs for treating AS and NASH. Studies have found that the use of statins significantly reduces the levels of CXCL9, IL2RB, and SPP1, suggesting that statins may exert their effects by targeting these proteins62,92,93,94,95,96.

Finally, the Hub gene was imported into the DGIbd database to obtain 11 FDA-approved drugs, which were further screened through a literature search to find five potential drugs capable of treating AS and NASH, namely, calcitonin, anhydrous tacrolimus, tretinoin, chondroitin sulfates, and zoledronic acid anhydrous. Except for calcitonin, which down-regulated the expression of SPP1, all the identified drugs up-regulated the expression of SPP1/OPN97,98,99,100,101,102.

Calcitonin has been used to prevent experimental immunarteriosclerosis103, which may modulate vascular homeostasis by decreasing lipid levels and adipogenesis in cells104, preventing the increase of calcium influx, and enhancing the permeability of the arterial smooth muscle105. In addition, calcitonin extracted from salmon is more effective in inhibiting gastric emptying, promoting gallbladder relaxation, increasing energy expenditure, and inducing satiety and weight loss. This demonstrates its great therapeutic potential in obesity and NAFLD106.

Tacrolimus reduced AS formation by inhibiting ROS in macrophages and activating the NLRP3 inflammasome, as well as decreasing IL-1β and IL-18 release107. In addition, tacrolimus-eluting stents inhibited neointimal hyperplasia after stent placement via the calcineurin/NFAT/IL-2 signaling pathway108. Tacrolimus also reduced hepatic lipid accumulation and improved the lipid profile in fast-food diet mice by inhibiting the expression of adipogenic factors such as PPAR-γ, SREBP-1, and SCD-1. It also reduced apoptosis and suppressed the level of hepatic fibrosis109.

Tretinoin plays a potential role in the prevention of CVDs, and studies have shown that it can influence the development of AS by regulating various biological processes in immune cells, such as cell proliferation, migration, and phenotypic transformation. It is also involved in the regulation of blood glucose concentration, lipid metabolism, and the inflammatory response, thereby improving AS110. In a study, serum tretinoin concentrations were found to be significantly lower in NASH patients than in healthy subjects111. Tretinoin supplementation significantly improved hepatic steatosis, glucose tolerance, and insulin sensitivity in mice induced by a high-fat diet112.

Chondroitin sulfates (CS) are a class of drugs recommended for the treatment of osteoarthritis, and studies have found that osteoarthritis patients treated with high doses of CS are less likely to develop coronary artery disease113,114. Furthermore, patients with AS have been observed to have lower mortality rates, suggesting that CS may have beneficial cardiovascular effects115. Several studies have suggested that CS may delay the progression of AS lesions by inhibiting inflammation and foam cell formation. This is achieved by decreasing the expression of pro-inflammatory factors (e.g., CRP, IL-6, COX-2, MCP1, TNF-α, and IL-1β), cytokines (e.g., CCL2), and other cell adhesion molecules116,117,118. In addition, CS supplementation was found to improve insulin resistance, liver function, and lipid levels in NAFLD mice by regulating the composition of the intestinal flora119.

Recent clinical studies have shown that zoledronic acid improves the lipid profile of patients, delays the progression of vascular calcification and AS, reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease, and decreases mortality120,121. It may affect the development of AS and NASH by inhibiting the proliferation, adhesion, and migration of vascular smooth muscle cells122, blocking the mevalonate pathway, decreasing hepatic TNF-α and VEGF expression, regulating cholesterol synthesis, and improving the lipid profile. Zoledronic acid also enhances hepatic function and prevents portal hypertension123,124.

MiRNAs, non-coding RNAs of 21–24 nucleotides in length, regulate gene expression by promoting or inhibiting mRNA degradation and translation. miRNAs have been shown to be implicated in the biological processes and pathogenesis of AS and NASH. Several studies have summarized the roles of miRNAs in AS and NASH, and this study, based on multiple miRNA research tools, identified has-miR-185 and hsa-miR-335 as potentially playing significant roles in AS and NASH125,126. It was found that miR-185 could delay the development of AS and NAFLD/NASH by regulating various biological processes, including cell proliferation, migration, and invasion127; enhancing lipid metabolism128,129; inhibiting inflammation and apoptosis130; and affecting insulin resistance131. miR-335 has been shown to inhibit the intrinsic immune response of macrophages, reducing the formation of vulnerable plaques in AS132; improving endothelial function133; and regulating the proliferation and phenotypic switching of smooth muscle cells134, thereby slowing the progression of AS. Additionally, miR-335 influences NAFLD and NASH through the modulation of insulin resistance and has been recognized as a potential diagnostic biomarker for NAFLD135,136,137.

To summarize, this study leverages bioinformatics to identify potential common biomarkers and explore the pathogenesis of AS and NASH. Utilizing multiple topological algorithms, the research underwent external and in vitro experimental validation to screen for hub genes. Subsequently, the diagnostic efficacy of these genes was assessed using SVM modeling and ROC curves. The study further conducted GSVA and immune-infiltration analyses on the identified hub genes. This research is innovative as it explores the connection between AS and NASH, which are linked by similar risk factors and share common pathogenic mechanisms. By employing a co-morbidity pattern, the study utilizes bioinformatics analysis to investigate the interplay between AS and NASH, with a focus on mining potential biomarkers and understanding the shared pathogenesis. This approach, which has not been extensively explored by scholars, offers new insights that can inform the investigation of chronic diseases and patterns of co-morbidity. Then this study constructed an AS foam cell model, a NASH hepatocyte steatosis model, and a co-morbid in vitro model of AS and NASH to verify the expression levels of candidate hub genes. It culminated in the identification of potential drugs for the treatment of both AS and NASH based on these hub genes, which holds significant implications for clinical guidance. This research is both promising and innovative, delving into the investigation of biomarkers and pathogenesis within the context of co-morbid AS and NASH. The efficacy of the hub genes was validated using SVM modeling, a method that adds rigor to our findings. Additionally, the study offers a foundation for other scholars to explore the complexities of co-morbid conditions.

However, this study still has some limitations. Firstly, for the dual-disease bioinformatics analysis, the database did not contain data from patients with AS and NASH co-morbidities, which may result in the absence of some potential diagnostic genes. Secondly, this study was validated using human cell lines for in vitro experiments, and a co-culture co-morbidity model was constructed for further validation, but it lacked further validation in animal and human tissues. In addition, this study used SVM models for Hub gene screening, and constructing multiple models and then screening them appeared to have different results. Lastly, although the literature search identified five potential therapeutic drugs and two related miRNAs, their specific mechanisms and efficacy need to be further investigated.

Conclusions

AS and NASH share several common pathogenetic mechanisms related to inflammatory response, immune response, glycolipid metabolism, and copper ion metabolism. Three hub genes (CXCL9, IL2RB, and SPP1) serve as potential biomarkers for the diagnosis of the comorbidities of AS and NASH, either independently or in combination, with a certain degree of accuracy and specificity. Five potential drugs for the treatment of AS and NASH, namely, calcitonin, anhydrous tacrolimus, tretinoin, chondroitin sulfates, and zoledronic acid anhydrous.

Data availability

The following information was supplied regarding data availability: Data is available at Supplementary Material A, B and NCBI GEO: GSE100927, GSE89632, GES43292, and GSE48452. Additionally, any analytic technology-related questions can be directly contacted by the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

AS:

Atherosclerosis

AUC:

Area under curve

BP:

Biological process

CC:

Cellular component

CS:

Chondroitin sulfates

CVDs:

Cardiovascular diseases

DEGs:

Differentially expressed genes

FDA:

Food and Drug Administration

FFA:

Free fatty acid

GEO:

Gene Expression Omnibus

GO:

Gene Ontology

GSEA:

Gene set enrichment analysis

GSVA:

Gene set variation analysis

HUVECs:

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells

KEGG:

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

LPS:

Lipopolysaccharide

MF:

Molecular function

NAFLD:

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

NASH:

Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

OPN:

Osteopontin

ORO:

Oil Red O

PPI:

Protein–protein interaction

ROC:

Receiver operating characteristic

qRT-PCR:

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

SVM:

Support vector machine

WGCNA:

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis

References

- Chalasani, N. et al. The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 67(1), 328–357 (2018).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Younossi, Z. et al. Global burden of NAFLD and NASH: Trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 15(1), 11–20 (2018).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Ekstedt, M. et al. Fibrosis stage is the strongest predictor for disease-specific mortality in NAFLD after up to 33 years of follow-up. Hepatology 61(5), 1547–1554 (2015).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Singh, S. et al. Fibrosis progression in nonalcoholic fatty liver vs nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of paired-biopsy studies. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 13(4), 643–654 (2015).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Cassidy, S. & Syed, B. A. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) drugs market. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 15(11), 745–746 (2016).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Wong, R. J. et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is the second leading etiology of liver disease among adults awaiting liver transplantation in the United States. Gastroenterology 148(3), 547–555 (2015).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Beverly, J. K. & Budoff, M. J. Atherosclerosis: Pathophysiology of insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, hyperlipidemia, and inflammation. J. Diabetes 12(2), 102–104 (2020).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Virani, S. S. et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2020 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 141(9), e139–e596 (2020).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Bergström, G. et al. Prevalence of subclinical coronary artery atherosclerosis in the general population. Circulation 144(12), 916–929 (2021).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Kim, K., Ginsberg, H. N. & Choi, S. H. New, novel lipid-lowering agents for reducing cardiovascular risk: Beyond statins. Diabetes Metab. J. 46(4), 517–532 (2022).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - van den Hoek, A. M. et al. Unraveling the transcriptional dynamics of NASH pathogenesis affecting atherosclerosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23(15), 8229 (2022).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Gutiérrez-Cuevas, J., Santos, A. & Armendariz-Borunda, J. Pathophysiological molecular mechanisms of obesity: A link between MAFLD and NASH with cardiovascular diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22(21), 11629 (2021).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Spahillari, A. et al. The association of lean and fat mass with all-cause mortality in older adults: The Cardiovascular Health Study. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 26(11), 1039–1047 (2016).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Wong, C. R. & Lim, J. K. The association between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and cardiovascular disease outcomes. Clin. Liver Dis. (Hoboken) 12(2), 39–44 (2018).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Vanni, E., Marengo, A., Mezzabotta, L. & Bugianesi, E. Systemic complications of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: When the liver is not an innocent bystander. Semin. Liver Dis. 35(3), 236–249 (2015).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Zhou, J. H., Cai, J. J., She, Z. G. & Li, H. L. Noninvasive evaluation of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Current evidence and practice. World J. Gastroenterol. 25(11), 1307–1326 (2019).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Steenman, M. et al. Identification of genomic differences among peripheral arterial beds in atherosclerotic and healthy arteries. Sci. Rep. 8(1), 3940 (2018).

Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Arendt, B. M. et al. Altered hepatic gene expression in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with lower hepatic n-3 and n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Hepatology 61(5), 1565–1578 (2015).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Langfelder, P. & Horvath, S. WGCNA: An R package for weighted correlation network analysis. BMC Bioinform. 9, 559 (2008).

Article Google Scholar - Ritchie, M. E. et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 43(7), e47 (2015).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Sherman, B. T. et al. DAVID: A web server for functional enrichment analysis and functional annotation of gene lists (2021 update). Nucleic Acids Res. 50(W1), W216–W221 (2022).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Kanehisa, M., Furumichi, M., Sato, Y., Kawashima, M. & Ishiguro-Watanabe, M. KEGG for taxonomy-based analysis of pathways and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 51(D1), D587–D592 (2023).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Szklarczyk, D. et al. The STRING database in 2021: Customizable protein-protein networks, and functional characterization of user-uploaded gene/measurement sets. Nucleic Acids Res. 49(D1), D605–D612 (2021).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Chin, C. H. et al. cytoHubba: Identifying hub objects and sub-networks from complex interactome. BMC Syst. Biol. 8(Suppl 4), S11 (2014).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Ayari, H. & Bricca, G. Identification of two genes potentially associated in iron-heme homeostasis in human carotid plaque using microarray analysis. J. Biosci. 38(2), 311–315 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Ahrens, M. et al. DNA methylation analysis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease suggests distinct disease-specific and remodeling signatures after bariatric surgery. Cell Metab. 18(2), 296–302 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Robin, X. et al. pROC: An open-source package for R and S+ to analyze and compare ROC curves. BMC Bioinform. 12, 77 (2011).

Article Google Scholar - Newman, A. M. et al. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat. Methods 12(5), 453–457 (2015).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Hu, K. Become competent within one day in generating boxplots and violin plots for a novice without prior R experience. Methods Protoc. 3(4), 64 (2020).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Subramanian, A. et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102(43), 15545–15550 (2005).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Hänzelmann, S., Castelo, R. & Guinney, J. GSVA: Gene set variation analysis for microarray and RNA-seq data. BMC Bioinform. 14, 7 (2013).

Article Google Scholar - Huang, H. Y. et al. miRTarBase update 2022: An informative resource for experimentally validated miRNA-target interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 50(D1), D222–D230 (2022).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Huang, L., Zhang, L. & Chen, X. Updated review of advances in microRNAs and complex diseases: Experimental results, databases, webservers and data fusion. Brief. Bioinform. 23(6), bbac397 (2022).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Li, J. et al. Integrating transcriptomics and network pharmacology to reveal the mechanisms of total Rhizoma Coptidis alkaloids against nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. J. Ethnopharmacol. 322, 117600 (2023).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Tutunchi, H. et al. The association of the steatosis severity, NAFLD fibrosis score and FIB-4 index with atherogenic dyslipidaemia in adult patients with NAFLD: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 75(6), e14131 (2021).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Turecký, L., Kupčová, V., Urfinová, M., Repiský, M. & Uhlíková, E. Serum butyrylcholinesterase/HDL-cholesterol ratio and atherogenic index of plasma in patients with fatty liver disease. Vnitr Lek. 67(E-2), 4–8 (2021).

PubMed Google Scholar - Nasiri-Ansari, N. et al. Endothelial cell dysfunction and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): A concise review. Cells 11(16), 2511 (2022).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Born, W. K., Reardon, C. L. & O’Brien, R. L. The function of gammadelta T cells in innate immunity. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 18(1), 31–38 (2006).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Bonneville, M., O’Brien, R. L. & Born, W. K. Gammadelta T cell effector functions: A blend of innate programming and acquired plasticity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 10(7), 467–478 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Maniar, A. et al. Human gammadelta T lymphocytes induce robust NK cell-mediated antitumor cytotoxicity through CD137 engagement. Blood 116(10), 1726–1733 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Cheng, H. Y., Wu, R. & Hedrick, C. C. Gammadelta (γδ) T lymphocytes do not impact the development of early atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 234(2), 265–269 (2014).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Kyaw, T. et al. Cytotoxic lymphocytes and atherosclerosis: Significance, mechanisms and therapeutic challenges. Br. J. Pharmacol. 174(22), 3956–3972 (2017).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Vu, D. M. et al. γδT cells are prevalent in the proximal aorta and drive nascent atherosclerotic lesion progression and neutrophilia in hypercholesterolemic mice. PLoS One 9(10), e109416 (2014).

Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Racanelli, V. & Rehermann, B. The liver as an immunological organ. Hepatology 43(2 Suppl 1), S54–S62 (2006).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Hammerich, L. et al. Chemokine receptor CCR6-dependent accumulation of γδ T cells in injured liver restricts hepatic inflammation and fibrosis. Hepatology 59(2), 630–642 (2014).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Hammerich, L. & Tacke, F. Role of gamma-delta T cells in liver inflammation and fibrosis. World J. Gastrointest. Pathophysiol. 5(2), 107–113 (2014).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Li, F. et al. The microbiota maintain homeostasis of liver-resident γδT-17 cells in a lipid antigen/CD1d-dependent manner. Nat. Commun. 7, 13839 (2017).

Article ADS PubMed Google Scholar - Torres-Hernandez, A. et al. γδ T cells promote steatohepatitis by orchestrating innate and adaptive immune programming. Hepatology 71(2), 477–494 (2020).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Chen, Y. & Tian, Z. Roles of hepatic innate and innate-like lymphocytes in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Front. Immunol. 11, 1500 (2020).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Wang, X. & Gao, B. γδT cells and CD1d, novel immune players in alcoholic and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis?. Hepatology 71(2), 408–410 (2020).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Bieghs, V., Rensen, P. C., Hofker, M. H. & Shiri-Sverdlov, R. NASH and atherosclerosis are two aspects of a shared disease: Central role for macrophages. Atherosclerosis 220(2), 287–293 (2012).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Wang, Y. et al. Exendin-4 decreases liver inflammation and atherosclerosis development simultaneously by reducing macrophage infiltration. Br. J. Pharmacol. 171(3), 723–734 (2014).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Zhang, H. et al. Lower serum copper concentrations are associated with higher prevalence of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: A matched case-control study. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 34(8), 838–843 (2022).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Kunutsor, S. K., Dey, R. S. & Laukkanen, J. A. Circulating serum copper is associated with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, but not venous thromboembolism: A prospective cohort study. Pulse (Basel) 9(3–4), 109–115 (2021).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Wang, D. et al. The molecular mechanisms of cuproptosis and its relevance to cardiovascular disease. Biomed. Pharmacother. 163, 114830 (2023).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Chen, C. et al. Copper exposure association with prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and insulin resistance among US adults (NHANES 2011–2014). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 218, 112295 (2021).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Mazière, C., Conte, M. A. & Mazière, J. C. Activation of JAK2 by the oxidative stress generated with oxidized low-density lipoprotein. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 31(11), 1334–1340 (2001).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Huang, L., Zhang, L. & Chen, X. Updated review of advances in microRNAs and complex diseases: Taxonomy, trends and challenges of computational models. Brief. Bioinform. 23(5), bbac358 (2022).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Huang, L., Zhang, L. & Chen, X. Updated review of advances in microRNAs and complex diseases: Towards systematic evaluation of computational models. Brief. Bioinform. 23(6), bbac407 (2022).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Maltarollo, V. G., Kronenberger, T., Espinoza, G. Z., Oliveira, P. R. & Honorio, K. M. Advances with support vector machines for novel drug discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 14(1), 23–33 (2019).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Yu, H. T. et al. Serum monokine induced by gamma interferon as a novel biomarker for coronary artery calcification in humans. Coron. Artery Dis. 26(4), 317–321 (2015).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Yu, H. T., Lee, J., Shin, E. C. & Park, S. Significant association between serum monokine induced by gamma interferon and carotid intima media thickness. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 22(8), 816–822 (2015).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Liang, Y. et al. Serum monokine induced by gamma interferon is associated with severity of coronary artery disease. Int. Heart J. 58(1), 24–29 (2017).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Xie, J. H. et al. Antibody-mediated blockade of the CXCR3 chemokine receptor results in diminished recruitment of T helper 1 cells into sites of inflammation. J. Leukoc. Biol. 73(6), 771–780 (2003).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Tsubaki, T. et al. Accumulation of plasma cells expressing CXCR3 in the synovial sublining regions of early rheumatoid arthritis in association with production of Mig/CXCL9 by synovial fibroblasts. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 141(2), 363–371 (2005).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Ullah, A. et al. A narrative review: CXC chemokines influence immune surveillance in obesity and obesity-related diseases: Type 2 diabetes and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 24, 611–631 (2023).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Semba, T. et al. The FLS (fatty liver Shionogi) mouse reveals local expressions of lipocalin-2, CXCL1 and CXCL9 in the liver with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. BMC Gastroenterol. 13, 120 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Li, L. et al. MIG/CXCL9 exacerbates the progression of metabolic-associated fatty liver disease by disrupting Treg/Th17 balance. Exp. Cell Res. 407(2), 112801 (2021).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Zhu, M. et al. Qianggan extract improved nonalcoholic steatohepatitis by modulating lncRNA/circRNA immune ceRNA networks. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 19(1), 156 (2019).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Wang, W. et al. SPP1 and CXCL9 promote non-alcoholic steatohepatitis progression based on bioinformatics analysis and experimental studies. Front. Med. (Lausanne) 9, 862278 (2022).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Zhao, T. X., Newland, S. A. & Mallat, Z. 2019 ATVB plenary lecture: Interleukin-2 therapy in cardiovascular disease: The potential to regulate innate and adaptive immunity. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 40(4), 853–864 (2020).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Kuan, R., Agrawal, D. K. & Thankam, F. G. Treg cells in atherosclerosis. Mol. Biol. Rep. 48(5), 4897–4910 (2021).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Sharma, M. et al. Regulatory T cells license macrophage pro-resolving functions during atherosclerosis regression. Circ. Res. 127(3), 335–353 (2020).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Ou, H. X. et al. Regulatory T cells as a new therapeutic target for atherosclerosis. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 39(8), 1249–1258 (2018).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Zhang, C. Y., Liu, S. & Yang, M. Regulatory T cells and their associated factors in hepatocellular carcinoma development and therapy. World J. Gastroenterol. 28(27), 3346–3358 (2022).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Dywicki, J. et al. The detrimental role of regulatory T cells in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatol. Commun. 6(2), 320–333 (2022).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Zhou, J., Zhang, Y. & Zhuang, Q. IL2RB affects Th1/Th2 and Th17 responses of peripheral blood mononuclear cells from septic patients. Allergol. Immunopathol. (Madr) 51(3), 1–7 (2023).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Yuan, X., Dong, Y., Tsurushita, N., Tso, J. Y. & Fu, W. CD122 blockade restores immunological tolerance in autoimmune type 1 diabetes via multiple mechanisms. JCI Insight 3(2), e96600 (2018).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Mulholland, M. et al. IL-2Rβγ signalling in lymphocytes promotes systemic inflammation and reduces plasma cholesterol in atherosclerotic mice. Atherosclerosis 326, 1–10 (2021).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Xia, J. et al. Transcriptome analysis on the inflammatory cell infiltration of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in bama minipigs induced by a long-term high-fat, high-sucrose diet. PLoS One 9(11), e113724 (2014).

Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Wolak, T. Osteopontin—A multi-modal marker and mediator in atherosclerotic vascular disease. Atherosclerosis 236(2), 327–337 (2014).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - O’Brien, E. R. et al. Osteopontin is synthesized by macrophage, smooth muscle, and endothelial cells in primary and restenotic human coronary atherosclerotic plaques. Arterioscler. Thromb. 14(10), 1648–1656 (1994).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Ohmori, R. et al. Plasma osteopontin levels are associated with the presence and extent of coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis 170(2), 333–337 (2003).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Momiyama, Y. et al. Associations between plasma osteopontin levels and the severities of coronary and aortic atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 210(2), 668–670 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Isoda, K. et al. Osteopontin transgenic mice fed a high-cholesterol diet develop early fatty-streak lesions. Circulation 107(5), 679–681 (2003).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Zheng, Y. H. et al. Osteopontin stimulates autophagy via integrin/CD44 and p38 MAPK signaling pathways in vascular smooth muscle cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 227(1), 127–135 (2012).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Wang, G. et al. Comparative analysis of gene expression profiles of OPN signaling pathway in four kinds of liver diseases. J. Genet. 95(3), 741–750 (2016).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Yilmaz, Y. et al. Serum osteopontin levels as a predictor of portal inflammation in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig. Liver Dis. 45(1), 58–62 (2013).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Arendt, B. M. et al. Cancer-related gene expression is associated with disease severity and modifiable lifestyle factors in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Nutrition 62, 100–107 (2019).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Herrera-Marcos, L. V. et al. Hepatic galectin-3 is associated with lipid droplet area in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in a new swine model. Sci. Rep. 12(1), 1024 (2022).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Nardo, A. D. et al. Impact of osteopontin on the development of non-alcoholic liver disease and related hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int. 40(7), 1620–1633 (2020).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Tuomisto, T. T. et al. Simvastatin has an anti-inflammatory effect on macrophages via upregulation of an atheroprotective transcription factor, Kruppel-like factor 2. Cardiovasc. Res. 78(1), 175–184 (2008).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Maneechotesuwan, K., Kasetsinsombat, K., Wongkajornsilp, A. & Barnes, P. J. Simvastatin up-regulates adenosine deaminase and suppresses osteopontin expression in COPD patients through an IL-13-dependent mechanism. Respir. Res. 17(1), 104 (2016).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Kadoglou, N. P. et al. Aggressive lipid-lowering is more effective than moderate lipid-lowering treatment in carotid plaque stabilization. J. Vasc. Surg. 51(1), 114–121 (2010).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Goebel, J. et al. Atorvastatin affects interleukin-2 signaling by altering the lipid raft enrichment of the interleukin-2 receptor beta chain. J. Investig. Med. 53(6), 322–328 (2005).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Ferreira, G. A., Teixeira, A. L. & Sato, E. I. Atorvastatin therapy reduces interferon-regulated chemokine CXCL9 plasma levels in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 19(8), 927–934 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Kaji, H. et al. Calcitonin inhibits osteopontin mRNA expression in isolated rabbit osteoclasts. Endocrinology 135(1), 484–487 (1994).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Khanna, A. Tacrolimus and cyclosporinein vitro and in vivo induce osteopontin mRNA and protein expression in renal tissues. Nephron Exp. Nephrol. 101(4), e119–e126 (2005).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Weng, Z. et al. All-trans retinoic acid promotes osteogenic differentiation and bone consolidation in a rat distraction osteogenesis model. Calcif. Tissue Int. 104(3), 320–330 (2019).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Peal, D. S., Burns, C. G., Macrae, C. A. & Milan, D. Chondroitin sulfate expression is required for cardiac atrioventricular canal formation. Dev. Dyn. 238(12), 3103–3110 (2009).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Mergoni, G. et al. The effect of laser therapy on the expression of osteocalcin and osteopontin after tooth extraction in rats treated with zoledronate and dexamethasone. Support. Care Cancer 24(2), 807–813 (2016).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Katz, J. et al. Genetic polymorphisms and other risk factors associated with bisphosphonate induced osteonecrosis of the jaw. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 40(6), 605–611 (2011).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Robert, L., Brechemier, D., Godeau, G., Labat, M. L. & Milhaud, G. Prevention of experimental immunarteriosclerosis by calcitonin. Biochem. Pharmacol. 26(22), 2129–2135 (1977).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Nishizawa, Y. et al. Calcium/calmodulin-mediated action of calcitonin on lipid metabolism in rats. J. Clin. Investig. 82(4), 1165–1172 (1988).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Jacob, M. P. et al. Prevention by calcitonin of the pathological modifications of the rabbit arterial wall induced by immunization with elastin peptides: Effect on vascular smooth muscle permeability to ions. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 46(3), 345–356 (1987).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Mathiesen, D. S., Lund, A., Vilsbøll, T., Knop, F. K. & Bagger, J. I. Amylin and calcitonin: Potential therapeutic strategies to reduce body weight and liver fat. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 11, 617400 (2020).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Li, X., Shang, X. & Sun, L. Tacrolimus reduces atherosclerotic plaque formation in ApoE(−/−) mice by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammatory corpuscles. Exp. Ther. Med. 19(2), 1393–1399 (2020).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Hamada, N. et al. Tacrolimus-eluting stent inhibits neointimal hyperplasia via calcineurin/NFAT signaling in porcine coronary artery model. Atherosclerosis 208(1), 97–103 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Love, S., Mudasir, M. A., Bhardwaj, S. C., Singh, G. & Tasduq, S. A. Long-term administration of tacrolimus and everolimus prevents high cholesterol-high fructose-induced steatosis in C57BL/6J mice by inhibiting de-novo lipogenesis. Oncotarget 8(69), 113403–113417 (2017).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Deng, Q. & Chen, J. Potential therapeutic effect of all-trans retinoic acid on atherosclerosis. Biomolecules 12(7), 869 (2022).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Liu, Y. et al. Association of serum retinoic acid with hepatic steatosis and liver injury in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 102(1), 130–137 (2015).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Geng, C. et al. Retinoic acid ameliorates high-fat diet-induced liver steatosis through sirt1. Sci. China Life Sci. 60(11), 1234–1241 (2017).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Morrison, L. M. Response of ischemic heart disease to chondroitin sulfate-A. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 17(10), 913–923 (1969).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Morrison, L. M. & Enrick, N. Coronary heart disease: Reduction of death rate by chondroitin sulfate A. Angiology 24(5), 269–287 (1973).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Nakazawa, K. & Murata, K. Comparative study of the effects of chondroitin sulfate isomers on atherosclerotic subjects. Z. Alternsforsch. 34(2), 153–159 (1979).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Herrero-Beaumont, G. et al. Effect of chondroitin sulphate in a rabbit model of atherosclerosis aggravated by chronic arthritis. Br. J. Pharmacol. 154(4), 843–851 (2008).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Melgar-Lesmes, P. et al. Chondroitin sulphate attenuates atherosclerosis in ApoE knockout mice involving cellular regulation of the inflammatory response. Thromb. Haemost. 118(7), 1329–1339 (2018).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Melgar-Lesmes, P. et al. Treatment with chondroitin sulfate to modulate inflammation and atherogenesis in obesity. Atherosclerosis 245, 82–87 (2016).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Chen, L. et al. Chondroitin sulfate stimulates the secretion of H(2)S by Desulfovibrio to improve insulin sensitivity in NAFLD mice. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 213, 631–638 (2022).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Gozzetti, A. et al. The effects of zoledronic acid on serum lipids in multiple myeloma patients. Calcif. Tissue Int. 82(4), 258–262 (2008).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Billington, E. O. & Reid, I. R. Benefits of bisphosphonate therapy: Beyond the skeleton. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 18(5), 587–596 (2020).

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Wu, L. et al. Zoledronate inhibits the proliferation, adhesion and migration of vascular smooth muscle cells. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 602(1), 124–131 (2009).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Lo Presti, E., D’Orsi, L. & De Gaetano, A. A mathematical model of in vitro cellular uptake of zoledronic acid and isopentenyl pyrophosphate accumulation. Pharmaceutics 14(6), 1262 (2022).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Mohamed, R. H., Tarek, M., Hamam, G. G. & Ezzat, S. F. Zoledronic acid prevents the hepatic changes associated with high fat diet in rats; The potential role of mevalonic acid pathway in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 858, 172469 (2019).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Toba, H., Cortez, D., Lindsey, M. L. & Chilton, R. J. Applications of miRNA technology for atherosclerosis. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 16(2), 386 (2014).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Hochreuter, M. Y., Dall, M., Treebak, J. T. & Barrès, R. MicroRNAs in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Progress and perspectives. Mol. Metab. 65, 101581 (2022).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Fang, M. et al. miR-185 silencing promotes the progression of atherosclerosis via targeting stromal interaction molecule 1. Cell Cycle 18(6–7), 682–695 (2019).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Tan, W. et al. The elevation of miR-185-5p alleviates high-fat diet-induced atherosclerosis and lipid accumulation in vivo and in vitro via SREBP2 activation. Aging (Albany NY) 14(4), 1729–1742 (2022).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Yang, M. et al. Identification of miR-185 as a regulator of de novo cholesterol biosynthesis and low density lipoprotein uptake. J. Lipid Res. 55(2), 226–238 (2014).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Xi, X., Zheng, X., Zhang, R. & Zeng, L. Upregulation of circFOXP1 attenuates inflammation and apoptosis induced by ox-LDL in human umbilical vein endothelial cells by regulating the miR-185-5p/BCL-2 axis. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 100(11), 1045–1054 (2022).

Article CAS Google Scholar - Wang, X. C., Zhan, X. R., Li, X. Y., Yu, J. J. & Liu, X. M. MicroRNA-185 regulates expression of lipid metabolism genes and improves insulin sensitivity in mice with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 20(47), 17914–17923 (2014).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Sun, D., Ma, T., Zhang, Y., Zhang, F. & Cui, B. Overexpressed miR-335-5p reduces atherosclerotic vulnerable plaque formation in acute coronary syndrome. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 35(2), e23608 (2021).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Liu, Y. et al. H2O2 down-regulates SIRT7’s protective role of endothelial premature dysfunction via microRNA-335-5p. Biosci. Rep. 42(5), BSR20211775 (2022).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Ma, R. et al. miR-335-5p regulates the proliferation, migration and phenotypic switching of vascular smooth muscle cells in aortic dissection by directly regulating SP1. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. (Shanghai) 54(7), 961–973 (2022).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Vienberg, S., Geiger, J., Madsen, S. & Dalgaard, L. T. MicroRNAs in metabolism. Acta Physiol. (Oxf.) 219(2), 346–361 (2017).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Zhang, J. W. & Pan, H. T. microRNA profiles of serum exosomes derived from children with nonalcoholic fatty liver. Genes Genomics 44(7), 879–888 (2022).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Zhang, Y. et al. Identification and study of differentially expressed miRNAs in aged NAFLD rats based on high-throughput sequencing. Ann. Hepatol. 19(3), 302–312 (2020).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Funding

Science and Technology Research Project of Education Department of Liaoning Province (No. L202048), Youth Project of Basic Scientific Research Project of Education Department of Liaoning Province (No. LJKQZ2021064); Liaoning Provincial Natural Science Foundation Joint Fund (No. 1700141103037).

Author information

Author notes

- These authors contributed equally: Xize Wu, Changbin Yuan and Jiaxiang Pan.

Authors and Affiliations

- Liaoning University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, No. 79 Chongshan East Road, Huanggu District, Shenyang, 110847, Liaoning, China

Xize Wu, Changbin Yuan, Yi Zhou, Xue Pan, Jian Kang & Lihong Gong - Nantong Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Nantong Hospital Affiliated to Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine, Nantong, 226000, Jiangsu, China

Xize Wu & Lihong Ren - The Affiliated Hospital of Liaoning University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Shenyang, 110032, Liaoning, China

Jiaxiang Pan, Lihong Gong & Yue Li - Liaoning Provincial Key Laboratory of TCM Geriatric Cardio-Cerebrovascular Diseases, Shenyang, 110847, Liaoning, China

Lihong Gong & Yue Li - Dazhou Vocational College of Chinese Medicine, Dazhou, 635000, Sichuan, China

Xue Pan

Authors

- Xize Wu

- Changbin Yuan

- Jiaxiang Pan

- Yi Zhou

- Xue Pan

- Jian Kang

- Lihong Ren

- Lihong Gong

- Yue Li

Contributions

Xize Wu, Changbin Yuan, and Jiaxiang Pan: designed the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the first draft, contributed equally to the work. Yi Zhou, Xue Pan, and Jian Kang: revised the manuscript and performed in vitro experiments. Lihong Ren, Lihong Gong, and Yue Li: conceptualization, funding acquisition, and supervision. All the authors have read and approved the final manuscript prior to submission.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence toLihong Ren, Lihong Gong or Yue Li.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, X., Yuan, C., Pan, J. et al. CXCL9, IL2RB, and SPP1, potential diagnostic biomarkers in the co-morbidity pattern of atherosclerosis and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis.Sci Rep 14, 16364 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-66287-4

- Received: 02 April 2024

- Accepted: 01 July 2024

- Published: 16 July 2024

- Version of record: 16 July 2024

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-66287-4