NF-κB and IKK as therapeutic targets in cancer (original) (raw)

- Review

- Published: 17 February 2006

Cell Death & Differentiation volume 13, pages 738–747 (2006)Cite this article

- 5957 Accesses

- 377 Citations

- 6 Altmetric

- Metrics details

Abstract

The transcription factor NF-_κ_B and associated regulatory factors (including I_κ_B kinase subunits and the I_κ_B family member Bcl-3) are strongly implicated in a variety of hematologic and solid tumor malignancies. A role for NF-_κ_B in cancer cells appears to involve regulation of cell proliferation, control of apoptosis, promotion of angiogenesis, and stimulation of invasion/metastasis. Consistent with a role for NF-_κ_B in oncogenesis are observations that inhibition of NF-_κ_B alone or in combination with cancer therapies leads to tumor cell death or growth inhibition. However, other experimental data indicate that NF-_κ_B can play a tumor suppressor role in certain settings and that it can be important in promoting an apoptotic signal downstream of certain cancer therapy regimens. In order to appropriately move NF-_κ_B inhibitors in the clinic, thorough approaches must be initiated to determine the molecular mechanisms that dictate the complexity of oncologic and therapeutic outcomes that are controlled by NF-_κ_B.

Similar content being viewed by others

NF-κB Family and Control by I_κ_B Kinase Signaling

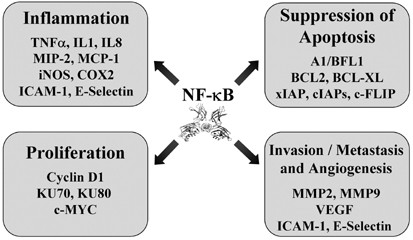

The mammalian NF-_κ_B family of proteins contains the RelA/p65, NF-_κ_B1, NF-_κ_B2, c-Rel, and RelB subunits, which can form a variety of hetero- and homodimers to differentially control gene expression downstream of signals elicited by cytokines, bacterial products, viral expression, growth factors, and stress stimuli.1 Negative regulation of NF-_κ_B is controlled primarily through interactions with the I_κ_B family of proteins, which prevent DNA binding and promote cytoplasmic accumulation of the interacting dimeric complex. Contrary to the normal inhibitory roles for the classical forms of I_κ_B, the Bcl-3 protein can function to regulate gene expression through interactions with the NF-_κ_B1 and NF-_κ_B2 subunits. Positive regulation of NF-_κ_B is controlled through the activity of the I_κ_B kinase (IKK) complex, which phosphorylates I_κ_B proteins leading to their ubiquitination and subsequent proteasome-dependent degradation, leading to the nuclear accumulation of the released NF-_κ_B complexes. In the nucleus, NF-_κ_B complexes bind to target DNA sequences and regulate the expression of genes involved in the immune response, cell growth control, and the regulation of cell survival.1 Cancer relevant, NF-_κ_B-dependent genes include those encoding cytokines, chemokines, cyclin D1, matrix metalloproteinases, and antiapoptotic proteins such as Bcl-xL (Figure 1). As described below, NF-_κ_B and IKK proteins are associated with oncogenesis and cancer therapy responses through a complex set of regulatory pathways.

Figure 1

Representation of NF-_κ_B-dependent genes involved in different aspects of oncogenesis. Target genes are included with the relevant oncogenic process. See text for a description

Common Mechanisms Associated with Human Cancer

Human cancer is a highly diverse and complex disease based on multiple etiologies, multiple cell targets, and distinct developmental stages. Additionally, cancer cells often exhibit genomic instability, which contributes to enhanced disease complexity and therapeutic outcome. However, it has been proposed that cancer cells share common features that override normal controls on proliferation and homeostasis.2 Most of these shared properties are intrinsic to the cancer cells themselves but others are derived from signals that originate from the surrounding tumor microenvironment. Properties that are held in common by advanced cancer cells and that drive malignant growth include strong resistance to growth inhibitory signals, self-sufficiency in growth, resistance to apoptosis, extended replication potential, enhanced angiogenic potential, and the ability to invade local tissue and to metastasize to distant sites.2

Autonomous cell growth can be provided by dysregulated expression of growth factors or growth factor receptors, leading to uncontrolled cell proliferation. Thus, a fairly common mechanism in cancer is the upregulation of expression of members of the epidermal growth factor receptor family such as EGF receptor or Her2/ErbB2. Furthermore, certain cancer cells produce growth factors such as PDGF and TGF_α,_ which can promote cell proliferation in an autocrine manner.2 Mutations in proteins that regulate cell proliferation are also relatively common in cancers. For example, mutations in Ras alleles drive cell proliferation through chronic stimulation of signal transduction pathways such as those involving ERK, PI3K/Akt, and RalGDS. Growth promotion can also be manifested through paracrine mechanisms involving normal stromal bystanders or recruited inflammatory cells. Resistance to growth inhibitory signals can be achieved through mutations in tumor suppressor genes such as p53, Rb, Arf, and APC, or in receptors such as those for TGF_β_. Additionally, upregulation of expression of cyclin D1 or c-myc, or activating mutations in transcription factors such as _β_-catenin can promote cell proliferation or cell growth.2

A key process in the ability of tumor cells to expand locally and to metastasize is the suppression of apoptotic potential. Resistance to apoptosis can involve the activation of expression of antiapoptotic factors, such as Bcl-2 or Bcl-xL, or the loss of expression or mutation of proapoptotic factors, such as p53. Additionally, mutation in tumor suppressors such as PTEN leads to the activation of intracellular signaling pathways (in this case, the PI3 kinase/Akt pathway) that suppress apoptosis. Relative to Akt, this Ser-Thr kinase is known to target the phosphorylation of several factors associated with regulating apoptosis.3 An additional mechanism of suppression of cancer cell apoptosis can be derived from release of cytokines from the tumor stroma. Clearly, constitutive or induced antiapoptotic factors expressed in tumor cells provide a strong mechanism to suppress cancer therapy efficacy (see below).

Extended replication potential is controlled in part through telomere maintenance, a property associated with virtually all cancer cells. This mechanism is commonly controlled in cancer through upregulation of expression of the telomerase enzyme. Cancer cells also exhibit properties associated with inducing and sustaining angiogenesis, a process that appears to be required for tumor progression. Animal models for tumorigenesis indicate that angiogenesis is a mid-stage property, occurring before the appearance of malignancy.2 Angiogenesis is mediated through a complex interplay of regulatory factors, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). In fact, many tumors exhibit upregulation of VEGF.2 Associated with the appearance of angiogenesis is often the ability of tumor cells to invade local tissues and subsequently to migrate systemically to preferred sites (metastasis). Local invasion is mediated by changes in expression of cell adhesion molecules and integrins, and in changes in expression of extracellular proteases such as MMP-2 and MMP-9. In some situations, the matrix-degrading proteases are produced by the tumor-associated stromal and inflammatory cells.

An important mechanism in the progression of many cancers is the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT). The differentiated epithelial phenotype is typically characterized by the polarization of the cell surface into apical and basolateral domains and by a junctional complex that controls intercellular adhesion. The occurrence of EMT in cancer is associated with the downregulation of expression of E-cadherin, a member of the classic cadherin family that controls cell polarity and tight junctions, and with progression to a metastatic phenotype.

Cancer Progression is Promoted by Inflammation

Chronic inflammation has long been speculated to be intimately associated with the promotion of cancer. In this regard, evidence for the involvement of inflammation with cancer was provided from clinical studies correlating tumor infiltration of immune cells with poor clinical outcome.4 A causal role for inflammation and cancer is suggested from studies reporting reduced cancer incidence in patients undergoing treatment with anti-inflammatory drugs. As many anti-inflammatory compounds inhibit cyclooxygenase-2 activity, it has been suspected that this enzyme is the primary target for prevention. Causative roles for proteolytic enzymes, the transcription factor NF-_κ_B, and cytokines such as TNF are indicated as functionally important molecules that potentiate inflammation-based cancer.4, 5, 6, 7

There are a number of examples whereby inflammation is suspected in cancer progression (pancreatitis with pancreatic cancer, and gastritis with gastric cancer, etc.). However, probably the best-established link is between inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer. Colitis is associated with an approximate 10-fold risk in developing colorectal cancer, and the risk increases significantly with the duration and extent of disease.7 Recent evidence suggests that the development of colitis-associated cancer is manifested by inflammation of the intestinal submucosa directed by contact with the intestinal microflora, which promotes tumor outgrowth in the overlying epithelium. 7

The role of inflammation in cancer has been studied for several years. Tumor development/progression is controlled by reciprocal interactions between neoplastically initiated cells, vascular cells, fibroblasts, and immune cells. In this regard, recent evidence indicates a significant role for innate immune cell involvement in cancer development.8 Obviously, the local production of cytokines and growth factors would favor cancer cell survival and local invasive properties, but these effects would not, on their own, be expected to generate oncogenic events. However, it is known that the local production of reactive oxygen species and metabolites from inflammation pose a mutagenic threat to DNA.

The chemokine IL-8 is a well-established factor in the initiation and progression of inflammation. Relevant to oncogenesis, Sparmann and Bar-Sagi9 demonstrated that oncogenic Ras expression leads to the upregulation of IL-8, which then functions to promote tumor-associated inflammation, angiogenesis, and tumor growth. The authors showed that inhibition of IL-8 with a neutralizing antibody inhibited the growth of tumor cells that express IL-8. Furthermore, the antibody reduced recruitment of neutrophils and macrophages in the derived tumors and reduced recruitment of endothelial cells leading to decreased angiogenesis. These studies9 provide evidence for a regulatory cascade initiating with oncoprotein expression and leading to upregulation of a pro-inflammatory cytokine that recruits key inflammatory cells that promote tumorigenesis.

NF-_κ_B and IKK Activation are Associated with Oncogenesis

A potential link between NF-_κ_B and cancer was suggested by the cloning of the NF-_κ_B p50/p105 subunit, which revealed homology to the cellular homologue (c-rel) of the oncogene (v-Rel) for the avian reticuloendotheliosis virus. Later, the p52 NF-_κ_B subunit was shown to be encoded by a gene that undergoes translocations in certain B-cell lymphomas (the lyt-10 translocation).10, 11 Extensive evidence has now emerged indicating a critical role for NF-_κ_B in promoting oncogenic conversion and in facilitating later stage tumor properties such as metastasis.10, 11

A role for NF-_κ_B in cancer is supported from numerous reports showing that NF-_κ_B is activated (i.e., nuclear) in a number of tumors. Thus, NF-_κ_B (RelA) activation has been detected in a variety of solid tumors, including prostate tumors, breast tumors, melanoma, pancreatic cancer, and lung adenocarcinoma.10, 11, 12 Whether other NF-_κ_B subunits could contribute to oncogenesis is not well established. Relative to this point, the p52 subunit has been shown to be nuclear in a number of breast tumors.10 Additionally, the p50 subunit of NF-_κ_B appears to control both the positive and negative regulation of the expression of the KAI1 tumor suppressor gene. Expression of the oncoprotein _β_-catenin converts the p50 transcriptional complex to a repressive complex through loss of Tip60 coactivator association and the induction of recruitment of transcription co-repressors, leading to loss of expression of the metastasis suppressor gene.13 Thus, expression of p50 in a tumor should not be considered as an indication of lack of NF-_κ_B functional activity.

NF-_κ_B activation has been reported in a number of hematological malignancies. For example, NF-_κ_B is activated, as measured by EMSA, in blasts and stem cells associated with acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) and this is associated with increased IKK activity.14 Importantly, NF-_κ_B activation can be detected in the bone marrow of patients with myelodysplastic syndrome,15 which is considered a precursor disease of AML. RelA/p65 activation was limited to those cells with cytogenetic alterations. NF-_κ_B was also found to be activated in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia.16 High levels of NF-_κ_B activation are found in Hodgkin–Reed–Sternberg cells, in HTVL-1-positive leukemias, B-cell lymphomas of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue, and in primary blasts of chronic myelogenous leukemia. NF-_κ_B activation is also associated with multiple myeloma,17 which is currently treated with compounds that can block NF-_κ_B activation (see below).

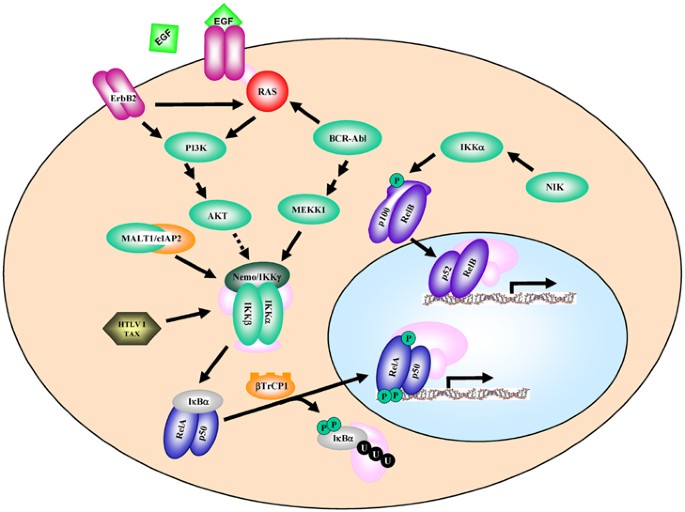

A number of oncoproteins have been shown to induce NF-_κ_B activation (see Figure 2) as measured either through reporter assays or through analysis of nuclear levels of NF-_κ_B.10, 11 For example, oncogenic Ras and Her-2/Neu (ErbB2)10, 11 have been demonstrated to activate NF-_κ_B. In murine fibroblasts, p65/RelA and c-Rel are required for efficient cellular transformation induced by oncogenic Ras.18 Bcr-Abl, the fusion protein associated with chronic myelogenous leukemia, was shown to activate an NF-κ_B-dependent reporter, and inhibition of NF-κ_B with super-repressor I_κ_B_α (SR-I_κ_B_α) expression blocked Bcr-Abl-induced tumor growth.19 Activation of NF-_κ_B by Bcr-Abl has been reported to involve the activation of the kinase MEKK120 (see Figure 2). Consistent with these findings, NF-_κ_B is found activated in Bcr-Abl-positive leukemia,21 although the activation was not associated with IKK activity. The mechanisms of stimulation of NF-_κ_B functional activity by oncoproteins often lags behind the significantly more clear understanding of pathways associated with cytokine and LPS -induction of NF-_κ_B. One of the better understood mechanisms for the activation of NF-_κ_B by an oncoprotein is the mechanism whereby the HTVL-I Tax protein activates NF-κ_B. This protein directly binds and activates the IKK complex.22 The MALT1/c-IAP2 fusion found in certain lymphomas leads to ubiquitination of NEMO/IKK_γ and subsequent NF-_κ_B activation.23 Several studies indicate that PI3K/Akt-dependent signaling activates NF-κ_B activity and that this occurs in a manner dependent on the relative levels of the IKK_α subunit.24 Consistent with this, Akt activation in cancer is proposed to mediate NF-_κ_B activation. In one study, it was shown that Akt is activated in primary acute myeloid leukemia and that this is associated with cell survival and NF-_κ_B activation.25 Another example is the activation of Akt in human melanoma, which leads to NF-_κ_B activation and tumor progression.26 Interestingly, this same group showed that NF-_κ_B-inducing kinase, a regulator of the non-classical pathway, is involved in the activation of NF-_κ_B in melanoma. The activation of NF-_κ_B downstream of Her-2/ErbB2 was shown to involve PI3K/Akt-dependent signaling.27 Relative to other signaling pathways, phosphorylation of FADD was detected in a significant number of lung adenocarcinomas. This was associated with poor clinical outcome and was reported to induce NF-_κ_B activation. Interestingly, high levels of expression of the E3-ubiquitin ligase receptor _β_TRCP1 are proposed to activate NF-_κ_B in pancreatic cancer cells. A summary of the regulatory pathways initiated by oncoproteins and growth factors that target NF-_κ_B is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Pathways of activation of NF-_κ_B by oncoproteins and growth factors. Most of the pathways ultimately target IKK for NF-_κ_B activation. Steps linking certain regulators to IKK may not be direct (e.g., Akt). See text for a description

Given the important role that growth factors play in promoting oncogenesis, it is not surprising that certain growth factors or expression of growth factor receptors has been shown to activate NF-_κ_B (Figure 2). For example, Biswas et al.28 have shown that EGF can activate NF-_κ_B in certain cell types. We have provided evidence that EGF can induce recruitment of p65/RelA to the EAAT2/glutamate transporter promoter through a mechanism independent of I_κ_B degradation. As described previously, the EGF receptor family member Her-2/ErbB2 has been shown to activate NF-_κ_B,27 and evidence indicates that a specific set of genes controlled downstream of Her-2/ErbB2 by NF-_κ_B (E Merkhofer and A Baldwin, unpublished). We and others showed that PDGF can induce NF-_κ_B activation and promote c-myc transcription.10 Also, it has been shown that activated c-kit receptors lead to NF-_κ_B activation.

In addition to the known responses of oncoproteins in activating NF-_κ_B, evidence has been presented that certain tumor suppressors can block NF-_κ_B activation. For example, the tumor suppressor Arf has been shown to inhibit NF-_κ_B through a mechanism involving phosphorylation of Thr505 on p65/RelA induced by ATR and Chk1.29 Additionally, the tumor suppressor CYLD has been demonstrated to block NF-_κ_B activation through its deubiquitinating activity. Regarding the tumor suppressor p53, it was reported that p53 generally inhibits NF-_κ_B function and vice versa;30 however, more complex relationships between p53 and NF-_κ_B have emerged (see below).

Although there is strong evidence that NF-_κ_B functions to promote oncogenesis in a variety of tumors, evidence has been presented that inhibition of NF-_κ_B in skin leads to oncogenic potential and potentiates Ras-induced transformation.31 One mechanism to explain this concept is that inhibition of NF-_κ_B in the skin leads to JNK activation,32 a finding consistent with several reports that NF-_κ_B activation suppresses the phosphorylation and activation of JNK. Similar questions regarding the oncogenic potential of NF-_κ_B arise with the consideration that NF-_κ_B appears to function downstream of the tumor suppressor p53. Vousden and co-workers33 have presented evidence that NF-_κ_B activation is required downstream of p53 in order for this tumor suppressor to induce apoptosis, whereas other experimentation indicates that NF-_κ_B/IKK activation can destabilize p53.34 Similar to the findings of Verma and co-workers,34 we have shown that Bcl-3 activation suppresses p53 activation through upregulated Hdm2 gene expression.35 Hung and co-workers36 have reported that the oncoprotein _β_-catenin can block NF-_κ_B activation. Note that evidence described above indicates that _β_-catenin can interact with the p50 NF-_κ_B transcriptional complex and convert it to a transcriptional repressor.13 Overall, these findings suggest that NF-_κ_B can function, under certain conditions, as a tumor suppressor.

Modes of Action of NF-_κ_B and IKK in Cancer

Clearly, NF-_κ_B functions as a transcriptional regulator in a variety of cancer cells as evidenced through the identification of cancer-specific, cancer-relevant gene targets controlled by NF-_κ_B (see Figures 1 and 3). For example, gene profiling has identified a subset of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma that requires NF-_κ_B for growth and survival. Inhibition of NF-_κ_B activation blocks the expression of genes associated with this type of lymphoma.37 We have identified a set of approximately 25 genes that are regulated by NF-_κ_B in a manner dependent on oncogenic Ras expression in murine fibroblasts.18 Interestingly, these studies indicate that the NF-_κ_B-controlled gene sets in distinct oncogenic settings are significantly different. As described above,13 the p50 NF-_κ_B subunit can positively or negatively regulate KAI-1 tumor suppressor gene expression in a manner dependent on the activation levels of _β_-catenin.

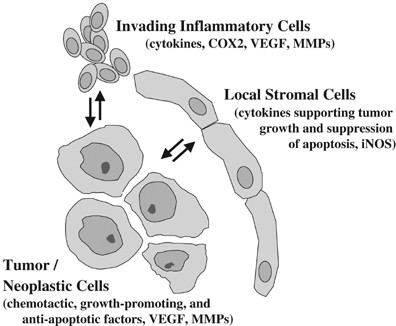

Figure 3

Roles for NF-_κ_B in tumor and tumor-associated cells. NF-_κ_B activation is relevant in tumor/neoplastic cells, in invading inflammatory cells, and in tumor-associated stromal compartment. See text for a description

One of the key properties associated with transformed cells is their ability to resist apoptosis. Experiments revealed that induction of RasV12 in immortalized Rat1 fibroblasts leads to cellular transformation but not to apoptosis. If NF-κ_B was inhibited in these cells by expression of SR-I_κ_B_α, then the induction of RasV12 expression was associated with high levels of apoptosis.10 Consistent with this point, inhibition of NF-_κ_B in certain tumor cell lines leads to apoptotic cell death.10, 11 Hodgkin's lymphoma has proven to be a cancer that is strongly controlled by NF-_κ_B activation. Proliferation and survival of Hodgkin/Reed–Sternberg cells is blocked when NF-κ_B is inhibited by I_κ_B_α expression.38 Genes regulated by NF-_κ_B that suppress apoptosis, such as Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL, are often expressed in human cancers (see Figures 1 and 3). Consistent with this, inhibition of NF-_κ_B in Hodgkin/Reed–Sternberg cells led to the loss of expression of antiapoptotic effectors A1/Bfl-1, c-IAP2, TRAF1, and Bcl-xL.39 Another mechanism whereby NF-_κ_B may block cell death is through its ability to suppress persistent JNK activation and the generation of reactive oxygen species.40 Relative to a role for the NF-κ_B upstream pathway in preventing apoptosis, Hu et al.41 have shown that IKK_β activation in breast cancer cells leads to the direct phosphorylation and degradation of the proapoptotic factor Foxo3a, suppressing apoptotic potential in certain breast cancer cells, and promoting cell proliferation.

NF-κ_B activation also appears to promote cellular proliferation, consistent with a role in promoting growth sufficiency of cancer cells. Evidence has been presented that NF-κ_B can bind and activate the cyclin D1 promoter, promoting Rb hyperphosphorylation.10, 11 Additionally, the I_κ_B homologue Bcl-3 in association with p52 homodimers has also been found to potently activate transcription of the cyclin D1 gene. Interestingly, IKK_α has been proposed to play a role in cyclin D1 transcription through the Tcf site, via its ability to control β_-catenin phosphorylation.42 Consistent with a role for IKK_α in promoting cyclin D1 transcription, Karin et al.11 colleagues found that IKK_α is required for RANK signaling and cyclin D1 expression in mammary gland development. Other mechanisms whereby NF-κ_B may potentiate oncogenic conversion and maintenance is through its reported requirement for the upregulation of HIF-1_α43 and its regulation of c-myc transcription.10, 11 Consistent with these reports, inhibition of NF-_κ_B in several tumor xenografts inhibits growth of those tumors.10, 11, 19

NF-_κ_B activation in tumor cells, and in tumor-associated stromal and endothelial cells, likely plays a role in tumor progression and invasion. The role of NF-κ_B in invading myeloid cells has been addressed using IKK_β ablation in these cells in a carcinogen/inflammation model for colorectal cancer.5 In that study, NF-_κ_B was shown to control production of cytokines in myeloid cells, which are involved in promoting tumor growth. In another interesting study, NF-_κ_B appears to mediate an IL-1/nitric oxide paracrine growth loop involving stromal fibroblasts and pancreatic neoplastic cells.44 In this regard, NF-κ_B has been reported to promote both angiogenesis and metastasis in certain tumor models, potentially through regulation of VEGF and MMPs (Figure 1).10, 11 In a more direct study, expression of the SR-I_κ_B_α blocked growth, angiogenesis, and metastasis of human melanoma and ovarian cancer cells grown as xenografts,45 which correlated with reduced VEGF and IL-8 expression.45 Consistent with a role in metastasis, NF-_κ_B has been shown to mediate the EMT.46

Roles for NF-_κ_B Activation in Inflammation-associated Cancer

As outlined above, there is compelling evidence that inflammation promotes cancer progression. Given the key role that NF-_κ_B plays in both innate and acquired immunity, it would not be surprising that NF-_κ_B plays an essential role in providing the link between inflammation and cancer progression. In fact, recently published data directly implicate NF-κ_B activation as a key component in inflammation-based cancer progression. Karin and co-workers5 utilized the IKK_β conditional knockout to test the role of the NF-κ_B activation pathway in controlling tumorigenesis in a colitis-associated model for cancer. Deletion of IKK_β in intestinal epithelial cells dramatically reduced tumor number in this model, but not tumor size. The reduction in tumor number was explained by strongly enhanced apoptosis in the DNA-damaged intestinal target cells, consistent with a role of NF-κ_B in suppressing apoptotic potential. Importantly, tumor-associated inflammation was not reduced in this component of the model. These data argue that NF-κ_B activation is important in the early stages of DNA-damaged induced tumorigenesis (as an antiapoptotic mediator) but not in the prominent growth phase of tumorigenesis. Greten et al.5 went on to show that deletion of IKK_β in myeloid cells, however, leads to a significant reduction in tumor size but not tumor number, and to a reduction in tumor-associated proinflammatory cytokine levels that are likely to serve as tumor growth factors. This result is consistent with the importance of NF-κ_B in promoting myeloid cell recruitment and inflammatory gene expression as part of the inflammatory phase of oncogenesis (see Figure 2). In another related study, Maeda et al.47 showed that loss of IKK_β in hepatocytes actually promoted chemical-induced hepatocarcinogenesis through a mechanism involving enhanced ROS production and JNK activation with associated cell death, leading to a compensatory response in surviving hepatocytes. Knockout of IKK_β in Kupffer cells suppressed hepatocarcinogenesis, indicating an inflammatory role for these hemopoietic-derived cells in this model.

In another recently described model, Ben-Neriah and co-workers6 utilized a mouse knockout for the Mdr2 gene, which develops spontaneous hepatitis followed by hepatocellular carcinoma. Thus this serves as a straightforward model for inflammation-based oncogenesis. Inhibition of NF-κ_B through regulatable SR-I_κ_B_α expression did not block hepatitis or the earliest stages of neoplasia. However, inhibition of NF-κ_B at later stages (either through I_κ_B_α expression or through TNF antibodies) blocked progression to hepatocellular carcinoma at least partly through the induction of apoptosis. In this model, NF-_κ_B does not play a role in the early inflammation-associated neoplastic growth but, acting downstream of TNF, functions to suppress apoptosis and to allow cancer malignancy to progress.

Less direct, but highly suggestive evidence for a role of NF-_κ_B in inflammation-associated cancer has been presented. For example, NF-κ_B activation is suggested to promote neoplastic progression in Barrett's esophagus, a disease associated with inflammation. It is proposed that this is mediated through the ability of NF-κ_B to regulate Cox-2 and IL-8 gene expression. Jung et al.43 reported that IL-1_β induces HIF-1_α gene expression through a mechanism involving the induction of PGE2 through the NF-κ_B-dependent upregulation of Cox-2. These studies suggest a direct mechanism whereby cytokines such as IL-1_β promote oncogenesis. Regarding the work of Sparmann and Bar-Sagi9 described above, it is likely that the ability of Ras to activate IL-8 gene expression and subsequent neutrophil recruitment is mediated through NF-_κ_B (see Figure 2). The evidence for a role of NF-_κ_B in controlling inflammation-based oncogenesis suggests that inhibitors of this transcription factor are likely to serve as key components in the prevention of many cancers. Thus, studies demonstrating the ability of non-steroid anti-inflammatory compounds to suppress the development of some cancers are consistent with this hypothesis (see below).

Pharmacological Inhibitors of NF-_κ_B Pathways Often, but not Always, Suppress Cancer Growth: Evidence for Specificity?

Experimentation reveals that compounds that block NF-_κ_B activation can serve to block cancer cell growth.10, 11, 12 Probably, the most clinically relevant example of this response is the use of proteasome inhibitors for treatment of multiple myeloma, which is considered a disease dependent on NF-_κ_B activation.48 Bortezomib/Velcade is a highly specific inhibitor of the proteasome, and is currently approved for treatment of multiple myeloma.48 The importance of NF-_κ_B in multiple myeloma is suggested from its involvement downstream of CD40, the TNF receptor family member that is expressed in a variety of B-cell malignancies and which is associated with multiple myeloma homing. Consistent with this, monoclonal antibodies to CD40 block CD40L-induced NF-_κ_B activation as well as IL-6 and VEGF secretion in cocultures of multiple myeloma cells and bone marrow-derived stromal cells.

Thalidomide and immunomodulatory thalidomide analogues have shown activity against relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma.49 Additionally, thalidomide was evaluated with dexamethasone in earlier stage disease and yielded response rates in the range of 70%. Treatment of smoldering/indolent disease with single-agent thalidomide yielded overall response rates in the 35% range.49 There is evidence that thalidomide and its analogues have direct impact on multiple myeloma cells through the induction of apoptosis and growth arrest. Importantly, thalidomide was shown to inhibit NF-_κ_B in these cells.50 These results are consistent with our earlier report that thalidomide blocks NF-_κ_B activation via suppression of IKK activity.51

Other hematological malignancies are susceptible to NF-_κ_B inhibition. Proteasome inhibition inhibited cell growth and induced apoptosis in adult T-cell leukemia, an NF-κ_B-relevant malignancy, correlated with stabilized I_κ_B_α and inhibited NF-_κ_B.52 A small molecule inhibitor of IKK (PS-1145) was found to be selectively toxic for subtypes of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma cells that are associated with NF-_κ_B activation.37 This compound was shown to lead to downregulation of a set of NF-_κ_B-dependent genes.

As described above, proteasome inhibitors have shown efficacy in the treatment of multiple myeloma, but evidence for clinical efficacy for treatment of solid tumors is missing. However, proteasome inhibitors have shown efficacy in a number of preclinical models for solid tumors and these responses are typically associated with the inhibition of NF-_κ_B and of relevant gene expression. For example, proteasome inhibitors have shown antitumor activity in models of breast, lung, colon, bladder, ovary, pancreas, and prostate cancers.53 A recent study showed that the proteasome inhibitor PS-341 caused growth arrest and apoptosis in human glioblastoma cell lines and tumor explants.53 This response was correlated with inhibition of NF-_κ_B and downregulation of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL.

Although bortezomib/PS-341/Velcade can block NF-_κ_B activation, it is unclear whether the primary mode of action of this compound in multiple myeloma or other malignancies is dependent on its ability to inhibit NF-_κ_B activation. In this regard, bortezomib has been reported to block JNK activation through the upregulation of MKP-154 and to modulate Ca2+/mitochondrial function55 in addition to its effects on NF-_κ_B. Additionally, it has been reported that bortezomib initiates tumor cell-selective apoptosis that is correlated with the induction of the pro-apoptotic gene encoding the BH3-only protein Noxa.56 In that study, proteasome inhibition did not correlate with a generalized inhibitory effect on NF-_κ_B.

Although NSAIDs are described generally as inhibitors of Cox-2 activity, it is also possible that these compounds target NF-_κ_B activity. In fact, it was recently shown in vitro that the Cox-2 inhibitor celecoxib inhibits NF-_κ_B activation induced by TNF through a mechanism that suppressed IKK and Akt activation.57 This same group showed that NSAIDs exhibit differing strengths in their ability to suppress NF-_κ_B and to downregulate NF-_κ_B-dependent gene expression, with celecoxib as the most potent inhibitor and aspirin the weakest.58 Celecoxib induced apoptosis of a variety of leukemia cell lines and this was correlated with suppression of NF-_κ_B activation.59 Thus it is possible that an effect of NSAIDs in preventing cancer progression is through inhibition of NF-_κ_B.

A range of compounds that have NF-_κ_B inhibitory activity have been shown to have antitumor or antiangiogenic potential as studied on tumor cell lines and derived xenografts. One of the more extensively studied compounds in this group is curcumin, a diferuloylmethane derived from turmeric, which has been shown to suppress NF-_κ_B activation and NF-_κ_B-dependent gene expression. Previous studies had indicated strong antitumor effects on AML and prostate cancer cell lines.60, 61 Recently, curcumin has been shown to induce growth arrest and apoptosis in mantle cell lymphoma cell lines.62 Curcumin suppressed the expression of cyclin D1, Bcl-2, and Bcl-xL, all known NF-_κ_B target genes. The IKK inhibitors BAY 11-7082 and AS602868 have shown efficacy in leukemia models via increased apoptosis.63, 64 Another NF-_κ_B inhibitor, parthenolide, has shown efficacy against human AML stem and progenitor cells,65 and cholangiocarcinoma cells.66 Sulfasalazine, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammtory drug that blocks NF-κ_B activation, was shown to inhibit growth and induce apoptosis in glioblastoma cell lines and primary cultures, as did expression of SR-I_κ_B_α.67 Finally, arsenic, which is used for the treatment of acute promyelocytic leukemia, was shown to inhibit constitutive NF-_κ_B/IKK activity and NF-_κ_B target genes in Hodgkin/Reed–Sternberg cell lines, and to induce apoptosis in these cells. Expression of p65/RelA overcame the arsenic-induced cell death, suggesting the relevance of NF-_κ_B as the target for arsenic.68 A concern with some of these studies is that the therapeutic effects of certain inhibitors may involve NF-_κ_B-independent targets. Additionally, a number of well- established dietary chemopreventive compounds have been shown to inhibit NF-_κ_B.12

The Role of NF-_κ_B in Regulating Cancer Therapy Responses

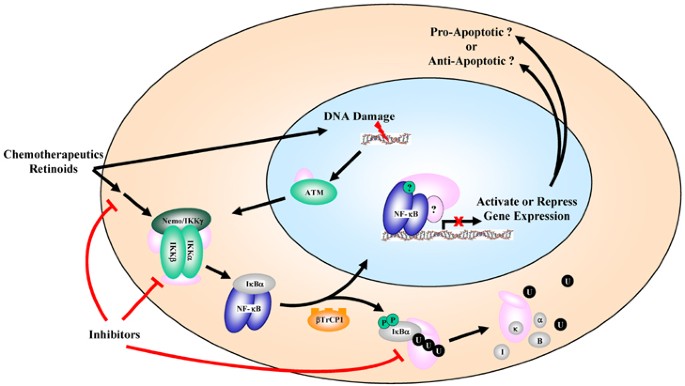

Evidence was presented in the mid-1990s that DNA-damaging and stress-inducing agents activate NF-_κ_B.10, 11, 12, 69 Our group demonstrated NF-_κ_B activation in response to chemotherapy by daunorubicin and to irradiation.70 Inhibition of NF-κ_B by expression of the SR-I_κ_B_α strongly enhanced the apoptotic efficacy of daunorubicin and of radiation.70 The topoisomerase I inhibitor CPT-11 activated NF-κ_B in experimental colorectal tumors and administration of adenovirally expressed SR-I_κ_B_α or the proteasome inhibitor PS-341 inhibited NF-_κ_B activation and significantly enhanced the apoptotic response of the tumor to CPT-11.71, 72 Thus, the model was that activation of NF-_κ_B in response to chemotherapies and to radiation functioned to suppress the apoptotic potential of that cancer therapy10 (see Figure 4). A number of other reports using a variety of chemotherapies and a variety of approaches to block NF-_κ_B have supported this model.10, 11, 12, 69 The recent review by Nakanishi and Toi69 provides a thorough outline of different chemotherapies that activate NF-_κ_B and of compounds that are used to block NF-_κ_B activation to promote cancer therapy efficacy. Furthermore, new reports indicate that NF-_κ_B inhibition sensitizes cancer cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis through the sustained activation of JNK.73 Additionally, a study analyzing NF-_κ_B inhibition in association with radiation indicated that NF-_κ_B activation leads to radiation resistance in experimental colorectal tumors.10 Based on these studies, clinical trials utilizing certain chemotherapies in conjunction with NF-_κ_B inhibitors (proteasome inhibitors, thalidomide, etc.) are presently underway.

Figure 4

Activation of NF-_κ_B by cancer therapies can lead to anti- or proapoptotic responses. NF-_κ_B is shown activated by standard chemotherapeutics or by retinoids. Many of the chemotherapies induce a DNA damage response, as shown. In the nucleus, NF-_κ_B can mediate a transcriptional response, apparently determined by the chemotherapy in the setting of the cancer cell regulatory environment, which either activates or inhibits apoptotic regulatory genes. Inhibitors of the NF-_κ_B pathway can target upstream pathways, IKK, or the proteasome-dependent activation of NF-_κ_B

Although there is strong evidence that NF-_κ_B often functions in an antiapoptotic manner downstream of its activation by chemotherapy or radiation , recent data indicate that NF-_κ_B activation can also function in a proapoptotic manner after activation by certain nontraditional cancer therapies in certain cell types (see Figure 4). Under these conditions, NF-_κ_B inhibition would presumably be counterintuitive as a cancer therapy. Thus, apoptosis induced by the retinoid 3-Cl-AHPC was reported to require NF-_κ_B activation.74 Exposure of cells to this compound blocked expression of XIAP, Bcl-xL, and c-IAP1 and enhanced the expression of proapoptotic death receptors DR4 and DR5 as well as Fas. In a similar study, the retinoid CD437 activated NF-_κ_B in DU145 prostate cancer cells and contributed to the induction of apoptosis through the upregulation of the death receptors DR4 and DR5.75 Another study indicated that aspirin and UV-C induce apoptosis through a mechanism that drives p65/RelA to the nucleolus, leading to an inability to activate NF-_κ_B-dependent genes.76

More recently, Perkins and co-workers found that NF-_κ_B activation by doxorubicin and daunorubicin in U-2 OS osteosarcoma cells promoted cell death. In that paper, NF-_κ_B activation by these chemotherapeutic compounds led to the binding and repression of antiapoptotic genes such as Bcl-xL. Interestingly, the activation of etoposide in the same cells led to the traditional antiapoptotic response and was associated with the activation of Bcl-xL gene expression. Importantly, it was found that daunorubicin induced association of RelA with the histone deacetylases HDAC1, 2, and 3, consistent with the role of NF-_κ_B in repressing gene expression downstream of responses to that chemotherapy. A similar report78 indicated that NF-_κ_B that is activated by doxorubicin is deficient in transcriptional activity, which is associated with reduced phosphorylation and acetylation of RelA. This paper indicated that the repressive effect was histone deacetylase independent and that RelA was not stably bound to target gene promoters. A recent paper by Aggarwal and co-workers79 showed that NF-_κ_B activation by doxorubicin in four colorectal cancer cells was required for the anticancer efficacy of the drug. However, there are other papers where doxorubicin-induced cell death was inhibited by NF-_κ_B activation.10, 69 It is presently unclear which signaling events ultimately determine whether NF-_κ_B activation will lead to a pro- or antiapoptotic response, but it is reasonable to speculate that the response is determined by the phenotypic profile of the tumor in combination with the specific cancer therapy (Figure 4). In this respect, the activation of NF-_κ_B itself by the relevant cancer therapy is likely not to be the determining outcome on gene expression. Presumably, modification of NF-_κ_B subunits (or lack thereof) related to the regulatory status of the cancer will then determine whether NF-_κ_B functions in the anti- or proapoptotic response (Figure 4). These studies suggest the importance of the potential of individualized cancer therapy relative to adjuvant approaches where NF-_κ_B is inhibited.

Summary

An enormous amount of data strongly implicate the transcription factor NF-_κ_B in a variety of oncogenic mechanisms. Additionally, compelling experimentation indicates an important role of NF-_κ_B in modulating cancer therapy efficacy. A major challenge is to distinguish the situations where NF-_κ_B functions pro-oncogenically/antiapoptotically from those where it may function as a tumor suppressor and a proapoptotic factor. In this regard, it is important to identify the molecular mechanisms that dictate these outcomes. A second challenge is to bring rational inhibitors of NF-_κ_B or its upstream regulatory pathways to clinical cancer therapy in a manner consistent with an antiapoptotic role, either as stand-alone therapies or as adjuvants with existing or new therapies.

Abbreviations

IKK:

I_κ_B kinase

SR-I_κ_B_α_:

super-repressor I_κ_B_α_

References

- Hayden MS, Ghosh S (2004) Signaling to NF-_κ_B. Genes Dev. 18: 2195–2224.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Hanahan D, Weinberg R (2000) The hallmarks of cancer. Cell 100: 57–70.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Downward J (2004) PI3-kinase, Akt, and cell survival. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 15: 177–182.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Coussens L, Werb Z (2002) Inflammation and cancer. Nature 420: 860–867.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Greten FR, Eckmann L, Greten TF, Park JM, Li ZW, Egan LJ, Kagnoff M, Karin M (2004) IKK_β_ links inflammation and tumorigenesis in a mouse model of colitis-associated cancer. Cell 118: 285–296.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Pikarsky E, Porat RM, Stein I, Abramovitch R, Amit S, Kasem S, Gutkovich-Pyest E, Urieli-Shoval S, Galun E, Ben-Neriah Y (2004) NF-_κ_B functions as a tumor promoter in inflammation-associated cancer. Nature 431: 461–466.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Clevers H (2004) At the crossroads of inflammation and cancer. Cell 118: 671–674.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Balkwill F, Charles K, Mantovani A (2005) Smoldering and polarized inflammation in the initiation and promotion of malignant disease. Cancer Cell 7: 211–217.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Sparmann A, Bar-Sagi D (2004) Ras-induced IL-8 expression plays a critical role in tumor growth and angiogenesis. Cancer Cell 6: 447–458.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Baldwin AS (2001) Control of oncogenesis and cancer therapy resistance by the transcription factor NF-_κ_B. J. Clin. Invest. 107: 241–246.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Karin M, Cao Y, Greten FR, Li ZW (2002) NF-_κ_B in cancer: from innocent bystander to major culprit. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2: 301–310.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Yamamoto Y, Gaynor RB (2001) Therapeutic potential of inhibition of the NF-_κ_B pathway in treatment of inflammation and cancer. J. Clin. Invest. 107: 134–142.

Article Google Scholar - Kim JH, Kim B, Cai L, Choi HJ, Ohgi KA, Tran C, Chen C, Chung CH, Huber O, Rose DW, Sawyers CL, Rosenfeld M, Baek SH (2005) Transcriptional regulation of a metastasis suppressor gene by Tip60 and beta-catenin complexes. Nature 434: 921–926.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Baumgartner B, Weber M, Quirling M, Fischer C, Page S, Adam M, Von Schilling C, Waterhouse C, Schmid C, Neumeier D, Brand K (2002) Increased IKK activity is associated with activated NF-_κ_B in acute myeloid blasts. Leukemia 16: 2062–2071.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Braun T, Carvalho G, Coquelle A, Vozenin MC, Leppelley P, Hirsch F, Kiladjian JJ, Ribrag V, Fenaux P, Kroemer G (2006) NF-_κ_B constitutes a potential therapeutic target in high-risk myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood 107: 1154–1165.

Google Scholar - Kordes U, Krappmann D, Heissmeyer V, Ludwig WD, Scheidereit C (2002) NF-_κ_B is constitutively activated in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia 14: 399–402.

Article Google Scholar - Mitsiades N, Mitsiades CS, Poulaki V, Chauhan D, Fanourakis G, Gu X, Bailey C, Joseph M, Liberman TA, Treon SP, Munshi NC, Richardson PG, Hideshima T, Anderson KC (2002) Molecular sequelae of proteasome inhibition in human multiple myeloma cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99: 14374–14379.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Hanson JL, Hawke N, Kashatus D, Baldwin AS (2004) NF-_κ_B subunits RelA/p65 and c-Rel potentiate but are not required for Ras-induced cellular transformation. Cancer Res. 64: 7248–7255.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Reuther JY, Reuther GW, Cortez D, Pendergast AM, Baldwin AS (1998) A requirement for NF-_κ_B in Bcr-Abl-mediated transformation. Genes Dev. 12: 968–981.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Nawata R, Yugiri T, Nakamura Y, Ariyoshi K, Takahashi T, Sato Y, Oka Y, Tanizawa Y (2003) MEKK1 mediates the antiapoptotic effect of the Bcr-Abl oncoene through NF-_κ_B activation. Oncogene 22: 7774–7780.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Munzert G, Kirchner D, Ottmann O, Bergmann L, Schmid R (2004) Constitutive NF-_κ_B/Rel activation in Philadelphia chromosome positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leuk. Lymphoma 45: 1181–1184.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Jeang KT (2001) Functional activities of the human T-cell leukemia virus type I Tax oncoprotein: cellular signaling through NF-_κ_B. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 12: 207–217.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Zhou H, Du M, Dixit VM (2005) Constitutive NF-_κ_B activation by the t(11;18)(q21;q21) product in MALT lymphoma is linked to deregulated ubiquitin ligase activity. Cancer Cell 7: 425–431.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Gustin JA, Ozes ON, Akca H, Pincheira R, Mayo LD, Li Q, Guzman JR, Korgaonkar CK, Donner DB (2003) Cell type specific expression of the I_κ_B kinases determines the significance of PI3K/Akt signaling to NF-_κ_B activation. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 1615–1620.

Article Google Scholar - Grandage VL, Gale RE, Linch DC, Khwaja A (2005) PI3-kinase/Akt is constitutively active in primary acute myeloid leukemia cells and regulates survival and chemoresistance via NF-_κ_B, map kinase, and p53 pathways. Leukemia 19: 586–594.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Dhawan P, Singh A, Ellis D, Richmond A (2002) Constitutive activation of Akt/protein kinase B in melanoma leads to upregulation of NF-_κ_B and tumor progression. Cancer Res. 72: 7335–7442.

Google Scholar - Pianetti S, Arsura M, Romieu-Mourez R, Coffey RJ, Sonenshein SE (2001) Her-2/neu overexpression induces NF-κ_B via a PI3-kinase/Akt pathway involving calpain-mediated degradation of I_κ_B_α that can be inhibited by the tumor suppressor PTEN. Oncogene 20: 1287–1299.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Biswas DK, Cruz AP, Gansberger E, Pardee AB (2000) EGF-induced NF-_κ_B activation: a major pathway of cell-cycle progression in estrogen receptor negative breast cancer cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97: 8542–8547.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Rocha S, Garrett M, Campbell KJ, Schumm K, Perkins N (2005) Regulation of NF-_κ_B and p53 through activation of ATR and Chk1 by the ARF tumor suppressor. EMBO J. 24: 1157–1169.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Webster GA, Perkins ND (1999) Transcriptional crosstalk between NF-_κ_B and p53. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19: 3485–3495.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Dajee M, Lazarov M, Zhang JY, Cai T, Green CL, Russell AJ, Marinkovich MP, Tao S, Lin Q, Kubo Y, Khavari PA (2003) NF-_κ_B blockade and oncogenic Ras trigger invasive human epidermal neoplasia. Nature 421: 639–643.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Zhang JY, Green CL, Tao S, Khavari PA (2004) NF-_κ_B RelA opposes epidermal proliferation driven by TNFR1 and JNK. Genes Dev. 18: 17–22.

Article Google Scholar - Ryan KM, Ernst MK, Rice NR, Vousden KH (2000) Role of NF-_κ_B in p53-mediated programmed cell death. Nature 404: 892–897.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Tergaonkar V, Pando M, Vafa O, Wahl G, Verma I (2002) p53 stabilization is decreased upon NF-_κ_B activation: a role for NF-_κ_B in acquisition of resistance to chemotherapy. Cancer Cell 1: 493–503.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Kashatus D, Cogswell P, Baldwin A (2006) The Bcl-3 oncoprotein suppresses p53 activation. Genes Dev. 20: 225–235.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Deng J, Miller SA, Wang HY, Xia W, Wen Y, Zhou BP, Li Y, Lin SY, Hung MC (2002) _β_-Catenin interacts with and inhibits NF-_κ_B in human colon and breast cancer. Cancer Cell 2: 323–334.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Lam LT, Davis RE, Pierce J, Hepperle M, Xu Y, Hottelet M, Nong Y, Wen D, Adams J, Dang L, Staudt LM (2005) Small molecule inhibitors of IKK are selectively toxic for subgroups of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma defined by gene expression profiling. Clin. Cancer Res. 11: 28–40.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Bargou RC, Emmerich F, Krappmann D, Bommert K, Mapara MY, Arnold W, Royer HD, Grinstein E, Greiner A, Scheidereit C, Dorken B (1997) Constitutive nuclear NF-_κ_B-RelA activation is required for proliferation and survival of Hodgkin's disease tumor cells. J. Clin. Invest. 100: 2961–2969.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Hinz M, Loser P, Mathas S, Krappmann D, Dorken B, Scheidereit C (2001) Constitutive NF-_κ_B maintains high expression of a characteristic gene network, including CD40 and CD86, and a set of anti-apoptotic genes in Hodgkin/Reed–Sternberg cells. Blood 97: 2798–2807.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Luo JL, Kamata H, Karin M (2005) IKK/NF-_κ_B signaling: balancing life and death – a new approach to cancer therapy. J. Clin. Invest. 115: 2625–2632.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Hu MC, Lee DF, Xia W, Golfman LS, Ou-Yang F, Yang JY, Zou Y, Bao S, Hanada N, Saso H, Kobayashi R, Hung MC (2004) IKK_β_ promotes tumorigenesis through inhibition of forkhead Foxo3a. Cell 117: 225–237.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Albanese C, Wu K, D'Amico M, Jarrett C, Joyce D, Hughes J, Hulit J, Sakamaki T, Fu M, Ben-Ze'ev A, Bromberg JF, Lamberti C, Verma U, Gaynor RB, Byers SW, Pestell RG (2003) IKK_α_ regulates mitogenic signaling through transcriptional induction of cyclin D1 via Tcf. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14: 585–599.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Jung YJ, Isaacs JS, Lee S, Trepel J, Neckers L (2003) IL-1_β_-mediated upregulation of HIF-1_α_ via an NF-κ_B/Cox-2 pathway identifies HIF-1_α as a critical link between inflammation and oncogenesis. FASEB J. 17: 2115–2117.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Muerkoster S, Wegehenkel K, Arlt A, Witt M, Sipos B, Kruse ML, Sebens T, Kloppel G, Kalthoff H, Folsch UR, Schafer H (2004) Tumor stroma interactions and chemoresistance in pancreatic ductal carcinoma cells involving increased secretion and paracrine effects of nitric oxide and IL-1_β_. Cancer Res. 64: 1331–1337.

Article Google Scholar - Huang S, Robinson JB, DeGuzman A, Bucana CD, Fidler IJ (2000) Blockade of NF-_κ_B signaling inhibits angiogenesis and tumorigenesis of human ovarian cancer cells by suppressing vascular endothelial growth factor and IL-8. Cancer Res. 60: 5334–5339.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Huber MA, Azoitei N, Baumann B, Grunert S, Sommer A, Pehamberger H, Kraut N, Beug H, Wirth T (2004) NF-_κ_B is essential for epithelial–mesenchymal transition and metastasis in a model of breast cancer progression. J. Clin. Invest. 114: 569–581.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Maeda S, Kamata H, Luo JL, Leffert H, Karin M (2005) IKK_β_ couples hepatocyte death to cytokine-driven compensatory proliferation that promotes chemical hepatocarcinogenesis. Cell 121: 977–990.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Richardson PG, Hideshima T, Mitsiades C, Anderson KC (2004) Proteasome inhibition in hematologic malignancies. Ann. Med. 36: 304–314.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Rajkumar SV (2003) Thalidomide in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma and overview of experience in smoldering/indolent disease. Semin. Hematol. 40: 17–22.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Mitsiades N, Mitsiades C, Poulaki V, Chauhan D, Richardson P, Hideshima T, Munshi N, Treon S, Anderson KC (2002) Apoptotic signaling induced by immunomodulatory thalidomide analogs in human multiple myeloma cells: therapeutic implications. Blood 99: 4525–4530.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Keifer J, Guttridge D, Ashburner B, Baldwin AS (2001) Inhibition of NF-_κ_B activity by thalidomide through suppression of I_κ_B kinase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 22382–22387.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Nasr R, El-Sabban M, Karam J, Dbaibo G, Kfoury Y, Arnulf B, Lepelletier Y, Bex F, de The H, Hermine O, Bazarbachi A (2005) Efficacy and mechanism of action of the proteasome inhibitor PS-341 in T-cell lymphomas and HTLV-I-associated adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma. Oncogene 13: 419–430.

Article Google Scholar - Yin D, Zhou H, Kumagai T, Liu G, Ong J, Black K, Koeffler HP (2005) Proteasome inhibitor PS-341 causes cell growth arrest and apoptosis in human glioblastoma multiforme. Oncogene 24: 344–354.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Small GW, Shi YY, Edmund NA, Somasundaram S, Moore DT, Orlowski RZ (2004) Evidence that MKP-1 induction by proteasome inhibitors plays an anti-apoptotic role. Mol. Pharm. 66: 1478–1490.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Landowski T, Megli C, Nullmeyer K, Lynch R, Dorr RT (2005) Mitochondrial-mediated disregulation of Ca2+ is a critical determinant of Velcade (PS-341/Bortezomib) cytotoxicity in myeloma cell lines. Cancer Res. 65: 3828–3836.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Fernandez Y, Verhaegen M, Miller TP, Rush JL, Steiner P, Opipari AW, Lowe SW, Soengas MS (2005) Differential regulation of noxa in normal melanocytes and melanoma cells by proteasome inhibition: therapeutic implications. Cancer Res. 65: 6294–6304.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Shishodia S, Koul D, Aggarwal BB (2004) Cox-2 inhibitor celecoxib abrogates TNF-induced NF-_κ_B activation through inhibition of activation of I_κ_B kinase and Akt in human non-small cell lung carcinoma: correlation with suppression of Cox-2 synthesis. J. Immunol. 173: 2011–2022.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Takada Y, Bhardwaj A, Potdar P, Aggarwal BB (2004) Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents differ in their ability to suppress NF-_κ_B activation, inhibition of expression of Cox-2 and cyclin D1, and abrogation of tumor cell proliferation. Oncogene 23: 9247–9258.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Subhashini J, Mahipal S, Reddanna P (2004) Anti-proliferative and apoptotic effects of celecoxib on human chronic myeloid leukemia in vitro. Cancer Lett. 224: 31–43.

Article Google Scholar - Anto R, Mukhopadhyay A, Denning K, Aggarwal BB (2002) Curcumin induces apoptosis through activation of caspase-8, Bid cleavage, and cytochrome c release: it suppression by ectopic expression of Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL. Carinogenesis 23: 143–150.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Mukhopadhyay A, Bueso-Ramso C, Chatterjee D, Pantazis P, Aggarwal BB (2001) Curcumin downregulates cell survival mechanisms in human prostate cancer cell lines. Oncogene 20: 7597–7609.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Shishodia S, Amin H, Lai R, Aggarwal BB (2005) Curcumin inhibits constitutive NF-_κ_B activation, induces G1/S arrest, suppresses proliferation, and induces apoptosis in mantle cell lymphoma. Biochem. Pharmacol. 70: 700–713.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Garcia M, Alaniz L, Lopes E, Blanco G, Hajos S, Alvarez E (2005) Inhibition of NF-_κ_B activity by BAY 11-7082 increases apoptosis in multidrug resistant leukemic T-cell lines. Leuk. Res. 24 (E-pub ahead of print).

- Frelin C, Imbert V, Griessinger E, Peyron A-C, Rochet N, Phillip P, Dageville C, Sirvent A, Hummelsberger M, Berard E, Dreano M, Sirvent N, Peyron J-F (2005) Targeting NF-_κ_B activation via pharmacologic inhibition of IKK2-induced apoptosis of human acute myeloid leukemia cells. Blood 105: 804–811.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Guzman M, Rossi R, Karnischky L, Li X, Peterson D, Howard, Jordan CT (2005) The sesquiterpene lactone parthenolide induces apoptosis of human acute myelogenous leukemia stem and progenitor cells. Blood 105: 4163–4169.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Kim JH, Liu L, Lee S, Kim Y, You K, Kim DG (2005) Susceptibility of cholangiocarcinoma cells to parthenolide-induced apoptosis. Cancer Res. 65: 6312–6320.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Robe PA, Bentires-Alj M, Bonif M, Rogister B, Deprez M, Haddada H, Khac MT, Jolois O, Erkmen K, Merville MP, Black PM, Bours V (2004) In vitro and in vivo activity of the NF-_κ_B inhibitor sulfasalazine in human glioblastomas. Clin. Cancer Res. 10: 5595–5603.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Mathas S, Lietz A, Janz M, Hinz M, Jundt F, Scheidereit C, Bommert K, Dorken B (2003) Inhibition of NF-_κ_B essentially contributes to arsenic-induced apoptosis. Blood 102: 1028–1034.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Nakanishi C, Toi M (2005) NF-_κ_B inhibitors as sensitizers to anticancer drugs. Nat. Rev. Cancer 5: 297–309.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Wang CY, Mayo MW, Baldwin AS (1996) TNF- and cancer therapy-induced apoptosis: potentiation by inhibition of NF-_κ_B. Science 274: 784–787.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Wang CY, Cusack JC, Liu R, Baldwin AS (1999) Control of inducible chemoresistance: enhanced anti-tumor therapy through increased apoptosis by inhibition of NF-_κ_B. Nat. Med. 5: 412–417.

Article Google Scholar - Cusack JC, Liu R, Houston M, Abendroth K, Elliott PJ, Adams J, Baldwin AS (2001) Enhanced chemosensitivity to CPT11 with proteasome inhibitor PS-341: implications for systemic NF-_κ_B inhibition. Cancer Res. 61: 3535–3540.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Naskhatri H, Rice SE, Bhat-Naksshatri P (2004) Antitumor agent parthenolide reverses resistance of breast cancer cells to TRAIL through sustained activation of JNK. Oncogene 23: 7330–7344.

Article Google Scholar - Farhana L, Dawson M, Fontana JA (2005) Apoptosis induction by a novel retinoid-related molecule requires NF-_κ_B activation. Cancer Res. 65: 4909–4917.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Jin F, Liu X, Zhou Z, Yue P, Lotan R, Khuri F, Chung L, Sun SY (2005) Activation of NF-_κ_B contributes to the induction of death receptors and apoptosis by the synthetic retinoid CD437 in DU145 human prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 65: 6354–6363.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Stark LA, Dunlop MG (2005) Nucleolar sequestration of RelA (p65) regulates NF-_κ_B-driven transcription and apoptosis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25: 5985–6004.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Campbell K, Rocha S, Perkins N (2004) Active repression of antiapoptotic gene expression by RelA/p65 NF-_κ_B. Mol. Cell 13: 853–865.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Ho WC, Dickson KM, Barker P (2005) NF-_κ_B induced by doxorubicin is deficient in phosphorylation and acetylation and represses NF-_κ_B-dependent transcription in cancer cells. Cancer Res. 65: 4273–4281.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Ashikawa K, Shishodia S, Fokt I, Priebe W, Aggarwal BB (2004) Evidence that activation of NF-_κ_B is essential for the cytotoxic effects of doxorubicin and its analogues. Biochem. Pharm. 67: 353–364.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful for discussions with members of the Baldwin laboratory. We acknowledge scientific support from the NIH/NCI, the UNC Breast and GI SPORE programs, the Department of Defense Breast Cancer Program, and the Waxman Cancer Research Foundation to ASB. HJK is supported by a KO8 award from the NCI. Additionally, owing to editorial limitations, we regret our inability to reference all of the important published manuscripts on NF-_κ_B and oncogenesis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- Department of Surgery, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, 27599, NC, USA

H J Kim - Department of Biology, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, 27599, NC, USA

A S Baldwin - Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, 27599, NC, USA

H J Kim, N Hawke & A S Baldwin

Authors

- H J Kim

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - N Hawke

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - A S Baldwin

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence toA S Baldwin.

Additional information

Edited by G Kroemer

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, H., Hawke, N. & Baldwin, A. NF-κB and IKK as therapeutic targets in cancer.Cell Death Differ 13, 738–747 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.cdd.4401877

- Received: 08 November 2005

- Revised: 22 December 2005

- Accepted: 09 January 2006

- Published: 17 February 2006

- Issue Date: 01 May 2006

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.cdd.4401877