Robustness and evolution: concepts, insights and challenges from a developmental model system (original) (raw)

Introduction

Here we first define robustness and review experimental ways to detect it. We then discuss the proximate mechanisms underlying robustness. Finally, we discuss evolutionary causes and consequences of robustness.

What is robustness, and why is it important?

Robustness is the persistence of an organismal trait under perturbations. Many different organismal features could qualify as traits in this definition of robustness. A trait could be the proper fold or activity of a protein, a gene expression pattern produced by a regulatory gene network, the regular progression of a cell division cycle, the communication of a molecular signal from cell surface to nucleus, a cell interaction necessary for embryogenesis or the proper formation of a viable organism or organ.

Robustness is important in ensuring the stability of phenotypic traits that are constantly exposed to genetic and non-genetic variation. To better understand robustness is of paramount importance for understanding organismal evolution, because robustness permits cryptic genetic variation to accumulate. Such variation may serve as a source of new adaptations and evolutionary innovations.

We will focus here on developmental traits and on the robust formation of organs. Specifically, we will discuss important concepts and challenges in studying robustness using the vulva of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans, an exceptionally well-studied developmental model. Here, the robust trait is the spatial pattern of vulval cell fates (Box 1). For further reading on different aspects of biological robustness and canalization, a non-exhaustive list of more extensive reviews includes: Gibson and Wagner, 2000; Debat and David, 2001; de Visser et al., 2003; Gibson and Dworkin, 2004; Flatt, 2005; Dworkin, 2005a; Wagner, 2005a.

Box 1 C. elegans vulva, a robust developmental system

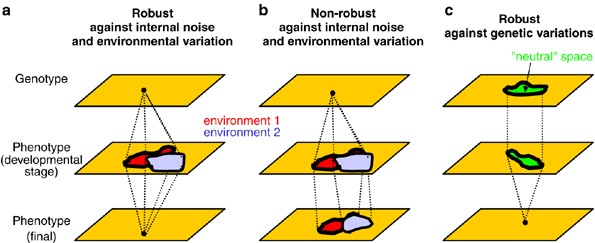

We note that the final product of a biological process may be robust despite variation in some intermediate trait (Figure 1), such as a developmental stage, the activity of a signaling pathway or the expression of a gene product. To give but one example from vulval development, animals that are heterozygotes for a null mutation in the gene coding for the epidermal growth factor (EGF) signal have a normal vulva fate pattern (Ferguson and Horvitz, 1985). This indicates that variation in EGF signal levels – which can be viewed as an intermediate phenotypic trait – is buffered. Cell fate output is invariant to such buffered variation.

Figure 1

Robustness to stochastic noise, environmental change and genetic variation. Genotype and phenotype spaces are represented schematically in two dimensions. In (a) the final phenotype is robust to stochastic noise and environmental change. For any biological process, for example a developing system, the end product of the process may be robust whereas an intermediate trait (an intermediate metabolite concentration, a developmental stage in a multicellular organism, etc.) may not be robust. In (b) the system is not robust to the same perturbations. In (c) the system is robust to some genetic variation (green), thus allowing for cryptic variation to accumulate. A system that is robust to noise and a range of environmental variations (as in a) is likely to be robust to some genetic variation (as in c). The genotype space that produces the same final phenotype is ‘neutral’ in this respect (and possibly also for fitness) yet intermediate phenotypes may display variation.

Robustness to what?

Robustness can be discussed sensibly only if two cardinal questions have been resolved. What is the trait of interest? And what is the perturbation of interest? There are three principal kinds of perturbations to which a system may be robust: stochastic noise, environmental change and genetic variation (Figure 1).

Noise refers to the stochastic fluctuations that occur in any biological system, for example in the concentration of a biological molecule or in a cell's position, either over time, or between two genetically identical individuals, even if the external environment is constant. Developmental traits lacking robustness to noise include human fingerprints, which differ among genetically identical twins (Stigler, 1995). An example from C. elegans vulval development is the division pattern of the cell P3.p at the anterior border of the vulva competence group (see Box 1). This cell divides in only some genetically identical worms, whereas in others it directly fuses with the epidermal syncytium and loses vulval competence (Sulston and Horvitz, 1977; Eisenmann et al., 1998).

The second kind of perturbation is variation in the external environment, for example a change in temperature, salinity or nutrient availability. Many developmental traits, such as the C. elegans vulva fate pattern (C Braendle and M-A Félix, unpublished), are highly robust to environmental changes. In contrast, some traits are strongly influenced by the environment, for example the propensity of C. elegans larvae to develop through the resistant dauer stage (Riddle and Albert, 1997). The effect of the environment may range from a shift in a quantitative distribution (e.g. body size as a function of nutrition in humans) to the appearance of alternative phenotypes (e.g. caste determination as a function of nutrition in social insects). In these cases, the final phenotype is not robust, but plastic (Pigliucci, 2005). The ecology of an organism is thus clearly important in understanding a trait's robustness properties. Specifically, robustness to frequent environmental perturbations may be of greater adaptive significance than robustness to perturbations that occur rarely or never.

The third kind of perturbation is genetic change, either through de novo mutation or through recombination. Here, the genetic structure of populations becomes relevant to characterize robustness properties. As a simple example, in diploids the effect of a new recessive mutation will depend on its probability to be found in the homozygous state. This probability itself is a function of the mode of reproduction (selfing versus outcrossing) and of the effective size of the population (Hartl and Clark, 1997). In addition to mutational variation, robustness to genetic variation includes robustness to the effect of recombination between alleles at different loci. As a consequence, spatial genetic structure becomes crucial in the evolution of a system's robustness properties, for example through the migration rate between populations adapted to local environments (Ancel Meyers and Bull, 2002; Proulx and Phillips, 2005). Frequent recombination may favor the evolution of mutational robustness. This form of genetic robustness may result in negative epistasis (synthetic effects of deleterious mutations), which in turn renders sex (and recombination) advantageous. This feedback between genetic robustness and recombination frequency has been proposed as an explanation for the evolution and maintenance of sex (Azevedo et al., 2006).

How is robustness detected?

Robustness is not an all-or-nothing property. It is a matter of degree. For a quantitative trait, lack of robustness can be expressed using the coefficient of variation (square root of the variance over the mean) for the trait or, when comparing two conditions, the unsigned difference in the means (Houle, 1992; Dworkin, 2005a). For a complex qualitative trait such as a protein sequence or the vulval cell fate pattern, robustness (or a lack thereof) can be expressed using the proportion of deviant phenotypes produced in response to perturbations. For example, a given environmental condition or mutation may produce a deviant phenotype for a large (e.g., 10−2) or small (10−10) fraction of organisms. In addition, the types of deviation (‘errors’) that a system produces – an amino-acid misincorporation in a protein sequence during translation, a deviant cell fate pattern (see Box 1; Figure B4) or the shape of an organ – and their consequence on the organism's fitness influence crucially how natural selection acts on a system, yet they are often not investigated. We now outline three basic experimental approaches to probe and measure robustness, following the distinction between the three different kinds of perturbations that may affect a system.

Robustness of a trait to noise is best detected by assaying individuals of an isogenic strain in a given constant environment. The use of isogenic strains eliminates confounding effects from genetic variation between individuals in assessing the effect of stochastic noise. For organisms that have a prominent haploid life cycle stage (many fungi, bacteria) or are commonly selfing (such as C. elegans), isogenic strains are easy to obtain. Vulva development of C. elegans has been mostly studied using the isogenic N2 reference strain in one standard culture condition. In these conditions, vulva cell fate patterning errors are found at a low frequency (on the order of 10−3 or less, for deviations that disrupt the cell fate pattern, but do not necessarily prevent egg-laying), implying that this aspect of vulva development is precise and robust to stochastic noise (Delattre and Félix, 2001; C Braendle and M-A Félix, unpublished). The degree of robustness and the types of error can be compared between different isogenic backgrounds. A second way to eliminate confounding effects from genetic variation in measuring robustness to noise is to quantify the developmental variation between the right and left sides of an animal (fluctuating asymmetry).

Robustness of a trait to environmental variation is detected by subjecting organisms to a given environmental change or an array of environmental changes that may mimic ecologically relevant environments, possibly including some ‘stressful’ environments. In the vulva example, under starvation conditions in the second larval stage (one test environment), C. elegans N2 individuals are prone to miscenter their vulva on P5.p instead of P6.p (C Braendle and M-A Félix, unpublished). This centering variation of the cell fate pattern results in a quasi-normal vulva because P4.p is competent to form vulval tissue and adopts a 2° fate in these animals. Furthermore, the incidence and patterning of vulva variants vary with environmental conditions. They also vary with the wild-type genetic background (C Braendle and M-A Félix, unpublished), which means that they are subject to evolutionary change, possibly via the action of natural selection (see below).

Robustness to a given mutation is detected by comparing the mutant to the reference wild-type genotype, and asking whether the mutation is silent or neutral, that is, whether it lacks an effect on the trait. The question whether a mutation is truly neutral is surprisingly difficult to answer (Wagner, 2005b). For instance, a mutation might have an effect at one developmental stage, but not on the final phenotype (Figure 1c), or vice versa. In addition, a mutation's effect may critically depend on the genotype at other loci. For instance, in C. elegans vulva development, null mutations in the gene coding for the Ras GTPase activating protein (GAP-1, a Ras inhibitor), or for an activator of EGF receptor degradation (SLI-1), are silent with respect to the final cell fate pattern. The system is robust to these mutations. In contrast, the double mutant displays an excess of vulval fates, showing that these two molecules indeed modulate Ras pathway activity and are thus not silent at this level (Yoon et al., 1995; Hajnal et al., 1997; Hopper et al., 2000).

This test of robustness to a given mutation can be extended to a statistical measure (e.g. the mutational variance for quantitative traits; Lynch et al., 1999) of the effect of thousands of random mutations that are produced either spontaneously or through systematic mutagenesis studies. Systematic gene inactivation libraries (e.g. RNAi libraries in C. elegans; Kamath et al., 2003) are becoming available in several organisms. However, many of these ‘inactivations’ may be partial and result in a reduction of a gene's function. They thus only represent a narrow band within a broader spectrum of mutational effects in the wild. More ‘natural’ mutational patterns are best reconstituted using spontaneous mutation accumulation lines (Denver et al., 2004). These lines are obtained by propagating multiple populations (lines) of organisms by only retaining one or two randomly chosen individuals per line for reproduction at each generation. The resulting severe bottleneck reduces the efficacy of natural selection and allows the accumulation of deleterious mutations over many generations (Lynch et al., 1999). The phenotypic effect of random mutation on the vulva system was probed using a set of mutation accumulation lines derived from the N2 genotype over the course of 400 generations (a generous gift from L Vassilieva and M Lynch; Vassilieva et al., 2000): ‘errors’ in cell fate patterning and centering increased in most of the lines compared to the N2 control (M-A Félix, unpublished).

Another, indirect approach to inferring robustness to genetic change uses genetic variation that occurs in natural populations. In this comparative approach, one considers genetic variation among individuals of the same or different species. These species share an invariant trait that may be produced by a varying developmental process. For example, in several species related to C. elegans the final vulval cell fate pattern is invariant, but the developmental route to this final pattern varies strikingly among them (Box 1, Figure B1) (Félix, 1999; Sommer, 2000). This qualitative approach is powerful because it allows the comparison of organisms and genotypes that are only remotely related. Such organisms have accumulated much greater genetic change than can be produced in laboratory evolution experiments. However, the approach does not provide a quantitative measure of robustness to random genetic change. It also has the disadvantage that the adaptive significance of the existing variation (truly neutral, beneficial, or slightly deleterious) is often not known.

Finally, a generic approach in estimating robustness applies to traits whose mechanistic basis is experimentally well studied. For such traits, one can build quantitative models of the developmental process producing a trait. Such models permit estimation of the trait's sensitivity to changes in model parameters (Barkai and Leibler, 1997; von Dassow et al., 2000; Meir et al., 2002; Eldar et al., 2002, 2003). Changes in parameters (e.g., the affinity of a transcription factor for its target site, or the degradation rate of a protein) may result either from environmental variation or from mutational change. To systematically perturb model parameters thus allows one to assay a system's robustness to multiple types of change. One challenge for this approach is to provide a quantitative framework to integrate information about mutational variation and population structure on the one hand, and environmental variation on the other. In addition, experimental data for model building and validation are sorely needed.

Proximate (mechanistic) causes of robustness

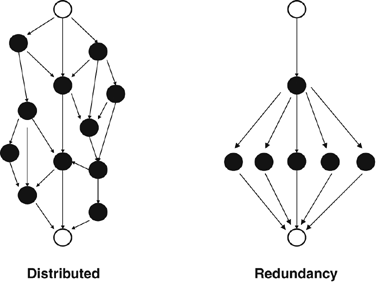

Different categorizations of mechanistic causes of robustness are conceivable (Gerhart and Kirschner, 1997; McAdams and Arkin, 1999; Wagner, 2005c). We here emphasize a simple yet very fundamental one: redundancy versus distributed robustness (Figure 2).

Figure 2

An illustration of distributed robustness versus redundancy. Both panels of the figure show a hypothetical signal transduction or metabolic pathway in which information about an upstream signal (upper white circles, e.g., the presence of a growth factor ligand) is communicated via a number of intermediate pathway components (black circles) to a downstream effector (lower white circles, e.g., a transcription factor). If a pathway like this shows distributed robustness (left), it is robust because the flow of information is distributed among several alternative paths, with no two parts performing the same function. In contrast, if robustness is achieved through redundancy (right), several components perform the same function.

In a system with redundant parts, multiple components of a system have the same function. Redundancy is generally an important cause of robustness in systems whose parts are genes. The reason is that genomes are littered with duplicate genes, and gene duplication is a process that produces genes with redundant functions. Redundancy may also be found at other levels, for example between cells. An example is the redundancy between cells of the vulval competence group, where one cell can replace another (defective) one in making vulval tissue (Sulston and White, 1980).

Distributed robustness, in contrast, can exist even in systems where no two parts exert the same function. Prominent candidate examples of distributed robustness can be found in metabolic systems. For example, many metabolic functions have long feedback loops, where the end-product of a long chain of chemical reaction allosterically inhibits the enzyme catalyzing the first reaction, thus providing homeostatic regulation. Similarly, in complex metabolic reaction networks, blockage of one metabolic pathway may have little consequence if an important metabolite can be produced through an alternative pathway, even though the two pathways may not share a single enzyme with identical (redundant) functions.

Which of these causes of robustness, redundancy versus distributed robustness, is prevalent in biological systems is a matter of some debate. However, the often rapid divergence in both sequence and function of gene duplicates suggests that gene redundancy may be less important in providing robustness than one might think (Wagner, 2005c). Although a systematic study of the robustness of altered vulva signaling networks is still missing, the available evidence indicates that distributed robustness is important in vulva development. Specifically, the vulva system appears to have several mechanistic features that involve distributed robustness.

First, the dynamic behavior of core components of the Ras pathway results in nonlinearities and may thus contribute to robustness to a broad range of variation in EGF signaling. For example, the multiple phosphorylations of mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase and the positive feedback loop from the activated MAP kinase to the EGF receptor (Box 1, Figure B2) are likely to create a switch between at least two activity plateaus, a high Ras pathway activity triggering a 1° fate, a low Ras activity a 3° fate.

Second, the Ras pathway has many additional inputs of silent positive and negative regulators that can buffer genetic (or non-genetic) variation (Figure B2) ([Sundaram, 2006](/articles/6800915#ref-CR65 "Sundaram M (2006). RTK/Ras/MAP signaling. In: WormBook (ed). The C. elegans Research Community WormBook, doi/10.1895/wormbook.1.80.1, http://www.wormbook.org

.")). As mentioned above with the SLI-1/GAP-1 example, the knockout of one regulator is silent, but the inactivation of two of these regulators may have an effect ([Ferguson and Horvitz, 1989](/articles/6800915#ref-CR21 "Ferguson EL, Horvitz HR (1989). The Multivulva phenotype of certain C. elegans mutants results from defects in two functionally-redundant pathways. Genetics 123: 109–121."); [Hopper et al., 2000](/articles/6800915#ref-CR32 "Hopper NA, Lee J, Sternberg PW (2000). ARK-1 inhibits EGFR signaling in C. elegans. Mol Cell 6: 65–75."); [Kao et al., 2004](/articles/6800915#ref-CR37 "Kao G, Tuck S, Baillie D, Sundaram MV (2004). C. elegans SUR-6/PR55 cooperates with LET-92/protein phosphatase 2A and promotes Raf activity independently of inhibitory Akt phosphorylation sites. Development 131: 755–765."); [Berset et al., 2005](/articles/6800915#ref-CR6 "Berset TA, Hoier EF, Hajnal A (2005). The C. elegans homolog of the mammalian tumor suppressor Dep-1/Scc1 inhibits EGFR signaling to regulate binary cell fate decisions. Genes Dev 19: 1328–1340.")). The affected regulators are not redundant, in the sense that they usually do not perform the same molecular activity, nor do they act at the same step in the pathway. One exception is the gene duplication of the positive regulator KSR ([Ohmachi et al., 2002](/articles/6800915#ref-CR50 "Ohmachi M, Rocheleau C, Church D, Lambie E, Schedl T, Sundaram M (2002). C. elegans ksr-1 and ksr-2 have both unique and redundant functions and are required for MPK-1 ERK phosphorylation. Curr Biol 12: 427–433.")).Third, the cross-talk between the Ras and Notch pathways is a typical case of distributed robustness contributing to the specification of three cell fates (Giurumescu et al., 2006). A high Ras activity triggers Notch degradation in the 1° cell and thus ensures that the cell does not adopt a 2° fate (Shaye and Greenwald, 2002). A high Ras activity also activates the expression of several Delta-like molecules (the Notch ligands) by the 1° cell (Chen and Greenwald, 2004). The Delta-like molecules activate Notch in neighboring cells, which in turn inhibits Ras pathway activity in those cells (Berset et al., 2001; Yoo et al., 2004). This interaction probably helps form a robust switch between the 2 and 1° fates.

Fourth, at least in some experimental conditions, the 2° vulval fate can be specified either through morphogen action of the EGF inducer at intermediate doses (Katz et al., 1995), or through lateral activation of the Notch pathway by the 1° cell, which itself acts downstream of EGF/Ras signaling in the 1° cell (Koga and Ohshima, 1995; Simske and Kim, 1995). If developmental perturbations inhibit one mechanism, the alternative mechanism may guarantee a stable output (Kenyon, 1995). Again, these two mechanisms may be said to act redundantly in a wide sense, but they do not perform equivalent activities in the vulva signaling network: one is directly downstream of the EGF inducer, whereas the other is downstream of lateral signaling through Notch. Overall network topology thus contributes to the robustness of the vulva system.

Clearly, to study the mechanistic causes of robustness is crucial to understand its functional and evolutionary significance. Yet, despite having learnt many mechanistic details about the vulva signaling network or similar models, we still know very little about how the system actually operates in different environmental conditions, what type of noise it is subject to, and when a given regulatory interaction occurs and is required for the final output. This lack of insight challenges us to better characterize the mechanistic causes of robustness in this and other model systems.

Ultimate (evolutionary) causes of robustness

The robustness of a trait to perturbations can have two evolutionary causes. One such cause – you might call it ‘_robustness for free_’ – is rooted in the observation that most biological processes (from enzymatic catalysis to organismal development) have an astronomical number of alternative yet equivalent solutions. These solutions can be thought of existing in a neutral space, in which individual solutions can often be connected through a series of neutral genetic changes (Gavrilets, 2004; Wagner, 2005a). We use the term ‘neutral’ in the sense that the change has no effect on the final phenotype because it is very difficult to assess whether any change is neutral for ‘fitness’ (Wagner, 2005a). In other words, the robustness of a trait may simply derive from the existence of many alternative ways of building it. A second possibility is that robustness is an evolutionary adaptation to perturbations. Where robustness of a trait is advantageous, natural selection can favor genotypes that render the trait robust. For developmental traits, such evolved robustness is called canalization (Waddington, 1942; Gibson and Wagner, 2000).

A sizable theoretical literature has arisen around the question under what conditions natural selection will lead to a trait's increased robustness (Wagner, 1996, 2000; Wagner et al., 1997a, 1997b; Houle, 1998; Krakauer and Nowak, 1999; van Nimwegen et al., 1999; Wilke, 2001; Krakauer and Plotkin, 2002; Meiklejohn and Hartl, 2002; Siegal and Bergman, 2002; Bagheri-Chaichian et al., 2003; Proulx and Phillips, 2005). A general insight that has emerged from this theoretical literature is that high robustness can only readily evolve to perturbations that are abundant. Except under high mutation rates, noise and environmental change are likely to be more important driving forces for the evolution of robustness. However, it is likely that the effect of mutation and of non-genetic change on a system are partially correlated, because both affect the same underlying biological processes. For example, an environmental change that results in a higher degradation rate of a protein may have effects similar to that of a reduction-of-function mutation causing a reduced gene expression level or reduced protein activity. In this case, robustness to the environmental change may result in robustness to the genetic change. Obviously, exceptions to this correlation are possible: a given environmental variation and a given mutation may have different effects on a system (Milton et al., 2003; Dworkin, 2005b). Unfortunately, a systematic experimental test of the relationship between environmental and genetic robustness of a trait is still lacking.

Despite an abundance of theoretical work, it is currently not clear which of the two potential causes – robustness for free or natural selection – is prevalent. For example, in the vulva system, robustness to stochastic and environmental variations may be an adaptation, the simple result of a selective process eliminating genetic variants that are less robust and thus deleterious in ecologically relevant environments. The comparison of vulva phenotypes in mutation accumulation lines with those of natural wild strains indeed suggests that several vulva phenotypes are under selection pressure (directly or indirectly), as they are easy to change through mutations yet very rare in the natural wild strains (M-A Félix, unpublished). Some robust features of the vulva network are thus likely to have evolved under selection, rather than merely as an accidental byproduct of the system's architecture. On the other hand, nonlinear effects that contribute to robustness may be unavoidable consequences of system properties that were not subject to direct selection on robustness. For example, enzymatic reactions are often relatively insensitive to enzyme concentrations. (Developmental signal transduction pathways involve many enzymes such as protein kinases and GTP-ases.) Such insensitivity implies a large fraction of neutral mutations among all mutations that affect enzyme concentration, which can thus evolve by neutral drift (Kacser and Burns, 1981; Hartl et al., 1985; Nijhout and Berg, 2003). Because robustness is not controlled independently from the core components of a system, it is not straightforward to disentangle buffering mechanisms that have been subject to natural selection from those that have not. This is a major challenge for future work.

Another open question is the extent to which trade-offs between different functions of a biological system influence the evolution of robustness. One might think, for example, that a gene regulatory network that needs to function in many different biological processes is more constrained in its evolution than a network deployed in only one process. For example, components of the Ras/MAP kinase pathway that are important in vulval fate induction also play a role in several other developmental decisions in C. elegans, as well as in olfaction and in response to pathogens ([Sundaram, 2006](/articles/6800915#ref-CR65 "Sundaram M (2006). RTK/Ras/MAP signaling. In: WormBook (ed). The C. elegans Research Community WormBook, doi/10.1895/wormbook.1.80.1, http://www.wormbook.org

.")). A key question here is how the different selection pressures affecting pleiotropic mutations shape the evolution of robustness.Evolutionary consequences of robustness

Mutational robustness causes an organism to tolerate changes. One immediate consequence is that for a robust trait, little genetic variation will be expressed as phenotypic variation. Natural selection, in turn, will be less effective in acting on the trait, at least in the short run, because the extent of phenotypic change that natural selection can cause strongly depends on phenotypically expressed genetic variation. Yet another immediate consequence is that cryptic genetic variation can accumulate, because neutral genetic variation accumulates faster than deleterious variation. The system can drift in neutral genotype space, and the larger the available neutral space, the more the system can drift. In other words, variation in an intermediate trait can accumulate without change in the robust final trait (Figure 1c). In the face of environmental stressors that drive a system to the limit of its buffered range, such variation can become expressed at the level of the final phenotype. The vast majority of such expressed variation may be deleterious in these new conditions. However, a tiny fraction of it can harbor the seeds of new adaptations, which can change the evolutionary trajectory of an organism. Cryptic genetic variation may thus play two roles in phenotypic variation: allowing variation in intermediate phenotypes in the short term, and potential future phenotypic evolution in the final phenotype in the long term. Present controversies that remain to be experimentally addressed are twofold: (i) assessing whether such cryptic genetic variation evolves neutrally or under some kind of selection in the short term and (ii) determining whether it may have a role in adaptation to new conditions in the long term.

Cryptic genetic variation is by definition difficult to detect. One way to uncover it is to experimentally drive the system out of its buffered range, using either environmental challenges such as heat shock or ether exposure as in the classical experiments by Waddington (Waddington, 1942; Gibson and Hogness, 1996), or mutations (Rutherford, 2000; Gibson and Dworkin, 2004). In the latter case, the same mutation is introduced (usually by repeated crosses leading to introgression) into different wild genetic backgrounds. Cryptic variation in these wild genetic backgrounds can be detected as variation in mutational effects among the different backgrounds. For example, robustness properties of the vulva network ensures that three precursor cells adopt vulval fates in all wild isolates of C. elegans. However, cryptic variation between these wild isolates can be unmasked by displacing the system from the plateau of three induced cells. This is done by strongly reducing or increasing Ras pathway activity through mutations (Box 1, Figures B3). Preliminary results suggest that the effect of Ras, Notch and Wnt pathway mutations does indeed vary significantly among different C. elegans wild genetic backgrounds (J Milloz, I Nuez and M-A Félix, unpublished). The robust vulva system thus accumulates cryptic variation, much like the robust cell fate patterning system of the Drosophila eye (Polaczyk et al., 1998). In the latter case, the genetic architecture of the cryptic variation is complex, involving variation at many loci and epistatic effects among them. Molecular variation at the EGF receptor locus contributes to a small but significant part of this variation (Dworkin et al., 2003). Understanding the genetic structure of cryptic genetic variation and the patterns of molecular evolution at the corresponding loci is an important current challenge (Gibson and Dworkin, 2004).

An alternative way to detect cryptic variation is to turn to an ‘intermediate’ phenotype, which may show variation between the tested conditions (Figure 1a, c). One needs to clearly distinguish between the final output of the system, which is robust and invariant, and intermediate phenotypes that may be plastic in response to environmental variations and accumulate genetic variation (which is ‘cryptic’ when referring to the final phenotype). For example, the level of Ras pathway activity may vary between different wild C. elegans isolates without effect on the final cell fate pattern, either because the change is small and does not displace the population from the robust plateau, or because it is compensated by a change at another level (e.g. downstream in the same pathway). Using such an ‘intermediate’ developmental phenotype, one can, in principle, reveal not only cryptic genetic variation, but also environmental or stochastic variation between individuals. Unraveling such variation remains an experimental challenge in robust developmental model systems.

In sum, we discussed here the concept of robustness, the nature of the perturbations to which biological systems can be robust, possible mechanistic and evolutionary causes of robustness, and the possible implications of robustness for evolution, all in the context of examples from the C. elegans vulva. These examples show that the challenges we face, even in a well-studied model system, greatly outnumber the insights we have. These challenges include to identify the prevalent mechanistic causes of robustness (redundancy or distributed robustness), to define the role of natural selection in their evolution, to identify the importance of trade-offs in multifunctional traits for the evolution of robustness, and to characterize the importance of cryptic variation for evolutionary innovation.

References

- Ancel Meyers L, Bull JJ (2002). Fighting change with change: adaptive variation in an uncertain world. TREE 17: 551–557.

Google Scholar - Azevedo RB, Lohaus R, Srinivasan S, Dang KK, Burch CL (2006). Sexual reproduction selects for robustness and negative epistasis in artificial gene networks. Nature 440: 87–90.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Bagheri-Chaichian H, Hermisson J, Vaisnys JR, Wagner GP (2003). Effects of epistasis on phenotypic robustness in metabolic pathways. Math Biosci 184: 27–51.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Barkai N, Leibler S (1997). Robustness in simple biochemical networks. Nature 387: 913–917.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Berset T, Hoier EF, Battu G, Canevascini S, Hajnal A (2001). Notch inhibition of RAS signaling through MAP kinase phosphatase LIP-1 during C. elegans vulval development. Science 291: 1055–1058.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Berset TA, Hoier EF, Hajnal A (2005). The C. elegans homolog of the mammalian tumor suppressor Dep-1/Scc1 inhibits EGFR signaling to regulate binary cell fate decisions. Genes Dev 19: 1328–1340.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Chen N, Greenwald I (2004). The lateral signal for LIN-12/Notch in C. elegans vulval development comprises redundant secreted and transmembrane DSL proteins. Dev Cell 6: 183–192.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - de Visser JA, Hermisson J, Wagner GP, Ancel Meyers L, Bagheri-Chaichian H, Blanchard JL et al. (2003). Perspective: evolution and detection of genetic robustness. Evolution 57: 1959–1972.

PubMed Google Scholar - Debat V, David P (2001). Mapping phenotypes: canalization, plasticity and developmental stability. TREE 16: 555–561.

Google Scholar - Delattre M, Félix M-A (2001). Polymorphism and evolution of vulval precursor cell lineages within two nematode genera, Caenorhabditis and Oscheius. Curr Biol 11: 631–643.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Denver DR, Morris K, Lynch M, Thomas WK (2004). High mutation rate and predominance of insertions in the Caenorhabditis elegans nuclear genome. Nature 430: 679–682.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Dworkin I (2005a). Canalization, cryptic variation, and developmental buffering: a critical examination and analytical perspective. In: Hallgrimsson B, Hall BK (eds). Variation – A Central Concept in Biology. Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam. pp 131–158.

Google Scholar - Dworkin I (2005b). A study of canalization and developmental stability in the sternopleural bristle system of Drosophila melanogaster. Evolution 59: 1500–1509.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Dworkin I, Palsson A, Birdsall K, Gibson G (2003). Evidence that Egfr contributes to cryptic genetic variation for photoreceptor determination in natural populations of Drosophila melanogaster. Curr Biol 13: 1888–1893.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Eisenmann DM, Maloof JN, Simske JS, Kenyon C, Kim SK (1998). The _β_-catenin homolog BAR-1 and LET-60 Ras coordinately regulate the Hox gene lin-39 during Caenorhabditis elegans vulval development. Development 125: 3667–3680.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Eldar A, Dorfman R, Weiss D, Ashe H, Shilo BZ, Barkai N (2002). Robustness of the BMP morphogen gradient in Drosophila embryonic patterning. Nature 419: 304–308.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Eldar A, Rosin D, Shilo B-Z, Barkai N (2003). Self-enhanced ligand degradation underlies robustness of morphogen gradients. Dev Cell 5: 635–646.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Félix M-A (1999). Evolution of developmental mechanisms in nematodes. J Exp Zool (Mol Dev Evol) 28: 3–18.

Article Google Scholar - Félix M-A, Sternberg PW (1997). Two nested gonadal inductions of the vulva in nematodes. Development 124: 253–259.

PubMed Google Scholar - Ferguson E, Horvitz HR (1985). Identification and characterization of 22 genes that affect the vulval cell lineages of Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 110: 17–72.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Ferguson EL, Horvitz HR (1989). The Multivulva phenotype of certain C. elegans mutants results from defects in two functionally-redundant pathways. Genetics 123: 109–121.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Flatt T (2005). The evolutionary genetics of canalization. Q Rev Biol 80: 287–316.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Gavrilets S (2004). Fitness Landscapes and the Origin of Species. University Presses of California: Columbia and Princeton. p 432.

Google Scholar - Gerhart J, Kirschner M (1997). Cells, Embryos and Evolution. Blackwell Science, Inc.: Oxford. p 641.

Google Scholar - Gibson G, Dworkin I (2004). Uncovering cryptic genetic variation. Nat Rev Genet 5: 681–690.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Gibson G, Hogness DS (1996). Effect of polymorphism in the Drosophila regulatory gene Ultrabithorax on homeotic stability. Nature 271: 200–203.

CAS Google Scholar - Gibson G, Wagner G (2000). Canalization in evolutionary genetics: a stabilizing theory? Bioessays 22: 372–380.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Giurumescu CA, Sternberg PW, Asthagiri AR (2006). Intercellular coupling amplifies fate segregation during Caenorhabditis elegans vulval development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 1331–1336.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Hajnal A, Whitfield CW, Kim SK (1997). Inhibition of Caenorhabditis elegans vulval induction by gap-1 and by let-23 receptor tyrosine kinase. Genes Dev 11: 2715–2728.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Hartl DL, Clark AG (1997). Principles of Population Genetics. Sinauer Associates, Inc.: Sunderland, MA. p 542.

Google Scholar - Hartl DL, Dykhuizen DE, Dean AM (1985). Limits of adaptation: the evolution of selective neutrality. Genetics 111: 655–674.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Hopper NA, Lee J, Sternberg PW (2000). ARK-1 inhibits EGFR signaling in C. elegans. Mol Cell 6: 65–75.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Houle D (1992). Comparing evolvability and variability of quantitative traits. Genetics 130: 195–204.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Houle D (1998). How should we explain variation in the genetic variance of traits? Genetica 102–103: 241–253.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Kacser H, Burns JA (1981). The molecular basis of dominance. Genetics 97: 639–666.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Kamath RS, Fraser AG, Dong Y, Poulin G, Durbin R, Gotta M et al. (2003). Systematic functional analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome using RNAi. Nature 421: 231–237.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Kao G, Tuck S, Baillie D, Sundaram MV (2004). C. elegans SUR-6/PR55 cooperates with LET-92/protein phosphatase 2A and promotes Raf activity independently of inhibitory Akt phosphorylation sites. Development 131: 755–765.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Katz WS, Hill RJ, Clandinin TR, Sternberg PW (1995). Different levels of the C. elegans growth factor LIN-3 promote distinct vulval precursor fates. Cell 82: 297–307.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Kenyon C (1995). A perfect vulva every time: gradients and signalling cascades in C. elegans. Cell 82: 171–174.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Koga M, Ohshima Y (1995). Mosaic analysis of the let-23 gene function in vulval induction of Caenorhabditis elegans. Development 121: 2655–2666.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Krakauer DC, Nowak MA (1999). Evolutionary preservation of redundant duplicated genes. Sem Cell Dev Biol 10: 555–559.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Krakauer DC, Plotkin JB (2002). Redundancy, antiredundancy, and the robustness of genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 1405–1409.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Lynch M, Blanchard JL, Houle D, Kibota T, Schultz S, Vassileva L et al. (1999). Spontaneous deleterious mutation. Evolution 53: 645–663.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - McAdams HH, Arkin A (1999). It's a noisy business! Genetic regulation at the nanomolar scale. Trends Genet 15: 65–69.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Meiklejohn CD, Hartl DL (2002). A single mode of canalization. TREE 17: 468–473.

Google Scholar - Meir E, von Dassow G, Munro E, Odell GM (2002). Robustness, flexibility, and the role of lateral inhibition in the neurogenic network. Curr Biol 12: 778–786.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Milton CC, Huynh B, Batterham P, Rutherford SL, Hoffmann AA (2003). Quantitative trait symmetry independent of Hsp90 buffering: distinct modes of genetic canalization and developmental stability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 13396–13401.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Moghal N, Garcia LR, Khan LA, Iwasaki K, Sternberg PW (2003). Modulation of EGF receptor-mediated vulva development by the heterotrimeric G-protein Gαq and excitable cells in C. elegans. Development 130: 4553–4566.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Nijhout HF, Berg AM (2003). A mechanistic study of evolvability using the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade. Evol Dev 5: 281–294.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Ohmachi M, Rocheleau C, Church D, Lambie E, Schedl T, Sundaram M (2002). C. elegans ksr-1 and ksr-2 have both unique and redundant functions and are required for MPK-1 ERK phosphorylation. Curr Biol 12: 427–433.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Pigliucci M (2005). Evolution of phenotypic plasticity: where are we going now? Trends Ecol Evol 20: 481–486.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Polaczyk PJ, Gasperini R, Gibson G (1998). Naturally occurring genetic variation affects Drosophila photoreceptor determination. Dev Genes Evol 207: 462–470.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Proulx SR, Phillips PC (2005). The opportunity for canalization and the evolution of genetic networks. Am Naturalist 165: 147–162.

Article Google Scholar - Riddle DL, Albert PS (1997). Genetic and environmental regulation of dauer larva development. In: Riddle DL, Blumenthal T, Meyer BJ, Priess JR (eds). C. elegans II. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: Cold Spring Harbor, NY. pp 739–768.

Google Scholar - Rutherford SL (2000). From genotype to phenotype: buffering mechanisms and the storage of genetic information. Bioessays 22: 1095–1105.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Shaye DD, Greenwald I (2002). Endocytosis-mediated downregulation of LIN-12/Notch upon Ras activation in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 420: 686–690.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Siegal ML, Bergman A (2002). Waddington's canalization revisited: developmental stability and evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 10528–10532.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Simske JS, Kim SK (1995). Sequential signalling during Caenorhabditis elegans vulval induction. Nature 375: 142–146.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Sommer RJ (2000). Evolution of nematode development. Curr Opin Gen Dev 10: 443–448.

Article CAS Google Scholar - Sommer RJ, Sternberg PW (1994). Changes of induction and competence during the evolution of vulva development in nematodes. Science 265: 114–118.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Sternberg PW (2005). Vulval development. In: WormBook (ed). The C. elegans Research Community, WormBook, doi/10.1895/wormbook.1.6.1, http://www.wormbook.org.

- Stigler SM (1995). Galton and identification by fingerprints. Genetics 140: 857–860.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Sulston J, Horvitz HR (1977). Postembryonic cell lineages of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol 56: 110–156.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Sulston JE, White JG (1980). Regulation and cell autonomy during postembryonic development of Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol 78: 577–597.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Sundaram M (2006). RTK/Ras/MAP signaling. In: WormBook (ed). The C. elegans Research Community WormBook, doi/10.1895/wormbook.1.80.1, http://www.wormbook.org.

- van Nimwegen E, Crutchfield JP, Huynen M (1999). Neutral evolution of mutational robustness. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 9716–9720.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Vassilieva LL, Hook AM, Lynch M (2000). The fitness effects of spontaneous mutations in Caenorhabditis elegans. Evolution 54: 1234–1246.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - von Dassow G, Meir E, Munro EM, Odell GM (2000). The segment polarity network is a robust developmental module. Nature 406: 188–192.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Waddington CH (1942). Canalization of development and the inheritance of acquired characters. Nature 150: 563–565.

Article Google Scholar - Wagner A (1996). Does evolutionary plasticity evolve? Evolution 50: 1008–1023.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Wagner A (2000). The role of population size, pleiotropy and fitness effects of mutations in the evolution of overlapping gene functions. Genetics 154: 1389–1401.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar - Wagner A (2005a). Robustness and Evolvability in Living Systems. Princeton University Press: Princeton and Oxford. p 367.

Google Scholar - Wagner A (2005b). Robustness, evolvability, and neutrality. FEBS Lett 579: 1772–1778.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Wagner A (2005c). Distributed robustness versus redundancy as causes of mutational robustness. Bioessays 27: 176–188.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Wagner GP, Booth G, Bagheri-Chaichian H (1997a). A population genetic theory of canalization. Evolution 51: 329–347.

Article PubMed Google Scholar - Wagner GP, Laublicher MD, Bagheri-Chaichian H (1997b). Genetic measurement theory of epistatic effects. Genetica 103: 569–580.

Google Scholar - Wilke CO (2001). Adaptive evolution on neutral networks. Bull Math Biol 63: 715–730.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Yoo AS, Bais C, Greenwald I (2004). Crosstalk between the EGFR and LIN-12/Notch pathways in C. elegans vulval development. Science 303: 663–666.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar - Yoon CH, Lee J, Jongeward GD, Sternberg PW (1995). Similarity of sli-1, a regulator of vulval development in Caenorhabditis elegans, to the mammalian proto-oncogene, c-cbl. Science 269: 1102–1105.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Acknowledgements

M-A Félix is grateful to C Braendle and A Barrière for their insightful comments on the manuscript and to C Braendle and J Milloz for sharing their results and for many interesting discussions. Work on vulva development robustness in the Félix lab is funded by the CNRS and grants from ARC (no. 3749) and ANR (ANR-05-BLAN-0231-01). AW acknowledges support through NIH Grant GM 63882.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- Institut Jacques Monod, CNRS-Universities of Paris 6/7, Paris, France

M-A Félix - Department of Biochemistry, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

A Wagner

Authors

- M-A Félix

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar - A Wagner

You can also search for this author inPubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence toM-A Félix.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Félix, MA., Wagner, A. Robustness and evolution: concepts, insights and challenges from a developmental model system.Heredity 100, 132–140 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.hdy.6800915

- Received: 06 April 2006

- Revised: 22 August 2006

- Accepted: 02 September 2006

- Published: 13 December 2006

- Issue Date: 01 February 2008

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.hdy.6800915